Abstract

Marriage and partnerships bring about non-negligible health risks in populations with generalized HIV epidemics, and concerns about the possible transmission of HIV thus often factor in the decision-making about partnership formation and dissolution. The awareness of and responses to HIV risk stemming from regular sexual partners have been well documented in African populations, but few studies have estimated the effects of observed HIV status on marriage decisions and outcomes. We study marriage dissolution and remarriage using longitudinal data with repeated HIV and marital status measurements from rural Malawi. Results indicate that HIV positive individuals face greater risks of union dissolution (both via widowhood and divorce) and lower remarriage rates. Modeling studies suggest that the exclusion of HIV positives from the marriage or partnerships market will decelerate the propagation of HIV.

Introduction

The HIV epidemic has profoundly changed the nature of partnerships and marriage in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). As the epidemic spread from high-risk groups to the general population, individuals faced substantial risks of infection from spouses or cohabiting partners (Clark, Bruce & Dude 2006; de Walque 2007; Glynn et al. 2003). A modeling study suggests that the majority of new infections (in Rwanda and Zambia) now occurs within marriage (Dunkle 2008).1

The connection between marriage and HIV infection has not gone unnoticed by sub-Saharan Africans. Evidence from rural Malawi shows that many married men and women are most worried about contracting HIV from a husband or wife (Anglewicz & Kohler 2009, Watkins 2004), and may divorce a spouse who they believe is a potential source of HIV infection (Smith & Watkins 2005, Watkins 2004, Reniers 2008). Further, some studies established that HIV positive individuals, women in particular, are indeed more vulnerable to partnership dissolution via separation, divorce, or the death of a spouse (Carpenter et al. 1999; Floyd et al 2008, Lopman et al. 2009, Mackelprang et al. 2014, Porter et al. 2004). The higher occurrence of widowhood among women is directly related to the age differences between spouses, but their elevated exposure to separation and divorce is likely to have more complex social and behavioral drivers, including gender differences in the social acceptance of ‘deviant’ behavior (e.g., extramarital sex), and male-female differences in economic self-sufficiency that could alter divorce threat points.

Relatively high rates of marriage dissolution in couples where one or both partners are HIV positive is one of the reasons why cross sectional studies tend to find higher HIV prevalence in divorced and widowed compared to currently married and never married men and women (Boileau et al. 2009, Boerma et al. 2002, de Walque & Kline 2012; Gregson et al. 2001, Welz et al. 2007). The cross-sectional association between marital status and HIV prevalence is further strengthened by the disproportional recruitment of HIV negatives into new unions. Evidence from Malawi shows that individuals screen future spouses for characteristics that are deemed safe, and that (presumed) HIV positive status is associated with lower (re)marriage rates (Clark, Poulin & Kohler 2009; Reniers 2008; Watkins 2004). Concern over the HIV status of current or future partners is also supported by anecdotal evidence from other African populations, including the promotion of pre-marital screening for HIV by some churches, and the publication of personal advertisements with disclosure of HIV status (Reniers and Helleringer 2011). There is, however, little quantitative evidence of the selective recruitment into new marriages using measured HIV status.

We use four waves (2004–2010) of panel data from rural Malawi to study the association between HIV status and marriage dissolution and formation. We anticipate that (1) union dissolution rates via divorce and widowhood are higher in unions where the husband or wife is HIV positive rather than negative, and (2) the re-entry into marriage is less common for HIV positive men and women. Following Helleringer and Kohler (2007), we refer to these joint phenomena as the drift of HIV positives out of the marriage market. The seclusion of HIV positives may be undesirable for infected men and women, but it could have advantageous public health implications by reducing HIV incidence (Reniers and Armbruster 2012).

Background: HIV and Marriage Patterns in Malawi

Our study is set in Malawi, where an estimated 10.6% of all adults aged 15–49 are HIV-positive (NSO and ICF Macro 2011). Regional differences in HIV prevalence are quite pronounced: the highest HIV infection rates are recorded in the southern region (14.5%), followed by the Centre (7.6%) and North (6.6%) (NSO and ICF Macro 2011). As with many other AIDS-affected Africa countries, access to HIV testing rapidly increased over the past decade: the percentage aged 15–49 ever-tested for HIV and received results increased from 13 to 72 percent and from 15 to 51 percent between 2004 and 2010 and for women and men, respectively (NSO and ICF Macro 2005; NSO and ICF Macro 2011). HIV testing coverage expanded in parallel with the scale-up of antiretroviral therapy (ART): the number of patients on ART increased from approximately 13,000 in 2004 to 250,000 in 2010 (Lowrance et al. 2008, UNAIDS 2008, WHO/UNAIDS/UNICEF 2011). We do not have information about ART status in our sample and it is therefore not possible to demonstrate whether or not it has affected the marriage dynamics that we describe here.

As is the case in other sub-Saharan African countries, Malawians are well aware of HIV/AIDS and its risk factors: by 2004 over 98% of men and women had heard of HIV/AIDS, over 57% understood that condoms protect from HIV infection, and over 67% believed that HIV can be prevented by limiting sexual intercourse to one uninfected partner (NSO and ICF Macro 2005). Awareness is higher among men than women, and all of the above indicators have increased over time (NSO and ICF Macro 2011).

Malawi is an intriguing setting to study the interactions between marriage and HIV. Marriage is early and universal, but marriage dissolution and remarriage are common. The mean age at first marriage is 17.9 years for women and 22.6 for men, and the percentages never married by age 25–29 are 3.1% and 16.6% for women and men, respectively (NSO and ICF Macro 2011). An estimated 45% of first unions end in divorce within 20 years, and approximately 90% of women remarry within 10 years of a divorce (Bracher, Santow, & Watkins 2003; Reniers 2003).

