Abstract

The outcomes of Helicobacter pylori infection vary geographically. H. pylori strains, disease presentation, and environments differ markedly in Bhutan and Dominican Republic. The aims were to compare the strains, histology and expression of interleukin (IL)-8 and IL-10 from gastric mucosa from the two countries. H. pylori status was assessed by the combination of rapid urease test, culture and histology. Histology was evaluated using the updated Sydney System and cytokines in gastric biopsies were measured using real-time PCR. There were 138 subjects from Bhutan and 155 from Dominican Republic. The prevalence of H. pylori infection was 65% and 59%, respectively. The genotype of cagA was predominantly East-Asian type in Bhutan vs. Western type in Dominican Republic. Gastritis severity was significantly higher in H. pylori-infected subjects from Bhutan than those from Dominican Republic. IL-8 expression by H. pylori-infection was 5.5-fold increase in Bhutan vs. 3-fold in Dominican Republic (p <0.001); IL-10 expression was similar. IL-8 expression levels among H. pylori-infected cases tended to be positively correlated with polymorphonuclear leucocyte (PMN) and monocyte infiltration (MNC) scores in both countries. IL-8 expression among those with grade 2 and 3 PMN and MNC was significantly higher in Bhutan than in Dominican Republic. The difference in IL-8 expression in two countries is reflected in the different disease pattern between them. Whether the dominant factor is differences in H. pylori virulence, in host-H. pylori-environmental interactions, genetic factors or all remains unclear. However, severity of inflammation appears to be a critical factor in disease pathogenesis.

We compared IL-8 mRNA levels between high gastric cancer risk country; Bhutan (mainly East Asian type H. pylori) and lower gastric cancer risk country; Dominican Republic (mainly Western type H. pylori).

Keywords: Helicobacter pylori, IL-8, cagA genotype, Bhutan, Dominican Republic

1. Introduction

Helicobacter pylori is a spiral, gram-negative human pathogen and a major cause of peptic ulcer disease and gastric cancer [1, 2]. H. pylori gastritis is characterized by infiltration of the gastric mucosa with both neutrophils and mononuclear cells and is associated with the upregulation of proinflammatory cytokines such as the potent chemotactic peptide interleukin (IL)-8 [2, 3]. The clinical manifestations of H. pylori infections vary both within and among populations; for example, in some areas such as Japan, where H. pylori infection is common, gastric cancer is an important clinical problem, whereas, in other areas such as South India, gastric cancer is rare and instead duodenal ulcer is a more common disease manifestation [4]. Whether these geographic differences correlate with the differences in the gastric mucosal cytokine levels remain unknown, because studies comparing the mucosal cytokine levels among individuals from different countries are lacking. Here, we have reported a comparison of gastric mucosal IL-8 and IL-10 expression and the histological findings by using gastric biopsies obtained from adults in Bhutan and the Dominican Republic. These countries were selected for the study because of the differences in their clinical outcomes of H. pylori infection as well as in their cagA genotype of the pathogenic H. pylori (i.e., cagA-negative, Western-type cagA in the Dominican Republic and East-Asian-type cagA in Bhutan). The tissue samples from both the regions were similarly processed and analyzed.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Countries

Bhutan and the Dominican Republic are relatively isolated developing countries where H. pylori infection is common. These countries show several differences in the age-standardized rate of gastric cancer incidence; the rate is higher in Bhutan (17.2/100,000) than in the Dominican Republic (7.3/100,000) (GLOBOCAN 2012: http://globocan.iarc.fr/). Bhutan is a small, landlocked mountainous country located at the eastern end of the Himalayas, and it shares borders on the south, east, and west with the Republic of India and to the north with the People’s Republic of China. In contrast, the Dominican Republic is a Caribbean island it shares borders on the east with Haiti, and with a population of 73% multiracial, 16% Caucasians, and 11% Congoid. We hypothesized that the cagA genotype between these two countries also differs, with Bhutanese strains being East-Asian-type cagA and the Dominican Republic strains being Western-type-cagA. In addition, the presence of cagA-negative strains makes these regions ideal for comparing the gastric histology and mucosal cytokine levels in relation to the cagA genotype and its outcome.

2.2. Subjects

We recruited individuals with mild dyspeptic symptoms living in Bhutan and outpatients with mild dyspeptic symptoms living in the Dominican Republic. The surveys took place at the Jigme Dorji Wangchuk National Referral Hospital, Thimpu, Bhutan in December 2010 and at the Dr. Luís E. Aybar Health and Hygiene City (Digestive Disease Center), Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic in February 2012. Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants. The protocol was approved by the ethics committee of Oita University Faculty of Medicine (Japan), Universidad Autonoma de Santo Domingo (Dominican Republic), and by both the hospitals where sample collection was performed.

The tissue sampling procedures as well as the method of sample handling were identical at both the locations. During each endoscopy session, 4 gastric biopsy specimens were obtained from the antrum: one each for H. pylori culturing, rapid urease test (CLO test, Campylobacter-like organism test, Kimberly-Clark Ballard Medical Products, Roswell, GA, USA), histological examination, and cytokine examination. Rapid urease test were performed at time of endoscopy. The clinical diagnoses after endoscopy included those for gastritis, duodenal ulcer, gastric ulcer, and gastric cancer. Peptic ulcer and gastric cancer were identified by endoscopy, and gastric cancer was confirmed by histopathology. Gastritis was defined as H. pylori gastritis in the absence of peptic ulcer or gastric malignancy. Patients with a history of partial gastric resection were excluded. Patients who had received H. pylori-eradication therapy or had received treatment with antibiotics, bismuth-containing compounds, H2-receptor blockers, or proton-pump inhibitors within 4 weeks prior to the study were also excluded.

