Abstract

Objective

Atherosclerosis is a chronic inflammatory and immune vascular disease, and clinical and experimental evidence has indicated an important role of complement activation products, including the terminal membrane attack complex (MAC), in atherogenesis. Here, we investigated whether complement inhibition represents a potential therapeutic strategy to treat/prevent atherogenesis using CR2-Crry, a recently described complement inhibitor that specifically targets to sites of C3 activation.

Methods and Results

Previous studies demonstrated that loss of CD59 (a membrane inhibitor of MAC formation) accelerated atherogenesis in Apoe deficient (Apoe−/−) mice. Here, both CD59 sufficient and CD59 deficient mice in an Apoe deficient background (namely, mCd59ab+/+/Apoe−/− and mCd59ab−/−/Apoe−/−) were treated with CR2-Crry for 4 and 2 months respectively, while maintained on a high fat diet. Compared to control treatment, CR2-Crry treatment resulted in significantly fewer atherosclerotic lesions in the aorta and aortic root, and inhibited the accelerated atherogenesis seen in mCd59ab+/+/Apoe−/− and mCd59ab−/−/Apoe−/− mice. CR2-Crry treatment also resulted in significantly reduced C3 and MAC deposition in the vasculature of both mice, as well as a significant reduction in the number of infiltrating macrophages and T cells.

Conclusion

The data demonstrate the therapeutic potential of targeted complement inhibition.

Keywords: Complement, complement regulation, atherosclerosis, Crry, CD59 and therapeutics

Introduction

Atherosclerosis is a chronic inflammatory and immune vascular disease. Extensive human studies indicate that complement, a key mediator of inflammation and immune responses, may play a critical role in atherogenesis1, 2. The complement system is activated by three different cascades. All pathways eventually lead to the formation of membrane attack complex (MAC). The results published by us3 and others4–6 convincingly demonstrated the anti-atherogenic role of CD59, a membrane-bound inhibitor of MAC formation, which in turn is indicative of the atherogenic role of the MAC. Specifically, we reported that in mice deficient in apolipoprotein E (Apoe), the additional loss of CD59 (mCd59ab−/−/Apoe−/−), accelerated atherosclerosis3. We also reported that over-expression of human CD59 (hCD59) (ThCD59ICAM-2/Apoe−/−), or inhibition of MAC formation, using a neutralizing anti-mC5 antibody (Ab), attenuated atherogenesis in Apoe−/− or mCd59ab−/−/Apoe−/− mice, respectively3. Lewis et al demonstrated that deficiency of C6, a necessary component for MAC formation, attenuates atherogenesis in Apoe−/− mice5. Recently, Manthey et al reported that C5a inhibition reduces atherosclerosis in Apoe−/− mice7. Although these results highlight an atherogenic role of the terminal complement pathway and the MAC, whether restriction of complement activation has any beneficial effect in the treatment/prevention of atherogenesis remains unclear3, 5.

The complement system consists of approximately 30 soluble and membrane-bound proteins, and is activated by three distinct pathways (classical, mannose-binding lectin (MBL) and alternative pathways)8. All three activation pathways converge at C3 cleavage, leading to the subsequent formation of C5 convertase. The C5 convertase then cleaves C5 to form C5b and C5a. The terminal complement activation pathway is induced initially by C5b, and results finally in the formation of the MAC8. The MAC is a macromolecular pore capable of inserting itself into cell membranes and lysing heterologous cells and pathogens8. To protect self cells from MAC damage, more than ten plasma- and membrane-bound inhibitory proteins have evolved to restrict complement activation at different stages of the activation pathways8. The principle membrane-bound inhibitors of complement in humans that are expressed on the surface of almost all cell types are decay-accelerating factor (DAF or CD55), membrane cofactor protein (MCP or CD46), and CD599. DAF inactivates the C3 (C4b2a and C3bBb) and C5 (C4b2a3b and C3bBb3b) convertases by accelerating the decay of these enzymes10, 11. MCP inactivates C3 and C5 convertases by serving as a cofactor for the cleavage of cell-bound C4b and C3b by the serum protease factor I8. CD59 restricts MAC formation by preventing C9 incorporation and polymerization in the assembling complex8. Humans have only one CD59 gene, while mice have two CD59 genes called mCd59a and mCd59b3, 12, 13. Further, in mice, complement receptor-1 related gene/protein Y (Crry) is a functional and structural analogue of human DAF and MCP14. Crry plays a critical role in the regulation of complement activation in mice since the deficiency of mouse Crry results in complement dependent fetal lethality15. Crry inhibits all three complement pathways at the central C3 activation stage.