Marriage patterns differ substantially across the three regions of Malawi and tend to correlate with the kinship systems. Rumphi district in the north is predominantly patrilineal with patri- or virilocal residence after marriage (wife moves to her husband’s house after marriage) and inheritance traced through sons. The ethnic groups in the south (Balaka) follow a matrilineal system of descent and inheritance, and residence after marriage is often uxorilocal (husband moves in with his spouse). In Mchinji, in the center of the country, descent is less rigidly matrilineal and residence may be uxori-, viri- or neolocal. The northern region has the highest rates of polygyny, with the lowest rates in the south (Reniers and Tfaily 2012).

These patterns affect marital change in Malawi. Matrilineal ethnic groups often have higher partnership dissolution rates than patrilineal groups, a phenomenon that is possibly associated with women’s greater autonomy in these settings, and that is the case in Malawi as well (Reniers 2003). The association between polygyny and marriage dissolution is more complex. Partnership turnover is known to be relatively high in populations that practice polygyny (Pison 1986), but in a previous study we found that divorce is only elevated in unions where other co-wives are already present at the time of marriage. The addition of another spouse appears to have a marriage stabilizing effect (Reniers 2003). Other factors that we previously identified as predictors of divorce include individual attributes such as educational attainment and religion; and partnership attributes, including marriage duration, age difference between spouses, the presence of children, and ethnic homogamy.

Data and methods

Data

We use data from the Malawi Longitudinal Study of Families and Health (MLSFH).2 The MLSFH was designed as a couples’ survey, targeting a population-based representative sample of approximately 1,500 ever-married women and 1,000 of their husbands in three rural sites of Malawi. Following a household enumeration in the three designated survey sites in 1998, a random sample of approximately 500 ever-married women aged 15–49 were selected to be interviewed in each site, along with all of their spouses. The first follow-up in 2001 included all respondents from the first wave, along with any new spouses. The MLSFH returned to interview all respondents in 2004, 2006, 2008 and 2010; and also added two new samples: (1) approximately 1,500 young adults aged 15–27 in 2004 (both ever- and never-married); and (2) approximately 800 parents of existing MSLFH respondents in 2008. As in 2001, all new spouses of respondents were added to the sample in each wave of data collection. The additions to the original sample increased the target sample size in 2004 to approximately 4,500 respondents, of whom 3,261 (74%) were successfully interviewed. Response rates were similar in subsequent survey rounds. Descriptions of the MLSFH data and sampling are presented in Watkins et al. (2003) and Kohler et al. (2014). Bignami et al. (2003), Anglewicz et al. (2009), and Kohler et al. (2014) discuss sample limitations and present analysis of data quality. Below we highlight several features of the data that are of particular importance for our analysis.

MLSFH initiated HIV testing for all respondents in 2004.3 A total of 2,905 respondents accepted testing in 2004 and 291 refused (a 9.1% refusal rate for testing). Approximately two-thirds of those tested in 2004 received their test results a few months later. HIV testing was repeated in 2006 and 2008 with rapid tests, and acceptance rates were over 90% in each of these survey rounds. Almost all respondents who accepted to test in 2006 and 2008 test also received their test result in a post-test counseling session during the same visit. Aprino, De Cao, and Peracchi (2013), and Obare et al. (2009) provide more details about testing acceptance rates and HIV prevalence estimates in the MLSFH. Because HIV status is the predictor of interest in the analyses that follow, we restrict our analytical dataset to the four most recent surveys, starting with 2004.

Since 2006, the MLSFH has also collected complete marital histories for all respondents. Individuals were asked to list all marriages, along with dates for the beginning and end (if applicable) of the marriage, the reason for marital dissolution, and other characteristics of the marriage. Using these data, we identify all individuals who divorced, separated or widowed, and/or remarried between MLSFH waves. For each marriage, we have information on a number of individual and partnership attributes, including age at marriage, age of the spouse; the residence pattern after marriage (virilocal, uxorilocal or neolocal), marriage order, marriage duration, and whether or not the marriage was polygamous.

Sample and outcome variables

The analysis of the predictors of divorce and widowhood is restricted to men and women who are married at the beginning of each MLSFH survey interval (in 2004in 2006 and 2008), but also includes a few individuals who married during the survey interval. We use these longitudinal data to identify men and women who experienced divorce or widowhood by the end of the interval (as two separate outcomes).

For the analysis of remarriage, we configure the sample to include only individuals eligible for remarriage in between MLSFH waves. This includes respondents who were either divorced or widowed at the beginning of each survey interval as well as individuals who were married but experienced marital dissolution in between MLSFH waves. Since we are primarily interested in remarriage after marital dissolution, we omit polygamous men who married another wife without experiencing a divorce, separation or widowhood (polygamous men who experienced the dissolution of one of his unions are included). Similarly, we also omit any MLSFH respondents who were never-married at the start of each survey interval and married for the first time in between waves; thus, approximately two-thirds of never-married adolescents in 2004 were not included in the models. As with the analysis of marriage dissolution, we use longitudinal data to identify men and women who remarry between each MLSFH wave, which serves as a binary dependent variable for our second set of analyses.

Predictor variables

The choice of variables to include in our models is informed by previous research on marriage, divorce and remarriage in Malawi and elsewhere in SSA. We begin with several basic demographic characteristics, such as the region of residence, household wealth,4 number of living children, and level of education. Then we consider several marriage-related measures, including residence patterns after marriage, polygyny, age at marriage, ethnic heterogamy, age difference between spouses, and higher order marriages. Since research also shows that HIV infection (actual or perceived) has an important influence on marriage-decision making, we include HIV status in our models. In the analysis of remarriage we no longer control for marriage and partner characteristics, but include the time elapsed since the end of the previous marriage as well as the terminating event of the previous marriage (divorce or widowhood).

