Abstract

Autophagy is an evolutionally conserved catabolic process that recycles nutrients upon starvation and maintains cellular energy homeostasis1–3. Its acute regulation by nutrient sensing signaling pathways is well described, but its longer-term transcriptional regulation is not. The nuclear receptors PPARα and FXR are activated in the fasted or fed liver, respectively4,5. Here we show that both regulate hepatic autophagy. Pharmacologic activation of PPARα reverses the normal suppression of autophagy in the fed state, inducing autophagic lipid degradation, or lipophagy. This response is lost in PPARα knockout (PPARα−/−) mice, which are partially defective in the induction of autophagy by fasting. Pharmacologic activation of the bile acid receptor FXR strongly suppresses the induction of autophagy in the fasting state, and this response is absent in FXR knockout (FXR−/−) mice, which show a partial defect in suppression of hepatic autophagy in the fed state. PPARα and FXR compete for binding to shared sites in autophagic gene promoters, with opposite transcriptional outputs. These results reveal complementary, interlocking mechanisms for regulation of autophagy by nutrient status.

Overlapping networks govern both acute and longer-term responses to nutrients. In the fasted liver, glucagon induces both rapid glycogen breakdown and transcriptional activation of gluconeogenesis6. Nutrient deprivation also acutely regulates nutrient reclamation by autophagy7–9. Among several transcription factors that have been linked to the control of autophagy at the transcriptional level, activation of the basic Helix-Loop-Helix transcription factor EB (TFEB) by fasting is the best described10.

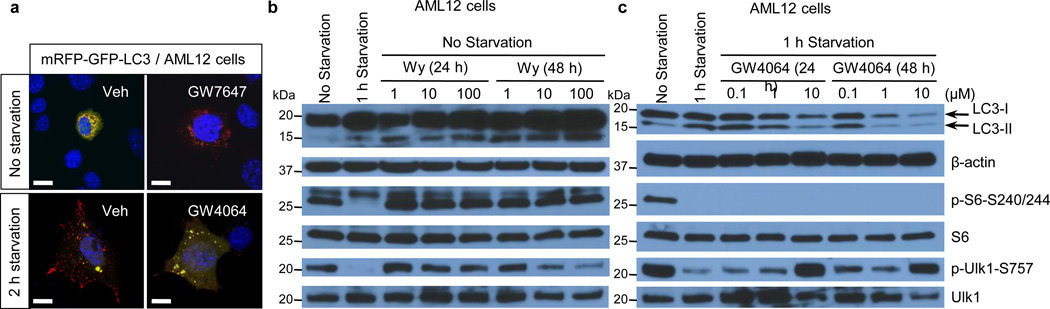

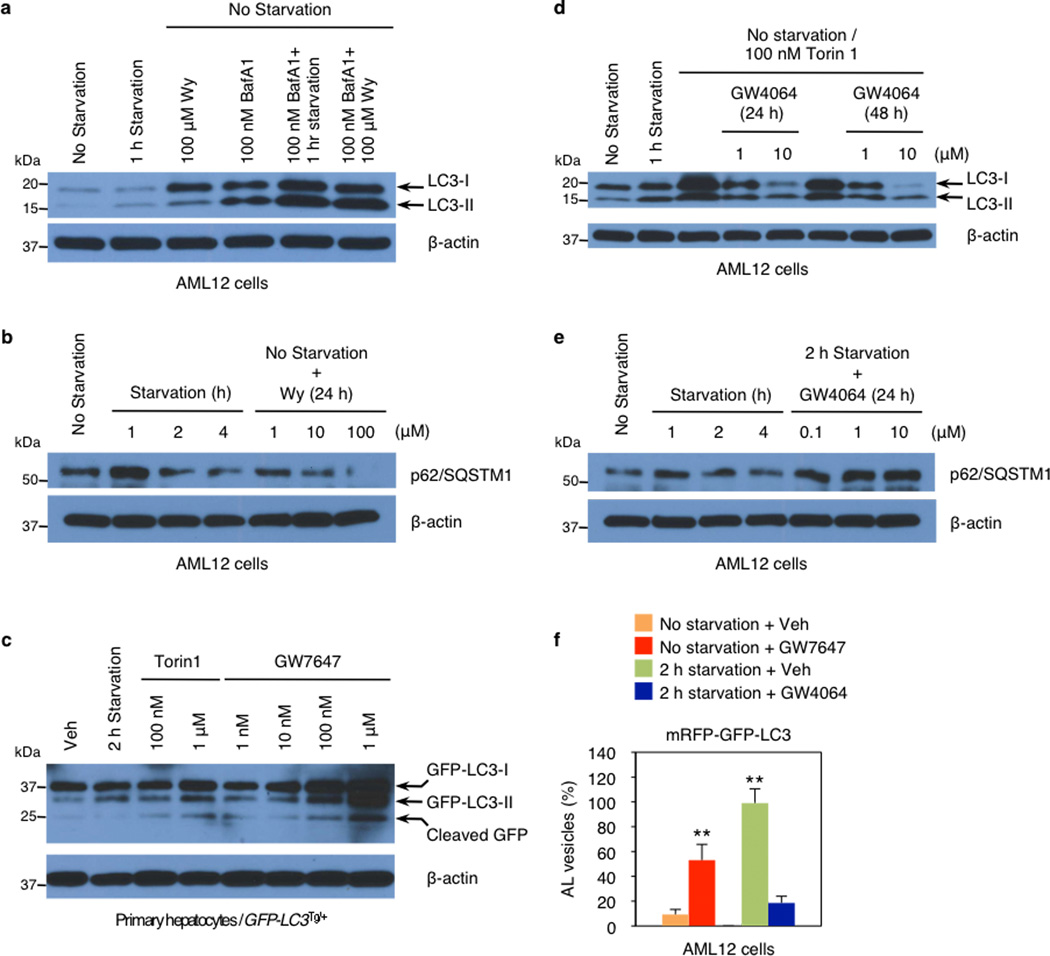

Nutrient sensing nuclear receptors are key integrators of metabolic responses. PPARα is activated by fatty acids in the fasted state, promoting fatty acid oxidation4,11,12. In the fed state, FXR is activated by bile acids returning to the liver along with nutrients, suppressing gluconeogenesis13. We hypothesized that PPARα and FXR would directly regulate autophagy, and initially tested the impact of their pharmacologic activation in the murine hepatocyte cell line AML12 expressing a triple mRFP-GFP-LC3 fusion protein14–16. In autophagosomes, the combination of both RFP and GFP in the triple fusion yields yellow fluorescence, whereas autolysosomal delivery results in red. As expected, the yellow fluorescence in normally cultured cells was converted to red by acute nutrient deprivation (Fig. 1, Extended Data Fig. 1f). The FXR agonist GW406417 prevented this process in the nutrient deprived cells, while the PPARα agonist GW764718 mimicked it in non-starved cells (Fig. 1, Extended Data Fig. 1f). Extensive cell based studies of LC3-II levels and other indicators of autophagy confirmed that these responses are dose and time dependent, and indicated that they are not dependent on altered mTORC1 activity, but are associated with a decrease in the inhibitory phosphorylation of Ulk119 in response to PPARα activation, and an increase in response to FXR activation (Fig. 1b–c, Extended Data Fig. 2a–d). Indeed, GW7647 induces autophagic flux even in non-starved cells, whereas GW4064 suppresses it even in starved, or torin120 treated cells (Extended Data Fig. 1a–e). Activation of FXR by bile acids also suppresses LC3-II induction (Extended Data Fig. 2c).

Figure 1. Activation of PPARα or FXR controls autophagic flux in murine hepatocytes.

Representative confocal images of AML12 cells transiently expressing mRFP-GFP-LC3 plasmids followed by treatment of vehicle (Veh), GW7647 (100 nM), or GW4064 (10 µM) for 24 h (out of 30 cells per condition). Cells were starved for 2 h (lower panels: Veh or GW4064-treated cells). DNA was counterstained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar, 20 µm. b and c, Immunoblotting of autophagy (LC3-I/II and p-Ulk1S757) or mTORC1 activity (p-S6S240/244) in AML12 cells treated with indicated doses of Wy-14,643 (Wy) or GW4064 for 24 h or 48 h. GW4064-treated cells were starved for 1 h.

