Abstract

This research note examines response and allocation rates for legal status questions asked in publicly available U.S. surveys to address worries that the legal status of immigrants cannot be reliably measured. Contrary to such notions, we find that immigrants’ response rates to questions about legal status are typically not higher than response rates to other immigration-related questions, such as country of birth and year of immigration. Further exploration of two particular surveys – the Los Angeles Family and Neighborhood Survey (LAFANS) and the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) – reveals that these data sources produce profiles of the unauthorized immigrant population that compare favorably to independently estimated profiles. We also find in the case of the SIPP that the introduction of legal status questions does not appear to have an appreciable “chilling effect” on the subsequent survey participation of unauthorized immigrant respondents. Based on the results, we conclude that future data collection efforts should include questions about legal status in order to (a) improve models of immigrant incorporation and (b) better position assimilation research to inform policy discussions.

INTRODUCTION

The size of the unauthorized population in the United States – estimated at about 11.1 million in 2011 (Passel and Cohn 2012) – coupled with the emergence of an increasingly exclusionary stance vis-à-vis immigrants at federal, state, and local levels – has led researchers to raise important policy-relevant questions about the salience of legal status for the incorporation and well-being of immigrant families (Bean and Stevens 2003; Donato and Armenta 2011; Glick 2010; Massey and Bartley 2005). A small body of ethnographic research suggests that unauthorized status severely diminishes the well-being and life chances of the children of immigrant parents (Abrego 2011; Gleeson and Gonzales 2012; Gonzales 2011; Gonzales and Chavez 2012; Gonzales, Suarez-Orozco, and Dedios-Sanguineti 2013; Hagan, Rodriguez, and Castro 2011; Yoshikawa 2011). This conclusion is consistent with the findings from an even smaller number of survey-based studies. For example, using data from a survey of second-generation adults in Los Angeles, Bean et al (2011) find significantly lower levels of educational attainment among the adult children of unauthorized Mexican immigrant mothers who never obtained legal resident status, as compared to their counterparts whose mothers either arrived as legal permanent residents or were able to at some point adjust to legal status. Using data from two panels of the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP), Hall, Greenman, and Farkas (2010) report that unauthorized Mexican immigrants experience significant adjusted wage gaps, smaller returns to their human capital, and slower wage growth, relative to legally resident Mexican immigrants. On the basis of analyses of four panels of SIPP data showing that unauthorized Mexican and Central American youth are less likely to complete high school and enroll in college, Greenman and Hall (2013) conclude that “legal status is a critical axis of stratification for Latinos”. And in their analysis of data from the Los Angeles Family and Neighborhood Survey (L.A.FANS), Prentice, Pebley and Sastry (2005) find that unauthorized immigrants have a substantially lower likelihood of having health insurance coverage than legal immigrants and U.S. citizens.

Taken together, the small body of literature on unauthorized status and immigrant incorporation suggests that legal status is an important variable shaping patterns of contemporary assimilation. However, because legal status is not measured in surveys most commonly used in social science research on assimilation, it tends to be underemphasized in the large body of incorporation research that has emerged during in the last twenty-five years. This lack of emphasis on legal status, which stems largely from a lack of widely used data (Clark and King 2008), carries at least two crucial implications. First, it puts contemporary social science theory and research aimed at explaining patterns of assimilation at risk of suffering from omitted variable bias (Massey and Bartley 2005), insofar as the myriad structural and/or cultural mechanisms purported to slow the incorporation of some groups, especially Mexicans, are spuriously associated with integration outcomes due to the omission of legal status in assimilation models. Second, the lack of survey data on unauthorized immigrants, including their incorporation experiences, severely limits the extent to which social science research can adequately inform public policy debates (National Research Council 2013).

As discussed in more detail below, the lack of population survey data that includes measures of immigrant legal status appears to derive in part from assumptions by some researchers and policy-makers that information on legal status cannot be reliably obtained, or should not be (Carter-Pokras and Zambrana 2006; U.S. Government Accountability Office 2006). Concerns about the collection of data on legal status tend to revolve around doubts about the accuracy of such data (i.e., whether immigrants would answer such questions or answer them honestly) and the extent to which the introduction of questions about immigrants’ legal status may produce a “chilling effect” whereby respondents refuse to answer subsequent questions or participate in subsequent data collection efforts. In this research note, we examine these concerns empirically by investigating non-response/allocation rates of legal status measures in L.A.FANS and SIPP. We focus on (a) the frequency with which immigrants answer questions about their legal/citizenship status; (b) in the case of SIPP, whether the introduction of questions about the legal status of immigrants is associated with relatively high rates of non-response to subsequent survey items or attrition from the panel altogether; and (c) whether the surveys produce estimates of the characteristics of the unauthorized population that are comparable to independent estimates based on the residual method, the technique most often used to compute aggregate estimates of unauthorized migration Van Hook and Bean 1998). The two surveys are valuable sources of data for researchers interested in adding legal status variables into models of immigrant incorporation and the well-being of immigrants and their children, but few researchers have employed the data for these purposes. Of course, these data sources are useful only to the extent that immigrants’ legal status is accurately measured and that they provide unbiased profiles of the unauthorized population. To the best of our knowledge, these questions have not been addressed in the research literature.

BACKGROUND

Perspectives on Measuring Immigrants’ Legal Status

A common assumption about the measurement of immigrants’ legal status holds that such questions are sensitive in nature, akin to questions about illicit drug-use, for example. This assumption underlies a 2006 report by the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), which takes as a starting point that standard questionnaires with direct questions about legal status are unlikely to yield valid data. As a possible remedy, it considers the implementation of non-standard “grouped answers,” or a “three-card” method, in a national survey that would enable the estimation of the size and characteristics of the unauthorized immigrant population without respondents having to report their specific immigration status (GAO 2006). Viewed as a sensitive survey item, researchers and immigrant advocates have also expressed concern that the introduction of such questions in surveys or administrative data collection could have a “chilling effect” leading unauthorized immigrants to refuse participation in surveys and render this population more difficult to locate and/or serve (Carter-Pokras and Zambrana 2006).

The assumption that questions about immigrants’ legal status are sensitive in nature, however, is not necessarily supported by the empirical evidence that exists to test the premise. For example, the aforementioned GAO report (2006) acknowledged that two government surveys that include relatively direct questions about legal status1 noted that data collection efforts had not experienced problems in the field, even as the research had adopted the assumption that such questions could not be asked directly. Similarly, researchers from the RAND Corporation reported from a pilot survey of immigrants in Los Angeles in the early 1990s: “Surprisingly, all respondents answered what we thought was the single most sensitive question—their current immigration status” (DaVanzo et al. 1994). It is likely that the degree to which immigrants perceive questions about their immigration status as sensitive in nature depends on who is asking the questions. Among recommendations made by researchers and immigrant advocates consulted for the GAO report, a universal opinion expressed was that a national survey of immigrants including questions about legal status should be administered by a university or private research organization rather than a government agency such as the Census Bureau (GAO 2006). This leads us to hypothesize that of the two data sets examined here, the L.A.FANS, which was designed and administered by the RAND Corporation, will yield better response rates to legal status questions than the SIPP, which was administered by the U.S. Census Bureau.

DATA & MEASUREMENT

The Los Angeles Family and Neighborhood Survey (L.A.FANS)

L.A.FANS is longitudinal survey of families in Los Angeles County focusing in large part on the extent to which child development outcomes are related to neighborhood, family and peer dynamics. Our focus is on the first wave of data, collected out between April 2000 and January 2002. The survey was designed by RAND and fieldwork was conducted in English and Spanish by RAND’s Survey Research Group and the Research Triangle Institute via Computer Assisted Personal Interviews (CAPI). In the informed consent process, in addition to assurances that information from the survey would be kept confidential and used for research purposes only, respondents were also given a Certificate of Confidentiality issued by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS), guaranteeing that respondents’ identities could not and would not be revealed, even under court order or subpoena (Pebley and Sastry 2003, Chapter 7).

