Abstract

This study examined the messages perceived by adolescent girls with orphanhood to influence their sexual decision-making. Participants were 125 students (mean age =14.7 years), 54% of whom attended church schools in a rural district of eastern Zimbabwe. We collected and analyzed data using concept mapping, a mixed method approach that enabled the construction of message clusters, with weighting for their relative importance. Messages that clustered under Biblical Teachings and Life Planning ranked highest in salience among students in both church and secular schools. Protecting Family Honor, HIV Prevention, and Social Stigma messages ranked next, respectively. Contrary to study hypotheses, the messages that orphan adolescent girls perceived to influence their sexual decisions did not vary by type of school attended.

Keywords: School-based HIV prevention, Orphan girls, Zimbabwe, Sexual health, Mixed Methods

Introduction

Orphanhood is a major challenge to the health and well being of children in sub-Saharan Africa. Orphan prevalence has risen dramatically over the past three decades, mostly from the HIV pandemic, with Zimbabwe particularly hard-hit (UNAIDS, 2011). Child orphans are those with loss of both parents or with a surviving parent (UNAIDS, UNICEF & USAID, 2010). Rural orphan girls in Zimbabwe are vulnerable to early marriage, a major risk factor for school dropout (Hallfors et al., 2011). Early marriage is also highly associated with higher risk for HIV infection in Zimbabwe (Birdthistle et al., 2008; Hallfors et al., 2012). Schools in sub-Saharan Africa teach sex and HIV prevention in the context of life skills education (Agha & Rossem, 2004; Levers, Mpofu & Ferreira, 2011; Mbizvo et al., 1997). Consequently, school-based sex and HIV prevention education is broadly accessible to vulnerable children, including orphans, who attend school. Little is known, however, about how sex education messages are actually perceived by youth, nor how these perceptions differ in religious schools, which comprise an important alternative educational setting in Zimbabwe, compared to secular schools. Implementation studies of school-based interventions typically focus on fidelity of implementation (Kafterian et al., 2004; Payne & Eckert, 2010) and not on the context within which sexual health education messages are received. Such information may provide scientists with essential clues for improving prevention messages and adapting them to better fit within the context of vulnerable children's lives.

This paper examines the school-based sex and HIV messages perceived by a sample of rural orphan girls in both church-run and government-run high schools in Zimbabwe. The study is part of a randomized controlled trial in Zimbabwe to examine whether church-based high schools might provide greater protection to orphan girls for preventing HIV infection (Hallfors et al., 2011). The randomized control trial tested effects on school retention as a moderator of sexual health in teenage girls with orphanhood attending church or secular schools and receiving minimal tuition support. Thus, for the present portion of the study, we sought to understand the type of school environment effects on the messages the teenagers perceived to receive to influence their sexual decisions, and to compare the influence of different school environments.

Structural theory (Karmon, 2007; Jansen, 2009) considers schools to be knowledge generating and validating systems which promote certain forms of knowledge over others. From a structural theory perspective, schools as knowledge communities both explicitly and implicitly communicate messages to the membership (i.e., students, teachers, parents) not only about the specific content that counts for valid knowledge but also the acceptable ways of knowing for the dwellers or participants within the knowledge environment. The school environment messages have a controlling effect on the membership, and of which the membership may not be consciously aware of (Brenner, 2001). We believed church and secular type of schools would offer qualitatively different learning contexts to influence orphan girl children in their sexual decision making. For instance, we expected that church schools would value faith-informed concepts for sexual health (e.g., abstinence) whereas secular schools would emphasize life skills education (Mpofu, Mutepfa & Hallfors, 2012), although some studies have found fewer differences than expected (Basinga, Bizimana & Munyanshongore, 2009; Mbizvo et al., 1997; Mpofu et al., 2012). As an example, a Rwanda study (Basinga, Bizimana & Munyanshongore, 2009) contrasted knowledge, attitudes and sexual practices among secondary school students attending a secular school versus a Baptist church school and reported no differences by type of school on the outcome measures, including condom use. On the other hand, Mpofu et al. (2012) found that Zimbabwe church schools emphasized biblical teachings and abstinence strategies and excluded condom use to a greater degree than secular schools.

Secular schools may foster more diffuse sex and HIV education messages reflecting a greater diversity of beliefs bound by a common thread of shared traditional beliefs, as compared to a more western-influenced perspective from the mission churches. Although all schools receive curricula and other HIV-related information from the Ministry of Education, Christian schools maybe more deliberative in how and what is presented to students (Mpofu et al., 2012). Mission church influence can lead to unexpected results, as in the case of a recent Zimbabwe study that found Methodist orphan adolescent girls were more likely to endorse gender equity beliefs compared to similar girls from indigenous Apostolic or traditional faiths (Hallfors et al., 2011). Thus, in a country where almost 80% of the people profess to some form of Christian church affiliation (CSO/Macro, 2007) and where HIV infection is among the highest in the world (Central Intelligence Agency, 2012), it is important to examine the context of HIV prevention messages received in different types of schools, the prime setting for providing such messages to youth.

