Abstract

Background

An overproduction of corticosterone during severe sepsis results in increased apoptosis of immune cells, which may result in relative immunosuppression and an impaired ability to fight infections. We have previously demonstrated that administration of Tubastatin A, a selective inhibitor of histone deacetylase-6 (HDAC6), improves survival in a lethal model of cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) in mice. The purpose of this study was to characterize the effects of this treatment on sepsis-induced stress responses and immune function.

Methods

C57BL/6J mice were subjected to CLP, and 1 hour later given an intraperitoneal injection of either Tubastatin A dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), or DMSO only. Blood samples were collected to measure the levels of circulating corticosterone and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). Thymus, and long bones (femur and tibia) were subjected to H&E staining, and immunohistochemistry was utilized to detect cleaved-caspase 3 in the splenic follicles as a measure of cellular apoptosis.

Results

All vehicle-treated CLP animals died within 3 days, and displayed increased corticosterone and decreased ACTH levels compared to the sham-operated group. These animals also developed atrophy of thymic cortex with a marked depletion of thymocytes. Tubastatin A treatment significantly attenuated the stress hormone abnormalities. Treated animals also had significantly lower percentages of thymic atrophy (95.0±5.0 vs. 42.5±25.3, p=0.0366), bone marrow depletion and atrophy (58.3±6.5 vs. 25.0±14.4%, p=0.0449), and cellular apoptosis in the splenic follicles (41.2±3.7 vs. 28.5±4.3 per 40× field, p=0.0354).

Conclusions

Selective inhibition of HDAC6 in this lethal septic model was associated with a significant blunting of the stress responses, with attenuated thymic and bone marrow atrophy, and decreased splenic apoptosis. Our findings identify a novel mechanism behind the survival advantage seen with Tubastatin A treatment.

Introduction

Severe sepsis and septic shock are the leading cause of death in critically ill patients in the United States, and no pharmacological treatments have conclusively been shown to improve survival.1 Sustained biological stress to host occurs during sepsis, and the integrity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis determines the host's response to this stress.2 Thymus, bone marrow, and spleen are important immune organs that interact with the HPA axis and play an essential role in maintaining a robust and healthy immune system.3-5 We now know that the HPA axis becomes dysfunctional and the neuroendocrine stress response system is disrupted during sepsis.6 Glucocorticoids released during sepsis are potent inducers of apoptosis and inhibitors of immune cell proliferation, which may result in relative immunosuppression and an impaired ability to fight infections.7

The acetylation status of chromatin is balanced by the activities of histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and histone deacetylases (HDACs), which can activate or suppress gene expression. HDAC6 belongs to class IIb HDAC, and is a unique HDAC localized in the cytoplasm, where it associates with non-histone substrates.8 HDAC6 has become a target for the development of anti-cancer drugs and its inhibition can ameliorate central nervous system injury.9, 10 Tubastatin A is a selective HDAC6 inhibitor with simple synthesis and superior target selectivity that has recently been developed.11

Our laboratory has demonstrated that selective inhibition of HDAC6 with Tubastatin A displays dramatically better survival outcomes compared to inhibition of HDAC1, 2, and 3 in the lethal CLP-sepsis model (data presented at the 99th Annual Clinical Congress of American College of Surgeons, October 2013). However, the mechanisms underlying the survival advantages after Tubastatin A treatment remain unclear. The purpose of this study was to characterize the effects of Tubastatin A treatment on sepsis-induced stress responses and immune organs. We hypothesized that inhibition of HDAC6 would attenuate stress responses and protect immune organs during sepsis.

Materials and Methods

Sepsis Model: Cecal Ligation and Puncture (CLP)

Male C57BL/6J mice (18-26 gm) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory and housed for 3 days before manipulations. The CLP murine model,12 modified by our laboratory, was used to induce fecal peritonitis. In brief, the peritoneal cavity was opened under inhaled isoflurane anesthesia. Cecum was eviscerated, ligated below the ileocecal valve using a 5-0 suture, and punctured through and through (2 holes) with a 20 gauge needle. The punctured cecum was squeezed to expel a small amount of fecal material and returned to the peritoneal cavity. The abdominal incision was closed in two layers with 4-0 silk suture. Animals were resuscitated by subcutaneous injection of 1 mL of saline. Sham-operated animals were handled in the same manner, except that the cecum was not ligated or punctured. This protocol was approved by the Animal Review Committee at the Massachusetts General Hospital. All surgery was performed under anesthesia, and all efforts were made to minimize suffering.