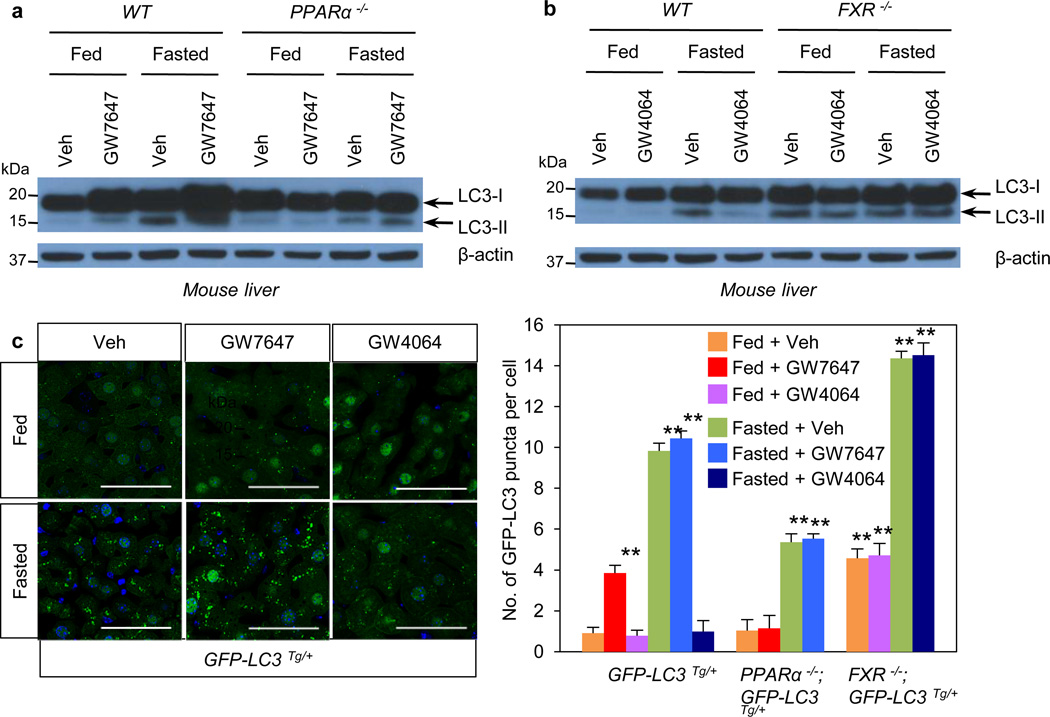

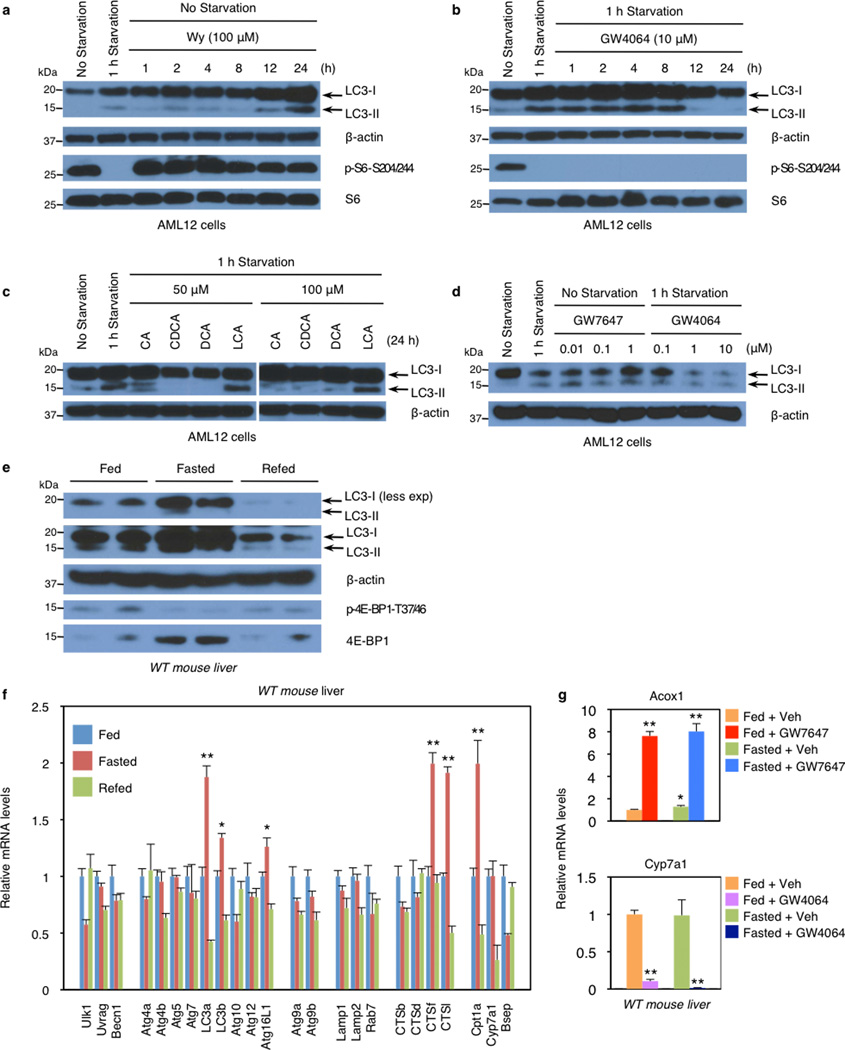

In livers of chow fed or fasted wild-type C57BL/6J (WT), LC3-II levels were increased in the fasted state (Fig. 2a, Extended Data Fig. 2e), and mRNA expression of LC3a and additional autophagic genes was also induced (Fig. 2b, Extended Data Fig. 2f, Fig. 3a–c). PPARα agonist treatment strongly increased levels of both LC3-I and LC3-II in the fed state in WT, but not PPARα−/− mice21, and both were further elevated in the fasted state (Fig. 2a, Extended Data Fig. 3b). GW7647 also induced LC3a mRNA expression in the fed and fasted states, and these responses were lost in PPARα−/− mice (Extended Data Fig. 3a).

Figure 2. Activation of PPARα or FXR controls autophagy in liver.

a and b, Fed or fasted WT PPARα−/−, or FXR−/− mice treated with Veh, GW7647 or GW4064. LC3 Immunoblots of liver samples. Lanes are pooled (n=5 per group). c, Representative confocal images (out of 9 tissues sections per condition) of liver GFP-LC3 puncta (green: autophagosomes), DAPI (blue: DNA). Fed or fasted GFP-LC3Tg/+, bigenic PPARα−/−; GFP-LC3Tg/+, or FXR−/−; GFP-LC3Tg/+ mice treated with Veh, GW7647, or GW4064. Fixed liver samples analyzed by confocal microscopy. Scale bar, 50 µm. GFP puncta per cell are quantified in graph. Data represent mean±s.e.m. of 9 tissue sections. (n=3 per group, **P < 0.01 vs Fed GFP-LC3Tg/+ mice treated with Veh). Statistics by two-tailed t-test.

In fed or fasted mice treated with the FXR agonist, induction of LC3-II protein in the fasted state was suppressed in WT, but not FXR−/− livers (Fig. 2b, Extended Data Fig. 3d). LC3-II levels were unaffected by GW4064 in fed and fasted FXR−/−mice22 (Fig. 2c). At the mRNA level, GW4064 completely suppressed the induction of LC3b in the fasted state (Extended Data Fig. 3c). As expected, GW4064 treatment also suppressed Cyp7a1, but induced SHP expression in both the fasted and fed states in WT, but not FXR−/− mice (Extended Data Fig. 2g, 3c).

These results were confirmed using GFP-LC3 transgenic mice (GFP-LC3Tg/+)15,16,23 and GFP-LC3Tg/+ plus PPARα−/− or FXR−/− double mutants. Green puncta indicating autophagosome formation were increased in fasted GFP-LC3Tg/+ mice (Fig. 2c). The PPARα agonist also significantly increased puncta in the fed LC3Tg/+ mice, but not in the PPARα−/− double mutants (Fig. 2c, Extended Data Fig. 3e). In the opposite direction, the FXR agonist strongly suppressed induction of puncta in the fasted LC3Tg/+ mice, but not in the fed state, and had no effect in the FXR−/− double mutants (Fig. 2c, Extended Data Fig. 3e). The induction of puncta by fasting was significantly lower in the PPARα−/−; GFP-LC3Tg/+ mutants, whereas their number in the fed state was significantly increased in the FXR−/−; GFP-LC3Tg/+ mutants (Fig. 2c, Extended Data Fig. 3e). These partially defective responses in the double mutants demonstrate that PPARα is required for the full induction of autophagy by fasting, and FXR is required for its full suppression by feeding.

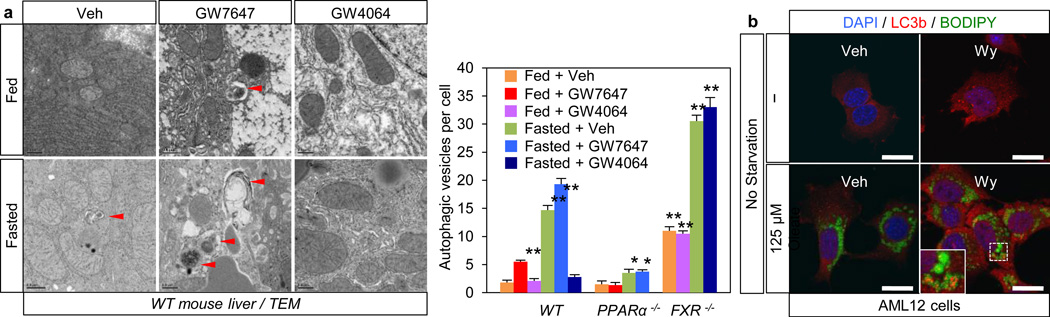

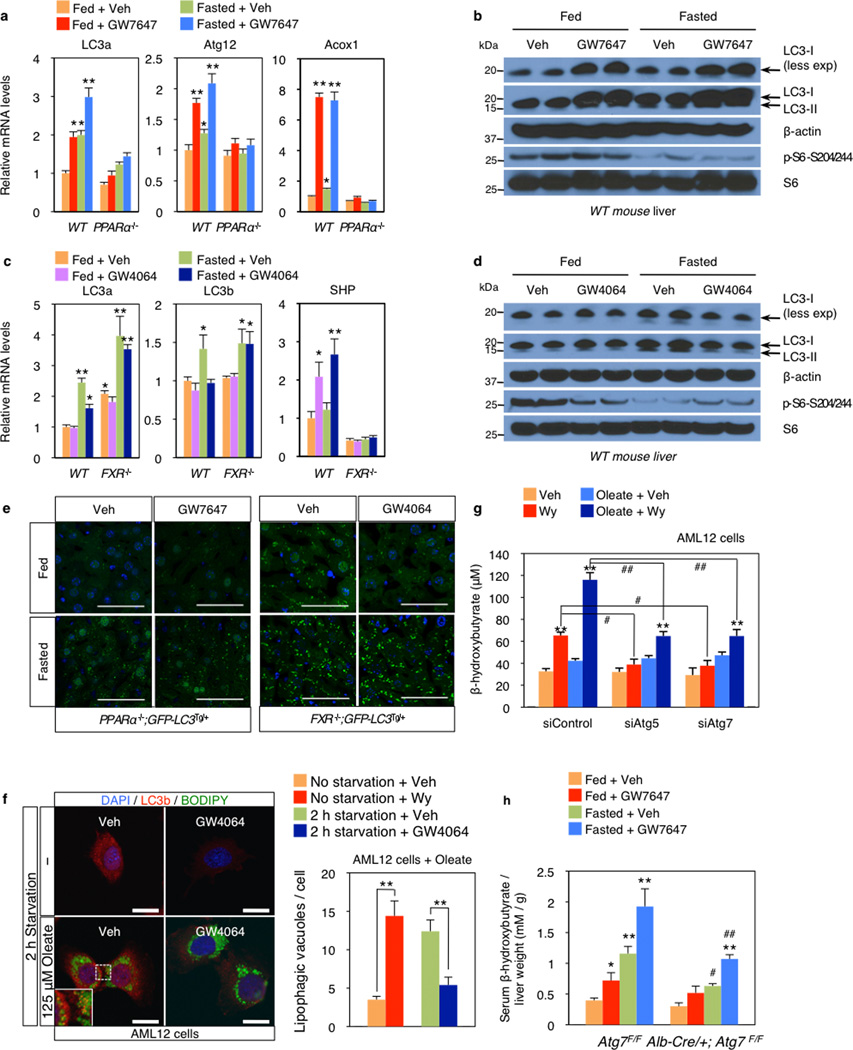

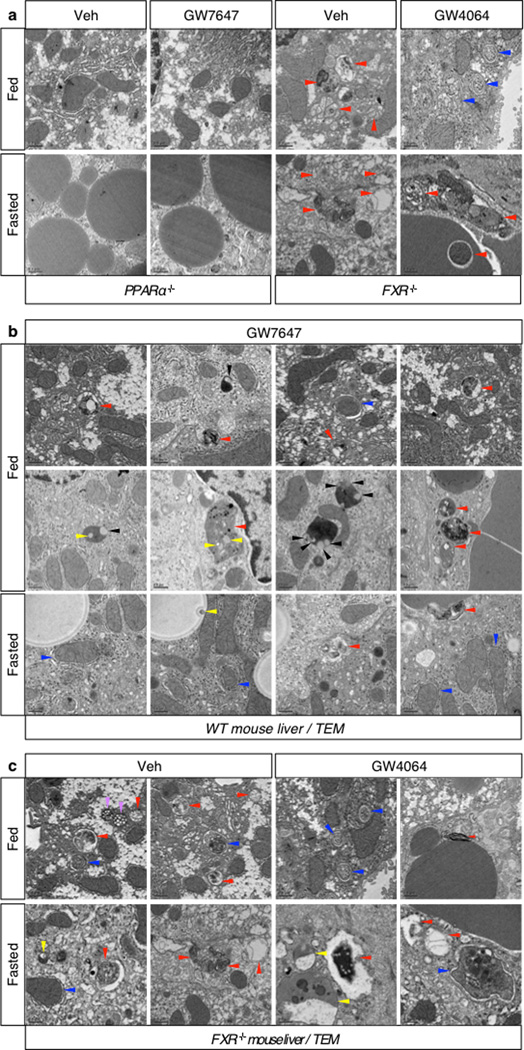

In agonist or vehicle treated fed and fasted livers, quantitation of autophagic vesicles by transmission electron microscopy confirmed an increase in response to GW7647 in the fed state, and a strong decrease in response to GW4064 in the fasted state (Fig. 3a). Moreover, fasted livers of PPARα−/− mice show compromised formation of autophagic vesicles but increased numbers and size of lipid droplets. Conversely, livers of fed FXR−/− mice show enhanced formation of autophagic vesicles (Extended Data Fig. 4a, c). Autophagosomes induced by the PPARα agonist frequently contained lipid droplets, suggesting an increase in lipophagy consistent with the role of this receptor in fatty acid oxidation (Extended Data Fig. 4b). This was confirmed in AML12 cells treated with or without oleate to induce lipid droplet formation, and then either starved or not and also treated with vehicle, Wy-14,643 or GW4064. Visualization of LC3 (red) revealed colocalization with BODIPY 493/503 (green) labeled lipid droplets in the starved cells, as expected, and also in the non-fasted, Wy-14,643 treated cells (Fig. 3b, Extended Data Fig. 3f). In accord with a functional role for the induction of lipophagy, specific knockdown of either Atg5 or Atg7 significantly blunted the increase in fatty acid oxidation in response to Wy-14,643 in basal and oleate treated AML12 cells, as indicated by ketone body production (Extended Data Fig. 3g). Similarly, both fasting and GW7647 induced serum β-hydroxybutryate levels in control Atg7 F/F mice24, and both responses were decreased in liver specific Atg7 knockouts (Extended Data Fig. 3h).

