Significance

Wolfram syndrome is an autosomal recessive disorder characterized by juvenile diabetes and neurodegeneration, and is considered a prototype of human endoplasmic reticulum (ER) disease. Wolfram syndrome is caused by loss of function mutations of Wolfram syndrome 1 or Wolfram syndrome 2 genes, which encode transmembrane proteins localized to the ER. Despite its rarity, Wolfram syndrome represents the best human disease model currently available to identify drugs and biomarkers associated with ER health. Furthermore, this syndrome is ideal for studying the mechanisms of ER stress-mediated death of neurons and β cells. Here we report that the pathway leading to calpain activation offers potential drug targets for Wolfram syndrome and substrates for calpain might serve as biomarkers for this syndrome.

Keywords: Wolfram syndrome, endoplasmic reticulum, diabetes, neurodegeneration, treatment

Abstract

Wolfram syndrome is a genetic disorder characterized by diabetes and neurodegeneration and considered as an endoplasmic reticulum (ER) disease. Despite the underlying importance of ER dysfunction in Wolfram syndrome and the identification of two causative genes, Wolfram syndrome 1 (WFS1) and Wolfram syndrome 2 (WFS2), a molecular mechanism linking the ER to death of neurons and β cells has not been elucidated. Here we implicate calpain 2 in the mechanism of cell death in Wolfram syndrome. Calpain 2 is negatively regulated by WFS2, and elevated activation of calpain 2 by WFS2-knockdown correlates with cell death. Calpain activation is also induced by high cytosolic calcium mediated by the loss of function of WFS1. Calpain hyperactivation is observed in the WFS1 knockout mouse as well as in neural progenitor cells derived from induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells of Wolfram syndrome patients. A small-scale small-molecule screen targeting ER calcium homeostasis reveals that dantrolene can prevent cell death in neural progenitor cells derived from Wolfram syndrome iPS cells. Our results demonstrate that calpain and the pathway leading its activation provides potential therapeutic targets for Wolfram syndrome and other ER diseases.

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) takes center stage for protein production, redox regulation, calcium homeostasis, and cell death (1, 2). It follows that genetic or acquired ER dysfunction can trigger a variety of common diseases, including neurodegenerative diseases, metabolic disorders, and inflammatory bowel disease (3, 4). Breakdown in ER function is also associated with genetic disorders such as Wolfram syndrome (5–8). It is challenging to determine the exact effects of ER dysfunction on the fate of affected cells in common diseases with polygenic and multifactorial etiologies. In contrast, we reasoned that it should be possible to define the role of ER dysfunction in mechanistically homogenous patient populations, especially in rare diseases with a monogenic basis, such as Wolfram syndrome (9).

Wolfram syndrome (OMIM 222300) is a rare autosomal recessive disorder characterized by juvenile-onset diabetes mellitus and bilateral optic atrophy (7). Insulin-dependent diabetes usually occurs as the initial manifestation during the first decade of life, whereas the diagnosis of Wolfram syndrome is invariably later, with onset of symptoms in the second and ensuing decades (7, 10, 11). Two causative genes for this genetic disorder have been identified and named Wolfram syndrome 1 (WFS1) and Wolfram syndrome 2 (WFS2) (12, 13). It has been shown that multiple mutations in the WFS1 gene, as well as a specific mutation in the WFS2 gene, lead to β cell death and neurodegeneration through ER and mitochondrial dysfunction (5, 6, 14–16). WFS1 gene variants are also associated with a risk of type 2 diabetes (17). Moreover, a specific WFS1 variant can cause autosomal dominant diabetes (18), raising the possibility that this rare disorder is relevant to common molecular mechanisms altered in diabetes and other human chronic diseases in which ER dysfunction is involved.

Despite the underlying importance of ER malfunction in Wolfram syndrome, and the identification of WFS1 and WFS2 genes, a molecular mechanism linking the ER to death of neurons and β cells has not been elucidated. Here we show that the calpain protease provides a mechanistic link between the ER and death of neurons and β cells in Wolfram syndrome.

Results

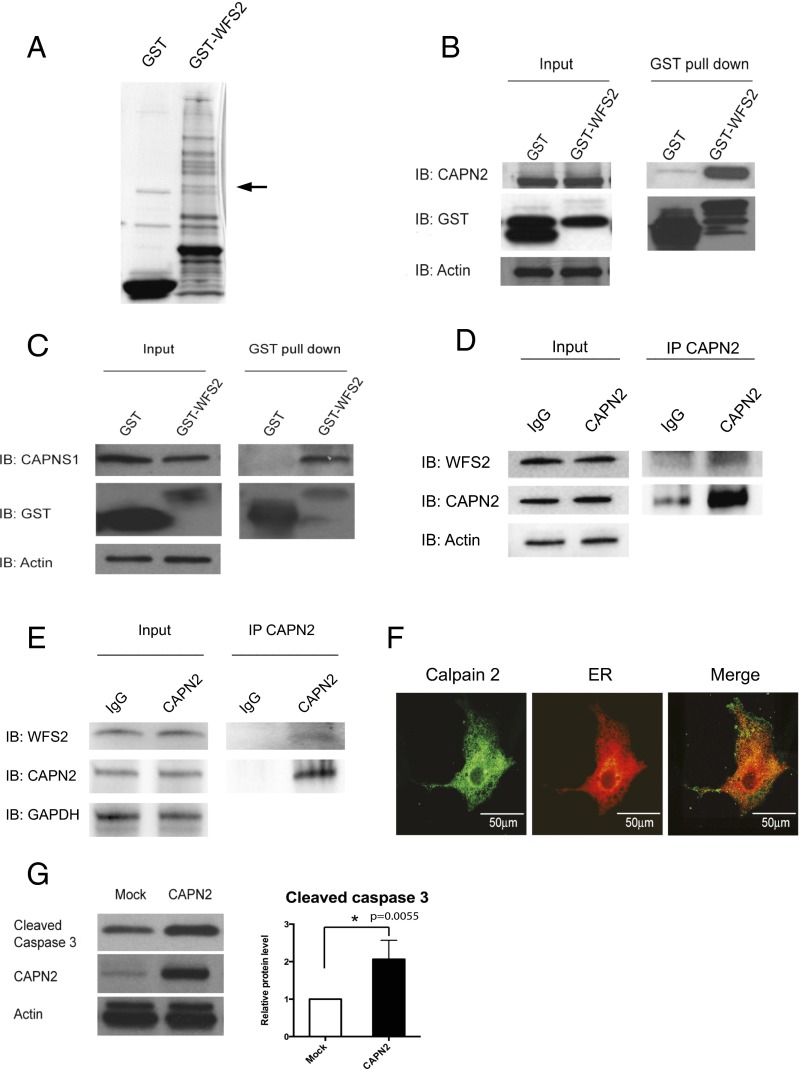

The causative genes for Wolfram syndrome, WFS1 and WFS2, encode transmembrane proteins localized to the ER (5, 12, 13). Mutations in the WFS1 or WFS2 have been shown to induce neuronal and β cell death. To determine the cell death pathways emanating from the ER, we sought proteins associated with Wolfram syndrome causative gene products. HEK293 cells were transfected with a GST-tagged WFS2 expression plasmid. The GST-WFS2 protein was purified along with associated proteins on a glutathione affinity resin. These proteins were separated by SDS/PAGE and visualized by Coomassie staining. Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectroscopic analysis revealed 13 interacting proteins (Table S1), and one of the WFS2-associated polypeptides was CAPN2, the catalytic subunit of calpain 2, a member of the calcium dependent cysteine proteases family whose members mediate diverse biological functions including cell death (19–21) (Fig. 1A). Previous studies have shown that calpain 2 activation is regulated on the ER membrane and it plays a role in ER stress-induced apoptosis and β cell death (20, 22–24), which prompted us to study the role of WFS2 in calpain 2 activation.

