Abstract

Background

Calcium dependent signaling mechanisms play a critical role in platelet activation. Unlike calcium-activated protease and kinase, the contribution of calcium-activated protein serine/threonine phosphatase in platelet activation is poorly understood.

Objective

To assess the role of catalytic subunit of protein phosphatase 2B (PP2B) or calcineurin in platelet function.

Results

Here, we showed that an increase in PP2B activity was associated with agonist-induced activation of human and murine platelets. Pharmacological inhibitors of the catalytic subunit of protein phosphatase 2B (PP2B-A) such as cyclosporine A (CsA) or tacrolimus (FK506) potentiated aggregation of human platelets. Murine platelets lacking the β isoform of PP2B-A (PP2B-Aβ−/−) displayed increased aggregation with low doses of agonist concentrations. Loss of PP2B-Aβ did not affect agonist-induced integrin αIIbβ3 inside-out signaling, but increased basal Src activation and outside-in αIIbβ3 signaling to p38 mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK), with a concomitant enhancement in platelet spreading on immobilized fibrinogen and greater fibrin clot retraction. Fibrinogen induced increased p38 activation in PP2B-Aβ−/− platelets were blocked by Src inhibitor. Both PP2B-Aβ−/− platelets and PP2B-Aβ depleted human embryonal kidney 293 αIIbβ3 cells displayed increased adhesion to immobilized fibrinogen. Filamin A, an actin crosslinking phosphoprotein that is known to associate with β3 was dephosphorylated on Ser2152 in fibrinogen adhered wild type but not in PP2B-Aβ−/− platelets. In a FeCl3 injury thrombosis model, PP2B-Aβ−/− mice showed decreased time to occlusion in the carotid artery.

Conclusion

These observations suggest that PP2B-Aβ by suppressing outside-in αIIbβ3 integrin signaling limits platelet response to vascular injury.

Keywords: Platelet aggregation, Fibrinogen, Platelets, beta(3) Integrin, Protein-Serine-Threonine Phosphatase

Introduction

At the site of injury, platelets respond to activation and inhibition signals (inside-out signals), which facilitate the engagement of integrin αIIbβ3 and the transmission of information to initiate cytoskeletal reorganization (outside-in signals). Intrinsic to the activation of platelets via the agonist (G protein coupled and collagen) receptors and integrin αIIbβ3 receptors is the initiation of phospholipase C (PLC β/γ) signaling pathways that increase intracellular calcium (Ca2+) concentration from the internal stores. (Ca2+) also enters into the platelets through the plasma membrane by a store-operated mechanism. Sustained (Ca2+) levels trigger calcium-dependent signaling and contribute to agonist-induced activation of αIIbβ3, granule exocytosis, platelet aggregation and αIIbβ3 dependent cytoskeletal reorganization [1]. Mechanistically, (Ca2+) dependent signaling relies on multiple effectors such as (Ca2+) activated -protease, -kinase and -phosphatase to regulate platelet function. Among these effectors, the role of calpain (Ca2+) -activated protease) [2] and classical Protein Kinase C (PKC) α, β isoforms (Ca2+) and diacylglycerol-activated kinases) in platelet function is understood [3,4]. In contrast, the contribution of (Ca2+) -activated protein phosphatase remains unexplored.

Protein phosphatase 2B (PP2B) or calcineurin is a (Ca2+) and calmodulin (CaM) activated serine/threonine (Ser/Thr) phosphatase composed of a 58–64 kDa catalytic subunit (PP2B-A) and a 19 kDa regulatory subunit (PP2B-B). Somatic cells express two isoforms of PP2B-A subunit (PP2B-Aα and PP2B-Aβ) and one isoform of PP2B-B subunit (PP2B-Bα; CNB1). Germ cells express the catalytic subunit PP2B-Aγ and the regulatory subunit PP2B-Bγ (CNB2) [5]. The PP2B-A subunit contains an autoinhibitory (AI) domain along with the binding sites for PP2B-B subunit and CaM. Interaction of (Ca2+) with CaM and PP2B-B subunit changes their conformation and facilitates their interaction with the respective binding sites on PP2B-A subunit. Structural changes induced by the binding of CaM and PP2B-B subunit to the PP2B-A subunit causes dissociation of the AI domain from the catalytic groove, thereby activating PP2B [5]. Immunosuppressive agents like cyclosporine A (CsA) and tacrolimus (FK506) form complexes with cyclophilins and FK506 binding proteins and inhibit the catalytic activity of PP2B [6].

PP2B is classically known to dephosphorylate and promote the nuclear translocation of nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) to enhance the transcription of genes in T cells and cardiac tissues [5]. Megakaryocytes express NFAT isoforms and attenuation of PP2B-NFAT pathway increase megakaryocyte and platelet numbers in vivo [7]. Although anucleate platelets express PP2B, its contribution in platelet function is unexplored. Here, using a pharmacological and genetic approach, we report that PP2B-Aβ limits platelet reactivity by suppressing cytoskeletal dependent outside-in αIIbβ3 signaling function.

Materials and method

Reagents

ADP and collagen were purchased from Helena Laboratories (Beaumont, TX), while thrombin was from Hematologic Technologies Inc. (Essex Junction, VT). Protease activated receptor 4 –activating peptide (PAR4-AP) AYPGKF was synthesized by the Protein Core at Baylor College of Medicine (BCM). CsA and FK506 were from Calbiochem-EMD Millipore (Darmstadt, Germany). Alexa 488-conjugated fibrinogen was from Invitrogen-life Technologies (Grand Island, NY). Human fibrinogen was from Enzyme Research Laboratories Inc. (South bend, IN). Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-mouse CD62 (P-selectin), Phycoerythrin (PE)–conjugated anti-mouse CD41 (αIIb) and control IgG tagged to PE or FITC were purchased from BD Bioscience (San Jose, CA). PE-conjugated JON/A antibody was from Emfret Analytics (Eibelstadt, Germany). Antibodies to phospho Src Tyr418, Src, phospho p38 (Thr180 Tyr182), p38, phospho filamin (Ser2152), and filamin were from Cell Signaling Technologies (Beverly, MA). Antibodies to PP2B-Aα, PP2B-Aβ were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Calcineurin cellular assay kit was from Enzo Life Sciences, Inc. (Farmingdale, NY). A preformed mix of four independent (SMART pool) siRNAs targeting human PP2B-Aβ and non-specific control siRNA pool were purchased from Dharmacon (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Lafayette, CO).

Mice

Animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at BCM. CnAβ−/− or PP2B-Aβ−/− mice were generated as previously described [8]. Experimental animals were generated by crossing male and female PP2B-Aβ+/− mice. Wild type (WT) and PP2B-Aβ−/− littermate mice matched for age (8–14 week’s old) and gender were used.

