Abstract

Early sensing of pathogenic bacteria by the host immune system is important to develop effective mechanisms to kill the invader. Microbial recognition, activation of signaling pathways, and effector mechanisms are sequential events that must be highly controlled to successfully eliminate the pathogen. Host recognizes pathogens through pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs) that sense pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs). Some of these PRRs include Toll-like receptors (TLRs), nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptors (NLRs), retinoic acid-inducible gene-I- (RIG-I-) like receptors (RLRs), and C-type lectin receptors (CLRs). TLRs and NLRs are PRRs that play a key role in recognition of extracellular and intracellular bacteria and control the inflammatory response. The activation of TLRs and NLRs by their respective ligands activates downstream signaling pathways that converge on activation of transcription factors, such as nuclear factor-kappaB (NF-κB), activator protein-1 (AP-1) or interferon regulatory factors (IRFs), leading to expression of inflammatory cytokines and antimicrobial molecules. The goal of this review is to discuss how the TLRs and NRLs signaling pathways collaborate in a cooperative or synergistic manner to counteract the infectious agents. A deep knowledge of the biochemical events initiated by each of these receptors will undoubtedly have a high impact in the design of more effective strategies to control inflammation.

1. Introduction

All living organisms are constantly challenged by microorganisms and a variety of particles (from air pollution and cellular stresses) that represent a health threat. To counteract this burden, the innate immune system needs to react promptly and adequately to eliminate them, while at the same time to preserve tissue normal function. In the last decade there has been an enormous progress in the study of the molecular mechanisms that allow the host to fight against any antigenic stimuli and to keep internal homeostasis. In general, the innate immune host defense includes three essential sequentially events: (1) microbial recognition, (2) activation of signaling pathways, and (3) effector mechanisms.

Hosts are able to recognize distinct PAMPs present in microorganisms through a wide variety of PRRs. To date, a broad range of PRRs have been reported that include TLRs, NLRs, RLRs, and CLRs (for a complete description, see [1]). The different subcellular localization of PRRs and the broad array of PAMPs that can be recognized by them, allows the host to sense a large number of pathogen bacteria and develop an adequate immune response. Upon recognition of PAMPs by PRRs signal transduction pathways are activated that converge on transcription factors, such as NF-κB, AP-1 or IRFs. Activation of these transcription factors regulates the inflammatory and innate immune response through the expression of proinflammatory mediators and antimicrobial effectors. Since some pathogenic bacteria possess PAMPs that can be simultaneously recognized by several PRRs and this leads to the activation of common transcription factors, it is likely that a collaborative response among different signaling molecules may exert regulatory functions after recognition of pathogenic bacteria. Therefore, the aim of this review is to discuss recent findings on the collaborative activity of TLRs and NLRs in the modulation of the inflammatory response induced by virulence factors of pathogenic bacteria.

2. Recognition of Pathogenic Bacteria by the Host

Animals, including humans, respond to a wide range of antigenic stimuli in order to preserve their homeostatic conditions [2]. Professional (macrophages, neutrophils, and dendritic cells) and nonprofessional (epithelial and endothelial cells) phagocytes express various PRRs that recognize PAMPs as well as other nonbiological stimuli [3, 4]. Among the most important PAMPs are lipoteichoic acid (LTA) and peptidoglycan (PGN) from Gram-positive bacteria, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from Gram-negative bacteria, lipoarabinomannan (LAM), lipopeptides, lipoglycans and lipomannans from mycobacteria, glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI), anchored lipids from Trypanosoma cruzi, zymosan isolated from yeast, profilin from Toxoplasma gondii, and DNA from bacteria and mycobacteria [5–8]. To date, a broad range of PRRs have been reported, such as TLRs, NLRs, RLRs, and CLRs.

3. Toll-Like Receptors

TLRs constitute a family of receptors, with different specificities, 10 in humans and 12 in murines. They are able to recognize a structural diversity of PAMPs like glycans, lipids, proteins, lipoproteins, and nucleic acids [9] and are widely known as key players of the inflammatory and innate immune response [10]. TLRs are expressed in various cellular compartments. TLR1, TLR2, TLR4, TLR5, TLR6, and TLR11 are predominantly expressed on the cell surface, although it has been reported that after ligand binding, TLR2 and TLR4 are internalized to phagosomes. TLR3, TLR7, TLR8, TLR9, and TLR13 are expressed in intracellular vesicles such as the endoplasmic reticulum, endosomes, lysosomes, and endolysosomes and mainly recognize nucleic acid [11, 12]. TLRs are expressed in a broad variety of cells such as dendritic cells, macrophages, neutrophils, monocytes, T and B cells, epithelial cells, endothelial cells, fibroblasts, and even neural cells (Table 1) [13–18]; however, each type of cell contains a specific set of TLRs [19–22].

Table 1.

Expression and localization of TLRs and NLRs in cellular types.

| Receptor | Cellular type | Localization | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| TLR1 | Monocytes, mature macrophages, mast cell, and dendritic cells | Cell surface | [191] |

| TLR2 | Monocytes, mature macrophages, and mast cell | Cell surface | [191] |

| TLR3 | Dendritic cells | Endosomes | [191] |

| TLR4 | Predominately in monocytes, mature macrophages, dendritic cells, mast cells, and intestinal epithelial cells | Cell surface | [191] |

| TLR5 | Predominately in intestinal epithelial cells, monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells | Cell surface | [191] |

| TLR6 | Monocytes, mature macrophages, and mast cell | Cell surface | [191] |

| TLR7 | Monocytes, macrophages, and plasmacytoid dendritic cells | Endosomes | [191] |

| TLR8 | Monocytes, macrophages, and mast cells | Endosomes | [191] |

| TLR9 | Monocytes, macrophages, and plasmacytoid dendritic cells | Endosomes | [191] |

| TLR10 | Macrophages, trophoblasts, and intestinal epithelial cells in response to L. monocytogenes | Cell surface, but can colocalize with TLR2 in phagosome | [23–25] |

| TLR11 | Macrophages, dendritic cells, and human embryonic kidney cells | Cell surface and endoplasmic reticulum | [26, 27] |

| TLR12 | Macrophages and dendritic cells | Colocalizes with TLR11 in endoplasmic reticulum | [26, 27] |

| NOD1 | Macrophages, human mononuclear cells, intestinal epithelial cells, and dendritic cells | Intracellularly | [50–52] |

| NOD2 | Macrophages, neutrophils, dendritic cells, Paneth cells, human airway smooth muscle cells, and epithelial and endothelial cells | Intracellularly | [50–52] |

| NLRC4 | Macrophages and gut epithelial cells | Intracellularly | [109, 111, 114] |

| NLRP1 | Lymphocytes, respiratory epithelial cells, and myeloid cells | Intracellularly | [95, 96] |

| NLRP3 | Myeloid cells and human bronchial epithelial cells | Intracellularly | [82] |

Monocytes, mature macrophages, and dendritic cells virtually express all TLRs, while TLR4 and TLR5 are also expressed in intestinal epithelium. Moreover, it has been reported that plasmacytoid dendritic cells and mast cells express TLR7 and TLR8, respectively [19, 23–25]. Interestingly, TLR12 colocalize with TLR11 in endoplasmic reticulum of macrophages [26, 27]. TLR signaling has been shown to be involved in several functions in gut, such as epithelial cells proliferation, IgA production, maintenance of tight junction, antimicrobial peptide expression and pathogen bacteria recognition [20, 28–32]. Airway epithelial cells express TLR1, TLR2, TLR3, TLR4, TLR5, and TLR6 [33–35], although TLR4 has a constitutive expression and intracellular localization [36]. However, TLR7 and TLR9 are only expressed in primary airway epithelial cells [21, 37].

TLRs also play a major role in cutaneous host defense against microorganisms [22, 38]. Normal keratinocytes of the epidermis constitutively express TLR1, TLR2, and TLR5, while TLR3 and TLR4 are barely detectable [38, 39]. However, other work showed evidence that keratinocytes express TLR4 at the mRNA and protein level [40, 41]. Latter it has been shown that keratinocytes respond to double-strand RNA (dsRNA) and express a functional TLR3 [42, 43]. Interestingly, TLR6 and TLR9, but not TLR7 and TLR8 [44], are also expressed by keratinocytes [45].

4. NOD1 and NOD2

NLRs constitute a family of intracellular receptors that detects PAMPs and endogenous molecules. This family contains 16 members that have been categorized into five structurally different subfamilies: NLRA, with an acidic transactivation domain; NLRB, with a baculovirus inhibitor of apoptosis protein repeat; NLRC, with a CARD domain; NLRP, with a Pyrin domain; and NLRX that contains an uncharacterized domain [46]. Probably, the NLRC receptors NOD1 and NOD2 that recognize intracellular bacterial products, as well as NLRPs that respond to multiple stimuli to form a multiprotein complex termed the NALP-inflammasome, are the best characterized so far [47–49] and will be discussed below.

