Abstract

Rapidly occurring changes in law enforcement and licensing of retail outlets to sell marijuana raises the prospect that the population of consumers will expand and accordingly the prevalence of cannabis use disorder (CUD) will increase. This report presents a novel approach to researching CUD etiology joining multivariate and ontogenetic perspectives. CUD is conceptualized as a developmental outcome consisting of transmissible (intergenerational) and non-transmissible components. Partitioning the liability for CUD into these two dimensions enables implementing interventions targeted at the particular source and severity of risk. In addition, results showing that infant temperament disturbances predict transmissible risk leading to CUD two decades later underscore the importance of implementing early prevention.

Keywords: cannabis, marijuana, etiology, prevention, development

INTRODUCTION

The 2013 annual survey of high school students indicates that 45.5% of seniors have used cannabis at least one time.1 The actual prevalence is in all likelihood higher considering that dropouts, truants and youths residing in detention facilities who are not included in the survey have higher rates of substance use than peers who attend school. Smoking cannabis at least one time, although illegal, is thus essentially normative behavior among youths despite their near-universal participation in prevention programs, exposure to harmfulness warnings in mass media, and knowledge of negative consequences if caught distributing or possessing marijuana. Indeed, desisting marijuana use is newsworthy. Lloyd Johnston, Principal Investigator of the Monitoring the Future Survey states: “But it should also be noted that fully half of today’s seniors have not tried an illicit drug by the end of high school”.2

Cannabis use disorder (CUD) has lifetime prevalence of 4.0% in the U.S..3 Among daily or near daily users, the prevalence of cannabis dependence is only 20–50%.4 Thus, CUD diagnosis encompassing criteria indicating biological, psychological and social harm is not the inevitable outcome of cannabis consumption. It is also notable that CUD prevalence is substantially lower than other outcomes of excessive behavior. For example, lifetime prevalence of obesity in the U.S. population over 20 years of age is 34.9%.5

The observation that most cannabis users do not develop CUD illustrates the importance of individual differences in liability. Falconer 6 defines liability as “…the individual tendency to develop or contract the disease, i.e., his susceptibly in the usual sense, but also the whole combination of external circumstances that make him more or less likely to develop the disease”. Liability encompasses three components: 1) characteristics of parents transmitted to children; 2) characteristics acquired via sibling influence; and, 3) characteristics of the extrafamilial environment. Applying the Tau model8 to partition these influences, Hopfer et al.9 observed that transmissible risk accounts for over 40% of variance underlying cannabis dependence. Extending these findings, it has also been shown that the manifold characteristics comprising transmissible10 and non-transmissible11 risk are indicators of unidimensional traits.

Developmental Perspective

CUD typically develops before 20 years of age.12 The anterior cortex is still undergoing maturation, indicating that the psychological disturbances associated with risk for substance use disorder14,15,16,17 have a neurobiological substrate and linked to child and adolescent development. Moreover, cannabis disrupts frontal cortex functioning18,19 which may cause impaired memory,20 suboptimal intellectual development,21 schizophreniform psychosis22 and depression and anxiety.23 In effect, neuromaturational processes evinced as cognitive, behavior and emotion disturbances during childhood and adolescence predisposes to cannabis use which disrupts neurological functioning to amplify the psychological disturbances.

Delineating the etiology of CUD requires, therefore, an ontogenetic framework to quantify age-specific indicators of transmissible and non-transmissible risk. In addition, to neuromaturation, individual differences in rate of sexual maturation also need to be taken into account. For example, appearing physically more advanced than same-age adolescent peers promotes opportunities to establish friendships with older youths. Considering that first substance use usually occurs in context of peer interactions, precocious youths are thus more likely to receive drug offers without having acquired the behavioral and cognitive competencies required to desist initiating consumption.24,25,26,27,28 Evincing secondary sex characteristics (e.g. facial hair in boys, breast development in girls) at a young age thus facilitates social interactions with older peers that create opportunities to initiate substance use which, contingent on subsequent circumstances, may or may not segue to CUD.