Administration of Tubastatin A and Experimental Design

Animals were randomly assigned to the following four groups (n = 6-10/group/time point): (a) Sham-operated animals (Sham); (b) Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) vehicle treated animals after CLP (CLP + DMSO), and (c) Tubastatin A treated animals after CLP (CLP + Tub.A). Mice received intra-peritoneal Tubastatin A (70 mg/kg) dissolved in DMSO or vehicle DMSO 1 h post-procedure. Sham-operated animals were subjected to laparotomy and intestinal manipulation, but the cecum was neither ligated nor punctured. Animals were sacrificed at 24 and 48 h after CLP (n= 6-10/group/time point).

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

Blood samples from three groups were collected at 24 and 48 h after CLP. Concentrations of circulating corticosterone and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) were measured using an ELISA Kit (Immunodiagnostic Systems Inc, Fountain Hill, AZ; MD Biosciences, St. Paul, MN; respectively) according to manufacturer's instructions.

Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) Staining

Tissue samples of thymus, and long bones (femur and tibia) were harvested for histological analysis 48 h after CLP. Each sample was fixed by immersing in 10% buffered formalin. The samples were then embedded in paraffin, sliced into 5-μm sections and stained with H&E. Atrophy of thymic cortex and bone marrow were graded by a pathologist blinded to group allocation of the samples. The degree of thymic cortex and bone marrow atrophy was graded on a scale of 0%-100%, with 0% meaning “no atrophy,” and 100% meaning “complete atrophy.” Thymic cortex atrophy was evaluated according to the degree of thymocyte depletion in the cortex, and bone marrow atrophy was evaluated according to the diameter proportion of veins to bone marrow cells.13

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) and Celluar Apoptosis Measurement

Spleen samples were harvested at 24 h after CLP and fixed by immersing in 10% buffered formalin. Samples were then embedded in paraffin, and sliced into 5-μm sections. A rabbit anti-mouse cleaved Caspase-3 Ab (Cell Signaling Technology, Davers, MA) was used in a concentration of 1:100 incubating at 4°C overnight, and a goat anti-rabbit polymer-AP secondary antibody (Biocare Medical, Concord, CA) was used in a concentration of 1:200 at room temperature for 30 min. Vulcan Fast Red Chromogen Kit (Biocare Medical, Concord, CA) was then used for fluorescence and the slides were counterstained with hematoxylin (Mossberg Labs, Kalamazoo, MI).14 Apoptotic cells in splenic follicle, as stained with cleaved Caspase-3, were counted in the 40× field of microscope (n = 3 splenic follicles/animal, 4 animals/group).

Statistical Analysis

Data were presented asgroup means ± standard error of mean (SEM). Differences between three groups were assessed using one way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni post hoc testing for multiple comparisons. Student's t-test was used to compare the differences between two groups. All analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism. A p value of 0.05 or less were considered significant.

Results

Tubastatin A significantly attenuates stress hormone abnormalities in a lethal septic model

