Abstract

Obesity is associated with an increased risk of cancer. The mechanisms underlying this association include but are not limited to increased systemic inflammation, an anabolic hormonal milieu, and adipocyte-cancer crosstalk, aberrant stimuli that conspire to promote neoplastic transformation. Cellular proliferation is uncoupled from nutrient availability in malignant cells, promoting tumor progression. Elucidation of the mechanisms underlying the obesity-cancer connection will lead to the development of novel metabolism-based agents for cancer prevention and treatment.

Keywords: obesity, cancer, metabolism, inflammation, adipocyte, Akt, AMPK, PTEN

Epidemiology

Obesity is associated with increased incidence and mortality of multiple cancers, with risk ratios correlating directly with body mass index (BMI) in a dose-dependent fashion. The relationship between BMI and cancer is non-linear and amplified at high BMI: the risk ratio for mortality from endometrial cancer, among the highest of all cancers, is 1.5 for overweight women (BMI 25–30), 2.5 for women with class 1 obesity (BMI 30–35), and rises to over 6 in women with class 3 obesity (BMI>40). Obesity is a particularly strong risk factor for colon, renal, pancreatic, and esophageal adenocarcinomas as well, with similar dramatic increases in risk at high BMI. This high degree of risk translates into a substantial disease burden: obesity is estimated to be a dominant causative factor in 10–20% of all cases of cancer (1–3).

While obesity increases the risk of most cancers, exceptions exist. Obesity is associated with a decreased risk of lung cancer and squamous cell cancer of the esophagus (1–4), cancers for which smoking is an important risk factor, confounding analysis of the effect of BMI. While obesity increases breast cancer risk in post-menopausal women, no such association exists in premenopausal women, in whom some data suggest that elevated BMI may exert a protective effect (2). Data is conflicting regarding obesity’s effects on prostate cancer incidence, with different studies demonstrating a weak positive effect, no effect, or a weak protective effect (5–8). Lower androgen levels in obese men may explain an observed protective effect, and differences among studies may relate to differences in androgen sensitivity of individual prostate cancers.

Obesity not only affects cancer incidence and long-term cancer-specific mortality, but also impacts on survival and recurrence among those diagnosed with cancer. Despite conflicting data regarding obesity’s effects on prostate cancer incidence, compelling data demonstrate decreased survival among obese patients compared to lean patients who develop prostate cancer (9–11). Other cancers associated with worse prognosis in the obese include colon (12), lymphoma (13), and breast (14). Treatment efficacy may underlie some of these observations. Under-dosing of chemotherapy, reduced delivery of radiation therapy, and technical challenges associated with extirpative surgery leading to lower rates of R-0 resections are reported in obese patients (15–18). Biologic effects of adipose tissue may interfere with cancer therapy; for example, aromatase inhibitor therapy is less effective at reducing serum estradiol levels in obese breast cancer patients (19), possibly related to increased aromatase activity from adipose tissue, while other data demonstrate that obesity is associated with decreased efficacy of cytotoxic chemotherapy in breast cancer patients (20). In contrast to these findings, in some cases obesity appears to exert a beneficial effect on survival in patients diagnosed with cancer, the so-called “obesity paradox”. Obesity is a strong risk factor for the development of renal cell cancer, but obese patients who develop renal cell cancer experience longer survival compared to lean patients (21,22). Conflicting data suggest that obesity may be associated with more favorable outcomes in endometrial, head and neck, rectal, and esophageal cancer as well, even after controlling for tumor stage (23–26). The mechanisms underlying such protective effects are poorly defined. Obesity may be associated with decreased chemo- and radiation-therapy toxicities which may contribute to increased treatment efficacy in some cases (27, 28). Alternatively, limitations in BMI as a metric for obesity as well as selection bias and other statistical confounders have been proposed to discount the obesity paradox with respect to cancer survival (29, 30), which therefore remains controversial.

Multiple variables regulate the obesity-cancer risk equation. Gender and ethnic differences exist; risk ratios for obesity are significantly higher in men than women for colon cancer incidence, for example, while Asians suffer increased breast cancer risk at lower BMI compared to non-Asians (30). Similar to other metabolic diseases, visceral adiposity imparts greater risk than subcutaneous adiposity. Diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and other metabolic diseases are tightly linked to obesity but nonetheless exert independent effects on cancer incidence and mortality, and confound analysis of obesity as an independent predictor of risk. Similar confounding effects are exerted by dietary factors, which are also tightly correlated with obesity but nonetheless exert independent effects on cancer incidence; for example, high fat, low fiber diet, while associated with obesity, is a well-established independent risk factor for colon cancer. Despite these epidemiologic complexities, obesity is clearly a dominant causative agent in the pathogenesis of cancer. An understanding of the diverse molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying this association will drive development of novel diagnostic and therapeutic modalities.

Inflammation, nutrient excess, and cancer

Since Virchow first observed lymphocytes populating tumors in 1863 (31), thousands of reports have implicated inflammation in the pathogenesis of cancer. Inflammatory bowel disease, primary sclerosing cholangitis, hepatitis, and pancreatitis are but a few of many chronic inflammatory diseases associated with an increased risk of cancer in involved tissues. Immune leukocytes, including macrophages, neutrophils, monocytes, T-cells, B-cells, and natural killer (NK) cells, utilize multiple cytotoxic molecules, such as reactive oxygen species, free radicals, antibodies, and cytolytic proteins, to mediate inflammatory responses. Leukocytes also secrete cytokines, which potentiate leukocyte activation, proliferation, and inflammatory responses via autocrine and paracrine effects, and exert multiple effects on non-immune cells, including regulating proliferation and apoptosis. The specific mechanisms underlying the association between inflammation and cancer remain poorly defined, but at a conceptual level, increased mutagenesis resulting from exposure of cells to inflammatory weapons combined with increased cell turnover secondary to tropic effects of cytokines create a perfect storm for carcinogenesis.

Obesity is associated with a state of chronic systemic inflammation. The link between nutrient excess and inflammation is rooted in the chemical nature of nutrients, bioenergetic molecules capable of participating in energy-intensive reactions that are potentially damaging to cells. Cells have evolved protective systems designed to sequester and limit exposure to these molecules, including the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), a complex organelle present in all cells that meters exposure to nutrients. When inundated with nutrients beyond the capacity of the ER to manage, cells mount an ER stress response which leads to apoptosis. An inflammatory response is in turn generated to scavenge apoptotic cells. Cells damaged by excess nutrients are thus removed, limiting nutrient-mediated injury and protecting the organism as a whole. Excess nutrients, including free fatty acids, glucose, and downstream metabolites such as diacyglycerol, ceramides, and advanced glycation end-products, directly trigger leukocyte-mediated inflammation: free fatty acids are ligands for Toll-like receptors (TLR), which are expressed on innate immune cells and trigger inflammatory responses, while advanced glycation end-products bind leukocyte receptors for advanced glycation end-products (RAGE) with similar effects. TLR and RAGE ligands represent direct molecular links between metabolism and inflammation.

Adipose tissue in health acts as a nutrient buffer, protecting other tissues by storing excess nutrients in adipocytes in the form of lipid. As adipocytes reach hypertrophic capacity in overweight and obese subjects, ER stress ensues, and leukocytes are recruited to scavenge apoptotic adipocytes. The resulting adipose tissue inflammatory leukocyte infiltrate is dominated by macrophages, but also involves T-cells, B-cells, NK cells, and other immune cell subtypes. In early obesity, nutrient excess, ER stress, and inflammation remain confined to adipose tissue. With progressive obesity, adipocyte storage capacity is overwhelmed, nutrient buffering capacity is exceeded, and excess nutrients and metabolites overflow into the systemic circulation. Nutrient- and metabolite-induced cell stress spreads beyond adipose tissue, establishing a low grade inflammatory state in all tissues that underlies the pathogenesis of malignant and non-malignant metabolic disease.