Analytic Plan

We study changes in marital status over three survey intervals (2004–06, 2006–08, and 2008–10) using random effects regression models of the following form:

The dependent variable is the log odds that individual i will experience marital outcome j (j = 1, 2) relative to 0 (currently married). Outcome 1 is divorce and 2 is experiencing widowhood. The outcome for individual i occurs between times t and t+1 (i.e. by the next wave of MLSFH data), and independent variables are measured at time t. Xijt represents a set of individual characteristics (HIV status, region, etc…), Mijt, represents the marriage-related characteristics listed above, rijt is the random effect for the survey interval, and εijt is a random, logistically-distributed disturbance term for person i at time t.

For our analysis of marital dissolution and remarriage, random effects regression is appealing for several reasons. First, random effects regression allows us to include data from several MLSFH survey intervals while controlling for the dependence of individual outcomes across MLSFH waves (one individual can contribute multiple survey intervals). Second, the random effects models that we use also include a variable for survey wave that enables us to measure trends in divorce and remarriage (while controlling for other factors). Third, unlike fixed effects regressions, random effects models provide estimates of both time-varying and time-invariant characteristics in the model. Because several variables of interest have very little variation for individuals over time (e.g. education, HIV infection) and other measures do not change at all over time (e.g. region of residence), random effects is better equipped to measure the relationship between these measures and the dependent variables. Fixed effects regression reduces the sample to observations that change in the dependent variable, which increases standard errors of independent variables that change for only few respondents over time (such as HIV status) (Alison 2005; Hsaio 2003). It is important to note that while random effects are useful for longitudinal data analysis with repeated measurements for the same individuals, they do not control for unobserved time-invariant individual attributes that may affect divorce, widowhood, and remarriage. These time-invariant characteristics may be important: some, like risk-taking propensity, may affect both HIV status and marital change, which implies that random effects regression results may be biased.

As described above, the predictor of interest in each of these models is HIV status assessed at the beginning of the survey interval.5 The outcome (marriage dissolution or remarriage) is measured with data from the next survey round, which ensures that the causal order of events is respected. We present the results for two models of marriage dissolution. In the first model we test the effect of HIV positive status and control for region, age at marriage, and marriage duration. We test quadratic terms for age at marriage and marriage duration to allow for non-linear associations with divorce and widowhood. In the second model, we introduce an extended set of control variables including the residency pattern after marriage, marriage order, and an indicator variable for polygamous marriages.

In addition to the individual-level analyses of marriage dissolution just described, we conducted a comparable analysis on a subset of couples that could be linked and followed over time. This approach is appealing because some couple characteristics, such as the couple’s HIV status configuration, can be included as predictors to formally test gender differences in the association between HIV status and marriage outcomes. However, our couples sample with HIV status information for both spouses is much smaller than the respective individual samples, and the results insufficiently conclusive to warrant reporting in detail.

For modeling the association between HIV status and remarriage, we use random effects models for a binary outcome (remarried or not). This time our sample is restricted to men and women who were divorced or widowed before the end of the survey interval. The set of control variables includes the age at the end of the previous marriage, the time elapsed since the previous marriage, wealth, region, education, and a number of personal marriage history attributes, such as the number of lifetime marriages, the number of living children and the outcome of the previous marriage (divorce or widowhood).

Results

Sample descriptive statistics are presented in Table 1. A notable characteristic of this sample is the relatively high mean age: 40.0 years for women in 2006, and 42.5 years for men. Similarly, the mean duration of ongoing marriages in 2006 is quite high, at 14.0 years for women and 13.3 years for men. These sample characteristics arise from the fact that we are using data from 2004 onwards, whereas most of the respondents were initially sampled in 1998. The ‘old’ sample also implies that most marriages have already withstood the test of time and we thus expect divorce rates to be relatively low.

Table 1.

Background characteristics for MLSFH men and women, 2004–2008

| MLSFH wave | Women | Men | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | 2006 | 2008 | 2004 | 2006 | 2008 | |

| % HIV positive | 4.6 | 7.3 | 10.8 | 2.7 | 4.3 | 7.2 |

| Age | ||||||

| Mean | 37.7 | 40.0 | 42.2 | 41.2 | 42.5 | 44.2 |

| Interquartile range | 21–47 | 23–49 | 25–51 | 23–51 | 25–53 | 27–55 |

| Mean age at last marriage | 19.0 | 21.6 | 22.1 | 21.7 | 28.4 | 29.4 |

| Region of residence | ||||||

| % Balaka | 34.3 | 33.3 | 36.4 | 34.5 | 33.5 | 33.9 |

| % Mchinji | 33.4 | 32.4 | 33.3 | 32.4 | 32.6 | 33.6 |

| % Rumphi | 32.3 | 33.3 | 30.3 | 32.1 | 33.9 | 32.5 |

| Level of education | ||||||

| % No education | 24.3 | 29.8 | 32.3 | 14.2 | 17.0 | 15.0 |

| % At least some primary | 66.5 | 61.2 | 59.6 | 67.2 | 63.3 | 65.5 |

| % At least some secondary | 9.2 | 9.0 | 8.1 | 18.7 | 19.7 | 19.5 |

| Marriage-related characteristics | ||||||

| % Divorced by next wave | 5.9 | 6.0 | 6.8 | 3.5 | 5.8 | 6.3 |

| % Widowed by next wave | 2.0 | 2.5 | 2.2 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 1.2 |

| % Remarried by next wave (if divorced/widowed)a | 17.2 | 28.8 | 16.0 | 66.1 | 66.4 | 51.6 |