Human and mouse platelet preparation

Following an approval from the Institutional Review Board of BCM, blood was drawn in an acid/citrate/dextrose (ACD) anticoagulant at a ratio of 1:9 (vol/vol) from healthy fasting donors. Platelet rich plasma (PRP) was prepared by centrifuging blood at 200 x g for 15 minutes at room temperature. PRP supplemented with 75 nM of PGE1 was centrifuged at 1000 x g for 10 minutes at room temperature to obtain platelet pellet that was resuspended in Tyrode’s and re-centrifuged. Washed platelets were suspended in Tyrode’s buffer and the counts adjusted to 2.5 × 108 platelets/ml.

Mouse blood was collected from the inferior vena cava of isoflorane-anesthetized mice into 3.8% sodium citrate at the ratio of 1:10 (vol/vol) for studies with PRP, and into ACD at the ratio of 1:10 (vol/vol) for washed platelet studies. Blood was diluted 1:1 with Tyrode’s and PRP was isolated following centrifugation at 68 x g for 10 minutes. Washed platelets were obtained following additional centrifugation of PRP as we have described before [9]. Platelet counts in PRP and washed preparation from the WT and PP2B-Aβ was adjusted to 2.5 × 108/ml with the platelet poor plasma or Tyrode’s buffer respectively.

Protein phosphatase 2B assays

PP2B activity in the lysate obtained from platelets treated with various agonists was measured using the calcineurin cellular assay kit as we have performed before [10]. After depleting free phosphate from the lysate by gel filtration using desalting resins, the ability of PP2B in the lysate to dephosphorylate RII phosphopeptide was measured using Biomol Green reagent. Absorbance read at 620 nm was converted to amount of phosphate released using a phosphate standard curve.

Platelet aggregation, soluble fibrinogen binding, secretion and flow cytometry studies

Washed platelets and PRP from humans and mice were challenged with varying concentrations of agonist. Platelet aggregation was measured under stirring conditions using an eight channel Bio/Data PAP-8C aggregometer (Biodata Corporation, Horsham, PA). Resting and activated murine platelets diluted to 2.5 × 107/ml in Tyrode’s buffer with 1.8 mM CaCl2 and 0.49 mM MgCl2, was incubated with either Alexa 488-conjugated fibrinogen, FITC conjugated CD62P, PE conjugated CD41, PE conjugated JON/A (recognizes active murine αIIbβ3), FITC or PE tagged isotype control antibodies and measured by flow cytometry using EPICS-XL flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Miami, FL). In some experiments, washed platelets were stimulated with agonist and ATP release was measured by adding luciferin/luciferase reagent in a lumi-aggregometer (Chrono-Log Corp. Havertown, PA).

Platelet spreading, fibrin clot retraction and adhesion assays

Fibrinogen coated coverslips were incubated with ~1 × 107/ml platelets for varying time points at 37 °C. Adhered platelets were fixed with 3.7 % paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.01 % Triton X-100 and the staining of F-actin by rhodamine phallodin was visualized using a fluorescence microscope. Quantification of the surface area was performed using NIH Image J software. For fibrin clot retraction assays, PRP containing 2.5 × 108 platelets/ml and supplemented with 3 mM CaCl2 was incubated with 1 U/ml thrombin. The amount of liquid not incorporated into the clot was subtracted from the initial volume (150 μl) to ascertain the volume of clot over time. Clot volume was expressed as a percentage of the initial volume. For adhesion assays, washed murine platelets or human embryonal kidney 293 cells expressing αIIbβ3 [11] transfected with 100 nM siRNAs (targeting PP2B-Aβ and nonspecific control) were added to ninety six well plates coated with fibrinogen and blocked with bovine serum albumin for varying time points at 37 °C. After washing, adhesion was quantified by assaying for acid phosphatase activity at 405 nM. Percent adhesion was calculated as number of fibrinogen adhered platelets/cells divided by the total number of platelets/cells added to the well and multiplied by 100 as we have previously reported [9, 12].

Ferric chloride (FeCl3) injury thrombosis model and tail bleeding times

This model was performed using techniques similar to those we previously described [13]. Briefly, mice were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital sodium (50 mg/kg), with additional doses (25 mg/kg) given as needed. Mice were then placed on a custom Plexiglas tray and maintained at 37 °C with a homeothermic blanket and a rectal temperature probe (FHC, Inc, Bowdoin, ME). The right carotid artery was isolated through a midline cervical incision, and an ultrasonic flow probe (Transonic Systems, Ithaca, NY) was used to monitor carotid blood flow. A 1 × 2 mm piece of filter paper (Whatman #2, Maidstone, United Kingdom) saturated in 10 % FeCl3 (Sigma-Aldrich) was applied to the surface of the carotid artery for 1 minute. Three minutes after the onset of FeCl3 exposure, the vessel was rinsed with warm isotonic saline, and carotid blood flow was monitored continuously until the onset of flow cessation (>1 minute) or 30 minutes. The time taken for flow cessation lasting at least 30 seconds from the time FeCl3 was rinsed (time 0) was recorded. Tail bleeding time(s) were quantified as previously described [9]. Tails of anesthetized mice were severed 2 mm from the tip with a scalpel and immediately immersed in a tube containing PBS at 37 °C. The tails were transferred to a new tube every 30 seconds until bleeding was stopped and time for cessation of blood was recorded. Thrombosis and hemostasis assays were both recorded by investigators blinded to the genotype of the mice.

Statistics

Results were expressed as mean ± SEM. Student’s t test was used to analyze significance of the data. Non-parametric Mann Whitney U test was used to analyze time for occlusion in FeCl3 injury model. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

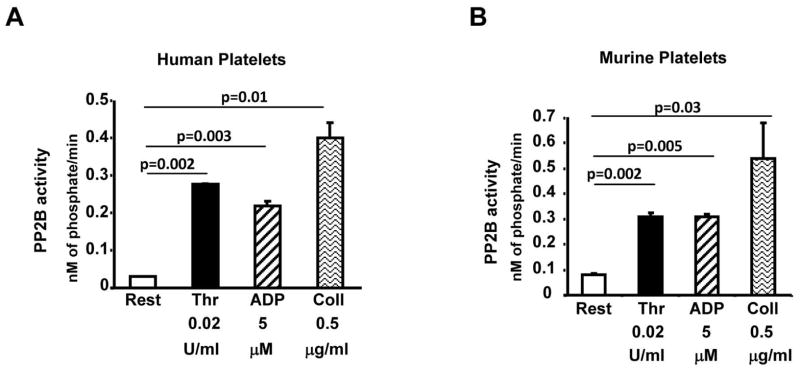

Stimulation of human and murine platelets with agonist is associated with an increased PP2B activity

A rise in intracellular platelet calcium level during agonist stimulation is likely to affect the activity of downstream effectors like calcium –activated kinases, proteases and phosphatases. We investigated the activity of the calcium activated protein phosphatase 2B (PP2B) in response to agonist exposure. Compared to the resting human platelets, treatment with thrombin, ADP and collagen enhanced PP2B activity (Fig. 1A). Similar findings were noticed with wild type murine platelets (Fig. 1B). PP2B activation in human and murine platelets was noticed as early as 2 minutes after agonist stimulation (not shown).

