Abstract

Recent evidence indicates that limited availability and cytotoxicity have restricted the development of natural killer (NK) cells in adoptive cellular immunotherapy (ACI). While it has been reported that low-dose ionizing radiation (LDIR) could enhance the immune response in animal studies, the influence of LDIR at the cellular level has been less well defined. In this study, the authors aim to investigate the direct effects of LDIR on NK cells and the potential mechanism, and explore the application of activation and expansion of NK cells by LDIR in ACI. The authors found that expansion and cytotoxicity of NK cells were markedly augmented by LDIR. The levels of IFN-γ and TNF-α in the supernatants of cultured NK cells were significantly increased after LDIR. Additionally, the effect of the P38 inhibitor (SB203580) significantly decreased the expanded NK cell cytotoxicity, cytokine levels, and expression levels of FasL and perforin. These findings indicate that LDIR induces a direct expansion and activation of NK cells through possibly the P38-MAPK pathway, which provides a potential mechanism for stimulation of NK cells by LDIR and a novel but simplified approach for ACI.

Key words: : P38, adoptive cellular immunotherapy, low-dose ionizing radiation, natural killer cells

Introduction

The notion of using adoptive cellular immunotherapy (ACI) to treat malignant disease is an exciting prospect that has been widely discussed in the context of future personalized medicine. As one of the critical cellular components of ACI, natural killer (NK) cells exert a potent antitumor activity. The NK cell activity is regulated by signals from both activating and inhibitory receptors.1 The NK activating signal is mediated by several NK receptors, including NKG2D and natural cytotoxicity receptors.1,2 In contrast, NK inhibition is brought about by killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptors, which bind to MHC class I molecules on the target cell.1,3 Major histocompatibility (MHC) class I expression tends to be lost or downregulated in cancer cells4 and as a consequence, the NK inhibitory signal is abrogated, allowing the NK cells to become activated and kill malignant target cells.

NK cell immunotherapy has shown its potential role in the treatment of several cancers. However, low NK cell availability and limited expansion in vitro has restricted the development of NK cell immunotherapy for cancer. Although NK cells derived from the umbilical cord blood or NK-92 cells have been used for therapy,5,6 peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) collected from whole blood or leukapheresis are generally utilized as sources of NK cells.7,8 Studies have attempted to expand NK cells from PBMCs.7,9 NK cells are expanded in vitro using interleukin (IL)-2 or IL-15 before reinfusion into patients. Other NK cell-activating cytokines, such as IL-21, IL-12, and IL-18, and combinations of these cytokines have also been used, but the number and activity of NK cells required for its clinical application remain unclear.10 Other efforts include the use of genetically modified K562 target cells, magnetic beads coated with monoclonal anti-CD56 Ab and anti-CD3 Ab, as well as irradiated feeder cells such as PBMCs, Epstein-Barr virus-transformed lymphoblastoid cell lines, or engineered leukemic cell lines.11–13 However, these methods are expensive, time-consuming, complex, and adopting these methods on a large scale will be challenging.

Radiation at high doses is known to be detrimental, causing apoptosis and impairing immune function.14–16 In contrast to high-dose radiation, low-dose ionizing radiation (LDIR) (<0.2 Gy) can be beneficial to living organisms,17 as manifested by augmentation of the adaptive response,18,19 stimulation of immunological functions,20–22 prevention and cure of disease,23,24 and prolongation of lifespan.24,25 This interesting phenomenon exhibiting the beneficial effects of LDIR is often called radiation hormesis.26,27 During the last decade, a series of studies have demonstrated immune activation by LDIR, which has been considered as one of the primary factors responsible for the antitumor activity. Furthermore, activation of several immune cells, such as NK cells, has also been reported following the immune activation by LDIR. However, most of the previous studies were conducted mainly in animal models using whole-body radiation and little is known about whether LDIR has a direct effect on immune cells in vitro. Therefore, the authors hypothesized that a simplified strategy using LDIR would lead to effective expansion and a greater activity enhancement of NK cells. In the present study, the authors validated this approach and further explored the potential mechanisms of NK cell activation observed with the use of LDIR in vitro.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

PBMCs from 10 healthy donors (6 men, 4 women; median age: 36 (range: 30–38 years) were separated by an apheresis system (COBE SPECTRA™; Gambro BCT). This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Hospital of Jilin University. An informed consent was obtained from all subjects. The human chronic myeloid leukemia cell line K562 and the human acute myeloid leukemia cell line HL60, both obtained from the Cancer Center of the First Hospital of Jilin University (Jilin, China), were cultured in RPMI-1640 (Hyclone) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 U/mL streptomycin at 37°C with 5% CO2.