Cytokines are central mediators of the link between inflammation and cancer. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), a dominant inflammatory cytokine expression of which is elevated in obesity, promotes cancers of the skin, liver and lymphoid system in murine models, while TNF-α knockout mice are protected from chemically-induced skin and colon cancers (32–36). Similar murine models implicate interleukins 2, 6 and 8 (IL-1, IL-6, and IL-8) in cancer initiation and progression, and expression of these cytokines is also elevated in obesity. Data from humans support a role for cytokines in cancer pathogenesis: for example, IL-6 and IL-8 gene polymorphisms are linked to gastric, colorectal, and esophageal cancers (37, 38). Inflammatory cytokines have multiple downstream effects that contribute to cancer pathogenesis. Cytokines activate inducible nitric oxide synthase, increasing nitric oxide levels, which induces tumor growth, metastasis and angiogenesis in multiple animal models (39, 40). Cytokines trigger cellular NFκB signaling, which has been implicated in carcinogenesis; inhibition of nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NFκB) is associated decreased neoplastic cell transformation and increased tumor sensitivity to chemotherapy (41–43). Inflammation is tightly linked to angiogenesis, a critical component of tumorigenesis. TNF-α, while inducing apoptosis in cells that suffer ER and oxidative stress, promotes proliferation of stromal and endothelial cells, potentiating fibrosis and angiogenesis within the tumor microenvironment. IL-1 is similarly required for angiogenesis and tumor progression in multiple animal models (44,45). Finally, cytokines play important roles in cell adhesion, chemotaxis, and migration, which along with other inflammatory chemokines, may contribute to tumor metastasis.

Diabetes provides an important example of the overlap between metabolism, inflammation, and carcinogenesis. Diabetes is an independent risk factor for multiple cancers, with the strongest data supporting a link with pancreatic and liver cancers (46). Inflammation is a major contributor to the pathogenesis of diabetes independent of cancer, and anti-inflammatory agents ameliorate diabetes. Aspirin was observed as early as 1901 to improve diabetes (47), while modern anti-inflammatory agents, including salsalate, a salicylate-derivative, and anti-TNF-α and anti-IL-1 antibodies, are currently in clinical trials as therapy for diabetes (48–50). Parallel data demonstrate a cancer preventive effect of long-term therapy with aspirin and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (51, 52). Taken together, these observations suggest that the processes that regulate inflammation, metabolism, and carcinogenesis are intertwined, and that inflammation-based therapy for metabolic disease may also demonstrate efficacy in preventing or treating cancer. Despite these exciting opportunities, enthusiasm for inflammation-based cancer therapy must be tempered by observations that suppression of immune and inflammatory responses also stimulates carcinogenesis. For example, inhibition of NFκB in certain in vitro and in vivo preclinical models is associated with tumorigenic effects depending on the context, and it is well-established than cancer risk is increased in patients treated with long-term immunosuppression. These observations speak to the narrow therapeutic window in which the “inflammatory rheostat” and immunotherapy must be tuned.

The anabolic hormonal milieu in obesity

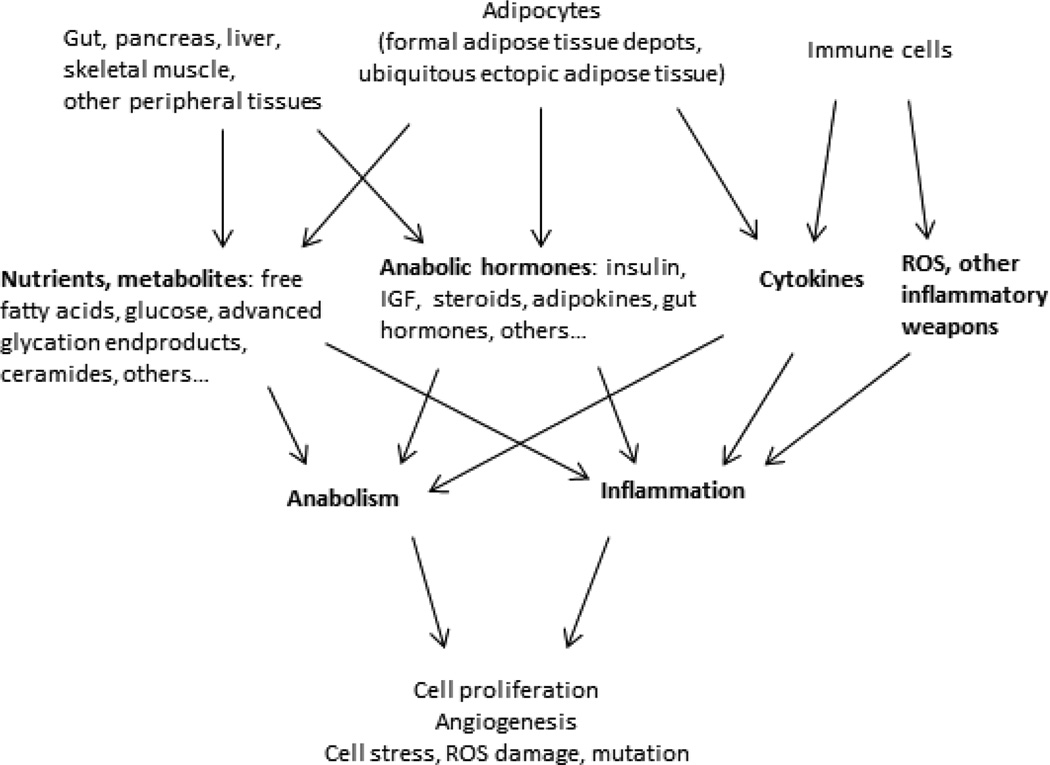

In addition to promoting inflammation, nutrient excess establishes a state of cellular and systemic anabolism characterized by increased expression of multiple growth factors, including insulin. Insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), steroid hormones, adipokines, and gut hormones. This anabolic environment promotes proliferation of pre-neoplastic and neoplastic cells, and when combined with mutagenic stimuli from chronic inflammation, creates an ideal environment for neoplasia (Figure 1). In support of a tumor-promoting anabolic state in obesity, breast cancers in obese compared to lean women demonstrate higher mitotic index, histologic grade, and tumor size, and among tumors controlled for size, express higher levels of proliferation markers (53).

Figure 1. Multiple factors influence carcinogenesis in obesity.

Chronic anabolism and inflammation are central sequelae of the many alterations in multiple organ systems observed in obesity. Direct effects of increased nutrient and metabolite delivery to cells promote cellular anabolism and proliferation, and directly stimulate the immune system via TLR and other receptor families. Increased systemic inflammation promotes cell damage, turnover, and mutagenesis. Cytokines, adipokines, steroids, and gut hormones are elevated in obesity and similarly promote cellular anabolism and proliferation and inflammation. Adipocytes within formal adipose tissue depots, as well as ectopic adipocytes present in virtually all tissues, contribute by providing nutrients, adipokines, and cytokines to all cells via paracrine and endocrine mechanisms. Tumors, once established, recruit adipocytes and adipocyte stem cells to enhance these effects. All of these pathways trigger ER and oxidative stress pathways which in turn perpetuate one another, leading to a vicious cycle of cell stress. The combination of anabolism and inflammation creates a systemic milieu that predisposes to carcinogenesis.

Insulin plays a dominant role in promoting the anabolic state in obesity. As adipose tissue buffering capacity is overwhelmed, free fatty acids spill into the systemic circulation. Peripheral tissues, most notably skeletal muscle and liver, respond by shifting energy production away from glucose utilization and towards fatty acid oxidation, decreasing expression of insulin receptors, glucose transporters, and insulin signaling molecules and increasing expression of enzymes involved in fatty acid catabolism. This shift in energy metabolism leads to systemic hyperglycemia, to which pancreatic islet beta cells respond with a compensatory increase in insulin secretion. These responses underlie the development of peripheral insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia, pathognomonic features of obesity.

Insulin is a potent growth factor that induces proliferation and inhibits apoptosis in a wide range of benign and malignant cells and promotes tumorigenesis in in vitro and in vivo models (54–60). Increased insulin levels in humans are independently associated with multiple cancers, including those most strongly associated with obesity, such as colon, endometrial, pancreas, and breast (61–64). Insulin receptor expression is increased in multiple cancers, including breast, prostate, hepatocellular, and leukemic cancers (65, 66). Insulin also promotes the expression of IGF-1, a hormone secreted primarily by the liver that stimulates the growth of numerous cancers in in vitro and in vivo models (67, 68). IGF-1 mediates its tropic effects by binding its own receptor as well as the insulin receptor, both of which are expressed on most normal cells and over-expressed in many tumors (65). IGF-1 also induces angiogenesis which has been linked to cancer progression (69). Similar to insulin, a preponderance of data suggest a correlation between serum IGF-1 levels and cancer in humans, and pre-clinical studies demonstrate a growth promoting effect of IGF-1 on cancer growth (61, 62, 64).