Fig. 1. Agonist stimulation increased PP2B activity in platelets.

Washed platelets from human (A) or wild type murine (B) were maintained in the resting state (Rest) or stimulated with thrombin (thr; 0.02 U/ml), ADP (5 uM) or collagen (Coll; 0.5 μg/ml) for 10 minutes. PP2B activity in the lysate was evaluated using calcineurin cellular assay kit. Data are mean ± SE from 3–4 experiments.

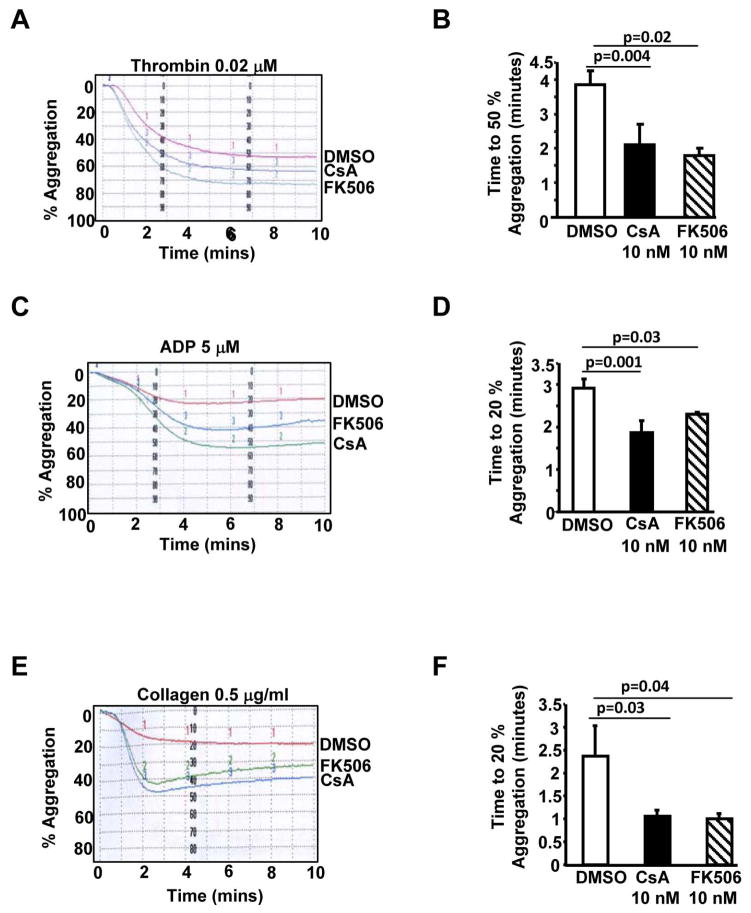

Pharmacological inhibitors of PP2B moderately increased agonist-induced human platelet aggregation

Next, we investigated the role of the catalytic subunit of PP2B (PP2B-A) in agonist-induced platelet aggregation. Compared to the control (DMSO), pretreatment of human platelets with cyclosporine A (CsA) or tacrolimus (FK506), resulted in a moderate increase in thrombin, ADP and collagen induced platelet aggregation (Figs. 2A, 2C and 2E). Importantly, the time to achieve 50% thrombin induced or 20% ADP and collagen induced aggregation was significantly decreased in CsA and FK506 treated platelets (Figs. 2B, 2D and 2F). These studies suggest that CsA and FK506 can potentiate low dose agonist induced platelet aggregation.

Fig. 2. PP2B inhibitors CsA and FK506 potentiated platelet aggregation.

Washed human platelets were pretreated with DMSO, CsA (10 nM) or FK506 (10 nM) for 30 minutes prior to studying aggregation induced by thrombin (A) ADP (C) or collagen (E). Time to achieve 50% thrombin-induced aggregation (B) and 20% aggregation for ADP (D) or collagen (F) is documented. Data are mean ± SE from 4–5 subjects.

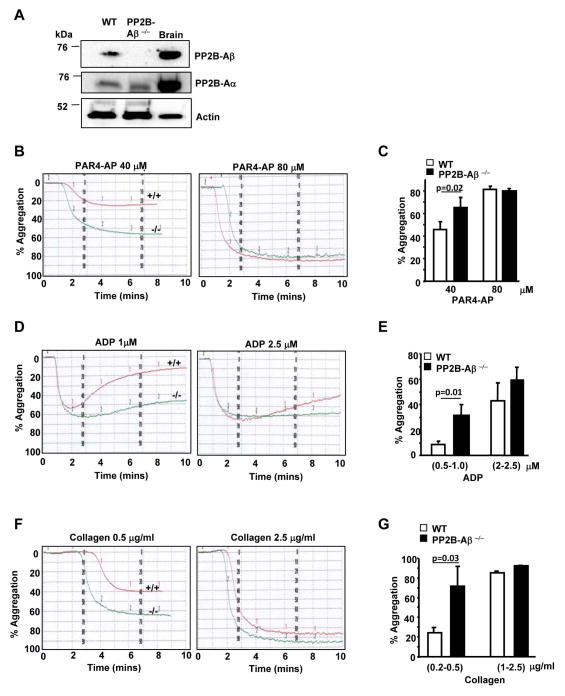

PP2B-Aβ−/− platelets exhibit enhanced agonist induced aggregation

Although CsA is a well-established PP2B inhibitor, it can also block the peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase activity [14] of cyclophilins and thereby impact mitochondrial permeability transition pore and platelet activation [15], an effect independent of PP2B. To specifically explore the contribution of PP2B in platelet function, we used mice deficient in the β isoform of the catalytic subunit of PP2B (PP2B-Aβ) [8]. Immunoblotting of platelet lysate with anti-PP2B-A isoform specific antibodies confirmed the absence of PP2B-Aβ, but not PP2B-Aα isoform in PP2B-Aβ−/− mice (Fig. 3A). Platelet count for PP2B-Aβ−/− mice (mean ± SEM 724.8 × 103/mm3 ± 55.1) were comparable to wild type (WT) mice (700.65 × 103/mm3 ± 35.63).