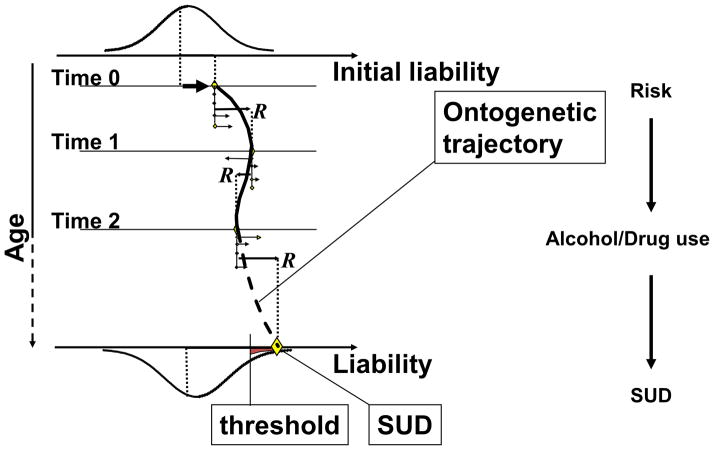

Figure 1 depicts a developmental model to guide etiology research. 29,30 Biobehavioral and environmental factors related to risk constitute vectors (V1, V2, V3…Vn); namely, quantities having both force (severity) and direction (increases or decreases risk for disorder). The aggregate of all factors, the Resultant Vector (VR), denotes overall risk. Connecting the VR’s across timepoints graphs the ontogenetic trajectory which terminates either as CUD or other outcome. The first task in etiology research therefore requires identifying the factors pertinent to risk for the disorder aligned to chronological age. Next, the pathway toward or away from disorder is charted by connecting the VR’s. As can be seen, concomitant to biobehavioral changes during development and changing environment, risk status (VR) changes during ontogeny and accordingly the pathway to SUD (or other outcomes) is not linear. Moreover, the transactional pattern has two main sources of influence: 1) selection, in which the person’s genetic and biobehavioral disposition biases preference to particular physical and social settings, and 2) contagion, in which a particular physical or social setting impacts the person. Myriad idiosyncratic factors operating through selection and contagion shape the direction and slope of the ontogenetic trajectory. For example, relocating to a neighborhood having low social capital, forming a friendship with a substance using peer and divorce of parents may increase the slope or alter the direction of the trajectory leading to initiating as well as maintaining substance use during adolescence. Because it is not possible to foresee future environmental events and personal experiences, it is not feasible to precisely forecast CUD. Prevention practice instead requires monitoring the transmissible and non-transmissible components of liability through the developmental period of risk.

Figure 1.

Ontogenetic model of substance use disorder.

Considering that many factors contribute to transmissible and non-transmissible liability, it is essential to measure the unique pattern of risk variables in each individual. Consistent with this person-centered focus, the Web-based self-administered Drug Use Screening Inventory (DUSI-R) measures severity (0–100%) of risk factors in ten health and psychosocial domains along with seven categories of psychiatric disorder.31,32,33 Intervention can, therefore, be tailored to the particular configuration of risk factors particular to each individual.

Research into CUD etiology and CUD prevention is hampered, however, by the absence of a necessary characteristic (or symptom) that must be present to confer diagnosis. One consequence of this deficiency in the DSM-IV and DSM-5 is that the same diagnosis can be assigned to individuals who do not share any characteristics or symptoms. In effect, CUD diagnosis is applied to different non-overlapping phenotypes. In the absence of a diagnostic system in which there is at least one attribute that is common to all affected individuals it is difficult, if even possible, to accurately delineate etiology.

ETIOLOGY OF CANNABIS USE DISORDER

Understanding CUD etiology requires taking into account the role and interplay of three factors: i) the agent, ii) individual differences in liability, and iii) environment and contributors to liability.

The Agent: Cannabis

Cannabis sativa has for millennia provided fiber to make cordage, oils from seeds to formulate medicines, and delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) from the flower to increase appetite for food and relieve distress from assorted medical problems. The pharmaceutical formulation of THC is sold under the brand name Marinol. THC also has psychoactive properties; Specifically, it induces calm euphoria. Systematic breeding since the 1960’s has produced many marijuana hybrids having distinctive aromas and flavors with THC concentrations ranging as high as 25%.34 This constitutes and eightfold increase in concentration compared to “weed” smoked in the 1960’s. THC concentration underlies intensity of subjective experience related to risk for CUD.35

Similar to all abusable substances THC impacts on the mesolimbic dopaminergic reward system.36,37,38 Moreover, genetic and phenotypic liability for CUD are congenerous with all other SUD categories.39,40,41 Thus, consistent with common liability, 42,43 CUD is one disorder on the spectrum of substance use disorders.44 Accordingly, the main factor, maybe the only factor that distinguishes CUD from other categories of alcohol or drug disorder, is the drug used (based largely on availability) and not unique characteristics of the individual.

The particular type of SUD manifested in adulthood maps to severity of externalizing disorder during childhood. Externalizing disturbance presaging cannabis use disorder is less severe than disorders consequent to using “hard” illegal drugs and more severe than disorders resulting from use of legal drugs.45,46 This is not unexpected considering that cannabis consumption, albeit illegal, is not strongly discordant with prevailing mores. Over 40% of high school seniors approve occasional marijuana use.1 Because social sanctions prohibiting consumption are weak, low deviance proneness prompts experimentation which, contingent on events occurring thereafter, may culminate in CUD.

Despite robust evidence demonstrating that the individual liability associated with cannabis use is the same as other abusable substances42,43,47 the gateway hypothesis advanced by Kandel and Yamaguchi48 theorizes that distinct risk factors predispose to initiation of each type of abusable drug. Cannabis is claimed to be a “gateway” drug because consumption often leads to “hard” illegal drugs. It is noteworthy, however, that research has not confirmed the presence of an invariant sequence. Many youths begin cannabis use after using “hard” drugs.49,50,51 Moreover, cannabis use often precedes using legal substances.52 Furthermore, Kandel and Yamaguchi’s interpretation of their data is arguably based on faulty logic. The error, termed post hoc ergo propter hoc (after this, therefore because of this), falsely asserts causality: “one licit drug is required (emphasis added) to make the progression to marijuana use” (p. 71). The false belief that cannabis use progresses to consumption of “hard” drugs has likely catalyzed the legislation of draconian laws to suppress cultivation, distribution and consumption of marijuana.