Goals of the study

This study sought to understand the types of sex and HIV prevention education messages that orphan girls perceived to influence their sexual decisions. We hypothesized that our sample of orphan girls attending church schools would be more likely to perceive that faith-oriented messages influence their sexual decisions compared to the sample at secular schools. Conversely, we expected that those in secular schools would report life skills messages as the primary influence on their decision-making. We hypothesized that girls from church-run schools would prioritize messages about sexual abstinence more highly than those attending secular schools. By contrast, girls from secular schools would convey more varied message content, reflecting a diversity of teachings dependent on individual school leadership, without a clear unifying theme. This is primarily a methodological study in which we used a mixed method approach to co-construct with teenagers with orphanhood their sexual decision making as influenced by their school environment.

Method

Research context

Our mixed method study was conducted in the eastern Zimbabwe District of Manicaland, using a sample of five United Methodist Church (UMC) high schools and five neighbouring secular high schools. The UMC, which originated in the United States, is one of several Christian mission churches with a significant following in the area; others include Catholic and Anglican denominations, which also administer schools. The participant schools were involved in a randomized controlled trial to test whether keeping orphan girls in school reduces HIV risk factors (Hallfors et al., 2011) and whether church schools provide an added measure of protection. The participants in this portion of the study were approximately one year older than participants in the randomized controlled trial; they did not themselves participate in the trial nor were they exposed to an experimental HIV prevention intervention during the study. It was important to access for this study other same school teenagers with orphanhood to provide external the evidence likely to explain any between school type differences in the sexual health outcome measures from the randomized controlled trial. We also sought not to contaminate the responses by the teenagers with orphanhood participating in this study from their having been exposed to the sexual health measures used with the randomized controlled trial.

Participants and Setting

Participants were 125 orphan girls enrolled in Form 2 of high school (Grade 8; Mean age = 14.70 years, SD = .77 years) from the ten schools (see Table 1). A total of 68 (54.4%) were recruited from the five UMC secondary schools and the remainder from the five secular schools. Form 2 students have experienced at least one full year of high school sex education messages and related contextual situations.

Table 1.

Participant Demographics (N=125)

|

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orphan Learner Variables | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| School | Age (In years) | Parents lost | First Sex | Years enrolled | |||||

| 13–14 | 15–17 | One | Two | No | Yes | One | Two | ||

| Type | Secular | 22 | 35 | 32 | 25 | 52 | 4 | 4 | 57 |

| Church | 33 | 35 | 46 | 22 | 65 | 3 | 3 | 68 | |

| Totals | 56 | 69 | 78 | 47 | 117 | 7 | 7 | 125 | |

Inclusion criteria for the study were: females currently enrolled in Form 2 (Grade 8) with one or both biological parents deceased or living with surviving parent or a guardian.

Participants were randomly selected from school rosters of orphans. All were of a Shona cultural background which is the majority cultural group in Zimbabwe. Participant orphans reporting first sex (n=7) in an initial confidential survey were a tiny proportion of the sample (6%); therefore, the sexual experience variable was not included in the analyses.

Data Collection

We used concept mapping (Concept Systems, 2010) which is a mixed method approach for the data collection and analysis (as described below). Concept mapping is an inductive, qualitative-quantitative approach for describing social reality from the view point of the participants. It differs from other mixed method approaches in being both a data collection and analytic procedure. It begins with qualitative inquiry using free listing of concepts which are subsequently clustered thematically for meanings and rated for importance. The concept mapping approach applies both qualitative procedures (as in thematic clustering of free listed statements) and quantitative approaches (with importance ratings of statements) on the same participant generated data. This is unlike mixed method approaches in which qualitative aspects of the data collection may be directed at some questions driving the research inquiry and the quantitative aspects directed at different, albeit complementary questions. With concept mapping, data are captured and linked within the same heuristic model to both describe and characterize social phenomenon in the most parsimonious way possible. The practice to combine quantitative and quantitative approaches typifies mixed method approaches and has been productively utilized in several previous studies (see Pinto, 2012; Pinto & MacKay, 2006 for examples). With concept mapping, data are collected over a relatively short period of time (usually 3–4 short workshops).

Workshops

The first author, who is a certified concept system facilitator, led the workshops. We hosted four half-day focus group workshops with participants at each of the 10 participating schools in order to accomplish the following: 1) brainstorm to generate concept mapping statements; 2) finalize a list of statements; and 3) sort and rank the statements. After an appropriate introduction, we informed the participants that we were interested in learning about influences on their sexual decisions. Brainstorming included both written statements and group discussion of the anonymous statements for clarity and completeness.

The focus statements for the brainstorming were available in both English and Shona. Participants used their preferred language for responding. Allowing participants to respond in a preferred language enhances the chances of capturing the cultural nuances of the received sex and HIV-related messages. The lead and third-listed authors, who are native language speakers of Shona, facilitated the discussions.