All the biopsy specimens for culturing and RNA analyses were immediately placed on ice bath after collection and then stored in a −20°C freezer. The samples were kept frozen and dispatched on dry ice to the Oita University Faculty of Medicine, Japan via Express Mail within a week after collection. The samples received by the Oita University Faculty of Medicine were stored at −80°C until use. The biopsy specimens for histology were fixed in buffered formalin at room temperature and dispatched to the Oita University Faculty of Medicine for sectioning and analysis.

The presence of H. pylori was determined by using a combination of a rapid urease test, culture, serology, and histology as described by a previous study [5, 6]. Patients were considered to be H. pylori-negative when all the tests were negative. H. pylori-positive status required at least one positive test result.

2.3. H. pylori culture and cagA genotype

Antral biopsy specimens were obtained for the isolation of H. pylori by standard culturing technique as previously described [7]. H. pylori DNA was extracted from confluent plate cultures xpanded from a single colony by using DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit® (Qiagen, Inc., Santa Clarita, CA). The cagA status was determined as previously described [7].

2.4. Histology and CagA status

Biopsy specimens for histology were obtained from within 5 mm of the sites used for cytokine measurement. After arrival in Japan, the fixed specimens were embedded in paraffin wax and stained with hematoxylin and eosin and Giemsa stains, followed by evaluation by a single pathologist blinded to the patient’s clinical diagnosis or the characteristics of the H. pylori strains. The following features were evaluated on each slide: H. pylori density and the degree of mononuclear cell (MNC) and polymorphonuclear leucocyte (PMN) infiltrations, with reference to the updated Sydney System. The H. pylori density was also evaluated by immunohistochemistry with polyclonal anti-H. pylori antibody, as described previously [8]. The H. pylori density was scored based on the average density on the surface and the foveolar epithelium. If areas with widely different scores were obtained on the same specimen, an average based on the general evaluation of the biopsy was considered. Only areas without metaplasia were evaluated for the presence of H. pylori. Immunohistochemistry for CagA status was performed with polyclonal α-CagA antibody (Ab) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA), as described previously [8].

2.5. RNA analysis

The gastric mucosal IL-8 mRNA and IL-10 mRNA levels were measured. IL-10 is an anti-inflammatory cytokine [9] that is believed to be involved in the immunoregulatory response to H. pylori infection [10]. Gastric specimens were placed in RNAlater (Ambion® Carlsbad, CA, USA) and stored at −80°C until use. RNA was isolated from the gastric specimens by an experienced researcher (H.N.) blinded to the H. pylori status. mRNA was isolated by using a commercially available kit (Ambion® Carlsbad, CA, USA). Reverse-transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) was performed by using the SuperScript® III Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen™ Carlsbad, CA, USA). Real-time PCR was performed by TaqMan PCR. The quantification of IL-8, IL-10, and beta-actin mRNA levels were performed by using the ABI Prism 7300 Sequence Detection System (Life Technologies, CA, USA). Specific primers and TaqMan probes were designed by using the Gene Expression Assay Kit (Life Technologies, CA, USA). A standard curve was constructed with 7-fold serial dilutions of a partial IL-8, IL-10, and beta-actin cDNA levels into the pMD18-T Simple Vector (Sino Biological Inc., China). Reaction mixtures for PCR (20 µL) were prepared by mixing 4 µL of synthesized cDNA solution to 10 µL of 2X TaqMan Universal Master Mix (Life Technologies, CA, USA). The samples were placed in the analyzer and PCR was conducted according to the manufacturer’s instructions. To normalize the IL-8 and IL-10 mRNA expression levels, the beta-actin mRNA level was quantified in the same reactions by using TaqMan beta-actin control reagents (Life Technologies, CA, USA). The expression levels of IL-8 and IL-10 mRNA were expressed as the ratio of IL-8 and IL-10 mRNA to beta-actin mRNA.

2.6. Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed by using Mann–Whitney U test for non-parametric data. Correlation coefficients were calculated by the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient test. Correlation coefficients of IL-8 and IL-10 expression and histological grade/H. pylori density were calculated by Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All the analyses were performed using the JMP 10.0 software (SAS, Cary, NC, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Subjects

A total of 138 subjects from Bhutan (mean age: 38.5 y, age range: 17–92 y) and 155 subjects from the Dominican Republic (mean age: 47 y, age range: 17–91 y) (Table 1) were included in this study. The subjects from Bhutan were previously reported in a survey of the prevalence of H. pylori in Bhutan [5]. The prevalence of H. pylori was 64% in Bhutan and 59% in the Dominican Republic (Table 1). All the H. pylori-positive subjects were offered anti-H. pylori therapy.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study subjects

| Bhutan (N = 138) |

Dominican Republic (N = 155) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) (age range; years) | 38.5 (17–92) | 47.0 (17–91) |

| Gender (Male: Female) | 60:78 | 54:101 |

| H. pylori-positive (%) | 88 (64%) | 91 (58%) |

| H. pylori-positive by culture (%) | 73 (53%) | 57 (37%) |

3.2. cagA genotyping

From among the 88 H. pylori-positive tissue samples from Bhutanese subjects, 73 cases were successfully cultured and were examined for the cagA genotype. Three samples (4.1%) showed Western-type cagA and 70 samples (95.9 %) showed East-Asian type cagA genotypes. From among the 91 H. pylori-positive tissues samples from Dominican subjects, 55 samples could be cultured and the cagA genotype were examined. Of these 55 samples, 16 (29.1%) were cagA-negative and 39 (70.9%) were Western-type cagA (Table 2).

