Abstract

Purpose

To compare neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES) versus sham on leg strength at hospital discharge in mechanically ventilated patients.

Materials and Methods

We conducted a randomized pilot study of NMES versus sham applied to 3 bilateral lower extremity muscle groups for 60 minutes daily in ICU. Between 6/2008 and 3/2013, we enrolled adults who were receiving mechanical ventilation within the first week of ICU stay, and who could transfer independently from bed to chair before hospital admission. The primary outcome was lower extremity muscle strength at hospital discharge using Medical Research Council score (maximum = 30). Secondary outcomes at hospital discharge included walking distance and change in lower extremity strength from ICU awakening. Clinicaltrials.gov:NCT00709124.

Results

We stopped enrollment early after 36 patients due to slow patient accrual and the end of research funding. For NMES versus sham, mean (SD) lower extremity strength was 28(2) versus 27(3), p=0.072. Among secondary outcomes, NMES versus sham patients had a greater mean (SD) walking distance (514(389) vs. 251(210) feet, p=0.050) and increase in muscle strength (5.7(5.1) vs. 1.8(2.7), p=0.019).

Conclusions

In this pilot randomized trial, NMES did not significantly improve leg strength at hospital discharge. Significant improvements in secondary outcomes require investigation in future research.

Indexing terms: randomized controlled trial, electric stimulation, critical illness, intensive care units, respiration, artificial, muscle

Introduction

Survivors of critical illness face impairments in mobility and physical function, which can last up to 8 years after their intensive care unit (ICU) stay.[1–4] With more patients surviving critical illness,[5] greater numbers are at risk for post-ICU physical impairments. Early rehabilitation, started in the ICU while a patient is receiving mechanical ventilation, can improve patient outcomes and reduce ICU and hospital length of stay.[6–11] However, some critically ill patients are unable to actively engage in rehabilitation interventions due to issues such as severity of illness, delirium, deep sedation and coma. These patients may be especially vulnerable to muscle atrophy and weakness due to immobilization. The first week of a patient’s ICU stay is a critical time, with a 13% reduction in quadriceps cross sectional area.[12] Such changes can have long-term effects, with each day of bed rest in the ICU having an 3–11% relative decrease in muscle strength over 2 year follow-up.[13] Thus, rehabilitation interventions that can be initiated early may be especially important. Neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES) is a commonly-used physical therapy treatment and may be a potential early intervention to reduce muscular weakness in ICU patients.

NMES is a non-volitional rehabilitation therapy that applies an electrical current to muscles via electrodes placed on the skin, activating intramuscular nerve branches and inducing muscle contraction.[14] NMES is an established and safe therapy for improving strength after injury, immobilization, and bed rest in healthy, diseased, and post-operative patients.[15, 16] In a systematic review of NMES in 9 randomized clinical trials (RCTs) in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and 5 RCTs in patients with congestive heart failure, most studies demonstrated positive effects on skeletal muscle function, exercise capacity and health-related quality of life [17].

Recently, 3 systematic reviews synthesized information on the use of NMES in critically ill patients.[18–20] Across these reviews, authors identified 9 unique randomized trials of NMES in critically ill patients, and recognized potential benefits of NMES on muscle strength, function, and development of ICU-acquired weakness. [18–20] For example, in an RCT of 24 patients receiving long-term mechanical ventilation, adding NMES to usual rehabilitation resulted in a 15% increase in strength measured by manual muscle testing (p=0.001), and improved physical function with a reduced time to transfer from bed to chair (10.8 vs.14.0 days, p=0.001).[21] In one of the largest RCTs, authors identified a lower frequency of ICU-acquired weakness at ICU awakening in 52 evaluable patients (odds ratio 0.22, p=0.04).[22]

To-date, there is no published study of NMES started within the first week of ICU admission with patient outcomes measured beyond ICU discharge. Therefore, we conducted a pilot randomized study to evaluate if mechanically ventilated patients receiving NMES, in addition to usual rehabilitation, had greater lower extremity strength at hospital discharge versus those receiving sham intervention with usual rehabilitation. We also evaluated the effects of NMES on secondary measures of strength (e.g., whole body strength, grip strength) and function (e.g., walking distance, activities of daily living).

Materials and Methods

We conducted a single center, pilot randomized study of NMES versus sham intervention in mechanically ventilated patients.[23] Using a screening log,[24] we reviewed all patients admitted to 3 medical and surgical ICUs at Johns Hopkins Hospital for trial eligibility. Recruitment occurred between 2008 – 2009 and 2010 – 2013 (39 months in total). We temporarily suspended recruitment for 17 consecutive months due to a change in lead study personnel. Inclusion criteria were: ≥18 years of age, mechanically ventilated for at least 1 day, and expected to require at least 2 more days in the ICU. Exclusion criteria were: (1) body mass index (BMI) ≥35 kg/m2, (2) moribund status, (3) ICU length of stay >7 days or >4 days of continuous days of mechanical ventilation before enrollment, (4) known intracranial process (e.g., stroke) or primary systemic neuromuscular disease (e.g., Guillain Barre syndrome) at ICU admission, (5) unable to speak English or baseline cognitive impairment before ICU admission, (6) any conditions preventing NMES treatment or primary outcome evaluation in both legs (e.g., skin lesions or amputation), (7) unable to transfer independently from bed to chair at baseline before ICU admission, (8) presence of an implanted cardiac pacemaker or defibrillator, and (9) any limitation in care other than a sole order for no cardiopulmonary resuscitation. We also excluded patients who were pregnant, or had a known or suspected malignancy in the legs.

Following informed consent from the patient or the substitute decision-maker, we randomized patients in a 1:1 ratio to NMES versus sham control during their ICU stay (to a maximum of 45 days). We used sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes to conceal randomization allocation.[25] Our study was approved by the Johns Hopkins University Institutional Review Board (NA 000117423) and registered at clinicaltrials.gov (identifier NCT00709124).

NMES and Sham Intervention

In both groups, patients received usual care, as directed by the ICU team, including rehabilitation by physical and occupational therapists,[8, 26] and all patients were screened for physiologic stability before each NMES or Sham research session. We deferred a NMES or Sham session if patients had any of the following within 3 hours before a research session: received a neuromuscular blocker infusion, documented acidosis (pH by arterial blood gas <7.25 or venous blood gas <7.20), hyper- or hypotension (mean arterial pressure <60 mmHg or >120 mmHg), was on 1 vasopressor at >50% of the ICU’s maximum dose (dopamine >12.5 mcg/kg/min; phenylephrine >2 mcg/kg/min; vasopressin ≥0.02 units/min; norepinephrine >1 mcg/kg/min) or was on 2 vasopressors at 40% of maximum dose. Further, we deferred NMES or sham sessions if: (1) the patient had a new diagnosis of an acute pulmonary embolus or deep vein thrombosis in the legs and had not been therapeutically anticoagulated for >36 hours, or, (2) indicated by a physician in the setting of other signs of physiologic instability (e.g., temperature <34°C or >41°C, lactate >3.0 mmol/L, creatine kinase >400 U/L, platelets <20,000/mm3) or muscle inflammation (e.g., rhabdomyolysis, myositis, neuroleptic malignant syndrome, or serotonin syndrome).