Expansion of the NK cells

Mononuclear cells separated from peripheral blood by Ficoll-Hypaque density centrifugation (Amersham Biosciences) were used to induce NK cells using cytokines under good manufacturing practice conditions. Briefly, to generate NK cells, PBMCs were cultured in an anti-CD16 (Beckman)-coated flask with the AIM-V medium supplemented with 5% auto-plasma, 700 U/mL IL-2 (Miltenyi), and 1 ng/mL OK432 (Shandong Lu Ya Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.) for 24 hours at 37°C. The cultured cells were then centrifuged and the supernatant was discarded. The cells were again cultured in the AIM-V (Invitrogen) medium supplemented with 5% auto-plasma and 700 U/mL IL-2 at 37°C for 14 days.

Phenotype analysis of NK cells

At different time points after induction culture as well as 24 hours after LDIR, cells were obtained for phenotype analysis using directly conjugated monoclonal antibodies against markers, including CD3-PerCP, CD69-PE, and CD56-APC (BD Biosciences). The cells (5×106) were incubated with various conjugated monoclonal antibodies for 30 minutes at 4°C and washed thrice in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), followed by flow cytometric analysis using the FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences), and the data were analyzed using SYSTEM statistical software (CellQuest). Those samples where NK cells had expanded up to 90% were selected for further study.

Irradiation

The NK cells were irradiated with 25, 75, 150, and 500 mGy X-rays from an X-ray generator (America; X-RAD320UM-SU) operated at 6 MV, at a source-to-surface distance of 60 cm, and at a dose rate of 12.5 mGy/min. The sham groups were treated similarly except for the irradiation.

Cell proliferation assay

After 14 days of induction culture, cells (5×106) from samples, wherein NK cells had expanded up to 90%, were seeded into 60-mm Petri dishes, which were then divided into the sham group and experimental groups with different doses of LDIR. Twenty-four hours after LDIR, cells were harvested from the Petri dishes and counted by dye exclusion with 0.4% trypan blue stain in a hemocytometer. At the same time, the purity of NK cells (CD56+, CD3−) was determined by flow cytometry. Consequently, the absolute number of NK cells was calculated in each group. The experiments were performed in triplicate.

Cytotoxicity assay of NK cells

The cytotoxic activity of the NK cells was measured using a lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) assay. K562 and HL60 were used as targets. Briefly, the target (T) cell suspension (5×106/mL) were added to each of the effector (E) cells, including the PBMCs, nonirradiated NK cells, or irradiated NK cells at E:T ratios of 5:1, 10:1, 20:1, or 40:1 in 96-well plates. The cells were incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 for 4 hours. Then, 60 μL LDH working solution was added to the culture supernatants. Finally, the absorbance readings were measured in a microplate reader (Bio-Rad) at 490 nm. Following this, the authors chose the best E:T ratio to detect the cytotoxic activity of NK cells irradiated with one of the four doses (25, 75, 150, and 500 mGy) at three different time points (2, 24, and 48 hours after LDIR). The percentage of NK cytotoxicity was calculated as follows: (Aexperimental−Aeffector−Atarget)/(Amaximum)×100%.

Cytokines secretion assay

Supernatants of the cell cultures were harvested and levels of IFN-γ and TNF-α were detected using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Boshide) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The total protein content of the cells was estimated by the bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Biyuntian) and used for normalizing the results.

Western blot analysis

The NK cells were collected from the culture flasks, washed with ice-cold PBS, and lysed at 4°C on ice for 30 minutes in a 100 μL lysis buffer (50 mM, pH 7.5 Tris-HCl, 0.25% deoxycholate, 1% Triton X-100, and 0.5 M NaCl). Protein concentration was determined by the Bradford dye binding assay using BSA as a standard. Protein samples (60 μg) were electrophoresed on a sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel. The proteins were then electrophoretically transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane in a transfer buffer. After incubation in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.2% Tween 20 and 5% nonfat dried milk at room temperature for 1 hour, the membrane was incubated with a primary antibody (rabbit anti-human P38-mitogen-activated protein kinases [MAPK]; PTG) at a 1:1000 dilution overnight at 4°C, followed by incubation with the mouse anti-rabbit IgG-HRP (PTG) for 1 hour at room temperature. Finally, the bound antibody was detected by chemiluminescence ECL, according to the instructions of the manufacturer (Amersham Pharmacia). Band intensity of the repeated western blots was determined by densitometry with ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health) and the mean value was obtained.