Fig. 3. PP2B-Aβ−/− platelets display enhanced aggregation to low dose agonist.

(A) Lysate from wild type (WT), PP2B-Aβ−/− platelets or mouse brain (brain; positive control) were immunoblotted with PP2A-β, PP2B-Aα and actin antibodies. (B) PRP from WT or PP2B-Aβ−/− mice was challenged with PAR4-AP, ADP (D) and collagen (F). Final percentage aggregation to varying concentrations of PAR4-AP (C), ADP (E) and collagen (G) is indicated as mean ± SE from 5–6 experiments.

We studied agonist induced PRP aggregation to assess the role of PP2B-Aβ in platelet function. Compared to the WT, PP2B-Aβ−/− platelets displayed increased aggregation to a low dose of protease-activated receptor 4 activating peptide (PAR4-AP), ADP and collagen (Figs. 3B, 3D and 3F). PP2B-Aβ−/− platelets also showed increased aggregation to collagen related peptide (CRP), an agonist for GPVI (not shown). Final aggregation to a range of low but not high concentrations of each agonist was significantly increased in PP2B-Aβ−/− platelets (Figs. 3C, 3E and 3G). Hyper aggregation response to additional agonist was also noted when studies were performed using washed platelets (Supplementary Fig. 1), suggesting that the enhanced phenotype was intrinsic to platelets. Integrin αIIbβ3 levels were comparable in resting and agonist-activated WT and PP2B-Aβ−/− washed platelets and could not account for the increased platelet function in PP2B-Aβ−/− platelets (Fig. 4C).

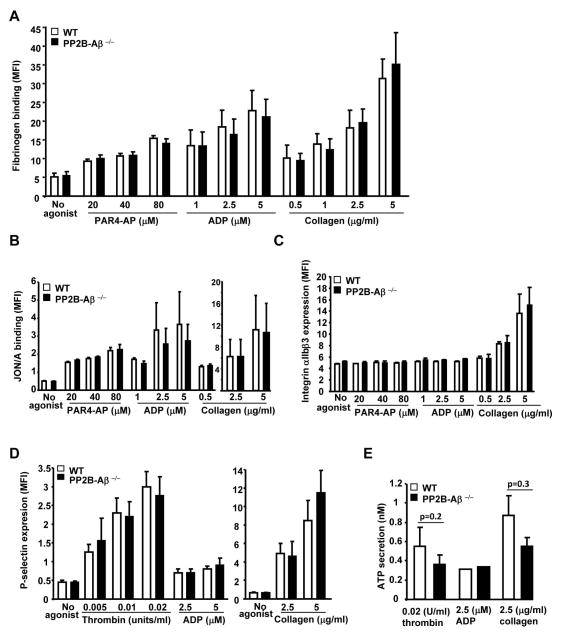

Fig. 4. Inside-out signaling to αIIbβ3 and granule secretion is normal in PP2B-Aβ−/− platelets.

Washed platelets from WT and PP2B-Aβ−/− mice were stimulated with PAR4-AP, ADP and collagen in the presence of (A) Alexa 488 fibrinogen. Bound fibrinogen was measured by flow cytometry as mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) (N=6–7). Fibrinogen binding in WT and PP2B-Aβ−/− platelets was blocked by addition of EDTA (not shown). Washed platelets were incubated with anti-JON/A PE antibody (N=4–6) (B), anti-αIIb FITC antibody (N=3) (C) and anti-P-selectin antibody (N=3–6) (D) and MFI measured by flow cytometry. Values from isotype control antibodies were subtracted to obtain MFI. (E). ATP release was studied in washed platelets by measuring luciferin/luciferase stimulated with thrombin and collagen (N=3–6), and ADP (N=2).

Comparable inside-out signaling response in PP2B-Aβ−/− platelets

We evaluated soluble fibrinogen binding to assess whether the loss of PP2B-Aβ affected agonist-induced integrin αIIbβ3 inside-out signaling. Agonist-induced soluble fibrinogen binding was comparable between the WT and the PP2B-Aβ−/− platelets (Fig. 4A). Consistent with these findings, the activation status of integrin αIIbβ3, as assessed by murine αIIbβ3 activation specific JON/A antibody was not altered between WT and the PP2B-Aβ−/− platelets (Fig. 4B). To evaluate if secretion of platelet granule contents was altered in PP2B-Aβ−/− platelets, we assessed agonist induced P-selectin (α granule) expression and ATP (dense granule) release. Expression of P-selectin induced by agonist stimulation was not significantly altered between the WT and the PP2B-Aβ−/− platelets (Fig. 4D). Likewise, the release of ATP was not significantly altered by the loss of PP2B-Aβ, despite a slight decreased trend in thrombin and collagen induced ATP secretion (Fig. 4E). Taken together, these studies indicate that agonist-induced αIIbβ3 expression, αIIbβ3 activation, soluble fibrinogen binding and secretion of both P-selectin and ATP was relatively unaffected by the loss of PP2B-Aβ.