Steroid hormones contribute to obesity-related cancer. Clinical and mechanistic data strongly implicate steroid hormones in multiple cancers independent of obesity, most notably breast, endometrial, and ovarian. Serum steroid hormone levels correlate directly with the risks of these cancers (70–75), while numerous in vitro and in vivo experimental models support a role for steroid hormones in tumor progression. Multiple mechanisms contribute to elevated steroid hormone levels in obesity. Elevated estradiol levels result from increased conversion of androgens to estradiol by aromatase expressed in white adipose tissue. While the ovaries are the chief source of estrogen in premenopausal women, in postmenopausal women adipose tissue becomes a dominant source, and this may also be the case in obese premenopausal women. Expression of TNF-α, IL-6, and leptin are increased in obese adipose tissue, and these cytokines and adipokines induce aromatase expression by adipocytes, exacerbating adipose tissue steroidogenesis (76, 77). Insulin, IGF-1, and glucose, also increased in obesity, inhibit expression of sex hormone-binding globulin by the liver, increasing systemic bioavailability of steroid hormones (78). Finally insulin induces ovarian and adrenal androgen synthesis, increasing androgen levels as well as estradiol levels by providing androgen substrate for adipose tissue aromatase.

Serum levels of steroid hormones are elevated in obesity (79, 80), and reduced with diet-or surgery-induced weight loss with a concomitant reduction in cancer risk (81–85). Animal models of obesity are associated with increased incidence and growth of steroid hormone-sensitive tumors (86–89). Breast cancer is one of the best-studied steroid-sensitive cancers and is strongly associated with obesity. Supporting a role for obesity-related aberrations in estrogen in breast cancer are observations that obesity is more often associated with estrogen receptor (ER)+ breast cancers (90, 91). Furthermore, while ER+ breast cancers generally have a more favorable prognosis than ER− tumors, this may not be true in obese patients; in at least one large population based study, mortality was substantially higher in obese patients with ER+ tumors compared with lean patients with similar tumor histology (92), suggesting that elevated circulating estrogen in obesity may stimulate ER+ breast cancer growth.

Adipokines are secreted primarily by adipose tissue and exert broad effects on multiple aspects of physiology via hormonal and paracrine mechanisms. Dysregulated adipokine expression contributes to the anabolic state in obesity. Leptin, secreted primarily by adipocytes, and adiponectin, secreted by both adipocytes and adipose tissue stromal cells, are dominant adipokines with pleiotropic and opposing effects. Leptin, expression of which is increased in obesity, promotes metabolic disease, insulin resistance, and inflammation, while adiponectin, expression of which is decreased in obesity, has opposite effects. A similar dichotomy is evident in the effects of leptin and adiponectin on neoplastic growth. Serum levels of leptin correlate directly, and adiponectin indirectly, with the risk of multiple cancers, including breast, colon, prostate, endometrial, gastric, colorectal, and leukemic cancers (93–99). In vitro and in vivo models support this functional dichotomy, with leptin promoting and adiponectin inhibiting the growth of multiple types of cancer cells and tumors in pre-clinical models via opposing effects on cell proliferation and apoptosis (56, 100, 101). Leptin promotes and adiponectin suppresses angiogenesis, effects that have also been implicated in tumorigenesis. Adiponectin inhibits angiogenesis in part via induction of endothelial cell apoptosis, and when administrated to animals with sarcomas, suppresses tumor growth (100). Cancer cells, including hepatocellular and breast cancers, exploit the tropic effects of leptin by up-regulating expression of the leptin receptor, and elevated tumor expression of the leptin receptor in breast cancer is associated with worse prognosis (102,103).

Adipokines regulate inflammation, energy homeostasis, steroid hormone metabolism, and expression of multiple growth factors. Numerous adipokines in addition to leptin and adiponectin are dysregulated in obesity, contribute to metabolic disease, and are implicated in cancer pathogenesis, including visfatin, resistin, and apelin. Targeting adipokine signaling holds promise as cancer therapy. Leptin antagonist peptides demonstrate therapeutic efficacy in preclinical models of breast endometrial and cancer (104, 105), while adiponectin agonists have been studied with similar results (106).

Emerging data suggest a contribution of gut hormones to the anabolic state in obesity and in carcinogenesis. Ghrelin, an orexigenic hormone secreted by the stomach, promotes growth of gastrointestinal and prostate cancers (107–109). Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), a gut hormone secreted by the proximal duodenum, levels of which are decreased in obesity and increased by bariatric surgery, has beneficial effects on metabolism. GLP-1 inhibits cancer growth in in vitro and in vivo models of colon, pancreatic and cholangiocarcinoma (110,111), although separate data suggest that GLP-1 agonists may increase cancer risk (112). Multiple other gut hormones are dysregulated in obesity and exert tropic and other cancer-promoting effects on cells. Like the adipokines, gut hormones engage in crosstalk with insulin, IGF, and steroid hormones, and also regulate inflammation. The role of this family of hormones in mediating carcinogenesis is an active area of research.

Adipocyte-tumor crosstalk

Emerging data suggest that adipocytes participate in crosstalk with pre-neoplastic and neoplastic cells that promotes cancer initiation and progression. Adipocyte infiltration of the pancreas and breast predisposes to cancers in these organs (113–115), while histologic evidence of peri-tumor adipocytes predicts a poor prognosis in multiple cancers (116–118). Robust pre-clinical data demonstrate that adipocytes potentiate tumor cell proliferation and invasion in in vitro and in vivo models in multiple cancers (119–126).

The anatomic basis of adipocyte-tumor crosstalk is complex. Adipocytes influence preneoplastic and neoplastic cells via endocrine and paracrine mechanisms. Adipokines and steroid hormones secreted directly from canonical adipose tissue depots, as well as secondary endocrine effects of increased adipose tissue mass (e.g. hyperinsulinemia), discussed above, exert tropic endocrine effects on multiple target tissues and have been implicated in carcinogenesis. Many tumors associated with obesity reside near canonical anatomic adipose tissue depots, including renal, pancreatic, hepatic, and colon, and are thus also subject to paracrine effects of adipokines and other adipocyte products. Renal and pancreatic cancers are examples of tumors that arise in tissues surrounded by retroperitoneal and visceral fat that have especially high risk ratios for elevated BMI. Independent of formal anatomic adipose tissue depots, adipocytes are central components of the stromal microenvironment of multiple tissues in which tumors arise, and thus exist in intimate association with pre-neoplastic and neoplastic cells. Finally, tumors not only exploit pre-existing adipocytes present in stromal tissues, but also recruit adipose tissue stem cells from remote sites, which differentiate into adipocytes, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells, contributing to the tumor microenvironment and promoting neoplastic growth (127).

An important mechanism by which adipocytes promote carcinogenesis is reciprocal metabolic programming that leads to energy transfer from adipocytes to cancer cells. Adipocytes provide glutamine to leukemia cells and free fatty acids to ovarian cancer cells, promoting tumorigenesis in these cancers (128, 129). Tumor cells and adipocytes participate in crosstalk which reprograms adipocyte metabolism to enhance metabolic substrate shuttling: ovarian cancer cells, for example, inhibit lipogenesis and induce lipolysis in adipocytes, promoting free fatty acid transfer to tumor cells (128); breast cancer cells similarly induce a de-differentiated, fibrotic, glycolytic phenotype in adipocytes that predisposes to increased energy substrate transfer to tumor cells (130, 131). Wnt signaling represents a potential underlying mechanism of induction of adipocyte de-differentiation and fibrosis by cancer cells. A large body of literature implicates Wnt signaling in multiple cancers, and Wnt signaling is an established negative regulator of adipocyte differentiation independent of cancer. Breast cancer-induced de-differentiation of adipocytes is mediated by breast-cancer-derived Wnt ligands (130), suggesting Wnt signaling mediators as targets for interfering in adipocyte-cancer crosstalk. Emerging research suggests other avenues for exploiting adipocytes as targets for cancer therapy. Thiazolidinediones (TZDs) promote adipocyte differentiation; induction of a differentiated, less tumorigenic adipocyte phenotype may underlie the observed decrease in cancer incidence among patients treated with TZDs (132). Manipulation of peri-tumor adipocyte phenotype to reduce fibrosis and energy substrate transfer to tumors via interference in Wnt and other signaling pathways represents a promising strategy for adipocyte-based cancer therapy.

Other factors contributing to the cancer-obesity connection

In addition to aforementioned effects on the systemic inflammatory and hormonal milieu, nutrients and metabolites directly regulate tumor cell growth in in vitro models. Saturated free fatty acids promote the growth of multiple cancer cells, while unsaturated free fatty acids promote cancer cell apoptosis (133, 134), effects mediated in part via regulation of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling (135). Similar data demonstrate tumor promoting effects of advanced glycation end products (136). In addition, obesity is associated with an increased risk of a number of nutrient deficiencies that have been implicated in cancer pathogenesis, including vitamin D, selenium, and magnesium. Challenges persist in distinguishing between primary effects of nutrients and metabolites on neoplastic cells and secondary effects mediated via inflammatory and hormonal mechanisms, and the relative roles of nutrient excess and micronutrient deficiencies on cancer risk in the obese. Nonetheless, dietary modification and “nutraceutical” therapy for cancer prevention and treatment continue to generate interest and may play a particularly important role in obesity.

