Abstract

Background

The primary goal of this study was to examine the relationship between anxiety symptomatology and substance use (alcohol use and drug use) during adolescence, systematically by gender and race/ethnicity.

Methods

: Self-report surveys were administered to 905 15-17 year old adolescents (54% girls) in the spring of 2007.

Results

Results from multiple group analyses indicated that the relations between anxiety and substance use differs by gender and race/ethnicity. For Caucasian and African American boys, higher levels of social anxiety and separation anxiety were related to less substance use. In contrast, higher levels of generalized anxiety disorder and panic disorder were associated with more substance use for African American boys. The pattern was much less striking for girls. For Caucasian girls, higher levels of significant school avoidance were linked to more substance use and consistent with the results for boys, higher levels of separation anxiety were associated with less substance use. None of the anxiety disorders were related to substance use for African American girls or Hispanic girls or boys.

Conclusions

Findings from this study highlight the need to distinguish between different anxiety disorders. In addition, they underscore the importance of considering both gender and race/ethnicity when examining the relationship between anxiety and substance use during adolescence.

Keywords: anxiety, alcohol, drugs, gender, race

INTRODUCTION

During adolescence, numerous changes take place both within the individual (e.g., puberty, the development of advanced cognitive abilities) and in the individual's contexts (e.g., family, peers, school).1,2 In addition to these normative changes, non-normative changes (e.g., parental job loss, parental deployment) occur for many adolescents. Given all of the changes that occur in a relatively short period of time, it is not surprising that adolescence is a critical period for the development of internalizing problems, including anxiety disorders.

Many studies have shown that the prevalence of internalizing problems increases dramatically during adolescence.3-5 However, the majority of investigations have focused on depression. Relatively few studies have focused on anxiety, which is unfortunate because some research has indicated that anxiety is as common as depression during adolescence.6 Of note, prevalence rates for clinical anxiety disorders in children and adolescents range from 8.3% to 27%.7 Subclinical levels of anxiety are important to consider as well because many youth experience mild to moderate levels of anxiety, which may negatively affect their functioning.8

According to the negative affect regulation model,9,10 individuals who experience high levels of anxiety may use alcohol and/or drugs to lessen their symptoms. Indeed, some research has indicated that individuals with anxiety use alcohol as a way to cope with their anxious feelings.11,12 Consistent with the negative affect regulation model, research on adults has shown that anxiety disorders and substance use disorders tend to co-occur.13 Although comparatively less research has been conducted on adolescents, anxiety and substance use appear to similarly co-occur during adolescence.14 In one of the few studies examining anxiety and substance use in preadolescents and young adolescents, anxiety was found to predict substance use disorders later in adolescence.15 In another study examining adolescents, a strong association between anxiety and alcohol abuse was found.16 Similarly, in a study examining college students, youth who reported panic attacks were significantly more likely to use drugs (sedatives, cocaine, stimulants) in comparison to those who did not report panic attacks.12 Taken together, results from these studies are informative and indicate a relationship between anxiety and substance use.

It should be noted, however, that some of the studies just discussed did not consider gender differences and none of the studies examined racial/ethnic differences in the relationship between anxiety and substance use. The neglect to examine gender differences in the relationship between anxiety and substance use is unfortunate given that girls are more likely to experience internalizing symptomatology than are boys17-20 and boys are more likely to be heavier substances users in comparison to girls.21,22 Furthermore, there is some evidence that anxiety and substance use differ by race/ethnicity. For instance, Hispanic adolescents appear to be more likley to experience anxiety than Caucasian and African American adolescents.23,24 The limited research available also suggests that African American adolescents are less likely to use both alcohol and drugs than Caucasian and Hispanic adolescents.25-27 Given that gender and racial/ethnic differences have been observed for anxiety and substance use during adolecence, the association between anxiety and substance use also is likely to depend on gender and race/ethnicity.

Consistent with the broader literature, the studies just discussed were limited by their reliance on a specific anxiety disorder or overall indicator of general anxiety. The differential associations between separate anxiety disorders and substance use disorders were not examined. However, the relationship between anxiety and substance use may differ depending on the anxiety disorder assessed. During adolescence, substance use is normative.28 In addition, an adolescent's substance use is closely tied to the substance use of his/her peers.29,30 This point is key given that some of the anxiety disorders may influence the amount of time that is spent with peers. Youth with social anxiety, for instance, are likely to spend less time interacting with their peers because of their avoidant behavior, in comparison to youth with other anxiety disorders (e.g., generalized anxiety disorder).31,32 The avoidance of peer interaction, in turn, may decrease substance use involvement. The use of substances to self-medicate also may differ by anxiety disorder. According to the negative affect regulation model9,10, alcohol and drugs may be used to decrease negative affect, including high levels of anxiety. It may be that disorders that produce more acute levels of anxiety (e.g., panic disorder) are more likely to lead to self-medication with substances. Clearly, the use of overall anxiety symptomatology scores masks important differences that are likely to be found across the different anxiety disorders.

