Summary

Early life stress can alter hypothalamic pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis function. Differences in cortisol levels have been found in preterm infants exposed to substantial procedural stress during neonatal intensive care, compared to infants born full-term, but only a few studies investigated whether altered programming of the HPA axis persists past toddler age. Further, there is a dearth of knowledge of what may contribute to these changes in cortisol. This prospective cohort study examined the cortisol profiles in response to the stress of cognitive assessment, as well as the diurnal rhythm of cortisol, in children (n=129) born at varying levels of prematurity (24–32 weeks gestation) and at full-term (38–41 weeks gestation), at age 7 years. Further, we investigated the relationships among cortisol levels and neonatal procedural pain-related stress (controlling for multiple medical confounders), concurrent maternal factors (parenting stress, depressive and anxiety symptoms) and children’s behavioral problems. For each aim we investigate acute cortisol response profiles to a cognitive challenge as well as diurnal cortisol patterns at home. We hypothesized that children born very preterm will differ in their pattern of cortisol secretion from children born full-term, possibly depended on concurrent child and maternal factors, and that exposure to neonatal pain-related stress would be associated with altered cortisol secretion in children born very preterm, possibly in a sex-dependent way. Saliva samples were collected from 7-year old children three times during a laboratory visit for assessment of cognitive and executive functions (pretest, mid-test, end - study day acute stress profile) and at four times over two consecutive non-school days at home (i.e. morning, mid-morning, afternoon and bedtime - diurnal rhythm profile). We found that cortisol profiles were similar in preterm and full-term children, albeit preterms had slightly higher cortisol at bedtime compared to full-term children. Importantly, in the preterm group, greater neonatal procedural pain-related stress (adjusted for morphine) was associated with lower cortisol levels on the study day (p=0.044) and lower diurnal cortisol at home (p=0.023), with effects found primarily in boys. In addition, child attention problems were negatively, and thought problems were positively, associated with the cortisol response during cognitive assessment on the study day in preterm children. Our findings suggest that neonatal pain/stress contributes to altered HPA axis function up to school-age in children born very preterm, and that sex may be an important factor.

Keywords: cortisol, preterm, stress, HPA axis, pain, internalizing behavior, child, sex, low birth weight, maternal interaction

1. Introduction

During their stay in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) infants born at very low gestational age undergo many stressful and painful procedures. Early life stress is known to permanently affect neurobiological, hormonal and physiological systems (Heim and Nemeroff, 2002). Preterm infants are particularly at risk for adverse effects of early stress, since their physiological systems are very immature during their time in NICU. Their brains are in period of rapid development (Herlenius and Lagercrantz, 2004; Volpe, 2009) and their stress systems are sensitive to programming (Matthews, 2002) while they are exposed to repeated painful procedures in the NICU. Further, animal studies suggest that early life stress can have sex-dependent effects (e.g. Darnaudery and Maccari, 2008), Although less is known about the impact of early adversity and gender differences in humans, studies are emerging suggesting differential vulnerabilities for males and females in humans (e.g. Sandman et al., 2013; Ruttle et al., 2014). Since pain and stress are difficult to disentangle in very preterm infants, we use the term “pain-related stress” to capture stress of invasive procedures (Grunau et al., 2013). Although necessary, frequent invasive procedures during hospitalization of very preterm infants such as blood draws or injections (i.e. ‘pain-related stress’) may contribute to altered programming of neuroendocrine systems such as the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis and thus influence stress-related behaviors long-term in children born very preterm (Brummelte et al., 2012; Zouikr et al., 2014). Considering the importance of cortisol in the regulation of behavior and cognition, and the vulnerability of the preterm population to problems in neurodevelopment (e.g. Grunau et al., 2006; Aarnoudse-Moens et al., 2009), it is essential to better understand the mechanisms underlying the differences in HPA axis function, as well as contextual influences that may modulate development of the HPA axis in children born preterm (Brummelte et al., 2011). In a longitudinal cohort, Grunau and colleagues have shown that infants and toddlers born very preterm exhibit altered HPA axis functioning at 3, 8 and 18 months corrected age (CA; age adjusted for prematurity) long after discharge from the NICU (Grunau et al., 2007). Infants born at extremely low gestational age (ELGA; 24–28 weeks gestation) and very low gestational age (VLGA; 29–32 weeks gestation) had significantly lower basal cortisol levels in the NICU (Grunau et al., 2005) and at 3 months CA compared to full-term infants, but at 8 and 18 months CA, ELGA infants had higher cortisol levels than VLGA and full-terms (Grunau et al., 2007). Furthermore, in this cohort, infant and toddler behavior was related to cortisol levels at 3 months (Haley et al., 2008), 8 months (Tu et al., 2007) and 18 months (Brummelte et al., 2011) CA. For instance, at 18 months of age, ELGA children with higher internalizing behaviors (anxiety/depressive symptoms) showed higher basal cortisol levels and more prominent changes in cortisol in response to a cognitive challenge (Brummelte et al., 2011). Although altered patterns of cortisol secretion have been associated with internalizing behavior in children born both preterm (Brummelte et al., 2011) and full-term (Essex et al., 2010), behavioral problems are particularly prevalent and persistent in children born very preterm (for review see: de Jong et al., 2012). Moreover, preterm children appear to be particularly sensitive to environmental influences such as maternal behavior compared to full-term children (Tu et al., 2007; Brummelte et al., 2011). However, little is known of the etiology of these developmental problems and sensitivities in children born very preterm and their association with altered HPA axis function. In other studies, low birth weight has been associated with altered blood pressure and autonomic stress response in children and adults of varying ages; however, studies investigating the cortisol stress response in older children or adults born with low birth weight or low gestational age compared to controls found either non-significant or mixed results (for detailed review see: Kajantie and Raikkonen, 2010). The diurnal cortisol profile (i.e. variations in cortisol levels across the day), has received even less attention; however, one study found that children born preterm (albeit in a small sample) had higher awakening cortisol levels than those born full-term at school-age (Buske-Kirschbaum et al., 2007). As mentioned above, altered cortisol levels may be a result of early stress-induced programming of the HPA axis (Matthews, 2002; Meaney et al., 2007), however it is important to take into account potentially modulating current or prevailing influences such as maternal stress when investigating the impact of early life stress on later HPA axis function (Williams et al., 2013).

We have previously found that children born extremely preterm display behaviors indicative of stress during cognitive assessment at school age significantly more than children born full-term (Whitfield et al., 1997). Moreover we have found that their cortisol response differed during focused attention at 8 months (Grunau et al., 2004) and developmental assessment at 18 months (Brummelte et al., 2011), therefore cognitive assessment (cognitive challenge) at age 7 years was expected to be a stressor.

The aims of the current prospective cohort study were to: 1) compare cortisol levels to a cognitive challenge in children born at varying levels of prematurity (ELGA, VLGA) and at full-term, at age 7 years; 2) examine whether among children born preterm, cortisol levels at 7 years are related to neonatal pain/stress during hospitalization in the NICU; and 3) investigate relationships between concurrent child behavior problems and maternal factors in relation to child cortisol patterns. For each aim we investigate acute cortisol response profiles to a cognitive challenge as well as diurnal cortisol patterns at home. We hypothesized that children born preterm will differ in their pattern of cortisol secretion from children born full-term, possibly depended on concurrent child and maternal factors, and that exposure to neonatal pain-related stress would be associated with altered cortisol secretion in children born very preterm, possibly in a sex-dependent way.