The expression of NLRs has been described in a variety of cellular types (Table 1), for example, NOD1 is ubiquitously expressed in various cell types such as macrophages, human mononuclear cells, intestinal epithelial cells, and dendritic cells, while NOD2 is expressed at higher levels in phagocytic cells and Paneth cells of the small intestine [50–52]. NOD1 and NOD2 have emerged as key pathogen recognition molecules of the innate immune responses [53, 54]. Since the first report of NOD1 as a receptor of invasive Shigella flexneri [55, 56], other works have shown that NOD1 is the receptor involved in the cytosolic recognition of invasive Gram-negative bacteria or PGN delivered into the epithelial cells through outer membrane vesicles (OMV) derived from these types of bacteria or injected through type three secretion systems (TTSS) [57–60]. The participation of NOD1 in Gram-negative bacteria sensing might represent a selective advantage to the host because these types of bacteria are a common threat of the epithelial cells lining the intestinal mucosa [61]. NOD1 and NOD2 have been shown to detect enteric bacteria such as Shigella, Salmonella, Listeria, Yersinia, pathogenic Escherichia coli strains, and Mycobacterium species [62]. The expression of NOD2 has also been associated with the chronic intestinal inflammation in Crohn's disease, where stimulation with muramyl dipeptide (MDP) seems to play an important role [63].

In contrast to NOD1 that is expressed in a wide range of cells and tissues, the expression of NOD2 seems to be restricted to macrophages, neutrophils, dendritic cells, and lung epithelium [64, 65]. Specifically in the lung, several reports have shown that NOD1 is expressed in epithelial cells, endothelial cells, human airway smooth muscle cells, and leukocytes [66–69] and responds to pathogens such as Chlamydophila pneumoniae, Legionella pneumophila, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa [58, 70–73]. NOD2 has been found mainly in macrophages, neutrophils, and bronchial cells [70, 74–76] and senses Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, E. coli, C. pneumoniae, and M. tuberculosis [77–79].

5. NLR Inflammasomes

NLRPs are a subgroup of NLRs constituted by proteins such as NLRP1, NLRP3, NLRP4, NLRP6, NLRP7, and NLRP12 that are involved in the formation of multiprotein complexes termed inflammasomes [80]. These complexes consist of one or two NLR proteins, the adapter molecule apoptosis associated speck-like containing a CARD domain (ASC) and pro-caspase-1 [81]. These inflammasomes might sense several microbial products and a variety of stress and damage associated endogenous signals. Probably the best characterized inflammasome is the one formed by the NLRP3 scaffold, the ASC adaptor and caspase-1 [82], and its expression is induced by inflammatory cytokines and TLR agonists in myeloid cells and human bronchial epithelial cells [82]. As the other inflammasomes, the NLRP3 inflammasome mediates the caspase-1-dependent conversion of pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 to IL-1β and IL-18 and are involved in a form of cell death termed pyroptosis [83].

NLRPs respond to a broad variety of bacteria and it has been shown that NLRP3 is activated by the lung pathogenic microorganisms K. pneumoniae, Listeria monocytogenes [84, 85], S. pneumoniae, S. aureus [86], C. pneumoniae [87], M. tuberculosis [88], L. pneumophila [89], influenza virus [90, 91], Porphyromonas gingivalis [92], Aspergillus fumigatus [93], and Aeromonas veronii [94]. NLRP3 seems to be involved in the host defense against the enteric pathogens Citrobacter rodentium and Clostridium difficile in mice [62]; however, this response is far from being fully characterized.

Although NLRP1 was the first NLR described as a part of an inflammasome, its mechanism of activation is not well studied. It is abundantly expressed in lymphocytes, respiratory epithelial cells, and myeloid cells [95, 96]. The best-characterized activator of NLRP1 is the lethal toxin (LT) from Bacillus anthracis [97]; LT activates caspase-1 and induces rapid cell death via NLRP1 [81]. A recent work showed that NLPR1 inflammasome is activated by T. gondii in mice and rats infection models [98]. NLRP7 is only present in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells after LPS and IL-1β stimulation [99]. Despite its function in bacterial infections the experimental evidence indicates that NLRP7 is activated in macrophages by bacterial lipopeptides and Mycoplasma as well as S. aureus infection, leading to formation of an inflammasome [100].

NLRPs also negatively control the inflammatory response by lowering the NF-κB activation and IFNβ production [101, 102]. They regulate autophagy during group A streptococcal infection by interacting with the autophagy regulator Beclin-1 [103]. On the other hand, NLRP6 inhibits NF-κB signaling downstream of TLRs in macrophages in vitro and mouse in vivo [104], which seems to be important to regulate the immune response against components of the gut microflora [105]. Also it has been described that ablation of Nlrp6 confers resistance to L. monocytogenes and Salmonella typhimurium infections [104]. Although the lack of Nlrp6 gene could be beneficial to control infection caused by these pathogens, it must be studied how its deficiency might affect the gut homeostasis. Another member of the NLRs family NLRP12 functions as a negative regulator of inflammation. It is expressed in myeloid cells and its expression is reduced by TNFα and TLR stimulation [106, 107]. However, a recent report has demonstrated that NLRP12 does not significantly contribute to the in vivo host innate immune response to LPS stimulation, K. pneumoniae infection, or M. tuberculosis [108].

Early experiments revealed that flagellin delivered into the cytosol is an important bacterial component for the activation of the NLRC4 inflammasome independently of TLR5 activation [109]. Besides NLRC4 regulates of host defense by activating caspase-1 and IL-1β/IL-18 secretion in macrophages infected with Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, L. pneumophila, and P. aeruginosa. [110, 111]. S. flexneri, a pathogen bacterium lacking flagellum, also induces the activation of the NLRC4 inflammasome through PrgJ, a protein that forms the basal body rod of the type three secretion system [112–114]. Furthermore, NLRC4 protects the gut from chemically induced acute colitis as well as the mortality caused by dissemination of Salmonella beyond the gut [115].

On the other hand, the absent in melanoma-2 (AIM2) protein is a member of the IFI20X/IFI16 (PYHIN) protein family that binds DNA from virus and bacterial pathogens. Upon DNA sensing, AIM2 triggers the assembly of the inflammasome, leading to caspase-1 activation, IL-1β maturation and pyroptotic cell death [116, 117]. Several studies have shown that AIM2 inflammasome is important in the recognition of DNA from pathogen bacteria, such as Francisella tularensis in macrophages [118], Francisella novicida in dendritic cells [119], L. monocytogenes in macrophages [84, 120–122], Mycobacterium sp. in macrophages [123, 124], S. pneumoniae in macrophages [125], and P. gingivalis in gingival epithelial cells [92]. Even AIM2 inflammasome is a critical molecular platform for regulating IL-1β release and survival during acute central nervous system (CNS) S. aureus infection [126].

6. Signaling Activated in Response to PAMPs

Initially, sensing of pathogenic bacteria by host activate signaling pathways that turn on mechanisms to kill the microorganism [2]. However, when the infection and inflammatory response have been resolved different mechanisms are launched to repair any tissue damage and return to the basal state [127]. This means that initiation, control, and termination of the inflammatory response and infection must be highly regulated. The inflammatory response is under the control of the NF-κB, AP-1 or IRFs transcription factors, which driving the expression of genes that mediate several processes such as cell proliferation and release of antimicrobial molecules and cytokines that regulate the immune response [128]. In the following sections, the signaling mechanisms activated by TLRs, NLRs, and the collaborative action of both are discussed.

6.1. TLRs Signaling

TLR signaling pathways have been studied and reviewed extensively and it is known that they play a crucial role against pathogenic microbial infection through the induction of inflammatory cytokines and type I interferons (Type I IFNs) [11, 129, 130]. TLR signaling is activated in a myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88- (MyD88-) dependent and TIR-containing adaptor-inducing IFN-β- (TRIF-) dependent manner, with MyD88 signaling predominantly leading to the activation of NF-κB, while TRIF signaling leading to both interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) and, to a lesser extent, NF-κB activation (Figure 1) [131, 132].

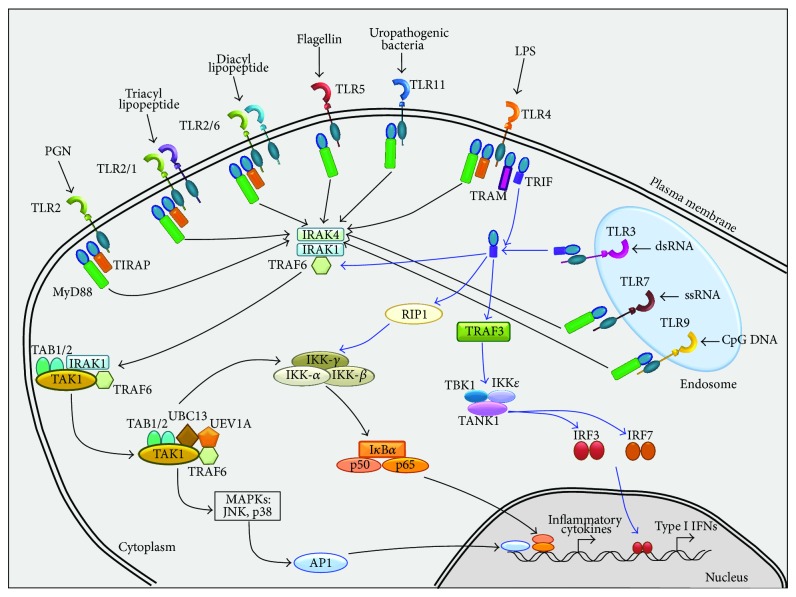

Figure 1.