It also is important to note that prior research has found anxiety to be closely linked to depression during adolescence.33 Recent research suggests that anxiety and depression share common risk factors,34 but are unique and are not interchangeable.33,35 Because anxiety and depression share both common and unique variance,36,37 it is important for research examining adolescent anxiety to consider adolescent depression as well.

Given the limitations of the current literature, the goal of the present study was to more rigorously examine the relationship between anxiety and substance use during adolescence. Adolescent anxiety was examined at a finer level by assessing the specific anxiety disorders. Importantly, adolescent depression was taken into account so that the unique effect of anxiety on substance use could be assessed. In addition, both gender and racial/ethnic differences in the relationship between anxiety and substance use were examined. In sum, the present study was designed to examine whether the patterns of relations between the anxiety disorders and substance use differ by gender and/or race/ethnicity during adolescence.

METHODS

Participants

The sample included 905 10th and 11th grade students (54% girls) from the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. The adolescents were between 15 and 17 years of age, with a mean age of 16.10 (SD = .67). Sixty-three percent of the adolescents were Caucasian, 24% were African American, and 13% were Hispanic. Many of the minority youth lived in the inner city (85% of youth attending participating inner city schools were minority youth in the present study). In addition, eighty-nine percent of the adolescents lived with their biological mother and 61% lived with their biological father. The majority of mothers (96%) and fathers (95%) had graduated from high school.

Procedures

The study protocol was approved the the University of Delaware's Institutional Review Board. Seven public high schools in the Mid-Atlantic region (Delaware, Pennsylvania, and Maryland) participated. During the spring of 2007, 10th and 11th grade students from these schools who provided assent, and who had parental consent, were administered a self-report survey in school by trained research staff (all of whom were certified with human subjects training). Seventy-one percent of the adolescents attending the participating schools participated in the study. The survey took approximately 40 minutes to complete. After completing the survey, participants were compensated with a free movie pass.

Measures

Demographic variables

Participants were asked to report their gender, race/ethnicity, age, and their parents’ highest education level completed (1 = elementary school to 6 = graduate or medical school).

Anxiety

The 41-item Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders38 was used to assess adolescent anxiety. A sample item is “I am nervous.” The response scale ranges from 0 = not true or hardly ever true to 2 = very true or often true. The SCARED has good psychometric properties.39,40 Continuous scale scores were used in the present study indicating anxiety symptomatology. The Cronbach alpha coefficients for the SCARED scales in the present sample were as follows: Generalized anxiety disorder = .87, panic disorder = .88, separation anxiety disorder = .78, significant school avoidance = .60, and social anxiety disorder = .86.

Substance use

The adolescents were asked to report how much, on the average day, they usually drank (beer, wine, or liquor) in the last six months (separate questions were used for beer, wine, and liquor) using the following response scale 0 = none, 1 = 1 drink, 2 = 2 drinks, 3 = 3 drinks, 4 = 4 drinks, 5 = 5 drinks, 6 = 6 drinks, 7 = 7 drinks, 8 = 8 drinks, and 9 = more than 8 drinks. A drink was defined as a can/bottle of beer, a glass of wine, or a drink containing liquor (1 shot = 1 ounce). In addition, they were asked to report how often they usually had a drink (beer, wine, or liquor) in the last six months using the following response scale 0 = never, 1 = a few times, 2 = about once a month, 3 = 2-3 days a month, 4 = about once a week, 5 = 2-3 days a week, 6 = 4-5 days a week, and 7 = every day. Based on this information, a total alcohol quantity x frequency score was calculated. Because this score was positively skewed, the logarithmic transformation was used. Youth also were asked how many times they drank 6 or more drinks (cans/bottles of beer, glasses of wine, or drinks of liquor) on one occasion in the last 6 months. This variable was positively skewed. Therefore, it was linearly transformed as well.

