Abstract

Purpose

Hypertension is a major risk factor for the development of cardiovascular disease, stroke and end-organ damage. There is a sex difference in blood pressure (BP) that begins in adolescence and continues into adulthood, where men have a higher prevalence of hypertension compared to women until the sixth decade of life. Less than 50% of hypertensive adults in the United States taking medication manage to control their BP to recommended levels using current therapeutic options, and women are more likely than men to have uncontrolled high BP. This is despite the fact that more women compared to men are aware that they have hypertension and women are more likely to seek treatment for the disease. Novel therapeutic targets need to be identified in both sexes to increase the percentage of hypertensive individuals with controlled BP. The purpose of this article is to review the available literature on the role of T cells in BP control in both sexes, and the potential therapeutic application/implications of targeting immune cells in hypertension.

Methods

A search of PUBMED was conducted to determine the impact of sex and gender on T cell-mediated control of BP. The search terms included sex, gender, estrogen, testosterone, inflammation, T cells, T regulatory cells, Th17 cells, hypertension and blood pressure. Additional data were included from our laboratory examining cytokine expression in the kidney of male and female SHR and differential genes expression in both the renal cortex and mesenteric arterial bed of male and female SHR.

Findings

There is a growing basic science literature regarding the role of T cells in the pathogenesis of hypertension and BP control, however, the majority of this literature has been performed exclusively in males despite the fact that both men and women develop hypertension. There is increasing evidence that while T cells also mediate BP in females, there are distinct differences in both the T cell profile and the functional impact of “male” vs. “female” T cells on cardiovascular health, although more work is needed to better define the relative impact of different T cell subtypes on BP in both sexes.

Implications

The challenge now is to fully understand the molecular mechanisms by which the immune system regulates BP and how the different components of the immune system interact so that specific mechanisms can be targeted therapeutically without compromising natural immune defenses.

Keywords: male, female, inflammation, Th17 cell, T regulatory cell

INTRODUCTION

Hypertension is defined as having a systolic blood pressure (BP) greater or equal to 140 mmHg or a diastolic BP greater or equal to 90 mmHg and BP control in hypertension remains a clinical challenge. Hypertension is the most common condition seen by primary care physicians and uncontrolled hypertension leads to chronic kidney disease, stroke, heart disease, aneurysm, peripheral artery disease and death. Currently, ~68 million American adults have hypertension1, yet only ~31 million of those individuals have adequate control of their hypertension. Estimated direct (health care) and indirect (worker productivity) costs of hypertension for 2010 were $46.4 billion annually and by 2030 costs are estimated to increase to $274 billion2 with the prevalence of hypertension expected to increase 8.4%.

New therapeutic options need to be identified for the treatment of hypertension in order to increase the percentage of individuals with controlled BP; however, our lack of knowledge regarding the mechanism(s) driving BP elevation in either sex makes this challenging. Hypertension is now considered a state of low-grade inflammation; it is established that hypertension is associated with the up-regulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines and the infiltration of immune cells into target organs3-6. It has been known since the 1960s that removal of the thymus or spleen, organs involved in lymphocyte development and maturation, prevents the development of hypertension in male experimental animal models and hypertension is associated with increases in circulating inflammatory cytokines clinically. While, these early studies broadly implicated the immune system in hypertension, they did not directly identify the immune component responsible. Advances in immunology research and technology have allowed for the identification, targeting and study of specific cells and components of the immune system in BP control. As a result, more recent studies have significantly expanded our understanding of the role of the immune system in BP regulation and suggest a direct contribution of lymphocytes, T cells in particular, to the progression and development of hypertension in male experimental animal models. While there is an expanding literature supporting a critical role for T cells in hypertension, the vast majority of these studies were conducted exclusively using male experimental animals. With nearly half of the hypertensive population being female, it is problematic that a majority of the basic science research in this field is conducted in male experimental models only. Moreover, the translational potential and clinical application of these basic science studies remain largely unknown. While there is clinical evidence supporting an increase in T cells in human hypertension, non-specific immunesuppressants are not justified for treatment in uncomplicated hypertension. However, targeting specific immune system components and T cell subtypes may hold the potential for widespread use to improve BP control rates in hypertensive men and women.

THERE ARE SEX AND GENDER DIFFERENCES IN HYPERTENSION

Hypertension is well-recognized as having distinct sex differences in the prevalence, absolute BP values, and molecular mechanisms contributing to the pathophysiology of the disease7-10.

It was first reported in 1947 that healthy, college-aged men have a significantly higher BP than age-matched healthy women11. These findings were confirmed by the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey conducted in the 1970s by the Centers for Disease Control which demonstrated that sex differences in BP began in adolescences between the ages of 12 and 1712; sex differences in BP were not detected in children ages 6 to 12. In addition, a recent study demonstrated that there is a sex difference in the BP threshold required to reduce the risk for cardiovascular disease in humans. The authors demonstrated that the BP threshold to reduce cardiovascular events is 135/85 mmHg in men, whereas in women BP needed to be at least 125/80 mmHg to achieve a similar improvement in cardiovascular outcomes as seen in men13. This finding suggests that women require a lower BP than men in order to reduce their risk for cardiovascular disease. Despite the fact that sex differences in BP have been recognized for over sixty years, current national guidelines recommend the same approach for treating men and women with hypertension and the definition of hypertension is the same regardless if you are a man or a woman. This approach does not seem to be appropriate since a recent cross-sectional survey of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data from 1999 to 2004reported that women with hypertension were more likely than men to be treated and take their medication, yet only 45% of treated women achieved BP control vs. 51% of treated men14. These statistics likely reflect that fact that women are still not included in clinical trials in numbers reflecting disease prevalence in the general population and pre-clinical studies remain focused on males.

There are several experimental models of hypertension that reflect the sex difference in BP observed in the human population, although the majority of studies examining sex differences in BP have used rodents. Rodents develop hypertension by induction (via vaso-constricting peptides or pharmacological drugs), genetic predisposition upon maturation, genetic predisposition to salt sensitivity, fetal programming, transgene insertion, or single gene knock-out9. Although it should be noted that even when there is not a sex difference in absolute BP values in experimental models of hypertension, males often have far greater end organ damage, suggesting that elevated BP in males has greater negative consequences on overall cardiovascular health than in females15. Rat models that mimic the sexual dimorphism in BP observed in the human population include the Wistar Kyoto (WKY) rats16, spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR)17, 18, WKY and SHR administered Nω-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME)19,20, mRen2. Lewis rat21, New Zealand hypertensive rat 22, rats and mice infused with angiotensin (Ang) II23, 24, deoxycorticosterone acetate (DOCA)-salt treated rats25, models of fetal programming and growth restriction26 (for full review on this topic9). SHR have been widely used to examine the molecular mechanisms driving sex differences in BP; male SHR have a 10-15 mmHg greater BP as measured by radiotelemetry than female SHR17. In addition, as a genetic model of essential hypertension, SHR were often used in the early studies implicating the immune system in hypertension27-31. For these reasons, studies by our group have begun to examine the impact of sex on the immune profile in hypertension using SHR.

LINKING INFLAMMATION AND HYPERTENSION

Low-grade inflammation is now a recognized hallmark of hypertension and there is an expanding literature regarding the role of inflammation and inflammatory cells in hypertension in experimental animals. As early as the 1960s experimental studies have suggested that the immune system plays a role in the development of hypertension. It was first introduced by White and Grollman that reducing the activation of the immune system by cortisone and 6-mercaptopurine attenuates increases in BP in male rats with partial renal infarction or the disruption of normal blood supply to part of the kidney32. Moreover, the transfer of lymph nodes from male hypertensive rats into normotensive rats caused the development of hypertension in the recipient rat33, while, a thymus transplant from a normotensive male WKY rat into a male SHR reduced BPin the SHR recipient27. Similarly, the transfer of spleen cells from hypertensive DOCA-salt rats into normotensive rats increased BP in recipient rats34 and anti-thymocyte serum decreases BP in SHR to normal levels28. These early studies implicated the adaptive immune system in BP control and hypertension since both the spleen and thymus are sites of lymphocyte activation and maturation, and laid the foundation for more mechanistic studies to come.

T CELLS AND HYPERTENSION

Over the past decade there have been an increasing number of studies confirming early work implicating the immune system in BP control and further defining the immune cells responsible. Suppression of lymphocytes using the immunosuppressant, mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) significantly reduces BP in male Dahl salt-sensitive rats35, 36, SHR37, salt-induced increases in BP in Sprague-Dawley rats infused with Ang II38 or N(ω)-nitro-L-arginine-methyl ester (L-NAME)39, all supporting the hypothesis that lymphocytes are a contributing factor to hypertension. However, MMF is a broad acting immunosuppressant and interferes with the generation of both B lymphocytes (B cells) and T lymphocytes (T cells). The main roles of B cells are to produce antibodies against an antigen and to serve as antigen presenting cells to process and present antigen to T cells to initiate T cell activation. T cells are a part of cell-mediated immunity, meaning they activate other cells or cytokines in order to elicit an immune response. Therefore, it remained unclear as to the relative contribution of B and T cell populations to BP control and the development of hypertension.

