Abstract

Two hundred ninety-six Asian barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) accessions were assessed to detect QTLs underlying salt tolerance by association analysis using a 384 single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) marker system. The experiment was laid out at the seedling stage in a hydroponic solution under control and 250 mM NaCl solution with three replications of four plants each. Salt tolerance was assessed by leaf injury score (LIS) and salt tolerance indices (STIs) of the number of leaves (NL), shoot length (SL), root length (RL), shoot dry weight (SDW) and root dry weight (RDW). LIS was scored from 1 to 5 according to the severity of necrosis and chlorosis observed on leaves. There was a wide variation in salt tolerance among Asian barley accessions. LIS and STI (SDW) were the most suitable traits for screening salt tolerance. Association was estimated between markers and traits to detect QTLs for LIS and STI (SDW). Seven significant QTLs were located on chromosomes 1H (2 QTLs), 2H (2 QTLs), 3H (1 QTL), 4H (1 QTL) and 5H (1 QTL). Five QTLs were associated with LIS and 2 QTLs with STI (SDW). Two QTLs associated with LIS were newly identified on chromosomes 3H and 4H.

Keywords: Hordeum vulgare L., salt tolerance, leaf injury score, salt tolerance index, SNP markers, quantitative trait loci, association mapping

Introduction

Salt inhibits plant growth via two stresses. There is a rapid, osmotic stress that reduces the plant’s ability to take up water and inhibits the growth of young leaves (Vysotskaya et al. 2010). Shoot and extent root growth are permanently reduced within hours of salt stress and this effect does not appear to depend on sodium concentration but rather is a response to the osmolarity of the external solution (Munns 2002). There is also a slower, ionic stress or salt specific stress that is superimposed on the osmotic effects (Munns et al. 2002) and that may enter the transpiration stream and eventually injure cells in the transpiring leaves (Bohnert and Bressan 2001, Guimaraes 2009, Munns 2005, Munns and Tester 2008). Ionic stress is associated with a reduction of chlorophyll content and inhibits photosynthesis, inducing necrosis of older leaves, leaf senescence and finally premature death of leaves. Leaf senescence begins to appear only after several weeks of salt treatment and shows substantial genotypic variation. In susceptible genotypes, the necrosis starts at the tips and margins of leaves and progresses inward to affect other parts of leaves and stems. Generally, leaves are more vulnerable than roots to sodium accumulation simply because Na+ and Cl− accumulate to higher concentrations in shoots than in roots and cause an ionic imbalance, deficiency symptoms, and disturbance of metabolites (Tester and Davenport 2003). The regulatory mechanisms of Na+ transported at both tissue and cellular levels respond with either Na+ exclusion from tissues and cells or an efficient transportation of Na+ into vacuoles (Munns 2005, Munns and Tester 2008, Rajendran et al. 2009, Tester and Davenport 2003).

Among cereals, rice (Oryza sativa L.) is the most sensitive and barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) is the most tolerant (Munns and Tester 2008), which is considered as an ideal model plant for genetic and physiological studies on salt tolerance due to its short growth period, early maturing and diploid and self-pollinating characteristics (Bothmer et al. 1995). Barley is widely cultivated in saline areas as one of the most salt-tolerant field crops. The genetic diversification and adaptability to a broad range of ecological conditions might have raised a rich gene pool with a large variation in the plant’s adaptations to salt. Many methods have been used to screen the barley germplasm for salt tolerance. Screening under field conditions is limited by the variation due to changeable soil and climate conditions (Xue et al. 2009). The germination and seedling stages are widely used to access the salt tolerance of barley genotypes due to the benefits of their reduced environmental effects (Chen et al. 2005, Ellis et al. 2002, Mano and Takeda 1997, Shavrukov et al. 2010, Taghipour and Salehi 2008). Additionally, a hydroponic system is free from the difficulties associated with soil-related stress factors.

A large number of barley mapping populations have been developed to map genes and QTLs to control agronomic and quality traits (Forster et al. 2004, Prakash and Verma 2006, Witzel et al. 2010), including salt tolerance-related traits (Ben-Hamida et al. 2009, Mano and Takeda 1997, Nguyen et al. 2013a, 2013b, Xue et al. 2012). Mano and Takeda (1997) identified QTLs controlling salt tolerance at the germination and seedling stages in barley by interval mapping using two doubled haploid (DH) populations derived from the crosses of Steptoe × Morex and Harrington × TR306. They concluded that salt tolerance at the germination and seedling stages was controlled by different QTLs. Forster (2001) reviewed the positive effects of semi-dwarfing genes on salt tolerance, and the wild types and mutants showed significant differences in their responses to salt stress in the study. Advanced mapping populations, including near-isogenic lines (NILs) (Marcel et al. 2007), chromosome segment substitution lines (CSSLs) and recombinant chromosome substitution lines (RCSLs) (Sato and Takeda 2009) were also developed to facilitate the genetic dissection of salt tolerance.

Bi-parental mapping is the first step for clarifying the genetic basis of quantitative traits in plants. However, its QTL detection is limited only within two haplotypes. In addition, a long time is needed for mapping population development (Cerda and Cloutier 2012). Association mapping (AM) does not require mapping populations and it can employ a larger number of haplotypes having natural variation on the target quantitative trait (Kraakman et al. 2006, Li et al. 2011, Platten et al. 2013, Visioni et al. 2013). AM is based on genotype-phenotype correlations among individuals in a gene pool (Cerda and Cloutier 2012, Oraguzie et al. 2007). It detects linkage disequilibrium (LD) between markers and traits which have been preserved during the historical recombination accumulated after the domestication of barley (Comadran et al. 2009, Li et al. 2007). Thus, AM requires high-density markers which have enough resolution to detect LD on the genome (Cerda and Cloutier 2012, Forster et al. 2000, Pasam et al. 2012, Varshney et al. 2007, Yu et al. 2012). Few studies have been published on the detection of QTLs for salt tolerance in barley based on AM. Recently, Nguyen et al. (2013a) detected QTLs for salt tolerance in a spring barley collection under 200 mM of NaCl at the vegetative stage by AM with single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) markers.

In the present study, barley accessions belonging to the Asian core collection were evaluated under 250 mM NaCl. The objectives were 1) to evaluate the genetic variation of Asian barley for salt tolerance, 2) to determine suitable traits for screening barley accessions for salt tolerance, 3) to assess the LD decay and population structure of Asian barley accessions, and 4) to identify SNP markers associated with salt tolerance at the seedling stage.

Materials and Methods

Plant materials

A total of 296 barley accessions were used in the present study, originating from the following distant Asian countries: Bhutan, China, India, Japan, Korea, and Nepal. The set of accessions comprised improved cultivars and landraces. They were also classified by row type (two-row or six-row), caryopsis type (covered or naked), and growth habit (spring, winter, or facultative) (Table 1). A full set of the barley core collection was initially investigated by Liu et al. (1999) to reveal the genetic diversity based on the allelic variations at six isozyme loci.

Table 1.

Number of accessions used in the present study and their characteristics

| Origin | Category | Rowed type | Caryopsis | Growth habit | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| Improved | Landrace | Two | Six | Covered | Naked | Spring | Winter | Facultative | ||

| Bhutan | 0 | 11 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 11 | 7 | 3 | 1 | 11 |

| China | 20 | 75 | 9 | 86 | 65 | 30 | 52 | 34 | 9 | 95 |

| India | 4 | 16 | 0 | 20 | 20 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 9 | 20 |

| Japan | 20 | 41 | 12 | 49 | 40 | 21 | 30 | 22 | 9 | 61 |

| Korea | 18 | 48 | 2 | 64 | 45 | 21 | 21 | 38 | 7 | 66 |

| Nepal | 0 | 43 | 0 | 43 | 29 | 14 | 18 | 1 | 24 | 43 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Total | 62 | 234 | 23 | 273 | 199 | 97 | 139 | 98 | 59 | 296 |

Salt tolerance evaluation

To establish a method of salt tolerance assessment at the seedling stage, five accessions (Asan Jungbori, Rogbori, Cheongweon Native, Gho 4, and Lumley 2) were randomly chosen and screened for tolerance in hydroponic culture at the seedling stage. Plants were grown in a growth chamber with a controlled temperature of 24/18°C (day/night) and natural light. Four plants per accession were arranged in a completely randomised block design, with three replications for each treatment (0, 150, 200, and 250 mM NaCl). It was concluded that 250 mM NaCl could be applied to plants at the 2nd leaf stage to evaluate salt tolerance for more than 16 days of treatment (data not shown).

