Abstract

Behavioral flexibility is known to be mediated by corticostriatal systems and to involve several major neurotransmitter signaling pathways. The current study investigated the effects of inactivation of glutamatergic N-methyl-D-aspartate-(NMDA) receptor signaling in the dorsal striatum on behavioral flexibility in mice. NMDA-receptor inactivation was achieved by virus-mediated inactivation of the Grin1 gene, which encodes the essential NR1 subunit of NMDA receptors. To assess behavioral flexibility, we used a water U-maze paradigm in which mice had to shift from an initially acquired rule to a new rule (strategy shifting) or had to reverse an initially learned rule (reversal learning). Inactivation of NMDA-receptors in all neurons of the dorsal striatum did not affect learning of the initial rule or reversal learning, but impaired shifting from one strategy to another. Strategy shifting was also compromised when NMDA-receptors were inactivated only in dynorphin-expressing neurons in the dorsal striatum, which represent the direct pathway. These data suggest that NMDA-receptor mediated synaptic plasticity in the dorsal striatum contributes to strategy shifting and that striatal projection neurons of the direct pathway are particularly relevant for this process.

Keywords: Medium spiny neuron, direct pathway, executive function, learning, plasticity, knockout

INTRODUCTION

The striatum is a key component of the basal ganglia, a sub-cortical feedback system, that integrates excitatory glutamatergic cortical, thalamic, amygdaloid and hippocampal inputs with modulatory dopaminergic input from the ventral midbrain (Alexander et al., 1986, Voorn et al., 2004). Within the striatum, the excitatory glutamatergic input activates α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA), N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA), and metabotropic glutamate receptors on two distinct classes of medium spiny neurons (MSNs) that relay these inputs to other basal ganglia components that ultimately project back to the cortex (Albin et al., 1992, Gerfen, 1992).

Cortico-striatal basal ganglia circuits have been shown to be relevant for various aspects of motor and cognitive function, which are compromised by neurodegenerative diseases like Parkinson’s disease (PD) and Huntington’s disease (HD) as well as by various psychiatric conditions (Samii et al., 2004, Leverenz et al., 2009, Simpson et al., 2010, Dorsey et al., 2013). One important cognitive behavior that is adversely affected by PD, HD and some of the psychiatric conditions is cognitive flexibility—the ability to disengage from previously learned behavior and adopt a new behavioral response (Lawrence et al., 1999, Buckner, 2004, Lima et al., 2008). Additional experimental support for an involvement of the striatum in mediating cognitive flexibility is provided by animal studies using either MSN lesions, transient pharmacological blockade of MSN activity, or inactivation of dopaminergic and cholinergic signaling in the striatum (Ragozzino et al., 2002, Floresco et al., 2006, Braun and Hauber, 2011, Darvas and Palmiter, 2011, Wang et al., 2013, Darvas et al., 2014). While it has been shown that acute pharmacological blockade of NMDA glutamate receptors in the dorsal striatum impairs one form of cognitive flexibility, i.e., response reversal learning (Palencia and Ragozzino, 2004), it remains unclear whether the effects of transient NMDA receptor blockade also extend to conditions of chronic NMDA receptor signaling loss and whether strategy-shifting, which is another form of cognitive flexibility, also requires NMDA-receptor signaling in the dorsal striatum. Furthermore, NMDA receptor blockade does not allow differentiation between effects of signaling in dynorphin-expressing MSNs of the direct pathway or in enkephalin-expressing MSNs of the indirect pathway on mediating cognitive flexibility.

Genetic inactivation of functional NMDA receptors by inactivation of the Grin1 gene is an alternative way to evaluate the role of MSN glutamatergic signaling in cognitive flexibility that is complementary to pharmacological approaches. Previous studies showed that inactivation of the Grin1 gene in all MSNs has a severe effect on all forms of task learning examined (Dang et al., 2006; Beutler et al., 2011). The combination of Cre-recombinase-dependent Grin1 mutations with the delivery of viral vectors that express Cre allows for specific and permanent targeting of discrete brain regions (Parker et al., 2011). To investigate contributions of chronic reduction of NMDA receptor signaling to cognitive flexibility, we injected an adeno-associated virus 1 (AAV1) expressing Cre into the dorsal striatum of mice with conditional Grin1 alleles (Grin1lox/lox mice; (Tsien et al., 1996). This approach targets all cell populations resident in the injected area that express the Grin1 gene. To examine specific contributions of direct pathway MSNs, we injected an adeno-associated virus 1 (AAV1) with a dynorphin promoter driving Cre recombinase (AAV1-Pdyn-Cre) that restricts Cre expression to the direct pathway-associated dynorphin-expressing cells. Following the viral injections, mice were tested in a cognitive flexibility test that requires animals to shift from an egocentric response strategy to a cue-dependent response strategy (Darvas and Palmiter, 2011).

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Animals

All experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Washington. Grin1lox mice were obtained from Dr. Joseph Tsien (Tsien et al., 1996) and maintained on a C57Bl/6 genetic background. Rosa26fstdTomato mice were generated as described (Madisen et al., 2010), crossed with Grin1lox mice and maintained on a C57Bl/6 genetic background. All mice were housed in groups of 3–5 animals under a 12-h, light-dark cycle (6AM-6PM) in a temperature-controlled environment with food and water available ad libitum. Grin1lox/+ and Grin1lox/lox mice used for viral injections were generated by crossing Grin1lox/+ and Grin1lox/lox animals.

Viral injections

Two different viral preparations, both pseudotyped adeno-associated virus 1 (AAV1), were used. AAV1 Cre-recombinase green fluorescent protein (AAV1-CBA-CreGFP) virus contains a cytomegalovirus-chicken-beta-actin promoter driving expression of an open reading frame encoding Cre-recombinase fused to enhanced GFP and an N-terminal nuclear localization signal. It was generated as described (Rabinowitz et al., 2002, Quintana et al., 2012) and titered at 1012 particles per ml. The other virus contains a rat-prodynorphin promoter driving expression of Cre-recombinase (AAV1-Pdyn-Cre). AAV1-Pdyn-Cre virus was prepared in HEK293 cells with AAV-1 serotype, purified by CsCl gradient centrifugation, recovered in sterile HBSS and titered at 1012 particles per ml. Bilateral injections of 0.5 µl of AAV1-Cre-GFP into the dorsal striatum (y = 0.5 mm anterior to Bregma, x = ± 1.75 mm lateral to midline, z = 3 mm ventral from the skull surface) were performed on anesthetized (isoflurane) 2- to 3-month-old male Grin1lox/+ (referred to as sham controls) and Grin1lox/lox (referred to as viral knock-out, vKO) mice. The same procedure and coordinates were used for AAV1-Pdyn-Cre injections into the dorsal striatum of male Grin1lox/+/Rosa26fstdTomato (sham control) and male Grin1lox/lox/Rosa26fstdTomato (Pdyn-KO) mice. Rosa26fstdTomato mice were used to enable easy identification of cells that have virus-mediated (AAV1-Pdyn-Cre) expression of Cre. All animals were given 2–3 weeks of recovery after the surgeries before behavioral testing began. We injected 17 sham and 14 Grin1lox/lox mice with AAV1-CBA-CreGFP, and 8 sham and 8 Grin1lox/lox/Rosa26fstdTomato mice with AAV1-Pdyn-Cre. Our decision to use Grin1lox/+ mice as sham controls was based on previous work showing that similar viral injections into Grin1lox/+ mice had no impact on learning (Parker et al., 2011), and on data showing unaltered electrophysiological properties of neurons in mice that are heterozygous for deletion of the Grin1 gene (Forrest et al., 1994). However, we also included an untreated group of wild-type animals (n = 7) in our behavioral analyses to control for potential effects that might be due to a possible loss of function in virus-treated Grin1lox/+ mice.

