Abstract

Background & Aims

The availability of potent, well-tolerated oral antivirals with low rates of resistance has led many experts to recommend liberalizing indications for treatment of chronic hepatitis B (CHB). This study sought to determine the rate of transitions to an active phase of infection, the frequency of treatment initiation, and the clinical outcomes of patients with CHB who did not meet treatment criteria at presentation.

Methods

We reviewed medical records of patients with CHB, seen in the liver clinics at the University of Michigan Health System from 1999 through 2010, who did not receive antiviral treatment within 6 months of presentation. We collected data on transitions between different phases of CHB, hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) seroconversion, loss of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), and development of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Data analyses were censored or truncated at the time of treatment initiation or development of an outcome.

Results

Of the 234 patients analyzed, 52.1% were men (median age, 35 years), 72.2% were Asians, and 81.2% were HBeAg-negative. During a median follow-up of 51 months, 19.2% patients transitioned to a more active disease phase and 18.8% started antiviral therapy. Of the 44 HBeAg-positive patients, 4 patients (9%) had spontaneous HBeAg seroconversion. Nine HBeAg-negative but none of the HBeAg-positive patients lost HBsAg. The cumulative probability of HBsAg loss among HBeAg-negative patients was 1% at year 5 and 21% by year 10. No patients had flares of icteric hepatitis or hepatic decompensation. None of the HBeAg-positive patients developed HCC, whereas 2 HBeAg-negative patients developed HCC.

Conclusion

Careful monitoring of patients with CHB who did not meet treatment criteria at presentation permits timely initiation of treatment, with low risk of adverse clinical outcomes, based on a retrospective study with a median follow-up period of 4.3 years. These findings indicate that current guidelines for initiating treatment appropriate.

Keywords: antiviral agent, cancer, HBV infection, management

Introduction

The availability of potent antiviral drugs with very low rate of antiviral drug resistance makes it possible for almost all patients receiving antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis B (CHB) to achieve virological remission.1, 2 Antiviral therapy is clearly indicated in hepatitis B patients with life threatening liver disease or cirrhosis. For non-cirrhotic patients, guidelines from the American, European and Asian Pacific Liver Associations (AASLD, EASL and APASL) recommend treatment in patients with high levels of serum HBV DNA and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) or histologic evidence of moderate-severe inflammation or fibrosis, and lower thresholds for older patients and patients with family history of HCC.3–5 All guidelines agree that treatment is not required in the immune tolerance (IT) or inactive carrier (IC) phase; however, guidelines differ in HBV and ALT cutoffs for initiating treatment.

Recent studies showed that high serum HBV DNA level is an independent predictor of HCC6, and moderate-severe inflammation or fibrosis can be present in patients with normal ALT.7 Data from these studies led many experts to recommend liberalizing indications for CHB treatment.8, 9 A retrospective study of 369 CHB patients followed for 84 months found that 30%, 30%, 19%, and 30% of patients who died from non-HCC related liver causes, and 33%, 53%, 23%, and 47% of patients who died from HCC would not meet the treatment initiation criteria of 2008 United States (US) algorithm, 2008 APASL, 2009 EASL and 2009 AASLD guidelines, respectively.8 The authors concluded that treatment criteria of these guidelines are too strict; however, 35% of patients in that study had cirrhosis and treatment criteria for cirrhotic patients should have been applied to those patients. Furthermore, treatment indications were solely determined based on assessment at presentation and did not consider guidelines recommendation for monitoring of patients who do not meet treatment criteria such that treatment can be initiated later when liver disease becomes active.

We studied a cohort of CHB patients who were not receiving antiviral treatment to determine the rate of transitions to an active phase of infection and the frequency of treatment initiation during long-term follow-up, and the clinical outcomes of patients who remained untreated.

Methods

Study design

Medical records of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg)-positive patients seen in the liver clinics at the University of Michigan Health System between January 1999 and January 2010 were retrospectively reviewed. Of the 570 CHB patients identified by ICD 9 codes (070.22, 070.30, 070.32, 070.33), 245 patients who did not receive antiviral treatment at presentation or within 6 months of presentation met the study criteria (Supplementary Figure 1). All patients had HBV DNA and ALT monitoring every 3–6 months during the first year and every 6–12 months thereafter. All patients included in this study had at least 2 HBV DNA and 3 ALT measurements during the first year and a median of 4 (range 1–20) HBV DNA and 5 ALT (range 1–27) measurements after the first year. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Patient demographics and family history of HCC at baseline visit, HBV markers (hepatitis B e antigen and antibody [HBeAg and anti-HBe], HBV DNA); hepatic panel, platelet count, prothrombin time/international normalized ratio (INR), liver imaging and liver histology at baseline and at each follow-up visit were recorded. A value of 40 U/L was used to define the upper limit of normal (ULN) for ALT. A secondary analysis was performed with ULN of ALT of 19 for women and 30 for men.

Serum HBV DNA was quantified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays: Amplicor HBV monitor test (Roche Molecular Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) with a lower limit of detection (LLD) of ~40 IU/mL between 2000 and 2005, and real-time PCR assays, COBAS Taqman HBV (Roche Molecular diagnostics) with a LLD of 29–300 IU/mL between 2005 and 2012, and Abbott RealTime HBV Assay (Abbott Molecular Inc. IL) with a LLD of 10 IU/mL from May 2012 onward.

