Abstract

In previous studies that used compacted DNA nanoparticles (DNP) to transfect cells in the brain, we observed higher transgene expression in the denervated striatum when compared to transgene expression in the intact striatum. We also observed that long term transgene expression occurred in astrocytes as well as neurons. Based on these findings, we hypothesized that the higher transgene expression observed in the denervated striatum may be a function of increased gliosis. Several aging studies have also reported an increase of gliosis as a function of normal aging. In this study we used DNPs that encoded for human glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (hGDNF) and either a non-specific human polyubiquitin C (UbC) or an astrocyte-specific human glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) promoter. The DNPs were injected intracerebrally into the denervated or intact striatum of young, middle-aged or aged rats, and GDNF transgene expression was subsequently quantified in brain tissue samples. The results of our studies confirmed our earlier finding that transgene expression was higher in the denervated striatum when compared to intact striatum for DNPs incorporating either promoter. In addition, we observed significantly higher transgene expression in the denervated striatum of old rats when compared to young rats following injections of both types of DNPs. Stereological analysis of GFAP+ cells in the striatum confirmed an increase of GFAP+ cells in the denervated striatum when compared to the intact striatum and also an age-related increase; importantly, increases in GFAP+ cells closely matched the increases in GDNF transgene levels. Thus neurodegeneration and aging may lay a foundation that is actually beneficial for this particular type of gene therapy while other gene therapy techniques that target neurons are actually targeting cells that are decreasing as the disease progresses.

Keywords: aging, Parkinson’s disease, gene therapy, astrocytes, glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP)

In our previous studies using DNA nanoparticles (DNP) to deliver reporter genes to the brain, we observed long-term transgene expression occurred in both neurons and astrocytes (Yurek et al., 2009b). In a subsequent study we also observed that transgene expression in brain tissue was significantly greater when DNPs were injected into the denervated striatum than when these same DNPs were injected into the intact striatum (Fletcher et al., 2011). While it was initially unclear to us why this difference in transgene expression existed between the denervated and intact striatum, we hypothesized that this difference may be due to changes in the target cells following a neurodegenerative lesion. Astrocytes have been shown to respond profoundly to neuronal injury and undergo a series of metabolic and morphological changes that is known as astrogliosis; this condition has been observed in a variety of other pathologic brain conditions including cerebral ischemia, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, Huntington’s disease, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Schipper, 1996). Indeed, several studies have shown that degeneration of the nigrostriatal pathway can lead to profound increases in glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) expression in the striatum and ventral midbrain. For instance, Strömberg et al. was first to demonstrate a significant up-regulation of astrocytes in the striatum and substantia nigra following lesions of the nigrostriatal pathway using 6-OHDA or MPTP in rats or mice, respectively, that persisted for at least 1 month post-lesion (Stromberg et al., 1986). Subsequently, Sheng et al. reported that 6-OHDA lesions produced a persistent up-regulation of GFAP+ cells in the lesioned striatum that was significantly higher than in the control striatum at 28 days post-lesion (Sheng et al., 1993), while Dervan et al. reported a significant increase in the number of astrocytes in the striatum of mice 6–8 weeks following MPTP administration (Dervan et al., 2004). Similarly Rodrigues et al. reported an up-regulation of GFAP detected by immunohistochemistry in the ventral midbrain of 6-OHDA-treated rats at a 22 day post-lesion time point (Rodrigues et al., 2004). Clearly these results provide intriguing evidence that one cell-type targeted by DNPs, astrocytes, increase significantly as a result of nigrostriatal pathway degeneration, and it may be the case that the observed increase in GDNF levels in the lesioned striatum treated with DNPs is related to this increase in GFAP activity.

There are several reasons why we believe the variable of age is another important factor to consider in gene transfer studies, especially if those vectors target astrocytes. First, any translational study for the therapeutic treatment of Parkinson’s disease (PD) must address the issue of age because the incidence of the disease is greatest in the aged population. Second, there are numerous reports that the number of astrocytes actually increase with age in addition to pathological states. In normal aged brain it has been estimated that the number of astrocytes can double-to-quadruple over the lifespan of rodents (O’Callaghan and Miller, 1991), and GFAP expression increases in the hippocampus and striatum during mid-life (Yoshida et al., 1996, Morgan et al., 1997). In a rat model of PD, Gordon et al. demonstrated that there is an exaggerated astrocyte reactivity in striatum of aged animals treated with 6-OHDA when compared to younger lesioned animals (Gordon et al., 1997). Thus neurodegeneration and aging may lay a foundation that is actually beneficial for this particular type of gene therapy while other gene therapy techniques that target neurons are actually targeting cells that are decreasing as the disease progresses. From this standpoint, viral and DNP gene therapies may actually complement one another in that they can approach the same disease state by transfecting different cell types.

In this study we examined the effects of neurodegeneration and aging on transgene expression in brain cells following intracerebral injections of DNPs encoding for the neurotrophic factor human GDNF under transcriptional control of either the non-specific human polyubiquitin C (UbC) promoter or an astrocyte-specific human glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) promoter. We also assessed changes in glial activity in aging animals undergoing neurodegeneration of the nigrostriatal pathway because these cells are targets for the genetic payloads contained in the DNPs.

2. Experimental Procedures

2.1 Plasmid Construction

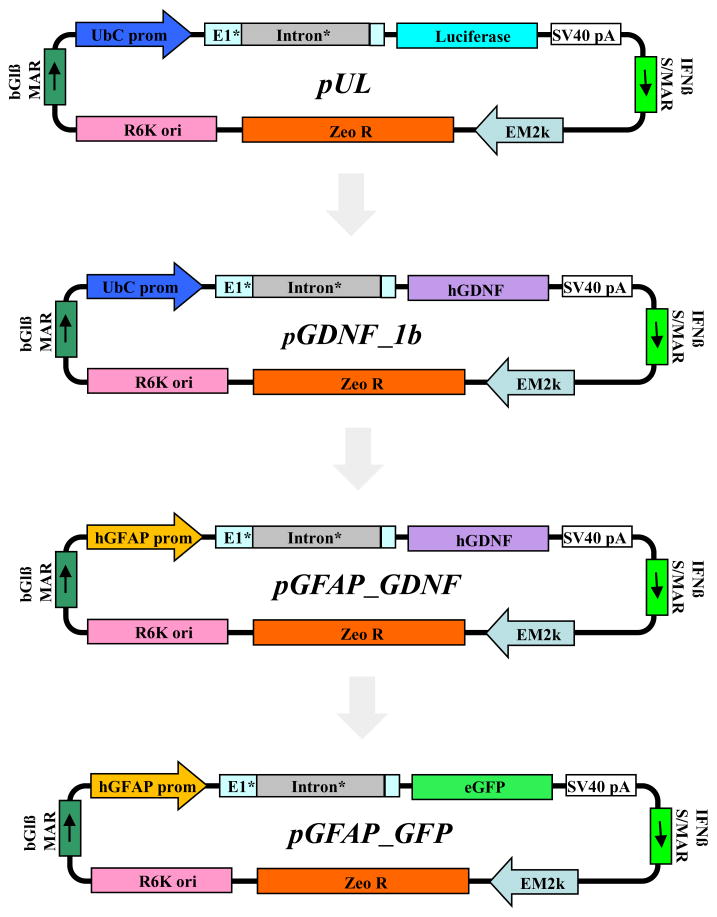

DNA vectors were constructed using standard molecular biology techniques, followed by restriction analysis and sequencing of subcloned regions (Sambrook et al., 1989). Detailed methodology for the pUL and pGDNF_1b plasmid construction is reported in previous publications (Fletcher et al., 2011, Padegimas et al., 2012). The transgene expression in pUL and pGDNF_1b plasmids are driven by the human polyubiquitin C (UbC) promoter. The pUL plasmid contains firefly luciferase encoding sequence (UbC-Luc expression cassette) and the pGDNF_1b plasmid contains hGDNF_1b gene variant (UbC-GDNF expression cassette); this plasmid encodes for the full-length transcript of GDNF (see Fletcher et al., 2011). Another two plasmid derivatives, pGFAP_GDNF and pGFAP_GFP are driven by the human GFAP promoter. A 1676 bp DNA fragment containing the hGFAP promoter was amplified from the InvivoGen (San Diego, CA, USA) pDRIVE-hGFAP plasmid and subloned into corresponding vectors designed for hGDNF_1b, Luc, or GFP expression. The pGFAP_GDNF plasmid contains the hGDNF_1b gene variant (GFAP-GDNF expression cassette) and pGFAP_GFP encodes enhanced green fluorescent protein (GFAP-eGFP expression cassette). Figure 1 shows the pUL plasmid map from which the plasmids encoding for hGDNF or enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) were derived.

Figure 1.