Fig. 1.

WFS2 interacts with CAPN2. (A) Affinity purification of WFS2-associated proteins from HEK293 cells transfected with GST or GST-WFS2 expression plasmid. Proteins were separated by SDS/PAGE and visualized by Coomassie blue staining. CAPN2 was identified by MALDI-TOF analysis and denoted by an arrow. (B) GST-tagged WFS2 was pulled down on a glutathione affinity resin from lysates of HEK293 cells transfected with a GST-WFS2 expression plasmid, and the pulled-down products were analyzed for CAPN2 by immunoblotting with anti-CAPN2 antibody. (C) GST-tagged WFS2 was pulled down on a glutathione affinity resin from lysates of HEK293 cells transfected with GST-WFS2 expression plasmid and the pulled-down products were analyzed for CAPNS1 by immunoblotting with anti-CAPNS1 antibody. (D) Lysates of Neuro2a cells were immunoprecipitated with IgG or anti-calpain 2 antibodies. Lysates of IgG and anti-calpain 2 immunoprecipitates were analyzed for WFS2, CAPN2 or actin by immunoblotting. (E) Lysates of INS-1 832/13 cells were immunoprecipitated with IgG or anti-calpain 2 antibody. Lysates of IgG and anti-calpain 2 immunoprecipitates were analyzed for WFS2, CAPN2 or actin by immunoblotting. (F) COS7 cells were transfected with pDsRed2-ER vector (Center) and stained with anti-calpain 2 antibody (Left). (Right) A merged image is shown. (G) HEK293 cells were transfected with empty expression plasmid or a CAPN2 expression plasmid. Apoptosis was monitored by immunoblotting analysis of caspase 3 cleavage. (Left) Expression levels of CAPN2 and actin were measured by immunoblotting. (Right) Quantification of immunoblot is shown (n = 3, *P < 0.05).

Calpain 2 is a heterodimer consisting the CAPN2 catalytic subunit and the CAPNS1 (previously known as CAPN4) regulatory subunit. We first verified that WFS2 interacts with calpain 2 by showing that endogenous calpain 2 subunits CAPN2 (Fig. 1B) and CAPNS1 (Fig. 1C) each associated with GST-tagged WFS2 expressed in HEK293 cells. Endogenous CAPN2 was also found to be coimmunoprecipated with N- or C-terminal FLAG-tagged WFS2 expressed in HEK293 cells (Fig. S1 A and B, respectively). To further confirm these findings, we performed a coimmunoprecipitation experiment in Neuro2a cells (a mouse neuroblastoma cell line) and INS-1 832/13 cells (a rat pancreatic β cell line) and found that endogenous WFS2 interacted with endogenous CAPN2 (Fig. 1 D and E). WFS2 is known to be a transmembrane protein localized to the ER. We therefore explored the possibility that calpain 2 might also localize to the ER. We transfected COS7 cells with pDsRed2-ER vector to visualize ER. Immunofluorescence staining of COS7 cells showed that endogenous calpain 2 was mainly localized to the cytosol, but also showed that a small portion colocalized with DsRed2-ER protein at the ER (Fig. 1F). Cell fractionation followed by immunoblot further confirmed this observation (Fig. S1C). Collectively, these results suggest that calpain 2 interacts with WFS2 at the cytosolic face of the ER.

Calpain hyperactivation has been shown to contribute to cell loss in various diseases (19), raising the possibility that calpain 2 might be involved in the regulation of cell death. To verify this issue, we overexpressed CAPN2, the catalytic subunit of calpain 2, and observed increase of cleaved caspase-3 in HEK293 cells indicating that hyperactivation of calpain 2 induces cell death (Fig. 1G).

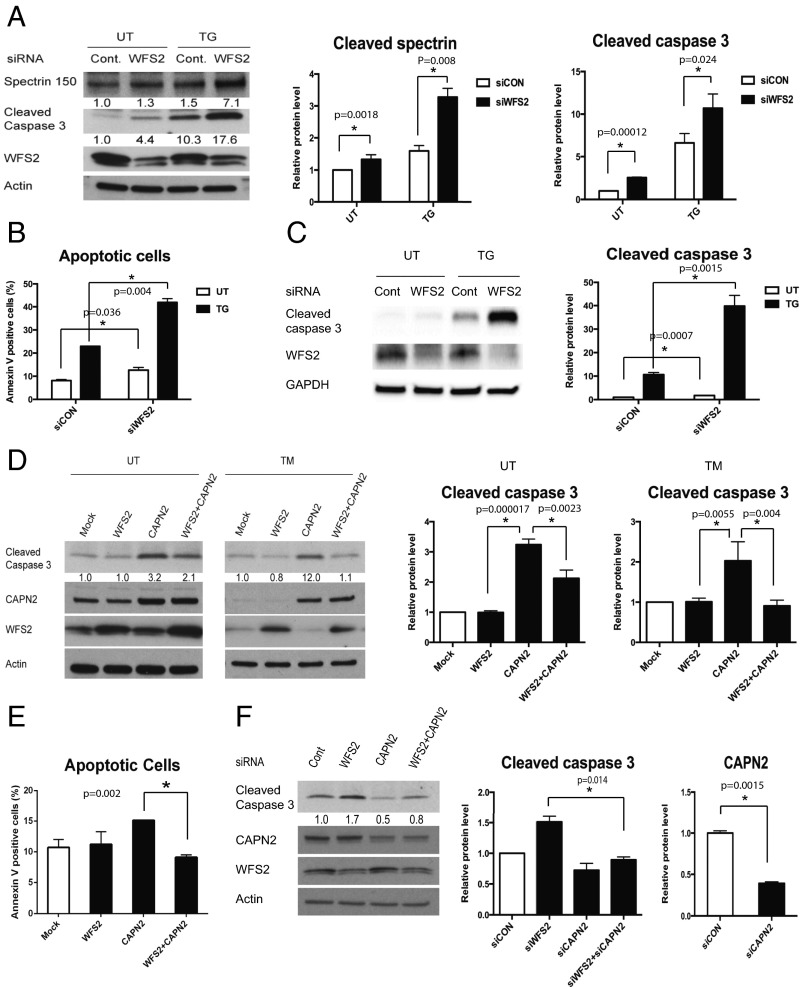

To determine whether WFS2 plays a role in cell survival, we suppressed WFS2 expression in mouse neuronal NSC34 cells using siRNA and measured cell death under normal and ER stress conditions. WFS2 knockdown was associated with increased cleavage of caspase-3 in normal or ER stressed conditions (Fig. 2 A and B). We subsequently evaluated calpain 2 activation by measuring the cleavage of alpha II spectrin, a substrate for calpain 2. RNAi-mediated knockdown of WFS2 induced calpain activation, especially under ER stress conditions (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

