Abstract

Objective

There is evidence linking the built environment (BE) with physical activity (PA), but few studies have been conducted in Latin America (LA). State-of-the-art methods and protocols have been designed in and applied in high-income countries (HIC). In this paper we identify key challenges and potential solutions to conducting high quality PA and BE research in LA.

Methods

The experience of implementing the IPEN data collection protocol (IPEN: International Physical Activity Environment Network) in Curitiba, Brazil; Bogotá, Colombia; and Cuernavaca, Mexico (2010-2011); is described to identify challenges for conducting PA and BE research in LA.

Results

Five challenges were identified: Lack of academic capacity (implemented solutions (IS): building a strong international collaborative network); limited data availability, access and quality (IS: partnering with influential local institutions, and crafting creative solutions to use the best-available data); socio-political, socio-cultural and socio-economic context (IS: in-person recruitment and data collection, alternative incentives); safety (IS: strict rules for data collection procedures, and specific measures to increase trust); appropriateness of instruments and measures (IS: survey adaptation, use of standardized additional survey components, and employing a context-based approach to understanding the relationship between PA and the BE). Advantages of conducting PA and BE research in LA were also identified.

Conclusions

Conducting high quality PA and BE research in LA is challenging but feasible. Networks of institutions and researchers from both HIC and LMIC play a key role. The lessons learnt from the IPEN LA study may be applicable to other LMIC.

Keywords: Physical activity, built environment, Latin America

Introduction

Latin America (LA) has fascinated and intrigued people since the first European conquerors arrived in the late 1400s (Bakewell, 2004). It's combination of complex indigenous societies and abundant natural resources attracted several waves of immigration from Europe (Bakewell, 2004, Lockhart, 1983). The term “Latin America” expresses the strong influences from Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, and French cultures (Bakewell, 2004, Lockhart, 1983). However, this idyllic vision of the past contrasts with LA's current health, social and economic reality (Furtado, 1976).

Demographic and epidemiologic transition in LA

Over the past decades, LA has experienced accelerated demographic and epidemiological transitions, and many countries are facing a double burden of disease, characterized by the coexistence of communicable and non-communicable diseases (NCDs) among the population (Barreto et al., 2012). LA's aging population has grown, pushing up rates of NCDs risk factors and the prevalence of NCDs in the region. Obesity and physical inactivity are now especially important public health challenges (Barreto et al., 2012, Frenk et al., 1991, Kain et al., 2014, Rivera et al., 2002).

Urbanization, economic and social inequalities in LA

LA is the most urbanized region in the world, with nearly eight out of ten people living in cities (United Nations, 2012). LA cities tend to have high population density patterns (Knox and McCarthy, 2011), and the transition from traditional public transportation systems to private cars and motorcycles has resulted in increased traffic congestion, air pollution and traffic accidents (Becerra et al., 2013). LA has also become a region of pronounced inequalities, having the largest proportion of population in the world living in slums (United Nations, 2012), and 224 million people living in poverty (Barreto et al., 2012), as well as increasingly high crime rates (Ayres, 1998, Soares and Naritomi, 2010).

PA and the built environment (BE)

While there is substantial evidence linking the BE with PA from high-income countries (HIC) (Bauman et al., 2012, Sallis et al., 2012, Saelens and Handy, 2008, Saelens et al., 2012), few reports come from LA or other LMIC (Bauman et al., 2012, Reis et al., 2013, Parra et al., 2011, Hino et al., 2013, Salvo et al., 2014a). Some studies suggest that the relationship between the BE and PA may be context specific, making this gap in the literature especially important (Parra et al., 2011, Hino et al., 2011, Salvo et al., 2014a, Ebrahim et al., 2013). In HIC, the walkability index, a construct incorporating residential density, street connectivity and land-use mix, has been positively associated with PA for leisure and transport (Cerin et al., 2007, Frank et al., 2010, Van Dyck et al., 2010). While findings from Brazil are consistent with those from HIC (Reis et al., 2013), in Mexico and other LMIC the walkability index, as defined for HIC, is inversely related to PA (Islam, 2009, Salvo et al., 2014a).

High quality studies on the BE and PA, allowing for the identification of context-specific relationships, are important for both research and policy, but are not easy to carry out. Most assessment methods and data collection protocols have been designed and tested in HIC, and often do not adapt well to LA urban environments and populations (Ebrahim et al., 2013, Brownson et al., 2009, Hallal et al., 2010). In 2009 we conducted a literature review to identify available tools to measure the BE as it relates to PA. Out of the ninety identified assessment tools, only six were in Spanish (the predominant language in Latin America), and they were all translations of tools designed to assess U.S. neighborhoods (National Center for Safe Routes to Schools, 2009, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 2008b, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 2008a, Partnerships for Healthy Communities, 1999, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, University of California in Los Angeles & San Francisco Dept of Public Health, 2008).