Table 2.

cagA genotypes among the two study countries

| Bhutan (n = 73) |

Dominican Republic (n = 57) |

|

|---|---|---|

| cagA(−) | 0 | 16 |

| Western-type cagA | 3 | 41 |

| East Asia-type cagA | 70 | 0 |

3.3. Histological findings and H. pylori density

We compared the histological findings and H. pylori density among the H. pylori-positive samples with reference to the updated Sydney System (Table 3). The atrophy scores were significantly higher in the samples from Bhutanese subjects (45% for grade 2 or 3) as compared to those from the Dominican subjects (16.4% for grade 2 and 0% for grade 3) (p < 0.001). The H. pylori-density scores for grade 2 or 3 were also significantly higher (p = 0.045) in the biopsies from Bhutan (71.5%) than in those from the Dominican Republic (56%). Although the overall PMN-infiltration scores were significantly higher in the biopsies from Bhutan than in those from the Dominican Republic, the proportion of biopsies from Bhutan (49%) versus that from the Dominican Republic (37%) with PMN scores of 2 or 3 did not show statistical significance (p = 0.161).

Table 3.

Grading by the updated Sydney System

| PMN |

MNC |

Atrophy |

H. pylori density |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade | Bhutan | Dominican Republic |

Bhutan | Dominican Republic |

Bhutan | Dominican Republic |

Bhutan | Dominican Republic |

| 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 11 | 9 | 8 |

| (%) | (0) | (5.5) | (0) | (0) | (1.1) | (12.1) | (10.2) | (8.8) |

| 1 | 45 | 52 | 22 | 26 | 47 | 65 | 16 | 32 |

| (%) | (51.1) | (57.1) | (25.0) | (28.0) | (53.4) | (71.4) | (18.2) | (35.2) |

| 2 | 37 | 31 | 56 | 55 | 36 | 15 | 26 | 41 |

| (%) | (42.1) | (34.1) | (63.6) | (60.4) | (40.9) | (16.5) | (29.6) | (45.1) |

| 3 | 6 | 3 | 10 | 10 | 4 | 0 | 37 | 10 |

| (%) | (6.8) | (3.3) | (11.4) | (11.0) | (4.6) | (0) | (42.1) | (11.0) |

| mean | 1.56 [1] | 1.35 [1] | 1.86 [2] | 1.82 [2] | 1.48 [1] | 1.04 [1] | 2.03 [2] | 1.58 [2] |

| P value | 0.04* | 0.64 | < 0.001* | < 0.001* | ||||

Abbreviations; PMN: polymorphonuclear leucocyte, MNC: mononuclear cell

3.4. IL-8 and IL-10 mRNA expression

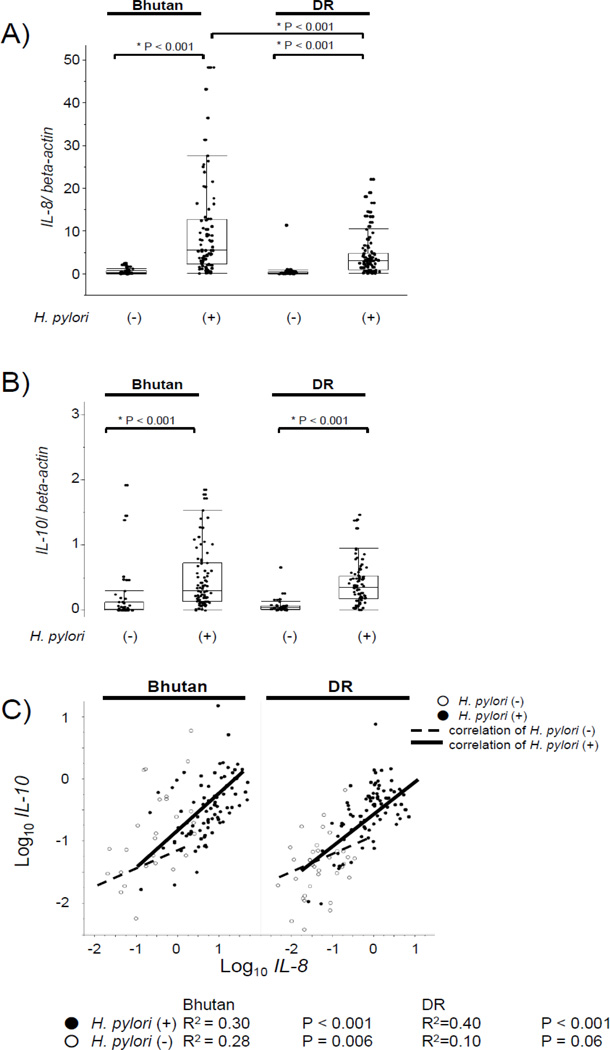

As expected, the IL-8 mRNA levels of the antral mucosa from H. pylori-positive samples were significantly greater than those from H. pylori-negative samples both in the subjects from Bhutan (median: 5.4, range: 0.12–48 versus median: 0.10, range: 0.0–2.4; p < 0.001) and the Dominican Republic (median: 3, range: 0.08–22 versus median: 0.07, range: 0.0–11.4; p < 0.001) (Figure 1A). The IL-8 mRNA levels of the antral mucosa from H. pylori-positive samples from Bhutanese subjects were significantly (approximately 2-fold) higher than those from the Dominican subjects (p < 0.001).

