Abstract

In our previous work, we demonstrated underutilization of the AIDS Drug Assistance Program (ADAP) at an HIV clinic in Alabama. In order to understand barriers and facilitators to utilization of ADAP, we conducted focus groups of ADAP enrollees. Focus groups were stratified by sex, race, and historical medication possession ratio as a measure of program utilization. We grouped factors according to the social-ecological model. We found that multiple levels of influence, including patient and clinic-related factors, influenced utilization of antiretroviral medications. Patients introduced issues that illustrated high-priority needs for ADAP policy and implementation, suggesting that in order to improve ADAP utilization, the following issues must be addressed: patient transportation, ADAP medication refill schedules and procedures, mailing of medications, and the ADAP recertification process. These findings can inform a strategy of approaches to improve ADAP utilization, which may have widespread implications for ADAP programs across the United States.

Keywords: AIDS Drug Assistance Program, policy, qualitative, social-ecological model, utilization

Sub-optimal adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) is an all-too-familiar challenge for HIV care providers and patients. One of the many ways in which this challenge is manifest is in the underutilization of programs such as the AIDS Drug Assistance Program (ADAP), which we have demonstrated in our previous work (Godwin et al., 2011). The discovery that many program enrollees do not take full advantage of life-saving medications is in contrast to the standard of care of a lifetime of uninterrupted ART (Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents, 2008). While overcoming the challenges of strict adherence can be daunting for patients, care providers, and the health care system, the ultimate outcomes of optimal personal health, increased longevity, potential for productivity, and decreased transmission risk to others justifies individual and collective efforts to promote uninterrupted ART receipt and high adherence. Lack of treatment can be fatal, and nonadherence can lead to increased hospital stays (Sansom et al., 2008), an increased viral load, development of resistant strains of the virus, and an increase in morbidity and mortality rates (Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents, 2012). Moreover, findings from the HIV Prevention Trials Network 052 study demonstrated the prevention benefits of early ART initiation, bolstering enthusiasm for HIV treatment as a prevention approach, which is dependent upon uninterrupted ART to optimize sustained viral suppression (Cohen et al., 2011).

Recognizing the individual and public health importance of HIV treatment programs, federal legislation created the Ryan White Care Act, which included the ADAP as a prominent component, as a payer of last resort. The program supplies lifesaving ART and, in some states, other essential HIV-related medications free of charge to low-income people living with HIV who qualify for the program. All 50 states, the District of Columbia, and U.S. territories (American Samoa, Federated States of Micronesia, Guam, Northern Mariana Islands, the Republic of Marshall Islands, Republic of Palau, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands) are eligible for federal funding for ADAP. Some ADAPs may be known by different names (e.g., HDAP [HIV Drug Assistance Program]). Each state or territory is responsible for administering its program; covering each class of HIV drug on its formulary; determining the type, amount, duration, and scope of services; developing a list of covered drugs in its formulary; and establishing ADAP eligibility. These responsibilities were mandated in Title XXVI of the Public Health Service Act as amended by the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Treatment Extension Act (2009). However, state laws and administrative policies, as well as overall fiscal solvency of the state or territory, determine the rules and policies associated with these responsibilities.

One quarter of all persons engaged in HIV care in the United States are enrolled in ADAP (Bassett, Farel, Szmuilowicz, & Walensky, 2008). In 2012, the federal Ryan White budget was $2.392 billion, of which $933.3 million (38%) was allocated for ADAP (AIDS Budget and Appropriations Coalition, 2012). Despite this substantial allocation of resources, a qualitative evaluation of ADAP has not been performed to identify the factors contributing to program underutilization. There is a wealth of literature examining factors related to ART adherence, but few studies have investigated factors related to utilization of ART-supplying programs, such as ADAP. A recent article provided further information on the history and current status of ADAP in the United States and highlighted the need for qualitative evaluation of ADAP and sharing of findings across state programs (Martin, Meehan, & Schackman, 2013). Because Congress scheduled the Ryan White Act for possible reauthorization in 2013, this kind of programmatic evaluation of ADAP is needed to inform health policy and practical implementation.

A retrospective cohort study (Godwin et al., 2011) of 245 patients at the University of Alabama at Birmingham 1917 Clinic evaluated ADAP utilization measured by medication possession ratios (MPR). MPR is a calculated measure based on pharmacy refill data, calculated by dividing the total number of days of medications in a patient’s possession by the number of days in the measurement period. That study found that two of every three patients did not achieve an MPR of at least 90%, and that younger patients, non-White males, those with a past or current history of alcohol abuse, and those with poor baseline HIV surrogate markers (low CD4+ T cell count and high plasma HIV viral load) were at higher risk for underutilization. These trends were consistent with those found in other studies of non-ADAP-specific HIV-infected populations in the United States and abroad (Oh et al., 2009; Simoni et al., 2012). The risk for underutilization was shown to be higher in non-White men because they disproportionately contributed to the number of new cases (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2007).

