Abstract

Alkyl bromides and chlorides can be reduced to the corresponding hydrocarbons utilizing zinc in the presence of an amine additive. The process takes place in water at ambient temperatures, enabled by a commercially available designer surfactant. The reaction medium can be readily recycled, and the amount of organic solvent invested for product isolation is minimal, leading to very low E Factors.

Introduction

Methods for the reduction of carbon halogen bonds play an indispensible role in organic synthesis. Reactions that count on such processes, such as halocyclizations, or the reduction of an alcohol via its halide derivative to its hydrocarbon oxidation state, can be readily found in textbooks. These include such classical approaches as use of tin hydride reagents, and Grignard formation/protio-quenching.1 While some may be applicable to mass reductions of environmental pollutants, such as PCBs, clean, mild, and green reductions of halogen-containing intermediates in highly functionalized systems remains quite a challenge.2 More recent methods such as photo-redox chemistry,3 while very efficient, relies on a precious metal, and super-stoichiometric amounts (i.e., 10 equiv each) of both i-Pr2NEt and formic acid to complete the catalytic cycle, which adds considerably to the waste stream despite its catalytic-in-metal nature. Perhaps the major drawback is the choice of solvent, as it must be carefully chosen to minimize absorbance from the light source. This led to the selection of DMF, a solvent with a questionable future due to its environmental toxicity and health hazards associated with its use.4 Other reagents such as NHC-borane complexes5 have also been shown to facilitate halide reduction, but such a process requires an additional equivalent of a trialkylborane or AIBN and is applicable only to activated alkyl halides.