In addition, the adolescents were asked how frequently they had used marijuana, sedatives, stimulants, inhalants, hallucinogens, cocaine or crack, and opiates (non-medical use only) in the last 6 months. The response scale ranged from 0 = no use to 7 = every day. A total drug use score was calculated by summing the scores of the seven different types of drugs. Because this score was positively skewed, the logarithmic transformation was used.

Overall, 39% of the adolescents reported consuming alcohol in the six months prior to data collection. Binge drinking was relatively high (6 or more drinks at one time) – 22% for liquor, 17% for beer, and 9% for wine. In addition, 17% of the adolescents reported using an illicit drug in the past six months. Marijuana was the most common illicit drug reported, with 16% of the youth reporting marijuana use in the six months prior to data collection.

Depression

The 20-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale for Children41 was used to measure adolescent depresssion. Depressive symptomatology was included as a covariate because research has shown that anxiety and depression during adolescence are closely related to one another.33 A representative CES-DC item is “I felt sad.” The response scale ranges from 1 = not at all to 4 = a lot. The CES-DC is a reliable and valid measure of depressive symptomatology.42 The Cronbach alpha coefficient for the CES-DC was .91 in our sample.

Statistical Analysis Plan

The present study was designed to explore whether patterns of relations between anxiety disorders and substance use differ by gender and/or race/ethnicity during adolescence. To address this question, as a first step, multiple group analysis models were conducted to examine whether the primary analyses should be run separately by gender and/or race/ethnicity. Multiple group analyses allow for a more rigorous examination of group differences in comparison to simply including the grouping variable (e.g., gender) as a covariate or separately conducting models by the grouping variable. The latter methods do not formally test whether differences in the grouping variable are statistically significant. In contrast, a multiple group analysis is able to test for the invariance of path coefficients, variances, and covariances across the grouping variable (e.g., gender). In line with the recommendations of Vandenberg and Lance43 for testing invariance across groups, an unconstrained model with freely estimated parameters was compared to models constraining path coefficients, intercepts, means, variances, covariances, and residuals to be equal across groups.

Structural equation modeling (SEM) was employed to examine whether anxiety symptomatology predicted substance use. Importantly, SEM may examine multiple relations simultaneously. In the present study, symptomatology scores for the anxiety disorders were specified as exogenous variables and the substance use variables were specified as endogenous variables. The age of the adolescent, parental education, and adolescent depressive symptoms were included as additional exogenous variables as covariates. In the present study, full information maximum likelihood (FIML)44 was used to handle missing data. FIML uses all of the available data (the covariance matrix and a vector of the means) to produce maximum likelihood-based sufficient statistics. Of note, FIML has been found to yield unbiased parameter estimates.44

RESULTS

Multiple Group Analyses

First, a baseline model pooling all data (including both genders and all racial/ethnic groups) was conducted. Consistent with the recommendations of Vandenberg and Lance for examining invariance across groups,43 this unconstrained baseline model (Model 1) was compared to a series of increasingly constrained models to test for invariance. In Model 2, the regression weights were constrained to be equal across groups. Model 3 additionally constrained the intercepts; Model 4 constrained the means; Model 5 constrained the covariances; and Model 6 constrained the residuals.

The baseline unconstrained model yielded a good fit to the data (χ2(34) = 38.56, p = .27; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA = .01). In contrast, the constrained models fit the data poorly. All of the constrained models for both gender and race/ethnicity were significant. In addition, results from the χ2 difference test comparing the constrained models to the unconstrained baseline model indicated that the constrained models provided a significantly worse fit to the data in comparison to the unconstrained baseline model in all instances (p values ranged from .00-.02). Therefore, the subsequent analyses were conducted separately by gender and race/ethnicity.