In order to better understand contributing factors and to inform theory- and evidence-based approaches to improve ADAP utilization, we conducted focus groups, informed by the previous quantitative study (Godwin et al., 2011), with the intent of identifying patient- and clinic-level barriers and facilitators to program utilization. We organized factors according to the social-ecological model. The social-ecological model has proved useful in addressing the complexity of HIV-related prevention, access to treatment, and adherence (Latkin & Knowlton, 2005; Scanlon & Vreeman, 2013). The social-ecological model describes behavior through multiple levels of influence, classified as intrapersonal factors, interpersonal processes, institutional factors, community and structural factors, and public policy (McLeroy, Bibeau, Steckler, & Glanz, 1988). Through use of the social-ecological model, this study seeks to describe barriers and facilitators to utilization of ADAP at multiple levels of influence.

Methods

The 245 patients from the original quantitative study (Godwin et al., 2011) were considered for inclusion in the qualitative study. Among men, we stratified by race and MPR. Race was stratified as White or non-White. High-utilization groups were defined by MPR at or above 90% and low-utilization groups by an MPR below 90%. As a result of the low number of women willing or able to participate, all were included in the same focus group. In summary, the patient focus groups were: (a) White men with high utilization, (b) White men with low utilization, (c) non-White men with high utilization, (d) non-White men with low utilization, and (e) women (see Table 1). Focus groups were held in meeting rooms at the University of Alabama at Birmingham 1917 Clinic. The University of Alabama at Birmingham Institutional Review Board approved the study. Potential participants were informed that they were not required to participate in the study and that a decision not to participate would not affect the care they received at the clinic. All participants provided written, informed consent. Participants were identified in the study by a code to protect their privacy and notified that personal information from their records would not be released without written permission. Patients received refreshments and a one-time cash payment of $20 for participation.

Table 1.

Focus Group Participants by Race and ADAP Utilization

| White | Non-White | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-utilization men | 13 | 4 | 17 |

| Low-utilization men | 7 | 6 | 13 |

| Women | 3 | 2 | 5 |

| Total | 23 | 12 | 35 |

Note: ADAP = AIDS Drug Assistance Program.

Data were collected using the descriptive inquiry approach within the context of focus group interviews. The descriptive inquiry approach involves description of the phenomenon of interest with low-level interpretation of the data (Sandelowski, 2000). The descriptive inquiry approach was well suited to our study because the data, as presented by the study participants, could be used to define the ADAP experience in the context of the lives of the HIV-infected participants. Group discussions were led by an experienced moderator (L.M.) using an interview guide developed by the research team to generate discussions about the participants’ experiences with HIV medications, knowledge of ADAP, and experiences with ADAP (e.g., Tell us about your experiences with ADAP). Interview questions were broad and open-ended to allow the participants to self-determine what about each topic was relevant to them personally. Focus group discussion sessions lasted between 60 and 90 minutes; they were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim, omitting any names and identifying information.

Verbatim transcripts, observation notes, and socio-demographic forms provided the primary data for analysis. Descriptive statistics were used to describe the study sample’s sociodemographic characteristics. Content analysis was used to analyze and interpret the qualitative data. Qualitative content analysis is the analysis strategy of choice in qualitative descriptive studies (Krippendorf, 2008; Sandelowski, 2000). Qualitative content analysis is a dynamic form of analysis oriented toward summarizing the content of the data and formulating categories, themes, and patterns (Graneheim & Lundman, 2004; Krippendorf, 2008). Three investigators trained in content analysis independently coded the transcripts and grouped the findings into major themes. The investigators then met to compare coding and themes, and discrepancies were discussed until consensus was reached.

Results

Of the 245 eligible patients, 101 individuals were successfully contacted by telephone and 35 participated in the focus groups (Table 2). An additional 39 individuals were interested in the study but had scheduling conflicts. Names were assigned to participants for the purpose of analysis and reporting.

Table 2.

Participant Response Rate by Race and ADAP Utilization

| Called | Contacted | Attended | Percent Called Who Attended | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HU White men | 57 | 31 | 13 | 22.8% |

| LU White men | 39 | 19 | 7 | 17.9% |

| HU non-White men | 42 | 14 | 4 | 9.5% |

| LU non-White men | 63 | 14 | 6 | 9.5% |

| Women | 44 | 23 | 5 | 11.3% |

| Total | 245 | 101 | 35 | 14.3% |

Note: ADAP = AIDS Drug Assistance Program; HU = high-utilization; LU = low-utilization.