Figure 3. PPARα and FXR control autophagic vesicle formation in liver.

a, Representative liver electron micrographs. Fed or fasted WT, PPARα−/−, or FXR−/− mice treated with Veh, GW7647 or GW4064. Red arrowhead (autolysosome). Scale bar, 0.5 µm. Autophagic vesicles (autophagosome/autolysosome) per cell quantified in graph. Data represent mean±s.e.m. for 30 cells per group (n=3 per group, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs Veh treated fed WT). Statistics by two-tailed t-test. b, Co-localization of BODIPY 493/503 (green) with LC3 (red) in AML12 cells treated with Veh or 10 µM Wy-14,643 (Wy) for 24 h and cultured with or without 125 µM oleate. DNA stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar, 20 µm.

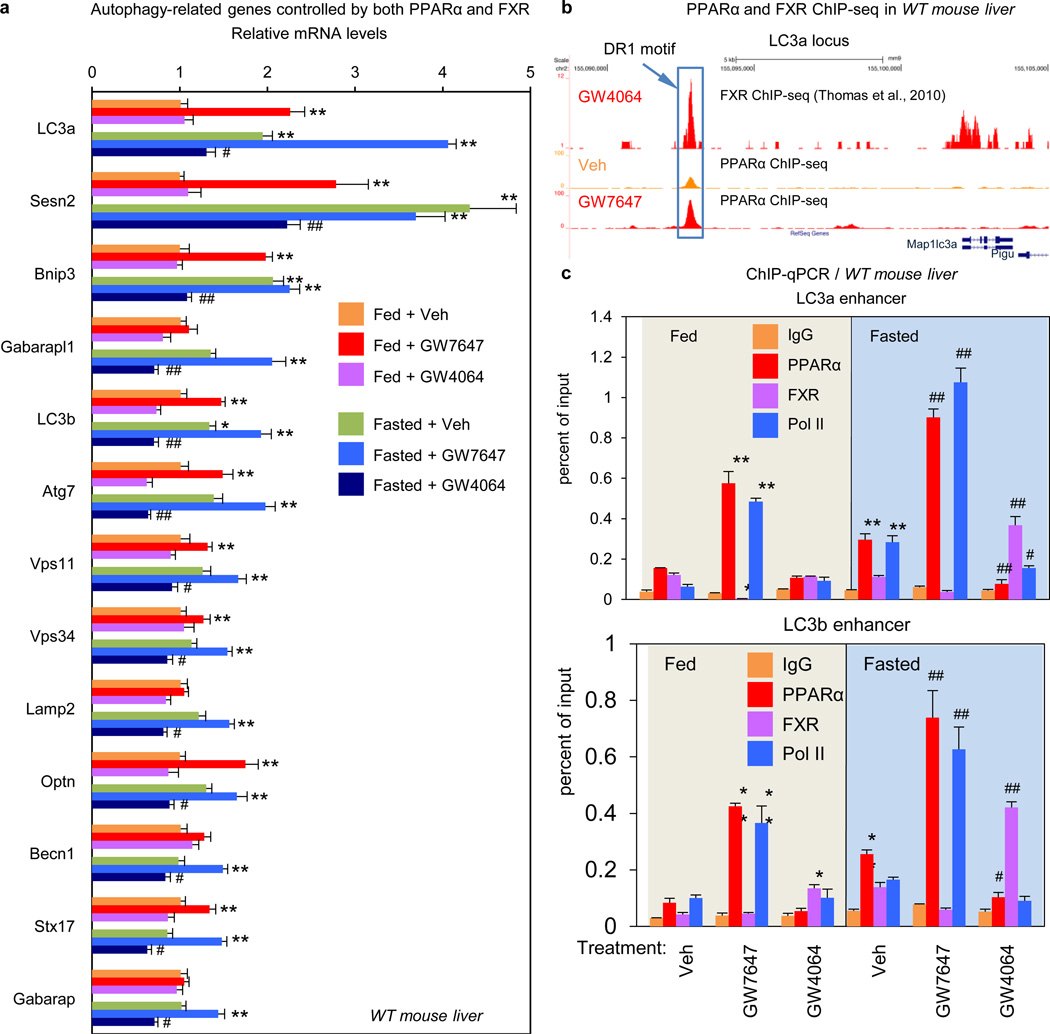

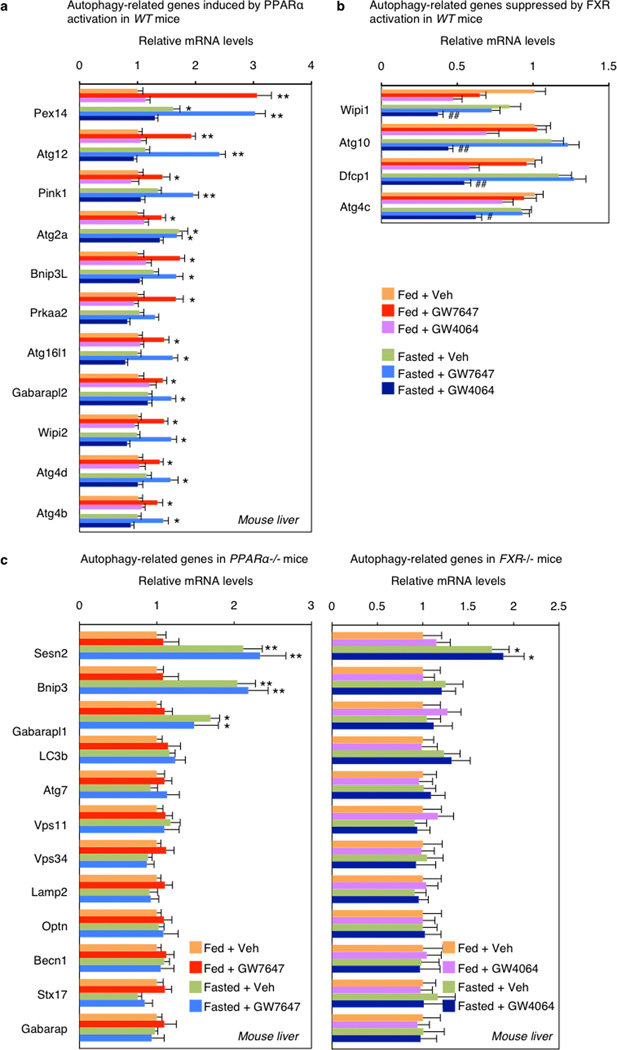

Direct transcriptional effects are the most likely explanation for the impact of both PPARα and FXR on autophagy. Initial results confirmed that total LC3 protein levels are increased and decreased in response to fasting and refeeding, and mRNA expression of LC3a and LC3b and several other autophagic genes is increased in the fasted state and decreased in the refed state (Extended Data Fig. 2e, f). Among a core panel of 63 autophagy-related genes (Supp. Table 1), 13 were both induced by GW7647 and repressed by GW4064 in WT mice, with both responses lost in relevant knockout mice (Fig. 4a, Extended data Fig. 5c), 11 more were responsive only to GW7647, while 4 responded only to GW4064 (Extended Data Fig. 5a, b).

Figure 4. Transcriptional coordination of hepatic autophagy by nutrient sensing nuclear receptors in vivo.

a, Hepatic autophagy gene expression. Fed or fasted WT mice treated with Veh, GW7647 or GW4064. (n=5 per group). b, PPARα and FXR ChIP-seq tracks for LC3a. Fed WT mice treated with Veh or GW764. (n=4 per group). Boxed peaks contain DR1 motif. c, PPARα/FXR binding to LC3a/b DR1 region determined by ChIP-qPCR. (n=3 per group). (panels in a and c, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs Veh treated fed WT; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 vs Veh treated fasted WT). In panel a and c, Data represent mean±s.e.m. Statistics by two-tailed t-test.

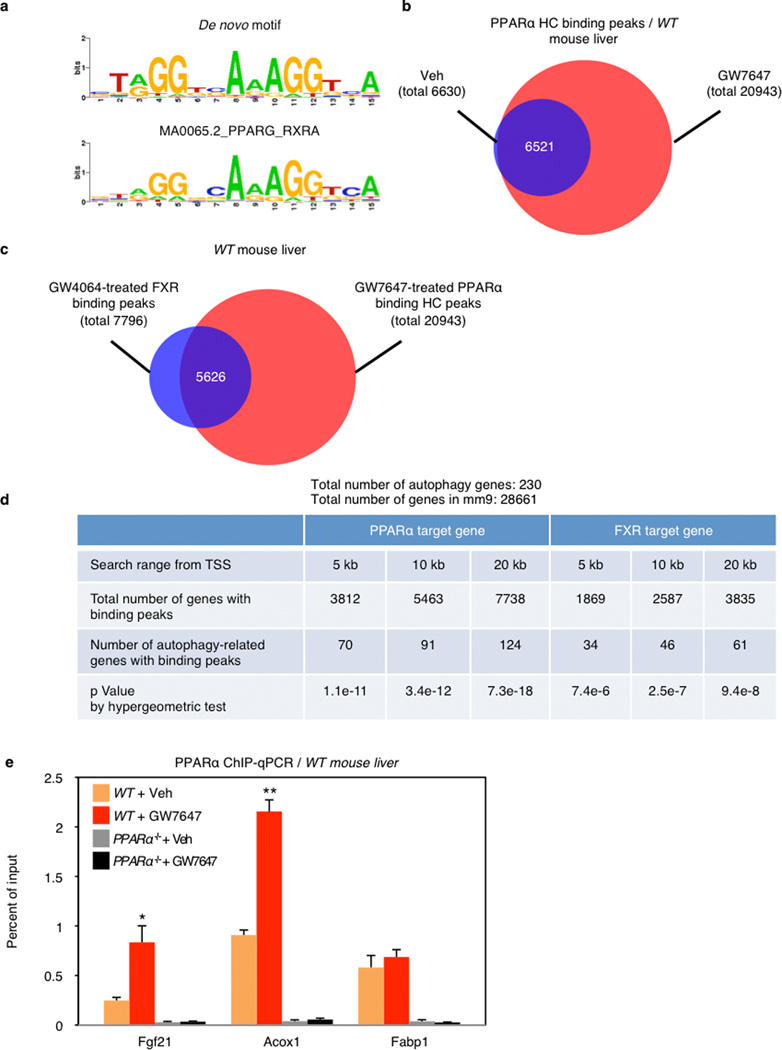

To define the basis for PPARα induction of autophagy-related genes, we determined the mouse liver PPARα cistrome with or without GW7647. The most significantly enriched binding motif among identified peaks was the known PPARα-RXR binding site (DR1), as expected, and nearly all of the peaks were absent in the PPARα−/− cistromes (Extended Data Fig. 6a, 7a, c). PPARα binding sites on core autophagy machinery gene loci as well as many regulatory and effector genes were confirmed by standard PPARα ChIP-qPCR analysis (Extended Data Fig. 6e, 7). Many of the peaks on these genes (Extended Data Fig. 7a), and a further panel of key autophagy components including Pink1, Optn, Vps11 and Becn1 (Supplementary Fig. 1) were further enhanced by GW7647 treatment, demonstrating that PPARα agonist treatment not only generates new binding sites, but also further increases PPARα recruitment to specific target genes (Extended Data Fig 6d).