Individual Differences in Vulnerability

Numerous intercorrelated cognitive, emotion and behavior disturbances during childhood contribute to the individual’s vulnerability to develop substance use disorder.53 In severe cases the characteristics align with diagnosis of externalizing disorder such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder or conduct disorder. These disorders frequently presage substance abuse and substance use disorder.54,55,56 Impulsivity, the ubiquitous common feature of these disorders, has been shown in many studies to amplify risk for substance abuse and substance use disorders.57,58 Moreover, negative emotions such as anxiety and depression heighten risk for substance use disorder,59,60,61 indicating that internalizing disturbances are also facets of the liability.

Internalizing and externalizing disturbances are, however, not orthogonal. Krueger and Markon62 report a correlation of .50 between these two dimensions whereas Tarter et al.,63 report a correlation of .67 between factors encompassing the internalizing and externalizing scales of the Child Behavior Checklist. The second order factor capturing the variance shared between internalizing and externalizing dimensions predicts CUD between childhood and adulthood. The observation that both internalizing and externalizing disturbances precede consumption, and are correlated, supports the conclusion that the overall liability for substance use disorder can be parsimoniously characterized as deficient psychological self-regulation.14 Diverse characteristics reflecting psychological self-regulation comprise a continuous trait. Termed the transmissible liability index (TLI)10 twin studies reveal that 75%64 to 85%10 of score variance is heritable. Moreover, the TLI distinguishes boys according to presence/absence of substance use disorder in their fathers and predicts substance use disorder by early adulthood.65 Also, the TLI predicts age at the time of first substance use presaging substance use disorder diagnosis as well as the interval between first substance use and subsequent diagnosis. Furthermore, age at the time of first alcohol use mediates the association between TLI in childhood and CUD, and age of first cannabis use mediates the relationship between TLI and diagnosis of alcohol use disorder. In effect, the TLI measures liability that is common to both disorders. In adults, the TLI predicts all substance use disorder categories66 commensurate with the common liability model of addiction etiology. 10, 29, 30, 42, 43

Development of the TLI employed a multistage procedure.10 At the outset faculty at the Center for Education and Drug Abuse Research catalogued the psychological traits reported in the empirical literature to be related to risk for substance use disorder. Next, items were drawn from CEDAR’s database (over 10,000 variables at baseline) and, according to their face validity, assigned to these traits. Exploratory factor analysis was performed on the items to derive unidimensional constructs that were subsequently validated using confirmatory factor analysis. Items having loading below 0.4 were pruned and constructs that did not satisfy criteria for unidimensionality were excluded from further consideration. The remaining pool of items in the constructs that discriminated sons of fathers with and without lifetime substance use disorder were submitted to exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis yielding the unidimensional transmissibility liability index (TLI) consisting of 45 items having internal consistency of .92 in 10–12 year old boys. Age-specific versions of the TLI having internal consistency exceeding .90 at ages 12–14, 16, 19 and 22 have also been derived for administration in a computer adaptive test format.67 The five versions of the TLI can be found at www.pitt.edu/~cedar/TLIdocument.html. A scale to measure transmissible risk for substance use disorder in females is currently undergoing validation.

Results of a recent study indicate that children scoring high on the TLI before first time cannabis consumption evince a linear increase in risk severity following initial use that subsequently culminates in CUD by early adulthood.68 Youths scoring low on the TLI before first cannabis use on the other hand show a significant decline in risk between childhood and adulthood. In effect, initial experience with cannabis among high risk youths is a signal event that biases future development toward CUD. These findings underscore the importance of implementing prevention before opportunities arise and motivation for initiating consumption are established.

Because first substance exposure typically occurs in context of peer interactions and dysregulated youths are inclined to develop friendships with peers who have similar disposition, the onset of cannabis use culminating in CUD is the product of individual vulnerability and a social context that promotes (or at least tolerates) non-normative behaviors. Not surprisingly, non-normative socialization during adolescence mediates the relationship between childhood transmissible risk and substance use disorder in adulthood.69

Additionally, research at CEDAR has shown that a high score on the TLI in childhood predicts elevated testosterone level and attenuated cortisol level in mid-adolescence presaging substance use disorder.70 This pattern of hormone activity is consistent with a motivational style marked by aggressive dominance striving. Another pathway into habitual substance use culminating in diagnosis of substance use disorder may involve a potentiated reinforcing effect of abusable substances in individuals at high transmissible risk. Strong positive (euphoria) or negative (alleviation of stress) reinforcement increases the probability of establishing a pattern of regular drug consumption which may cause adjustment problems and accordingly qualify the person for CUD diagnosis. Inasmuch as it is illegal and unethical to administer abusable substances to minors it is not possible to determine whether youths who are at high transmissible risk before first exposure or in the early stages of consumption experience differentially strong drug reward. Among regular adult substance consumers it was observed however in a recent study that the slope depicting the rate of increase in TLI severity between ages 10–22 correlates with frequency of consumption of preferred drugs which in turn correlates with magnitude of aversive affect during the drug use event.71 In other words consumption induced neither self-medication (relief from an aversive state) nor euphoria but, instead, a punishing experience. Factors possibly contributing to habitual use besides hedonic experience include memory of prior euphoria and/or behavioral undercontrol. 72, 73, 74 Although systematic research remains to be conducted it appears from available results that cognitive and motivational factors among adult experienced users (including those who qualify for substance use disorder) may have a stronger influence on sustaining consumption than hedonic experience.