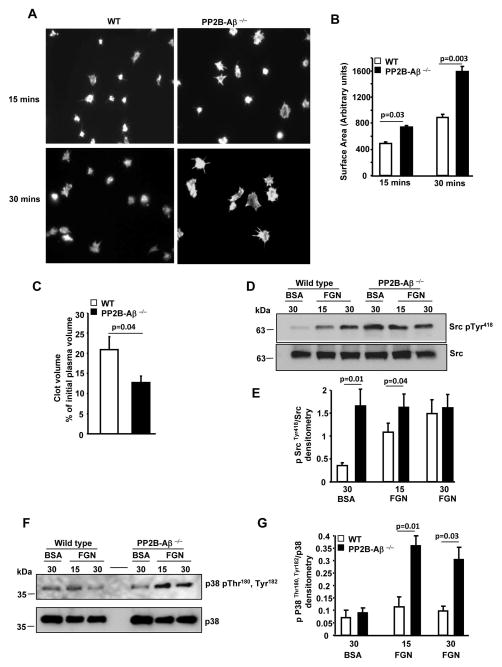

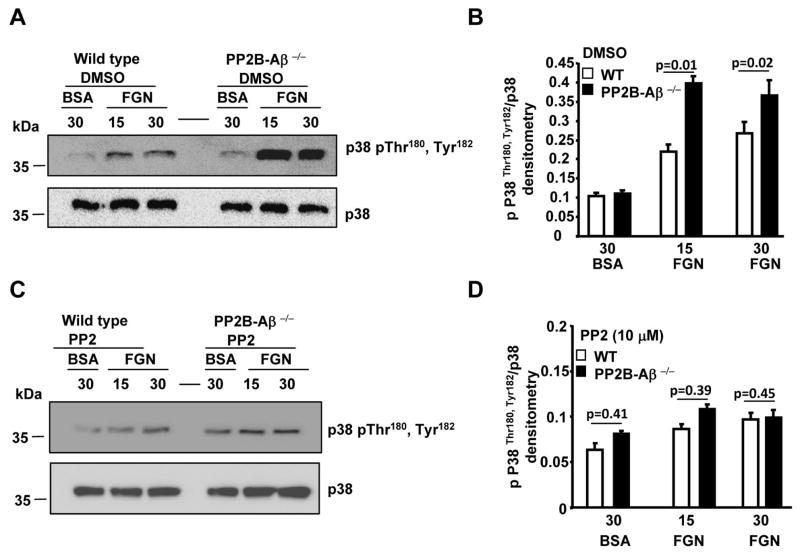

Loss of PP2B-Aβ enhanced outside-in signaling

Next, we evaluated whether post-fibrinogen engagement events were altered in PP2B-Aβ−/− platelets by assessing functional responses dependent on platelet cytoskeletal rearrangement. Compared to the WT platelets, PP2B-Aβ−/− platelets displayed increased filopodial extensions on immobilized fibrinogen (Fig. 5A). Quantification of platelets from multiple studies revealed significant increase in the surface area for PP2B-Aβ−/− platelets (Fig. 5B). To validate these findings, fibrin clot retraction, an independent outside-in signaling function was also examined. Compared to the WT, PP2B-Aβ−/− platelets displayed enhanced clot retraction (Fig. 5C). Given the crucial role of Src in facilitating outside-in αIIbβ3 signaling [16, 17], we evaluated the phosphorylation of Src Tyr418 within the kinase domain that promotes Src activity. Compared to platelets suspended over the BSA substrate, fibrinogen engagement stimulated Src Tyr418 phosphorylation in WT platelets. In contrast, loss of PP2B-Aβ robustly stimulated basal Src Tyr418 phosphorylation independent of integrin engagement, as evident by an increased Src phosphorylation of PP2B-Aβ−/− platelets on BSA (Figs. 5D and 5E). Increased basal Src phosphorylation was also noticed in unstimulated PP2B-Aβ−/− platelets (not shown). Since clot retraction and/or platelet spreading are dependent on p38 activation [18, 19], we also evaluated p38 signaling. Compared to the WT platelets, fibrinogen adhered PP2B-Aβ−/− platelets displayed increased phosphorylation of residues Thr180 and Tyr182 of P38, a surrogate marker of its activation (Figs. 5F and 5G). To assess the relationship between the increased basal Src and fibrinogen-induced p38 activation in PP2B-Aβ−/− platelets, we tested p38 activation in the presence of PP2, a Src inhibitor. Pretreatment with control DMSO did not alter fibrinogen-induced increased p38 activation in PP2B-Aβ−/− platelets (Figs. 6A and 6B). However, compared to the control DMSO, pretreatment with PP2 blocked the increased p38 activation of PP2B-Aβ−/− platelets (Figs. 6C and 6D).

Fig. 5. Outside-in signaling to αIIbβ3 is enhanced in PP2B-Aβ−/− platelets.

(A) Washed platelets were added on immobilized fibrinogen for 15 and 30 minutes and actin fibers stained with rhodamine phallodine. (B) Surface area of 50 platelets spread on fibrinogen from 5–6 experiments was quantified. (C) Fibrin clot retraction was evaluated following addition of thrombin to PRP and volume of the clot expressed as ± SEM of 6 experiments. Lysate of platelets suspended on BSA or adhered on immobilized fibrinogen (FGN) was immunoblotted with anti-phospho Src Tyr418 and Src antibodies (D) or phospho-Thr180, Tyr182 and p38 antibodies (F). Quantification of Src activation (E) or p38 activation (G) from 4–5 experiments.

Fig. 6. Increased p38 activation in fibrinogen adhered PP2B-Aβ−/− platelets is blocked by Src inhibitor.

Platelets pretreated with DMSO (A and B) or with 10 μM PP2 (C and D) were either suspended on BSA or adhered on FGN. Lysate was immunoblotted with anti-phospho-Thr180, Tyr182 and p38 antibodies (A and C). Quantification of p38 activation from (B and D) from 4 experiments.

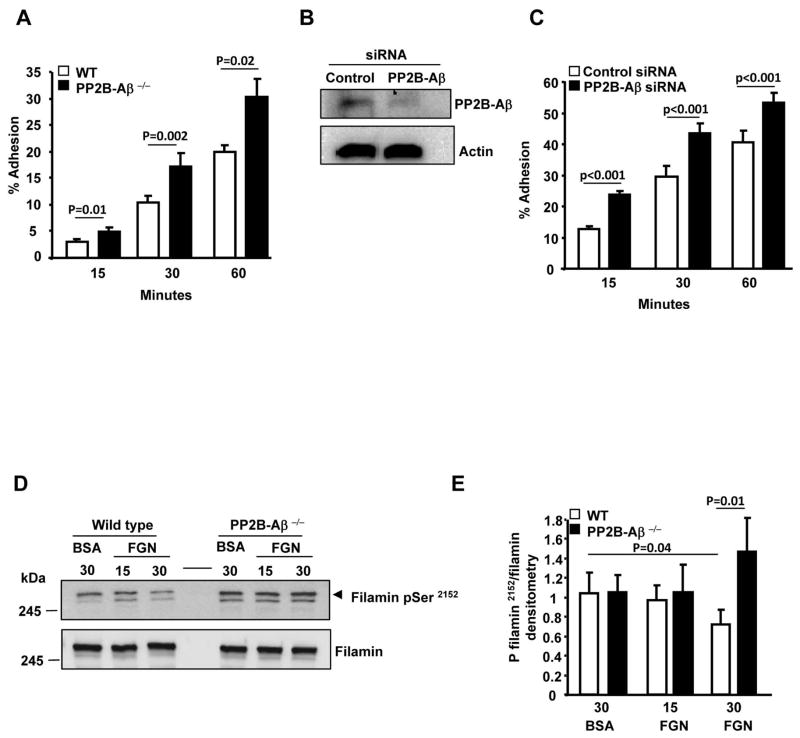

Since platelet deposition at thrombus sites may involve platelet adhesion to immobilized fibrinogen, we studied platelet adhesiveness. Adhesion of PP2B-Aβ−/− platelets to immobilized fibrinogen was enhanced when compared to WT platelets (Figure 7A). siRNA mediated depletion of PP2B-Aβ in human kidney embryonal 293 αIIbβ3 cells (Fig. 7B) also resulted in an increased adhesion to immobilized fibrinogen (Fig. 7C). Previous studies have identified that PP2B can dephosphorylate recombinant filamin A (FLNa) fragment at the C-terminal Ser2152 [20]. FLNa is an actin cross linking protein that participates in cell adhesion, spreading, migration [21] and can also interact with integrins β1A, β2, β3 and β7 [22, 23, 24]. Therefore, we examined FLNa Ser2152 phosphorylation in PP2B-Aβ−/− platelets. Adhesion of WT platelets to immobilized fibrinogen led to the dephosphorylation of FLNa Ser2152. In contrast, the dephosphorylation of FLNa Ser2152 was not evident in fibrinogen engaged PP2B-Aβ−/− platelets (Figs. 7D and 7E). Taken together, these studies indicate that loss of PP2B-Aβ leads to an enhanced outside-in αIIbβ3 signaling via the Src-p38 axis.