The salt tolerance for 296 Asian accessions at the seedling stage was evaluated by 0 and 250 mM NaCl treatments at the same temperature and light conditions. Seeds were sterilised in 6% sodium hypochlorite for 10 minutes, rinsed with distilled water, and germinated in a Petri dish for 5 days in an incubator at 22/20°C (day/night). Uniform seedlings were selected and transplanted into a container (dimensions: L 90 cm × W 60 cm × D 25 cm), which was painted black to avoid light sensing of roots. The container was filled with 80L hydroponic solution composed of nutrient solution (Otsuka House Nos. 1 and 2, Otsuka Chemical Co., Osaka, Japan) at the following proportions (%): TN (21%), P2O5 (8%), K2O (27%), MgO (4.0%), MnO (0.1%), B2O3 (0.1%), CaO (23%), Fe (0.18%), Cu (0.002%), Zn (0.006%), and Mo (0.002%) (Hossain and Nonami 2012, Shinohara et al. 2011). Each container involved 64 plants spaced by L 2.5 cm × W 2 cm. Each treatment had 12 replicates per accession. The salt treatment was started when two leaves had completely developed. To reduce the effect of osmotic stress, the initial salt concentration was set at 150 mM and then increased to reach the final concentration of NaCl after 3 days. The treatment was maintained for 17 days. The hydroponic solution was changed every week. The pH of the solution was adjusted to 6.5 according to Qiu et al. (2011).

Twenty-six days after transplantation, the number of leaves (NL), root length (RL), and shoot length (SL) were recorded. Plants were separated into roots and shoots, dried in an oven at 85°C for 72 hours, and weighed to determine the shoot dry weight (SDW), root dry weight (RDW), and whole plant dry weight (PDW). The salt tolerance indices (STIs) were calculated for NL, SL, RL, SDW, RDW, and PDW according to the formula below:

Leaf injury score (LIS) was assessed from 1 to 5 [1: no apparent chlorosis; 2: slight (25% of the leaves showed chlorosis); 3: moderate (50% of the leaves showed chlorosis and some necrosis); 4: severe chlorosis (75% of the leaves showed chlorosis and severe necrosis); and 5: dead (leaves showed severe necrosis and were withered)] as shown in Supplemental Fig. 1 (Gregorio et al. 1997, Lee et al. 2008, Mano and Takeda 1997). No symptoms of necrosis or chlorosis were identified under control condition.

Phenotypic data analysis

The variance of each trait under control condition and NaCl treatment was analyzed using GLM model three-way analysis using SAS software version 9.0 (SAS Institute Inc. 2011). Frequency distribution analysis for LIS and STI was performed using JMP software version 11 (SAS Institute Inc. 2011). Spearman’s rho coefficient correlation (r) was determined for all traits with a two-tailed test of significance. Averages of accessions in the countries for salt tolerance trait were compared by Duncan’s multiple range test with a level of significance of 0.05 using software SPSS (SPSS Inc. 2010).

PCR amplification and genotyping

DNA samples were extracted from the leaf samples using an automated DNA isolation system (PI 2000 Kurabo Industries Limited, Japan). The DNA concentration for each sample was adjusted to 50 ng/ul. A reference genetic map was developed by Illumina oligonucleotide pool assays (OPA) using several mapping populations (Close et al. 2009). From a total of 1,536 SNP detection platform of barley OPA 1 (Close et al. 2009), 384 SNPs were selected to avoid redundant or vicinal genetic positions of the reference map. The average spacing between markers was 2.81 cM. PCR, hybridization, and scanning were performed according to the Golden Gate genotyping assay protocol of Illumina Inc. (Fan et al. 2006) with a HiScan microarray scanner (Illumina Inc.) at the Institute of Plant Science and Resources, Okayama University, Kurashiki, Japan. SNP base calling was performed using Genome Studio (Illumina Inc.) with imported cluster positions from previously developed cluster files.

Linkage disequilibrium

Linkage was analyzed using TASSEL 3.0.163 (Bradbury et al. 2007). LD was calculated pairwise between two polymorphic sites, and the most frequently used LD parameters were the standardized disequilibrium coefficient (D′) and the squared allele frequency correlations (r2) (Flint-Garcia et al. 2003). The r2 between loci were considered to be significant when P < 0.001; the other r2 values were not considered as informative. P values were estimated for all pairs of SNP markers within the same chromosome. The extent and distribution of LD were visualized by plotting r2 values against the genetic distance (cM) between markers for full genome and on each chromosome. A critical value of r2 as evidence of linkage was derived from the distribution of the unlinked r2. Unlinked r2 estimates were square root transformed to approximate a normally distributed random variable, and then the parametric 95th percentile of that distribution was taken as a population-specific critical value of r2. The intersection of the LOESS curve fit to syntenic r2 with this baseline was considered as the estimate of the extent of LD on the chromosome (Breseghello and Sorrells 2006).

Population structure

Population structure was estimated using three different methodologies. First, the Q matrix was calculated using STRUCTURE 2.3.4 software (Pritchard et al. 2000). The number of groups/subpopulations (k) was set from 1 to 10 and 10 iterations were performed. An admixture model with a burn-in period of 100,000 and 10,000 Markov Chain Monte Carlo repetitions with correlated allele frequencies among populations were used. The number of subpopulations (k) into accessions was first estimated by calculating the posterior probability ln (P (D)) and L′ (k) for all possible k values between 1 and 10. The true (k) value was calculated using an ad hoc quantity (Δk) described by Evanno et al. (2005). When Δk had the highest value, the value of k was the number of clusters. Second, a neighbor-joining (NJ) tree of 296 Asian barley accessions was constructed from SNP markers by TASSEL. Third, the eigenanalyses proposed by Nguyen et al. (2013a) and Patterson et al. (2006) were also used to investigate the population structure. Eigenanalysis was run with TASSEL using the SNP marker set. A set of significant eigenvectors were obtained and used as covariables to account for population structure.

Association mapping

A set of 318 from 384 SNP markers, with minor allele frequency (MAF) higher than 0.05, were used to perform AM. Marker-trait associations were calculated using the following six models to evaluate the effects of population structure (Q, PC) and kinship (K): (1) naïve without controlling for Q or K, (2) Q model taking into account Q, (3) PCA model controlling for PC, (4) K model taking into account K, (5) QK model taking into account both Q and K, and (6) PK model taking into account both PC and K (Upadhyaya et al. 2013). The naïve, Q, and PCA models were assessed using the generalized linear model (GLM). The K, QK, and PK models were assessed using the mixed linear model (MLM) in TASSEL (Bradbury et al. 2007). A K matrix was generated in TASSEL with all the SNP markers. The P values obtained from all models were converted into −log10 (P). P value significance thresholds for declaring the presence of positive marker-trait associations were calculated based on the false discovery rate (FDR) (Benjamini and Hochberg 1995). The significance thresholds for FDR at a level of 0.05 as −log10 (P) were set to 2.44.

Results

Phenotypic variation among Asian barley accessions

Phenotypic variation in growth-related traits under both NaCl treatment and control condition is presented in Table 2. Barley accessions used in the present study showed a wide variation under control condition for NL and SDW, which varied from 3 to 15 and from 0.28 to 2.8 g/plant, respectively. In addition, among 296 accessions, reductions in NL, SL, RL, SDW, RDW, and PDW by NaCl treatment vs. control condition were observed. The total average reductions for these traits were approximately 65, 67, 71, 50, 65, and 54%, respectively. NaCl treatment extended the coefficient of variance (CV) of the traits, excepting for RL, among accessions and also extended the CV of the traits within accessions (Table 2). For example, the CV of SDW among accessions was 40.95% under control condition, whereas it increased to 48.68% under NaCl treatment. The CVs of SDW within accessions were 5–70% and 6–50% under NaCl treatment and control condition, respectively. The lowest CV within accessions was observed in LIS and ranged from 0 to 20% for all accessions.

Table 2.