Another emerging focus of study is the role of the microbiome in contributing to cancer in obesity. Obesity is associated with alterations in the gut microbiome that are linked to metabolic disease (137). These changes include an increase in gram-negative gut bacteria with increased absorption of lipopolysaccharide from the gut (138, 139), potentially contributing to inflammation. Microbiome-derived metabolites, including heterocyclic amines, nitrosamines, and fecapentaenes, production of which are elevated as a result of increased dietary meat and fat, act as mutagens and may contribute to carcinogenesis. Alterations in bile acid metabolism secondary to changes in the microbiome in obesity may also contribute to oxidative damage and mutagenesis. Research into the role of the microbiome in obesity and cancer is rapidly evolving.

Cell signaling pathways linking energy homeostasis and carcinogenesis

The association between obesity and cancer is rooted in the intimate relationship between the fundamental processes that regulate energy homeostasis and survival in all cells. Cellular metabolism is tightly linked to proliferation and apoptosis, which adjust thresholds for these processes in response to nutrient delivery. Non-malignant cells appropriately engage in anabolic processes and proliferation when nutrients are plentiful, and shift to a catabolic, non-proliferative, apoptosis-prone state when nutrients are scarce. Malignant cells, in contrast, demonstrate uncoupling of cellular metabolism and proliferation. In a sense, cancer may be considered a disorder of cellular metabolism in which the link between nutrient availability and cellular regulation of metabolism is disrupted and anabolism and proliferation predominate over catabolism and apoptosis regardless of nutrient availability.

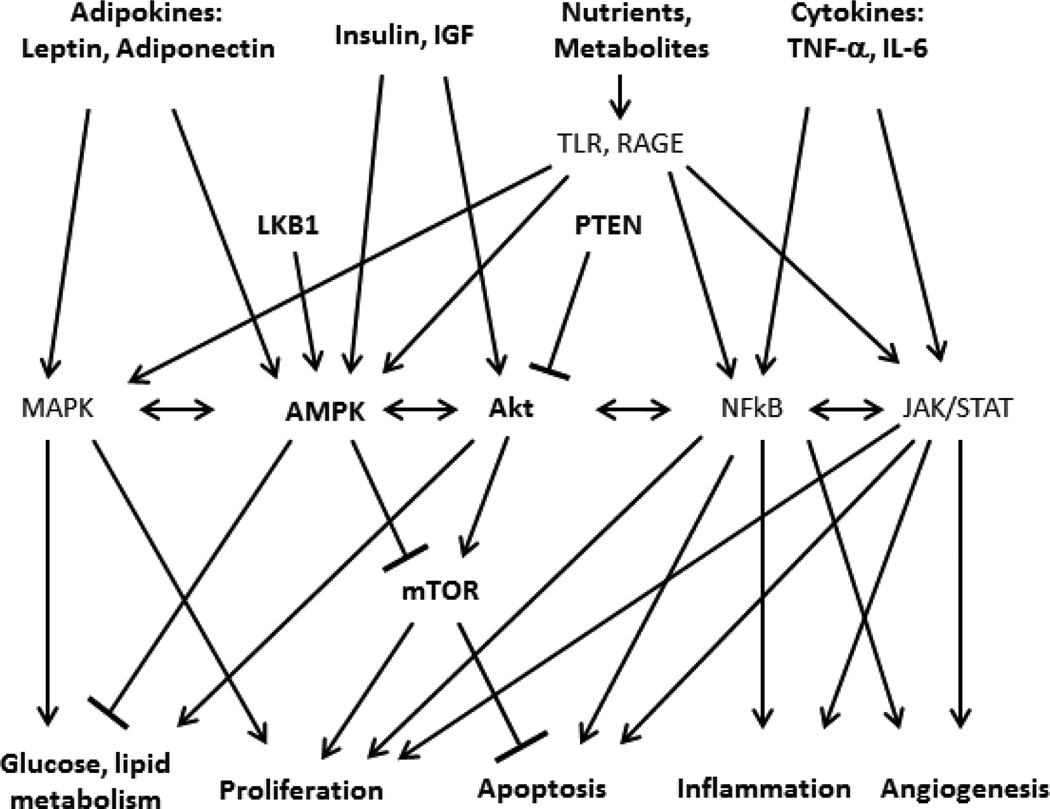

The signaling pathways that regulate cellular metabolism and cell survival are activated by multiple aberrant stimuli in obesity and participate in robust crosstalk (Figure 2). Protein kinase B (Akt) and adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase α (AMPK) are dominant signaling pathways that link metabolism and proliferation in all cells. Akt is a central signaling nexus that is activated by insulin during periods of nutrient availability and plays a dominant role in the regulation cellular glucose and lipid metabolism. In addition its metabolic functions, Akt also controls cellular survival by activating mTOR, a downstream signaling pathway that promotes cell proliferation and inhibits apoptosis. AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), in contrast, is a central cell signaling mediator that is activated when nutrient stores are low; increased cellular AMP levels are a dominant trigger for AMPK activation. Adiponectin, levels of which are decreased in obesity, also activates AMPK. AMPK induces a catabolic state in cells, in part by inhibiting Akt. AMPK also directly inhibits mTOR activity, thus attenuating cell proliferation. Akt and AMPK thus act as opposing forces that link cellular energy homeostasis with cell growth in response to nutrient availability. Phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) and liver kinase B1 (LKB1) are intermediate signaling molecules that regulate the balance of Akt and AMPK activity, adding a another layer of regulatory control. Both PTEN, which inhibits Akt, and LKB1, which activates AMPK, are activated by nutrient depletion and induce a catabolic state in cells and, through downstream effects on mTOR, also inhibit cellular proliferation.

Figure 2. Simplified schematic of major cell signaling pathways that link energy homeostasis and carcinogenesis.

Primary cell stimuli include adipokines, insulin, IGF-1, nutrients and metabolites including free fatty acids, and their derivatives such as ceramide, (which activate Toll-like receptors, TLR), and advanced glycation end-products (which activate receptors for advanced glycation end-products (RAGE)), and cytokines. Adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase α (AMPK) and Akt are central cell signaling nexuses that control metabolism and proliferation, in part by regulating mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR). Other pathways including mitogen activated protein kinases (MAPK), NFkB, and Janus kinase/ Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription (JAK/STAT) signaling mediators. Intermediate signaling mediators, including liver kinase B1 (LKB1) and phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN), add further regulatory control. All stimuli and pathways engage in highly redundant crosstalk via cross-reactivity of intracellular signaling mediators and transcriptional programs. The resulting complex interactome mediates the link between cellular energy homeostasis and cell survival.

Similar signaling crosstalk links cellular metabolism and inflammation. Nutrient activation of TLR and RAGE trigger inflammatory responses via activation of the central signaling mediator NFκB, which, in addition to inducing a transcriptional program that activates inflammation, also regulates proliferation and apoptosis in all cells, as well as angiogenesis, processes required for the cell turnover that accompanies both sterile and non-sterile inflammatory responses. Janus kinase/Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription (Jak/STAT) and mitogen activated protein kinases (MAPK) signaling pathways are activated by cytokines and adipokines and regulate these same fundamental processes. All of these signaling pathways participate in crosstalk, share intracellular signaling mediators and exert overlapping redundant functions that together creates a highly complex interactome that controls cell homeostasis. In situation of episodic nutrient availability, these numerous interacting signals cycle on and off in response to feeding and fasting. In situations of chronic nutrient excess, in contrast, these pathways are chronically activated, promoting hyperplasia and eventual neoplasia. Neoplastic cells, once established, further exploit signaling crosstalk by selecting for mutations that uncouple inhibitory feedback pathways that in normal cells limit anabolic metabolism and proliferation when nutrients are scarce. Mutations in Akt and AMPK pathways are among the most common in all cancers. Activating mutations in Akt are present in 20–100% of human tumors depending on the type of cancer studied (140). The genes encoding both PTEN and LKB1 are tumor suppressor genes associated with hereditary and sporadic cancers. Mutation in the LKB1 gene underlies Puetz-Jeghers syndrome, an autosomal dominant disorder characterized by intestinal hamartomas and an increased risk of gastrointestinal cancer, while mutation in the PTEN gene is associated with Cowden’s syndrome, an autosomal dominant disorder associated with benign and malignant tumors of multiple tissues. LKB1 and PTEN are also are among the most commonly mutated genes in many spontaneous cancers. These oncogenic mutations act to increase Akt activity and inhibit AMPK activity regardless of nutrient availability, uncoupling cell proliferation from nutrient status and providing a growth advantage to malignant cells.

