Abstract

Since its introduction to neurosurgery in 2008, laser ablative techniques have been largely confined to the management of unresectable tumors. Application of this technology for the management of focal epilepsy in the adult population has not been fully explored. Given that nearly 1,000,000 Americans live with medically refractory epilepsy and current surgical techniques only address a fraction of epileptic pathologies, additional therapeutic options are needed. We report the successful treatment of dominant insular epilepsy in a 53 year-old male with minimally-invasive laser ablation complicated by mild verbal and memory deficits. We also report neuropsychological test data on this patient before surgery and at 8-months after the ablation procedure. This account represents the first reported successful patient outcome of laser ablation as an effective treatment option for medically refractory post-stroke epilepsy in an adult.

Keywords: Laser ablation, dominant hemisphere, insula, medically refractory epilepsy, minimally invasive surgery, laser interstitial thermal therapy

Introduction

Since its introduction to neurosurgery in 2008, laser ablative techniques have been largely confined to the management of unresectable tumors. Recently, there have been two reports of the successful use of laser ablation of epileptogenic foci in children[1,2]. There have been few reports of this technology's application to the management of focal epilepsy in the adult population. Given that nearly 1,000,000 Americans live with medically refractory epilepsy and current surgical techniques only address a subset of this population's epileptic pathologies, additional therapeutic options are needed. We report the successful treatment of dominant insular post-stroke epilepsy in a 53 year-old male. This account represents the first reported successful patient outcome of laser ablation as an effective treatment option for medically refractory post-stroke epilepsy in an adult.

Case Report

History & Physical Examination

Our patient is a 53 year old right handed obese gentleman with a 10 year history of complex partial epilepsy. He and his wife described his seizures as episodes involving a metallic taste in his mouth followed by a sigh breath and a tendency to put objects in his mouth lasting 20-40 seconds. When he tried to speak during these events his speech was unintelligible. He typically maintained at least partial memory for these events. He suffered a mild traumatic brain approximately 12 years previously, but there was no evidence this contributed towards his epilepsy. There was no clinically-evident identifiable source for or event causing his adult onset epilepsy. He remained refractory despite three anti-epileptic medications (carbamazepine, topiramate and lacosamide). He experienced multiple seizures weekly and had recently begun to develop a chronic, progressive encephalopathy over three months prior to presentation including forgetfulness and loss of some of his higher cognitive capabilities. He had no neurological deficits on physical examination.

Pre-surgical Neuropsychological Assessment

The patient underwent neuropsychological assessment approximately seven months before the ablation procedure. At that time, the patient reported poor concentration, word retrieval problems and slowed processing speed. His wife believed he was depressed. He reported that he completed thirteen years of education, but repeated the third grade and struggled with reading. He previously worked as a chemical operator, but later became disabled.

His IQ was estimated to be within the low average range. He displayed a severe deficit in executive functions (characterized by deficient divided attention and perseveration) and a moderate deficit in language (reduced letter fluency, naming, and listening comprehension). Milder deficits were also noted in verbal anterograde memory and visual learning. Cognitive test results were consistent with left greater than right cerebral hemisphere dysfunction. Emotionally, he endorsed severe levels of depression and anxiety and psychiatric follow up was recommended (Table 1).

Table 1. Results of Pre- & Post-operative Neuropsychological Evaluations.