The pharmaceutical modulation of complement activity for therapeutic purposes has been extensively investigated. Until recently, nearly all complement inhibitors investigated both in experimental models and in clinic, systemically restricted complement activity, including eculizumab, an anti-C5 mAb recently approved for the treatment of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria16. However, since complement activation products have important roles in immunity to infection17, homeostasis and tissue repair18, systemic inhibition is likely to have undesirable side effects. This may be particularly true for chronic therapeutic approaches, as may be necessary for the treatment of atherosclerosis. In this context, it has recently been shown that site-specific targeting of a complement inhibitor can obviate the need for systemic complement inhibition, and increase bioavailability and efficacy without compromising host immunity to infection19, 20. The strategy was to use a complement inhibitor linked to a complement receptor 2 (CR2) targeting moiety. Natural ligands for CR2 are iC3b, C3dg and C3d, cell-bound breakdown fragments of C3 that mark sites of complement activation. Crry targeted by means of CR2 (CR2-Crry) has been shown to be 10–20 fold more effective than Crry-Ig, a systemic counterpart, in a murine model of intestinal ischemia reperfusion injury (IRI)21. Significantly, Crry-Ig but not CR2-Crry enhanced susceptibility to infection in a mouse model of acute septic peritonitis when given at the minimum dose providing protection from intestine IRI21. Thus, targeted complement inhibition is much less immunosuppressive than systemic inhibition22 and may provide a significant potential advantage for patients suffering from complement-related chronic immune and inflammatory diseases such as atherosclerosis. However, whether these targeted complement inhibitors have any beneficial effect in the prevention of atherosclerosis has not been investigated.

Here, we report that CR2-targeted mouse complement regulator Crry protected both mCd59ab+/+/Apoe−/− and mCd59ab−/−/Apoe−/− mice against the development of atherosclerosis. Mice treated with CR2-Crry had significantly less C3b/iC3b/C3c and MAC deposition in the atherosclerotic lesion than mice treated with vehicle. These results indicate that targeted complement inhibitors may provide a novel, effective and safe approach for the treatment of atherosclerosis through the restriction of complement activation and MAC formation.

METHODS

Production and purification of CR2-Crry and measurement of its biological activity

CR2-Crry was produced and characterized as previously described19, 27. Briefly, CR2-Crry was expressed in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells transfected with plasmids encoding mouse CR2-Crry and further purified from the cultural supernatants by anti-mouse CR2 affinity chromatography19, 27. Biotin-conjugated CR2-Crry was generated by EZ-Link Sulfo-NHS-Biotinylation Kit (21425, Thermo Scientific) and the level of biotin conjugation with CR2-Crry was measured by biotin binding assay according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Equivalent amount of biotin was prepared in 1 X phosphate buffered saline (PBS) buffer as vehicle control.

Animal treatment and characterization of atherosclerotic lesions

To investigate anti-atherogenic effect of CR2-Crry, we treated six-week-old mCd59ab+/+/Apoe−/− or mCd59ab−/−/Apoe−/− mice with CR2-Crry and maintained on high fat diet (HFD) for 4 or 2 months, respectively. The selection of the treatment periods was based on our previous observation that mCd59ab−/−/Apoe−/− on HFD for 2 months and mCd59ab+/+/Apoe−/− on HFD for 4 months developed extensive atherosclerosis in both aorta and aortic root3. Briefly, mice were treated with either CR2-Crry (tail vein injection or i.v.28, 0.25mg/mouse, twice per week for 2 or 4 months) or PBS buffer (vehicle control, which does not affect complement activity19), and simultaneously fed with HFD (or atherogenic diet) (C12108; Research Diets Inc.) containing 20.1% saturated fat, 1.37% cholesterol, and 0% sodium cholate3. Harvard Medical School Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved all experimental procedures and protocols. The selection of the CR2-Crry dosing regimen was based on previously published data showing the protective effect of CR2-Crry in prolonged treatment protocol, together with data showing that CR2-Crry does not induce any anti-CR2-Crry antibodies 27, 29. To directly investigate the localization of CR2-Crry, we treated 3-month-old mCd59ab+/+/Apoe−/− mice with biotin-conjugated CR2-Crry (i.v, 0.25mg/mouse) (experimental group) or biotin (i.v, 3ug/mouse, equivalent molar amount of biotin vs. biotin-CR2-Crry) (vehicle control) twice per week for 1 month. Unlabeled CR2-Crry (i.v, 1mg/mouse, which is 4 fold higher than the dose of the biotin-conjugated CR2-Crry used) plus biotin-conjugated CR2-Crry (i.v. 0.25mg/mouse) (competitive inhibition control) were simultaneously administered twice per week for 1 month. All groups of mice were maintained on HFD for 1 month.