Definitions of phases of chronic HBV infection

Phases of chronic HBV infection at presentation were determined by HBeAg status, serum ALT and HBV DNA levels during the period from 6 months before to 6 months after the first clinic visit. Definitions of phases of chronic HBV infection are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Definitions of phases of chronic HBV infection

| HBV DNA (IU/mL) | ALT (X ULN*) | |

|---|---|---|

| HBeAg-positive patients | ||

| Immune tolerance phase | ≥20,000 | <ULN |

| Mildly active phase | ≥20,000 | 1–2X ULN |

| Immune active phase | ≥20,000 | >2X ULN |

| Low replication phase | <20,000 | Any level of ALT |

| HBeAg-negative patients | ||

| Inactive carrier phase | <2,000 | <ULT |

| Indeterminate phase | <2,000 | >ULN |

| >2,000 | <ULN | |

| Mildly active phase | 2,000–20,000 | >ULN |

| ≥20,000 | 1–2X ULN | |

| Immune active phase | ≥20,000 | >2X ULN |

ULN for ALT is according to the traditional cut-off value of 40 U/L.

Definitions of transitions between phases

Transitions between phases were determined by HBeAg status, serum ALT and HBV DNA levels at follow-up visits. Timing of transitions was defined as the date when that transition first occurred; if the patient fluctuated between different phases, then the date when transition to the last phase first occurred was considered.

Outcome measures

Definitions for outcome measures were: HBeAg seroconversion, loss of HBeAg and detection of anti-HBe in a HBeAg positive patient; HBsAg loss, undetectable serum HBsAg in a patient who was HBsAg positive; Hepatitis flare, an increase in ALT to >5X ULN; Severe hepatitis flare, hepatitis flare with INR >1.5 or total bilirubin >3 mg/dL; Hepatic decompensation, development of ascites, variceal bleeding or hepatic encephalopathy; HCC based on AASLD guidelines.10

Statistical analyses

Data were recorded in Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) database and transferred into SPSS software version 21 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) for analyses.

Continuous variables were expressed as mean±SD or median (range) and compared with two-tailed student t test or Mann-Whitney test. Categorical variables were expressed as number and percent and compared with chi-square or Fisher’s exact test. Cumulative probabilities of transitioning to another phase, HBeAg seroconversion and HBsAg loss were estimated by Kaplan-Meier method and compared by log-rank test. For time- to-event analyses, patients were censored at the time of outcome or treatment initiation. Baseline parameters including age, sex, duration of follow-up, serum ALT, HBV DNA, albumin and platelet count in patients who remained in the same phase versus transitioned to another phase were compared. For patients with ≥3 years follow-up, predicted risk of HCC was assessed using Risk Estimation for Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Chronic Hepatitis B (REACH-B) score which has a range of 0–17 and includes sex, age, ALT, HBeAg status and HBV DNA level at baseline.11

Results

Characteristics of patients at presentation

Of 245 patients who met study criteria, 234 (95.5%) did not meet treatment criteria of AASLD guideline at presentation and were included in this analysis. The remaining 11 patients who met treatment criteria but declined treatment were excluded from the analysis. Eight started treatment after a median of 34.5 months, and none including three who remained untreated developed HCC or hepatic decompensation.

Among the 234 patients included in this analysis, median age was 35 (range 18–82) years, 52.1% were men, and 72.2% were Asians. Majority of the patients (81.2%) were HBeAg negative. Two-thirds of the patients had normal ALT and 67.5% had HBV DNA <20,000 IU/mL. Liver biopsy was available in 33 (14.1%) patients at baseline; 25 had Ishak fibrosis score of 0–1, five had a score of 2, three had a score of 3 (two started antiviral after 12 months, one had HBV DNA 700 IU/mL but marked steatosis), and none had a score >3.

Compared to HBeAg-positive patients, HBeAg-negative patients were older, more likely to be men and to have a longer duration of follow-up. Almost all (91%) HBeAg-positive patients were Asians compared to 76.3% of the HBeAg-negative patients. Median duration of follow up for the entire cohort was 51 (range 12–164) months and was longer in the HBeAg-negative patients than the HBeAg-positive patients, 57.7 vs. 29.1 months, p <0.001. Characteristics of patients at presentation are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Baseline Characteristics of Patients

| HBeAg-positive patients | HBeAg-negative patients | Overall group | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 44 | 190 | 234 | |

|

| ||||

| Age, years | 29 (18–45) | 39 (19–82) | 35 (18–82) | <0.001 |

|

| ||||

| Age distribution, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| ≥40 | 2 (4.5) | 90 (47.4) | 92 (39.3) | |

|

| ||||

| Gender, n (%) | 0.03 | |||

| Male | 14 (31.8) | 108 (56.8) | 122 (52.1) | |

|

| ||||

| Race, n (%) | 0.009 | |||

| Caucasian | 2 (4.6) | 35 (18.4) | 37 (15.8) | |

| Asian | 40 (90.8) | 129 (76.3) | 169 (72.2) | |

| Other | 2 (4.6) | 26 (13.7) | 28 (11.9) | |

|

| ||||

| BMI | 23±4.5 | 25.1±5.4 | 24.7±5.3 | 0.031 |

|

| ||||

| Family history of HCC, n (%) | 0.18 | |||

| Positive | 8 (18.2) | 22 (11.6) | 30 (12.8) | |

| Negative | 25 (56.8) | 135 (71.1) | 160 (68.4) | |

| Unknown | 11 (25) | 33 (17.4) | 44 (18.8) | |

|

| ||||

| Follow-up period, months | 29.1 (12–158.7) | 57.7 (12–163.8) | 51 (12–163.8) | <0.001 |