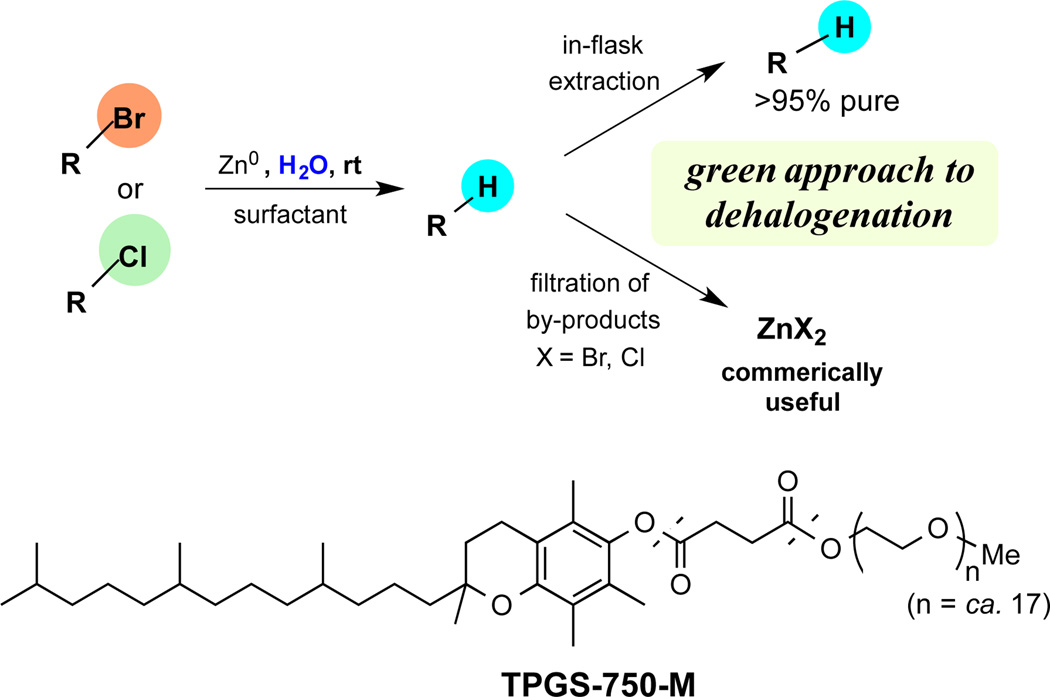

In this report we describe an especially straightforward, cost effective, and green technology for hydrodehalogenation of both activated and unactivated alkyl bromides, and activated chlorides, that takes place at room temperature in water as the only medium. The reduction is mediated by inexpensive, commercially available metallic zinc dust, enabled by the presence of nanomicelles composed of the commercially available designer surfactant TPGS-750-M (Scheme 1). The well-known compatibility of zinc6 with a wide range of functional groups is especially appealing and suggests that such an approach should be broadly applicable. Given the already aqueous nature of the reaction medium (0.5 M), workup only requires a simple filtration through silica gel to remove zinc and the surfactant from the reaction mixture (Scheme 1). In some cases, only a slight excess of zinc (1.1 equiv) is required, plus a sub-stoichiometric amount of an amine salt to achieve dehalogenation in high yields. This method generates a zinc halide salt as by-product that, in principle, has commercial value. Overall, the desired transformation is chemoselective, takes place in the absence of organic solvent,7 and offers the potential for recycling of the aqueous medium.

Scheme 1.

Dehalogenation of alkyl halidesutilizing zinc under micellar catalysis using designer surfactant TPGS-750-M.

Results and discussion

An initial screening of surfactants identified TPGS-750-M,8,9 as the preferred amphiphile in water. Given that it is an item of commerce, it was used throughout the study.10 The combination of zinc dust, along with tetramethylethylenediamine (TMEDA) in the pot, led to smooth dehalogenation. This result was anticipated based on earlier studies involving in situ organozinc halide formation, which in the presence of an aryl halide and Pd catalyst, led to net Negishi-like couplings.11 Related copper-catalyzed conjugate additions12 in water, following an initial formation of an organozinc halide, was also encouraging precedent.

