Abstract

Cardiomyocyte mitochondria have an intimate physical and functional relationship with sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR). Under normal conditions mitochondrial ATP is essential to power SR calcium cycling that drives phasic contraction/relaxation, and changes in SR calcium release are sensed by mitochondria and used to modulate oxidative phosphorylation according to metabolic need. When perturbed, mitochondrial-SR calcium crosstalk can evoke programmed cell death. Physical proximity and functional interplay between mitochondria and SR is maintained in part through tethering of these two organelles by the membrane protein mitofusin 2 (Mfn2). Here we review and discuss findings from our two laboratories that derive from genetic manipulation of Mfn2 and closely related Mfn1 in mouse hearts and other experimental systems. By comparing the findings of our two independent research efforts we arrive at several conclusions that appear to be strongly supported, and describe a few areas of incomplete understanding that will require further study. In so doing we hope to clarify some misconceptions regarding the many varied roles of Mfn2 as both physical trans-organelle tether and mitochondrial fusion protein.

Keywords: mitochondria, sarcoplasmic reticulum, calcium cross-talk, organelle tethering, mitochondrial fusion, mitochondrial permeability transition pore

INTRODUCTION

Calcium cycling and signaling are central to normal cardiac development, metabolic homeostasis and contraction. Perturbations in calcium import, release, or re-uptake cause or contribute to post-ischemic cardiac dysfunction, programmed cardiomyocyte death, and intrinsic contractile depression in heart failure [1]. Calcium influx through sarcolemmal membrane channels is the initiating event in excitation-contraction coupling, but free calcium that drives contraction and modulates cell signaling pathways is largely derived from intracellular stores [2]. The sarcoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria are the most important organelle mediators of intracellular calcium uptake, storage, and release in cardiomyocytes. Ultrastructurally, these two organelles appear to exist in intimate physical association. Whether this represents the coincidental co-distribution of two requisite organelles throughout the cardiomyocyte, or a purposeful structural relationship with functional implications for inter-organelle cross-regulation [3] cannot be determined from electron micrographs. Recent identification of the molecular nature of mitochondrial calcium import mechanisms [4–6] and the protein tethers that create protected calcium microdomains between mitochondria and SR [7] have helped to identify context-specific roles played by calcium cross-talk between these two organelles in healthy and diseased hearts. Here, we review recent developments that are revising prior concepts about the nature and extent of cardiac SR-mitochondrial cross-talk [8], focusing mainly on insights derived from in vivo cardiac-specific manipulation of the organelle tethering protein, mitofusin (Mfn) 2.

Mfn2 tethers ER/SR to mitochondria

The sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) is a modified smooth endoplasmic reticulum (ER) that passively releases calcium to promote muscle contraction, and then actively takes up calcium to promote relaxation [9]. Because SR and mitochondria are so closely apposed, and since mitochondria also take up and store calcium, one might reason that mitochondria would readily sense the cyclic changes in free cytosolic calcium evoked by SR calcium release and re-uptake. However, mitochondrial calcium uptake through the so-called calcium uniporter is remarkably inefficient, requiring a >10 µM concentration of free calcium for effect [3, 10], which is not normally achieved in cardiomyocyte sarcoplasm [5, 11], at least as measured by standard methods that average free calcium concentration cell-wide. Nevertheless, using sensitive techniques it is possible to detect phasic mitochondrial calcium transients that recapitulate, albeit at greatly depressed amplitude, SR calcium release and reuptake transients [12–14]. Hypothetically, a physical connection between SR and mitochondria could enhance mitochondrial delivery of SR-derived calcium by limiting cytosolic diffusion. This notion became the conceptual underpinning for protected SR/SE-mitochondrial calcium microdomains that have subsequently been directly verified by in loco measurements [3, 10].

Strong evidence for the dependence of ER/SR-mitochondrial calcium microdomains on physical trans-organelle linkage was provided by identification of the mitochondrial fusion protein Mfn2 as a molecular tether that links fibroblast ER and cardiomyocyte SR to mitochondria [7, 15]. Although Mfn2 plays a number of different roles in the heart [16, 17], this dynamin-family GTPase is most widely recognized for its ability to mediate (in most cells redundantly with closely related Mfn1) mitochondrial tethering and outer membrane fusion during regenerative mitochondrial fusion [18]. The biophysical mechanisms of Mfn-mediated mitochondrial membrane fusion have recently been reviewed in detail [19]. Actual membrane fusion is not, however, known to occur after Mfn2-mediated tethering of SR/ER to mitochondria, and is therefore not discussed further here except to note that both published and unpublished data derived from comparative in vivo cardiomyocyte-specific ablation of Mfn2 and Mfn1 suggest that Mfn1 is more important as a mediator of mitochondrial fusion. In this regard, Mfn1 and Mfn2 cardiac knockout mice developed in the Walsh laboratory revealed that deletion of Mfn2 increased mitochondrial size [20], whereas deletion of Mfn1 decreased mitochondrial size [21] in cardiomyocytes.