Structural Equation Modeling

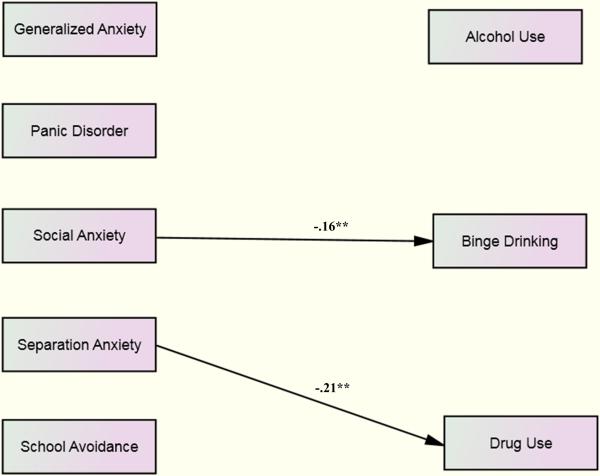

Caucasian boys

The model for Caucasian boys yielded a good fit to the data (χ2(32) = 38.03, p = .21; CMIN/DF = 1.19; CFI = .99; RMSEA = .03). For Caucasian boys, higher levels of social anxiety symptomatology predicted less binge drinking (β = −.16, p<.01). Similarly, higher levels of separation anxiety symptomatology predicted less drug use (β = −.21, p<.01). None of the other anxiety disorders predicted substance use for Caucasian boys (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Model for Caucasian Boys. Standardized regression coefficients are presented. For ease of interpretation, only significant paths are shown. Control variables, covariances, and disturbance terms are not displayed. *p<.05; **p<.01; ***p<.001.

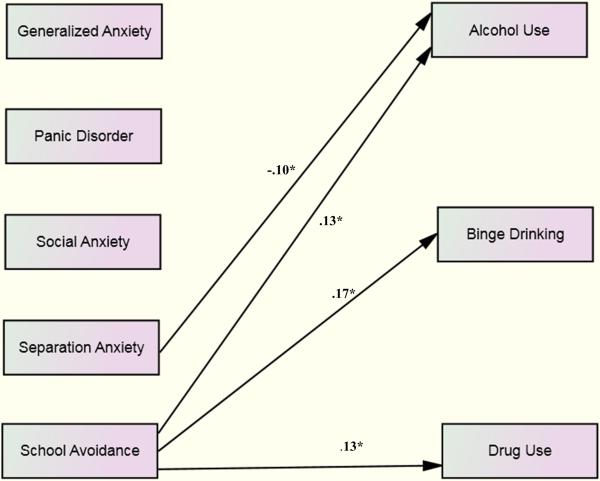

Caucasian girls

The model for Caucasian girls also fit the data well (χ2(29) = 32.11, p = .32; CMIN/DF = 1.11; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA = .02). For Causcasian girls, higher levels of school avoidance symtomatology predicted more alcohol use (β = .13, p<.05), more frequent binge drinking (β = .17, p<.05), and more drug use (β = .13, p<.05) (see Figure 2). In contrast, higher levels of separation anxiety symptomatology predicted less alcohol use (β = −.10, p<.05). Two of the control variables also were significant – older age (β = .11, p<.05) and depressive symptoms predicted more frequent drug use (β = .12, p<.05) for Caucasian girls (See FIGURE 2).

Figure 2.

Model for Caucasian Girls. Standardized regression coefficients are presented. For ease of interpretation, only significant paths are shown. Control variables, covariances, and disturbance terms are not displayed. *p<.05; **p<.01; ***p<.001.

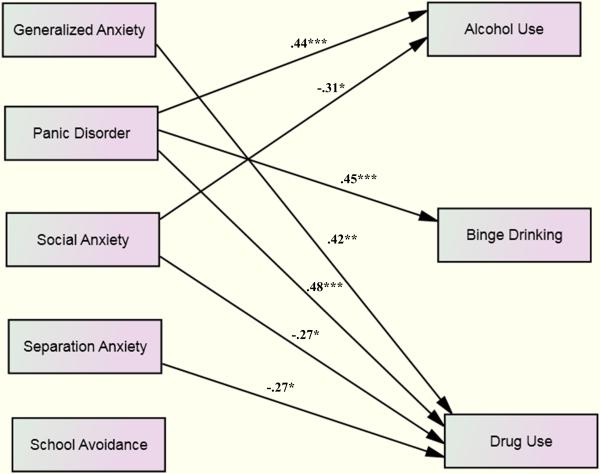

African American boys

The model for African American boys provided a good fit to the data (χ2(25) = 27.06, p = .35; CMIN/DF = 1.08; CFI = .99; RMSEA = .03). Consistent with the results for Caucasian boys, higher levels of separation anxiety symptomatology predicted less drug use (β = −.27, p<.05). Higher levels of social anxiety symptomatology also predicted less alcohol use (β = −.31, p<.05) and less drug use (β = −.27, p<.05). In contrast, higher levels of generalized anxiety symptomatology predicted more drug use (β = .42, p<.01). Similarly, higher levels of panic disorder symptomatology predicted more alcohol use (β = .44, p<.001), more frequent binge drinking (β = .45, p<.001), and more drug use (β = .48, p<.001) for African American boys (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Model for African American Boys. Standardized regression coefficients are presented. For ease of interpretation, only significant paths are shown. Control variables, covariances, and disturbance terms are not displayed. *p<.05; **p<.01; ***p<.001.