The IPEN study

IPEN is a 12-country study (Australia, Belgium, Brazil, Colombia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Hong Kong, Mexico, New Zealand, Spain, United Kingdom and United States), designed to measure the associations between PA and BE features, by conducting a pooled analysis. IPEN is the first large-scale international study employing state-of-theart, standardized protocols and instruments for sampling, data collection and analysis, thus ensuring comparability across the 12 participating countries (Kerr et al., 2013). Furthermore, IPEN is the first study in Latin America (Brazil, Colombia and Mexico) to use objective measures for both PA and the BE (accelerometry and Geographic Information Systems) in large representative samples. More information on the IPEN data collection protocol is available elsewhere (Kerr et al., 2013).

Study Aim and Approach

The aim is to document the process of adapting state-of-the-art research methods in order to conduct research in LA of the quality required for publication in first order international scientific journals. The urban environment, culture, and academic environment in LA differ substantially from those in the U.S., where IPEN was designed, funded, and piloted. Thus the investigators in Curitiba, Brazil; Bogotá, Colombia; and Cuernavaca, Mexico had to systematically assess which components of the study protocol required changes in order to be relevant for the study populations and feasible to implement. The research teams from the three IPEN-LA sites worked closely together during this process, sharing experiences, translating and adapting instruments, and in some cases jointly developing new data collection instruments and protocols. In this paper we describe the key challenges encountered by the study teams and the solutions that were developed. It is likely that other investigators in LA and in LMIC will face similar challenges and may benefit from the summary of challenges and solutions that follows.

Results

The IPEN study was successfully conducted in Brazil, Colombia and Mexico in 2010-2011 (Table 1). Five main challenges were identified by IPEN-LA investigators for conducting PA and BE research in LA. In this section, we describe each challenge, followed by the solutions implemented by IPEN-LA investigators. Additionally, some advantages of conducting this type of research in LA in comparison to HIC are described. An itemized summary of recommendations based on our findings is found in Appendix A.

Table 1.

Characteristics of IPEN Latin America study sites, process outcomes and outputs (data collection: 2010-2011)

| Brazil-Curitiba | Colombia-Bogotá | Mexico-Cuernavaca | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population Size (2010) | 1,760,000 | 7,363,000 | 365,000 |

| Institution | Pontificia Universidade Catolica do Parana | Universidad de los Andes | Instituto Nacional de Salud Publica |

| Human Development Index | 0.73 | 0.719 | 0.775 |

| GINI coefficienta | 54.7 | 55.9 | 47.2 |

| Overall Sampleb | 699 | 1000 | 679 |

| Sample with survey datab | 699 | 1000 | 679 |

| Sample with valid accelerometer datab | 254 | 250 | 674 |

| Accelerometer loss rate | 0% | 5% | 3% |

| Objective measurement of weight and height | 100% | 70% | 100% |

| Field interviewers | 17 | 21 | 7 |

| Incentives | No incentives | Umbrella and physical activity reports | Physical activity reports and grocery vouchers (value: 100 Mexican Pesos) |

| Time of data collection | 4 months | 6 months | 6 months |

| Student trainees (undergraduate and graduate students) | 9 | 5 | 2c |

| PhD Thesis | 1 | 1 | 2c |

| Master Thesis | 4 | 1 | 0 |

| Exchange students and academic visits | 1 to Colombia | 1 to Mexico and Brazil | 1 to Brazil and Colombia |

| Published papers, book chapters | 8 | 5 | 7 |

| Conference Presentations | 12 | 7 | 8 |

GINI coefficient: “Reflects the extent to which the distribution of income or consumption expenditure among individuals or households within an economy deviates from a perfectly equal distribution. A Gini index of 0 represents perfect equality; whereas an index of 100 represents perfect inequality” (World Bank Group, 2012)

The IPEN study protocol requires countries to have a final sample of at least 500 participants (at least 500 with survey data, and at least 250 with accelerometer data)(Kerr, 2013)

One student is currently completing the PhD program/Thesis

Challenge 1: Lack of academic capacity

The extensive evidence base on the health effects of physical inactivity and the BE correlates of PA comes almost entirely from HIC (Lee et al., 2012, Pratt et al., 2012, Bauman et al., 2012). PA and public health research remains a nascent field in LA and LMIC. This is demonstrated by the substantially fewer publications from LMIC for PA interventions and correlate studies (Bauman et al., 2012, Pratt et al., 2012). There is a lack of recognition of PA as a public health priority at the policy level worldwide (Bull and Bauman, 2011). Yet, in most LMIC, the lack of recognition of the importance of PA extends beyond the policy level, to academia and research. Few graduate level training programs exist in LA for PA epidemiology, behavioral science related to PA, or PA and public health (Barboza et al., 2013). As a result, there are limited numbers of researchers in LA specifically trained to address PA as a public health issue. Most researchers who do focus in this area are graduates of top academic institutions in HIC.

IPEN-LA solution

Building a strong international collaborative network

Collaborations are known to be important for advancing knowledge in any setting or field (Keusch, 2010). For IPEN-LA, building a well-connected, international collaborative network was essential. The extensive sharing of resources (intellectual and physical) was identified as a key element for building and strengthening the IPEN-LA network, leading in turn to successful implementation of the IPEN protocol in LA.