|

| ||||

| Laboratory values | ||||

| Platelet (k/mm3) | 235±51 | 224±60 | 226±58 | 0.30 |

| INR | 0.98±0.09 | 0.99±0.07 | 0.99±0.07 | 0.60 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 4.2±0.4 | 4.4±0.4 | 4.3±0.3 | 0.09 |

| AST (U/L) | 30±11 | 30±18 | 30±17 | 0.83 |

| ALT (U/L) | 37±17 | 39±22 | 39±21 | 0.50 |

| ALT distribution, n (%) | 0.48 | |||

| <ULN | 28 (63.6) | 119 (62.6) | 147 (62.8) | |

| 1–2X ULN | 16 (36.4) | 65 (34.2) | 81 (34.6) | |

| >2X ULN | 0 (0) | 6 (3.2) | 6 (2.6) | |

| HBV DNA, n (%) | <0.0001 | |||

| <2,000 IU/mL | 2 (4.5) | 101 (53.2) | 103 (44.1) | |

| 2,000–19,999 IU/mL | 2 (4.5) | 52 (27.9) | 54 (23.1) | |

| 20,000–199,000 IU/mL | 3 (6.8) | 26 (13.7) | 29 (12.4) | |

| ≥200,000 IU/mL | 37 (84.1) | 10 (5.3) | 47 (20.1) | |

|

| ||||

| Liver histology, n | 3 | 30 | 33 | |

| Ishak fibrosis score, n (%) | 0.074 | |||

| 0–1 | 2 (66.7) | 23 (76.6) | 25 (75.7) | |

| 2–3 | 1 (33.3) | 7 (23.4) | 8 (24.3) | |

| 4–6 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0(0) | |

|

| ||||

| REACH-B Score*, n | 9 | 115 | 124 | <0.001 |

| Mean±SD | 8.8±0.8 | 6.4±2.9 | 6.5±2.9 | |

Results are expressed as number (%), mean±SD, median (range),

REACH-B score is applied to patients who had ≥3 years of follow-up.

Phases of chronic HBV infection at baseline and transitions during follow-up HBeAg-positive patients

At presentation, median age of the 44 HBeAg-positive patients was 29 years and only 2 (4.5%) were above the age of 40, 24 (54.5%) were in the IT phase, 16 in the mildly active phase and 4 in the low replication phase (Figure 1A.

Figure 1.

Figure 1A. Phases of chronic HBV infection at presentation and transitions during follow-up in HBeAg-positive patients

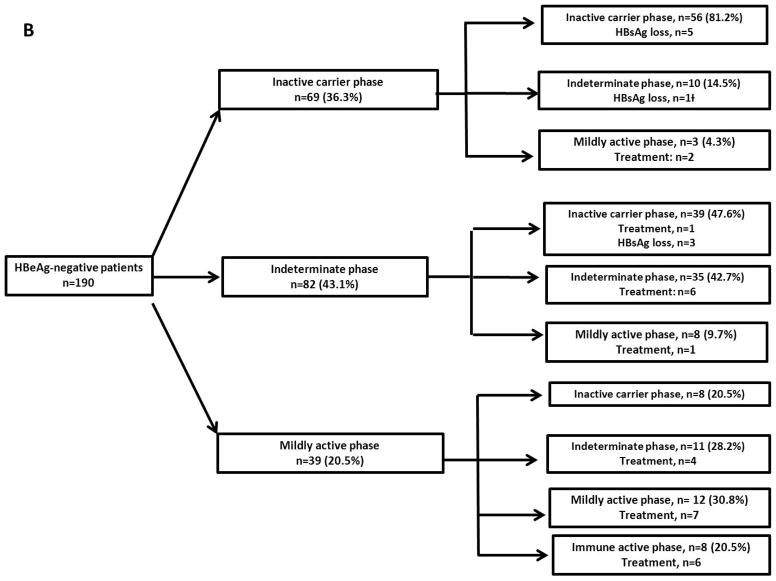

Figure 1B. Phases of chronic HBV infection at presentation and transitions during follow-up in HBeAg-negative patients