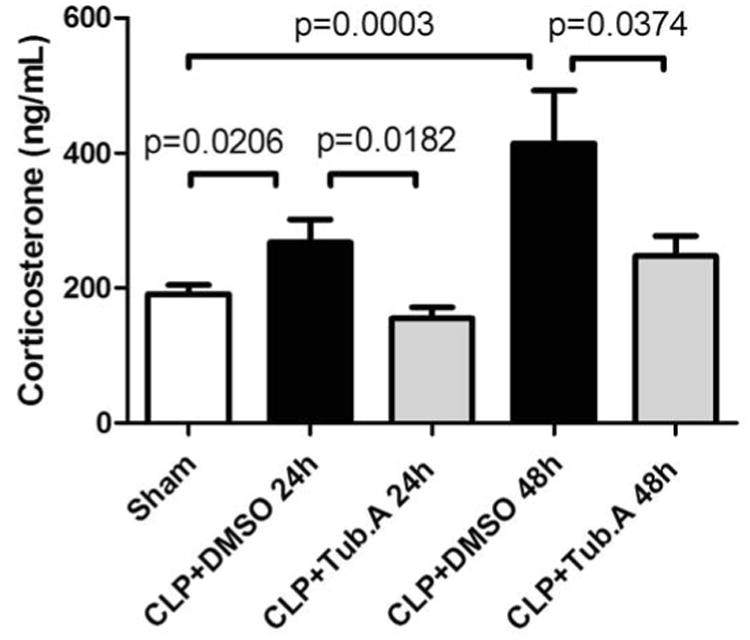

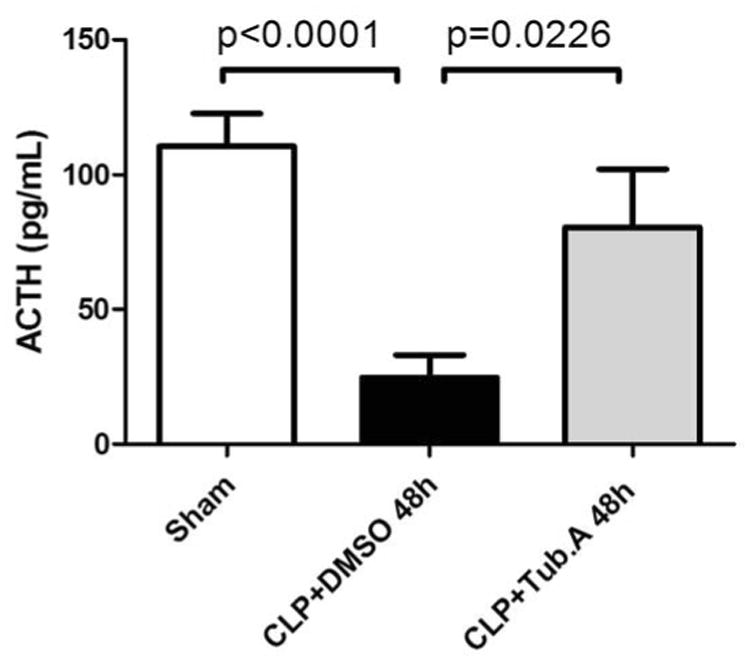

Animals in vehicle-treatment group displayed increased corticosterone at 24 h (191.0 ± 13.4 vs. 267.5 ± 34.3 ng/mL, p = 0.0206) and 48 h (191.0 ± 13.4 vs. 414.8 ± 77.4 ng/mL, p = 0.0003; Figure 1) compared to the sham-operated group. Tubastatin A treatment significantly attenuated abnormal plasma corticosterone levels at 24 h (267.5 ± 34.3 vs. 154.7 ± 16.8 ng/mL, p = 0.0182) and 48 h (414.8 ± 77.4 vs. 247.8 ± 29.5 ng/mL, p = 0.0374; Figure 1). In addition, vehicle-treated CLP animals had decreased ACTH levels compared to the sham-operated group at 48 h (110.4 ± 12.2 vs. 24.6 ± 8.4 pg/mL, p < 0.0001), corresponding to the negative feedback due to high circulating corticosterone levels. Tubastatin A treatment restored plasma ACTH levels in CLP animals at 48 h (24.6 ± 8.4 vs. 80.4 ± 21.8 pg/mL, p = 0.0226; Figure 2).

Figure 1. Tubastatin A attenuates plasma corticosterone levels significantly in a lethal septic model.

Data presented as group mean ± SEM (n = 6-10 animals/group). CLP = cecal ligation and puncture; Tub.A = Tubastatin A; DMSO = Dimethyl sulfoxide.

Figure 2. Tubastatin A restores plasma adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) levels in the lethal septic model.

Data presented as group means ± SEM (n = 6-10 animals/group). CLP = cecal ligation and puncture; Tub.A = Tubastatin A; DMSO = Dimethyl sulfoxide.