Sharing of intellectual resources included: a) experience-based knowledge (e.g., Colombia and Brazil began data collection prior to Mexico, and shared firsthand fieldwork logistics experience, challenges, and pitfalls with IPEN-Mexico researchers), b) skill-based knowledge (e.g., informal geographic information system (GIS) training through student exchanges across the network), and c) human resources (e.g., an IPEN-Colombia researcher spent one month in Mexico coordinating data collection start-up for IPEN-Mexico).

Sharing of physical and electronic resources included: a) accelerometers, b) electronic resources such as code for data analysis on open source software, templates for database management and for individualized participant reports.

A key aspect that strengthened the collaboration was having substantial in-person time investment. This was achieved through several short visits to other IPEN-LA countries for research meetings (mainly senior investigators), and longer-term exchanges (mainly graduate students). The in-person time investment served as both a means and an end. On the one hand, it helped to strengthen the IPEN-LA network, facilitating the sharing of knowledge and resources. On the other hand, the exchanges provided informal training opportunities for junior researchers, helping to compensate for the lack of formal training opportunities for PA and BE research in LA. Consequently, junior researchers were an essential component of the research teams. Their roles included data collection, fieldwork coordination, statistical analysis, GIS, accelerometer-data analysis and training, to serving as primary investigators.

Challenge 2: Data availability, access and quality

Study protocols developed in HIC to assess PA and the BE often assume that country, city or neighborhood-level data will be available, easily accessible (i.e. public access), and of acceptable quality. This is not always the case in LMIC (Sitthi-Amorn, 2002). Often, the data required by protocol do not exist in the study setting (e.g., GIS data files for pedestrian-enhanced street networks, or retail-to-floor land use data). Other times, the data is available but not accessible, due to country-specific regulations for data access, or lack of transparency and enforcement of public access policies (e.g. crime data from official sources was not provided for Cuernavaca, Mexico, since it was considered sensitive information). In addition, even when data is available, the informality of many businesses makes variables like official land-use mix inaccurate. Finally, the format, detail or quality of the data is not always comparable to that of HIC (e.g., parcel-level data vs. land-cover data for land use).

IPEN-LA solutions

Partnering with well-respected, influential institutions

Partnering with influential and well-respected local institutions was essential for overcoming data accessibility issues for IPEN-LA. The institutional partners had enough visibility and recognition, in the realms of both government and academia, to facilitate access to data, and were willing to provide institutional endorsement for the projects. These partnerships have also facilitated the dissemination of results to policy makers.

Crafting creative solutions to use the best-available data

Before discarding data because the format did not exactly match that outlined in the study protocol, creative solutions were explored. A balance between flexibility and methodological rigor was sought. Ultimately, it was determined not to sacrifice methodological rigor to the point that the data was no longer comparable to that of other countries. For IPEN-LA, working closely with the IPEN coordinating center at the University of California, San Diego was crucial. This process led to joint solutions, which at times involved modifying the definition of variables for the IPEN study at large (e.g. using proportion of land allocated to a given land-use to determine land-use mix, rather than parcel count per land-use), to achieve maximum comparability across countries. In other situations, it involved creating indices or other estimators to make the data more similar in format to that of other IPEN countries.

Challenge 3: Socio-political, socio-cultural and socio-economic context

There are certain factors inherent to conducting research of any kind in LMIC (Prayura et al., 2002). For the most part, state-of-the-art study designs and data collection protocols are developed in HIC (Brownson et al., 2009), and do not take these factors into consideration. Some of the issues identified were: a) unreliable postal services (most protocols require mailing surveys and accelerometers); b) low literacy levels (self-report tools are designed to be filled in by the participant, which is not feasible in countries with low literacy); c) strict regulations regarding the use of incentives for research (poverty levels are much higher than those of HIC and cash-incentives --even if very small--- are considered coercive and are usually not allowed by local Institutional Review Boards); d) lack of participant trust (people in LMIC, especially those residing in high income areas, are much less responsive to participating in research studies than in HIC).

IPEN-LA solutions

In-person recruitment and data collection

In-person recruitment and data collection (accelerometer delivery and recovery, and face-to-face survey administration) was necessary for IPEN-LA. Data collectors always wore proper identification (official badges) and uniform (e.g., caps or t-shirts with institutional logo) from a well-respected local academic institution, which was essential to overcome mistrust among populations not used to participating in research studies. In-person recruitment and data collection required more complex logistics and coordination than phone- or mail-based recruitment/data collection. Budgeting to cover the salary of field workers was planned before starting the study. It was important to carefully consider the number of field workers required, given the limited resources available (accelerometers, software licenses, laptops, space, etc.), the desired sample size, and the study timeline.

Alternative incentives

Alternative incentives to cash were used, including gift cards, small items (e.g., caps, umbrellas, etc.), and individualized participant reports with graphs, diagnosis of PA level, and general recommendations.