| Mean number of living children | 3.4 | 3.6 | 4.1 | 3.7 | 3.9 | 4.6 |

| Marital residence patterns | ||||||

| % Virilocal (living at husband’s home) | 58.8 | 59.4 | 60.9 | 68.7 | 67.5 | 67.4 |

| % Uxorilocal (living at wife’s home) | 30.6 | 35.2 | 34.1 | 23.8 | 28.5 | 28.3 |

| % Neolocal | 10.6 | 5.4 | 5.0 | 7.5 | 4.1 | 4.3 |

| Mean number of times married | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.7 |

| % Widowed in previous marriagea | 23.9 | 46.1 | 42.5 | 10.4 | 13.8 | 13.7 |

| Duration of current marriage | ||||||

| Mean | 13.5 | 14.0 | 18.0 | 12.9 | 13.3 | 17.8 |

| Interquartile range | 6–20 | 5–21 | 7–26 | 5–19 | 5–20 | 7–27 |

| N= | 1401 | 1535 | 1665 | 1083 | 1173 | 1221 |

Percentage is among individuals who experienced marital dissolution.

HIV prevalence in the sample is higher for women than for men, which corresponds to HIV patterns elsewhere in SSA. HIV prevalence estimates also increase over time (from 4.6 to 10.8 percent for women, and from 2.7 to 7.2% for men) which likely results from the accumulation of incident cases (Obare et al. 2010) and reduced mortality following the introduction of ART (Jahn et al. 2008).

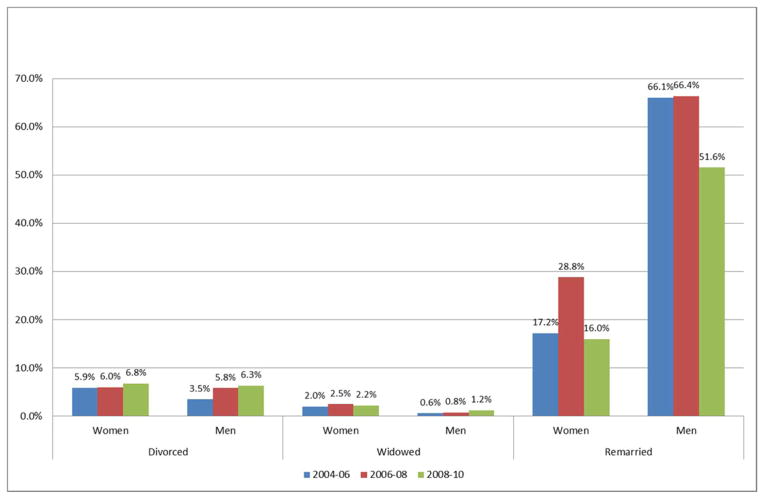

Figure 1 presents MLSFH marital transitions, and illustrates the percentages of ever-married men and women who divorced, experienced the death of a spouse, or remarried between waves. Between 3.5 and 6.8 percent of ever-married interviewed men and women report a divorce between survey rounds and between 0.6 and 2.5 percent report the death of a spouse. In addition to higher dissolution rates, women also report lower remarriage rates than men.

Figure 1.

Percentages of Men and Women Experiencing Marital Change Between MLSFH Waves, 2004–2010

Notes: Percentages remarried are for respondents who experienced marital dissolution.

Divorce and Widowhood

Results for the multinomial random effects regression models for divorce and widowhood are presented in Tables 2a (comparing divorce with remaining married) and 2b (comparing widowhood with remaining married). Results are presented as relative risk ratios (RRR), and those for women appear on the left hand side of the table.

Table 2a.

Random effects multinomial regression results for characteristics associated with experiencing a divorce compared to remaining married, MLSFH women and men, 2004–10

| Women | Men | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | |||||||||

| RRR | 95% CI | RRR | 95% CI | RRR | 95% CI | RRR | 95% CI | |||||

| HIV positive | 3.21** | 1.82 | 5.67 | 3.17** | 1.79 | 5.61 | 2.21 | 0.86 | 5.74 | 2.14 | 0.81 | 5.65 |

| Age at marriage | 1.12** | 1.05 | 1.19 | 1.02a | 1.00 | 1.04 | 1.09** | 1.04 | 1.15 | 1.04** | 1.02 | 1.07 |

| Age at marriage squared | 0.99** | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.99c | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Region of residence | ||||||||||||

| Balaka (ref) | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- |

| Mchinji | 2.05** | 1.36 | 3.10 | 1.29 | 0.82 | 2.04 | 1.05 | 0.58 | 1.88 | 1.04 | 0.54 | 2.00 |

| Rumphi | 0.78 | 0.49 | 1.25 | 0.86 | 0.53 | 1.42 | 0.86 | 0.49 | 1.51 | 0.84 | 0.47 | 1.52 |

| Marriage and fertility | ||||||||||||

| Marriage and migration | ||||||||||||

| Virilocal (ref) | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ||||||

| Uxorilocal | 2.30** | 1.00 | 3.63 | 0.85 | 0.43 | 1.69 | ||||||

| Neolocal | 1.95b | 0.97 | 3.93 | 1.68 | 0.68 | 4.18 | ||||||

| Number lifetime marriages | 1.14 | 0.87 | 1.49 | 1.11 | 0.86 | 1.43 | ||||||

| Duration of most recent marriage | 0.96** | 0.94 | 0.98 | 0.96** | 0.95 | 0.98 | 0.90** | 0.87 | 0.93 | 0.85** | 0.79 | 0.91 |

| Duration of most recent marriage squared | 1.01* | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| MLSFH Survey wave | 1.22** | 1.10 | 1.34 | 1.20** | 1.08 | 1.33 | 1.33** | 1.15 | 1.53 | 1.35** | 1.17 | 1.56 |

| N= | 2066 | 2066 | 1608 | 1608 | ||||||||

Notes:

p ≤ 0.05;

p ≤ 0.01;

p=0.09,

p=0.08,

p=0.07

The following covariates were insignificant and omitted from the final models education, polygamous marriage, ethnic homogamy, age difference between spouses, number of children, household wealth, and whether HIV was ever discussed with the spouse.