Patients randomized to NMES received 60 minutes (either one 60-minute session, or two 30-minute sessions) of daily treatment bilaterally on 3 muscle groups (quadriceps (vastus medialis and vastus lateralis), tibialis anterior, and gastrocnemius)[27] using 3 identical dual channel NMES machines (CareStim, Care Rehab, McLean, VA). We based NMES settings on research available at the time of study design [21, 28, 29] and used pulsed current and a biphasic, asymmetrical, balanced rectangular waveform, with a ramp up time of 2 seconds, ramp down time of <1 second, and frequency (pulse rate) of 50 Hz. For the quadriceps, our pulse duration was 400 microseconds (µs) with an on-time of 5 seconds and an off-time of 10 seconds. For the tibialis anterior and gastrocnemius, the pulse duration was 250µs, on-time 5 seconds and off-time 5 seconds, with tibialis anterior contraction alternating with gastrocnemius to simulate physiologic contractions and optimize comfort. Before each NMES session, we assessed patients’ pain levels using the Behavioral Pain Rating Scale[30] (for sedated patients) or the Numerical Rating Scale[31] (for awake patients). We titrated NMES amplitude to visible muscle contraction, and re-assessed pain 5 minutes later, making readjustments to the NMES amplitude if the pain rating was over 2 points more than baseline. If we were unable to achieve visible contraction, we gradually increased the amplitude to the maximum value. As a late addition to the protocol, we systematically recorded whether patients achieved visible muscle contractions in the last 9 consecutive patients randomized to NMES. We provided NMES regardless of whether the patients were sedated or awake. If awake, no instructions were given to patients regarding initiating voluntarily muscle contractions during NMES.

Patients randomized to the Sham-intervention group were managed in an identical manner to the NMES group, but amplitude was set at 0 mA so no electrical stimulation occurred. All clinicians (e.g., physicians, nurses, therapists) were blinded to patients’ randomized group assignment. All patients received routine physical therapy interventions during their entire ICU and hospital stay. Our study was conducted in an ICU that prioritizes early physical therapy interventions with mechanically ventilated patients.[8] Physical therapists developed individualized treatment plans for patients following previously reported literature once patients were awake and able to participate in therapy.[10] Daily, therapists identified suitable interventions based on the patient’s physiologic status. Progressive mobility interventions included in-bed exercises, bed mobility (e.g., rolling, sitting at the edge of the bed), standing, transfer to chair, and ambulation, even if the patient was receiving mechanical ventilation. Study personnel (different from the treating physiotherapists) delivering the randomized intervention could not be blinded to the treatment group. In both NMES and Sham groups, we covered the patients’ legs with a sheet during the research sessions to maintain blinding of group assignment.

Outcomes

Our primary outcome was “lower extremity muscle strength” at hospital discharge, assessed by trained evaluators blinded to patients’ randomization assignment. This primary outcome was defined as the sum of bilateral strength assessments of quadriceps, tibialis anterior, and gastrocnemius muscles, each rated using the Medical Research Council (MRC) scale, ranging from 0 (no muscle contraction) to 5 (normal resistance), for a maximum score of 30 points.[32–34] For all strength assessments, we used standardized supine patient positioning, as per the American Spinal Injury Association [35] recommendations. Secondary outcomes included dynamometry strength measures for each of the quadriceps, tibialis anterior, and gastrocnemius muscle groups,[36, 37] overall upper and lower extremity muscle strength score,[33] hand grip dynamometry,[38] maximum inspiratory pressure,[39] the Functional Status Score for the ICU (FSS-ICU) physical function measure, a standardized evaluation of walking distance[40] (i.e., walking as far as possible up to a maximum of 1,000 feet), duration of mechanical ventilation, ICU readmission, ICU and hospital length of stay, hospital mortality, total hospital charges, and survivors’ hospital discharge disposition.[41]

Post-hoc, we evaluated additional outcomes to compare our results with NMES studies published after the design of our protocol.[22] At ICU awakening (defined as the ability to follow 3 of 5 verbal commands as per previous research),[33] we evaluated the proportion of patients with ICU-acquired weakness, defined as a Medical Research Council (MRC) sum score <48 [33] and evaluated a secondary measure of leg muscle strength based on evaluation of the hip flexor, knee extensor, and ankle dorsiflexor muscle groups (post-hoc leg muscle strength).[22] From baseline, we evaluated the change in FSS-ICU to ICU awakening, ICU discharge and hospital discharge, [40] and also evaluated the change in grip strength, FSS-ICU, and walking distance from ICU awakening to both ICU and hospital discharge.

Sample Size and Statistical Analysis

Based on data from similar patients at our study site,[40] we assumed a mean (standard deviation, SD) hospital discharge lower extremity strength score of 21.3 (6.8) points out of a maximum 30 for the sham control group. Since previous NMES trials reported strength gains of 24–31%,[21, 29] we believed a 25% increase in strength (i.e., 5.3 point difference in total score) was feasible and clinically important. Therefore, at 80% power and 5% alpha, we needed 54 survivors (27 per group) with outcomes assessments completed at hospital discharge.

For continuous variables, we compared the 2 randomized groups using Student’s t-test,[42] and for binary variables, Fisher’s exact test. We used Levine’s test for equality of variances for continuous variables. All tests were 2-tailed. We report all continuous data in means and SD, and report a 95% confidence interval (CI) for the difference in our primary outcome measure. We had no early stopping rules and conducted no interim analyses. Further details are provided our previously published study protocol.[41]