It was not until the elegant studies by Guzik et al. that T cells were directly implicated in hypertension. Rag-/- mice are deficient in both B and T cells and male Rag-/- mice have a blunted hypertensive response to AngII infusion and DOCA-salt40. Adoptive transfer of Pan CD3+T cells restored the hypertensive response to both of these agents in male Rag-/- mice; adoptive transfer of B cells did not alter the BP responses. Crowley et al. confirmed these findings using Scid mice41;male Scid mice have a blunted hypertensive response to chronic Ang II infusion. Scid mice are homozygous for the severe combined immune deficiency spontaneous mutation Prkdcscid and are characterized by an absence of functional B and T cells, lymphopenia, hypogammaglobulinemia, and a normal hematopoietic microenvironment. Additional support for a causal role for T cells in the development of hypertension comes from studies blocking T cell activation. Tcell activation requires both Tcell receptor ligation and co-stimulation, often mediated by an interaction between the B7 ligands, CD80 or CD86, on antigen-presenting cells with the Tcell co-receptor CD28. Either blocking B7-dependent co-stimulation of T cells pharmacologically or using mice lacking B7 ligands attenuates Ang II and DOCA-induced hypertension in male mice42. More recently, this finding was also supported in male Dahl salt-sensitive rats in which the Rag1 gene or CD247, a gene involved in T-cell signaling, were knocked out. In both cases, the mutant rats exhibited attenuations in salt-induced increases in BP and renal T cell infiltration43, 44. These groundbreaking studies directly demonstrated that T cells are required to develop and maintain a hypertensive response, and paved the way for numerous additional studies examining and defining the role of T cells in BP control and cardiovascular health.

T CELL LINEAGE

T cells are derived from hematopoietic stem cells in the bone marrow and they migrate to the thymus where they mature into a specific T cell lineage. Therefore, before further defining the role of T cells in BP control, it is important to understand the different T cell subtypes. The previously mentioned studies confirming a role for T cells in hypertension were performed using Pan CD3+ T cells, however, CD3+T cells can be defined and distinguished by the presence of membrane glycoproteins on their cell surface into two different subpopulations: CD4+ and CD8+ T cells- and both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells have been suggested to impact BP.

Naïve CD4+ T ‘helper’ cells coordinate immune responses by communicating with other cells and have the potential to differentiate into distinct effector subsets each with a specific function. These cells are crucial for the functioning of an intact immune system and play diverse roles in immune surveillance and protection against foreign pathogens. Depending on the local cytokine environment, CD4+ T cells will differentiate into one of the following: T helper 1 (Th1), T helper 2 (Th2), T helper 17 (Th17), follicular helper T (Tfh), or regulatory T cells (Treg; see the following reviews for more information45-48. Th1 cell differentiation is induced by interferon (INF)-γ and interleukin (IL)-2. Th1 cells produce INF-γ, IL-2, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-β to activate macrophages and are responsible for cell-mediated immunity and phagocyte-dependent protective responses for the clearance of intracellular pathogens. Th2 cells differentiate in the presence of IL-4 and produce IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13, which are responsible for stimulating antibody production, eosinophil activation, and inhibiting macrophages, thus providing phagocyte-independent protective responses. Th17 cells differentiate under the combined influence of IL-6 and low levels of transforming growth factor (TGF)-β or IL-23 and these cells release IL-17 and IL-2149. Th17 cells clear pathogens that were not adequately handled by Th1 or Th2 cells and have been implicated in the pathogenesis of several experimental models of autoimmune diseases50,51. Tfh cell formation is induced by IL-6 and IL-21 and these cells secrete IL-4 and IL-21 and they are essential in the activation and differentiation of B cells into immunoglobulin (Ig) secreting cells52. Finally, Treg differentiation is mediated by TGF-β and Tregs release the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10. Tregs play an important role in maintaining immune homeostasis by suppressing the function of other T cells to limit the immune response.

CD8+ T cells are cytotoxic cells and are important mediators of adaptive immunity against foreign pathogens53. Activated CD8+ T cells induce cytolysis of infected cells by: 1) granule exocytosis pathway, or 2) up-regulation of the fas ligand (FasL) to initiate programmed cell death by aggregation of Fas on target cells. CD8+ T cells also release cytokines and chemokines to recruit and/or activate additional effector cells including macrophages and neutrophils54. In addition, CD8+ Tregs have also been identified, although the role of CD8+ Tregs in BP control or cardiovascular health remains unexplored.

Both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells have been implicated in BP control and infiltration of these T cells into the brain, kidney, and vasculature, key organs critical in BP control, increases with increasing BP3-6, 55. AngII infusion significantly increases vascular and renal infiltration of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in male experimental animals5, 56. Male SHR have greater renal CD4+ T cell infiltration than age matched WKY and the ratio of CD4+/CD8+ in the kidney increases as male SHR age from 3 to 24 weeks of age and develop hypertension37, 57. Consistent with increases in BP correlating with increased immune cell infiltration, male Dahl salt-sensitive rats on a high-salt diet exhibit an increase in renal CD3+ T cells58. Furthermore, co-administration of the immune-suppressant tacrolimus during the high-salt treatment of male Dahl salt-sensitive rats attenuated increases in BP and renal CD3+ T cell infiltration. Similarly, transfer of chromosome 2 from the Brown Norway rat onto the Dahl salt-sensitive background lowers BP in Dahl salt-sensitive rats (SSBN2 rats) and the lower BP in the SSBN2 rats was associated with reduced aortic infiltration of total CD4+ T cells59. Moreover, attenuating increases in BP using BP-lowering agents olmesartan decreases renal infiltration of both T cell subtypes relative to vehicle control, supporting the hypothesis that it is elevated BP that is driving increased infiltration of either T cell subtype into the kidney60. While both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells have been implicated in BP control, the most is known regarding the role of Th17 cells and Tregs both in hypertension and related end-organ damage.

Th17 CELLS AND HYPERTENSION

Th17 are defined as CD4+ and expressing the orphan nuclear receptor, retinoid-related orphan receptor (ROR)-γ61, 62. Th17 cells mediate pro-inflammatory responses through the secretion of the pro-inflammatory cytokine, IL-1751, 63 and a role for Th17 cells in hypertension has been indirectly surmised based on studies manipulating IL-17 levels. DOCA-salt treatment of male Sprague-Dawley rats increases BP, renal and cardiac IL-17 and Th17 cells and treatment with anti-IL-17 neutralizing antibody significantly attenuated the increase in BP64. A role of Th17 cells in hypertension has been further suggested using IL-17 knockout mice. Male control (C57BL/6J mice) and IL-17-/- mice exhibit comparable initial increases in BPin response to Ang II, however, hypertension was not sustained in IL-17-/- mice65. Moreover, there was reduced vascular Tcell infiltration in IL-17-/- mice and vascular function was maintained65. These studies suggest that IL-17 is a critical factor in both the development and maintenance of hypertension and since Th17 cells are a primary source of IL-17, this cell type seemed a logical candidate in mediating this effect. In contrast to these findings, DOCA-salt treatment in conjunction with Ang II infusion resulted in comparable increases in BP in male control (C57BL/6J mice) and IL-17-/- mice despite a decrease in Th17 cells in the IL17-/- mice66. Interestingly, however, the authors also noted a significant increase in renal infiltration of γδT cells in the IL17-/- mice and an increase in indices of renal injury. As IL-23 is required for Th17 cell expansion, additional studies further examined the role of Th17 cells in mediating hypertension using male IL-23p19-/- mice and again, the BP response to DOCA-salt plus Ang II was comparable between control and knockout mice and knockout mice exhibited an increase inγδT cells64, 66. These data call into question the actual role of Th17 cells in mediating increases in BP. Indeed, a recent report found that Ang II-induced increases in cardiac IL-17A was derived primarily from infiltrating γδT cells, not CD4+ T cells, and deletion of γδT cell resulted in protection from Ang II-induced cardiac injury67. Consistent with this notion that Th17 cells are not critical in BP control, our group recently published that attenuating age-related increases in BP in SHR was not associated with significant changes renal Th17 cells68, however, we did not assessγδT cells. Therefore, γδT cells may be more critical in mediating increases in BP than Th17 cells, however, to date, there are not any studies in the literature that have employed adoptive transfer of isolated Th17 cells to conclusively link them to BP regulation. More work is needed to define the T cell subtype that is modulating increases in BP and the associated end-organ damage.