2. Material and Methods

2.1 Participants

Participants of this study were 156 children (43 ELGA, 63 VLGA and 50 full-term) and their primary caregiver (98% mothers), who were part of a larger longitudinal cohort study on long-term effects of neonatal pain (e.g. Grunau et al., 2007). Children were seen for a cognitive assessment at 7 years of age. Preterm infants had been recruited through the NICU at the Children’s and Women’s (C&W) Health Centre of British Columbia. Healthy full-term control children were recruited either from the regular maternity unit at the same Centre, through their pediatricians, or through community advertisements. Children were excluded from the current study if they had severe brain injury evident on neonatal ultrasound (periventricular leucomalacia or grade 3 or 4 intraventricular hemorrhage) (n=4), major cognitive impairment or diagnosis of autism (n=1) or if they were currently taking medications which are known to interfere with cortisol levels (n=13). Further, we excluded children who had received postnatal glucocorticoids in the NICU (i.e. dexamethasone or hydrocortisone, n=9), leaving a final sample size of n=129 (27 ELGA, 57 VLGA and 45 full-term).

2.2 Procedures

All procedures were approved by the University of British Columbia and Children’s and Women’s Health Centre of B.C. Clinical Research Ethics Board. Written informed consent was obtained from parents and written assent from children.

Children were seen at age 7 years for cognitive testing. The primary caregiver filled out questionnaires while children underwent cognitive testing. Three saliva samples were collected during the study day: 1) prior to the start of testing (pre-test, mean time for first saliva sample: 1015h +/− 50 min (SD)), but at least 30 min after arrival at the testing site; 2) 20 min after the cognitive testing (mid-test; mean time: 1205h +/− 67min) and 3) at the end of the visit (end, mean time 1410h +/− 62min). Further, parents were instructed how to collect eight saliva samples from their children over two non-school days at home (i.e. early morning, mid-morning, afternoon, and bedtime) and fill out a diary for those days.

2.3 Measures

2.3.1. Child and Maternal Characteristics

Neonatal information for the preterm children was obtained by medical and nursing chart review conducted by neonatal research nurses, including but not limited to: birth weight, gestational age, illness severity (Score for Neonatal Acute Physiology, SNAPII (Richardson et al., 2001)), Apgar scores, cumulative number of painful procedures (defined as every skin-breaking procedure from birth to term-equivalent age (Grunau et al., 2009)), cumulative morphine, midazolam and steroids (dexamethasone or hydrocortisone) dose adjusted for daily body weight (Grunau et al., 2009), postnatal infection (confirmed by lab analysis), and days of mechanical ventilation. Maternal and child demographic characteristics (age, education level) were collected by questionnaire (Table 1).

Table 1.

Child and Mother Characteristics

| ELGA (n=27) | VLGA (n=57) | Term (n=45) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neonatal characteristics | ||||

| Gestational age at birth (weeks) | 27.3 (1.2)a, b | 31.3 (1.2)b | 39.9 (0.9) | <.001* |

| Birth weight (g) | 973 (218) a,b | 1577 (346)b | 3502 (503) | <.001* |

| Small for gestational age (%) | 3.7% | 12.5% | 2.2% | .10 |

| Illness severity day 1 (SNAP-II) | 17.5 (10.7) | 5.4 (6.8) | - | <.001* |

| Pain-related stress (number of skin-breaking procedures from birth to term) | 131.5 (56.2) | 56.9 (39.1) | - | <.001* |

| Mechanical ventilation/oscillation (days) | 13.1 (14.6) | 1.6 (3.9) | - | <.001* |

| Morphine exposure (cumulative dose [mg] adjusted for daily body weight) | 1.28 (2.8) | 0.23 (1.5) | - | .03* |

| Morphine (% exposed) | 74% | 27% | - | <.001* |

| Infection (% positive culture) | 48% | 9% | <.001* | |

| Maternal characteristics at visit | ||||

| Mother age (years) | 40.8 (4.8) | 41.1 (4.6) | 42.8 (5.0) | .14 |

| Mother years of education (years) | 15.5 (2.9)b | 16.2 (2.8)b | 18.4 (4.4) | .001* |

| Marital status (% married or common law) | 96.2 | 87.5 | 95.5 | .24 |

| Mother ethnicity (% Caucasian) | 70.4 | 78.9 | 88.9 | .14 |

| Parenting Stress Index Total score | 210.9 (41.9) | 215.3 (46.0) | 195.6 (35.9) | .07 |

| Beck Depression scale | 7.44 (7.7)b | 7.44 (7.3)b | 4.22 (4.8) | .04* |

| Trait Anxiety | 36.5 (9.8) | 36.6 (9.5) | 34.4 (8.6) | .44 |

| State Anxiety | 29.6 (8.3) | 30.8 (9.5) | 29.5 (8.2) | .73 |

| Child characteristics at visit | ||||

| Sex (% male) | 63 | 39 | 40 | .09 |

| Age (years) | 7.7 (0.4) | 7.7 (0.3) | 7.8 (0.8) | .26 |

| WISC-IV Full Scale IQ | 94.8 (12.4)a, b | 104.5 (13.0)b | 111.3 (12.0) | <.001* |

| Child Behavior Checklist | ||||

| Anxious/depressive behaviors | 56.3 (8.3) | 56.0 (8.3) | 54.9 (6.9) | .72 |

| Withdrawn/depressive behaviors | 56.5 (7.3) | 55.2 (7.5) | 54.6 (6.2) | .54 |

| Somatic complaints | 53.7 (4.7) | 55.6 (5.7) | 55.6 (5.8) | .29 |

| Social problems | 54.8 (6.3) | 55.3 (6.0) | 52.7 (4.8) | .07 |

| Thought problems | 54.2 (5.7) | 56.4 (8.0) | 53.7 (5.5) | .10 |

| Attention problems | 55.8 (8.4) | 57.6 (10.1)b | 52.9 (4.7) | .02* |

| Rule breaking behavior | 53.5 (5.6) | 54.1 (5.2) | 53.5 (5.5) | .82 |

| Aggressive behavior | 53.7 (5.9) | 54.8 (8.6) | 54.0 (7.3) | .79 |

ELGA: extremely low gestational age, VLGA: very low gestational age,

significant group effect,

significantly different from VLGA,

significantly different from full-term infants.

Unless otherwise indicated, values are mean and standard deviation (SD).

2.3.2. Child Cognitive Assessment and Behavior

The Wechsler Intelligence Scale for children – Fourth Edition (WISC-IV) was administered to preterm and full-term children during their visit to the Centre. The WISC-IV includes 4 index scores that make up the Full Scale IQ: Verbal Comprehension, Perceptual Reasoning, Working Memory, and Processing Speed. In addition, children’s executive functions were tested using computer-based tasks as previously described (Diamond et al., 2007). The primary caregiver completed the Child Behavior Checklist for Ages 6–18 years (CBCL; (Achenbach and Ruffle, 2000). The CBCL is a widely used method of identifying problem behavior in children. Using a three-point Likert scale (0=absent, 1= occurs sometimes, 2=occurs often), 113 questions were asked covering different aspects of child behavior (e.g. Attention Problems) in the past six months that are summarized into eight different syndrome scales and a total problem score.

2.3.3. Maternal Measures

Mothers completed three questionnaires:

Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI-II) (Beck et al., 1996): a multiple choice self-report inventory for measuring the severity of depressive symptoms comprised of 21 questions that are scored on a scale of 0–3 with higher scores indicating more severe depressive symptoms.

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) (Auerbach and Spielberger, 1972) comprises separate self-report scales for measuring State (acute) and Trait (general) anxiety. Scores range from 20–80 with higher scores indicating higher anxiety, with the norm for State 35±10 and Trait 35±9.

Parenting stress Index (PSI) (Abidin, 1995) is a 120 item questionnaire that yields scores for the Child Domain, and the Parent Domain that together make up the Total Parenting Stress Index score. Higher PSI scores indicate higher levels of parenting stress.