WFS2 suppresses cell death mediated by CAPN2. (A) NSC34 cells were transfected with control scrambled siRNA or siRNA directed against WFS2, and then treated with 0.5µM thapsigargin (TG) for 6 h or untreated (UT). Apoptosis was monitored by immunoblotting analysis of cleaved caspase 3. (Left) Protein levels of cleaved spectrin, WFS2, and actin were measured by immunoblotting. (Right) Quantifications of cleaved spectrin and cleaved caspase 3 are shown (n = 5, *P < 0.05). (B) NSC34 cells were transfected with control scrambled siRNA or siRNA directed against WFS2, and then treated with 0.5 µM thapsigargin (TG) for 6 h or untreated (UT). Apoptosis was monitored by Annexin V staining followed by flow cytometry analysis. (n = 3, *P < 0.05). (C) INS-1 832/13 cells were transfected with control scrambled siRNA or siRNA directed against WFS2, and then treated with 0.5 µM thapsigargin (TG) for 6 h or untreated (UT). (Left) Expression levels of cleaved caspase 3, WFS2, and actin were measured by immunoblotting. (Right) Protein levels of cleaved caspase 3 are quantified (n = 3, *P < 0.05). (D) NSC34 cells were transfected with empty expression plasmid (Mock), WFS2 expression plasmid, CAPN2 expression plasmid or cotransfected with WFS1 and CAPN2 expression plasmids. Twenty-four h post transfection, cells were treated with 5 µg/mL tunicamycin (TM) for 16 h or untreated (UT). Apoptosis was monitored by immunoblotting analysis of the relative levels of cleaved caspase 3 (indicated in Left). Expression levels of CAPN2, WFS2, and actin were also measured by immunoblotting. Quantification of cleaved caspase 3 levels under untreated (Center) and tunicamycin treated (Right) conditions are shown as bar graphs. (n = 5, *P < 0.05). (E) Neuro2a cells transfected with empty expression plasmid (Mock), WFS2 expression plasmid, CAPN2 expression plasmid or cotransfected with WFS1 and CAPN2 expression plasmids were examined for apoptosis by Annexin V staining followed by flow cytometry analysis (Right, n = 3, *P < 0.05). (F) NSC34 cells were transfected with scrambled siRNA (Cont), WFS2 siRNA, CAPN2 siRNA or cotransfected with WFS2 siRNA and CAPN2 siRNA. Apoptosis was detected by immunoblotting of cleaved caspase 3. (Left) Protein levels of CAPN2, WFS2 and actin were also shown. (Right) Quantification of immunoblotting is shown (n = 3, *P < 0.05).

In patients with Wolfram syndrome, destruction of β cells leads to juvenile-onset diabetes (25). This finding prompted us to examine whether WFS2 was also involved in pancreatic β cell death. As was seen in neuronal cells, knockdown of WFS2 in rodent β cell lines INS1 832/13 (Fig. 2C) and MIN6 (Fig. S2) was also associated with increased caspase-3 cleavage under both normal and ER stress conditions. The association of WFS2 with calpain 2 and their involvement in cell viability suggested that calpain 2 activation might be the cause of cell death in WFS2-deficient cells. To further explore the relationship between WFS2 and calpain 2, we expressed WFS2 together with the calpain 2 catalytic subunit CAPN2 and measured apoptosis. Ectopic expression of WFS2 significantly suppressed calpain 2-associated apoptosis under normal and ER stress conditions (Fig. 2D, lane 4 and lane 8, and Fig. 2E). Next, we tested whether CAPN2 mediates cell death induced by WFS2 deficiency. When CAPN2 was silenced in WFS2-deficient cells, apoptosis was partially suppressed compared with untreated WFS2-deficient cells (Fig. 2F). Taken together, these results suggest that WFS2 is a negative regulator of calpain 2 proapoptotic functions.

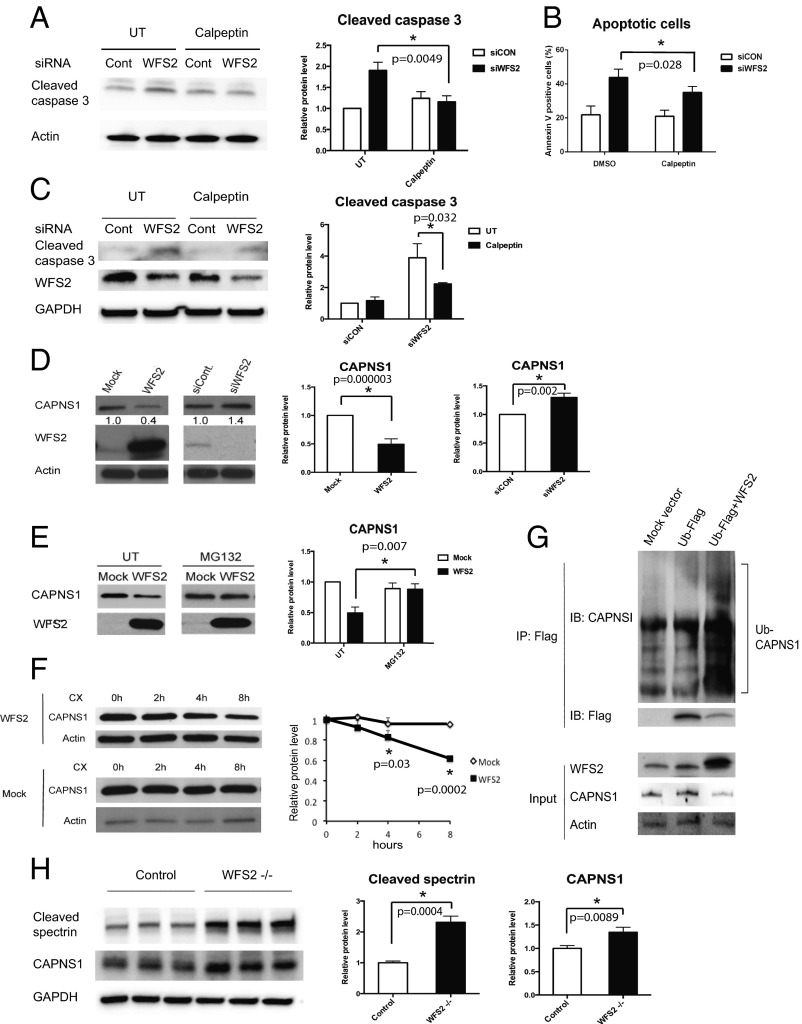

To further confirm that loss of function of WFS2 leads to cell death mediated by calpain 2, we tested if calpeptin, a calpain inhibitor, could prevent cell death in WFS2-deficient cells. In agreement with previous observations, calpeptin treatment prevented WFS2-knockdown-mediated cell death in neuronal (Fig. 3 A and B) and β cell lines (Fig. 3C and Fig. S3A). Collectively, these results indicate that WFS2 is a suppressor of calpain 2-mediated cell death.

Fig. 3.