Immunohistochemistry

After transcardial perfusion (4 % paraformaldehyde) of deeply anesthetized mice, brains were removed, cryo-protected in 30 % sucrose, frozen in isopentane and sectioned (30 µm) on a cryostat. Sections were then stored free-floating, at 4°C and protected from light. Fluorescence from GFP and TdTomato expression was detected without antibody staining. Enkephalin was detected by using a rabbit anti methionine-enkephalin (1:100; Immunostar #20065) antibody in conjunction with an Alexa Fluor 488 labeled IgG secondary antibody (1:200; Jackson ImmunoResearch). Tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) was detected by using a rabbit anti-TH (1:2,000; Millipore #AB152) antibody in conjunction with an Alexa Fluor 488 labeled IgG secondary antibody (1:200; Jackson ImmunoResearch).

Western blot

Dorsal and ventral striatum was isolated (1-mm diameter tissue punches) from AAV1-Cre-GFP injected sham and vKO mice, immediately placed in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −70°C. Samples were thawed into RIPA homogenization buffer (Sigma-Aldrich) containing Complete Mini protease inhibitors (Roche Applied Science), sonicated, and centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 10 min. The supernatant was collected and assayed for protein concentration using a bicinchoninic assay (Thermo Scientific). Total protein (45 µg) was electrophoresed on 10 % polyacrylamide gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Blots were blocked overnight and probed with monoclonal antibodies to β-actin (1:20,000; Abcam #ab6276) and the NR1 subunit of the NMDA receptor (1:10,000, Millipore #MAB363). Blots were then washed and incubated with a horse radish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:10,000; Jackson ImmunoResearch) and visualized using the Pierce ECL system (Thermo Scientific). Densities of detected NR1 and β-actin bands were measured using ImageJ (NIH) and we calculated for each sample a relative NR1 expression-score dividing the NR1 band-density by the β-actin band-density.

Behavioral studies

All behavior studies were performed in a blinded fashion. The genotypes of all sham and vKO mice were coded before viral injections and maintained coded until completion of behavioral experiments.

Spontaneous motor activity in a novel environment was assessed using static mouse cages (37.2 cm D × 23.4 cm W × 14 cm H) with 16 photo cells per side (Columbus Instruments) and was measured in ambulations (2 consecutive beam interruptions) summated over 5-min intervals. Activity was measured during an overall recording period of 1 h.

Motor skill learning and coordination was examined using an accelerating (4–40 rpm over the course of 5 min) rotating rotarod (Columbus Instruments). The latency to fall from the rotarod apparatus was recorded over three consecutive days with 4 trials per day and an inter-trial interval of 10 min.

Egocentric learning, strategy shifting, cue-dependent learning and reversal learning were measured using a U-maze water escape task (Darvas and Palmiter, 2009, 2011, Darvas et al., 2014). The maze consisted of three parts, a gray stem that led to two opposite arms (one colored white and one black), at the end of which an escape platform could be placed. The black and white arms are curved and bent back so that it is not possible to view the end of each arm from the junction with the stem. Throughout all trials, only one escape platform was present in the maze. We used two rules for the placement of the escape platform: (1) the platform could always be reached by making a turn towards one direction (e.g., left, turn-based strategy) or (2) the platform could always be reached by entering the arm of the same color (e.g., black, cue-based strategy). Mice remained in the maze until a correct decision was made to ensure an equal number of reinforced responses. We alternated the right-left orientations of the white and black arms of the maze daily in a non-repetitive, pseudo-random sequence so that either arm was equally located on both sides of the maze during the entire session. Each training day consisted of 10 trials with an inter-trial interval of 3–5 min during which mice were allowed to get warm on a heating pad. For each training day, the percentage of correct trials was calculated. A trial was scored as correct if the animal only entered the arm of the maze where the platform was located. The percentage of correct trials was calculated as the average of correct trials over all 10 trials within a training day. We used two different training procedures that were always performed with different groups of water-maze naïve mice. The first procedure consisted of three training days with a turn-based strategy (egocentric learning) followed by five training days with a cue-based strategy (strategy shift). The second procedure consisted of four training days with one color cue-based strategy (cue-dependent learning) followed by four days during which mice had to learn that the escape platform was now located at the end of the arm opposite to the arm that was used during cue-dependent learning (reversal learning). We have previously shown that turn-reversal learning in the U-maze water escape task is not affected by severe loss of dopamine signaling in the dorsal striatum and we therefore chose to use a cue-reversal procedure for the current experiment (Darvas and Palmiter, 2011). For egocentric learning, one half of all mice was randomly assigned to learn a left turn and the other half to learn a right turn. For strategy shifting and also for cue-dependent learning, one half of all mice was randomly assigned to learn that the escape platform was at the end of the black arm and the other half had to learn that the escape platform was at the end of the white arm.

Statistical analysis

All behaviour data analyses used standard repeated-measures analysis of variance together with Bonferroni’s post-hoc pair-wise comparison when appropriate. Western-blot protein expression data were analysed using Student’s t-test. All data are presented as arithmetic mean and shown together with their respective standard error of mean. Significance was reported when p < 0.05.

