Abstract

Objective

Measure comprehensiveness of California campus tobacco policies.

Participants

16 campuses representing different regions, institution types, and policies. Research occurred June-August, 2013.

Methods

Comprehensiveness was scored using American College Health Association's (ACHA) Position Statement on Tobacco. The Institutional Grammar Tool was used to breakdown policy statements into Strategies, Norms, or Rules. Differences in ACHA score and number of Strategies, Norms, and Rules were assessed by region, policy, and institution type.

Results

Median ACHA score was 0.35 (scale of 0–1). Schools with 100% tobacco-free policies had highest ACHA scores, but failed to address relationships between schools and tobacco companies. Less than half the schools assessed (7/16) had Rules (enforceable penalties related to policies). In 67% of the policy statements, individuals doing the action were implied (not specifically stated).

Conclusion

Campuses should address ACHA recommendations related to campus relationships with tobacco companies, include enforceable rules, and specify individuals and entities covered by policy.

Keywords: campus tobacco policies, policy, smoking, tobacco

Tobacco smoke, including secondhand smoke, causes cancer, heart and lung disease, and premature death.1 College is a crucial period to prevent smoking initiation and progression from experimentation to established smoking, as well as to promote cessation, because virtually all smokers begin before age 26.1 In 2010, 41% of individuals (21 million people) between the ages of 18 and 24 were in college,2 and in 2011, 24% of college students (age 18 through 22) smoked in the past month.3

College students are emerging adults, a developmental period marked by increased freedom and exploration,4 which may lead to experimentation with substance use. In addition, the major cigarette companies have agreed to accept limitations on advertising to children under age 18,5 which makes college age the first time the tobacco companies can legally directly and aggressively target young people. Tobacco companies use marketing strategies that leverage the fact that these college students are entering new environments and are often more susceptible to social pressure.6

Tobacco-free college campus policies have the potential to be high impact interventions to reduce smoking and secondhand smoke exposure among college students.7–9As of July 2013 there were almost 800 colleges with 100% tobacco-free policies10 across regions, type of school (two- and four-year institutions) and communities (e.g., rural and urban),11 including whole school systems and states enacting college smoke- and tobacco-free policies.12–13 Comprehensiveness of tobacco-policies is a particularly important consideration as policies with exemptions in the form of designated areas may create confusion making the policies more difficult to implement and enforce, and still leave individuals exposed to secondhand smoke. In 2011 in North Carolina, Lee and colleagues14 found 0.6 cigarette butts per day deposited outside building entrances on campuses with 100% tobacco-free policies, compared to 1.7 butts per day on campuses with partial tobacco-free policies and 2.6 butts per day on campuses with no policy, suggesting dose-response between comprehensiveness of the policy and smoking on campus.

The American College Health Association (ACHA) recommends comprehensive tobacco-free polices, and outlines how to create a comprehensive policy with categories such as prohibition of cigarette/tobacco use, barring sales of tobacco/relationships with companies, and promoting the policy.15 These categories are further specified, for example, the campus relationship with tobacco companies is a category with specific items related to sales, advertising, and distribution of tobacco (see Appendix A). Therefore, assessment of compliance with the American College Health Association guidelines is an effective measure of the comprehensiveness of policies.11, 16

In 2010, Plaspohl and colleagues11 interviewed key informants from 162 of the 175 campuses that the American Lung Association had identified as having a tobacco-free policy regarding whether or not their institution followed each element of the guidelines, and found wide variation. For example, the ACHA recommends that campuses offer evidence-based tobacco cessation services, but only 54% of the campuses interviewed provided such services.11

Because of this variation, the ACHA is a useful tool for assessing if college campuses are enacting robust tobacco policies. Another important consideration when analyzing universities tobacco policies is assessing how these policies reflect how these institutions choose to operate. The Institutional Analysis Development framework17–18 provides a structure to systematically organize the relationships of actions and outcomes between individuals involved in creating, helping implement, or being effected by policies. The Institutional Grammar Tool (IGT)19 extends this framework to categorize individual policy statements into three types of shared prescriptions by the organization: (1) strategies, which are regularized plans to apply policies; (2) norms, which are prescriptions for policies that are implicitly enforced; and (3) rules, which are shared prescriptions for policies that are explicitly enforced.

This paper expands the literature in this area by presenting a method to measure policy comprehensiveness and wording using the ACHA guidelines as a standard as well as the Institutional Analysis and Development (IAD) Framework's Institutional Grammar Tool (IGT).17 Analyzing university policies using these methods allows for assessing both how well universities comply with the ACHA tobacco specific recommendation and assessing how institutions operationalize their regulatory policies via strategies, norms, and rules. Using such an approach allows for a more in-depth analysis of the strengths and weaknesses of universities' tobacco policy wording and design.