WFS2 regulates calpain activity through CAPNS1. (A) Neuro-2a cells were transfected with siRNA against WFS2 or a control scrambled siRNA. Thirty-six h after transfection, cells were treated with or without 100µM calpeptin for 12 h. Cleaved caspase 3 and actin levels were assessed by immunoblotting (left panel). Cleaved caspase 3 protein levels are quantified in the right panel (n = 3, *P < 0.05). (B) Neuro-2a cells were transfected with siRNA against WFS2 or scrambled siRNA. Thirty-six h after transfection, cells were treated with or without 100 µM calpeptin for 12 h. Early stage apoptosis was monitored by Annexin V staining followed by flow cytometry (n = 3, *P < 0.05). (C) INS-1 832/13 cells were transfected with scrambled siRNA and WFS2 siRNA. Twenty-four h after transfection, cells were treated with or without 5 µM calpeptin for 24 h. Cleaved caspase 3, WFS2 and actin levels were monitored by immunoblotting (Left) and quantified (Right) (n = 3, *P < 0.05). (D, Left) CAPNS1, WFS2, and actin levels were assessed by immunoblotting in HEK293 cells transfected with empty expression plasmid (Mock), WFS2 expression plasmid, scrambled siRNA (siCON), or WFS2 siRNA (siWFS2). (D, Right) Protein levels of CAPNS1 are quantified (n = 5, *P < 0.05). (E) HEK293 cells were transfected with empty (Mock) or WFS2 expression plasmid, and then treated with MG132 (2 µM) or untreated (UT). Expression levels of CAPNS1 and WFS2 were measured by immunoblotting (Left) and quantified (Right) (n = 4, *P < 0.05). (F) HEK293 cells were transfected with empty or WFS2 expression plasmid, and then treated with cycloheximide (100 µM) for indicated times. (Left) Expression levels of CAPNS1 and actin were measured by immunoblotting. (Right) Band intensities corresponding to CAPNS1 in Left were quantified by Image J and plotted as relative rates of the signals at 0 h (n = 3, *P < 0.05). (G) NSC34 cells were transfected with mock empty vector, FLAG tagged ubiquitin (Ub-FLAG) plasmid or cotransfected with WFS2 expression plasmid and Ub-FLAG plasmid. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with FLAG affinity beads and analyzed for ubiquitin conjugated proteins by immunoblotting. Levels of CAPNS1 and Ub-FLAG protein were measured in the precipitates. WFS2, CAPNS1 and actin expression was monitored in the input samples. (H) Brain lysates from control and WFS2 knockout mice were analyzed by immunoblotting. Protein levels of cleaved spectrin and CAPNS1 were determined (Left) and quantified (Center and Right) (each group n = 3, *P < 0.05).

CAPN2 is the catalytic subunit of calpain 2. CAPN2 forms a heterodimer with the regulatory subunit, CAPNS1, which is required for protease activity and stability. We next explored the role of WFS2 in CAPN2 and CAPNS1 protein stability. Ectopic expression or RNAi-mediated knockdown of WFS2 did not correlate with changes in the steady-state expression of CAPN2 (Fig. S3B). By contrast, overexpression of WFS2 significantly reduced CAPNS1 protein expression (Fig. 3D) and transient suppression of WFS2 slightly increased CAPNS1 protein expression (Fig. 3D). These data suggest that WFS2 might be involved in CAPNS1 protein turnover, which is supported by the data showing that GST-tagged WFS2 expressed in HEK293 cells associated with endogenous CAPNS1 (Fig. 1C). To investigate whether WFS2 regulates CAPNS1 stability through the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, we treated HEK293 cells ectopically expressing WFS2 with a proteasome inhibitor, MG132, and then measured CAPNS1 protein level. MG132 treatment stabilized CAPNS1 protein in cells ectopically expressing WFS2 (Fig. 3E). Furthermore, we performed cycloheximide chase experiments using HEK293 cells ectopically expressing WFS2 and quantified CAPNS1 protein levels at different time points. Ectopic expression of WFS2 was associated with significantly accelerated CAPNS1 protein loss, indicating that WFS2 contributes to posttranslational regulation of CAPNS1 (Fig. 3F). To further assess whether WFS2 is involved in the ubiquitination of CAPNS1, we measured the levels of CAPNS1 ubiquitination in cells ectopically expressing WFS2 and observed that CAPNS1 ubiquitination was increased by ectopic expression of WFS2 (Fig. 3G).

To further investigate the role of WFS2 in calpain 2 regulation, we collected brain lysates from WFS2 knockout mice. Measured levels of cleaved spectrin, a well characterized substrate for calpain (26). Notably, protein expression levels of cleaved spectrin, as well as CAPNS1, were significantly increased in WFS2 knockout mice compared with control mice (Fig. 3H). Collectively, these results indicate that WFS2 inhibits calpain 2 activation by regulating CAPNS1 degradation mediated by the ubiquitin-proteasome system.

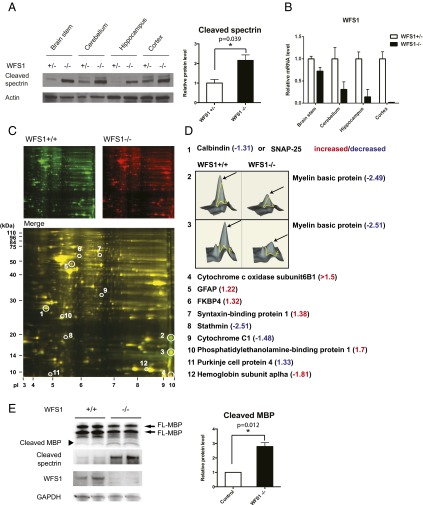

Calpain 2 is a calcium-dependent protease. WFS1, the other causative gene for Wolfram syndrome, has been shown to be involved in calcium homeostasis (27, 28), suggesting that the loss of function of WFS1 may also cause calpain activation. To evaluate this possibility, we measured calpain activation levels in brain tissues from WFS1 brain-specific knockout and control mice. We observed a significant increase in a calpain-specific spectrin cleavage product, reflecting higher calpain activation levels in WFS1 knockout mice compared with control mice (Fig. 4A). The suppression levels of WFS1 in different parts of the brain were shown in Fig. 4B. To further confirm that calpain is activated by the loss of WFS1, we looked for other calpain substrates in brain tissues from WFS1 knockout mice using a proteomics approach. Two-dimensional fluorescence gel electrophoresis identified 12 proteins differentially expressed between cerebellums of WFS1 knockout mice and those of control mice (Fig. 4 C and D). Among these, myelin basic protein (MBP) is a known substrate for calpain in the brain (29). We measured myelin basic protein levels in brain lysates from WFS1 knockout and control mice. Indeed, the cleavage and degradation of myelin basic protein was increased in WFS1 knockout mice relative to control mice (Fig. 4E).

Fig. 4.

Evidence of Calpain 2 activation in a mouse model of Wolfram syndrome. (A) Protein was extracted from brain tissues of WFS1 brain-specific knockout (−/−) and control (+/−) mice. (Left) Cleaved alpha II spectrin and actin levels were determined by immunoblot analysis. (Right) Quantification of cleaved spectrin is shown (each group n = 10, *P < 0.05). (B) WFS1 mRNA levels in different parts of brain in WFS1−/− and WFS1+/− mice were measured by qRT-PCR. (C) Two-dimensional fluorescence difference gel electrophoresis of cerebellum proteins from WFS1 knockout (WFS1−/−, labeled in red) and control (WFS1+/+, labeled in green) mice showing common (Merge, labeled in yellow) and unique proteins (circled). (D) The protein expression ratios between WFS1 knockout and control mice were generated, and differentially expressed spots were analyzed by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. Quantitative diagrams of spots #2 and #3, identified by mass spectrometry as myelin basic protein, showing lower levels of expression in WFS1 knockout mice compared with control mice. (E) Protein was extracted from cerebellums of WFS1 brain-specific knockout (−/−) and control (+/+) mice. Cleaved myelin basic protein (black arrow), cleaved spectrin, WFS1 and GAPDH levels were determined by immunoblot analysis (left panel) and quantified in the right panel (each group n = 3, *P < 0.05).