Brainstorming

We used three focus statements. The first statement had a faith influence stem intended to prime faith oriented responses in the respondents (A). The second statement assessed perceptions of in-school messages to delay their sexual debut (B). A third statement probe (C) allowed for participants who had indicated prior sexual experience to report on the context of their transition to first sex (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Focus statements by sexual experience and between school settings

| Context | ||

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Church School (A) | Secular School (B) | |

| Condition | ||

| Virgin (A and B) | “You have not engaged in first sex. Complete the following to the best you can to say what most accurately influences your postponement of first sex. UMC sex and HIV-related messages that influenced my decision to postpone first sex were________.” | “You have not engaged in first sex. Complete the following to the best you can to say what most accurately influences your postponement of first sex. In-school sex and HIV-related messages that influenced my decision to postpone first sex were:________” |

| With first sex (C) | “You have engaged in first sex. Complete the following to the best you can to say what most accurately influences you to your first sexual encounter. The influences leading to my first sexual encounter included________” | |

Packets with the focus statement probes contained either probe A and C (if Church school) or B and C (if secular school). Participants self-reported their virginity status on a confidential demographic data form that was provided with the brainstorming statement probe. They then selected the appropriate focus statement from the packet with privacy.

Prior to the main data collection, we piloted focus statement probes with 30 orphan girls from three church and secular schools for readability and credibility. In addition, we sought to determine any quality of statement differences between those by church and secular school students. Process evaluation with the participants suggested that they understood the intent and procedure of the focus statements. The statements by participants from the church schools were similar to those from the secular schools, with the result that for subsequent concept mapping sorting and rating, participants responded to the same list of statements on influences for abstinence or delay of sexual debut.

Following the statement brainstorming with free listing, we collated the statements by the teenagers onto a common list and presented them to the teenagers on a flip-chart or projected from an LCD projector without attribution of the source of the statement. The teenagers were to consider in a focus group discussion format the extent to which the individual statements were clear in meaning to them. We instructed participants to talk in turns and that criticizing others was to be avoided. These two simple procedural rules created an atmosphere in which all participants perceived their contributions to be accepted and valued. The girls eagerly engaged in discussion of the statement to clarify meanings of the free listed statements, resulting in a shorter and clearer list of statements than the initial listing. As examples, raw (or unedited) statements from the brainstorming for sexual abstinence included “Your virginity is something you can boast for (14 year old at church school) ”; “Having sex will lead to preoccupations with sex” (15 year old at secular school); “I do not want to do that [having sex] because it will be abusing myself” (13 year old at church school); “I would like to have sex later as a mature woman”. Those for postponing sex to protect family honour included “ If my mother heard that [I had sex] she will be shocked! (13-year old at secular school); “ I shall not have sex at a young age for my grandmother to be proud of me on getting married a virgin” (14 year old at church school) ; “From having sex i may result with a fatherless child and my carer family would be laughed at by others” (16-year old at secular school”. After editing for completeness and non-duplication of statements by the first and third listed authors, the participants engaged in sorting and rating of the statements.

Sorting and ranking tasks

For the sorting phase, each participant was provided with the bundle of cards with numbered individual statements from the brainstorm session and was asked to group the statements into piles “in a way that make sense to you.” This sorting procedure is like Q-sort methodology (Block, 1961) in prompting participants to sort-group statements to characterize a social experience. The major exception with statement sorting with concept mapping is that the statements are own generated by the participants with brainstorming rather than given from an external source (i.e., research instrument or statement data concourse archive). The resulting thematic clusters are also less predicated on prior theory about the themes to emerge. The concept mapping sorted themes are also not an end in the data aggregation process but a step to their construction and weighting of importance with the ratings data superimposed. These qualities represent a much more rigorous data aggregation and triangulation approach than possible Q-sort methodology alone.

We asked participants to write the number for each statement on a record sheet so that statements grouped together were in the same cluster. Participants provided a short descriptive label for each of the clusters to capture their perceived core meaning for the cluster.

For the ranking task, we presented participants with a list of the brainstormed statements in questionnaire format and asked them to rate each of the statements on a 5-point Likert-type scale on relative importance to their sexual decisions (relatively unimportant = 1 to extremely important = 5).

For generating reliable concept maps, use of concept systems requires at least 11 participants per participant grouping by demographic characteristics (Concept Systems, 2010). Our sample size by school type and variables other than sexual experience far exceeded the minimum required - adding to confidence in the reliability of the data for the analysis (see Table 1).

Procedure

Permission for the study was granted by the Research Council of Zimbabwe, Zimbabwean Ministry of Education, Sports and Culture, and human research ethics institutional review boards for the Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation (USA) and the University of Sydney (Australia). A parent (if with a surviving parent) or guardian (if with no surviving parent or with carer home support) provided written consent and each participant provided written assent to take part in the study. Focus group sessions were conducted during normal school hours; researchers arranged with school administrators for participants to make up missed school work.

Participants used self-selected three letter code identifiers known only to themselves which they retained for the rest of the study. The submission of data by participants to the research team was anonymous and did not carry information traceable to a particular participant. The anonymous, written submission enhanced the chances that participants who were less comfortable sharing their statements publicly (for the discussion component) would be frank about their observations.