| Test | Pre-operative T-Score | Post-operative T-Score |

|---|---|---|

| Wechsler Test of Adult Reading (Standard Score) | 83 | 81 |

| DKEFS Letter Fluency | 23 | 20 |

| DKEFS Category Fluency | 37 | 20 |

| DKEFS Category Switching-Total | 20 | 23 |

| DKEFS Category Switching-Accuracy | 23 | 27 |

| MAE Token Test | 45 | <30 |

| BDAE Complex Ideational Material | 15 | 34 |

| BDAE Boston Naming Test-II | 34 | 30 |

| Rey-Osterrich Complex Figure | ||

| Copy | 37 | 51 |

| Delayed Recall | 43 | 52 |

| Benton Judgment of Line Orientation | 55 | 47 |

| WASI Block Design | 41 | 43 |

| WASI Similarities | 37 | 21 |

| WMS-IV Logical Memory I | 40 | 37 |

| WMS-IV Logical Memory II | 33 | 27 |

| WMS-IV Visual Reproduction I | 46 | 53 |

| WMS-IV Visual Reproduction II | 36 | 40 |

| CVLT-II Total Trials 1-5 | 47 | 36 |

| CVLT-II Short Delay-Free Recall | 40 | 35 |

| CVLT-II Short Delay-Cued Recall | 40 | 30 |

| CVLT-II Long Delay-Free Recall | 50 | 35 |

| CVLT-II Long Delay-Cued Recall | 45 | 30 |

| CVLT-II Recognition | 45 | 55 |

| CVLT-II False Positives | 45 | <20 |

| WCST Cards Sorted | 128 | 64 |

| WCST Categories Completed | 3 (raw score) | 3 (raw score) |

| WCST Perseverative Errors | 27 | 37 |

| DKEFS Visual Scanning | 43 | 43 |

| DKEFS Number Sequencing | 57 | 30 |

| DKEFS Letter Sequencing | 57 | 33 |

| DKEFS Number-Letter Switching | 23 | 20 |

| DKEFS Motor Speed | 50 | 20 |

| Beck Depression Inventory-II | 32 (severe) | 28 (moderate) |

| State-Trait Anxiety Inventory | ||

| State | 47 (mild) | 53 (moderate) |

| Trait | 66 (severe) | 50 (moderate) |

DKEFS = Delis Kaplan Executive Function Systems; BDAE = Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination; WASI = Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence; WMS-IV = Wechsler Memory Test-IV Edition; CVLT-II = California Verbal Learning Test-2nd Edition; WCST = Wisconsin Card Sorting Test

Imaging

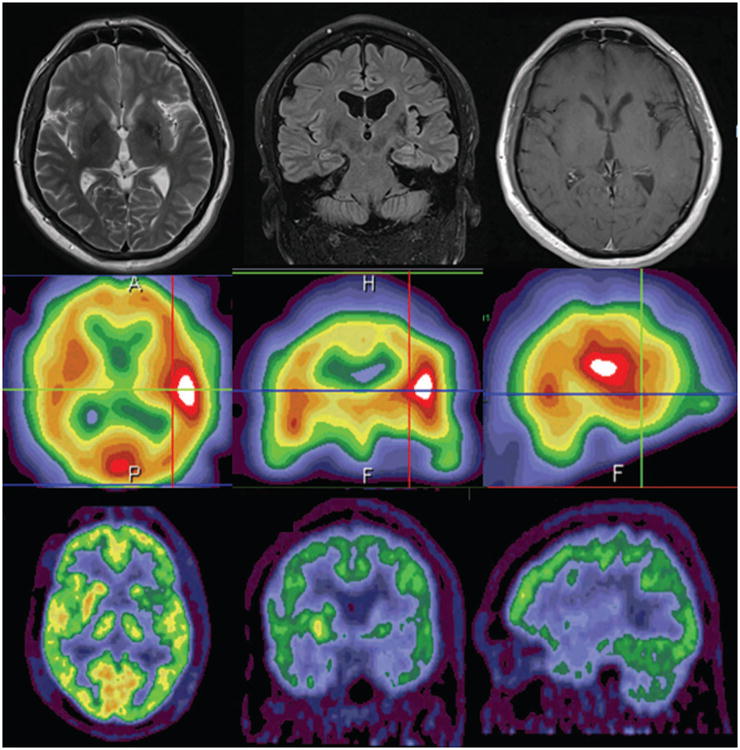

An MRI performed with seizure protocol revealed a loss of architecture in the left hippocampal head and body as well as increased FLAIR signal throughout the left hippocampus. MRI also revealed a region of encephalomalacia with gliosis at the junction of the left frontal and temporal opercula within the frontal insular region suggesting a previous subclinical ischemic insult (Figure 1). The insular abnormality was subcortical and spanned throughout the posterior short, anterior long, and posterior long insular gyri. This region of encephalomalacia was thought to be a potential source for his seizures.

Figure 1.

Preoperative MRI (top), PET (middle) and SPECT (bottom) demonstrating left insular encephalomalacia and associated hypometabolism.