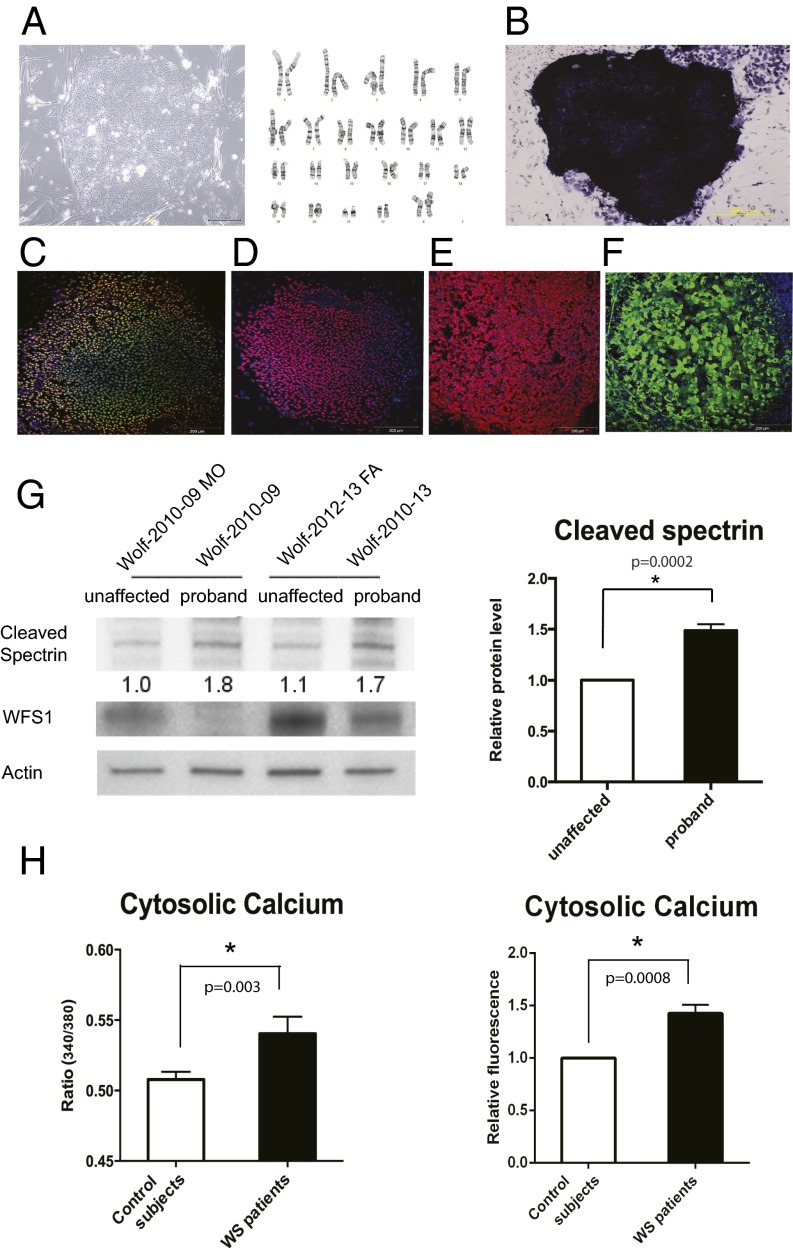

Next, we looked for evidence of increased calpain activity in Wolfram syndrome patient cells. We created neural progenitor cells derived from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) of Wolfram syndrome patients with mutations in WFS1. Fibroblasts from four unaffected controls and five patients with Wolfram syndrome were transduced with four reprogramming genes (Sox2, Oct4, c-Myc, and Klf4) (30) (Table S2). We produced at least 10 iPSC clones from each control and Wolfram patient. All control- and Wolfram-iPSCs, exhibited characteristic human embryonic stem cell morphology, expressed pluripotency markers including ALP, NANOG, SOX2, SSEA4, TRA-1–81, and had a normal karyotype (Fig. 5 A–F). To create neural progenitor cells, we first formed neural aggregates from iPSCs. Neural aggregates were harvested at day 5, replated onto new plates to give rise to colonies containing neural rosette structures. At day 12, neural rosette clusters were collected, replated, and used as neural progenitor cells. Consistent with the data from WFS1 and WFS2 knockout mice, we observed that spectrin cleavage was increased in neural progenitor cells derived from Wolfram-iPSCs relative to control iPSCs, which indicates increased calpain activity (Fig. 5G).

Fig. 5.

High cytosolic calcium levels and hyperactivation of calpain in patient neural progenitor cells. (A, Left) Wolfram syndrome iPS cells derived from fibroblasts of a patient 1610. (A, Right) Karyotype of the Wolfram iPS cells. (B) Alkaline phosphatase staining of the Wolfram iPS cells. (C–F) Wolfram syndrome iPS cells stained with pluripotent markers: Nanog (C), Sox2 (D), SSEA4 (E), and TRA-1 (F). (G) Immunoblot analysis of cleaved spectrin and actin in neural progenitor cells derived from Wolfram syndrome patient iPS cells. The relative levels of the spectrin cleavage product are indicated (Left) and quantified (Right) (n = 4, *P < 0.05). (H, Left) Quantitative analysis of cytosolic calcium levels in unaffected controls and Wolfram syndrome patients measured by Fura-2 calcium indicator (All values are means ± SEM; experiment was performed six independent times with >3 wells per sample each time; n = 6, *P < 0.05). (H, Right) Quantification of cytosolic calcium levels in unaffected controls and Wolfram syndrome patients measured by Fluo-4 calcium assay (experiment was performed four independent times; n = 4, *P < 0.05).

Because calpain is known to be activated by high calcium, we explored the possibility that cytoplasmic calcium may be increased in patient cells by staining neural progenitor cells derived from control- and Wolfram-iPSCs with Fura-2, a fluorescent calcium indicator which enables accurate measurements of cytoplasmic calcium concentrations. Fig. 5H, Left, shows that cytoplasmic calcium levels were higher in Wolfram-iPSC-derived neuronal cells relative to control cells. This result was confirmed by staining these cells with another fluorescent calcium indicator, Fluo-4 (Fig. 5H, Right). Collectively, these results indicate that loss of function of WFS1 increases cytoplasmic calcium levels, leading to calpain activation.