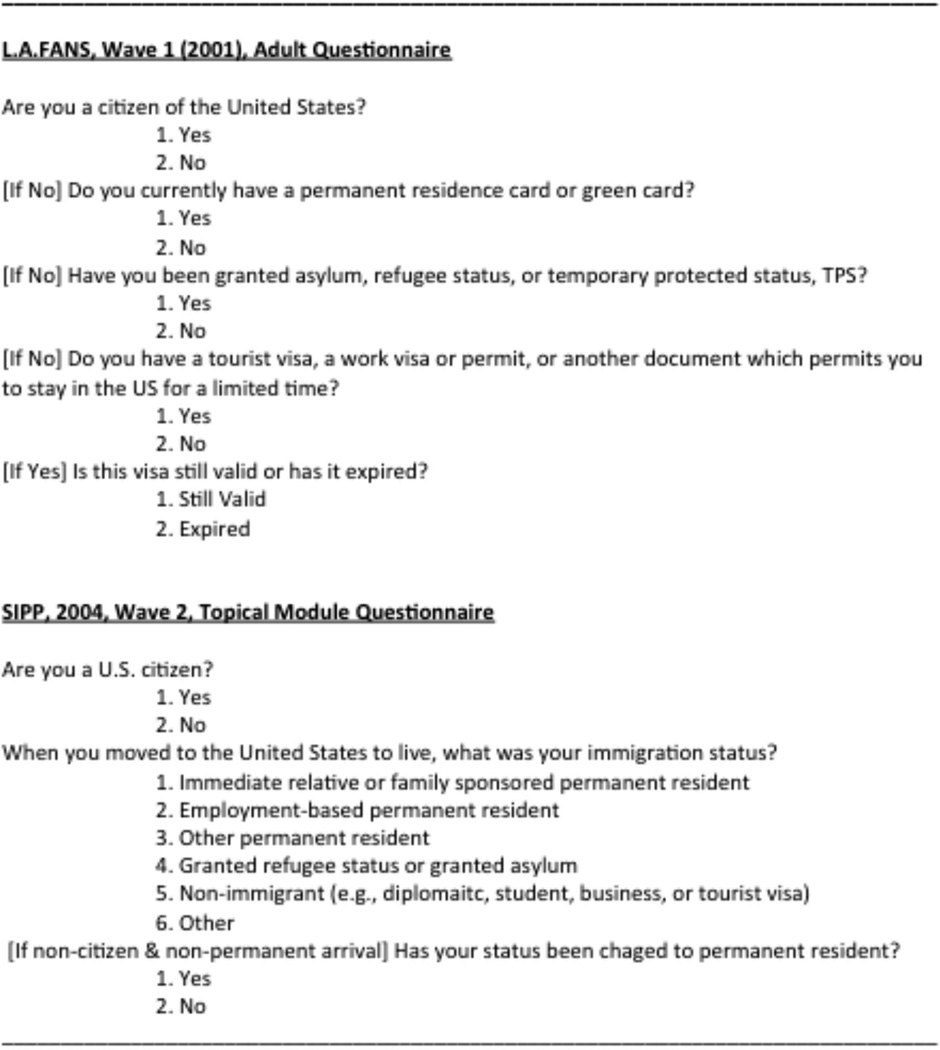

Questions about legal status were asked of all foreign-born adults in the L.A.FANS. The wording and order of the questions is shown in Figure 1. First, all immigrants were asked whether they are naturalized citizens. Non-citizens were then asked whether they had a “green card” or Legal Permanent Resident (LPR) visa. Subsequently, those without green cards were asked whether they had been granted refugee, asylee, or Temporary Protected Status (TPS). Finally, those responding “no” to each of these questions were asked whether they possessed a valid visa granting temporary residence in the United States. Those not indicating one of these four legal statuses – citizens, non-citizen LPRs, refugees/asylees, or legal temporary residents – were assumed to be unauthorized immigrants.

Figure 1.

Wording of Survey Questions used to Determine Immigrants’ Citizenship and Legal Status in L.A.FANS and SIPP

Results presented below pertaining to response rates are based on unweighted analyses, while the comparative profiles of the unauthorized population are based on weighted estimates, using the adult person-weight provided with the data. Sample weights provided by L.A.FANS adjust for the oversampling of households with children as well as for household non-response (see Peterson et al. 2004, page 41).

The Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP)

SIPP is a representative panel survey of households in the United States is designed to collect information about factors associated with income and program participation. It includes a core set of questions asked at every wave of data collection, as well as topical modules that vary from wave to wave. We used the 2004 panel. Questions about immigrants’ legal status were included in the wave two topical module, collected via in-person interviews between June and September, 2004. Foreign-born respondents in SIPP were first asked whether they were citizens (and how they became citizens). Then, all immigrants (i.e., those who are not citizens by birth or adoption) were asked about their status upon arrival. As shown in Figure 1, immigrants could select six arrival statuses: three types of legal permanent residency, refugee/asylee status, non-immigrant status (e.g., student or tourist visas), or “other”. The publicly-available data, however, which we use here, do not allow users to distinguish among different types of non-LPRs, presumably in order to protect respondents’ confidentiality. Thus, in the public-use data, non-LPRs consist of those who arrived as unauthorized immigrants as well as those arriving legally as refugees/asylees or legal temporary migrants. Finally, non-citizen non-LPR arrivals were asked whether their status had changed to legal permanent resident. It is assumed that the overwhelming majority of non-LPR arrivals who have not adjusted to LPR status will be unauthorized immigrants, though as noted, some non-adjustees are likely to be legal non-immigrants and refugee/asylees.

In comparison to L.A.FANS, the public-use SIPP data provide users with a less fine-grained profile of the foreign-born population. The series of L.A.FANS questions enable users to distinguish citizens from LPRs, Refugees, legal non-immigrants, and the unauthorized, respectively. One advantage of the SIPP questions over the L.A.FANS, however, is that the former measure the legal and citizenship trajectories of immigrants, while the latter only measures immigrants’ current status.

The SIPP, but not the L.A.FANS, imputes values for missing responses on legal status questions. Specifically, the Census Bureau allocates missing responses in SIPP using statistical techniques (e.g., hot-deck imputation) that predict missing values based on the valid responses of persons who are similar with respect to a number of characteristics (e.g., age, sex, race, geography, etc.). One concern with the allocation procedure used by the Census Bureau stems from the variables used to predict responses to the legal status questions: it is not clear that they include country of birth or year of arrival (information on predictors has not been published by the Census Bureau). If values are not allocated using these two key variables, which are strongly related to the legal status of immigrants, the allocated values are not likely to be very predictive of actual legal status. In addition, the statistical imputation procedure assumes that the mechanism driving non-response to a given survey item is not related to the item being imputed (Allison 2002; U.S. Census Bureau 2008), which would be violated if data on the legal status questions are largely missing because unauthorized immigrants do not wish to reveal to government employees that they are in the country without authorization. Due to questions about the accuracy of the Census Bureau’s allocation procedure, we employ three different methods for assigning legal status to foreign-born respondents in the SIPP. The first simply accepts the Census Bureau’s allocated values and assume that all non-citizen, non-permanent resident arrivals who have not adjusted to LPR status are unauthorized immigrants.

We also use a second method, which we refer to as the “Multiple Imputation” method. For this approach, we recode all of the legal status variables that were allocated by the Census Bureau as missing and then used multiple imputation (Allison 2002) to re-allocate the values. Missing naturalization, arrival status, and adjustee status information is imputed using several variables that model-building exercises indicated are predictive of these variables.2 As the name implies, missing data are imputed multiple times, and imputed values for a given observation will vary across imputations. We created ten imputed data sets, and thus any results presented below based on the method will have been averaged across the ten imputed data sets.