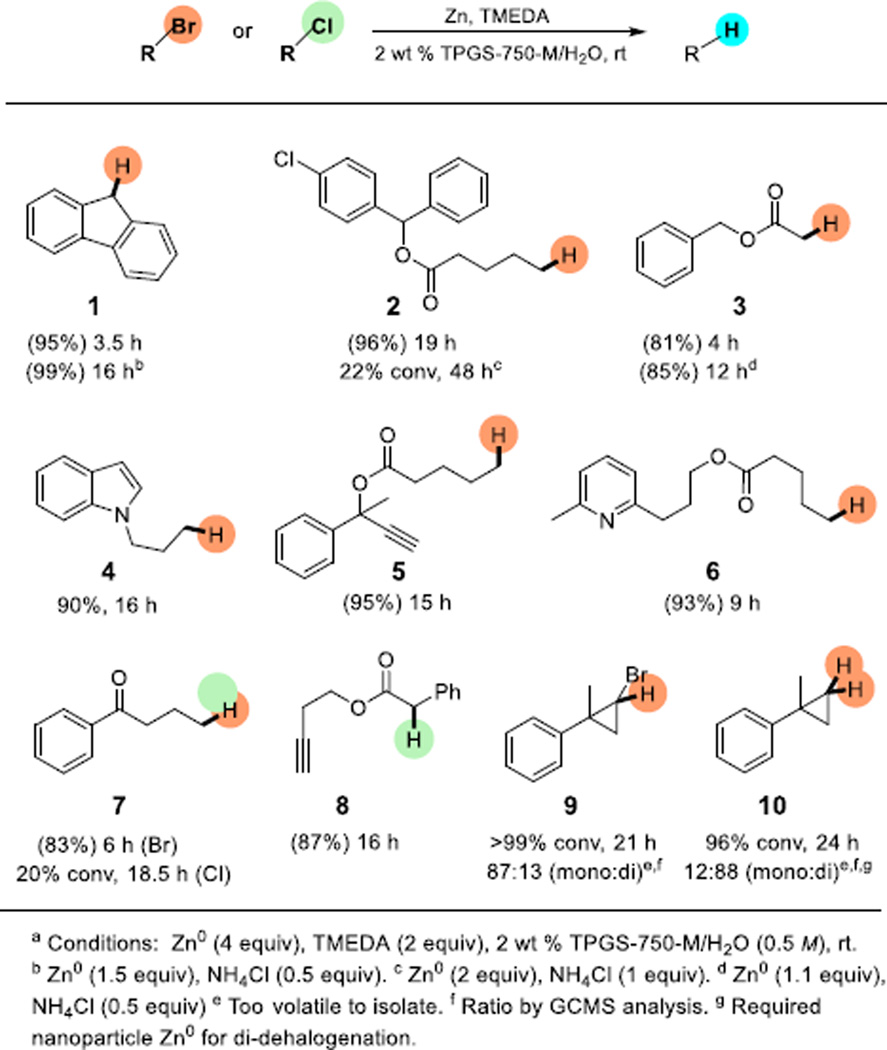

As shown in Scheme 2, a variety of activated and unactivated alkyl bromides was readily reduced under these conditions. Tolerance of a considerable range of functional groups was observed, as expected,11,12 and included pyridyl, indolyl, esters, ketones, terminal alkynes, and aryl halides. Unactivated alkyl chlorides appear to be nonresponsive to these conditions, although activated cases are smoothly reduced at room temperature (vide infra). As for a dihalocyclopropane, attempted reduction in the absence of TPGS-750-M (i.e., “on water”), afforded only 14% conversion, while 96% of this educt was reduced after 8 h in the presence of the amphiphile, a clear indication that micellar catalysis is involved in these reductions.

Scheme 2.

Dehalogenation of activated and unactivated alkyl halides.a

Selection of the zinc used is another important parameter, as zinc dust had the highest selectivity, while zinc powder showed limited reactivity. Use of more costly and highly active nano-sized zinc led to cleavage of ester groups, alkyne reduction, and dehalogenation of aryl halides(See Supporting Information for details). It is noteworthy that dehalogenation of the aryl chloride or reduction of the ester was not observed for 5 when nano-particle zinc was utilized. In the case of the dihalocyclopropyl system, reasonable selectivity for mono-dehalogeation can be achieved using zinc dust, while nanoparticle zinc was effective for di-dehalogenation, affording 10.

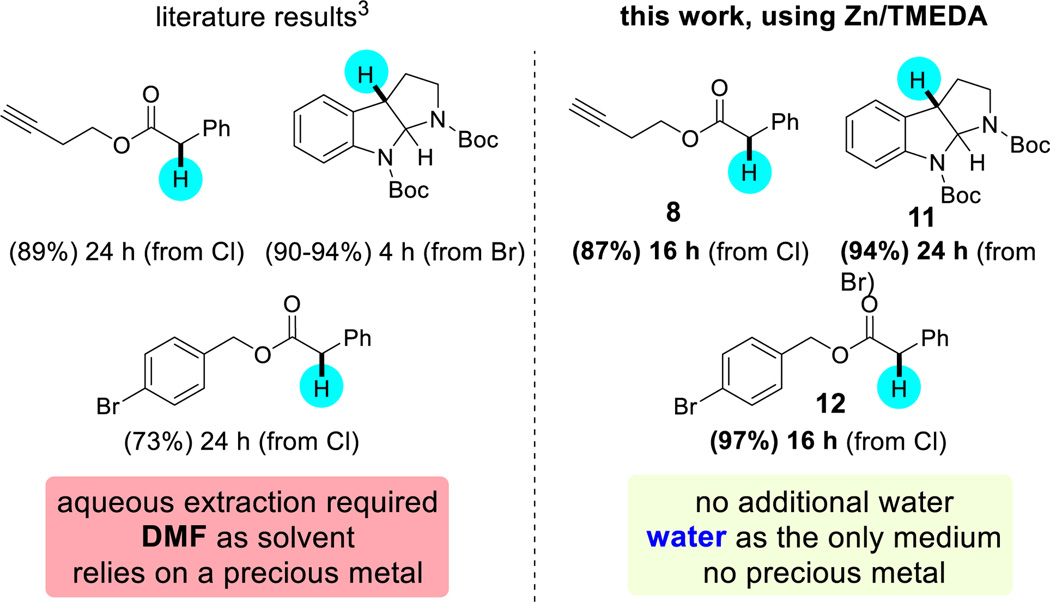

Direct comparison with Ru-catalyzed photo-redox chemistry involving both activated alkyl bromides and chlorides illustrates the competitive nature of this aqueous micellar approach.3 Thus, byusing inexpensive zinc ($1.2 Zn/mol substrate vs. $19.8 Ru/mol substrate), reliance on a precious-metal catalyst is averted,13 as is a traditional extraction, typically involving copious quantities of water to remove the DMF used as solvent (Scheme 3). This is yet anothercase where micellar catalysis can be not only a viable, but in fact highly attractive, alternative to dipolar aprotic solvents.14

Scheme 3.