Further Evaluation, Invasive Monitoring & Decision Making

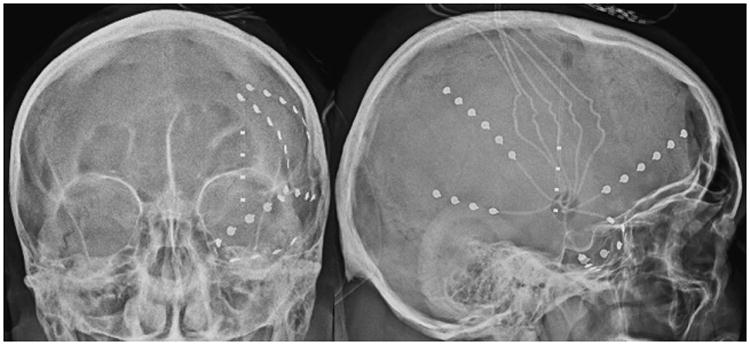

Video EEG revealed rare inter-ictal right temporal sharp waves, left hemispheric slowing, and seven seizures with left hemispheric onset and evolution. An ictal SPECT identified a left fronto-insular focus. PET scan demonstrated hypometabolism in the left insula (Figure 1). Taken together, MRI, EEG and PET data suggested that the seizures were either originating from the left insula or left temporal lobe. The patient was discussed in a multi-disciplinary epilepsy conference and was deemed to be a candidate for surgical intervention. The patient was offered invasive electrocorticography for seizure monitoring with plans for tailored management of the epilepsy focus. After a multidisciplinary conference, it was felt that a single 4-contact insular depth electrode and several frontal, parietal and temporal strips would provide sufficient information to localize the seizures. Hence, multiple subdural subtemporal and frontotemporal strips and a left insular depth electrode were placed. The depth electrode trajectory was from a frontal burr hole and multiple subdural electrodes were placed via a single middle-cranial fossa burr hole (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Skull X-Rays showing invasive monitoring electrodes. Anterior-Posterior (left) and lateral (right) images show subdural electrocorticography strips placed through a single middle cranial fossa burr hole and a single multi-contact depth electrode placed with frameless stereotactic navigation through a frontal burr hole.

Video invasive monitoring for one week revealed the patient had complex partial seizures with left insular onset. This conclusion was based on recording (1) five typical clinical and electrographic seizures with left depth electrode onset and evolution followed by left frontal and temporal propagation, (2) frequent depth electrode epileptiform discharges, and (3) intermittent depth electrode slowing. Monitoring was notable for a predominance of intermittent theta and delta activity and frequent sharp waves throughout the depth electrodes. There were also sharp waves observed in a subdural electrodes over the left posterior frontal region. Seizure semiology was characterized by behavioral arrest, staring with inattention, mild mouth movements or vocalization and automatisms. Electrographically, the seizures were stereotypical: initial periodic sharp waves in a depth electrode were followed by rhythmic theta or delta spike-wave complexes that were propagated into the left posterior -frontal and anterior-frontal subdural electrodes with sharply contoured theta activity. Later regions of the propagation included anterior-temporal regions. Seizures then evolved to rhythmic sharply contoured theta activity over broad distributions of intracranial electrodes. Following invasive monitoring, the seizures were therefore localized to the left insula.

The patient was offered Monteris laser ablation of his left frontal insular seizure focus. Minimally invasive ablation under general anesthesia was ultimately favored over other surgical options for several reasons. First, the target was in a difficult-to-access subcortical location which would require a large awake surgery and resection of a broad region of insular cortex and subcortical tissue. The patient had several anesthesia-related contraindications for awake surgery such as excessive patient anxiety, obesity, and obesity-related upper airway management concerns.[3-5]

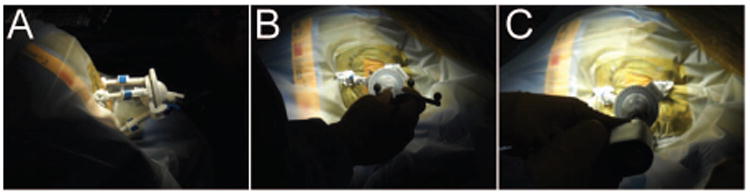

Ablative Procedure

The patient was brought back to the operating room approximately one week following electrode placement for invasive monitoring. He was placed supine with his head fixed in an MRI compatible Mayfield cranial fixation device (Integra Life Sciences, Plainsboro NJ, USA). All monitoring electrodes were removed and a preoperative MRI was obtained for targeting purposes. Following completion of this MRI, operative planning with the Monteris NeuroBlate System commenced (Monteris Medical, Plymouth MN, USA). Two insular targets were selected, one located in the anterior and one in the posterior portion of the insula. A 2 cm linear incision was made in the patient's frontal scalp to allow for burr hole placement. A 2.2 mm central cannula was used to allow the passage of the laser probe. The Monteris AXiiiS Stereotactic Mini-Frame was affixed to the skull (Figure 3A) and the Stealth Navigus probe (Medtronic Inc., Minneapolis MN, USA) was inserted into the AXiiiS mini-frame (Figure 3B). The trajectory and depth for the Monteris probe were defined by the Monteris VizApp software. Both ablation trajectories were selected via the single access burr hole (Figure 3C). The probe was inserted via trajectories from the apex of the skull, and the ablation of the posterior portion of the defined seizure focus was delivered following confirmation of probe placement (Figure 4). The rotational component of the affixed AXiiiS mini-frame was mobilized anteriorly via the Navigus probe and the Monteris laser probe was inserted to the pre-selected depth target. Intraoperative thermal dosage lines and thermometry data confirmed successful laser ablation of the anterior portion of the insular encephalomalacia was completed (Figure 5). Intraoperative temperatures to achieve apoptosis and necrosis were 45°C and 52°C, respectively.[6] The treatment target measured 5.8 cm3. Eighty-seven percent and 81% of the target reached 45°C and 52°C, respectively.