METHODS

Selection of Campuses

We selected 16 colleges and universities throughout California to include campuses from different regions (north, central, and southern California) to reflect different social, political, and cultural environments and campus sizes, different institution types (two- and four- year campuses), and tobacco policy types (100% tobacco-free, 100% smoke-free, smoke-free with designated areas, and policies that simply implement the minimum state-mandated requirements of not being allowed to smoke within a campus-owned building or vehicle, or within 20 feet from a main entrance).20 Campuses with the state-mandated requirements had policies that were implemented between 2003 and 2004, campuses that were smoke-free with designated areas had policies implemented between 2004–2009, campuses that were 100% smoke-free had policies implemented between 2003 and 2013, and those that were 100% tobacco-free had policies that were implemented between 2009 and 2013 (except for the case of 1 school which was tobacco-free since its inception) (Table 1). Approval to conduct this study was granted by the University of California, San Francisco’s Institutional Review Board.

Table 1.

Campuses for Study by Policy Type

| 100% Tobacco-free N=4 | Smoke-free with Designated Areas N=4 | ||||||||

| Region | Students | Campus Pop | Town Pop | Policy Date | Region | Students | Campus Pop | Town Pop | Policy Date |

| South | 2 year | 7,853 | 14,758 | 8/24/2009 | North | 4 year | 7,773 | 17,231 | 1/18/2005 |

| North | 4 year | 1,300 | 92,328 | 1921* | North | 2 year | 5,155 | 16,075 | 12/9/ 2009 |

| Central | 2 year | 17,000 | 56,974 | 4/10/2012 | South | 2 year | 32,000 | 137,122 | 8/5/2009 |

| South | 4 year | 39,271 | 3,729,621 | 4/22/2013 | Central | 4 year | 28,290 | 805,235 | 8/23/2004 |

| 100% Smoke-free N=4 | Minimum State-mandated Laws N=4 | ||||||||

| Region | Students | Campus Pop | Town Pop | Policy Date | Region | Students | Campus Pop | Town Pop | Policy Date |

| South | 4 year | 37,000 | 135,161 | 8/1/2013 | South | 4 year | 36,000 | 68,469 | 11/20/2003 |

| South | 2 year | 19,511 | 308,511 | 1/1/2003 | Central | 4 year | 30,448 | 971,372 | 5/15/2003 |

| Central | 2 year | 10,107 | 971,372 | 9/2009 | South | 2 year | 15,000 | 212,375 | 1/1/2004 |

| South | 2 year | 25,504 | 1,301,617 | 1/1/2007 | Central | 2 year | 100,000 | 805,235 | 1/1/2004 |

School has been smoke free since its inception

Policy Document Selection

Between June and August 2013, the relevant tobacco policy and implementation documents (including formal policies, implementation procedures, handbooks, and campus cessation services and additional resources) were obtained through online searches using keywords such as “tobacco” and “smoking” with the campus name supplemented with follow-up contacts with school officials. For this study, information available via written policies and the universities websites were used, but in two instances researchers contacted the university to follow-up. The first instance was for a campus that was identified as “smoke-free indoors only” but did not have any identifiable tobacco-policy for analysis using the IGT; their Office of Student Health stated they were complying with the state law20 that prohibits smoking within campus-owned buildings and vehicles and within 20 feet from a main entrance. In the second instance, a campus also did not have any written policies that could be analyzed using the IGT; this campus, however, stated on its website that it was 100% smoke-free, which goes beyond the minimum state-mandated requirement. The authors called this campus and confirmed that the campus was smoke-free and that they were still negotiating the terms of their policy. Because there was no written statement that adequately reflected the school's policy, for the IGT analysis the authors scored this school as having no written statement of the policy.

Policy Analysis

American College Health Association Guidelines

We developed a coding form (Appendix A) based on the ACHA Position Statement on Tobacco on College and University Campuses15 by expanding the one developed by Lee and colleagues16 to capture all aspects of the ACHA recommendations. The resulting 20-item scale scores school policies on 6 categories: prohibition of cigarette/tobacco use (i.e., smoking is prohibited 20 feet away from entrances), barring sales of tobacco/relationships with companies (e.g., the tobacco industry may not sponsor campus activities), promotion of the policy, programs and services available, plans for implementing the policy, and whether the campus has a tobacco taskforce.

A total ACHA score was calculated by dividing the number of ACHA guidelines a school implemented by 20, the number of guidelines. While scores can technically range from 0.0 to 1.0, the minimum possible score was 0.15 because three of the guidelines (no smoking inside buildings, no smoking inside vehicles, and no smoking 20 feet from the entrance of a building) were required under California State Law20 for all public buildings and vehicles.