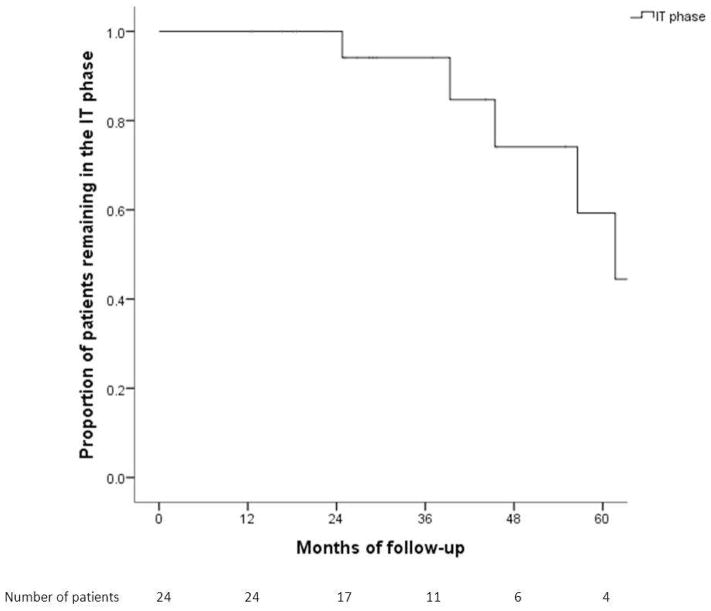

Of the 24 patients in the IT phase, 18 (66.7%) remained in the same phase. Cumulative probability of remaining in the IT phase at Year 1, 3 and 5 was 100%, 93% and 60%, respectively (Figure 2). Six patients transitioned to immune active phase after a median of 50.9 months, 1 patient underwent spontaneous HBeAg seroconversion, while the other 5 started antiviral treatment. Four of the 5 patients who initiated treatment were observed for >3 months while 1 was observed for 2 months before initiation of treatment. Patients who transitioned to the immune active phase were similar to those who remained in the IT phase except for longer follow-up duration (55.2 vs 27.6 months, p=0.015).

Figure 2.

Cumulative probability of remaining in the immune tolerance phase

Of the 16 patients in the mildly active phase, 10 transitioned to immune active phase after a median of 17.9 months, three remained in the mildly active phase and three reverted to IT phase. Among the 10 patients transitioned to immune active phase, 1 had spontaneous HBeAg loss, 8 started treatment within a month, and 1 declined treatment.

All four patients in the low replication phase remained in the same phase; of these, 2 underwent spontaneous HBeAg seroconversion.

Overall, 16 (36%) of the HBeAg-positive patients transitioned to a more active phase, and 13 of these16 patients started treatment.

HBeAg-negative patients

Among the 190 HBeAg-negative patients, 69 (36.3%) were in the IC phase, 82 (43.1%) in the indeterminate phase and 39 (20.5%) in the mildly active phase at presentation (Figure 1B).

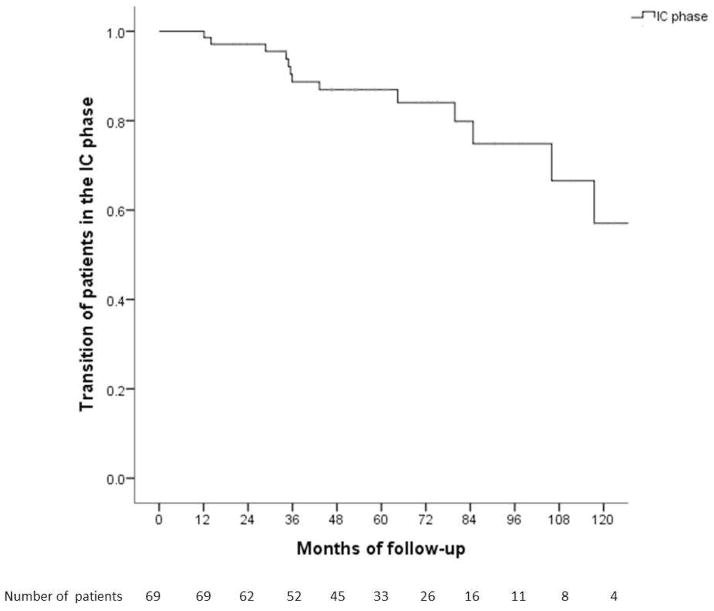

Of the 69 patients in the IC phase, 56 (81.2%) remained in the same phase while 10 transitioned to the indeterminate phase and three to the mildly active phase. Cumulative probability of remaining in the IC phase at Year 1, 3, 5, and 10 was 100%, 89%, 87%, and 57%, respectively (Figure 3A). Baseline characteristics of patients remained in the IC phase and those transitioned to a more active phase were similar.

Figure 3.