Plasmid maps for pUL, pGDNF_1b, pGFAP_GDNF and pGFAP_GFP. pGFAP_GDNF and pGFAP_GFP plasmids were derived from the pGDNF_1b plasmid (Fletcher et al., 2011). The pGFAP_GDNF plasmid is identical to pGDNF_1b with the exception that the UbC promoter was substituted with an hGFAP promoter.

2.2 Preparation of Condensing Peptide

L-Cysteinyl-poly-L-lysine 30-mers (American Peptide Company, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) were conjugated with 10-kDa polyethylene glycol (PEG) (Dow Pharma, Cambridge, England) as described in (Liu et al., 2003) except that trifluoroacetate counterion was replaced with acetate by size-exclusion chromatography on Sephadex G-25 before lyophilization of the PEGylated peptide.

2.3 Formulation of DNA Nanoparticles

Compacted DNA was manufactured by adding 20.0 mL of DNA solution (0.1 mg/mL in water) to 2.0 mL of PEGylated condensing peptide (3.2 mg/mL in water) at a rate of 4.0 mL/min by a syringe pump and through sterile tubing ended with a blunt cannula. During this addition, the tube with peptide was vortexed at a controlled rate so that the two materials mixed instantaneously. Peptide and DNA were formulated at a final amine-to-phosphate ratio of 2:1. The DNP was then filtered through a vacuum-driven sterile filter with 0.2-μm polyethersulfone membrane. The filtered DNP was then processed with tangential flow filtration to remove excess peptide and exchange solvent for saline, and then was concentrated 20–30 fold using VIVASPIN centrifugal concentrators (MWCO 100k) as described in a previous publication (Konstan et al., 2004). The final concentrations for compacted DNA were 4.3 μg/μl for pGDNF_1b, 4.4 μg/μl for pGFAP_GDNF, 4.4 μg/μl for pGFAP_GFP and 3.9 μg/μl for pUL. Uncompacted, naked pGFAP_GFP plasmid had a DNA concentration of 4.1 μg/μl. Obtained DNPs were named corresponding to the encoded expression cassette – compacted pGDNF_1b was named UbC-GDNF DNPs, compacted pGFAP_GDNF was named GFAP-GDNF DNPs, compacted pGFAP_GFP was named GFAP-eGFP and compacted pUL was named UbC-Luc DNPs. After formulation, the DNPs underwent several quality control tests, including sedimentation, turbidity, gel electrophoresis, and transmission electron microscopy, as described (Liu et al., 2003, Ziady et al., 2003a). Also, endotoxin levels were checked using an ENDOSAFE® PTS (Portable Test System) manufactured by Charles River Laboratories (Boston, MA, USA).

2.4 Primary Astrocyte Cultures

Fresh cortical tissue from E18 Sprague-Dawley rats was used to initiate the primary astrocyte cultures (BrainBits; Springfield, IL, USA). Papain was used to dissociate tissue and was diluted to a protein concentration of 2.0 mg/ml in Hibernate E-Ca (BrainBits; Springfield, IL, USA). Dissociation media was aspirated off and Hibernate EB (HEB; BrainBits, Springfield, IL, USA) was added to the tissue. A sterile silanized Pasteur pipette was used to disperse the cells and then cells were pelleted in a centrifuge at 200 x g for 1 min. Supernatant was discarded and the cell pellet was re-suspended in NbASTRO media (BrainBits; Springfield, IL, USA). Cells were plated on poly-D-lysine coated plates at a density of 7,500 cells/cm2 and incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2, 9% O2 and 95% humidity. Live cells treated with the pGFAP_GFP plasmid were observed using an inverted fluorescent microscope (Nikon TE2000); fluorescing cells were observed using a FITC filter and photographed using a CoolSnap ES camera (Photometrics; Tucson, AZ, USA) attached to the microscope. These cells were then subsequently fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and immunohistochemically stained for the neuronal marker, NeuN, using a monoclonal mouse anti-NeuN antibody (1:1,000; Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA).

2.5 Transfection of Cultures

Astrocyte cultures were transfected when they were approximately 80% confluent. At the time of transfection, cells were treated with 2.5 μg of pGFAP_GFP plasmid DNA or pGFAP_GDNF plasmid DNA in the presence of Lipofectamine™. After 4 hours of incubation in the transfection medium at 37°C, medium was removed and replaced with NbASTRO (astrocyte cultures). Cultures were terminated three days later and cells processed for either microscopic, immunohistochemical or protein analysis. Cells treated with the pGFAP_GDNF plasmid were analyzed for GDNF protein content as follows. Culture media were removed and stored at −80°C for subsequent analysis of secreted GDNF protein using ELISA. 200 μl of 1X cell culture lysis reagent (Promega; Madison, WI, USA) was then added to each well. Plates were placed on shaker in cold room for 30 minutes and samples were scrapped and then transferred to microcentrifuge vials. Samples were centrifuged at 10,000 X g for 10 minutes at 4°C. Supernatants were stored at −80°C for subsequent analysis of intracellular GDNF protein.

2.6 Animals

Male Sprague-Dawley rats were obtained from Harlan Farms (Indianapolis, IN, USA) at ages 3, 13 or 20 months; analysis on brain tissue was performed approximately two months later, so the actual ages of the animals at the time of analysis were approximately 5, 15 or 22 months old. All rat procedures were conducted in strict compliance with approved institutional protocols, and in accordance with the provisions for animal care and use described in the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” (NIH publication No. 86-23, NIH, 1985).

2.7 6-hydroxydopamine Lesion

All rats in Studies 2, 3 and 4 were given unilateral 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA) lesions of the left nigrostriatal pathway; 6-OHDA (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was dissolved in 0.9% saline (containing 0.2% ascorbic acid) at a concentration of 3.0 μg/μl and stereotactically injected into the nigrostriatal pathway of isoflurane-anesthetized rats at a rate of 1.0 μl/min for 2 min. Each rat received two injections of 6-OHDA: one injection in the medial forebrain bundle (AP −4.4, ML 1.6, DV −7.7) area and the other in the rostral pars compacta of the substantia nigra (AP −5.3, ML 2.0, DV −6.8); all coordinates reported in this study represent millimeter adjustments from bregma (AP, ML) and below the dural surface (DV) with the top of the skull in a flat position. This technique routinely produces complete lesions of dopamine neurons in the A9 and A10 midbrain regions, and near complete denervation of dopaminergic fibers innervating the ipsilateral striatum (Thomas et al., 1994).

2.8 Stereotactic Microinjection of DNPs into Brain

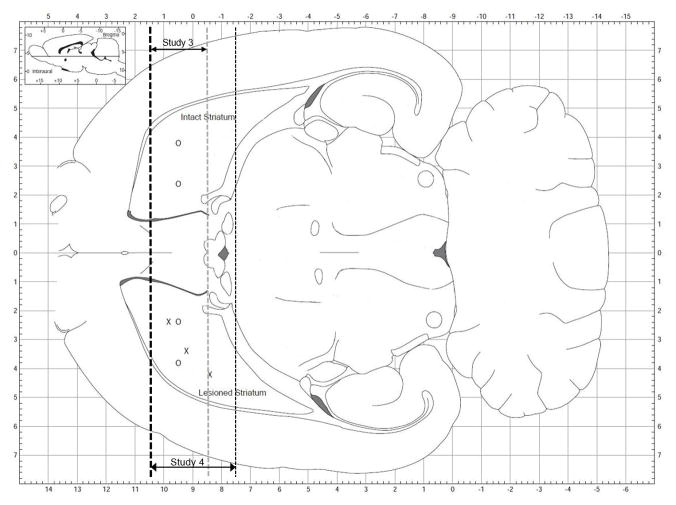

Four weeks after rats received 6-OHDA lesions, DNA nanoparticles in sterile saline were loaded into a sterile 30 gauge Hamilton syringe needle. Rats were anesthetized with isoflurane, placed in a stereotactic apparatus and then maintained under isoflurane (2% gas/air mixture, flow rate 1.0 L/min) for the duration of the surgical procedure. Injections of DNPs were made stereotactically into the brain of anesthetized rats using a 10 μL Hamilton syringe attached to a Quintessential Stereotaxic Injector (Stoelting; Wood Dale, IL, USA) and delivered at a rate of 0.5 μL/min for 4 minutes per site. For each needle track the injector was lowered to the deepest DV coordinate (DV1), a 2.0 μL deposit of DNPs was made at this site and the injector needle was retracted to the second site (DV2) and a second 2.0 μL deposit was made at this site. Figure 2 shows the injection sites for each of the studies. For studies 2 and 3, 4 needle tracks per animal were used at the following coordinates: Track 1 AP +0.5, ML +2.4, DV1 −6.0, DV2 −4.0; Track 2 AP +0.5, ML +3.8, DV1 −6.0, DV2 −4.0; Track 3 AP +0.5, ML −2.4, DV1 −6.0, DV2 −4.0; Track 4 AP +0.5, ML −3.8, DV1 −6.0, DV2 −4.0. For Study 4, 3 needle tracks per animal were used at the following coordinates: Track 1 AP +0.8, ML +2.4, DV1 −6.0, DV2 −4.0; Track 2 AP +0.2, ML +3.4, DV1 −6.3, DV2 −3.8; Track 3 AP −0.6, ML +4.2, DV1 −6.1, DV2 −3.9. All stereotaxic adjustments were made with the skull in the flat position: AP and ML adjustments were made from the intersection of the sagittal and coronal sutures (bregma), and DV adjustments were made from the top of the skull; all stereotactic coordinates used in these studies were determined using a stereotaxic atlas (Paxinos and Watson, 2007).