Fig. 7. Increased adhesiveness and phosphorylation of filamin A on Ser2152 in PP2B-Aβ−/− platelets.

(A) Washed platelets were incubated with immobilized fibrinogen and adhesion quantified. Data are expressed as ± SEM of 4 experiments. (B) Lysate from the control siRNA and PP2B-Aβ depleted 293 αIIbβ3 cells were immunoblotted with anti-PP2B-Aβ and anti-actin (loading). (C) Adhesion of 293 αIIbβ3 cells treated with control or PP2B-Aβ siRNA to fibrinogen. Data are expressed as ± SEM of 5 experiments. (D) Lysate of platelets suspended on BSA (30 mins) or adhered on immobilized fibrinogen was immunoblotted with anti-phospho FLNa Ser2152 and FLNa antibodies (E) Quantification of FLNa phosphorylation from 4 experiments.

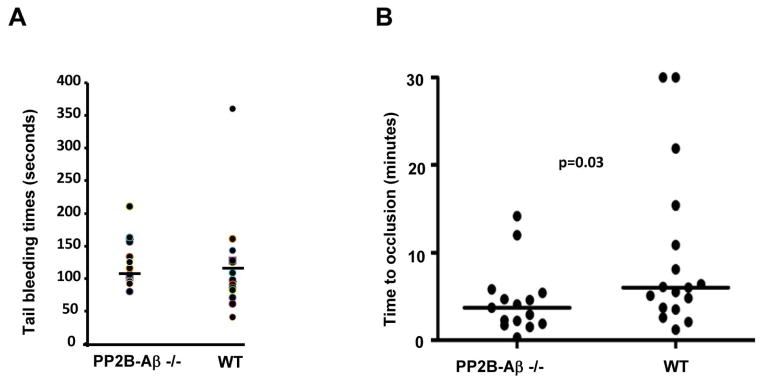

PP2B-Aβ−/− mice display prothrombotic phenotype in a FeCl3 induced thrombosis model

Tail bleeding assays were performed to assess the consequence of the loss of PP2B-Aβ on hemostasis. Tail bleeding time(s) were not significantly different between the WT and PP2B-Aβ−/− mice (Fig. 8A). Lastly, the contribution of PP2B-Aβ in in vivo thrombosis was examined using a FeCl3 induced carotid artery thrombosis model. Carotid artery of the WT and PP2B-Aβ was injured with 10% FeCl3 and the time for complete occlusion was monitored by a probe that measures blood flow. PP2B-Aβ−/− mice revealed a moderate but significant reduction in the time required for complete and stable vessel occlusion (Fig. 8B). Thus, the loss of PP2B-Aβ potentiates thrombosis in a FeCl3 injury model.

Fig. 8. Contribution of PP2B-Aβ in hemostasis and thrombosis models.

(A) Tail vein bleeding time(s) from 15 WT and PP2B-Aβ−/− mice. The horizontal line depicts average time (126 ± 9 seconds for PP2B-Aβ−/− and 117 ± 17 seconds for WT mice) (B) Carotid arteries from 17 WT and PP2B-Aβ−/− mice were subjected to a FeCl3 injury and the time to vessel occlusion measured. Median time (horizontal line) to occlusion is shown. The mean occlusion time for PP2B-Aβ−/− mice was 4.5 ± 1 minutes while that of WT was 9.6 ± 2.2 minutes.

Discussion

Increased risk of thromboembolic complications in renal transplant patients on immunosuppressant drugs like CsA and FK506 has prompted investigators to examine the contribution of these immunosuppressants on platelet function. Enhanced platelet aggregation to adrenaline, ADP and collagen was noticed in CsA (250–500 ng/ml) treated PRP [25]. Platelet suspension devoid of plasma in the presence of 600 ng/ml of CsA or FK506 displayed increased aggregation and greater serotonin release to ADP, while CsA augmented ADP induced binding of radiolabelled fibrinogen to platelets [26]. CsA (200 μg/ml) also enhanced collagen induced platelet procoagulant response [27]. The hyper functional platelet phenotype in these studies was observed with high concentrations of CsA. Since the apparent IC50 of CsA for PP2B inhibition is in the range of 10–100 nM, we performed studies with 10 nM CsA (~12 ng/ml) in washed platelets and noticed potentiation of aggregation response (Fig. 2). Although a prothrombotic phenotype for CsA or the ability of CsA to block PP2B is not disputed, the contribution of non-PP2B target of CsA (cyclophilins) cannot be ruled out in these studies. In a converse approach, addition of recombinant human PP2B-B regulatory subunit to rabbit or sheep PRP suppressed ADP-induced platelet aggregation [28]. To specifically identify the contribution of PP2B in platelet function, we utilized mice deficient in the β isoform of the catalytic subunit of PP2B. Other PP2B genetic models were not considered here because mice lacking the α isoform of the catalytic subunit PP2B (PP2B-Aα) die within three weeks of birth [29] and mice deficient in the α isoform of the regulatory subunit of PP2B (PP2B-Bα; Cnb1) are embryonically lethal [30].