Summary of statistics describing the association mapping panel for the phenotypic variation for various growth traits determined after 17 days of testing with 250 mM of NaCl treatment or 0 mM NaCl (Control)

| Trait | Treatment | Min | Max | Mean | SD | CV among acc. (%) | CV within acc. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LIS | NaCl | 1 | 5 | 2.61 | 0.65 | 25.63 | 0–20 |

| SL (cm) | NaCl | 11.50 | 46.40 | 25.96 | 4.76 | 18.33 | 3–29 |

| SL (cm) | Control | 20.60 | 55.00 | 38.25 | 5.73 | 14.99 | 2–21 |

| RL (cm) | NaCl | 6.40 | 43.80 | 17.06 | 4.09 | 23.97 | 6–44 |

| RL (cm) | Control | 8.30 | 51.60 | 23.74 | 6.81 | 28.69 | 5–31 |

| NL | NaCl | 2 | 11 | 4.21 | 1.36 | 32.33 | 0–49 |

| NL | Control | 3 | 15 | 6.42 | 1.69 | 26.39 | 0–36 |

| SDW (g/plant) | NaCl | 0.28 | 2.80 | 1.06 | 0.52 | 48.68 | 5–70 |

| SDW (g/plant) | Control | 0.58 | 5.01 | 2.12 | 0.87 | 40.95 | 6–50 |

| RDW (g/plant) | NaCl | 0.12 | 1.02 | 0.48 | 0.21 | 44.45 | 9–74 |

| RDW (g/plant) | Control | 0.25 | 1.52 | 0.73 | 0.26 | 36.01 | 6–64 |

| PDW (g/plant) | NaCl | 0.42 | 3.84 | 1.54 | 0.69 | 45.04 | 8–74 |

| PDW (g/plant) | Control | 0.83 | 6.33 | 2.85 | 1.08 | 38.01 | 6–42 |

LIS: leaf injury score; SL: shoot length; RL: root length; NL: number of leaves; SDW: shoot dry weight; RDW: root dry weight; PDW: plant dry weight; Min: minimum value; Max: maximum value; Mean: average of 12 values; SD: standard deviation; CV: coefficient of variance within and among accessions (acc.) represented in (%).

ANOVA was performed for both treatments and for the ratio values (Table 3). Under both conditions, significant variations among accessions, replications, and interactions were observed for the traits NL, SL, RL, RDW, and PDW, with the exception of SDW and LIS. The variation between replications can be explained by the fact that replications were made during three different periods or that the experiments were carried out under controlled condition, excluding light condition (light intensity and day length under natural condition). The ANOVA for STI (SDW) showed a significant variation among accessions. A non-significant variation for LIS was shown among the replications and interactions. The environmental variation, the hydroponic system, and even the replications used for this experiment did not affect the scoring of LIS under NaCl treatment.

Table 3.

Analysis of variance summaries (Mean Square) of data for the seedling stage of barley for treatment effect, genotypes, and replications of each treatment effect

| VS | df | NL | SL | RL | SDW | RDW | PDW | LIS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Treatment | 1 | 7777.2** | 381426.4** | 70953.8** | 32.47** | 26.59** | 1074.9** | – |

| Accession | 295 | 28.0** | 254076.3** | 108457** | 26.6** | 102.6 NS | 17.6 NS | – | |

| Replication | 2 | 395.5** | 605.8 NS | 1674** | 3.52** | 10.42** | 222.8** | – | |

|

| |||||||||

| Control | Accession | 295 | 1436.2** | 274.1** | 409.1** | 12.00 NS | 32.7** | 12.1** | – |

| Replication | 2 | 6114.8** | 7920.7** | 858.1** | 69.3* | 364.7** | 112.8** | – | |

| Interaction | 590 | 1022.6** | 49.0** | 46.5** | 11.87 NS | 28.8** | 10.70** | – | |

|

| |||||||||

| NaCl | Accession | 295 | 1452.7** | 156.4** | 92.9** | 64.9** | 15.4** | 3.7** | 32.4** |

| Replication | 2 | 11559** | 206.0** | 1921** | 64.2 NS | 93.7** | 46.0** | 22.7 NS | |

| Interaction | 590 | 1225.0** | 44.2** | 27.6** | 59.4** | 13.9** | 5.2** | 23.8 NS | |

|

| |||||||||

| STI | Accession | 295 | 1540.8** | 610.1** | 3098.8** | 4381.2** | 4648.6** | 4077.7** | – |

| Replication | 2 | 191539** | 19653.6** | 62492** | 156745** | 164101** | 157120** | – | |

VS: variance source; df: degree of freedom; NL: number of leaves; SL: shoot length; RL: root length; SDW: shoot dry weight; RDW: root dry weight; PDW: plant dry weight; LIS: leaf injury score.

significant at the 0.05 and 0.01 levels and non-significant at the 0.05 level.

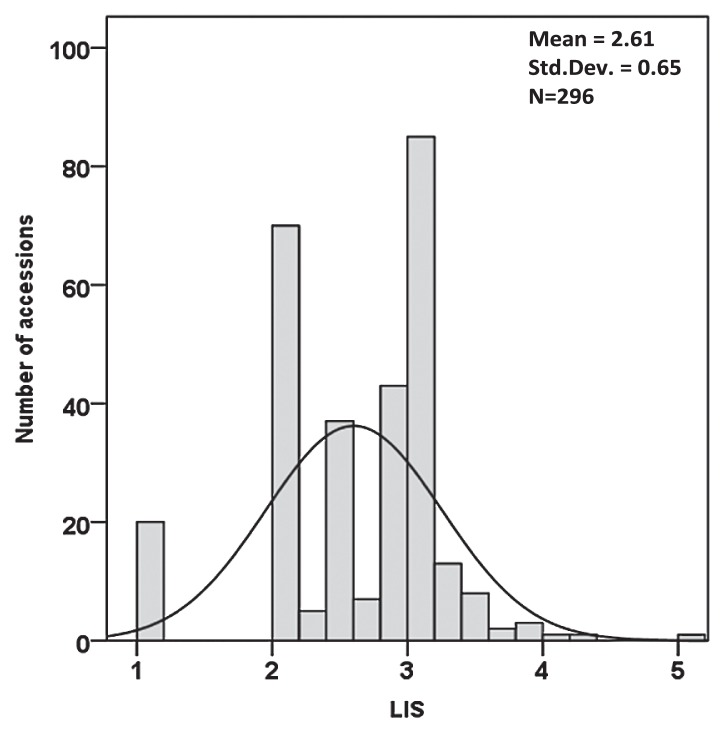

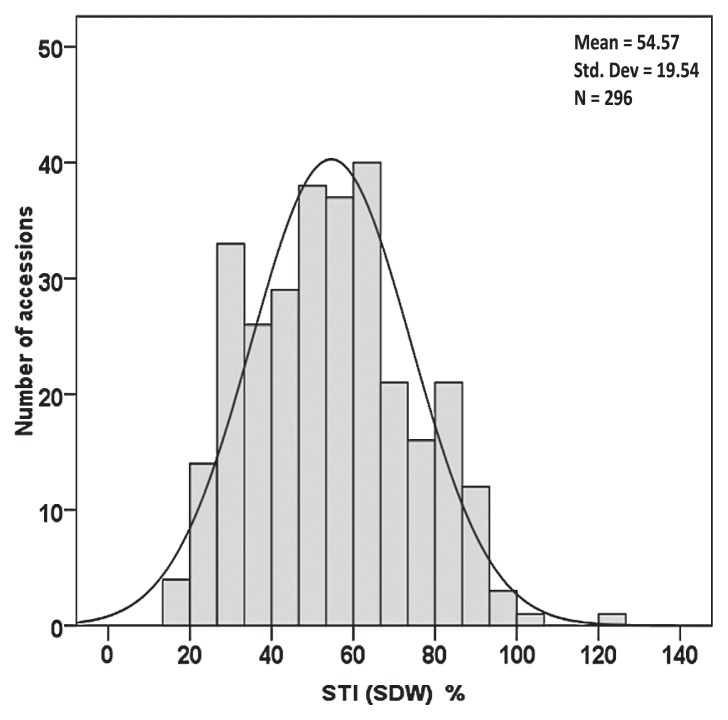

Assessment of salt tolerance

Salt tolerance was assessed by both LIS and STI (SDW) as shown in Fig. 1 and 2. The average LIS was 2.61 with a standard deviation of 0.65 (Fig. 1). Twenty tolerant accessions presented no necrosis. Among them, eleven accessions originated from Japan. Two hundred forty-three accessions were categorised as slight to moderate tolerance to NaCl based on LIS. Thirty-three accessions showed severe necrosis. A large variation in the response to salt stress was demonstrated by the frequency distribution of STI (SDW), ranging from 14 to 126%, with an average of 54.57% and a standard deviation of 19.54% (Fig. 2, Table 4). The CV of 35.80% of STI (SDW) was the highest compared with other related traits, indicating a great difference in salt tolerance among Asian landraces and improved cultivars.