The Institutional Grammar Tool

While the ACHA guidelines are useful for assessing how campuses specifically construct their tobacco policies, the Institutional Grammar Tool is a tool that can be used for any written policy statement. The IGT enhances our understanding of how the campus institution chooses to operate via their written policies by breaking down the elements of a policy into (1) strategies, which are regularized plans to apply policies; (2) norms, which are prescriptions for policies that are implicitly enforced; and (3) rules, which are shared prescriptions for policies that are explicitly enforced.

There are six main components in the IGT: the Attribute (A), the oBject (B), the Deontic (D), the aIm (I), the Condition (C) and the Or else (O) (abbreviated as ABDICO):

Attribute (A): the person performing the action described in the aIm, i.e. the University, the Campus Community, Department Heads, Offices, Students, Employees, the Tobacco Taskforce.

oBject (B): the receiver of an action described in the aIm, i.e. students, faculty, staff, campus (physical), and campus visitors.

Deontic (D): an indication of the forcefulness of the action in the aIm, i.e. prohibited, forbidden, shall, must.

aIm (I): the action of the policy performed by the Attribute, i.e. smoke

Condition (C): the location, duration, or date of the aIm, i.e. in designated smoking areas.

Or else (O): actions that will occur if the aIm is not followed, i.e. be referred to the Dean.

Policy statements were coded sentence by sentence using ABDICO and categorized into the three types of institutional statement (strategies, norms, or rules) based on the 6 ABDICO components they manifest:

- Strategies (regularized plans to apply policies) are defined as having AIC; for

The

University

Awill provide

signage

Iat University facility

entrances

C

= STRATEGY - Norms (prescriptions for policies that are implicitly enforced) are defined as having ADIC; for example:

The

District

A

prohibits

Doutdoor

smoking

Ion district owned property,

except in designated areas

C

= NORM - Rules (shared prescriptions for policies that are explicitly enforced) are defined as having ADICO; for example:

Individuals

A

must

Dcomply with

this policy

Iat all

times

Cor be referred to the

Campus Police

O= RULE - Strategies, Norms, and Rules can be constructed with or without an oBject. For example: f

The

University

Ato employees

students and

faculty

B

must provide

information

I

at all times

C

= STRATEGY

Coding

Each school was assessed using both the ACHA guideline 20-item scale and the IGT analysis. As the ACHA guideline functions as a checklist, the written policy as well as additional written statements and materials available on the campus's website were used to assess if the campus complied with the ACHA guideline. For the IGT analysis, the official written policy statement was parsed using the method already described.

A subsample of 4 schools were randomly selected and two coders (MR and DW) independently coded the schools using both the ACHA guidelines and the IGT analysis, then met with another researcher (AF) to discuss the coding, resolve discrepancies in interpretation, and formalize techniques for interpretation. The two researchers (MR and DW) then independently coded the remaining policies, after which the three researchers met again, to resolve remaining discrepancies. Two of the authors (AF and MR) have on-the-ground experience with implementing tobacco-free campus policies (at institutions not included in this study), which informed the consensus process.

Statistical Analysis

Medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) across the 16 schools were computed for overall ACHA score and each of the 6 ACHA category scores: prohibition of cigarette/tobacco use, barring sales of tobacco/relationships with companies, promotion of the policy, programs and services available, plans for implementing the policy, and whether the campus has a tobacco taskforce. Differences in total ACHA score were assessed by region and type of policy (100% tobacco -free, 100% smoke-free, smoke-free with exceptions, and following minimum state- 1mandated requirements) using the Kruskal-Wallis test and by two- vs. four- year school using the Mann-Whitney U test; both tests were chosen due to the fact that the data were not normally distributed and come from independent samples.

Medians and IQRs were also computed for the number of Strategies, Norms, and Rules both at the school level and for all schools combined. Because the data were not normally distributed, a Spearman’s Rank Order correlation was conducted to see if the number of Strategies in a policy correlated with the number of Rules, if the number of Norms in a policy correlated with the number of Rules, and if the number of Strategies in a policy correlated with the number of Norms. Differences in the number of Strategies, Norms, and Rules in policies were assessed by region and type of policy (100% tobacco -free, 100% smoke-free, smoke-free with exceptions, and following minimum state-mandated requirements) using the Kruskal-Wallis test and by two- vs. four- year school using the Mann-Whitney U test.