Loss of PP2B-Aβ did not recapitulate the increased platelet counts displayed by the attenuation of NFAT-PP2B pathway [7]. Perhaps, this reflects a potential redundancy by the α isoform of PP2B. Although PP2B-Aβ−/− platelets displayed enhanced agonist-induced platelet aggregation (Fig. 3), agonist-induced αIIbβ3 expression, activation, soluble fibrinogen binding and secretion of α and dense granule contents were not significantly altered in PP2B-Aβ−/− platelets (Fig. 4). These findings suggest that the β isoform of PP2B is not involved in agonist induced inside-out αIIbβ3 signaling. Alternatively, the α isoform of PP2B may have compensated for the loss of PP2B-Aβ. Interestingly, PP2B-Aβ−/− platelets exhibited enhanced spreading, clot retraction and adhesion (Figs. 5 and 7). The ability of PP2B-Aβ to negatively regulate αIIbβ3 adhesiveness was also recapitulated in αIIbβ3 expressing model cells (Fig. 7), suggesting that this phenotype is intrinsic to PP2B-Aβ. Selective potentiation of outside-in but not inside-out signaling in PP2B-Aβ−/− platelets may suggest that the loss of PP2B-Aβ is unlikely to globally alter calcium homeostasis. Indeed, cyclophilin A but not PP2B was identified to be critical for Ca2+ reuptake by sarcoendoplasmic Ca2+ adenosine triphosphatase in platelets [31]. In contrast, loss of PP2B-Aβ likely affects the cytoskeletal compartment by altering signaling that is initiated by the engagement of integrin αIIbβ3.

One such αIIbβ3 proximal signaling molecule is Src, whose activation facilitates anchorage dependent cellular function [16, 17]. Although integrin engagement activated Src in WT platelets, a substantial enhancement in basal Src activation was observed in the PP2B-Aβ−/− platelets. (Fig. 5). Activation of p38, which participates in platelet clot retraction and/or spreading [18, 19], was also markedly up regulated in fibrinogen engaged PP2B-Aβ−/− platelets (Fig. 5). Consistent with this observation, activation of PP2B-Aβ in cardiac myocytes was associated with down regulation of p38 activation [32]. Interestingly, the increased p38 activation in fibrinogen adhered PP2B-Aβ platelets was blocked by Src inhibitor (Fig. 6). These studies suggest that deregulated Src signaling caused by the loss of PP2B-Aβ was relayed to the p38 MAPK following integrin ligation.

Since outside-in signaling often regulates cytoskeletal rearrangement, we considered whether one or more cytoskeletal proteins, including FLNa may represent targets of PP2B-Aβ. Patients with filaminopathy A caused by truncating FLNa mutations displayed low levels of FLNa and increased platelet spreading on fibrinogen [33]. Consistent with the reports that cAMP dependent PKA phosphorylates FLNa Ser2152 [34, 35], we observed basal phosphorylation of FLNa Ser2152 in unstimulated platelets. Importantly, fibrinogen engagement for 30 minutes in WT but not PP2B-Aβ−/− platelet led to filamin dephosphorylation. Ser2152 phosphorylation of FLNa a) protects FLNa from calpain cleavage [34, 20], b) may facilitate integrin binding to filamin [36] and c) positively correlates with membrane ruffle formation and migration of melanoma cells [37]. FLNa also serves as a scaffold to recruit proteins such as Rho, Rac, Cdc42 that are involved in the remodeling of the cytoskeleton and Syk, which is required for outside-in signaling [21, 38]. It is possible that the increased FLNa Ser 2152 phosphorylation in fibrinogen engaged PP2B-Aβ−/− platelets might stabilize cytoskeleton and thereby support increased adhesion and spreading, by altering its interaction with one of more effectors or the interaction of FLNA with β3.

Two issues highlight potential caveats in our study: a) confounding effect of PP2B-Aα isoform in the PP2B-Aβ−/− platelets, b) global loss of PP2B-Aβ in hematopoietic cells other than platelets may influence the in vivo thrombosis studies. In conclusion, our studies support a mechanism whereby the loss of PP2B-Aβ has little effect on direct αIIbβ3 activation, but rather potentiates prothrombotic phenotype following post-fibrinogen occupancy via the Src-p38 axis. Thus, platelet activation at the site of vascular injury is coupled to a PP2B-Aβ driven signaling machinery, which limits platelet reactivity by dampening outside-in αIIbβ3 signaling. Harnessing the suppressive role of PP2B-Aβ may offer a new anti-thrombotic strategy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants HL081613 (National Institutes of Health) and 13 GRNT17260021 (American Heart Association). K. V. Vijayan is supported by the Mary R. Gibson Foundation and the Alkek Foundation.

Footnotes

Addendum:

T. Khatlani, S. Pradhan, Q. Da, F. C. Gushiken, A. L. Bergeron, K. W. Langlois and K. V. Vijayan designed different aspects of the study, generated data and analyzed them. J. D. Molkentin provided the animal model. K. V. Vijayan and R. E. Rumbaut, designed the study, analyzed and interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. A. L. Bergeron proofread the manuscript.

Disclosure of conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Reference List