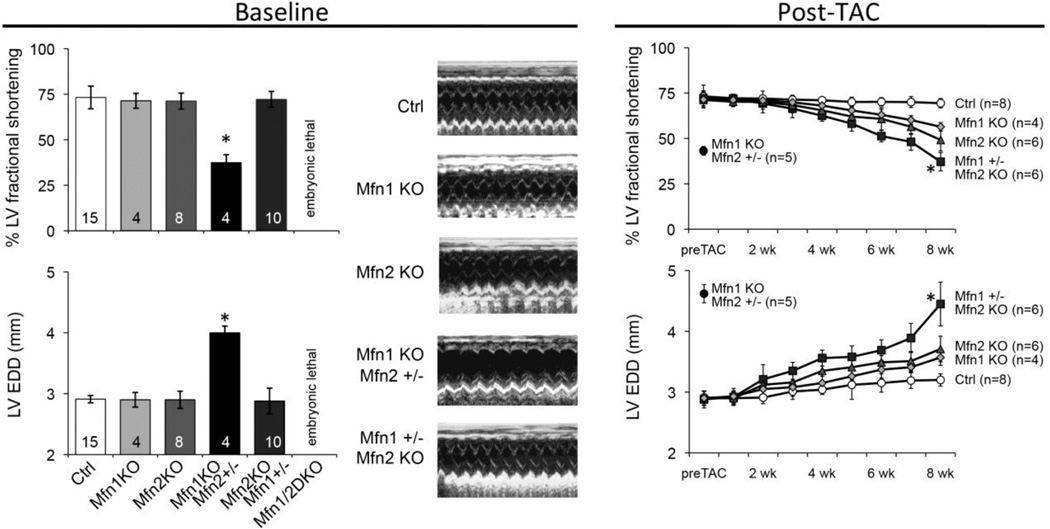

Additional evidence supporting a dominant role for Mfn1 in cardiomyocytes was derived from tri-allele Mfn1/Mfn2 cardiac knockout mice (embryonic deletion with Nkx2.5-Cre) developed in the Dorn laboratory. In previously unpublished work we found that complete embryonic cardiac ablation of either Mfn1 or Mfn2 has no effect on baseline cardiac function and only modestly impairs the adaptive response to experimental pressure overload evoked by partial surgical ligation of the transverse aorta (TAC) (Figure 1). Likewise total cardiac knockout of Mfn2 and one Mfn1 allele (leaving one Mfn1 allele intact) was compatible with normal viability and baseline cardiac function, although the adaptive response to TAC was impaired (Figure 1). Strikingly however, total cardiac knockout of Mfn1 and one Mfn2 allele, leaving only one functional Mfn2 allele, evoked a severe cardiomyopathy at baseline that is similar to that observed after conditional ablation of both Mfn1 and Mfn2 [22, 23]. Furthermore, these mice did not tolerate TAC (Figure 1). Thus, multiple independent studies suggest that Mfn1 appears is more important than Mfn2 as a mitochondrial fusion factor, both for maintaining cardiac basal homeostasis and in the reaction to hemodynamic stress.

Figure 1. Preeminence of Mfn1 over Mfn2 for cardiac function.

A. Baseline echocardiographic characteristics of 8 week old mice with embryonic heart specific (Nkx2.5-Cre mediated) deletion of Mfn1 and Mfn2 genes in various allelic combinations. Ctrl is Mfn1+/+, Mfn2 +/+; Mfn1 KO is Mfn1−/−, Mfn2 +/+; Mfn2 KO is Mfn1 +/+, Mfn2 −/−; Mfn2 hapl (haploinsufficient) is Mfn1−/−, Mfn2 +/−; Mfn1 hapl is Mfn1+/−, Mfn2 −/−. Mfn1/Mfn2 double cardiac KO is embryonic lethal [15]. A single Mfn1 allele and no Mfn2 expression is sufficient for normal basal cardiac function, whereas mice with a single cardiac Mfn2 allele and no Mfn1 expression develop a spontaneous cardiomyopathy. B. Different responses of cardiac Mfn1 KO, cardiac Mfn2 KO, and cardiac Mfn1 hapl to pressure overload modeling. Time course of cardiac ejection performance and left ventricular remodeling after TAC with ~60 mm Hg transaortic gradient. Absence of either Mfn1 or Mfn2 modestly compromises the late compensatory response, whereas mice having only a single Mfn1 allele show significantly greater decompensation. * = P<0.05 from other groups by ANOVA.