Results

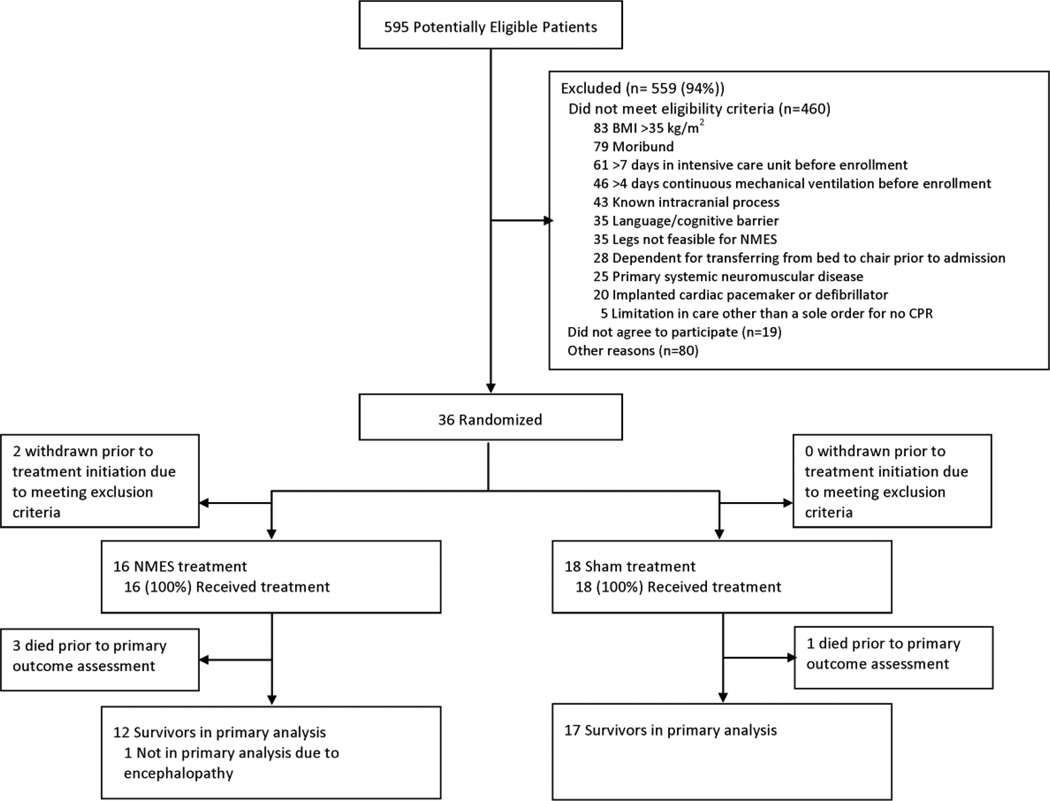

We identified 595 potentially eligible patients; of these, 55 met all eligibility criteria with 36 providing informed consent and subsequently randomized (Figure 1). We discontinued enrolment before reaching our sample size goal of 54 patients due to slow patient accrual and the end of research funding. Of 36 randomized patients, 2 were withdrawn (both randomized to NMES) before initiating any intervention because new information arose regarding presence of an exclusion criterion (i.e., both had new strokes identified by imaging). Thirty-four patients received NMES (n=16) or sham (n=18).

Figure 1.

Patient flow diagram

Of 34 patients randomized, 17 (50%) were female, 20 (58%) white, with a mean (SD) age of 55 (16) years (Table 1). There were no baseline differences between groups. Most patients were admitted for sepsis (62%). Patients had a mean (SD) APACHE II score of 25 (7). At baseline, 97% (n=33) of patients ambulated independently. Patients’ mean (SD) Functional Status Score for the ICU was 40 (4) out of a maximum score of 42. Of all 21 post-randomization ICU exposure variables evaluated, there were no differences between groups (Table 2), except for the mean (SD) daily duration of “usual care” physical therapy that was 8 minutes greater in NMES versus sham group (60 (31) vs. 52 (25) minutes, p=0.033) without any significant differences between groups in the number of days of physical therapy received.

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristicsa

| Overall (n=34) |

NMES (n=16) |

Sham (n=18) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 55 (16) | 54 (16) | 56 (18) | 0.741 |

| Female, n (%) | 17 (50) | 9 (56) | 8 (50) | 0.732 |

| White race, n (%) | 20 (58) | 7 (44) | 13 (72) | 0.163 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 27 (7) | 27 (9) | 27 (5) | 0.794 |

| Charlson comorbidity indexb | 2.1 (2.1) | 1.6 (1.7) | 2.6 (2.5) | 0.191 |

| Functional comorbidity indexc | 1.8 (1.7) | 1.8 (1.8) | 1.9 (1.7) | 0.825 |

| Living independently at home, n (%) | 29 (85) | 13 (81) | 16 (89) | 0.335 |

| Number of independent ADLs, mean (SD)d | 5.6 (0.8) | 5.6 (0.1) | 5.7 (0.9) | 0.781 |

| Number of independent IADLs, mean (SD)e | 5.7 (2.8) | 5.9 (3.0) | 5.5 (2.7) | 0.646 |

| Independent with ambulation, n (%) | 33 (97) | 16 (100) | 17 (94) | Not calculated |

| Functional Status Score for the ICU (FSS-ICU)f | 34 (3.7) | 34 (1.9) | 33 (4.7) | 0.474 |

| APACHE II scoreg | 25 (7) | 25 (8) | 25 (6) | 0.822 |

| ICU admission diagnosis, n (%) | 0.790 | |||

| Sepsis | 21 (62) | 9 (56) | 12 (67) | |

| Respiratory failure | 5 (15) | 3 (19) | 2 (11) | |

| Gastrointestinal | 3 (8) | 1 (6) | 2 (11) | |

| Other | 5 (15) | 3 (19) | 2 (11) |

Abbreviations: ADLs – Activities of Daily Living; IADLs – Instrumental Activities of Daily Living; APACHE II Score: Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II, ICU, Intensive Care Unit

Unless otherwise specified, mean (standard deviation) are presented

Charlson comorbidity index: a weighted score derived from 19 comorbidities, with higher scores reflecting increased 1-year mortality.[56]

Functional comorbidity index: a score derived from 18 comorbidities, with higher scores reflecting decreased 1-year physical function.[57, 58]

Katz Activities of Daily Living Scale: A score assessing the patient’s ability to complete 6 tasks: bathing, dressing, toileting, feeding, continence, and bed mobility. Higher scores represent better function.[59]

Lawton Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale: A score assessing the patient’s ability to do 8 items: use of the telephone, shopping, food preparation, housekeeping, laundry, use of transportation, ability to take medications, and managing finances. Higher scores represent better function.[60]

Functional Status Score for the ICU: a score assessing a patient’s ability to complete 5 bed mobility/ transfer tasks: rolling, supine to sit, sitting at edge of bed, transfer from sit to stand, ambulation. Each item is assessed on a scale from 0 (unable to perform) to 7 (independent). Higher scores reflect better function.[40] The score presented in Table 1 represent patients’ status prior to hospital admission.

APACHE II score: a severity of illness scale based on patient age, pre-existing medical conditions, and 12 acute physiologic variables assessed during the first 24 hours after ICU admission. Higher scores indicate greater severity of illness and increased short-term mortality.[61]

Table 2.

Post-Randomization Patient Exposures in the Intensive Care Unita

| NMES (n=16) |

Sham (n=18) |

p- value |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean daily SOFA scoreb | 6.2 (4.7) | 5.6 (1.6) | 0.630 |

| Ever received dialysis, n (%) | 4 (25) | 4 (22) | 1.00 |

| Mean daily creatine kinase, U/Lc | 647 (1267) | 85 (96) | 0.173 |

| Mean daily caloric intake from enteral feeding | 975 (436) | 793 (497) | 0.269 |

| Mean daily blood glucose, mg/dL | 144 (33) | 155 (32) | 0.402 |

| Mean daily maximum blood glucose, mg/dL | 178 (51) | 191 (47) | 0.883 |

| Mean daily insulin dose (units)d | 13 (20) | 15 (22) | 0.857 |

| Ever received systemic corticosteroids, n (%) | 10 (63) | 12 (67) | 1.000 |

| Mean daily corticosteroid dose (prednisone-equivalent, mg)d | 22 (27) | 38 (71) | 0.381 |

| Ever received a HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor, n (%) | 6 (33) | 5 (28) | 0.717 |