RESULTS

ACHA Guidelines

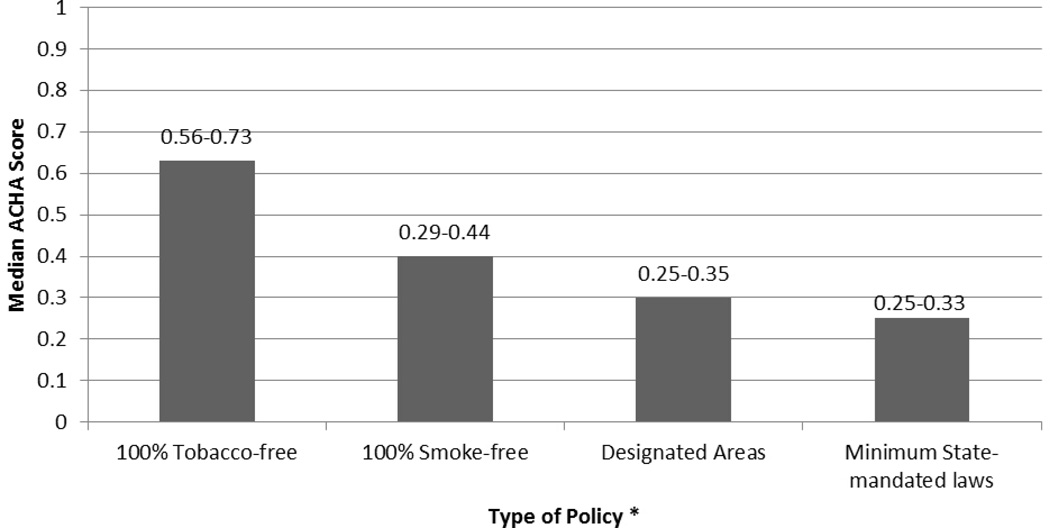

The median ACHA guideline score for all schools was 0.35 (IQR= 0.25–0.52) (Figure 1). No school completely implemented the ACHA guideline (i.e., scored 1.0). There were no significant differences for overall ACHA score by location (p=0.51) or school type (two vs. four) (p=0.33). There was a significant difference by type of policy with 100% tobacco-free schools having higher overall ACHA scores (p=0.01) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Median total ACHA score by policy (IQR).

All schools included aspects of policy which were required by law (no smoking within buildings or state-owned vehicles and no smoking 20 feet from the door). All schools addressed the topic of cigarette or tobacco use and, as one would expect, schools with the most restrictive policies (100% tobacco-free) scored the highest in these categories.

None of the schools addressed 4 of the 7 items related to the category of campus relations with the tobacco company: sponsorship of campus activities, sponsorship of athletic activities, recruitment by tobacco companies, and funding from tobacco companies. The only item in this category that half (8/16) of the schools addressed was that of tobacco sales on campus. All schools with tobacco-free policies had their policies posted clearly in student and employee handbooks. None of the schools that were smoke-free with designated areas had their policies clearly stated in student and faculty handbooks. Ten of the 16 schools promoted their policy.

Almost all the schools (14/16) had information available about cessation services or offered cessation services on campus and addressed how the policy would be implemented (14/16). Only 5/16 schools had wording in their policies that addressed the ACHA’s recommendation of having a tobacco task force.

IGT Policy Analysis

For all 16 schools combined, there were 197 institutional statements which were coded into Strategies (plans of action) Norms (prescribed actions which are thought to be informally enforced) and Rules (prescribed actions which are explicitly enforced). For all institutions combined, there were 70 Strategies, 106 Norms, and 21 Rules (Table 2). We ran tests to see if school policies with more statements of one kind would also have more statements of other kinds. To do this we ran a Spearman’s Rank Order correlation for the number of Strategies and Rules statements, the number of Norms and Rules statements, and for the number of Strategies and Norms statements. There was no correlation between the number of Strategies and Rules (rs = −0.43, p=0.11). There was also no significant correlation between the number of Norms and Rules (rs = −0.32, p=0.27). There was a significant correlation between the number of Strategies and Norms (rs = 0.57, p=0.03).

Table 2.

Number of Strategies, Norms and Rules for Two vs. Four-Year Schools

| Type of school* | Strategies N (%) |

Norms N (%) |

Rules N (%) |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Two-yr school | 29 (29.9) | 50 (51.5) | 18 (18.6) | 97 |

| Four-yr school | 41 (41.0) | 55 (55.0) | 4 (4.0) | 100 |

| Total | 70 (35.5) | 106 (53.8) | 21 (10.7) | 197 |

We assessed 9 two-year school and 7 four-year school

There was no significant difference in the number of strategies, norms, and rule by school type (p=0.13, 0.39, 0.27 respectively)

We also assessed if there were different numbers of Strategies, Norms, and Rules in school policy statements from two- versus four-year schools, from schools with different types of policies (100% tobacco-free, 100% smoke-free, smoke-free with exceptions, and following minimum state-mandated requirements), and school from different regions (Northern, Central, or Southern California).

