Abstract

Aedes aegypti has already been implicated in the emergence of dengue and chikungunya viruses in the southern US. Vector competence is the ability of a mosquito species to support transmission of an arbovirus, which is bounded by its ability to support replication and dissemination of the virus through the mosquito body to the salivary glands to be expectorated in the saliva at the time of feeding on a vertebrate host. Here, we investigate the vector competence of A. aegypti for the arbovirus koutango by orally challenging mosquitoes with two titers of virus. We calculated the effective vector competence, a cumulative measure of transmission capability weighted by mosquito survival, and determined that A. aegypti was competent at the higher dose only. We conclude that further investigation is needed to determine the infectiousness of vertebrate hosts to fully assess the emergence potential of this virus in areas rich in A. aegypti.

Keywords: arbovirus, transmission, vector-borne virus, koutango, vector competence, extrinsic incubation period

Introduction

Aedes aegypti mosquitoes originated from Africa but are now found in tropical regions around the world.1,2 Urbanization particularly has contributed to the increase of Aedes mosquito populations, especially A. aegypti and Aedes albopictus.1,2 There has been a threefold increase in urban human population densities in Africa since the 1950s, and even larger increases have occurred in Asia and the Americas.3 With the related increase in contact between urban-associated Aedes mosquito populations, arboviruses, especially dengue virus (DENV), have established endemic transmission in these areas.4

A. aegypti is found in the subtropical region of the United States and in popular tropical tourist destinations, and has been implicated in the recent chikungunya (CHIKV) outbreak in the Caribbean resulting in over 100 imported and several locally acquired cases in the US.5–7 Furthermore, A. aegypti has been implicated as the primary vector of DENV in the southern United States.8 A. aegypti are primarily anthrophillic, preferring to bite humans than other potential hosts, and have adapted their behavior and ecology to maximize contact with humans.9 For instance, they tend to be closely associated with human domiciles and breed in (often man-made) containers near houses.9,10

Koutango virus (KOUTV) was first isolated in 1968 in Somalia, and it has been suggested that this virus is a variant of West Nile virus (WNV).11–14 However, species of the main vector genus of WNV (Culex spp.) were not found to be competent for KOUTV,13 indicating that questions regarding the transmission cycle of this virus remain. Early observations of transovarial transmission of KOUTV and subsequent competence of emerged A. aegypti females suggest this as a potential vector in the transmission cycle as a real possibility15 and transmission of KOUTV by A. aegypti viruses has been observed.15 However, recent studies involving KOUTV have not focused on the mosquito, and there are still some questions regarding the potential transmission dynamics of this virus. To address this, we experimentally investigated the dynamics of KOUTV infectivity to the mosquito A. aegypti and determined the effective vector competence (EVC)16 to characterize the threat this virus poses in areas where A. aegypti is present, such as in the southern United States.

Materials and Methods

Vector competence

Virus

The KOUTV strain utilized in this experiment was the KOUTV DAK Ar D 5443 received from Robert B. Tesh (CBEID-UTMB). Virus was propagated by inoculating 100 μL of viral stock into the T-75 flask of confluent Vero cells. To determine titer, a plaque assay was developed and standard curves created for quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) as previously described.16 Briefly, we utilized a SuperScript III One-step qRT-PCR kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) with the primers and probes given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primers and probe sequences.

| FORWARD PRIMER SEQUENCE | REVERSE PRIMER SEQUENCE | PROBE SEQUENCE |

|---|---|---|

| ACCAGGAGGCAAGA TTTACG |

CGCTTTGGTTATC CGTGTG |

ACAAGAGGCAAGATTTACGCAGACCGCT GGCTGGGACACACGGATAACCAAGCG |

Notes: The sequences for the primers and probe used to amplify KOUTV and CHIKV are given. All sequences are 5′ → 3′.