Figure 3.

Targeting lesion for LITT. (A) AXiiiS mini-frame is mounted to the skull and (B) intraoperative navigation probe aligned through AXiiis mini-frame. (C) A burr hole is drilled for probe placement.

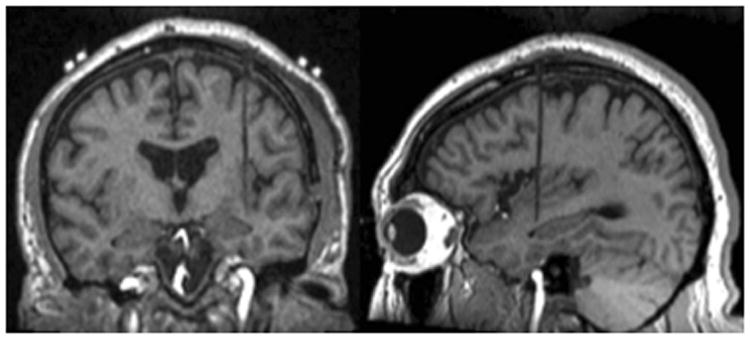

Figure 4.

Pre-ablation intraoperative MRI confirming laser probe location within the left insular target location on coronal (left) and sagittal (right) T1-weighted images.

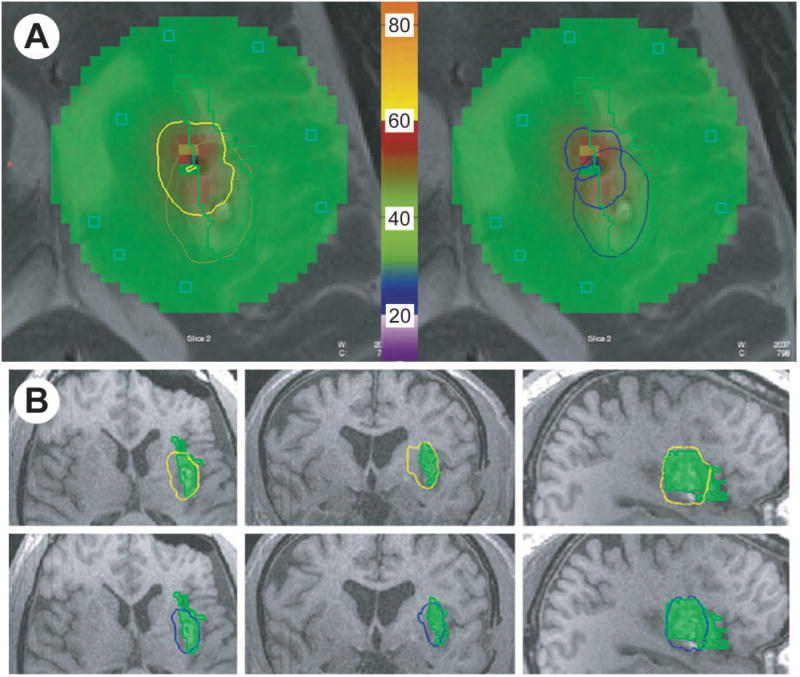

Figure 5.

Intraoperative thermometry and thermal dosage lines (TDL) for ablation of epilepsy focus. (A) Intraoperative thermometry and TDL are shown for 45 °C dose (left) and 52 °C dose (right). Green area indicates thermometry monitoring zone and green line encompasses the target. Bold yellow line indicates 2nd trajectory 45 °C TDL and light yellow line indicates 1st trajectory 45 °C TDL. Bold blue line indicates 2nd trajectory 52 °C TDL and light blue line indicates 1st trajectory 52 °C TDL. Regions of color within the treatment zone represent thermometry recording illustrated within. Thermometry reference bar with °C is shown in center. (B) Cumulative TDLs are shown relative to target lesion (green) in axial, coronal and sagittal planes for 45 °C TDL (yellow) and 52 °C TDL (blue).