Statistical analysis

The data are presented as mean±standard deviation. The statistical significance of the difference between groups was evaluated by an analysis of variance, followed by a Student's t test using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software version 17.0 (IBM). A p-value of 0.05 was selected as the criterion for statistical significance.

Results

Expansion of NK cells in vitro can be augmented by LDIR

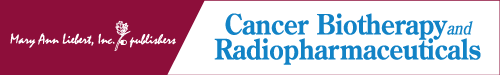

To generate NK cells, PBMCs were cultured with various cytokines and antibodies. The morphology of the induced NK cells was different from that of the PBMCs. Cellular volume was visibly increased with abundant cytoplasm and an enlarged nucleus after induction for 14 days. In addition, the number of cultured cells was increased after induction as well. The median purity of NK cells (CD56+, CD3−) was 92% (74–95%, n=10) (Fig. 1A). Consequently, a significant expansion of the NK cells was observed from day 7 to 14. After that, to address the direct effects of LDIR on NK cells in vitro, samples from 8 donors, wherein NK cells had expanded up to 90%, were selected for further study. The cultured cells were irradiated with 25, 75, 150, and 500 mGy X-rays. Compared with the sham group, there was no obvious change in the purity of NK cells in experimental groups with LDIR (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, when exposed to LDIR of 75 mGy (12.5 mGy/min), a significant increase in the absolute number of NK cells as compared to the sham group was observed (Fig. 1C). These results indicate that LDIR could efficiently augment the expansion of NK cells in vitro.

FIG. 1.

The proliferation of NK cells is enhanced by LDIR in vitro. The absolute number of cultured cells was analyzed after Trypan blue staining by using a hemocytometer. Simultaneously, the percentage of NK cells was identified through flow cytometry. Consequently, the absolute number of NK cells was calculated. (A) After 14 days of induction culture, cells (5×106) were obtained for analysis. One representative experiment out of 10 presented here, shows the percentage of NK cells (CD56+, CD3−) before and after induction. (B) After 14 days of induction culture, cells (5×106) from samples (n=8), wherein NK cells had expanded up to 90%, were divided into sham and experimental groups with different doses of LDIR. Twenty-four hours after LDIR, cells were harvested for analysis. One representative experiment out of 8 presented here, shows the percentage of NK cells (CD56+, CD3−) before and after 75 mGy LDIR. (C) The absolute number of NK cells after LDIR at different doses (25, 75, 150, and 500 mGy). A significant increase was observed in the 75 mGy group. “*” indicates that the mean number of NK cells in that group was significantly higher compared with the sham group (p<0.05). LDIR, low-dose ionizing radiation; NK, natural killer.

LDIR enhances the cytotoxic activity of NK cells

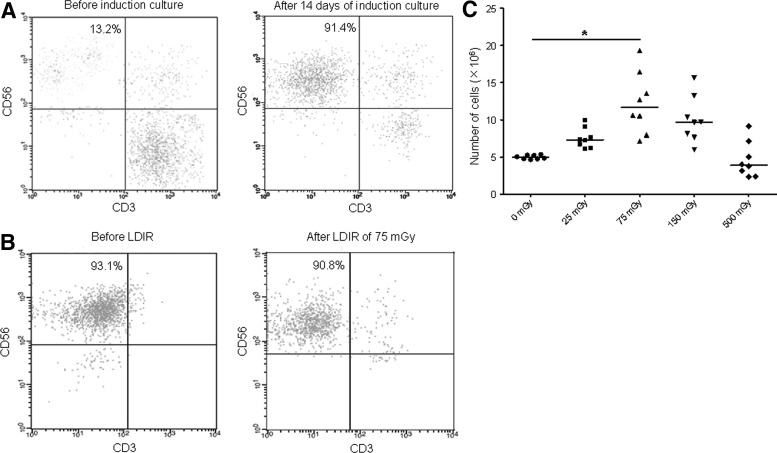

Cytotoxic activities of the irradiated expanded NK cells, the sham expanded NK cells, and the sham PBMCs were evaluated. K562 and HL60 cells were used as targets. As shown in Figure 2A, the cytotoxicity of the sham PBMCs against each target was found to be 10–20% at different effector to target cell (E:T) ratios. After induction for 14 days, the expanded NK cells exhibited a strong cytocidal activity toward each target. When exposed to 75 mGy X-rays, the cytotoxicity effect of the expanded NK cells harvested at 24 hours post-LDIR was significantly stronger compared with the sham group in a dose-dependent manner. At the E:T ratios of 10:1 and 20:1, the percentage of lysis in the irradiated groups was greater than 70%, fivefold higher compared with the sham PBMC group.