The presence of KOUTV viral RNA was detected via qRT-PCR using the following protocol: RT step (1 cycle) 48° C for 2 minutes and 95 °C for 2 minutes, amplification and data recording step (40 cycles) 95 °C for 15 seconds and 60 °C for 30 seconds. Primers were designed and obtained via Integrated DNA technologies with 5′-FAM fluorophore and 3′-Black-Hole quencher. Prior to offering virus to mosquitoes, virus was propagated into Vero cells. Viral standard curves and concentrations were obtained via plaque assay as described previously before the beginning of the experiment.16

Mosquito Exposure and Detection of Disseminated Infection

A. aegypti (Linnaeus, 1762) Rockefeller strain were reared from the colony at Louisiana State University School of Veterinary Medicine. Mosquitoes were orally exposed to an artificial bloodmeal 3–5 days post emergence with 109 plaque forming units (PFU)/mL or 106 PFU/mL. Feeding occurred as previously described.16 Briefly, mosquitoes were reared and maintained at constant environmental parameters of 28 °C, 75–80% humidity, and a 16:8 light:dark photoperiod.16 Mosquitoes were then orally challenged using the Hemoteck ((Discovery Workshops, Arrington, Lanceshire, UK) as in Supernatant from virus-infected cell culture was mixed with bovine blood (Hemostat, Dixon, CA) at a ratio of 2:1 and viral titers verified by qRT-PCR as in.16

After feeding, fully engorged females were placed into clean cartons and then sampled at days 3, 5, 7 and 11 post exposure (dpe) to test for dissemination status. It has been previously shown that detectable arbovirus in the legs is indicative of a fully disseminated infection; thus the salivary glands are presumed to be infected as well.17 Mosquito legs were removed and analyzed separately for infection from the bodies as previously described.16,18–21 RNA was extracted using the MagMax-96 kit (Ambion) on a King Fisher® nucleic acid extraction instrument according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Thermo Scientific). After extraction, the samples were tested for the presence of dengue viral RNA via qRT-PCR using the following protocol: RT step (1 cycle) 48 °C for 2 minutes and 95 °C for 5 minutes; amplification and data recording step (40 cycles) 95 °C for 15 seconds and 60 °C for 30 seconds.

Data analysis

Vector competence was calculated as the number of disseminated infections divided by the total number of mosquitoes that fed to repletion (number exposed), EVC was calculated as in Ref. 16. All analyses and modeling was performed in R (version 3.0.1). EVC is a cumulative measure of vector competence over a range of days, bounded and weighted by the mosquito lifespan. Briefly, define the rate of change of vector competence over days as b(N):

where β1 = rate of change of vector competence over time. EVC, represented by the phi (ϕ) is then given by:

where N is the extrinsic incubation period, here a range of days defined by the study duration; b(N) is as above; and P = probability of daily survival. This is held constant so as to isolate the viral phenotypes and assess relative fitness.16 EVC gives a measure of viral fitness while entomological and vertebrate density parameters are held.