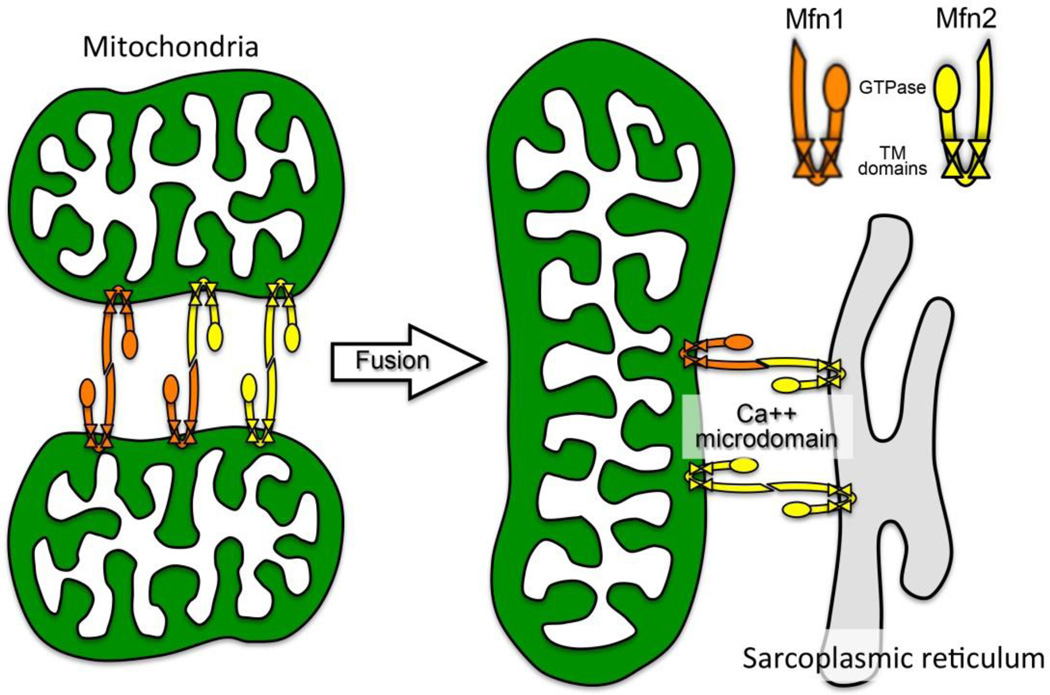

Mitofusin-mediated attachments between mitochondria or mitochondria and SR/ER are determined by the physical structure of the molecular tether. Mitofusins consist of a globular N-terminal GTPase domain, an alpha helical first heptad repeat (HR1), two neighboring lipophilic transmembrane domains, and a more C-terminal second alpha helical heptad repeat (HR2). The N- and C-termini are cytosolic, and the twin transmembrane domains create a hairpin curve through the outer mitochondrial membrane [24]. Thus, HR1 and HR2 each exist on one cytosolic arm of the tightly folded mitofusin molecule (Figure 2). This configuration is important for mitochondrial tethering, which occurs via anti-parallel binding between the HR2 domains of two different mitofusin molecules interacting in trans (because they are embedded in the outer membranes of two different mitochondria) (Figure 2). Mfn2-Mfn2 (or Mfn1–Mfn2) tethering is strictly a physical interaction that does not require GTPase activity. Because a small fraction (~10%) of Mfn2 localizes to ER/SR membranes (also facing the cytosol), Mfn2 is also the molecular tether between ER/SR and mitochondria, (Figure 2), dimerizing in trans with either mitochondrial Mfn1 or Mfn2. For this reason, cardiac Mfn2 is posited to play a role in SR-mitochondrial calcium cross-talk and to be one of the factors that regulate events orchestrated by mitochondrial calcium uptake, such as metabolism, opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (MPTP), and programmed cardiomyocyte death.

Figure 2. Schematic depiction of Mfn2 tethering function for mitochondrial fusion and mitochondria-SR calcium crosstalk.

Mfn1 (orange) and Mfn2 (yellow) are depicted as they mediate inter-mitochondria tethering (left) and fusion (middle), and mitochondria-SR tethering (right). Note that either Mfn can bind in trans to the other, conferring functional overlap for mitochondrial fusion. But since Mfn2 exclusively localizes to SR, it is essential for creating privileged mitochondria-SR calcium microdomains that mediate metabolic signaling and opening of MPTP.

In vivo consequences of cardiomyocyte-specific Mfn2 gene deletion

To learn about the in vivo effects of Mfn2 in the heart our two laboratories independently, and without prior knowledge of the others’ intent, generated cardiac-specific Mfn2 knockout mice. Although there will always be differences in approach and technique, the opportunity to gain fresh insights with a high degree of confidence is greatly enhanced when similar experiments are performed concomitantly by different research groups, and the results can be compared. Here, our two groups used the same floxed Mfn2 allele parent line generated by David Chan [25], but we crossed it onto two different versions of a myh6-Cre transgene. The Walsh lab used myh6-Cre developed and characterized by Michael Schneider, which is cardiac-specific and initiates recombination of floxed gene alleles in the embryonic heart [26]. The Dorn lab used the myh6-driven so-called “turbo-Cre” developed by Molkentin and Robbins, which promotes cardiac-specific gene recombination only after birth [15]. Because the turbo-Cre protein is targeted to the nucleus, it may also have less propensity for Cre-mediated cardiac toxicity [27]. The major mitochondrial and cardiac phenotypes of our two cardiac Mfn2 knockout mice are similar, but there are some interesting differences that may relate to differences in the timing of Mfn2 deletion or other, less definable factors. The phenotypic distinctions and differences in experimental design have led to some confusion among those interested in this area. For this reason, below we compare and contrast our findings, drawing conclusions from the cumulative data and offering explanations (when we can) for apparent disparate observations.