Results

Reduction of NR1 expression in the striatum with AAV1-CBA-CreGFP

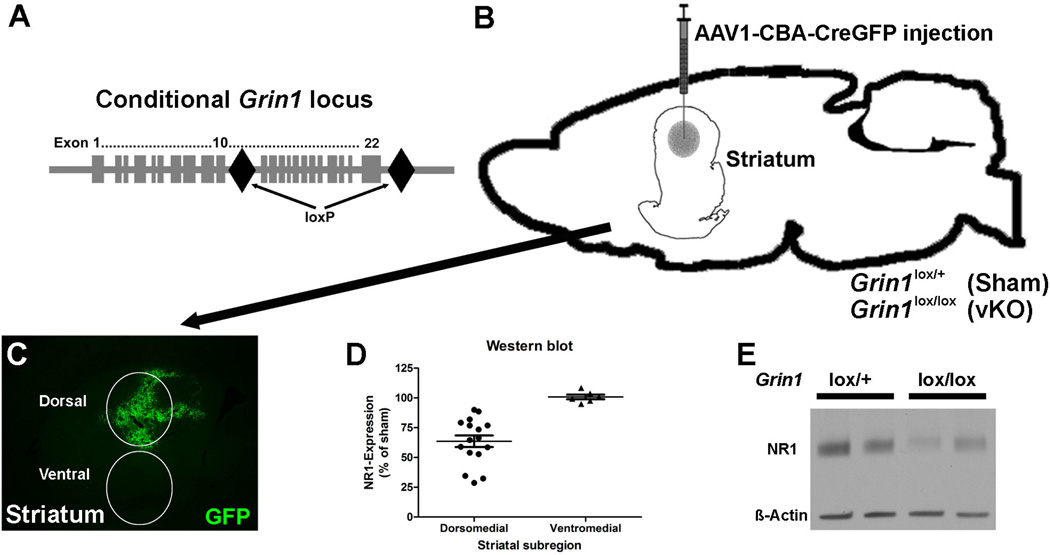

To examine the effects of chronic partial NMDA-receptor inactivation in the dorsal striatum on strategy shifting and reversal learning, we inactivated the Grin1 gene in Grin1lox/lox mice by bilaterally injecting AAV1-CBA-CreGFP into the dorsal striatum (Fig. 1A, B). Visualization of GFP fluorescence confirmed correct injection site placement within the dorsal striatum (Fig. 1C). Quantitative western blot analysis of NR1 expression in AAV1-CBA-CreGFP injected (vKO) and sham control mice revealed that vKO mice had 35 % less NR1 expression than sham control mice in the dorsal striatum (p < 0.01) and unchanged NR1 expression in the ventral striatum (Fig. 1D, E).

Figure 1.

Targeting of Grin1 expression in the dorsal striatum. (A) Schematic representation showing the position of loxP sites inserted into the Grin1 locus of Grin1lox mice. (B) Illustration of targeted area and needle placement for AAV1-CBA-CreGFP injections into Grin1lox/+ (sham) and Grin1lox/lox (viral knock-out, vKO) mice. (C) Coronal striatal tissue section showing the typical location of area injected with AAV1-CBA-CreGFP. Virus-mediated expression of GFP is shown as green fluorescence. White circles show the locations from which tissue was obtained for NR1 protein level analysis. (D) Quantitative western-blot analysis of NR1 protein levels in the dorsal and ventral striatum of Grin1lox/lox mice (dorsal striatum n = 12 and ventral striatum n = 6) that were injected with AAV1-CBA-CreGFP. Protein levels are shown as percentage of sham control animals (dorsal striatum n = 7 and ventral striatum n = 7). (E) Representative western-blot analysis of NR1 and beta-actin protein in virally injected Grin1lox/+ and Grin1lox/lox mice. Data are shown as mean ± standard error of mean, ** p < 0.01.

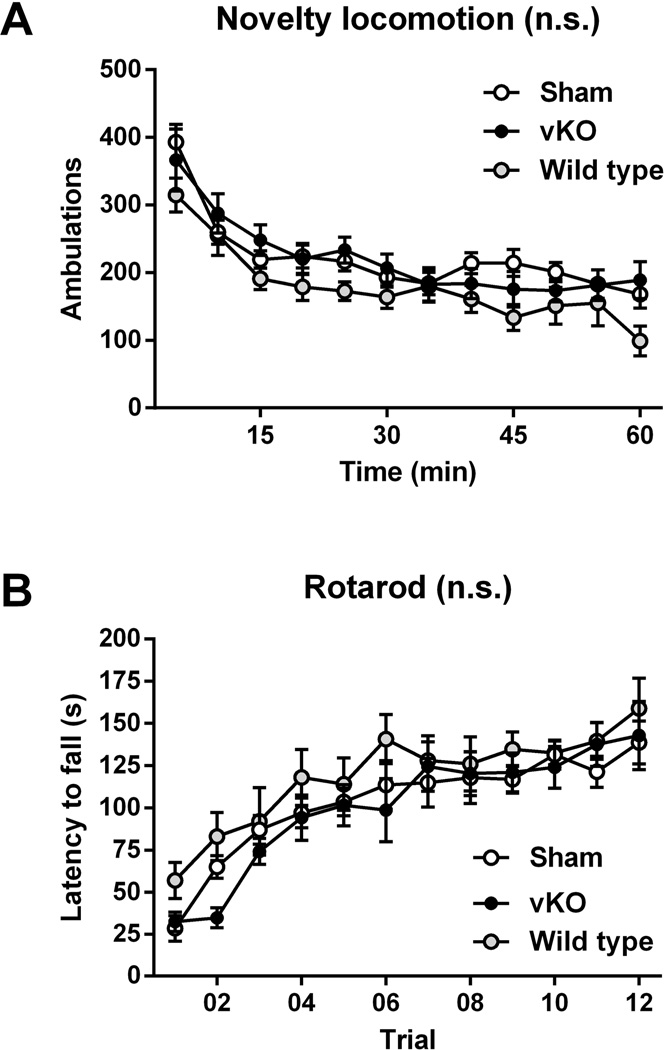

Reduction of NR1 expression in the striatum of vKO mice does not alter exploratory behavior or motor learning

To identify potential deficits in exploratory behavior or motor function, we examined novelty-induced exploration and motor skill learning in sham and vKO mice. When placed into a novel environment, sham, vKO and wild-type mice displayed the same degree of exploratory behavior (Fig. 2A) as indicated by repeated-measures (RM) two-way ANOVA of ambulations, which showed significant effects of time (F11, 297 = 35.24, p < 0.01), but not of group (F2, 27 = 1.646, p > 0.05) or of time-group interaction (F22, 297 = 1.131, p > 0.05). Motor learning on the rotating rotarod was also similar in sham, vKO and wild-type mice (Fig. 2B). RM two-way ANOVA of latencies to fall from the rotating rod only revealed significant effects of trial number (F11, 209 = 37.10, p < 0.01), but not of group (F2, 19 = 1.02, p > 0.05) or trial-number group interaction (F22, 209 = 0.94, p > 0.05). We conclude that the reduction in NR1 expression in vKO mice did not affect motor exploratory behavior or motor learning. Sham and wild-type mice had equal exploratory behavior and motor learning.