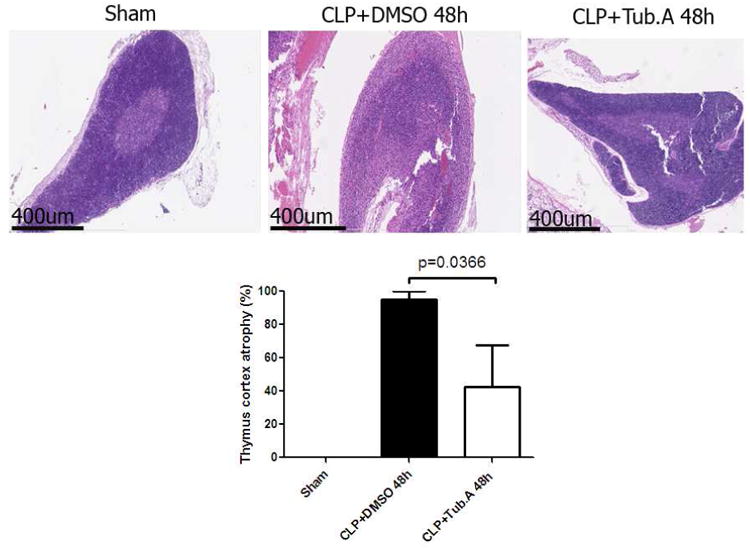

Tubastatin A decreases thymic cortex atrophy during severe sepsis

Sham-operated animals had normal thymus morphology and histology, with cortex stained purple. Vehicle-treated CLP animals developed atrophy of thymic cortex 48 h after CLP. This manifested as a marked depletion of thymocytes, making the cortex appear pink and the medulla appear darker in contrast, and a loss of distinct cortico-medullary junction (atrophy percentage: 0 ± 0 vs. 95.0 ± 5.0 %; Figure 3). Tubastatin A-treated animals showed less thymocyte depletion and significantly lower percentage of thymic atrophy (95.0 ± 5.0 vs. 42.5 ± 25.3 %, p= 0.0366; Figure 3).

Figure 3. Tubastatin A decreases thymic cortex atrophy during severe sepsis (Hematoxylin and Eosin stain, magnification 4×).

Representative images from different experimental groups are presented in the top panel. Pathological scores for thymic cortex atrophy are displayed in the lower panel. Data presented as group means ± SEM (n = 4-6 animals/group). CLP = cecal ligation and puncture; Tub.A = Tubastatin A; DMSO = Dimethyl sulfoxide.

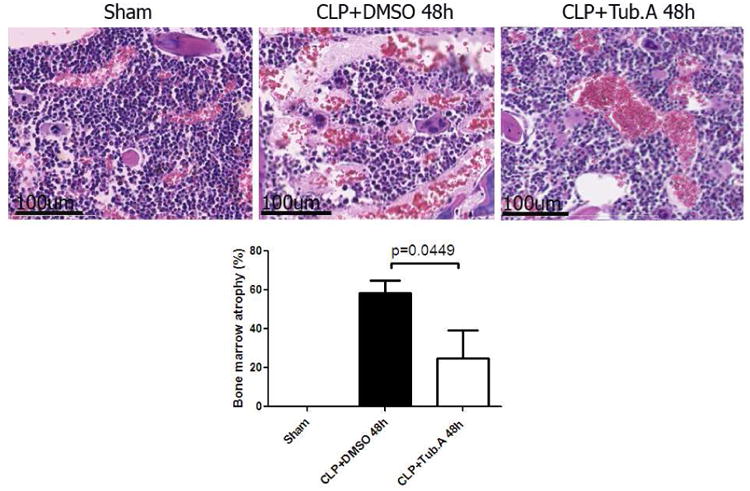

Tubastatin A decreases bone marrow depletion and atrophy during severe sepsis

Sham-operated animals displayed normal bone marrow histology and cellular composition. In vehicle treatment group, the proportion of veins to bone marrow cells increased at 48 h after CLP, with venous dilation and bone marrow cell depletion (0 ± 0 vs. 58.3 ± 6.5 %; Figure 4). The bone marrow depletion and atrophy were markedly decreased by Tubastatin A treatment (58.3 ± 6.5 vs. 25.0 ± 14.4 %, p = 0.0449; Figure 4).

Figure 4. Tubastatin A decreases bone marrow atrophy during severe sepsis (Hematoxylin and Eosin stain, magnification 40×).

Representative images from different experimental groups are presented in the top panel. Pathology scores for bone marrow atrophy graded according to the diameter proportion of veins to bone marrow cells (described in Materials and Methods) are displayed in the lower panel. Data presented as group means ± SEM (n = 4-6 animals/group). CLP = cecal ligation and puncture; Tub.A = Tubastatin A; DMSO = Dimethyl sulfoxide.