TREGS AND HYPERTENSION

CD4+CD25+Tregs express the intracellular transcription factor forkhead box P3 (foxP3) and secrete IL-10, a cytokine that inhibits the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines69. Tregs are crucial in maintaining immunologic self-tolerance and protection from auto-immune disease as well as regulating immune responses to pathogens by impacting effector T cell function. Both Tregs and IL-10 have been implicated in BP control.

In contrast to the available literature in Th17 cells, adoptive transfer studies have conclusively linked Tregs with decreases in BP and improved cardiovascular outcomes. The adoptive transfer of Tregs from the appropriate normotensive control male animals attenuates aldosterone and AngII-induced increases in BP and related end-organ damage70-72. Treg supplementation also attenuates increases in BP in male athymic nude mice on a mouse background predisposed to develop pulmonary hypertension73. Studies that have demonstrated a BP effect of Tregs have injected Tregs 3 times over a 2 week period. However, even a single injection of Tregs attenuates Ang II-induced cardiac damage in male NMRI mice (a colony of inbred mice generated at the US Naval Medical Research Institute) independent of changes in BP74, suggesting that more Tregs are needed to offer BP protection as compared to protecting against Ang II-induced tissue damage. In indirect support for a BP lowering role for Tregs, male Dahl salt-sensitive consomic rats with chromosome 2 from the Brown Norway rat have increased Tregs and IL-10 compared to control Dahl rats75. IL-10 has also been shown to offer protection against the development of hypertension in male mice. Infusion of Ang II results in greater increases in BP in male control (C57BL/6J) mice compared to IL-10-/-mice, and infusion of IL-10 for 2 weeks into control mice attenuates Ang II-Induced increases in BP76. Therefore, there is consistent reporting of a cardiovascular protective role for Tregs, raising the possibility that Tregs would be an attractive therapeutic target to improve BP control.

SEX DIFFERENCES IN INFLAMMATION IN HYPERTENSION

The review of the literature above builds a compelling case for a critical role for T cells in the regulation of BP. However, all of the studies mentioned above were performed exclusively in males. This calls into question the potential role of T cells in BP control in females. Women account for over half of the hypertensive population, yet the majority of basic science research continues to be performed in males, despite known sex and gender differences in cardiovascular disease, BP, the mechanisms mediating hypertension8, as well as in inflammatory-based diseases. Women are more likely than men to develop inflammatory and immunological disorders than men77, and there is growing awareness that certain autoimmune diseases are associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease78, 79. Women are more likely than men to develop systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and young women with SLE are ~10 times more likely to have hypertension than healthy young women80. Although we know very little about the immune system in essential hypertension in females, the immune system has been linked to that pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Preeclampsia is associated with an increase in Th17 cells as well as a decrease in Tregs, both experimentally and clinically81-83. Therefore there is data to suggest that BP in females is sensitive to inflammation, yet less has been done to directly compare responses in males and females to elucidate if there are differences in T cell differentiation, activation, and infiltration between that sexes that would result in sex and gender differences in the relative contribution of T cells to BP control.

To this end, our laboratory recently reported that similar to what is observed in male SHR, BP in female SHR is decreased by the immunosuppressant MMF84. Interestingly, under baseline conditions male SHR had more Th17 cells in their kidneys than females, while females had more Tregs. This finding is consistent with males having a higher BP compared to females. We have also shown that similar to what is observed in males, increases in BP are associated with increases in renal T cell infiltration in females. Female SHR have significantly more T cells in their kidneys than normotensive WKY and increasing BP in female SHR increases renal T cell counts68. Chronic nitric oxide synthase inhibition using L-NAME also increases BP in male and female SHR and this increase in BP was associated with increases in renal T cells in both sexes, however, female SHR exhibited greater increases in Th17 cells and greater decreases in Tregs than males20. Moreover, antihypertensive therapy significantly reduced L-NAME-induced increases in renal T cell infiltration supporting the hypothesis that renal T cell infiltration is BP dependent in both sexes, however, greater nitric oxide (NO) in females appears to contribute to the more anti-inflammatory immune profile in compared to males. To more directly link increases in BP to the T cell profile in SHR, additional studies by our group treated male and female SHR with the BP-lowering agents hydrochlorothiazide and reserpine from either 6-12 weeks of age to prevent age-related increases in BP, or 11-13 weeks of age to reverse established hypertension68. Neither treatment altered renal CD3+, CD4+, nor CD8+ T cells vs. same-sex vehicle controlsand neither attenuating increases in BP nor reversing established hypertension SHR significantly altered renal Th17 cells in either sex. However, both attenuating age-related increases in BP and reversing established hypertension decreased renal Tregs only in female SHR abolishing the sex difference in Tregs. These data suggest that Tregs, which as described above protect against hypertension in various experimental models, serve as an important feedback mechanism that may account for the consistently lower BP in female SHR relative to male SHR. Moreover, the lack of a change in Th17 cells in either sex despite changes in BP further calls into question to role of Th17 cells per se in BP control. Consistent with our findings, female C57Bl/6 mice display an increase in Tregs in adipose tissue in response to a high-fat diet not observed in males, and females are protected from high-fat diet-induced metabolic changes relative to males85.

Two recent studies have greatly expanded our understanding of the impact of sex on T cells and BP control using male and female Rag-/- mice. As has been previously demonstrated, adoptive transfer of CD3+T cells from wild-type male mice to male Rag-/- mice restores the hypertensive response to Ang II86, 87. However, adoptive transfer of T cells from males did not increase BP responses to Ang II in female Rag-/- mice87, and adoptive transfer of T cells from female mice into male Rag-/- mice abrogated Ang II-induced increase in BP86. Interestingly, male Rag-/- mice receiving T cells from a female donor exhibited more CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the perivascular adipose tissue than when the T cells were from a male donor, although sex of the donor did not impact renal T cell infiltration86. Therefore, despite having greater T cell infiltration into key BP-controlling organs if the T cells were of female origin, the hypertensive response was attenuated. These data suggest that not only are females able to limit the pro-hypertensive effects of T cells from males in response to AngII hypertension, but T cells from females have a less pro-inflammatory and pro-hypertensive phenotype than T cells from males. It should be noted that Tregs were not greater in female Rag-/- mice following adoptive transfer of male T cells or in male Rag-/- mice following adoptive transfer of female T cells. This finding potentially highlights the importance of the entire immune profile in dictating the physiological outcome of alterations in the immune system within each sex. Gaining better understanding of how females are able to limit the pro-hypertensive phenotype of T cells will be critical in targeting Tregs with the potential to improve BP control in both sexes.

POTENTIAL MECHANISMS DRIVING SEX DIFFERENCES IN T CELLS

SEX HORMONES

The two key parameters that drive the phenotypic differences between males and females are the sex chromosome complement (XY or XX) and levels of sex hormones (testosterone vs. estrogen). While there is a growing body of literature using novel animal models to dissociate the effects of hormones from chromosomes9, 88, the impact of sex chromosomes on T cells and the immune profile has yet to be examined. In contrast, there is a limited amount of data examining the impact of sex hormones on T cells and inflammation. Both estrogen and testosterone have been shown to impact T cells in vitro and in vivo. Castration of healthy men reduces circulating Tregs89 and testosterone supplementation to male experimental autoimmune orchitis rats increases Treg expression in the testis90. Similarly, estrogen stimulates Treg production in vitro and in vivo in CB57BL/6 mice and estrogen stimulated-conversion of CD4+ T cells into Tregs can be blocked by an estrogen receptor antagonist91.

Our group examined the impact of gonadectomy on the T cell profile of male and female SHR and although male sex hormones have primarily been associated with pro-hypertensive pathways in SHR17, 18 and female sex hormones are thought to be cardio-protective9, 10, 92, removal of sex hormones resulted in increases in Th17 cells and decreases in Tregs in both sexes. These data suggest that sex hormones in both sexes are anti-inflammatory and demonstrate that sex hormones cannot account for all of the observed sex differences in the renal T cell profile in SHR.