Figure 1.

A) IL-8 mRNA levels by H. pylori status and countries. The expression levels of IL-8 mRNA are expressed as a ratio to the beta-actin mRNA level. Data are expressed by box plotting.

B) IL-10 mRNA levels by H. pylori status and countries. The expression levels of IL-10 mRNA are expressed as a ratio to beta-actin mRNA level. Data are expressed by box plotting.

C) Correlation coefficient between IL-8 mRNA and IL-10 mRNA levels. Correlation coefficients were calculated by the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient test. White circles represent H. pylori-negative samples and black circles represent H. pylori-positive samples. Dotted line and straight lines show regression line of correlation coefficient of H. pylori-negative cases and H. pylori-positive cases between the IL-8 and IL-10 mRNA levels, respectively.

The IL-10 mRNA levels of antral biopsies of H. pylori-positive samples were also significantly higher than those of the H. pylori-negative samples in both subjects from Bhutan (median: 0.30, range: 0.00–15.2 versus median: 0.01, range: 0.00–0.69; p < 0.001) and the Dominican Republic (median: 0.35, range: 0.0–7.6 versus median: 0.04, range: 0.0–0.6; p < 0.0001) (Figure 1B). There were no significant differences between the countries, irrespective of their H. pylori status.

Significant positive, but weak correlations were observed between the IL-8 and IL-10 mRNA levels in samples from Bhutan (H. pylori-positive: R2 = 0.30, p < 0.001, H. pylori-negative: R2 = 0.28, p = 0.006) and the Dominican Republic (H. pylori-positive: R2 = 0.40, p < 0.001, H. pylori-negative: R2 = 0.10, p = 0.06), irrespective of the H. pylori status (Figure 1C).

3.5. Correlation between IL-8 and IL-10 mRNA levels and histological findings

The correlation between IL-8/IL-10 mRNA levels and histological findings/H. pylori density is shown in Supplemental Table 1. Significant positive correlations were noted between the IL-8 mRNA levels and PMN grades (Bhutan: correlation coefficient = 0.259, p = 0.015; Dominican Republic: correlation coefficient = 0.317, p = 0.003) and H. pylori density (Bhutan: correlation coefficient = 0.247, p = 0.020; Dominican Republic: correlation coefficient = 0.292, p = 0.005) in both the countries. The IL-10 mRNA levels of Bhutanese samples were positively correlated to the atrophy scores (correlation coefficient = 0.22, p = 0.038), unlike those of the Dominican samples.