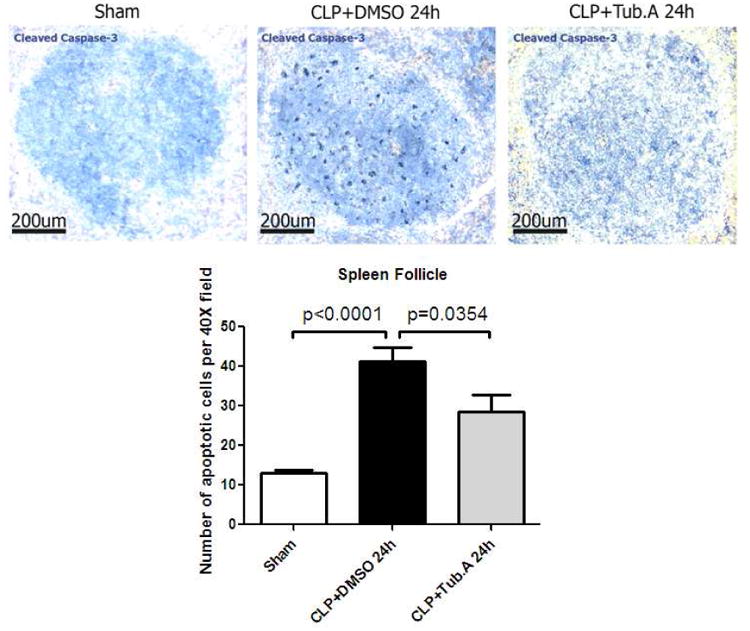

Tubastatin A decreases cellular apoptosis in splenic follicles during severe sepsis

The number of apoptotic cells in splenic follicles of sham-operated animals was low. Vehicle-treated CLP animals displayed an increased number of apoptotic cells in the splenic follicles at 24 h after CLP (13.0 ± 0.8 vs. 41.2 ± 3.7 per 40× field, p < 0.0001; Figure 5), whereas Tubastatin A treatment significantly decreased the number (41.2 ± 3.7 vs. 28.5 ± 4.3 per 40× field, p = 0.0354; Figure 5).

Figure 5. Tubastatin A decreases cell apoptosis in splenic follicle during severe sepsis (IHC, magnification 20×).

Representative images from different experimental groups are presented in the top panel. Number of apoptotic cells (stained with cleaved caspase-3) are displayed in the lower panel. Data presented as group means ± SEM (n = 3 splenic follicles/animal, 4 animals/group). CLP = cecal ligation and puncture; Tub.A = Tubastatin A; DMSO = Dimethyl sulfoxide.

Discussion

We have explored the effects of HDAC6 inhibitor Tubastatin A on sepsis-induced stress responses and immune organs utilizing a lethal CLP septic model, and discovered the following important findings: (1) Inhibition of HDAC6 by Tubastatin A significantly attenuated the stress hormone abnormalities; (2) Tubastatin A-treated animals also had significantly lower percentages of thymic atrophy, bone marrow depletion and atrophy, and apoptosis in splenic follicles.

Histone acetylation is an essential epigenetic mechanism that determines the amplitude of cellular and subcelluar signaling, by controlling gene transcription. Our research team has demonstrated that both hemorrhage and sepsis can lead to protein hypoacetylation, whereas therapeutically targeting the alterations with HDACIs induces acetylation of histone and non-histone proteins, and is protective against lethal insults, such as hemorrhagic shock, traumatic brain injuries, endotoxemic shock, and severe sepsis.15-18 In humans and mice, the 18 HDAC enzymes are grouped into four classes: classical HDACs, including class I, II and IV, are Zn2+ dependent, while the classes III sirtuins act through a NAD+-dependent mechanism. HDAC6 belongs to class IIb HDAC and is unique in that it is a cytoplasmic microtubule-associated enzyme. HDAC6 deacetylates tubulin, HSP90 and cortactin, forms complexes with other partner proteins, and involves innumerous biological processes, such as cell migration and cell-cell interactions.19 The selective inhibition of HDAC6 activity or its downregulation by siRNA increases acetylation of α-tubulin and HSP90, resulting in the degradation of HSP90 client proteins, including Bcr-Abl, interleukin-1 receptor associated kinase 1 (IRAK1), and hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α.

Persistent sepsis creates an immunosuppressive status, as evidenced by an inability to clear primary infection, a predisposition to nosocomial infections, and a loss of delayed hypersensitivity.20, 21 Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated whole blood from patients in the late stages of severe sepsis was found to release less inflammatory cytokines compared to the control patients.22 Meanwhile, monocyte deactivation and immunoparalysis in septic patients could be reversed by immune stimulant interferon-gamma treatment.23 We discovered in this study that Tubastatin A treatment attenuates sepsis induced-stress responses and prevents immune organ atrophy, which could potentially alleviate the immunosuppressive state and strengthen immune functions.