The third method, which we term a “Logic-based Re-allocation” method, involves two steps. We first set all of the allocated responses to missing. Then all respondents with missing data, along with those who were deemed to fall in the unauthorized category, were placed in a pool of “potentially unauthorized” persons. Thus, the pool of potential unauthorized respondents consists of all persons who cannot be identified as either naturalized or a legal permanent resident based on valid responses to the three questions listed in Figure 1. The second step follows Passel et al. (2006) and Hall et al. (2010) and involves removing respondents from the pool of potential unauthorized persons based on their having characteristics that suggest they have a low probability of being unauthorized. For example, we assume that all foreign-born students enrolled in post-secondary educational institutions are in the country on student visas. We also remove persons in a number of specialty occupations that are not likely to be held by unauthorized immigrants (e.g., diplomats and government employees) as listed in Passel et al (2006). We also remove persons who are veterans or active-duty service men or women, as well as persons having received public assistance. Finally, we use data from the Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) Office of Immigration Statistics (OIS) to remove probable refugees from the pool of potential unauthorized immigrants. We assign each immigrant a probability of being a refugee arrival based on country of birth and year of arrival. This probability is simply the percentage of immigrants admitted from a given country in a given year that was admitted as refugees or asylees, as reported by DHS. For each immigrant, we take a random draw from a uniform distribution and compare it to the individual’s refugee probability. Individuals whose probability exceeds the random draw are coded as refugee arrivals and removed from the pool of potential unauthorized immigrants. All persons remaining in the pool are assumed to be unauthorized immigrants.

As with the L.A.FANS results, SIPP-based analyses of non-response are unweighted. Comparative profiles, however, are based on weighted estimates using the Wave 2 person weight provided by the Census Bureau, which adjusts for household non-response and panel attrition.

FINDINGS

Do Immigrants Answer Questions about Their Legal Status?

Our first research question involves whether evidence of non-response emerges when people are asked about their migration status. As hypothesized, this does not appear to be the case in the L.A.FANS data. Table 1 reports the prevalence of missing data for the series of questions asked of immigrants in the L.A.FANS. Of the 1,949 immigrant respondents who were asked the naturalization question, 69, or 3.7 percent had missing data. The percentage missing increases to 5.7, 10.5 and 12.4 for the green card, refugee and temporary visa questions, respectively. The bulk of this increase is due to the fact that the same 69 respondents with missing data on the citizenship question also had missing data on all of the subsequent questions. Of all of the foreign-born respondents in L.A.FANS, only 4.3 percent (N=84) have an ambiguous immigration status due to non-response to the series of questions that determine status. We assume that these ambiguous cases are unauthorized, but the profile of the unauthorized population does not change when we delete these cases from the sample.

Table 1.

Missing Data on Citizenship and Immigration Status Questions among Adult Immigrants in Los Angeles, 2001

| Yes |

No |

Missing |

% Missing |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naturalized Citizen? | 522 | 1,358 | 69 | 3.7 |

| LPR/Green Card?a | 588 | 762 | 77 | 5.7 |

| Refugee /Asylee?b | 75 | 684 | 80 | 10.5 |

| Temporary Visa?c | 117 | 563 | 84 | 12.4 |

| Temporary Visa Still Valid?d | 94 | 23 | 0 | 0.0 |

Source: LAFANS, Wave 1 (2001), Adult File

Note: Cases in shaded cells are assumed to be unauthorized

Asked of all non-citizens

Asked of non-citizen, non-LPRs

Asked of non-citizen, non-LPRs and non-refugees

Asked of persons with a temporary visa

Also as hypothesized, non-response to the legal status items in SIPP is much higher than in the L.A.FANS (Table 2). Of the 9,178 foreign-born persons asked the question about arrival status, 27.2 percent of the responses were allocated by the Census Bureau. And of the 2,445 respondents asked the question about adjusting to LPR status, 17.8 percent had allocated responses. Both of these percentages exceed the 15 percent threshold beyond which Allison (2002) suggests multiple imputation techniques be used for the handling of missing data. However, it is important to note that legal status in the SIPP is indeterminable only for those non-naturalized (or missing), non-LPR arrivals (or missing) who also have missing data on the status adjustment question. Of the 2,494 immigrants with missing arrival status data, 1,552 (62 percent) reported as naturalized citizens, so it can be inferred that these respondents either arrived as LPRs or arrived illegally and subsequently adjusted to permanent status before naturalizing. And among the 2,973 non-citizen immigrants with unknown or valid non-LPR arrival status, 1,168 did not provide a valid response to the question about adjustment of status. Thus, in total, 1,168 of 9,178 immigrant adults in the SIPP (12.7 percent) had an ambiguous legal status when considering the three questions jointly.

Table 2.

Allocation Rates for Citizenship and Immigration Status Questions among Foreign-Born Respondents Ages 15 and Older, SIPP, Wave 2, 2004

| Naturalized Citizen?a |

LPR Arrival?a |

LPR Adjustee?b |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Unallocated Responses | |||

| Not in Universe | 0 | 0 | 6,733 |

| Yes | 4,100 | 4,149 | 857 |

| No | 5,003 | 2,535 | 1,153 |

| Allocated Responses | |||

| Yes | 20 | 1,528 | 148 |

| No | 55 | 966 | 287 |

| Total N in Universe | 9,178 | 9,178 | 2,445 |

| % Allocated | 0.8 | 27.2 | 17.8 |

Source: Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP), Wave 2 2004 data were collected between February and August, 2004

Asked of all foreign-born respondents

Asked of non-naturalized, non-LPR arrivals

Additional evidence suggests that the relatively high item-allocation rates for the legal status questions in SIPP may derive from issues related to the survey design or field operations rather than from the content of the questions per se. First, the percentage of missing values on the question about year of entry is also very high: 25.3. And among those who answered the question on year of entry, only 8.5 percent failed to answer the questions on legal status at entry. Thus, non-response to the legal status questions is concentrated among a relatively small percentage of immigrants who also did not answer other questions about their migration experience. This point is further illustrated in Tables 3 and 4. In Table 3 we compare the range of non-response / allocation to legal status items in L.A.FANS and SIPP to the range in five other publicly available surveys that have also asked legal status questions (more information about these data sources can be found in the Appendix). Relative to the other six surveys listed in Table 3, SIPP easily has the highest rate of non-response to the legal status indicators, consistent with the notion that something particular to the SIPP data collection is responsible for the high allocation rate, rather than the sensitive nature of the legal status questions.

Table 3.

Range of Non-Response to Survey Questions on Immigrants’ Citizenship and Legal Status in Selected, Publicly Available U.S. Surveys

| Survey | Data Collection Method |

Private or Public Sponsor |

Year(s) |

# Citizenship/Legal Status Questions |

Range of Non- Response (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) |

In-Person | Public | 1996–2008 | 4 | 4.6–25.3 |

| The Los Angeles Family and Neighborhood Survey (LAFANS) |

In-Person | Private | 2001 & 2008 | 6 | 1.4–6.8 |

| National Agricultural Workers Survey (NAWS) |

In-Person | Public | 1988 – 2009 | 1 | 0.5–5.5 |

| Immigration and Intergenerational Mobility in Metropolitan Los Angeles (IIMMLA) |

Telephone | Private | 2004 – 2005 | 7 | 0.3–13.1 |

| The Immigrant Second Generation in Metropolitan New York (ISGMNY) |

Telephone | Private | 1999 – 2000 | 3 | 0.1–1.6 |

| National Asian American Survey (NAAS) | Telephone | Private | 2008 | 2 | 0.2–5.2 |

| Multi-City Study of Urban Inequality (MCSUI) |

In-Person | Private | 1992 –1994 | 3 | 0.1–0.5 |

Table 4.