For four-year school policies there was a median of 5 Strategies (IQR=4–8), 6 Norms (IQR=3–13) and 0 Rules (0–2). For two-year school policies, there was a median of 1.50 Strategies (IQR=0.25–6.70), 5 Norms (IQR=3–9), and 1 Rule (IQR=0–4.50). Despite descriptive differences in the number of Strategies, Norms, and Rules of two- vs. four-year schools, statistical tests show no significant differences in the number of Strategies (p= 0.13), Norms (p=0.39) and Rules (p=0.27) in two- versus four-year schools. While all schools had strategies and norms, less than half (7/16) had rules.

For schools with 100% tobacco-free policies had a median of 2.5 Strategies (IQR=0.25- 4.75), 4.5 Norms (IQR=1.50–11.25), and 1.5 Rules (IQR=−0.25–2.75), schools with 100% smokefree policies had a median of 5 Strategies (IQR=3–5), 6 Norms (IQR=5–6), and 0 Rules (IQR=0-0), schools that are smoke-free with designated areas had a median of 6.5 Strategies (IQR=2.75–12.50), 8 Norms (IQR=3.75–14.50), and 0.5 Rules (IQR=0–4), and schools with state-mandated minimum policies had a median of 0.5 Strategies (IQR=0–6.25), 3.5 Norms (IQR=2.25–13.75) and 0 Rules (IQR=0–1.50). There were no statistically significant differences by policy type for the number of Strategies (p=0.19), Norms (p=0.71), and Rules (p=0.72).

For schools from different locations, schools from the North had a median of 8 Strategies (IQR=4–8), 6 Norms (IQR=1–6), and 1 Rule (IQR=0–1), schools from Southern California had a median of 4 Strategies (IQR=1.25–7.20), 6 Norms (IQR= 3.50–12.20) and 0 Rules (IQR=0-0), schools from Central California had a median of 0.5 Strategies (IQ=0–4), 3.5 Norms (IQR=3–8.50) and 1 Rule (IQR=0–2.75). There were no statistically significant differences by location for the number of Strategies (p=0.11), Norms (p=0.67), and Rules (p=0.93).

The IGT analysis also allows for assessing policy statement by who is doing the action, the Attribute, and whom the action is directed at, the oBject. The Attribute can be specifically stated, for example "The University shall be completely tobacco-free effective the first day of the Fall semester, 2009." The Attribute, however, can also be implied, for example, in the sentence "Signs shall be posted at all entrances to campus grounds," the University is the implied Attribute. In instances where the Attribute is implied, unless an Attribute was specifically addressed in a preceding sentence that could be connected to the sentence with no specific Attribute, that Attribute was identified as a general entity such as the University or the campus community. The coders used contextual cues within the policy and their experiences as implementers of tobacco-free policies to decide who the Attribute was in instances when the Attribute was not specifically stated. In 128 instances, the university was the Attribute (68% implied), in 33 instances it was the general or campus community (51.5% implied), in 13 instances it was department heads or managers (0% implied), in 9 instances it was various offices (11% implied), in 8 instances it was students (0% implied), in 4 it was employees (0% implied), and in 2 it was a taskforce (0% implied) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Number of Strategies Norms and Rules by Attribute (Actor)

| Attribute (Actor) | Strategy N (%) |

Norm N (%) |

Rule N (%) |

Instances where attribute is Implied N (%) |

Total for Strategies Norms and Rules N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| University | 55 (43.0) | 73 (68.9) | 0 (0) | 87 (68.0) | 128 (65.0) |

| General/Campus community | 8 (6.3) | 14 (13.2) | 11 (52.4) | 17 (51.5) | 33 (16.7) |

| Dept Heads/Managers | 1 (0.8) | 12 (11.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 13 (6.6) |

| Offices | 5 (3.9) | 4 (37.7) | 0 (0) | 1 (11.1) | 9 (4.6) |

| Students | 0 (0) | 2 (1.9) | 6 (28.6) | 0 (0) | 8 (4.1) |

| Employees | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (3.8) | 0 (0) | 4 (2.0) |

| Taskforce | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (1.0) |

| Total | 70 (100) | 106 (100) | 21 (100) | 105 (53.3) | 197 (100) |

Table 4 gives an example breakdown of norms statements that had the university as the actor which accounted for 37% of all institutional statements. The deontic words (words used as prescriptions) were: “prohibits,” followed by “shall,” “permits,” and “is responsible for." Additionally, there were a number of aims for these prescriptions, with the majority centering on tobacco use. In only two instances was there was a specific oBject (or specified individuals on whom the action was directed) for the Norms statement. The first instance identified employees and students as individuals to whom “The University shall make available a list of cessation services,” the second instance identified employees students and visitors as individuals to whom “The University was responsible for publicizing information regarding the policy to.” In all other instances there was no individual or group of people that the actions of the university were specifically targeted to.