Challenge 4: Appropriateness of instruments and measures

Due to language, cultural and contextual differences, self-report measurement tools developed in HIC to assess PA and the BE are not always appropriate for LA settings (Hallal et al., 2010). For instance, only the leisure and transport PA domains of the long version of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ)(Craig et al., 2003) are recommended for use in LA (Hallal et al., 2010). The occupational and home-based PA domains substantially overestimate levels of activity in LA (Hallal et al., 2010). Other instruments used in the IPEN study, such as the Neighborhood Environment Walkability Scale-Abbreviated Version (NEWS-A)(Cerin et al., 2013), include some items that are not applicable to LA cities, while excluding the assessment of important features of LA environments (e.g., soccer fields, public plazas, multiple modes of transportation). Moreover, these instruments are not designed for in-person, interviewer-based administration.

IPEN-LA solutions

Survey adaptation

The study surveys (IPAQ, NEWS-A, etc.) were translated into Spanish (official language of Mexico, Colombia and most of LA) and Portuguese (official language of Brazil). The Mexican and Colombian versions are different, since the survey was also adapted for cultural appropriateness per country. Another adaptation was to make the survey suitable for in-person, interviewer-based administration (i.e. providing scripts and visual aids for Likert scales). Prior to data collection, the survey was pilot tested in each country (see Appendix B for surveys and Appendix A for further details on pilot testing).

Standardized additional survey components

The research teams from the three IPEN-LA countries worked together to develop additional sections for the survey, addressing specific features of LA environments that were not captured by the original surveys. Items were included to assess transport practices (e.g., multimodal transport), and the use of certain places for PA (plazas, malls, soccer courts, etc.). The wording structure, answer options, and order of each additional item were standardized for all IPEN-LA countries.

Challenge 5: Safety

Safety from crime is an important issue that requires careful consideration when adapting data collection protocols for LA. Using students for data collection is not always feasible, since some institutions do not allow it, or strongly recommend against it, to protect their students from high-risk situations. Likewise, many neighborhoods are not accessible to data collectors, either because they are deemed to be too dangerous, or, on the contrary, are gated, guarded, limited access high-income residential communities. Moreover, during recruitment, mistrust from participants is common, also due to safety concerns (i.e., disclosure of personal information is problematic, as well as wearing accelerometers which some participants believe may be GPS enabled tracking devices).

IPEN-LA solutions

Strict rules for data collection procedures

We implemented strict measures to minimize the risk of crime for data collectors, including: a) working in pairs; b) always carrying a cellular phone (providing monthly recharges of air time); c) notifying local authorities of the areas of the city where the research team would be working; d) only working during sunlight hours; e) in Cuernavaca and Bogota, students were not used as data collectors, both due to safety considerations, and because of conflicting schedules with their school hours (effective recruitment requires data collectors to work early in the mornings, after working hours, and during weekends).

Measures to increase participant trust

Given the high-crime situation (DANE, 2012, INEGI, 2013, Datafohla-CRISP, 2013) participants were often skeptical about the veracity of the study. In addition to always wearing a badge and uniform, field workers provided participants with the telephone number of the IPEN-LA coordinating offices (Pontificia Universidade Catolica do Parana in Curitiba, Universidad de los Andes in Bogotá, and the National Institute of Public Health in Mexico). It was common for participants to call to verify that they were in fact being recruited for a real research study and that it was safe to share their information with field workers. Therefore, having an official, verifiable phone number for the study, which was always answered by a live person, was important for maximizing response rates and participant trust.

Advantages of conducting PA and BE research in LA

There are some advantages of conducting PA and BE studies in LA. Although more time and effort is necessary to build a network and to train personnel, the cost of collecting data (for comparable sample sizes and time-frames) is lower than in HIC given lower wages (Costello and Zumla, 2000). Additionally, in spite of the logistic challenges posed by in-person recruitment and data collection, these practices result in greater certainty that participants understand the survey questions. In-person data collection also provides more monitoring opportunities to verify protocol compliance for accelerometer use, and serves as a platform to conduct objective assessments (e.g., weight and height) instead of relying on self-report.

Discussion

The IPEN-LA study demonstrates that context matters when studying the relationship between PA and the BE. In fact, it plays a central role for collecting reliable and comparable data. The experiences from Brazil, Colombia and Mexico also demonstrate that despite significant challenges, if thoughtful solutions are implemented, high quality PA and BE research is feasible in LA.

As the field of PA and public health continues to grow in LA and LMIC, the importance of using an integral context-based approach to research becomes increasingly apparent (Prayura et al., 2002, McQueen, 2013). The IPEN-LA experience provided valuable information supporting the use of a context-based approach not only during data collection, but also for defining basic research constructs and questions. For instance, IPEN-LA researchers hypothesized a priori that certain established constructs from HIC (e.g., the U.S.-based walkability index) were not applicable to LA cities. Initial findings from IPEN-LA show that in Mexico and Colombia the relationship between PA and the walkability index is not consistent with what has been reported for HIC (Figure 1) (Salvo et al., 2014b). Answering the important question “What does a walkable neighborhood look like in a LA city?” cannot be done by simply applying the metrics that work well in HIC.