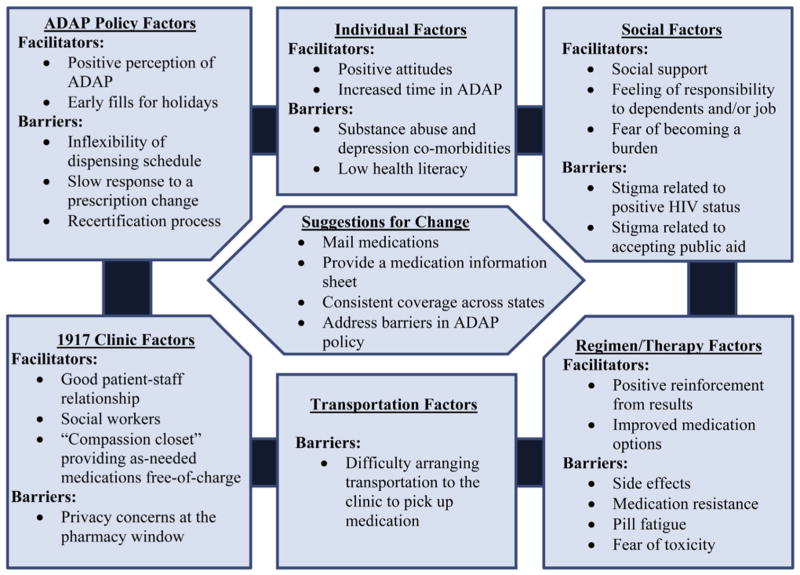

We divided the themes that emerged into six categories in accordance with the social-ecological framework. These were: individual factors (intrapersonal factors), regimen/therapy factors (intrapersonal factors), social factors (interpersonal processes), transportation factors (structural factors), 1917 Clinic factors (institutional factors), and ADAP policy factors (health care policy factors; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Factors affecting utilization of the AIDS Drug Assistance Program (ADAP) at the University of Alabama at Birmingham 1917 Clinic.

Individual Factors (Intrapersonal Factors)

Attitudes

We use the term “attitudes” to “represent a summary evaluation of a psychological object captured in such attribute dimensions as good-bad, harmful-beneficial, pleasant-unpleasant, and likable-dislikable” (Ajzen, 2001, p.28), with the assumption that these individual valuations influenced behavior. While all groups discussed attitudes, women were much more likely to identify attitudes as being significant to utilization behavior. Facilitating attitudes included an expressed desire to live, acceptance of the condition, and reframing the situation. For example, a high-utilization (HU) woman discussed her motivation to stay adherent. “But, you know, I got to realize, I want to live, and it’s what I got to do.” Jeanette, an HU patient, added, “And then I think about people who don’t have access to meds … they don’t have medications at all.” Genevieve, an HU patient, concurred,

I look at the people that have died, and the people that don’t have access to medications like we do. And, it just breaks my heart …and while I’m sitting there griping about these horse pills I have to take, I go, and I get these horse pills, and I take ‘em.

Both low-utilization (LU) and HU groups discussed the belief in being one’s own health advocate. David, an LU, White patient, stated, “You gotta show the initiative yourself too, you know.” Thom, an HU, White patient, agreed, “‘Cause I think, as in other areas of health care, we’re our own best advocates.”

Substance abuse and depression comorbidities

The presence of substance abuse and depression co-morbidities was suggested as a barrier to utilization. Specifically, drug abuse was mentioned as a comorbidity that impeded adherence to ART. Anna, an LU patient, observed, “They didn’t take it properly, or they didn’t take it at all, ‘cause, you know, the drug abuse is more important.” Depression was a commonly cited comorbidity attributed to lapses in adherence. LU groups discussed depression as a current barrier and HU groups discussed depression as a past barrier. Jerald, an HU, non-White patient, described his experience: “You know, it got to that point, and I fell into a real bad, uh, depression stage, where it’s just like, I don’t, I don’t even care, you know. But I talked to mental health.”

Health literacy

While not explicitly discussed by the focus groups, discussions emerged indicating that health literacy may have been a contributing factor to program utilization. For example, the LU, White, male groups discussed the erroneous belief that the presence of side effects indicated that the drug was not effective. Maurice, an LU, White patient, commented, “Are they working, or not? Because sometimes, you think you get a side effect, like the sweating, I found. Well, I asked my doctor, ‘Are my meds working?”‘ LU men also indicated that they did not fully understand how the ADAP system operated and did not have full knowledge of the resources available to them through the program and through social workers.

Time enrolled in ADAP

Both HU groups discussed the difficulty of navigating the program and system when they were first introduced to ADAP, suggesting that increased time enrolled in ADAP was a facilitating factor. Leo, an HU, non-White patient, stated, “After I got the hang of it, it’s improved.” Joe, an LU patient, commented,

And there’s a lot of us that have been coming here for years, that have, know this, know how the system, and know how things work, but there’s so many, who are you know … don’t know, especially new people, coming in.

Regimen/Therapy Factors (Intrapersonal Factors)

Side effects

All focus groups discussed side effects as a significant barrier to utilization. LU groups were much more likely to discuss the severity of current side effects and HU groups were more likely to discuss side effects in the past tense. Russell, an LU, non-White patient, said,

You know, I can go good for an hour or 2, then, depends on what we’re doing but, you know, the next day I might not … I might be laid out on the couch or something … a lot of people don’t understand … that, you know, a lot of it has to do with the medications.

Genevieve, an HU patient, described her first experience with HIV medications: “They made me sick. I didn’t like them. I would puke every day. So, you know, they had to test me, and test me, and test me, to see what would fit.” Jerald, an HU, non-White patient, listed past side effects, “And that was the worst thing, the diarrhea, umm, nausea, uh, and I didn’t have an appetite.” He added, “But now, it’s so much better.” Leo, an HU, non-White patient, also contributed, saying,

It was so bad the first time that uh, I left home at 3 o’clock in the morning, …and I live so, at the time, I live so far out …to catch the bus to come down here. And it was like, burning.

Maurice, an LU, White patient, noted, “Yeah, I knew a lot of people, well not a lot of people, well I can, at least two people, who, who don’t take their medications because of side effects.”