CYTOKINES

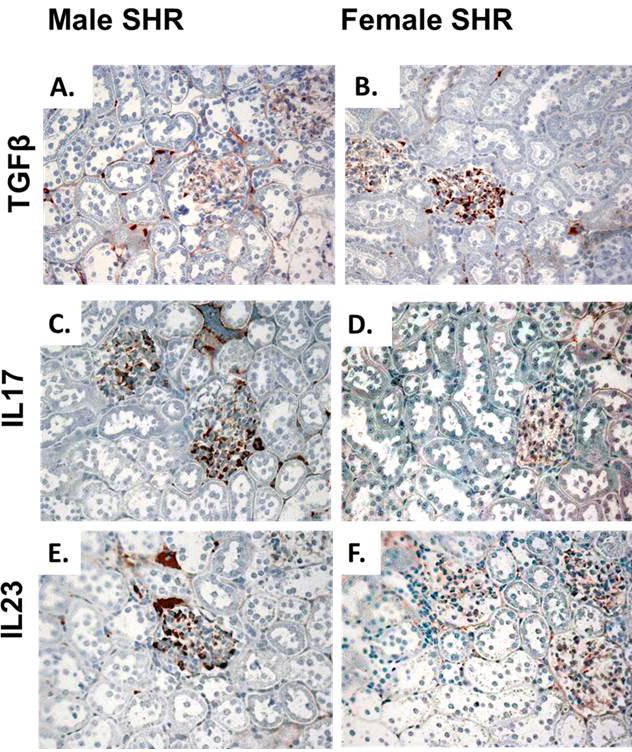

Another critical factor in determining the T cell profile is the local cytokine environment. Cytokines are critical determinants driving the differentiation of naïve T cells into the different subtypes. As noted above, naïve T cells differentiate into Th17 cells in the presence of low levels of TGF-β and high levels of IL-6 and IL-23. In contrast, high concentrations of TGF-β with low IL-6 levels drives Treg formation. Our group published that excretion of TGF-β and TNF-α are greater in female SHR compared to males93 and more recently that female SHR have more IL-10+ cells in their kidneys while males have more IL-6+ and IL-17+ renal cells68. These findings were confirmed using immunohistochemical analysis of key cytokines involved in T cell differentiation in male and female SHR: IL-17, IL-23, and TGF-β. Consistent with our previously published data, females have greater renalTGF-β expression while males have greater IL-17 and IL-23 staining (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Representative immunohistochemical analysis of key cytokines involved in T cell differentiation in the renal cortex of male and female SHR, brown staining indicates positive staining; n=5.

Our data support the hypothesis that there are sex differences in the renal cytokine profiles and these differences would be consistent with females having more Tregs and males having more Th17 cells. In agreement with our findings, adoptive transfer of T cells from a female donor to male Rag-/- mice resulted in more IL-10+ cells in peripheral blood mononuclear and plasma levels of IL-10 than when the T cells were from a male donor, suggesting that T cells from females have greater potential to induce IL-10 production86. Serum IL-10, TNF-α, and IL-6 levels have also been reported to be higher in female SHR compared to males94, and we have previously published that female DOCA-salt rats have greater plasma IL-10 levels than males25. Estrogen has also been demonstrated to increase the production of IL-10, while progesterone decreases IL-23 secretion in human monocyte-derived dendritic cells95.

Therefore, based on the central role played by the cytokine milieu in determining T cell differentiation and activation, sex differences in cytokines likely contribute to observed sex differences in the T cell profiles and will impact the overall physiological outcome of an inflammatory response. While this may address one question: what mediates the sex difference in the T cell profile, it raises a second question: what mediates the sex difference in the cytokine profile. Sex hormones may still be a likely candidate, however, gonadectomy of male and female SHR did not abolish the sex differences in IL-6, IL-10 or IL-17. These data suggest that other factors are mediating the sex differences in the cytokine profile of SHR. Consistent with our data, estrogen and testosterone have both been shown to induce systemic expression of IL-10 in humans and mice96, 97. Moreover, estrogen deficiency in female mice induces the expression of circulating Th17 cells and IL-1798, further suggesting a role for female sex hormones in IL-17 regulation.

Alternatively, T cells are not the only immune cells that release cytokines. For example, IL-10 is expressed by Th1 cells, Th2 cells, Th17 cells, Tregs, CD8+ T cells, B cells, dendritic cells, macrophages, mast cells, natural killer cells, eosinophils and neutrophils99. While there is little data available regarding the impact of sex on these factors, we performed a Rat Innate & Adaptive Immune Responses RT² Profiler PCR Array using the mesenteric arterial bed and the renal cortex of male and female SHR to examine the expression of 84 genes involved in mounting an immune response. There were numerous genes associated with innate, adaptive, and humoral immune responses that were differentially expressed in these tissues in SHR. In the renal cortex, 8 genes were more highly expressed in males while 25 genes had higher expression in female SHR (Table 1). Similarly, 9 genes exhibited greater expression in the mesenteric arterial bed of male SHR compared to females, while expression of 17 genes was greater in the female (Table 2). Interestingly, there was no overlap of genes that were more highly expressed in both the renal cortex and arteries of males compared to females, while female SHR exhibited greater CD1d1, CD40, Foxp3, janus kinase 2, and toll-like receptor 6 in both the renal cortex and the isolated mesenteric arterial bed when compared to males. In addition, there were 4 genes that were more highly expressed in the renal cortex of female SHR, but expression of the same genes were greater in the mesenteric arterial bed of males (chemokine receptor 8, interferon gamma, mannose-binding lectin 2, and myeloperoxidase). Our results further highlight the need to better understand the influence of sex on the immune system and underline the potential complexity of immune system regulation of BP and cardiovascular function. More work is needed to define the physiological impact of sex differences in immune system components, but also how each of these components may impact overall cardiovascular health.

Table 1.

Inflammatory genes differentially expressed in the renal cortex of male and female SHR.

| Genes more highly expressed in the renal cortex of male SHR vs. female SHR. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symbol | Description | Role | p-value | Fold Difference |

| Apcs | Amyloid P component, serum | Innate Immunity | 0.048 | 2.607 |

| Ccr5 | Chemokine receptor 5 | Adaptive Immunity: Th1 marker/response | 0.044 | 1.437 |

| Ddx58 | DEAD box polypeptide 58 | Innate Immunity: PPR | 0.012 | 1.385 |

| Ifna1 | Interferon-alpha 1 | Innate and Adaptive Immunity: Cytokine | 0.015 | 1.565 |

| Irak1 | Interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase 1 | Innate Immunity | 0.003 | 1.335 |

| Lyz2 | Lysozyme 2 | Innate Immunity; Response to Bacteria | 0.009 | 1.637 |

| Mapk14 | Mitogen activated protein kinase 14 | Innate Immunity | 0.055 | 1.172 |

| Tlr7 | Toll-like receptor 7 | Innate Immunity: PPR; Response to Virus | 0.007 | 1.671 |

| Genes more highly expressed in the renal cortex of female SHR vs. male SHR. | ||||

| Symbol | Description | Role | p-value | Fold Difference |

| Ccr6 | Chemokine receptor 6 | Adaptive Immunity: Th17 marker; Humoral Immunity | 0.018 | 1.327 |

| Ccr8 | Chemokine receptor 8 | Adaptive Immunity: Th2 and Treg marker | 0.057 | 1.350 |

| Cd1d1 | CD1d1 molecule | Adaptive Immunity: T cell activation marker | 0.004 | 3.126 |

| Cd40 | CD40 molecule | Innate, Adaptive Immunity; Response to Virus | 0.028 | 1.387 |

| Cd80 | CD80 molecule | Adaptive Immunity: Th1 marker/response, T cell activation | 0.026 | 1.496 |

| Cd86 | CD86 molecule | Adaptive Immunity: T cell activation; Response to Virus | 0.000 | 1.384 |

| Crp | C-reactive protein, pentraxin-related | Adaptive and Humoral Immunity | 0.057 | 1.350 |

| Csf2 | Colony stimulating factor 2 | Innate and Adaptive Immunity: Cytokine | 0.062 | 1.330 |

| Foxp3 | Forkhead box P3 | Adaptive Immunity: Treg marker | 0.015 | 1.432 |

| Icam1 | Intercellular adhesion molecule 1 | Adaptive Immunity: T cell activation | 0.030 | 1.229 |

| Ifnb1 | Interferon beta 1, fibroblast | Innate Immunity: Cytokine; Adaptive Immunity: Th2 marker; Humoral Immunity; Response to Bacteria/Virus | 0.057 | 1.350 |

| Ifng | Interferon gamma | Adaptive Immunity: Th1 marker, T cell activation, Cytokine; Humoral Immunity; Response to Bacteria | 0.045 | 1.365 |

| Il18 | Interleukin 18 | Innate and Adaptive Immunity: Cytokine, Th2 marker | 0.001 | 1.757 |

| Il1b | Interleukin 1 beta | Innate and Adaptive Immunity: Cytokine | 0.049 | 1.507 |

| Jak2 | Janus kinase 2 | Adaptive Immunity | 0.011 | 2.182 |

| Mapk1 | Mitogen activated protein kinase 1 | Innate Immunity | 0.077 | 1.085 |

| Mapk3 | Mitogen activated protein kinase 3 | Innate Immunity | 0.020 | 1.193 |

| Mbl2 | Mannose-binding lectin (protein C) 2 | Innate, Adaptive, and Humoral Immunity; Response to Bacteria | 0.057 | 1.350 |

| Mpo | Myeloperoxidase | Innate Immunity | 0.057 | 1.350 |

| Mx2 | Myxovirus (influenza virus) resistance 2 | Innate and Adaptive Immunity | 0.043 | 1.399 |

| Stat1 | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 | Innate and Adaptive Immunity | 0.042 | 1.161 |

| Stat3 | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 | Adaptive Immunity: Th17 marker | 0.001 | 1.262 |

| Tlr3 | Toll-like receptor 3 | Innate Immunity: PPR; Response to Bacteria/Virus | 0.002 | 1.462 |

| Tlr5 | Toll-like receptor 5 | Innate Immunity: PPR; Response to Virus | 0.003 | 1.427 |

| Tlr6 | Toll-like receptor 6 | Innate and Adaptive Immunity: PPR; Response to Bacteria | 0.019 | 1.207 |

Table 2.