Fig. 1.

The frequency distribution for LIS on 296 Asian barley accessions at the seedling stage. Values are the means of 3 replications (average of 4 plants/replication and 3 replications by accession). LIS ranged from 1 to 5 according to the severity of necrosis and chlorosis in the leaves (1: no apparent chlorosis; 2: slight; 3: moderate; 4: severe chlorosis; and 5: dead).

Fig. 2.

The frequency distribution of STI (SDW) among 296 Asian barley accessions at the seedling stage. Values are the means of 3 replications (average of 12 replicates by accession). A normal distribution was plotted.

Table 4.

Summary of statistics describing salt tolerance index for related traits

| Trait | Min | Max | Mean | SD | CV among acc. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STI (SL) | 50.36 | 91.99 | 68.12 | 7.61 | 11.17 |

| STI (RL) | 43.27 | 134.76 | 74.81 | 16.42 | 21.94 |

| STI (NL) | 36.84 | 92.19 | 66.87 | 11.13 | 16.65 |

| STI (SDW) | 14.30 | 125.89 | 54.57 | 19.54 | 35.80 |

| STI (RDW) | 22.07 | 121.75 | 68.81 | 20.45 | 29.72 |

| STI (PDW) | 16.46 | 124.55 | 58.06 | 19.35 | 33.32 |

STI: salt tolerance index; SL: shoot length; RL: root length; NL: number of leaves; SDW: shoot dry weight; RDW: root dry weight; PDW: plant dry weight; Min: minimum value; Max: maximum value; Mean: average of 3 replication values; SD: standard deviation; CV: coefficient of variance among accessions (%).

Bold type represents the highest coefficient of variation among accessions for salt tolerance indices.

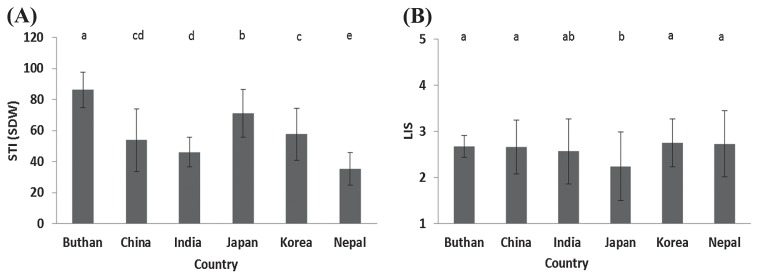

The relationship between salt tolerance and the origin of accessions is shown in Fig. 3. On average, the accessions originating from Japan and Bhutan showed higher tolerance to NaCl compared with accessions from other countries. In particular, accessions from Nepal showed a significant reduction in biomass by NaCl compared with other countries (Fig. 3A). According to the relationship between LIS and origin of accessions (Fig. 3B), the accessions originating from Japan showed the lowest LIS compared with others, followed by Indian accessions, indicating that Japanese accessions are more salt tolerant than accessions originating from other countries. The Japanese two-row types showed significantly higher tolerance to NaCl compared with six-row types. Higher level of tolerance in Japanese two-row types may contribute to a higher level of salt tolerance in Japanese accessions compared with other countries (data not shown). On the other hand, T test for the equality of means showed a non-significant variation between winter (mean = 55.24%) and spring (mean = 57.92%) growth habits, while STI (SDW) with a mean value of 45.53% in facultative type showed a significant difference at 1% and 0.1% from winter and spring growth habits, respectively

Fig. 3.

Relationship between salt tolerance [3A: STI (SDW)], [3B: LIS], and the origin of accessions. Means with the same letter are not significantly different.

Correlation between salt tolerance and other traits

STI (SDW) was found to be significantly correlated with biomass production (SDW, RDW and PDW) under both NaCl treatment and control condition (Table 5). It was also significantly correlated with RL, SL, and NL. STI (SDW) was also significantly correlated with STI (SL), STI (RDW), and STI (PDW). LIS was correlated with NL and STI (NL) with correlation coefficients of 0.13 and 0.16, respectively. LIS was not correlated with total biomass production under every condition or STI. No correlation was found between LIS and STI (SDW), suggesting that the genes underlying LIS and STI (SDW) might not be the same.

Table 5.

Coefficient of correlation (r) of plant traits with leaf injury score and salt tolerance index under 250 mM of NaCl treatment or 0 mM NaCl (Control).

| Trait | Treatment | LIS | STI (SDW) | SDW | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Control | NaCl | ||||

| LIS | NaCl | 1 | NS | NS | NS |

| SL (cm) | Control | NS | −0.33** | 0.65** | 0.35** |

| SL (cm) | NaCl | NS | −0.15** | 0.42** | 0.30** |

| RL (cm) | Control | NS | −0.16** | 0.39** | 0.30** |

| RL (cm) | NaCl | NS | NS | 0.26** | 0.35** |

| NL | Control | NS | NS | 0.52** | 0.42** |

| NL | NaCl | −0.13* | 0.30** | 0.24** | 0.62** |

| SDW (g/plant) | Control | NS | −0.62** | 1 | 0.43** |

| SDW (g/plant) | NaCl | NS | 0.39** | 0.43** | 1 |

| RDW (g/plant) | Control | NS | −0.52** | 0.88** | 0.36** |

| RDW (g/plant) | NaCl | NS | 0.37** | 0.37** | 0.86** |

| PDW (g/plant) | Control | NS | −0.61** | 0.99** | 0.43** |

| PDW (g/plant) | NaCl | NS | 0.40** | 0.42** | 0.99** |

| STI (SL) | – | NS | 0.41** | −0.13* | NS |

| STI (RL) | – | NS | 0.12* | −0.22** | NS |

| STI (NL) | – | 0.16** | 0.21** | −0.31** | 0.16** |

| STI (SDW) | – | NS | 1 | −0.62** | 0.38** |

| STI (RDW) | – | NS | 0.84** | −0.45** | 0.43** |

| STI (PDW) | – | NS | 0.98** | −0.59** | 0.40** |

SL: shoot length; RL: root length; NL: number of leaves; SDW: shoot dry weight; RDW: root dry weight; PDW: plant dry weight; STI: salt tolerance index.

significant at the 0.05 and 0.01 levels and non-significant at the 0.05 level.