Direct comparison of photoredox chemistry vs. micellar catalysis.

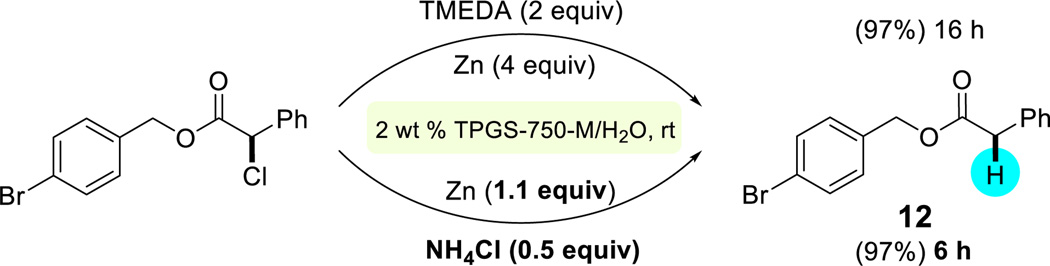

Activated alkyl chlorides were typically slower to reduce compared with alkyl bromides, and so attempts were made to improve reaction rates of these dehalogenations. Simply replacing TMEDA with ammonium chloride led to a significant acceleration in the rate of reduction (Scheme 4). As a bonus, it also allowed a decrease in the amount of zinc to just over stoichiometric levels.

Scheme 4.

Reaction rate acceleration and lower loading of zinc using NH4Cl in place of TMEDA.

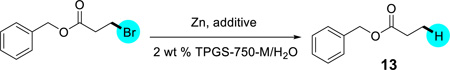

With the newfound use of NH4Cl as an additive it was thought that it could drastically reduce both the reaction times and stoichiometry of zinc. These conditions were applied to both unactivated and activated alkyl bromides (Scheme 2). Unfortunately, replacement of TMEDA with NH4Cl was applicable only to activated alkyl bromides, and required prolonged reaction times. Both 1 and 3 were fully dehalogenated in the presence of NH4Cl, but the former required 1.5 equiv of Zn, otherwise a moderate amount of homocoupling was observed. Low conversion was observed with unactivated cases 2 (Scheme 2) and 13 (Table 1, entry 1). Unactivated cases were successively dehalogenated as the amount approached the originally used 3 equivalents (Table 1, entry 3). Next, NH4OH was used instead to produce a more basic medium similar to TMEDA. The trend suggests that less zinc can be utilized for the dehalogenation of unactivated cases if conditions are basic (Table 1, compare entries 2 and 5).

Table 1.

Evidence of pH dependence for reduction of unactivated alkyl bromides with zinc

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | Zn (equiv) | additive (equiv) | pH | conva | time (h) |

| 1 | 2 | NH4Cl (0.5) | 4–5 | 13% | 48 |

| 2 | 2 | NH4Cl (1.0) | 4–5 | 22% | 48 |

| 3 | 3 | NH4Cl (1.0) | 4–5 | 78% | 22b |

| 4 | 1.1 | NH4OH (0.5) | 7–8 | 27% | 22b |

| 5 | 2 | NH4Cl (1.0) | 7–8 | 58% | 22b |

Reactions were run at rt; determined by GCMS of crude material.

No additional conversion was observed after this period of time.