TLRs signaling. TLR signaling is activated in a MyD88-dependent (black arrows) and TRIF-dependent (blue arrows) manner. MyD88 signaling leads to NF-κB activation, while TRIF signaling leads to both IRF3 and NF-κB activation. In the MyD88-dependent ubiquitination of TRAF6 is important to activate MAPKs (JNK, p38 and ERK) or IKK complex to induce the translocation of NF-κB to the nucleus. The TRIF-dependent signaling pathway can activate NF-κB, IRF3, and IRF7.

TLRs have an extracellular leucine-rich repeat (LRR) domain, a transmembrane domain and a cytoplasmic Toll/IL-1 receptor (TIR) domain. The LRR domain of TLRs is involved in the recognition of proteins (e.g. flagellin and porin from bacteria), carbohydrates (e.g. zymosan from fungi), lipids (LPS), lipid A, and lipoteichoic acid (LTA from bacteria), nucleic acids (CpG-containing DNA from bacteria and viruses and viral RNA), protein or peptide derivatives (lipoprotein and lipopeptides from various pathogens), lipid derivatives (LAM from mycobacteria), profilin from T. gondii, and diacyl-lipopeptides from mycoplasma [3, 133, 134]. On the other hand, the TIR domain of TLRs shows homology with the cytoplasmic region of the IL-1 receptor and interacts with TIR-domain-containing adaptors such as MyD88, TIR-containing adaptor protein (TIRAP), TRIF and TRIF-related adaptor molecule (TRAM) [135]. In the MyD88 signaling pathway, stimulation of TLRs triggers its association with MyD88, which in turn recruits IL-1R-associated kinase 4 (IRAK4), allowing the assembly of IRAK1. IRAK4 then induces the phosphorylation of IRAK1, which in turn interacts with tumor-necrosis-factor receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6). Phosphorylated IRAK1 and TRAF6 then dissociate from the receptor and form a complex with transforming-growth factor-β-activated kinase 1 (TAK1), TAK1-binding protein 1 (TAB1), and TAB2 at the plasma membrane, promoting the phosphorylation of TAB2 and TAK1. IRAK1 is degraded at the plasma membrane and the remaining complex, consisting of TRAF6, TAK1, TAB1, and TAB2, associates with the ubiquitin ligases, ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme 13 (UBC13) and ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2 variant 1 (UEV1A) in the cytosol. Ubiquitination of TRAF6 induces the activation and phosphorylation of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), p38, extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), and the inhibitor of nuclear factor-κB- (IκB-) kinase (IKK) complex, which consists of IKK-α, IKK-β, and IKK-γ (also known as IKK1, IKK2, and NEMO, resp.) [131, 132, 135]. The IKK complex then phosphorylates the inhibitor of NF-κB (IκB), which leads to its ubiquitination and subsequent degradation by the proteasome 26S, allowing the translocation of NF-κB to the nucleus and expression of inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, costimulatory molecules, and other effectors necessary to build up the host cell “weapons” against the invading pathogen [129, 136, 137]. The variety of genes induced to express by TLRs may be due to the existence of several adaptors that possess TIR domains. Except for TLR3 all TLRs recruit MyD88 and only TLR1, TLR2, TLR4, and TLR6 recruit the additional adaptor TIR-domain-containing adaptor protein (TIRAP, also known as MyD88-adaptor-like protein, MAL) that functions as a bridge between the TIR domain and MyD88 [1, 131, 135, 138].

Apart from the activation of NF-κB and MAP kinases, the TRIF-dependent signaling pathway also induces the activation of IFNβ. TRIF contains a Rip homotypic interaction motif (RHIM) in its C-terminal region that mediates the interaction with members of the receptor-interacting protein (RIP) family. It was observed that TRIF activates NF-κB either by direct interaction with TRAF6 or through RIP-1. Both TRIF/RIP-1 and TRIF/TRAF6 pathways converge at the IKK complex to achieve maximum activation of NF-κB-dependent gene expression. Expression of the IFNβ gene is controlled by cooperative activation of NF-κB, ATF2/c-Jun, IRF3, and IRF7. Activation of TRAF3 by TRIF is important to generate a link between TRIF and TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1, also known as NF-κB activating kinase, NAK), and this in turn activates TBK1 and IKKε. TBK1 and IKKε then activate these two molecules that are responsible for the activation of TRAF family member-associated NF-κB activator (TANK), which phosphorylates IRF3 and IRF7. Phosphorylated IRF3 and IRF7 form homodimers and move to the nucleus where it binds to IFN-stimulated response elements (ISRE), resulting in the production of type I IFNs and IFN stimulatory genes (ISGs) [4, 139–142]. Although IRF7 is considered as the master regulator of IFN-α response [143], IRF5 also seems to function downstream of TLR7 or TLR9, and perhaps TLR8 signaling, although its expression is mainly restricted to B cells, macrophages, monocytes and dendritic cells where can induce de INF-α production [144, 145]. Moreover, IRF1 has been identified as a downstream signaling element of TLR7 in dendritic cell infected with Candida albicans [146, 147].

6.2. NLRs Signaling

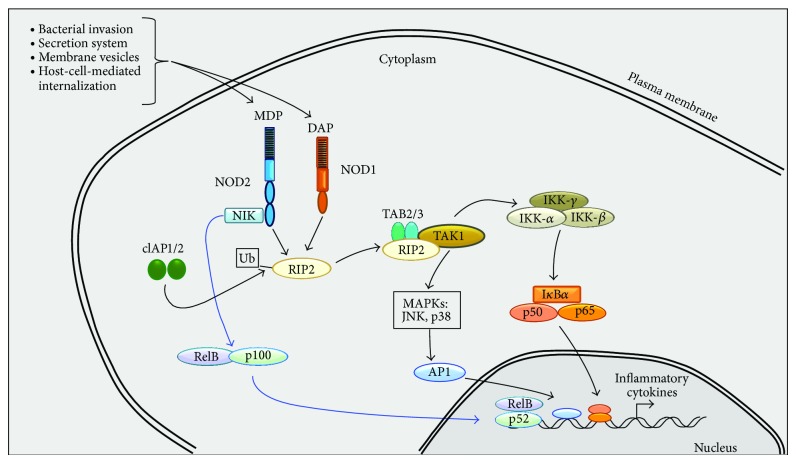

As stated above, the NLRs NOD1 and NOD2 regulate proinflammatory cytokine expression induced by intracellular bacterial ligands. NOD1 recognizes mainly Gram-positive PGN fragments containing the N-acetylglucosamine-N-acetylmuramic acid tripeptide motif with diaminopimelic acid (DAP). NOD2 detects muramyl dipeptide (N-acetylmuramic acid-L-alanyl-D-isoglutamine), which is a motif common of PGN from both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria [148–152]. In general, NLRs possess a C-terminal LRR domain, often involved in ligand recognition, a central NOD, and a variable N-terminal effector domain that is used to classify NLRs [153]. Once bacteria or their components reach the host cytosol by phagocytosis, invasion, membrane vesicles, or secretion systems, the interaction of NLRs with PGN takes place [60, 154], although whether it is a direct or indirect contact is still unclear. However, it has been well documented that the inflammatory response initiated by NOD1 and NOD2 induces the expression of proinflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and antimicrobial peptides by activating NF-κB and AP-1 (Figure 2) [153, 155–157]. A direct interaction between NOD2 and NF-κB-inducing kinase (NIK) that triggers the p100/p52-dependent induction of the noncanonical NF-κB pathway was demonstrated by Pan et al. [158]. Although the NLR signaling pathway is far from being fully characterized the general model shows that sensing of PGN leads to transient recruitment of RIP-2 through CARD-CARD interaction [151, 159–161]. The RIP-2 recruitment leads to IKK complex activation and the subsequent NF-κB activation through phosphorylation and ubiquitination of IκBα, inducing proinflammatory cytokines production [51, 162, 163]. Moreover, recruitment of RIP-2 by NOD1 also activates JNK [164], and NOD1/2 seems to participate in the activation of the type I IFN pathway [165]. Cellular inhibitor of apoptosis protein 1 and 2 (cIAP1 and cIAP2) are E3 ubiquitin ligases important for ubiquitination of RIP-2 and for signaling downstream of both NOD1 and NOD2. Polyubiquitinated RIP-2 favors the recruitment and activation of the TAK1-TAB2/3 complex. TAK1 in turn phosphorylates and activates the MAPKs p38/JNK and NF-κB pathways, leading to cytokine, chemokine, and antimicrobial peptide production [154, 160, 166, 167].

Figure 2.

NOD1 and NOD2 signaling. Bacteria or their components reach the cytosol by several mechanisms. The interaction between NOD2 and NIK (blue arrows) activates the noncanonical NF-κB pathway (p100/p52-dependent). While binding of PGN to LRR domain of NLRs leads to recruitment of RIP-2 through CARD-CARD interaction (black arrows). Ubiquitination of RIP-2 favors, on the one hand, the activation of the MAPKs p38/JNK, and on the other hand activates IKK complex, which induces the activation of NF-κB.