The link between cellular control of metabolism and proliferation presents opportunities for metabolism-based cancer therapy. Recent data demonstrate that pharmacologic agents used to treat diabetes impact on carcinogenesis. Data suggest that long-term treatment with insulin or insulin secretagogues (i.e. sulfonylureas) is associated with elevated cancer risk, presumably due to insulin’s tropic effects on cells; conversely, treatment with metformin and TZDs attenuates cancer risk (132, 141, 142). The mechanisms underlying these anti-neoplastic effects are likely multiple. Both metformin and TZDs reduce serum insulin levels, thus attenuating tropic stimuli delivered to pre-neoplastic and neoplastic cells. Metformin also activates AMPK and in doing so may recouple cell energy status to proliferation. These observations suggest that current pharmacologic agents used to treat metabolic disease may demonstrate efficacy in preventing or treating cancer. Pre-clinical studies exploring next generation metabolic anti-cancer agents are in progress, including delivery of wild-type PTEN to cancer cells via exosomes, as well as pharmacologic agents designed to up-regulate PTEN and LKB1 expression (143). Targeting cell metabolism holds significant promise for cancer therapy.

Bariatric surgery and cancer

Both diet- and surgery-induced weight loss reduce the risk of cancer associated with obesity (144–149). Documented reductions in inflammatory mediators, insulin, IGF, steroid, and adipokine levels likely contribute to this effect and correlate with reduction in adipose tissue mass. Bariatric surgery also induces alterations in gut hormone homeostasis and bile acid metabolism distinct from diet-induced weight loss; the contributions of these mechanisms to cancer risk reduction are currently unclear. In addition, bariatric surgery, in contrast to diet-induced weight loss, is associated with increased metabolic rate in humans and rodents, and rodent models of bariatric surgery demonstrate a shift in cellular energy homeostasis towards a catabolic AMPK-dominated signaling milieu, suggesting that surgery influences energy homeostasis at the cellular level (150–153). These qualitative differences in metabolism after diet- and surgery-induced weight loss suggest different mechanisms of action, independent of loss of adipose tissue mass. These provocative findings reinforce the concept of cancer as a disorder of metabolism and suggest a role for bariatric and metabolic surgery in cancer prevention.

Conclusion

The association between obesity and cancer is rooted in the fundamental and intimate link between the processes that regulate cellular energy homeostasis and those that regulate cell survival, proliferation, and apoptosis. Obesity leads to dysregulation of inflammatory, endocrine, and metabolic signaling pathways, all of which engage in robust and redundant crosstalk, generating a highly complex interactome that underlies the cancer-obesity link. Chronic over-nutrition promotes cell transformation in pre-neoplastic cells by creating an environment characterized by both anabolism and inflammation. Once neoplastic transformation occurs, mutations in cancer cells uncouple cellular nutrient availability to proliferation, promoting tumor progression. An understanding of the molecular and cellular mechanisms that underlie these processes will lead to novel metabolism-based cancer therapy.