The results highlight the importance of HIV status as a predictor of marital change. Table 2a shows that the relative risk of a divorce is three times as high for HIV positive compared to HIV negative women. The RRR for men is also suggestive of a positive association between HIV status and divorce, but the coefficient does not reach statistical significance. As shown in Table 2b, HIV status is also a significant predictor of widowhood. In this case both men and women who are HIV positive have a significantly higher relative risk of widowhood by the next wave.

Table 2b.

Random effects multinomial regression results for characteristics associated with experiencing widowhood compared to remaining married, MLSFH women and men, 2004–10

| Women | Men | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | |||||||||

| RRR | 95% CI | RRR | 95% CI | RRR | 95% CI | RRR | 95% CI | |||||

| HIV positive | 4.18** | 2.05 | 8.50 | 4.39** | 2.15 | 8.93 | 3.71* | 1.02 | 13.46 | 4.05* | 1.11 | 14.86 |

| Age at marriage | 1.13** | 1.04 | 1.22 | 1.06** | 1.04 | 1.09 | 1.31* | 1.05 | 1.63 | 1.05** | 1.01 | 1.09 |

| Age at marriage squared | 0.99 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.99* | 0.99 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Region of residence | ||||||||||||

| Balaka (ref) | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- |

| Mchinji | 2.09* | 1.24 | 3.50 | 1.97* | 1.08 | 3.59 | 1.34 | 0.45 | 3.99 | 1.23 | 0.37 | 4.13 |

| Rumphi | 1.20 | 0.70 | 2.06 | 1.14 | 0.65 | 2.01 | 2.34a | 0.91 | 6.02 | 2.57b | 0.97 | 6.84 |

| Marriage and fertility | ||||||||||||

| Marriage and migration | ||||||||||||

| Virilocal (ref) | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ||||||

| Uxorilocal | 0.98 | 0.54 | 1.78 | 1.06 | 0.32 | 3.52 | ||||||

| Neolocal | 3.53** | 1.73 | 7.20 | 2.60 | 0.72 | 9.39 | ||||||

| Number lifetime marriages | 1.16* | 1.01 | 1.62 | 1.06 | 0.71 | 1.57 | ||||||

| Duration of most recent marriage | 1.08** | 1.07 | 1.10 | 1.09** | 1.08 | 1.11 | 1.02 | 0.99 | 1.05 | 0.92* | 0.85 | 1.00 |

| Duration of most recent marriage squared | 1.00** | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| MLSFH Survey wave | 1.73** | 1.49 | 2.00 | 1.57** | 1.36 | 1.82 | 1.52** | 1.18 | 1.95 | 1.50** | 1.16 | 1.93 |

| N= | 2066 | 2066 | 1608 | 1608 | ||||||||

Notes:

p ≤ 0.05;

p ≤ 0.01;

p=0.07;

p=0.07

The following covariates were insignificant and omitted from the final models education, polygamous marriage, ethnic homogamy, age difference between spouses, number of children, household wealth, and whether HIV was ever discussed with the spouse.

Other significant correlates of divorce (compared to remaining married) are age at marriage, marital duration, region of residence, and the residence pattern after marriage. The relationship between age at marriage and divorce is non-linear (first greater relative risk with age, then lower risk at older ages). Marriages where residence is uxori- and neo-local (marginally significant) are less stable, but are statistically significant only for women.6 Marriage duration is negatively associated with divorce for women. For men this relationship has a significant positive quadratic term indicating that the relationship between marriage duration and divorce has a convex shape. The coefficient for survey wave indicates that divorce has increased between 2004 and 2010. In general, all coefficients point in the same direction for men and women, but they are not always significant for both sexes.

Aside from positive HIV status, widowhood is correlated with measures capturing the progression of time: age at marriage, marriage duration, and survey round. Widowhood also differs by region, with women in Mchinji and men in Rumphi (marginally significant) having higher widowhood risk ratios than those in Balaka. Having more lifetime marriages was positively associated with widowhood among women. Finally, women with neolocal residence after marriage were significantly more likely to experience widowhood than those who live virilocally.

We also tested other factors that could be associated with marital dissolution including education, polygamous marriage, ethnic homogamy, the age difference between spouses, the number of children in union, household wealth, and whether HIV was ever discussed with the spouse. None of these their coefficients obtained statistical significance in our models and were omitted from the results presented here.

Remarriage

As with marriage dissolution, HIV status affects the likelihood of remarriage (Table 3). Among women, the odds of remarrying are almost 50% lower if they are HIV positives rather than negative. The coefficients for men point in the same direction but do not reach statistical significance. The small sample (for men in particular) does not allow us to explore how the remarriage odds might differ for HIV positive men and women.

Table 3.