Population structure among Asian barley accessions

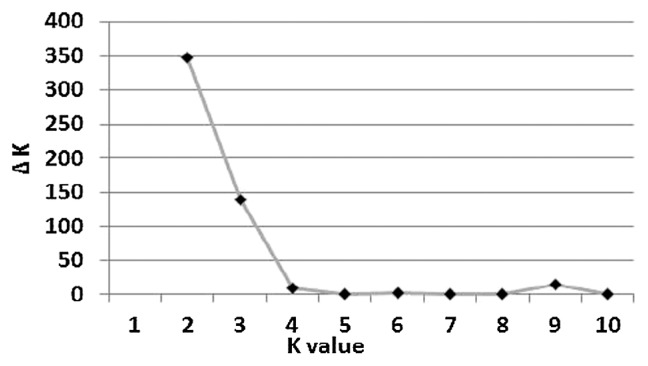

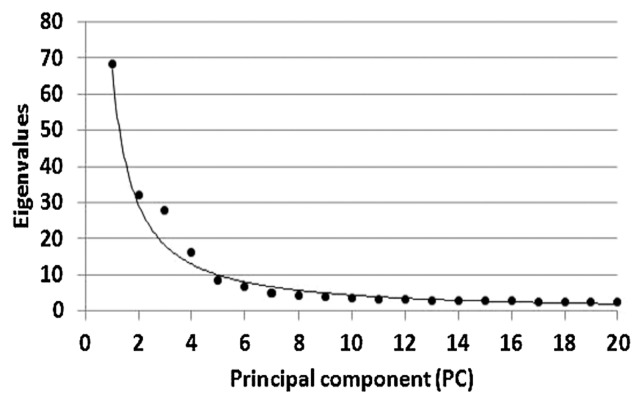

To calculate the Q matrix, the number of subpopulations (k) into accessions was first estimated by calculating the posterior probability ln(P (D)) and L′ (K) for all possible k values between 1 and 10. The true (k) value was calculated using an ad hoc quantity (Δk) described by Evanno et al. (2005). The Δk (Fig. 4) showed a clear peak at the true value k = 2. This was used to generate the Q matrix for both Q and QK models in the present study. The results were consistent with the data obtained from PCA analysis (Fig. 5). NJ method (Supplemental Fig. 2) also indicated that the accessions were grouped into two major clusters, excepting for seven accessions in the third cluster. Therefore, the value k = 2 was used. The two subpopulations (k 1 and k 2) comprised 86 and 210 accessions, respectively. The first subpopulation involved 72.1% of spring growth type and 27.9% of both facultative and winter growth types. The two-rowed spike type accessions were included in this subpopulation. The second subpopulation involved 36.6% and 63.2% of the spring and combined facultative and winter growth types, respectively.

Fig. 4.

Population structure of Asian barley based on the genetic diversity detected by 384 SNP markers. Estimation of the most probable number of clusters (k) based on delta K using 10 independent runs and k ranging from 1 to 10.

Fig. 5.

Eigenanalysis based on the 384 SNP markers of 296 barley accessions. Plot shows 20 significant axes (PCs) with eigenvalues expressed by PCs.

Linkage disequilibrium

LD analysis was performed using 384 SNPs. Decay of LD over barley genome is presented in Supplemental Fig. 3. The significance threshold is shown with a black line. The significant r2 value was set at 0.32, 0.22, 0.29, 0.32, 0.28, 0.29, and 0.28 on chromosomes 1H, 2H, 3H, 4H, 5H, 6H, and 7H, respectively. The red curve is the LOESS approximation of mean LD for all comparisons. There was no clear decay by showing the decay of LD of all genomes, and the mean distance between markers was inflated due to a relatively small number of marker pairs that were exceptionally distant. Consistent allele was below 1 cM.

QTLs identified by association mapping

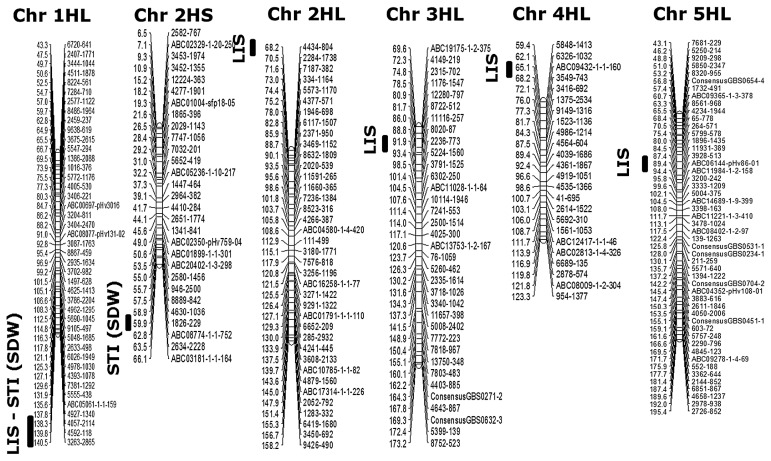

By comparing the QQ plots for all models (Naïve, Q, PCA, K, QK, and PK), the expected log10 (P-value) vs- log10 (P-value) showed stable results in the models for K, QK, and PK (Supplemental Fig. 4). The minimum −log10 (P) threshold value at a significant locus was set at 2.44 (Benjamini and Hochberg 1995). We detected a large number of significant markers for salt tolerance. Seven of the significant QTLs for salt tolerance (Table 6, Fig. 6) at the seedling stage were located on chromosomes 1H (2 QTLs), 2H (2 QTLs), 3H (1 QTL), 4H (1 QTL), and 5H (1 QTL). Five QTLs were associated with LIS and located on different chromosomes, and two QTLs were detected and associated with STI (SDW) on chromosomes 1H and 2H. The −log10 (P) value ranged from 2.50 to 4.42. Two QTLs for LIS and STI (SDW) were detected at similar positions (137.8 and 140.5 cM) on the long arm of chromosome 1H. Two QTLs associated with biomass production (SDW) and LIS were identified at the positions of 59.9 and 68.2 cM, respectively, on chromosome 2H. LIS was also associated with SNP markers 2236-773, ABC09432, and ABC06144 on chromosomes 3H, 4H, and 5H, respectively. The −log10 (P) values were 4.42, 2.57, and 2.50, respectively. The nucleotide changes caused by salt stress were [A/G] alleles at markers 3263-2865, 4434-804, 2236-773, ABC09432-1-1160, and ABC06144-pHv8601 for LIS and [A/C] and [A/G] alleles at markers 4927-1340 and 1826-229 for STI (SDW), respectively. The allele “G” improved LIS to the positive direction at all QTLs identified on chromosomes 1H, 2H, 4H, and 5H. The alleles “C” and “G” improved STI (SDW) to the positive direction on chromosomes 1H and 2H, respectively.

Table 6.

Significant marker traits associated with salt tolerance [−log10 (P) > 2.44] and their characteristics on barley chromosomes

| Traits | Chr | Marker | Position (cM) | Alleles | (+) | −log10 (P) | R2 (%) | Previous reports |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STI (SDW) | 1H | 4927-1340 | 137.8 | [A/C] | C | 2.54 | 6 | Mano and Takeda (1997), Rivandi et al. (2011) |

| STI (SDW) | 2H | 1826-229 | 59.9 | [A/G] | G | 2.54 | 3 | Nguyen et al. (2013a), Zhou et al. (2012) |

| LIS | 1H | 3263-2865 | 140.5 | [A/G] | G | 3.12 | 5 | Mano and Takeda (1997), Rivandi et al. (2011) |

| LIS | 2H | 4434-804 | 68.2 | [A/G] | G | 2.90 | 5 | Nguyen et al. (2013a) |

| LIS | 3H | 2236-773 | 91.9 | [A/G] | G | 4.42 | 8 | |

| LIS | 4H | ABC09432-1-1160 | 65.1 | [A/G] | G | 2.57 | 4 | |

| LIS | 5H | ABC06144-pHv8601 | 89.4 | [A/G] | G | 2.50 | 4 | Mano and Takeda (1997) |

(+): allele improved the specific trait to the positive direction.

R2 (%): proportion of the phenotypic variation accounted for by the QTL at each position.

LIS: leaf injury score; SDW: shoot dry weight; STI: salt tolerance index.

QTLs previously reported are mentioned by author name and year of publication.

Fig. 6.

Chromosome locations of QTLs for salt tolerance at the seedling stage associated with different traits in Asian barley accessions (right of the chromosome: distance in cM; left: SNP marker names.

: The QTLs for salt tolerance-related traits.

: The QTLs for salt tolerance-related traits.

Five QTLs for other related traits were detected on chromosomes 2H (1 QTL), 4H (3 QTLs), and 7H (1 QTL), and were associated with STI of SL, NL, RDW, and PDW (Supplemental Table 1). One QTL for STI (PDW) was detected on chromosome 2H and was found to be at the same position as STI (SDW). Three QTLs were detected on chromosome 4H in the positions 5.6, 81.7, and 87.5 cM and were associated with SL and NL. Finally, the trait STI (RDW) was associated with the marker ‘Consensus GBS0356-1’ on chromosome 7H.