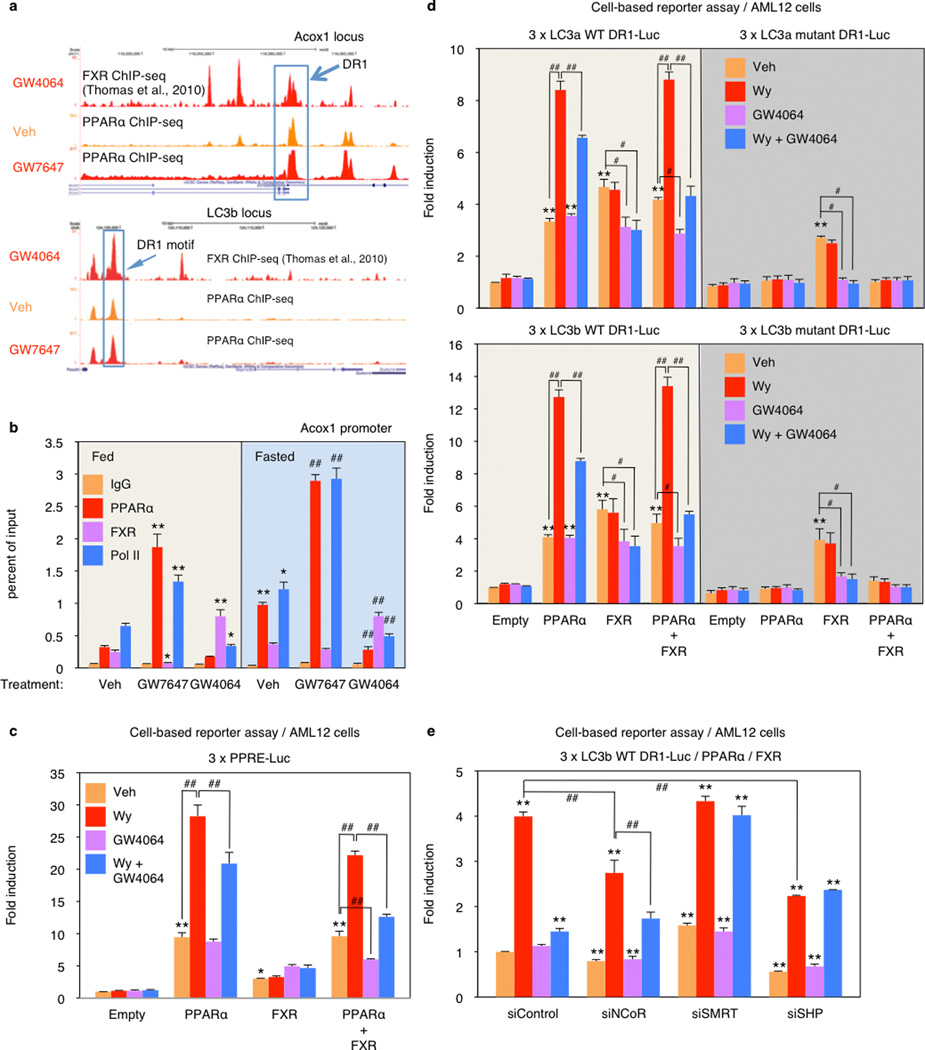

The PPARα cistrome shows that at least 124 of an extended 230 autophagy-related gene list have at least one receptor binding peak within 20 kb from the transcription start site, while a FXR25 cistrome shows 61 potential targets (Extended Data Fig. 6d). A hypergeometric test confirmed that both are highly enriched relative to a random gene pool (Extended Data Fig. 6d). Intriguingly, approximately 27% of agonist induced PPARα binding peaks overlapped with 72% of agonist induced FXR binding peaks (Extended Data Fig. 6c). Consistent with this, peaks for PPARα and FXR directly overlap at 41 out of the 230 extended autophagic target genes, as exemplified by LC3a (Fig. 4b) and LC3b (Extended Data Fig. 8a). This was unexpected, based on their very different direct (PPARα - DR1) and inverted (FXR - IR1) repeat consensus binding sites. However, FXR has also been reported to bind DR1 sites in the ApoCIII26 and ApoA27 promoters, where it acts as a ligand-dependent transcriptional repressor, raising the prospect that it could repress autophagic gene expression via a similar mechanism.

Quantitative assessment confirmed that GW7646 treatment increased PPARα binding to peaks containing a single DR1 site in the LC3a and LC3b enhancers (Fig. 4c) and the ApoA1 promoter (Extended Data Fig. 8a, b), and increased RNA polymerase II recruitment to the genes. Thus, in the fed state, the increased PPARα binding was able to overcome the relatively silent chromatin state and decrease FXR occupancy for the LC3a and Acox1 DR1 sites. In the opposite direction, GW4064 did not have much impact on the already silent chromatin in the fed state, in accord with the functional studies (Figs. 2, 3). In the transcriptionally active fasted state, however, the FXR agonist significantly increased FXR binding, decreased RNA polymerase II recruitment, and also decreased PPARα binding to all 3 elements (Fig. 4c, Extended Data Fig. 8b). Overall, these results closely match the functional results and indicate that pharmacologic activation of each nutrient sensing nuclear receptor can overcome the chromatin state imposed by the opposite nutrient signal (fed for PPARα and fasted for FXR). They also indicate that PPARα and FXR compete for binding to single sites in some chromatin states.

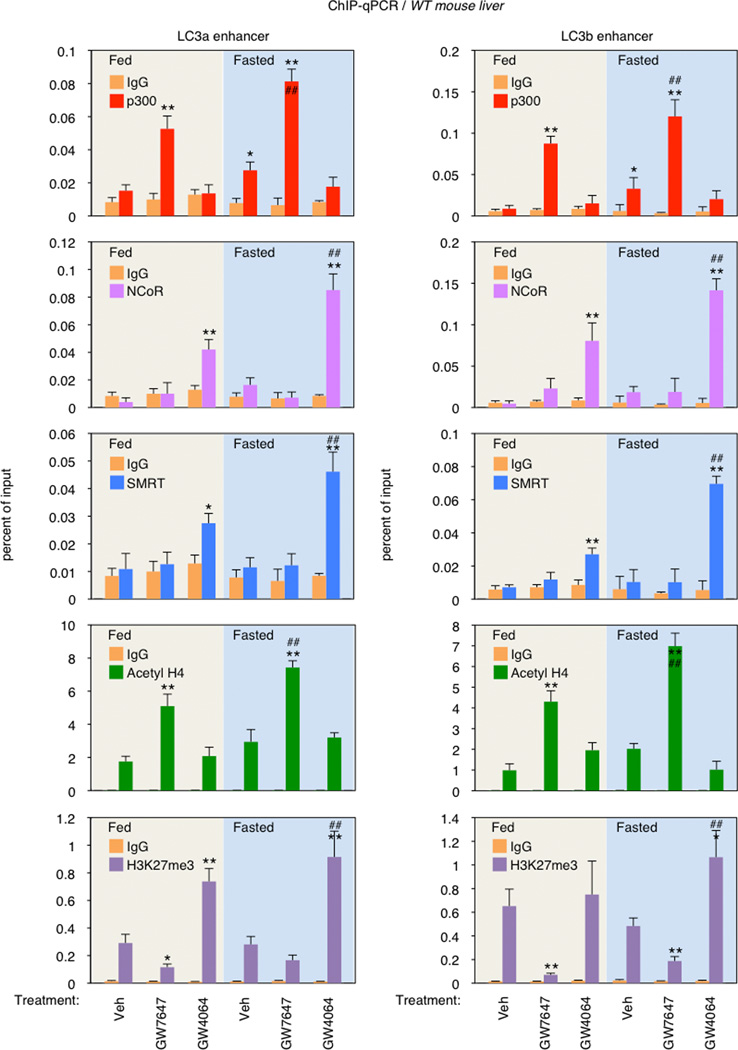

To test this, we focused on the DR1 motifs in the regulatory region of the LC3a and LC3b genes. Cell-based reporter assays with promoter constructs including only the DR1 motifs confirmed the opposite responses, with the PPARα agonist further inducing, and the FXR agonist suppressing luciferase expression relative to the increased basal transactivation observed with both PPARα or FXR alone (Extended Data Fig. 8d). In the presence of both receptors, GW4064 suppressed both basal and Wy-14,643 induced expression. Similar results were also observed using a conventional PPAR response element reporter construct (3 × PPRE-Luc) (Extended Data Fig. 8c). Mutation of the LC3a or LC3b DR-1 elements blocked all responses to PPARα, as expected, but only diminished the responses to FXR (Extended Data Fig. 8d). The basis for this residual response, which cannot be correlated with direct FXR or FXR/RXR binding in vitro, is unclear. The ability of GW4064 to inhibit PPARα dependent transactivation of the LC3b DR1 motif is dependent on corepressors, since it was blocked by siRNA knockdown of either SMRT or SHP (Extended Data Fig. 8e). Consistent with these functional results, GW7647 treatment increased p300 coactivator recruitment to the DR1 region of LC3a and LC3b enhancers and increased histone H4 acetylation, an active chromatin mark. In contrast, GW4064 treatment increased NCoR and SMRT corepressor binding and the repressive H3K27trimethyl mark at the same DR1 regulatory region, particularly in the fasted state (Extended Data Fig. 9). Overall, we conclude that PPARα and FXR directly compete for binding to the same DR-1 elements at autophagic, and likely additional promoters, with opposite transcriptional outputs.

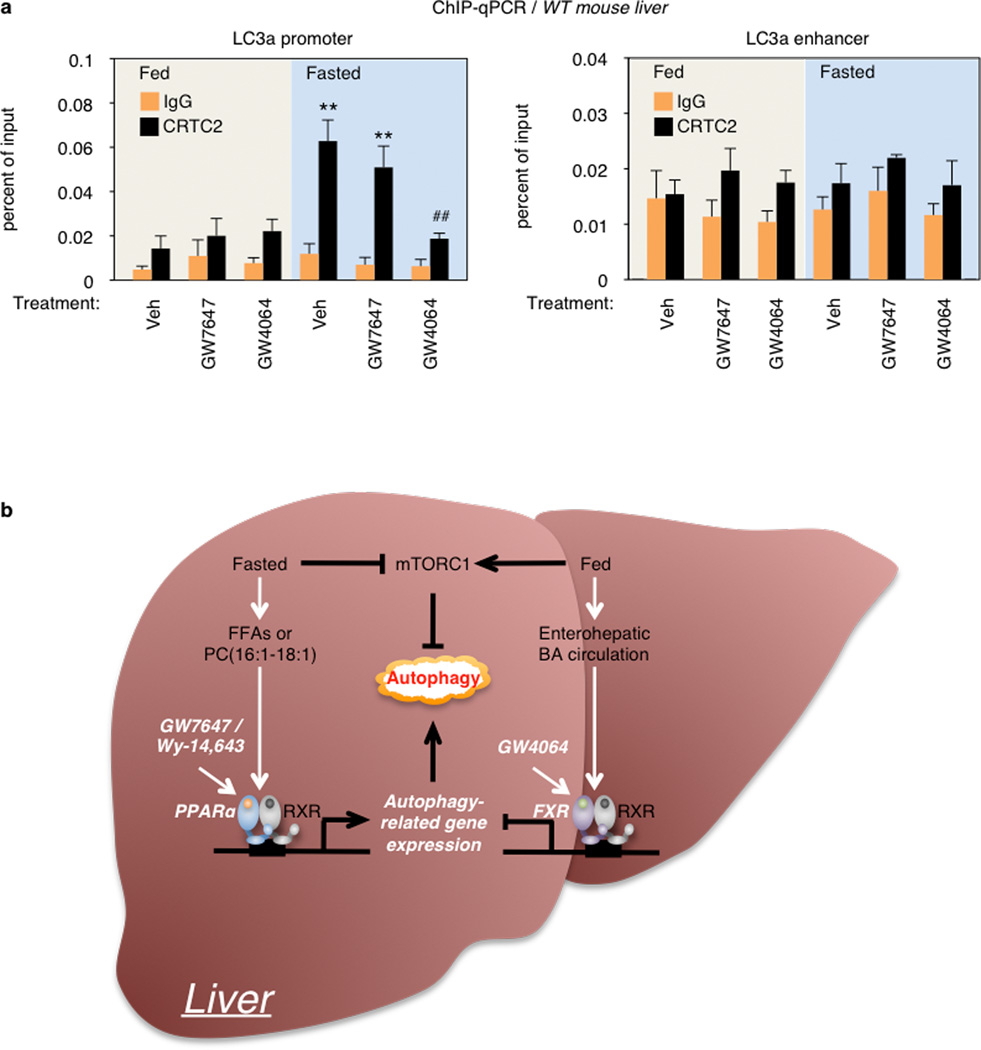

This mechanism is distinct from, but complementary to the inhibition of CRTC2 recruitment described in the accompanying manuscript. Thus, CRTC2 was not significantly recruited to the LC3a DR1 enhancer, as expected, but we confirmed the ability of GW4064 treatment to decrease CRTC2 occupancy to its proximal promoter site in the fasted state (Extended Data Fig. 10a).