African American girls

The model for African American girls yielded a good fit to the data (χ2(35) = 25.74, p = .87; CMIN/DF = .74; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA = .00). However, in this model, none of the anxiety disorders predicted substance use.

Hispanic boys

The model for Hispanic boys provided an acceptable fit to the data (χ2(30) = 38.49, p = .14; CMIN/DF = 1.28; CFI = .93; RMSEA = .07). Similar to the results for African American girls, none of the other anxiety disorders predicted substance use for Hispanic boys.

Hispanic girls

The model for Hispanic girls also provided a good fit to the data (χ2(37) = 39.40, p = .36; CMIN/DF = 1.07; CFI = .99; RMSEA = .03). However, consistent with the results for African American girls and Hispanic boys, none of the anxiety disorders predicted substance use for Hispanic girls.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, results from multiple group analyses indicated that the relations between anxiety and substance use differ by gender and race/ethnicity. Furthermore, the SEM results yielded a different pattern depending on gender and race/ethnicity. For both Caucasian and African American boys, higher levels of social anxiety symptomatology predicted less alcohol use and higher levels of separation anxiety symtomatology predicted less drug use. In contrast, higher levels of generalized anxiety disorder symptomatology and panic disorder symptomatology predicted more frequent alcohol and drug use for African American boys. The pattern was much less striking for girls. For Caucasian girls, higher levels of significant school avoidance symptomatology predicted more frequent alcohol use, binge drinking, and drug use. Consistent with the boys’ results, higher levels of separation anxiety symptomatology also predicted less alcohol use. Of note, none of the anxiety disorders predicted alcohol or drug use for African American girls or Hispanic girls. The reasons why the anxiety disorders were more consistently related to substance use for boys than for girls are not clear. Given that girls tend to use alcohol and drugs less than boys during adolescence,45-46 perhaps there simply was less variation in the substance use variables, resulting in fewer significant findings. Alternatively, it may be that boys are more likely to use illicit substances to treat their anxiety symptoms, whereas girls are more likely to use licit substances (e.g., prescribed medication) to treat their anxiety symptoms. Indeed, among adults, women have been found to be more likely to seek treatment for anxiety problems in comparison to men.47 Future research should examine whether treatment seeking plays a role in the gender differences observed in this study.

In regard to race/ethnicity, anxiety was found to predict substance use for Caucasian and African American youth, but not for Hispanic youth. None of the anxiety disorders predicted substance use for Hispanic adolescents. It may be that the centrality of the family in the Hispanic culture, familism,48 protects youth from substance use involvement during adolescence. Importantly, in the Hispanic culture, familism is related to feelings of personal responsibility for the entire family, as well as for the self.49 It should be noted, however, that findings from this study are in contrast to prior studies that have examined younger Hispanic youth.23,24 Perhaps familism and the potential influence that it has on feelings of responsibility and subsequent substance use involvement become stronger as adolescents mature. Longitudinal research is needed to examine the role that familism may play in protecting Hispanic youth from developing problems such as substance abuse over time as adolescence progresses.

In the present study, the pattern of findings was most striking for African American boys. For African American boys, social anxiety predicted less alcohol and drug use. Separation anxiety predicted less drug use as well. These findings are not surprising given that youth with social anxiety and separation anxiety may spend relatively little time with their peers, which may protect them from substance use involvement. In contrast, generalized anxiety predicted more drug use, and panic disorder predicted more alcohol use, more frequent binge drinking, and more drug use. Acute anxiety (e.g., associated with panic disorder) was strongly related to greater alcohol and drug use for African American boys. Of note, many of the African American youth in this study resided in the inner city (85% of youth attending participating inner city schools were minority youth in the present study). These youth may have been more likely to experience acute anxiety given their greater exposure to poverty, crime (including drug-related crime), and gangs in the city. Moreover, these youth also may have had greater access to drugs in comparison to other youth in this study since drug trafficking has been shown to be heavier in cities than in the suburbs.50 Many African American boys in this study likely were exposed to the stressors that are inherent to living in the city, along with easy accessibility to drugs, likely increasing their risk for both anxiety and substance use. Therefore, it would be important for future research to replicate these findings in samples of youth where region and neighborhood were controlled via design.