Inflammatory genes differentially expressed in the mesenteric arterial bed of male and female SHR.

| Genes more highly expressed in the mesenteric arterial bed of male SHR vs female SHR. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symbol | Description | Role | p-value | Fold Difference |

| Ccl5 | Chemokine ligand 5 | Innate and Adaptive Immunity: Cytokine | 0.054 | 1.607 |

| Ccr8 | Chemokine receptor 8 | Adaptive Immunity: Th2 marker/response, Treg marker | 0.047 | 1.391 |

| Cd14 | CD14 molecule | Innate Immunity | 0.026 | 1.699 |

| Ifnb1 | Interferon beta 1, fibroblast | Innate Immunity: Cytokine; Adaptive Immunity: Th2 marker/response; Humoral Immunity; Response to Bacteria/Virus | 0.037 | 1.466 |

| Ifng | Interferon gamma | Adaptive Immunity: Th1 marker/response, T cell activation marker, Cytokine; Humoral Immunity; Response to Bacteria | 0.037 | 1.466 |

| Il13 | Interleukin 13 | Adaptive Immunity: Th2 marker/response, Cytokine | 0.037 | 1.466 |

| Mbl2 | Mannose-binding lectin (protein C) 2 | Innate, Adaptive, and Humoral Immunity; Response to Bacteria | 0.037 | 1.466 |

| Mpo | Myeloperoxidase | Innate Immunity | 0.009 | 2.182 |

| Rag1 | Recombination activating gene 1 | Adaptive Immunity | 0.036 | 1.504 |

| Genes more highly expressed in the mesenteric arterial bed of female SHR vs. male SHR. | ||||

| Symbol | Description | Role | p-value | Fold Difference |

| C3 | Complement component 3 | Innate and Humoral Immunity | 0.061 | 1.561 |

| Casp8 | Caspase 8 | Innate Immunity | 0.062 | 1.292 |

| Cd1d1 | CD1d1 molecule | Adaptive Immunity: T cell activation marker | 0.031 | 1.633 |

| Cd40 | CD40 molecule, TNF receptor superfamily member 5 | Innate and Adaptive Immunity; Response to Virus | 0.014 | 1.589 |

| Cxcl10 | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 10 | Innate and Adaptive Immunity: Cytokine; Response to Virus | 0.077 | 1.448 |

| Foxp3 | Forkhead box P3 | Adaptive Immunity: Treg marker | 0.066 | 1.437 |

| Ifnar1 | Interferon (alpha, beta and omega) receptor 1 | Adaptive Immunity; Response to Virus | 0.003 | 1.829 |

| Il23a | Interleukin 23, alpha subunit p19 | Adaptive Immunity: Th1 marker/response, T cell activation marker, Cytokine; Response to Bacteria/Virus | 0.012 | 1.421 |

| Itgam | Integrin, alpha M | Adaptive Immunity | 0.075 | 1.518 |

| Jak2 | Janus kinase 2 | Adaptive Immunity | 0.072 | 1.231 |

| Mapk8 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase 8 | Innate and Adaptive Immunity | 0.009 | 1.602 |

| Nfkb1 | Nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells 1 | Innate and Adaptive Immunity | 0.071 | 1.295 |

| Nod2 | Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain containing 2 | Innate Immunity: PRR; Adaptive Immunity: Th2 marker/response; Humoral Immunity; Response to Bacteria | 0.063 | 1.619 |

| Rorc | RAR-related orphan receptor C | Adaptive Immunity: Th17 marker | 0.057 | 2.619 |

| Stat6 | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 6 | Adaptive Immunity: Th2 marker/response | 0.053 | 1.311 |

| Tlr4 | Toll-like receptor 4 | Innate Immunity: PRR; Adaptive Immunity: Th1 marker/response; Response to Bacteria | 0.065 | 1.267 |

| Tlr6 | Toll-like receptor 6 | Innate Immunity: PRR; Adaptive Immunity: Th1 marker/response | 0.022 | 1.420 |

CLINICAL EVIDENCE SUPPORTING A T CELL COMPONENT TO BP CONTROL

There has been evidence for years that cytokine levels are increased in human hypertension, and gender differences have been reported. Serum IL-17 levels are greater in diabetic patients with hypertension compared with normotensive subjects65 and plasma levels of inflammatory cytokines (C-reactive protein, IL-6, and TNF-α) are positively correlated with BP in humans100. This finding was confirmed the CoLaus Study which assessed inflammatory biomarkers in a cross-sectional examination of men and women in Switzerland and reported that serum IL-6, TNF-α, and C-reactive protein levels were positively associated with BP in both sexes, however, the correlations between these cytokines and BP tended to be stronger in women101.

Lymphocytes have also been implicated in BP control in human hypertension. Administration of the immuno-suppressant MMF to 8 hypertensive patients (5 women and 3 men) with psoriasis or rheumatoid arthritis significantly reduced BP over a 3 month treatment102. Moreover, a month following the discontinuation of MMF, BP returned to pre-treatment levels. T cells have also been indirectly implicated in BP control in humans. HIV+ patients have reduced T cell counts and a lower incidence of hypertension than healthy individuals, and the risk of developing hypertension in HIV+ men and women is positively related to increases in T cells with treatment103, 104. Moreover, a single nucleotide polymorphism in CD247, a key protein in the T cell-receptor complex, is associated with BP in hypertensive individuals105.

In a small study of 13 patients with untreated, uncomplicated essential hypertension and age- and sex-matched normotensive controls, total numbers of circulating T cells and T cell subsets were similar in all groups however, the proliferative response of isolated T cells was less in the hypertensive individuals106. However, in a separate study, isolated T cells from newly diagnosed, untreated hypertensive patients (11 men and 9 women) exhibited greater T cell activity in response to stimulation than T cells from healthy volunteers, and treatment with losartan to lower BP was associated with a decrease in T cell activity to control levels; there were no differences in total T cell counts between hypertensive patients and healthy controls107. In contrast to these 2 studies, there are also reports of increases in total T cells in hypertension. Patients with hypertension exhibited greater numbers of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells compared to age- and sex-matched control subjects (35 out of 71 total patents were men)108 and Tregs are decreased in women with pregnancy-induced hypertension compared to normal pregnant women109. Additional support for a role for T cells in BP control in hypertension comes from studies where lowering BP control decreases T cells. In hypertensive patients (~50% men) with carotid atherosclerosis, lowering BP is associated with decreases in Th17 cells and increases in Tregs110.

While the majority of the studies above have included both men and women, the data have not been analyzed separately based on gender, preventing gender-based conclusion from being drawn. However, gender differences have been reported in T cells in human hypertension, making it imperative that this consideration be taken into account moving this field forward. Not only do healthy women have higher levels of circulating CD4+ T cells than men111, T cell function also appears to be different between healthy men and women. Isolated CD4+ T cells from women produce higher levels of IFN-γ and proliferate more than male CD4+ T cells from men, whereas CD4+ T cells from men had greater androgen-dependent IL-17 production112. However, the CD4+ T cell subtypes were not assessed in these studies and as noted above, if the sex differences are in Tregs and Th17 cells this would have the potential to result in gender-specific effects of T cell activation on the BP. While this is an excellent beginning, more clinical studies are needed to more fully define the T cell phenotype and function in both healthy and hypertensive men and women to determine the likelihood of targeting the immune cells in a gender-dependent manner to increase BP control rates.