After fasting the mice overnight, we sacrificed the mice by CO2 asphyxiation and blood collected by heart puncture. Serum was prepared and stored at −80°C. The entire aorta was analyzed from the heart outlet to the iliac bifurcation, with Oil red-O as previously described3. Sections of the aortic roots (5 μm) were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)3. The total and Oil red-O stained area in entire aorta, and H&E stained lesion area in aortic root for each section were recorded and two independent investigators performed all measurements in a blinded fashion with respect to the origin of the coded samples.

To investigate deposition of Biotin-conjugated CR2-Crry, frozen sections (5 μm) of the aortic roots were stained with VECTASTAIN Elite avidin-biotin complex (ABC) Kit (Standard, Vector labs) following the manufacturer’s instructions and counterstained with Harris Hematoxylin for 3 min. Sections were dehydrated by passing the slides through a series of increasing alcohol concentrations.

Immunofluorescence and histology

Frozen sections of aortic root (5 μm) were stained with rat anti-mouse C3, IgG2a (clone: 3/26, Hycult Biotechnology), which recognizes mouse complement protein C3 as well as activated C3 fragments C3b, iC3b, and C3c, and rabbit anti-rat C9, which cross-reacts with mouse C9 (Kindly provided by Dr. P. Morgan, University of Wales)3. Cellular components in the atherosclerotic plaques (aortic root) were characterized by immunostaining with the following reagents: (1) rat anti-mouse CD68, IgG2a (clone: FA-1, AbD Serotec) for mononuclear phagocytes; and (2) rat Anti-mouse CD4, (Lou/WS1) IgG2a, k (clone: H129.19, BD Biosciences). All the primary antibodies were detected using corresponding fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated secondary antibodies and compared with negative controls which were stained with the secondary antibody alone. We quantified immunofluorescence and histological results from three serial sections from each mouse using Image ProPlus 6.0 software as described30. The mean of the quantitative results of three sections obtained from each mouse was used to perform the statistical analysis.

Serum lipid measurement

Serum cholesterol and triglyceride profiles were measured at the Clinical Pathology Laboratory of Children’s Hospital, Boston.

Statistical analysis

Experimental results are shown as the Mean ± s.e.m. The difference between the two groups was examined with a nonparametric Mann-Whitney test. All statistical tests with P< 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

CR2-Crry protects mCd59ab+/+/Apoe−/− and mCd59ab−/−/Apoe−/− mice against the development of atherosclerosis

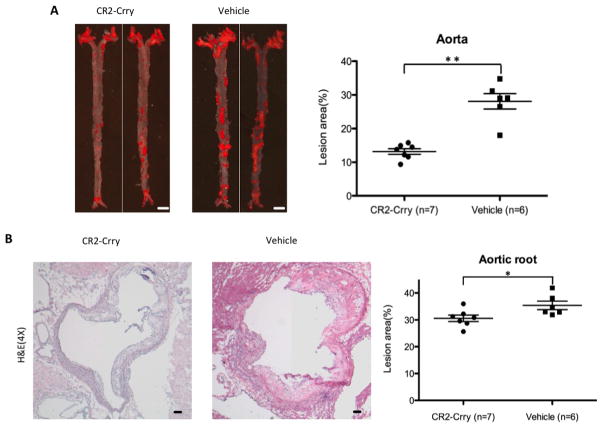

We first investigated whether CR2-Crry had any beneficial effect in protecting against atherogenesis in a CD59 sufficient background, a more physiologically relevant condition than a CD59 deficient background. We administered CR2-Crry to 6 week old mCd59ab+/+/Apoe−/− mice twice per week for 4 months and maintained the mice on HFD. Mice treated with CR2-Crry developed significantly less atherosclerosis in the aortic surface (as evaluated by en face preparation) and aortic root compared to mice treated with vehicle (Figure 1A, 1B, and supplemental figure 1). In addition, serum cholesterol levels, and serum triglyceride levels, and body weight were not significantly different between the two groups (Supplemental figure 2A). These results show that the targeted complement inhibitor CR2-Crry protects mCd59ab+/+/Apoe−/− mice against the development of atherosclerosis.

Figure 1. CR2-Crry protects against atherosclerosis in mCd59ab+/+/Apoe−/− mice.

A, Atherosclerosis analysis of en face aorta with oil red O staining in the HFD-fed mCd59ab+/+/Apoe−/− mice treated with CR2-Crry (n=7 males) or vehicle (n=6 males) for four months. Lesion area (%) is (oil red O staining area/aortic area) × 100. Scale bar: 2mm. B, H&E staining of aortic root in mCd59ab+/+/Apoe−/− mice shows that CR2-Crry treated mice have a smaller plaque than vehicle group. Lesion area (%) is (Plaque area/ventricle area) ×100. Scale bar: 100μm. *P<0.05;**P<0.005.