Papanicolaou et al. from the Walsh laboratory were the first to describe the consequences of cardiac Mfn2 ablation [20]. Table 1 summarizes the major findings evoked by Mfn2 deficiency in young adult mice (age 10–14 weeks): Hearts showed modest cardiac hypertrophy accompanied by contractile depression observed only after stimulation with isoproterenol. Mitochondrial size was increased, mitochondrial polarization status was impaired, and calcium-induced mitochondrial swelling was diminished by ~25%, pointing to a constellation of physical and functional mitochondrial abnormalities in hearts lacking Mfn2. Because Mfn2 was hypothesized to tether mitochondria to ER/SR [7], the distance between these two organelles was assessed using transmission electron microscopy, but was not found to vary significantly from normal.

Table.

Comparison of characteristics of Walsh lab and Dorn lab cardiac Mfn2 knockout mouse findings.

| Walsh lab Mfn2 null1 | Dorn lab Mfn2 null2,3,4,5 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Adult (10–14 wks) | Juvenile (6 wks)2 | Mature (16–44 wks) | |

| Cardiac Phenotype | |||

| Mfn2 protein level | ↓90% | ↓80% | ↓80%3 |

| Ht weight/body wt | ↑20% | Nl | ↑35%4 |

| LV %FS | Nl | Nl | ↓30–50%3 |

| +dP/dtmax resting | Nl | Nl | ↓50%3 |

| +dP/dtmax peak | ↓33% (isoproterenol) | Nl | ↓70% (dobutamine)3 |

| Mitochondrial Phenotype | |||

| Mitochondrial size | ↑2-fold (TEM) | ↑50% (TEM) | ↑30% (flow cyto)4 |

| Respiration | Nl | Nl | ↓25%4 |

| Δψm | ↓30% | Nl | ↓25%4 |

| ROS production | n.d. | Nl | ↑3-fold4 |

| Ca2++ induced swelling | ↓25% | Nl | Nl4 |

| SR-mito tethering | Nl (mito-SR distance) | ↓30% (mito-SR contact length) | n.d. |

| Gene expression | |||

| ANP | ↑3-fold | ↑3-fold5 | ↑4-fold5 |

| BNP | ↑20% | ↑2-fold5 | ↑4-fold5 |

| Tfam | ↓30% | Nl5 | ↑2-fold5 |

| PGC1α | ↓25% | Nl5 | Nl5 |

| cytb | ↓15% | Nl5 | Nl5 |

| ndf | ↓25% | Nl5 | Nl5 |

Papanicolaou KN et al. Mol Cell Biol 31:1309–28, 2011

Chen Y et al. Circ Res 111:863–75, 2012

Chen Y and Dorn GW II Science 340:471–475, 2013

Song M et al. Circ Res 115:348–353, 2014

Chen Y et al. Antioxid Redox Signal 2014, in press (online)

The major phenotypes accruing from cardiac-specific Mfn2 ablation in the Dorn laboratory are fairly similar (Table 1) when one accounts for differences in age of the mice and in techniques used to measure several of the endpoints. Thus, cardiac hypertrophy and contractile depression were observed in older mice (most of these data are from 16 or 30 week old mice, with a few examples followed up to 44 weeks), but not in mice of only 6 weeks of age. Mitochondrial size was increased, measured either by transmission electron microscopy in younger mice or by forward light scattering in flow cytometric studies of isolated cardiac mitochondria in older mice. Likewise, Mfn2 null cardiac mitochondria from older mice exhibited partial dissipation of Δωm, i.e. depolarization, and increased ROS formation. Thus, independent generation of cardiac-specific Mfn2 knockout mouse models by our two laboratories evoked mitochondrial enlargement (a seemingly paradoxical response as mitofusins promote fusion and their deletion is therefore expected to shift the balance toward fission) accompanied by cardiac hypertrophy and contractile depression that appears progressive. The changes in mitochondrial structure may be secondary to the cardiomyopathy caused by alterations in mitochondrial function, as reflected by loss of mitochondrial inner membrane potential Δωm and increased ROS production. Alternatively, it has been suggested that differences in mitochondrial size in the Mfn1 and Mnn2 null mice (smaller and larger than wild type, respectively) are due to differences in the inherent GTPase activities of these two molecules [5]. Mfn2, with the lower GTPase activity, would serve to retard the fusion activity of Mfn1 in a heterotypic complex. Thus, Mfn2-deficiency would thereby lead to mitochondrial enlargement. Other studies have proposed that a major mechanism contributing to the accumulation of abnormal mitochondria in Mfn2 null hearts (and brains and livers) [28, 29] is interruption of normal Parkin-mediated mitochondrial culling, in which Mfn2 plays a central role (recently reviewed in detail [30]).