Acknowledgments

Funding: RWO is supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01DK097449, R03DK095050, by a Michigan Metabolomics-Obesity Center/Michigan Nutrition-Obesity Research Center Pilot Grant, and a Michigan Institute for Clinical & Health Research T1 Bench to Bedside Translation Pilot Grant.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest: Dr. O’Rourke has no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Calle EE, Rodriguez C, Walker-Thurmond K, Thun MJ. Overweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of U.S. adults. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1625–1638. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Renehan AG, Tyson M, Egger M, Heller RF, Zwahlen M. Body-mass index and incidence of cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. Lancet. 2008;371:569–578. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60269-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reeves GK, Pirie K, Beral V, Green J, Spencer E, Bull D. Cancer incidence and mortality in relation to body mass index in the Million Women Study: cohort study. BMJ. 2007;335:1134. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39367.495995.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leung CC, Lam TH, Yew WW, Chan WM, Law WS, Tam CM. Lower lung cancer mortality in obesity. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40:174–182. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giovannucci E, Rimm EB, Liu Y, et al. Body mass index and risk of prostate cancer in U.S. health professionals. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:1240–1244. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pan SY, Johnson KC, Ugnat AM, Wen SW, Mao Y. Canadian Cancer Registries Epidemiology Research Group. Association of obesity and cancer risk in Canada. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:259–268. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Samanic C, Gridley G, Chow WH, Lubin J, Hoover RN, Fraumeni JF., Jr. Obesity and cancer risk among white and black United States veterans. Cancer Causes Control. 2004;15:35–43. doi: 10.1023/B:CACO.0000016573.79453.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Engeland A, Tretli S, Bjorge T. Height, body mass index, and prostate cancer: a follow-up of 950,000 Norwegian men. Br J Cancer. 2003;89:1237–1242. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.MacInnis RJ, English DR. Body size and composition and prostate cancer risk: systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Cancer Causes Control. 2006;17:989–1003. doi: 10.1007/s10552-006-0049-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Potischman N, Swanson CA, Siiteri P, Hoover RN. Reversal of relation between body mass and endogenous estrogen concentrations with menopausal status. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996;88:756–758. doi: 10.1093/jnci/88.11.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.IARC –International Agency for Research on Cancer Working Group on the Evaluation of Cancer-Preventive Strategies. Weight control and physical activity. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu S, Liu J, Wang X, Li M, Gan Y, Tang Y. Association of obesity and overweight with overall survival in colorectal cancer patients: a meta-analysis of 29 studies. Cancer Causes Control. 2014 Jul 29; doi: 10.1007/s10552-014-0450-y. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leo QJ, Ollberding NJ, Wilkens LR, et al. Obesity and non-Hodgkin lymphoma survival in an ethnically diverse population: the Multiethnic Cohort study. Cancer Causes Control. 2014 Jul 29; doi: 10.1007/s10552-014-0447-6. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robinson PJ, Bell RJ, Davis SR. Obesity is associated with a poorer prognosis in women with hormone receptor positive breast cancer. Maturitas. 2014 Jul 18; doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2014.07.004. pii:S0378-5122(14)00232-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Griggs JJ, Sorbero MES, Lyman GH. Undertreatment of obese women receiving breast cancer chemotherapy. Arch Int Med. 2005;165:1267–1273. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.11.1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoon WS, Yang DS, Lee JA, Lee S, Park YJ, Kim CY. Risk factors related to interfractional variation in whole pelvic irradiation for locally advanced pelvic malignancies. Strahlenther Onkol. 2012;188:395–401. doi: 10.1007/s00066-011-0049-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin LL, Hertan L, Rengan R, Teo BK. Effect of body mass index on magnitude of setup errors in patients treated with adjuvant radiotherapy for endometrial cancer with daily image guidance. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;83:670–675. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chromecki TF, Cha EK, Fajkovic H, et al. Obesity is associated with worse oncological outcomes in patients treated with radical cystectomy. BJU Int. 2013;111(2):249–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pfeiler G, Königsberg R, Hadji P, et al. Impact of body mass index on estradiol depletion by aromatase inhibitors in postmenopausal women with early breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2013;109:1522–1527. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Azambuja E, McCaskill-Stevens W, Francis P, et al. The effect of body mass index on overall and disease-free survival in node-positive breast cancer patients treated with docetaxel and doxorubicin-containing adjuvant chemotherapy: the experience of the BIG 02-98 trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;119:145–153. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0512-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choi Y, Park B, Jeong BC, et al. Body mass index and survival in patients with renal cell carcinoma: a clinical-based cohort and meta-analysis. Int J Cancer. 2013;132:625–634. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hakimi AA, Furberg H, Zabor EC, et al. Russo P. An epidemiologic and genomic investigation into the obesity paradox in renal cell carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:1862–1870. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Münstedt K, Wagner M, Kullmer U, Hackethal A, Franke FE. Influence of body mass index on prognosis in gynecological malignancies. Cancer Causes Control. 2008;19:909–916. doi: 10.1007/s10552-008-9152-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park SM, Lim MK, Shin SA, Yun YH. Impact of prediagnosis smoking, alcohol, obesity, and insulin resistance on survival in male cancer patients: National Health Insurance Corporation Study. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5017–5024. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.0243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parker AS, Lohse CM, Cheville JC, et al. Greater body mass index is associated with better pathologic features and improved outcome among patients treated surgically for clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Urology. 2006;68:741–746. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seishima R, Okabayashi K, Hasegawa H, et al. Obesity was associated with a decreased postoperative recurrence of rectal cancer in a Japanese population. Surg Today. 2014 May 21; doi: 10.1007/s00595-014-0899-z. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pai PC, Chuang CC, Tseng CK, et al. Impact of pretreatment body mass index on patients with head-and-neck cancer treated with radiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;83:e93–e100. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.11.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang J, Myles B, Wei C, et al. Obesity and outcomes in patients treated with chemoradiotherapy for esophageal carcinoma. Dis Esophagus. 2014;27:168–175. doi: 10.1111/dote.12074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gonzalez MC, Pastore CA, Orlandi SP, Heymsfield SB. Obesity paradox in cancer: new insights provided by body composition. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99:999–1005. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.071399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Renehan AG. The ‘obesity paradox'and survival after colorectal cancer: true or false? Cancer Causes Control. 2014 Aug 2; doi: 10.1007/s10552-014-0436-9. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Balkwill F, Mantovani A. Inflammation and cancer: back to Virchow? Lancet. 2001;357:539–545. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04046-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lind MH, Rozell B, Wallin RP, et al. Tumor necrosis factor receptor 1-mediated signaling is required for skin cancer development induced by NF-kappaB inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:4972–4997. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307106101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kitakata H, Nemoto-Sasaki Y, Takahashi Y, Kondo T, Mai M, Mukaida N. Essential roles of tumor necrosis factor receptor p55 in liver metastasis of intrasplenic administration of colon 26 cells. Cancer Res. 2002;62:6682–6687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arnott CH, Scott KA, Moore RJ, Robinson SC, Thompson RG, Balkwill FR. Expression of both TNF-alpha receptor subtypes is essential for optimal skin tumor development. Oncogene. 2004;23:1902–1910. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Knight B, Yeoh GC, Husk KL, et al. Impaired preneoplastic changes and liver tumor formation in tumor necrosis factor receptor type 1 knockout mice. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1809–1818. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.12.1809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Korner H, Cretney E, Wilhelm P, et al. Tumor necrosis factor sustains the generalized lymphoproliferative disorder (gld) phenotype. J Exp Med. 2000;191:89–96. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.1.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Camp NJ, Slattery ML. Classification tree analysis: a statistical tool to investigate risk factor interactions with an example for colon cancer (United States) Cancer Causes Control. 2002;13:813–823. doi: 10.1023/a:1020611416907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Savage SA, Abnet CC, Mark SD, et al. Variants of the IL8 and IL8RB genes and risk for gastric cardia adenocarcinoma and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13:2251–2257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bogdan C. Nitric oxide and the regulation of gene expression. Trends Cell Biol. 2001;11:66–75. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)01900-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cheng H, Wang L, Mollica M, Re AT, Wu S, Zuo L. Nitric oxide in cancer metastasis. Cancer Lett. 2014 Jul 29; doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.07.014. pii:S0304-3835(14)00351-6. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Biswas DK, Shi Q, Baily S, et al. NF-kappa B activation in human breast cancer specimens and its role in cell proliferation and apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:10137–10142. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403621101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Otsuka G, Nagaya T, Saito K, Mizuno M, Yoshida J, Seo H. Inhibition of nuclear factor-kappaB activation confers sensitivity to tumor necrosis factor-alpha by impairment of cell cycle progression in human glioma cells. Cancer Res. 1999;59:4446–4452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Duffey DC, Chen Z, Dong G, et al. Expression of a dominant-negative mutant inhibitor kappa B alpha of nuclear factor-kappaB in human head and neck squamous cell carcinoma inhibits survival, proinflammatory cytokine expression, and tumor growth in vivo. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3468–3474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saijo Y, Tanaka M, Miki M, et al. Proinflammatory cytokine IL-1 βpromotes tumor growth of Lewis lung carcinoma by induction of angiogenic factors: in vivo analysis of tumor-stromal interaction. J Immunol. 2002;169:469–475. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.1.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Voronov E, Shouval DS, Krelin Y, et al. IL-1 is required for tumor invasiveness and angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:2645–2650. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0437939100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vigneri P, Frasca F, Sciacca L, Pandini G, Vigneri R. Diabetes and Cancer. Endocrine-Related Cancer. 2009;16:1103–1123. doi: 10.1677/ERC-09-0087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Williamson RT. On the treatment of glycosuria and diabetes mellitus with sodium salicylate. Br Med J. 1901;1:760–762. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.2100.760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Faghihimani E, Aminorroaya A, Rezvanian H, Adibi P, Ismail-Beigi F, Amini M. Salsalate improves glycemic control in patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes. Acta Diabetol. 2013;50:537–543. doi: 10.1007/s00592-011-0329-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Larsen CM, Faulenbach M, Vaag A, et al. Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1517–1526. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ursini F, Naty S, Grembiale RD. Infliximab and insulin resistance. Autoimmun Rev. 2010;9:536–539. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2009.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bertagnolli MM, Eagle CJ, Zauber AG, et al. Celecoxib for the prevention of sporadic colorectal adenomas. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:873–884. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Arber N, Eagle CJ, Spicak J, et al. Celecoxib for the prevention of colorectal adenomatous polyps. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:885–895. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Daling JR, Malone KE, Doody DR, Johnson LG, Gralow JR, Porter PL. Relation of body mass index to tumor markers and survival among young women with invasive ductal breast carcinoma,”. Cancer. 2001;92:720–729. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010815)92:4<720::aid-cncr1375>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chappell J, Leitner JW, Solomon S, Golovchenko I, Goalstone ML, Draznin B. Effect of insulin on cell cycle progression in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Direct and potentiating influence. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:38023–38028. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104416200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ish-Shalom D, Christoffersen CT, Vorwerk P, et al. Mitogenic properties of insulin and insulin analogues mediated by the insulin receptor. Diabetologia. 1997;40(suppl 2):S25–S31. doi: 10.1007/s001250051393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fenton JI, Hord NG, Lavigne JA, et al. Leptin, insulin-like growth factor-1, and insulin-like growth factor-2 are mitogens in ApcMin/+but not Apc+/+colonic epithelial cell lines. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:1646–1652. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shafie SM, Grantham FH. Role of hormones in the growth and regression of human breast cancer cells (MCF-7) transplanted into athymic nude mice. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 1981;67:51–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shafie SM, Hilf R. Insulin receptor levels and magnitude of insulininduced responses in 7,12-dimethylbenz(a)anthracene-induced mammary tumors in rats. Cancer Res. 1981;41:826–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Heuson JC, Legros N. Influence of insulin deprivation on growth of the 7,12-dimethylbenz(a)anthracene induced mammary carcinoma in rats subjected to alloxan diabetes and food restriction. Cancer Res. 1972;32:226–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cocca C, Gutiérrez A, Núñez M, et al. Suppression of mammary gland tumorigenesis in diabetic rats. Cancer Detect. Prev. 2003;2:37–46. doi: 10.1016/s0361-090x(02)00130-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Calle EE, Kaaks R. Overweight, obesity and cancer:epidemiological evidence and proposed mechanisms. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:579–591. doi: 10.1038/nrc1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kaaks R, Toniolo P, Akhmedkhanov A, et al. Serum C-peptide, insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-I, Igf-binding proteins, and colorectal cancer risk in women. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1592–1600. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.19.1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schoen RE, et al. Increased blood glucose and insulin, body size, and incident colorectal cancer. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:1147–1154. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.13.1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lukanova A, Zeleniuch-Jacquotte A, Lundin E, et al. Prediagnostic levels of C-peptide, IGF-I, IGFBP-1-2 and-3 and risk of endometrial cancer. Int. J. Cancer. 2004;108:262–268. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Frasca F, Pandini G, Sciacca L, et al. The role of insulin receptors and IGF-I receptors in cancer and other diseases. Arch Phys Biochem. 2008;114:23–37. doi: 10.1080/13813450801969715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cox ME, Gleave ME, Zakikhani M, et al. Insulin receptor expression by human prostate cancers. Prostate. 2009;69:33–40. doi: 10.1002/pros.20852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Khandwala HM, McCutcheon IE, Flyvbjerg A, Friend KE. The effects of insulin-like growth factors on tumorigenesis and neoplastic growth. Endocr. Rev. 2000;21:215–244. doi: 10.1210/edrv.21.3.0399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.LeRoith D, Roberts CT., Jr. The insulin-like growth factor system and cancer. Cancer Lett. 2003;195:127–137. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(03)00159-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wu Y, Yakar S, Zhao L, Hennighausen L, LeRoith D. Circulating insulin-like growth factor-I levels regulate colon cancer growth and metastasis. Cancer Research. 2002;62:1030–1335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.The Endogenous Hormones and Breast Cancer Collaborative Group 2002. Endogenous sex hormones and breast cancer in postmenopausal women:reanalysis of nine prospective studies. J Natl Cancer Inst. 94:606–616. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.8.606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hankinson SE, Willett WC, Manson JE, Colditz GA, Hunter DJ, Spiegelman D, Barbieri RL, Speizer FE. Plasma sex steroid hormone levels and risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:1292–1299. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.17.1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Missmer SA, Eliassen AH, Barbieri RL, Hankinson SE. Endogenous estrogen, androgen, and progesterone concentrations and breast cancer risk among postmenopausal women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:1856–1865. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kaaks R, Rinaldi S, Key TJ, et al. Postmenopausal serum androgens, oestrogens and breast cancer risk:the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2005;12:1071–1082. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.01038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Allen NE, Key TJ, Dossus L, et al. Endogenous sex hormones and endometrial cancer risk in women in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) Endocr Relat Cancer. 2008;15:485–497. doi: 10.1677/ERC-07-0064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.O’Brien ME, Dowsett M, Fryatt I, Wiltshaw E. Steroid hormone profile in postmenopausal women with ovarian cancer. Eur J Cancer. 1994;30A(4):442–445. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(94)90414-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Purohit A, Newman SP, Reed MJ. The role of cytokines in regulating estrogen synthesis:implications for the etiology of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2002;4:65–69. doi: 10.1186/bcr425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Catalano S, Marsico S, Giordano C, et al. Leptin enhances, via AP-1, expression of aromatase in the MCF-7 cell line. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:28668–28676. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301695200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pugeat M, Nader N, Hogeveen K, Raverot G, Déchaud H, Grenot C. Sex hormone-binding globulin gene expression in the liver:drugs and the metabolic syndrome. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2010;316:53–59. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2009.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Key TJ, Appleby PN, Reeves GK, et al. Endogenous Hormones Breast Cancer Collaborative Group. Body mass index, serum sex hormones, and breast cancer risk in postmenopausal women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:1218–1226. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Paxton RJ, King DW, Garcia-Prieto C, Connors SK, Hernandez M, Gor BJ, Jones LA. Associations between body size and serum estradiol and sex hormone-binding globulin levels in premenopausal African American women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:E485–E490. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-2782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tchernof A, Nolan A, Sites CK, Ades PA, Poehlman ET. Weight loss reduces C-reactive protein levels in obese postmenopausal women. Circulation. 2002;105:564–569. doi: 10.1161/hc0502.103331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Berrino F, Bellati C, Secreto G, et al. Reducing bioavailable sex hormones through a comprehensive change in diet:the diet and androgens (DIANA) randomized trial. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2001;10:25–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Riedt CS, Brolin RE, Sherrell RM, Field MP, Shapses SA. True fractional calcium absorption is decreased after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14:1940–1948. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bastounis EA, Karayiannakis AJ, Syrigos K, Zbar A, Makri GG, Alexiou D. Sex hormone changes in morbidly obese patients after vertical banded gastroplasty. Eur Surg Res. 1998;30:43–47. doi: 10.1159/000008556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Christou NV, Lieberman M, Sampalis F, Sampalis JS. Bariatric surgery reduces cancer risk in morbidly obese patients. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2008;4:691–695. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2008.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Waxler SH, Tabar P, Melcher LP. Obesity and the time of appearance of spontaneous mammary carcinoma in C3H mice. Cancer Res. 1953;13:276–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wolff GL, Kodell RL, Cameron AM, Medina D. Accelerated appearance of chemically induced mammary carcinomas in obese yellow (Avy/A) (BALB/c Xvy) F1 hybrid mice. J Toxicol Environ Health. 1982;10:131–142. doi: 10.1080/15287398209530237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Haseman JK, Bourbina J, Eustis SL. Effect of individual housing and other experimental design factors on tumor incidence in B6C3F1 mice. Fundam Appl Toxicol. 1994;23:44–52. doi: 10.1006/faat.1994.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Seilkop SK. The effect of body weight on tumor incidence and carcinogenicity testing in B6C3F1 mice and F344 rats. Fundam Appl Toxicol. 1995;24:247–259. doi: 10.1006/faat.1995.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ahn J, Schatzkin A, Lacey JA, Jr., et al. Adiposity, adult weight change, and postmenopausal breast cancer risk. Arch Intern Med. 2008;167:2091–2100. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.19.2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Rose DP, Komninou D, Stephenson GD. Obesity, adipocytokines, and insulin resistance in breast cancer. Obes Rev. 2004;5:153–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2004.00142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Maehle BO, Tretli S. Pre-morbid body mass index in breast cancer:reversed effect on survival in hormone receptor negative patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1996;41:123–130. doi: 10.1007/BF01807157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Dallal CM, Brinton LA, Bauer DC, et al. B∼FIT Research Group. Obesity-related hormones and endometrial cancer among postmenopausal women:a nested case-control study within the B∼FIT cohort. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2013;20:151–160. doi: 10.1530/ERC-12-0229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Mantzoros C, Petridou E, Dessypris N, et al. Adiponectin and breast cancer risk. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:1102–1107. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Tworoger SS, Eliassen AH, Kelesidis T, et al. Plasma adiponectin concentrations and risk of incident breast cancer. J Clin Endo Metab. 2007;92:1510–1516. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Cust AE, Kaaks R, Friedenreich C, et al. Plasma adiponectin levels and endometrial cancer risk in pre- and post-menopausal women. J Clin Endo Met. 2007;92:255–263. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Miyoshi Y, Funahashi T, Kihara S, et al. Association of serum adiponectin levels with breast cancer risk. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:5699–5704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wei EK, Giovannucci E, Fuchs CS, Willett WC, Mantzoros CS. Low plasma adiponectin levels and risk of colorectal cancer in men:a prospective study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:1688–1694. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Dal Maso L, Augustin LS, Karalis A, et al. Circulating adiponectin and endometrial cancer risk. J Clin Endo Met. 2004;89:1160–1163. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Brakenhielm E, Veitonmaki N, Cao R, et al. Adiponectin-induced antiangiogenesis and antitumor activity involve caspase-mediated endothelial cell apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:2476–2481. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308671100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Housa D, Housova J, Vernerova Z, Haluzik M. Adipocytokines and Cancer. Physiol. Res. 2006;55:233–244. doi: 10.33549/physiolres.930848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Miyoshi Y, Funahashi T, Tanaka S, et al. High expression of leptin receptor mRNA in breast cancer tissue predicts poor prognosis for patients with high, but not low, serum leptin levels. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:1414. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ribatti D, Belloni AS, Nico B, Di Comite M, Crivellato E, Vacca A. Leptin-leptin receptor are involved in angiogenesis in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Peptides. 2008;29:1596–602. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2008.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Gonzalez RR, Leavis PC. A peptide derived from the human leptin molecule is a potent inhibitor of the leptin receptor function in rabbit endometrial cells. Endocrine. 2003;21:185. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:21:2:185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Gonzalez RR, Watters A, Xu Y, et al. Leptin-signaling inhibition results in efficient antitumor activity in estrogen receptor positive or negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2009;11:R36. doi: 10.1186/bcr2321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Surmacz E. Leptin and adiponectin:emerging therapeutic targets in breast cancer. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2013;18:321–332. doi: 10.1007/s10911-013-9302-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Nikolopoulos D, Theocharis S, Kouraklis G. Ghrelin’s role on gastrointestinal tract cancer. Surg Oncol. 2010;19:e2–e10. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Lanfranco F, Baldi M, Cassoni P, Bosco M, Ghe C, Muccioli G. Ghrelin and prostate cancer. Vitam Horm. 2008;77:301–324. doi: 10.1016/S0083-6729(06)77013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Lawnicka H, MeƗeń-Mucha G, Motylewska E, Mucha S, Stępień H. Modulation of ghrelin axis influences the growth of colonic and prostatic cancer cells in vitro. Pharmacol Rep. 2012;64:951–959. doi: 10.1016/s1734-1140(12)70890-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Chen BD, Zhao WC, Jia QA, et al. Effect of the GLP-1 analog exendin-4 and oxaliplatin on intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma cell line and mouse model. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:24293–24304. doi: 10.3390/ijms141224293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Zhao H, Wei R, Wang L, et al. Activation of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor inhibits growth and promotes apoptosis of human pancreatic cancer cells in a cAMP-dependent manner. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2014;306:E1431–EI441. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00017.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Nauck MA, Friedrich N. Do GLP-1-based therapies increase cancer risk? Diabetes Care. 2013;36(Suppl 2):S245–S252. doi: 10.2337/dcS13-2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Mathur A, Hernandez J, Shaheen F, et al. Preoperative computed tomography measurements of pancreatic steatosis and visceral fat:prognostic markers for dissemination and lethality of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. HPB (Oxford) 2011;13:404–410. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2011.00304.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Mathur A, Zyromski NJ, Pitt HA, et al. Pancreatic steatosis promotes dissemination and lethality of pancreatic cancer. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;208:989–994. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Muller C. Tumour-surrounding adipocytes are active players in breast cancer progression. Ann Endocrinol (Paris) 2013;74:108–110. doi: 10.1016/j.ando.2013.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Hasebe T, Mukai K, Tsuda H, Ochiai A. New prognostic histological parameter of invasive ductal carcinoma of the breast:clinicopathological significance of fibrotic focus. Pathol Int. 2000;50:263–272. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1827.2000.01035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Yamaguchi J, Ohtani H, Nakamura K, et al. Prognostic impact of marginal adipose tissue invasion in ductal carcinoma of the breast. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;130:382–388. doi: 10.1309/MX6KKA1UNJ1YG8VN. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Rio MC. The role of cancer-associated adipocytes (CAA) in the dynamic interaction between the tumor and the host. In: Mueller MM, Fusenig NE, editors. Tumor-Associated Fibroblasts and their Matrix. Vol. 4. Springer: Netherlands; 2011. pp. 111–123. [Google Scholar]