| Ever received neuromuscular blocker, n (%) | 2 (13) | 4 (22) | 0.660 |

| Ever received opioids, n (%) | 16 (100) | 18 (89) | 0.487 |

| Mean daily opioid dose (morphine-equivalent, mg)d | 49 (60) | 156 (259) | 0.105 |

| Ever received benzodiazepines, n (%) | 10 (63) | 15 (83) | 0.250 |

| Mean daily benzodiazepine dose (midazolam-equivalent, mg)d | 23 (36) | 47 (94) | 0.352 |

| Mean daily RASS scoree | −1.8 (1.6) | −1.1 (1.0) | 0.133 |

| Mean proportion of ICU days deliriouse n (%) | 67 (34) | 66 (32) | 0.947 |

| Number of days with physical therapy | 6.5 (7.0) | 7.1 (9.8) | 0.853 |

| Mean daily duration of physical therapy (minutes)f | 60 (31) | 52 (25) | 0.036 |

| Number of days with occupational therapy | 2.4 (2.1) | 2.1 (1.6) | 0.551 |

| Mean daily duration of occupational therapy (minutes)f | 38 (14) | 42 (18) | 0.254 |

| Mean number of days with NMES/sham sessions | 9.1 (8.7) | 10.8 (9.5) | 0.603 |

| Mean daily duration of NMES/ sham session (minutes) | 53 (11) | 53 (11) | 0.952 |

Abbreviations: SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment; RASS, Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale; ICU, Intensive Care Unit; NMES, neuromuscular electrical stimulation

Unless otherwise specified, mean (SD) are presented for each randomized group

SOFA: A composite score evaluating 6 organ systems used to assess the severity of organ dysfunction in the ICU.[56]

Not evaluated as part of study protocol. Data presented are available data within the medical record for 11 NMES and 11 Sham patients. A single outlier from the NMES group had high creatinine kinase levels during ICU stay; No temporal relationship between creatine kinase elevation and receipt of NMES sessions was observed.

Mean calculated only for days that the patient received the drug

Only collected on days when patient received NMES/Sham session. Only evaluable on days when RASS not −4 or −5. Number of days measured: NMES = 106 and Sham = 172

Mean calculated for only days in which the patient received physical therapy or occupational therapy

The mean (SD) time from ICU admission to first NMES or Sham session was 4.6 (1.8) and 4.4 (1.6) days, respectively (p=0.839). Patients received a mean (SD) of 9.1 (8.7) and 10.8 (9.5) days with NMES or sham, respectively (p=0.603), with a daily duration of 53 (11) and 53 (11) minutes, respectively (p=0.952). NMES and Sham patients received 63% (n = 146/230) and 77% (n=194/252), respectively, of all potential daily research sessions, with most sessions omitted due to the pre-screening safety criteria. Of the last 9 consecutive NMES patients, across each of the 6 muscle groups, muscle contractions was observed in 100 to 103 (86–87%) of the 118 NMES sessions.

Our primary outcome ascertainment rate for assessable patients was 100%. Across all 34 patients, we were unable to record the primary outcome in 5 patients due to death (NMES = 3, Sham=1) or persistent metabolic encephalopathy (NMES=1). A total of 29 patients (12 NMES, 17 Sham) contributed to the primary outcome assessment. There were no significant differences in the mean (SD) elapsed time between enrollment and outcome measure assessment between the NMES versus sham groups at awakening (7.5 (7.9) versus 5.9 (4.3) days, p=0.545), ICU discharge (17.7(18.9) versus 19.4 (20.4), p=0.823), or hospital discharge (26.8 (20.9) versus 27.7 (18.1), p=0.905). Two patients, both randomized to the Sham group, died after primary outcome assessment and before hospital discharge. There was no significant difference in the primary outcome of mean (SD) lower extremity muscle strength between the NMES versus Sham groups at hospital discharge (28 (2) versus 27 (3), p=0.072), with a mean (95% CI) increase in muscle strength of 1.8 (0.35, 3.90).

Of the secondary outcomes (Tables 3 and 4), in the NMES versus sham group, there was a significantly greater mean (SD) increase in lower extremity strength from awakening to ICU discharge (5.3 (5.9), N=10 versus 0.8 (3.8), N=11; p=0.047) and from awakening to hospital discharge (5.7 (5.1), N=12 versus 1.8 (2.7), N=15; p=0.019). Patients in the NMES versus Sham group also walked farther at hospital discharge (mean (SD) 514 (389) feet, N=12 versus 251 (210) feet, N=17; p=0.050), but this difference was not statistically significant at ICU discharge (mean (SD) 216 (343) feet, N=12 versus 90 (121) feet, N=14; p=0.213). There were no significant differences between groups in other secondary outcome measures (Tables 3 and 4). Among our post-hoc analyses, the change in FSS-ICU score from ICU awakening to ICU discharge was significantly greater in the NMES group (mean (SD) change: 11.4 (6.2) versus Sham 4.3 (5.6; p=0.019); however, there were no between-group differences from ICU awakening to hospital discharge. Other differences were not statistically significant (Table 5).

Table 3.

Physical Assessments at ICU Awakening, ICU Discharge, and Hospital Dischargea

| ICU Awakeningb | ICU Dischargec | Hospital Discharged |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NMES | Sham | p- value |

NMES | Sham | p- value |

NMES | Sham | p- value |

|

| Primary lower extremity MRC strengthd,e | 23 (6) | 25 (5) | 0.271 | 27 (23) | 25 (4) | 0.139 | 28 (2) | 27 (3) | 0.072 |

| Overall MRC scoref | 42 (10) | 45 (11) | 0.374 | 49 (6) | 48 (8) | 0.982 | 53 (4) | 50 (7) | 0.141 |

| MRC score <48, n (%) | 8 (67) | 5 (33) | 0.128 | 3 (25) | 4 (25) | 1.000 | 1 (8) | 5 (29) | 0.354 |

| Handheld dynamometryg | |||||||||

| Tibialis anterior | 18 (11) | 16 (9) | 0.874 | 21 (10) | 19 (9) | 0.627 | 20 (8) | 19 (16) | 0.909 |

| Gastrocnemius | 25 (16) | 32 (12) | 0.309 | 31 (17) | 39 (10) | 0.272 | 36 (17) | 31 (14) | 0.473 |

| Quadriceps | 23 (11) | 23 (12) | 0.982 | 28 (14) | 33 (14) | 0.458 | 33 (14) | 30 (16) | 0.649 |

| Hand grip strength, % predicted | 28 (28) | 39 (43) | 0.472 | 34 (26) | 41 (42) | 0.616 | 46 (25) | 40 (28) | 0.565 |

| Hand grip strength (kg) | 7.5 (7.5) | 10.5 (10.0) | 0.421 | 9.4 (7.2) | 11.5 (9.4) | 0.522 | 12.7 (6.4) | 12.7 (9.0) | 0.998 |

| Maximal inspiratory pressure, % predicted | 43 (NA) | 37 (12) | 0.756 | 61 (16) | 51 (37) | 0.688 | 61 (16) | 51 (37) | 0.688 |

| FSS-ICU | 12 (8) | 13 (6) | 0.503 | 20 (10) | 19 (6) | 0.897 | 30 (7) | 26 (8) | 0.140 |

| Maximum walked distance (feet) | 64 (123) | 29 (97) | 0.458 | 216 (343)h | 90 (121) | 0.250 | 514 (389)h | 251 (210) | 0.050 |

| Number of Independent ADLs | 0 (0) | 0.1 (0.5) | 0.410 | 1.2 (1.8) | 0.9 (1.7) | 0.728 | 4.0 (2.3) | 2.4 (2.6) | 0.101 |

Abbreviations: NA, Not applicable; NMES, neuromuscular electrical stimulation; MRC, Medical Research Council; ICU, Intensive Care Unit; FSS-ICU = Functional Status Score for the ICU; ADL, Activities of Daily Living

Unless otherwise specified, mean (SD) are presented. When only a single value was available, no standard deviation could be calculated and “NA” was presented instead of SD.