Discussion

Salt tolerance evaluation

Salt tolerance is such a complicated trait that different methods (hydroponics, semi-hydroponics, pots, and fields) and parameters have been used to assess barley germplasm for salt tolerance. Assessment under saline field condition (Xue et al. 2009) has various limitations related to the variation induced by soil and climate conditions. Thus, we used a hydroponic system to evaluate salt tolerance at the germination and seedling stages to reduce environmental effects. Various phenotypic traits have been used for salt tolerance assessments as germination rate (Martinez-Cob et al. 1987), plant height (Nguyen et al. 2013a), RL (Taghipour and Salehi 2008), biomass production (Sbei et al. 2012), senescence rate (Mano and Takeda 1997), and reflectance traits (Penuelas et al. 1997, Tavakkoli et al. 2011).

The main goal of the present study was to identify a stable and determinant trait for salt tolerance and the least influenced by environmental effects. LIS and STI (SDW) were assumed as suitable parameters to assess for salt tolerance at the seedling stage because they allowed non-significant variation among accessions under control condition with non-significant variation among replications under NaCl treatment (Table 3). LIS presented the lowest coefficient of variation within the accessions and was not affected by the hydroponic system, compared with others traits used for assessment. A wide range of variation was observed among accessions in terms of STI (SDW). The biomass production of barley accessions was in significant correlation with most traits under NaCl treatment and control condition. In fact, the variation in plant response to salt was considered to provide the best means of initial selection for salt tolerance in other crops (Albacete et al. 2008, Krishnamurthy et al. 2007, Maggio et al. 2007, Veatch et al. 2004). Krishnamurthy et al. (2007) concluded that substantial variation in salt tolerance is observed among sorghum cultivars at the early vegetative stage and several tolerant and susceptible cultivars were screened based on biomass production-related traits. Albacete et al. (2008) proved that salt reduces shoot biomass in tomato by 50–60% and photosynthetic area is decreased by 20–25% due to a decrease in leaf expansion and delay in leaf appearance, while root growth is less affected, resulting in an increase in the root/shoot ratio.

On the whole, stress imposes injuries on cellular physiology and metabolic dysfunction. Leaf injury imposes a negative influence on cell division and plant growth. This is an indirect advantage to plants, as any reduction of leaf expansion reduces the surface area of leaves exposed to transpiration and thereby reduces water loss. Plants prevent water loss from cells and protect cellular proteins by the synthesis of compatibles solutes. This comprises another specific mechanism to overcome the hyper saline environment, permitting plants to thrive in these conditions by adjusting their internal osmotic status (Roslyakova et al. 2011). Decreasing the entry of NaCl into plants through the Na+/H+ vacuolar antiporters and sequestering the excess Na+ in vacuoles by tonoplast Na+/H+ antiporters may be the principal mechanisms involved in the protection of plants from salt stress.

By combining the results of the relationship between salt tolerance [STI (SDW) and LIS] and geographical distribution, we realized that biomass production of accessions originating from Japan and Bhutan were not highly affected by salt stress, compared with others. In addition, the Japanese accessions showed the lowest levels of leaf injury (necrosis and chlorosis). Thus, salt tolerance may be related to the origin of accessions and geographical distribution. Hadado et al. (2009) and Malysheva-Otto et al. (2006) found that the high diversity in African and Asian barley accessions was due to hybridization and natural selection under diversified environments. Malysheva-Otto et al. (2006) showed that molecular diversity in barley accessions from various geographic regions worldwide differs with respect to allelic richness, frequency of unique alleles, and extent of heterogeneity.

QTL detection for salt tolerance

A large number of QTLs for salt tolerance have been previously detected in different barley germplasm (Aminfar et al. 2011, Eleuch et al. 2008, Ellis et al. 2002, Mano and Takeda 1997, Nguyen et al. 2013a, 2013b, Rivandi et al. 2011, Shavrukov et al. 2010, Taghipour and Salehi 2008, Xue et al. 2009, Zhou et al. 2012). Different mapping populations have been developed to detect QTLs. For example, Mano and Takeda (1997) identified QTLs for salt tolerance at the germination and seedling stages using two DH populations derived from the crosses of Steptoe/Morex and Harrington/TR306. Recently, researchers have focused more on identifying QTLs for salt tolerance at the germination and seedling stages by association analysis using worldwide barley core collections to resolve the limitation of biparental segregating populations. For instance, Qiu et al. (2011) and Wu et al. (2011) examined tissue dry biomass and the Na+ and K+ contents of 188 Tibetan barley accessions under 300 mM of NaCl at an early growth stage. Nguyen et al. (2013a) evaluated the spring barley collection for salt tolerance (200 mM of NaCl) at the vegetative stage using a hydroponic system and detected QTLs for salt tolerance through an AM approach.

In the present study, QTLs for salt tolerance at the seedling stage in Asian barley accessions were detected by association analysis with 384 SNP marker systems (Table 6). Seven significant QTLs for salt tolerance were mapped on chromosomes 1H (2 QTLs), 2H (2 QTLs), 3H (1 QTL), 4H (1 QTL), and 5H (1 QTL); five and two of these QTLs were associated with LIS and STI (SDW), respectively. Among the seven QTLs, five QTLs had been previously reported (Mano and Takeda 1997, Nguyen et al. 2013a, Rivandi et al. 2011, Zhou et al. 2012). Only two QTLs for LIS were newly detected on chromosomes 3H and 4H through the present study. Two QTLs for LIS and SDW were detected at similar regions (137.8 and 140.5 cM) on the long arm of chromosome 1H. These QTLs were previously reported by Mano and Takeda (1997) and closely linked to HvNax4 (Rivandi et al. 2011), which is a gene controlling an environmentally sensitive Na+ exclusion. In the present study, two QTLs associated with STI (SDW) and LIS were detected at the position 59.9 cM on the short arm of chromosome 2H and 68.2 cM on the long arm of chromosome 2H, respectively. At a similar region (59.2 cM) to these QTLs for STI (SDW) and LIS, QTLs for leaf senescence and SL were detected (Nguyen et al. 2013a). Zhou et al. (2012) also detected QTL for combined injury score and plant survival at the position 48 cM. On the other hand, another QTL for LIS was mapped at the position 65.1 cM on chromosome 4H and closely linked to the vernalization gene VRN-H2 (von Zitzewitz et al. 2005) at the position 66 cM. Another QTL for LIS at the position 89.2 cM on chromosome 5H was mapped at an adjacent region, including the QTL for salt tolerance reported elsewhere (Mano and Takeda 1997). The VRN-H1 gene was located at the position 98 cM (Szucs et al. 2006), with a distance of 8.8 cM from the QTL for salt tolerance on chromosome 5H. Newly detected QTLs for LIS on chromosomes 3H and 4H should be confirmed by QTL analysis using segregating mapping population.

There have been many reports on salt tolerance at the early growth stage in barley, but very little attention has been given to the reproductive stage. The lack of economically valuable methods for screening salt tolerance in the field remains an obstacle to breeders. However, yield is the complex end product of many factors which jointly or singly influence grain yield. A study on salt tolerance in barley germplasm can be undertaken in further studies. One of the focuses in future studies is to investigate the relationship between vernalization requirement and salt tolerance.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

This research was carried out by a GRANDE project supported by JST/JICA, SATREPS (Science and Technology Research Partnership for Sustainable Development), Japan. Barley accessions were provided by the Institute of Plant Science and Resources, Okayama University, with support in part by the National Bio-Resource Project of MEXT, Japan.

