Extended case

An 85-year-old woman was admitted to the hospital with a one-week history of fatigue and progressive dyspnoea. In the prior months she had lost a considerable amount of weight (10 kg). The general practitioner diagnosed a urinary tract infection. On physical examination we found rapid irregular heart tones without any murmurs, some crackles in the lungs and oedema in the lower extremities. The ECG showed atrial fibrillation with a ventricular response of 160 beats/min, with a normal QRS duration and ST segments. Laboratory tests showed a BNP of 1130 ng/l (normal <100 ng/l) and a CRP of 160 mg/l (normal <7 mg/l). Urine analysis was positive for erythrocytes and leukocytes, which confirmed the diagnosis of urinary tract infection. Chest X-ray showed cardiomegaly (cor-thorax ratio = 0.8), bilateral intrapulmonary consolidation, left-sided pleural effusion and a mass in the lung close to the left hilus. CT-thorax showed bilateral intrapulmonary consolidation in the lower lung fields, pericardial and pleural effusion and a 5 cm cyst in the lung, left and ventral of the mediastinum close to the left hilus (Fig. 1). Transthoracic echocardiography showed a non-dilated, normal functioning left and right ventricle with thickened pericardium and pericardial effusion (10 mm). Remarkable was a mass in the free wall of the right ventricular outflow tract, with a long intracardial mobile structure reaching up to the pulmonary valve (Fig. 2). Despite optimal medical therapy the patient died of respiratory insufficiency 1 day later, before a definite diagnosis was made.

Fig. 1.

CT-thorax showing bilateral intrapulmonary consolidation, pericardial and pleural effusion and a 5 cm wide cyst in the lung left and ventral of the mediastinum close to the left hilus

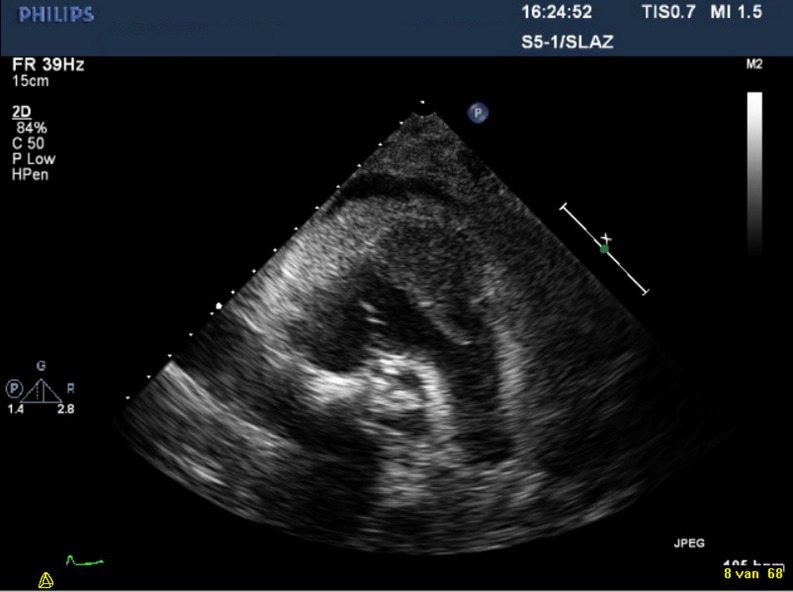

Fig. 2.

Transthoracic echocardiography which shows a non-dilated good functioning left and right ventricle with thickened pericardium (10 mm) and pericardial effusion (10 mm). A mass in the free wall of right ventricular outflow tract is visible, with a long intracardial mobile structure reaching up to the pulmonary valve

Autopsy

In the posterior wall of the urinary bladder a poorly differentiated transitional cell carcinoma (TCC) with a diameter of 4 cm was found. In the lungs bilateral diffuse metastatic carcinoma was seen, as well as lymphangitis carcinomatosa. The heart showed extended pericarditis and sanguinolent pericardial effusion. In the right ventricle and in the right atrium there was a tumour in the muscular layer with a diameter of 4 cm (Figs. 3 and 4). There were neither signs of valvular heart disease nor important coronary sclerosis. The right coronary artery disappeared in the tumour. There was a 5 cm wide cystic lesion in the anterior mediastinum, adjacent to the left lung and the large blood vessels, histologically a WHO type A thymoma (with cystic change).

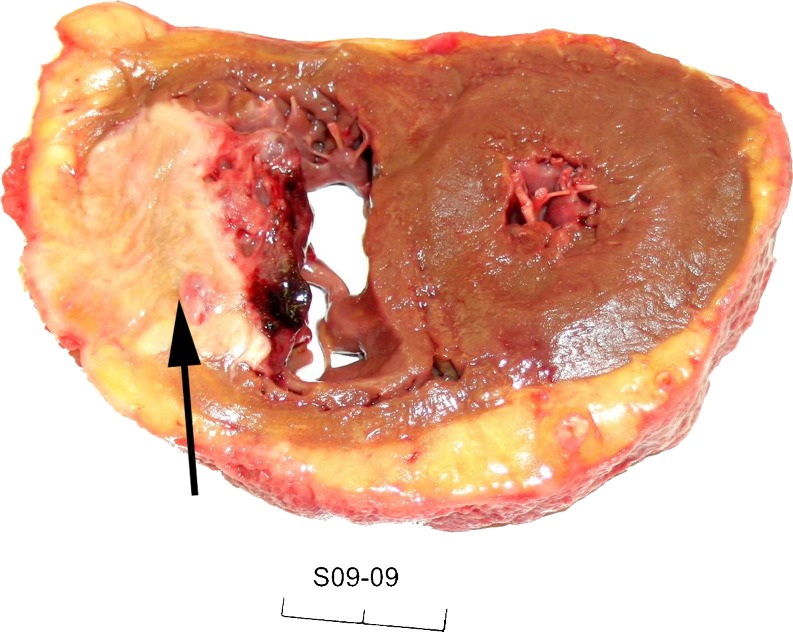

Fig. 3.