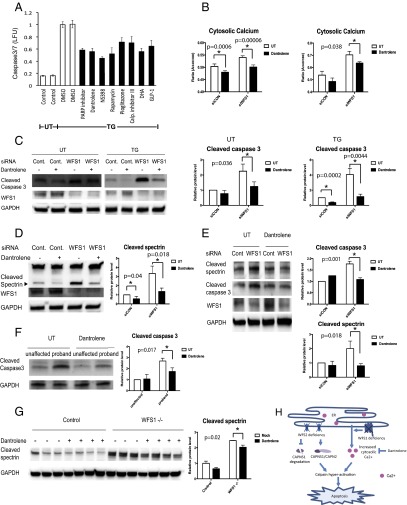

The results shown above argue that the pathway leading to calpain activation provides potential therapeutic targets for Wolfram syndrome. To test this concept, we elected to focus on modulating cytosolic calcium and performed a small-scale screen to identify chemical compounds that could prevent cell death mediated by thapsigargin, a known inhibitor for ER calcium ATPase. Among 73 well characterized chemical compounds that we tested (Table S3), 8 could significantly suppress thapsigargin-mediated cell death. These were PARP inhibitor, dantrolene, NS398, pioglitazone, calpain inhibitor III, docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), rapamycin, and GLP-1 (Fig. 6A). GLP-1, pioglitazone, and rapamycin are FDA-approved drugs and have been shown to confer protection against ER stress-mediated cell death (27, 31–33). Dantrolene is another FDA-approved drug clinically used for muscle spasticity and malignant hyperthermia (34). Previous studies have shown that dantrolene is an inhibitor of the ER-localized ryanodine receptors and suppresses leakage of calcium from the ER to cytosol (35, 36). We thus hypothesized that dantrolene could confer protection against cell death in Wolfram syndrome, and performed a series of experiments to investigate this possibility. We first examined whether dantrolene could decrease cytoplasmic calcium levels. As expected, dantrolene treatment decreased cytosolic calcium levels in INS-1 832/13 and NSC34 cells (Fig. S4 A and B). We next asked whether dantrolene could restore cytosolic calcium levels in WFS1-deficient cells. RNAi-mediated WFS1 knockdown increased cytosolic calcium levels relative to control cells, and dantrolene treatment restored cytosolic calcium levels in WFS1-knockdown INS-1 832/13 cells (Fig. 6B, Left) as well as WFS1-knockdown NSC34 cells (Fig. 6B, Right). Next, to determine whether dantrolene confered protection in WFS1-deficient cells, we treated WFS1 silenced INS-1 832/13 cells with dantrolene and observed suppression of apoptosis (Fig. 6C) and calpain activity (Fig. 6D). Dantrolene treatment also prevented calpain activation and cell death in WFS1-knockdown NSC34 cells (Fig. 6E). To verify these observations in patient cells, we pretreated neural progenitor cells derived from iPSCs of a Wolfram syndrome patient and an unaffected parent with dantrolene, and then challenged these cells with thapisgargin. Thapsigargin-induced cell death was increased in neural progenitor cells derived from the Wolfram syndrome patient relative to those derived from the unaffected parent, and dantrolene could prevent cell death in the patient iPSC-derived neural progenitor cells (Fig. 6F). In addition, we treated brain-specific WFS1 knockout mice with dantrolene and observed evidence of suppressed calpain activation in brain lysates from these mice (Fig. 6G). Collectively, these results argue that dantrolene could prevent cell death in Wolfram syndrome by suppressing calpain activation.

Fig. 6.

Dantrolene prevents cell death in iPS cell-derived neural progenitor cells of Wolfram syndorme by inhibiting the ER calcium leakage to the cytosol. (A) INS-1 832/13 cells were pretreated with DMSO or drugs for 24 h then incubated in media containing 20 nM of thapsigargin (TG) overnight. Apoptosis was detected by caspase 3/7-Glo luminescence. (B) Cytosolic calcium levels were determined by Fura-2 in control and WFS1-deficient INS-1 832/13 (Left) and NSC34 (Right) cells treated or untreated with 10 µM dantrolene for 24 h (All values are means ± SEM; experiment was performed 6 independent times with >3 wells per sample each time n = 6, *P < 0.05). (C) INS-1 832/13 cells were transfected with scrambled siRNA or siRNA against WFS1. Cells were pretreated with or without 10 µM dantrolene for 48 h, then incubated in media with or without 0.5 µM TG for 6 h. Expression levels of cleaved caspase-3, WFS1, GAPDH were measured by immunoblotting (Left). Protein levels of caspase3 under untreated (Center) and TG treated (Right) conditions are quantified and shown as bar graphs (n = 3, *P < 0.05). (D) INS-1 832/13 cells were transfected with scrambled siRNA or siRNA against WFS1, pretreated with or without 10 µM dantrolene for 48 h, then incubated in media containing 0.5 µM TG for 6 h. Protein levels of cleaved spectrin, WFS1, GAPDH were analyzed by immunoblotting (Left) and quantified (Right) (n = 3, *P < 0.05). (E) NSC34 cells were transfected with scrambled siRNA or siRNA against WFS1. Then treated with or without10 µM dantrolene for 24 h. Protein levels of cleaved spectrin, cleaved caspase 3, WFS2 and GAPDH were determined by immunoblotting (Left) and quantified (Right) (n = 3, *P < 0.05). (F) Wolfram patient neural progenitor cells were pretreated with or without 10 µM dantrolene for 48 h. Then, cells were treated with 0.125 µM TG for 20 h. (Left) Apoptosis was monitored by immunoblotting. (Right) Quantification of cleaved caspase 3 protein levels are indicated (n = 3, *P < 0.05). (G) Control and WFS1 brain-specific knockout mice were treated with water or dantrolene for 4 wk at 20 mg/kg. Brain lysates of these mice were examined by immunoblotting. Protein levels of cleaved spectrin and GAPDH were monitored (Left) and quantified (Right) (All values are means ± SEM; each group n > 3, *P < 0.05). (H) Scheme of the pathogenesis of Wolfram syndrome.

Discussion

Growing evidence indicates that ER dysfunction triggers a range of human chronic diseases, including diabetes, atherosclerosis, inflammatory bowel disease, and neurodegenerative diseases (3, 4, 37–39). However, currently there is no effective therapy targeting the ER for such diseases due to the lack of clear understanding of the ER’s contribution to the pathogenesis of these diseases. Although Wolfram syndrome is a rare disease and therefore not a focus of drug discovery efforts, the homogeneity of the patient population and disease mechanism has enabled us to identify a potential target, a calcium-dependent protease, calpain. Our results provide new insights into how the pathways leading to calpain activation cause β cell death and neurodegeneration, which are schematically summarized in Fig. 6H.

There are two causative genes for Wolfram syndrome, WFS1 and WFS2. The functions of WFS1 have been extensively studied in pancreatic β cells. It has been shown that WFS1-deficient pancreatic β cells have high baseline ER stress levels and impaired insulin synthesis and secretion. Thus, WFS1-deficient β cells are susceptible to ER stress mediated cell death (5, 6, 32, 40–42). The functions of WFS2 are still not clear. There is evidence showing that impairment of WFS2 function can cause neural atrophy, muscular atrophy, and accelerate aging in mice (14). WFS2 has also been shown to be involved in autophagy (43). However, although patients with both genetic types of Wolfram syndrome suffer from the same disease manifestations, it was not clear if a common molecular pathway was altered in these patients. Our study has demonstrated, to our knowledge for the first time, that calpain hyperactivation is the common molecular pathway altered in patients with Wolfram syndrome. The mechanisms of calpain hyperactivation are different in the two genetic types of Wolfram syndrome. WFS1 mutations cause calpain activation by increasing cytosolic calcium levels, whereas WFS2 mutations lead to calpain activation due to impaired calpain inhibition.