FIG. 2.

LDIR enhances the cytotoxic activity of the expanded NK cells. The cytotoxic activity of the expanded NK cells was measured using an LDH assay. K562 and HL60 were used as targets. (A) The cytotoxic activity of the irradiated expanded NK cells harvested 24 hours post-LDIR, the sham expanded NK cells, and the sham PBMCs at different E:T ratios (5:1, 10:1, 20:1, and 40:1) was measured. (B) At an optimized ratio of 10:1, cytotoxic activities of the expanded NK cells irradiated by various doses (25, 75, 150, and 500 mGy) at different time points (2, 24, and 48 hours after LDIR) were measured. All experiments were independently performed using 8 donors. Data are presented as mean±SD. “*” indicates that the cytotoxicity in that group was significantly higher compared with the sham PBMCs group (p<0.05); “**” indicates that the cytotoxicity in that group was significantly higher compared with the sham group (p<0.05). PBMCs, peripheral blood mononuclear cells; SD, standard deviation.

To further identify the most effective radiation dose, the authors chose 4 different doses: 25, 75, 150, and 500 mGy at an optimized ratio of 10:1. Moreover, the cytotoxic activity of the irradiated expanded NK cells against each target was evaluated after 2, 24, and 48 hours of LDIR. As shown in Figure 2B, after 24 and 48 hours of LDIR, the cytotoxic activities were observed to be higher compared with the sham group, especially in the 75 mGy group after 24 hours of LDIR. In contrast, when given 500 mGy, the cytotoxic function of the expanded NK cells was visibly decreased. These results indicate that 75 mGy was the optimal dose to enhance the cytotoxic activity of NK cells by LDIR.

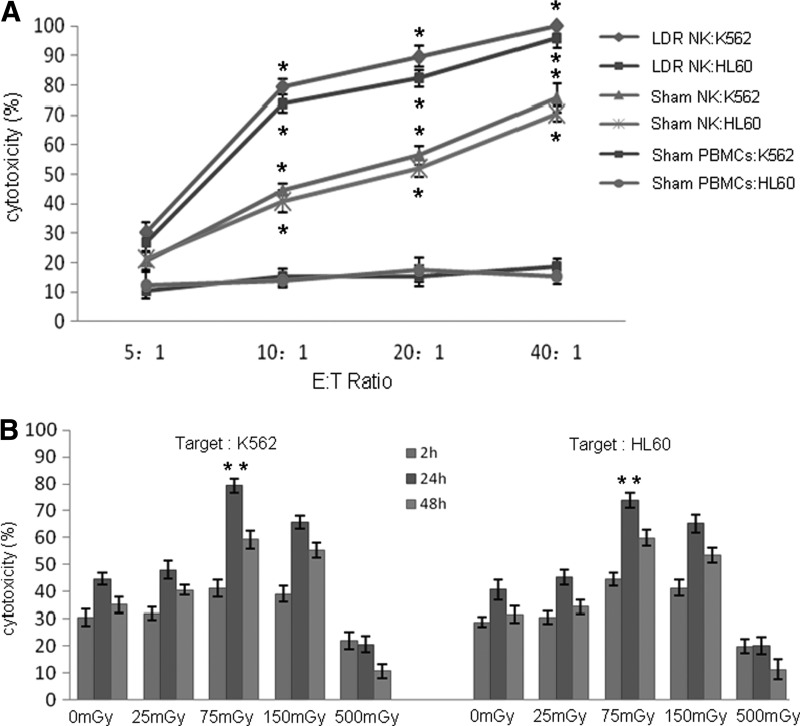

LDIR increases the cytokine production of NK cells

Previous studies have shown that the cytocidal effect of NK cells is a result of direct cell killing or an indirect function through cytokine production to engage other arms of the immune system. Therefore, the supernatants of the irradiated expanded NK cell cultures were harvested 24 hours after irradiation at various doses and the levels of IFN-γ and TNF-α were evaluated using an ELISA kit. As shown in Figure 3, the levels of IFN-γ and TNF-α in supernatants were visibly increased after LDIR. The increase was more pronounced in the group that was irradiated with 75 mGy, which was consistent with the pattern of increasing the cytotoxic activity of NK cells after LDIR at various doses. These results indicate that LDIR could significantly increase cytokine secretion by NK cells.

FIG. 3.