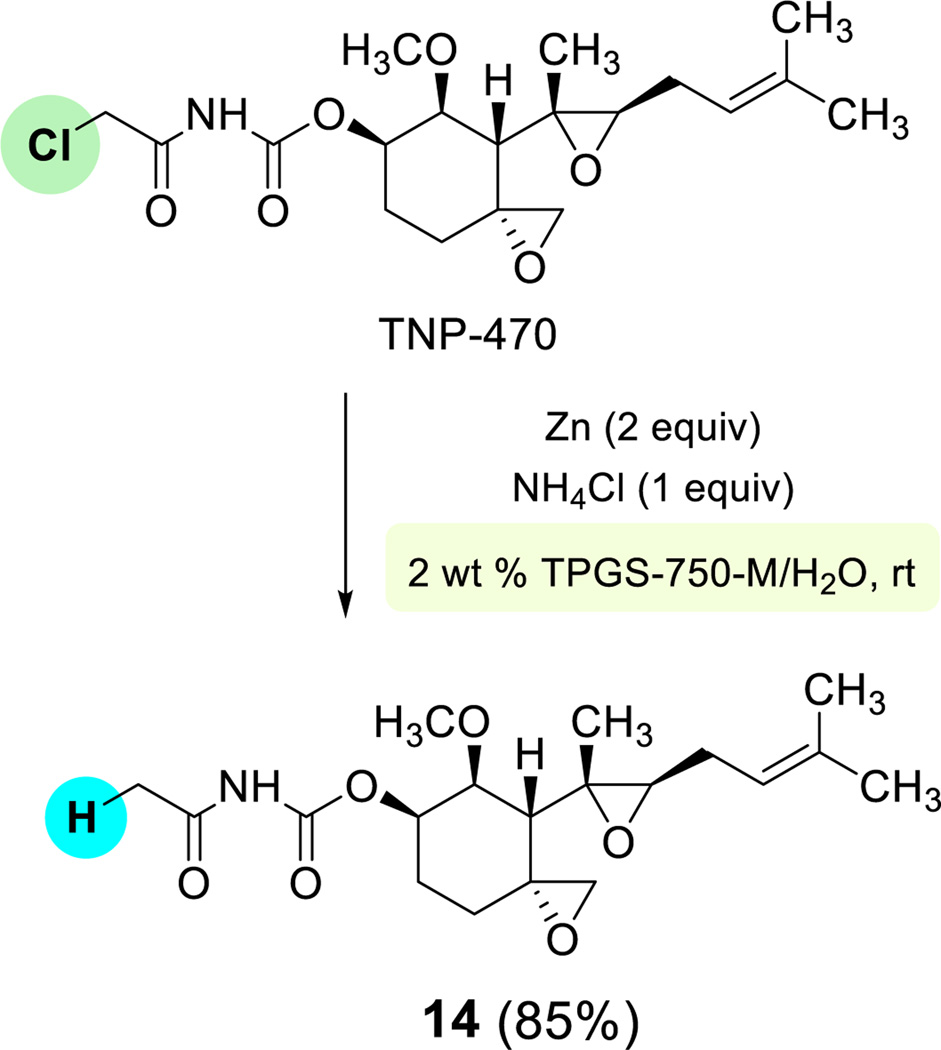

To demonstrate further the selectively and functional group compatibility of zinc under these micellar conditions, TNP-470, a potent antiangiogenic inhibitor containing an α-chloroamide15 was subjected to Zn-mediated reduction at room temperature in the presence of ammonium chloride. Selective dehalogenation was observed, affording the anticipated product 14 in good isolated yield.