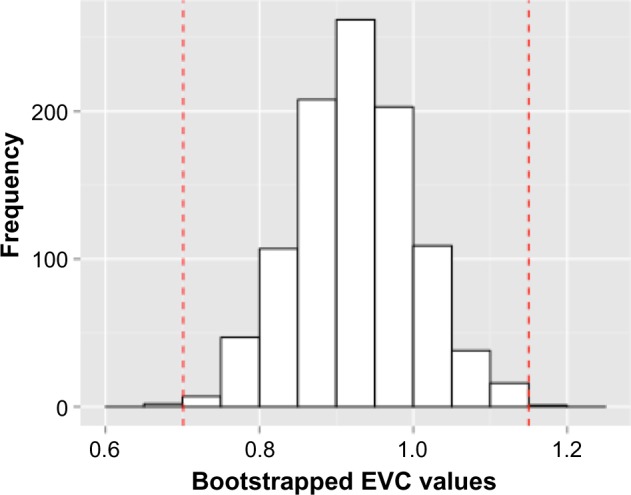

To obtain 95% confidence intervals (CIs), we employed a bootstrapping method as in Ref. 16. Per day of study, the number of mosquitoes with disseminated infections was coded as 1 and those without as 0. We then resampled (with replacement) for n = 1000 iterations for a bootstrapped distribution of dissemination rates (for each set of N study days). The b(N) was then calculated for each 1000 sets of dissemination over N days. EVC (ϕ) was calculated for each set of replicated data and the distribution of bootstrapped ϕ was obtained (Fig. 1), from which we obtained the 95% CI.

Figure 1.

Histogram of bootstrapped EVC values. The bootstrapped distribution of KOUTV EVC values from 1000 simulations demonstrates how the 95% CI is determined.

Results

KOUTV vector competence

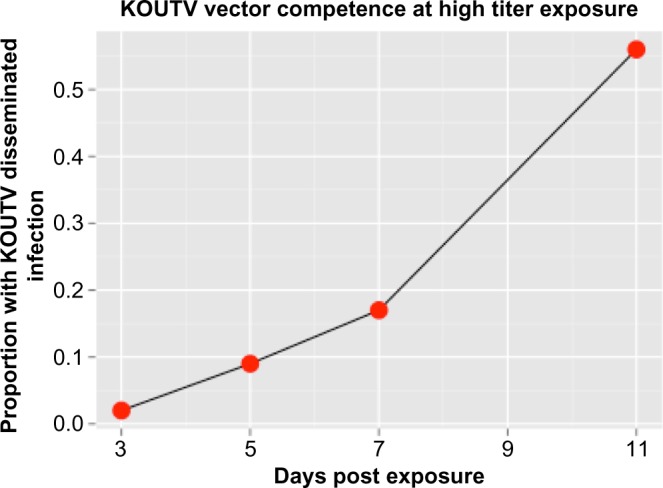

No mosquitoes had a disseminated infection after exposure to 106 PFU/mL, indicating that at this titer, A. aegypti are not competent for KOUTV. However, the higher KOUTV titer exposure resulted in disseminated infections as early as 3 days post exposure (Table 2). The dissemination rates were calculated as 2.22%, 8.51%, 17.24%, and 55.56% on 3, 5, 7, and 11 days post exposure, respectively (Fig. 2).

Table 2.

A. aegypti vector competence for KOUTV.

| DAYS POST EXPOSURE | LEGS | TOTAL TESTED | |

|---|---|---|---|

| UNINFECTED | INFECTED | ||

| 3 | 44 | 1 | 45 |

| 5 | 43 | 4 | 47 |

| 7 | 24 | 5 | 29 |

| 11 | 15 | 21 | 36 |

| Total | 153 | 34 | 187 |

Note: Proportion of mosquitoes with uninfected or infected legs after oral challenge with 109 PFU/mL on 3, 5, 7, and 11 days post exposure.

Figure 2.

A. aegypti vector competence for KOUTV. Dissemination rates of high-dose (109) KOUTV in A. aegypti at 3, 5, 7, and 11 days post exposure.