Missing or Allocated Data (Percentages) for Immigration-Related Questions in Selected U.S. Surveys

| Country of Birth |

Year of Immigration |

Citizenship |

Legal Statusa |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Los Angeles Family and Neighborhood Survey (LAFANS), 2001 |

0.23 | 3.95 | 3.54 | 4.31 |

| Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP), 2004 |

0.08 | 25.35 | 0.84 | 13.62 |

| National Agricultural Workers Survey (NAWS), 2004–2005 |

0.25 | 0.13 | b | 0.41 |

| National Asian American Survey (NAAS), 2008 |

0.31 | 6.61 | b | 6.23 |

| Immigrant Second Generation in Metropolitan New York (ISGMNY), 1999– 2000 |

0.00 | 0.62 | 0.09 | 1.59 |

| Immigrant Integration and Mobility in Metropolitan Los Angeles (IIMMLA), 2004– 2005 |

0.61 | 0.73 | 0.30 | 6.90 |

| Multi-City Study of Urban Inequality (MCSUI), 1992–1994 |

1.47 | 2.16 | 4.84 | 6.99 |

| American Community Survey (ACS), 2005 | 2.69 | 6.15 | 3.35 | d |

| Current Population Survey (CPS), March 2004 |

0.44 | 10.47 | c | d |

| National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), 2004 |

0.20 | 2.59 | 2.59 | d |

Percentage refers to the share of the sample whose legal status cannot be determined

Citizenship included as a category on a single legal status question

Data quality flags for the CPS citizenship question not provided by IPUMS-CPS

Legal status not measured

In Table 4 we present allocation rates for other immigration related questions in the seven surveys with legal status indicators as well as three large government sponsored surveys often used to study the immigrant population that do not measure legal status. Relative to other immigration related variables, especially year of immigration, non-response/allocation for legal status is not appreciably higher in most surveys that measure it. To put these allocation rates into perspective, the average allocation rate of person-level variables in the 2005 American Community Survey was 3.7 percent. Thus, immigration related variables tend to have higher than average rates of missing data, though the results here suggest that legal status variables are not more prone to non-response than other immigration related variables such as year of immigration. Finally, it is also worth noting that other variables commonly used in social science research, such as income, are also allocated at relatively high rates. For example, the Census Bureau reports that 18 percent of the persons asked income questions in the 2005 ACS had their responses allocated.

Do Questions about Legal Status Produce a Chilling Effect?

Our second research question concerns the degree to which asking about immigrants’ legal status will have a “chilling effect” that leads subsequently to high unit non-response, or to refusal to participate in the survey altogether. We examine this question by comparing two outcomes: (1) non-response to the survey item immediately following the SIPP questions on legal status; and (2) attrition from the SIPP panel between Wave 2, when the immigration status questions were asked, and Wave 3. If legal status questions exerted a chilling effect, we would expect to find higher rates of subsequent non-response and panel attrition among the unauthorized compared to legal non-citizens and naturalized citizens. The results are shown in Table 5 using the three status assignment methods described above. Because unauthorized status is positively correlated with other characteristics that have been found to be associated with non-response (Groves, Cialdini and Couper 1992), Table 5 presents, in addition to zero-order comparisons, adjusted probabilities predicted by logit models controlling for age, sex, marital status, education, and home ownership, English-language proficiency and duration of U.S. residence. The logit models are weighted using the SIPP person weights, and thus the predicted probabilities can be interpreted as the percentage of the wave two population not represented in the third wave.

Table 5.

Predicted Probabilities (Percentages) from Logit Models Predicting Non-Response to the Survey Question Immediately Following Legal Status Questions (A) and Panel Attrition between Waves 2 and 3 (B), Foreign-Born Respondents Ages 15 and Older, SIPP, 2004

| Unauthorized |

Legal Non- Citizens |

Naturalized |

Pseudo-R2 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Subsequent Non-Response | ||||

| Hot Deck | ||||

| Unadjusted | 7.2 | 3.5 a | 2.7 a | 0.018 |

| Adjusted1 | 4.2 | 2.5 a | 2.4 b | 0.090 |

| Multiple Imputation | ||||

| Unadjusted | 5.7 | 4.3 c | 2.2 a | 0.017 |

| Adjusted1 | 3.6 | 3.1 | 1.9 b | 0.089 |

| Logical Imputation | ||||

| Unadjusted | 7.2 | 3.2 a | 1.9 a | 0.037 |

| Adjusted1 | 4.9 | 2.5 a | 1.6 a | 0.102 |

| B. Attrition, Wave 2–3 | ||||

| Hot Deck | ||||

| Unadjusted | 15.8 | 12.3 a | 11.6 a | 0.003 |

| Adjusted1 | 13.8 | 11.5 a | 12.3 a | 0.012 |

| Multiple Imputation | ||||

| Unadjusted | 14.1 | 13.2 | 11.1 b | 0.002 |

| Adjusted1 | 12.2 | 12.5 | 11.9 | 0.012 |

| Logical Imputation | ||||

| Unadjusted | 17.8 | 10.9 a | 10.5 a | 0.011 |

| Adjusted1 | 16.5 | 10.8 a | 10.8 a | 0.018 |

Difference from unauthorized immigrants significant at p < .001

Difference from unauthorized immigrants significant at p < .01

Difference from unauthorized immigrants significant at p < .10

Adjusted models include controls for age, sex, educational attainment, employment status, home-ownership, and English language proficiency

We begin by focusing on comparative probabilities of non-response to the question immediately following the SIPP legal status questions, which in this case, is the first in a series of questions about relationships to other household members (Panel A). Overall, non-response to this question is relatively low, though in the unadjusted case, significantly higher among the unauthorized. For example, when legal status is assigned using either the hot deck or logical imputation method, the unauthorized are about twice as likely not to respond to the subsequent survey item as their legal non-citizen counterparts and 33 percent more likely when legal status is made using the multiple imputation method. Though the unauthorized are significantly more likely not to respond to the item following the legal status questions, their overall rate of non-response – 7.2 percent, 7.2 percent and 5.7 percent for the hot deck, logical and multiple imputation methods, respectively – is not so high as to suggest that their non-response derives from the chilling effects of the legal status questions. If this were the case, one would expect substantially higher rates of non-response among the unauthorized, and for legal status alone to be a stronger determinant of non-response than indicated by the very small pseudo-R-squared statistics reported for the unadjusted models in panel A of Table 5. Rather, we see that non-response is determined to a far greater extent with other characteristics also associated with legal status, as evidenced by the fact that predicted probabilities of non-response among the unauthorized are reduced in the unadjusted models, that the gap in non-response between unauthorized and legal immigrants decreases when controls are introduced, and by the fact that the pseudo-R-squared statistic is roughly three times larger in the adjusted versus the unadjusted model.

In Panel B of Table 5, we test a second type of chilling effect, attrition from the SIPP panel between Wave 2 and 3. As would be expected, the overall rate of attrition is higher than the rate of non-response to subsequent survey items. Unauthorized migrants, regardless of the method used to assign legal status, are significantly less likely than legal migrants to be observed in the subsequent wave of the survey, but the difference is not so large to provide evidence that unauthorized immigrants are disproportionately dissuaded from subsequent participation in the survey due to being asked about their legal status. Moreover, the gap in rates of attrition across legal statuses diminishes somewhat with the introduction of the control variables, but the pseudo-R-squared statistics strongly suggest that attrition is driven largely by unobserved variables. While we cannot conclude with certainty the reason behind the relatively higher rates of panel attrition among the unauthorized, it is not surprising to find somewhat higher rates of attrition among the unauthorized given that more recently arrived immigrants live in more complex household arrangements and experience more turnover (Van Hook and Glick 2007), but the magnitude of the difference between the rates of attrition for the unauthorized and other groups does not appear to reflect a chilling effect.

Comparative Profiles of the Unauthorized Foreign-Born Population

One reasonable concern over the use of measures of immigrants’ legal status in surveys is that unauthorized immigrants may see no reason to report their status honestly, especially to representatives collecting data on behalf of the U.S. government. For this concern to be warranted, we would expect profiles of the unauthorized population that are based on self-reported data to deviate from those based on independent estimates based largely on administrative and non-self-reported data. Thus, we turn now to comparisons of the unauthorized population estimated in L.A.FANS and SIPP to independent estimates derived from residual methods.