An interesting pattern of relations also was observed for Caucasian girls. For this group, significant school avoidance symptomatology was related to more alcohol use, more frequent binge drinking, and more drug use. Depression was related to more drug use for this group as well. Perhaps one way in which Caucasian girls cope with school-related anxiety and depression is by using alcohol and drugs (e.g., self-medication). Prior reearch has found support for the self-medication hypothesis for adolescents.51 For example, negative affect has been shown to be associated with increased substance use over time during adolescence.51 It also should be noted that substance use may increase school-related anxiety and depression. Furthermore, poor academic performance may mediate this relationship. Additional research is needed to address the direction of effect and to examine potential mediating variables such as academic performance and peer relatationships.

Although this study extends the current literature by systematically examining gender and racial/ethnic differences in the relationship between anxiety and substance use in a large, diverse group of adolescents, a few caveats should be noted. The sample included youth who attended high school in the Mid-Atlantic region of the U.S. Therefore, caution should be taken in generalizing the findings to other youth. In addition, the data were collected via self-report surveys. Even though research has indicated that youth are accurate reporters of their own behaviors,52 including their substance use,53 it would be informative to corroborate the findings from this study with research using other types of methodology (e.g., parent reports). In addition, it should be noted that the present study did not use a calendar method such as the Time Line Follow Back to assess substance use. Nevertheless, the substance use measures used in this study were able to capture prior substance use because the adolescents were instructed to complete the alcohol and drug use measures in regard to the previous six months. As noted, the study also was cross-sectional. Therefore, the direction of the relationship between anxiety and substance use could not be addressed. An important next step will be to examine whether the direction of effect between anxiety and substance use differs by gender and/or race/ethnicity. It also would be important for future research to examine the realtionship between anxiety disorders and substances use consequences. Substance use consequences measures were not available because the larger project was designed to examine predictors of adolescent substance use. Despite the limitations, findings from this study clearly highlight the importance of considering both gender and race/ethnicity when examining the relationship between anxiety and substance use during adolescence. Moreover, results from this study underscore the need to distinquish between different types of anxiety and the manner in which they may differentially relate to adjustment during adolescence.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Appreciation is extended to the schools and students who participated in the study. Special thanks go to members of the AAP staff, especially Kelly Cheeseman, Lisa Fong, Alyson Cavanaugh, Sara Bergamo, Ashley Malooly, Ashley Ings, and Michelle Morse.