2.3.4. Child Cortisol

Saliva samples were collected at three time points (pretest, mid-test, end) during the visit to the laboratory on the study day using salivettes (Salimetrics. Salimetrics LLC, State College, PA). Further, parents collected saliva samples at home on two non-school days at four time points each day: 30 min after awakening, 11h, 15h and 20h (Wust et al., 2000), with no food/drink intake for 30 min prior to each sample. Parents were asked to return the samples to the laboratory with a diary including information on time of day when the sample was taken, when and what the child last ate or drank before each sample, current medication taken by the child and a detailed diary of the day’s circumstances. A limitation of this method is that the time of day of saliva collection was based on the parent’s report and could thus not be independently verified. Saliva samples were stored at −20C until assayed using the Salimetrics High Sensitivity Salivary Cortisol Enzyme Immunoassay Kit for quantitative determination of salivary cortisol (Salimetrics LLC, State College, PA). All samples were assayed in duplicate. The intra- and inter- assay coefficients of variation were 3.04% and 6.57%, respectively. Outliers (defined as a value >3 SD above the mean) were winsorized (< 1% of the data points) and all cortisol values were log transformed for statistical analyses. For the diurnal samples, all diaries were carefully checked for entries indicating circumstances that could affect cortisol levels (e.g. illnesses, altered daily schedule, food/drink within 30 min of sample collection, etc.) and individual samples were excluded where necessary. Furthermore, cortisol values were averaged for each time point over the two collection days at home.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Maternal demographic and child characteristics were analyzed using one-way ANOVA to examine differences between the groups (ELGA, VLGA, full-term). Cortisol levels were examined using repeated measures ANOVA with the three (study day) or four (home) time points of cortisol collections as within-subject factors and group (ELGA, VLGA, full-term) and sex (male, female) as a between subject factors, controlling for the time of saliva collection. General estimating equation modeling (GEE) with a robust sandwich estimator and an unstructured correlation matrix was used to investigate the modulating effect of subgroup, sex and (A) neonatal predictors (number of skin-breaking procedures adjusted for cumulative daily morphine exposure [standardized residuals]), days on mechanical ventilation, SNAP-II scores, infection [yes/no], small for gestational age [yes/no]); (B) child characteristics (age at visit, IQ, CBCL subscales scores (see table 2 and 3 for full list of subscales)) or (C) maternal factors (years of education, PSI scores, depressive and anxiety scores). Models (B) and (C) were performed including the whole cohort (i.e. both preterm and term children), while model (A) was performed for preterm children only since the neonatal factors were not applicable for children born full-term. GEE accounts for the repeated measures within each subject over time (pre-test, mid-test, end and early morning, mid-morning, afternoon, bedtime) by allowing for the correlation between the observations. The independent variables entered in each model were carefully selected based on our hypothesis or based on previously reported impact on cortisol levels or confounders of the pain-related stress impact.

Table 2.

Study day cortisol in relation to neonatal, child and maternal factors

| All | Boys | Girls | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect size | p-value | Effect size | p-value | Effect size | p-value | |

| Neonatal Model (Preterm only: n=77; 35 boys, 42 girls) | ||||||

| Sex (male) | −.036 | .65 | ||||

| Subgroup (ELGA) | −.019 | .59 | .146 | .042* | −.036 | .74 |

| Sex (male) x Subgroup (ELGA) | .11 | .17 | ||||

| Time of collection | −.024 | .001* | −.020 | .045* | −.026 | .007* |

| Illness severity day 1 (SNAP-II) | .000 | .87 | −.002 | .45 | .001 | .88 |

| Pain-adjusted for morphine | −.039 | .044* | −.083 | <.001* | −.015 | .62 |

| Mechanical ventilation/oscillation | .003 | .18 | .003 | .24 | .002 | .60 |

| Infection | −.08 | .09 | −.025 | .63 | −.089 | .38 |

| Small for gestational age | .082 | .53 | −.066 | .32 | .120 | .53 |

| Child Model (n=115: 50 boys, 65 girls) | ||||||

| Sex (male) | .074 | .19 | ||||

| Subgroup (ELGA) | .008 | .90 | .016 | .84 | −.007 | .92 |

| Subgroup (VLGA) | .058 | .19 | −.046 | .51 | .052 | .26 |

| Sex (male) x Subgroup (ELGA) | −.009 | .91 | ||||

| Sex (male) x Subgroup (VLGA) | −.121 | .13 | ||||

| Time of cortisol collection | −.023 | <.001* | −.022 | .008* | −.023 | .002* |

| Age at visit | −.018 | .71 | −.012 | .76 | −.014 | .86 |

| WISC-IV Full Scale IQ | .000 | .94 | .001 | .73 | −.001 | .47 |

| Child Behavior Checklist | ||||||

| Anxious/depressive behaviors | .003 | .41 | .005 | .22 | −.001 | .86 |

| Withdrawn/depressive behaviors | −.005 | .30 | −.006 | .09 | −.002 | .84 |

| Somatic complaints | −.003 | .31 | −.004 | .30 | −.002 | .49 |

| Social problems | −.004 | .29 | −.007 | .16 | −.007 | .45 |

| Thought problems | .007 | .02* | .010 | .03* | .004 | .36 |

| Attention problems | −.005 | .035* | −.009 | .04* | −.004 | .25 |

| Rule breaking behavior | .000 | .99 | .003 | .59 | −.002 | .66 |

| Aggressive behavior | .004 | .35 | .006 | .37 | .008 | .12 |

| Maternal model (n=114; 49 boys, 65 girls) | ||||||

| Sex (male) | .073 | .25 | ||||

| Subgroup (ELGA) | −.037 | .48 | .038 | .63 | −.035 | .50 |

| Subgroup (VLGA) | .027 | .52 | −.041 | .62 | .020 | .61 |

| Sex (male) x Subgroup (ELGA) | .015 | .87 | ||||

| Sex (male) x Subgroup (VLGA) | −.115 | .17 | ||||

| Time of cortisol collection | −.028 | <.001* | −.031 | <.001* | −.024 | .001* |

| Mother years of education | −.007 | .10 | .001 | .91 | −.014 | .05$ |

| Parenting stress index: total score | .000 | .82 | .000 | .98 | .000 | .67 |

| Beck depression scale scores | −.002 | .46 | −.006 | .15 | −.001 | .76 |

| Trait anxiety scores | .002 | .54 | .007 | .23 | .000 | .90 |

| State anxiety scores | .000 | .82 | −.001 | .74 | .003 | .29 |

Results from General Estimation Equation (GEE) model, together and separately for boys and girls.

The effect size describes the expected change per unit in the outcome variable (cortisol) with a change in the predictor variable. For example, each additional painful procedure decreased the log-transformed cortisol value by 0.039 (equivalent to 0.01 (μg/dl)) in the neonatal GEE model. ELGA: extremely low gestational age (24–28 weeks), VLGA: very low gestational age (29–32 weeks),

significant effect,

Trending effect

Table 3.

Diurnal cortisol pattern at home in relation to neonatal, child and maternal factors

| All | Boys | Girls | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect size | p-value | Effect size | p-value | Effect size | p-value | |

| Neonatal Model (Preterm only: n=63; 29 boys, 34 girls) | ||||||

| Sex (male) | −.017 | .55 | ||||

| Subgroup (ELGA) | −.027 | .73 | −.274 | .076 | −.022 | .87 |

| Sex (male) x Subgroup (ELGA) | .109 | .42 | ||||

| Time of collection | −.078 | <.001* | −.049 | <.001* | −.083 | <.001* |

| Illness severity day 1 (SNAP-II) | −.000 | .72 | −.004 | .67 | −.003 | .38 |

| Pain adjusted for morphine | −.047 | .023* | .014 | .88 | −.002 | .93 |

| Mechanical ventilation/oscillation (days) | .003 | .47 | .018 | .15 | −.002 | .72 |