7. Combined Response of TLRs and NLRs Signaling

As it was explained earlier TLRs and NLRs regulate the cytokine and chemokine expression in response to bacterial ligands through their respective signaling pathways [72, 168, 169]. It is likely that TLRs and NLRs act in a collaborative/synergistic, complementary, or compensable manner, with the aim to increase the sensitivity to detect and efficiently eliminate pathogenic bacteria. A number of reports that analyze the interaction between TLRs and NLRs have been published (Table 2). In human monocytic THP-1 cells a marked synergistic secretion of IL-8 was induced by synthetic agonists of NOD1/2 and TLR2/4/9. This enhanced IL-8 mRNA expression and NF-κB activation was suppressed in NOD1 and NOD2 genes silenced monocytes [170]. This synergism between NOD1/2 and TLRs was also observed in the production of antimicrobial peptides PGN recognition proteins (PGRPs) and β-defensin 2 in human oral epithelial cells via NF-κB [171]. Interestingly, costimulation of NOD1/2 and TLRs did not have any effect on IL-8 production, which suggests a cell-type specific inflammatory response. Likewise, in human monocytes and dendritic cells the NOD1/2 ligands, DAP and MDP, respectively, exert a synergetic activity with LPS in the expression of proinflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-8 [172]. The synergistic effect of MDP and TLR2/3/4 ligands on IL-6 and IL-12p40 expression was also observed in wild type and NOD2−/− macrophages, via NF-κB, p38 and ERK signaling pathways [173]. Additionally, treatment of human dendritic cell (DC) with MDP and the NOD1 agonist FK565 along with TLR3/4/9 agonists synergistically induced IL-12p70 and INF-γ production [174]. Another NOD1 ligand M-TriDAP markedly increased the response induced by LPS for multiple cytokines such as IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-4, IL-6, GM-CSF, IL-10, and TNF-α. In the same study carried out by van Heel et al. [175] a strong synergistic increase in IL-1β production was observed for TLR1/2, TLR2/6, TLR4, TLR5, and TLR7/8 ligands (Pam3CysLys4; MALP2; LPS; flagellin from S. typhimurium and R-848, resp.) combined with M-TriDAP. Assays performed with homozygotic macrophages for the 3020insC mutation and/or TLR2−/− mice demonstrated that the NOD2 ligand MDP has a synergistic effect on the induction of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-10 upon costimulation with specific TLR2 agonists Pam3Cys and MALP2 [176].

Table 2.

Analysis of the collaborative action of TLRs and NRLs using synthetic agonists.

| Cell type | Chemical agonist used | Receptors involved | Cellular response |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human monocytic leukemia THP-1 | iE-DAP and MDP Pam3CSSNA, LA-15-PP, CpG DNA |

NOD1 and NOD2 TLR2, 4 and 9 |

NF-κB activation, IL-8 mRNA expression and secretion of IL-8 |

|

| |||

| Human oral epithelial HSC-2 | FK156 and MDP FSL-1, Poly I:C, LA-15-PP, Poly U and CpG DNA |

NOD1 and NOD2 TLR2, 3, 4, 7 and 9 |

NF-κB activation, and production of PGRPs and β-defensin 2 |

|

| |||

| Human embryonic kidney HEK293T and human monocytes | MtriDAP and MDP or MtriLYS Pam3CSK4 and LPS preparations from Escherichia coli O111:B4 |

NOD1 and NOD2 TLR2 |

Release of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-8 |

|

| |||

| Bone marrow-derived mice macrophages | MDP Pam3CSK4, Poly I:C and LPS |

NOD2 TLR2, 3 and 4 |

Activation of NF-κB, p38 and ERK. Production of IL-6 and IL-12p40 |

|

| |||

| Human dendritic cells | FK565 and MDP Poly I:C, LA-15-PP, and CpG DNA |

NOD1 and NOD2 TLR3, 4 and 9 |

Production of IL-12p70, IL-15, and IFN-γ |

|

| |||

| Human blood mononuclear cells | MtriDAP LPS, MALP2, Pam3CysLys4, Flagellin from Salmonella typhimurium and R-848 |

NOD1 TLR4, 2/6, 1/2, 5 and 7/8 |

Secretion of TNF-α, IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, and GM-CSF |

|

| |||

| Human homozygotic macrophages (3020insC mutation) | MDP Pam3Cys and MALP2 |

NOD2 TLR2 |

Production of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-10 |

|

| |||

| Murine and human CD8 T cells | iE-DAP Pam3CSK4 |

NOD1 TLR2 |

Activation of NF-κB, p38 and JNK Secretion of TNF-α, IL-2, and, IFN-γ Induction of cellular proliferation and expansion |

|

| |||

| Monocyte derived-dendritic cells | iE-DAP and MDP LPS and R848 |

NOD1 and NOD2 TLR4 and 7/8 |

Secretion of IL-1β and IL-23; expression of SOCS2 |

In a more recent work, it was shown that NOD1 and TLR2 cooperate to enhance human CD8 T cells proliferation and expansion, and this cooperating action caused an enhanced secretion of IL-2, IFN-γ, and TNF-α that was related to increased activation of NF-κB, JNK, and p38 signaling pathways [177]. Simultaneous stimulation of monocytes-derived DC with NOD1 and NOD2 ligands combined with TLR7/8 or TLR4 agonists results in highly increased production of IL-1β and IL-23 and expression of the inhibitor suppressor of cytokine signaling 2 (SOCS2), where the NOD1/TLR agonists combination was more relevant for the synergistic activity observed [178]. Altogether, these results clarify the existence of a cooperative action of TLRs and NLRs, which become relevant in the context of infection by bacteria that can be recognized by extra- and intracytosolic receptors. Ferwerda et al. [179] demonstrate that TLR2 and NOD2 are two nonredundant receptors that sense M. tuberculosis. They found a synergistic action between these two receptors for cytokine expression that was lost in cells from individuals homozygous for NOD2 3020insC mutation or macrophages harvested from TLR2−/− mice (Table 3). The same authors also found that macrophages from TLR2 and TLR4 knockout mice and NOD2 mutant had a decreased production of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-10, which suggest that collaborative activity of these PRRs is important to balance the amount of pro- and anti-inflammatory response in M. paratuberculosis infection [179]. Evidence on the collaborative activity between TLR2 and NOD2 was obtained by measuring IL-10 secreted from macrophages challenged with S. pneumoniae cell-wall (PnCW) fragments [180]. Interestingly, in this IL-10 production participated the protein adaptors RIP-2 and MyD88, reflecting that both canonical signaling pathways were involved. Infection of mice mesothelial cells (MC) with L. monocytogenes caused an increased production of CXCL1 and CCL2 chemokines, which was notably decreased in MC deficient in NOD1 and RICK [160].

Table 3.

Analysis of the collaborative action of TLRs and NRLs in response to pathogenic bacteria.

| Organism/Cell type | Pathogen bacteria | Receptors involved | Cellular response evaluated |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human homozygotic macrophages (3020insC mutation) and macrophages from TLR2−/− or WT mice | Mycobacterium tuberculosis | NOD2 and TLR2 | Production of TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 |

|

| |||

| Human homozygotic macrophages (3020insC mutation) and macrophages from TLR2−/−, TLR4−/−, MyD88−/− or WT mice | Mycobacterium paratuberculosis | NOD2, TLR2 and TLR4 | Production of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-10 |

|

| |||

| Bone marrow-derived macrophages from TLR2−/−, NOD2−/− or WT mice | Streptococcus pneumoniae cell wall (PnCW) | NOD2 and TLR2 | Production of IL-10 |

|

| |||

| Mesothelial cells from RICK−/−, NOD1−/− or WT mice | Listeria monocytogenes | NOD1 and TLR2 | Production of CXCL1 and CCL2 |

|

| |||

| NOD1−/−, NOD2−/−, RIP2−/− or WT mice | Chlamydophila pneumoniae | NOD1, NOD2, TLR2 and TLR4 | Expression of iNOS, production of NO, IL-6, IL12p40 and IFN-γ, and bacterial clearance |

|

| |||

| NLRC4−/−/TLR5−/− or WT mice | Legionella pneumophila | NLRC4 and TLR5 | Bacterial clearance, recruitment of neutrophils |

|

| |||

| MyD88−/−, RIP2−/−, WT mice or with nonfunctional Naip5 gene | Legionella pneumophila | NLRC4, TLR2, TLR5 and TLR9 | Replication and dissemination of bacteria, rates of mortality and production of IL-6 |

|

| |||

| NOD1−/−, NOD2−/−, NLRP3−/−, NLRC4−/−, Casp1−/−, Asc−/−, TLR2−/− or WT mice | Helicobacter pylori | NOD2, TLR2 and NLRP3 | Production of IL-1β and NLRP3 activation |

|

| |||

| BALB/c mice and human monocyitic leukemia THP-1 | Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium | NOD1 and TLR5 | Bacterial clearance and production of IL-5, IL-6, IL-13, IL-21, IL-22, TNF-α and β-defensin 3 |

|

| |||

| Dendritic cell Keratinocytes from oral epithelium |

Staphylococcus aureus | NOD2 and TLR2 | Production of IL-6 and IL-1β |

|

| |||

| Mice double deficient in Myd −/− Trif −/− | Vibrio vulnificus and Vibrio cholerae | TLRs and NLRP3 | Activation of NF-κB |

|

| |||

| Mice and primary monocytes | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | TLR5 and NLRC4 | Autophagy and production of IL-17, IL-18 and Type I IFN |

C. pneumoniae, which is a common pathogen that causes pneumonia in humans can be recognized by TLR2 and TLR4 [181], as well as by NOD1/2 [70]. Sensing of C. pneumoniae by these receptors induced a reduction in the expression of IL-6, IL-12p40, and IFN-γ in RIP-2−/− mice at day 3 after infection compared with wild-type mice. However, at days 5 and 14 after infection, the production of these cytokines was significantly increased in wild-type mice, indicating an initial impaired and delayed kinetics of cytokine production in C. pneumonia-infected RIP-2−/− mice. Thus, the collaborative activity of both NLRs and TLRs is fundamental for efficient pathogen bacterial clearance. This idea has been supported by later experiments in which NLRC4 was necessary to eliminate L. pneumophila, while TLR5 was necessary to recruit neutrophils [182]. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that activation of RIP2-, MyD88-, and Naip5/NLRC4-dependent signaling pathways triggers a coordinated and synergistic response that protects the host against lethal infection by L. pneumophila [183]. However, contrasting results were observed in P. aeruginosa macrophage infection, since NLRC4 and caspase-1 activation attenuated the autophagy activated by TLR5 and reduced the type I interferon production [184], besides NLRC4 dampens a beneficial IL-17-mediated antimicrobial host response through IL-18 secretion [185].