Random effects logistic regression results for characteristics associated with remarriage, MLSFH women and men, 2004–10

| Women | Men | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | |||||||||

| Odds | 95% CI | Odds | 95% CI | Odds | 95% CI | Odds | 95% CI | |||||

| HIV positive | 0.53* | 0.22 | 0.84 | 0.60b | 0.24 | 0.93 | 0.94 | 0.11 | 3.23 | 0.47 | 0.03 | 9.35 |

| Age | 0.81** | 0.74 | 0.87 | 0.94** | 0.91 | 0.96 | 0.92** | 0.89 | 0.96 | 0.87* | 0.81 | 0.99 |

| Age squared | 1.01** | 1.00 | 1.00 | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- |

| Wealth | 0.97 | 0.81 | 1.11 | 1.55d | 0.91 | 2.82 | ||||||

| Region of residence | ||||||||||||

| Balaka (ref) | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- |

| Mchinji | 1.03 | 0.62 | 1.49 | 1.21 | 0.71 | 2.07 | 0.78 | 0.30 | 2.38 | 1.98 | 0.30 | 8.88 |

| Rumphi | 0.65a | 0.39 | 1.05 | 0.71 | 0.36 | 1.48 | 0.45 | 0.15 | 1.27 | 0.40 | 0.12 | 4.11 |

| Education | ||||||||||||

| No education (ref) | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ---- | ||||||

| Primary | 0.68 | 0.33 | 1.06 | 0.54 | 0.05 | 2.79 | ||||||

| Secondary or higher | 0.65 | 0.23 | 2.22 | 0.71 | 0.02 | 3.44 | ||||||

| Marriage and fertility | ||||||||||||

| Number living children | 0.86** | 0.76 | 0.98 | 1.14 | 0.74 | 1.53 | ||||||

| Number lifetime marriages | 1.11 | 0.58 | 1.12 | 2.22 | 0.30 | 2.30 | ||||||

| Widowed in previous marriage | 0.36** | 0.16 | 0.66 | 0.01* | 0.00 | 0.52 | ||||||

| MLSFH survey wave | 0.91 | 0.77 | 0.98 | 1.14c | 0.90 | 1.20 | 0.71* | 0.53 | 0.91 | 0.83 | 0.46 | 1.10 |

| N= | 520 | 182 | ||||||||||

Notes:

p ≤ 0.05;

p ≤ 0.01;

p=0.07;

p=0.08;

p=0.05;

p=0.09

The following covariates were insignificant and omitted from the final models: duration since marital dissolution, previous marriage polygamous.

In model 2, we find that a higher number of living children inhibits remarriage among women, and that widowed men and women have significantly lower remarriage odds than those whose previous marriage ended in divorce. The coefficient for previous marriage ending in widowhood for men is relatively large with a wide confidence interval, which is a reflection of the fact that the number of widowers in the sample is quite small. Men with greater wealth are more likely to remarry (marginally significant). Another significant predictor of remarriage is age at the end of the previous marriage (negative relationship for both men and women).

Discussion

We have assessed the effect of HIV status on marriage dynamics in a longitudinal study set in rural Malawi. Our study population is quite unusual because the mean age of respondents was relatively high (about 40 years), and approximately three quarters of them were in marriages that had been ongoing for 5 years or more. We thus expected these marriages to be fairly robust, but still find that between 3.5 and 6.8% of the unions ended in divorce over each survey interval (about 2 years each). Marriage dissolution through divorce is at least three times more likely in unions where the wife is HIV positive rather than negative. Husbands’ HIV status is not significantly associated with divorce, even though the coefficients point in the same direction. HIV status is also an important predictor for the dissolution of marriages via the death of the spouse, as are variables that capture the progression of time (age at marriage, duration of marriage, survey wave).

Just as women’s HIV status plays a critical role in marriage dissolution, it also steers who enters new unions and who does not. Again, that association is statistically significant for women only, and the relatively small sample size does not offer much leverage to formally test gender differences. Other factors that inhibit remarriage are older age (both sexes), the number of children (women only), lack of wealth (men only) and widowhood. Because HIV status is not always publicly known, widowhood may actually serve as a marker of potential HIV infection to the outside world.

Together these results suggest that HIV infection may be an important turning point in men and women’s marital trajectories. High dissolution rates and low union formation rates following HIV infection mark the gradual exclusion of HIV positive individuals from the marriage market. This pattern is consistent with the relatively high HIV prevalence rates that have been observed in formerly married compared to (re)married women in cross-sectional studies (de Walque and Kline 2012).

Our results also suggest that the association between HIV status and marriage dynamics differs by gender. We would, however, need a larger sample size to confirm whether HIV infection is indeed a more defining event in women’s marital trajectories compared to that of men, but our results are consistent with the finding that elevated HIV prevalence in formerly married women is more pronounced than in formerly married men (Walque and Kline 2012). The evidence presented here also supports our earlier work which suggests that men are more empowered than women to deploy divorce and partner selection as a means of insulating themselves from HIV (Reniers 2008). Such gendered partnership dynamics, if genuine, might reinforce the imbalance in the sex ratio of infections because it implies that women will spend more time in unions with HIV positive men than vice versa (Reniers and Armbruster 2012).

On the other hand, the drift of HIV positive men and women out of the marriage market could mitigate the spread of HIV at the population level because HIV positive individuals will spend less time in partnerships where they could transmit the virus to others (Reniers and Armbruster 2012). The HIV status-based partnership mixing patterns described above could thus have advantageous public health effects,7 despite the individual hardship that is likely to accompany partnership dissolution.

The most important study limitations are relate to sample size constraints. For example, the relatively small study population does not allow us to deploy fixed-effects regression models to control for unobserved time-invariant characteristics, or to formally test gender differences in the association between HIV status and marriage transitions. A more refined analysis of association between HIV status and marriage dissolution, for example, should be based on a sample of couples, and take the joint HIV status of both partners into account. The small numbers of concordant HIV positive and discordant HIV status couples precluded such a dyadic approach. Sample attrition could also affect our conclusions if respondents who leave the study area are systematically different from those who remain (e.g., those experiencing marital dissolution are more likely to migrate and have higher HIV prevalence (Anglewicz 2012)). To examine this possibility we reran our analyses with the inclusion of a sample of MLSFH migrants collected in 2007, and the results did not substantially change from those we present here. Selective participation in HIV testing is yet another possible source of bias, but we reiterate that testing refusal rates were under 10% in each survey wave.