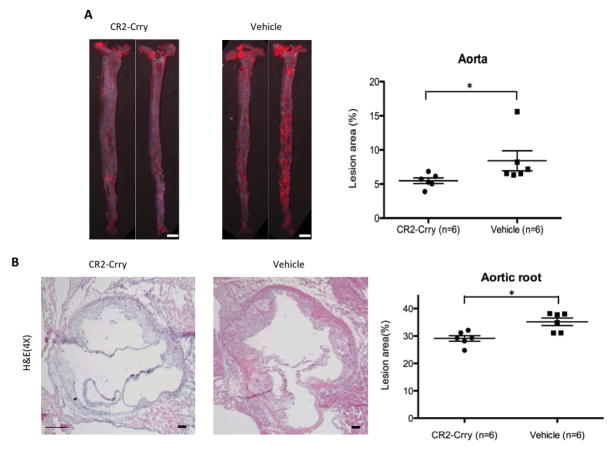

Our previous data using mCd59ab−/−/Apoe−/− mice, CD59 over-expressing transgenic mice, together with data obtained using anti-C5 Ab therapy, indicated an atherogenic role of the MAC3. Recent reports have shown that C5 cleavage and activation of the terminal pathway can occur independently of C3 activation via thrombin-mediated cleavage23. To further define the role of C3 activation in the development of the atherosclerosis occurring in mCd59ab−/−/Apoe−/− mice, we therefore investigated whether restricting complement activation at the C3 level with CR2-Crry would modulate the development of MAC-associated atherogenesis. We administered CR2-Crry to 6 week old mCd59ab−/−/Apoe−/− mice for 2 months while mice were maintained on a HFD. Compared to control treatment, CR2-Crry treatment resulted in significantly fewer atherosclerotic lesions in the aorta and aortic root, and inhibited the accelerated atherogenesis seen on the CD59 deficient background (Figures 2A–2B). Further, there were no significant differences in serum cholesterol and triglyceride levels, as well as body weight among the groups (Supplemental figure 2B). Together, these results indicate that the inhibition of complement activation at C3 level with CR2-Crry antagonizes the MAC-accelerated atherogenesis in CD59 deficient mice. The different periods of CR2-Crry treatment in CD59-sufficient and CD59-deficient mice precluded us from directly comparing the anti-atherogenic effects of CR2-Crry in both groups.

Figure 2. Inhibition of C3 activation with CR2-Crry protects against atherosclerosis in mCd59ab−/−/Apoe−/− mice.

A, Atherosclerosis analysis of en face aorta with oil red O staining in the HFD-fed mCd59ab−/−/Apoe−/− mice treated with CR2-Crry (n=6 with 3 males and 3 females) or vehicle (n=6 with 2 males and 4 females) for two months. Lesion area (%) is (oil red O staining area/aortic area) × 100. Scale bar: 2mm. B, H&E staining of aortic root in mCd59ab−/−/Apoe−/− mice shows that CR2-Crry treated mice have a smaller plaque than vehicle group. Lesion area (%) is (H&E staining area/ventricle area)×100. Scale bar: 100μm.*P<0.05;**P<0.005.

CR2-Crry-treated mice have significantly less MAC and C3 deposition on the atherosclerotic lesion than vehicle-treated mice