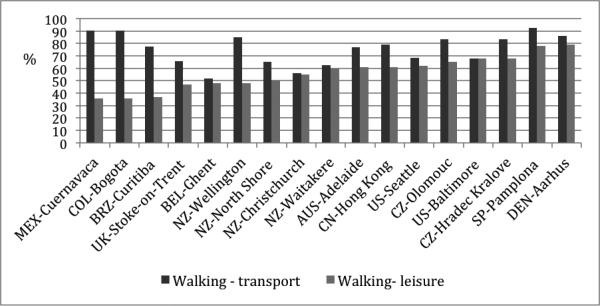

Figure 1.

Prevalence of reporting any walking for transport and any walking for leisure for the twelve participating IPEN countries (data collection: 2002 – 2011)

Figure 1 Legend: MEX=Mexico, COL=Colombia, BRZ=Brazil, UK=United Kingdom, BEL=Belgium, NZ=New Zealand, AUS=Australia, CN=China, US=United States, CZ=Czech Republic, SP=Spain, DEN=Denmark

Likewise, context should be taken into consideration when interpreting results from different cities, countries and regions. Understanding implications based on the stage of economic development of a country is key. In most LA cities, such as Bogota and Cuernavaca, car ownership remains relatively low in comparison with U.S cities (World Bank Group, 2012). In these cases, PA may be more reflective of need rather than choice, since a significant proportion of the population walks and uses public transit because they have no other option for transportation (need-based PA framework). Figure 2 shows that Bogota and Cuernavaca are among the IPEN cities with the highest prevalences of walking for transportation. On the other hand, Curitiba is among the cities in Brazil with highest car ownership (Parra et al., 2011). Yet, among all participating IPEN countries, the three LA sites have the lowest levels of PA for leisure (Figure 2). Thus, while PA in HIC may be understood within a “choice-based framework”, in LMIC, a “need-based framework” may be more appropriate. Adequate contextual frameworks to conduct research, and understand the implications of findings, are essential to advance our understanding of the relationship between PA and the BE and eventually for formulating interventions relevant to LMIC.

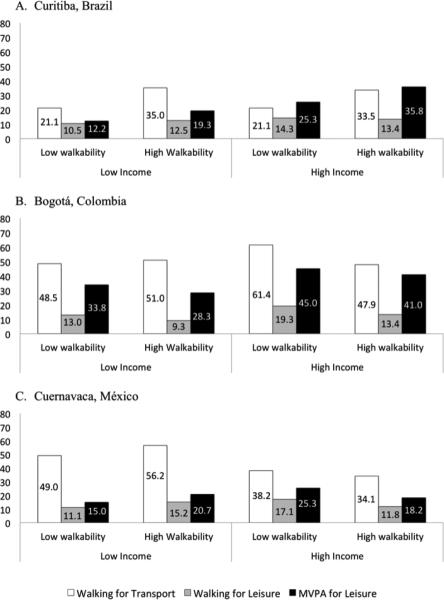

Figure 2.

Prevalence of reporting at least 150 minutes per week of walking for transport, walking for leisure, and of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity for leisure, by socioeconomic status and walkability quadrant (neighborhood level) in Curitiba (Brazil), Bogotá (Colombia) and Cuernavaca (México) (data collection: 2010 – 2011)

(No Figure 2 Legend)

An inherent limitation to the results reported here is that they represent actual field experiences rather than the formulation of specific research questions related to the challenge of conducting PA and BE studies in LMIC. Our findings are based on the experiences of research teams from three cities in three LA countries. Therefore, the results should not be considered an exhaustive list of challenges to be encountered when conducting research in other LA countries, or even in other cities within the same countries. Nonetheless, given the lack of previous large-scale, published studies in this field from LA, our findings provide the best available evidence for overcoming the challenges of conducting PA and BE research in LA. In fact, researchers from the three IPEN-LA countries have trained other LA research groups in cities where similar studies are being planned (Montevideo, Uruguay; Santiago de Chile, Chile; and Bucaramanga, Colombia, Buenos Aires, Argentina, São Paulo, Brazil). The training material included IPEN-LA protocols. More regional PA epidemiology and public health academic programs in LA institutions are needed for research capacity in this field to grow in the region.

For IPEN-LA, an important contributor to success was having the support of an influential academically oriented local institution. Access to data, students, field workers, and local government are critical to community research and depended on facilitation by the local academic partner. Research networks are clearly an important part of the process of conducting and publishing high quality research in LMIC (Pratt et al., 2010, Keusch, 2010, Mulvihill and Debas, 2010). While institutions from HIC play a key role in facilitating research in LMIC by providing financial and human resources, stability, specific technical training, and opportunities for academic exchanges, IPEN-LA demonstrated that these functions can be successfully shared across research groups in LA as well. Innovation in data collection, analysis, and interpretation of findings can emanate from LMIC institutions and investigators and be shared with colleagues in HIC. The IPEN-LA experience may be a valuable model applicable to studies being conducted in other cities in LA and in LMIC around the world.

Supplementary Material

Manuscript Highlights.