Figure 2.

Diagram of a horizontal section of rat brain showing the needle track locations for the DNP injections. For Studies 2 (GFAP-GFP) and 3 (GFAP-GDNF, UbC-GDNF or UbC-Luc), DNPs were injected bilaterally into the striatum of animals with unilateral 6-OHDA lesions; needle tracks are designated by “O”. For Study 4, DNPs were injected into only the lesioned striatum and needle tracks are designated by “X”. For both studies, 2 deposits of DNPs (2.0 μl/deposit) were made per needle track. Dotted lines indicate the site of coronal cuts for tissue dissections. Thick dotted line was the common anterior cut for both Studies 3 and 4 while the thin gray dotted line indicates posterior cut for Study 3 and the thin black dotted line indicates posterior cut for Study 4; double-headed arrows indicates the thickness of tissue sections for each study. For both studies, striatal tissue was dissected one week following the injections of DNPs.

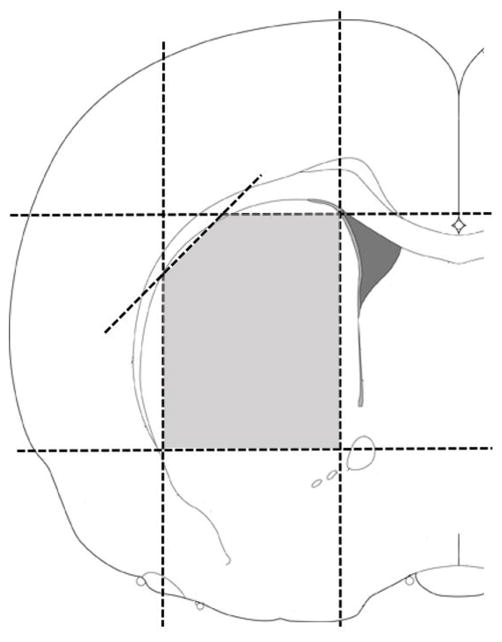

2.9 Tissue Dissection for ELISA Assays

For striatal dissections, brains were removed from euthanized animals and then placed upside down (ventral surface facing upwards) into a stainless steel brain matrix (RMB-4000C; ASI Instruments, Warren, MI, USA). For the following descriptions, the approximate stereotaxic coordinates are listed in parentheses. For Study 3, the initial coronal cut was targeted at a level just caudal to the optic chiasm (~AP −0.5) and a second cut was made 2.0 mm anterior to the initial cut; this produced a 2.0 mm thick coronal slab containing the DNP injection sites (see Figure 2). For Study 4, the initial coronal cut was targeted 1.0 mm caudal to the optic chiasm (~AP −1.5) and a second cut was made 3.0 mm anterior to the initial cut; this produced a 3.0 mm thick coronal slab containing the DNP injection sites (see Figure 2). The coronal slab formed by these two cuts was removed from the brain matrix and then divided into two pieces along the midline in order to separate the hemispheres. Both the left and right striatum were dissected from the two pieces as shown in Figure 3. A rectangular piece of tissue was dissected by making the following cuts: 1) a cut parallel to the midline was made just lateral to the lateral ventricle, 2) a cut parallel to the midline was made just medial to the lateral aspect of striatum at the striatum/corpus callosum border, 3) a cut perpendicular to the midline was made just ventral to the dorsal aspect of the striatum at the striatum/corpus callosum border, and 4) a cut perpendicular to the midline was made just dorsal to the anterior commissure. Dissected tissues were weighed, immediately frozen on dry ice and stored at −80°C until analyzed for protein content.

Figure 3.

Diagram showing the striatal tissue dissection in a coronal plane. The dotted lines indicate where tissue cuts were made in the coronal tissue slab. The shaded (light gray) region represents the tissue piece that was saved for subsequent protein analysis. While this diagram only shows one side of the brain, a similar dissection was made in the opposite hemisphere.

2.10 Quantification of GDNF by Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

Protein levels of GDNF were measured in culture media, culture cell lysates or tissue samples using ELISA. Each tissue sample was diluted to a protein concentration of 25 mg/ml in homogenization buffer [400 mM NaCl, 0.1% Triton-X, 2.0 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM benzethonium chloride, 2.0 mM benzamidine, 0.1 mM PMSF, Aprotinin (9.7 TIU/ml), 0.5% BSA, 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH=7.4] and homogenized using a Sonic Dismembrator (Fisher Scientific; Pittsburgh, PA, USA). The homogenates, lysates or cell culture media were centrifuged for 10 minutes at 10,000 x g at 4°C and then the supernatant was collected and stored at −80°C. Samples were then assayed for GDNF content using a human GDNF DuoSet ELISA kit (R&D Systems; Minneapolis, MN, USA).

2.11 HPLC Methods for Dopamine Content

Striatal tissue levels of dopamine (DA) and metabolites were measured using HPLC with electrochemical detection. An aliquot of sample in ELISA homogenization buffer was centrifuged at 12,000 x g for 5 minutes, and then the supernatant transferred to 0.22 μm pore size Ultrafree-MC centrifugal filters (Millipore; Bedford, MA, USA) and spun at 12,000 x g for one minute. The filtrate was diluted with mobile phase and 40 μl was injected onto the HPLC column for separation and analysis as previously described (Cass et al., 2003). Results were expressed as ng/g wet weight of tissue and as a percent depletion in DA on the lesioned side relative to the contralateral side.

2.12 Immunohistochemistry

At 5 weeks after the lesion the animals were anaesthetized with Fatal Plus™ (Vortech Pharmaceuticals; Dearborn, MI, USA) and transcardially perfused with 50 ml of 0.9% saline at 4°C followed by 200 ml of cold (4°C) 4% paraformaldehyde dissolved in 0.1M phosphate buffer. Brains were removed and post-fixed for 3 hours in the same fixative at 4°C and then transferred to a 30% sucrose solution for a minimum of 24 hours prior to sectioning. Brains were frozen in powdered dry ice and then maintained in a frozen state on a Physitemp freezing stage (BFS- 30MP; Physitemp, Clifton, NJ, USA). Each brain was serially sectioned into 50 μm thick sections in the coronal plane using a sliding microtome (Leica SM 2000R). Free-floating sections were rinsed 3 times in 0.1M PBS and pre-incubated in room temperature for 1 hour in 0.1M PBS containing 0.3% Triton X-100 and 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA). The sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with the following primary antibodies: polyclonal rabbit GFAP (1:10,000; Dako, Carpinteria, CA, USA) or monoclonal mouse GFAP (1:200; Abcam,) for detection of astrocytes, polyclonal goat Iba1 (1:500; Novus Biologics, Littleton, CO, USA) for detection of microglia, monoclonal mouse O1 (1:100; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) for detection of oligodendrocytes, monoclonal mouse NeuN (1:1,000; Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA) or monoclonal mouse TuJ1 (1:1,000; Covance, Dedham, MA, USA) for detection of neurons, DAPI (2.0 μg/ml; Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA) nuclear stain, and polyclonal rabbit GFP (1:500; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) or monoclonal mouse GFP (1:1,000; Abcam). For double-label studies, tissue sections were incubated simultaneously with two primary antibodies that targeted different antigens and that were raised in different species. Following the overnight incubation with primary antibodies, the tissue sections were then rinsed several time in 0.1M PBS. Secondary antibodies, donkey anti-rabbit conjugated with FITC (1:200; Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA) or Alexa Fluor 594 donkey anti-mouse (1:200; Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA) were diluted in 0.1M PBS + 0.3% Triton X-100 + 1% NDS and tissue sections were incubated in the secondary antibody solution for 1 hour. For stereological analysis of astrocytes, tissue sections were incubated overnight and at 4°C with only one primary antibody, polyclonal rabbit GFAP (1:10,000; Dako, Carpinteria, CA, USA). The sections were then incubated in an affinity-purified biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (1:800; Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA) and then incubated in an avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA). Staining was completed by placing sections in a 0.003% H2O2 solution containing diaminobenzidine chromagen to visualize the reaction. Sections were then counterstained with cresyl violet. To control for nonspecific staining, some brain sections were immunostained without the addition of primary antibody. Sections were mounted on Fisherbrand Superfrost/Plus microscope slides, dried for 3 hours and counterstained with cresyl violet. The sections were dehydrated for 50 minutes followed by three changes in xylene for 30 minutes and then coverslipped with Optic Mount 1 (Mercedes Medical, Sarasota, FL, USA).