Sepsis causes severe and sustained biological stress to the host, and the integrity of the HPA axis is a major determinant of the host's response to this stress.2 As sepsis worsens, the HPA axis becomes dysfunctional and the neuroendocrine stress response system is disrupted.6 Septic patients exhibit higher baseline cortisol levels and decreased blood ACTH-to-cortisol ratio, compared to non-septic patients.24 The pituitary gland is activated through systematic proinflammatory mediators and complex interactions between the autonomic nervous system and the immune cells.25 Within a few minutes of onset, sepsis induces the secretion of ACTH, growth hormone and prolactin, and inhibits the secretion of luteinizing and thyroid-stimulatory hormones.6 However, as sepsis progresses, ACTH and vasopressin levels drop, which is a deleterious consequences of the abnormal pituitary response, contributing to the progression of inflammatory responses, shock, adrenal insufficiency, multiple organ failure and death.26 The prognosis of patients with septic shock can be predicted based on cortisol levels and cortisol response to ACTH. Despite high baseline cortisol levels, a poor response to ACTH stimulation test is suggestive of relative adrenal insufficiency, which correlates with poor outcomes.27

We discovered that Tubastatin A-treated animals displayed lower levels of plasma corticosterone, the main glucocorticoid in rodents, and higher ACTH levels compared to vehicle treated animals in the lethal septic model, indicating that the inhibition of HDAC6 attenuates sepsis-induced stress responses, protects against adrenal insufficiency, and prevents the burnout of HPA system during severe sepsis, which may explain the survival advantage seen with Tubastatin A treatment. Evidence on how acetylation affects the HPA axis is scarce. TSA, an HDAC class I and II inhibitor, has been found to increase the mRNA levels and promoter activity of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), when co-cultured with hypothalamic cells.28 Another study revealed that increased HDAC expression was associated with decreased plasma cortisol levels in older adults with chronic fatigue syndrome.29 Whether the inhibition of HDAC6 decreases the stress response indirectly (through decreased levels of proinflammatory mediators and better bacterial clearance), or directly (effect on hypothalamus, pituitary and adrenal glands) needs to be further explored.

Lower levels of stress hormones in the Tubastatin treated animals may have been responsible for the decreased thymic and splenic atrophy. Glucocorticoids are known to be potent inducers of apoptosis and inhibitors of cellular proliferation of immune cells, and the induction of cell death in lymphoid cells by glucocorticoids is well documented.7, 30 CLP-induced apoptosis in thymus and spleen is mediated primarily by corticosteroids instead of endotoxins or tumor necrosis factor (TNF).4, 31 Moreover, animals treated after CLP with RU-38486, a steroid receptor blocker, displayed a marked decrease in thymocyte apoptosis and DNA fragmentation, whereas this was not seen in animals treated with polyethylene glycol PEG-(rsTNF-R1)2, a TNF inhibitor.31

Thymus exhibits a high density of glucocorticoid type-II receptors compared to other lymphoid organs. The immature CD4+CD8+ thymocyte subpopulation is extremely sensitive to acute and chronic stressors, resulting in acute thymic atrophy and decreased production of T lymphocytes, in clinical settings such as infection, malnutrition, starvation, irradiation and immunosuppressive therapies.32, 33 There is also depletion and apoptosis of splenic interdigitating and follicular dendritic cells in CLP sepsis endotoxemia, which compromises the functions of B and T cells leading to immunosuppression of the host.14, 34 B cells in germinal center of the splenic follicle undergo complex interactions with follicular dendritic cells and T cells in the course of differentiation into memory B and plasma cells, and apoptosis of the dendritic cells can disrupt this process.34 Theoretically, decreased apoptosis and cell depletion in thymic cortex and splenic follicles after Tubastatin A in our study would render the host better equipped to survive sepsis.

However, unlike thymus and spleen, bone marrow atrophy is not affected by glucocorticoids or TNF released during sepsis, as treatment with either RU-38486 or PEG-(rsTNF-R1)2 was unable to reverse the bone marrow apoptosis in CLP-subjected mice.35 There is a 4-fold decrease in the percentage of Grl+-myeloid cells in bone marrow during CLP sepsis (accounting for 80% of the decrease in cells), but this is not due to an increase in apoptosis.35 The most likely explanation is that the myeloid cells are recruited to inflammatory sites outside the bone marrow as opposed to undergoing apoptotic cell death in the marrow. Tubastatin A may attenuate bone marrow atrophy indirectly by decreasing the levels of cytokines and bacteria in the circulation (data presented at the 99th Annual Clinical Congress of American College of Surgeons, October 2013). This would reduce chemotaxis and recruitment of myeloid cells and prevent bone marrow depletion and exhaustion.

Moreover, we have recently found that Tubastatin A increases circulating monocyte count, decreases the percentage of granulocytes, restores the lymphocyte population, and reduces the ratio of granulocyte to lymphocyte in CLP animals (data presented at the 9th Annual Academic Surgical Congress in San Diego, CA). In addition, Tubastatin A decreases cytokines levels in peritoneal fluid and circulation, as well as supernatant of cultured primary splenocytes (Data presented at the 99th Annual Clinical Congress of American College of Surgeons in Washington, DC; abstract published in J Am Coll Surg. 2013 Sep; 217 (3) Supplement: S45). Taken together, these findings suggest that Tubastatin A has significant immune modulating properties.