There is substantial evidence linking physical activity with the built environment

Most evidence, assessment methods and protocols are from high-income countries

Conducting research in this field in Latin America is challenging but feasible

Key challenges: capacity, data availability, instrument suitability, context and safety

Institutional support and a well-connected international network are essential

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the data collection teams and the participants of IPEN-Brazil, IPEN-Colombia and IPEN-Mexico. This work was supported by the following grants: NIH Grant R01 CA127296. NCI; NIH R01 Grant HL67350. NHLBI. Data collection in Colombia was funded by Colciencias grant 519_2010, Fogarty and CeiBA. Data collection in Mexico was supported by the CDC Foundation, which received an unrestricted training grant from The Coca-Cola Company. The Robert Wood Johnson supported the International Symposium at the Active Living Research Conference, in March, 2014, leading to this manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- AYRES RL. Crime and violence as development issues in Latin America and the Caribbean. World Bank Publications; Washington, D.C.: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- BAKEWELL PJ. A History of Latin America: c. 1450 to the Present. Wiley-Blackwell; Oxford, UK: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- BARBOZA CF, MONTEIRO SM, BARRADAS SC, SARMIENTO OL, RIOS P, RAMIREZ A, MAHECHA MP, PRATT M. Physical activity, nutrition and behavior change in Latin America: a systematic review. Global health promotion. 2013;20:65–81. doi: 10.1177/1757975913502240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARRETO SM, MIRANDA JJ, FIGUEROA JP, SCHMIDT MI, MUNOZ S, KURI-MORALES PP, SILVA JB., JR. Epidemiology in Latin America and the Caribbean: current situation and challenges. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41:557–71. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BAUMAN AE, REIS RS, SALLIS JF, WELLS JC, LOOS RJ, MARTIN BW, LANCET PHYSICAL ACTIVITY SERIES WORKING, G. Correlates of physical activity: why are some people physically active and others not? Lancet. 2012;380:258–71. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60735-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BECERRA JM, REIS RS, FRANK LD, RAMIREZ-MARRERO FA, WELLE B, ARRIAGA CORDERO E, MENDEZ PAZ F, CRESPO C, DUJON V, JACOBY E. Transport and health: a look at three Latin American cities. Cadernos de Saúde Pública. 2013;29:654–666. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BROWNSON RC, HOEHNER CM, DAY K, FORSYTH A, SALLIS JF. Measuring the built environment for physical activity: state of the science. American journal of preventive medicine. 2009;36:S99–S123. e12. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BULL FC, BAUMAN AE. Physical inactivity: the “Cinderella” risk factor for noncommunicable disease prevention. Journal of health communication. 2011;16:13–26. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2011.601226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CENTERS FOR DISEASE CONTROL AND PREVENTION . Healthy Community Design Checklist Toolkit: Spanish Version Checklist [Online] CDC: Division of Emergency and Environmental Health Services, of the National Center for Environmental Health; Atlanta, GA: [February 20 2009]. Available: http://www.cdc.gov/healthyplaces/toolkit/healthy_community_design_checklistsp.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- CERIN E, CONWAY TL, CAIN KL, KERR J, DE BOURDEAUDHUIJ I, OWEN N, REIS RS, SARMIENTO OL, HINCKSON EA, SALVO D, CHRISTIANSEN LB, MACFARLANE DJ, DAVEY R, MITAS J, AGUINAGA-ONTOSO I, SALLIS JF. Sharing good NEWS across the world: developing comparable scores across 12 countries for the Neighborhood Environment Walkability Scale (NEWS). BMC Public Health. 2013;13:309. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CERIN E, LESLIE E, DU TOIT L, OWEN N, FRANK LD. Destinations that matter: associations with walking for transport. Health Place. 2007;13:713–24. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COSTELLO A, ZUMLA A. Moving to research partnerships in developing countries. BMJ: British Medical Journal. 2000;321:827. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7264.827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CRAIG CL, MARSHALL AL, SJOSTROM M, BAUMAN AE, BOOTH ML, AINSWORTH BE, PRATT M, EKELUND U, YNGVE A, SALLIS JF, OJA P. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35:1381–95. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DANE . Encuesta de convivencia y seguridad ciudadana - Colombia. (Coexistence and public safety survey - Colombia) [Online] Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadistica (DANE: National Administrative Department of Statistics of Colombia); Bogota, Colombia: 2012. [July 25 2014]. Available: http://formularios.dane.gov.co/Anda_4_1/index.php/catalog/123. [Google Scholar]

- DATAFOHLA-CRISP . Pesquisa Nacional de Vitimização - CRISP (National Survey of Victimization) [Online] Datafohla; Sao Paulo, Brazil: 2013. [July 31 2014]. Available: http://www.crisp.ufmg.br/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/Sumario_SENASP_final.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- EBRAHIM S, PEARCE N, SMEETH L, CASAS JP, JAFFAR S, PIOT P. Tackling non-communicable diseases in low- and middle-income countries: is the evidence from high-income countries all we need? PLoS Med. 2013;10:e1001377. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FRANK LD, SALLIS JF, SAELENS BE, LEARY L, CAIN K, CONWAY TL, HESS PM. The development of a walkability index: application to the Neighborhood Quality of Life Study. Br J Sports Med. 2010;44:924–33. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2009.058701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FRENK J, FREJKA T, BOBADILLA JL, STERN C, LOZANO R, SEPULVEDA J, JOSE M. [The epidemiologic transition in Latin America]. Bol Oficina Sanit Panam. 1991;111:485–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FURTADO C. Economic development of Latin America: historical background and contemporary problems. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 1976. [Google Scholar]