LDIR increases cytokines production by the expanded NK cells. Twenty-four hours after irradiation at various doses, supernatants of the cell cultures were harvested, and the levels of IFN-γ and TNF-α were detected by an ELISA kit. Comparison of secretion levels of IFN-γ and TNF-α by the expanded NK cells between the sham and other dose groups (25, 75, 150, and 500 mGy) is shown. Statistical analysis was performed using mean values from 8 donors. “*” Indicates that the cytokine level in that group was significantly higher compared with the sham group (p<0.05). ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

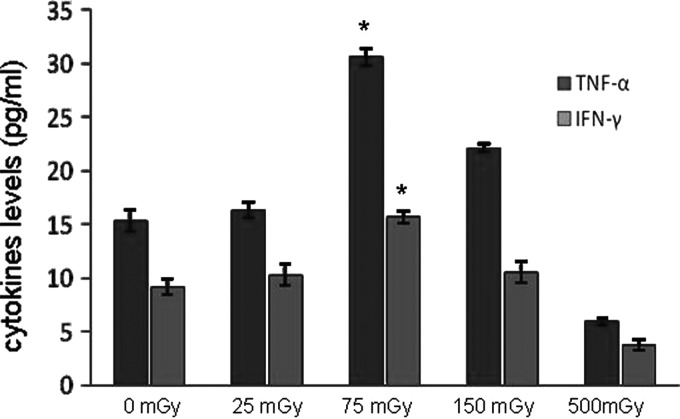

The P38-MAPK pathway is involved in the effect of LDIR on NK cells

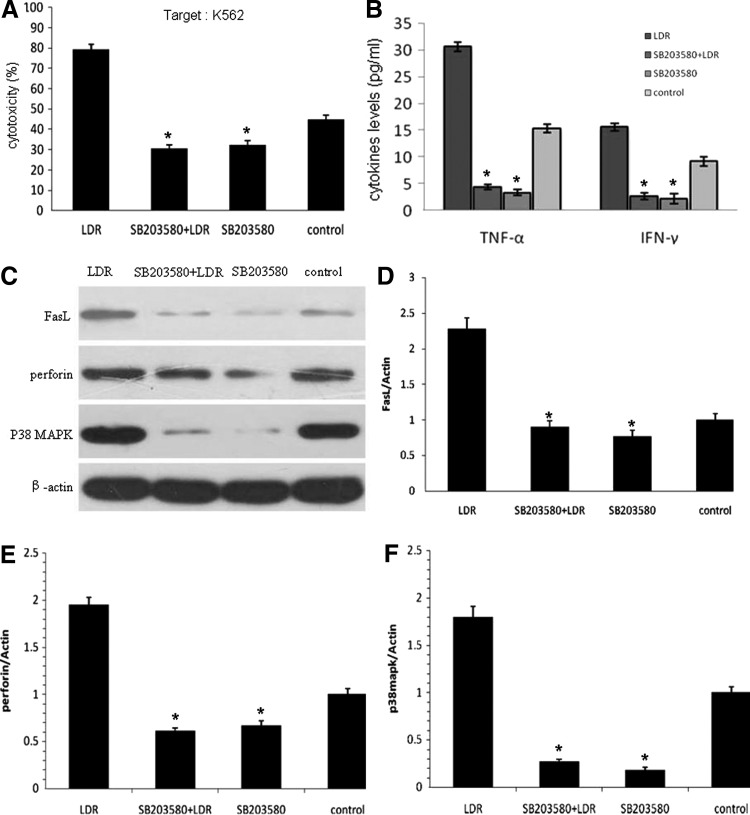

To investigate the potential molecular mechanism involved in the LDIR effect on NK cells, the authors used SB203580, a specific inhibitor of P38, to identify whether the P38-MAPK pathway was involved in the augmentation of NK cell cytotoxicity. The expanded NK cells were divided into four groups: D1 (LDIR 75 mGy), D2 (SB203580+LDIR 75 mGy), D3 (SB203580), and the control group. As shown in Figure 4A, the suppressive effect of SB203580 in the D2 and D3 groups significantly diminished the cytotoxic activity of the expanded NK cells on K562 cells as compared to the D1 group, at an optimized E:T ratio of 10:1. Moreover, the level of IFN-γ and TNF-α in supernatants was remarkably downregulated after P38 inhibition (Fig. 4B). The authors also found that when the activity of P38 was inhibited, the expression levels of FasL and perforin in the expanded NK cells were markedly decreased (Fig. 4C–F), which correlated positively with the results of cytotoxic activity of NK cells. These results indicate that the inhibition of P38 could reverse the effect of LDIR on NK cells.

FIG. 4.