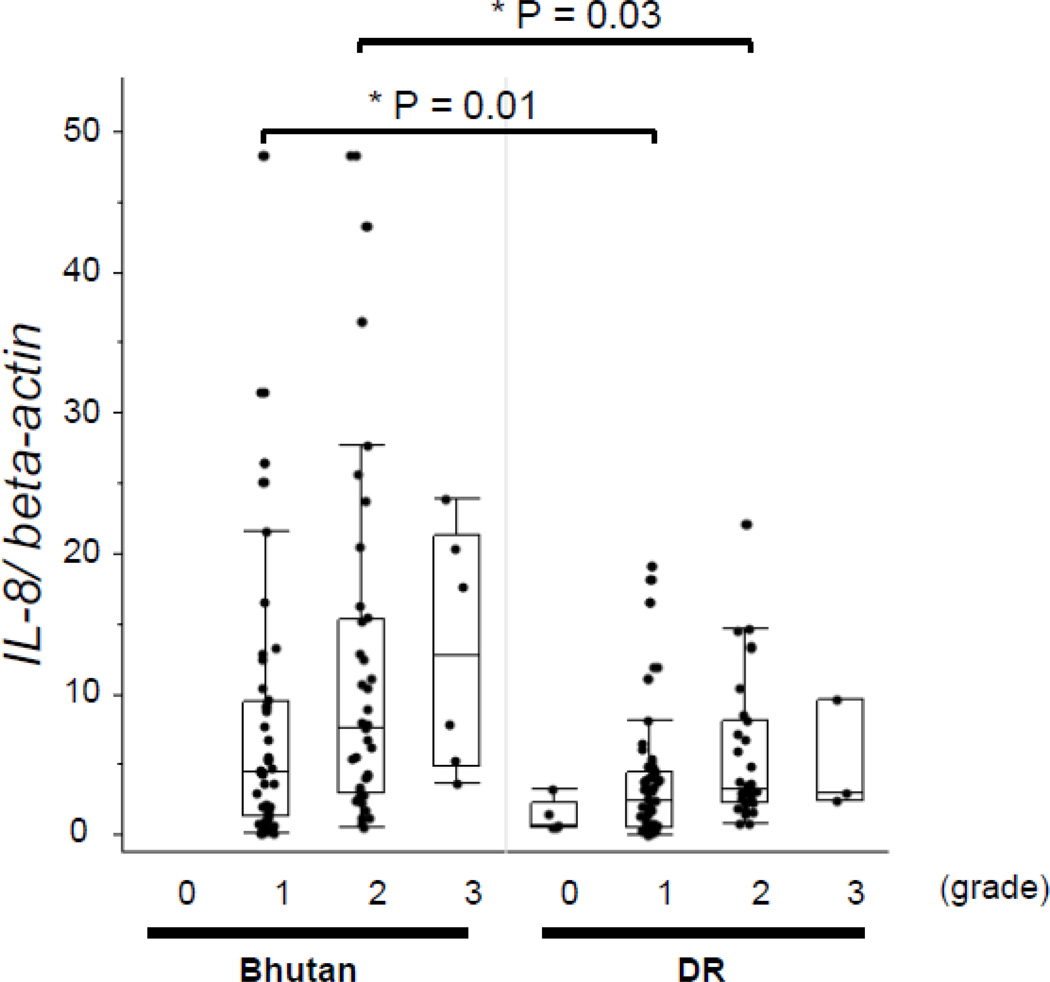

The IL-8 mRNA levels were significantly higher in biopsies from Bhutan as compared to those from the Dominican Republic on restricting the comparison to PMN infiltration scores of 1 (mild) or 2 (moderate) (p = 0.01 and p = 0.03, respectively) (Figure 2). The IL-10 mRNA levels were not significantly different between the biopsies from Bhutan and the Dominican Republic on comparing the levels among those with the same histological grade.

Figure 2. IL-8 mRNA levels by PMN infiltration.

The IL-8 mRNA levels were significantly higher in samples from Bhutanese subjects than in those from Dominican subjects on comparing the levels among the same PMN histological grade scores of 1 and 2. Data are expressed by box plotting.

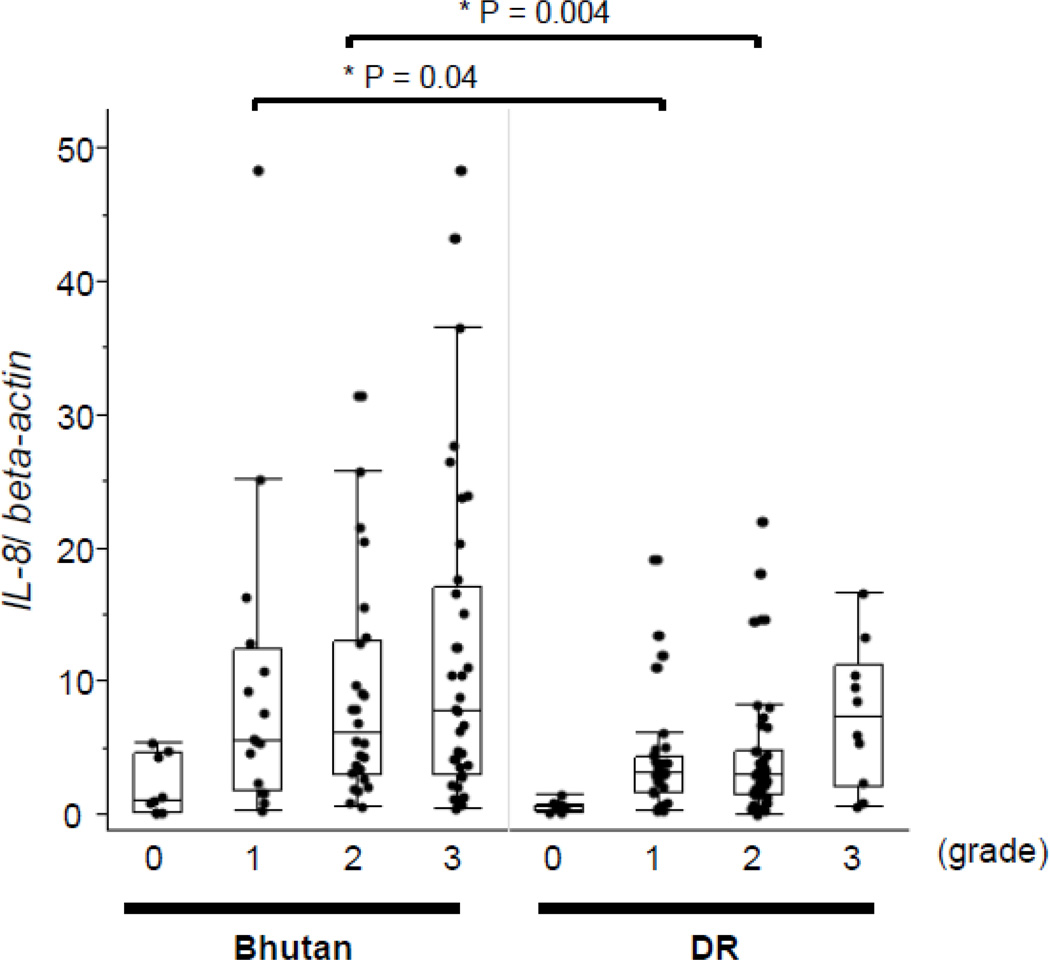

3.6. Correlation between IL-8 and IL-10 mRNA expression levels and H. pylori density

As significant correlation was noted between the IL-8 mRNA levels and H. pylori density, we examined the correlation of H. pylori density in H. pylori-positive samples with reference to the updated Sydney System (Figure 3). The mucosal IL-8 mRNA levels of samples with H. pylori-density scores of 1 and 2 were significantly higher in samples from Bhutanese subjects (medians: 5.5 and 6.2, respectively) than in those from the Dominican subjects (medians: 3.1 and 3.0, respectively) (p < 0.05 for both).