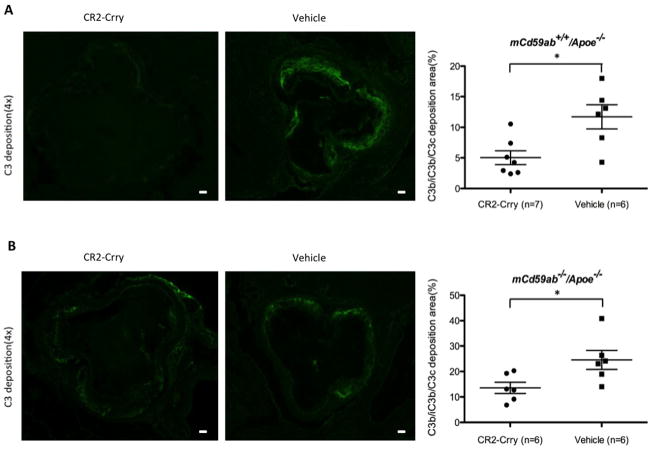

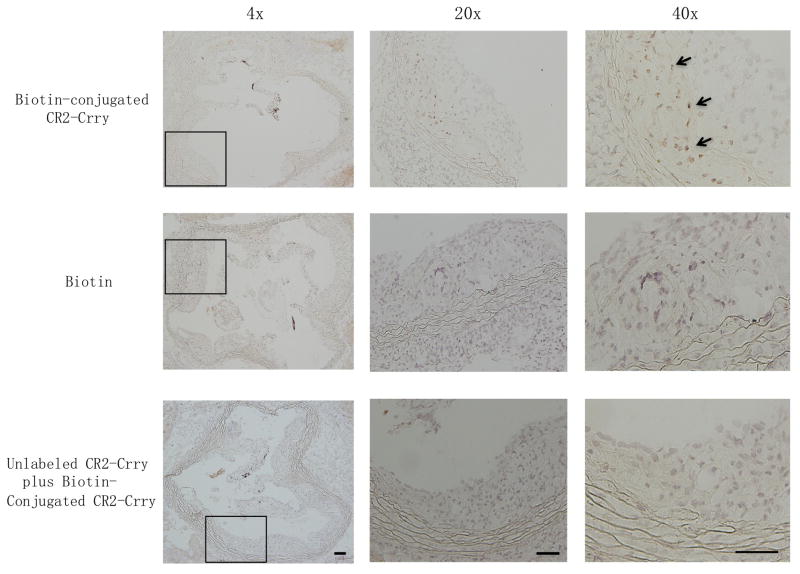

It has been shown previously that CR2-Crry has a short circulatory half life (8.5 hours), has no significant effect on serum complement activity at therapeutic doses, and targets specifically to sites of complement activation and C3 deposition19. To investigate whether the anti-atherogenic role of CR2-Crry is associated with the targeted inhibition of complement activation and C3 deposition on the vessel wall where atherosclerosis occurs, we stained the aortic roots with anti-C3b/iC3b/C3c specific antibodies. Immunofluorescence studies using an antibody specific for C3 activation (C3b/iC3b/C3c) revealed significantly less C3 deposition in aortic roots from both CD59 sufficient or deficient mice treated with CR2-Crry compared to vehicle (Fig. 3A and 3B). Further, to experimentally evaluate whether CR2-Crry targets the atherosclerotic plaque, we administered biotin-conjugated CR2-Crry, biotin alone (vehicle control), or unlabeled CR2-Crry plus biotin-conjugated CR2-Crry (competitive inhibition control) to mCd59ab+/+/Apoe−/− mice for one month, followed by analysis of biotin deposition in the plaque of the aortic root using ABC staining. Biotin staining was readily detected on cells in plaques from mice treated with biotin-conjugated CR2-Crry, but there was little to no staining in plaques from mice treated with biotin alone (vehicle control) or unlabeled CR2-Crry plus biotin-conjugated CR2-Crry (competitive inhibition control) (Figure 4). This result suggests that CR2-Crry localizes in the plaque of the mice after administration. Taken together, CR2-Crry inhibited complement activation at the site of complement activation in the vasculature in our experimental models.

Figure 3. C3b/iC3b/C3c deposition was reduced in atherosclerotic lesions of CR2-Crry-treated mice.

A and B, C3b/iC3b/C3c deposition in aortic root of mCd59a+/+/Apoe−/− (A) and mCd59ab−/−/Apoe−/− mice (B) (Left, CR2-Crry; Right, PBS). The mean of the quantitative results of three sections obtained from each mouse was used to perform the statistical analysis. Scatter plot graph shows levels of C3b/iC3b/C3c deposition (percentage of positive area vs. lesion area) detected in atherosclerotic lesions. Scale bar: 100μm *P<0.05.

Figure 4. Localization of CR2-Crry on the atherosclerotic plaque of mCd59ab+/+/Apoe−/− mice.

4-month-old mCd59ab+/+/Apoe−/− mice were treated with biotin-conjugated CR2-Crry (upper), biotin alone (middle), or with unlablled CR2-Crry plus biotin-conjugated CR2-Crry (lower). Deposition of biotin in the aortic root was detected using ABC staining. Arrows indicate biotin positive (brown stained) cells. Left, middle and Right columns respectively show 4X, 20X and 40 X magnifications of the area outlined by the black rectangle in the image at left. Scale bar, 100μm.