Post-operative Course

The patient was monitored in the Neurosurgical Intensive Care Unit overnight following the ablative procedure. Post-procedurally, seizures abated immediately. The patient was mildly emotionally labile and had new mild speech and memory difficulties requiring cognitive rehabilitation. He was discharged 4 days later without event. On short-interval follow up, the patient displayed mild and easily manageable verbal and memory symptoms. He had no cranial neuropathies, motor deficits or sensory deficits. He ambulated well with a normal gait. His speech was fluent but intermittently hypophonic. He occasionally repeated himself and made rare paraphasic errors. Impairment in verbal memory improved steadily over time. Transient anxiety and mood alterations returned to baseline levels after approximately 6-8 weeks. The patient has been seizure free since the time of surgery 23 months ago.

Post-operative imaging changes

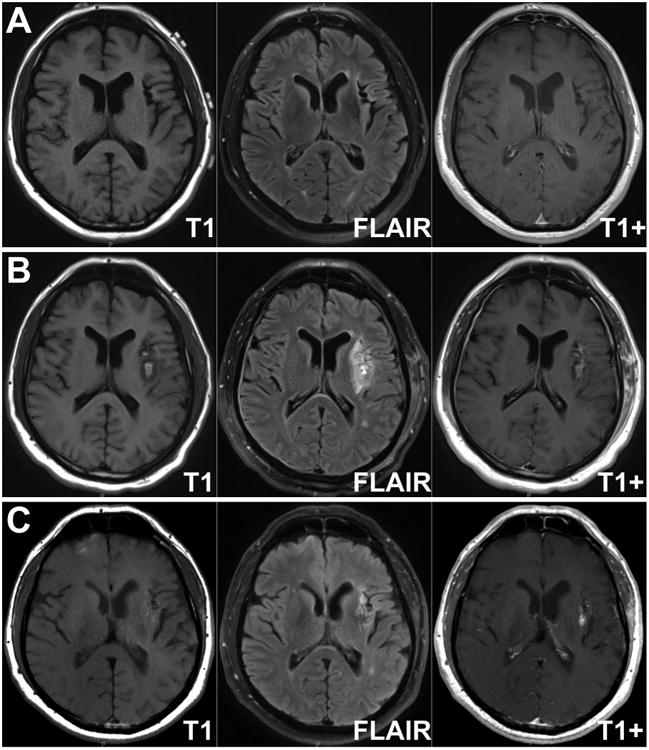

Post-operative MRI sequences were obtained one day and 5 months postoperatively. Compared with a preoperative MRI, the 1-day postoperative MRI shows a hyperintensity in the insular target on T1-weigted images. This corresponds to artifact on susceptibility-weighted imaging sequences and represents coagulation blood products. This region corresponds to high intensity on T2-weighted MRI, surrounded by peri-lesional edema. T1-weighted images with gadolinium contrast show some new enhancement suggesting breakdown of blood brain barrier (Figure 6). Although postoperative enhancement can be seen, MRI sequences 5 months postoperatively may show persistent enhancement due to blood brain barrier disruption, which may enhance delivery of anti-epileptic medications.

Figure 6.

Radiographic effects of laser interstitial thermal ablation of left insular epilepsy focus. Axial T1-weighted, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) and T1-weighted with gadolinium MRI images are shown preoperatively (A), 1 day postoperatively (B) and 5-months post-operatively (C).

Post-operative Neuropsychological Assessment

The patient underwent repeat neuropsychological assessment approximately eight months after the ablation. He and his wife reported declines in both his short-term memory and processing speed since surgery. He reported that he felt more depressed transiently following surgery, but that his mood had improved in recent months. Declines in the patient's cognition were pre-determined to be significant if he scored at least one standard deviation lower post-operatively than he scored during his pre-operative assessment. Therefore, compared to his pre-operative neuropsychological assessment, the patient displayed declines on numerous verbal measures including category fluency, listening comprehension, verbal anterograde memory and verbal abstraction (Table 1). Stable performance was noted on measures assessing spatial abilities, visual memory, and executive functions. His mood remained depressed and anxious but not as severely as before surgery.

Discussion

Approximately 1 million Americans are living with medically refractory epilepsy[7]. Up to 300,000 of these individuals could benefit from surgical intervention for the management of their epilepsy with clinical improvements enjoyed in a variety of realms including seizure freedom[8], improved return to work/school rates[9,10], overall improved quality of life [10-13], improved life expectancy[9], among others. While surgery for epilepsy is well tolerated overall, the prospect of open craniotomy discourages both patient referrals and patient willingness to consider surgery [14-16]. Additionally, some patients with discrete, well-defined seizure foci may not be a candidate for resection due to anatomical location of their lesion, as is the case in our patient.