On the other hand, in DCs infected with Helicobacter pylori, the cooperative interaction between TLR2 and NOD2 showed to be important for IL-1β production and NLRP3 activation. This cooperative interaction in H. pylori infection was confirmed in IL-1β- and IL-1 receptor-deficient mice in which the clearance of bacteria from the stomach was impaired compared with wild-type mice [186]. Costimulation of BALB/c mice with NOD1 and TLR5 ligands showed to be important for efficient S. enterica clearance and improved mice survival. This effect was accompanied with an increase in IL-5, IL-6, IL-13, IL-21, IL-22, TNF-α, and β-defensin 3 in small intestine [187]. More evidence of NOD2 and TLR2 cooperative action was obtained in DC stimulated with PGN from S. aureus [188]. Analysis of IL-6 and IL-1β production, revealed an additive effect of both receptors in keratinocytes from murine oral epithelium, since in TLR2- or NOD2-deficient keratinocytes the cytokine release was decreased by approximately 50% compared to wild-type cells [189]. Infection of mouse macrophages with Vibrio vulnificus and Vibrio cholerae revealed the activation of caspase-1 via the NLRP3 inflammasome [190]. In this work, experiments made with mice doubly deficient in MyD88 and TRIF (Myd −/− Trif −/−), demonstrated that NLRP3 activation required NF-κB-dependent TLR stimulation. Altogether, these results indicate that several sensors are necessary to fight against pathogenic bacteria. Moreover, the specific combination of PRRs seems to be coordinated according to the bacteria or PAMPs involved, which subsequently affect the host response by driving collaborative/synergistic activity.

8. Final Considerations

Most studies have focused on the characterization of the inflammatory response triggered by several virulence factors alone. However, it is important to take into account that in physiological conditions the participation of several PRRs that respond to different PAMPs could be more effective for the host to combat infections. Regarding this issue, the experimental evidence accumulated so far has pointed out that the host response against pathogenic bacteria may be the sum of several pathways induced by the recognition of different PAMPs by different PRRs, which in turn trigger and shape the subsequent innate and adaptive immune responses. Although synergistic activity among NLRs and TLRs has been demonstrated, the subjacent mechanisms are not clear. Both receptors are able to activate NF-κB, MAPKs, AP-1, or IRFs signaling pathways; however, the molecules that are involved in the synergistic activation of these pathways have not been identified. Then, for a better understanding of the molecular mechanisms by which NLRs and TLRs collaborate, this synergistic activity will have to be further analyzed. Since TRLs and NLRs play a fundamental role in the eradication of invading pathogen microorganisms through the induction of inflammatory and antimicrobial peptides, this collaborative activity could be exploited to modulate or improve the host response against pathogenic bacteria that causes an exacerbated inflammatory response.