Acknowledgments

The Malawi Longitudinal Study of Families and Health has been funded by NICHD R01HD053781 “Consequences of High Morbidity and Mortality in a Low-Income Country”; NICHD R01 HD044228 “AIDS/HIV Risk, Marriage and Sexual Relations in Malawi”; and NICHD R01HD/MH41713 “Gender, Conversational Networks and Dealing with STDs.”

Footnotes

See Bellan et al. (2013) for a recent modeling study that challenges this view.

Between 1998 and 2004 the MLSFH was known as the Malawi Diffusion and Ideational Change Project (MDICP).

A detailed description of the HIV testing procedure is available in Bignami-Van Assche et al. (2004).

Household wealth was measured using a constructed wealth index based on ownership of 14 household durable assets, achieved by principal component analysis (Filmer & Pritchett 2001)

Some individuals seroconverted during the survey interval, which could affect regression coefficients. However, with an incidence rate of around 0.7 per 100 person-years (Obare et al. 2009), this bias will be negligible.

Men in marriages with uxorilocal residence may return to their maternal village upon the cessation of a union, and they are therefore less likely to be interviewed in the next survey round. This could explain the lack of a significant statistical effect.

Caution is necessary, however, as formerly married women may, for example, have to turn to commercial sex work after marital dissolution as a means to provide for themselves (Vandenhoudt, et al. 2013).

Contributor Information

Philip Anglewicz, Email: panglewi@tulane.edu, Department of Global Health Systems and Development, School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine, Tulane University, 1440 Canal Street, Suite 2200, New Orleans, LA 70112.

Georges Reniers, Department of Population Health, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

References

- Allison Paul. Fixed Effects Regression Methods for Longitudinal Data Using SAS. SAS Institute Inc; Cary, NC, USA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Anglewicz Philip. Migration, marital change and HIV infection in Malawi. Demography. 2012;49(1):239–265. doi: 10.1007/s13524-011-0072-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anglewicz Philip, Clark Shelley. The effect of marriage and HIV status on condom use in rural Malawi. Social Science & Medicine. 2013;97:29–40. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anglewicz Philip, Adams Jimi, Onyango Francis, Watkins Susan, Kohler Hans-Peter. The Malawi Diffusion and Ideational Change Project 2004–06: Data collection, data quality, and analysis of attrition. Demographic Research. 2009;20(21):503–40. doi: 10.4054/demres.2009.20.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anglewicz Philip, Kohler Hans-Peter. Overestimating HIV infection: The construction and accuracy of subjective probabilities of HIV infection in rural Malawi. Demographic Research. 2009;20(6):65–96. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2009.20.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arpino Bruno, De Cao Elisabetta, Peracchi Franco. Using panel data for partial identification of human immunodeficiency virus prevalence when infection status is missing not at random. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society) 2013 First published online, 7 Oct 2013.

- Bellan Steve, Fiorella Kathryn, Melesse Dessalegn, et al. Extra-couple HIV transmission in sub-Saharan Africa: a mathematical modelling study of survey data. The Lancet. 2013;381(9877):1561–1569. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61960-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bignami-Van Assche Simona, Reniers Georges, Weinreb Alexander A. An assessment of the KDICP and MDICP data quality: Interviewer effects, question reliability and sample attrition. Demographic Research. 2003;S1:31–76. [Google Scholar]

- Bignami-Van Assche Simona, et al. SNP Working Paper No.7. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania; 2004. Research protocol for collecting STI and biomarker samples in Malawi. Retrieved from http://www.malawi.-pop.upenn.edu. [Google Scholar]

- Boerma J Ties, Urassa Mark, Nnko Soori, et al. Sociodemographic context of the AIDS epidemic in a rural area in Tanzania with a focus on people’s mobility and marriage. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2002;78(s1):i97–i105. doi: 10.1136/sti.78.suppl_1.i97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boileau Catherine, Clark Shelly, Assche Simona Bignami-Van, et al. Sexual and marital trajectories and HIV infection among ever-married women in rural Malawi. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2009;85(s1):i27–i33. doi: 10.1136/sti.2008.033969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bracher Michael, Santow Gigi, Watkins Susan. “Moving” and marrying: Modeling HIV infection among newly-weds in Malawi. Demographic Research. 2003;S1(6):207–246. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter LM, Kamali A, Ruberantwari A, Malamba SS, Whitworth JAG. Rates of HIV-1 transmission within marriage in rural Uganda in relation to the HIV sero-status of the partners. AIDS. 1999;13(9):1083–1089. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199906180-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark Shelley, Poulin Michelle, Kohler Hans-Peter. Marital aspirations, sexual behaviors, and HIV/AIDS in rural Malawi. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2009;71:396–416. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00607.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark Shelley, Bruce John, Dude Anne. Protecting young women from HIV/AIDS: the case against child and adolescent marriage. International Family Planning Perspectives. 2006;32:79–88. doi: 10.1363/3207906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Walque Damien, Kline Rachel. The Association between remarriage and HIV infection in 13 sub-Saharan African countries. Studies in Family Planning. 2012;43(1):1–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2012.00297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Walque Damian. Sero-discordant couples in five African countries: Implications for prevention strategies. Population and Development Review. 2007;33(3):501–23. [Google Scholar]