| Infection (% positive) | −.010 | .83 | −.054 | .73 | .044 | .49 |

| Small for gestational age | −.050 | .44 | −.143 | .74 | .002 | .99 |

| Child model (n= 95; 39boys, 56 girls) | ||||||

| Sex (male) | .058 | .47 | ||||

| Subgroup (ELGA) | −.004 | .97 | −.026 | .90 | −.044 | .66 |

| Subgroup (VLGA) | .049 | .38 | −.125 | .60 | .048 | .39 |

| Sex (male) x Subgroup (ELGA) | −.031 | .81 | ||||

| Sex (male) x Subgroup (VLGA) | −.102 | .26 | ||||

| Time of cortisol collection | −.080 | <.001* | −.089 | <.001* | −.082 | <.001* |

| Age at visit | .008 | .89 | .021 | .93 | −.053 | .50 |

| WISC-IV Full Scale IQ | .000 | .48 | −.001 | .74 | −.003 | .13 |

| Child Behavior Checklist | ||||||

| Anxious/depressive behaviors | .000 | .95 | .010 | .56 | −.008 | .20 |

| Withdrawn/depressive behaviors | .003 | .42 | −.007 | .66 | .008 | .22 |

| Somatic complaints | .002 | .56 | .005 | .82 | .001 | .91 |

| Social problems | −.004 | .32 | −.011 | .72 | .001 | .94 |

| Thought problems | .004 | .26 | .013 | .62 | −.004 | .51 |

| Attention problems | −.003 | .19 | −.007 | .77 | −.007 | .02* |

| Rule breaking behavior | .003 | .45 | .014 | .56 | .003 | .65 |

| Aggressive behavior | −.001 | .71 | −.004 | .87 | .005 | .32 |

| Maternal model (n=94; 39 boys, 55 girls) | ||||||

| Sex (male) | .018 | .81 | ||||

| Subgroup (ELGA) | −.121 | .20 | −.699 | .10 | −.147 | .12 |

| Subgroup (VLGA) | −.014 | .79 | −1.08 | .01* | −.015 | .75 |

| Sex (male) x Subgroup (ELGA) | .112 | .34 | ||||

| Sex (male) x Subgroup (VLGA) | −.012 | .89 | ||||

| Time of cortisol collection | −.078 | <.001* | −.088 | <.001* | −.079 | <.001* |

| Mother years of education | −.004 | .49 | −.008 | .84 | −.004 | .65 |

| Parenting stress index: total score | .000 | .31 | .003 | .61 | −.001 | .02* |

| Beck depression scale scores | .005 | .21 | .050 | .19 | .009 | .05$ |

| Trait anxiety scores | .004 | .19 | −.028 | .28 | .007 | .04* |

| State anxiety scores | −.003 | .21 | .023 | .38 | −.005 | .08 |

Results from General Estimation Equation (GEE) model, together and separately for boys and girls.

The effect size describes the expected change per unit in the outcome variable (cortisol) with a change in the predictor variable. For example, each additional painful procedure decreased the log-transformed cortisol value by 0.047 (equivalent to ~0.01 (μg/dl)) in the neonatal GEE model. ELGA: extremely low gestational age (24–28 weeks), VLGA: very low gestational age (29–32 weeks),

significant effect,

trending effect

3. Results

Maternal and child characteristics are displayed in Table 1.

3.1 Cortisol pattern during cognitive assessment (study day in the laboratory)

3.1.1 Comparison of cortisol levels in children born at varying levels of prematurity (ELGA, VLGA) and at full-term

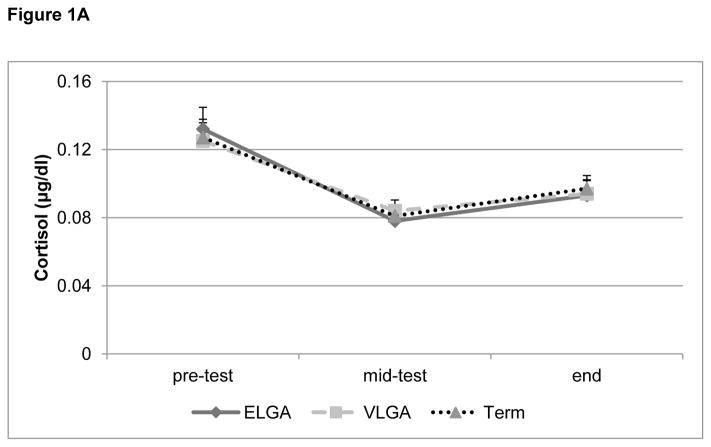

The repeated measures ANOVA revealed no significant main (p= 0.14) or interaction (p=0.24) effects for group, sex or time of saliva collection (all p’s > 0.13) (Figure 1A). All groups of children showed a significant decrease in cortisol levels at the mid-test time point and a subsequent plateau until the end of testing.

Figure 1.

Figure 1A: Cortisol pattern during cognitive assessment (study day in the laboratory).

Salivary cortisol (μg/dl, adjusted for time of testing, mean + S.E.M.) during cognitive assessment (pre-test, mid-test, end) for children born at extremely low gestational age (ELGA, 24–28 weeks), very low gestational age (VLGA, 29–32 weeks) and full-term at 7 years of age. All groups showed an initial drop in cortisol followed by a subsequent increase.

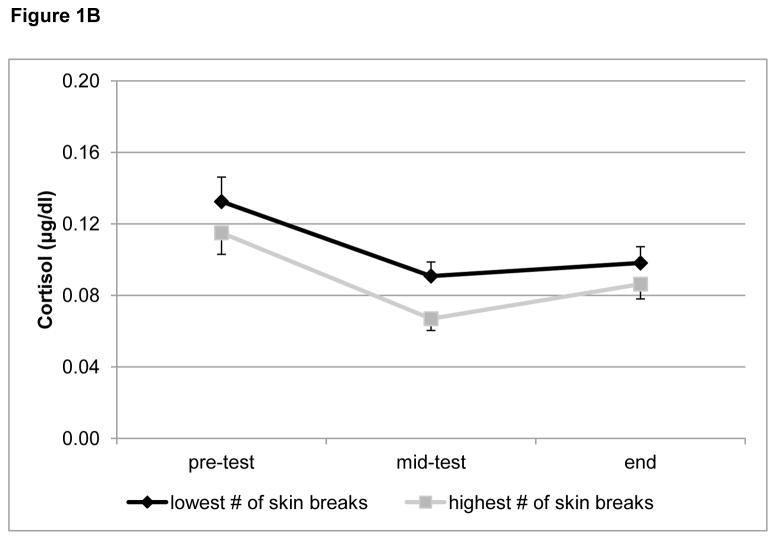

Figure 1B: Study day cortisol by number of skin breaking procedures.

Figure 1B displays salivary cortisol levels (μg/dl, mean + S.E.M.) from the laboratory visit for cognitive assessment, for children born preterm with either a low (lowest 4th Percentile) or high (highest 4th percentile) number of skin breaking procedures to illustrate the negative association between neonatal pain (corrected for morphine) and diurnal cortisol (p = 0.044) that was found with the neontal GEE model.

3.1.2. Relationship between neonatal pain/stress and cortisol levels at 7 years in children born preterm

The neonatal GEE model (including only preterm infants) revealed that neonatal pain-related stress adjusted for morphine exposure was significantly associated with lower cortisol levels overall during the cognitive assessment (p=0.044) (Figure 1B).

As we expected to see sex differences in relationships between neonatal and contextual factors and cortisol levels, we repeated the GEE analysis separately for each sex. This analysis demonstrated that neonatal pain-related stress, adjusted for morphine, was negatively associated with cortisol levels on the study day in boys only (p < 0.001).

3.1.3. Relationships between concurrent child behavior problems and child cortisol levels

The child GEE model (including both preterm and term-born children) showed that overall, CBCL Thought Problems were positively (p=0.02), and Attention Problems were negatively (p=0.035), associated with the cortisol pattern during the cognitive assessment in the laboratory (Table 2). In order to examine if the associations with CBCL problems were mostly due to a specific subgroup of children (i.e. preterm or full-term), we analyzed the two significant problem scores (thought and attention problems) separately with an GEE model (including gender, time, IQ and age) and found that for preterm children (ELGA and VLGA) thought problems were still positively (p=0.008) and attention problems negatively (p=0.014) associated with cortisol levels, while in full terms there was no significant association with either of the two scores (p > 0.56).