Residual methods estimate the size and demographic characteristics of the unauthorized population by subtracting a demographic estimate of the legally resident foreign-born population from an estimate based on a population survey (such as the CPS or ACS) or census count of the total foreign-born population. In short, the estimated number of unauthorized immigrants is the difference between the population estimate of legal immigrants and the survey-based estimate of all foreign born. The two most commonly-cited estimates of the characteristics of the unauthorized population are those of the Pew Hispanic Center and the Department of Homeland Security, each of which uses variations of a residual-based method. The DHS estimates are based on the ACS, and use administrative records on legal admissions to remove from the ACS the legalized population by age, sex, state of residence and country of birth. The Pew estimates are based on the Current Population Survey, but use very similar methodology as DHS to produce residual-based estimates of the unauthorized population. The Pew Hispanic Center also produces estimates of detailed characteristics of the unauthorized population based on imputed measures of legal status in the Current Population Survey. This methodology uses an assignment algorithm developed by Passel (Passel and Clark 1998; Passel et al. 2006), which identifies all the foreign-born individuals in the Current Population Survey who have a very low probability of being unauthorized (e.g., persons arriving before 1980, persons from major refugee sending countries, persons reporting as naturalized, veterans, public assistance recipients, persons in specialty occupations, etc.). Among the remaining potentially unauthorized, the method assigns unauthorized status probabilistically based on already-established percentages unauthorized within occupation, state, and sex.

It is important to note that we are not here evaluating the accuracy of one set of estimates versus another. Rather, our goal here is to seek evidence that might give researchers pause in utilizing L.A.FANS and SIPP to study the unauthorized population. We propose that such evidence for concern would be present if the survey-based estimates varied dramatically from the Pew and DHS estimates, especially in instances when the latter two estimates are similar to one another.

Table 6 compares the L.A.FANS-based estimates (thus, weighted using the adult person weights provided in the data) of the unauthorized foreign-born population in Los Angeles to estimates derived using the Passel algorithm (as published in an Urban Institute report by Fortuny, Capps, and Passel [2007]). Comparisons are made with respect to the percentage of the foreign-born population that is estimated to be unauthorized and the following characteristics of the unauthorized population: duration of U.S. residence (ten or fewer years), country of birth, and sex and age composition. It should be noted that all of the L.A.FANS-based estimates are for the adult unauthorized population, whereas the residual-based estimate is for the entire population with the exception of the sex and age distribution estimates, which are limited to the adult unauthorized population.3 About 12% of unauthorized persons are children younger than 18 (Hoefer, Rytina, and Baker 2008). In addition, the L.A.FANS estimates are, of course, for the year 2001, while the residual estimates are based on March CPS data from 2004.

Table 6.

Comparative Profiles of the Adult Unauthorized Foreign-Born Population in Los Angeles County, by Estimation Source

| LAFANS, 2001 |

Resdiual Method |

|

|---|---|---|

| % Unauthorized (of foreign-born) | 26.3 | 26.2 b |

| % in U.S. < 10 Years, Unauthorized | 52.1 | 51.0 c |

| Birthplace, Unauthorized (%) | ||

| Mexico | 64.9 | 57.2 c |

| Other Latin America | 30.1 | 28.0 c |

| Asia | 3.8 | 12.3 c |

| Europe | 1.0 | 2.2 c |

| Other | 0.2 | 0.3 c |

| % Male, Unauthorized | 52.9 | 53.9 d |

| Age Distribution, Unauthorized (%) | ||

| 18–29 | 45.4 | 33.4 e |

| 30–49 | 48.2 | 49.5 e |

| 50–64 | 5.1 | 16.7 e |

| 65+ | 1.3 | 3.0 e |

LAFANS estimates are weighted percentages of adults, ages 18+

Fortuny et al. (2007), Table 7, based on 2000 Census data

Fortuny et al. (2007), Table 8, based on 2004 March CPS data, unauthorized population, all ages

Fortuny et al. (2007), Table 14, based on 2004 March CPS data, adults ages 18–64

Fortuny et al. (2007), Table 9, based on 2004 March CPS data, adults ages 18+

The two estimates are similar with respect to the share of the foreign-born population that is unauthorized and the percentage of recent arrivals among the unauthorized. Both the L.A.FANS and the Fortuny et al. estimates indicate that unauthorized immigrants comprise about 26 percent of the foreign-born population and that among the unauthorized, 51 to 52 percent arrived in the U.S. within the previous ten years. The estimates diverge, however, with respect to the country/region of birth distribution of the unauthorized. In particular, L.A.FANS estimates that 65 percent of the Los Angeles County unauthorized population is Mexican-born compared to 57 percent estimated by Fortuny et al. (2007). And, the L.A.FANS estimate of the unauthorized population that is Asian born (4 percent) is substantially lower than the residual-based estimate (12 percent). We can only speculate about the reason(s) for this discrepancy, but one possibility is that it stems from the fact that the L.A.FANS was administered only in English and Spanish, which could have led to under-coverage among the Asian-born unauthorized population.

Turning finally to comparisons with respect to sex and age distributions of the unauthorized population over age 17, we find that L.A.FANS and the residual estimate are comparable in terms of the percentage of unauthorized adults estimated to be male (53 percent in L.A.FANS and 54 percent in Fortuny et al.), but the L.A.FANS estimates a relatively younger adult unauthorized population than the residual-based estimate. Again, the source of the age discrepancy is unclear. One possibility is that the focus by L.A.FANS on development outcomes among young children may have led to a sample biased toward young adult parents that is not fully accounted for in the person weights.

Table 7 presents comparisons between estimated (weighted using the SIPP person weights for wave 2) characteristics of the unauthorized population from the 2004 SIPP, and estimates published by the Pew Hispanic Center (“Pew”) and DHS, respectively. Table 7 reports three SIPP-based estimates, one for each of the each of the three legal status assignment methods described above. The SIPP estimates are for the adult (age 18+) population; unless otherwise noted, the Pew and DHS estimates are for the entire unauthorized population. In addition, as noted in Table 7, while most of the Pew and DHS estimates are based on 2005 CPS/ACS data, estimates for some characteristics were published more recently, and thus are based on subsequent years of data.

Table 7.

Comparative Profiles of the Adult Unauthorized Foreign-Born Population in the United States, by Estimation Method/Source

| SIPP, 2004 |

Residual Estimates | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hot-Deck Allocation |