These results define novel mechanisms for regulation of autophagy by nutrient sensing nuclear receptors (Extended Data Fig. 10b). Pharmacologic activation of either PPARα or FXR robustly impacts hepatic autophagy. GW7467 activates it even in the fed state, which is associated with an increase in lipophagy. GW4064 potently suppresses the process in the fasted state. The significantly blunted autophagic responses of PPARα and FXR knockouts to fasting or feeding, respectively, strongly confirm the physiologic relevance of the pharmacologically defined responses.

Both nuclear receptors directly induce or repress extensive panels of autophagy-related genes in accord with the overall responses. However, the impact of the synthetic agonists appears greater than the magnitude of the transcriptional responses, suggesting a role for less direct effects. We did not observe effects on mTOR, the dominant upstream regulator of autophagy. However, there were alterations in the inhibitory phosphorylation of Ulk1 S757 that would be consistent with such effects. In addition, induction of the transcriptional repressor SHP is a well-described mechanism for FXR dependent suppression of genes of bile acid biosynthesis28,29. However, preliminary results indicate that the suppressive effects of GW4064 are maintained in SHP−/− mice (data not shown).

These results reveal intersecting and complementary genomic circuits in which PPARα and FXR respectively induce and suppress hepatic autophagy (Extended Data Fig. 10b). They further integrate autophagy, which is often associated with more extreme nutrient stresses, with more physiologic nutrient responses. They also establish PPARα and FXR as potential targets for therapeutic modulation autophagy, which may be useful for liver or other metabolic tissues and could impact the pathogenesis of a wide range of human diseases.

Methods

Materials

Reagents were obtained from the following sources: C57BL/6J mice and PPARα−/− mice from the Jackson Laboratory; FXR−/− and GFP-LC3 transgenic (Tg) mice were previously described35,36; Antibodies to LC3 (NB600–1384) from Novus Biologicals; rabbit antibodies to phospho-Ser240/244 S6 (cat. # 5364), S6 (cat. # 2217), phospho-Thr37/46–4E–BP1 (cat. # 2855), 4E–BP1 (cat. # 9452), anti-mouse IgG-HRP (cat. # 7076) and β-actin (cat. # 5125) from Cell Signaling Technology; antibody to normal rabbit IgG (sc-2027), PPARα (sc-9000x), FXR (sc-13063x), Pol II (sc-899x), p300 (sc-585x), CRTC2/TORC2 (sc-6714x) and anti-rabbit IgG-HRP (sc-2370) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology; antibody to Histone H3K27me3 (cat. # 39155) from ACTIVE MOTIF; GW7647 and Wy-14,643 from Cayman chemicals; GW4064 from Tocris bioscience; Bafilomycin A1 from Enzo Life Science; AML12 cells from ATCC (CRL-2254); GFP antibody (cat. # 11814460001), PhosSTOP (Cat. # 04906837001), and Complete Protease Cocktail (Cat. # 11836170001) from Roche; ITS (Cat. # 41400–045), Lipofectamine 2000 (Cat. # 11668019), BODIPY 493/503 (D-3922), Alexa Fluor 594 goat anti-rabbit IgG (Cat. # A11037), Stealth siRNAs-NCoR (NcoR1, MSS208758), SMRT (NcoR2, MSS20912), SHP (NR0b2, MSS239500), and HIGH_GC from Invitrogen; mRFP-GFP-LC3(ptfLC3) plasmid, a gift of T. Yoshimori (Addgene plasmid # 21074); anti-rabbit p62/SQSTM1 (Cat. # P0067), anti-rabbit LC3B (Cat. # L7543), Oleic-Acid-Albumin (Cat. # O3008–5ML), and Dexamethasone (Cat. # D4902–25MG) from Sigma; Protein A Sepharose CL-48 (Cat. # 17–0780–01) from GE Healthcare; VECTASHIELD (Cat. # H-1200) from Vector Laboratories; SacI-HF (Cat. # R3156S) and BglII (Cat. # R0144S) from New England Biolabs; Pierce™ BCA Protein Assay Kit (Cat. # 23227) from Thermo Scientific; SMRT antibody (ab24551) and β-hydroxybutyrate assay kit (ab83390).from abcam; anti-acetyl-Histone H4 antibody (06–866) from EMD Millipore. Polyclonal rabbit antibody against NCoR was as described 30. Other reagent information not shown here is described in the relevant methods and references.

Animal studies

All animal studies and procedures were approved by the institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Baylor College of Medicine. Male GFP-LC3Tg/+ mice were bred with either female PPARα−/− or FXR−/− mice to generate bigenic PPARα−/−; GFP-LC3Tg/+ or FXR−/−; GFP-LC3Tg/+. PPARα−/− and FXR−/− mice were pure C57BL/6 background. C57BL/6J were wild type controls. 8 to 10-week-old male wild-type C57BL/6J, PPARα−/−, FXR−/−, GFP-LC3Tg/+, PPARα−/−; GFP-LC3Tg/+, or FXR−/−; GFP-LC3Tg/+ mice were orally gavaged with either vehicle (DMSO in 4:1 of PEG-400 and Tween 80), GW7647 (5 mg/kg body weight) or GW4064 (100 mg/kg body weight) twice a day (first injection: 12:00 am, second injection: 12:00 pm). Mice were fed ad libitum or fasted for 24 h from 6:00 PM (day 1) to 6:00 PM (day 2) and then scarified to collect blood and livers. Harvested liver tissues were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen for molecular studies. Refed condition was 24 h fasted mice followed by feeding those mice with normal chow diets for another 24 h. To avoid circadian issues, all mice were scarified at 5 to 6:00 PM. GFP-LC3Tg/+ mice were generously given by N. Mizushima.

Primary hepatocyte culture

8 to 10-week-old male GFP-LC3Tg/+ mice were anesthetized with Avertin (Sigma Aldrich, # T48402, 240 mg/kg body weight) by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection. The liver perfusion were done by injecting butterfly needle into the portal vein and providing the following solutions sequentially: 50 mL of EBSS (ATLANTA biologicals, # B31350) supplemented with 10 mM HEPES (Invitrogen, # 24020–117) and 0.5 mM EGTA and then 50 mL of HBSS supplemented with 100 U/mL of Collagenase IV (Invitrogen, # 17101–015), and 0.05 mg/mL of Trypsin inhibitor (Invitrogen, # 17075–029). The perfused liver was carefully taken out, put onto a petri dish, added 25 mL of hepatocyte wash media (Invitrogen # 17704–024), and massaged with two cell scrapers until the liver has become apart with only connective tissue left behind. Dissociated cells were passed through funnel with mesh into 50 mL of falcon tube. After centrifugation at 600 rpm for 2 min, cell pellet was resuspended in hepatocyte wash media, which were carefully overlaid percoll solution (final 40%) pre-mixed with 150 mM of NaCl. After centrifugation at 600 rpm for 10 min, harvested cell pellet was washed twice with hepatocyte wash media, and then suspended in Williams’ E medium (Invitrogen, # 12551–032) supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, ITS, and glutaMAX (Invitrogen, #35050–061). All drug treatments or starvation experiments were performed 4–6 h after the initial plating on the culture dishes.

Cell culture and transfection

AML12 cells were maintained in the following media: (normal) DMEM/F12 high glucose (Invitrogen, # 11330–057) supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% ITS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin antibiotics, and 40 ng/mL dexamethasone; (starvation) HBSS media with Ca2+ and Mg2+ supplemented with 10 mM HEPES (Invitrogen, # 15630). mRFP-GFP-LC3 plasmids were transfected into AML12 cells grown on Lab-tek II Chamber Slide (Nunc, # 154461) with Lipofectamine 2000 according to the manufacturer’s protocol for 24 h followed by drug treatments for 24 h. Transfected cells were starved for 2 h, which was then washed three times with cold PBS, fixed with 3% PFA in PBS for 10 min at room temperature, and washed three times with PBS. Cells were counterstained with mounting solution containing DAPI. All drugs were dissolved in DMSO. Vehicle (Veh): complete media containing 0.1% DMSO. Starvation: HBSS media with 10 mM HEPES. Autophagic fluxes were quantified as follows: Autolysosomes (ALs) = RFP positive vesicles – GFP positive vesicles. Numbers of ALs induced by 2 h starvation + Veh were set as 100 %.

BODIPY and immunofluorescence assay in cells

AML12 cells were plated on two-chamber Lab-tek II dishes at 30% to 50% confluent cells per chamber. The following day, cells were treated with Veh (0.1% DMSO), or 10 µM Wy, or 1 µM GW4064 in complete medium with or without 125 µM Oleate for 24 h. Veh or GW4064-treated cells were starved for 2 h in HBSS medium prior to fixation of cells. Cells were washed twice with PBS followed by fixation with 3% PFA for 20 min at room temperature. After fixation, cells were washed four times with PBS followed by incubation with blocking buffer (1.5 g glycine, 3 g BSA, and 2 ml 0.5% (w/v) saponin in 100 ml PBS) for 45 min. Cells were incubated with rabbit anti-LC3b antibody (1:400 dilution in antibody diluent: 100 mg BSA, 2 ml 0.5% saponin in 100 ml PBS) for overnight at 4°C. Cells were washed four times (10 min each) with PBS followed by incubation with the secondary antibody (Alexa fluor 594 goat anti-rabbit IgG, 1: 200 dilution in antibody diluent) and BODIPY 493/503 (1 µg/ml concentration) for 1 h at room temperature. After that, cells were washed four times with PBS followed by DAPI staining with mounting solution. Cell images were obtained using a confocal microscope (NIKON A1Rsi dual scanner). Orange and yellow dots were defined as a lipophagic vacuole, which was quantified at least in 30 cells per condition using ImageJ software.

RNA purification and qPCR analysis

Total RNA was isolated from snap-frozen liver tissues using Trizol Reagent (Invitrogen #15596–026) and prepared for the cDNA using QuantiTect reverse transcription kit (Qiagen # 205311). Hepatic gene expression was determined by qPCR using FastStart SYBR Green master (ROX) (Roche # 04673484001). mRNA levels were normalized by the 36B4 gene. qPCR primer information for autophagy-related genes was listed in Table S1 and all other primers were purchased from Qiagen.

Immunoblot analysis

Cells cultured in 10 cm dishes were solubilized in 150 µL of RIPA buffer (25 mM Tris-HCL [pH 7.6], 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, and 1 mM EDTA) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors. 50 mg of liver tissues were homogenized in 1 mL RIPA buffer supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors, followed by brief sonication. Protein concentration was determined by using Pierce™ BCA Protein Assay Kit. 25 to 50 µg of total proteins were loaded on either 12% or 4–20% Mini-PROTEAN TGX™ Precast Gel (Bio-rad, Cat. # 456–1043 or # 456–1093), transferred onto Immuno-Blot PVDF membrane (Bio-rad, Cat. # 162–0177) and analyzed by immunoblot analysis using the ECL solution (Thermo Scientific, Cat. # 34086 or Millipore, Cat. # WBKLS0500).