POTENTIAL THERAPEUTIC APPLICATIONS OF TARGETING T CELLS IN HUMAN HYPERTENSION

The most consistent finding above is that Tregs offer protection against increases in BP and hypertension-induced end organ damage- making Tregs an attractive therapeutic target to improve BP control rates. But are Tregs a logical or likely target? Potentially, the answer to this question is yes, although clinical studies in hypertension are needed to support this conclusion. Intravenous immunoglobulin therapy (IVIG) is often used in the treatment of immune-mediated diseases and it was recently shown that IVIG acts, in part, by driving the expansion of Tregs in children with Kawasaki disease113. Autologous Tregs are currently being used clinically to treat graft-vs-host disease, transplant rejection, autoimmune disease, and are in clinical trials to treat type 1 diabetes. Therefore, while non-specific immunosuppressants are not justified in uncomplicated hypertension, targeting specific T cell subtypes, particularly Tregs, may hold the potential for widespread use to improve BP control rates in hypertensive men and women.

SUMMARY

There is an ever expanding literature base supporting a causal role of T cells to hypertension and related end-organ damage in both the basic sciences and clinically. The challenge now is to fully understand the molecular mechanisms by which the immune system regulates BP and how the different components of the immune system interact so that specific mechanisms can be targeted therapeutically without compromising natural immune defenses. While men and women both become hypertensive there is growing evidence to suggest that many of the molecular pathways by which they become hypertensive differ, and there is mounting evidence to suggest that the same will be the case for T cells. It remains critically important for the scientific community to acknowledge and understand the implications of sex differences in BP control as we generate novel experimental animal models to identify new targets in hypertension. Valuable information can be gained by studying both sexes and critical differences between groups may be obscured by combining the sexes into a single group. Sex and gender differences in BP control and cardiovascular disease have been known for over 60 years, and recent experimental studies in Rag-/- mice highlight the critical role of lymphocytes in mediating sex differences in basal BP control. Therefore, based on the potential therapeutic application of Tregs, better understanding of how females are able to maintain higher numbers of Tregs will greatly aid in our ability to expand these T cells in vivo to improve cardiovascular outcomes for all hypertensive patients.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by HL093271 to JC Sullivan and a predoctoral fellowship from the American Heart Association Greater Southeast Affiliate to AJ Tipton.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest Statement:

Neither AJT nor JCS have any conflicts to disclose.