The effect of LDIR on the expanded NK cells after inhibition of P38. The expanded NK cells were pretreated with or without 25 μmol/L SB203580 for 12 hours and then irradiated with 75 mGy X-rays, or treated similarly except for the irradiation. Twenty-four hours after irradiation, the cells were harvested for the following analyses. (A) The cytotoxic activity of the expanded NK cells irradiated by 75 mGy was diminished by the inhibition of P38 at an optimized E:T ratio of 10:1. (B) The cytokine levels of the irradiated expanded NK cells decreased after the inhibition of P38. (C–F) The expression of NK cytocidal activity-related proteins decreased after the inhibition of P38, which was detected by western blot, followed by quantitative analysis. All experiments were independently performed using 8 donors. Data are presented as mean±SD. “*” Indicates that the results in that group were significantly lower compared with the LDIR group (p<0.05).

Discussion

NK cells are critical to the innate immune system. The role of NK cells is analogous to that of cytotoxic T cells in the adaptive immune response. NK cells provide rapid responses to the presence of tumor cells, without the need to recognize the specific tumor antigens. It has been reported that the adoptive transfer of NK cells is a promising strategy for cancer treatment.28 Since NK cells comprise only 5–15% of peripheral blood lymphocytes, a sufficient number of highly enriched NK cells is urgently required for the therapeutic use of NK cells in the clinical setting. Sporadic data from animal studies using whole-body radiation have shown that LDIR could enhance the immune response through augmentation of NK cell cytotoxicity.29,30 Additionally, studies have reported that LDIR could stimulate endocrine and central nervous systems, which indirectly influence NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity. However, the direct influence of LDIR on NK cells at the cellular level has not been well defined and the potential mechanism is still unclear. In this study, the direct effect of LDIR on the expansion and activity augmentation of NK cells from healthy donors in vitro was studied, which could facilitate the understanding of the mechanism of NK cell activation by LDIR and provide a broader clinical application of NK cells.

It was encouraging that significant augmentation of expansion and cytotoxic function was detected when NK cells were irradiated by LDIR directly. The results were different from the study by Sonn et al., which showed that only significant augmentation of cytotoxicity, but not proliferation, was detected when NK cells were stimulated with low-dose IL-2 before irradiation.31 The authors presumed that the lower level of IL-2 used in that study might be one of the reasons for the difference. The further mechanism still requires to be investigated. In this study, the authors have developed a novel strategy using LDIR to generate increased expansion and activation of NK cell populations from PBMCs that can be easily used clinically, with minimal resources and at a low cost. In contrast to conventional approaches, this method requires only that the NK cells be exposed to LDIR after 14 days of culture with various cytokines and antibodies to achieve significant levels of expansion.

Other issues to be considered in the effect of LDIR on NK cells include the optimal dose of LDIR and the time point for cytotoxicity enhancement of NK cells. In this study, the most intense augmentation of antitumor cytotoxicity was observed in the expanded NK cells after 24 hours with 75 mGy irradiation. In contrast, when given 500 mGy, the cytotoxic function of the NK cells was visibly decreased. These data corroborate the fact that the optimal radiation dose can significantly increase the cytotoxic activity of the NK cells at the optimized time point, which leads to the generation of immune-enhancing effects. This supports the use of ACI after 24 hours by LDIR at 75 mGy in clinical practice to enhance the antitumor activity of NK cells.

Although the results presented above demonstrated the efficacy of LDIR on NK cells, the possible mechanism is still unknown. There are two main molecular mechanisms of NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity, one perforin based and the other Fas based.32,33 In the present study, it was shown that expression of the perforin and Fas ligands increased in NK cells after stimulation by LDIR. On the other hand, NK cells can produce a number of cytokines that mediated the antineoplastic activity of these cells by either directly suppressing proliferation and/or killing tumor targets (e.g., IL-1β, IFN-γ, and TNF-α) or by stimulating neighboring cells (in a paracrine manner) to secrete cytocidal factors (e.g., IL-1β, IL-12, and IFN-γ). Therefore, the production of IFN-γ and TNF-α was also evaluated in this study to investigate the mechanism of NK cell activation by LDIR. Consequently, the authors found that the production of IFN-γ and TNF-α by the expanded NK cells increased after LDIR, which was consistent with the pattern of increasing the cytotoxic activity of the NK cells. As a result, LDIR could induce activation of NK cells by affecting the cell killing function and cytokine production.