Figure 3A. Cumulative probability of remaining in the inactive carrier phase

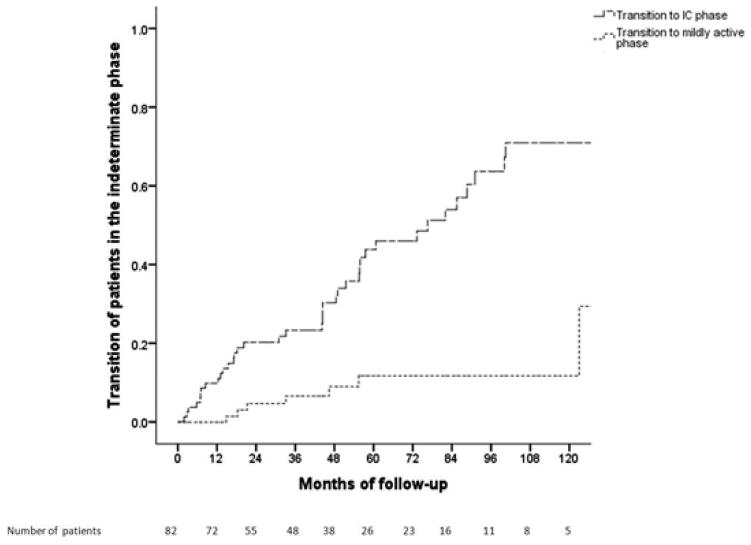

Figure 3B. Cumulative probability of transitions from the indeterminate phase

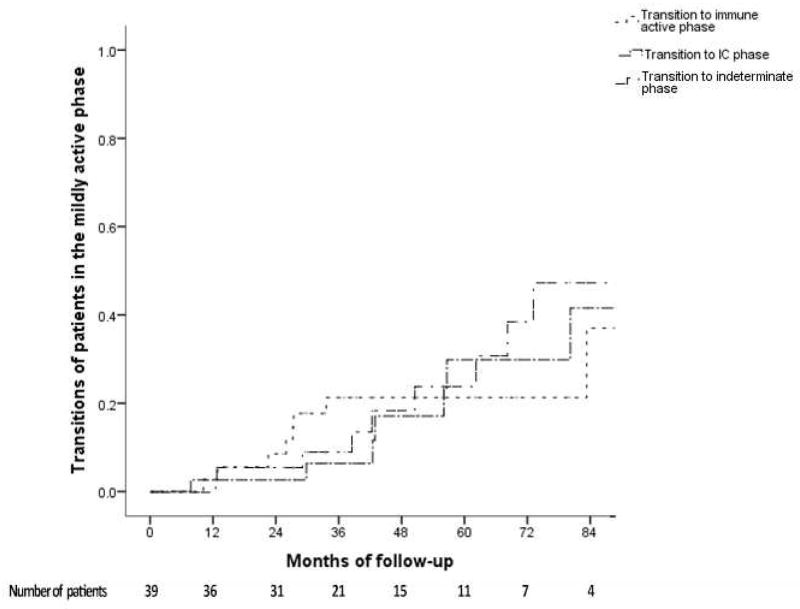

Figure 3C. Cumulative probability of transitions from the mildly active phase.

Of the 82 patients in the indeterminate phase, 50 (61%) patients had HBV DNA >2,000 IU/mL (median 10,750 IU/mL) and ALT <ULN, and 32 (39%) had HBV DNA <2,000 IU/mL and ALT >ULN (median 53 U/L) at presentation. Thirty-five (42.7%) patients remained in the same phase while 39 (47.6%) transitioned to the IC phase, 8 (9.7%) to mildly active phase, and none to immune active phase. Cumulative probability of transitioning from indeterminate phase to inactive carrier phase at Year 1, 3, 5 and 10 was 10%, 24%, 44% and 70% and from indeterminate phase to mildly active phase was 0%, 6%, 11% and 11%, respectively (Figure 3B). Patients who transitioned to mildly active phase had lower baseline platelet count than those who transitioned to IC phase or those who remained in the indeterminate phase (167±77 vs 240±69 vs 227±57 k/mm3, p=0.04).

In a subanalysis of 23 HBeAg-negative patients with undetectable HBV DNA at presentation, 14 were in the IC phase and 9 in the indeterminate phase. During follow-up, 19 remained or reverted to IC phase and 4 (17.4%) lost HBsAg.

Among the 39 patients in the mildly active phase, 19 (48.7%) had HBV DNA 2,000–20,000 IU/mL and 20 (51.3%) had HBV DNA ≥20,000 IU/mL and ALT 1–2X ULN. Of these 39 patients, 8 transitioned to immune active phase, 11 to indeterminate phase, and 8 reverted to IC phase. Cumulative probability of transitioning to the immune active phase at Year 1, 3, and 5 was 3%, 8% and 21%, respectively; while reversion to indeterminate phase was 0%, 9%, and 25% and reversion to IC phase was 3%, 6% and 28%, respectively (Figure 3C). The 8 patients who transitioned to IC phase had a longer follow-up duration than the other 31 patients in this group (91.6 vs 35.6 months, p=0.005).

Liver biopsy was performed in 41 (34%) of 121 patients in the indeterminate or mildly active phase and 5 (12%) had Ishak fibrosis score ≥3.

Outcomes

Spontaneous HBeAg seroconversion

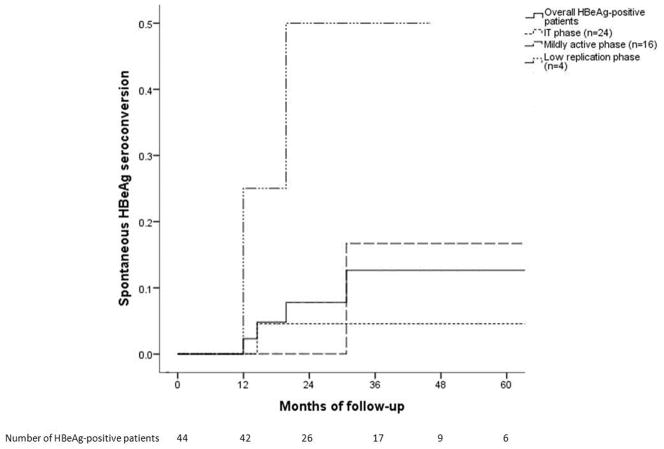

Spontaneous HBeAg seroconversion was observed in 4 (9.1%) HBeAg-positive patients (2 in the low replication phase, 2 transitioned from IT and mildly active phase to immune active phase) after a median of 17.1 months with a cumulative probability of 2%, 12% and 12% at Year 1, 3 and 5, respectively. Patients in the low replication phase and mildly active phase were more likely to undergo spontaneous HBeAg seroconversion than those in the IT phase (Figure 4A). Baseline characteristics of patients who underwent HBeAg seroconversion were similar to those who did not except for lower baseline HBV DNA levels (median 4.6 vs. 8.1 log10 IU/mL, p=0.04).