Data Analysis

The Concept Systems program Version 4.0 (2010) was used for the data capture and analysis. This program utilizes Multidimensional Scaling (MDS) and Hierarchical Clustering to construct participant driven cluster maps from the participants' statements. Its output includes cluster rating maps (see Figure 1 below) and other descriptive statistics that are usable for further analyses. MDS involves putting all sorted statements data into an aggregated similarity matrix forming an n × n matrix where n = number of statements, with a row and column of the matrix corresponding to each statement. In this case, the x-axis refers to one idea and the y-axis a different idea based on the participant sorting of the statements. Statements that are sorted (or grouped) by participants to belong together in terms of their meaning or contribution to defining a construct are scored “1” and those sorted differently are scored “0”. The aggregated matrix represents the combined relationship of statements to one another. The relationship is visually represented on a distance matrix so that points or ideas sorted by participants to be closer to each other are plotted closer in proximity.

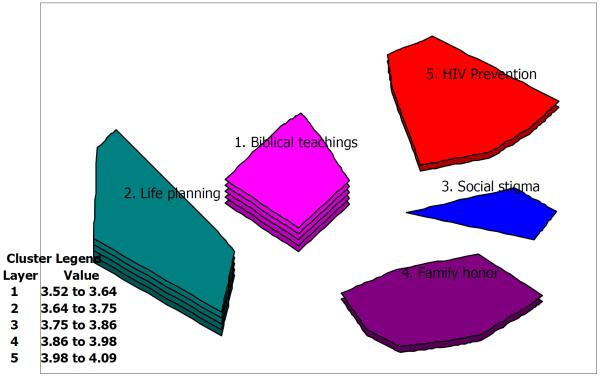

Figure 1.

Cluster rating map for messages perceived to be received by orphan teenage girls that influenced their sexual decisions. Participants rated message statements on the criterion of importance to their sexual decisions. The clusters are color coded for visual differentiation. Higher stacked clusters indicate those considered particularly important to the teens' sexual decisions.

To maximize the difference in statement similarity clusters from the MDS, and to enhance interpretation, a hierarchical cluster analysis with Ward's criterion (Everitt, 1980) is performed on similarity data with the output from the MDS. The cluster map shows the bounded items map based on conceptual proximity from the statement sorting. The data from the statement ratings (1–5) are averaged across persons for each item and the cluster rating map mean ratings for each item displayed as results in vertical column layers.

Necessarily, the specific shape of the cluster boundary is determined by the number and location of the items within each cluster, given the most parsimonious map configuration. The concept system software generates a sten statistic to measure accounted-for variance for cluster solutions. It is interpreted like Wilk's Lambda (λ) in that lower indicator values denote higher accounted-for variance from the specified cluster solution. A sten statistic of .27 was observed for the five factor cluster solution represented in Figure 1; alternative cluster solutions had lower accounted-for variance (in the .30s) and lower interpretability from over-splitting the clusters.

Descriptive data are generated by the Concept Systems software, including graphs representing the underlying structure of the maps (e.g., pattern match). The pattern match represents the mean location of clusters relative to each other. It reports a pearson correlation index which, in this case, is a measure of the degree of agreement between the clusters by group membership. A higher the correlation coefficient denotes a closer similarity in the location or ranking pattern of clusters between groups. We tested for significance of differences between group means at an overall alpha of .05, applying the Dunn-Bonferroni procedure to control for possible inflation of Type 1 error with multiple pair-wise comparisons.

Results

Figure 1 shows the composite cluster rating concept map for perceived received messages that influenced participants' sexual decisions. Each of these clusters comprised indicator statements from the concept mapping brainstorming and sorting which the orphan girl teenagers grouped to be equivalent in defining the specific received influence. The higher stacked clusters portend greater relative importance of the perceived messages than lower stacked clusters. The color coding of the cluster rating map is selected from the concept system software to be similar to that for the pattern match to enable visual analysis of the relative stacking of clusters between groups.

Perceived messages

Regardless of type of school (church versus secular), participants reported the following messages as influential, listed in relative importance from most important (5) to least important (1): Biblical Teachings (M =4.09; SD = 0.21), Life Planning (M =4.05; SD= .27), Family Honour (M =3.73; SD = 0.11), HIV Prevention (M =3.69; SD = .32) and Social Stigma (M =3.52; SD=0.39) (see Figure 1). Biblical Teachings comprised the cluster of messages on scriptural faith teachings about acceptable sexual practices (e.g., abstinence only until marriage, STIs are acquired in sinful liaisons). Life Planning messages included valuing one's future, healthy living, and the importance of education to attaining a future career. Family Honour messages focused on avoiding sexual activity to uphold the respect of the family in the community. HIV Prevention messages were primarily about how to avoid contracting HIV. Social Stigma messages were related to the social consequences expected from engaging in sex and/or becoming pregnant while a teenager in school. Table 3 presents samples of items across the five message clusters.

Table 3.