Previously, Wolfram syndrome studies focused on pancreatic β cell function (5, 40, 41). However, patients also suffer from neuronal manifestations. MRI scans of Wolfram syndrome patients showed atrophy in brain tissue implying neurodegeneration in patients (7, 10). To investigate the mechanisms of neurodegeneration in Wolfram syndrome human cells, we established Wolfram syndrome iPSC-derived neural progenitor lines and confirmed the observations found in rodent cells and animal models of Wolfram syndrome. Differentiation of these iPSC-derived neural progenitor cells into specific types of neurons should be carried out in the future to better understand which cell types are damaged in Wolfram syndrome; this will lead to a better understanding of the molecular basis of this disease and provide cell models for future drug development.

Calpain activation has been found to be associated with type 2 diabetes and various neuronal diseases including Alzheimers, traumatic brain injury and cerebral ischemia, suggesting that regulation of calpains is crucial for cellular health (23). We discovered that calpain inhibitor III could confer protection against thapsigargin mediated cell death (Fig. 6A). Our data also demonstrates that calpeptin treatment was beneficial for cells with impaired WFS2 function. These results suggest that targeting calpain could be a novel therapeutic strategy for Wolfram syndrome. However, calpain is also an essential molecule for cell survival (44). Controlling calpain activation level is a double-bladed sword. We should carefully monitor calpain functions in treating patients with Wolfram syndrome (44).

Calpain activation is tightly regulated by cytosolic calcium levels. In other syndromes that increase cytosolic calcium level in pancreatic β cells, patients experience a transient or permanent period of hyperinsulinaemic hypoglycemia. This hyperinsulinaemic hypoglycemia can be partially restored by an inhibitor for ATP-sensitive potassium (KATP) channels or a calcium channel antagonist that prevents an increase in cytosolic calcium levels (45, 46). Although patients with Wolfram syndrome do not experience a period of hyperinsulinaemic hypoglycemia, small molecule compounds capable of altering cellular calcium levels may prevent calpain 2 activation and hold promise for treating patients with Wolfram syndrome. Treatment of WFS1-knockdown cells with dantrolene and ryanodine could prevent cell death mediated by WFS1 knockdown. Dantrolene is a muscle relaxant drug prescribed for multiple sclerosis, cerebral palsy or malignant hyperthermia (47). Dantrolene inhibits the ryanodine receptors and reduces calcium leakage from the ER to cytosol, lowering cytosolic calcium level. The protective effect of dantrolene treatment on WFS1-deficient cells suggests that dysregulated cellular calcium homeostasis plays a role in the disease progression of Wolfram syndrome. In addition, it has been shown that stabilizing ER calcium channel function could prevent the progression of neurodegeneration in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease (48). Therefore, modulating calcium levels may be an effective way to treat Wolfram syndrome or other ER diseases.

Dantrolene treatment did not block cell death mediated by WFS2 knockdown, suggesting that WFS2 does not directly affect the ER calcium homeostasis (Fig. S4 D and E). RNAi-mediated WFS1 knockdown in HEK293 cells significantly reduced the activation levels of sarco/endoplasmic reticulum calcium transport ATPase (SERCA), indicating that WFS1 may play a role in the modulation of SERCA activation and ER calcium levels (Fig. S5). It has been shown that WFS1 interacts with the Na+/K+ATPase β1 subunit and the expression of WFS1 parallels that of Na+/K+ ATPase β1 subunit in a variety of settings, suggesting that WFS1 may function as an ion channel or regulator of existing channels (42). Further studies on this topic would be necessary to completely understand the etiology of Wolfram syndrome.

Our study reveals that dantrolene can prevent ER stress-mediated cell death in human and rodent cell models as well as mouse models of Wolfram syndrome. Thus, dantrolene and other drugs that regulate ER calcium homeostasis could be used to delay the progression of Wolfram syndrome and other diseases associated with ER dysfunction, including type 1 and type 2 diabetes.

Materials and Methods

Human Subjects.

Wolfram syndrome patients were recruited through the Washington University Wolfram Syndrome International Registry website (wolframsyndrome.dom.wustl.edu). The clinic protocol was approved by the Washington University Human Research Protection Office and all subjects provided informed consent if adults and assent with consent by parents if minor children (IRB ID 201107067 and 201104010).

Animal Experiments.

WFS1 brain-specific knockout mice were generated by breeding the Nestin-Cre transgenic mice (Jackson Laboratory) with WFS1 floxed mice (40). WFS2 whole body knockout mice are purchased from MRC Harwell. All animal experiments were performed according to procedures approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Washington University School of Medicine (A-3381-01).

Calcium Levels.

Calcium levels in cells were measured by Fura-2 AM dye and Fluo-4 AM dye (Life Technology) Inifinite M1000 (Tecan). Cells were plated in 96-well plates at 25,000 cells per well and stained with 4 μg/mL Fura-2 dye along with 2.5 mM probenecid for 30 min, then the cells were washed with PBS and kept in the dark for another 30 min to allow cleavage of AM ester. Fluorescence was measured at excitation wavelength 510 nm and emission wavelengths 340 nm and 380 nm. Then background subtractions were performed with both emission wavelengths. The subtraction result was used to calculate 340/380 ratios.

For Fluo-4 AM staining, neural progenitor cells were plated in 24-well plates at 200,000 cells per well. After staining with Fluo-4 AM dye for 30 min along with 2.5 mM probenecid, cells were washed and resuspended in PBS. Incubation for a further 30 min was performed to allow complete deesterification of intracellular AM esters. Then, samples were measured by flow cytometry at the FACS core facility of Washington University School of Medicine using a LSRII instrument (BD). The results were analyzed by FlowJo ver.7.6.3.

Statistical Analysis.