As with any experiment performed by different groups there are also intriguing differences in results. In the case of our respective cardiac Mfn2 null mouse studies, the differences relate almost entirely to outcomes that one would predict are driven by Mfn2 functioning as a putative putative SR-mitochondrial molecular tether. First and foremost is the evidence that removal of Mfn2 from cardiomyocytes alters the physical relationship between cardiac SR and mitochondria. Papanicolaou et al. in the Walsh lab carefully measured the distance between the center of the T-tubule and the mitochondrial surface on TEMs, and found that absence of Mfn2 did not affect this metric [20]. On the other hand, using a different metric of SR-mitochondrial tethering, the mean contact length between mitochondria and junctional SR, Gyorgi Csordas et al. observed a ~30% reduction in Mfn2 null, but not Mfn1 null, hearts in the Dorn lab versions of these mice [15]. Given compelling physical evidence for abnormalities in SR calcium handling induced by Mfn2 ablation in both labs’ cardiac deficient mouse lines (see below), we conclude that Mfn2 does likely contribute to the physical organization of, and functional interaction between, cardiomyocyte mitochondria and adjacent SR.

Mfn2 deletion and SR-mitochondrial calcium cross-talk

Functional evidence that Mfn2 facilitates calcium cross-talk between cardiomyocyte SR and mitochondria is strong and comes in different experimental forms from our two labs. The first such evidence was indirect, and derives from the observation that ablation of mouse Mfn2 or Drosophila MARF (the fruit fly mitofusin ortholog) increases SR calcium content in both isolated mouse cardiomyocytes and fly heart tubes [15]; selective cardiac ablation of mouse Mfn1 under the exact same conditions as Mfn2 did not affect SR calcium content [15]. Given that Mfn2 (and not Mfn1) tethers ER/SR to mitochondria [7], and that mitochondrial import of SR-derived calcium is contingent upon the proper physical spacing between these two organelles at ER-mitochondrial contact sites [3, 31], loosening of the physical contacts between these two organelles when the Mfn2 tether is removed would be expected to decrease mitochondrial uptake of calcium released from SR. In short, mitochondria that are physically and functionally linked to SR calcium release can act as calcium sponges. Mfn2 ablation distorts the normal physical coupling of SR and their neighboring calcium sponges by removing the tethers. Under these conditions, calcium that would normally be imported into mitochondria is not, and is therefore taken back up by the SR. Consequently, over time total SR calcium stores increase.

The second line of evidence that Mfn2 facilitates calcium cross-talk between cardiomyocyte SR and mitochondria derives from directly measuring mitochondrial calcium levels in isolated Mfn2 null cardiac myocytes as a function of modulated SR calcium release. These studies were performed by Christoph Maack using the Dorn lab cardiac-specific Mfn2 (and Mfn1) null mice [15]. Briefly, mitochondrial calcium transients were measured in isolated myocytes stimulated first with isoproterenol and then by increasing the pacing frequency 10-fold. This is essentially a stress test for the cardiomyocyte, increasing both the force (isoproterenol) and rate (pacing) of contraction, which of course is driven by increases in cyclic SR calcium release and re-uptake. Under normal conditions, increased SR calcium cycling is mirrored by the mitochondria, which act as an integrator of the phasic cytosolic calcium transients [32]. Increased mitochondrial calcium activates Krebs cycle enzymes, increases the rate of NAD(P)H regeneration from NAD(P)+, and accelerates respiration. This anticipatory calcium-stimulated increase in respiratory ATP production is essential to prophylaxing a metabolic deficit under conditions of acutely increased cardiac demand. This entire process in dysfunctional in Mfn2 deficient cardiomyocytes: Mitochondrial sensing of SR-derived calcium is depressed, the stress-test induced increase in mitochondrial calcium is delayed, NAD(P)H levels fall, and reactive oxygen species are transiently produced [15]. By contrast, these responses are completely normal in Mfn1 null cardiomyocytes.

The third line of evidence supporting modulation of SR-calcium signaling by Mfn2 is protection against ischemia-reperfusion injury described by the Walsh lab for their Mfn2 cardiac null mice [20]. In isolated hearts challenged by 10 minutes of global ischemia followed by 20 minutes of reperfusion, both peak left ventricular systolic pressure and left ventricular developed pressure were markedly better in cardiac Mfn2 null hearts, compared to Mfn2 floxed controls. Likewise myocytes isolated from cardiac Mfn2 null hearts were somewhat resistant to outer membrane permeabilization (trypan blue staining) induced by in vitro hypoxia (1 hour) followed by 2 hours of reoxygenation; even more striking protection against hydrogen peroxide-induced cardiomyocyte injury was afforded by Mfn2 ablation. Finally cardiac Mfn2 null hearts exhibited ~20% smaller myocardial infarct sizes when reperfused for 2 hours after a 30 minute transient ischemic insult, and cardiomyocyte TUNEL positivity was similarly decreased [20].