- 1.Varga-Szabo D, Braun A, Nieswandt B. Calcium signaling in platelets. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7:1057–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Azam M, Andrabi SS, Sahr KE, Kamath L, Kuliopulos A, Chishti AH. Disruption of the mouse mu-calpain gene reveals an essential role in platelet function. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:2213–20. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.6.2213-2220.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Konopatskaya O, Gilio K, Harper MT, Zhao Y, Cosemans JM, Karim ZA, Whiteheart SW, Molkentin JD, Verkade P, Watson SP, Heemskerk JW, Poole AW. PKCα regulates platelet granule secretion and thrombus formation in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:399–07. doi: 10.1172/JCI34665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buensuceso CS, Obergfell A, Soriani A, Eto K, Kiosses WB, Arias-Salgado EG, Kawakami T, Shattil SJ. Regulation of Outside-in Signaling in Platelets by Integrin-associated Protein Kinase Cβ. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:644–53. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410229200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shibasaki F, Hallin U, Uchino H. Calcineurin as a multifunctional regulator. J Biochem (Tokyo) 2002;131:1–15. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a003063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu J, Farmer JD, Jr, Lane WS, Friedman J, Weissman I, Schreiber SL. Calcineurin is a common target of cyclophilin-cyclosporin A and FKBP-FK506 complexes. Cell. 1991;66:807–15. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90124-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zaslavsky A, Chou ST, Schadler K, Lieberman A, Pimkin M, Kim YJ, Baek KH, Aird WC, Weiss MJ, Ryeom S. The calcineurin-NFAT pathway negatively regulates megakaryopoiesis. Blood. 2013;121:3205–15. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-04-421172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bueno OF, Brandt EB, Rothenberg ME, Molkentin JD. Defective T cell development and function in calcineurin A β-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:9398–03. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152665399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gushiken FC, Hyojeong H, Pradhan S, Langlois KW, Alrehani N, Cruz MA, Rumbaut RE, Vijayan KV. The catalytic subunit of protein phosphatase 1 gamma regulates thrombin-induced murine platelet αIIbβ3 function. PLoS One. 2009;4:e8304. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nolasco LH, Gushiken FC, Turner NA, Khatlani TS, Pradhan S, Dong JF, Moake JL, Vijayan KV. Protein phosphatase 2B inhibition promotes the secretion of von Willebrand factor from endothelial cells. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7:1009–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03355.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vijayan KV, Goldschmidt-Clermont PJ, Roos C, Bray PF. The PlA2 polymorphism of integrin β3 enhances outside-in signaling and adhesive functions. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:793–02. doi: 10.1172/JCI6982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alrehani N, Pradhan S, Khatlani T, Kailasam L, Vijayan KV. Distinct roles for the α, β and γ1 isoforms of protein phosphatase 1 in the outside-in αIIbβ3 integrin signalling-dependent functions. Thromb Haemost. 2013;109:118–26. doi: 10.1160/TH12-04-0237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dasgupta SK, Le A, Chavakis T, Rumbaut RE, Thiagarajan P. Developmental endothelial locus-1 (Del-1) mediates clearance of platelet microparticles by the endothelium. Circulation. 2012;125:1664–72. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.068833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steinmann B, Bruckner P, Superti-Furga A. Cyclosporin A slows collagen triple-helix formation in vivo: indirect evidence for a physiologic role of peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans-isomerase. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:1299–03. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jobe SM, Wilson KM, Leo L, Raimondi A, Molkentin JD, Lentz SR, Di PJ. Critical role for the mitochondrial permeability transition pore and cyclophilin D in platelet activation and thrombosis. Blood. 2008;111:1257–65. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-092684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Su X, Mi J, Yan J, Flevaris P, Lu Y, Liu H, Ruan Z, Wang X, Kieffer N, Chen S, Du X, Xi X. RGT, a synthetic peptide corresponding to the integrin β3 cytoplasmic C-terminal sequence, selectively inhibits outside-in signaling in human platelets by disrupting the interaction of integrin αIIbβ3 with Src kinase. Blood. 2008;112:592–02. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-110437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ablooglu AJ, Kang J, Petrich BG, Ginsberg MH, Shattil SJ. Antithrombotic effects of targeting αIIbβ3 signaling in platelets. Blood. 2009;113:3585–92. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-09-180687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flevaris P, Li Z, Zhang G, Zheng Y, Liu J, Du X. Two distinct roles of mitogen-activated protein kinases in platelets and a novel Rac1-MAPK-dependent integrin outside-in retractile signaling pathway. Blood. 2009;113:893–01. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-155978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mazharian A, Roger S, Berrou E, Adam F, Kauskot A, Nurden P, Jandrot-Perrus M, Bryckaert M. Protease-activating receptor-4 induces full platelet spreading on a fibrinogen matrix: involvement of ERK2 and p38 and Ca2+ mobilization. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:5478–87. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609881200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garcia E, Stracher A, Jay D. Calcineurin dephosphorylates the C-terminal region of filamin in an important regulatory site: a possible mechanism for filamin mobilization and cell signaling. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2006;446:140–50. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2005.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakamura F, Stossel TP, Hartwig JH. The filamins: organizers of cell structure and function. Cell Adh Migr. 2011;5:160–9. doi: 10.4161/cam.5.2.14401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Legate KR, Fassler R. Mechanisms that regulate adaptor binding to β-integrin cytoplasmic tails. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:187–98. doi: 10.1242/jcs.041624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pfaff M, Liu S, Erle DJ, Ginsberg MH. Integrin β cytoplasmic domains differentially bind to cytoskeletal proteins. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:6104–09. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.11.6104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Calderwood DA, Huttenlocher A, Kiosses WB, Rose DM, Woodside DG, Schwartz MA, Ginsberg MH. Increased filamin binding to β-integrin cytoplasmic domains inhibits cell migration. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:1060–68. doi: 10.1038/ncb1201-1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grace AA, Barradas MA, Mikhailidis DP, Jeremy JY, Moorhead JF, Sweny P, Dandona P. Cyclosporine A enhances platelet aggregation. Kidney Int. 1987;32:889–95. doi: 10.1038/ki.1987.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fernandes JB, Naik UP, Markell MS, Kornecki E. Comparative investigation of the effects of the immunosuppressants cyclosporine A, cyclosporine G, and FK-506 on platelet activation. Cell Mol Biol Res. 1993;39:265–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tomasiak M, Rusak T, Gacko M, Stelmach H. Cyclosporine enhances platelet procoagulant activity. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22:1750–56. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Su Z, Xin S, Li J, Guo J, Long X, Cheng J, Wei Q. A new function for the calcineurin β subunit: antiplatelet aggregation and anticoagulation. IUBMB Life. 2011;63:1037–44. doi: 10.1002/iub.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gooch JL, Toro JJ, Guler RL, Barnes JL. Calcineurin A-α but not A-β is required for normal kidney development and function. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:1755–65. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63430-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Graef IA, Chen F, Chen L, Kuo A, Crabtree GR. Signals transduced by Ca(2+)/calcineurin and NFATc3/c4 pattern the developing vasculature. Cell. 2001;105:863–75. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00396-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosado JA, Pariente JA, Salido GM, Redondo PC. SERCA2b activity is regulated by cyclophilins in human platelets. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:419–25. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.194530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lim HW, New L, Han J, Molkentin JD. Calcineurin enhances MAPK phosphatase-1 expression and p38 MAPK inactivation in cardiac myocytes. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:15913–19. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100452200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berrou E, Adam F, Lebret M, Fergelot P, Kauskot A, Coupry I, Jandrot-Perrus M, Nurden A, Favier R, Rosa JP, Goizet C, Nurden P, Bryckaert M. Heterogeneity of platelet functional alterations in patients with filamin A mutations. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013;33:e11–e18. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen M, Stracher A. In situ phosphorylation of platelet actin-binding protein by cAMP-dependent protein kinase stabilizes it against proteolysis by calpain. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:14282–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jay D, Garcia EJ, de IL. In situ determination of a PKA phosphorylation site in the C-terminal region of filamin. Mol Cell Biochem. 2004;260:49–53. doi: 10.1023/b:mcbi.0000026052.76418.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen HS, Kolahi KS, Mofrad MR. Phosphorylation facilitates the integrin binding of filamin under force. Biophys J. 2009;97:3095–104. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.08.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vadlamudi RK, Li F, Adam L, Nguyen D, Ohta Y, Stossel TP, Kumar R. Filamin is essential in actin cytoskeletal assembly mediated by p21-activated kinase 1. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:681–90. doi: 10.1038/ncb838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gao J, Zoller KE, Ginsberg MH, Brugge JS, Shattil SJ. Regulation of the pp72syk protein tyrosine kinase by platelet integrin αIIbβ3. EMBO J. 1997;16:6414–25. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.21.6414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.