- Dunkle Kristen, Stephenson Rob, Chomba Etienne, et al. New heterosexually transmitted HIV infections in married or cohabiting couples in urban Zambia and Rwanda: An analysis of survey and clinical data. Lancet. 2008;371:2183–2191. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60953-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filmer Dion, Pritchett Lant. Estimating wealth effects without expenditure data or tears: an application to educational enrollments in states of India. Demography. 2001;38(1):115–132. doi: 10.1353/dem.2001.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floyd Sian, Crampin Amelia, Judith Glynn M, et al. The long-term social and economic impact of HIV on the spouses of infected individuals in northern Malawi. Tropical Medicine and International Health. 2008;13(4):1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glynn Judith, Carael Michael, Buve Anne, et al. HIV risk in relation to marriage in areas with high prevalence of HIV infection. Journal of the Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2003;33:526–35. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200308010-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregson Simon, Mason Peter R, Garnett Geoff P, et al. A rural HIV epidemic in Zimbabwe? Findings from a population-based survey. International journal of STD & AIDS. 2001;12(3):189–196. doi: 10.1258/0956462011917009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helleringer Stephane, Kohler Hans-Peter. Sexual network structure and the spread of HIV in Africa: evidence from Likoma Island, Malawi. AIDS. 2007;21(17):2323–2332. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328285df98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsaio Chang. Analysis of Panel Data. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Jahn Andreas, Floyd Sian, Crampin Amelia C, et al. Population-level effect of HIV on adult mortality and early evidence of reversal after introduction of antiretroviral therapy in Malawi. The Lancet. 2008;371(9624):1603–1611. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60693-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler Hans-Peter, Watkins Susan, Behrman Jere, et al. Cohort profile: The Malawi Longitudinal Study of Families and Health (MLSFH) International Journal of Epidemiology. 2014 doi: 10.1093/ije/dyu049. Forthcoming. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopman Ben, Nyamukapa Constance, Hallett Timothy, et al. Role of widows in the heterosexual transmission of HIV in Manicaland, Zimbabwe, 1998–2003. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2009;85:i41–i48. doi: 10.1136/sti.2008.033043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowrance David, Makombe Simon, Harries Anthony, et al. A public health approach to rapid scale-up of antiretroviral treatment in Malawi during 2004–2006. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2008;49(3):287–293. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181893ef0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackelprang RD, Bosire R, Guthrie BL, Choi RY, Liu A, Gatuguta A, Rositch AF, Kiarie JN, Farquhar C. High rates of relationship dissolution among heterosexual HIV-serodiscordant couples in Kenya. AIDS & Behavior. 2014;18(1):189–193. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0529-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mtika Mike, Doctor Henry. Matriliny, patriliny, and wealth flows in rural Malawi. African Sociological Review. 2002;6:71–97. [Google Scholar]

- National Statistics Office (NSO) [Malawi], and ORC Macro. Malawi Demographic and Helath Survey 2004. Calvertion, MD: NSO and ORC Macro; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- National Statistics Office (NSO) [Malawi], and ICF Macro. Malawi Demographic and Health Survey 2010. Zomba, Malawi, and Calverton, Maryland, USA: NSO and ICF Macro; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Obare Francis. Nonresponse in repeat population-based voluntary counseling and testing for HIV in rural Malawi. Demography. 2010;47(3):651–665. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obare Francis, Fleming Peter, Anglewicz Philip, et al. HIV incidence and learning one’s HIV status: evidence from repeat population-based voluntary counseling and testing in rural Malawi. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2009;85(2):139–144. doi: 10.1136/sti.2008.030320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pison Giles. La démographie de la polygamie. Population. 1986;41(1):93–122. [Google Scholar]

- Porter Laura, Hao Lingxin, Bishai David, et al. HIV status and union dissolution in sub-Saharan Africa: the case of Rakai, Uganda. Demography. 2004;41(3):465–482. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reniers Georges. Divorce and remarriage in rural Malawi. Demographic Research. 2003;S1:175–206. [Google Scholar]

- Reniers Georges. Marital strategies for regulating exposure to HIV. Demography. 2008;45(2):417–438. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reniers Georges, Armbruster Benjamin. HIV status awareness, partnership dissolution and HIV transmission in generalized epidemics. PloS One. 2012;7(12):e50669. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reniers Georges, Helleringer Stephane. Serosorting and the evaluation of HIV testing and counseling for HIV prevention in generalized epidemics. AIDS & Behavior. 2011;15(1):1–8. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9774-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reniers Georges, Tfaily Rania. Polygyny and HIV in Malawi. Demographic Research. 2008;19(53):1811. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2008.19.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith Kirsten, Watkins Susan. Perceptions of risk and strategies for prevention: Responses to HIV/AIDS in rural Malawi. Social Science and Medicine. 2005;60(3):649–60. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS. [Accessed on April 23rd 2013];Report on the global AIDS epidemic. 2008 http://www.unaids.org/en/dataanalysis/knowyourepidemic/

- Vandenhoudt HM, Langat L, Menten J, et al. Prevalence of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections among female sex workers in Kisumu, Western Kenya, 1997 and 2008. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e54953. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins Susan, Behrman Jere, Kohler Hans-Peter, Zulu Eliya. Introduction to ‘Research on demographic aspects of HIV/AIDS in rural Africa. Demographic Research. 2003;S1:1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins Susan. Navigating AIDS in rural Malawi. Population and Development Review. 2004;30(4):673–70. [Google Scholar]

- Welz Tanya, Hosegood Victoria, Jaffar Shabbar, et al. Continued very high prevalence of HIV infection in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: a population-based longitudinal study. AIDS. 2007;21(11):1467–1472. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3280ef6af2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO/UNAIDS/UNICEF. [Accessed on April 23rd 2013];Global HIV/AIDS Response: Epidemic update and health sector progress towards Universal Access 2011. 2011 http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/progress_report2011/en/index.html.