Finally, the Walsh lab observed that the ER-stress response is associated with selective upregulation of Mfn2, and found that genetic deletion of Mfn2 (but not Mfn1) in either cardiac myocytes or embryonic fibroblasts increased ER chaperone proteins, amplified ER stress, and exaggerated the apoptotic response to ER stress [33]. It has also been noted that ER stress is modulated by Mfn2 in hepatocytes, PDMC neurons and in Drosophila tissues [29, 34, 35]. While one cannot exclude other possibilities, the aggregate data from both of our cardiac Mfn2 null mouse models supports an important function for Mfn2 (but not Mfn1) in maintaining proper inter-organelle architecture and a normal spatial relationship between cardiac SR and interfibrillar mitochondria. Furthermore, it is reasonable to speculate that the consequences of SR-mitochondrial calcium signaling differ upon pathophysiological context: Under normal conditions, calcium microdomains created in part by Mfn2 SR-mitochondrial tethering facilitate mitochondrial sensing of increased SR calcium release directed at increasing cardiac contractility, thereby preventing metabolic deficits during periods of acute hemodynamic demand. During ischemiareperfusion injury however, Mfn2 tethering of mitochondria to SR could augment calcium delivery to MPTP, thereby increasing MPTP-mediated cell death.

Mfn2 gene deletion and the MPTP

Although the studies performed by our two laboratories on our respective cardiac Mfn2 null mouse lines have largely agreed as to the consequences of Mfn2 deletion on mitochondrial size and function, on SR-mitochondrial calcium signaling, and on the heart abnormalities that occur at baseline, our findings differ as to the effects of Mfn2 ablation on the intrinsic sensitivity of the MPTP.

The MPTP is a protein pore of unknown composition that, when opened, freely permits diffusion of small molecules (<1500 Daltons) across the mitochondrial inner and outer membranes. MPTP opening is stimulated by calcium, positively regulated by cyclophilin-D, and causes mitochondrial swelling by permitting the unrestricted osmotic inflow of water [36, 37]. Because MPTP is stimulated by calcium it is potentially modifiable by Mfn2 deletion, either because absence of Mfn2 directly alters the intrinsic sensitivity of MPTP to calcium, or because absence of Mfn2 decreases SR calcium delivery to mitochondria. There is agreement that factors, drugs, or conditions that increase calcium delivery from SR to mitochondria (such as Mfn2) can increase MPTP opening, thereby predisposing the cell to death by “programmed necrosis”. Chen et al. [38] provided evidence for this paradigm in vitro and in vivo in the heart by targeting the BH3 only Bcl2 family protein Nix either to mitochondria, where it did not affect SR calcium cycling and provoked pure apoptosis, or to SR, where it increased SR calcium content and induced programmed necrosis. The latter, but not the former, was rescued by MPTP inhibition through cyclophilin D gene ablation. Because Mfn2 can also increase SR calcium stores and enhance SR-to-mitochondria delivery of calcium, it would be predicted to also facilitate MPTP opening; conversely, Mfn2 ablation should suppress the ability of SR-derived calcium to open the MPTP. Papanicolaou et al’s observation that Mfn2 null mouse hearts are resistant to ischemic injury seems consistent with this overall paradigm. However, using the standard mitochondrial swelling assay the Walsh lab reported that mitochondria from either Mfn1- or Mfn2-null mice display a decrease in intrinsic sensitivity of the MPTP to calcium [20, 21], whereas the same assay performed using nearly identical techniques by multiple personnel on mitochondria of either young or mature Mfn2 cardiac null mice from the Dorn lab shows normal calcium swelling [15, 39] (Table 1). However, based upon various in vitro and in vivo assays [20, 21], the Walsh laboratory proposed that Mfn1 and Mfn2 can contribute to membrane depolarization through their abilities to promote lipidic pore formation adjacent to hemifusin structures, obligate intermediate structures that make membrane fusion (or fission) thermodynamically favorable [19]. Similar structures have been proposed for Drp-1 and fission, where Bax may participate in the fission process via its ability to stabilize lipidic pores [40, 41]. As we do not have a clear explanation for these differences at this time, we suggest that the conservative interpretation of the aggregate data is that Mfn2 tethering of SR to mitochondria increases MPTP opening by enhancing the efficiency by which the SR can deliver calcium to mitochondria via protected microdomains, and that both Mfn1 and Mfn2 can also regulate MPTP function by altering its stability or the structure of its outer membrane components during the fusion process. Further investigation will be required to distinguish between these possibilities.

Summary

Mitochondrial research in the cardiac arena is experiencing a literal re-awakening as we increasingly appreciate how these organelles impact normal, stressed, and damaged hearts in ways that are completely separate from their canonical role in cell metabolism. The potential for mitochondria to transform from essential generators of ATP to pathological sources of ROS is ever-present, and the physical and functional interplay between mitochondria and SR is increasingly recognized as a major factor that orchestrates normal homeostasis and, when perturbed, mediates disease. Because mitochondria in adult mammalian cardiomyocytes are more abundant but less dynamic that mitochondria of any other cell type, functional interrogation of various mitochondrial dynamics factors using conventional in vivo genetic manipulation has produced unexpected dividends in the form of fresh insights into atypical functions of mitochondrial fusion proteins as tethering factors that facilitate inter-organelle cross-talk, with consequences on cardiomyocyte differentiation, metabolism, and programmed death. We anticipate further advances based on these, and future, experimental models. We also suggest that whole genome and exome sequencing of human cardiomyopathies may uncover functional mutations of Mfn2 and related factors that, by interfering with normal mitochondrial-SR connectivity, can modify risk of developing clinical cardiac disease.