Social Environment

The Uniform State Narcotic Act in 1934, Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act in 1970 consolidated Federal policy designating cannabis sativa a dangerous plant. Vigorous law enforcement often accompanied by long prison sentences were intended to protect public safety. Eradicating the plant and ridding society of those associated with it constituted prevention. The expenditure of vast resources toward this effort notwithstanding, almost half of U.S. high school seniors have smoked marijuana. Moreover, results of the 2013 Monitoring the Future Survey indicate that 81.4% of high school seniors state that marijuana is easy to obtain. Indeed, 30-day prevalence of marijuana smoking currently exceeds cigarette smoking (22.7% vs. 16.3%).

The high prevalence of marijuana use can be traced to profound changes in U.S. society beginning in the 1960’s. Historically, smoking marijuana was confined to antisocial individuals and small marginalized segments of the population having low adherence to prevailing societal norms but who otherwise adhered to Federal law (beatniks, hipsters, jazz musicians, etc.). The generation born during or soon after the end of the second World War coming of age in the 1960’s was faced with a destabilized society grappling with violent ideological clashes over desegregation of public schools and universities, pervasive fantasy fears of an internal communist menace, and cold war with the Soviet Union. The civil rights movement, women’s movement and the Vietnam war imbued activism, rejection of traditional norms, and defiance of authority. Emergence of counterculture fostered acceptance of new lifestyles (e.g. communes, co-ed college dorms), including sex risk-free of pregnancy. Behaviors historically outside the societal norm became acceptable; this expansion of normative behavior continues to this day (e.g. body art, same-sex marriage). Smoking “weed” similarly shifted toward normative behavior catalyzed by recognition that “reefer madness” was not the inevitable outcome. In 1975 when reliable epidemiological data were first obtained, 18.1% of high school seniors perceived occasional marijuana smoking as harmful. By then the War on Drugs was already in full tilt. In 2013 the rate was 19.5%. Thus, during the past half century societal norms have been misaligned with Federal laws. As long as marijuana remains illegal it can be expected that norm-violating behaviors will be correlated with cannabis use. For example, a study conducted at CEDAR found that cannabis (but not alcohol) use mediates the association between transmissible risk for substance use disorder and number of lifetime violent offenses.75 The strength of association between cannabis use and violent and other antisocial behavior will in all probability weaken as the normally socialized segment of the population increasingly uses cannabis concomitant with emerging legal availability.

INTEGRATING TRANSMISSIBLE AND NON-TRANSMISSIBLE RISK

Paralleling research showing that transmissible risk consists of a continuous unidimensional trait, it has also been shown that non-transmissible risk capturing primarily various aspects of the environment, comprises a unidimensional scale. The score on this measure, termed the non-transmissible index (NTI), discriminates sons of fathers according to presence/absence of substance use disorder as well as predicts substance use disorder between childhood and adulthood.11 In effect, the NTI measures primarily the extrafamilial component of risk for substance use disorder, thereby complementing the TLI.

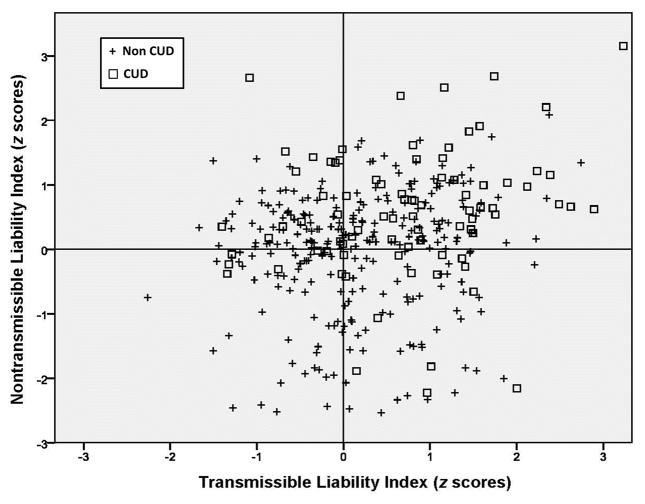

The transmissible and non-transmissible indexes can be configured in a Cartesian schema as shown in Figure 2. In this fashion the source as well as severity of risk for substance use disorder can be specified in the individual. As can be seen there is extensive heterogeneity of TLI and NTI scores in a sample of 10–12 year old boys. These data adapted from Tarter et al.14 indicate that 34% of boys who scored high on both the TLI and NTI developed CUD by age 22. Only 12% who scored low on both TLI and NTI developed CUD. Boys scoring high on one dimension and low on the other exhibited, as expected, rates of CUD that were midway between these two extreme groups. CUD was the outcome in 19% of boys who had below average TLI and above average NTI scores. The opposite pattern was associated with a 20% rate of CUD. These findings indicate that the TLI and NTI do not portend inevitable CUD outcome while underscoring the need for intervention to target the specific component of the liability.