In conclusion, our data demonstrate that selective inhibition of HDAC6 in a lethal septic model is associated with a significant blunting of the stress responses, with attenuated thymic and bone marrow atrophy, and decreased apoptosis in splenic follicles. Our findings identify a novel mechanism that may be responsible for the survival advantage seen with Tubastatin A treatment. This study has certain limitations. We examined the overall response of the HPA axis, without identifying which specific organ and cell type is affected by the HDAC6 inhibition. Similarly, the precise mechanisms through which Tubastatin A modulates bone marrow and splenic cells need to be further investigated.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by a grant from NIH RO1 GM084127 to HBA.

Abbreviations

- ACTH

adrenocorticotropic hormone

- ANOVA

one way analysis of variance

- CLP

cecal ligation and puncture

- CRH

corticotropin-releasing hormone

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- ELISA

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

- HATs

histone acetyltransferases

- HDAC

histone deacetylase

- HDACI

HDAC inhibitors

- HIF

hypoxia-inducible factor

- HPA

hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal

- HSP

heat shock protein

- H&E

Hematoxylin and Eosin

- ICU

intensive care unit

- IHC

Immunohistochemistry

- IRAK1

interleukin-1 receptor associated kinase 1

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- SAHA

suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

Footnotes

Data presented at the 9th Annual Academic Surgical Congress in San Diego, CA (February, 2014).