2.13 Stereological Analysis

The unbiased stereological estimation of the total number of GFAP+ cells at 12 rostro-caudal levels in the striatum (starting at AP +1.6 through AP −0.6 according to the atlas of Paxinos and Watson) was assessed using the optical fractionator technique (Long et al., 1998) assisted by the computer based system Stereologer™ (Stereology Resource Center, St. Petersburg, Florida, USA). A single experimenter (U.H.) collected all stereological data for this study without the knowledge of the lesion or intact side of the brain or the age of each rat. Briefly, the equipment consisted of a color video camera connected to a microscope (Nikon 90i) with an X-Y-Z motorized stage. Microscope slides containing immunohistochemically stained brain sections were placed on the motorized stage and the digital output of the camera was processed by a high-resolution video card and displayed on the monitor of a computer. The Stereologer™ software controlled the operation of the system. Counts were performed using a 100X oil immersion objective (Nikon Plan Apo VC 100X 1.45 Oil). The densities of astrocytes (cells per mm3) in each striatal compartment were calculated as the number of cells counted divided by the total volume sampled of each reference space. The volume of sampled reference space was the product of the number of disectors multiplied by the volume of one disector.

2.14 Statistical Analyses

The α level of significance was set at p < 0.05. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for statistical analyses; choice of test was dependent on the experimental design. For ANOVA, we used Tukey’s test for post-hoc multiple comparisons when results of ANOVA warranted. Descriptive statistics: means are reported with their corresponding standard error of the mean (s.e.m.).

3. Results

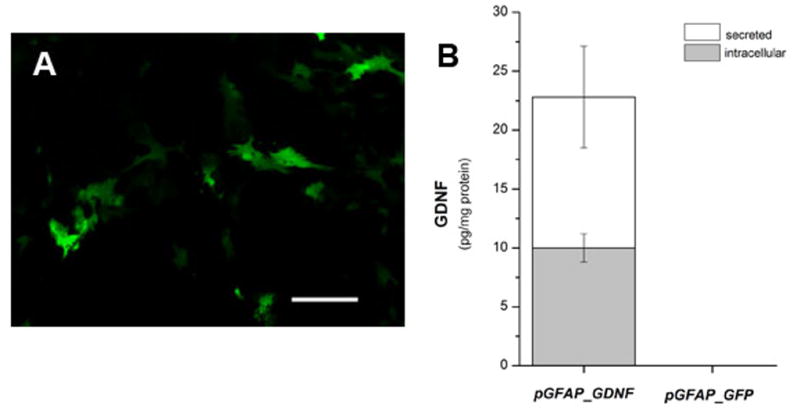

3.1 Study 1 - Transfection of astrocyte cultures with pGFAP_GFP or pGFAP_GDNF plasmids

Because we designed a plasmid with a GFAP promoter as a means to target transgene expression specifically in astrocytes, our initial study was designed to observe transgene expression of this plasmid in transfected cultures of primary astrocytes. Figure 4A shows an example of primary astrocytes that were successfully transfected with the naked pGFAP_GFP plasmid DNA and Lipofectamine complexes. We estimated approximately 54% of the cells transfected with pGFAP_GFP were eGFP+ three days post-transfection. These cultures were approximately 95% astrocytes and subsequent immunohistochemical analysis did not reveal any eGFP+ cells co-localized to NeuN+ cells (data not shown). We observed both secreted and intracellular levels of GDNF protein in cultures transfected with pGFAP_GDNF while cultures transfected with the pGFAP_GFP plasmid did not express detectable levels of GDNF protein (Figure 4B). The results of this study indicate that astrocytes can be specifically transfected by the pGFAP_GDNF plasmid and produce GDNF protein.

Figure 4.

Primary astrocyte cultures transfected with pGFAP_GFP or pGFAP_GDNF. Photomicrographs of live GFP+ cells in (A) primary astrocyte cultures; photo was taken 3 days after transfection with pGFAP_GFP plasmid DNA and Lipofectamine complexes. Cultures were transfected when cortical astrocytes were approximately 80% confluent. (B) GDNF protein measured in astrocyte cultures transfected with plasmids containing the GFAP-GDNF expression cassette (pGFAP_GDNF) or the negative control GFAP-eGFP expression cassette (pGFAP_GFP). GDNF protein measurements were made 3 days post-transfection. Scale bar = 50 μm.

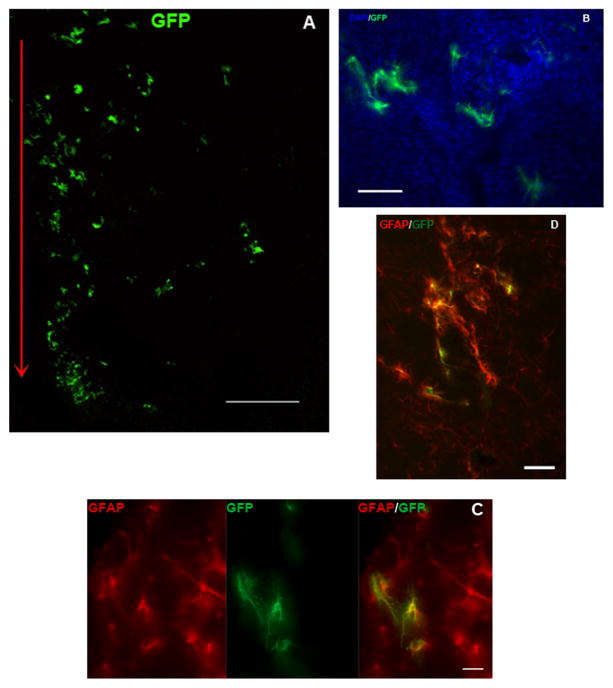

3.2 Study 2 - In vivo transfection of striatal cells with pGFAP-GFP DNPs: immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical analysis of brain sections taken from animals receiving intracerebral injection of GFAP-GFP DNPs into the striatum revealed GFP+ cells along the entire length of the injector tract and extending > 1.0 mm lateral to the tract (Figure 5A); few scattered GFP+ cells could be observed in the striatal parenchyma > 3.0 mm from the injector tract and also sporadically within the corpus callosum. Morphology of GFP+ cells indicate they are astrocytes (Figure 5B) and double-label immunohistochemical analysis confirmed that GFP+ cells co-localized to GFAP+ cells (Figure 5C and 5D). GFP+ cells did not co-localize to NeuN+ or TuJ1+ cells, nor did they co-localize to cells that were Iba1+ or O1+, indicating that these cells were not neurons, microglia or oligodendrocytes, respectively (not shown). Approximately 40% of the GFAP+ cells are also GFP+ within 1 mm of the injector tract.

Figure 5.

Immunohistochemical analysis of brain sections showing striatal cells transfected with GFAP-GFP (4.3 μg/μl) DNPs. (A) Low power photomicrograph showing distribution of GFP+ cells lateral to the injection site. Red arrow designates the injector tract. Scale bar = 1,000 μm. (B) 20X photomicrograph showing striatal cells labeled for DAPI (blue) and GFP (green). Scale bar = 100 μm. (C) High power photomicrographs showing striatal cells labeled for GFAP (left panel) or GFP (middle panel) and then digitally merged (right panel) showing co-labeled cells, which appear yellow. Scale bar = 25 μm. (D) Digitally merged image of photomicrographs showing GFAP (red) and GFP (green) labeled cells at a lower magnification; co-labeled cells appear yellow. Scale bar = 100 μm.