Literature Cited

- Albacete, A., Ghanem, M.E., Martínez-Andújar, C., Acosta, M., Sánchez-Bravo, J., Martínez, V., Lutts, S., Dodd, I.C. and Pérez-Alfocea, F. (2008) Hormonal changes in relation to biomass partitioning and shoot growth impairment in salinized tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) plants. J. Exp. Bot. 59: 4119–4131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aminfar, Z., Dadmehr, M., Korouzhdehi, B., Siasar, B. and Heidari, M. (2011) Determination of chromosomes that control physiological traits associated with salt tolerance in barley at the seedling stage. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 10: 8794–8799. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini, Y. and Hochberg, Y. (1995) Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Statist. Soc. B 57: 289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Hamida, W., Rebaï, A. and Hamza, S. (2009) Partial genetic map of Hordeum vulgare based on Tunisian doubled haploid population and SSRs markers. Int. J. Genet. Mol. Biol. 1: 24–30. [Google Scholar]

- Bohnert, H.J. and Bressan, R.A. (2001) Abiotic stresses, plant reactions, and approaches towards improving stress tolerance. In:Nössberger, J. (ed.) Crop Science: Progress and prospects, Wallingford, UK, CABI, pp. 81–100. [Google Scholar]

- von Bothmer, R., Jacobsen, N., Baden, C., Jorgensen, R.B. and Linde-Laursen, I. (1995) An ecogeographical study of the genus Hordeum. 2nd edition Systemetic and ecogeographic studies on crop gene-pools 7 IPGRI, Rome. [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury, P.J., Zhang, Z., Kroon, D.E., Casstevens, T.M., Ramdoss, Y. and Buckler, E.S. (2007) TASSEL: software for association mapping of complex traits in diverse samples. Bioinformatics 23: 2633–2635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breseghello, F. and Sorrells, M.E. (2006) Association mapping of kernel size and milling quality in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) cultivars. Genetics 172: 1165–1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerda, B.J.S. and Cloutier, S. (2012) Association mapping in plant genomes. In:Caliskan, M. (ed.) Genetic diversity in plants, InTech, pp. 29–55 Available from: http://www.intechopen.com/books/genetic-diversity-in-plants/association-mapping-in-plant-genomes. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z., Newman, I., Zhou, M., Mendham, N., Zhang, G. and Shabala, S. (2005) Screening plants for salt tolerance by measuring K+ flux: a case study for barley. Plant Cell Environ. 28: 1230–1246. [Google Scholar]

- Close, T.J., Bhat, P.R., Lonardi, S., Wu, Y., Rostoks, N., Ramsay, L., Druka, A., Stein, N., Svensson, J.T., Wanamaker, S.et al. (2009) Development and implementation of high-throughput SNP genotyping in barley. BMC Genomics 10: 582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comadran, J., Thomas, W.T.B., van-Eeuwijk, F.A., Ceccarelli, S., Grando, S., Stanca, A.M., Pecchioni, N., Akar, T., Al-Yassin, A., Benbelkacem, A.et al. (2009) Patterns of genetic diversity and linkage disequilibrium in a highly structured Hordeum vulgare association-mapping population for the Mediterranean basin. Theor. Appl. Genet. 119: 175–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eleuch, L., Jilal, A., Grando, S., Ceccarelli, S., Schmising, M.V.K., Tsujimoto, H., Hajer, A., Daaloul, A. and Baum, M. (2008) Genetic diversity and association analysis for salinity tolerance, heading date and plant height of barley germplasm using simple sequence repeat markers. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 50: 1005–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, R.P., Forster, B.P., Gordon, D.C., Handley, L.L., Keith, R.P., Lawrence, P., Meyer, R., Powell, W., Robinson, D., Scrimgeour, C.M.et al. (2002) Phenotype/genotype associations for field and salt tolerance in a barley mapping populations segregating for two dwarfing genes. J. Exp. Bot. 53: 1163–1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evanno, G., Regnaut, S. and Goudet, J. (2005) Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software STRUCTURE: a simulation study. Mol. Ecol. 14: 2611–2620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan, J.B., Gunderson, K.L., Bibikova, M., Yeakley, J.M., Chen, J., Wickham Garcia, E., Lebruska, L.L., Laurent, M., Shen, R. and Barker, D. (2006) Illumina universal bead arrays. Meth. Enzymol. 410: 57–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flint-Garcia, S.A., Thornsberry, J.M. and Buckler, E.S. (2003) Structure of linkage disequilibrium in plants. Ann. Rev. Plant Biol. 54: 357–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster, B.P. (2001) Mutation genetics of salt tolerance in barley: An assessment of Golden Promise and other semi-dwarf mutants. Euphytica 120: 317–328. [Google Scholar]

- Forster, B.P., Ellis, R.P., Thomas, W.T.B., Newton, A.C., Tuberosa, R., This, D., El-Enein, R.A., Bahri, M.H. and Ben-Salem, M. (2000) The development and application of molecular markers for abiotic stress tolerance in barley. J. Exp. Bot. 5: 19–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster, G.N., Blake, S., Tones, S.J., Barker, I. and Harrington, R. (2004) Occurrence of barley Yellow dwarf virus in autumn-sown cereal crops in the United Kingdom in relation to field characteristics. Pest Manag. Sci. 60: 113–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregorio, B.G., Senadhira, D. and Mendoza, R.D. (1997) Screening rice for salinity tolerance. IRRI discussion paper series (22). [Google Scholar]

- Guimaraes, E.P. (2009) Rice breeding. In: Carena, M.J. (ed.) Handbook of Plant Breeding: Cereals, Springer Science + Business Media, pp. 99–126. [Google Scholar]

- Hadado, T.T., Rau, D., Bitocchi, E. and Papa, R. (2009) Genetic diversity of barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) landraces from the central highlands of Ethiopia: comparison between the Belg and Meher growing seasons using morphological traits. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 56: 1131–1148. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, M.M. and Nonami, H. (2012) Effect of salt stress on physiological response of tomato fruit grown in hydroponic culture system. Hort. Sci. 39: 26–32. [Google Scholar]

- Kraakman, A.T.W., Martínez, F., Mussiraliev, B., van Eeuwijk, F.A. and Niks, R.E. (2006) Linkage disequilibrium mapping of morphological, resistance, and other agronomically relevant traits in modern spring barley cultivars. Mol. Breed. 17: 41–58. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamurthy, L., Serraj, R., Hash, C.T., Dakheel, A.J. and Reddy, B.V.S. (2007) Screening sorghum genotypes for salinity tolerant biomass production. Euphytica 156: 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.D., Smothers, S.L., Dunn, D., Villagarcia, M., Shumway, C.R., Carter, T.E. and Shannon, J.G. (2008) Evaluation of a simple method to screen soybean genotypes for salt tolerance. Crop Sci. 48: 2194–2200. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C., Zhuang, G. and Lance, R. (2007) Recent advances in breeding barley for drought and saline stress tolerance. In: Jenks, M.A., Hasegawa, P.M., Jain, S.M. (eds.) Advances in Molecular Breeding toward Drought and Salt Tolerant Crops, Springer, pp. 603–626. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J., Lühmanns, A.K., Weibleder, K. and Stich, B. (2011) Genome-wide distribution of genetic diversity and linkage disequilibrium in elite sugar beet germplasm. BMC Genomics 12: 484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F., Bothmer, von R. and Salomon, B. (1999) Genetic diversity among East Asian accessions of the barley core collection as revealed by six isozyme loci. Theor. Appl. Genet. 98: 1226–1233. [Google Scholar]

- Maggio, A., Raimondi, G., Martino, A. and Pascale, S.D. (2007) Salt stress response in tomato beyond the salinity tolerance threshold. Environ. Exp. Bot. 59: 276–282. [Google Scholar]

- Malysheva-Otto, L.V., Ganal, M.W. and Röder, M.S. (2006) Analysis of molecular diversity, population structure and linkage disequilibrium in a worldwide survey of cultivated barley germplasm (Hordeum vulgare L.). BMC Genetics 7: 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mano, Y. and Takeda, K. (1997) Mapping quantitative trait loci for salt tolerance at germination and the seedling stage in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). Euphytica 94: 263–272. [Google Scholar]

- Marcel, T.C., Aghnoum, R., Durand, J., Varshney, R.K. and Niks, R.E. (2007) Dissection of the barley 2L1.0 region carrying the Laevigatum quantitative resistance gene to leaf rust using near-isogenic lines (NIL) and subNIL. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 20: 1604–1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Cob, A., Aragües, R. and Royo, A. (1987) Salt tolerance of barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) cultivars at the germination stage: analysis of the response functions. Plant Soil 104: 53–56. [Google Scholar]

- Munns, R. (2002) Comparative physiology of salt and water stress. Plant Cell Environ. 25: 239–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munns, R. (2005) Genes and salt tolerance: bringing them together. New Phytol. 167: 645–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munns, R. and Tester, M. (2008) Mechanisms of salinity tolerance. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 59: 651–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munns, R., Husain, S., Rivelli, A.R., James, R.A., Condon, A.G., Lindsay, M.P., Lagudah, E.S., Schachtman, D.P. and Hare, R.A. (2002) Avenues for increasing salt tolerance of crops, and the role of physiologically based selection traits. Plant Soil 247: 93–105. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, V.L., Dolstra, O., Malosetti, M., Kilian, B., Graner, A., Visser, R.G.F. and van der Linden, C.G. (2013a) Association mapping of salt tolerance in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 126: 2335–2351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, V.L., Ribot, S.A., Dolstra, O., Niks, R.E., Visser, R.G.F. and van der Linden, C.G. (2013b) Identification of quantitative trait loci for ion homeostasis and salt tolerance in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). Mol. Breed. 31: 137–152. [Google Scholar]