Figure 2.

Integrating source and severity of risk for cannabis use disorder.

MODELING THE ETIOLOGY OF CUD IN AN ONTOGENETIC FRAMEWORK

Strong genetic influence on substance use disorder etiology39,40, 41 complemented by findings showing that genetic factors largely account for individual differences in TLI scores10,64 suggest that infant temperament, which is also strongly heritable, may comprise features of liability during the early postnatal period. Temperament, defined by Rothbart76 as “constitutionally based individual differences in reactivity and self-regulation” corresponds closely to the characteristics measured by the TLI in pre-pubertal children and adolescents.

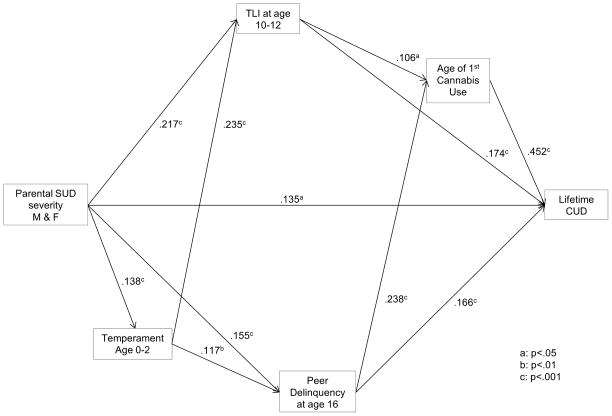

CEDAR data were analyzed to test the hypothesis that parental load for substance use disorder (i.e. number of affected parents) predicts temperament during infancy and TLI in late childhood that in turn forecasts CUD. Mothers rated their sons on a Likert scale according to “easy/difficult”, “active/passive”, “regular/irregular routines”, “friendly/unfriendly”, “low/high arousability threshold”, and “low/high distractibility”. Results of path analysis, shown in Figure 3, indicate that number of parents with substance use disorder predicts the sum of temperament scores which, in turn, forecasts transmissible risk at age 10–12 and affiliation with delinquent peers at age 16. These latter two variables in turn predict age of first cannabis use and CUD at age 22. Moreover, temperament mediates the association between parental SUD load and affiliation with non-normative peers (β = .02, z = 2.07, p = .04) illustrating the conjoint role of individual vulnerability and social environment on development of CUD. Although infant temperament does not directly predict age of first cannabis use or CUD it predicts transmissible risk in late childhood presaging the prodrome (cannabis use) and clinical disorder (CUD). Overall model-data fit is satisfactory (χ2 = 10.19, df =4, p = .04, root mean square error of approximation =.056, Tucker-Lewis index =.89, fit index =.97).

Figure 3.

Developmental pathway from infant temperament to cannabis use disorder

The demonstration that vulnerability for CUD may be measurable in infants underlines the importance of an ontogenetic focus in etiology research.77,78 Considering that almost half the variance related to cannabis dependence are transmissible; that is, has continuity between parents and children9 also informs the need for family-based interventions that are appropriate to the early stage of child development. One potentially effective approach arguably should involve inculcating affective synchrony between the caregiver and baby along with enhancing parental investment in childrearing and parenting competencies. Temperamentally difficult infants evoke negative reactions in caregivers who are also more likely (due to heritability) to have similar temperament disturbances which in adulthood manifest as poor psychological self-regulation, psychiatric disorders, and substance use disorder. Hence, concerted effort needs to be directed at promoting a positive caregiver-infant relationship. Chaotic or insecure attachment pattern is well-known to heighten risk for disruptive behavior in middle childhood which commonly segues to substance abuse in adolescence and thereafter culminates in substance use disorder. Recently, it has been shown that parent-child attachment mediates the association between psychological dysregulation during adolescence and risk for substance use disorder in adulthood.79 Hence, interventions which promote the developmental trajectory toward normative socialization, beginning with consolidation of a positive relationship between caregiver and infant, would most likely have substantial impact on preventing substance use disorder.

CONCLUSIONS

Cannabis use disorder (CUD) has multifactorial etiology originating during fetal development. Manifold factors contributing to etiology can be aggregated into continuous scales measuring transmissible (intergenerational) and non-transmissible risk. Measuring these two components of etiology within a Cartesian framework enables depicting the individual’s source and severity of risk. Accordingly, the focus and intensity of prevention can be accurately determined. Furthermore, the finding that parental substance use disorder predicts infant temperament that in turn predicts transmissible risk in late childhood presaging CUD indicates that it is important to implement prevention before the child consolidates behaviors during middle and late childhood predisposing to cannabis use and CUD.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

The authors received support from the National Institute on Drug Abuse grants P50-DA05605, K05-DA031248, and K02-DA017822. The funding agency was not involved in the research or preparation of this report.