Positive reinforcement

All of the groups also discussed positive reinforcement from laboratory results to continue or improve utilization. Specifically, individuals discussed CD4+ T cell counts and indicated that an undetectable viral load was the main goal of utilization. Nick, an LU, White patient, cited one clinic visit: “I come up the next month, he said, ‘I ain’t even need to see you now. Your CD4 count is over the limit. You’re, you’re undetectable, so man, get out of my office.’ I love that.”

Improved medication options

A commonly discussed factor was the improvement of ART medications in recent years, which has made utilization easier; these improvements included decreased side effects, smaller size of pills, and a reduced number of pills. Jeanette, an HU patient, compared taking the combination pills to “taking a multi-vitamin” and noted, “I don’t have no side-effects.” She added, “It helps people stay on schedule.” Paul, an HU, White patient, commented, “I’ve been HIV positive since 1994 and I’m ecstatic that there’s a one-pill-a-day medication now.”

Medication resistance

LU groups discussed resistance to medication as a barrier to utilization. Medication resistance was discussed as leading to more complicated regimens, making adherence more difficult. Joe, an LU, non-White patient, explained,

There was Atripla that they said I might be resistant to … right after that, everything changed, medication wise. And then, it seems like it’s been, you know, the side effects that I had from the new medication. It took a while to figure out what was going on. And then I started taking other medications to correct the side effects. And so then I was having stuff that was happening from it, and it was just like a snowball.

Pill fatigue

Women also discussed pill fatigue as a barrier. Mary, an HU patient, emphasized, “Yeah, I, I do, I do guys, I get tired of dropping pills.” Her statement was met by a chorus of agreement within the women’s group.

Fear of toxicity

LU, non-White men discussed fear of toxicity as a barrier. Carl, an LU, non-White patient, commented, “I couldn’t take it, after so many years, I just said, ‘Hey …You know, I’m toxic. I’m toxic’.”

Social Factors (Interpersonal Factors)

Stigma

Women and both non-White male focus groups discussed social stigma as a barrier to utilization, expressing fear that others would discover their HIV status through possession of medication as well as receiving care. Darius, an HU, non-White patient, explained, “It was a struggle for me, to get into, uh, just taking it, the stigmatization of going with it.” Dot, an LU patient, expressed the fear that, “I didn’t want to get repercussions, of Mommy has HIV” and “we can’t go over to their house.” Charles, an LU, non-White patient, commented, “The stigma is the worst part of the whole damn disease.” Additionally, women discussed a perceived negative stigma from taking public assistance. Anna, an LU patient, discussed getting on ADAP despite having insurance:

But my co-pays would have been so out of the world. And for me, it hurt, because I was full time employed, I’m working, I have insurance, and now you’re telling me I have to accept charity, that’s the way I took it right there, and it hurt … But I needed it. So, you know, I’m grateful for that.

Social support

Women were more likely to discuss social support as a facilitator to utilization. Specifically, women cited support from family and from their significant others as helpful in utilization. Mary, an HU patient, cited a discussion about pill fatigue with her father. “He said, ‘Do you want to live, or do you want to die?”‘ Linda, an HU patient, supported her significant other, saying, “I take mine, I make sure he takes his.” HU, non-White men discussed support from friends as a facilitator to utilization. Jerald, an HU, non-White patient, said, “I mean, I used to say, I would tell my friends, ‘I’m dying with this,’ and it took a real good friend of mines to say, ‘No, you’re living with it.”‘

Women were more likely to discuss a feeling of responsibility to others as a facilitator to utilization

Women listed responsibility for dependents and a sense of responsibility in their places of work as important factors. Mary, an HU patient, revisited the conversation with her father: “And he told me, he said, ‘You know you got kids.’ They fi’nna graduate [fixing to graduate]. I mean, I didn’t want to hear that at the time.”

Fear of becoming a burden

HU, non-White men discussed the fear of becoming a burden on their families as motivation to stay adherent. Jerald, an HU, non-White patient, explained,

And now I’m at home, and I’m saying, “Wait a minute, I didn’t come home to die.” You know what I’m saying? And be a burden on my family or something, right? So umm, I just uh corrected some things.

Transportation Factors (Structural Factors)

Women and both male non-White groups discussed transportation as a significant barrier to utilization. Individuals commented that it was difficult to arrange transportation due to cost, time, and distance, especially for those who lived outside of Jefferson County, where the 1917 Clinic is located. The women’s group was in large agreement that transportation was a significant barrier, citing, “I don’t really have funds to catch the bus, you know,” “I have to get gas vouchers,” “I live a long way away,” and “You have to come pick up your medicine different days than your appointments.” Genevieve, an HU patient, stated, “I just can’t get here, and I may miss a day or 2 of medicine.”

1917 Clinic Factors (Institutional Factors)

Patient-staff relationship

All groups strongly believed that the 1917 Clinic had good patient–staff relationships and that these relationships were highly supportive of ADAP utilization. Similarly, all groups were happy with the clinic’s pharmacy staff. Women and HU, non-White men specifically cited the patient-provider relationship as a facilitator to utilization. Jerald, an HU, non-White patient, stated, “I’ma tell you honestly. When I came here, and it’s, I been home almost 2 years, I was really shocked, impressed, and relieved.” Leo, an HU, non-White patient, added, “I haven’t had not one negative experience here.” Jerald, an HU, non-White patient, continued, “It was real easy to talk to my doctor … it was the doctors made it real easy.”