Table 4.

Assessment of Norms Statements with the University or District as the Actors

| Attribute | Deontic | Aim | Condition | Object |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The University (N=73) | Shall (N=12) | Be a smoke-free/tobacco campus (N=3) | Effective as of specific date | |

| Make available a list of/sponsor cessation services (N=1) | At all times | To employees and students | ||

| Post/provide/place signs (N=5) | At all times | |||

| A all entrances | ||||

| Throughout the campus | ||||

| Publicize/provide information (N=2) | At all times | |||

| In health Service Offices | ||||

| Publish notifications of designated areas (N=1) | At all times | |||

| Make available information/resources | ||||

| Is responsible for (N=2) | Publicizing/provide information about the policy (N=2) | At all times | To employees students and visitors | |

| Whenever changes to the policy occur | ||||

| Prohibits (N=51) | Advertising or promotion of tobacco products (N=1) | On property | ||

| Selling tobacco products (N=4) | On property | |||

| Smoking/tobacco use (N=46) | At all times | |||

| At university sponsored activities and events | ||||

| In buildings | ||||

| On property except in designated areas | ||||

| In vehicles | ||||

| On property | ||||

| Within 20/25 feet of main entrance | ||||

| Sponsorship of athletic intramural and other University events (N=1) | At all times | |||

| Permits (N=8) | Smoking/tobacco use (N=7) | For University sponsored productions | ||

| For research | ||||

| In designated areas |

There were fewer Rules than any other type of statement, with only three types of actors for such statements, the general community, students, and employees (Table 3). Table 5 illustrates the makeup of rules statements when students are the actors. The example of students was selected as smoke- and tobacco-free policies are often targeted at students. The prescription words were “shall,” “may not/must not,” or “may/must.” There was also the use of conditions, words that indicate where and when something can occur, that indicated penalties would only occur with repeated use, of if use occurred within housing facilities.

Table 5.

Assessment of Rules Statements with Students as the Actors

| Attribute | Deontic | Aim | Condition | Or Else |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Students (N=6) | May/Must (N=1) | Who go against the policy | Repeatedly | Be referred by the police to the Office of the Vice President for Student and Learning Services for violation of the Student Code of Conduct and Education Code section 76033(3). |

| Shall/should (N=3) | For not being compliant | At all times | Will receive a verbal warning and review of Policy and Administrative Procedure. | |

| Will be Referred to the Dean of Student Services for consultation and written reprimand for continual violation of | ||||

| Will be disciplined in accordance with applicable laws, regulations, Board Policies and Administrative Procedures | ||||

| May not/ must not (N=2) | Smoke | Within housing facilities | Or they will be found in violation of the License Agreement and are subject to judicial action and/or revocation of their license | |

| Or they may also be in violation of Education Code 89031, which is a misdemeanor |

COMMENTS

While there is a trend for colleges and universities to go smoke- and tobacco-free, it is important to consider what it means for a school to have a strong policy and how schools formulate their policies. We assessed schools with 4 different types of policies (ranging from 100% tobacco-free to minimum state-mandated rules). While 100% tobacco-free schools had higher ACHA scores than schools with less restrictive policies, these schools still failed to address all of the categories that the ACHA recommends for a comprehensive policy. In particular, few schools (tobacco-free and otherwise) addressed their relationships with tobacco companies. Smoke- and tobacco-free policies affect young people by creating a setting in which smoking and the use of tobacco is denormalized.21 In addition, adolescents who do not smoke but who are exposed to tobacco advertising are more likely to initiate smoking than those not exposed to such advertising,22 and smoking among college students is associated with tobaccoattending industry sponsored events.23 Having statements that limit smoking or tobacco use while at the same time allowing for, or not expressly prohibiting, the distribution, advertisement, or sales of tobacco products on campus could result in less impactful policies.