3.3 Study 3 - Transgene expression of GDNF in lesioned vs. intact striatum of young rats using compacted plasmids incorporating a GFAP or UbC promoter

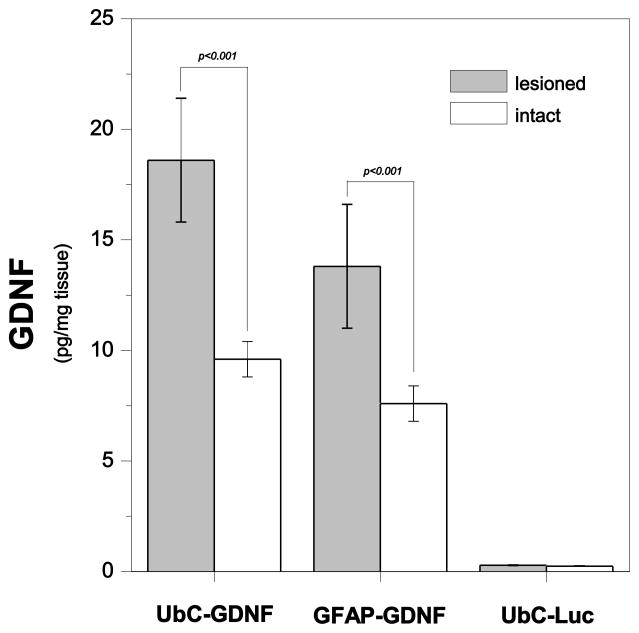

Having established that the pGFAP_GDNF plasmid containing the GFAP-GDNF expression cassette successfully transfected astrocyte cultures and GFAP-GFP DNPs successfully transfected astrocytic cells in vivo, we proceeded to the next phase of this study in which we compacted this plasmid into DNPs and then compared the in vivo efficacy of these DNPs to our previously tested UbC-GDNF DNP (compacted pGDNF_1b), which contains the UbC promoter (Fletcher et al., 2011). Four weeks after a unilateral 6-OHDA lesion, DNPs including a negative control UbC-Luc DNP (compacted pUL), were injected into the intact and denervated striatum of young rats, as shown in Figure 2. One week later striatal tissue was dissected and GDNF protein content was measured. Figure 6 is a plot of GDNF values as a function of Vector (UbC-GDNF, GFAP-GDNF or UbC-Luc) and Side (lesioned and intact). The main effects of Vector [F (2, 26) = 19.67, p < 0.001] and Side [F (1, 26) = 8.63, p < 0.01] were significant while the Vector x Side interaction was not significant [F (2, 26) = 2.12, p = 0.14]. As can be seen in Figure 6, intracerebral injections of UbC-GDNF DNPs into the denervated striatum of young rats produced significantly higher levels of GDNF protein than that observed after an injection of these same DNPs into the intact striatum. A similar effect was observed following the intracerebral injections of GFAP-GDNF DNPs into the lesioned and intact striata of young rats. Comparisons of Vector within the lesioned or intact striatum were not significant for UbC-GDNF vs. GFAP-GDNF groups. GDNF values were not significantly different between lesioned and intact striatum for animals that received injections of the negative control, UbC-Luc; this result suggests that the lesion alone did not produce increased levels of GDNF. Average dopamine depletion in the lesioned striatum was ≥ 98% of the intact striatum for all groups of animals which verifies all animals received severe lesions (see Table I).

Figure 6.

Protein values for GDNF in the lesioned or intact striatum of young rats one week following an intrastriatal injections of UbC-GDNF (4.3 μg/μl), GFAP-GDNF (4.4 μg/μl) or UbC-Luc (3.9 μg/μl) DNPs. DNA nanoparticles containing one of the three expression cassettes were injected in equivalent volumes (8.0 μl) of sterile saline into the left and right striatum 4 weeks after each animal received a unilateral 6-OHDA lesion. UbC-Luc (negative control) encodes for luciferase transcriptionally-controlled by the UbC promoter and does not encode for GDNF. One week after DNP injections, GDNF protein was measured in the lesioned or intact striatum using ELISA, and each bar on the graph represents the mean (± s.e.m.; n = 5 for all groups) of GDNF protein for each DNP.

Table I. Dopamine Content (ng/g).

| Striatum | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| Expression Cassette | Age | Intact | Lesioned | % depletion | |

|

|

|||||

| Study 3 | UbC-GDNF | young | 7,141 ± 273 | 138 ± 97 | 98 |

| GFAP-GDNF | young | 7,293 ± 330 | 78 ± 35 | 99 | |

| UbC-Luc | young | 8,622 ± 389 | 148 ± 87 | 98 | |

| Study 4 | UbC-GDNF | young | 10,864 ± 748 | 305 ± 146 | 97 |

| middle-age | 10,791 ± 835 | 100 ± 47 | 99 | ||

| old | 7,956 ± 382 | 204 ± 164 | 97 | ||

| GFAP-GDNF | young | 7,958 ± 906 | 131 ± 121 | 98 | |

| middle-age | 9,231 ± 618 | 136 ± 123 | 98 | ||

| old | 8,719 ± 686 | 20 ± 12 | 99 | ||

3.4 Study 4 - Effect of age on transgene expression in the lesioned striatum following intracerebral injections of GDNF DNPs incorporating a GFAP or UbC promoter

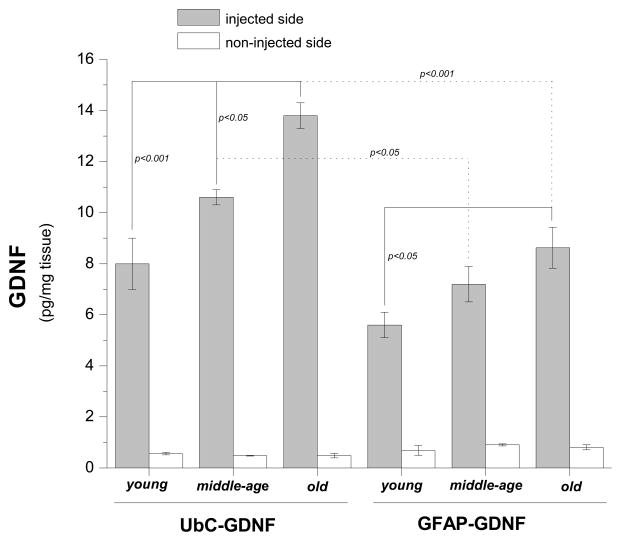

In this study all animals received unilateral 6-OHDA lesions and DNPs were injected directly into the lesioned striatum only of young, middle-aged or old rats, as described in Figure 2. Figure 7 is a graph of GDNF protein values plotted as a function of Vector (UbC-GDNF and GFAP-GDNF) and Age (young, middle-age and old). Because GDNF values were consistently low and nearly the same for all groups in the non-injected intact striatum, these data were excluded from the analysis and we ran two-way ANOVA using GDNF values from the lesioned side only; Vector and Age were set as the two independent variables. This analysis revealed no statistically significant interaction between Age and Vector [F (2, 18) = 1.45, p = 0.27], which should be interpreted as the effect of different levels of Age does not depend on which Vector is present. The main effect of Age was significant [F (2, 18) = 14.31, p < 0.001]. Injections of UbC-GDNF DNPs into the denervated striatum resulted in an age-related increase in GDNF expression. For Age within UbC-GDNF comparisons, statistical significance was observed between young vs. old and middle-age vs. old but not young vs. middle-age (Figure 7). Injections of GFAP-GDNF DNPs into the denervated striatum also resulted in an age-related increase in GDNF expression; however, for Age within GFAP-GDNF comparisons, statistical significance was only observed between young vs. old. The main effect of Vector was also significant [F (1, 18) = 33.50, p < 0.001]. Comparisons of Vector within the middle-age group and Vector within the old group were statistically significant while Vector within the young group was not significantly different; this latter comparison is consistent with the results from Study 2 in which we observed that GDNF values in the lesioned striatum of young animals were not statistically different between these two vectors. Average dopamine depletions in the lesioned striatum were ≥ 97% of the intact striatum for all age groups and verifies all animals received severe lesions (see Table I).

Figure 7.

Protein values for GDNF in brain tissue one week following injections of UbC-GDNF (4.3 μg/μl) or GFAP-GDNF (4.4 μg/μl) DNPs into the lesioned striatum of young (5 month old), middle-age (15 month old) or old (22 month old) rats. DNA nanoparticles containing either plasmid were injected in equivalent volumes (12.0 μl) into the lesioned striatum 4 weeks after each animal received a unilateral 6-OHDA lesion. One week later GDNF protein was measured in the lesioned (injected) or intact (non-injected) striatum using ELISA, and each bar on the graph represents the mean (± s.e.m.; n = 4 for all groups) of GDNF protein for each DNP.