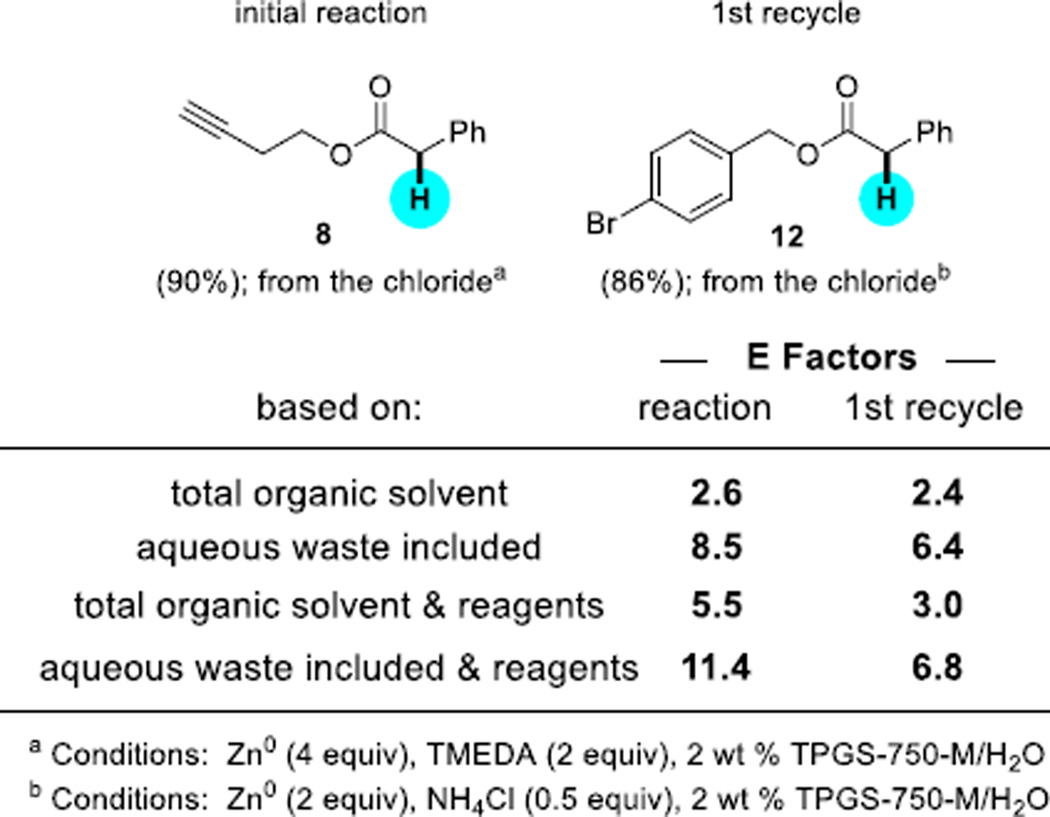

The opportunity also exists to recycle these aqueous reaction mixtures following an in-flask extraction with a single organic solvent (EtOAc in this case). Using an α-chloro ester as the educt, product 8 could be isolated in 90% yield (Scheme 6). Addition of a second, different α-chloro ester to the same aqueous reaction mixture afforded upon extraction product 12 in 86% isolated yield. Using the minimum amount of EtOAc in each of these product extractions, the calculated E Factors, based solely on the use of organic solvent usage (which is 85–90% of organic waste) and which traditionally do not include water, are very low (2.6 and 2.4, respectively).16 Even with water (i.e., the reaction medium) included as eventual waste, the E Factors (8.5 and then 6.4) are far lower than those typically reported for reactions by the pharmaceutical and fine chemicals industries.17 These numbers also compare favorably with those from other academic labs directly involved in related dehalogenation chemistry (see SI),3 although they are merely illustrative of the potential economic as well as environmental benefits to be realized from nanomicelle technology.

Scheme 6.

E Factors associated with recycling of the reaction medium.

Conclusions

In summary, an experimentally simple yet robust technology has been developed for reductions of alkyl bromides and chlorides containing a wide variety of potentially sensitive functional groups under aqueous micellar conditions at room temperature. A minimal amount of a single organic solvent is all that need be invested in order to extract the desired product. Hence, the E Factors associated with these reductions are very low, and are suggestive of the savings to both the cost of such reductions as well as the environment that might be anticipated by virtue of this chemistry.