It may be that schools with less restrictive policies and lower ACHA scores have made an affirmative decision not to create comprehensive policies. While many two- and four- year colleges are deciding to go smoke- and tobacco-free, such policies are still at the vanguard of tobacco control and may run against concepts related to individual choice. For example, one community college district policy states that “The District, therefore, discourages the practices of smoking, but provides for opportunities for those who smoke as long as there is no impact upon the rights and health of non-smokers.” This statement suggests that the rights of smokers should be given equal, if not higher priority, to that of non-smokers. Such equivocating hinders the effectiveness of tobacco and smoking policies, with schools with designated areas having higher rates of cigarettes litter than schools with no exemptions.14

While schools with 100% tobacco-free policies had higher ACHA scores (p=0.01) they did not have more Rules (p=0.72) than schools with other types of policies. While all schools in this study had a plan for enforcement, less than half (7/16) had Rules specifying penalties when individuals went against the policy. It may be that schools with tobacco-free policies are hoping to change social norms and thus have implementation strategies that “depend on the thoughtfulness of the campus community” rather than formal enforcement. Using a social-norms approach with no explicit penalty, however, may be counterproductive, and result in feelings of dissatisfaction over a policy that exists in name only.24

This is the first study to our knowledge that used the IGT18–19 to assess college tobacco policies. This is also the first study to our knowledge that attempts to statistically assess the relationship between Strategies, Norms, and Rules. More than half (53%) of the statements schools used in their policies were Norms, or statements that described prescribed actions that tend to be enforced by participants. Studies utilizing the IGT to analyze policies in other arenas, such as those related to US transportation, also found that the bulk of a written policy was made up of Norms statements.18, 25 The second most common type of statement in our study were Strategies (36%), regularized plans of action, and the least common types of statements were Rules (11%), statements that had a prescribed action and an explicit penalty for failure to do the action.

In over a third of the statements, the actor engaging in the policy was identified as the university and in 68% of these instances the actor was implied. This lack of specificity over who is doing the action may also lead to policies that are unclear and difficult to enact because there is debate over which entity or organization is responsible for which role.

There was no significant correlation between the number of Strategies and Rules (p=0.11) or the number of Norms and Rules (p=0.27), though there was a significant positive correlation between the number of Strategies and Norms (p=0.027). This result suggests that policies get longer (and possibly more detailed) through the addition of Norms and Strategies statements, not through the addition of Rules statements. This study found no significant differences in the number of Strategies, Norms, and Rules in school tobacco-policies by type of school, type of policy, or region.

While it is important to create policies with regularized plans for how to apply policies (Strategies) and prescriptions that are implicitly enforced (Norms), it may be particularly important in the case of tobacco-free policies to ensure that these written policies also include explicitly enforceable Rules statements. Without clear enforcement rules these policies may be perceived as "a total joke"26 it is also possible that individuals who would comply are unable to do so because of lack of awareness regarding the policy. For example, Russette and colleagues found that 70% non-compliant smokers on a US state-supported campus with a tobacco-free policy did not know they were not in compliance.27 This study assessed campus compliance with ACHA guideline and the way they structured their written policies into Strategies, Norms, and Rules. Future studies should evaluate policies outside of California and more work is needed to assess the link between policy adoption and on the ground implementation.

Limitations

We used information available in the official written policy of the campus and information available via the campus's website. It is possible that a campus may have informal unwritten policies related to tobacco or written policies that we did not find using these methods. Due to the small sample size of this study, it is likely that there was not adequate power to correctly reject the null hypothesis. Additionally, it is possible that factors such as school size impacted how well the policies followed ACHA guideline and how the policy statements were structured.

Conclusion

Colleges are being seen more and more as a place to model and establish healthy behavior patterns. As a result, there is a large push for schools to go tobacco-free. As more and more campuses decide to adopt tobacco-free policies, they face issues regarding how to most effectively create, implement, and maintain such policies. This paper uses two approaches (the ACHA and the IGT) to assess the comprehensiveness and wording of 16 colleges throughout California. While schools that had 100% tobacco-free policies also had the highest ACHA scores, they still failed at addressing issues related to relationships between schools and tobacco companies. Less than half the schools assessed had Rules statements, or enforceable penalties related to policies. The lack of Rules statements may be an indicative of an approach that privileges changing social-norms vs. enforcement, but such an approach may backfire with students, faculty, and staff viewing such policies as ineffective and in name only. Campus policies can be strengthened by using the ACHA recommendations as a step-by-step guideline 2for creating a policy, including enforceable rules, and ensuring that the individuals and entities who are responsible for engaging in the action and toward whom the action is directed are clearly specified.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

This manuscript was supported in part by grants from California’s Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program, numbers 9KT-0072, 20GT-0099, and 21HT-0002, and 22FT-0069 and the National Cancer Institute Grants CA-061021 and CA-113710. The funding agencies played no role in the conduct of the research or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer: This is a version of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to authors and researchers we are providing this version of the accepted manuscript (AM). Copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof will be undertaken on this manuscript before final publication of the Version of Record (VoR). During production and pre-press, errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal relate to this version also.