- HALLAL PC, GOMEZ LF, PARRA DC, LOBELO F, MOSQUERA J, FLORINDO AA, REIS RS, PRATT M, SARMIENTO OL. Lessons learned after 10 years of IPAQ use in Brazil and Colombia. J Phys Act Health. 2010;7(Suppl 2):S259–64. doi: 10.1123/jpah.7.s2.s259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HINO AA, REIS RS, SARMIENTO OL, PARRA DC, BROWNSON RC. The built environment and recreational physical activity among adults in Curitiba, Brazil. Prev Med. 2011;52:419–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HINO AA, REIS RS, SARMIENTO OL, PARRA DC, BROWNSON RC. Built Environment and Physical Activity for Transportation in Adults from Curitiba, Brazil. J Urban Health. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s11524-013-9831-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- INEGI . Encuesta de Victimizacion y Percepcion sobre seguridad publica - ENVIPE 2013. (Victimization and public safety perception survey - ENVIPE 2013, Mexico) [Online] Instituto Nacional de Geografia y Estadistica (National Institute of Geography and Statistics of Mexico); Mexico City, Mexico: 2013. [July 31 2014]. Available: http://www3.inegi.org.mx/sistemas/tabuladosbasicos/tabgeneral.aspx?c=33623&s=est. [Google Scholar]

- ISLAM MZ. PhD Doctoral Dissertation. North Carolina State University; 2009. Children and urban neighborhoods: Relationships between outdoor activities of children and neighborhood physical characteristics in Dhaka, Bangladesh. [Google Scholar]

- KAIN J, CORDERO SH, PINEDA D, DE MORAES AF, ANTIPORTA D, COLLESE T, DE OLIVEIRA FORKERT EC, GONZÁLEZ L, MIRANDA JJ, RIVERA J. Obesity Prevention in Latin America. Current Obesity Reports. 2014;3:150–155. doi: 10.1007/s13679-014-0097-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KERR J, SALLIS JF, OWEN N, DE BOURDEAUDHUIJ I, CERIN E, SUGIYAMA T, REIS R, SARMIENTO O, FROMEL K, MITAS J, TROELSEN J, CHRISTIANSEN LB, MACFARLANE D, SALVO D, SCHOFIELD G, BADLAND H, GUILLEN-GRIMA F, AGUINAGAONTOSO I, DAVEY R, BAUMAN A, SAELENS B, RIDDOCH C, AINSWORTH B, PRATT M, SCHMIDT T, FRANK L, ADAMS M, CONWAY T, CAIN K, VAN DYCK D, BRACY N. Advancing science and policy through a coordinated international study of physical activity and built environments: IPEN adult methods. J Phys Act Health. 2013;10:581–601. doi: 10.1123/jpah.10.4.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KEUSCH GT. Models of cooperation, capacity building and the future of global health. In: PARKER R, SOMMER M, editors. Routledge Handbook of Global Public Health. Routledge; New York, NY: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- KNOX PL, MCCARTHY L. Urbanization: An introduction to urban geography. Prentice Hall; Upper Saddle River, NJ: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- LEE I-M, SHIROMA EJ, LOBELO F, PUSKA P, BLAIR SN, KATZMARZYK PT. Effect of physical inactivity on major noncommunicable diseases worldwide: an analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. The Lancet. 2012;380:219–229. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61031-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOCKHART J. Early Latin America: A History of Colonial Spanish America and Brazil. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- MCQUEEN DV. Global Handbook on Noncommunicable Diseases and Health Promotion. Springer; New York, NY: 2013. Contextual Factors in Health and Illness. [Google Scholar]

- MULVIHILL JD, DEBAS HT. Long-term Academic Partnerships for Capacity Building in Health in Developing Countries. In: PARKER R, SOMMER M, editors. Routledge handbook of global public health. Routledge; New York, NY: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- NATIONAL CENTER FOR SAFE ROUTES TO SCHOOLS . Encuesta sobre ir caminando o andando en bicicleta a la escuela, para padres. (Survey for parents on walking and biking to school) [Online] University of North Carolina Highway Safety Research Center with funding from the U.S. Dept. of Transportation Federal Highway Administration; Chapel Hill, NC: 2009. [February 20 2009]. Available: http://saferoutesinfo.org/sites/default/files/resources/Parent_Survey_Spanish.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- NATIONAL HIGHWAY TRAFFIC SAFETY ADMINISTRATION . Lista de revision para ciclistas: ¿Presenta su comunidad las condiciones viables y necesarias para que las personas monten en bicicleta? (Checklist for cyclists: Does your community have the viable conditions necessary for people to bicycle?) [Online] University of North Carolina Highway Safety Research center and the U.S. Dept. of Transportation National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; 2008a. [February 20 2009]. Available: http://www.nhtsa.gov/staticfiles/nti/pdf/bikeability-checklist-sp.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- NATIONAL HIGHWAY TRAFFIC SAFETY ADMINISTRATION . Lista de revision para peatones: ¿Que tan caminable es su comunidad? (Checklist for pedestrians: How walkable is your community?) [Online] University of North Carolina with funding from the U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration; Chapel Hill, NC: 2008b. [February 20 2009]. Available: http://www.walkbiketoschool.org/sites/default/files/walkabilitychecklist-sp.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- PARRA DC, HOEHNER CM, HALLAL PC, RIBEIRO IC, REIS R, BROWNSON RC, PRATT M, SIMOES EJ. Perceived environmental correlates of physical activity for leisure and transportation in Curitiba, Brazil. Prev Med. 2011;52:234–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PARTNERSHIPS FOR HEALTHY COMMUNITIES . Herramienta de evaluacion para caminar y andar en bicicleta en la vecindad (Neighborhood walkability and bikeability assessment) [Online] Partnerships for Healthy Communities; Commerce City, CO: 1999. [February 20 2009]. Available: http://www.p4hc.org; http://www.tchd.org/DocumentCenter/View/543. [Google Scholar]