Figure 4.

Figure 4A. Cumulative probability of spontaneous HBeAg seroconversion

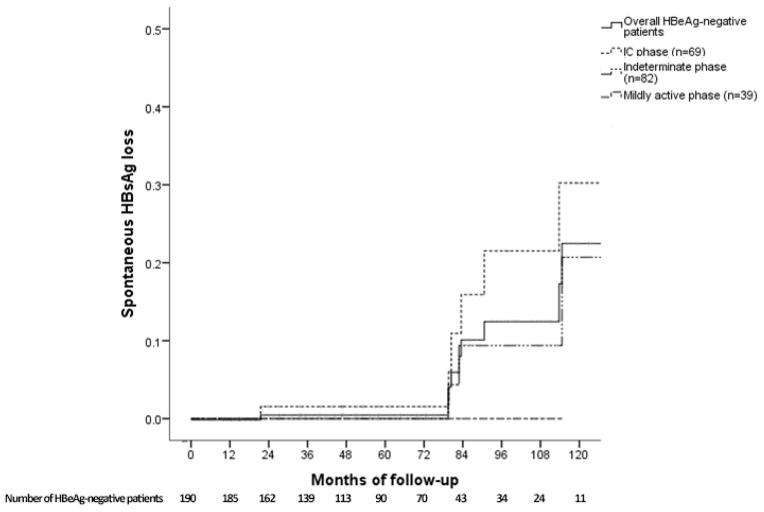

Figure 4B. Cumulative probability of spontaneous HBsAg loss

Spontaneous HBsAg loss

Spontaneous HBsAg loss was observed in 9 (4.7%) HBeAg-negative patients (5 remained in the IC phase, 3 transitioned from indeterminate to IC phase, 1 transitioned from IC to indeterminate phase) after a median of 82.8 months. Cumulative probability of HBsAg loss for HBeAg-negative patients at Year 1, 3, 5 and 10 was 0%, 1%, 1% and 21%, respectively (Figure 4B). Patients who underwent HBsAg loss were older (51.3±8.1 vs 39.6±11.8 years, p=0.04), more likely to have undetectable HBV DNA at presentation (17.4% vs 3%, p<0.001) and had a longer follow-up duration (median 90.6 vs 55.2 months, p=0.001) than those who did not undergo HBsAg loss. None of the HBeAg-positive patients lost HBsAg.

Initiation of antiviral treatment

Forty-five patients (19.2%), 16 HBeAg-positive and 29 HBeAg-negative, transitioned to a more active phase. Of these, 22 (49%) initiated antiviral treatment. Treatment was not initiated in the remaining 23 patients - 11 transitioned from IC phase to indeterminate (n=10) or mildly active phase (n=1), 7 transitioned from indeterminate to mildly active phase, 2 HBeAg-positive patients underwent spontaneous HBeAg seroconversion, and 3 patients who declined treatment despite transition to immune active phase.

Antiviral treatment was started in 44 patients (17 HBeAg-positive and 27 HBeAg-negative) after a median of 33 months. In addition to the 22 patients who transitioned to a more active phase, 22 were started on antiviral treatment - 3 required immunosuppressive therapy, 3 had high viremia during pregnancy, 5 had Ishak fibrosis score >2 at baseline or follow-up biopsy, 2 had low platelet count and age >40 years, and 9 had fluctuating HBV DNA and ALT levels.

Liver failure and HCC

None of the patients experienced severe hepatitis flare or liver failure. Among the 169 patients with ≥3 years of follow-up, REACH-B score was applicable in 124 patients (9 HBeAg-positive, 115 HBeAg-negative) whose ages fell between 30 and 65. Mean baseline REACH-B score was 8.8±0.8 in the HBeAg-positive patients and 6.4±2.9 in the HBeAg-negative patients. Predicted risk of HCC at Year 3 and Year 5 was 0.5% and 1.2% for HBeAg-positive patients, and 0.2% and 0.5% for HBeAg-negative patients. Two Asian HBeAg-negative patients developed HCC. A 25-year-old man in the indeterminate phase (HBV DNA: 14,000 IU/mL, ALT: 35 U/L) at presentation with no family history of HCC was diagnosed with HCC at Month 40. REACH-B score could not be applied because of his young age. The other patient was a 51-year-old man with mildly active hepatitis (HBV DNA: 1,000,000 IU/mL, ALT: 67 U/L) and family history of HCC. REACH-B score at presentation was 10 and predicted HCC risk at year 3 was 0.9%. This patient missed multiple follow-up visits until HCC diagnosis at Month 26.

Secondary analysis with lower ULN for ALT

In a secondary analysis with ULN for ALT of 30 for men and 19 for women, 211 (32 HBeAg-positive, 179 HBeAg-negative) patients would not meet treatment criteria at presentation. Of these, 42 (19.9%) transitioned to a more active phase and 34 (16.1%) initiated treatment during follow-up (Supplementary Figure 2). Twenty-three patients would be considered to have immune active disease; of these, 10 (43.5%) initiated treatment during follow-up. Of the two patients who developed HCC, the 25-year-old would be in the indeterminate phase and the 51-year-old in the immune active phase.