Figure 2.

Motor and exploratory behavior. (A) Spontaneous locomotor response (ambulations during 60-min exposure) to novelty by sham (n = 12), vKO (n = 11) and wild-type mice (n = 7). (B) Motor learning and coordination during 12 trials in the rotarod test by sham (n = 7), vKO (n = 8) and wild-type mice (n = 7). Statistical significance of genotype effects (repeated-measure two-way analysis of variance) are shown in the headings of each panel. Data are shown as mean ± standard error of mean, n.s., p > 0.05.

Strategy-shifting behavior, but not reversal learning is impaired after partial reduction of NR1 expression in the striatum of vKO mice

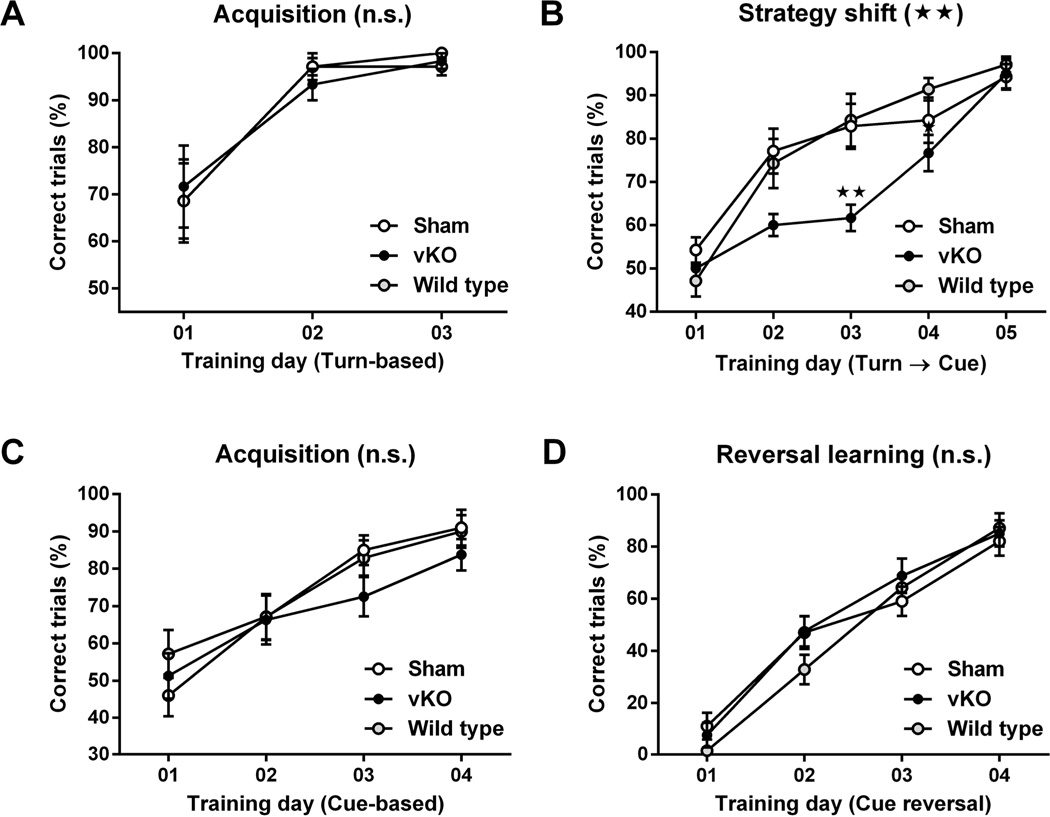

To assess the contributions of NMDA-receptor mediated signaling in the dorsal striatum to cognitive flexibility, we tested two separate groups of sham control and vKO mice using a strategy-shifting procedure (shift from egocentric to cue-dependent strategy) and a reversal-learning procedure (reversal of a cue-dependent strategy). During the first phase of the strategy-shifting task, sham, vKO and wild-type mice learned a turn-based strategy to escape from the water U-maze equally well (Fig 3A). RM two-way ANOVA of the percentages of correct trials per training day of the turn-based escape condition confirmed a significant effect of training day (F2, 34 = 33.52, p < 0.01), but not of group (F2, 17 = 0.02, p > 0.05) or of training-day group interaction (F4, 34 = 0.20, p > 0.05).

Figure 3.

Strategy-shift and cue-reversal learning in the water U-maze. (A, B) For strategy-shift learning, sham (n = 8), vKO (n = 6) and wild-type mice (n = 7) were first trained to acquire a turn-based water-escape strategy (A), and then had to shift from that strategy to a new cue-based water-escape strategy (B). (C, D) For reversal learning, a new cohort of sham (n = 10), vKO mice (n = 8) and wild-type (n = 7) mice were first trained to acquire a water-escape strategy based on one of the two intra-maze cues (C), and then had to reverse from that strategy to a new water-escape strategy based on the other intra-maze cue (D). Statistical significance of genotype effects (repeated-measure two-way analysis of variance) are shown in the headings of each panel. Significant differences obtained from post-hoc pairwise comparisons are denoted next to the respective data points. Data are shown as mean ± standard error of mean; n.s., p > 0.05, **, p < 0.01.

When the rules for the water-escape strategy were then changed so that now a cue-based strategy had to be adopted for successful water escape, vKO mice performed worse than sham control or wild-type mice (Fig 3B). RM two-way ANOVA of the percentages of correct trials per training day of the strategy-shift condition revealed significant effects of training day (F4 68 = 80.79, p < 0.01), group (F2, 17 = 3.78, p < 0.05) and of training-day group interaction (F8, 68 = 3.40, p < 0.01). Bonferroni’s post-hoc pair-wise comparison confirmed that vKO had significantly less correct trials than sham control mice on strategy-shift days 2 (p < 0.05) and 3 (p < 0.01), and that sham control mice were indistinguishable from wild-type mice in their performance (p > 0.05).

In contrast, neither acquisition nor reversal of a cue-based water escape strategy was impaired in vKO mice (Fig. 3C, D). RM two-way ANOVA of the percentages of correct trials per training day of the initial cue-based escape condition confirmed a significant effect of training day (F3, 66 = 34.98, p < 0.01), but not of group (F2, 22 = 0.60, p > 0.05) or of training-day group interaction (F6, 66 = 0.91, p > 0.05). Similarly, RM two-way ANOVA of the percentages of correct trials per training day of the cue-reversal condition revealed only significant effects of training day (F3 66 = 134.6, p < 0.01), but not of group- (F2, 22 = 0.58, p > 0.05) or of training-day group interaction (F6, 66 = 1.21, p > 0.05).