Multiple Imputation |

Logical Allocation |

Pew |

DHS |

|

| Legal Status of Foreign-Born (%) | |||||

| Naturalized | 45,5 | 39.7 | 38.9 | 32.0 a | n/a |

| Legal Non-Citizen | 36.5 | 41.2 | 35.3 | 39.0 a | n/a |

| Unauthorized | 18.1 | 19.1 | 25.7 | 29.0 a | n/a |

| Unauthorized, Years in the U.S. (%) | |||||

| 0–5 | 40.7 | 44.0 | 39.2 | 30.0 a | 29.0 c |

| 6–10 | 32.2 | 30.5 | 25.5 | 35.0 a | 30.0 c |

| 11–15 | 10.7 | 13.3 | 13.5 | 21.0 a | 20.0 c |

| 15+ | 16.4 | 12.1 | 21.8 | 14.0 a | 21.0 c |

| Unauthorized, Country of Birth (%) | |||||

| Mexico | 51.6 | 56.4 | 54.8 | 57.0 a | 57.0 c |

| Other Latin America | 20.3 | 19.5 | 20.1 | 24.0 a | n/a |

| Asia | 17.7 | 12.1 | 12.6 | 9.0 a | 11.4 c |

| Europe & Canada | 6.1 | 5.9 | 6.5 | 6.0 a | n/a |

| Africa & Other | 4.3 | 6.0 | 6.1 | 4.0 a | n/a |

| Unauthorized, State of Residence (%) | |||||

| California | 27.5 | 27.4 | 27.3 | 24.0 a | 26.0 c |

| Texas | 10.8 | 11.3 | 10.3 | 14.0 a | 13.0 c |

| Florida | 7.7 | 8.0 | 10.1 | 9.0 a | 8.0 c |

| New York | 6.0 | 7.4 | 10.2 | 7.0 a | 5.0 c |

| Illinois | 2.6 | 3.0 | 3.3 | 4.0 a | 5.0 c |

| Unauthorized, Male (%) | 53.6 | 53.8 | 54.7 | 56.0 a | 56.6 d |

| Unauthorized, Age Distribution (%) | |||||

| 18–24 | 20.4 | 21.3 | 20.1 | 18.3 b | 18.4 d |

| 25–34 | 40.7 | 41.6 | 35.2 | 33.2 b | 41.5 d |

| 35–44 | 19.7 | 20.8 | 19.7 | 27.5 b | 27.7 d |

| 45–54 | 11.2 | 10.9 | 11.2 | 14.2 b | 8.7 d |

| 55+ | 7.9 | 5.4 | 7.9 | 6.7 b | 3.5 d |

Note: SIPP estimates are for the unauthorized population aged 15 and older; Pew and DHS estimates are for the total unauthorized population (all ages); SIPP estimates are weighted

Passel (2005), based on 2004 Current Population Survey data

Authors’ calculations based on Figure 7, Passel and Cohn (2009), based on 2008 March Current Population Survey data

Hoefer, Rytina and Campbell (2006), residual estimates using the 2005 American Community Survey

Hoefer, Rytina and Campbell (2008), residual estaimtes using the 2007 American Community Survey

With respect to the share of the foreign-born population that is unauthorized, all three SIPP estimates are lower compared to the Pew estimate, but the extent to which this is true varies across the three methods. When legal status is assigned using the Census Bureau’s hot deck allocation method, just 18 percent of the foreign-born population is estimated to be unauthorized in the SIPP, compared to 29 percent estimated by Pew. Conversely, when legal status is assigned in the SIPP by the hot deck method, nearly 46 percent of the immigrant population is estimated to consist of naturalized citizens, nearly 18 percentage points higher than the Pew estimate of 32 percent. The multiple imputation and logical allocation methods (and especially the latter) yield estimated legal status distributions that more closely align with the Pew estimate, relative to the hot deck allocation. For example, based on the logical allocation of unknown legal statuses in the SIPP, about 26 percent of the foreign-born population is estimated to be unauthorized compared to 29 percent by Pew; 35 percent of the SIPP foreign-born population is estimated to be legal non-citizens, versus 39 percent by Pew; and 39 percent are estimated to be naturalized citizens compared to 32 percent in the Pew estimate.

Thus, regardless of the method used in the SIPP, the foreign-born population is estimated to have a disproportionately larger share of naturalized citizens than is true for the Pew estimate. We suspect that this may have to do with the tendency of some immigrants, especially those from Mexico, to misreport as naturalized citizens in Census surveys (Van Hook and Bachmeier 2013). In the residual-based Pew estimates, adjustments are made in an attempt to account for this tendency (Passel, Van Hook and Bean 2006), whereas, the only such adjustment we make in the SIPP data is to recode persons reporting as naturalized citizens that have not been in the U.S. at least five years (unless they have a U.S. citizen spouse), as non-citizens. This methodological difference in the handling of naturalization reports, thus, may in part explain differences in the estimated legal status distribution of the foreign-born population.

Variation also exists with respect to the duration of residence of the estimated unauthorized population across the three assignment methods used in the SIPP.4 Using the hot deck and multiple imputation methods, 73 percent and 75 percent, respectively, of the unauthorized foreign-born population is estimated to have lived in the U.S. ten years or less. Using the logical allocation method, the estimated percentage of 64.7 closely aligns with the Pew estimate, 65 percent, both of which are higher than the DHS estimate of 59 percent.

Turning to country / region of birth of the unauthorized population, Mexicans predominate in all of the estimates presented in Table 7, though some variation does exist across the SIPP estimates. Mexicans are relatively less numerous when legal status is assigned using the hot deck allocation method (51.6 percent Mexican), compared to the multiple imputation method (56.4 percent) and the logical allocation method (54.8 percent), both of which are more in line with the identical Pew and DHS estimates of 57 percent. Conversely, the hot deck estimate of the share of the unauthorized population consisting of persons born in Asia (17.7 percent) is significantly higher than the other four estimates. And with respect to the state of residence of the unauthorized foreign-born population, there is general agreement across the set of five estimates reported in Table 7, which are listed for the five states with the largest concentrations of unauthorized residents.

There are modest differences between the three SIPP estimates and the Pew and DHS estimates with respect to the gender composition of the unauthorized population, with the estimated SIPP unauthorized population being slightly less male. Greater variation exists across the five estimates with respect to the age distribution of the unauthorized population. Sixty-one, 63, and 65 percent of the adult unauthorized population in the hot deck, multiple imputation and logical allocation SIPP estimates, respectively, is between the ages of 18 and 34. These estimates are substantially higher than the Pew estimate of 51.6 percent, but relatively comparable to the DHS estimate, 60 percent.

In summary, SIPP-based estimates of the characteristics of the unauthorized population compare favorably to estimates derived from other data sources and using other methods. In instances where SIPP-based estimated characteristics of the unauthorized population diverge from residual-based estimates, there also tends to be little agreement between the two residual-based estimates (e.g., duration of U.S. residence and the age distribution of the unauthorized population). Most importantly, we find little in Table 7 to suggest that misreporting of legal status is so widespread in the SIPP to lead to substantially biased estimates of the unauthorized immigrant population. This conclusion varies somewhat depending on the method used to handle missing data for the legal status measures, as the multiple imputation and logical allocation methods tend to produce profiles of the unauthorized population that are more in line with those published by the Pew Hispanic Center and Department of Homeland Security.

CONCLUSION

Over the past two decades, the foreign-born population in the United States has grown increasingly heterogeneous with respect to legal status (Bean et al. 2013) all within a policy context in which legal status is a particularly salient characteristic that structures the opportunities available to immigrants and their children (Donato and Armenta 2011; Bean et al. 2011; Kasinitz 2012). Due to the sheer size of the unauthorized population and the number of U.S.-born children whose development and incorporation outcomes are likely to be affected by the legal status of their parents, there is a growing need for empirical research examining this association. Unfortunately, the nationally representative data sources that are most often used to study the incorporation of immigrant populations, such as the American Community Survey (ACS) and the Current Population Survey (CPS), do not include questions about immigrants’ legal status. In this research note, we have examined data from two large-scale surveys (one that is national in scope) that do include measures of legal status, and thus serve as valuable sources of data for researchers to begin to examine the consequences of unauthorized status for key incorporation outcomes.

Not only have the L.A.FANS and SIPP been underutilized in research on immigrant group incorporation, the quality of the data on the legal status measures, which make these surveys distinctive, has not been assessed, leaving unaddressed the issue of whether immigrants would even answer questions about their legal status. Here we address this issue and find that non-response to questions about legal status are largely not a concern in the L.A.FANS. However, in the SIPP, there is reason for concern due to that survey’s relatively high allocation rates. The difference in the rate of missing data between the two surveys appears to be consistent with opinions expressed by a panel of immigration researchers and immigrant advocates consulted for the 2006 GAO report, which held that one way to ensure the highest possible response rates to survey questions related to immigrants’ legal status would be to have surveys administered by a private research firm or a university, rather than by a government agency or department (GAO 2006), as is the case with the SIPP. It is also possible that the increased privacy protections implemented in the L.A.FANS helped to keep rates of item non-response relatively low. However, more research is necessary to assess whether the higher nonresponse in the SIPP is due to these factors, or whether it results from other problems with the SIPP’s immigration module. The SIPP stood out among several other governmental surveys as having the highest nonresponse on immigration items, including questions unrelated to the sensitive topic of legal status. Additionally, despite the relatively high allocation rates in the SIPP, we find little or no evidence suggesting that the introduction of questions about immigrants’ legal status during Wave 2 of the survey leads to disproportionately high rates of subsequent item non-response or attrition in Wave 3 among those with the greatest likelihood of being unauthorized.