Social workers

All groups also strongly believed that the help from social workers was a significant factor in high ADAP utilization. Nearly all groups discussed social workers as instrumental in obtaining non-HIV medications not available through ADAP in Alabama. The women’s group was unanimous in the necessity of social workers, with four different participants saying, “I couldn’t live without my social worker,” “They go to bat for me, I’m telling you,” “They’re amazing,” and “They go up and beyond.” The LU White male group concurred, saying, “Thumbs up,” “They’re always on their job,” and “They bend over backwards for you.” LU, non-White men specifically indicated a lack of knowledge of resources provided by social workers, which the moderator was able to clarify. All groups cited social workers as valuable in navigating the ADAP system, especially concerning medication changes and the re-certification process.

As-needed medication services

The clinic’s “compassionate-use closet” supplied medications to serve as a bridge until patients could access medication through more sustainable mechanisms, such as ADAP and patient assistance programs. The closet was stocked with a variety of medications that, for a variety of reasons, were not dispensed or picked up by program enrollees. The use of a compassionate medication closet is sanctioned by the Alabama Department of Public Health for use with ADAP-approved patients. The closet was restricted to include only medications that were dispensed from the ADAP contract pharmacy, shipped to the clinic, but never picked up by clinic patients. Under the control of on-site licensed pharmacists, the closet was maintained with the same quality standards as the on-site retail pharmacy. Women discussed these compassion medications as being helpful for when medications were not covered under ADAP. Mary, an HU patient, explained, “There’s a couple of medications that, uh, don’t, uh, are not qualified under Ryan White or ADAP … and compassion [provides] for that.” Both non-White groups and LU, White males discussed compassion medications as facilitators to utilization, offering flexibility when medications did not arrive as scheduled. Charles, an LU, non-White patient, noted, “It took about a month or 2 before I got the new drugs in. They had to use a lot of in compassion stuff.”

Privacy concerns

LU, non-White males discussed privacy concerns at the pharmacy window, specifically the fear that others might overhear discussions with the pharmacist, as a possible barrier to utilization. Joe, an LU, non-White patient, noted, “And there’s really no confidentiality to me, right there at that hallway window. ‘Cause if you’re sitting in the chair, you can hear what the people at the window are talking about, what medications they’re receiving.”

ADAP Policy Factors (Health Care Policy Factors)

Positive perception of ADAP

All groups had an overwhelmingly positive perception of ADAP. All groups discussed ADAP as a resource to keep medication costs from becoming prohibitive and, as such, as a resource for staying healthy. Dan, an HU, White patient, noted, “And this really is, is what provides a safety net where you don’t have to make such hard, hard decisions about do I purchase $3,000 worth of medication this month, or do I do other things? Like eat.” HU, non-White men discussed ADAP as relief from stress from worrying about medications and expressed a desire to get off ADAP in the future so someone else could use it. Leo, an HU, non-White patient, stated,

I’m hoping and praying I can get a fulltime job. I know times are bad. And I know that medicine is expensive. I may sound selfish for saying this, I really hope that one day I can get to that point where I can … remove myself from it, to give somebody else an opportunity that really needs it.

Early prescription refills

Women and LU, White men discussed appreciation at the ability to get medications ahead of time for holidays and vacations. HU, White males also perceived that Alabama had a better ADAP program than some bordering states, such as Mississippi and Florida. Nick, an LU, White male, noted, “I ended up moving to Florida and it took me forever. The doctor decided to let me try this Atripla, but I never could get it … I never got it so, umm, I moved here to Alabama.”

Medication dispensing schedule

Negative perceptions of ADAP were also discussed as barriers to utilization. A common complaint was the inflexibility of the medication-dispensing schedule. Dot, an LU patient, explained that “They’re not gon’ give you that medicine until those 30 days,” referring to the 30-day dispensing schedule. She added, “‘Cause I may run out, maybe 3 or 4 days and my appointment is today, they won’t give me my medicine.” Jeanette, an HU patient, commented, “I don’t think that’s fair.” Doug, a LU, White patient, also noted, “Sometimes I might runs short, and I have to come up, and they might not be in until the next Thursday or so.”

Prescription changes

LU, non-White males and both White male groups discussed the slow ADAP response to a change in prescription as influencing utilization. They pointed to experiences when they were not able to register with ADAP before the 30-day dispensing window and later found themselves without medication until the next 30-day cycle. Benny, an LU, non-White patient, recalled, “They took me off the current HIV medication and put me on a new one. I had to wait 3½ weeks to get that new medication.” Women and LU, White males mentioned that, on occasion, medication did not arrive as scheduled. LU, non-White men and both HU and LU White men discussed a perception of waste in ADAP, specifically related to the slow ADAP response to medication changes that resulted in previously prescribed medications being needlessly delivered to the pharmacy. For example, Carl, an LU, non-White patient explained, “There’s a lot of times … they’ve given me so much medicine and I’m hard headed, and, umm, I feel like it’s wasteful, and I, I don’t need it. I tell ‘em I don’t really want it.” Both LU non-White and White men commented that other states have better ADAP programs, specifically California and Vermont. Nick, an LU White patient, commented, “I just wanted to say that when I was living in Vermont, it, it took approximately a week to get medication. I mean, it was just umm, just like (snapping fingers) that.”