Discussion

In this single-center study of 234 CHB patients who did not meet treatment criteria at presentation, none of the patients developed liver failure and only two developed HCC after a median follow-up of 4.3 years (total: 1178 person-years). The favorable outcome is related to close monitoring and initiation of antiviral treatment when liver disease became more active. Indeed, during follow-up, 45 (19.2%) patients transitioned to a more active phase and 49% of these patients received antiviral treatment. Liberalizing treatment indications is unlikely to prevent the two HCC cases because of non-compliance with follow-up visits in one patient and the young age, borderline HBV DNA levels with normal ALT and lack of family history of HCC in the other patient.

Four HBeAg-positive patients were in the low replication phase; of these, two underwent spontaneous HBeAg seroconversion suggesting they may be at the tail end of immune clearance. Spontaneous HBeAg seroconversion occurred in two other patients after transitioning to immune active phase supporting previous observations that elevated ALT is predictive of HBeAg clearance.12, 13 None of the HBeAg-positive patients developed HCC after 147 person-years of follow-up indicating the importance of HBeAg positivity and high serum HBV DNA level as predictors of HCC must be interpreted in the context of patient age, ALT and other factors.6 In this study, only 2 (4.5%) HBeAg-positive patients were above the age of 40 at presentation compared to 67% of patients in the Risk Evaluation of Viral Load Elevation and Associated Liver disease/Cancer-HBV (REVEAL-HBV) study.6

Among the HBeAg-negative patients, 82 (43%) were in the indeterminate phase and 39 (21%) in the mildly active phase at presentation. These findings highlight the difficulties in categorizing patients into different phases of HBV infection. During a median follow-up of 57 months, only 7% of these patients transitioned to immune active phase suggesting that treatment may be deferred in most HBeAg-negative patients in the indeterminate or mildly active phase. Furthermore, 8 (20.5%) patients in the mildly active phase reverted to IC phase highlighting the dynamic nature of chronic HBV infection. Similar to other studies, the prognosis of the 69 patients in the IC phase was favorable, 81% remained in the IC phase, 6 (8.6%) underwent HBsAg loss, and none transitioned to immune active phase or developed HCC after 385 person-years of follow-up. One study of 146 inactive carriers prospectively followed for 8±6.3 years found that 88.4% of patients remained in the IC phase, 8.9% had HBsAg loss, only 1 (0.7%) patient had reactivation and 2 (1.4%) developed HCC.14 Some studies found abnormal liver histology or increased liver-related mortality among HBV carriers with normal ALT but many patients in these studies had normal ALT on 1 or 2 occasions only or HBV DNA higher than the usual cutoff for IC.7, 15

In this study, treatment was initiated in 19% of patients after a median follow-up of 33 months. Treatment was started in half of the patients because of transition to an active phase, while the other half received treatment based on histologic evidence of liver disease, fluctuating HBV DNA and ALT levels, patient age, suspected cirrhosis, or as prophylaxis for HBV reactivation in patients receiving immunosuppressive treatment or perinatal HBV transmission. The rates of transition to a more active phase and initiation of antiviral treatment during follow-up were similar in a secondary analysis with lower values as ULN for ALT. Another study of 245 Asian patients in the US, who did not meet treatment criteria at presentation found that almost 30% of the patients became treatment eligible based on US Panel Algorithm and AASLD guideline after a median follow-up of 26 months.16

The REACH-B score predicting HCC risk derived from the REVEAL-HBV study cohort and validated in an external cohort from three Asian liver centers could not be calculated in 27% of our patients because of their ages (<30 or >65).11 REACH-B score was not applicable to the 25-year-old Asian man who developed HCC. Even if we assume he was 30 years old at presentation, his REACH-B score would be 1 with predicted HCC risk of 0.1% at Year 10, but he developed HCC at Month 40. He underwent hepatic resection and histologic examination showed no cirrhosis. Expanding treatment criteria to this patient would translate to near universal treatment. While antiviral therapy has been shown to decrease the incidence of HCC in CHB patients, the risk of HCC is not eliminated and it is unclear if antiviral therapy would have prevented HCC in this patient. The second patient had a REACH-B score of 10 at presentation with projected HCC risk of 0.9%, 2% and 5.2% at Year 3, 5 and 10, respectively. Treatment was recommended but patient declined and missed multiple follow-up visits until HCC diagnosis. The REACH-B score had been validated in Asian patients; however, its accuracy in predicting HCC in patients of other races, infected with HBV genotypes other than B or C, or who acquired HBV infection in adult life is unclear. The utility of REACH-B score in determining which patient should undergo enhanced HCC surveillance or to receive antiviral treatment is also unknown.

One limitation of this study is the small number of patients in each phase of chronic HBV infection; thus, the precision in determining rates of transition from one phase to another is low. Another limitation is the generalizability of data from a tertiary liver center to the community. In addition, HBV genotypes and serial quantitative HBsAg levels were not available. However, strengths of this study include the fairly long duration of follow-up particularly in the HBeAg-negative patients and availability of serial HBV DNA levels based on sensitive PCR assays.

In conclusion, in this single-center study of CHB patients who did not meet treatment criteria at presentation, outcome was favorable when patients are closely monitored and antiviral treatment initiated when patients transitioned to a more active phase. Our data suggest that predicting which HBV patient will develop HCC is difficult and liberalizing treatment indications may not decrease HCC incidence. Our findings emphasize the importance of lifelong monitoring of patients with chronic HBV infection and the need for better prediction models for HCC.