When the GEE analysis was repeated separately for each sex, we found that, among boys, higher cortisol levels were associated with greater CBCL Thought Problems (p = 0.03) and lower cortisol levels with greater CBCL Attention Problems (p = 0.04). By contrast, cortisol levels in girls were trending to be negatively associated with maternal years of education (p = 0.05).

These findings suggest that the overall associations of study day cortisol with neonatal pain-related stress and CBCL scores, respectively were driven primarily by effects in boys only.

3.1.4. Relationships between concurrent maternal factors and child cortisol levels

The maternal GEE model showed no significant contribution of concurrent maternal factors to the cortisol profile. Detailed results of all GEE models for cortisol levels during cognitive assessment are presented in Table 2.

All models included ‘time of collection’ as a co-factor to control for the variation in time of day of the sample collection. The strong statistical effect of ‘time of collection’ however (see Table 2 and 3) does not indicate a huge variation in the collection time (see section 2.2) but is rather indicative of the drop in cortisol levels during mid-testing (aka a change in cortisol levels over time). Running the GEE model without the time included still reveals a significant effect of pain-related stress

3.2 Diurnal cortisol pattern (at home)

Twenty-nine families did not return the diurnal saliva samples after their visit to the laboratory (7 ELGA, 10 VLGA and 12 full-term). Mothers that did not return samples self-reported higher depression (F (1, 128) = 9.31, p= 0.003) and higher state anxiety (F (1, 128) = 6.76, p= 0.01) compared to those who returned the samples.

3.2.1 Comparison of cortisol levels in children born at varying levels of prematurity (ELGA, VLGA) and at full-term

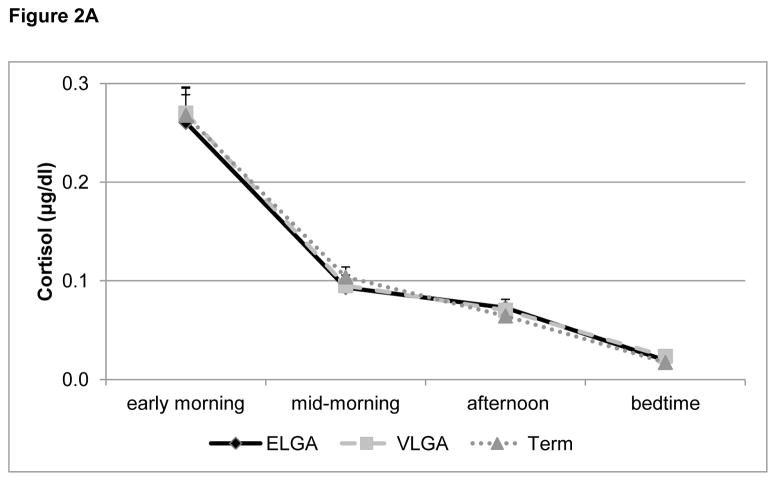

The repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant interaction of sex and collection time point (F (3, 246) = 4.39, p=0.009) and a trend for a main effect of subgroup (F(2, 82)= 2.42, p=0.095), but no other significant main or interaction effects (all p’s > 0. 18) (Figure 2A). Follow-up analysis (univariate ANOVAs) for each time point revealed a significant sex effect for the afternoon (F(1,93)=4.32, p=0.04), with girls (Mean ± S.E.M.: 0.064 μg/dl ± 0.004) having lower cortisol levels than boys (0.071 μg/dl ± 0.006), and a trend for a sex effect for the early morning (F(1, 94)=3.85, p=0.053), with girls (0.29 μg/dl ± 0.019) having higher levels than boys (0.21 μg/dl ± 0.017), but no sex effects for the midmorning (p=0.11) or bedtime (p=0.92) measures. Further, there was a trend for an interaction of sex and subgroup for the afternoon time point (p=0.086) and a trend for an effect of subgroup for the bedtime point (p=0.060). Further analysis repeating the univariate ANOVA and grouping ELGA and VLGA together, found a significant difference (F(1,91)=4.62, p=0.034) between preterm and full-term children, with preterms having higher cortisol levels than term at bedtime.

Figure 2.

Figure 2A: Diurnal cortisol pattern (at home)

Diurnal salivary cortisol (μg/dl, mean + S.E.M.), collected at home and averaged across two non-school days, for children born at extremely low gestational age (ELGA, 24–28 weeks), very low gestational age (VLGA, 29–32 weeks) and full-term, at 7 years of age. All groups showed the expected drop in cortisol levels throughout the day.

Figure 2B: Diurnal cortisol by number of skin breaking procedures.

Figure 2B displays diurnal salivary cortisol levels (μg/dl, mean+S.E.M.) for children born preterm with either a low (lowest 4th percentile) or high (higest 4th percentile) number of skin breaking procedures to illustrate the negative association between neonatal pain (corrected for morphine) and diurnal cortisol (p = 0.023) that was found with the neonatal GEE model.

3.2.2. Relationship between neonatal pain/stress and cortisol levels at 7 years in children born preterm

The neonatal GEE model (including only preterm children) revealed an overall negative association between neonatal pain-related stress (adjusted for morphine) and diurnal cortisol (p = 0.023). Figure 2B shows that this effect was particularly evident in the early morning when preterm-born children with the highest number of skin-breaking procedures had lower cortisol levels than those with the lowest number of skin-breaking procedures.

3.2.3. Relationships between concurrent child behavior problems and maternal factors and child cortisol levels

The child and maternal GEE models (including all children) revealed no significant contribution of any of the child (all p’s > 0.19) or maternal factors (all p’s > 0.18) to the diurnal cortisol pattern.

We repeated the GEE analysis separately for each sex and found that for girls, diurnal cortisol levels were positively associated with greater parenting stress (p = 0.02), maternal trait anxiety (p = 0.04) and marginally with maternal depressive (p = 0.05) symptoms, whereas no such association was seen in boys (all p’s > 0.19). Detailed results of all GEE models for diurnal cortisol levels are presented in Table 3.

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate that cortisol response as well as diurnal levels in preterm children at school age are predicted by neonatal pain-related stress in the NICU (after accounting for key clinical risk factors related to preterm delivery). In addition, although preterm-and term-born children showed similar diurnal cortisol patterns and salivary cortisol responses to an acute cognitive assessment at age 7 years, there was a trend for preterm infants to have higher cortisol levels at bedtime compared to full-term children. Further, our findings suggest that cortisol levels in boys appear to be more affected by early neonatal factors such as the exposure to the stress of skin-breaking procedures. In contrast, cortisol levels in girls were more sensitive to maternal factors such as stress, depression and anxiety.

Our results are in line with previous work from Buske-Kirschbaum et al., (2007), who also found no significant difference in the cortisol response pattern (to the Trier Social Stress Test [TSST]) in 10-year old children who were born preterm compared to their term-born counterparts. However, in that study gestational age was significantly correlated with cortisol levels up to 30 min after the stressor. In addition, a recent study by Kaseva et al. (2014) showed that adults born preterm had similar baseline cortisol levels compared to full term adults but significantly lower plasma cortisol levels in response to the TSST, though there was no difference in salivary cortisol or ACTH. This suggests that there may be subtle differences between preterm and full-term children in relation to their HPA axis function, but that there are no major differences in baseline cortisol levels between the groups.