Laser ablative technology is a relatively new treatment modality for deep tumors that would otherwise not be amenable to surgical resection. The technology capitalizes on the readily available stereotactic navigation that can be used to localize deep tumors for biopsy. Building on this navigation technology, laser ablation goes one step further and delivers thermal energy under real-time MRI guidance to a surgical target for therapeutic purposes. It was originally conceived of as a treatment for otherwise inoperable tumors. The laser's ablative effect is believed to be multi-factorial including local tissue damage from thermal energy, protein denaturation, and potentially a breakdown of the blood brain barrier to enhance therapeutic effects of post-operatively delivered chemotherapeutic agents [6,17-22]. Although speculative, it is intriguing that there was persistent enhancement in the treatment zone of this case, suggesting that the blood brain barrier may be permanently disrupted. This could in part facilitate higher dosage concentration of systemic antiepileptic drugs to an epileptogenic region.

Laser ablation has been employed to treat a variety of targets including tumors and radiation necrosis as well as hippocampal sclerosis and other epilepsy targets.[6,17-21,23-33] Initial reports suggest a potential role for laser therapy in the treatment of epilepsy. Curry et al. performed laser ablation of 5 patients with a variety of epilepsy targets and all patients remained seizure free as of 2-13 month follow up. [27] Mesial temporal lobe laser ablation in 13 patients by Willie et al. led to seizure freedom in 7 patients and worthwhile improvement in 3 patients. [33] Ablation of an insular seizure focus in this report led to seizure freedom at 23 month follow up. In addition to showing clinical effectiveness in several studies, laser ablation of intracranial targets carries several advantages to overcome limitations of open surgery. First, deeply located seizure foci or seizure foci located within eloquent cortex would be amenable to laser ablative technologies preferentially over surgical resection. Second, the minimally invasive nature of the procedure may address concerns on the part of patients or referring physicians who would be otherwise hesitant to accept surgery as a viable treatment option. Finally, laser ablation may reduce hospital and intensive care unit durations and reduce costs.[28] Despite its promise as a viable therapeutic, laser ablation also carries risks of complications. Willie et al. reported a homonymous hemianopia, emergency room visit and an asymptomatic subdural hematoma.[33] Others have reported complications similar to those observed with traditional craniotomies including neurological deficits, hyponatremia, infection, deep vein thrombosis and death.[28] This patient showed decline on several verbal measures at the time of the post-operative neuropsychological assessment approximately eight months post-surgery, however, which is consistent with cognitive changes observed in individuals with dominant hemisphere epilepsy who undergo more traditional resective surgery [34-36]. Therefore, caution must be emphasized for any surgery in the dominant insula. It is recommended that patients are counseled about the possible cognitive declines they might experience even when using laser ablative techniques.

Conclusions

Laser ablation therapy offers a minimally-invasive option for select epilepsy patients. Additional studies are warranted to better understand the mechanism of action of both the neurocognitive and anti-epileptic effects of this treatment option.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge grant funding from the Epilepsy Foundation (S.K.B.) and the National Institute of Health (5T32NS007205-32, A.H.H.).

Abbreviations

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- FLAIR

fluid attenuated inversion recovery

- EEG

electroencephalogram

- PET

positron emission tomography

- SPECT

single photon emission computed tomography

- cm

centimeters

- mm

millimeters

- DKEFS

Delis Kaplan Executive Function Systems

- BDAE

Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination

- WASI

Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence

- WMS-IV

Wechsler Memory Test-IV Edition

- CVLT-II

California Verbal Learning Test-2nd Edition

- WCST

Wisconsin Card Sorting Test

Footnotes

Disclosures: Dr. Eric Leuthardt has a consulting relationship with Monteris Medical. There are no other disclosures to report.