So far, experimental studies on the effectiveness of LDIR on immune response are still at their early stages. The molecular mechanisms responsible for immune enhancement led by LDIR remain elusive. MAPKs are a family of serine/threonine kinases that regulate a variety of cellular activities. They are important mediators of signal transduction from the cell surface to the nucleus. Three major classes have been described, namely, P38, JNKs, and ERKs. LDIR has been shown to activate all three MAPKs in various cell types.34–36 LDIR activates cytokine receptors leading to activation of downstream MAPK pathways, thereby activating transcription of many genes. This results in modulation of cell proliferation, apoptosis, production of cytokines, and transcriptional regulation. In the field of immunology, it is becoming clear that P38-MAPK participates in several aspects of immune regulation. Chini et al. have conducted a study on regulation of P38-MAPK during NK cell activation.37 The role of P38 in the cytotoxic function of NK cells was tested by treatment of NK cells with the P38-specific inhibitor, SB203580. The results suggested that the P38-MAPK pathway is stimulated during the development of NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity. In another study by Trotta et al., the data indicated that P38, but not JNK1, was involved in the molecular mechanisms regulating NK cell cytotoxic functions.38 Several studies have also demonstrated that the activation of P38 is associated with the regulation of target cell-induced cytokine expression.

The authors have confirmed that LDIR can enhance the proliferation and cytotoxicity of NK cells, while the P38-MAPK pathway has been reported to be related to the regulation of NK cell cytotoxic functions. Therefore, this pathway may be involved in cytotoxic activity augmentation of NK cells under the influence of LDIR. In the present study, the authors observed that inhibition of P38 by SB203580 could reverse the effects of LDIR, namely, cytotoxic activity enhancement of the expanded NK cells, suggesting that LDIR could increase the immune activity of NK cells by activation of the P38-MAPK pathway. However, the precise molecular mechanisms responsible for the immune enhancement by LDIR require further investigation.

In conclusion, the authors have developed a novel strategy using LDIR to generate highly expanded and activated NK cell populations from PBMCs, which can be easily adapted to clinical use with minimal resources and at a low cost. The expansion and cytotoxic function of NK cells were both directly stimulated by LDIR, possibly mediated by the P38-MAPK pathway. In this study, the authors suggest that these findings may contribute to future research on other types of immune cells to improve cancer outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Supported, in part, by the Ministry of Education Key Project of Science and Technology (311015) and the Bethune Foundation of Jilin University (201202, 2013023).