Moreover, profiles of the unauthorized estimated from L.A.FANS and especially the SIPP compare favorably to independent estimates based on the residual method, suggesting that the two survey samples yield reasonably similar snapshots of the unauthorized populations in Los Angeles and the United States, respectively. Taken together, the findings presented here thus suggest that the assumption that questions about immigrant legal status are too sensitive to be asked seems unwarranted. The collection of such data is feasible and should be considered in future survey efforts. The results reported here also confirm that L.A.FANS and SIPP are valuable, though underutilized sources of data that can be employed to study variation in multiple dimensions of immigrant incorporation across legal and citizenship statuses. A wide range of outcomes can be analyzed using these surveys including educational attainment and transitions, health and well being of both adults and children, employment, marriage and fertility, to name just a few.

It is worthwhile to note that the data analyzed here were collected between 2001 and 2004, prior to the widespread emergence of immigrant enforcement measures at federal, state and local levels. It is therefore possible that the conclusions drawn here about the collection and use of survey data on legal status may not apply in the more recent enforcement context. The extent to which such contexts yield a chilling effect on immigrant respondents in all surveys, not just those that may include questions on legal status, merits future research attention. With that being said, supplementary analyses (available upon request) of the 2008 SIPP panel do not suggest that increases in immigration enforcement have had appreciable impacts on response rates to the legal status questions.

Also, we stress that this research note is concerned with assessing the feasibility of collecting unbiased data on immigrants’ legal status. As with any effort to collect data of a sensitive nature, researchers designing surveys to collect legal status information need to take extraordinary precaution to protect respondents’ confidentiality. These issues have already been given careful consideration by the L.A.FANS research team at RAND (Prentice, Pebley and Sastry 2006), whose work has established a precedent for ensuring the collection of legal status information while simultaneously minimizing risks of disclosing the identities of immigrant respondents.

Finally, it is important to note that the conclusions drawn here about the measurement of immigrants’ legal status may well vary across U.S. states. Just as state- and local-level policy contexts can shape immigrants’ incorporation outcomes, they may also influence response rates to questions about nativity and/or legal status, thus perhaps affecting state-level estimates of the unauthorized foreign-born population such as those recently published by Warren and Warren (2013). Future research should examine the extent to which direct measures of immigrants’ legal status may be more effective in states with less restrictive policies vis-à-vis immigrants. Internationally, it follows that the measurement of legal status may be more successful in nations with policies that are relatively more likely to promote and facilitate the incorporation of immigrant populations. Recent comparative research suggests that the children of immigrants in major immigrant destinations with relatively more inclusive policy regimes experience more favorable integration outcomes (Bean et al. 2012). The implication from this research is that efforts to measure the legal status of immigrants may be met with more success in nations with relatively more inclusionary immigrant incorporation policy regimes.

Acknowledgments

This research is supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (P01 HD062498, RC2 HD064497, and infrastructure support to the Population Research Institute, 2R24HD041025).

APPENDIX

In this appendix we briefly describe the data sources that are not the focus of this paper, but are listed in Tables 3 and 4.

Surveys That Include Legal Status Measures

Immigration and Intergenerational Mobility in Metropolitan Los Angeles (IIMMLA)

IIMMLA is a phone survey of the adult children of immigrants, aged 20–40, living in the Los Angeles metropolitan area. The survey was carried out in 2004 and 2005, and was funded by the Russell Sage Foundation and coordinated by research at the University of California, Irvine and UCLA. More information about the survey is available at www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/ICPSR/studies/22627.

Immigrant Second Generation in Metropolitan New York (ISGMNY)

ISGMNY is a phone survey of the adult children of immigrants, aged 18–32, living in the greater New York metropolitan area. The survey was carried out in November and December 1999, and was funded by the Russell Sage Foundation, the Ford Foundation, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and the Rockefeller Foundation. More information can be obtained at www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/ICPSR/studies/30302.

Multi-City Study of Urban Inequality (MCSUI)

MCSUI is an in-person survey of adults and employers. Data were collected in four metropolitan areas: Atlanta (April 1992-September 1992), Boston (May 1993-November 1994), Detroit (April-September 1992), and Los Angeles (September 1993-August 1994). The study was funded by the Russell Sage Foundation and the Ford Foundation. More information is available at www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/ICPSR/studies/2535.

National Agricultural Workers Survey (NAWS)

NAWS is nationally representative face-to-face survey of the U.S. agricultural workforce, conducted annually since 1988 by the U.S. Department of Labor. More information is available at www.doleta.gov/agworker/naws.cfm.

National Asian American Survey (NAAS)

NAAS is a phone survey of Asian-American residents in the United States. The data were collected between August and October 2008 with funding from the James Irvine Foundation, Rutgers University, the Carnegie Corporation, and the Russell Sage Foundation. More information is available at www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/ICPSR/studies/31481 and at www.naasurvey.com.

Surveys That Do Not Include Legal Status Measures

American Community Survey (ACS)

The ACS is an annual survey that samples approximately one percent of the entire U.S. population, and has been conducted since 2001 by the U.S. Census Bureau. More information about the ACS is available at www.census.gov/acs/www/.

Current Population Survey (CPS)

The CPS is a monthly survey of about 60,000 American households jointly sponsored by the U.S. Census Bureau and the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Data are collected through a combination of in-person and telephone interviews. More information is available at www.census.gov/cps/.

National Health Interview Survey (NHIS)

The NHIS is an annual health survey of the U.S. civilian non-institutionalized population. The survey is sponsored by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and is administered via in-person interviews by the U.S. Census Bureau. More information about the NHIS is available at www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/about_nhis.htm.

Footnotes

The two surveys discussed in the GAO report are the SIPP and the National Agricultural Workers Survey (NAWS).

The imputation model includes the following variables: citizenship, arrival status, adjustee status, years of U.S. residence, earliest known U.S. migration, country of birth, English language proficiency, age, age-squared, sex, family size, family structure, number of minor children in the family, number of social security recipients in the family, poverty level, home ownership, and health insurance coverage status. The imputations are performed using the Imputation with Chained Equations (ice) user-written package for Stata 10.2 (Royston and White 2011) Further information about the imputation model is available upon request.

Given that the survey-based estimates are for the adult unauthorized population while most of the residual-based characteristics are for the entire unauthorized population, this age difference in the populations being compared may account for some observed differences in the profile, though it is not possible for us to estimate how much. It seems likely that the influence of the dissimilarity would be strongest when the characteristic in questions is variable across ages.

We remind readers that it is important to bear in mind that 25 percent of the foreign-born sample in the 2004 SIPP panel had missing year of arrival information and that duration of residence has thus been imputed by the authors (the Census Bureau did not impute this variable) using the multiple imputation model described in the data and methodological section.