- 119.Manabe Y, Toda S, Miyazaki K, Sugihara H. Mature adipocytes, but not preadipocytes, promote the growth of breast carcinoma cells in collagen gel matrix culture through cancer-stromal cell interactions. J Pathol. 2003;201:221–228. doi: 10.1002/path.1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Amemori S, Ootani A, Aoki S, et al. Adipocytes and preadipocytes promote the proliferation of colon cancer cells in vitro. Am J Physiol Gastro Liver Physiol. 2007;292:G923–G929. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00145.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Battula VL, Chen Y, Cabreira Mda G, et al. Connective tissue growth factor regulates adipocyte differentiation of mesenchymal stromal cells and facilitates leukemia bone marrow engraftment. Blood. 2013;122:357–366. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-06-437988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Kaneko A, Satoh Y, Tokuda Y, Fujiyama C, Udo K, Uozumi J. Effects of adipocytes on the proliferation and differentiation of prostate cancer cells in a 3-D culture model. Int J Urol. 2010;17:369–376. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2010.02472.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Kushiro K, Chu RA, Verma A, Núñez NP. Adipocytes promote B16BL6 melanoma cell invasion and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Cancer Microenviron. 2012;5:73–82. doi: 10.1007/s12307-011-0087-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Liu E, Samad F, Mueller BM. Local adipocytes enable estrogen-dependent breast cancer growth:Role of leptin and aromatase. Adipocyte. 2013;2:165–169. doi: 10.4161/adip.23645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.White PB, True EM, Ziegler KM, et al. Insulin, leptin, and tumoral adipocytes promote murine pancreatic cancer growth. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:1888–1893. doi: 10.1007/s11605-010-1349-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Tokuda Y, Satoh Y, Fujiyama C, Toda S, Sugihara H, Masaki Z. Prostate cancer cell growth is modulated by adipocyte-cancer cell interaction. BJU Int. 2003;91:716–720. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2003.04218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Zhang Y, Daquinag A, Traktuev DO, et al. White adipose tissue cells are recruited by experimental tumors and promote cancer progression in mouse models. Cancer Res. 2009;69:5259–5266. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Nieman KM, Kenny HA, Penicka CV, et al. Adipocytes promote ovarian cancer metastasis and provide energy for rapid tumor growth. Nat Med. 2011;17:1498–1503. doi: 10.1038/nm.2492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Ehsanipour EA, Sheng X, Behan JW, et al. Adipocytes cause leukemia cell resistance to L-asparaginase via release of glutamine. Cancer Res. 2013;73:2998–3006. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-4402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Bochet L, Lehuédé C, Dauvillier S, et al. Adipocyte-derived fibroblasts promote tumor progression and contribute to the desmoplastic reaction in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2013;73:5657–5668. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-0530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Jotzu C, Alt E, Welte G, et al. Adipose tissue-derived stem cells differentiate into carcinoma-associated fibroblast-like cells under the influence of tumor-derived factors. Cell Oncol. 2011;34:55–67. doi: 10.1007/s13402-011-0012-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Gallagher EJ, LeRoith D. Diabetes, antihyperglycemic medications and cancer risk:smoke or fire? Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2013;20:485–494. doi: 10.1097/01.med.0000433065.16918.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Sheng H, Li P, Chen X, Liu B, Zhu Z, Cao W. Omega-3 PUFAs induce apoptosis of gastric cancer cells via ADORA1. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2014;19:854–861. doi: 10.2741/4252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Xu Y, Qian SY. Anti-cancer activities of ω-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids. Biomed J. 2014;37:112–119. doi: 10.4103/2319-4170.131378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Zheng H, Tang H, Liu M, et al. Inhibition of Endometrial Cancer by n-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids in Preclinical Models. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2014;7:824–834. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-13-0378-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Takino J, Yamagishi S, Takeuchi M. Cancer malignancy is enhanced by glyceraldehyde-derived advanced glycation end-products. J Oncol. 2010;2010:739852. doi: 10.1155/2010/739852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Ley RE. Obesity and the human microbiome. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2010;26:5–11. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e328333d751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Amar J, Burcelin R, Ruidavets JB, et al. Energy intake is associated with endotoxemia in apparently healthy men. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87:1219–1223. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.5.1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Cani PD, Amar J, Iglesias MA, et al. Metabolic endotoxemia initiates obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2007;56:1761–1772. doi: 10.2337/db06-1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Bellacosa A, Kumar CC, Di Cristofano A, Testa JR. Activation of AKT kinases in cancer:implications for therapeutic targeting. Adv Cancer Res. 2005;94:29–86. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(05)94002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Malek M, Aghili R, Emami Z, Khamseh ME. Risk of cancer in diabetes:the effect of metformin. ISRN Endocrinol. 2013;2013:636927. doi: 10.1155/2013/636927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Thakkar B, Aronis KN, Vamvini MT, Shields K, Mantzoros CS. Metformin and sulfonylureas in relation to cancer risk in type II diabetes patients:a meta-analysis using primary data of published studies. Metabolism. 2013;62:922–934. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2013.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Dillon LM, Miller TW. Therapeutic targeting of cancers with loss of PTEN function. Curr Drug Targets. 2014;15:65–79. doi: 10.2174/1389450114666140106100909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Sjostrom L, Narbro K, Sjostrom CD, et al. Effects of bariatric surgery on mortality in Swedish obese subjects. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:741–752. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Adams TD, Stroup AM, Gress RE, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality after gastric bypass surgery. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009;17:796–802. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Birks S, Peeters A, Backholer K, O’Brien P, Brown W. A systematic review of the impact of weight loss on cancer incidence and mortality. Obes Rev. 2012;13:868–891. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2012.01010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Byers T, Sedjo RL. Does intentional weight loss reduce cancer risk? Diabetes Obes Metab. 2011;13:1063–1072. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2011.01464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Sjostrom L, Gummesson A, Sjostrom CD, et al. Effects of bariatric surgery on cancer incidence in obese patients in Sweden (Swedish Obese Subjects Study):a prospective, controlled intervention trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:653–662. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70159-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Ward KK, Roncancio AM, Shah NR, et al. Bariatric surgery decreases the risk of uterine malignancy. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;133:63–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Stylopoulos N, Hoppin AG, Kaplan LM. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass enhances energy expenditure and extends lifespan in diet-induced obese rats. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009;17:1839–1847. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Peng Y, Rideout DA, Rakita SS, Gower WR, Jr., You M, Murr MM. Does LKB1 mediate activation of hepatic AMP-protein kinase (AMPK) and sirtuin1 (SIRT1) after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in obese rats? J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:221–228. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-1102-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Faria SL, Faria OP, Buffington C, de Almeida Cardeal M, Rodrigues de Gouvêa H. Energy expenditure before and after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2012;22:1450–1455. doi: 10.1007/s11695-012-0672-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Faria SL, Faria OP, Cardeal Mde A, Ito MK, Buffington C. Diet-induced thermogenesis and respiratory quotient after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery: a prospective study. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2014;10:138–143. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2013.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]