It is generally difficult to induce a typical cortisol rise (as seen in adults) with a social stressor in children (Gunnar et al., 2009), which contributes to the challenge of identifying potential group differences at this age. Our cognitive assessment was not designed to induce a classical stress-response (i.e. rise in cortisol levels); indeed, all three groups responded with an initial decrease and subsequent plateau in cortisol levels (Figure 1A). This cortisol response pattern is very similar to the pattern (initial slight drop followed by no change or an increase back to pre-test levels) seen at younger ages in children from the same cohort in response to a visual attention task at 8 month CA (Grunau et al., 2004) and a developmental and cognitive assessment at 18 months CA (Brummelte et al., 2011). Interestingly, for ELGA toddlers, higher pretest cortisol levels and a steeper decrease from pre-test to post-test levels following cognitive challenge at 18 months CA was associated with higher mother ratings of child emotional reactivity, anxiety, depressive symptoms, withdrawal, attention problems and attention disorder/hyperactivity (ADHD) behaviors (Brummelte et al., 2011). This suggests that dysregulated HPA axis function may be associated with internalizing and other behavioral problems in this vulnerable population in early childhood. It is noteworthy that the results from the present study at 7 years of age suggest that this relationship with behavioral problems persisted, but was now found primarily in the boys and only for attention and thought problems. However, the fact that child attention problems were negatively, and thought problems were positively, associated with the cortisol response during cognitive assessment on the study day suggests that the relationship between behavioral problems and cortisol levels is not linear and may be difficult to interpret.

Also consistent with our results, Buske-Kirschbaum et al., (2007) reported no significant difference in the diurnal cortisol profile between children born preterm and full-term, except for a difference in the morning awakening response, with former preterms showing significantly elevated morning cortisol levels right after wakening when compared with the full-term controls, but no difference 30 min after awakening. As we only started our collection 30 min after awakening, we did not capture this particular time point with our diurnal sample collection. However, we observed slightly higher bedtime cortisol levels in preterm compared to full-term children, however, this trend was only significant if all preterm (ELGA and VLGA) were compared to full-term children and it is important to note, that the cortisol at bedtime was very low in all groups. Interestingly, we recently found that hair cortisol levels, an integrated measure of endogenous long-term HPA axis activity, were lower in preterm compared to full-term children at school age (Grunau et al., 2013). These apparently contradictory results are likely due to the fact that hair cortisol represents a measure of chronic HPA activity whereas salivary cortisol represents acute changes following stress or over the course of a day. Thus, the 4 time points we collected on two ordinary non-school days are just a glimpse into the HPA axis function and variation in cortisol levels in these children, whereas the hair cortisol represents rather a summary value of the continuous HPA axis output. If preterm infants have lower cortisol levels in response to daily stressors on school days for example, this would be reflected in lower hair cortisol levels, despite potentially higher bedtime cortisol levels since the bedtime values are so low compared to other times of the day. Together, these findings may suggest possible HPA axis dysregulation in children born preterm, with slightly higher evening cortisol levels possibly reflecting increased HPA tone or deficits in HPA regulation over the course of the day, and lower hair cortisol levels possibly reflecting down-regulation of HPA function in the longer term in response to the overall increase in HPA tone or activity. These relatively subtle differences in HPA axis function in preterm compared to full-term children can become meaningful in terms of effects on physiological and behavioral function if sustained over time.

Interestingly, previous studies have reported an inverse association between birth weight and cortisol in adults (Reynolds et al., 2001; Wust et al., 2005). For instance, Wust et al (2005) found that in young male adults, lower birth weight was associated with increased cortisol levels to the TSST, while length of gestation (ranging from 33–43 weeks) was positively but non-significantly correlated with cortisol levels after controlling for confounding factors. Noteworthy, the participants in this study were twins, and a low birth weight (compared to ‘just’ low gestational age), may be associated with adverse or stressful prenatal events. Further, an inverse relation of birth weight and basal cortisol levels or adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH)-stimulated levels has been reported for adult males (Phillips et al., 1998; Reynolds et al., 2001), further confirming the relationship of early life factors and HPA axis programming. However, it is important to note that low birth weight in term or nearly term infants is often associated with infants being small for their gestational age (SGA), which in turn may indicate intrauterine growth restriction or other prenatal conditions. Importantly in our present study, most infants had a birth weight appropriate for their gestational age and we follow the current convention in the field of prematurity that gestational age is a more accurate indicator of physiological maturity than birth weight, and in our statistical analyses we corrected for infants that were growth retarded (i.e. low birth weight for their gestational age (small-for gestational age [SGA]), thus further correcting for or including birth weight would be redundant (O’Shea et al. 2009).

Thus, altered HPA axis function in formerly preterm children may not be a direct consequence of low birth weight or preterm birth per se, but rather appears to be associated with the early stressful experiences these infants undergo during their time in the NICU. Our finding of a significant negative association between early neonatal pain-related stress and cortisol levels strongly supports this hypothesis of early programming of the HPA axis by early life stressful experiences. Children with a high number of skin-breaking procedures had lower cortisol levels throughout the study visit and particularly in the early morning diurnal samples compared to children with a lower number of skin-breaking procedures (Figures 1B and 2B). This is in line with our recent study on hair cortisol, which revealed, as noted above, that in preterm boys, but not girls, after adjustment for clinical and social confounders, lower hair cortisol levels were predicted by greater neonatal pain-related stress (Grunau et al., 2013). Animal studies across several species have strongly demonstrated that prenatal or neonatal stress can permanently alter HPA axis function and stress responses (for review see: Matthews, 2002). Similarly, early life stress contributes to programming of the human HPA axis (Reynolds, 2013). For example, Carpenter et al., (2007) reported that in healthy adults, childhood maltreatment was associated with significantly lower cortisol and ACTH levels in response to the TSST. Intriguingly, McGowan et al., (2009) showed in a post-mortem study that suicide victims with early childhood abuse had increased methylation of the NR3C1 promoter gene -encoding the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) - and decreased GR mRNA expression. Epigenetic alterations of the GRs may present a potential mechanism explaining the altered HPA axis function after early life adversity. However, more early life stress does not necessarily equal higher cortisol levels later in life, as cortisol is a rather complicated measure and can be influenced by the type, quality, time and duration of the stress exposure, which may result in down- rather than up-regulation of basal HPA axis activity and output.

Animal studies further suggest that early life stress can have sex-dependent long-term effects on the responsiveness of the HPA axis (Darnaudery and Maccari, 2008), with some studies reporting higher vulnerability or sensitivity in males compared to females (e.g. Mueller and Bale, 2008; Llorente et al., 2011), while others report changes in HPA function predominantly in females (McCormick et al., 1995). In humans, reports on sex-dependent HPA function vary considerably, probably due to many confounding factors such as age, hormone levels (e.g. menstrual phase), genetic or environmental factors, different types and timing of stressors and concurrent psychopathology (Kudielka et al., 2009). Although these variations in subject selection and study design may explain some of the discrepancies seen in the literature, it is also conceivable that males and females may have different developmental windows of vulnerability and/or adapt differently to early adverse environments and that a history of early maltreatment or adversity may thus be reflected in the broad range of findings on sex-dependent HPA function.