REFERENCES

- Abrego Leisy J. Legal Consciousness of Undocumented Latinos: Fear and Stigma as Barriers to Claims-Making for First- and 1.5-Generation Immigrants. Law & Society Review. 2011;45(2):337–370. [Google Scholar]

- Allison Paul D. Missing Data. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bean Frank D, Bachmeier James D, Brown Susan K, Van Hook Jennifer, Leach Mark A. Unauthorized Mexican Migration and the Socioeconomic Integration of Mexican Americans. In: Logan J, editor. Changing Times: America in a New Century. New York: Russell Sage; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bean Frank. D, Brown Susan K, Bachmeier James D, Fokkema Tineke, Lessard-Phillips Laurence. The Dimensions and Degree of Second-generation Incorporation in US and European Cities: A Comparative Study of Inclusion and Exclusion. International Journal of Comparative Sociology. 2012;53(3):181–209. [Google Scholar]

- Bean Frank D, Stevens Gillian. America’s Newcomers and the Dynamics of Diversity. New York: Russell Sage; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bean Frank D, Leach Mark A, Brown Susan K, Bachmeier James D. The Educational Legacy of Unauthorized Migration: Comparisons across U.S. Immigrant Groups in How Parents’ Status Affects Their Offspring. International Migration Review. 2011;45(2):348–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-7379.2011.00851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter-Pokras Olivia, Zambrana Ruth Enid. Collection of Legal Status Information: Caution! American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96(3):399. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.078253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark Rebecca L, King Rosalind B. Social and Economic Aspects of Immigration. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2008;1136(1):289–297. doi: 10.1196/annals.1425.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DaVanzo, Julie, Hawes-Dawson Jennifer, Burciaga Valdez R, Vernez George. Surveying Immigrant Communities: Policy Imperatives and Technical Challenges. Santa Monica, CA: RAND; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Donato Katharine M, Armenta Amada. What We Know about Unauthorized Migration. Annual Review of Sociology. 2011;37:529–543. [Google Scholar]

- Fortuny Karina, Capps Randy, Passel Jeffrey S. The Characteristics of Unauthorized Immigrants in California, Los Angeles County, and the United States. Washington, DC: Urban Institute; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gleeson Shannon, Gonzales Roberto G. When Do Papers Matter? An Institutional Analysis of Undocumented Life in the United States. International Migration. 2012;50(4):1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Glick Jennifer E. Connecting Complex Processes: A Decade of Research on Immigrant Families. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2010;72(3):498–515. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales Roberto G. Learning to Be Illegal: Undocumented Youth and Shifting Legal Contexts in the Transition to Adulthood. American Sociological Review. 2011;76(4):602–619. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales Roberto G, Chavez Leo R. Awakening to a Nightmare. Current Anthropology. 2012;53(3):255–281. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales Roberto G, Suarez-Orozco Carola, Dedios-Sanguineti Maria Cecilia. No Place to Belong: Contextualizing Concepts of Mental Health among Undocumented Immigrant Youth in the United States. American Behavioral Scientist. 2013 (forthcoming) [Google Scholar]

- Greenman Emily, Hall Matthew. Legal Status and Educational Transitions for Mexican and Central American Immigrant Youth. Social Forces. 2013;91(4):1475–1498. doi: 10.1093/sf/sot040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groves Robert M, Cialdini Robert B, Couper Mick P. Understanding the Decision to Participate in a Survey. The Public Opinion Quarterly. 1992;56(4):475–495. [Google Scholar]

- Hagan Jacqueline Maria, Rodriguez Nestor, Castro Brianna. Social Effects of Mass Deportations by the United States Government, 2000-10. Ethnic and Racial Studies. 2011;34(8):1374–1391. [Google Scholar]

- Hall Matthew, Greenman Emily, Farkas George. Legal Status and Wage Disparities for Mexican Immigrants. Social Forces. 2011;89(2):491–514. doi: 10.1353/sof.2010.0082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoefer Michael, Rytina Nancy, Baker Bryan C. Estimates of the Unauthorized Immigrant Population Residing in the United States: January 2007. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Homeland Security; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hoefer Michael, Rytina Nancy, Campbell Christopher. Estimates of the Unauthorized Immigrant Population Residing in the United States: January 2005. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Homeland Security; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Judson Dean H, Swanson David A. Estimating Characteristics of the Foreign-Born by Legal Status: An Evaluation of Data and Methods. SpringerBriefs in Population Studies, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Kasinitz Philip. The Sociology of International Migration: Where We Have Been; Where Do We Go from Here? Sociological Forum. 2012;27(3):579–590. [Google Scholar]

- Lofstrom Magnus, Bohn Sarah, Raphael Steven. Lessons from the 2007 Legal Arizona Workers Act. San Francisco, CA: Public Policy Institute of California; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas S, Bartley Katherine. The Changing Legal Status of Immigrants: A Caution. International Migration Review. 2005;39(2):469–484. [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council; Committee on National Statistics, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Options for Estimating Illegal Entries at the U.S.-Mexico Border. In: Camquiry A, Majmundar M, editors. Panel on Survey Options for Estimating the Flow of Unauthorized Crossings at the U.S.-Mexican Border. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Passel Jeffrey S. The Size and Characteristics of the Unauthorized Migrant Population in the U.S.: Estimates Based on the March 2005 Current Population Survey. Washington, DC: Pew Hispanic Center; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Passel Jeffrey S, Clark Rebecca L. Immigrants in New York: Their Legal Status, Incomes, and Taxes. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Passel Jeffrey S, Cohn D’Vera. A Portrait of Unauthorized Immigrants in the United States. Washington, DC: Pew Hispanic Center; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Passel Jeffrey S, Cohn D’Vera. Unauthorized Immigrant Population: National and State Trends, 2010. Washington, DC: Pew Hispanic Center; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Passel Jeffrey S, Cohn D’Vera. Unauthorized Immigrants: 11.1 Million in 2011. Washington, DC: Pew Hispanic Center; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Passel Jeffrey S, Van Hook Jennifer, Bean Frank D. Estimates by Migrant Status: Narrative Profile with Adjoining Tables of Unauthorized Migrants and Other Immigrants, Based on Census 2000: Characteristics and Methods. Washington, DC: Sabre Systems; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson Christine E, Sastry Narayan, Pebley Anne R, Ghosh-Dastidar Bonnie, Williamson Stephanie, Lara-Cinisomo Sandraluz. The Los Angeles Family and Neighborhood Survey: Codebook. Santa Monica, CA: RAND; 2004. [available on-line at www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/drafts/2005/DRU2400.2-1.pdf] [Google Scholar]

- Pebley Anne R, Sastry Narayan. The Los Angeles Family and Neighborhood Survey: Field Interviewer Manual. Santa Monica, CA: RAND; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Prentice Julia C, Pebley Anne R, Sastry Narayan. Immigration Status and Health Coverage: Who Wins? Who Loses? American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95(1):109–116. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.028514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prentice Julia C, Pebley Anne R, Sastry Narayan. Prentice et al. Respond. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96(3):399–400. [Google Scholar]

- Royston Patrick, White Ian R. Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations (MICE): Implementation in Stata. Journal of Statistical Software. 2011;45(4):1–20. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Survey of Income and Program Participation Users’ Guide. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Government Accountability Office. Estimating the Undocumented Population: A Grouped Answers Approach to Surveying Foreign-Born Respondents. Washington, DC: U.S. GAO; 2006. GAO-06-775. [Google Scholar]

- Van Hook Jennifer, Bean Frank D. Migration Between Mexico and the United States, Research Reports and Background Materials. Mexico City and Washington, D.C: Mexican Ministry of Foreign Affairs and U.S; 1998. Estimating Unauthorized Migration to the United States: Issues and Results; pp. 511–550. Commission on Immigration Reform. [Google Scholar]

- Van Hook Jennifer, Glick Jennifer E. Immigration and Living Arrangements: Moving Beyond Economic Need Versus Acculturation. Demography. 2007;44(2):225–249. doi: 10.1353/dem.2007.0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Hook Jennifer, Bachmeier James D. How Well Does the American Community Survey Count Naturalized Citizens? Demographic Research. 2013 doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2013.29.1. (forthcoming).d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren Robert, Warren John Robert. Unauthorized Immigration to the United States: Annual Estimates and Components of Change, by State, 1990 to 2010. International Migration Review. doi: 10.1111/imre.12022. (Forthcoming) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa Hirokazu. Immigrants Raising Citizens: Undocumented Parents and Their Young Children. New York: Russell Sage; 2011. [Google Scholar]