Figure 3. IL-8 mRNA levels by H. pylori density.

The IL-8 mRNA levels were significantly higher in samples from Bhutanese subjects than in those from Dominican subjects on comparing the levels among the same H. pylori-density scores of 1 and 2. Data are expressed by box plotting.

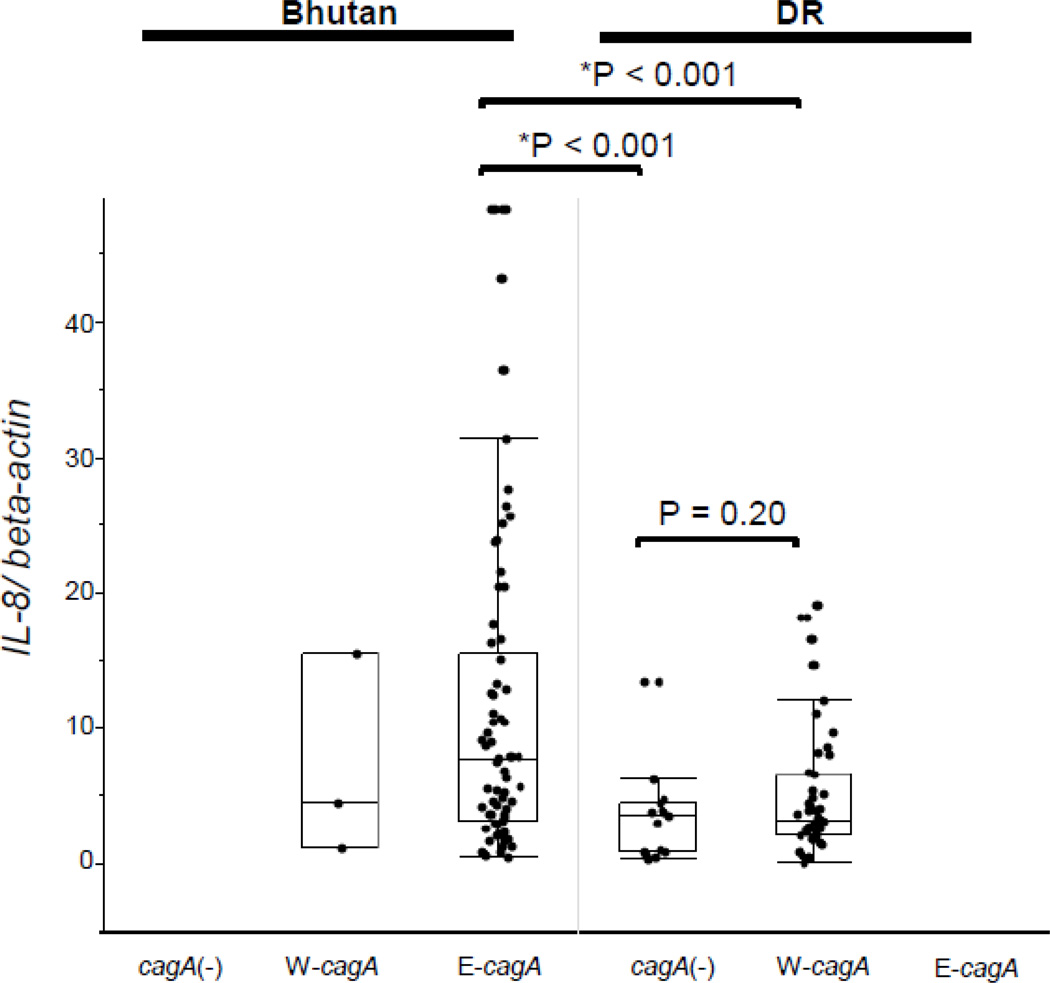

3.7. IL-8 expression in relation to cagA genotype and CagA status

The IL-8 mRNA levels were significantly greater for East Asia-type cagA samples from Bhutan than for Western-type cagA samples from the Dominican Republic and cagA(−) H. pylori-positive samples from the Dominican Republic (E-cagA from Bhutan; median: 7.6, range: 0.44–48 versus W-cagA from Dominican Republic; median: 3.5, range: 0.08–22; p < 0.001 versus cagA(−)from Dominican Republic; median: 3.2, range: 0.3–13; p < 0.001, respectively) (Figure 4). There were no significant differences between cagA(−) from Dominican Republic and W-cagA from Dominican Republic (p = 0.02) genotypes in this respect. The IL-10 mRNA levels were not significantly different in relation to the cagA genotype (E-cagA from Bhutan; median: 0.30, range: 0.00–5.2 versus W-cagA from Dominican Republic; median: 0.38, range: 0.00–7.6 versus cagA (-)from Dominican Republic; median: 0.30, range: 0.04–0.85) (data not shown).

Figure 4. IL-8 mRNA levels by cagA genotype and countries.

No samples from Bhutanese subjects were cagA-negative. The IL-8 mRNA levels of E-cagA from samples from Bhutanese subjects was significantly higher than those of W-cagA and cagA-negative samples from Dominican subjects. No difference between the Western-type cagA and cagA-negative genotypes was noted from the samples from Dominican subjects. The IL-8 mRNA levels of Western-type-cagA for samples from Bhutanese subjects were similar to those of Western-type- cagA for the samples from Dominican subjects. Data are expressed by box plotting.