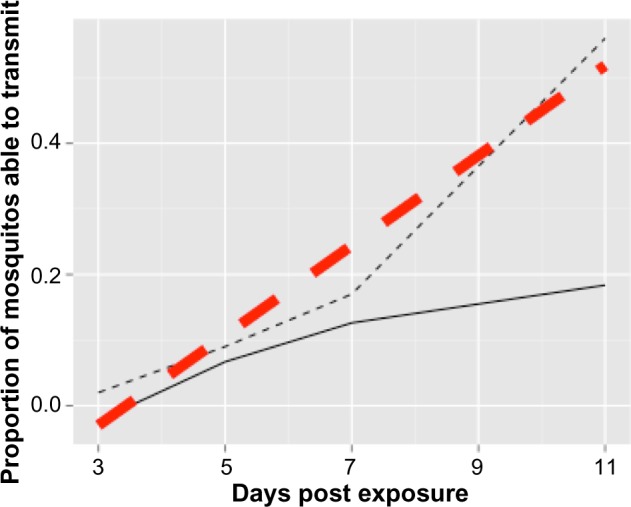

The calculated EVC of KOUTV was 857 indicating that 85.7% of mosquitoes achieved a disseminated infection and were still alive at the end of the 11-day period of the study. The calculated 95% CI of KOUTV EVC was [0.701,1.15]. For interpretative purposes, the upper confidence limit (UCL) is asymptomatically bounded by 1, because proportion has a range [0,1]. However, the function of ϕ is not based on a probability density function and thus mathematically has no upper asymptote; therefore, the mathematical 97.5% quantile may exceed 1 as it did here (Fig. 2). Figure 3 shows the relationship among the raw data, the b(N) for the data, and the curve resulting from weighting b(N) by the mortality rate of the mosquito vector.

Figure 3.

Relationship among the raw data, the b(N) for the data, and the curve resulting from weighting b(N) by the mortality rate of the mosquito vector. The raw data (thinner, black dotted line) connect the points experimentally determined at days 3, 5, 7, and 11 days post exposure, while the b(N) (thicker, red dashed line) is the best linear fit of the raw data. The curve (solid black line) is the fitted line weighted by the mortality of the mosquito vector (pN). EVC is determined by integrating to find the area under this curve.

Discussion

Vector competence is a critical determinant of the success of a transmission cycle. It is affected by both intrinsic (genetically determined virus and vector) and extrinsic (environmental and ecological) factors.22 Specifically, transmission success of a virus by arthropod vectors is dependent on factors such as population density of the mosquitoes, susceptibility of amplifying hosts, environmental temperature, and the feeding preferences and habits.23 In South Florida, this mosquito species has already shown that it is competent for DENV and CHIKV, where local transmission has been reported.5,8

While we reported significant KOUTV dissemination rates in A. aegypti challenged with a high dose of KOUTV, it is important to consider other factors that would alter the vector competence of KOUTV. First, vector competence for DENV and CHIKV can vary significantly among populations of the same species of mosquito vector.24–26 It is likely that such variability would also be seen for KOUTV across A. aegypti populations. Second, genetic diversity among strains of DENV (within and among serotypes) and CHIKV affects vector competence and transmission potential.26,27 Likewise, this could affect KOUTV transmission, although there is a lack of data regarding KOUTV diversity. Third, extrinsic factors such as seasonality and mosquito ecology can affect vector competence.23,28,29 Little is known about the interface of KOUTV and A. aegypti ecology and remains to be intensively investigated. Lastly, as our methods are dependent on mosquito mortality, it is important to recognize that laboratory conditions promote longevity where field-mosquito mortality is likely highly variable and influenced by many extrinsic factors.

Lastly, KOUTV reached high dissemination rates after exposure to high titer (109 PFU/mL), but was undetected in the legs of mosquitoes challenged with a lower does (106 PFU/mL). This disparity in success of infection corresponding to the dose titer offered to mosquitoes indicates that the infectiousness of KOUTV may be limited to high doses. The epidemiological relevance of this finding is that only periods of high viremia will render a human (or potentially other vertebrate reservoirs) infectious. Given the relatively high dose required to infect mosquitoes and the role of infectiousness of humans in the probability of emergence, it is unlikely that KOUTV poses the same threat as other arboviruses such as dengue and chikungunya.5,8,23 However, since little is known about the infectivity of KOUTV in vertebrates, it is possible that serum viremia levels reach high titers capable of transmitting to mosquitoes.