Taken together, we conclude that successful strategy shifting is significantly delayed, but not completely absent in vKO mice. This impairment cannot be explained by an overall deficiency in learning cue-based water escape strategies, because this type of learning was intact in vKO mice. Sham control and wild-type mice performed equally well in both water-maze tests.

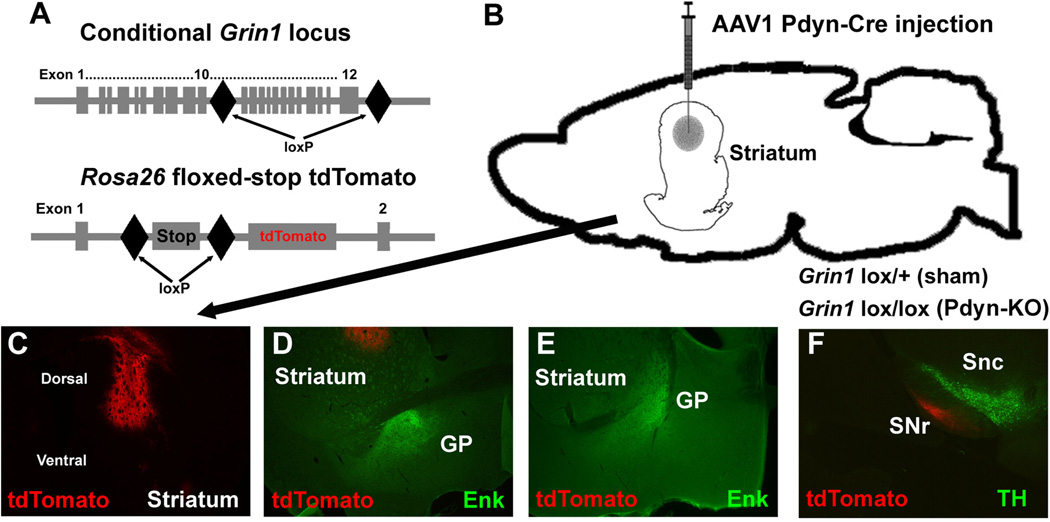

Targeting of dynorphin-expressing cells in the dorsal striatum with AAV1-Pdyn-Cre

To identify a sub-population of NMDA-receptor expressing cells in the dorsal striatum that contributes to the deficit in strategy-shifting behavior of vKO mice, we cloned a Cre recombinase under the control of a Prodynorphin gene (Pdyn) promoter that allows restricted expression in the dynorphin-expressing neurons, which are the dopamine D1 receptor population of striatal neurons that constitute the ‘direct pathway.’ We used the same coordinates in dorsal striatum as in the previous experiment and injected AAV1-Pdyn-Cre into sham control and Grin1lox/lox mice that were also carrying one Rosa26fstdTomato allele (Fig. 4A, B). The Rosa26fstdTomato gene is transcriptionally inactive, but in the presence of Cre recombinase the floxed-stop cassette is removed and the red-fluorescent reporter tdTomato is expressed (Shaner et al., 2005, Madisen et al., 2010). Analysis of AAV1-Pdyn-Cre-mediated tdTomato expression in Rosa26fstdTomato mice confirmed correct injection site placement within the dorsal striatum (Fig. 4C). Importantly, expression of tdTomato red fluorescence was not present in the ventral pallidum (Fig. 4D) or in the lateral globus pallidus (Fig. 4E), both of which are projection fields of enkephalin-immunoreactive striatal projections neurons of the indirect pathway (Gerfen, 1992). However, we observed strong expression of tdTomato in the substantia nigra reticulata (SNr) adjacent to tyrosine hydroxylase immunoreactive dopaminergic neurons of the ventral midbrain (Fig. 4F), which is consistent with expression of Pdyn-Cre in striatal projection neurons of the direct pathway (Gerfen, 1992). The enkephalin-specific antibody we used did not result in detectable staining signals within the striatum (Fig. 4 D, E). Therefore, we could not quantify how many, if any, cell bodies of indirect pathway neurons were infected by AAV1-Pdyn-Cre. However, the strong induction of tdTomato red fluorescence in the SNr and the absence of expression in the ventral pallidum/lateral globus pallidus indicate that AAV1-Pdyn-Cre did not induce Cre-dependent changes of gene expression in indirect pathway neurons.

Figure 4.

Targeting of Grin1 expression in dynorphin-expressing cells of the dorsal striatum. (A) Schematic representation showing the position of loxP sites inserted into the Grin1 locus of Grin1lox mice (top) and the arrangement of the Rosa26 floxed-stop tdTomato locus (bottom). (B) Illustration of targeted area and needle placement for AAV1 Dyn-Cre injections into Grin1lox/+ (sham) and Grin1lox/lox (Pdyn-KO) mice. (C) Coronal striatal tissue section showing the typical location of area injected with AAV1 Dyn-Cre. Virus-mediated expression of tdTomato is shown as red fluorescence. (D) Coronal tissue section of striatum and ventral pallidum, which is an anterior part of the globus pallidus (GP). Projections of indirect pathway MSNs to the GP are revealed by immune labeling with an anti-enkephalin antibody (shown as green fluorescence) and AAV1 Dyn-Cre mediated expression of tdTomato in the anterior striatum is shown as red fluorescence. (E) Coronal tissue section of striatum and lateral pallidum, which is a posterior part of the GP. Projections of indirect pathway MSNs to the GP are revealed by immune labeling with an anti-enkephalin antibody (shown as green fluorescence) and AAV1 Dyn-Cre mediated expression of tdTomato is shown as red fluorescence (absent in posterior striatum). (F) Coronal tissue section of the midbrain substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc) and substantia nigra pars reticulata (SNr). Dopaminergic neurons in the SNc are labeled with an anti-tyrosine hydroxylase antibody and AAV1 Dyn-Cre mediated expression of tdTomato in the SNr is shown as red fluorescence.