Recertification process

The recertification process was widely discussed as a barrier to remaining in the ADAP program and thus remaining adherent. The recertification process involved garnering, maintaining, and reproducing numerous documents (including the release of demographic data and some medical records, proof of state residency, proof of total gross income, proof of applicant’s enrollment in private or public insurance) and proof of enrollment in Medicaid Transitory housing, limited literacy skills, stigma and privacy concerns also complicated, and sometimes deterred patients from readily providing the required information.

Individuals in LU, non-White groups and HU, White groups mentioned that they had been dropped from ADAP in the past without warning. Leo, an HU, non-White patient, recalled, “And when I went to the pharmacy to pick up my meds, suddenly, I had been dropped, and they were just, there was no explanation, and I had no idea.” LU, non-White men commented that the recertification process could be too taxing for those with diminished physical and/or mental capacity. Russell, an LU, non-White patient, commented,

It just seems a little complicated, I mean, I think most people here have the mental facilities to be able to get a denial letter together, and your social security benefit letter together, and this together, and that together, it, it is a little trying. But for those people who don’t have the, the, physical capability, or the mental capability to do that, is, is it’s problematic.

HU, non-White men commented that they had experienced paperwork being lost before and also noted that the process often required multiple submittals. For example, Darius, an HU, non-White patient, explained, “And I know the social worker does all they can, to submit everything. And then once they submit everything, it just get lost … they didn’t have the recertification, the medicine wasn’t in.” HU, White men discussed the process as often being stressful. Garett, an HU, White patient, commented, “Do it earlier, rather than later … because there are mail delays, there are processing delays, there are errors that are made, and you want to ensure that you’re giving yourself enough wiggle room.” However, women mentioned an 800 number provided by ADAP that they found helpful. Jeanette, an HU patient, noted, “To me it’s gotten easier. The last time, I had to, they gave me a 800 number, and I could call and give them certain information. That was a lot easier to me.” Highly adherent men and both White male groups discussed the process as being smooth and/or easy once an individual either became experienced with the process or had the aid of a social worker. Larry, an HU, White patient, commented,

You’ll want to pull on board as a partner, with one of the social workers … because they have the ability to, to really act as the, the quarterback, ensuring that all the information, that you need to provide, is, is addressed and it’s all sent.

Suggestions for Change

Mailing medications

The idea to mail medications directly to individuals was suggested by women and HU, non-White men. Jeanette, an HU patient, asked, “I wonder if they ever thought about mailing it, I mean, would that ever be an option?” LU, non-White men suggested mailing the medications to pharmacies closer to individuals, especially for those who lived outside the county where the clinic was located. Charles, an LU, non-White patient, commented, “It would be sweet if, once it comes in, if they’re, if they could drop ship it to your local pharmacy.”

Medication information sheet

HU, White men suggested providing individuals with information sheets to help keep track of medications. Matt, an HU, White patient, recalled,

And I had some, I had, actually went back and wrote out something for myself, out of 21 medications, I can’t keep up with it. You know and then when it comes times for me to figure out what I’m supposed to get, I’m like, okay, well this one has been coming from ADAP.

Consistent coverage across states

HU, White men also suggested that, as a policy change, ADAP needed to become a more cohesive program across states. Specifically, they wanted coverage to remain in place when moving between states. Larry, an HU, White patient, recalled, “What I recognize when I moved into this state, was that I was, my ADAP, umm, coverage, did not transfer with me. I had to re-apply. And I was put at the bottom of the list.” Benny, an LU, non-White patient, commented, “It needs to be national wide … If it’s available in New York, it ought to be available in Alabama.”

Discussion

Strengths of qualitative analysis include the ability to add further meaning and context to quantitative results. From our focus groups, we discovered that while quantitative data provided a description of the demographics of patients most at risk for underutilization, the qualitative results provided a possible rationale for why these patients were at more risk than others. Herein, we discuss divergent factors related to a higher underutilization risk for younger patients and non-White male patients. Furthermore, depression and depressive symptoms emerged as an additional factor that might be predictive of underutilization risk.

Divergent Factors Related to Age

The quantitative study conducted at the 1917 Clinic indicated that younger males were more at risk of underutilization of ADAP (Godwin et al., 2011). From focus group discussion, we discovered that the number of years in ADAP and/or treatment may be a more significant measure than age and may be the underlying reason that age provided a protective effect; this was consistent with previous research that found that older age was protective for HIV medication utilization but not necessarily causally linked (Barclay et al., 2007). Older age may be protective specifically to ADAP utilization due to the increased likelihood of having been in ADAP longer and thus, indicative of a better understanding of how to navigate the system more effectively. We suggest further examination of demographic data to determine whether number of years in ADAP and/or treatment is a more accurate correlating measure for utilization when compared to age. The apparent age disparity may be addressed by exploring methods to increase knowledge among LU patients regarding ADAP and resources available through the clinic and social workers.

Divergent Factors Related to Non-White Male Status

Quantitative results showed that non-White males were at more risk than other demographics for under-utilization of ADAP. We discovered from the focus groups that non-White men had different concerns than White men regarding medication utilization. These concerns included individual factors, such as drug abuse (which was also a factor correlated with higher risk of underutilization in the quantitative results), social factors such as stigma, structural factors such as transportation, and institutional factors such as fear for privacy at the pharmacy window. These themes may serve as a guide for providers to address utilization disparities between White and non-White men.