- PRATT M, BROWNSON RC, RAMOS LR, MALTA DC, HALLAL PC, REIS RS, PARRA DC, SIMOES EJ. Project GUIA: A model for understanding and promoting physical activity in Brazil and Latin America. J Phys Act Health. 2010;7(Suppl 2):S131–4. doi: 10.1123/jpah.7.s2.s131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PRATT M, SARMIENTO OL, MONTES F, OGILVIE D, MARCUS BH, PEREZ LG, BROWNSON RC, LANCET PHYSICAL ACTIVITY SERIES WORKING, G. The implications of megatrends in information and communication technology and transportation for changes in global physical activity. Lancet. 2012;380:282–93. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60736-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PRAYURA K, LIMPAKARNJANARAT K, THONGCHAROEN P. Public health sciences and policy in developing countries. In: DETELS R, MCEWEN J, BEAGLEHOLE R, TANAKA H, editors. Oxford Textbook of Public Health. 4th Edition ed. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- REIS RS, HINO AA, KERR J, HALLAL PC. Walkability and Physical Activity: Findings from Curitiba, Brazil. American journal of preventive medicine. Am J Prev Med. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.04.020. IN PRESS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RIVERA JA, BARQUERA S, CAMPIRANO F, CAMPOS I, SAFDIE M, TOVAR V. Epidemiological and nutritional transition in Mexico: rapid increase of non-communicable chronic diseases and obesity. Public health nutrition. 2002;5:113–122. doi: 10.1079/PHN2001282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAELENS BE, HANDY SL. Built environment correlates of walking: a review. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40:S550–66. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31817c67a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAELENS BE, SALLIS JF, FRANK LD, CAIN KL, CONWAY TL, CHAPMAN JE, SLYMEN DJ, KERR J. Neighborhood environment and psychosocial correlates of adults' physical activity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012;44:637–46. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318237fe18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SALLIS JF, FLOYD MF, RODRIGUEZ DA, SAELENS BE. Role of built environments in physical activity, obesity, and cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2012;125:729–37. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.969022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SALVO D, REI RS, HINO AA, HALLAL PC, PRATT M. Intensity-Specific Leisure Time Physical Activity and the Built Environment Among Brazilian Adults: A Best-Fit Model. J Phys Act Health. 2014a doi: 10.1123/jpah.2013-0087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SALVO D, REIS RS, STEIN AD, RIVERA JA, MARTORELL R, PRATT M. Characteristics of the Built Environment in Relation to Objectively Measured Physical Activity Among Mexican Adults, 2011. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014b doi: 10.5888/pcd11.140047. Forthcoming. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SITTHI-AMORN C. Information systems and community diagnosis in developing countries. In: DETELS R, MCEWEN J, BEAGLEHOLE R, TANAKA H, editors. Oxford Textbook of Public Health. 4th Edition ed. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- SOARES RR, NARITOMI J. Understanding high crime rates in Latin America: the role of social and policy factors. The economics of crime: Lessons for and from Latin America. University of Chicago Press; Chicago, IL: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- UNITED NATIONS . World urbanization prospects : the 2011 revision : data tables and highlights. In: ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL AFFAIRS, P. D., editor. 2011 rev. ed. ed. United Nations; New York, NY: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA IN LOS ANGELES & SAN FRANCISCO DEPT OF PUBLIC HEALTH . Pedestrian Environmental Quality Index (PEQI) [Online] San Francisco Dept of Public Health & UCLA (Spanish Version); San Francisco, CA and Los Angeles, CA (Spanish Version): 2008. [February 20 2009]. Available: http://www.peqiwalkability.appspot.com/about.jsp; http://www.sfphes.org/HIA_Tools_PEQI.htm. [Google Scholar]

- VAN DYCK D, CARDON G, DEFORCHE B, SALLIS JF, OWEN N, DE BOURDEAUDHUIJ I. Neighborhood SES and walkability are related to physical activity behavior in Belgian adults. Prev Med. 2010;50(Suppl 1):S74–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WORLD BANK GROUP . World Development Indicators 2012. World Bank Publications; Washington, D.C.: 2012. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.