Sample size for assessments performed at ICU Awakening, by NMES (n=12) and sham (N=17) groups, respectively: MRC score of lower extremity, Overall MRC scores, and MRC score <48, 12 and 15; Hand held dynamometry, tibialis anterior, and gastrocnemius, 6 and 9; quadriceps, 11 and 14; hand grip strength, 11 and 15; maximal inspiratory pressure, 1 and 3; FSS-ICU, 12 and 17; Maximum walking distance, 9 and 13; number of independent ADLs, 10 and 14.

Sample size for assessments performed at ICU Discharge, by NMES (n=12) and sham groups (n=16), respectively: MRC score of lower extremity, Overall MRC scores, and MRC score <48, 12 and 16; Hand held dynamometry, tibialis anterior, 8 and 12, gastrocnemius, 8 and 11; quadriceps, 11 and 13; hand grip strength, 12 and 15; maximal inspiratory pressure, 3 and 3; FSS-ICU, 12 and 15; Maximum walking distance, 12 and 14; number of independent ADLs, 12 and 13.

Sample size for assessments performed at Hospital Discharge, by NMES (n=12) and sham groups (n=17), respectively: MRC score of lower extremity, Overall MRC scores, and MRC score <48, 12 and 17; Hand held dynamometry, tibialis anterior and gastrocnemius, 9 and 12; quadriceps, 11 and 15; hand grip strength, 12 and 16; maximal inspiratory pressure, 3 and 4; FSS-ICU, 12 and 16; Maximum walking distance, 12 and 16; number of independent ADLs, 12 and 17.

Includes knee extension, ankle plantar flexion, and ankle dorsiflexion. Patient positioning for evaluation conducted as per American Spinal Injury Association[32] using the Medical Research Council Score in which the patient exerts a force against the examiner’s resistance. Each muscle assessed on a 6-point MRC scale (0=no contraction; 5=contraction sustained against maximal resistance).

includes shoulder abduction, elbow flexion, wrist extension, hip flexion, knee extension, ankle dorsiflexion.[33]

Hand held dynamometry (HHD) uses a small device that fits into the palm of the examiner’s hand, and quantifies force on a continuous scale when the patient’s extremity pushes against the HHD device during a standardized physical exam. Results are the combined average of left and right muscle groups, measured in pounds.

At ICU and hospital discharge, respectively,1 and 3 patients in the NMES group reached the maximum walking distance of 1000 feet

Table 4.

ICU and Hospital Outcomesa

| NMESa (n=16) |

Sham (n=18) |

p- value |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean increase in primary lower extremity MRC strength – awakening to ICU dischargeb,c | 5.3 (5.9) | 0.8 (3.8) | 0.047 |

| Mean increase in primary lower extremity MRC strength – awakening to hospital dischargeb,c | 5.7 (5.1) | 1.8 (2.7) | 0.019 |

| Duration of mechanical ventilation (days) | 20 (18) | 16 (15) | 0.492 |

| Ever re-admitted to ICU, n (%) | 3 (19) | 5 (27) | 0.693 |

| ICU mortality | 3 (19) | 1 (5) | 0.323 |

| Hospital mortality | 3 (19) | 3 (17) | 1.000 |

| ICU length of stay (days) | 22 (17) | 20 (17) | 0.722 |

| Hospital length of stay (days) | 36 (22) | 35 (20) | 0.850 |

| Hospital charges (US dollars) | 163,159 (117,730) | 152,968 (88,683) | 0.776 |

| Hospital disposition for survivors, n (%) | |||

| Home | 5 (38) | 8 (53) | 0.251 |

| Acute rehabilitation | 4 (31) | 6 (40) | |

| Otherd | 4 (31) | 1 (7) |

Abbreviations: NMES, neuromuscular electrical stimulation; MRC, Medical Research Council; ICU, Intensive Care Unit

Unless otherwise specified, mean (SD) are presented

Sample sizes for mean change lower extremity MRC, by NMES and sham groups, respectively: awakening to ICU discharge, 10 and 11; awakening to hospital discharge, 12 and 15

Includes knee extension, ankle plantar flexion, and ankle dorsiflexion. Patient positioning for evaluation conducted as per American Spinal Injury Association[32] using the Medical Research Council Score in which the patient exerts a force against the examiner’s resistance. Each muscle assessed on a 6-point MRC scale (0=no contraction; 5=contraction sustained against maximal resistance).

Other includes sub-acute rehabilitation, long-term ventilator facility, or nursing home

Table 5.

Post-hoc Analyses of Physical Assessment Change Scores

| ICU Awakening to ICU Dischargea |

ICU Awakening to Hospital Dischargeb |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NMES | Sham | p-value | NMES | Sham | p-value | |

| Hand grip strength, % predicted | 0.07 (0.2) | 0.02 (0.1) | 0.545 | 0.15 (0.2) | −0.02(0.3) | 0.134 |

| FSS-ICU | 11 (6) | 4 (6) | 0.019 | 21 (10) | 16 (9) | 0.207 |

| Maximum walking distance (feet) | 164 (259) | 40 (71) | 0.280 | 401 (394) | 192 (187) | 0.230 |

Abbreviations: NMES, neuromuscular electrical stimulation; ICU, Intensive Care Unit; FSS-ICU = Functional Status Score for the ICU

Sample size for change score between ICU awakening and ICU discharge, by NMES and sham groups, respectively: hand grip strength, 9 and 8; FSS-ICU, 10 and 9; Maximum walking distance, 7 and 6.

Sample size for change score between ICU awakening and hospital discharge, by NMES and sham groups, respectively: hand grip strength, 9 and 12; FSS-ICU, 10 and 13; Maximum walking distance, 7 and 10.

Discussion

In this single-center, multi-ICU pilot randomized trial of 34 mechanically ventilated patients randomly assigned to NMES versus Sham intervention, there was no significant difference in lower extremity muscle strength at hospital discharge, measured by outcome assessors blinded to treatment allocation. However, this trial was discontinued before reaching our pre-specified sample size (54 patients) due to slow recruitment and the end of funding, which may make this study underpowered to detect a true difference between groups. Among a priori secondary outcome analyses, patients receiving NMES had a larger increase in lower extremity muscle strength between ICU awakening and ICU discharge, and between ICU awakening and hospital discharge, and walked more than 2 times farther at hospital discharge.