Disclosure Statement

There are no existing conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Koepsell SA, Miller JS, McKenna DH., Jr Natural killer cells: A review of manufacturing and clinical utility. Transfusion 2013;53:404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moretta A, Bottino C, Vitale M, et al. Activating receptors and coreceptors involved in human natural killer cell-mediated cytolysis. Annu Rev Immunol 2001;19:197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Long EO. Regulation of immune responses through inhibitory receptors. Annu Rev Immunol 1999;17:875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marincola FM, Jaffee EM, Hicklin DJ, et al. Escape of human solid tumors from T-cell recognition: Molecular mechanisms and functional significance. Adv Immunol 2000;74:181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spanholtz J, Preijers F, Tordoir M, et al. Clinical-grade generation of active NK cells from cord blood hematopoietic progenitor cells for immunotherapy using a closed-system culture process. PLoS One 2011;6:e20740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arai S, Meagher R, Swearingen M, et al. Infusion of the allogeneic cell line NK-92 in patients with advanced renal cell cancer or melanoma: A phase I trial. Cytotherapy 2008;10:625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carlens S, Gilljam M, Chambers BJ, et al. A new method for in vitro expansion of cytotoxic human CD32-CD56+natural killer cells. Hum Immunol 2001;62:1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sutlu T, Stellan B, Gilljam M, et al. Clinical grade, large-scale, feeder-free expansion of highly active human natural killer cells for adoptive immunotherapy using an automated bioreactor. Cytotherapy 2010;12:1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alici E, Sutlu T, Björkstrand B, et al. Autologous antitumor activity by NK cells expanded from myeloma patients using GMP-compliant components. Blood 2008;111:3155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Torelli GF, Guarini A, Maggio R, et al. Expansion of natural killer cells with lytic activity against autologous blasts from adult and pediatric acute lymphoid leukemia patients in complete hematologic remission. Haematologica 2005;90:785. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siegler U, Meyer-Monard S, Jörger S, et al. Good manufacturing practice-compliant cell sorting and large-scale expansion of single KIR-positive alloreactive human natural killer cells for multiple infusions to leukemia patients. Cytotherapy 2010;12:750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berg M, Lundqvist A, McCoy P Jr., et al. Clinical-grade ex vivo-expanded human natural killer cells up-regulate activating receptors and death receptor ligands and have enhanced cytolytic activity against tumor cells. Cytotherapy 2009;11:341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lapteva N, Durett AG, Sun J, et al. Large-scale ex vivo expansion and characterization of natural killer cells for clinical applications. Cytotherapy 2012;14:1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horie K, Kubo K, Yonezawa M. p53 dependency of radio-adaptive responses in endogenous spleen colonies and peripheral blood-cell counts in C57BL mice. J Radiat Res 2002;43:353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Payne CM, Bjore CG, Jr., Schultz DA. Change in the frequency of apoptosis after low- and high-dose X-irradiation of human lymphocytes. J Leukoc Biol 1992;52:433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang L, Snyder AR, Morgan WF. Radiation-induced genomic instability and its implications for radiation carcinogenesis. Oncogene 2003;22:5848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luckey TD. Physiological benefits from low levels of ionizing radiation. Health Phys 1982;43:771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iyer R, Lehnert BE. Low dose, low-LET ionizing radiation-induced radioadaptation and associated early responses in unirradiated cells. Mutat Res 2002;503:1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miura Y, Abe K, Urano S, et al. Adaptive response and the influence of ageing: Effects of low-dose irradiation on cell growth of cultured glial cells. Int J Radiat Biol 2002;78:913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu SZ, Liu WH, Sun JB. Radiation hormesis: Its expression in the immune system. Health Phys 1987;52:579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ina Y, Sakai K. Activation of immunological network by chronic low-dose-rate irradiation in wild-type mouse strains: Analysis of immune cell populations and surface molecules. Int J Radiat Biol 2005;81:721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lacoste-Collin L, Jozan S, Cances-Lauwers V, et al. Effect of continuous irradiation with a very low dose of gamma rays on life span and the immune system in SJL mice prone to B-cell lymphoma. Radiat Res 2007;168:725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ishii K, Hosoi Y, Yamada S, et al. Decreased incidence of thymic lymphoma in AKR mice as a result of chronic, fractionated low-dose total-body X irradiation. Radiat Res 1996;146:582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ina Y, Tanooka H, Yamada T, et al. Suppression of thymic lymphoma induction by life-long low-dose-rate irradiation accompanied by immune activation in C57BL/6 mice. Radiat Res 2005;163:153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ina Y, Sakai K. Prolongation of life span associated with immunological modification by chronic low-dose-rate irradiation in MRL-lpr/lpr mice. Radiat Res 2004;161:168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu SZ. Radiation hormesis. A new concept in radiological science. Chin Med J (Engl) 1989;102:750. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Macklis RM. Radithor and the era of mild radium therapy. JAMA 1990;264:614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller JS, Soignier Y, Panoskaltsis-Mortari A, et al. Successful adoptive transfer and in vivo expansion of human haploidentical NK cells in patients with cancer. Blood 2005;105:3051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hashimoto S, Shirato H, Hosokawa M, et al. The suppression of metastases and the change in host immune response after low-dose total-body irradiation in tumor-bearing rats. Radiat Res 1999;151:717. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cheda A, Wrembel-Wargocka J, Lisiak E, et al. Single low doses of x rays inhibit the development of experimental tumor metastases and trigger the activities of NK cells in mice. Radiat Res 2004;161:335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sonn CH, Choi JR, Kim TJ, et al. Augmentation of natural cytotoxicity by chronic low-dose ionizing radiation in murine natural killer cells primed by IL-2. J Radiat Res 2012;53:823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Darmon AJ, Nicholson DW, Bleackley RC. Activation of the apoptotic protease CPP32 by cytotoxic T-cell-derived granzyme B. Nature 1995;377:446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hallett WH, Ames E, Motarjemi M, et al. Sensitization of tumor cells to NK cell-mediated killing by proteasome inhibition. J Immunol 2008;180:163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dent P, Yacoub A, Fisher PB, et al. MAPK pathways in radiation responses. Oncogene 2003;22:5885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Narang H, Krishna M. Mitogen activated protein kinases: Specificity of response to dose of ionizing radiation in Liver. J Radiat Res (Tokyo) 2004;45:1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Narang H, Krishna M. Effect of nitric oxide donor and gamma irradiation on MAPK signaling in murine peritoneal macrophages. J Cell Biochem 2008;103:576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chini CC, Boos MD, Dick CJ, et al. Regulation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase during NK cell activation. Eur J Immunol 2000;30:2791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Trotta R, Fettucciari K, Azzoni L, et al. Differential role of p38 and c-Jun N-terminal kinase 1 mitogen-activated protein kinases in NK cell cytotoxicity. J Immunol 2000;165:1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]