FUNDING

This research was supported by NIH grant number K01-AA015059. The authors report no conflicts of interest. In addition, the funding agency was not involved in the work reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Smetana JG, Campione-Barr N, Metzger A. Adolescent development in interpersonal and societal contexts. Annu Rev Psychol. 2006;57:255–284. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spear LP. The adolescent brain and age-related behavioral manifestations. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2000 Jun;24(4):417–463. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(00)00014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davey CG, Yücel M, Allen NB. The emergence of depression in adolescence: Development of the prefrontal cortex and the representation of reward. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2008;32(1):1–19. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Negriff S, Susman EJ. Pubertal Timing, Depression, and Externalizing Problems: A Framework, Review, and Examination of Gender Differences. J Res Adolesc. 2011;21(3):717–746. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steinberg L, Morris AS. Adolescent development. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:83–110. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kashani JH, Orvaschel H. A community study of anxiety in children and adolescents. Am J Psychiatry. 1990 Mar;147(3):313–318. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.3.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Costello E, Egger H, Angold A. Developmental epidemiology of anxiety disorders. In: Ollendick T, March J, editors. Phobic and Anxiety Disorders in Children and Adolescents: A Clinician's Guide to Effective Psychosocial and Pharmacological Interventions. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 2004. pp. 61–91. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ohannessian C, Lerner RM, Lerner JV, von Eye A. Does self-competence predict gender differences in adolescent depression and anxiety? J Adolesc. 1999 Jun;22(3):397–411. doi: 10.1006/jado.1999.0231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colder C, Chassin L, Villalta I, Lee M. Affect regulation and substance use: A developmental perspective. In: Kassel J, editor. Substance Use and Emotion. American Psychological Association; Washington, D.C.: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sher KJ. Children of Alcoholics: A Critical Appraisal of Theory and Research. The University of Chicago Press; Chicago, IL: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Comeau N, Stewart SH, Loba P. The relations of trait anxiety, anxiety sensitivity, and sensation seeking to adolescents’ motivations for alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use. Addict Behav. 2001 Nov-Dec;26(6):803–825. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00238-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deacon BJ, Valentiner DP. Substance use and non-clinical panic attacks in a young adult sample. J Subst Abuse. 2000;11(1):7–15. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(99)00017-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith JP, Book SW. Comorbidity of generalized anxiety disorder and alcohol use disorders among individuals seeking outpatient substance abuse treatment. Addict Behav. 2010 Jan;35(1):42–45. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deas-Nesmith D, Brady K, Campbell S. Comorbid Substance Use and Anxiety Disorders in Adolescents. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 1998;20(2):139–148. 1998/06/01. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Costello EJ, Mustillo S, Erkanli A, Keeler G, Angold A. Prevalence and development of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003 Aug;60(8):837–844. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Low NC, Lee SS, Johnson JG, Williams JB, Harris ES. The association between anxiety and alcohol versus cannabis abuse disorders among adolescents in primary care settings. Fam Pract. 2008 Oct;25(5):321–327. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmn049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crawford TN, Cohen P, Midlarsky E, Brook JS. Internalizing Symptoms in Adolescents: Gender Differences in Vulnerability to Parental Distress and Discord. J Res Adolesc. 2001;11(1):95–118. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diamantopoulou S, Verhulst FC, van der Ende J. Gender differences in the development and adult outcome of co-occurring depression and delinquency in adolescence. J Abnorm Psychol. 2011;120(3):644. doi: 10.1037/a0023669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Graber AG, Sontag LM. Internalizing Problems during Adolescence. Vol. 1. John Wiley & Sons Inc.; Hoboken, NJ: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hyde JS, Mezulis AH, Abramson LY. The ABCs of depression: integrating affective, biological, and cognitive models to explain the emergence of the gender difference in depression. Psychol Rev. 2008 Apr;115(2):291–313. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.115.2.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Popovici I, Homer JF, Fang H, French MT. Alcohol use and crime: findings from a longitudinal sample of U.S. adolescents and young adults. Alcohol Clin ExpRes. 2012 Mar;36(3):532–543. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01641.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trim RS, Meehan BT, King KM, Chassin L. The relation between adolescent substance use and young adult internalizing symptoms: findings from a high-risk longitudinal sample. Psychol Addict Behav. 2007 Mar;21(1):97–107. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McLaughlin KA, Hilt LM, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Racial/ethnic differences in internalizing and externalizing symptoms in adolescents. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2007 Oct;35(5):801–816. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9128-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Varela RE, Vernberg EM, Sanchez-Sosa JJ, Riveros A, Mitchell M, Mashunkashey J. Anxiety reporting and culturally associated interpretation biases and cognitive schemas: a comparison of Mexican, Mexican American, and European American families. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2004 Jun;33(2):237–247. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3302_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gil AG, Wagner EF, Tubman JG. Culturally sensitive substance abuse intervention for Hispanic and African American adolescents: empirical examples from the Alcohol Treatment Targeting Adolescents in Need (ATTAIN) Project. Addiction. 2004 Nov;99(Suppl 2):140–150. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patrick ME, Schulenberg JE. Alcohol use and heavy episodic drinking prevalence and predictors among national samples of American eighth- and tenth-grade students. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2010 Jan;71(1):41–45. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.White HR, Jarrett N, Valencia EY, Loeber R, Wei E. Stages and sequences of initiation and regular substance use in a longitudinal cohort of black and white male adolescents. J Studies Alcohol Drugs. 2007 Mar;68(2):173–181. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Marijuana use is rising; ecstasy use is beginning to rise; and alcohol use is declining among U.S. teens. University of Michigan News Service; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mercken L, Candel M, Willems P, de Vries H. Social influence and selection effects in the context of smoking behavior: changes during early and mid adolescence. Health Psychol. 2009 Jan;28(1):73–82. doi: 10.1037/a0012791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schinke SP, Fang L, Cole KC. Substance use among early adolescent girls: Risk and protective factors. J Adolesc Health. 2008 Aug;43(2):191–194. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen YP, Ehlers A, Clark DM, Mansell W. Patients with generalized social phobia direct their attention away from faces. Behav Res Ther. 2002;40:677–687. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(01)00086-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heuer K, Rinck M, Becker ES. Avoidance of emotional facial expressions in social anxiety: The Approach-Avoidance Task. Behav ResTher. 2007;45:2990–3001. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Janssens KA, Rosmalen JG, Ormel J, van Oort FV, Oldehinkel AJ. Anxiety and depression are risk factors rather than consequences of functional somatic symptoms in a general population of adolescents: the TRAILS study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2010 Mar;51(3):304–312. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lowe B, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Mussell M, Schellberg D, Kroenke K. Depression, anxiety and somatization in primary care: syndrome overlap and functional impairment. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008 May-Jun;30(3):191–199. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Henningsen P, Zimmermann T, Sattel H. Medically unexplained physical symptoms, anxiety, and depression: a meta-analytic review. Psychosom Med. 2003 Jul-Aug;65(4):528–533. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000075977.90337.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karevold E, Roysamb E, Ystrom E, Mathiesen KS. Predictors and pathways from infancy to symptoms of anxiety and depression in early adolescence. Dev Psychol. 2009 Jul;45(4):1051–1060. doi: 10.1037/a0016123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Laurent J, Ettelson R. An examination of the tripartite model of anxiety and depression and its application to youth. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2001 Sep;4(3):209–230. doi: 10.1023/a:1017547014504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Birmaher B, Khetarpal S, Cully M, Brent D, McKenzie S. Clinic WPIa. Pittsburgh: Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders (SCARED). p. PA1995. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Birmaher B, Khetarpal S, Cully M, Brent DA, McKenzie S. Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders (SCARED) – Parent form and child form (8 years and older). In: VandeCreek L, Jackson TL, editors. Innovations in Clinical Practice: Focus on Children & Adolescents. Professional Resource Press/Professional Resource Exchange; Sarasota, FL: 2003. pp. 99–104. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Muris P, Merckelbach H, Ollendick T, King N, Bogie N. Three traditional and three new childhood anxiety questionnaires: Their reliability and validity in a normal adolescent sample. Behav Res Ther. 2002 Jul;40(7):753–772. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(01)00056-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weissman M, Orvaschell H, Padian N. Children's Symptom and Social Functioning: Self-report Scales. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1980;(1678):736–740. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198012000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Garrison CZ, Addy CL, Jackson KL, McKeown RE, Waller JL. The CES-D as a screen for depression and other psychiatric disorders in adolescents. J AmAcad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1991 Jul;30(4):636–641. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199107000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vandenberg RJ, Lance CE. A Review and Synthesis of the Measurement Invariance Literature: Suggestions, Practices, and Recommendations for Organizational Research. Organ Res Methods. 2000 Jan;3(1):4–70. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wothke W. Longitudinal modeling with missing data. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; Mahwah, NJ: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Popovici I, Homer JF, Fang H, French MT. Alcohol use and crime: Findings from a longitudinal sample of U.S. adolescents and young adults. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2012;36(3):532–543. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01641.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barnes GM, Reifman AS, Farrell MP, Dintcheff BA. The effects of parenting on the development of adolescent alcohol misuse: A six-wave latent growth model. J Marriage Fam. 2000;62:175–186. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vesga-Lopez O, Schneier FR, Wang S, et al. Gender differences in generalized anxiety disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). J Clin Psychiatry. 2008 Oct;69(10):1606–1616. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Parra-Cardona JR, Bulock LA, Imig DR, Villarruel FA, Gold SJ. “Trabajando Duro Todos Los Días”: Learning From the Life Experiences of Mexican-Origin Migrant Families. FamRelat. 2006;55(3):361–375. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cauce A, Domench-Rodriguez M. Latino families: Myths and realities. In: Contreras J, Kerns K, Neal-Barnett A, editors. Latino Children and Families in the United States. Greenwood; Westport: 2002. pp. 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ensminger ME, Anthony JC, McCord J. The inner city and drug use: initial findings from an epidemiological study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1997 Dec;48(3):175–184. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)00124-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mason WA, Hitch JE, Spoth RL. Longitudinal relations among negative affect, substance use, and peer deviance during the tranistion from middle to late adolescence. Subst Use Misuse. 2009;44:1142–1159. doi: 10.1080/10826080802495211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Deković M, ten Have M, Vollebergh WAM, et al. The Cross-Cultural Equivalence of Parental Rearing Measure: EMBU-C. Eur J Psychol Assess. 2006 Jan;22(2):85–91. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Laforge RG, Borsari B, Baer JS. The utility of collateral informant assessment in college alcohol research: results from a longitudinal prevention trial. J Stud Alcohol. 2005 Jul;66(4):479–487. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]