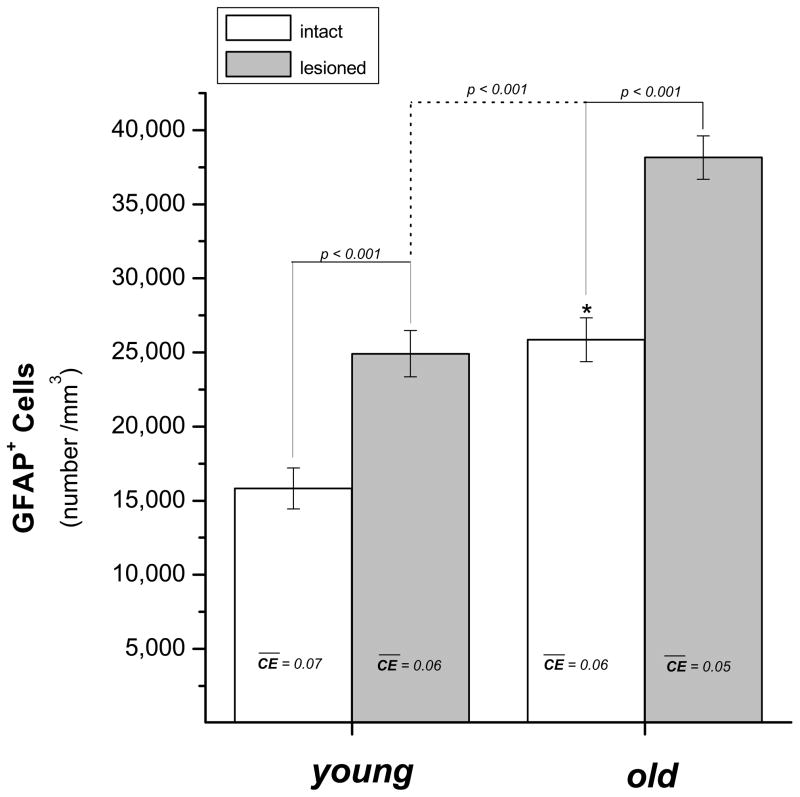

3.5 Study 5 - Stereological counts of GFAP+ cells in the intact and denervated striatum of aging animals

Young and old rats were given unilateral 6-OHDA lesions and then 5 weeks later we sectioned the brain and quantified the number of GFAP+ cells located in the same area of the striatum in which we targeted the DNP injections in Study 4. Estimates of cell counts and the volume of the striatum that was probed were determined stereologically and then counts of GFAP+ cells were adjusted for volume (counts/mm3). Age (young or old) and Side (denervated or intact) were the independent variables and the number of GFAP+ cells was the dependent variable. The results of this analysis revealed significant main effects of Age [F (1, 15) = 56.77, p < 0.001] and Side [F (1, 15) = 48.90, p < 0.001] while the Age x Side interaction was not significant [F (1, 15) = 1.96, p = 0.20]. Statistical analysis of striatal volume probed for each animal indicated no significant difference between the group means (F (1, 15) = 0.01, p = 0.93]. Both young and old animals showed lesion-induced increases of GFAP+ cells as well as a significant age-related increase in the number of GFAP+ cells in both the lesioned and intact striatum (Figure 8). While not quantified in this study, we did observe a qualitative increase in GFAP immunohistochemistry in the lesioned ventral midbrain for both young and old animals.

Figure 8.

Stereological analysis of GFAP+ cells in the lesioned and intact striatum of young (5 month old; n = 3) and old (22 month old; n = 3) rats. All rats in each age group received unilateral 6-OHDA lesions and brain tissue was collected for histological analysis 5 weeks after the lesion. CE = mean coefficient of error. *p< 0.05, old intact vs. young intact.

Table II summarizes how the changes in astrocytes (Δ Astroctyes) compare to the changes in GDNF transgene expression (Δ GDNF) observed in Studies 3 and 4. The effect of lesion, which was only determined in young animals, produced a 75% increase in the number of GFAP+ cells in the denervated striatum and we observed similar increases in GDNF transgene expression in the denervated striatum of animals treated with both GFAP-GDNF and UbC-GDNF DNPs. Likewise, the effect of aging produced a 53% increase in the number of GFAP+ cells in the denervated striatum and this compared to a 52% increase in GDNF transgene expression for animals treated with GFAP-GDNF DNPs or a 70% increase for animals treated with UbC-GDNF DNPs.

Table II.

Percent Change in Astrocytes & GDNF Levels

| Δ Astrocytes | Δ GDNF | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| GFAP-GDNF | UbC-GDNF | ||

| Lesion (young only) | ↑ 75% | ↑ 80% | ↑ 87% |

| Age (young vs. old) | ↑ 53% | ↑ 52% | ↑ 70% |

4. Discussion

The results of this study extend our previous finding that transgene expression induced by intracerebral injections of DNPs is increased in brain regions where there is on-going neurodegeneration (Fletcher et al., 2011). In the present study we used two different DNPs that incorporated two different promoters, one specific for expression in astrocytes and one non- specific promoter that was previously demonstrated to be active in both neurons and glia (Yurek et al., 2009b). Intracerebral injections of both DNPs showed increased transgene expression when the variables of age and neurodegeneration were factored into the data analysis.

In a previous aging study we observed that 6-OHDA lesions could induce an immediate up-regulation of endogenous GDNF in the lesioned striatum of young but not old animals and the up-regulation was sustained for 1–2 weeks post-lesion (Yurek and Fletcher-Turner, 2001); however, by the 4th post-lesion week GDNF levels in lesioned striatum of young animals returned to normal. In a primate study, aging and neurodegeneration did not significantly alter striatal GDNF levels in the denervated striatum of hemiparkinsonian monkeys treated with MPTP (Collier et al., 2005). Thus, it is unlikely that the increase of GDNF observed at the 5th post-lesion week in the lesioned striatum of young animals transfected with GDNF-encoding DNPs is simply due to individual striatal cells producing more endogenous GDNF per cell. If this was the case, then we should have observed an increase of endogenous GDNF production in the denervated striatum transfected with the negative control UbC-Luc DNPs, which we did not observe (Figure 6). Moreover, in the present study we detected the highest levels of GDNF in the transfected/lesioned striatum of old animals despite our previous finding that there was no significant up-regulation of endogenous GDNF at any of the post-lesion time points in the lesioned striatum of old animals. There was a significant increase of GDNF protein expression in the injected versus non-injected denervated striatum in young animals for both the UbC and GFAP promoters (Figure 6), directly demonstrating the activity of the GDNF DNPs. Therefore, it is more likely a mechanism[s] other than an increase in the synthesis of endogenous GDNF per cell is responsible for the up-regulation of GDNF in the lesioned/aging striatum transfected with GDNF-encoding DNPs.

The hGFAP promoter has been well characterized previously and shown to direct high levels of astrocyte-specific expression of a reporter gene in transgenic mice (Brenner and Messing, 1996). In several reports transgene expression using the same hGFAP promoter was restricted to astrocytes and radial glia (Gong et al., 2000, Do Thi et al., 2004) and cell-type specificity was confirmed by co-localization with GFAP immunoreactivity (Brenner et al., 1994, Zhuo et al., 1997). Similarly, a recent study using AAV1/2, which was thought to confer transgene expression primarily in neurons after direct injection into brain, demonstrated that GFAP promoter-driven GFP expression was found to be highly specific for astrocytes following vector infusion to the brain of neonate and adult mice (von Jonquieres et al., 2013). Our immunohistochemical study confirmed intracranial injections of GFAP-GFP DNPs transfected striatal cells with an astrocyte morphology and co-localized to cells with astrocytic immunoreactivity. Given the specificity of the hGFAP promoter for expression in astrocytes we observed using GFAP-GFP DNPs, it is very likely that increased GDNF expression in the striatum following intracerebral injections of GFAP-GDNF DNPs also reflects GDNF produced by transfected astrocytes alone.

We did not attempt to quantify GFP+ cells following intracerebral injection of GFAP-GFP DNPs because it was our observation there was a heterogeneous distribution of GFP+ cells around the injection site, which would have produced inaccurate estimations of cell numbers. Instead, we measured the changes in GFAP+ cells in the non-transfected striatum in order to demonstrate that there is a concomitant up-regulation of astrocytes in the lesioned/aged brain that coincides with increases in transgene expression. There are some close parallels between the age/lesion induced increases in GDNF transgene expression and the age/lesion induced increases in astrogliosis. For instance, in study 4 we observed that lesioned animals treated with GFAP-GDNF DNPs show a 52% increase in GDNF levels in the lesioned striatum between the young and old groups while a closely matched 53% increase of GFAP+ cells in the lesioned striatum is also observed for these same two age groups. In study 3 we observed that both GFAP-GDNF and UbC-GDNF DNPs produced GDNF levels in the lesioned striatum of young animals that were approximately 80% higher than in the intact striatum; stereological counts of GFAP+ cells in the striatum of young animals were 75% greater in the lesioned striatum when compared to the intact striatum. Other studies have shown similar increases in transgene activity linked to the astrocyte-specific expression of GFAP. For instance, transgenic mice carrying the LacZ reporter gene linked to the hGFAP promoter showed significant increases in LacZ expression in the injured striatum when compared to the intact striatum (Brenner et al., 1994); this same study also used double-labeling techniques to demonstrate that LacZ expression was almost exclusively co-localized to astrocytes.