Highlights.

Mitochondrial fusion proteins, mitofusins, are abundant in mammalian hearts.

Cardiomyocyte mitochondria do not exhibit a fused morphology.

Mitofusin (Mfn) 2 has secondary functions, including mitochondrial-SR tethering.

Mfn2-mediated mitochondrial-SR tethering facilitates calcium cross-talk.

Thus, Mfn2 modulates mitochondrial metabolism and MPTP opening.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Supported by NIH grants HL59888 and HL120160, and a fellowship award from the American Heart Association.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Houser SR, Piacentino V, 3rd, Weisser J. Abnormalities of calcium cycling in the hypertrophied and failing heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2000;32:1595–1607. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bers DM. Calcium cycling and signaling in cardiac myocytes. Annu Rev Physiol. 2008;70:23–49. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.70.113006.100455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Csordas G, Varnai P, Golenar T, Roy S, Purkins G, Schneider TG, et al. Imaging interorganelle contacts and local calcium dynamics at the ER-mitochondrial interface. Mol Cell. 2010;39:121–132. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Stefani D, Raffaello A, Teardo E, Szabo I, Rizzuto R. A forty-kilodalton protein of the inner membrane is the mitochondrial calcium uniporter. Nature. 2011;476:336–340. doi: 10.1038/nature10230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams GS, Boyman L, Chikando AC, Khairallah RJ, Lederer WJ. Mitochondrial calcium uptake. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:10479–10486. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1300410110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pendin D, Greotti E, Pozzan T. The elusive importance of being a mitochondrial Ca(2+) uniporter. Cell Calcium. 2014;55:139–145. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2014.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Brito OM, Scorrano L. Mitofusin 2 tethers endoplasmic reticulum to mitochondria. Nature. 2008;456:605–610. doi: 10.1038/nature07534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dorn GW, 2nd, Scorrano L. Two close, too close: sarcoplasmic reticulum-mitochondrial crosstalk and cardiomyocyte fate. Circ Res. 2010;107:689–699. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.225714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Golovina VA, Blaustein MP. Spatially and functionally distinct Ca2+ stores in sarcoplasmic and endoplasmic reticulum. Science. 1997;275:1643–1648. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5306.1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giacomello M, Drago I, Bortolozzi M, Scorzeto M, Gianelle A, Pizzo P, et al. Ca2+ hot spots on the mitochondrial surface are generated by Ca2+ mobilization from stores, but not by activation of storeoperated Ca2+ channels. Mol Cell. 2010;38:280–290. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kirichok Y, Krapivinsky G, Clapham DE. The mitochondrial calcium uniporter is a highly selective ion channel. Nature. 2004;427:360–364. doi: 10.1038/nature02246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rizzuto R, Simpson AW, Brini M, Pozzan T. Rapid changes of mitochondrial Ca2+ revealed by specifically targeted recombinant aequorin. Nature. 1992;358:325–327. doi: 10.1038/358325a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou Z, Matlib MA, Bers DM. Cytosolic and mitochondrial Ca2+ signals in patch clamped mammalian ventricular myocytes. J Physiol. 1998;507(Pt 2):379–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.379bt.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maack C, Cortassa S, Aon MA, Ganesan AN, Liu T, O'Rourke B. Elevated cytosolic Na+ decreases mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake during excitation-contraction coupling and impairs energetic adaptation in cardiac myocytes. Circ Res. 2006;99:172–182. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000232546.92777.05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen Y, Csordas G, Jowdy C, Schneider TG, Csordas N, Wang W, et al. Mitofusin 2-containing mitochondrial-reticular microdomains direct rapid cardiomyocyte bioenergetic responses via interorganelle Ca(2+) crosstalk. Circ Res. 2012;111:863–875. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.266585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen Y, Dorn GW., 2nd PINK1-phosphorylated mitofusin 2 is a Parkin receptor for culling damaged mitochondria. Science. 2013;340:471–475. doi: 10.1126/science.1231031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kasahara A, Cipolat S, Chen Y, Dorn GW, 2nd, Scorrano L. Mitochondrial fusion directs cardiomyocyte differentiation via calcineurin and Notch signaling. Science. 2013;342:734–737. doi: 10.1126/science.1241359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Griffin EE, Detmer SA, Chan DC. Molecular mechanism of mitochondrial membrane fusion. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1763:482–489. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Papanicolaou KN, Phillippo MM, Walsh K. Mitofusins and the mitochondrial permeability transition: the potential downside of mitochondrial fusion. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;303:H243–H255. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00185.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Papanicolaou KN, Khairallah RJ, Ngoh GA, Chikando A, Luptak I, O'Shea KM, et al. Mitofusin-2 maintains mitochondrial structure and contributes to stress-induced permeability transition in cardiac myocytes. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:1309–1328. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00911-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Papanicolaou KN, Ngoh GA, Dabkowski ER, O'Connell KA, Ribeiro RF, Jr, Stanley WC, et al. Cardiomyocyte deletion of mitofusin-1 leads to mitochondrial fragmentation and improves tolerance to ROS-induced mitochondrial dysfunction and cell death. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;302:H167–H179. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00833.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen Y, Liu Y, Dorn GW., 2nd Mitochondrial fusion is essential for organelle function and cardiac homeostasis. Circ Res. 2011;109:1327–1331. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.258723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Papanicolaou KN, Kikuchi R, Ngoh GA, Coughlan KA, Dominguez I, Stanley WC, et al. Mitofusins 1 and 2 are essential for postnatal metabolic remodeling in heart. Circ Res. 2012;111:1012–1026. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.274142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koshiba T, Detmer SA, Kaiser JT, Chen H, McCaffery JM, Chan DC. Structural basis of mitochondrial tethering by mitofusin complexes. Science. 2004;305:858–862. doi: 10.1126/science.1099793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen H, McCaffery JM, Chan DC. Mitochondrial fusion protects against neurodegeneration in the cerebellum. Cell. 2007;130:548–562. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gaussin V, Van de Putte T, Mishina Y, Hanks MC, Zwijsen A, Huylebroeck D, et al. Endocardial cushion and myocardial defects after cardiac myocyte-specific conditional deletion of the bone morphogenetic protein receptor ALK3. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:2878–2883. doi: 10.1073/pnas.042390499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Molkentin JD, Robbins J. With great power comes great responsibility: using mouse genetics to study cardiac hypertrophy and failure. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2009;46:130–136. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee S, Sterky FH, Mourier A, Terzioglu M, Cullheim S, Olson L, et al. Mitofusin 2 is necessary for striatal axonal projections of midbrain dopamine neurons. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:4827–4835. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sebastian D, Hernandez-Alvarez MI, Segales J, Sorianello E, Munoz JP, Sala D, et al. Mitofusin 2 (Mfn2) links mitochondrial and endoplasmic reticulum function with insulin signaling and is essential for normal glucose homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:5523–5528. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108220109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dorn GW, 2nd, Kitsis RN. The mitochondrial dynamism-mitophagy-cell-death interactome: multiple roles performed by members of a mitochondrial molecular ensemble. Circ Res. 2014 doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.303554. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eisner V, Csordas G, Hajnoczky G. Interactions between sarco-endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria in cardiac and skeletal muscle - pivotal roles in Ca(2)(+) and reactive oxygen species signaling. J Cell Sci. 2013;126:2965–2978. doi: 10.1242/jcs.093609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lu X, Ginsburg KS, Kettlewell S, Bossuyt J, Smith GL, Bers DM. Measuring local gradients of intramitochondrial [Ca(2+)] in cardiac myocytes during sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca(2+) release. Circ Res. 2013;112:424–431. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.300501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ngoh GA, Papanicolaou KN, Walsh K. Loss of mitofusin 2 promotes endoplasmic reticulum stress. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:20321–20332. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.359174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schneeberger M, Dietrich MO, Sebastian D, Imbernon M, Castano C, Garcia A, et al. Mitofusin 2 in POMC neurons connects ER stress with leptin resistance and energy imbalance. Cell. 2013;155:172–187. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Debattisti V, Pendin D, Ziviani E, Daga A, Scorrano L. Reduction of endoplasmic reticulum stress attenuates the defects caused by Drosophila mitofusin depletion. J Cell Biol. 2014;204:303–312. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201306121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haworth RA, Hunter DR. The Ca2+-induced membrane transition in mitochondria. II. Nature of the Ca2+ trigger site. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1979;195:460–467. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(79)90372-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baines CP, Kaiser RA, Purcell NH, Blair NS, Osinska H, Hambleton MA, et al. Loss of cyclophilin D reveals a critical role for mitochondrial permeability transition in cell death. Nature. 2005;434:658–662. doi: 10.1038/nature03434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen Y, Lewis W, Diwan A, Cheng EH, Matkovich SJ, Dorn GW., 2nd Dual autonomous mitochondrial cell death pathways are activated by Nix/BNip3L and induce cardiomyopathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:9035–9042. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914013107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Song M, Chen Y, Gong G, Murphy E, Rabinovitch PS, Dorn GW., 2nd Super-suppression of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species signaling impairs compensatory autophagy in primary mitophagic cardiomyopathy. Circ Res. 2014;115:348–353. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.304384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Martinou JC, Youle RJ. Mitochondria in apoptosis: Bcl-2 family members and mitochondrial dynamics. Dev Cell. 2011;21:92–101. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Montessuit S, Somasekharan SP, Terrones O, Lucken-Ardjomande S, Herzig S, Schwarzenbacher R, et al. Membrane remodeling induced by the dynamin-related protein Drp1 stimulates Bax oligomerization. Cell. 2010;142:889–901. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]