E-cagA: East-Asian type cagA, W-cagA: Western-type cagAcagA(−): cagA-negative

We performed immunohistochemistry to determine the CagA status. In Bhutan, 70 samples were α-CagA positive from among 70 samples with α-H. pylori Ab-positive status, while in the Dominican Republic, 28 samples were α-CagA-negative and 61 samples were α-CagA positive from among 89 samples with α-H. pylori Ab-positive status. For the Dominican Republic subjects, the IL-8 mRNA levels of α-CagA-positive samples was significantly higher than those of the α-CagA-negative samples (median: 3.3, range: 0.08–22 versus median: 2.00, range: 0.31–18; p = 0.04, respectively).

4. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, prior reports describing inflammatory cytokine expression in H. pylori-infected gastric mucosa have been limited to a single region (eg. Japan, USA) [11]. In this study, samples were collected by the same team and RNA extraction and pathology diagnosis were performed by the same individuals, allowing for a comparison between areas that differed greatly in relation to gastric cancer incidence and H. pylori cagA genotype. CagA is a highly immunogenic protein injected into cells by a type IV secretion system [12, 13]. Most H. pylori isolates from the East Asian countries are cagA-positive as compared to 50–80% of the isolates from the Western countries [14]. The East Asia-type cagA differs from the Western-type cagA by the pattern of repeat sequences of the 3' region of cagA [14]. These repeat regions contain the Glu-Pro-Ile-Tyr-Ala (EPIYA) motif and is annotated according to segments (20–50 amino acids) flanking the EPIYA motifs (i.e., segments EPIYA-A, -B, -C, or -D). The East Asia-type cagA, containing EPIYA-D segments, exhibit a stronger binding affinity for Src homology 2 domain of Src homology 2-containing protein-tyrosine phosphatase (SHP-2), and a greater ability to induce morphological changes in the epithelial cells in vitro than Western-type cagA containing EPIYA-C segments [15]. Strains from Bhutan typically contain East Asia-type cagA, whereas strains from the Dominican Republic typically contain Western-type cagA.

East Asia-type cagA has been associated with a higher level of mucosal inflammation than Western-type cagA. Consistent with this observation, the gastric antral IL-8 mRNA levels were significantly higher in the H. pylori-infected individuals from Bhutan than from the Dominican Republic. In addition, a higher density of H. pylori was noted in the antral specimens from Bhutan; this finding is in concordance with a previous report of close association of H. pylori density to the gastric mucosal IL-8 mRNA levels [2]. Moreover, the H. pylori density of the antral mucosal biopsies from Bhutan was much higher than those of the gastric mucosa of infected individuals from the Dominican Republic; in both the cases, the IL-8 mRNA level was significantly correlated with the H. pylori density. The mucosal IL-8 mRNA levels among those with H. pylori-density scores of 1 (mild) or 2 (moderate) were significantly higher in samples from Bhutanese subjects (East Asia-type cagA) than in those from Dominican subjects [Western-type cagA or cagA (-)] (Figure 6). In addition, although the number of Western-type-positive strain from Bhutan was small, the mucosal IL-8 mRNA levels were similar between the samples with Western-type cagA from Bhutan and from Dominican Republic. These data suggest that the ability of H. pylori to induce IL-8 with the same density may be greater for East Asia-type strains than for Western-type cagA or cagA(−) strains. This hypothesis is in agreement with previous reports regarding differences in IL-8 response to East-Asian and Western type cagA from animal experiments [16].

However, more interestingly, the IL-8 mRNA levels were also significantly higher in biopsies from Bhutan compared to those from the Dominican Republic even when the comparison was restricted to PMN infiltration scores of 1 (mild) or 2 (moderate). In other words, there was a relatively low PMN response despite higher IL-8 mRNA levels in Bhutanese subjects. This finding is also consistent with the notion that East Asia-type cagA-positive strains are associated with increased expression of IL-8 mRNA as compared to Western-type cagA-positive strains, but with lesser effectiveness in eliciting a PMN response in some patients. Future experiments are needed to confirm this observation and to investigate whether host or environmental factors are responsible for this discrepancy. Recently, Gil et al. [17] reported that the mucosal PMN score was positively correlated with the number of Th17 cells expressing lymphocytes and negatively correlated with the Th17 cells/FOX3P+ ratio. Serrano et al. [18] also reported that H. pylori-positive children showed downregulated Th17 response in the gastric mucosa. We thus speculate that the reduced PMN response, despite higher IL-8 mRNA levels, may be related to downregulation of Th17 response. The overall PMN response may therefore be the result of both positive and inhibiting signals, although we assessed only the positive signal in this study.

The IL-10 mRNA levels of H. pylori-positive samples were not significantly different between the two countries, and no particular trend by histological grade and cagA genotype was noted. IL-10 also known as human cytokine synthesis inhibitory factor (CSIF), is an anti-inflammatory cytokine. Bodger et al. [19] described that in vitro-blocking of endogenous IL-10 secretion did not significantly increase the cytokine secretion in relation to the Western-type cagA strain. Our data confirmed that IL-10 secretion was independent of both East-Asia and Western-type cagA genotype [2]. However, the IL-10 mRNA levels from Bhutanese samples demonstrated a significant positive correlation coefficient with atrophy score, suggesting a need to perform in vivo experiments for analyzing the IL-10 expression and gastric atrophy.

Conclusion

The difference in the IL-8 expression reflected the differences in the disease manifestation patterns between the two countries.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

IL-8 expression levels from Bhutan were significantly higher than those from Dominican Republic, suggesting that the differences were mainly caused by bacterial factors.