Levels of GDNF in the lesioned striatum of old animals are also significantly higher than in the lesioned striatum of young animals following injections of UbC-GDNF DNPs; however, it appears that the 70% increase of GDNF levels in the old animals cannot be solely attributed to a 48% increase in astrocytes. First, we must consider that the UbC promoter is active in several cell types and it was not designed to be active specifically in astrocytes, as were the GFAP-GDNF DNPs. Therefore, changes in factors other than gliosis, which remain unknown at this time, might occur during aging and may contribute to this enhanced expression following treatment with UbC-GDNF DNPs. It is not known if the UbC and GFAP promoters function at the same activity in neurons and astrocytes, respectively, and therefore direct comparison of these two promoters may not be appropriate in non-denervated striatum where both populations of cells are present. However, it is clear that some factor[s] of aging contribute to the increased expression of transgene in UbC-GDNF DNPs, and it is very likely that increased gliosis is a contributing factor.

In most of our in vivo studies where we compared UbC-GDNF and GFAP-GDNF DNPs, we have observed higher transgene expression in brain tissue transfected with UbC-GDNF than with GFAP-GDNF. In earlier studies we demonstrated CMV-eGFP DNP (compacted pZeoGFP5.1) transfected both neurons and glia (Yurek et al., 2009b). It is conceivable the difference we observe between these two compacted plasmids may reflect the specificity of the GFAP-GDNF expression cassette for transgene expression only in astrocytes; that is, the sum total of transgene expression in brain tissue following an injection of GFAP-GDNF DNPs is that produced by astrocytes alone while total transgene expression in brain tissue following an injection of UbC-GDNF DNPs is that produced by both neurons and astrocytes.

We observed lower tissue levels of GDNF in the denervated striatum of animals in the aging studies (Study 4, Figure 7) when compared to GDNF tissue levels in the lesioned striatum of animals in Study 3 (Figure 6). This difference is most likely due to a dilution effect. In Study 3, striatal tissue was dissected from brain sections that were approximately 2 millimeters in thickness while in the aging study DNP injections occurred over a larger area of the striatum and the dissected brain sections were approximately 3 millimeters in thickness. The thicker brain sections most likely contained a higher amount of tissue that was not transfected by DNPs when compared to the thinner sections; therefore, it is not surprising that protein levels per tissue weight were lower in the aging study.

Astrocytic GDNF expression may represent an efficient alternative to current gene therapeutic strategies for the treatment of PD. Studies using viral vectors and in particular, AAV, have shown long distance axonal transport in both the antero- and retrograde direction after injection into the brain (Ciesielska et al., 2011, Salegio et al., 2013, Castle et al., 2014) and thus multiple brain sites can be affected by a single injection of AAV if the vector encodes for a neuronal specific promoter. A recent study using AAV vectors to express GDNF in astrocytes of MPTP-treated mice reported protection of dopaminergic neurons and their projections, dopamine (DA) synthesis and behavior; in this case astrocyte-derived GDNF demonstrated the same efficacy as neuron-derived GDNF (Drinkut et al., 2012). Moreover, this study demonstrated that astrocyte transgene expression does not result in spread to the contralateral side of the brain or transport to brain regions distal to the injection site, which can occur with AAV-based neuronal transgene expression. Previously we reported that direct intracerebral injections of DNPs into the striatum utilizing the UbC promoter resulted in local expression of transgenes without any evidence of antero- or retrograde transport to other brain regions (Yurek et al., 2009b); however, we did observe detectable transgene expression in the eyes of rats that received injections of similar UbC-Luc DNPs (compacted pUL3) into the ventral midbrain, and this was most likely due to some DNPs distributing along the injector needle track to optic nuclei/tracts within the ventral midbrain and then their subsequent retrograde axonal transport to the retina via the optic pathways (Yurek et al., 2011). Nonetheless, astrocytic expression may provide the best strategy for achieving local delivery of a transgene in brain tissue without affecting off-target brain regions.

While not quantified in this study, we did observe an up-regulation of astrocytes in the lesioned ventral midbrain. This observation is consistent with other studies that have reported an up-regulation of astrocytes in the ventral midbrain following degeneration of the nigrostriatal pathway in animal models of PD (Rodrigues et al., 2004) as well as in human PD (Miklossy et al., 2006). This ventral midbrain astrogliosis may be important in designing experiments for testing the therapeutic potential of DNPs. Typically DNPs produce transgene expression that is highly localized and at lower levels than viral vectors. Therefore, expressing neurotrophic factors as a means to protect or restore function in degenerating cells may be important in both the terminal regions as well as cell body region. While earlier viral vectors studies demonstrated that striatal expression of GDNF is the most effective approach to protecting the function of dopamine neurons and does not require additional expression in the midbrain (Kirik et al., 2000), more recent studies have provided evidence that intrastriatal injections of AAV vectors can produce both anterograde and/or retrograde transport of transgene to the midbrain or other brain regions (Ciesielska et al., 2011, Salegio et al., 2013). This complicates the interpretation of the earlier studies in terms of whether or not GDNF was exclusively expressed in the striatal region only. It is conceivable that expression of GDNF in the midbrain might have contributed to the protective effects that were observed following intrastriatal administration of these AAV vectors. Ongoing neuroprotection PD studies with UbC-GDNF and GFAP-GDNF DNPs are evaluating individual and combined striatal and nigral injection sites. Moreover, DNPs appear to be fairly inert when injected into brain tissue and no acute or long term toxicity has been reported in the brain (Yurek et al., 2009b, Yurek et al., 2011) or other targeted organs in animals (Ziady et al., 2003b, Cai et al., 2009) or humans (Konstan et al., 2004); therefore, DNPs should be fairly safe when injected into multiple brain sites.

This study was designed to examine the short-term expression of the GDNF transgene only; no attempt was made to assess the neuroprotective properties of the DNPs. The lesion model used in this study produced an almost complete lesion of the nigrostriatal pathway at the time the DNPs were injected into the brain. Given the severity of the lesion, the delayed timing of the DNP injection after the lesion and the short duration of the DNP treatment, we did not expect to observe any significant neurotrophic effect of the DNPs. However, it should be noted that in a previous study we observed neurotrophic effects of UbC-GDNF encoding DNPs on fetal cells engrafted into the brain (Yurek et al., 2009a). Nevertheless, the extent of neurodegenerative cell loss at the time a neuroprotective therapy is implemented is an important variable and will undoubtedly have an effect on the overall success of any neuroprotective therapy. In cases of severe cell loss there may be very few or no cells with the capacity to respond favorably to the therapy. For this reason, animal models using severe lesions or clinical trials using patients with late-stage neurodegenerative disorders may not be the best candidates for neuroprotective studies. In future studies we plan to assess the neuroprotective potential of DNPs encoding for neurotrophic factors in animals with less severe lesions of the nigrostriatal pathway.

5. Conclusions

The results of this study provide unequivocal evidence of increased transgene expression in brain following the intracerebral injections of DNPs that are sensitive to age-related and/or pathological changes in the brain. We also provide correlative data that shows the increase in transgene activity may be related to increased gliosis that occurs in the neurodegenerative state or aged brain. Overall, these findings indicate that the transfection potential of GDNF DNPs is well matched to the pathophysiology of neurodegenerative disorders in older patients, such as PD, where increased gliosis may augment expression levels of therapeutic proteins.

Transgene expression in brain is sensitive to aging and pathology

Transgene expression in astrocytes increases directly with age and severity of neurodegeneration.

Transfection potential of DNA nanoparticles is well matched to the pathophysiology of neurodegenerative disorders in aging brain

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health R01 NS75871 (DMY) and S10 RR027463 (DMY). The authors would also like to thank Dr. Peter Mouton for his assistance with the stereology studies.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