Footnotes

The authors report no conflict of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Ralph Tarter and Maureen Reynolds largely focused on the narrative, and Levent Kirisci emphasized model development and testing.

References

- 1.Johnston L, O’Malley P, Bachman J, Schullenberg J. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2012. Volume 1: Secondary school students. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan; 2013. p. 604. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. American teens more cautious about using synthetic drugs. University of Michigan News Service; Ann Arbor, MI: Dec 18, 2013. Retrieved 01/27/2014 from http://www.monitoringthefuture.org. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Compton WM, Grant BF, Colliver JD, Glantz MD, Stinson FS. Prevalence of marijuana use disorders in the United States 1991–1992 and 2001–2002. JAMA. 2004;291:2114–2121. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.17.2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coffey C, Carlin JB, Degenhardt L, et al. Cannabis dependence in young adults: an Australian population study. Addiction. 2002;97:187–194. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. NCHS Data Brief. Vol. 131. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics; 2013. Prevalence of obesity among adults: United States, 2011–2012. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Falconer DS. The inheritance of liability to certain diseases estimated from the incidence among relatives. Ann Hum Genet. 1965;29:51–76. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zerhouni E. The NIH Roadmap. Science. 2003;302(5642):63–72. doi: 10.1126/science.1091867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rice J, Cloninger C, Reich T. Multifactorial inheritance with cultural transmission and assortative mating. 1. Description and basic properties of the unitary models. Am J Hum Genet. 1978;30(6):618. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hopfer CJ, Crowley TJ, Hewitt JK. Review of twin and adoption studies of adolescent substance use. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42:710.719. doi: 10.1097/01.CHI.0000046848.56865.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vanyukov M, Kirisci L, Moss H. Measurement of the risk for substance use disorders. Phenotypic and genetic analysis of an index of common liability. Behav Genet. 2009;39:233–244. doi: 10.1007/s10519-009-9269-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kirisci L, Tarter R, Mezzich A, et al. Prediction of cannabis use between childhood and young adulthood: Clarifying the phenotype and environtype. Am J Addict. 2009;18:36–47. doi: 10.1080/10550490802408829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wagner F, Anthony J. Male-female differences in the risk of progression from first use to dependence upon cannabis, cocaine and alcohol. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;86:191–198. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giedd JN. Structural magnetic resonance imaging of the adolescent brain. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2004;1021:77–85. doi: 10.1196/annals.1308.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tarter R, Horner M, Ridenour T. Developmental perspective of substance use disorder etiology. In: Shaffer H, editor. Addiction Syndrome Handbook. Washington, DC: American Psychological Press; 2012a. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dorard G, Berthoz S, Phan O, et al. Cannabis use and psychiatric and cognitive disorders: The chicken or the egg? Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2007;20:228–234. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3280fa838e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fergusson DM, Boden JM, Horwood LG. The developmental antecedents of illicit drug use: Evidence from a 25-year longitudinal study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;96:165–177. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spear L. The Behavioral Neuroscience of Adolescence. New York: Norton; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lundqvist T, Jonsson S, Warkentin S. Frontal lobe dysfunction in long-term cannabis users. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2001;23:437–443. doi: 10.1016/s0892-0362(01)00165-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Verrico CD, Jentsch JD, Roth RH. Persistent and anatomically selective reduction in prefrontal cortical dopamine metabolism after repeated, intermittent cannabinoid administration to rats. Synapse. 2003;49:61–66. doi: 10.1002/syn.10215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Solowig N, Battisti R. The chronic effects of cannabis on memory in humans: A review. Curr Drug Abuse Rev. 2008;1:81–98. doi: 10.2174/1874473710801010081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meier MH, Caspi A, Ambler A, et al. Persistent cannabis users show neuropsychological decline from childhood to midlife. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2012;109(40):e2657–e2664. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206820109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Castle DJ. F1000Reports Medicine. 2013. Jan 11, Cannabis and psychosis: what causes what? pp. 1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheung J, Mann R, Ialomiteanu A, et al. Anxiety and mood disorders and cannabis use. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2012;36:118–122. doi: 10.3109/00952991003713784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Halpern C, Kaestle C, Hallfors D. Perceived physical maturity, age of romantic partner, and adolescent risk behavior. Prev Sci. 2007;8:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s11121-006-0046-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Horner MS, Tarter R, Kirisci L, Clark DB. Modeling the association between sexual maturation, transmissible risk, and peer relationships during childhood and adolescence on development of substance use disorder in young adulthood. Am J Addict. 2013;20:1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2013.12046.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Westling E, Andrews JA, Hampson SE, et al. Pubertal timing and substance use. The effects of gender, parental monitoring and deviant peers. J Adol Health. 2008;42:555–563. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patton GC, McMorris BJ, Toumbourou JW, et al. Puberty and the onset of substance use and abuse. Pediatrics. 2004;114:e300–e306. doi: 10.1542/peds.2003-0626-F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reynolds MD, Tarter R, Kirisci L, et al. Testosterone levels and sexual maturation predict sub stance use disorders in adolescent boys: A prospective study. Biol Psych. 2007;61:1223–1227. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vanyukov M, Tarter R, Kirisci L, Clark D, et al. Liability to substance use disorders. 