Experimental

General Information

Unless otherwise noted, all reactions were performed under an atmosphere of argon. All commercially available reagents were used without further purification. A 2 wt % TPGS-750-M/H2O solution was prepared by dissolving 4 g TPGS-750-M in 196 g water (HPLC grade), followed by degassing with argon. TPGS-750-M was made as previously described.8 TPGS-750-M is also available commercially.10 Analytical thin layer chromatography (TLC) was performed using Silica Gel 60 F254 plates (Merck, 0.25 mm thick). The developed chromatogram was analyzed by UV lamp (254 nm). For non-UV active compounds were visualized by aqueous potassium permanganate (KMnO4), vanillin, or ninhydrin stain developed by heat with a heat gun. Flash chromatography was performed in glass columns using Silica Flash® P60 (SiliCycle, 40–63 µm). GC-MS data was recorded on a 5975C Mass Selective Detector, coupled with a 7890A Gas Chromatograph (Agilent Technologies). As capillary column a HP-5MS cross-linked 5% phenylmethylpoly-siloxanediphenyl column (30 m × 0.250 mm, 0.25 micron, Agilent Technologies) was employed. Helium was used as carrier gas at a constant flow of 1 mL/min. The following temperature program was used: 50 °C for 5 min; heating rate 20°C/min; 300 °C for 20 min; injection temperature 250 °C; detection temperature 280 °C. 1H and 13C NMR were recorded at 22 °C on a Varian UNITY INOVA 400 MHz, 500 MHz, or 600 MHz. Chemical shifts in 1H NMR spectra are reported in parts per million (ppm) on the δ scale from an internal standard of residual chloroform (7.26 or 7.27 ppm). Data are reported as follows: chemical shift, multiplicity (s = singlet, d = doublet, t = triplet, q = quartet, p = pentet, sex = sextet, sep = septet, oct = octet, m = multiplet, br = broad), coupling constant in Hertz (Hz), and integration. Chemical shifts of 13C NMR spectra are reported in ppm from the central peak of CDCl3(77.23 ppm) on the δ scale. High resolution mass analyses were obtained using an APE Sciex QStar Pulsar quadrupole/TOF instrument (API) for ESI, or a GCT Premier TOF MS (Waters Corp) for FI.

General procedure for Zn-mediated reductions of alkyl halides

To a 5 mL round bottom flask or 5 mL microwave vial equipped with a stir bar, and fitted with a rubber septum under argon atmosphere was sequentially charged with Zn (4 equiv.). Under a positive flow of argon were added via syringe the 2 wt % TPGS-750-M/H2O solution (0.5 mL, 0.5 M). While stirring vigorously, TMEDA (2 equiv.) was added via syringe followed by the alkyl halide (0.25 mmol). The mixture was vigorously stirred at rt until completion (monitored by TLC and/or GC-MS) was determined. The mixture was diluted with EtOAc and filtered through a pad of silica gel. The solvent was removed via rotary evaporation. The crude was purified by column chromatography (eluent: EtOAc/hexanes or Et2O/hexanes) as necessary.

General procedure for E Factor study

To a 5 mL microwave vial equipped with a stir bar, fitted with a rubber septum and cooled under an argon atmosphere was charged with Zn (4 equiv.). Under a positive flow of argon, was added via syringe the 2 wt % TPGS-750-M/H2O solution (1.0 mL, 1.0 M). While stirring vigorously, TMEDA (2 equiv.) was added via syringe followed by but-3-yn-1-yl-2-chloro-2-phenylacetate (1.0 mmol). The reaction was allowed to stir vigorously until complete. The product was extracted with EtOAc using gentle stirring: (250 µL + 250 µL). To ease separation a centrifuge can be used. The organic solvent was evaporated via rotary evaporation. The crude product was purified by silica gel column chromatography (eluent: gradient from 1 to 10% EtOAc/hexanes) to provide the desired compound as a colorless oil (170 mg, 90% yield).

General procedure for recycling of the aqueous surfactant solution

After extraction of the desired product from the aqueous phase, reuse of the surfactant solution was employed by adding additional Zn (2 equiv) to the flask. Next, NH4Cl (0.5 equiv) and 4-bromobenzyl 2-chloro-2-phenylacetate (1.0 mmol) were added. The reaction was allowed to stir at rt until complete. The product was extracted with EtOAc (350 µL + 350 µL). The organic solvent was evaporated via rotary evaporation. The crude product was purified by silica gel column chromatography (eluent: gradient from 1 to 10% EtOAc/hexanes) to provide the desired compound as a colorless oil (262 mg, 86% yield).

Supplementary Material

Scheme 5.

Reduction of TNP-470 under micellar conditions.

Acknowledgments

Financial support provided by the NIH (GM 86485) for our programs in green chemistry is warmly acknowledged with thanks.

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available. Copies of 1H and 13C NMR characterization data for all new compounds: See DOI: 10.1039/c000000x/

Notes and references

- 1.(a) For a comprehensive review of methods, see: Alonso F, Beletskaya IP, Yus M. Chem. Rev. 2002;102:4009. doi: 10.1021/cr0102967. (b) Using titanium isopropoxide and an excess of EtMgBr, see: Al Dulayymi JR, Baird MS, Bolesov IG, Tveresovsky V, Rubin M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996;37:8933.