Sample Statements per Message Cluster with Means and Standard deviations by Type of School

| Mean Score and SD | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Statement by Cluster | Secular School | Church School | |

| Cluster 1. Biblical Teachings (Items N=11; α = .57) | |||

| 6 | Get married before sex | 4.57 (.86) | 4.41 (.95) |

| 13 | The Bible says no to sex at too young an age | 3.98(1.27) | 4.16(1.03) |

| 26 | Pastors discourage sex at our age | 3.64(1.33) | 3.85(1.37) |

| 18 | Sex is for grownups only | 3.58(1.35) | 3.27(1.52) |

| Cluster Mean and SD | 4.21*(.13) | 4.01(.15) | |

| Cluster 2. Life Planning (Items N=11; α = .60) | |||

| 49 | Delay sex to get a good career | 4.35(1.13) | 4.21(1.21) |

| 14 | Maintain a healthy life | 4.10(1.07) | 4.31(1.13) |

| 2 | Concentrate on schooling | 4.04(1.21) | 4.37(1.00) |

| 35 | Premature pregnancy will spoil your future | 4.16(1.21) | 3.82 1.22) |

| Cluster Mean and SD | 3.99(.35) | 4.06(.15) | |

| Cluster 3. Social Stigma (Items N=8; α = .66) | |||

| Sexual intercourse is not acceptable amongst teenagers | 3.87(1.30) | 3.79(1.33) | |

| Falling pregnant would disgrace me with my peers | 3.72(1.33) | 3.48(1.32) | |

| If pregnant, boy friend might refuse you | 2.75(1.47) | 3.17(1.53) | |

| You age quicker with sex | 3.32(1.41) | 3.42(1.34) | |

| Cluster Mean and SD | 3.51(.44) | 3.53(.37) | |

| Cluster 4 Family Honor (Item N=9; α = .69) | |||

| 7 | Getting pregnant would bring shame to family | 3.91(.35) | 3.92 1.05) |

| 45 | If not a virgin, in-laws with send you back to your family | 3.89(1.44) | 3.58(1.50) |

| 30 | Relatives expect sexual abstinence | 4.08(1.36) | 3.87(1.11) |

| 15 | No motherhood while being looked after by parent or guardian | 3.63(1.29) | 3.66(1.27) |

| Cluster Mean and SD | 3.76(.16) | 3.71(.19) | |

| Cluster 5 HIV Prevention (Items N=11; α = .73) | |||

| 1 | You can get HIV from someone infected | 4.18(1.30) | 4.34(1.10) |

| 21 | Sex at a young age could lead to prostitution | 3.72(1.19) | 3.56(1.37) |

| 17 | Avoid being with groups of men | 3.65(1.08) | 3.74(1.26) |

| 28 | You might have an unfaithful partner | 2.98(1.46) | 3.68(1.17) |

| Cluster Mean and SD | 3.73 (.39) | 3.67(.3O) | |

Note. The statement clusters are listed by order of relative mean importance rating (1=High; 5 =Low).

p<.05

Messages perceived to prevent HIV infection was one among several clusters of information that influenced sexual decisions by the teenagers. Messages to prevent HIV were relatively less important consideration than family honour. Nonetheless, in both types of schools, the orphan teenagers highly endorsed the importance of messages on voluntary testing for HIV prior to engaging in a sexual relationship on a five-point scale (e.g., “One [and partner] needs to be tested [for HIV] before having sex to avoid the spread of HIV”), Mchurch school = 4.00, SD=.39, t(df=67)= 31.71, p. < 001, Msecular school =4.08, SD=.30, t(df=56) = 39.76, p. < .001. They also perceived messages about sexually transmitted infection transmission to influence their sexual decisions (e.g., “STIs can spread from having sex”.) Mchurch school = 3.77,SD=.39, t(df=68) = 31.96, p. <. 001, Msecular school =4.04, SD =. 30, t(df=56) = 32.56, p. < .001.

School Type Effects

To determine the influence of type of school on participant's sexual decisions and HIV prevention, we used a concept mapping pattern match split-plot procedure to disaggregate the data by school type. The pattern match represents the mean location of message types relative to each other, and between school types. It reports a correlation index which, in this case, is a measure of the coherence of the pattern map between school types. The higher the correlation, the closer the similarity in the locational or ranking pattern of message clusters between schools. The significant similarity in perceived message clusters between school types (r =.89, p < .001), suggests a reliable basic messages framework to influence sexual decisions among participants. There was no difference in the relative mean ranking of perceived Biblical messages as an influence on the sexual decisions of girls in secular schools (M = 4.21, SD = .13) compared to those in church schools (M = 4.01, SD =.15), t(123) = 7.88, p >.05. Thus, our hypothesis that students in church schools would perceive faith informed messages as their greatest influence while secular school students prioritized mostly non-faith concepts was not supported by the data.