- Oraguzie, N.C., Rikkerink, E.H.A., Gardiner, S.E. and de Silva, H.N. (2007) Association Mapping in Plants, Springer, New York, p. 277. [Google Scholar]

- Pasam, R.K., Sharma, R., Malosetti, M., van Eeuwijk, F.A., Haseneyer, G., Kilian, B. and Graner, A. (2012) Genome-wide association studies for agronomical traits in a worldwide spring barley collection. BMC Plant Biol. 12: 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson, N., Price, A.L. and Reich, D. (2006) Population structure and eigenanalysis. PLoS Genet. 2: 2074–2093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peñuelas, J., Isla, R., Filella, I. and Araus, J.L. (1997) Visible and near-infrared reflectance assessment of salinity effects on barley. Crop Sci. 37: 198–202. [Google Scholar]

- Platten, J.D., Egdane, J.A. and Ismail, A.M. (2013) Salinity tolerance, Na+ exclusion and allele mining of HKT1;5 in Oryza sativa and O. glaberrima: many sources, many genes, one mechanism? BMC Plant Biol. 13: 32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakash, V. and Verma, R.P.S. (2006) Comparison of variability generated through biparental mating and selfting in six rowed barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). Crop Improvement 33: 49–52. [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard, J.K., Stephens, M. and Donnelly, P. (2000) Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics 155: 945–959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, L., Wu, D., Ali, S., Cai, S., Dai, F., Jin, X., Wu, F. and Zhang, G. (2011) Evaluation of salinity tolerance and analysis of allelic function of HvHKT1 and HvHKT2 in Tibetan wild barley. Theor. Appl. Genet. 122: 695–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajendran, K., Tester, M. and Roy, S.J. (2009) Quantifying the three main components of salinity tolerance in cereals. Plant Cell Environ. 32: 237–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivandi, J., Miyazaki, J., Hrmova, M., Pallotta, M., Tester, M. and Collins, N.C. (2011) A SOS3 homologue maps to HvNax4, a barley locus controlling an environmentally sensitive Na+ exclusion trait. J. Exp. Bot. 62: 1201–1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roslyakova, T.V., Molchan, O.V., Vasekina, A.V., Lazareva, E.M., Sokolik, A.I., Yurin, V.M., de Boer, A.H. and Babakov, A.V. (2011) Salt tolerance of barley: relations between expression of isoforms of vacuolar Na+/H+-antiporter and 22Na+ accumulation. Russ. J. Plant Physl. 58: 24–35. [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute Inc. (2011) Base SAS 9.3 procedures guide: statistical procedures. Cary, North Carolina: SAS Institute Inc., p. 528. [Google Scholar]

- Sato, K. and Takeda, K. (2009) An application of high-throughput SNP genotyping for barley genome mapping and characterization of recombinant chromosome substitution lines. Theor. Appl. Genet. 119: 613–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sbei, H., Hammami, Z., Trifa, Y., Hamza, S. and Harrabi, M. (2012) Phenotypic diversity analysis for salinity tolerance of Tunisian barley populations (Hordeum vulgare L.). J. Arid Land Studies 22: 57–60. [Google Scholar]

- Shavrukov, Y., Gupta, N.K., Miyazaki, J., Baho, M.N., Chalmers, K.J., Tester, M., Langridge, P. and Collins, N.C. (2010) HvNax3—a locus controlling shoot sodium exclusion derived from wild barley (Hordeum vulgare ssp. spontaneum). Funct. Integr. Genomics 10: 277–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinohara, M., Aoyama, C., Fujiwara, K., Watanabe, A., Ohmori, H., Uehara, Y. and Takano, M. (2011) Microbial mineralization of organic nitrogen into nitrate to allow the use of organic fertilizer in hydroponics. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 57: 190–203. [Google Scholar]

- SPSS Inc. (2010) GPL Reference Guide for IBM SPSS Statistics. SPSS Inc. 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Szűcs, P., Karsai, I., von Zitzewitz, J., Mészáros, K., Cooper, L.L.D., Gu, Y.Q., Chen, T.H.H., Hayes, P.M. and Skinner, J.S. (2006) Positional relationships between photoperiod response QTL and photoreceptor and vernalization genes in barley. Theor. Appl. Genet. 112: 1277–1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taghipour, F. and Salehi, M. (2008) The study of salt tolerance of Iranian barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) genotypes in seedling growth stages. Am. Eurasian J. Agric. Environ. Sci. 4: 525–529. [Google Scholar]

- Tavakkoli, E., Fatehi, F., Coventry, S., Rengasamy, P. and McDonald, G.K. (2011) Additive effects of Na+ and Cl− ions on barley growth under salinity stress. J. Exp. Bot. 62: 2189–2203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tester, M. and Davenport, R. (2003) Na+ tolerance and Na+ transport in higher plants. Ann. Bot. 91: 503–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upadhyaya, H.D., Wang, Y.H., Gowda, C.L.L. and Sharma, S. (2013) Association mapping of maturity and plant height using SNP markers with the sorghum mini core collection. Theor. Appl. Genet. 126: 2003–2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varshney, R.K., Marcel, T.C., Ramsay, L., Russell, J., Röder, M.S., Stein, N., Waugh, R., Langridge, P., Niks, R.E. and Graner, A. (2007) A high density barley microsatellite consensus map with 775 SSR loci. Theor. Appl. Genet. 114: 1091–1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veatch, M.E., Smith, S.E. and Vandemark, G. (2004) Shoot biomass production among accessions of Medicago truncatula exposed to NaCl. Crop Sci. 44: 1008–1013. [Google Scholar]

- Visioni, A., Tondelli, A., Francia, E., Pswarayi, A., Malosetti, M., Russell, J., Thomas, W., Waugh, R., Pecchioni, N., Romagosa, I.et al. (2013) Genome-wide association mapping of frost tolerance in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). BMC Genomics 14: 424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Zitzewitz, J., Szűcs, P., Dubcovsky, J., Yan, L., Francia, E., Pecchioni, N., Casas, A., Chen, T.H.H., Hayes, P.M. and Skinner, J.S. (2005) Molecular and structural characterization of barley vernalization genes. Plant Mol. Biol. 59: 449–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vysotskaya, L., Hedley, E.P., Sharipova, G., Veselov, D., Kudoyarova, G., Morris, J. and Jones, H.G. (2010) Effect of salinity on water relations of wild barley plants differing in salt tolerance. AoB Plants: plq006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witzel, K., Weidner, A., Surabhi, G.K., Varshney, R.K., Kunze, G., Buck-Sorlin, G.H., Börner, A. and Mock, H.P. (2010) Comparative analysis of the grain proteome fraction in barley genotypes with contrasting salinity tolerance during germination. Plant Cell Environ. 33: 211–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, D., Qiu, L., Xu, L., Ye, L., Chen, M., Sun, D., Chen, Z., Zhang, H., Jin, X., Dai, F.et al. 2011) Genetic variation of HvCBF genes and their association with salinity tolerance in Tibetan annual wild barley. PLoS One 6: e22938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue, D., Huang, Y., Zhang, X., Wei, K., Westcott, S., Li, C., Chen, M., Zhang, G. and Lance, R. (2009) Identification of QTLs associated with salinity tolerance at late growth stage in barley. Euphytica 169: 187–196. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, R., Wang, J., Li, C., Johnson, P., Lu, C. and Zhou, M. (2012) A single locus is responsible for salinity tolerance in a Chinese landrace barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). PLoS One 7: e43079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu, S., Wang, W. and Wang, B. (2012) Recent progress of salinity tolerance research in plants. Russ. J. Genet. 48: 497–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, G., Johnson, P., Ryan, P.R., Delhaize, E. and Zhou, M. (2012) Quantitative trait loci for salinity tolerance in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). Mol. Breed. 29: 427–436. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.