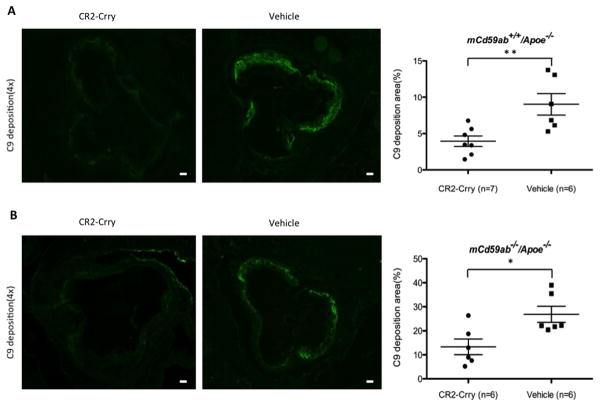

The data shown above using CD59 deficient mice indicate that CR2-Crry modulates the development of MAC-associated atherogenesis, and to further explore this functional connection between CR2-Crry treatment and MAC inhibition, we determined the effect of CR2-Crry on MAC deposition (using an antibody to C9, a component protein of the MAC). Mice treated with CR2-Crry had significantly less C9 deposition on the atherosclerotic lesion than the mice treated with vehicle (Fig. 5A and 5B). Furthermore, immunofluorescence studies showed that mice treated with CR2-Crry had a significantly lower content of inflammatory cells on the atherosclerotic lesion (macrophage and T-cells) compared to mice treated with vehicle (Supplemental figure 3). The above results taken together are consistent with a pathogenic role of the MAC in the atherosclerotic phenotype of our experimental mice, and demonstrate the therapeutic potential of targeted complement inhibition.

Figure 5. C9 deposition was reduced in atherosclerotic lesions in CR2-Crry-treated mice.

A and B, C9 deposition in aortic root of mCd59a+/+/Apoe−/− (A) and mCd59ab−/−/Apoe−/− mice (B) (Left, CR2-Crry; Right, PBS). Of note, the aortic roots of mCd59ab−/−/Apoe−/− mice were used to stain with the antibody. The mean of the quantitative results of three sections obtained from each mouse was used to perform the statistical analysis. Scatter plot graph shows levels of C9 deposition (percentage of positive area vs. lesion area) detected in atherosclerotic lesions. Scale bar: 100μm. *P<0.05;**P<0.005.

DISCUSSION

Here, we document that CR2-Crry protects both CD59 sufficient and CD59 deficient mice in an Apoe deficient background from the development of atherosclerosis through complement inhibition that is specifically targeted at the site of complement activation. The targeted complement inhibitor CR2-Crry, which was prepared by linking a fragment of CR2 to Crry, was initially reported to ameliorate tissue injury in a mouse model of intestinal ischemia/reperfusion injury19. Further studies have demonstrated that CR2-Crry attenuates inflammatory disease development in multiple models, including models of mouse spinal cord injury, collagen-induced arthritis and murine lupus20, 24, 25. CR2-Crry specifically targets to the sites of complement activation and has no significant effect on serum complement activity19, 20, 25. Here, we define the anti-atherogenic role of CR2-Crry, and demonstrate the therapeutic potential of this targeted approach.

Previously, we reported that the pre-treatment of mCd59ab deficient mice in an Apoe−/− background with anti-mouse C5 Ab attenuates the development of atherosclerosis3. Anti-mC5 Ab systemically inhibits complement activation by restricting MAC formation and C5a generation3. Further, either genetic deficiency of C6, a necessary component for MAC formation, or systemic blockage of C5a receptor attenuates atherosclerosis in Apoe−/− mice5, 7. It is notable that targeted complement inhibition has significant potential advantages over systemic inhibition for the treatment of complement-related diseases such as atherosclerosis. However, specific benefits of targeted vs. systemic complement inhibition for treating atherosclerosis remains to be determined. In this context, the immunosuppressive properties of CR2-targeted complement regulators, as well as potential side-effects will require further investigation clinically even though these types of targeted inhibitor have minimal immunosuppressive and off-target effects in mouse models27,29.

Crry restricts all three complement activation pathways at the C3 activation step, leading to the inhibition of C3 opsonization, C3a and C5a production, and MAC formation. Previous clinical and experimental results indicate that the MAC plays a critical role in atherogenesis1, 3–6, and here we show that CR2-Crry protects against the development of atherosclerosis in the mice. This result further confirms the critical atherogenic role of complement including MAC. Nevertheless, a recent study showed that deficiency of mouse DAF attenuates atherogenesis in Apoe−/− mice, and data indicated that this was due to a C3a modulating effect on lipid metabolism6, 26. In contrast, we found that CR2-Crry inhibits at the same point in the complement pathway as DAF14 but did not change body weight or the lipid profiles, including serum cholesterol and triglyceride, in both mCd59ab+/+/Apoe−/− and mCd59ab−/−/Apoe−/− mice. Since CR2-Crry is targeted and has higher complement inhibitory activity than Crry21, the reported effects of C3a may be due to systemic production in DAF deficient mice. The relative roles of the MAC vs. C3a/C5a in the development of atherosclerosis will require further investigation. Regardless, the current data indicate that targeted complement inhibition at the C3 activation step may provide a novel approach for the treatment of atherosclerosis.

CONCLUSION

The data demonstrate the therapeutic potential of targeted complement inhibitor CR2-Crry in treatment of atherosclerosis.

Supplementary Material

Highlight.