- 2.(a) Using samarium iodide, see: Zhang Y, Yu Y, Bao W. Synth. Commun. 1995;25:1825. Gioia FJ. Haz. Mat. 1991;26:243. Kovenklioglu S, Cao Z, Shah D, Farrauto RJ, Balko EN. AIChE Journal. 1992;38:1003. For the early use of Zn in non-selective halide reductions in organic solvents, see Hekmatshoar R, Sajadi S, Heravi MM. J. Chinese Chem. Soc. 2008;55:616. Mahalingam SM, Krishnan H, Satam VS, Bandi R, Pati HN. Org. Chem.: An Indian Journal. 20095:36.

- 3.(a) Narayanam JMR, Tucker JW, Stephenson CRJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:8756. doi: 10.1021/ja9033582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Douglas JJ, Nguyen JD, Cole KP, Stephenson CRJ. Aldrichimica Acta. 2014;47:15. [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Laird T, editor. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2012;16:1. doi: 10.1021/op2002613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Dunn PJ. In: Pharmaceutical Process Development. chapter 6 Blacker JA, Williams MT, editors. London: Royal Society of Chemistry; 2011. [Google Scholar]; (c) Jimenez-Gonzales C, Constable DJ. Green Chemistry and Engineering: A Practical Approach. New York: Wiley; 2011. [Google Scholar]; (d) Constable DJC, Dunn PJ, Hayler JD, Humphrey GR, Leazer JL, Linderman RJ, Lorenz K, Manley J, Pearlman BA, Wells A, Zaks A, Zhang TY. Green Chem. 2007;9:411. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ueng S-H, Fensterbank L, Lacôte E, Malacria M, Curran DP. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2011;9:3415. doi: 10.1039/c0ob01075h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Knochel P, Leuser H, Gong L-Z, Perone S, Kneisel FF. In: In Handbook of Functionalized Organometallics. chapter 7. Knochel P, editor. Vol. 1. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hekmatshoar R, Sajadi S, Heravi MM. J. Chinese Chem. Soc. 2008;55:616. [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Lipshutz BH, Ghorai S. Aldrichimica Acta. 2012;45:3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lipshutz BH, Ghorai S. Aldrichimica Acta. 2008;41:59. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lipshutz BH, Ghorai S, Leong WWY, Taft BR. J. Org. Chem. 201176:5061. doi: 10.1021/jo200746y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aldrich catalog numbers 733857 and 763918.

- 11.(a) Krasovskiy A, Duplais C, Lipshutz BH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:15592. doi: 10.1021/ja906803t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Duplais C, Krasovskiy A, Lipshutz BH. Organometallics. 2011;30:6090. doi: 10.1021/om200846h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lipshutz BH, Huang S, Leong WWY, Zhong G, Isley NA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:19985. doi: 10.1021/ja309409e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.The prices of zinc dust, 98% (cat. # 209988) vs. tris(bipyridine)ruthenium(II) chloride powder (cat. # 224758) in the Sigma-Aldrich® catalog were compared. It was assumed that 0.05 mol % of ruthenium catalyst was used (this loading was also only documented with one substrate),3 or 400 mol % of zinc dust for each respective substrate. Last accessed April 15th, 2014.

- 14.Isley NA, Gallou F, Lipshutz BH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:17707. doi: 10.1021/ja409663q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.(a) Benny O, Fainaru O, Adini A, Cassiola F, Bazinet L, Adini L, Pravda E, Nahmias Y, Koirala S, Corfas G, D’Amato RJ, Folkman J. Nature Biotech. 2008;26:799. doi: 10.1038/nbt1415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Moulton KS, Heller E, Konerding MA, Flynn E, Palinski W, Folkman J. Circulation. 1999;99:1726. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.13.1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Yamaoka M, Vaniamolo T, Ikeyama S, Sudo K, Fujita T. Cancer Res. 1993;53:5233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lipshutz BH, Isley NA, Fennewald JC, Slack ED. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013;52:10952. doi: 10.1002/anie.201302020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sheldon RA, Arends IWCE, Hanefeld U. Green Chemistry and Catalysis. Weinheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH; 2007. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.