References

- 1.Curry DJ, Gowda A, McNichols RJ, Wilfong AA. Mr-guided stereotactic laser ablation of epileptogenic foci in children. Epilepsy Behav. 2012;24:408–414. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2012.04.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tovar-Spinoza Z, Carter D, Ferrone D, Eksioglu Y, Huckins S. The use of mri-guided laser-induced thermal ablation for epilepsy. Childs Nerv Syst. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s00381-013-2169-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berkenstadt H, Perel A, Hadani M, Unofrievich I, Ram Z. Monitored anesthesia care using remifentanil and propofol for awake craniotomy. Journal of neurosurgical anesthesiology. 2001;13:246–249. doi: 10.1097/00008506-200107000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Skucas AP, Artru AA. Anesthetic complications of awake craniotomies for epilepsy surgery. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2006;102:882–887. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000196721.49780.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zoppellari R, Ferri E, Pellegrini M. Anesthesiologic management for awake craniotomy. In: Signorelli F, editor. Explicative cases of controversial issues in neurosurgery. Rijeka, Croatia: Intech; 2012. pp. 19–34. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hawasli AH, Ray WZ, Murphy RK, Dacey RG, Jr, Leuthardt EC. Magnetic resonance imaging-guided focused laser interstitial thermal therapy for subinsular metastatic adenocarcinoma: Technical case report. Neurosurgery. 2012;70:332–337. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e318232fc90. discussion 338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hauser WA. The natural history of drug resistant epilepsy: Epidemiologic considerations. Epilepsy Res Suppl. 1992;5:25–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wiebe S, Blume WT, Girvin JP, Eliasziw M. A randomized, controlled trial of surgery for temporal-lobe epilepsy. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:311–318. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200108023450501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sperling MR. The consequences of uncontrolled epilepsy. CNS Spectr. 2004;9:98–101. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900008464. 106-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elliott I, Kadis DS, Lach L, Olds J, McCleary L, Whiting S, Snyder T, Smith ML. Quality of life in young adults who underwent resective surgery for epilepsy in childhood. Epilepsia. 2012;53:1577–1586. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2012.03594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schramm J, Delev D, Wagner J, Elger CE, von Lehe M. Seizure outcome, functional outcome, and quality of life after hemispherectomy in adults. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2012;154:1603–1612. doi: 10.1007/s00701-012-1408-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mohammed HS, Kaufman CB, Limbrick DD, Steger-May K, Grubb RL, Jr, Rothman SM, Weisenberg JL, Munro R, Smyth MD. Impact of epilepsy surgery on seizure control and quality of life: A 26-year follow-up study. Epilepsia. 2012;53:712–720. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.03398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Titus JB, Lee A, Kasasbeh A, Thio LL, Stephenson J, Steger-May K, Limbrick DD, Jr, Smyth MD. Health-related quality of life before and after pediatric epilepsy surgery: The influence of seizure outcome on changes in physical functioning and social functioning. Epilepsy Behav. 2013;27:477–483. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2013.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Erba G, Messina P, Pupillo E, Beghi E. Acceptance of epilepsy surgery among adults with epilepsy--what do patients think? Epilepsy Behav. 2012;24:352–358. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2012.04.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Erba G, Moja L, Beghi E, Messina P, Pupillo E. Barriers toward epilepsy surgery. A survey among practicing neurologists. Epilepsia. 2012;53:35–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.03282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hakimi AS, Spanaki MV, Schuh LA, Smith BJ, Schultz L. A survey of neurologists' views on epilepsy surgery and medically refractory epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2008;13:96–101. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anzai Y, Lufkin R, DeSalles A, Hamilton DR, Farahani K, Black KL. Preliminary experience with mr-guided thermal ablation of brain tumors. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1995;16:39–48. discussion 49-52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jethwa PR, Barrese JC, Gowda A, Shetty A, Danish SF. Magnetic resonance thermometry-guided laser-induced thermal therapy for intracranial neoplasms: Initial experience. Neurosurgery. 2012;71:133–144. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e31826101d4. 144-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kahn T, Bettag M, Ulrich F, Schwarzmaier HJ, Schober R, Furst G, Modder U. Mri-guided laser-induced interstitial thermotherapy of cerebral neoplasms. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1994;18:519–532. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199407000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leonardi MA, Lumenta CB. Stereotactic guided laser-induced interstitial thermotherapy (slitt) in gliomas with intraoperative morphologic monitoring in an open mr: Clinical expierence. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 2002;45:201–207. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-36203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rahmathulla G, Recinos PF, Valerio JE, Chao S, Barnett GH. Laser interstitial thermal therapy for focal cerebral radiation necrosis: A case report and literature review. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2012;90:192–200. doi: 10.1159/000338251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sloan AE, Ahluwalia MS, Valerio-Pascua J, Manjila S, Torchia MG, Jones SE, Sunshine JL, Phillips M, Griswold MA, Clampitt M, Brewer C, Jochum J, McGraw MV, Diorio D, Ditz G, Barnett GH. Results of the neuroblate system first-in-humans phase i clinical trial for recurrent glioblastoma clinical article. Journal of Neurosurgery. 2013;118:1202–1219. doi: 10.3171/2013.1.JNS1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bettag M, Ulrich F, Schober R, Furst G, Langen KJ, Sabel M, Kiwit JC. Stereotactic laser therapy in cerebral gliomas. Acta Neurochir Suppl (Wien) 1991;52:81–83. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-9160-6_23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carpentier A, Chauvet D, Reina V, Beccaria K, Leclerq D, McNichols RJ, Gowda A, Cornu P, Delattre JY. Mr-guided laser-induced thermal therapy (litt) for recurrent glioblastomas. Lasers Surg Med. 2012;44:361–368. doi: 10.1002/lsm.22025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carpentier A, McNichols RJ, Stafford RJ, Guichard JP, Reizine D, Delaloge S, Vicaut E, Payen D, Gowda A, George B. Laser thermal therapy: Real-time mri-guided and computer-controlled procedures for metastatic brain tumors. Lasers Surg Med. 2011;43:943–950. doi: 10.1002/lsm.21138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carpentier A, McNichols RJ, Stafford RJ, Itzcovitz J, Guichard JP, Reizine D, Delaloge S, Vicaut E, Payen D, Gowda A, George B. Real-time magnetic resonance-guided laser thermal therapy for focal metastatic brain tumors. Neurosurgery. 2008;63:ONS21–28. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000335007.07381.df. discussion ONS28-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Curry DJ, Gowda A, McNichols RJ, Wilfong AA. Mr-guided stereotactic laser ablation of epileptogenic foci in children. Epilepsy Behav. 2012;24:408–414. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2012.04.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hawasli AH, Bagade S, Shimony JS, Miller-Thomas M, Leuthardt EC. Magnetic resonance imaging-guided focused laser interstitial thermal therapy for intracranial lesions: Single-institution series. Neurosurgery. 2013;73:1007–1017. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0000000000000144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mohammadi AM, Hawasli AH, Rodriguez A, Schroeder JL, Laxton AW, Elson P, Tatter SB, Barnett GH, Leuthardt EC. The role of laser interstitial thermal therapy in enhancing progression-free survival of difficult-to-access high-grade gliomas: A multicenter study. Cancer medicine. 2014 doi: 10.1002/cam4.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schwarzmaier HJ, Eickmeyer F, von Tempelhoff W, Fiedler VU, Niehoff H, Ulrich SD, Ulrich F. Mr-guided laser irradiation of recurrent glioblastomas. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2005;22:799–803. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schwarzmaier HJ, Eickmeyer F, von Tempelhoff W, Fiedler VU, Niehoff H, Ulrich SD, Yang Q, Ulrich F. Mr-guided laser-induced interstitial thermotherapy of recurrent glioblastoma multiforme: Preliminary results in 16 patients. Eur J Radiol. 2006;59:208–215. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2006.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sloan AE, Ahluwalia MS, Valerio-Pascua J, Manjila S, Torchia MG, Jones SE, Sunshine JL, Phillips M, Griswold MA, Clampitt M, Brewer C, Jochum J, McGraw MV, Diorio D, Ditz G, Barnett GH. Results of the neuroblate system first-in-humans phase i clinical trial for recurrent glioblastoma. J Neurosurg. 2013;118:1202–1219. doi: 10.3171/2013.1.JNS1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Willie JT, Laxpati NG, Drane DL, Gowda A, Appin C, Hao C, Brat DJ, Helmers SL, Saindane A, Nour SG, Gross RE. Real-time magnetic resonance-guided stereotactic laser amygdalohippocampotomy for mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurosurgery. 2014;74:569–585. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0000000000000343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bandt SK, Werner N, Dines J, Rashid S, Eisenman LN, Hogan RE, Leuthardt EC, Dowling J. Trans-middle temporal gyrus selective amygdalohippocampectomy for medically intractable mesial temporal lobe epilepsy in adults: Seizure response rates, complications, and neuropsychological outcomes. Epilepsy Behav. 2013;28:17–21. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2013.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Helmstaedter C. Neuropsychological aspects of epilepsy surgery. Epilepsy Behav. 2004;5(Suppl 1):S45–55. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2003.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sherman EM, Wiebe S, Fay-McClymont TB, Tellez-Zenteno J, Metcalfe A, Hernandez-Ronquillo L, Hader WJ, Jette N. Neuropsychological outcomes after epilepsy surgery: Systematic review and pooled estimates. Epilepsia. 2011;52:857–869. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.03022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]