Our study provides further evidence on the physical disability and in-hospital recovery experienced by ICU survivors. As a cohort, at ICU awakening, 48% (13/27) of evaluable patients had muscle strength scores consistent with ICU-acquired weakness (<48/60, Table 3). Of 28 hospital survivors, 46% were discharged home, 36% transferred to acute rehabilitation, and the remainder discharged to a nursing home, sub-acute rehabilitation, or a long-term ventilation facility. Compared to their almost-perfect, baseline score (Table 1), patients’ mean FSS-ICU physical function score at ICU awakening was reduced by >50% (Table 3), with improvement at ICU and hospital discharge, but still not at baseline levels by hospital discharge. These repeated FSS-ICU scores are similar to those of a separate cohort of medical ICU patients.[40]

Of the 5 parallel group RCTs of NMES identified in 3 systematic reviews,[18–20] 3 reported strength or function outcomes,[21, 22, 43] and of these, only 1 started NMES within the first week of ICU admission.[22] In one of the largest RCTs to date, 52 evaluable patients received 55 minutes of NMES versus a non-sham control within 2 days of ICU admission. The primary outcome was an unblinded assessment of ICU-acquired weakness (MRC score <48) at ICU awakening.[22] Compared to our pilot RCT, patients enrolled in this prior study had a lower severity of illness (mean APACHE II of 18 vs. 25) and a shorter mean ICU length of stay (NMES= 14, Control= 22 days in prior study). In this prior study, fewer patients receiving NMES had ICU-acquired weakness at ICU awakening (NMES = 3/24 (13%); Control=11/28 (39%); odds ratio and 95% (CI) = 0.22 [0.05 to 0.92], p=0.04).[22]. In contrast, our smaller-sized study did not identify a statistically significant difference in ICU-acquired weakness between NMES and sham groups (at ICU awakening: 67% versus 33%, p=0.128, and at ICU discharge: 25% vs. 25%, p=1.000; Table 3). However, our study was not powered to detect a difference in ICU-acquired weakness.

In contrast to previous RCTs, we identified no significant differences in lower extremity or whole body muscle strength between NMES and Sham groups at ICU awakening, ICU discharge, or hospital discharge. Of 3 parallel-group RCTs reporting strength measures, those receiving NMES consistently had higher strength than controls as observed in our study.[21, 43, 44] Of these 3 studies, only 1 conducted NMES solely in the ICU and measured strength at ICU awakening.[44] Differences in patient population, study intervention and outcome measures, could account for these differences across studies. The remaining studies occurred in patients with COPD exacerbations[43] or patients receiving mechanical ventilation >30 days;[21] 1 study started NMES 12 days after ICU admission and measured strength at 6 weeks,[43] and the other started NMES after at least 4 weeks in the ICU, measuring strength 4 weeks later.[21] Finally, none of these studies used the same strength measurement protocol, which may also account for differences in results from our study.[21, 43]

Two RCTs studied NMEs in patients with sepsis, with discordant results.[45, 46] In these studies, investigators randomized NMES within patients (i.e., allocated to NMES to one side of the body). Results varied by outcome measure. For example, Poulsen et al., identified no difference in the volume of quadriceps muscle by CT scan,[45] whereas Rodriguez et al. identified significant differences in arm and leg strength measured by manual muscle testing, favoring patients receiving NMES.[46] Since NMES has a microcirculatory effect,[47] and may have systemic effects within patients, further RCTs in septic patients would be valuable.

Our pilot study has strengths. We included serial measures of strength and function and completed the primary outcomes assessment on all assessable patients at hospital discharge. We also used a Sham control group, concealed treatment allocation, and blinded caregivers and outcome assessors. We reported our research according to CONSORT standards for non-pharmacological RCTs.[48] We optimized the fidelity of the intervention and outcomes assessments by delivering interactive training sessions, developing training materials, and conducting quality assurance audits for personnel delivering research sessions and for outcomes assessors.[48]

Our pilot study also has limitations. First, our sample size calculation was based on a mean (SD) estimate for Sham group lower extremity strength score at hospital discharge of 21.3 (6.8) (maximum score = 30) which was much lower than actually observed (27 (3)) in the pilot trial. Our control group was stronger than expected, which may be due to increases in providing early rehabilitation in the ICU that enrolled the most patients during our study.[8, 49] This issue represents a common challenge for the design and conduct of rehabilitation trials in the ICU as “usual care” changes over time.[50] Second, patients did not receive all NMES sessions due to pre-screening safety criteria, receiving a mean (SD) of 9 (8.7) NMES sessions, 4.6 days after ICU admission, over a mean (SD) 22 (17) day ICU stay. There was no difference in the number of sessions between the NMES and Sham groups. Our intervention delivery of this intervention occurred less frequently than in 2 prior positive RCTs of ICU-based rehabilitation.[6, 9] Patients in an in-bed cycling study enrolled after a mean of 14 days, received the intervention a median [IQR] of 7 [4, 11] sessions and had a median [IQR] 11 [5, 21] day ICU stay post-enrollment. Patients in a study of early occupational and physical therapy received the intervention on 87% of days and were initiated within 1.5 days of intubation.[6]

The optimal NMES settings are unknown; indeed, within the 3 systematic reviews of ICU research, all studies used different NMES settings.[18–20] We did not include any mechanistic evaluations of the effects of NMES, electrophysiologic measures of muscle or nerve function, or histological evaluations of muscle. We did not achieve our pre-planned sample size, and were underpowered for evaluating our primary outcome. Moreover, significant differences between NMES and Sham groups for secondary outcomes (e.g., change in lower extremity muscle strength scores and walking distance at hospital discharge) may have occurred due to chance and require further prospective study. Finally, we included a measure of impairment (muscle strength) as our primary outcome, rather than a functional outcome (e.g., 6-minute walk test) because we were interested in whether NMES improved muscle strength, a measure of impairment, rather than function. Recent studies highlighted weak correlation between strength and functional measures in ICU survivors.[6, 9, 51] Within critical care medicine, greater evaluation is needed to better understand and then standardize outcome measures.[52, 53] As the study of critical care rehabilitation interventions matures, we suggest rigorous evaluation of additional types of outcomes for measures of body structure and function (e.g., muscle ultrasound) and activity (e.g., frailty, 5 times sit to stand, timed up and go test) to measure patients’ responses to treatment interventions.[52–55]

Conclusions

In this pilot randomized trial with blinded outcomes assessment, NMES in critically ill, mechanically ventilated patients did not significantly improve leg strength at hospital discharge. Because our trial stopped early due to slow recruitment and the end of funding, we may be underpowered to detect a true difference between groups. Among a priori secondary outcomes, NMES versus Sham patients had a significantly greater mean walking distance and change in muscle strength at hospital discharge. These significant improvements in secondary outcomes require investigation in future research.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the following people for their contributions to the development and execution of our pilot study (in alphabetical order): Gadi Alon, PT, PhD; Lora Clawson, MSN, CRNP; Steven Crandall, PT, DPT; Fern Dickman, BS, MPH; Victor Dinglas, BS, MPH; Kareem Fakhoury; Eddy Fan, MD, PhD; Dorianne R Feldman, MSPT, MD; Radha Korupoulu, MBBS, MS; Robert Martin, BA; Rasha Nusr, MBBS, MPH; Karen Oakjones-Burgess, RN; Jessica Rossi, PT, DPT; Kristin Sepulveda, BA; Cynthia Penfold, PT, DPT; Kyle Schneck, BA; Julie Skrzat, PT, DPT; Amy Toonstra, PT, DPT; Amy Wozniak, MS; Rachel Woloszyn, PT, DPT; Nicole Yare, PT, DPT.