Histology and immunofluorescence

Liver tissues were harvested and fixed in 4% PFA in PBS overnight at 4°C. The tissues were treated with 15% sucrose in PBS at 4°C for at least 4 hr and then with 30% sucrose in PBS at 4°C for overnight. Tissue samples were embedded in Tissue-Tek OCT (Sakura Finetek, # 4583) and stored at −70°C. The samples were sectioned at 5∼7 µm thickness, air-dried for 30 min, and stored at −20°C until use (Comparative Pathology Laboratory at Baylor College of Medicine). Images were taken on a confocal microscope (NIKON A1Rsi dual scanner). GFP-LC3 puncta were quantified in three independent visual fields from at least three independent mice using ImageJ software.

ChIP assays

ChIP from mouse livers was performed as described previously 31. For PPARα ChIP-seq and ChIP-qPCR (Extended Data Fig. 7), livers were harvested from fed WT or PPARα−/− mice treated with vehicle or GW7647 (5 mg/kg, twice a day, n=4 per group) after euthanasia. For PPARα, FXR, Pol II, p300, CRTC2 (TORC2), NCoR, SMRT, acetyl H4, and H3K27me3 ChIPs (Fig. 4c and Extended Data Fig. 7b, 9b, and 10a), fed or fasted WT mice were treated with vehicle, GW7647 (5 mg/kg), or GW4064 (100 mg/kg) twice a day (n=3 per group). 100 mg liver tissues were quickly minced using mortar and pestle with liquid N2 and cross-linked in 10 mL 1% Formaldehyde/1 × PBS for 15 min at room temperature (RT), followed by quenching with 1/20 volume of 2.5 M glycine solution for 5 min at RT. Minced liver tissues were washes twice with cold 1 × PBS (150 g, 5 min, 4°C). Nuclear extracts were prepared by Dounce homogenization (30 strokes on ice, tight fitting pestle-type B) in cell lysis buffer (5 mM PIPES, 85 mM KCl, 0.5% Igepal and complete protease inhibitor tablet from Roche, pH 8.0). Chromatin fragmentation was performed by sonication in 300 µL ChIP SDS lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES, 1% SDS, 10 mM EDTA, pH 7.5), using the Bioruptor (Diagenode, 4 × 5 min, 30 sec on/ 30 sec off). Proteins of interest were immunoprecipitated in ChIP dilution buffer (50 mM HEPES, 155 mM NaCl, 1.1% Triton X-100, 0.11% Na-deoxycholate, 1 mM PMSF and complete protease inhibitors tablet, pH 7.5) using 5 µL of each antibody. Cross-linking was reversed overnight at 65°C, and DNA was isolated using phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol. Precipitated DNA was analyzed by qPCR. Primer sequences used for ChIP-qPCR analysis were listed in Table S2.

PPARα ChIP-seq

For ChIP, frozen liver tissues were ground in liquid nitrogen and cross-linked in 1% Formaldehyde for 20 min, followed by quenching with 1/20 volume of 2.5 M glycine solution, and washes twice with 1xPBS. Cell lysis and chromatin fragmentation were performed by sonication in ChIP dilution buffer (50 mM HEPES, 155 mM NaCl, 1.1% Triton X-100, 1% SDS, 0.11% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mM EDTA, and complete protease inhibitors tablet, pH 7.5). PPARα proteins were immunoprecipitated using PPARα antibody, cross-linking was reversed overnight at 65°C, and DNA was isolated using phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol. Precipitated DNA was analyzed by qPCR. ChIP was performed independently on liver samples from fed WT or PPARα−/−mice treated with vehicle or GW7647 (5 mg/kg, twice a day), and the precipitated DNA or input DNA samples were pooled. 10 ng of the pooled DNA was then amplified according to ChIP Sequencing Sample Preparation Guide provided by Illumina, using adaptor oligo and primers from Illumina, enzymes from New England Biolabs and PCR Purification Kit and MinElute Kit from Qiagen. Deep sequencing was performed by the Functional Genomics Core (J.Schug and K. Kaestner) of the Penn Diabetes Endocrinology Research Center using the Illumina Genome Analyzer IIx, and sequences were obtained using the Solexa Analysis Pipeline.

ChIP-seq data analysis

Solexa sequencing reads were mapped to reference genome mm9 using Bowtie32. Peak calling was performed with MACS14 using default settings33. Peak heights were normalized to the total number of uniquely mapped reads and displayed in UCSC genome browser34 as the number of tags per 10 million tags. De novo motif analysis was performed with MEME35 using 200 bp regions centered at the summit of each peak. To analyze the enrichment of autophagy-related genes near PPARα binding sites, All genes containing a PPARα binding site (with or without PPARα motif DR1) within 20 kb from the TSS were compared with a list of autophagy-related genes36–43 (Table S1). P-values were calculated with hypergeometric test.

Transmission electron microscopy

Anesthetized mice were perfused with PBS for 3 min, followed immediately by perfusion with 2% PFA + 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M Millonig's phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). Liver tissue was quickly removed and minced in a large drop of cold fixative, then transferred to vials of cold fix and fixed over night in 4°C. After washing three times in 0.1 M Millonig's phosphate buffer, the tissue was post-fixed at room temperature in 0.1 M Millonig's phosphate buffer containing 1% OsO4 for 1 h. Post-fixation was followed by 3 rinses, 5 min each, of 0.1 M Millonig's phosphate buffer, after which all tissues were dehydrated through a gradient series of ethanol, beginning with two 10 min changes of 50% ethanol and ending with three 20 min changes of 100% ethanol from a freshly opened bottle. Liver tissue was en bloc stained with saturated uranyl acetate in 50% ethanol for 1 h during the 50% ethanol dehydration stage. After complete dehydration, the tissue was infiltrated over a period of 2 days with progressively concentrated mixtures of plastic resin and 100% ethanol. Infiltration continued until the tissue reached pure resin. The tissue was then given 3 changes of pure, freshly made Spurr's plastic resin (Spurr, A.R., (1969) J. Ultrastruct. Res. 26, 31–42) for 3 h each, after which the liver tissue was embedded in 00 BEEM capsules (Glauert, A. M., ed: Practical Methods in Electron Microscopy. Ro. 143–144. North-Holland American Elsevier, 1975.) and placed in a 68°C oven overnight. Thin sections of approximately 70 nm were obtained using an RMC MT6000-XL ultramicrotome (RMC. Inc, AZ, USA) and a Diatome Ultra45 diamond knife (DiATOME, USA), and collected on 150 hex-mesh copper grids. The sections were counter-stained with Reynold's lead citrate (J. Cell Biol. 17:208–12, 1963) for 4 min. Dry samples were examined on a Hitachi H7500 transmission electron microscope (Hitachi, Japan) and images were captured using a Gatan US1000 digital camera (Gatan, 1995) with Digital Micrograph (Gatan, v1.82.366) software.

Molecular cloning and Cell-based luciferase reporter assay

The oligonucleotides encompassing 3 copies of DR1 motifs found in mouse LC3a or LC3b enhancer region were annealed and treated with Klenow. Purified DNAs were cloned into pTK-Luc plasmid by a serial digesting with SacI and BglII. Successful cloning was confirmed by DNA sequencing analysis. Oligonucleotide sequences used for luciferase reporter assays were listed in Table S3. For the luciferase assay, AML12 cells were cultured in 24 well plates. Transient transfections were performed using Lipofectamine 2000. Cell were transfected with 200 ng of reporter constructs, 100 ng of CMX, CMX-mouse PPARα, or CMX-human FXR, and 50 ng of CMV-β-galactosidase. pCDNA3.1 was added to prepare the total DNA to 500 ng per well. After 4 h transfection, cells were treated with or Veh (0.1% DMSO), 10 µM Wy, or 1 µM GW4064 in media containing charcoal-stripped serum for 20 h before performing luciferase and β-galactosidase assay. Luciferase activity was normalized with β-galactosidase activity. Normalized values from vehicle-treated cells transfected with empty CMX plasmid were set as fold 1.

Measurement of β-hydroxybutyrate

AML12 cells were transfected with siControl (ON-TARGETplus Control pool, D-001810–10–20), siAtg5 (ON-TARGETplus SMARTpool siRNA Atg5, L-064838–00–0010), or siAtg7 (ON-TARGETplus SMARTpool siRNA Atg7, L-049953–00–0010) according to manufacturer’s instructions. siRNAs were purchased from Thermo Scientific Dharmacon. 24 h after transfection using Lipofectamine 2000, cells were treated with vehicle (0.1% DMSO) or Wy-14,643 (10 µM) in media containing charcoal-stripped serum and 250 µM oleate for 48 h. Released β-hydroxybutyrate in the medium was measured using β-hydroxybutyrate assay kit. Female Atg7F/F mice24 were bred with male Alb-Cre/+ mice to generate control littermates (Atg7F/F) and hepatocyte-specific Atg7 null (Alb-Cre/+; Atg7F/F) mice. 8-week-old male Atg7F/F and Alb-Cre/+; Atg7F/F mice were orally gavaged with either vehicle (DMSO in 4:1 of PEG-400 and Tween 80) or GW7647 (5 mg/kg body weight) twice a day (first injection: 12:00 am, second injection: 12:00 pm). Mice were fed ad libitum or fasted for 24 h from 6:00 PM (day 1) to 6:00 PM (day 2) and then scarified to collect blood and livers. Serum β-hydroxybutyrate concentrations were normalized with mouse liver weights.

Statistical analysis

Sample size for experiments was determined empirically based on preliminary experiments to ensure appropriate statistical power. Age, sex, and weight-matched mice were randomly assigned for the treatments. No animals were excluded from statistical analysis, and the investigators were not blinded in the studies. Values are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. and error bars (s.e.m.) for all results were derived from biological replicates rather than technical replicates. Significant differences between two groups were evaluated using a two-tailed, unpaired t-test, which was found to be appropriate since groups displayed a normal distribution and comparable variance. P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Extended Data

Extended Data Figure 1. PPARα or FXR agonist affects autophagic flux in murine hepatocytes.

a, Autophagic flux was assessed by LC3-Immunoblot analysis in AML12 cells treated with indicated dose of Wy or co-treated with Wy and bafilomycin A1 (BafA1). b and e, Biochemical determination of autophagy (p62/SQSTM1 immunoblot) in AML12 cells treated with indicated doses of Wy-14,643 (Wy) or GW4064 for 24 h. GW4064-treated cells were starved for 2 h. c, Primary hepatocytes prepared from GFP-LC3Tg/+ mice were treated with indicated doses of Torin1 or GW7647. GFP-LC3 cleavage was assessed by GFP-Immunoblot analysis. d, LC3-Immunoblot in AML12 cells treated with indicated doses of GW4064 or co-treated with GW4064 and Torin1. All drug treatments were done in complete media for 24 h otherwise indicated in each panel. β-actin is a loading control. f, Quantification of autophagic flux shown in Fig. 1a. Numbers of autolysosomes (ALs) induced by 2 h starvation + Veh were set as 100%. Numbers of autolysosomes = RFP positive vesicles – GFP positive vesicles. 30 cells were counted per condition (**P < 0.01 vs No starvation + Veh). Data represent mean±s.e.m. Statistics by two-tailed t-test.