Finally, there is a growing interest in targeting these PRRs for the treatment of sepsis, but also to fight against inflammatory diseases such as cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, and systemic lupus erythematosus [191, 192]. Several approaches, like ligand mimetics to activate PRRs and antibodies or molecules to inhibit them, have been used to identify therapeutics targets [193]. However, something that should be taken into account in the development of these strategies is the collaborative activity among different PRRs.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología México (CONACYT-México) for supporting this work through a Grant no. 152518 to Víctor M. Baizabal-Aguirre. Javier Oviedo-Boyso was a fellow of a Retention Program from CONACYT-México.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Kumar H., Kawai T., Akira S. Pathogen recognition in the innate immune response. Biochemical Journal. 2009;420(1):1–16. doi: 10.1042/BJ20090272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ayres J. S., Schneider D. S. Tolerance of infections. Annual Review of Immunology. 2012;30:271–294. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-075030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kumar H., Kawai T., Akira S. Toll-like receptors and innate immunity. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2009;388(4):621–625. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.08.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kumar S., Ingle H., Prasad D. V. R., Kumar H. Recognition of bacterial infection by innate immune sensors. Critical Reviews in Microbiology. 2013;39(3):229–246. doi: 10.3109/1040841X.2012.706249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takeuchi O., Kawai T., Mühlradt P. F., Morr M., Radolf J. D., Zychlinsky A., Takeda K., Akira S. Discrimination of bacterial lipoproteins by Toll-like recepttor 6. International Immunology. 2001;13(7):933–940. doi: 10.1093/intimm/13.7.933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zähringer U., Lindner B., Inamura S., Heine H., Alexander C. TLR2 - promiscuous or specific? A critical re-evaluation of a receptor expressing apparent broad specificity. Immunobiology. 2008;213(3-4):205–224. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krishna S., Ray A., Dubey S. K., Larrouy-Maumus G., Chalut C., Castanier R., Noguera A., Gilleron M., Puzo G., Vercellone A., Nampoothiri K. M., Nigou J. Lipoglycans contribute to innate immune detection of mycobacteria. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028476.e28476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blanc L., Castanier R., Mishra A. K., Ray A., Besra G. S., Sutcliffe I., Vercellone A., Nigou J. Gram-positive bacterial lipoglycans based on a glycosylated diacylglycerol lipid anchor are microbe-associated molecular patterns recognized by TLR2. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081593.e81593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akira S., Uematsu S., Takeuchi O. Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell. 2006;124(4):783–801. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Medzhitov R. TLR-mediated innate immune recognition. Seminars in Immunology. 2007;19(1):1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kawai T., Akira S. The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: update on toll-like receptors. Nature Immunology. 2010;11(5):373–384. doi: 10.1038/ni.1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anwar M. A., Basith S., Choi S. Negative regulatory approaches to the attenuation of Toll-like receptor signaling. Experimental and Molecular Medicine. 2013;45:1–14. doi: 10.1038/emm.2013.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Langefeld T., Walid M., Ghai R., Chakraborty T. Toll-like receptors and NOD-like receptors: domain architecture and cellular signalling. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 2009;653:48–57. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-0901-5_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richez C., Blanco P., Rifkin I., Moreau J.-F., Schaeverbeke T. Role for toll-like receptors in autoimmune disease: the example of systemic lupus erythematosus. Joint Bone Spine. 2011;78(2):124–130. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2010.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xi Y., Shao F., Bai X. Y., Cai G., Lv Y., Chen X. Changes in the expression of the Toll-like receptor system in the aging rat kidneys. PLoS One. 2014;9(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096351.e96351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.He X., Jing Z., Cheng G. MicroRNAs: new regulators of toll-like receptor signalling pathways. BioMed Research International. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/945169.945169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jayakumar A. R., Tong X. Y., Curtis K. M., Ruiz-Cordero R., Abreu M. T., Norenberg M. D. Increased Toll-like receptor 4 in cerebral endothelial cell contributes to the astrocyte swelling and brain edema in acute hepatic encephalopathy. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2014;128(6):890–903. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klonowska-Szymczyk A., Wolska A., Robak T., Cebula-Obrzut B., Smolewski P., Robak E. Expression of toll-like receptors 3, 7, and 9 in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Mediators of Inflammation. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/381418.381418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O'Neill L. A. J., Hennessy E. J., Parker A. E., O'Neill L. A. J. Targeting toll-like receptors: emerging therapeutics? Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2010;9(4):293–307. doi: 10.1038/nrd3203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abreu M. T. Toll-like receptor signalling in the intestinal epithelium: how bacterial recognition shapes intestinal function. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2010;10(2):131–144. doi: 10.1038/nri2707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ioannidis I., Ye F., McNally B., Willette M., Flaño E. Toll-like receptor expression and induction of type I and type III interferons in primary airway epithelial cells. Journal of Virology. 2013;87(6):3261–3270. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01956-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pasparakis M., Haase I., Nestle F. O. Mechanisms regulating skin immunity and inflammation. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2014;14(5):289–301. doi: 10.1038/nri3646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mulla M. J., Myrtolli K., Tadesse S., Stanwood N. L., Gariepy A., Guller S., Norwitz E. R., Abrahams V. M. Cutting-edge report: TLR10 plays a role in mediating bacterial peptidoglycan-induced trophoblast apoptosis. The American Journal of Reproductive Immunology. 2013;69(5):449–453. doi: 10.1111/aji.12065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Regan T., Nally K., Carmody R., Houston A., Shanahan F., MacSharry J., Brint E. Identification of TLR10 as a key mediator of the inflammatory response to Listeria monocytogenes in intestinal epithelial cells and macrophages. The Journal of Immunology. 2013;191(12):6084–6092. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1203245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee S. M. Y., Kok K.-H., Jaume M., Cheung T. K. W., Yip T.-F., Lai J. C. C., Guan Y., Webster R. G., Jin D.-Y., Malik Peiris J. S. Toll-like receptor 10 is involved in induction of innate immune responses to influenza virus infection. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111(10):3793–3798. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1324266111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Andrade W. A., Souza M. D. C., Ramos-Martinez E., Nagpal K., Dutra M. S., Melo M. B., Bartholomeu D. C., Ghosh S., Golenbock D. T., Gazzinelli R. T. Combined action of nucleic acid-sensing toll-like receptors and TLR11/TLR12 heterodimers imparts resistance to toxoplasma gondii in mice. Cell Host and Microbe. 2013;13(1):42–53. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roach J. C., Glusman G., Rowen L., Kaur A., Purcell M. K., Smith K. D., Hood L. E., Aderem A. The evolution of vertebrate Toll-like receptors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102(27):9577–9582. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502272102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cario E., Podolsky D. K. Differential alteration in intestinal epithelial cell expression of Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3) and TLR4 in inflammatory bowel disease. Infection and Immunity. 2000;68(12):7010–7017. doi: 10.1128/IAI.68.12.7010-7017.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gewirtz A. T., Navas T. A., Lyons S., Godowski P. J., Madara J. L. Cutting edge: bacterial flagellin activates basolaterally expressed TLR5 to induce epithelial proinflammatory gene expression. The Journal of Immunology. 2001;167(4):1882–1885. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.4.1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Otte J. M., Cario E., Podolsky D. K. Mechanisms of cross hyporesponsiveness to Toll-like receptor bacterial ligands in intestinal epithelial cells. Gastroenterology. 2004;126(4):1054–1070. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shang L., Fukata M., Thirunarayanan N., Martin A. P., Arnaboldi P., Maussang D., Berin C., Unkeless J. C., Mayer L., Abreu M. T., Lira S. A. TLR signaling in small intestinal epithelium promotes B cells recruitment and IgA production in lamina propria. Gastroenterology. 2008;135(2):529–538. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lavelle E. C., Murphy C., O'Neill L. A. J., Creagh E. M. The role of TLRs, NLRs, and RLRs in mucosal innate immunity and homeostasis. Mucosal Immunology. 2010;3(1):17–28. doi: 10.1038/mi.2009.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sha Q., Truong-Tran A. Q., Plitt J. R., Beck L. A., Schleimer R. P. Activation of airway epithelial cells by toll-like receptor agonists. The American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology. 2004;31(3):358–364. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2003-0388OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mayer A. K., Muehmer M., Mages J., Gueinzius K., Hess C., Heeg K., Bals R., Lang R., Dalpke A. H. Differential recognition of TLR-dependent microbial ligands in human bronchial epithelial cells. The Journal of Immunology. 2007;178(5):3134–3142. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.5.3134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koff J. L., Shao M. X. G., Ueki I. F., Nadel J. A. Multiple TLRs activate EGFR via a signaling cascade to produce innate immune responses in airway epithelium. American Journal of Physiology: Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology. 2008;294(6):L1068–L1075. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00025.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guillott L., Medjane S., Le-Barillec K., Balloy V., Danel C., Chignard M., Si-Tahar M. Response of human pulmonary epithelial cells to lipopolysaccharide involves toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)-dependent signaling pathways: evidence for an intracellular compartmentalization of TLR4. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279(4):2712–2718. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305790200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schneberger D., Caldwell S., Kanthan R., Singh B. Expression of Toll-like receptor 9 in mouse and human lungs. Journal of Anatomy. 2013;222(5):495–503. doi: 10.1111/joa.12039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Iram N., Mildner M., Prior M., Petzelbauer P., Fiala C., Hacker S., Schöppl A., Tschachler E., Elbe-Bürger A. Age-related changes in expression and function of toll-like receptors in human skin. Development. 2012;139(22):4210–4219. doi: 10.1242/dev.083477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baker B. S., Ovigne J. M., Powles A. V., Corcoran S., Fry L. Normal keratinocytes express Toll-like receptors (TLRs) 1, 2 and 5: modulation of TLR expression in chronic plaque psoriasis. British Journal of Dermatology. 2003;148(4):670–679. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2003.05287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pivarcsi A., Bodai L., Réthi B., Kenderessy-Szabó A., Koreck A., Széll M., Beer Z., Bata-Csörgo Z., Magócsi M., Rajnavölgyi E., Dobozy A., Kemény L. Expression and function of Toll-like receptors 2 and 4 in human keratinocytes. International Immunology. 2003;15(6):721–730. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxg068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Köllisch G., Kalali B. N., Voelcker V., Wallich R., Behrendt H., Ring J., Bauer S., Jakob T., Mempel M., Ollert M. Various members of the Toll-like receptor family contribute to the innate immune response of human epidermal keratinocytes. Immunology. 2005;114(4):531–541. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2005.02122.