Irrespective of type of school, the orphan girls perceived messages on Biblical Teaching, Life Planning and Family Honour to support their decisions to delay initiation of sexual relationships (see Table 1). Specifically, messages on maintaining virginity were associated mostly with Biblical Teachings (e.g., “The Bible says no to sex at too young an age;” “Pastors discourage sex at our age”). Decisions to postpone initiating sexual relationships until marriage were associated with the cluster of messages on Family Honour. For instance, the girls perceived messages about Family Honour in statements such as “If not a virgin when you get married, you will be sent back to your family by your husband and in-laws”; “Relatives expect sexual abstinence”. Life Planning messages were associated with delaying sex to focus on education (e.g., “Delay sex for a good career”, “Concentrate on schooling”). The need to prevent unwanted pregnancy was a particularly important consideration with the Life Planning and Family Honour messages perceived to be received (e.g., “Premature pregnancy will spoil your future”; “Getting pregnant would bring shame to family”). Nonetheless, the girl orphans also perceived HIV messages to influence their decisions about sexual abstinence, (e.g., “I want to be a mother of healthy children.”; “Some who acquired HIV are now regretting”). The hypothesis that school type would influence perceived messages to initiate sexual relationships was not supported by the findings of the study.

Discussion and Conclusions

Contrary to our hypotheses, students in religious and secular schools did not report different types of messages influencing their sexual decision-making. Surprisingly, girls in secular schools were somewhat more likely to place emphasis on Biblical Teaching messages compared to church school students, although differences were not statistically significant. Our presumption that orphan girls with church school affiliation would be more likely to be influenced by biblical teachings in their sexual decisions more that would those attending secular schools was mistaken. As in other U.S. studies (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011), findings suggest that HIV prevention messages have lower salience among youth compared to other concerns. It should be noted, however, that the vast majority of sampled teenagers had no sexual experience, and HIV risk may have been therefore relatively less important. Although we had no way to verify their claims to virginity, we note that a few of the teenagers did report with first sexual encounter to suggest that our procedure for protecting anonymity was credible with the participants. Thus, we have grounds to be reasonably confident that the findings would be mostly true of similar others with orphan status and attending the same schools.

From a structural theory perspective, the similarities in reported influential messages among students in the two different types of schools suggest a confluence of faith-oriented messages to influence sexual decisions by the teenagers from both the school and general community settings. For example, in a country where almost 80% of adults belong to a Christian church (CSO MACRO, 2007), it is likely that church messages hold considerable influence among youth regardless of their school enrolment. Moreover, staff in both secular- as well as church-run Zimbabwe rural high schools report that they provide biblical teachings as messages to guide students' sexual decision making (Mpofu et al., 2012). These teachings all draw from an orthodox Christian perspective in which sex is only for married heterosexual adults. Thus, although church schools may by their mission emphasize faith-oriented decisions, the teenagers also are exposed to a high dosage of biblical teachings as part of the school curriculum to influence their sexual decisions. They also are exposed to like teachings by the faith community in their homes (Mpofu et al., 2013); - adding to the salience of biblical in their sexual decisions for HIV prevention.

Findings suggest that clear and compelling messages from families were also important to orphan girl participants. For example, many girls reported that their relatives expected sexual abstinence, and that their in-laws would send them back (in disgrace) to their families if they are not virgins when they marry. These are cultural messages about appropriate sexual behaviour by teenagers in the general Zimbabwe Shona community (Gelfand, 1978) and would be the same for teenagers not orphans. The messages about family rejection for sex before marriage are less likely to be taught in school as part of sex and HIV education than by siblings and aunts in the villages (Bourdillon, 1982; Gelfand, 1978), although they may be addressed in the social studies curriculum. These family norms about sexual abstinence for teenagers would apply to all Shona adolescents regardless of orphan status or gender (Gelfand, 1978). Nonetheless, girl orphans in school are vulnerable to social pressures to conform by care takers who may be extended family relations because they may be perceived as “less deserving” of parenting resources than the children of surviving parents (Mutepfa et al., 2008; Nyambedhaa, Wandibbaa & Aagard-Hansenb, 2003; Nyamukapa & Gregson, 2005).

The teenagers with orphanhood perceived their sexual decisions to be influenced by social stigma related to initiating sexual relationships and the risk to acquire an unwanted pregnancy. As noted previously, social stigma may comprise the direct and indirect messages that the teenagers perceive from the community regarding the social consequences of sexual involvement while an orphan (Gregson & Nyamukapa, 2005). Nonetheless, even teenagers without orphanhood would be stigmatized for sex as minors and outside marriage. Thus, community sexual norms may underlie messages that church teachings promote with the teenagers in their sexual decisions. Future studies could explore specific community norms, the contexts in which they are acquired and their influence on sexual decisions by teenage girls with and without orphanhood.

Implications for HIV Prevention Education

Findings suggest that school and future career are important concerns for adolescent orphan girls, and that messages reminding them that sexual intercourse may lead to pregnancy and the end of schooling are salient. In our randomized controlled trial, we found that marriage and pregnancy automatically led to school dropout or school expulsion (Hallfors et al., 2011). Church and secular schools may value and promote HIV prevention messages differently with church schools placing emphasis of presumed Biblical teachings on HIV and AIDS while secular school may be more inclusive in their messages for HIV preventions (Mpofu et al., 2012). Nonetheless, participation in community religious activity would mediate the teenagers' priority HIV prevention messages. Knowledge of the priority that subgroups of teenagers by their communal religious activity place on messages for sexual decisions is important to the design of effective HIV education programs in school settings. A comprehensive life skills education approach addressing life planning, religiosity and family culture influences on sex and HIV education may be more effective in addressing HIV prevention with African students than a program that focused only on sex and HIV education. Furthermore, if school retention is a sexual health protective with orphanhood (Hallfors et al., 2011), then pregnant teenage girls should be supported to continue school, thereby reducing their long-term health risk from a lack of formal education.