Extended Data Figure 2. Nutrient availability regulates the expression of autophagy-related genes.

a and b, Biochemical determination of autophagy (LC3 immunoblot, LC3-I/II: non-lipidated and PE conjugated forms of MAP1LC3, respectively) or mTORC1 activity (p-S6S240/244 immunoblot) in AML12 cells treated with indicated time points of 100 µM of Wy-14,643 (Wy) or 10 µM of GW4064. GW4064-treated cells were starved in HBSS medium for 1 h. β-actin is a loading control. c, Bile acids suppress autophagosome formation. AML12 cells were treated with indicated doses of each bile acid for 24 h, followed by 1 h starvation in HBSS medium. d, Immunoblot analysis of LC3-I/II and β-actin in AML12 cells treated with indicated dose of GW7647 or GW4064 for 24 h. GW4064-treated cells were starved in HBSS medium for 1 h. e and f, Fed ad libitum, 24 h fasted, or 24 h refed after 24 h fasting WT mice were sacrificed to collect livers at 6:00 PM. e, Immunoblot analysis of LC3-I/II, β-actin, phospho-4E–BP1 (p-4E–BP1T37/46), and total 4E–BP1 (4E–BP1) in liver samples. 50 µg of proteins from liver homogenates were separated by SDS-PAGE and probed with the indicated antibodies. β-actin is a loading control. A pooled sample was loaded onto the gel in duplicates (n=5 per group). f, Hepatic expression levels of autophagy-related genes, PPARα target gene, and FXR target genes affected by nutrient availability. (n=5 per group, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs Fed WT mice). g, Hepatic expression levels of PPARα or FXR target gene (Acox1 and Cyp7a1, respectively) were determined by qPCR analysis. Fed or fasted WT mice were orally gavaged with vehicle (Veh), GW7647, or GW4064 twice a day. (n=5 per group, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs Fed WT mice). Panels in f and g, data represent mean±s.e.m. Statistics by two-tailed t-test.

Extended Data Figure 3. Pharmacologic activation of PPARα or FXR in fed or fasted mouse liver.

a and c, Hepatic expression levels of autophagy-related genes (LC3a, LC3b and Atg12), PPARα target gene (Acox1), and FXR target gene (SHP) were determined by qPCR analysis. Fed or fasted WT PPARα−/−, or FXR−/− mice were orally treated with Veh, GW7647, or GW4064 twice a day. (n=5 per group, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs Fed WT mice treated with Veh). b and d, Immunoblot analysis of LC3-I/II, β-actin, phospho-S6 (p-S6S240/244), and total S6 (S6) in liver samples. Fed or fasted WT mice were orally gavaged with Veh, GW7647, or GW4064 twice a day. A pooled sample was loaded onto the gel in duplicates. (n=5 per group). β-actin is a loading control. e, Representative confocal images (out of 9 tissue section per condition) of GFP-LC3 puncta (GFP color: autophagosomes) and DAPI (blue color: DNA) staining in livers. Fed or fasted bigenic PPARα−/−; GFP-LC3Tg/+, or FXR−/−; GFP-LC3Tg/+ mice were orally gavaged with Veh, GW7647, or GW4064 twice a day. Liver samples were fixed and cryosections were analyzed by confocal microscopy. Scale bar, 50 µm. f, Co-localization of BODIPY 493/503 (green) with LC3 (red) in AML12 cells treated with Veh or 1 µM of GW4064 for 24 h and simultaneously cultured with or without 125 µM oleate in complete medium. GW4064-treated cells were starved for 2 h. DNA was stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar, 20 µm. Quantification of Lipophagic vacuoles shown in Fig. 3b and Extended Data Fig. 3f. 30 cells were counted per condition (**P < 0.01). g, Measuring β-hydroxybutyrate. AML12 cells were transiently transfected with siControl, siAtg5, or siAtg7 for 24 h followed by indicated drug treatments for 48 h with or without 250 µM oleate (Veh: 0.1% DMSO, Wy; 10 µM Wy-14,643). Released β-hydroxybutyrate in the medium was determined. (**P < 0.01 vs siControl treated with Veh; #P < 0.01 vs siControl treated with Wy; ##P < 0.01 vs siControl treated with Oleate + Wy). h, Serum β-hydroxybutyrate were normalized with liver weights. Fed or 24 h fasted control littermates (Atg7F/F) and hepatocyte-specific Atg7F/F null (Alb-Cre/+; Atg7F/F) mice were treated with Veh or GW7647 twice a day. (n=4 per group, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs Fed Atg7F/F mice treated with Veh; #P < 0.01 vs Fasted Atg7F/F mice treated with Veh; ##P < 0.01 vs Fasted Atg7F/F mice treated with GW7647). Panels in a, c, g, f and h, data represent mean±s.e.m. Statistics by two-tailed t-test.

Extended Data Figure 4. PPARα activation or loss of FXR induces autophagy in liver.

Magnification of representative TEM images (our of 30 cells per group) of livers. a–c, Fed or fasted WT PPARα−/− or FXR−/− mice were orally gavaged with Veh, GW7647, or GW4064 twice a day. Lipophagy (yellow arrowhead), autophagosome (blue arrowhead), autolysosome (red arrowhead), microautophagy (black arrowhead), and multivesicular bodies (MVBs, purple arrowhead). Scale bar, 0.5 µm.

Extended Data Figure 5. Expression profiles of autophagy-related genes by PPARα or FXR activation in liver.

a–c, Hepatic expression levels of autophagy-related genes were determined by qPCR analysis in WT (a, b) or PPARα−/− or FXR−/− (c) mice. 11 genes shown in panel a were induced by PPARα activation, but not affected by FXR activation. 4 genes shown in panel b were suppressed by FXR activation, but not affected by PPARα activation. (panel a and b, n=5 per group, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs Fed WT mice treated with Veh; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 Fasted WT mice treated with Veh). Altered expression levels of 13 genes shown in Fig. 4a were lost in PPARα−/− or FXR−/− mice in panel c. (panel c, n=5 per group, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs Fed PPARα−/− or FXR−/− mice treated with Veh). Fed or fasted WT PPARα−/− or FXR−/− mice were orally gavaged with Veh, GW7647 or GW4064 twice a day. Panels in a–c, data represent mean±s.e.m. Statistics by two-tailed t-test.

Extended Data Figure 6. Cistromic analysis of PPARα and FXR in mouse liver.

a De novo motif analysis of PPARα bound genomic regions. Top PPARα peak regions (+/− 150 bp from peak summits, ranked by enrichment fold) were subjected to de novo motif discovery by MEME. The best motif discovered by MEME (top, E value=4.7e-227) highly resembles the PPARG::RXRA motif from JASPAR(bottom, ID: MA0065.2) as a direct repeat 1 motif (DR1). b, Venn diagram depicting increasing PPARα cistrome upon PPARα agonism in vivo. PPARα highly confident (HC) binding peaks: peaks of WT mice treated with Veh or GW7647 subtracted from peaks of PPARα−/− mice treated with Veh or GW7647, respectively. c, Venn diagram showing overlapping binding peaks between PPARα ChIP-seq and FXR ChIP-seq from WT mice treated with its synthetic agonist GW7647 or GW4064. d, Autophagy-related genes of PPARα and FXR cistrome. Within 20 kb from transcription start site (TSS), PPARα ChIP-seq showed that 7738 genes of total 28661 genes (mm9) have HC peaks in WT mice treated with GW7647 (FDR <0.0001, enrichment over PPARα−/− >10), and that 124 genes out of 230 autophagy-related genes (HADb: Human Autophagy Database, autophagy.lu/) have at least one PPARα peak. FXR ChIP-seq showed that 3835 genes have peaks in WT mice treated with GW4064, and 61 genes out of 231 autophagy-related genes have at least one FXR peak. e, PPARα ChIP-qPCR for known PPARα target genes. (n=4 per group, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs Fed WT mice treated with Veh). Data represent mean±s.e.m. Statistics by two-tailed t-test.

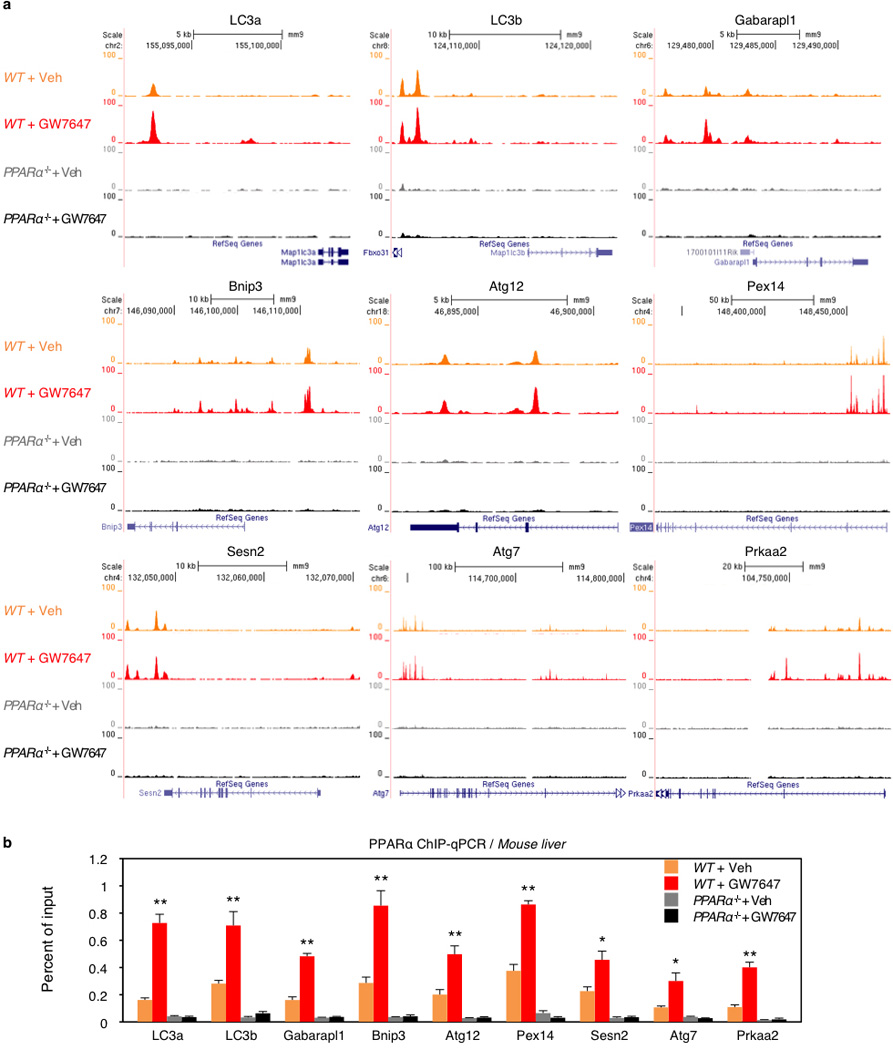

Extended Data Figure 7. PPARα ChIP-seq profiles at loci of autophagy-related genes.

Fed WT or PPARα−/− mice were orally gavaged with Veh or GW7647 twice a day. Mouse livers were taken out 6 h after the last injection of drugs to perform PPARα ChIP-seq and ChIP-qPCR. a, Representative ChIP-seq reads for PPARα aligned to the autophagy-related genes (LC3a, LC3b, Gabarapl1, Bnip3, Atg12, Pex14, Sesn2, Atg7, and Prkaa2). b, PPARα ChIP-qPCR for autophagy-related genes shown in panel a. (n=4 per group, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs Fed WT mice treated with Veh). Data represent mean±s.e.m. Statistics by two-tailed t-test.