Dr. Mark J. Cooper is an employee of Copernicus Therapeutics, holds stock in the company, and is a co-inventor on patents covering various DNP and transgene expression technologies.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Brenner M, Kisseberth WC, Su Y, Besnard F, Messing A. GFAP promoter directs astrocyte-specific expression in transgenic mice. J Neurosci. 1994;14:1030–1037. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-03-01030.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner M, Messing A. GFAP Transgenic Mice. Methods. 1996;10:351–364. doi: 10.1006/meth.1996.0113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai X, Nash Z, Conley SM, Fliesler SJ, Cooper MJ, Naash MI. A partial structural and functional rescue of a retinitis pigmentosa model with compacted DNA nanoparticles. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5290. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cass WA, Harned ME, Peters LE, Nath A, Maragos WF. HIV-1 protein Tat potentiation of methamphetamine-induced decreases in evoked overflow of dopamine in the striatum of the rat. Brain Res. 2003;984:133–142. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)03122-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castle MJ, Gershenson ZT, Giles AR, Holzbaur EL, Wolfe JH. Adeno-associated virus serotypes 1, 8, and 9 share conserved mechanisms for anterograde and retrograde axonal transport. Hum Gene Ther. 2014;25:705–720. doi: 10.1089/hum.2013.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciesielska A, Mittermeyer G, Hadaczek P, Kells AP, Forsayeth J, Bankiewicz KS. Anterograde axonal transport of AAV2-GDNF in rat basal ganglia. Mol Ther. 2011;19:922–927. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collier TJ, Dung Ling Z, Carvey PM, Fletcher-Turner A, Yurek DM, Sladek JR, Jr, Kordower JH. Striatal trophic factor activity in aging monkeys with unilateral MPTP-induced parkinsonism. Exp Neurol. 2005;191(Suppl 1):S60–67. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dervan AG, Meshul CK, Beales M, McBean GJ, Moore C, Totterdell S, Snyder AK, Meredith GE. Astroglial plasticity and glutamate function in a chronic mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Exp Neurol. 2004;190:145–156. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do Thi NA, Saillour P, Ferrero L, Dedieu JF, Mallet J, Paunio T. Delivery of GDNF by an E1,E3/E4 deleted adenoviral vector and driven by a GFAP promoter prevents dopaminergic neuron degeneration in a rat model of Parkinson’s disease. Gene Ther. 2004;11:746–756. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drinkut A, Tereshchenko Y, Schulz JB, Bahr M, Kugler S. Efficient gene therapy for Parkinson’s disease using astrocytes as hosts for localized neurotrophic factor delivery. Mol Ther. 2012;20:534–543. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher AM, Kowalczyk TH, Padegimas L, Cooper MJ, Yurek DM. Transgene expression in the striatum following intracerebral injections of DNA nanoparticles encoding for human glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor. Neuroscience. 2011;194:220–226. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.07.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong YH, Parsadanian AS, Andreeva A, Snider WD, Elliott JL. Restricted expression of G86R Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase in astrocytes results in astrocytosis but does not cause motoneuron degeneration. J Neurosci. 2000;20:660–665. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-02-00660.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon MN, Schreier WA, Ou X, Holcomb LA, Morgan DG. Exaggerated astrocyte reactivity after nigrostriatal deafferentation in the aged rat. J Comp Neurol. 1997;388:106–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirik D, Rosenblad C, Bjorklund A, Mandel RJ. Long-term rAAV-mediated gene transfer of GDNF in the rat Parkinson’s model: intrastriatal but not intranigral transduction promotes functional regeneration in the lesioned nigrostriatal system. J Neurosci. 2000;20:4686–4700. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-12-04686.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konstan MW, Davis PB, Wagener JS, Hilliard KA, Stern RC, Milgram LJ, Kowalczyk TH, Hyatt SL, Fink TL, Gedeon CR, Oette SM, Payne JM, Muhammad O, Ziady AG, Moen RC, Cooper MJ. Compacted DNA nanoparticles administered to the nasal mucosa of cystic fibrosis subjects are safe and demonstrate partial to complete cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator reconstitution. Hum Gene Ther. 2004;15:1255–1269. doi: 10.1089/hum.2004.15.1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G, Li D, Pasumarthy MK, Kowalczyk TH, Gedeon CR, Hyatt SL, Payne JM, Miller TJ, Brunovskis P, Fink TL, Muhammad O, Moen RC, Hanson RW, Cooper MJ. Nanoparticles of compacted DNA transfect postmitotic cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:32578–32586. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305776200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long JM, Kalehua AN, Muth NJ, Calhoun ME, Jucker M, Hengemihle JM, Ingram DK, Mouton PR. Stereological analysis of astrocyte and microglia in aging mouse hippocampus. Neurobiol Aging. 1998;19:497–503. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(98)00088-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miklossy J, Doudet DD, Schwab C, Yu S, McGeer EG, McGeer PL. Role of ICAM-1 in persisting inflammation in Parkinson disease and MPTP monkeys. Exp Neurol. 2006;197:275–283. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan TE, Rozovsky I, Goldsmith SK, Stone DJ, Yoshida T, Finch CE. Increased transcription of the astrocyte gene GFAP during middle-age is attenuated by food restriction: implications for the role of oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med. 1997;23:524–528. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(97)00120-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Callaghan JP, Miller DB. The concentration of glial fibrillary acidic protein increases with age in the mouse and rat brain. Neurobiol Aging. 1991;12:171–174. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(91)90057-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padegimas L, Kowalczyk TH, Adams S, Gedeon CR, Oette SM, Dines K, Hyatt SL, Sesenoglu-Laird O, Tyr O, Moen RC, Cooper MJ. Optimization of hCFTR lung expression in mice using DNA nanoparticles. Mol Ther. 2012;20:63–72. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. New York: Academic Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues RW, Gomide VC, Chadi G. Astroglial and microglial activation in the wistar rat ventral tegmental area after a single striatal injection of 6-hydroxydopamine. Int J Neurosci. 2004;114:197–216. doi: 10.1080/00207450490249338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salegio EA, Samaranch L, Kells AP, Mittermeyer G, San Sebastian W, Zhou S, Beyer J, Forsayeth J, Bankiewicz KS. Axonal transport of adeno-associated viral vectors is serotype-dependent. Gene Ther. 2013;20:348–352. doi: 10.1038/gt.2012.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Schipper HM. Astrocytes, brain aging, and neurodegeneration. Neurobiol Aging. 1996;17:467–480. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(96)00014-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng JG, Shirabe S, Nishiyama N, Schwartz JP. Alterations in striatal glial fibrillary acidic protein expression in response to 6-hydroxydopamine-induced denervation. Exp Brain Res. 1993;95:450–456. doi: 10.1007/BF00227138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stromberg I, Bjorklund H, Dahl D, Jonsson G, Sundstrom E, Olson L. Astrocyte responses to dopaminergic denervations by 6-hydroxydopamine and 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine as evidenced by glial fibrillary acidic protein immunohistochemistry. Brain Res Bull. 1986;17:225–236. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(86)90119-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas J, Wang J, Takubo H, Sheng J, de Jesus S, Bankiewicz KS. A 6-hydroxydopamine-induced selective parkinsonian rat model: further biochemical and behavioral characterization. Exp Neurol. 1994;126:159–167. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1994.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Jonquieres G, Mersmann N, Klugmann CB, Harasta AE, Lutz B, Teahan O, Housley GD, Frohlich D, Kramer-Albers EM, Klugmann M. Glial promoter selectivity following AAV-delivery to the immature brain. PLoS One. 2013;8:e65646. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida T, Goldsmith SK, Morgan TE, Stone DJ, Finch CE. Transcription supports age-related increases of GFAP gene expression in the male rat brain. Neurosci Lett. 1996;215:107–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yurek DM, Flectcher AM, Kowalczyk TH, Padegimas L, Cooper MJ. Compacted DNA nanoparticle gene transfer of GDNF to the rat striatum enhances the survival of grafted fetal dopamine neurons. Cell Transplant. 2009a;18:1183–1196. doi: 10.3727/096368909X12483162196881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yurek DM, Fletcher-Turner A. Differential expression of GDNF, BDNF, and NT-3 in the aging nigrostriatal system following a neurotoxic lesion. Brain Res. 2001;891:228–235. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)03217-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yurek DM, Fletcher AM, McShane M, Kowalczyk TH, Padegimas L, Weatherspoon MR, Kaytor MD, Cooper MJ, Ziady AG. DNA nanoparticles: detection of long-term transgene activity in brain using bioluminescence imaging. Mol Imaging. 2011;10:327–339. doi: 10.2310/7290.2010.00053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yurek DM, Fletcher AM, Smith GM, Seroogy KB, Ziady AG, Molter J, Kowalczyk TH, Padegimas L, Cooper MJ. Long-term transgene expression in the central nervous system using DNA nanoparticles. Mol Ther. 2009b;17:641–650. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuo L, Sun B, Zhang CL, Fine A, Chiu SY, Messing A. Live astrocytes visualized by green fluorescent protein in transgenic mice. Dev Biol. 1997;187:36–42. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziady AG, Gedeon CR, Miller T, Quan W, Payne JM, Hyatt SL, Fink TL, Muhammad O, Oette S, Kowalczyk T, Pasumarthy MK, Moen RC, Cooper MJ, Davis PB. Transfection of airway epithelium by stable PEGylated poly-L-lysine DNA nanoparticles in vivo. Mol Ther. 2003a;8:936–947. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2003.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziady AG, Gedeon CR, Muhammad O, Stillwell V, Oette SM, Fink TL, Quan W, Kowalczyk TH, Hyatt SL, Payne J, Peischl A, Seng JE, Moen RC, Cooper MJ, Davis PB. Minimal toxicity of stabilized compacted DNA nanoparticles in the murine lung. Mol Ther. 2003b;8:948–956. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]