Limitations of the Study

First, a limitation of the study design is that the focus statement were not the same across the church and secular school conditions from our mistaken assumption that students in church schools would necessarily report biblical teachings to be more significant in their sexual decisions than would peers in secular schools. A more balanced approach would have been to also probe for church influences on sexual decision among the girls attending secular schools. As a result of this flaw in the study design, the magnitude of church influences on sexual decision making by the girl orphans attending sexual schools may have been underestimated. Second, the study sample included adolescent girl orphans in their second year of high school. From our randomized controlled trial sample, we found that at least 25% of our control group had dropped out of school by the first year of high school (Hallfors et al., 2011). Teenage girl orphans who may have dropped out of school were not included, with the result that their views are missed by the study's findings which represent those of girls with orphanhood retained school. If the girls with orphanhood who dropped out of schools were included, the findings may have been different in some respects. Thus, generalizability is limited to orphan girls still attending school, the majority of whom reported that they are still virgins. Further, findings from rural Zimbabwe participants may not generalize to similar populations in urban areas or in other sub-Saharan countries. Third, the study sampled participants by type of school; construction of concept maps by individual school was not possible as the participant enrolment per school would not yield the minimum number of participants to construct reliable maps. We considered differences within type of school to be random effects, and that assumption may have masked possible between school effects on constructed message maps.

Fourth, the study did not consider possible influences on messages for sexual decisions from peers, including boys who may perceive the teenage girls with orphanhood as likely sexual partners. The fact that the teenage girls were orphaned may make them more vulnerable to pressure by peers to engage in early or unwanted sex than would be the case for others with typical families. Girl orphans with a surviving parent may be qualitatively different from peers who lost both parents in their livelihood supports. For instance, risk for early sexual debut was higher for double than single orphaned Malawian teenagers regardless of sex (Mkandawire & Tenkorang, 2013). Nonetheless, living arrangements with close carer monitoring rather than orphan status per se delayed sexual activity among Kenyan adolescents (Juma et al., 2013). Both the Malawi and Kenya share cultural similarity with Zimbabwe in their child care practices. Future studies should consider how peer influences, living arrangements, and single or double orphanhood may moderate the messages teenage orphan girls perceive to receive from school or community. Consideration of perceived messages by the teenage girls with orphanhood could also be contrasted with those by typical others to place into perspective the extent to which sexual decision making in the age cohort is explained by their orphan status. Future studies could examine perceived social stigma influences among teenage girl orphans as influenced by their subjective evaluation of the quality of home social support.

Conclusion

This study suggests that high school orphan girls perceived Biblical Teachings and Life Planning messages to be important, regardless of school setting. In particular, sexual abstinence to avoid early unwanted pregnancy and to protect future career plans was perceived as highly salient to a large number of orphan girls. These and other messages suggest that rural orphan girls are keenly aware of the present and future consequences of pre-marital sexual behaviour. The design and implementation of credible sex and HIV education services for this vulnerable group may be greatly improved by exploring and supporting protective messages that are particularly salient to them. Future research should include experimentally testing the impact of key school-based messages, informed by the target group of interest, on HIV-related outcomes.

Acknowledgements

The project described was supported by Grant Number R01HD055838 (Denise Hallfors, P.I.) from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute Of Child Health & Human Development or the National Institutes of Health. We also gratefully acknowledge the contributions of our key informants, the orphan students, their families, school and church personnel.

Footnotes

A draft of this report was presented at the International Congress of Applied Psychology at Melbourne, Australia (July 2010).

References

- Agha S, Rossem RV. Impact of a school-based peer sexual health intervention on normative beliefs, risk perceptions, and sexual behavior of Zambian adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2004;34(5):441–452. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basinga P, Bizimana JD, Munyanshongore C. Assessment of the role of forum theatre in HIV/AIDS behavioral change process among secondary school adolescents in Butare Province, Rwanda. International Journal on Disability and Human Development. 2009;8(2):163–173. [Google Scholar]

- Birdthistle I, Foyd S, Machingura A, et al. From affected to infected: Orphanhood and HIV risk among female adolescents in urban Zimbabwe. AIDS. 2008;22(6):759–766. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f4cac7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block J. The Q-sort method in personality assessment and psychiatric research. Charles C. Thomas; Spring-field, IL: 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention HIV among Youth. 2011 http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/youth/; Retrieved June 2012.

- Bourdillon MFC. The Shona peoples: An ethnography of the Shona with special reference to their religion. Mambo Press; Gweru, Zimbabwe: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Brenner L. Controlling knowledge: Religion, power and schooling in a West African Muslim society. Indiana University Press; Bloomington, IN: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- CIA World Factbook - HIV/AIDS adult prevalence rate. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/rankorder/2155rank.html; Retrieved May 2012.