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

REFERENCES

- 1.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Preventing tobacco use among youth and young adults. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Office of the Surgeon General; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Center for Education Statistics. [Accessed 08 Aug, 2013];Chapter 3: Postsecondary education. 2011 http://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d11/ch_3.asp.

- 3.U.S Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. [Accessed 08 Aug, 2013];Results from the 2011 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. 2011 http://www.samhsa.gov/data/nsduh/2k11results/nsduhresults2011.htm#4.6.

- 4.Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood. A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist. 2000;55(5):469–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Association of Attorneys General. [Accessed 20 Aug, 2013];Project Tobacco: the Master Settlement. 2010 www.naag.org/backpages/naag/tobacco/msa/msa-pdf/MSAwithSigPagesandExhibits.pdf/file_view. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ling P, Glantz S. Why and how the tobacco industry sells cigarettes to young adults: Evidence from industry documents. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92(6):908–916. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.6.908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lechner WV, Meier E, Miller MB, Wiener JL, Fils-Aime Y. Changes in smoking prevalence, attitudes, and beliefs over 4 years following a campus-wide anti-tobacco intervention. Journal of American College Health. 2012;60(7):505–511. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2012.681816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seo D-C, Macy JT, Torabi MR, Middlestadt SE. The effect of a smoke-free campus policy on college students' smoking behaviors and attitudes. Preventive Medicine. 2011;53(4–5):347–352. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Procter-Scherdtel A, Collins D. Smoking restrictions on campus: changes and challenges at three Canadian universities, 1970–2010. Health and Social Care in the Community. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2012.01094.x. electronic publication ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Americans for Non-smokers' Rights. [Accessed 06 Aug, 2013];U.S. Colleges and universities with smoke free and tobacco-free policies. 2013 http://www.no-smoke.org/pdf/smokefreecollegesuniversities.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Plaspohl SS, Parrillo AV, Vogel R, Tedders S, Epstein A. An assessment of America's tobacco-free colleges and universities. Journal of American College Health. 2011;60(2):162–167. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2011.580030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mutnick A. Statewide bans boost smoke-free campus momentum. [Accessed 26 Aug, 2013];2013 http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2013/07/09/smoking-ban-college-campuses/2504093/. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yudof M. [directive from President to Mark Yudof on tobacco-free University of California campus policies] 09 Jan 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee J, Ramney L, Goldstein A. Cigarette butts near building entrances: what is the impact of smoke-free college campus policies? Tobacco Control. 2011 doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050152. electronic publication ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American College Health Association. ACHA Guidelines: Position statement on tobacco on college and university campuses. 2009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee JG, Goldstein AO, Klein EG, Ranney LM, Carver AM. Assessment of college and university campus tobacco-free policies in North Carolina. Journal of American College Health. 2012;60(7):512–519. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2012.690464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ostrom E. Understanding Institutional Diversity. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Basurto X, Kingsley G, McQueen K, Smith M, Weible CM. A systematic approach to institutional analysis: Applying Crawford and Ostrom's grammar. Political Research Quarterly. 2010;63(3):523–537. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crawford SES, Ostrom E. A grammar of institutions. The American Political Science Review. 1995;89(3):582–600. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Government Code Section 7596–7598 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wakefield M, Forster J. Growing evidence for new benefit of clean indoor air laws: reduced adolescent smoking. Tobacco Control. 2005 Oct 1;14(5):292–293. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.013557. 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lovato C, Linn G, Stead L, Best A. Impact of tobacco advertising and promotion on increasing adolescent smoking behaviours. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;4 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rigotti NA, Moran SE, Wechsler H. US college students' exposure to tobacco promotions: Prevalence and association with tobacco use. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95(1):138–144. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.026054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fennell R. Should colleges become tobacco-free without an enforcement plan? Journal of American College Health. 2012;60(7):491–494. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2012.716981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Siddiki S, Weible CM, Basurto X, Calanni J. Dissecting policy designs: An application of the Institutional Grammar Tool. The Policy Studies Journal. 2011;39(1):79–103. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baillie L, Callaghan D, Smith ML. Canadian campus smoking policies: Investigating the gap between intent and outcome from a student perspective. Journal of American College Health. 2011;59(4):260–265. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2010.502204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Russette HC, Harris KJ, Schuldberg D, Green L. Policy Compliance of Smokers on a Tobacco-Free University Campus. Journal of American College Health. 2014;62(2):110–116. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2013.854247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]