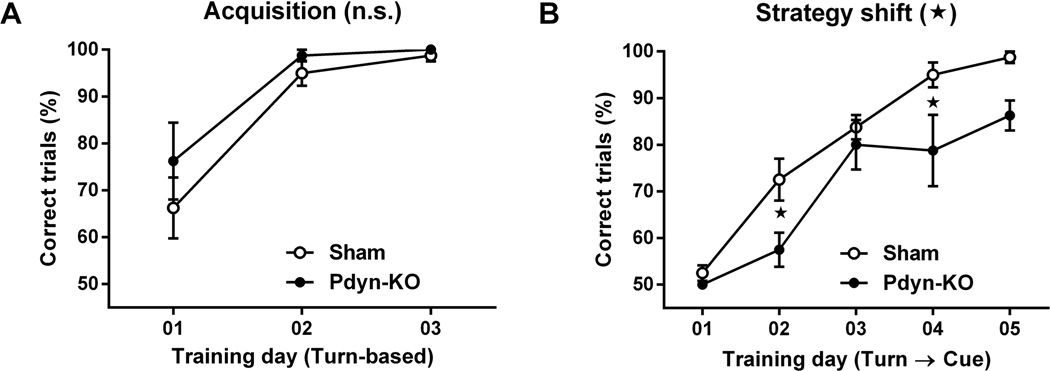

Selective reduction of NR1 expression in dynorphin-expressing cells in the dorsal striatum also impairs strategy-shifting behavior

To assess the specific contributions of NMDA-receptor mediated signaling in dynorphin expressing cells in the dorsal striatum to cognitive flexibility, we tested sham control and Pdyn-KO mice using our strategy-shifting procedure. Sham control and Pdyn-KO mice learned the turn-based strategy to escape from the water U-maze equally well (Fig 5A). RM two-way ANOVA of the percentages of correct trials per training day of the turn-based escape condition confirmed a significant effect of training day (F2, 28 = 26.16, p < 0.01), but not of group (F1, 14 = 1.61, p > 0.05) or of training-day group interaction (F2, 28 = 0.55, p > 0.05). However, when the rules for the water-escape strategy where shifted to a cue-based strategy, Pdyn-KO mice performed worse than sham control mice (Fig 5B). RM two-way ANOVA of the percentages of correct trials per training day of the strategy-shift condition revealed significant effects of training day (F4 56 = 42.87, p < 0.01), group (F1, 14 = 6.59, p < 0.05), but not of training-day group interaction (F4, 56 = 1.29, p > 0.05). Bonferroni’s post-hoc pair-wise comparison confirmed that Pdyn-KO mice had significantly less correct trials than sham control mice on strategy-shift days 2 (p < 0.05) and 4 (p < 0.05).

Figure 5.

Strategy-shift learning in the water U-maze by sham (n = 8) and vKO (Pdyn-KO) mice (n = 8). (A) Acquisition of turn-based water-escape strategy. (B) Shift from turn-based to a new cue-based water-escape strategy. Statistical significance of genotype effects (repeated-measure two-way analysis of variance) are shown in the headings of each panel. Significant differences obtained from post-hoc pairwise comparisons are denoted next to the respective data points. Data are shown as mean ± standard error of mean; n.s., p > 0.05, *, p < 0.05.

We conclude that reduction of NMDA-receptor expression in dynorphin-expressing cells of Pdyn-KO mice is sufficient to cause deficits in strategy-shifting behavior. This suggests that at least a part of the NMDA-receptor mediated signaling contributing to cognitive flexibility is required in striato-nigral projections of the direct pathway.

Discussion

We investigated whether glutamatergic NMDA-receptor signaling in the dorsal striatum is involved in mediating cognitive flexibility, specifically assessing whether specific contributions were made to this behavior by NMDA-receptor signaling in striatal direct pathway MSNs. We generated mice with partial reduction of NR1 expression in all cells within the dorsal striatum using viral Cre-mediated deletion of conditional Grin1 alleles and we generated mice in which deletion of Grin1 alleles was targeted specifically to dynorphin-expressing cells in the dorsal striatum. To verify that partial reduction of NR1 expression does not cause motor or exploration deficits that might interfere with performance of cognitive behavior, we used procedures that measure motor coordination and novelty exploration along with our tests for cognitive flexibility. Like mice with a severe lack of striatal NR1 expression (Beutler et al., 2011), our partial reduction of NR1 expression did not change novelty-induced locomotor activity. In contrast, while mice with severe loss of striatal NR1 expression exhibit drastic deficits in motor learning (Dang et al., 2006, Beutler et al., 2011), mice with partial NR1 loss had no motor-learning impairment. Because results from lesioning studies have demonstrated that the lateral dorsal striatum is particularly involved in the acquisition of motor skills (Dunnett and Iversen, 1982, Pisa and Cyr, 1990, Fricker et al., 1996), we conclude that the lack of motor-learning impairment in our mice indicates that our viral injection strategy did not significantly affect the lateral parts of the dorsal striatum. The relatively moderate loss of NR1 expression in the dorsal striatum did, however, impair cognitive flexibility in our strategy-shifting paradigm. Similar to animals with either reduced cholinergic or dopaminergic signaling in the dorsal striatum or with pharmacologically inactivated MSNs in the dorsal striatum (Ragozzino et al., 2002, Darvas and Palmiter, 2011, Wang et al., 2013, Darvas et al., 2014), partial loss of NR1 expression caused a strategy-shifting impairment that was overcome with additional training sessions. Interestingly, reduction of NR1 expression did not alter reversal learning, a behavior that has been shown to be impaired, in a dose-dependent manner, by infusion of NMDA-receptor antagonists into the dorsal striatum (Palencia and Ragozzino, 2004). Although it is difficult to compare effects of drug infusion techniques with virus-mediated gene inactivation, we suggest that the genetic inactivation was less severe than the pharmacological blockade that has been shown to impair reversal learning in rats (Palencia and Ragozzino, 2004). However, it is important to note that two major differences between our strategy-shift procedure and the behavioral procedures used in most pharmacological studies are our use of a correction procedure and our use of an aversively-motivated task instead of an appetitive task. We decided to use a correction procedure because we wanted to avoid reinforcing wrong decisions by removing animals from the maze after they made a wrong turn. Instead we allowed the animals to correct their behavior, so that all animals had the same number of water-escapes resulting from their own decisions. Our current findings together with previous findings from our lab and others, suggest that cognitive flexibility requires integration of signaling that involves several brain regions, including the prefrontal cortex (Robbins, 2005, Floresco and Magyar, 2006) as well as ventral and dorsal striatum (Floresco et al., 2006). Cognitive flexibility depends on several neurotransmitter and neuromodulator systems, including glutamatergic, cholinergic (Ragozzino et al., 2009, Wang et al., 2013), serotonergic (Clarke et al., 2005), and dopaminergic signaling (De Steno and Schmauss, 2009, Darvas et al., 2014). We believe that our results suggest that NMDR-mediated plasticity contributes to strategy shifting. Further proof from electrophysiological recordings will be required to fully support this hypothesis.