Source of Funding: Michelle Kho was funded by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Fellowship Award and Bisby Prize; she currently holds a Canada Research Chair in Critical Care Rehabilitation and Knowledge Translation. Alexander Truong received support from the National Institutes of Health (grant number T32HL007534-31). Blinded outcomes assessments were funded through grant # UL1 RR 025005 from the National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health (NIH). Care Rehab Products (McLean, VA) provided NMES machines for use during the study. The CIHR, NIH, and Care Rehab Products had no role in the design, conduct, or planned statistical analysis of the study and had no influence on the analysis, interpretation, or decision to submit this study for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

This research was conducted at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD.

Conflicts of Interest:

For the remaining authors, no conflicts of interest or source of funding were declared.

References

- 1.Barnato AE, Albert SM, Angus DC, Lave JR, Degenholtz HB. Disability among elderly survivors of mechanical ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:1037–1042. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201002-0301OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bienvenu OJ, Colantuoni E, Mendez-Tellez PA, Dinglas VD, Shanholtz C, Husain N, et al. Depressive symptoms and impaired physical function after acute lung injury: a 2-year longitudinal study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:517–524. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201103-0503OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herridge MS, Tansey CM, Matte A, Tomlinson G, Diaz-Granados N, Cooper A, et al. Functional disability 5 years after acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1293–1304. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iwashyna TJ, Ely EW, Smith DM, Langa KM. Long-term cognitive impairment and functional disability among survivors of severe sepsis. JAMA. 2010;304:1787–1794. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spragg RG, Bernard GR, Checkley W, Curtis JR, Gajic O, Guyatt G, et al. Beyond mortality: future clinical research in acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181:1121–1127. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201001-0024WS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schweickert WD, Pohlman MC, Pohlman AS, Nigos C, Pawlik AJ, Esbrook CL, et al. Early physical and occupational therapy in mechanically ventilated, critically ill patients: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;373:1874–1882. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60658-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lord RK, Mayhew CR, Korupolu R, Mantheiy EC, Friedman MA, Palmer JB, et al. ICU Early Physical Rehabilitation Programs: Financial Modeling of Cost Savings. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:717–724. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182711de2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Needham DM, Korupolu R, Zanni JM, Pradhan P, Colantuoni E, Palmer JB, et al. Early physical medicine and rehabilitation for patients with acute respiratory failure: a quality improvement project. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;91:536–542. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burtin C, Clerckx B, Robbeets C, Ferdinande P, Langer D, Troosters T, et al. Early exercise in critically ill patients enhances short-term functional recovery. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:2499–2505. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181a38937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morris PE, Goad A, Thompson C, Taylor K, Harry B, Passmore L, et al. Early intensive care unit mobility therapy in the treatment of acute respiratory failure. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:2238–2243. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318180b90e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li Z, Peng X, Zhu B, Zhang Y, Xi X. Active mobilization for mechanically ventilated patients: a systematic review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;94:551–561. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2012.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Puthucheary ZA, Rawal J, McPhail M, Connolly B, Ratnayake G, Chan P, et al. Acute skeletal muscle wasting in critical illness. JAMA. 2013;310:1591–1600. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.278481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fan E, Dowdy DW, Colantuoni E, Mendez-Tellez PA, Sevransky JE, Shanholtz C, et al. Physical complications in acute lung injury survivors: a 2-year longitudinal prospective study. Crit Care Med. 2014;42:849–859. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hultman E, Sjoholm H, Jaderholm-Ek I, Krynicki J. Evaluation of methods for electrical stimulation of human skeletal muscle in situ. Pflugers Arch. 1983;398:139–141. doi: 10.1007/BF00581062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bax L, Staes F, Verhagen A. Does neuromuscular electrical stimulation strengthen the quadriceps femoris? A systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Sports Med. 2005;35:191–212. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200535030-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hainaut K, Duchateau J. Neuromuscular electrical stimulation and voluntary exercise. Sports Med. 1992;14:100–113. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199214020-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sillen MJ, Speksnijder CM, Eterman RM, Janssen PP, Wagers SS, Wouters EF, et al. Effects of neuromuscular electrical stimulation of muscles of ambulation in patients with chronic heart failure or COPD: a systematic review of the English-language literature. Chest. 2009;136:44–61. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-2481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williams N, Flynn M. A review of the efficacy of neuromuscular electrical stimulation in critically ill patients. Physiotherapy theory and practice. 2014;30:6–11. doi: 10.3109/09593985.2013.811567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maffiuletti NA, Roig M, Karatzanos E, Nanas S. Neuromuscular electrical stimulation for preventing skeletal-muscle weakness and wasting in critically ill patients: a systematic review. BMC medicine. 2013;11:137. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parry SM, Berney S, Granger CL, Koopman R, El-Ansary D, Denehy L. Electrical Muscle Stimulation in the Intensive Care Setting: A Systematic Review. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:2406–2418. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182923642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zanotti E, Felicetti G, Maini M, Fracchia C. Peripheral muscle strength training in bed-bound patients with COPD receiving mechanical ventilation: effect of electrical stimulation. Chest. 2003;124:292–296. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.1.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Routsi C, Gerovasili V, Vasileiadis I, Karatzanos E, Pitsolis T, Tripodaki E, et al. Electrical muscle stimulation prevents critical illness polyneuromyopathy: a randomized parallel intervention trial. Crit Care. 2010;14:R74. doi: 10.1186/cc8987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arnold DM, Burns KE, Adhikari NK, Kho ME, Meade MO, Cook DJ. The design and interpretation of pilot trials in clinical research in critical care. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:S69–S74. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181920e33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Foster D, Cook D, Granton J, Steinberg M, Marshall J. Use of a screen log to audit patient recruitment into multiple randomized trials in the intensive care unit. Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:867–871. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200003000-00042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Doig GS, Simpson F. Randomization and allocation concealment: a practical guide for researchers. J Crit Care. 2005;20:187–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2005.04.005. discussion 91–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sricharoenchai T, Parker AM, Zanni JM, Nelliot A, Dinglas VD, Needham DM. Safety of physical therapy interventions in critically ill patients: A single-center prospective evaluation of 1110 intensive care unit admissions. J Crit Care. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2013.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baker LL, Wederich CL, McNeal DR, Newsam C, Waters RL. Neuro Muscular Electrical Stimulation: A Practical Guide. 