Targeted complement inhibitor CR2-Crry treatment resulted in significantly fewer atherosclerotic lesions in mCd59ab+/+/Apoe−/− mice.

CR2-Crry inhibited the accelerated atherogenesis seen in mCd59ab−/−/Apoe−/− mice.

CR2-Crry treatment reduced C3 and MAC deposition, infiltrating macrophages and T cells in the vasculature of both mice

The data demonstrated the therapeutic potential of targeted complement inhibition in prevention/treatment of atherosclerosis

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [RO1 AI061174 to X.Q., RO1 HL86562 and HL082485 to S.T.], and the American Heart Association [Grant-in-Aid 10Grant4370029 to X.Q.], and China Scholarship Council [2011622129 to F.L., 2010623100 to L.W.]

This work was supported by US National Institutes of Health grants RO1 AI061174 (X.Q.), a Grant-in-Aid from American Heart Association 10Grant4370029 (X.Q.), NIH RO1 HL86562 (ST) and HL082485 (ST), and China Scholarship Council (2011622129, to F. L.). We are grateful to Emily Paulling for her technical assistance in the production of CR2-Crry, Aliakbar Shahsafaei and Shen Dai for their technical assistances in the immune-histological studies, and Shiyin Jiao for helpful editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

F.L., L.W., G. W., and X.Q. contributed to the generation of experimental models and characterization of atherosclerosis. S.T. provided insight into complement blockade in the experimental models and supplied the CR2-Crry. F.L., L.W. G.W., C.W. Z.L., S.T., and X.Q. conducted the data analyses; all authors contributed to the project’s planning and writing of the manuscript; and X.Q and S.T. supervised the project.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hansson GK, Holm J, Kral JG. Accumulation of IgG and complement factor C3 in human arterial endothelium and atherosclerotic lesions. Acta Pathol Microbiol Immunol Scand [A] 1984;92:429–435. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1984.tb04424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rus HG, Niculescu F, Constantinescu E, Cristea A, Vlaicu R. Immunoelectron-microscopic localization of the terminal C5b-9 complement complex in human atherosclerotic fibrous plaque. Atherosclerosis. 1986;61:35–42. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(86)90111-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu G, Hu W, Shahsafaei A, Song W, Dobarro M, Sukhova GK, Bronson RR, Shi GP, Rother RP, Halperin JA, Qin X. Complement regulator CD59 protects against atherosclerosis by restricting the formation of complement membrane attack complex. Circulation research. 2009;104:550–558. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.191361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yun S, Leung VW, Botto M, Boyle JJ, Haskard DO. Brief report: accelerated atherosclerosis in low-density lipoprotein receptor-deficient mice lacking the membrane-bound complement regulator CD59. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis and vascular biology. 2008;28:1714–1716. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.169912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lewis RD, Jackson CL, Morgan BP, Hughes TR. The membrane attack complex of complement drives the progression of atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E knockout mice. Molecular immunology. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2009.10.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.An G, Miwa T, Song WL, Lawson JA, Rader DJ, Zhang Y, Song WC. CD59 but not DAF deficiency accelerates atherosclerosis in female ApoE knockout mice. Molecular immunology. 2009;46:1702–1709. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Manthey HD, Thomas AC, Shiels IA, Zernecke A, Woodruff TM, Rolfe B, Taylor SM. Complement C5a inhibition reduces atherosclerosis in ApoE−/− mice. Faseb J. 2011;25:2447–2455. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-174284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qin X, Gao B. The complement system in liver diseases. Cellular & molecular immunology. 2006;3:333–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morgan BP. Regulation of the complement membrane attack pathway. Crit Rev Immunol. 1999;19:173–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Medof ME, Lublin DM, Holers VM, Ayers DJ, Getty RR, Leykam JF, Atkinson JP, Tykocinski ML. Cloning and characterization of cDNAs encoding the complete sequence of decay-accelerating factor of human complement. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1987;84:2007–2011. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.7.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nicholson-Weller A, Spicer DB, Austen KF. Deficiency of the complement regulatory protein, “decay-accelerating factor,” on membranes of granulocytes, monocytes, and platelets in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. The New England journal of medicine. 1985;312:1091–1097. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198504253121704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qin X, Miwa T, Aktas H, Gao M, Lee C, Qian YM, Morton CC, Shahsafaei A, Song WC, Halperin JA. Genomic structure, functional comparison, and tissue distribution of mouse Cd59a and Cd59b. Mamm Genome. 2001;12:582–589. doi: 10.1007/s00335-001-2060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baalasubramanian S, Harris CL, Donev RM, Mizuno M, Omidvar N, Song WC, Morgan BP. CD59a is the primary regulator of membrane attack complex assembly in the mouse. J Immunol. 2004;173:3684–3692. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.6.3684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paul MS, Aegerter M, Cepek K, Miller MD, Weis JH. The murine complement receptor gene family III The genomic and transcriptional complexity of the Crry and Crry-ps genes. J Immunol. 1990;144:1988–1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu C, Mao D, Holers VM, Palanca B, Cheng AM, Molina H. A critical role for murine complement regulator crry in fetomaternal tolerance. Science. 2000;287:498–501. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5452.498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dmytrijuk A, Robie-Suh K, Cohen MH, Rieves D, Weiss K, Pazdur R. FDA report: eculizumab (Soliris) for the treatment of patients with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. The oncologist. 2008;13:993–1000. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2008-0086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reid RR, Prodeus AP, Khan W, Hsu T, Rosen FS, Carroll MC. Endotoxin shock in antibody-deficient mice: unraveling the role of natural antibody and complement in the clearance of lipopolysaccharide. J Immunol. 1997;159:970–975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taylor PR, Carugati A, Fadok VA, Cook HT, Andrews M, Carroll MC, Savill JS, Henson PM, Botto M, Walport MJ. A hierarchical role for classical pathway complement proteins in the clearance of apoptotic cells in vivo. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2000;192:359–366. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.3.359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Atkinson C, Song H, Lu B, Qiao F, Burns TA, Holers VM, Tsokos GC, Tomlinson S. Targeted complement inhibition by C3d recognition ameliorates tissue injury without apparent increase in susceptibility to infection. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2005;115:2444–2453. doi: 10.1172/JCI25208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.He C, Imai M, Song H, Quigg RJ, Tomlinson S. Complement inhibitors targeted to the proximal tubule prevent injury in experimental nephrotic syndrome and demonstrate a key role for C5b-9. J Immunol. 2005;174:5750–5757. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.9.5750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spitzer D, Unsinger J, Mao D, Wu X, Molina H, Atkinson JP. In vivo correction of complement regulatory protein deficiency with an inhibitor targeting the red blood cell membrane. J Immunol. 2005;175:7763–7770. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.11.7763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carbone J, Micheloud D, Salcedo M, Rincon D, Banares R, Clemente G, Jensen J, Sarmiento E, Rodriguez-Molina J, Fernandez-Cruz E. Humoral and cellular immune monitoring might be useful to identify liver transplant recipients at risk for development of infection. Transpl Infect Dis. 2008;10:396–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3062.2008.00329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huber-Lang M, Sarma JV, Zetoune FS, Rittirsch D, Neff TA, McGuire SR, Lambris JD, Warner RL, Flierl MA, Hoesel LM, Gebhard F, Younger JG, Drouin SM, Wetsel RA, Ward PA. Generation of C5a in the absence of C3: a new complement activation pathway. Nat Med. 2006;12:682–687. doi: 10.1038/nm1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qiao F, Atkinson C, Song H, Pannu R, Singh I, Tomlinson S. Complement plays an important role in spinal cord injury and represents a therapeutic target for improving recovery following trauma. The American journal of pathology. 2006;169:1039–1047. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.060248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Atkinson C, Qiao F, Song H, Gilkeson GS, Tomlinson S. Low-dose targeted complement inhibition protects against renal disease and other manifestations of autoimmune disease in MRL/lpr mice. J Immunol. 2008;180:1231–1238. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.2.1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lewis RD, Perry MJ, Guschina IA, Jackson CL, Morgan BP, Hughes TR. CD55 Deficiency Protects against Atherosclerosis in Apoe-Deficient Mice via C3a Modulation of Lipid Metabolism. The American journal of pathology. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang Y, Qiao F, Atkinson C, Holers VM, Tomlinson S. A novel targeted inhibitor of the alternative pathway of complement and its therapeutic application in ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Immunol. 2008;181:8068–8076. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.11.8068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sekine H, Kinser TT, Qiao F, Martinez E, Paulling E, Ruiz P, Gilkeson GS, Tomlinson S. The benefit of targeted and selective inhibition of the alternative complement pathway for modulating autoimmunity and renal disease in MRL/lpr mice. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2011;63:1076–1085. doi: 10.1002/art.30222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Song H, Qiao F, Atkinson C, Holers VM, Tomlinson S. A complement C3 inhibitor specifically targeted to sites of complement activation effectively ameliorates collagen-induced arthritis in DBA/1J mice. J Immunol. 2007;179:7860–7867. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.11.7860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu G, Chen T, Shahsafaei A, Hu W, Bronson RT, Shi GP, Halperin JA, Aktas H, Qin X. Complement regulator CD59 protects against angiotensin II-induced abdominal aortic aneurysms in mice. Circulation. 2010;121:1338–1346. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.844589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.