1. Common mechanisms and manifestations. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2003;27:507–515. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2003.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vanyukov M, Kirisci L, Tarter R, et al. Liability to substance use disorders: 2. A measurement approach. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2003;27:517–526. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2003.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tarter R. Evaluation and treatment of adolescent substance abuse: A decision tree method. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1990;16:1–46. doi: 10.3109/00952999009001570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tarter R, Kirisci L, Feske U, Vanyukov M. Modeling the pathways linking childhood hyperactivity and substance use disorder in young adulthood. Psychol Addict Behav. 2007;21:266–271. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.2.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kirisci L, Tarter R, Mezzich A, Reynolds M. Screening current and future diagnosis of psychiatric disorder using the revised Drug Use Screening Inventory. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2007;34:653–665. doi: 10.1080/00952990802308205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mechoulam R, Parker LA. The endocannabinoid system and the brain. Ann Rev Psychol. 2013;64:21–47. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grant JD, Scherer JF, Lyons MJ, Tsuang M, True WR, Bucholz KK. Subjective reactions to cocaine and marijuana are associated with abuse and dependence. Addict Behav. 2005;39(8):1574–1586. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koob GF, Volkow ND. Neurocircuitry of addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:217–238. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nestler EJ. Molecular neurobiology of addiction. Am J Addict. 2001;10:201–217. doi: 10.1080/105504901750532094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koob CF, LeMoal M. Drug addiction, dysregulation of reward, and allostasis. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;24:97–129. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00195-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kendler KS, Jacobson KC, Prescott CA, Neale MC. Specificity of genetic and environmental risk factors for use and abuse/dependence of cannabis cocaine hallucinogens sedatives stimulants and opiates in male twins. Am J Psychiatry. 2003a;160:687–695. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.4.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kendler KS, Prescott CA, Myers J, Neale MC. The structure of genetic and environment risk factors for common psychiatric and substance use disorders in men and women. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003b;60:929–937. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.9.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsuang MT, Lyons MJ, Meyer JM, Doyle T, Eisen SA, Goldberg J, et al. Co-occurrence of abuse of different drugs in men: the role of drug-specific shared vulnerabilities. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:967–972. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.11.967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vanyukov MM, Tarter RE, Kirillova GP, et al. Common liability to addiction and “gateway hypothesis”: Theoretical, empirical and evolutionary perspective. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;1235:S3–S17. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Iacono WC, Malone SM, McGue M. Behavioral disinhibition and the development of early onset addiction: common and specific influences. Ann Rev Clin Psychol. 2008;4:325–348. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.4.022007.141157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kirisci L, Tarter R, Vanyukov M, et al. Application of item response theory to quantify substance use disorder severity. Addict Behav. 2006;31:1035–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Krueger RF, Hicks BM, Patrick CJ, et al. Etiological connections among substance dependence, antisocial behavior, and personality: modeling the externalizing spectrum. J Abnorm Psychology. 2002;111:411–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Krueger RF, Markon KF, Patrick CJ, Benning SD, Kramer MD. Linking antisocial behavior substance use and personality: an integrative quantitative model of the adult externalizing spectrum. J Abnorm Psychology. 2007;116:645–666. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.4.645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Morral AR, McCaffrey DF, Paddock SM. Reassessing the marijuana gateway effect. Addiction. 2002;97:1493–1504. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kandel D, Yamaguchi D. Stages of drug involvement in the U.S. population. In: Kandel D, editor. Stages and Pathways of Drug Involvement: Examining the Gateway Hypothesis. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2002. pp. 65–89. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Golub A, Johnson B. Substance use progression and hard drug use in inner city New York, in Stags and Pathways of Drug involvement. In: Kandel D, editor. Examining the Gateway Hypothesis. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2002. pp. 90–112. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mackesy-Amiti ME, Fendrich M, Goldsein PJ. Sequence of drug use among serious drug users: Typical vs. atypical progression. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1997;45:185–196. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)00032-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Blaze-Temple D, Lo S. Stages of drug use: a community survey of Perth teenagers. Br J Addict. 1992;87:215–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1992.tb02695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tarter RE, Kirisci L, Ridenour T, Vanyukov M. Prediction of cannabis use disorder between childhood and young adulthood using the child behavior checklist. J Psychopath Behav Assess. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s10862-008-9083-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sloboda Z, Glantz MD, Tarter RE. Revisiting the concepts of risk and protective factors for understanding the etiology and development of substance use and substance use disorders: Implications for Prevention. Sub Use Misuse. 2012;47:1–19. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2012.663280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bidwell LC, Henry EA, Willcutt EG, Kinnear MK, Ito TA. Childhood and current ADHD symptom dimensions are associated with more severe cannabis outcomes in college students. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;135:88–94. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Button TMM, Hewitt JK, Rhee SH, et al. Examination of the causes of covairaton between conduct disorder symptoms and vulnerability to drug dependence. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2006;9:38–45. doi: 10.1375/183242706776402993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Glantz MD, Anthony JC, Berglund PA, et al. Mental disorders as risk factors for later substance dependence. Estimates for optimal prevention and treatment benefits. Psychol Med. 2009;39:1365–1377. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708004510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.DeWit H. Impulsivity as a determinant and consequence of drug use: A review of underlying processes. Addict Biol. 2008;14:22–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2008.00129.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Verdejo-Garcia A, Lawrence AJ, Clark L. Impulsivity as a vulnerabitly marker for substance use disorders. I. Common mechanisms and manfiestations. Neurosci and Biobehav Rev. 2008;32:777–810. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sihvola E, Rose RJ, Dick DM, et al. Early-onset depressive disorders predict the use of addictive substnaces in adolescence: A prospective study of adolescent Finnish twins. Addiction. 2008;103:2045–2053. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02363.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Clark DB, Neighbors B. Adolescent substance abuse and internalizing disorders. Child Adol Psych Clinics of North America. 1996;5:45–57. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zimmerman P, Wittchen HU, Hofler M, et al. Primary anxiety disorders and the development of subsequent alcohol use disorders. A 4-year community study of adolescents and young adults. Psychol. Med. 2003;33:1211–1222. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703008158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Krueger R, Markon D. Understanding psychopathology. Melding behavior genetics, personality and quantitation psychology to develop an empirically based model. Curr Direct Psychol Science. 2006;15:113–117. doi: 10.1111/j.0963-7214.2006.00418.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tarter R, Kirisici L, Ridenour T, Vanyukov M. Prediction of cannabis use disorder between childhood and young adulthood using the Child Behavior Checklist. J Psychopath Behav Assess. 2008;30:272–278. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hicks BM, Iacono WG, McGue M. Index of the transmissible common liability to addiction: Heritability and prospective associations with substance abuse and related outcomes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;123:S18–S23. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kirisci L, Tarter R, Ridenour T, et al. Age of alcohol and cannabis use onset mediates the association of transmissible risk in childhood and development of alcohol and cannabis disorders: Evidence for common liability. Exp Clin Psychopharmacology. 2013;21(1):38–45. doi: 10.1037/a0030742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ridenour TA, Tarter RE, Kirisci L, Vanyukov MM. Could a continuous measure of individual transmissible risk be useful in clinical assessment of substance use disorder? Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;119:10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kirisci L, Tarter R, Reynolds M, et al. Computer adaptive testing of liability to addiction: Identifying individuals at risk. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;123:S79–S86. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kirisci L, Tarter R, Ridenour T, Reynolds M, Vanyukov M. Longitudinal modeling of transmissible risk in boys who subsequently develop cannabis use disorder. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2013;39(3):180–185. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2013.774009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tarter R, Fishbein D, Kirisci L, et al. Deviant socialization mediates transmissible and contextual risk for cannabis use disorder development: A prospective study. Addiction. 2011;106:1301–1308. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03401.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tarter R, Kirisci L, Kirillova G, et al. Relationship among addiction risk, HPA and HPG neuroendocrine systems, and neighborhood quality: Results of a 10-year prospective study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;127:228–231. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tarter R, Kirisci L, Reynolds M, et al. Chasing the dragon: Association between transmissible risk, affect during drug use and development of substance use disorder. unpublished manuscript. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Barak S, Liu F, Ben Hamida S, et al. Disruption of alcohol-related memories by mTORC1 inhibition prevents relapse. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16(8):111–1117. doi: 10.1038/nn.3439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dalley JW, Laane K, heobald DEH, Milstein JA, et al. Cognitive and behavioral sequelae of intravenous cocaine and amphetamine self-administration in rats: impulsivity as a pre-morbid vulnerability trait. Soc Neurosci. 2004;382:2. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Everett BJ, Dickinson A, Robbins TW. The neuropsychological basis of addictive behavior. Brain Res Rev. 2011;36:129–138. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(01)00088-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Reynolds M, Tarter R, Kirisci L, Clark D. Marijuana but not alcohol use during adolescence mediates the association between transmissible risk for substance use disorder and number of lifetime violent offenses. J Crim Justice. 2011;39:218–223. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rothbart M, Derryberry D. Development of individual differences in temperament. In: Lamb ME, Brown AL, editors. Advances in developmental psychology. Vol. 1. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1980. pp. 37–86. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sloboda Z, Glantz M, Tarter R. Revisiting the concepts of risk and protective factors for understanding the etiology and development of substance use and substance use disorders: Implications for Prevention. Sub Use Misuse. 2012;47:944–962. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2012.663280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Glantz M. A developmental psychopathology model of drug abuse vulnerability. In: Glantz M, Pickens R, editors. Vulnerability to Drug Abuse. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1992. pp. 389–418. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhai Z-W, Kirisci L, Tarter RE, Ridenour TA. Psychological dysregulation during adolescence mediates the association of parent-child attachment in childhood and substance use disorder in adulthood. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2013.848876. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]