- Concept Systems . Concept Systems Inc; Ithaca, NY, NY: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Everitt B. Cluster Analysis. 2nd ed. Halstead Press; New York: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Gelfand M. The Genuine Shona. Mambo Press; Gweru, Zimbabwe: 1978. 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Gregson S, Nyamukapa CA, Garnett GP, et al. HIV infection and reproductive health in teenage women orphaned and made vulnerable by AIDS in Zimbabwe. AIDS Care. 2005;17(7):785–794. doi: 10.1080/09540120500258029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallfors D, Cho H, Rusakaniko S, et al. Supporting adolescent orphan girls to stay in school as HIV risk prevention: Evidence from a randomized controlled trial in Zimbabwe. American Journal of Public Health. 2011;101(6):1082–1088. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.300042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallfors D, Cho S, Iritani B, Mapfumo J, Mpofu E, Luseno W, January J. Preventing HIV by Providing Support for Orphan Girls to Stay in School: Does Religion Matter? Ethnicity and Health. 2012;18(1):53–65. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2012.694068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen JD. Knowledge in the blood: Confronting race and the apartheid past. University of Cape Town Press; South Africa, Cape Town: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Juma M, Alaii J, Bartholomew LR, et al. Risky Sexual Behavior Among Orphan And Non-Orphan Adolescents In Nyanza Province, Western Kenya. AIDS & Behavior. 2013;17:951–960. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0336-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabiru CW, Orpinas P. Factors associated with sexual activity among high-school students in Nairobi, Kenya. Journal of Adolescence. 2009;32(4):1023–1039. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karmon A. Institution organization of knowledge : The missing link in educational discourse. Teacher's College Record. 2007;109:603–634. [Google Scholar]

- Levers LL, Mpofu E, Ferreira R. HIV and AIDS Counseling. In: Mpofu E, editor. Counseling People of African Ancestry. Cambridge University Press; New York, NY: 2011. pp. 249–264. [Google Scholar]

- Mbizvo MT, Kasule J, Gupta V, et al. Effects of a randomized health education intervention on aspects of reproductive health knowledge and reported behaviour among adolescents in Zimbabwe. Social Science and Medicine. 1997;44(5):573–577. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00204-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mkandawire P, Tenkorang E. Orphan status and first sex among adolescents in Northern Malawi. AIDS & Behavior. 2013;17:939–950. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0120-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mpofu E, Dune TM, Hallfors D, et al. Apostolic faith church organization contexts for health and wellbeing in women and children. Ethnicity and Health. 2011;16(6):551–556. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2011.583639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mpofu E, Mutepfa M, Hallfors D. Mapping Structural Influences on Sex and HIV Education in Church and Secular Schools. Evaluation and the Health Professions. 2012;35(2):346–359. doi: 10.1177/0163278712443962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mpofu E, Ruhode N, Mutepfa M, et al. Submitted for publication. 2013. Resilience among Zimbabwean youths with orphanhood. [Google Scholar]

- Mutepfa MM, Phasha N, Mpofu E, et al. Child-Headed Households in Sub-Saharan Africa. In: Maundeni T, Levers LL, Jacques G, editors. Changing Family Systems: A Global Perspective. Bay Publishing; Gaborone, Botswana: 2008. pp. 328–336. [Google Scholar]

- Nyambedhaa EO, Wandibbaa S, Aagaard-Hansenb J. Changing patterns of orphan care due to the HIV epidemic in western Kenya. Social Science & Medicine. 2003;57(2):301–311. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00359-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyamukapa CA, Foster G, Gregson S. Orphans' household circumstances and access to education in a maturing HIV epidemic in Eastern Zimbabwe. Journal of Social Development in Africa. 2003;18(2):7–25. [Google Scholar]

- Nyamukapa C, Gregson S. Extended family's and women's roles in safeguarding orphans' education in AIDS-afflicted rural Zimbabwe. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;60(10):2155–2167. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne AA, Eckert R. The relative importance of provider, program, school, and community predictors of the implementation quality of school-based prevention programs. Prevention Science. 2010;11(2):126–141. doi: 10.1007/s11121-009-0157-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto RM. Health Education & Behavior. 2012. What Makes or Breaks Provider-Researcher Collaborations in HIV Research? A Mixed Method Analysis of Providers' Willingness to Partner. Published online before print September 14, 2012, doi: 10.1177/1090198112447616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto RM, McKay MM. A mixed method analysis of African American women's attendance at an HIV prevention intervention. Journal of Community Psychology. 2006;34:601–616. [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS Zimbabwe-UNAIDS. 2011 Retrieved on September 6, 2013 from www.unaids.org.

- UNAIDS, UNICEF & USAID Protecting Africa's Future: Livelihood-Based Social Protection for - FAO in Children on the Brink. 2010 Retrieved on September 9, 2013 from www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/tc/tce/pdf/REOSA_Brief1__May2010.pdf.

- Visser MJ, Schoeman JB, Perold J. Evaluation of HIV/AIDS prevention in South African schools. Journal of Health Psychology. 2004;9(2):263–280. doi: 10.1177/1359105304040893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]