Macroscopic image of a transverse section of the heart showing a white metastatic tumour mass in the right ventricle (arrow)

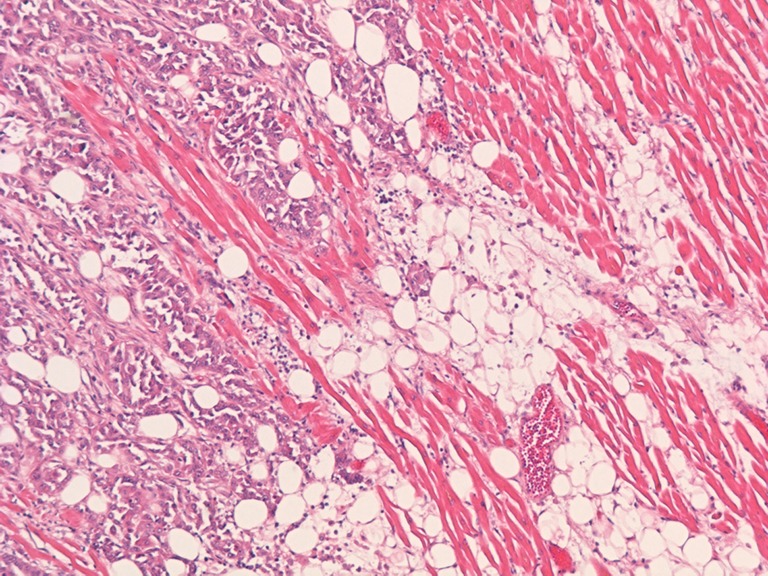

Fig. 4.

Microscopic image (5× objective). Histology of the metastatic tumour mass illustrating polymorphic tumour cells infiltrating between cardiac muscle cells and fatty tissue of the right ventricle

Discussion

Primary tumours of the heart are rare; metastatic heart tumours, however, are far more common. The first to describe metastases to the heart was Boneti in 1700 [1]. Subsequent reports describe cardiac metastases from almost every organ of the body. Cardiac metastases are found in up to 25% of post-mortem patients who have died of malignancies [1–3]. Despite their frequency, metastatic heart tumours only rarely gain clinical attention, because most tumours are small and people have already died before the metastases in the heart are found. Metastases primarily occur in the sixth or seventh decade of life [3]. In decreasing order cardiac metastases affect the pericardium, the myocardium or the endocardium and may cause pericardial effusion, atrial or ventricular arrhythmias, conduction defects, heart failure or imitate valvular disease. Metastases may reach the heart via the lymphatic or haematogeneous route, or by direct extension [3]. Haematogeneous spread usually causes right-sided cardiac tumour growth. Tumours with relatively frequent cardiac metastases are in descending order: carcinomas of the lung, the breast and the oesophagus, malignant lymphoma, leukaemia, and malignant melanoma [4]. Only a few cases of symptomatic cardiac metastasis from TCC of the bladder have been reported [2, 4–6]. This case comprises a TCC of the bladder, most likely haematogenously spread to the right ventricle of the heart, where it produced a large tumour mass from the endocardium through the muscular layer to the pericardium, which gave subsequent pericarditis with pericardial effusion and thickening. Dyspnoea due to atrial fibrillation with a high ventricular response was the first expression of the TCC that gained clinical attention. This is unusual, as normally when cardiac symptoms arise they are overshadowed by the primary disease. This tumour, 4 cm in diameter, was protruding into the right ventricular cavity and a fibrinous string extended into the right ventricular outflow tract. This means there was also a serious risk of developing right ventricular outflow tract obstruction or pulmonary emboli in the near future. This case is a good example of the fact that all malignant cardiac tumours are rapidly fatal and palliation is usually the only therapeutic option [7].

References

- 1.Hanfling SM. Metastatic cancer to the heart. Review of the literature and report of 127 cases. Circulation. 1960;22:474–83. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.22.3.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klatt EC, Heitz DR. Cardiac metastases. Cancer. 1990;65(6):1456–9. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19900315)65:6<1456::AID-CNCR2820650634>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reynen K, Kockeritz U, Strasser RH. Metastases to the heart. Ann Oncol. 2004;15(3):375–81. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fabozzi SJ, Newton JR, Jr, Moriarty RP, Schellhammer PF. Malignant pericardial effusion as initial solitary site of metastasis from transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. Urology. 1995;45(2):320–2. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(95)80025-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bishwo Man Singh Shrestha M, Bhagwan Koirala MS, Purna Raj Joshi MD, Laxmi Rajbhandari MN. Superior Vena Cava Syndrome Due to Metastatic Transitional Cell Carcinoma. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 2000;8(3):280–2. doi: 10.1177/021849230000800325. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malde DJ, Gall Z, George N. Ventricular rupture secondary to cardiac metastasis of transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2006;40(2):170–1. doi: 10.1080/00365590510040372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Butany J, Nair V, Naseemuddin A, Nair GM, Catton C, Yau T. Cardiac tumours: diagnosis and management. Lancet Oncology. 2005;6(4):219–28. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70093-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]