Conclusions

A. aegypti pose a major health threat as they are competent for several arboviruses. Given the repeated introductions and eventual emergence of DENV and CHIKV in the southern United States, it is important to understand the potential for other viruses to emerge. Critical to our preparedness is an understanding of the potential contributors to transmission cycle(s) capable of maintaining these viruses. Here, we show that A. aegypti is capable of supporting KOUTV transmission at high titers. Therefore, more data are needed to determine the viremia titers of people infected with KOUTV or to determine what other potential reservoir species could support adequate viral loads.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

Conceptualized and performed experiments: JML, RCC, and CNM. Analyzed data: JML and RCC. Wrote the paper: JML, RCC, and CNM. Agree with manuscript results and conclusions: JML, RCC, CNM. Jointly developed the structure and arguments for the paper: JML, RCC, CNM. Made critical revisions and approved final version: JML, RCC, CNM. All authors reviewed and approved of the final manuscript.

ACADEMIC EDITOR: Timothy Kelley, Editor in Chief

FUNDING: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health P20GM103458, Tulane University School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine, the South Louisiana Institute for Infectious Disease Research sponsored by the Louisiana Board of Regents, and the NIH/NIGMS U01GM097661. The authors confirm that the funders had no influence over the study design, content of the article, or selection of this journal.

COMPETING INTERESTS: Authors disclose no potential conflicts of interest.

Paper subject to independent expert blind peer review by minimum of two reviewers. All editorial decisions made by independent academic editor. Prior to publication all authors have given signed confirmation of agreement to article publication and compliance with all applicable ethical and legal requirements, including the accuracy of author and contributor information, disclosure of competing interests and funding sources, compliance with ethical requirements relating to human and animal study participants, and compliance with any copyright requirements of third parties.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gubler DJ. Dengue and dengue hemorrhagic fever. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998 Jul;11(3):480–96. doi: 10.1128/cmr.11.3.480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Halstead SB. Dengue virus-mosquito interactions. Annu Rev Entomol. 2008;53:273–91. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.53.103106.093326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Division S, editor. Demographic year book, 1950–2007. United Nations: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Appawu M, Dadzie S, Abdul H, Asmah H, Boakye D, Wilson M, et al. Surveillance of viral haemorrhagic fevers in ghana: entomological assessment of the risk of transmission in the northern regions. Ghana Med J. 2006;40(4):137–41. doi: 10.4314/gmj.v40i3.55269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Florida Department of Health . Florida Health Series, Florida Health. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Americas Geographic Distribution | Chikungunya virus | CDC. 2014/07/31/T17:56:30Z. [Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/chikungunya/geo/americas.html], last updated September 17, 2014.