Supplementary Material

Flowchart of the patients included

Secondary analysis with ULN for ALT of 19 U/L (female) and 30 U/L (male). *Other reasons for starting treatment were high viremia during pregnancy, Ishak fibrosis score >2 at baseline or follow-up biopsy, low platelet count and age >40 years, and fluctuating HBV DNA and ALT levels

Acknowledgments

Grant support: Suna Yapali received scholarship support from the Turkish Association for the Study of the Liver. The Tuktawa Foundation through the Alice Lohrman Andrews Professorship provided support for Suna Yapali, Nizar Talaat and Anna S. Lok. Anna S. Lok is partially supported by NIH grant U01 DK082863.

Abbreviations

- AASLD

American Association for the Study of Liver Disease

- ALT

Alanine aminotransferase

- anti-HBe

hepatitis B e antibody

- APASL

Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver

- CHB

Chronic hepatitis B

- EASL

European Association for the Study of the Liver

- HBV

Hepatitis B virus

- HBeAg

Hepatitis B e antigen

- HBsAg

Hepatitis B surface antigen

- HCC

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- IC

Inactive carrier

- IT

Immune tolerance

- LLD

lower limit of detection

- PCR

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

- REACH-B

Risk Estimation for Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Chronic Hepatitis B

- REVEAL-HBV

Risk Evaluation of Viral Load Elevation and Associated Liver disease/Cancer-HBV

- ULN

upper limit of normal

Footnotes

Author Contributions: S. Yapali and N. Talaat contributed to the study concept and design; acquisition of data; analysis and interpretation of data, literature review, and drafting of this manuscript; A. S. Lok contributed to the study concept and design, supervised the conduct of the study and analysis of the data, and edited this manuscript. Robert J. Fontana and Kelly Oberhelman contributed to interpretation of data and editing of this manuscript.

Disclosures: Suna Yapali, Nizar Talaat and Kelly Oberhelman have nothing to disclose. Anna S. Lok had received research grants from Bristol-Myers Squibb, AbbVie, Gilead Sciences, Idenix and Merck and had served on advisory board for Gilead Sciences, Merck and Janssen. Robert J. Fontana has received research support from Gilead, BMS, and Vertex.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Marcellin P, Gane E, Buti M, et al. Regression of cirrhosis during treatment with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for chronic hepatitis B: a 5-year open-label follow-up study. Lancet. 2013;381:468–75. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61425-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tenney DJ, Rose RE, Baldick CJ, et al. Long-term monitoring shows hepatitis B virus resistance to entecavir in nucleoside-naive patients is rare through 5 years of therapy. Hepatology. 2009;49:1503–14. doi: 10.1002/hep.22841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.EASL clinical practice guidelines: Management of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2012;57:167–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B: update 2009. Hepatology. 2009;50:661–2. doi: 10.1002/hep.23190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liaw YF, Kao JH, Piratvisuth T, et al. Asian-Pacific consensus statement on the management of chronic hepatitis B: a 2012 update (vol 6, pg 531, 2012) Hepatology International. 2012;6:809–10. doi: 10.1007/s12072-012-9365-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen CJ, Yang HI, Su J, et al. Risk of hepatocellular carcinoma across a biological gradient of serum hepatitis B virus DNA level. JAMA. 2006;295:65–73. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumar M, Sarin SK, Hissar S, et al. Virologic and histologic features of chronic hepatitis B virus-infected asymptomatic patients with persistently normal ALT. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1376–84. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.02.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tong MJ, Hsu L, Chang PW, et al. Evaluation of current treatment recommendations for chronic hepatitis B: a 2011 update. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26:829–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06623.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zoulim F, Mason WS. Reasons to consider earlier treatment of chronic HBV infections. Gut. 2012;61:333–6. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bruix J, Sherman M. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology. 2011;53:1020–2. doi: 10.1002/hep.24199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang HI, Yuen MF, Chan HL, et al. Risk estimation for hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B (REACH-B): development and validation of a predictive score. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:568–74. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70077-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liaw YF, Chu CM, Su IJ, et al. Clinical and histological events preceding hepatitis B e antigen seroconversion in chronic type B hepatitis. Gastroenterology. 1983;84:216–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lok AS, Lai CL, Wu PC, et al. Spontaneous hepatitis B e antigen to antibody seroconversion and reversion in Chinese patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Gastroenterology. 1987;92:1839–43. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(87)90613-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tong MJ, Trieu J. Hepatitis B inactive carriers: clinical course and outcomes. J Dig Dis. 2013;14:311–7. doi: 10.1111/1751-2980.12051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin CL, Liao LY, Liu CJ, et al. Hepatitis B viral factors in HBeAg-negative carriers with persistently normal serum alanine aminotransferase levels. Hepatology. 2007;45:1193–8. doi: 10.1002/hep.21585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nguyen NH, Nguyen V, Trinh HN, et al. Treatment eligibility of patients with chronic hepatitis B initially ineligible for therapy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:565–71. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Flowchart of the patients included

Secondary analysis with ULN for ALT of 19 U/L (female) and 30 U/L (male). *Other reasons for starting treatment were high viremia during pregnancy, Ishak fibrosis score >2 at baseline or follow-up biopsy, low platelet count and age >40 years, and fluctuating HBV DNA and ALT levels