In the current study we did not observe any differences in the cortisol response to cognitive assessment or the diurnal cortisol pattern between boys and girls, but we did find that girls appeared to be more sensitive to concurrent maternal factors while boys appeared to be more sensitive to early life pain-related stress and thus boys may be more sensitive to early physiological, and girls to current psychosocial, challenges. Although human data on sex-dependent effects of early stress on HPA axis function are scarce, our results are in line with previous studies, suggesting higher sensitivity of males to early life adversity. For example, Jones et al., (2006) found that lower birth weight was significantly associated with higher salivary cortisol responses to the TSST in 7–9 year old boys, but not girls. Further, Heim and colleagues (2008) found that men, but not women with early life trauma had increased cortisol in response to a pharmacological challenge and Elzinga et al., (2008) found that blunted cortisol responses to the TSST in subjects with early trauma were more prominent in men than in women. Moreover, parental loss or separation is differently associated with HPA axis function in men and women (Tyrka et al., 2008; Pesonen et al., 2010). However, other studies have found stronger associations of early life stress and HPA axis function in women compared to men or failed to find a modulating effect of sex on the impact of early trauma (Kajantie and Raikkonen, 2010; DeSantis et al., 2011) and results are not always congruent in terms of the direction of the effect. Taken together, there seems to be more evidence for a stronger association of early life stress with HPA axis function in males compared to females (Kajantie and Raikkonen, 2010), which is in concert with our current results, i.e. when the data was analyzed separately by sex, only boys showed a significant association of cortisol levels with neonatal pain-related stress exposure. Importantly, we and others (Jones et al., 2006) have found these differences in prepubertal children. Thus concurrent sex steroid concentrations cannot sufficiently explain the observed sex differences (Kajantie and Raikkonen, 2010). Instead, evidence from animal studies suggests that early life stress may affect regulation of gonadal hormone function, and could thus interfere with gonadal programming of a sexually dimorphic brain (Bale, 2011), or with the bidirectional communication between the adrenal and gonadal axes (Viau, 2002). Sexual differentiation of the brain and endocrine systems begins in utero and thus it is not surprising that early stimulation of the HPA axis may affect the developing physiological systems of boys and girls differently. Considering that boys also showed the stronger association of cortisol with behavior problems, it is tempting to suggest that this different neonatal sensitivity may also contribute to sex-dependent pathophysiology with boys being more prone to attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) for example. However, more research is needed to better understand the impact of sex on neuroendocrine outcome, especially in the preterm population, as the early hormonal milieu likely differs in infants born preterm compared to infants in utero at a comparable period of gestation when pregnancy proceeds to full term.

A strength of the present study is our rigorous exclusion criteria, such that children with severe brain injury or major sensory/motor/cognitive impairments were excluded, as were children on any medication that might affect cortisol levels (e.g. drugs to treat attention deficit/ hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or asthma). While excluding such children rendered our findings conservative, it also ensured that confounding variables were well controlled.

5. Conclusion

Our results contribute to the growing literature on how early life experiences influence later HPA functioning. Early postnatal exposure to invasive procedures is unquestionably very stressful, especially when repeated multiple times daily over a period of physiological immaturity. Moreover, Grunau and colleagues have shown that pain-related stress involves systems beyond the HPA axis, and is associated with altered brain development, which also plays a role in determining long term outcomes (Vinall et al., 2014; for review see: Back and Miller, 2014). We recently found in a separate cohort of preterm infants, that the number of neonatal invasive procedures (adjusted for medical confounders related to prematurity) was associated with reduced white and grey matter development (Brummelte et al., 2012) underlining the vulnerability of the brain at this early stage. It is conceivable that this early impact of pain-related stress on the brain may play a role in neuroendocrine function later in life. Clearly, more research is needed to better understand how early adverse experiences in preterm infants in particular affect endocrine and nervous system maturation and thus long-term developmental outcomes. Nevertheless, our novel findings of a relationship between neonatal pain-related stress and HPA axis function, and a modulating role for sex in this relationship, advance our understanding of the influence of early adverse experiences on outcomes at school age.

Highlights.

Salivary cortisol levels in preterm children are predicted by neonatal pain-related stress

At school age, preterm and full term children show similar salivary cortisol profiles

Cortisol may be differentially affected by adverse factors in boys and girls

Acknowledgments

Role of the funding source

This study was supported by a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the National Institutes of Health R01 HD039783 to REG. REG is supported by a Senior Scientist salary award from the Child and Family Research Institute. SB was supported by the Louise & Alan Edwards Postdoctoral Fellowship in Pediatric Pain Research and was a member of the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Pain in Child Health Strategic Training Initiative. The funding sources had no further role in the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data; in the writing of the report and in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