However, IL-8 expression levels were significantly different between two countries even when we compared them within the same histological score.

Although the mechanisms to induce inflammation via IL-8 induction were unclear, severity of inflammation appears to be a critical factor in disease pathogenesis.

Acknowledgments

This paper is based on the work supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (DK62813) (YY) and DK56338 (DYG), Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) of Japan (22390085, 22659087, 24406015, and 24659200) (YY), (23790798) (SS), Strategic Young Researcher Overseas Visits Program for Accelerating Brain Circulation for Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS), the Strategic Funds for the Promotion of Science and Technology from Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST), and the National fund for Innovation and Scientific and Technological development (FONDOCYT) from the Ministry of Higher Education Science and Technology (MESCyT) of the Dominican Republic (MC).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Suerbaum S, Michetti P. Helicobacter pylori infection. The New England journal of medicine. 2002;347:1175–1186. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yamaoka Y, Kodama T, Kita M, Imanishi J, Kashima K, Graham DY. Relation between clinical presentation, Helicobacter pylori density, interleukin 1beta and 8 production, and cagA status. Gut. 1999;45:804–811. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.6.804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamaoka Y, Kita M, Kodama T, Sawai N, Kashima K, Imanishi J. Induction of various cytokines and development of severe mucosal inflammation by cagA gene positive Helicobacter pylori strains. Gut. 1997;41:442–451. doi: 10.1136/gut.41.4.442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yamaoka Y, Kato M, Asaka M. Geographic differences in gastric cancer incidence can be explained by differences between Helicobacter pylori strains. Internal medicine. 2008;47:1077–1083. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.47.0975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shiota S, Mahachai V, Vilaichone RK, Ratanachu-Ek T, Tshering L, Uchida T, et al. Seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric mucosal atrophy in Bhutan, a country with a high prevalence of gastric cancer. Journal of medical microbiology. 2013;62:1571–1578. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.060905-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vilaichone RK, Mahachai V, Shiota S, Uchida T, Ratanachu-ek T, Tshering L, et al. Extremely high prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in Bhutan. World journal of gastroenterology : WJG. 2013;19:2806–2810. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i18.2806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matsunari O, Shiota S, Suzuki R, Watada M, Kinjo N, Murakami K, et al. Association between Helicobacter pylori virulence factors and gastroduodenal diseases in Okinawa, Japan. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2012;50:876–883. doi: 10.1128/JCM.05562-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yasuda A, Uchida T, Nguyen LT, Kawazato H, Tanigawa M, Murakami K, et al. A novel diagnostic monoclonal antibody specific for Helicobacter pylori CagA of East Asian type. APMIS : acta pathologica, microbiologica, et immunologica Scandinavica. 2009;117:893–899. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2009.02548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shiota S, Murakawi K, Suzuki R, Fujioka T, Yamaoka Y. Helicobacter pylori infection in Japan. Expert review of gastroenterology & hepatology. 2013;7:35–40. doi: 10.1586/egh.12.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takahashi A, Shiota S, Matsunari O, Watada M, Suzuki R, Nakachi S, et al. Intact long-type dupA as a marker for gastroduodenal diseases in Okinawan subpopulation, Japan. Helicobacter. 2013;18:66–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2012.00994.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee KH, Cho MJ, Yamaoka Y, Graham DY, Yun YJ, Woo SY, et al. Alanine-threonine polymorphism of Helicobacter pylori RpoB is correlated with differential induction of interleukin-8 in MKN45 cells. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2004;42:3518–3524. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.8.3518-3524.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Covacci A, Censini S, Bugnoli M, Petracca R, Burroni D, Macchia G, et al. Molecular characterization of the 128-kDa immunodominant antigen of Helicobacter pylori associated with cytotoxicity and duodenal ulcer. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1993;90:5791–5795. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.12.5791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tummuru MK, Cover TL, Blaser MJ. Cloning and expression of a high-molecular-mass major antigen of Helicobacter pylori : evidence of linkage to cytotoxin production. Infection and immunity. 1993;61:1799–1809. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.5.1799-1809.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamaoka Y. Mechanisms of disease: Helicobacter pylori virulence factors. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;7:629–641. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2010.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hatakeyama M. Oncogenic mechanisms of the Helicobacter pylori CagA protein. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:688–694. doi: 10.1038/nrc1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fu HY, Asahi K, Hayashi Y, Eguchi H, Murata H, Tsujii M, et al. East Asian-type Helicobacter pylori cytotoxin-associated gene A protein has a more significant effect on growth of rat gastric mucosal cells than the Western type. Journal of gastroenterology and hepatology. 2007;22:355–362. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gil JH, Seo JW, Cho MS, Ahn JH, Sung HY. Role of Treg and TH17 Cells of the Gastric Mucosa in Children With Helicobacter pylori Gastritis. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 2014;58:252–258. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Serrano C, Wright SW, Bimczok D, Shaffer CL, Cover TL, Venegas A, et al. Downregulated Th17 responses are associated with reduced gastritis in Helicobacter pylori -infected children. Mucosal immunology. 2013;6:950–959. doi: 10.1038/mi.2012.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bodger K, Bromelow K, Wyatt JI, Heatley RV. Interleukin 10 in Helicobacter pylori associated gastritis: immunohistochemical localisation and in vitro effects on cytokine secretion. Journal of clinical pathology. 2001;54:285–292. doi: 10.1136/jcp.54.4.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.