- 7.Leparc-Goffart I, Nougairede A, Cassadou S, Prat C, de Lamballerie X. Chikungunya in the Americas. Lancet. 2014 Feb 8;383(9916):514. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60185-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Florida Department of Health . Florida Health Series, Florida Health. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weaver SC, Reisen WK. Present and future arboviral threats. Antiviral Res. 2010 Feb;85(2):328–45. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Azil AH, Bruce D, Williams CR. Determining the spatial autocorrelation of dengue vector populations: influences of mosquito sampling method, covariables, and vector control. J Vector Ecol. 2014 Jun;39(1):153–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1948-7134.2014.12082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Charrel RN, Brault AC, Gallian P, Lemasson JJ, Murgue B, Murri S, et al. Evolutionary relationship between Old World West Nile virus strains. Evidence for viral gene flow between Africa, the Middle East, and Europe. Virology. 2003 Oct 25;315(2):381–8. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(03)00536-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prow NA, Setoh YX, Biron RM, Sester DP, Kim KS, Hobson-Peters J, et al. The West Nile-like flavivirus Koutango is highly virulent in mice due to delayed viral clearance and the induction of a poor neutralizing antibody response J Virol June. 18, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fall G, Diallo M, Loucoubar C, Faye O, Sall AA. Vector competence of Culex neavei and Culex quinquefasciatus (Diptera: Culicidae) from Senegal for lineages 1, 2, Koutango and a putative new lineage of West Nile virus. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2014 Apr;90(4):747–54. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.13-0405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Butenko AM, Semashko IV, Skvortsova TM, Gromashevskii VL, Kondrashina NG. Detection of the Koutango virus (Flavivirus, Togaviridae) in Somalia. Med Parazitol (Mosk) 1986 May-Jun;(3):65–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coz J, Valade M, Cornet M, Robin Y. Transovarian transmission of a Flavivirus, the Koutango virus, in Aedes aegypti L. C R Acad Sci Hebd Seances Acad Sci D. 1976 Jul 5;283(1):109–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Christofferson RC, Mores CN. Estimating the magnitude and direction of altered arbovirus transmission due to viral phenotype. PLoS One. 2011;6(1):e16298. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Turell MJ, Gargan TP, 2nd, Bailey CL. Replication and dissemination of Rift Valley fever virus in Culex pipiens. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1984 Jan;33(1):176–81. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1984.33.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alto BW, Lounibos LP, Mores CN, Reiskind MH. Larval competition alters susceptibility of adult Aedes mosquitoes to dengue infection. Proc Biol Sci. 2008 Feb 22;275(1633):463–71. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2007.1497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pesko K, Westbrook CJ, Mores CN, Lounibos LP, Reiskind MH. Effects of infectious virus dose and bloodmeal delivery method on susceptibility of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus to chikungunya virus. J Med Entomol. 2009 Mar;46(2):395–9. doi: 10.1603/033.046.0228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reiskind MH, Pesko K, Westbrook CJ, Mores CN. Susceptibility of Florida mosquitoes to infection with chikungunya virus. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008 Mar;78(3):422–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turell MJ, Dohm DJ, Mores CN, Terracina L, Wallette DL, Jr, Hribar LJ, et al. Potential for North American mosquitoes to transmit Rift Valley fever virus. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 2008 Dec;24(4):502–7. doi: 10.2987/08-5791.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tabachnick WJ. Nature, nurture and evolution of intra-species variation in mosquito arbovirus transmission competence. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2013 Jan;10(1):249–77. doi: 10.3390/ijerph10010249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Christofferson RC, Mores CN, Wearing HJ. Characterizing the likelihood of dengue emergence and detection in naive populations. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7(1):282. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-7-282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pongsiri A, Ponlawat A, Thaisomboonsuk B, Jarman RG, Scott TW, Lambrechts L. Differential susceptibility of two field aedes aegypti populations to a low infectious dose of dengue virus. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e92971. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ye YH, Ng TS, Frentiu FD, Walker T, van den Hurk AF, O’Neill SL, et al. Comparative susceptibility of mosquito populations in North Queensland, Australia to oral infection with dengue virus. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2014 Mar;90(3):422–30. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.13-0186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vega-Rua A, Zouache K, Girod R, Failloux AB, Lourenco-de-Oliveira R. High level of vector competence of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus from ten American countries as a crucial factor in the spread of Chikungunya virus. J Virol. 2014 Jun;88(11):6294–306. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00370-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guo XX, Zhu XJ, Li CX, Dong YD, Zhang YM, Xing D, et al. Vector competence of Aedes albopictus and Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) for DEN2–43 and New Guinea C virus strains of dengue 2 virus. Acta Trop. 2013 Dec;128(3):566–70. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2013.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aziz S, Aidil RM, Nisfariza MN, Ngui R, Lim YA, Yusoff WS, et al. Spatial density of Aedes distribution in urban areas: A case study of breteau index in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. J Vector Borne Dis. 2014 Apr-Jun;51(2):91–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stoddard ST, Wearing HJ, Reiner RC, Jr, Morrison AC, Astete H, Vilcarromero S, et al. Long-term and seasonal dynamics of dengue in iquitos, peru. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014 Jul;8(7):e3003. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]