References

- 1.Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Blaha MJ, Dai S, Ford ES, Fox CS, Franco S, Fullerton HJ, Gillespie C, Hailpern SM, Heit JA, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Judd SE, Kissela BM, Kittner SJ, Lackland DT, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Mackey RH, Magid DJ, Marcus GM, Marelli A, Matchar DB, McGuire DK, Mohler ER, 3rd, Moy CS, Mussolino ME, Neumar RW, Nichol G, Pandey DK, Paynter NP, Reeves MJ, Sorlie PD, Stein J, Towfighi A, Turan TN, Virani SS, Wong ND, Woo D, Turner MB American Heart Association Statistics C, Stroke Statistics S. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2014 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;129:e28–e292. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000441139.02102.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heidenreich PA, Trogdon JG, Khavjou OA, Butler J, Dracup K, Ezekowitz MD, Finkelstein EA, Hong Y, Johnston SC, Khera A, Lloyd-Jones DM, Nelson SA, Nichol G, Orenstein D, Wilson PW, Woo YJ. Forecasting the future of cardiovascular disease in the United States: A policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123:933–944. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31820a55f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trott DW, Harrison DG. The immune system in hypertension. Adv Physiol Educ. 2014;38:20–24. doi: 10.1152/advan.00063.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harrison DG, Guzik TJ, Lob HE, Madhur MS, Marvar PJ, Thabet SR, Vinh A, Weyand CM. Inflammation, immunity, and hypertension. Hypertension. 2011;57:132–140. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.163576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harrison DG, Vinh A, Lob H, Madhur MS. Role of the adaptive immune system in hypertension. Current Opinion Pharmacol. 2010;10:203–207. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schiffrin EL. The immune system: Role in hypertension. Can J Cardiol. 2013;29:543–548. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2012.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller VM, Reckelhoff JF, Sieck GC. Physiology’s impact: Stop ignoring the obvious-sex matters! Physiology. 2014;29:4–5. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00064.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zimmerman MA, Sullivan JC. Hypertension: What’s sex got to do with it? Physiology. 2013;28:234–244. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00013.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sandberg K, Ji H. Sex differences in primary hypertension. Biology of Sex Differences. 2012;3:7. doi: 10.1186/2042-6410-3-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maranon R, Reckelhoff JF. Sex and gender differences in control of blood pressure. Clin Sci. 2013;125:311–318. doi: 10.1042/CS20130140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boynton RE, Todd RL. Blood pressure readings of 75,258 university students. Archives Internal Med. 1947;80:454–462. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1947.00220160033003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roberts J, Maurer K. Blood pressure levels of persons 6-74 years. United States, 1971-1974. Vital and health statistics. Series 11, Data from the National Health Survey. 1977:i–v. 1–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hermida RC, Ayala DE, Mojon A, Fontao MJ, Chayan L, Fernandez JR. Differences between men and women in ambulatory blood pressure thresholds for diagnosis of hypertension based on cardiovascular outcomes. Chronobiology International. 2013;30:221–232. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2012.701487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gu Q, Burt VL, Paulose-Ram R, Dillon CF. Gender differences in hypertension treatment, drug utilization patterns, and blood pressure control among us adults with hypertension: Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999-2004. Am J Hypertens. 2008;21:789–798. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2008.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ji H, Pesce C, Zheng W, Kim J, Zhang Y, Menini S, Haywood JR, Sandberg K. Sex differences in renal injury and nitric oxide production in renal wrap hypertension. Am J Physiol-Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H43–47. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00630.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bhatia K, Zimmerman MA, Sullivan JC. Sex differences in angiotensin-converting enzyme modulation of Ang (1-7) levels in normotensive WKY rats. Am J Hypertens. 2013;26:591–598. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hps088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sullivan JC, Semprun-Prieto L, Boesen EI, Pollock DM, Pollock JS. Sex and sex hormones influence the development of albuminuria and renal macrophage infiltration in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;293:R1573–1579. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00429.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reckelhoff JF, Zhang H, Srivastava K. Gender differences in development of hypertension in spontaneously hypertensive rats: Role of the renin-angiotensin system. Hypertension. 2000;35:480–483. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.35.1.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sainz J, Osuna A, Wangensteen R, de Dios Luna J, Rodriguez-Gomez I, Duarte J, Moreno JM, Vargas F. Role of sex, gonadectomy and sex hormones in the development of nitric oxide inhibition-induced hypertension. Experimental Physiol. 2004;89:155–162. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2003.002652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brinson KN, Elmarakby AA, Tipton AJ, Crislip GR, Yamamoto T, Baban B, Sullivan JC. Female SHR have greater blood pressure sensitivity and renal T cell infiltration following chronic NOS inhibition than males. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2013;305:R701–R710. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00226.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pendergrass KD, Pirro NT, Westwood BM, Ferrario CM, Brosnihan KB, Chappell MC. Sex differences in circulating and renal angiotensins of hypertensive mren(2). Lewis but not normotensive lewis rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295:H10–20. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01277.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ashton N, Balment RJ. Sexual dimorphism in renal function and hormonal status of New Zealand genetically hypertensive rats. Acta Endocrinologica. 1991;124:91–97. doi: 10.1530/acta.0.1240091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sullivan JC. Sex and the renin-angiotensin system: Inequality between the sexes in response to RAS stimulation and inhibition. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;294:R1220–1226. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00864.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sullivan JC, Bhatia K, Yamamoto T, Elmarakby AA. Angiotensin (1-7) receptor antagonism equalizes angiotensin II-induced hypertension in male and female spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 2010;56:658–666. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.153668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giachini FR, Sullivan JC, Lima VV, Carneiro FS, Fortes ZB, Pollock DM, Carvalho MH, Webb RC, Tostes RC. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 activation, via downregulation of mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase 1, mediates sex differences in desoxycorticosterone acetate-salt hypertension vascular reactivity. Hypertension. 2010;55:172–179. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.140459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grigore D, Ojeda NB, Alexander BT. Sex differences in the fetal programming of hypertension. Gend Med. 2008;5(Suppl A):S121–132. doi: 10.1016/j.genm.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ba D, Takeichi N, Kodama T, Kobayashi H. Restoration of T cell depression and suppression of blood pressure in spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR) by thymus grafts or thymus extracts. J Immunol. 1982;128:1211–1216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bendich A, Belisle EH, Strausser HR. Immune system modulation and its effect on the blood pressure of the spontaneously hypertensive male and female rat. Biochemical Biophysical Research Communications. 1981;99:600–607. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(81)91787-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takeichi N, Ba D, Koga Y, Kobayashi H. Immunologic suppression of carcinogenesis in spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR) with T cell depression. J Immunol. 1983;130:501–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takeichi N, Suzuki K, Okayasu T, Kobayashi H. Immunological depression in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Clinical Experimental Immunol. 1980;40:120–126. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dzielak DJ. Immune mechanisms in experimental and essential hypertension. Am J Physiol. 1991;260:R459–467. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1991.260.3.R459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.White FN, Grollman A. Autoimmune factors associated with infarction of the kidney. Nephron. 1964;1:93–102. doi: 10.1159/000179322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Okuda T, Grollman A. Passive transfer of autoimmune induced hypertension in the rat by lymph node cells. Texas Reports Biol Med. 1967;25:257–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Olsen F. Transfer of arterial hypertension by splenic cells from DOCA-salt hypertensive and renal hypertensive rats to normotensive recipients. Acta Pathologica Microbiologica Scandinavica Section C, Immunology. 1980;88:1–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1980.tb00065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.De Miguel C, Das S, Lund H, Mattson DL. T lymphocytes mediate hypertension and kidney damage in Dahl salt-sensitive rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2010;298:R1136–1142. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00298.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mattson DL, James L, Berdan EA, Meister CJ. Immune suppression attenuates hypertension and renal disease in the Dahl salt-sensitive rat. Hypertension. 2006;48:149–156. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000228320.23697.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rodriguez-Iturbe B, Quiroz Y, Nava M, Bonet L, Chavez M, Herrera-Acosta J, Johnson RJ, Pons HA. Reduction of renal immune cell infiltration results in blood pressure control in genetically hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2002;282:F191–201. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.0197.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rodriguez-Iturbe B, Pons H, Quiroz Y, Gordon K, Rincon J, Chavez M, Parra G, Herrera-Acosta J, Gomez-Garre D, Largo R, Egido J, Johnson RJ. Mycophenolate mofetil prevents salt-sensitive hypertension resulting from angiotensin II exposure. Kidney Int. 2001;59:2222–2232. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00737.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Quiroz Y, Pons H, Gordon KL, Rincon J, Chavez M, Parra G, Herrera-Acosta J, Gomez-Garre D, Largo R, Egido J, Johnson RJ, Rodriguez-Iturbe B. Mycophenolate mofetil prevents salt-sensitive hypertension resulting from nitric oxide synthesis inhibition. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2001;281:F38–47. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2001.281.1.F38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guzik TJ, Hoch NE, Brown KA, McCann LA, Rahman A, Dikalov S, Goronzy J, Weyand C, Harrison DG. Role of the T cell in the genesis of angiotensin II induced hypertension and vascular dysfunction. J Experimental Med. 2007;204:2449–2460. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Crowley SD, Song YS, Lin EE, Griffiths R, Kim HS, Ruiz P. Lymphocyte responses exacerbate angiotensin II-dependent hypertension. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2010;298:R1089–1097. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00373.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vinh A, Chen W, Blinder Y, Weiss D, Taylor WR, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM, Harrison DG, Guzik TJ. Inhibition and genetic ablation of the B7/CD28 T-cell costimulation axis prevents experimental hypertension. Circulation. 2010;122:2529–2537. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.930446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rudemiller N, Lund H, Jacob HJ, Geurts AM, Mattson DL. Cd247 modulates blood pressure by altering T-lymphocyte infiltration in the kidney. Hypertension. 2014;63:559–564. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.02191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mattson DL, Lund H, Guo C, Rudemiller N, Geurts AM, Jacob H. Genetic mutation of recombination activating gene 1 in Dahl salt-sensitive rats attenuates hypertension and renal damage. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2013;304:R407–414. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00304.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hooper LV, Macpherson AJ. Immune adaptations that maintain homeostasis with the intestinal microbiota. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:159–169. doi: 10.1038/nri2710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dong C. Diversification of t-helper-cell lineages: Finding the family root of IL-17-producing cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:329–333. doi: 10.1038/nri1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhu J, Yamane H, Paul WE. Differentiation of effector CD4 T cell populations. Annu Rev Immunol. 2010;28:445–489. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Luckheeram RV, Zhou R, Verma AD, Xia B. CD4+ T cells: Differentiation and functions. Clin Dev Immunol. 2012;2012:925135. doi: 10.1155/2012/925135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zuniga LA, Jain R, Haines C, Cua DJ. Th17 cell development: From the cradle to the grave. Immunol Rev. 2013;252:78–88. doi: 10.1111/imr.12036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bedoya SK, Lam B, Lau K, Larkin J., 3rd Th17 cells in immunity and autoimmunity. Clinical Developmental Immunol. 2013;2013:986789. doi: 10.1155/2013/986789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kimura A, Kishimoto T. Th17 cells in inflammation. International Immunopharmacology. 2011;11:319–322. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tangye SG, Ma CS, Brink R, Deenick EK. The good, the bad and the ugly - Tfh cells in human health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:412–426. doi: 10.1038/nri3447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Harty JT, Tvinnereim AR, White DW. CD8+ T cell effector mechanisms in resistance to infection. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:275–308. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang N, Bevan MJ. CD8+ T cells: Foot soldiers of the immune system. Immunity. 2011;35:161–168. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ma F, Feng J, Zhang C, Li Y, Qi G, Li H, Wu Y, Fu Y, Zhao Y, Chen H, Du J, Tang H. The requirement of CD8+ T cells to initiate and augment acute cardiac inflammatory response to high blood pressure. J Immunol. 2014;192:3365–3373. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schiffrin EL. Immune mechanisms in hypertension and vascular injury. Clin Sci. 2014;126:267–274. doi: 10.1042/CS20130407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rodriguez-Iturbe B, Quiroz Y, Ferrebuz A, Parra G, Vaziri ND. Evolution of renal interstitial inflammation and nf-kappab activation in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Nephrol. 2004;24:587–594. doi: 10.1159/000082313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.De Miguel C, Guo C, Lund H, Feng D, Mattson DL. Infiltrating T lymphocytes in the kidney increase oxidative stress and participate in the development of hypertension and renal disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2011;300:F734–742. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00454.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Viel EC, Lemarie CA, Benkirane K, Paradis P, Schiffrin EL. Immune regulation and vascular inflammation in genetic hypertension. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;298:H938–944. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00707.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shao J, Nangaku M, Miyata T, Inagi R, Yamada K, Kurokawa K, Fujita T. Imbalance of T-cell subsets in angiotensin II-infused hypertensive rats with kidney injury. Hypertension. 2003;42:31–38. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000075082.06183.4E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yang XO, Pappu BP, Nurieva R, Akimzhanov A, Kang HS, Chung Y, Ma L, Shah B, Panopoulos AD, Schluns KS, Watowich SS, Tian Q, Jetten AM, Dong C. T helper 17 lineage differentiation is programmed by orphan nuclear receptors ROR alpha and ROR gamma. Immunity. 2008;28:29–39. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ivanov II, McKenzie BS, Zhou L, Tadokoro CE, Lepelley A, Lafaille JJ, Cua DJ, Littman DR. The orphan nuclear receptor RORgammat directs the differentiation program of proinflammatory IL-17+ T helper cells. Cell. 2006;126:1121–1133. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Korn T, Bettelli E, Oukka M, Kuchroo VK. IL-17 and Th17 cells. Annual Rev Immunol. 2009;27:485–517. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Amador CA, Barrientos V, Pena J, Herrada AA, Gonzalez M, Valdes S, Carrasco L, Alzamora R, Figueroa F, Kalergis AM, Michea L. Spironolactone decreases DOCA-salt-induced organ damage by blocking the activation of T helper 17 and the downregulation of regulatory T lymphocytes. Hypertension. 2014;63:797–803. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.02883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Madhur MS, Lob HE, McCann LA, Iwakura Y, Blinder Y, Guzik TJ, Harrison DG. Interleukin 17 promotes angiotensin II-induced hypertension and vascular dysfunction. Hypertension. 2010;55:500–507. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.145094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Krebs CF, Lange S, Niemann G, Rosendahl A, Lehners A, Meyer-Schwesinger C, Stahl RA, Benndorf RA, Velden J, Paust HJ, Panzer U, Ehmke H, Wenzel UO. Deficiency of the interleukin 17/23 axis accelerates renal injury in mice with deoxycorticosterone acetate+angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Hypertension. 2014;63:565–571. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.02620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Li Y, Wu Y, Zhang C, Li P, Cui W, Hao J, Ma X, Yin Z, Du J. γδT cell-derived interleukin-17A via an interleukin-1β-dependent mechanism mediates cardiac injury and fibrosis in hypertension. Hypertension. 2014 doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.02604. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tipton AJ, Baban B, Sullivan JC. Female spontaneously hypertensive rats have a compensatory increase in renal regulatory T cells in response to elevations in blood pressure. Hypertension. 2014 doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.03512. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chen J, Liu XS. Development and function of IL-10 IFN-gamma-secreting CD4+ T cells. J Leukocyte Biol. 2009;86:1305–1310. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0609406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kasal DA, Barhoumi T, Li MW, Yamamoto N, Zdanovich E, Rehman A, Neves MF, Laurant P, Paradis P, Schiffrin EL. T regulatory lymphocytes prevent aldosterone-induced vascular injury. Hypertension. 2012;59:324–330. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.181123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Barhoumi T, Kasal DA, Li MW, Shbat L, Laurant P, Neves MF, Paradis P, Schiffrin EL. T regulatory lymphocytes prevent angiotensin II-induced hypertension and vascular injury. Hypertension. 2011;57:469–476. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.162941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Matrougui K, Abd Elmageed Z, Kassan M, Choi S, Nair D, Gonzalez-Villalobos RA, Chentoufi AA, Kadowitz P, Belmadani S, Partyka M. Natural regulatory T cells control coronary arteriolar endothelial dysfunction in hypertensive mice. Am J Pathol. 2011;178:434–441. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.11.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tamosiuniene R, Tian W, Dhillon G, Wang L, Sung YK, Gera L, Patterson AJ, Agrawal R, Rabinovitch M, Ambler K, Long CS, Voelkel NF, Nicolls MR. Regulatory T cells limit vascular endothelial injury and prevent pulmonary hypertension. Circ Res. 2011;109:867–879. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.236927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kvakan H, Kleinewietfeld M, Qadri F, Park JK, Fischer R, Schwarz I, Rahn HP, Plehm R, Wellner M, Elitok S, Gratze P, Dechend R, Luft FC, Muller DN. Regulatory T cells ameliorate angiotensin II-induced cardiac damage. Circulation. 2009;119:2904–2912. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.832782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Viel EC, Lemarie CA, Benkirane K, Paradis P, Schiffrin EL. Immune regulation and vascular inflammation in genetic hypertension. Am J Physiol. 2010;298:H938–944. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00707.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kassan M, Galan M, Partyka M, Trebak M, Matrougui K. Interleukin-10 released by CD4+CD25+ natural regulatory T cells improves microvascular endothelial function through inhibition of NADPH oxidase activity in hypertensive mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:2534–2542. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.233262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Whitacre CC. Sex differences in autoimmune disease. Nature Immunol. 2001;2:777–780. doi: 10.1038/ni0901-777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Crowson CS, Liao KP, Davis JM, 3rd, Solomon DH, Matteson EL, Knutson KL, Hlatky MA, Gabriel SE. Rheumatoid arthritis and cardiovascular disease. Am Heart J. 2013;166:622–628 e621. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2013.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sinicato NA, da Silva Cardoso PA, Appenzeller S. Risk factors in cardiovascular disease in systemic lupus erythematosus. Current Cardiol Rev. 2013;9:15–19. doi: 10.2174/157340313805076304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ryan MJ. The pathophysiology of hypertension in systemic lupus erythematosus. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2009;296:R1258–1267. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90864.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Perez-Sepulveda A, Torres MJ, Khoury M, Illanes SE. Innate immune system and preeclampsia. Front Immunol. 2014;5:244. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Laresgoiti-Servitje E. A leading role for the immune system in the pathophysiology of preeclampsia. J Leukoc Biol. 2013;94:247–257. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1112603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cornelius DC, Hogg JP, Scott J, Wallace K, Herse F, Moseley J, Wallukat G, Dechend R, LaMarca B. Administration of interleukin-17 soluble receptor c suppresses Th17 cells, oxidative stress, and hypertension in response to placental ischemia during pregnancy. Hypertension. 2013;62:1068–1073. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.01514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tipton AJ, Baban B, Sullivan JC. Female spontaneously hypertensive rats have greater renal anti-inflammatory T lymphocyte infiltration than males. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2012;303:R359–367. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00246.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pettersson US, Walden TB, Carlsson PO, Jansson L, Phillipson M. Female mice are protected against high-fat diet induced metabolic syndrome and increase the regulatory T cell population in adipose tissue. PLoS One. 2012;7:e46057. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ji H, Zheng W, Li X, Liu J, Wu X, Zhang MA, Umans JG, Hay M, Speth RC, Dunn SE, Sandberg K. Sex-specific T-cell regulation of angiotensin II-dependent hypertension. Hypertension. 2014 doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.03663. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Pollow DP, Uhrlaub J, Romero-Aleshire MJ, Sandberg K, Nikolich-Zugich J, Brooks HL, Hay M. Sex differences in T-lymphocyte tissue infiltration and development of angiotensin II hypertension. Hypertension. 2014 doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.03581. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sampson AK, Jennings GL, Chin-Dusting JP. Y are males so difficult to understand?: A case where “X” does not mark the spot. Hypertension. 2012;59:525–531. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.187880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Page ST, Plymate SR, Bremner WJ, Matsumoto AM, Hess DL, Lin DW, Amory JK, Nelson PS, Wu JD. Effect of medical castration on CD4+ CD25+ T cells, CD8+ T cell IFNγ expression, and NK cells: A physiological role for testosterone and/or its metabolites. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2006;290:E856–863. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00484.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Fijak M, Schneider E, Klug J, Bhushan S, Hackstein H, Schuler G, Wygrecka M, Gromoll J, Meinhardt A. Testosterone replacement effectively inhibits the development of experimental autoimmune orchitis in rats: Evidence for a direct role of testosterone on regulatory T cell expansion. J Immunol. 2011;186:5162–5172. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Tai P, Wang J, Jin H, Song X, Yan J, Kang Y, Zhao L, An X, Du X, Chen X, Wang S, Xia G, Wang B. Induction of regulatory T cells by physiological level estrogen. J Cellular Physiol. 2008;214:456–464. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Gross ML, Adamczak M, Rabe T, Harbi NA, Krtil J, Koch A, Hamar P, Amann K, Ritz E. Beneficial effects of estrogens on indices of renal damage in uninephrectomized SHRsp rats. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:348–358. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000105993.63023.d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sullivan JC, Pardieck JL, Doran D, Zhang Y, She JX, Pollock JS. Greater fractalkine expression in mesenteric arteries of female spontaneously hypertensive rats compared with males. Am J Physiol. 2009;296:H1080–1088. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01093.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Dalpiaz PL, Lamas AZ, Caliman IF, Medeiros AR, Abreu GR, Moyses MR, Andrade TU, Alves MF, Carmona AK, Bissoli NS. The chronic blockade of angiotensin I-converting enzyme eliminates the sex differences of serum cytokine levels of spontaneously hypertensive rats. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2013;46:171–177. doi: 10.1590/1414-431X20122472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kyurkchiev D, Ivanova-Todorova E, Hayrabedyan S, Altankova I, Kyurkchiev S. Female sex steroid hormones modify some regulatory properties of monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2007;58:425–433. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2007.00526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Correale J, Ysrraelit MC, Gaitan MI. Gender differences in 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin d3 immunomodulatory effects in multiple sclerosis patients and healthy subjects. J Immunol. 2010;185:4948–4958. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Liva SM, Voskuhl RR. Testosterone acts directly on CD4+ T lymphocytes to increase IL-10 production. J Immunol. 2001;167:2060–2067. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.4.2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Tyagi AM, Srivastava K, Mansoori MN, Trivedi R, Chattopadhyay N, Singh D. Estrogen deficiency induces the differentiation of IL-17 secreting Th17 cells: A new candidate in the pathogenesis of osteoporosis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e44552. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Saraiva M, O’Garra A. The regulation of IL-10 production by immune cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:170–181. doi: 10.1038/nri2711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Bautista LE, Vera LM, Arenas IA, Gamarra G. Independent association between inflammatory markers (c-reactive protein, interleukin-6, and TNF-alpha) and essential hypertension. J Human Hypertension. 2005;19:149–154. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Pruijm M, Vollenweider P, Mooser V, Paccaud F, Preisig M, Waeber G, Marques-Vidal P, Burnier M, Bochud M. Inflammatory markers and blood pressure: Sex differences and the effect of fat mass in the colaus study. J Human Hypertension. 2013;27:169–175. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2012.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Herrera J, Ferrebuz A, MacGregor EG, Rodriguez-Iturbe B. Mycophenolate mofetil treatment improves hypertension in patients with psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:S218–225. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006080918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]