Extended Data Figure 8. PPARα/FXR genomic competition for DR1 in Acox1 gene and autophagy-related genes.

a, Representative ChIP-seq reads for FXR and PPARα aligned to Acox1 and LC3b genes. The peaks in the box contain DR1 motif. Fed WT mice were orally gavaged with Veh or GW764 twice a day. (n=4 per group). b, PPARα or FXR ChIP-qPCR in livers. Fed or fasted WT mice were orally gavaged with Veh, GW7647, or GW4064 twice a day. (n=3 per group, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs Fed WT mice treated with Veh; ##P < 0.01 vs Fasted WT mice treated with Veh). c, Cell-based luciferase reporter assays. AML12 cells were transiently transfected with 3 × PPRE luciferase reporter construct (3 × PPRE-Luc) and CMX-β-gal in a combination of expression plasmids of PPARα, FXR or both, followed by drug treatment for 20 h (Veh, 0.1% DMSO; Wy, 10 µM Wy 14,643; GW4064, 1 µM GW4064). Normalized values (luciferase activity / β-galactosidase activity) of Veh-treated cells transfected with empty plasmid were set as fold 1. (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs Empty treated with Veh; ##P < 0.01). d, Functional role of DR1 motif in the regulatory region of mouse LC3a and LC3b for PPARα or FXR activity. Cell-based luciferase reporter assays were performed in AML12 cells by transiently transfecting 3 tandem copies of mouse LC3a/LC3b DR1 luciferase reporter construct (3 × LC3a/LC3b DR1 WT-Luc) or mutated version (3 × LC3a/LC3b DR1 mutant-Luc) and CMX-β-gal in a combination of expression plasmids of PPARα, FXR or both, followed by drug treatment for 20 h (Veh, 0.1% DMSO; Wy, 10 µM Wy-14,643; GW4064, 1 µM GW4064). Normalized values (luciferase activity / β-galactosidase activity) of Veh-treated cells transfected with empty plasmid were set as fold 1. (**P < 0.01 vs Empty treated with Veh; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01). e, Cell-based luciferase reporter assays were performed in AML12 cells by transiently transfecting siControl, siNCoR, siSMRT, or siSHP along with 3 tandem copies of mouse LC3b DR1 luciferase reporter construct (3 × LC3b DR1 WT-Luc), expression plasmids of PPARα and FXR, and CMX-β-gal followed by drug treatment for 24 h (Veh, 0.1% DMSO; Wy, 10 µM Wy 14,643; GW4064, 1 µM GW4064). Normalized values (luciferase activity / β-galactosidase activity) of Veh-treated cells transfected with siControl were set as fold 1. (**P < 0.01 vs siControl treated with Veh; ##P < 0.01). Panels in b-e, data represent mean±s.e.m. Statistics by two-tailed t-test.

Extended Data Figure 9. PPARα or FXR activation controls recruitments of coregulators and epigenetic marks in the enhancer regions of LC3a and LC3b genes.

Fed or fasted WT mice were orally gavaged with Veh, GW7647, or GW4064 twice a day. Hepatic ChIP-qPCR analysis with indicated antibodies (p300, NCoR1, SMRT, acetyl-H4, and H3K27me3) was used to determine recruitments of coregulators and subsequent alterations of epigenetic marks induced by PPARα/FXR genomic competition for DR1 found in the enhancer region of LC3a and LC3b genes. (n=3 per group, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs Fed WT mice treated with Veh; ##P < 0.01 vs Fasted WT mice treated with Veh). Data represent mean±s.e.m. Statistics by two-tailed t-test.

Extended Data Figure 10. Working model of the coordination of hepatic autophagy by nutrient sensing NRs, PPARα and FXR.

a, Fed or fasted WT mice were orally gavaged with Veh, GW7647, or GW4064 twice a day. Hepatic CRTC2 ChIP-qPCR in the promoter and enhancer region of LC3a gene. (n=3 per group, **P < 0.01 vs Fed WT mice treated with Veh; ##P < 0.01 vs Fasted WT mice treated with Veh). Data represent mean±s.e.m. Statistics by two-tailed t-test. b, Proposed model depicting transcriptionally activating or suppressive nutrient sensing NR, PPARα or FXR, respectively, which coordinates autophagy in liver. PPARα or FXR activation competes each other for binding to response elements found in autophagy-related genes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank N. Mizushima (Tokyo Medical and Dental University) for the gift of GFP-LC3Tg/+ mice; T. Yoshimori (Osaka University) for the gift of mRFP-GFP-LC3 plasmid; M. Komatsu (Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Medical Science) for the gift of Atg7F/F mice; D. Townley and M. Mancini (Integrated Microscopy Core, Baylor College of Medicine) for transmission electron microscopy and confocal microscopy; the members of the D.D.M. laboratory for comments and additional support. Core facilities supported by grants U54 HD-07495–39, P30 DX56338–05A2, P39 CA125123–04, S10RR027783–01A1; Next generation sequencing was performed by the Functional Genomics Core of the Penn Diabetes Research Center (DK19525). This work was supported by funding from the Alkek Foundation and the Robert R. P. Doherty Jr-Welch Chair in Science to D.D.M and R01 DK49780 and DK43806 to M.A.L.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information

10 Extended Data Figures, 5 Supplementary Tables and 1 Supplementary Figure.

Author Contributions

J.M.L. conceived the project, designed and performed most experiments, interpreted results, and co-wrote the manuscript. M.W. performed animal experiments and participated in discussion of the results. R.X. analyzed PPARα and FXR ChIP-seq data and designed primers for PPARα ChIP-qPCR. K.H.K. performed ChIP assays and molecular cloning. D.F. performed PPARα ChIP-seq. M.A.L. supervised experimental designs. D.D.M. conceived the project, supervised experimental designs, interpreted results, and co-wrote manuscript.

Author Information

PPARα ChIP-seq data sets have been deposited in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus with the accession number GSE61817.

Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary Table 1. Mouse qPCR primer sequences.

Supplementary Table 2. Mouse PPARα ChIP-qPCR primer sequences.

Supplementary Table 3. Mouse oligomer sequences for reporter constructs.

Supplementary Table 4. siRNA sequences.

Supplementary Table 5. Autophagy-related gene list.

Supplementary Figure 1. PPARα ChIP-seq profiles.

References

- 1.Mizushima N, Levine B, Cuervo AM, Klionsky DJ. Autophagy fights disease through cellular self-digestion. Nature. 2008;451:1069–1075. doi: 10.1038/nature06639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levine B, Kroemer G. Autophagy in the pathogenesis of disease. Cell. 2008;132:27–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rabinowitz JD, White E. Autophagy and metabolism. Science. 2010;330:1344–1348. doi: 10.1126/science.1193497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Evans RM, Barish GD, Wang YX. PPARs and the complex journey to obesity. Nat Med. 2004;10:355–361. doi: 10.1038/nm1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chawla A, Saez E, Evans RM. "Don't know much bile-ology". Cell. 2000;103:1–4. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00097-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nordlie RC, Foster JD, Lange AJ. Regulation of glucose production by the liver. Annu Rev Nutr. 1999;19:379–406. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.19.1.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laplante M, Sabatini DM. mTOR signaling in growth control and disease. Cell. 2012;149:274–293. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Inoki K, Kim J, Guan KL. AMPK and mTOR in cellular energy homeostasis and drug targets. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2012;52:381–400. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010611-134537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hardie DG, Ross FA, Hawley SA. AMPK: a nutrient and energy sensor that maintains energy homeostasis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:251–262. doi: 10.1038/nrm3311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Settembre C, Ballabio A, Lysosome: regulator of lipid degradation pathways. Trends Cell Biol. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2014.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gottlicher M, Widmark E, Li Q, Gustafsson JA. Fatty acids activate a chimera of the clofibric acid-activated receptor and the glucocorticoid receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:4653–4657. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.10.4653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keller H, et al. Fatty acids and retinoids control lipid metabolism through activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-retinoid × receptor heterodimers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:2160–2164. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.6.2160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ma K, Saha PK, Chan L, Moore DD. Farnesoid × receptor is essential for normal glucose homeostasis. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1102–1109. doi: 10.1172/JCI25604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kimura S, Noda T, Yoshimori T. Dissection of the autophagosome maturation process by a novel reporter protein, tandem fluorescent-tagged LC3. Autophagy. 2007;3:452–460. doi: 10.4161/auto.4451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mizushima N, Yoshimori T, Levine B. Methods in mammalian autophagy research. Cell. 2010;140:313–326. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klionsky DJ, et al. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy. Autophagy. 2012;8:445–544. doi: 10.4161/auto.19496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maloney PR, et al. Identification of a chemical tool for the orphan nuclear receptor FXR. J Med Chem. 2000;43:2971–2974. doi: 10.1021/jm0002127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown PJ, et al. Identification of a subtype selective human PPARalpha agonist through parallel-array synthesis. Bioorganic & medicinal chemistry letters. 2001;11:1225–1227. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(01)00188-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim J, Kundu M, Viollet B, Guan KL. AMPK and mTOR regulate autophagy through direct phosphorylation of Ulk1. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:132–141. doi: 10.1038/ncb2152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thoreen CC, et al. An ATP-competitive mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor reveals rapamycin-resistant functions of mTORC1. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:8023–8032. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M900301200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee SS, et al. Targeted disruption of the alpha isoform of the peroxisome proliferator- activated receptor gene in mice results in abolishment of the pleiotropic effects of peroxisome proliferators. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:3012–3022. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.6.3012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sinal CJ, et al. Targeted disruption of the nuclear receptor FXR/BAR impairs bile acid and lipid homeostasis. Cell. 2000;102:731–744. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00062-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mizushima N, Yamamoto A, Matsui M, Yoshimori T, Ohsumi Y. In vivo analysis of autophagy in response to nutrient starvation using transgenic mice expressing a fluorescent autophagosome marker. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:1101–1111. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-09-0704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Komatsu M, et al. Impairment of starvation-induced and constitutive autophagy in Atg7-deficient mice. The Journal of cell biology. 2005;169:425–434. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200412022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thomas AM, et al. Genome-wide tissue-specific farnesoid × receptor binding in mouse liver and intestine. Hepatology. 2010;51:1410–1419. doi: 10.1002/hep.23450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Claudel T, et al. Farnesoid × receptor agonists suppress hepatic apolipoprotein CIII expression. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:544–555. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00896-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chennamsetty I, et al. Farnesoid × receptor represses hepatic human APOA gene expression. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:3724–3734. doi: 10.1172/JCI45277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kerr TA, et al. Loss of Nuclear Receptor SHP Impairs but Does Not Eliminate Negative Feedback Regulation of Bile Acid Synthesis. Dev Cell. 2002;2:713–720. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00154-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang L, et al. Redundant pathways for negative feedback regulation of bile acid production. Dev Cell. 2002;2:721–731. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00187-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Methods References

- 30.Sun Z, et al. Deacetylase-independent function of HDAC3 in transcription and metabolism requires nuclear receptor corepressor. Mol Cell. 2013;52:769–782. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Feng D, et al. A circadian rhythm orchestrated by histone deacetylase 3 controls hepatic lipid metabolism. Science. 2011;331:1315–1319. doi: 10.1126/science.1198125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg SL. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang Y, et al. Model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS) Genome Biol. 2008;9:R137. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-9-r137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kent WJ, et al. The human genome browser at UCSC. Genome Res. 2002;12:996–1006. doi: 10.1101/gr.229102. Article published online before print in May 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bailey TL, et al. MEME SUITE: tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:W202–W208. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mizushima N, Yoshimori T, Ohsumi Y. The role of Atg proteins in autophagosome formation. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2011;27:107–132. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-092910-154005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kundu M, Thompson CB. Autophagy: basic principles and relevance to disease. Annu Rev Pathol. 2008;3:427–455. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathmechdis.2.010506.091842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jin M, Liu X, Klionsky DJ. SnapShot: Selective autophagy. Cell. 2013;152:368–368. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.01.004. e362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Settembre C, et al. TFEB links autophagy to lysosomal biogenesis. Science. 2011;332:1429–1433. doi: 10.1126/science.1204592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Warr MR, et al. FOXO3A directs a protective autophagy program in haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2013;494:323–327. doi: 10.1038/nature11895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shoji-Kawata S, et al. Identification of a candidate therapeutic autophagy-inducing peptide. Nature. 2013;494:201–206. doi: 10.1038/nature11866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Itakura E, Kishi-Itakura C, Mizushima N. The hairpin-type tail-anchored SNARE syntaxin 17 targets to autophagosomes for fusion with endosomes/lysosomes. Cell. 2012;151:1256–1269. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McKnight NC, et al. Genome-wide siRNA screen reveals amino acid starvation-induced autophagy requires SCOC and WAC. EMBO J. 2012;31:1931–1946. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.