Interestingly, we were able to demonstrate that targeted loss of NMDA-receptor signaling in dynorphin-expressing cells of the dorsal striatum also caused a deficit in cognitive flexibility, suggesting that MSNs of the direct pathway are involved in this process. We have previously shown that a rather moderate (no more than 70 %) reduction of dopamine signaling in the dorsal striatum impairs cognitive flexibility (Darvas et al., 2014). Although partial dopamine depletion of this magnitude failed to elicit a reduction in tonic dopamine release in the striatum (Abercrombie et al., 1990, Robinson et al., 1994), it compromises phasic dopamine release (Howard et al., 2011). Dynorphin-expressing direct-pathway MSNs in the dorsal striatum express dopamine D1 receptors that are characterized by a low ligand-binding affinity state (Richfield et al., 1989) and are therefore believed to be primarily activated by phasic dopamine release (Wall et al., 2011). This suggests the possibility that impaired cognitive flexibility after partial dopamine depletion might also be mediated by dopamine D1 receptor-expressing MSNs and that the convergence of NMDA-receptor mediated glutamatergic and dopamine D1 receptor-mediated signaling is critical for normal cognitive flexibility. This integration of dopamine and glutamate signals has been proposed to be fundamental for striatal long-term plasticity and learning in corticostriatal circuits (Kelley, 2004).

The other main class of NMDA-receptor expressing cells in the striatum are dopamine D2-recpetor expressing MSNs. Our findings regarding direct-pathway MSNs do not rule out that MSNs of the indirect pathway or dopamine D2 receptor-mediated signaling also contribute to cognitive flexibility. Only severe (>80 %) reductions of striatal dopamine impact tonic dopamine release (Abercrombie et al., 1990, Robinson et al., 1994, Howard et al., 2011), which is thought to be mainly involved in the activation of dopamine D2 receptors. We attempted to clone an AAV1 Cre recombinase expression vector using a promoter sequence fragment from the Penk gene, which has been reported to be specifically expressed in indirect pathway MSNs. Unfortunately, introduction of this Penk-Cre virus resulted in non-specific expression of Cre in MSNs of the direct and indirect pathway (data not shown). We have previously shown that complete lack of striatal dopamine causes severe learning deficits that preclude behavioral testing of cognitive flexibility (Darvas and Palmiter, 2010), suggesting a potential involvement of dopamine D2 receptor-expressing indirect-pathway MSNs in mediating cognitive flexibility. Interestingly, striatal dopamine D2 receptors have been shown to be involved in processes related to working memory, another aspect of executive functioning dependent on the prefrontal cortical-striatal systems (Kellendonk et al., 2006). Moreover, dopamine D2 receptor availability in the dorsal striatum predicts the ability to modify behavior during a reversal learning task in vervet monkeys (Groman et al., 2011). Several groups have shown that dopamine D2 receptor signaling in general is critical for cognitive flexibility (Lee et al., 2007, Boulougouris et al., 2009, De Steno and Schmauss, 2009). However, the causal relationship between indirect pathway MSNs and cognitive flexibility warrants further investigation.

Taken together, we conclude that chronic reduction of NMDA-receptor mediated signaling in the dorsal striatum impairs cognitive flexibility and that dynorphin-expressing MSNs are one subset of neurons that are involved in this process. In addition, we present evidence suggesting that NMDA-receptor mediated impairments in strategy shifting are not merely a result of impaired motor function, but rather can accrue purely from deficient cognitive flexibility.

Reduction of NR1 expression in the dorsal striatum impairs cognitive flexibility

Partial loss of NR1 expression in the dorsal striatum does not impair motor coordination

Targeting of NR1 expression in direct pathway causes impaired cognitive flexibility