We thank the families who participated, Gisela Gosse for coordinating the study, Wayne Yu for determination of salivary cortisol levels and Dr. Paul Theissen and his colleagues for help recruiting full-term controls.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aarnoudse-Moens CS, Weisglas-Kuperus N, van Goudoever JB, Oosterlaan J. Meta-analysis of neurobehavioral outcomes in very preterm and/or very low birth weight children. Pediatrics. 2009;124:717–728. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abidin RR. Parenting Stress Index. Psychology Resources; Odessa, FL: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Ruffle TM. The Child Behavior Checklist and related forms for assessing behavioral/emotional problems and competencies. Pediatr Rev. 2000;21:265–271. doi: 10.1542/pir.21-8-265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach SM, Spielberger CD. The assessment of state and trait anxiety with the Rorschach test. J Pers Assess. 1972;36:314–335. doi: 10.1080/00223891.1972.10119767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Back SA, Miller SP. Brain injury in premature neonates: A primary cerebral dysmaturation disorder? Ann Neurol. 2014;75:469–486. doi: 10.1002/ana.24132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bale TL. Sex differences in prenatal epigenetic programming of stress pathways. Stress. 2011;14:348–356. doi: 10.3109/10253890.2011.586447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for Beck Depression Inventory-II. Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Brummelte S, Grunau RE, Zaidman-Zait A, Weinberg J, Nordstokke D, Cepeda IL. Cortisol levels in relation to maternal interaction and child internalizing behavior in preterm and full-term children at 18 months corrected age. Dev Psychobiol. 2011;53:184–195. doi: 10.1002/dev.20511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brummelte S, Grunau RE, Chau V, Poskitt KJ, Brant R, Vinall J, Gover A, Synnes AR, Miller SP. Procedural pain and brain development in premature newborns. Ann Neurol. 2012;71:385–396. doi: 10.1002/ana.22267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buske-Kirschbaum A, Krieger S, Wilkes C, Rauh W, Weiss S, Hellhammer DH. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function and the cellular immune response in former preterm children. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:3429–3435. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter LL, Carvalho JP, Tyrka AR, Wier LM, Mello AF, Mello MF, Anderson GM, Wilkinson CW, Price LH. Decreased adrenocorticotropic hormone and cortisol responses to stress in healthy adults reporting significant childhood maltreatment. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:1080–1087. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darnaudery M, Maccari S. Epigenetic programming of the stress response in male and female rats by prenatal restraint stress. Brain Res Rev. 2008;57:571–585. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong M, Verhoeven M, van Baar AL. School outcome, cognitive functioning, and behaviour problems in moderate and late preterm children and adults: a review. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;17:163–169. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeSantis SM, Baker NL, Back SE, Spratt E, Ciolino JD, Moran-Santa Maria M, Dipankar B, Brady KT. Gender differences in the effect of early life trauma on hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis functioning. Depress Anxiety. 2011;28:383–392. doi: 10.1002/da.20795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond A, Barnett WS, Thomas J, Munro S. Preschool program improves cognitive control. Science. 2007;318:1387–1388. doi: 10.1126/science.1151148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elzinga BM, Roelofs K, Tollenaar MS, Bakvis P, van Pelt J, Spinhoven P. Diminished cortisol responses to psychosocial stress associated with lifetime adverse events a study among healthy young subjects. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2008;33:227–237. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essex MJ, Klein MH, Slattery MJ, Goldsmith HH, Kalin NH. Early risk factors and developmental pathways to chronic high inhibition and social anxiety disorder in adolescence. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:40–46. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.07010051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunau RE, Weinberg J, Whitfield MF. Neonatal procedural pain and preterm infant cortisol response to novelty at 8 months. Pediatrics. 2004;114:e77–84. doi: 10.1542/peds.114.1.e77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunau RE, Holsti L, Peters JW. Long-term consequences of pain in human neonates. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2006;11:268–275. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunau RE, Haley DW, Whitfield MF, Weinberg J, Yu W, Thiessen P. Altered basal cortisol levels at 3, 6, 8 and 18 months in infants born at extremely low gestational age. J Pediatr. 2007;150:151–156. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.10.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunau RE, Holsti L, Haley DW, Oberlander T, Weinberg J, Solimano A, Whitfield MF, Fitzgerald C, Yu W. Neonatal procedural pain exposure predicts lower cortisol and behavioral reactivity in preterm infants in the NICU. Pain. 2005;113:293–300. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunau RE, Whitfield MF, Petrie-Thomas J, Synnes AR, Cepeda IL, Keidar A, Rogers M, Mackay M, Hubber-Richard P, Johannesen D. Neonatal pain, parenting stress and interaction, in relation to cognitive and motor development at 8 and 18 months in preterm infants. Pain. 2009;143:138–146. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunau RE, Cepeda IL, Chau CM, Brummelte S, Weinberg J, Lavoie PM, Ladd M, Hirschfeld AF, Russell E, Koren G, Van Uum S, Brant R, Turvey SE. Neonatal Pain-Related Stress and NFKBIA Genotype Are Associated with Altered Cortisol Levels in Preterm Boys at School Age. PLoS One. 2013;8:e73926. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnar MR, Talge NM, Herrera A. Stressor paradigms in developmental studies: what does and does not work to produce mean increases in salivary cortisol. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34:953–967. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haley DW, Grunau RE, Oberlander TF, Weinberg J. Contingency Learning and Reactivity in Preterm and Full-Term Infants at 3 Months. Infancy. 2008;13:570–595. doi: 10.1080/15250000802458682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim C, Nemeroff CB. Neurobiology of early life stress: clinical studies. Semin Clin Neuropsychiatry. 2002;7:147–159. doi: 10.1053/scnp.2002.33127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim C, Mletzko T, Purselle D, Musselman DL, Nemeroff CB. The dexamethasone/corticotropin-releasing factor test in men with major depression: role of childhood trauma. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63:398–405. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herlenius E, Lagercrantz H. Development of neurotransmitter systems during critical periods. Exp Neurol. 2004;190(Suppl 1):S8–21. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones A, Godfrey KM, Wood P, Osmond C, Goulden P, Phillips DI. Fetal growth and the adrenocortical response to psychological stress. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:1868–1871. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-2077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajantie E, Raikkonen K. Early life predictors of the physiological stress response later in life. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2010;35:23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaseva N, Wehkalampi K, Pyhala R, Moltchanova E, Feldt K, Pesonen AK, Heinonen K, Hovi P, Jarvenpaa AL, Andersson S, Eriksson JG, Raikkonen K, Kajantie E. Blunted hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and insulin response to psychosocial stress in young adults born preterm at very low birth weight. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2014;80:101–106. doi: 10.1111/cen.12251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudielka BM, Hellhammer DH, Wust S. Why do we respond so differently? Reviewing determinants of human salivary cortisol responses to challenge. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34:2–18. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llorente R, Miguel-Blanco C, Aisa B, Lachize S, Borcel E, Meijer OC, Ramirez MJ, De Kloet ER, Viveros MP. Long term sex-dependent psychoneuroendocrine effects of maternal deprivation and juvenile unpredictable stress in rats. J Neuroendocrinol. 2011;23:329–344. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2011.02109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews SG. Early programming of the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2002;13:373–380. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(02)00690-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick CM, Smythe JW, Sharma S, Meaney MJ. Sex-specific effects of prenatal stress on hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal responses to stress and brain glucocorticoid receptor density in adult rats. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1995;84:55–61. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(94)00153-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGowan PO, Sasaki A, D’Alessio AC, Dymov S, Labonte B, Szyf M, Turecki G, Meaney MJ. Epigenetic regulation of the glucocorticoid receptor in human brain associates with childhood abuse. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:342–348. doi: 10.1038/nn.2270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meaney MJ, Szyf M, Seckl JR. Epigenetic mechanisms of perinatal programming of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal function and health. Trends Mol Med. 2007;13:269–277. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller BR, Bale TL. Sex-specific programming of offspring emotionality after stress early in pregnancy. J Neurosci. 2008;28:9055–9065. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1424-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Shea TM, Allred EN, Dammann O, Hirtz D, Kuban KC, Paneth N, Leviton A ELGAN Study Investigators. The ELGAN study of the brain and related disorders in extremely low gestational age newborns. Early Hum Dev. 2009;85:719–725. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2009.08.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesonen AK, Raikkonen K, Feldt K, Heinonen K, Osmond C, Phillips DI, Barker DJ, Eriksson JG, Kajantie E. Childhood separation experience predicts HPA axis hormonal responses in late adulthood: a natural experiment of World War II. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2010;35:758–767. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips DI, Barker DJ, Fall CH, Seckl JR, Whorwood CB, Wood PJ, Walker BR. Elevated plasma cortisol concentrations: a link between low birth weight and the insulin resistance syndrome? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:757–760. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.3.4634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds RM. Glucocorticoid excess and the developmental origins of disease: Two decades of testing the hypothesis - 2012 Curt Richter Award Winner. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds RM, Walker BR, Syddall HE, Andrew R, Wood PJ, Whorwood CB, Phillips DI. Altered control of cortisol secretion in adult men with low birth weight and cardiovascular risk factors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:245–250. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.1.7145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson DK, Corcoran JD, Escobar GJ, Lee SK. SNAP-II and SNAPPE-II: Simplified newborn illness severity and mortality risk scores. J Pediatr. 2001;138:92–100. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2001.109608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruttle PL, Klein MH, Slattery MJ, Kalin NH, Armstrong JM, Essex MJ. Adolescent adrenocortical activity and adiposity: Differences by sex and exposure to early maternal depression. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2014;47:68–77. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandman CA, Glynn LM, Davis EP. Is there a viability-vulnerability tradeoff? Sex differences in fetal programming. J Psychosom Res. 2013;75:327–335. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2013.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu MT, Grunau RE, Petrie-Thomas J, Haley DW, Weinberg J, Whitfield MF. Maternal stress and behavior modulate relationships between neonatal stress, attention, and basal cortisol at 8 months in preterm infants. Dev Psychobiol. 2007;49:150–164. doi: 10.1002/dev.20204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyrka AR, Wier L, Price LH, Ross N, Anderson GM, Wilkinson CW, Carpenter LL. Childhood parental loss and adult hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal function. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63:1147–1154. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viau V. Functional cross-talk between the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal and -adrenal axes. J Neuroendocrinol. 2002;14:506–513. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2002.00798.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinall J, Miller SP, Bjornson BH, Fitzpatrick KP, Poskitt KJ, Brant R, Synnes AR, Cepeda IL, Grunau RE. Invasive procedures in preterm children: brain and cognitive development at school age. Pediatrics. 2014;133:412–421. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-1863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpe JJ. Brain injury in premature infants: a complex amalgam of destructive and developmental disturbances. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:110–124. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70294-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitfield MF, Grunau RV, Holsti L. Extremely premature (< or = 800 g) schoolchildren: multiple areas of hidden disability. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 1997;77:F85–90. doi: 10.1136/fn.77.2.f85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams SR, Cash E, Daup M, Geronimi EM, Sephton SE, Woodruff-Borden J. Exploring patterns in cortisol synchrony among anxious and nonanxious mother and child dyads: a preliminary study. Biol Psychol. 2013;93:287–295. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2013.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wust S, Federenko I, Hellhammer DH, Kirschbaum C. Genetic factors, perceived chronic stress, and the free cortisol response to awakening. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2000;25:707–720. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(00)00021-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wust S, Entringer S, Federenko IS, Schlotz W, Hellhammer DH. Birth weight is associated with salivary cortisol responses to psychosocial stress in adult life. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2005;30:591–598. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zouikr I, Tadros MA, Barouei J, Beagley KW, Clifton VL, Callister RJ, Hodgson DM. Altered nociceptive, endocrine, and dorsal horn neuron responses in rats following a neonatal immune challenge. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2014;41:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]