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Boomer JS, To K, Chang KC, Takasu O, Osborne DF, Walton AH, et al. Immunosuppression in patients who die of sepsis and multiple organ failure. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 2011;306:2594–605. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chrousos GP. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and immune-mediated inflammation. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1351–62. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199505183322008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Savino W, Dardenne M. Neuroendocrine control of thymus physiology. Endocr Rev. 2000;21:412–43. doi: 10.1210/edrv.21.4.0402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hiramatsu M, Hotchkiss RS, Karl IE, Buchman TG. Cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) induces apoptosis in thymus, spleen, lung, and gut by an endotoxin and TNF-independent pathway. Shock. 1997;7:247–53. doi: 10.1097/00024382-199704000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tokoyoda K, Egawa T, Sugiyama T, Choi BI, Nagasawa T. Cellular niches controlling B lymphocyte behavior within bone marrow during development. Immunity. 2004;20:707–18. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maxime V, Siami S, Annane D. Metabolism modulators in sepsis: the abnormal pituitary response. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:S596–601. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000279097.67263.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schwartzman RA, Cidlowski JA. Glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis of lymphoid cells. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1994;105:347–54. doi: 10.1159/000236781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zou H, Wu Y, Navre M, Sang BC. Characterization of the two catalytic domains in histone deacetylase 6. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2006;341:45–50. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.12.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aldana-Masangkay GI, Sakamoto KM. The role of HDAC6 in cancer. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2011;2011:875824. doi: 10.1155/2011/875824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rivieccio MA, Brochier C, Willis DE, Walker BA, D'Annibale MA, McLaughlin K, et al. HDAC6 is a target for protection and regeneration following injury in the nervous system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:19599–604. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907935106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Butler KV, Kalin J, Brochier C, Vistoli G, Langley B, Kozikowski AP. Rational design and simple chemistry yield a superior, neuroprotective HDAC6 inhibitor, tubastatin A. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2010;132:10842–6. doi: 10.1021/ja102758v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rittirsch D, Huber-Lang MS, Flierl MA, Ward PA. Immunodesign of experimental sepsis by cecal ligation and puncture. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:31–6. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Billard MJ, Gruver AL, Sempowski GD. Acute endotoxin-induced thymic atrophy is characterized by intrathymic inflammatory and wound healing responses. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17940. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tinsley KW, Grayson MH, Swanson PE, Drewry AM, Chang KC, Karl IE, et al. Sepsis induces apoptosis and profound depletion of splenic interdigitating and follicular dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2003;171:909–14. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.2.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao T, Li Y, Liu B, Liu Z, Chong W, Duan X, et al. Novel pharmacologic treatment attenuates septic shock and improves long-term survival. Surgery. 2013;154:206–13. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Y, Alam HB. Creating a pro-survival and anti-inflammatory phenotype by modulation of acetylation in models of hemorrhagic and septic shock. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2012;710:107–33. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-5638-5_11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Imam AM, Jin G, Duggan M, Sillesen M, Hwabejire JO, Jepsen CH, et al. Synergistic effects of fresh frozen plasma and valproic acid treatment in a combined model of traumatic brain injury and hemorrhagic shock. Surgery. 2013;154:388–96. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2013.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Y, Liu B, Fukudome EY, Kochanek AR, Finkelstein RA, Chong W, et al. Surviving lethal septic shock without fluid resuscitation in a rodent model. Surgery. 2010;148:246–54. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Valenzuela-Fernandez A, Cabrero JR, Serrador JM, Sanchez-Madrid F. HDAC6: a key regulator of cytoskeleton, cell migration and cell-cell interactions. Trends in cell biology. 2008;18:291–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meakins JL, Pietsch JB, Bubenick O, Kelly R, Rode H, Gordon J, et al. Delayed hypersensitivity: indicator of acquired failure of host defenses in sepsis and trauma. Ann Surg. 1977;186:241–50. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197709000-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hotchkiss RS, Swanson PE, Freeman BD, Tinsley KW, Cobb JP, Matuschak GM, et al. Apoptotic cell death in patients with sepsis, shock, and multiple organ dysfunction. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:1230–51. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199907000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ertel W, Kremer JP, Kenney J, Steckholzer U, Jarrar D, Trentz O, et al. Downregulation of proinflammatory cytokine release in whole blood from septic patients. Blood. 1995;85:1341–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Docke WD, Randow F, Syrbe U, Krausch D, Asadullah K, Reinke P, et al. Monocyte deactivation in septic patients: restoration by IFN-gamma treatment. Nat Med. 1997;3:678–81. doi: 10.1038/nm0697-678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lesur O, Roussy JF, Chagnon F, Gallo-Payet N, Dumaine R, Sarret P, et al. Proven infection-related sepsis induces a differential stress response early after ICU admission. Crit Care. 2010;14:R131. doi: 10.1186/cc9102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kanczkowski W, Alexaki VI, Tran N, Grossklaus S, Zacharowski K, Martinez A, et al. Hypothalamo-pituitary and immune-dependent adrenal regulation during systemic inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:14801–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1313945110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rothwell PM, Udwadia ZF, Lawler PG. Cortisol response to corticotropin and survival in septic shock. Lancet. 1991;337:582–3. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)91641-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Annane D, Sebille V, Troche G, Raphael JC, Gajdos P, Bellissant E. A 3-level prognostic classification in septic shock based on cortisol levels and cortisol response to corticotropin. JAMA. 2000;283:1038–45. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.8.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller L, Foradori CD, Lalmansingh AS, Sharma D, Handa RJ, Uht RM. Histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1) participates in the down-regulation of corticotropin releasing hormone gene (crh) expression. Physiol Behav. 2011;104:312–20. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jason L, Sorenson M, Sebally K, Alkazemi D, Lerch A, Porter N, et al. Increased HDAC in association with decreased plasma cortisol in older adults with chronic fatigue syndrome. Brain Behav Immun. 2011;25:1544–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2011.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Migliorati G, Pagliacci C, Moraca R, Crocicchio F, Nicoletti I, Riccardi C. Glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis of natural killer cells and cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Pharmacol Res. 1992;26(Suppl 2):26–7. doi: 10.1016/1043-6618(92)90583-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ayala A, Herdon CD, Lehman DL, DeMaso CM, Ayala CA, Chaudry IH. The induction of accelerated thymic programmed cell death during polymicrobial sepsis: control by corticosteroids but not tumor necrosis factor. Shock. 1995;3:259–67. doi: 10.1097/00024382-199504000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ashwell JD, Lu FW, Vacchio MS. Glucocorticoids in T cell development and function*. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:309–45. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang SD, Huang KJ, Lin YS, Lei HY. Sepsis-induced apoptosis of the thymocytes in mice. J Immunol. 1994;152:5014–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chatterjee S, Lardinois O, Bhattacharjee S, Tucker J, Corbett J, Deterding L, et al. Oxidative stress induces protein and DNA radical formation in follicular dendritic cells of the germinal center and modulates its cell death patterns in late sepsis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;50:988–99. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.12.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ayala A, Herdon CD, Lehman DL, Ayala CA, Chaudry IH. Differential induction of apoptosis in lymphoid tissues during sepsis: variation in onset, frequency, and the nature of the mediators. Blood. 1996;87:4261–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]