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dai X., Sayama K., Yamasaki K., Tohyama M., Shirakata Y., Hanakawa Y., Tokumaru S., Yahata Y., Yang L., Yoshimura A., Hashimoto K. SOCS1-negative feedback of STAT1 activation is a key pathway in the dsRNA-induced innate immune response of human keratinocytes. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2006;126(7):1574–1581. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kalali B. N., Köllisch G., Mages J., Müller T., Bauer S., Wagner H., Ring J., Lang R., Mempel M., Ollert M. Double-stranded RNA induces an antiviral defense status in epidermal keratinocytes through TLR3-, PKR-, and MDA5/RIG-I-mediated differential signaling. The Journal of Immunology. 2008;181(4):2694–2704. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.4.2694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lebre M. C., Van Der Aar A. M. G., Van Baarsen L., Van Capel T. M. M., Schuitemaker J. H. N., Kapsenberg M. L., De Jong E. C. Human keratinocytes express functional toll-like receptor 3, 4, 5, and 9. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2007;127(2):331–341. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miller L. S., Modlin R. L. Human keratinocyte Toll-like receptors promote distinct immune responses. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2007;127(2):262–263. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ting J. P.-Y., Lovering R. C., Alnemri E. S., Bertin J., Boss J. M., Davis B. K., Flavell R. A., Girardin S. E., Godzik A., Harton J. A., Hoffman H. M., Hugot J.-P., Inohara N., MacKenzie A., Maltais L. J., Nunez G., Ogura Y., Otten L. A., Philpott D., Reed J. C., Reith W., Schreiber S., Steimle V., Ward P. A. The NLR gene family: a standard nomenclature. Immunity. 2008;28(3):285–287. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Franchi L., Park J. H., Shaw M. H., Marina-Garcia N., Chen G., Kim Y. G., Núñez G. Intracellular NOD-like receptors in innate immunity, infection and disease. Cellular Microbiology. 2008;10(1):1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.01059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Allen I. C., Scull M. A., Moore C. B., Holl E. K., McElvania-TeKippe E., Taxman D. J., Guthrie E. H., Pickles R. J., Ting J. P.-Y. The NLRP3 inflammasome mediates in vivo innate immunity to influenza A virus through recognition of viral RNA. Immunity. 2009;30(4):556–565. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kvarnhammar A. M., Tengroth L., Adner M., Cardell L.-O. Innate immune receptors in human airway smooth muscle cells: activation by TLR1/2, TLR3, TLR4, TLR7 and NOD1 agonists. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068701.e68701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Inohara N., Chamaillard M., McDonald C., Nuñez G. NOD-LRR proteins: role in host-microbial interactions and inflammatory disease. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 2005;74:355–383. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fritz J. H., Ferrero R. L., Philpott D. J., Girardin S. E. Nod-like proteins in immunity, inflammation and disease. Nature Immunology. 2006;7(12):1250–1257. doi: 10.1038/ni1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Creagh E. M., O'Neill L. A. J. TLRs, NLRs and RLRs: a trinity of pathogen sensors that co-operate in innate immunity. Trends in Immunology. 2006;27(8):352–357. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Uehara A., Fujimoto Y., Fukase K., Takada H. Various human epithelial cells express functional Toll-like receptors, NOD1 and NOD2 to produce anti-microbial peptides, but not proinflammatory cytokines. Molecular Immunology. 2007;44(12):3100–3111. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2007.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Le Bourhis L., Benko S., Girardin S. E. Nod1 and Nod2 in innate immunity and human inflammatory disorders. Biochemical Society Transactions. 2007;35(6):1479–1484. doi: 10.1042/BST0351479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Philpott D. J., Yamaoka S., Israël A., Sansonetti P. J. Invasive Shigella flexneri activates NF-κB through a lipopolysaccharide-dependent innate intracellular response and leads to IL-8 expression in epithelial cells. Journal of Immunology. 2000;165(2):903–914. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.2.903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Girardin S. E., Tournebize R., Mavris M., Page A.-L., Li X., Stark G. R., Bertin J., Distefano P. S., Yaniv M., Sansonetti P. J., Philpott D. J. CARD4/Nod1 mediates NF-κB and JNK activation by invasive Shigella flexneri . EMBO Reports. 2001;2(8):736–742. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kim J. G., Lee S. J., Kagnoff M. F. Nod1 is an essential signal transducer in intestinal epithelial cells infected with bacteria that avoid recognition by Toll-like receptors. Infection and Immunity. 2004;72(3):1487–1495. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.3.1487-1495.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Opitz B., Förster S., Hocke A. C., Maass M., Schmeck B., Hippenstiel S., Suttorp N., Krüll M. Nod1-mediated endothelial cell activation by Chlamydophila pneumoniae . Circulation Research. 2005;96(3):319–326. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000155721.83594.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Welter-Stahl L., Ojcius D. M., Viala J., Girardin S., Liu W., Delarbre C., Philpott D., Kelly K. A., Darville T. Stimulation of the cytosolic receptor for peptidoglycan, Nod1, by infection with Chlamydia trachomatis or Chlamydia muridarum. Cellular Microbiology. 2006;8(6):1047–1057. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kaparakis M., Turnbull L., Carneiro L., Firth S., Coleman H. A., Parkington H. C., Le Bourhis L., Karrar A., Viala J., Mak J., Hutton M. L., Davies J. K., Crack P. J., Hertzog P. J., Philpott D. J., Girardin S. E., Whitchurch C. B., Ferrero R. L. Bacterial membrane vesicles deliver peptidoglycan to NOD1 in epithelial cells. Cellular Microbiology. 2010;12(3):372–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kufer T. A., Banks D. J., Philpott D. J. Innate immune sensing of microbes by Nod proteins. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2006;1072:19–27. doi: 10.1196/annals.1326.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Robertson S. J., Girardin S. E. Nod-like receptors in intestinal host defense: controlling pathogens, the microbiota, or both? Current Opinion in Gastroenterology. 2013;29(1):15–22. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e32835a68ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Girardin S. E., Boneca I. G., Viala J., Chamaillard M., Labigne A., Thomas G., Philpott D. J., Sansonetti P. J. Nod2 is a general sensor of peptidoglycan through muramyl dipeptide (MDP) detection. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278(11):8869–8872. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200651200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Qiu H. N., Wong C. K., Chu I. M. T., Hu S., Lam C. W. K. Muramyl dipeptide mediated activation of human bronchial epithelial cells interacting with basophils: a novel mechanism of airway inflammation. Clinical and Experimental Immunology. 2013;172(1):81–94. doi: 10.1111/cei.12031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Leissinger M., Kulkarni R., Zemans R. L., Downey G. P., Jeyaseelan S. Investigating the role of NOD-like receptors in bacterial lung infection. The American Journal of Respiratory Critical Care Medicine. 2014 doi: 10.1164/rccm.201311-2103PP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Slevogt H., Seybold J., Tiwari K. N., Hocke A. C., Jonatat C., Dietel S., Hippenstiel S., Singer B. B., Bachmann S., Suttorp N., Opitz B. Moraxella catarrhalis is internalized in respiratory epithelial cells by a trigger-like mechanism and initiates a TLR2- and partly NOD1-dependent inflammatory immune response. Cellular Microbiology. 2007;9(3):694–707. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00821.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Opitz B., Püschel A., Beermann W., Hocke A. C., Förster S., Schmeck B., Van Laak V., Chakraborty T., Suttorp N., Hippenstiel S. Listeria monocytogenes activated p38 MAPK and induced IL-8 secretion in a nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain 1-dependent manner in endothelial cells. The Journal of Immunology. 2006;176(1):484–490. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.1.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Barton J. L., Berg T., Didon L., Nord M. The pattern recognition receptor Nod1 activates CCAAT/enhancer binding protein β signalling in lung epithelial cells. European Respiratory Journal. 2007;30(2):214–222. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00143906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Månsson Kvarnhammar A., Tengroth L., Adner M., Cardell L. O. Innate immune receptors in human airway smooth muscle cells: activation by TLR1/2 TLR3, TLR4, TLR7 and NOD agonists. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068701.e68701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shimada K., Chen S., Dempsey P. W., et al. The NOD/RIP2 pathway is essential for host defenses against Chlamydophila pneumoniae lung infection. PLoS Pathogens. 2009;5(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000379.e1000379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Regueiro V., Moranta D., Frank C. G., Larrarte E., Margareto J., March C., Garmendia J., Bengoechea J. A. Klebsiella pneumoniae subverts the activation of inflammatory responses in a NOD1-dependent manner. Cellular Microbiology. 2011;13(1):135–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2010.01526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Berrington W. R., Iyer R., Wells R. D., Smith K. D., Skerrett S. J., Hawn T. R. NOD1 and NOD2 regulation of pulmonary innate immunity to Legionella pneumophila . European Journal of Immunology. 2010;40(12):3519–3527. doi: 10.1002/eji.201040518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Travassos L. H., Carneiro L. A. M., Girardin S. E., Boneca I. G., Lemos R., Bozza M. T., Domingues R. C. P., Coyle A. J., Bertin J., Philpott D. J., Plotkowski M. C. Nod1 participates in the innate immune response to Pseudomonas aeruginosa . The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280(44):36714–36718. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501649200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kim Y.-G., Park J.-H., Daignault S., Fukase K., Núñez G. Cross-tolerization between Nod1 and Nod2 signaling results in reduced refractoriness to bacterial infection in Nod2-deficient macrophages. Journal of Immunology. 2008;181(6):4340–4346. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.6.4340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Opitz B., Püschel A., Schmeck B., Hocke A. C., Rosseau S., Hammerschmidt S., Schumann R. R., Suttorp N., Hippenstiel S. Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain proteins are innate immune receptors for internalized Streptococcus pneumoniae. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279(35):36426–36432. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403861200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Theivanthiran B., Batra S., Balamayooran G., Cai S., Kobayashi K., Flavell R. A., Jeyaseelan S. NOD2 signaling contributes to host defense in the lungs against Escherichia coli infection. Infection and Immunity. 2012;80(7):2558–2569. doi: 10.1128/IAI.06230-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 77.Ferwerda G., Girardin S. E., Kullberg B.-J., Le Bourhis L., De Jong D. J., Langenberg D. M. L., Van Crevel R., Adema G. J., Ottenhoff T. H. M., Van Der Meer J. W. M., Netea M. G. NOD2 and toll-like receptors are nonredundant recognition systems of Mycobacterium tuberculosis . PLoS Pathogens. 2005;1(3, article e34) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0010034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Davis K. M., Nakamura S., Weiser J. N. Nod2 sensing of lysozyme-digested peptidoglycan promotes macrophage recruitment and clearance of S. pneumoniae colonization in mice. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2011;121(9):3666–3676. doi: 10.1172/JCI57761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kapetanovic R., Jouvion G., Fitting C., Parlato M., Blanchet C., Huerre M., Cavaillon J.-M., Adib-Conquy M. Contribution of NOD2 to lung inflammation during Staphylococcus aureus-induced pneumonia. Microbes and Infection. 2010;12(10):759–767. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chaput C., Sander L. E., Suttorp N., Opitz B. NOD-like receptors in lung diseases. Frontiers in Immunology. 2013;4, article 393 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bauernfeind F., Hornung V. Of inflammasomes and pathogens—sensing of microbes by the inflammasome. EMBO Molecular Medicine. 2013;5(6):814–826. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201201771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hirota J. A., Hirota S. A., Warner S. M., et al. The airway epithelium nucleotide-binding domain and leucine-rich repeat protein 3 inflammasome is activated by urban particulate matter. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2012;129(4):1116.e6–1125.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Alnemri E. S. Sensing cytoplasmic danger signals by the inflammasome. Journal of Clinical Immunology. 2010;30(4):512–519. doi: 10.1007/s10875-010-9419-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kim S., Bauernfeind F., Ablasser A., Hartmann G., Fitzgerald K. A., Latz E., Hornung V. Listeria monocytogenes is sensed by the NLRP3 and AIM2 inflammasome. European Journal of Immunology. 2010;40(6):1545–1551. doi: 10.1002/eji.201040425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Meixenberger K., Pache F., Eitel J., Schmeck B., Hippenstiel S., Slevogt H., N'Guessan P., Witzenrath M., Netea M. G., Chakraborty T., Suttorp N., Opitz B. Listeria monocytogenes-infected human peripheral blood mononuclear cells produce IL-1β, depending on listeriolysin O and NLRP3. Journal of Immunology. 2010;184(2):922–930. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Muñoz-Planillo R., Franchi L., Miller L. S., Núñez G. A critical role for hemolysins and bacterial lipoproteins in Staphylococcus aureus-induced activation of the Nlrp3 inflammasome. The Journal of Immunology. 2009;183(6):3942–3948. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Eitel J., Meixenberger K., van Laak C., Orlovski C., Hocke A., Schmeck B., Hippenstiel S., N'Guessan P. D., Suttorp N., Opitz B. Rac1 regulates the NLRP3 inflammasome which mediates IL-1beta production in Chlamydophila pneumoniae infected human mononuclear cells. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030379.e30379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Carlsson F., Kim J., Dumitru C., Barck K. H., Carano R. A. D., Sun M., Diehl L., Brown E. J. Host-detrimental role of Esx-1-mediated inflammasome activation in Mycobacterial infection. PLoS Pathogens. 2010;6(5):1–12. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Case C. L., Kohler L. J., Lima J. B., Strowig T., Zoete M. R. D., Flavell R. A., Zamboni D. S., Roy C. R. Caspase-11 stimulates rapid flagellin-independent pyroptosis in response to Legionella pneumophila . Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110(5):1851–1856. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211521110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Allen I. C., Scull M. A., Moore C. B., Holl E. K., McElvania-TeKippe E., Taxman D. J., Guthrie E. H., Pickles R. J., Ting J. P.-Y. The NLRP3 inflammasome mediates in vivo innate immunity to influenza A virus through recognition of viral RNA. Immunity. 2009;30(4):556–565. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Pothlichet J., Meunier I., Davis B. K., Ting J. P.-Y., Skamene E., von Messling V., Vidal S. M. Type I IFN triggers RIG-I/TLR3/NLRP3-dependent inflammasome activation in influenza A virus infected cells. PLoS Pathogens. 2013;9(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003256.e1003256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Park E., Na H. S., Song Y.-R., Shin S. Y., Kim Y.-M., Chung J. Activation of NLRP3 and AIM2 inflammasomes by Porphyromonas gingivalis infection. Infection and Immunity. 2014;82(1):112–123. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00862-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Saïd-Sadier N., Padilla E., Langsley G., Ojcius D. M. Aspergillus fumigatus stimulates the NLRP3 inflammasome through a pathway requiring ROS production and the syk tyrosine kinase. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010008.e10008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.McCoy A. J., Koizumi Y., Higa N., Suzuki T. Differential regulation of caspase-1 activation via NLRP3/NLRC4 inflammasomes mediated by aerolysin and type III secretion system during Aeromonas veronii infection. The Journal of Immunology. 2010;185(11):7077–7084. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Martinon F., Burns K., Tschopp J. The Inflammasome: A molecular platform triggering activation of inflammatory caspases and processing of proIL-β . Molecular Cell. 2002;10(2):417–426. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00599-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kummer J. A., Broekhuizen R., Everett H., Agostini L., Kuijk L., Martinon F., Van Bruggen R., Tschopp J. Inflammasome components NALP 1 and 3 show distinct but separate expression profiles in human tissues suggesting a site-specific role in the inflammatory response. Journal of Histochemistry and Cytochemistry. 2007;55(5):443–452. doi: 10.1369/jhc.6A7101.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Boyden E. D., Dietrich W. F. Nalp1b controls mouse macrophage susceptibility to anthrax lethal toxin. Nature Genetics. 2006;38(2):240–244. doi: 10.1038/ng1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ewald S. E., Chavarria-Smith J., Boothroyd J. C. NLRP1 is an inflammasome sensor for Toxoplasma gondii . Infection and Immunity. 2014;82(1):460–468. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01170-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Radian A. D., de Almeida L., Dorfleutner A., Stehlik C. NLRP7 and related inflammasome activating pattern recognition receptors and their function in host defense and disease. Microbes and Infection. 2013;15(8-9):630–639. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Khare S., Dorfleutner A., Bryan N. B., Yun C., Radian A. D., de Almeida L., Rojanasakul Y., Stehlik C. An NLRP7-containing inflammasome mediates recognition of microbial lipopeptides in human macrophages. Immunity. 2012;36(3):464–476. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Cui J., Li Y., Zhu L., Liu D., Songyang Z., Wang H. Y., Wang R.-F. NLRP4 negatively regulates type I interferon signaling by targeting the kinase TBK1 for degradation via the ubiquitin ligase DTX4. Nature Immunology. 2012;13(4):387–395. doi: 10.1038/ni.2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Fiorentino L., Stehlik C., Oliveira V., Ariza M. E., Godzik A., Reed J. C. A novel PAAD-containing protein that modulates NF-κB induction by cytokines tumor necrosis factor-α and interleukin-1β . The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277(38):35333–35340. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200446200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Jounai N., Kobiyama K., Shiina M., Ogata K., Ishii K. J., Takeshita F. NLRP4 negatively regulates autophagic processes through an association with Beclin1. The Journal of Immunology. 2011;186(3):1646–1655. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Anand P. K., Malireddi R. K. S., Lukens J. R., Vogel P., Bertin J., Lamkanfi M., Kanneganti T.-D. NLRP6 negatively regulates innate immunity and host defence against bacterial pathogens. Nature. 2012;488(7411):389–393. doi: 10.1038/nature11250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Anand P. K., Kanneganti T.-D. NLRP6 in infection and inflammation. Microbes and Infection. 2013;15(10-11):661–668. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2013.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Arthur J. C., Lich J. D., Ye Z., Allen I. C., Gris D., Wilson J. E., Schneider M., Roney K. E., O'Connor B. P., Moore C. B., Morrison A., Sutterwala F. S., Bertin J., Koller B. H., Liu Z., Ting J. P.-Y. NLRP12 controls dendritic and myeloid cell migration to affect contact hypersensitivity. Journal of Immunology. 2010;185(8):4515–4519. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Lord C. A., Savitsky D., Sitcheran R., Calame K., Wright J. R., Ting J. P.-Y., Williams K. L. Blimp-1/PRDM1 mediates transcriptional suppression of the NLR gene NLRP12/monarch-1 . The Journal of Immunology. 2009;182(5):2948–2958. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0801692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Allen I. C., McElvania-TeKippe E., Wilson J. E., Lich J. D., Arthur J. C., Sullivan J. T., Braunstein M., Ting J. P. Y. Characterization of NLRP12 during the in vivo host immune response to Klebsiella pneumoniae and mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060842.e60842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Miao E. A., Alpuche-Aranda C. M., Dors M., Clark A. E., Bader M. W., Miller S. I., Aderem A. Cytoplasmic flagellin activates caspase-1 and secretion of interleukin 1β via Ipaf. Nature Immunology. 2006;7(6):569–575. doi: 10.1038/ni1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Lamkanfi M., Dixit V. M. Inflammasomes: guardians of cytosolic sanctity. Immunological Reviews. 2009;227(1):95–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00730.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Franchi L., Muñoz-Planillo R., Núñez G. Sensing and reacting to microbes through the inflammasomes. Nature Immunology. 2012;13(4):325–332. doi: 10.1038/ni.2231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Suzuki T., Franchi L., Toma C., Ashida H., Ogawa M., Yoshikawa Y., Mimuro H., Inohara N., Sasakawa C., Nuñez G. Differential regulation of caspase-1 activation, pyroptosis, and autophagy via Ipaf and ASC in Shigella-infected macrophages. PLoS pathogens. 2007;3(8, article e111) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Miao E. A., Mao D. P., Yudkovsky N., Bonneau R., Lorang C. G., Warren S. E., Leaf I. A., Aderem A. Innate immune detection of the type III secretion apparatus through the NLRC4 inflammasome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107(7):3076–3080. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913087107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Miao E. A., Warren S. E. Innate immune detection of bacterial virulence factors via the NLRC4 inflammasome. Journal of Clinical Immunology. 2010;30(4):502–506. doi: 10.1007/s10875-010-9386-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Carvalho F. A., Nalbantoglu I., Aitken J. D., Uchiyama R., Su Y., Doho G. H., Vijay-Kumar M., Gewirtz A. T. Cytosolic flagellin receptor NLRC4 protects mice against mucosal and systemic challenges. Mucosal Immunology. 2012;5(3):288–298. doi: 10.1038/mi.2012.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Schroder K., Tschopp J. The inflammasomes. Cell. 2010;140(6):821–832. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Rathinam V. A. K., Jiang Z., Waggoner S. N., Sharma S., Cole L. E., Waggoner L., Vanaja S. K., Monks B. G., Ganesan S., Latz E., Hornung V., Vogel S. N., Szomolanyi-Tsuda E., Fitzgerald K. A. The AIM2 inflammasome is essential for host defense against cytosolic bacteria and DNA viruses. Nature Immunology. 2010;11(5):395–402. doi: 10.1038/ni.1864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Dotson R. J., Rabadi S. M., Westcott E. L., Bradley S., Catlett S. V., Banik S., Harton J. A., Bakshi C. S., Malik M. Repression of inflammasome by Francisella tularensis during early stages of infection. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2013;288(33):23844–23857. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.490086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Belhocine K., Monack D. M. Francisella infection triggers activation of the AIM2 inflammasome in murine dendritic cells. Cellular Microbiology. 2012;14(1):71–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2011.01700.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Tsuchiya K., Hara H., Kawamura I., Nomura T., Yamamoto T., Daim S., Dewamitta S. R., Shen Y., Fang R., Mitsuyama M. Involvement of absent in melanoma 2 in inflammasome activation in macrophages infected with Listeria monocytogenes . Journal of Immunology. 2010;185(2):1186–1195. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Warren S. E., Armstrong A., Hamilton M. K., Mao D. P., Leaf I. A., Miao E. A., Aderem A. cutting edge: Cytosolic bacterial DNA activates the inflammasome via Aim2. Journal of Immunology. 2010;185(2):118–121. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Wu J., Fernandes-Alnemri T., Alnemri E. S. Involvement of the AIM2, NLRC4, and NLRP3 inflammasomes in caspase-1 activation by Listeria monocytogenes . Journal of Clinical Immunology. 2010;30(5):693–702. doi: 10.1007/s10875-010-9425-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Saiga H., Kitada S., Shimada Y., Kamiyama N., Okuyama M., Makino M., Yamamoto M., Takeda K. Critical role of AIM2 in Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. International Immunology. 2012;24(10):637–644. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxs062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Yang Y., Zhou X., Kouadir M., Shi F., Ding T., Liu C., Liu J., Wang M., Yang L., Yin X., Zhao D. The AIM2 inflammasome is involved in macrophage activation during infectionwith virulent Mycobacterium bovis strain. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2013;208(11):1849–1858. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Fang R., Hara H., Sakai S., Hernandez-Cuellar E., Mitsuyama M., Kawamura I., Tsuchiya K. Type I interferon signaling regulates activation of the absent in melanoma 2 inflammasome during Streptococcus pneumoniae Infection. Infection and Immunity. 2014;82(6):2310–2317. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01572-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]