Two-tailed t tests were used to compare the two treatments. P values below 0.05 were considered significant. All values are shown as means ± SD if not stated. Please see SI Materials and Methods for complete details.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank all of the participants in the Washington University Wolfram Registry and Clinic and their families for their time and effort (wolframsyndrome.dom.wustl.edu/). We also thank Mai Kanekura, Mariko Hara, and Karen Sargent for technical support and the Washington University Wolfram Study Group Members and the study staff for advice and support in the greater research program. This work was supported by NIH Grants DK067493, P60 DK020579, and UL1 TR000448; Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation Grants 47-2012-760 and 17-2013-512; American Diabetes Association Grant 1-12-CT-61, the Team Alejandro, The Team Ian, the Ellie White Foundation for Rare Genetic Disorders, and the Jack and J. T. Snow Scientific Research Foundation (F.U.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1421055111/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Ron D, Walter P. Signal integration in the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8(7):519–529. doi: 10.1038/nrm2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tabas I, Ron D. Integrating the mechanisms of apoptosis induced by endoplasmic reticulum stress. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13(3):184–190. doi: 10.1038/ncb0311-184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hetz C, Chevet E, Harding HP. Targeting the unfolded protein response in disease. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12(9):703–719. doi: 10.1038/nrd3976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang S, Kaufman RJ. The impact of the unfolded protein response on human disease. J Cell Biol. 2012;197(7):857–867. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201110131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fonseca SG, et al. WFS1 is a novel component of the unfolded protein response and maintains homeostasis of the endoplasmic reticulum in pancreatic beta-cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(47):39609–39615. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507426200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fonseca SG, et al. Wolfram syndrome 1 gene negatively regulates ER stress signaling in rodent and human cells. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(3):744–755. doi: 10.1172/JCI39678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barrett TG, Bundey SE, Macleod AF. Neurodegeneration and diabetes: UK nationwide study of Wolfram (DIDMOAD) syndrome. Lancet. 1995;346(8988):1458–1463. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)92473-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wolfram DJ, Wagener HP. Diabetes mellitus and simple optic atrophy among siblings: Report of four cases. Mayo Clin Proc. 1938;1:715–718. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Urano F. Diabetes: Targeting endoplasmic reticulum to combat juvenile diabetes. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2014;10(3):129–130. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2013.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hershey T, et al. Washington University Wolfram Study Group Early brain vulnerability in Wolfram syndrome. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(7):e40604. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marshall BA, et al. Washington University Wolfram Study Group Phenotypic characteristics of early Wolfram syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8(1):64. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-8-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inoue H, et al. A gene encoding a transmembrane protein is mutated in patients with diabetes mellitus and optic atrophy (Wolfram syndrome) Nat Genet. 1998;20(2):143–148. doi: 10.1038/2441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amr S, et al. A homozygous mutation in a novel zinc-finger protein, ERIS, is responsible for Wolfram syndrome 2. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81(4):673–683. doi: 10.1086/520961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen YF, et al. Cisd2 deficiency drives premature aging and causes mitochondria-mediated defects in mice. Genes Dev. 2009;23(10):1183–1194. doi: 10.1101/gad.1779509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wiley SE, et al. Wolfram Syndrome protein, Miner1, regulates sulphydryl redox status, the unfolded protein response, and Ca2+ homeostasis. EMBO Mol Med. 2013;5(6):904–918. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201201429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shang L, et al. β-cell dysfunction due to increased ER stress in a stem cell model of Wolfram syndrome. Diabetes. 2014;63(3):923–933. doi: 10.2337/db13-0717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sandhu MS, et al. Common variants in WFS1 confer risk of type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2007;39(8):951–953. doi: 10.1038/ng2067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bonnycastle LL, et al. Autosomal dominant diabetes arising from a Wolfram syndrome 1 mutation. Diabetes. 2013;62(11):3943–3950. doi: 10.2337/db13-0571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goll DE, Thompson VF, Li H, Wei W, Cong J. The calpain system. Physiol Rev. 2003;83(3):731–801. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00029.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tan Y, et al. Ubiquitous calpains promote caspase-12 and JNK activation during endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(23):16016–16024. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601299200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tan Y, Wu C, De Veyra T, Greer PA. Ubiquitous calpains promote both apoptosis and survival signals in response to different cell death stimuli. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(26):17689–17698. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601978200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakagawa T, Yuan J. Cross-talk between two cysteine protease families. Activation of caspase-12 by calpain in apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 2000;150(4):887–894. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.4.887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cui W, et al. Free fatty acid induces endoplasmic reticulum stress and apoptosis of β-cells by Ca2+/calpain-2 pathways. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(3):e59921. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang CJ, et al. Calcium-activated calpain-2 is a mediator of beta cell dysfunction and apoptosis in type 2 diabetes. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(1):339–348. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.024190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barrett TG, Bundey SE. Wolfram (DIDMOAD) syndrome. J Med Genet. 1997;34(10):838–841. doi: 10.1136/jmg.34.10.838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu MC, et al. Comparing calpain- and caspase-3-mediated degradation patterns in traumatic brain injury by differential proteome analysis. Biochem J. 2006;394(Pt 3):715–725. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hara T, et al. Calcium efflux from the endoplasmic reticulum leads to β-cell death. Endocrinology. 2014;155(3):758–768. doi: 10.1210/en.2013-1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takei D, et al. WFS1 protein modulates the free Ca(2+) concentration in the endoplasmic reticulum. FEBS Lett. 2006;580(24):5635–5640. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu MC, et al. Extensive degradation of myelin basic protein isoforms by calpain following traumatic brain injury. J Neurochem. 2006;98(3):700–712. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03882.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126(4):663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yusta B, et al. GLP-1 receptor activation improves beta cell function and survival following induction of endoplasmic reticulum stress. Cell Metab. 2006;4(5):391–406. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Akiyama M, et al. Increased insulin demand promotes while pioglitazone prevents pancreatic beta cell apoptosis in Wfs1 knockout mice. Diabetologia. 2009;52(4):653–663. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1270-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bachar-Wikstrom E, et al. Stimulation of autophagy improves endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced diabetes. Diabetes. 2013;62(4):1227–1237. doi: 10.2337/db12-1474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dykes MH. Evaluation of a muscle relaxant: Dantrolene sodium (Dantrium) JAMA. 1975;231(8):862–864. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wei H, Perry DC. Dantrolene is cytoprotective in two models of neuronal cell death. J Neurochem. 1996;67(6):2390–2398. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.67062390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Luciani DS, et al. Roles of IP3R and RyR Ca2+ channels in endoplasmic reticulum stress and beta-cell death. Diabetes. 2009;58(2):422–432. doi: 10.2337/db07-1762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hotamisligil GS. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and atherosclerosis. Nat Med. 2010;16(4):396–399. doi: 10.1038/nm0410-396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hotamisligil GS. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and the inflammatory basis of metabolic disease. Cell. 2010;140(6):900–917. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ozcan L, Tabas I. Role of endoplasmic reticulum stress in metabolic disease and other disorders. Annu Rev Med. 2012;63:317–328. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-043010-144749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Riggs AC, et al. Mice conditionally lacking the Wolfram gene in pancreatic islet beta cells exhibit diabetes as a result of enhanced endoplasmic reticulum stress and apoptosis. Diabetologia. 2005;48(11):2313–2321. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-1947-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ishihara H, et al. Disruption of the WFS1 gene in mice causes progressive beta-cell loss and impaired stimulus-secretion coupling in insulin secretion. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13(11):1159–1170. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zatyka M, et al. Sodium-potassium ATPase 1 subunit is a molecular partner of Wolframin, an endoplasmic reticulum protein involved in ER stress. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17(2):190–200. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chang NC, Nguyen M, Germain M, Shore GC. Antagonism of Beclin 1-dependent autophagy by BCL-2 at the endoplasmic reticulum requires NAF-1. EMBO J. 2010;29(3):606–618. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dutt P, et al. m-Calpain is required for preimplantation embryonic development in mice. BMC Dev Biol. 2006;6:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-6-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arya VB, Mohammed Z, Blankenstein O, De Lonlay P, Hussain K. Hyperinsulinaemic hypoglycaemia. Hormone Metabolic Res. 2014;46(3):157–170. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1367063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shah P, Demirbilek H, Hussain K. Persistent hyperinsulinaemic hypoglycaemia in infancy. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2014;23(2):76–82. doi: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2014.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Krause T, Gerbershagen MU, Fiege M, Weisshorn R, Wappler F. Dantrolene—a review of its pharmacology, therapeutic use and new developments. Anaesthesia. 2004;59(4):364–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2004.03658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chakroborty S, et al. Stabilizing ER Ca2+ channel function as an early preventative strategy for Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(12):e52056. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.