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This investigation was supported in part by the Pacific Northwest Udall Center NS062684 (M.D.) and Howard Hughes Medical Institute (R.D.P.). We thank Charles W. Henschen and Jeffrey T. Gibbs for sample preparation and for maintaining the mouse colony, Dr. Albert Quintana and Atiqur Rahman for assistance with protein quantifications and western blot experiments, and Dr. John Neumaier and Dr. Susan Ferguson for providing us with plasmid DNA containing the rat Prodynorphin promoter sequence.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors report no potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Abercrombie ED, Bonatz AE, Zigmond MJ. Effects of L-dopa on extracellular dopamine in striatum of normal and 6-hydroxydopamine-treated rats. Brain Res. 1990;525:36–44. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)91318-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albin RL, Makowiec RL, Hollingsworth ZR, Dure LSt, Penney JB, Young AB. Excitatory amino acid binding sites in the basal ganglia of the rat: a quantitative autoradiographic study. Neuroscience. 1992;46:35–48. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90006-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander GE, DeLong MR, Strick PL. Parallel organization of functionally segregated circuits linking basal ganglia and cortex. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1986;9:357–381. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.09.030186.002041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beutler LR, Eldred KC, Quintana A, Keene CD, Rose SE, Postupna N, Montine TJ, Palmiter RD. Severely impaired learning and altered neuronal morphology in mice lacking NMDA receptors in medium spiny neurons. PLoS One. 2011;6:e28168. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulougouris V, Castane A, Robbins TW. Dopamine D2/D3 receptor agonist quinpirole impairs spatial reversal learning in rats: investigation of D3 receptor involvement in persistent behavior. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2009;202:611–620. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1341-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun S, Hauber W. The dorsomedial striatum mediates flexible choice behavior in spatial tasks. Behav Brain Res. 2011;220:288–293. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner RL. Memory and executive function in aging and AD: multiple factors that cause decline and reserve factors that compensate. Neuron. 2004;44:195–208. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke HF, Walker SC, Crofts HS, Dalley JW, Robbins TW, Roberts AC. Prefrontal serotonin depletion affects reversal learning but not attentional set shifting. J Neurosci. 2005;25:532–538. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3690-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang MT, Yokoi F, Yin HH, Lovinger DM, Wang Y, Li Y. Disrupted motor learning and long-term synaptic plasticity in mice lacking NMDAR1 in the striatum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:15254–15259. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601758103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darvas M, Henschen CW, Palmiter RD. Contributions of signaling by dopamine neurons in dorsal striatum to cognitive behaviors corresponding to those observed in Parkinson's disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2014;65:112–123. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2014.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darvas M, Palmiter RD. Restriction of dopamine signaling to the dorsolateral striatum is sufficient for many cognitive behaviors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:14664–14669. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907299106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darvas M, Palmiter RD. Restricting dopaminergic signaling to either dorsolateral or medial striatum facilitates cognition. J Neurosci. 2010;30:1158–1165. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4576-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darvas M, Palmiter RD. Contributions of striatal dopamine signaling to the modulation of cognitive flexibility. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;69:704–707. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.09.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Steno DA, Schmauss C. A role for dopamine D2 receptors in reversal learning. Neuroscience. 2009;162:118–127. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.04.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorsey ER, Beck CA, Darwin K, Nichols P, Brocht AF, Biglan KM, Shoulson I Huntington Study Group CI. Natural history of Huntington disease. JAMA neurology. 2013;70:1520–1530. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.4408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunnett SB, Iversen SD. Sensorimotor impairments following localized kainic acid and 6-hydroxydopamine lesions of the neostriatum. Brain Res. 1982;248:121–127. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(82)91153-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floresco SB, Ghods-Sharifi S, Vexelman C, Magyar O. Dissociable roles for the nucleus accumbens core and shell in regulating set shifting. J Neurosci. 2006;26:2449–2457. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4431-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floresco SB, Magyar O. Mesocortical dopamine modulation of executive functions: beyond working memory. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;188:567–585. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0404-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrest D, Yuzaki M, Soares HD, Ng L, Luk DC, Sheng M, Stewart CL, Morgan JI, Connor JA, Curran T. Targeted disruption of NMDA receptor 1 gene abolishes NMDA response and results in neonatal death. Neuron. 1994;13:325–338. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90350-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fricker RA, Annett LE, Torres EM, Dunnett SB. The placement of a striatal ibotenic acid lesion affects skilled forelimb use and the direction of drug-induced rotation. Brain Res Bull. 1996;41:409–416. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(96)00083-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerfen CR. The neostriatal mosaic: multiple levels of compartmental organization in the basal ganglia. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1992;15:285–320. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.15.030192.001441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groman SM, Lee B, London ED, Mandelkern MA, James AS, Feiler K, Rivera R, Dahlbom M, Sossi V, Vandervoort E, Jentsch JD. Dorsal striatal D2-like receptor availability covaries with sensitivity to positive reinforcement during discrimination learning. J Neurosci. 2011;31:7291–7299. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0363-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard CD, Keefe KA, Garris PA, Daberkow DP. Methamphetamine neurotoxicity decreases phasic, but not tonic, dopaminergic signaling in the rat striatum. J Neurochem. 2011;118:668–676. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07342.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellendonk C, Simpson EH, Polan HJ, Malleret G, Vronskaya S, Winiger V, Moore H, Kandel ER. Transient and selective overexpression of dopamine D2 receptors in the striatum causes persistent abnormalities in prefrontal cortex functioning. Neuron. 2006;49:603–615. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley AE. Memory and addiction: shared neural circuitry and molecular mechanisms. Neuron. 2004;44:161–179. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence AD, Sahakian BJ, Rogers RD, Hodge JR, Robbins TW. Discrimination, reversal, and shift learning in Huntington's disease: mechanisms of impaired response selection. Neuropsychologia. 1999;37:1359–1374. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(99)00035-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee B, Groman S, London ED, Jentsch JD. Dopamine D2/D3 receptors play a specific role in the reversal of a learned visual discrimination in monkeys. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:2125–2134. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leverenz JB, Quinn JF, Zabetian C, Zhang J, Montine KS, Montine TJ. Cognitive impairment and dementia in patients with Parkinson disease. Curr Top Med Chem. 2009;9:903–912. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima CF, Meireles LP, Fonseca R, Castro SL, Garrett C. The Frontal Assessment Battery (FAB) in Parkinson's disease and correlations with formal measures of executive functioning. J Neurol. 2008;255:1756–1761. doi: 10.1007/s00415-008-0024-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madisen L, Zwingman TA, Sunkin SM, Oh SW, Zariwala HA, Gu H, Ng LL, Palmiter RD, Hawrylycz MJ, Jones AR, Lein ES, Zeng H. A robust and high-throughput Cre reporting and characterization system for the whole mouse brain. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:133–140. doi: 10.1038/nn.2467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palencia CA, Ragozzino ME. The influence of NMDA receptors in the dorsomedial striatum on response reversal learning. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2004;82:81–89. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2004.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker JG, Beutler LR, Palmiter RD. The contribution of NMDA receptor signaling in the corticobasal ganglia reward network to appetitive Pavlovian learning. J Neurosci. 2011;31:11362–11369. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2411-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisa M, Cyr J. Regionally selective roles of the rat's striatum in modality-specific discrimination learning and forelimb reaching. Behav Brain Res. 1990;37:281–292. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(90)90140-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintana A, Zanella S, Koch H, Kruse SE, Lee D, Ramirez JM, Palmiter RD. Fatal breathing dysfunction in a mouse model of Leigh syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2012 doi: 10.1172/JCI62923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinowitz JE, Rolling F, Li C, Conrath H, Xiao W, Xiao X, Samulski RJ. Cross-packaging of a single adeno-associated virus (AAV) type 2 vector genome into multiple AAV serotypes enables transduction with broad specificity. J Virol. 2002;76:791–801. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.2.791-801.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragozzino ME, Mohler EG, Prior M, Palencia CA, Rozman S. Acetylcholine activity in selective striatal regions supports behavioral flexibility. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2009;91:13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2008.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragozzino ME, Ragozzino KE, Mizumori SJ, Kesner RP. Role of the dorsomedial striatum in behavioral flexibility for response and visual cue discrimination learning. Behav Neurosci. 2002;116:105–115. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.116.1.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richfield EK, Penney JB, Young AB. Anatomical and affinity state comparisons between dopamine D1 and D2 receptors in the rat central nervous system. Neuroscience. 1989;30:767–777. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(89)90168-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins TW. Chemistry of the mind: neurochemical modulation of prefrontal cortical function. J Comp Neurol. 2005;493:140–146. doi: 10.1002/cne.20717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TE, Mocsary Z, Camp DM, Whishaw IQ. Time course of recovery of extracellular dopamine following partial damage to the nigrostriatal dopamine system. J Neurosci. 1994;14:2687–2696. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-05-02687.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samii A, Nutt JG, Ransom BR. Parkinson's disease. Lancet. 2004;363:1783–1793. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16305-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaner NC, Steinbach PA, Tsien RY. A guide to choosing fluorescent proteins. Nature methods. 2005;2:905–909. doi: 10.1038/nmeth819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson EH, Kellendonk C, Kandel E. A Possible Role for the Striatum in the Pathogenesis of the Cognitive Symptoms of Schizophrenia. Neuron. 2010;65:585–596. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsien JZ, Huerta PT, Tonegawa S. The essential role of hippocampal CA1 NMDA receptor-dependent synaptic plasticity in spatial memory. Cell. 1996;87:1327–1338. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81827-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voorn P, Vanderschuren LJ, Groenewegen HJ, Robbins TW, Pennartz CM. Putting a spin on the dorsal-ventral divide of the striatum. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27:468–474. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall VZ, Parker JG, Fadok JP, Darvas M, Zweifel L, Palmiter RD. A behavioral genetics approach to understanding D1 receptor involvement in phasic dopamine signaling. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2011;46:21–31. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Darvas M, Storey GP, Bamford IJ, Gibbs JT, Palmiter RD, Bamford NS. Acetylcholine encodes long-lasting presynaptic plasticity at glutamatergic synapses in the dorsal striatum after repeated amphetamine exposure. J Neurosci. 2013;33:10405–10426. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0014-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]