First, due to divergent concerns expressed regarding drug abuse, we suggest identifying whether drug abuse is more prevalent in the non-White male population. Research has suggested that successful substance abuse treatment significantly increases ART adherence (Hicks et al., 2007). If drug use is not more prevalent in this population, it may be worthwhile to explore why non-White men cited it as an explicit concern, while White men did not. Second, social stigma was an additional divergent concern for non-White males as compared to White males. Stigma has been well documented in the literature as a barrier to care (Reif, Golin, & Smith, 2005; Vervoort, Borleffs, Hoepelman, & Grypdonck, 2007). Studies have suggested that community outreach and education may help to alleviate stigma in non-White populations, especially in African American populations (Foster, 2007; Morin et al., 2002). Additionally, the divergent concern among non-White men about privacy at the pharmacy window may be related to the divergent concern related to stigma. We suggest that clinics reexamine the physical setup of the pharmacy windows to address whether any improvements can be made to alleviate fear of a privacy breach. Finally, transportation was a concern expressed by non-White men. The literature has suggested that transportation is a greater barrier for those in rural areas as compared to those in urban areas (Reif et al., 2005). This is consistent with what we heard in our focus groups: those living outside of the county had a greater concern about transportation issues. However, it did not explain why this was a divergent concern for non-White men. It would be worthwhile to explore whether non-White men constituted a larger proportion of the rural population at the clinic and determine whether this is actually a rural concern rather than an ethnic divide, or whether another factor may be involved, such as stigma related to using public transportation or the inability to effectively navigate the Birmingham metro area public transportation system, which can often be unreliable.

Depression and Depressive Symptoms as a Predictive Factor for LU

Depression and depressive symptoms were a commonly discussed theme among all focus groups. The relationship between depression and depressive symptoms with low utilization of HIV medication has been well documented in the literature (Gonzalez et al., 2004; Reynolds et al., 2004). Notably, women were more likely to discuss social support and individual attitudes as important factors in utilization compared to men. Research has found that social support and coping skills are positive predictors of HIV medication adherence in both women and men, including those with depressive symptoms (Gonzalez et al., 2004; Vyavaharkar et al., 2007). Related areas of research include explorations of ways to support patients without otherwise strong social support networks through additional relationships, such as peer mentors or peer navigators. Providers might increase adherence through recruitment of LU patients into these support services if determined to be beneficial.

Limitations

This study is limited in its generalizability. We note, however, that the primary goal of qualitative research is not generalizability, but rather depth of understanding of phenomena. The male-to-female ratio of the focus groups (86% male, 14% female) mirrored the eligible population (82% male, 18% female). The ratio of non-White participants to White participants was a limitation of the study. Whereas the study aimed to recruit 55% non-White participants and 45% White participants to mirror the clinic population, the study successfully recruited 34.3% non-White participants and 65.7% White participants. White men had a higher participation rate than minority men. Finally, the sample population was limited in that it constituted a convenience sample.

Conclusion

Low utilization of ART medications in ADAP enrollees at the 1917 Clinic was found to relate to multiple levels of influence and, thereby, may be amenable to multiple levels of intervention. Notably, a variety of barriers and facilitators to ADAP utilization were identified between men and women, and between White and non-White men, with implications for practice and policy. Although the limitations of the study preclude generalizing results to a broader population or to ADAP programs in other states, the facilitators and barriers for medication utilization were not unique to our clinic, as we noted in our discussion. As such, our results may provide a framework for similar qualitative research by other ADAP-affiliated provider practice sites. Issues introduced in focus groups by patients in our study indicated high-priority needs for ADAP policy and program administrators. Policy should be evaluated concerning matters related to transportation, inflexibility of ADAP medication refill schedules, mailing of medications, and complexities of the ADAP re-certification process. Ultimately, by increasing utilization of ADAP and promoting sustained viral suppression, we expect to observe enhanced personal health, a decrease in HIV-related comorbidities and mortality, and reductions in HIV transmission.

Key Considerations.

To help increase AIDS Drug Assistance Program (ADAP) utilization, nurses in HIV care need to recognize that younger enrollees, non-White men, and patients with depression are at higher risk for underutilization and probably have lower corresponding rates of ART adherence.

Nurses should help patients overcome the individual, regimen, transportation, and clinic factors that serve as barriers to full ADAP utilization, including addressing intrapersonal factors such as stigma and navigating the health care system.

Nurses in HIV care can advocate for important policy and administrative changes to decrease system-level and administrative barriers within ADAP.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the Lister Hill Center for Health Policy.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors report no real or perceived vested interests that relate to this article that could be construed as a conflict of interest.

References

- AIDS Budget and Appropriations Coalition. FY 2013 appropriations for federal HIV/AIDS programs. 2012 Aug; Retrieved from http://www.aidsunited.org/policyadvocacy/resources/factsheets/

- Ajzen I. Nature and operation of attitudes. Annual Review of Psychology. 2001;52:27–58. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barclay TR, Hinkin CH, Castellon SA, Mason KI, Reinhard MJ, Marion SD, Durvasula RS. Age-associated predictors of medication adherence in HIV positive adults: Health beliefs, self-efficacy, and neurocognitive status. Health Psychology. 2007;26(1):40–49. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.1.40. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.26.1.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassett IV, Farel C, Szmuilowicz ED, Walensky RP. AIDS Drug Assistance Programs in the era of routine HIV testing. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2008;47(5):695–701. doi: 10.1086/590936. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/590936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV/AIDS surveillance report, 17. 2007 Jun; Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/statistics_2005_HIV_Surveillance_Report_vol_17.pdf.

- Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, Fleming TR. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;365(6):493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster PH. Use of stigma, fear, and denial in development of a framework for prevention of HIV/AIDS in rural African American communities. Family & Community Health. 2007;30(4):318–327. doi: 10.1097/01.FCH.0000290544.48576.01. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.FCH.0000290544.48576.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godwin NC, Willig JH, Nevin CR, Lin H, Allison J, Gaddis K, Raper JL. Underutilization of the AIDS Drug Assistance Program: Associated factors and policy implications. Health Services Research. 2011;46(3):982–995. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01223.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01223.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez JS, Penedo FJ, Antoni FH, Durán RE, McPherson-Baker S, Ironson G, Schneiderman N. Social support, positive states of mind, and HIV treatment adherence in men and women living with HIV/AIDS. Health Psychology. 2004;23(4):413–418. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.4.413. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.23.4.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today. 2004;24:105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks PL, Mulvey KP, Chander G, Fleishman JA, Josephs JS, Korthuis PT, Gebo KA. The impact of illicit drug use and substance abuse treatment on adherence to HAART. AIDS Care. 2007;19(9):1134–1140. doi: 10.1080/09540120701351888. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09540120701351888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorf K. Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Latkin CA, Knowlton AR. Micro-social structural approaches to HIV prevention: A social ecological perspective. AIDS Care. 2005;17(Suppl 1):S102–S113. doi: 10.1080/09540120500121185. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09540120500121185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin EG, Meehan T, Schackman BR. AIDS Drug Assistance Programs: Managers confront uncertainty and need to adapt as the Affordable Care Act kicks in. Health Affairs. 2013;32(6):1063–1071. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0123. http://dx.doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, Glanz K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Education Quarterly. 1988;15(4):351–377. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500401. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/109019818801500401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin SF, Sengupta S, Cozen M, Richards TA, Shriver MD, Palacio H, Kahn JG. Responding to racial and ethnic disparities in use of HIV drugs: Analysis of state policies. Public Health Reports. 2002;117(3):263–272. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3549(04)50160-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh DL, Sarafian F, Silvestre A, Brown T, Jacobson L, Badri S, Detels R. Evaluation of adherence and factors affecting adherence to combination antiretroviral therapy among White, Hispanic, and Black men in the MACS Cohort. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2009;52(2):290–293. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181ab6d48. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181ab6d48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the use of anti-retroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents. 2008 Nov 3; Retrieved from http://www.aidsinfo.nih.gov/ContentFiles/AdultandAdolescentGL.pdf.

- Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents. 2012 Mar 27; Retrieved from http://www.aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/lvguidelines/adultandadolescentgl.pdf.

- Reif S, Golin CE, Smith SR. Barriers to accessing HIV/AIDS care in North Carolina: Rural and urban differences. AIDS Care. 2005;17(5):558–565. doi: 10.1080/09540120412331319750. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09540120412331319750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds NR, Testa MA, Marc LG, Chesney MA, Neidig JL, Smith SR, Robins GK. Factors influencing medication adherence beliefs and self-efficacy in persons naive to antiretroviral therapy: A multicenter, cross-sectional study. AIDS and Behavior. 2004;8(2):141–150. doi: 10.1023/B:AIBE.0000030245.52406.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan White HIV/AIDS Treatment Extension Act. (2009). Retrieved from http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-111publ87/html/PLAW-111publ87.htm

- Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Research in Nursing & Health. 2000;23:334–340. doi: 10.1002/1098-240x(200008)23:4<334::aid-nur9>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sansom SL, Anthony MN, Garland WH, Squires KE, Witt MD, Kovacs AA, Wohl AR. The costs of HIV antiretroviral therapy adherence programs and impact on health care utilization. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2008;22(2):131–138. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.0216. http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/apc.2006.0216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scanlon ML, Vreeman RC. Current strategies for improving access and adherence to antiretroviral therapies in resource-limited settings. HIV/AIDS. 2013;5:1–17. doi: 10.2147/HIV.S28912. http://dx.doi.org/10.2147/HIV.S28912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoni JM, Huh D, Wilson IB, Shen J, Goggin K, Reynolds KR, Liu H. Racial/ethnic disparities in ART adherence in the United States: Findings from the MACH14 Study. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2012;60(5):466–472. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31825db0bd. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0b013e31825db0bd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vervoort SC, Borleffs JC, Hoepelman AI, Grypdonck MH. Adherence in antiretroviral therapy: A review of qualitative studies. AIDS. 2007;21(3):271–281. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328011cb20. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0b013e328011cb20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vyavaharkar M, Moneyham L, Tavakoli A, Phillips KD, Murdaugh C, Jackson K, Meding G. Social support, coping, and medication adherence among HIV-positive women with depression living in rural areas of the southeastern United States. AIDS Patient Care & STDs. 2007;21(9):667–680. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.0131. http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/apc.2006.0131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]