4th ed. Downey, CA: Los Amigos Research & Education Institute; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bourjeily-Habr G, Rochester CL, Palermo F, Snyder P, Mohsenin V. Randomised controlled trial of transcutaneous electrical muscle stimulation of the lower extremities in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2002;57:1045–1049. doi: 10.1136/thorax.57.12.1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vivodtzev I, Pepin JL, Vottero G, Mayer V, Porsin B, Levy P, et al. Improvement in quadriceps strength and dyspnea in daily tasks after 1 month of electrical stimulation in severely deconditioned and malnourished COPD. Chest. 2006;129:1540–1548. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.6.1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gelinas C, Fortier M, Viens C, Fillion L, Puntillo K. Pain assessment and management in critically ill intubated patients: a retrospective study. Am J Crit Care. 2004;13:126–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hamill-Ruth RJ, Marohn ML. Evaluation of pain in the critically ill patient. Crit Care Clin. 1999;15:35–54. v–vi. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0704(05)70038-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.American Spinal Injury Association. Chapter III: Neurological Assessment: the Motor Examination. Reference Manual for the International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury: American Spinal Injury Association. 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 33.De Jonghe B, Sharshar T, Lefaucheur JP, Authier FJ, Durand-Zaleski I, Boussarsar M, et al. Paresis acquired in the intensive care unit: a prospective multicenter study. JAMA. 2002;288:2859–2867. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.22.2859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kleyweg RP, van der Meche FG, Schmitz PI. Interobserver agreement in the assessment of muscle strength and functional abilities in Guillain-Barre syndrome. Muscle Nerve. 1991;14:1103–1109. doi: 10.1002/mus.880141111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.American Spinal Injury Association. Motor Exam Guide. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vanpee G, Segers J, Van Mechelen H, Wouters P, Van den Berghe G, Hermans G, et al. The interobserver agreement of handheld dynamometry for muscle strength assessment in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:1929–1934. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31821f050b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baldwin CE, Paratz JD, Bersten AD. Muscle strength assessment in critically ill patients with handheld dynamometry: An investigation of reliability, minimal detectable change, and time to peak force generation. J Crit Care. 2013;28:77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ali NA, O'Brien JM, Jr, Hoffmann SP, Phillips G, Garland A, Finley JC, et al. Acquired weakness, handgrip strength, and mortality in critically ill patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:261–268. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200712-1829OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory S. ATS/ERS Statement on respiratory muscle testing. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:518–624. doi: 10.1164/rccm.166.4.518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zanni JM, Korupolu R, Fan E, Pradhan P, Janjua K, Palmer JB, et al. Rehabilitation therapy and outcomes in acute respiratory failure: an observational pilot project. J Crit Care. 2010;25:254–262. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2009.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kho ME, Truong AD, Brower RG, Palmer JB, Fan E, Zanni JM, et al. Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation for Intensive Care Unit-Acquired Weakness: Protocol and Methodological Implications for a Randomized, Sham-Controlled, Phase II Trial. Phys Ther. 2012;92:1564–1579. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20110437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.de Winter JCF. Using the Student’s t-test with extremely small sample sizes. Practical Assessment, Research, & Evaluation. 2013;18:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Abdellaoui A, Prefaut C, Gouzi F, Couillard A, Coisy-Quivy M, Hugon G, et al. Skeletal muscle effects of electrostimulation after COPD exacerbation: a pilot study. Eur Respir J. 2011;38:781–788. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00167110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Karatzanos E, Gerovasili V, Zervakis D, Tripodaki ES, Apostolou K, Vasileiadis I, et al. Electrical muscle stimulation: an effective form of exercise and early mobilization to preserve muscle strength in critically ill patients. Crit Care Res Pract. 2012;2012:432752. doi: 10.1155/2012/432752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Poulsen JB, Moller K, Jensen CV, Weisdorf S, Kehlet H, Perner A. Effect of transcutaneous electrical muscle stimulation on muscle volume in patients with septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:456–461. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318205c7bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rodriguez PO, Setten M, Maskin LP, Bonelli I, Vidomlansky SR, Attie S, et al. Muscle weakness in septic patients requiring mechanical ventilation: Protective effect of transcutaneous neuromuscular electrical stimulation. J Crit Care. 2011;27(319):e1–e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2011.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gerovasili V, Tripodaki E, Karatzanos E, Pitsolis T, Markaki V, Zervakis D, et al. Short-term systemic effect of electrical muscle stimulation in critically ill patients. Chest. 2009;136:1249–1256. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-2888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Boutron I, Moher D, Altman DG, Schulz KF, Ravaud P. Extending the CONSORT statement to randomized trials of nonpharmacologic treatment: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:295–309. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-4-200802190-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Needham DM, Korupolu R. Rehabilitation quality improvement in an intensive care unit setting: implementation of a quality improvement model. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2010;17:271–281. doi: 10.1310/tsr1704-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Parker A, Tehranchi KM, Needham DM. Critical care rehabilitation trials: the importance of 'usual care'. Crit Care. 2013;17:R183. doi: 10.1186/cc12884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Needham DM, Wozniak AW, Hough CL, Morris PE, Dinglas VD, Jackson JC, et al. Risk factors for physical impairment after acute lung injury in a national, multicenter study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189:1214–1224. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201401-0158OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Needham DM. Understanding and improving clinical trial outcome measures in acute respiratory failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189:875–877. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201402-0362ED. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Turnbull AE, Parker AM, Needham DM. Supporting small steps toward big innovations: the importance of rigorous pilot studies in critical care. J Crit Care. 2014;29:669–670. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2014.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tipping CJ, Young PJ, Romero L, Saxena MK, Dulhunty J, Hodgson CL. A systematic review of measurements of physical function in critically ill adults. Crit Care Resusc. 2012;14:302–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Young P, Hodgson C, Dulhunty J, Saxena M, Bailey M, Bellomo R, et al. End points for phase II trials in intensive care: recommendations from the Australian and New Zealand Clinical Trials Group consensus panel meeting. Crit Care Resusc. 2012;14:211–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Groll DL, To T, Bombardier C, Wright JG. The development of a comorbidity index with physical function as the outcome. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58:595–602. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Heyland DK, Groll D, Caeser M. Survivors of acute respiratory distress syndrome: relationship between pulmonary dysfunction and long-term health-related quality of life. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:1549–1556. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000168609.98847.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW. Studies of Illness in the Aged. The Index of Adl: A Standardized Measure of Biological and Psychosocial Function. JAMA. 1963;185:914–919. doi: 10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9:179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, Zimmerman JE. APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med. 1985;13:818–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vincent JL, Moreno R, Takala J, Willatts S, De Mendonca A, Bruining H, et al. The SOFA (Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. On behalf of the Working Group on Sepsis-Related Problems of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med. 1996;22:707–710. doi: 10.1007/BF01709751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]