Abstract

Multiple neuromodulators regulate neuronal response properties and synaptic connections in order to adjust circuit function. Inhibitory interneurons are a diverse group of cells that are differentially modulated depending on neuronal subtype and play key roles in regulating local circuit activity. Importantly, new tools to target specific subtypes are greatly improving our understanding of interneuron circuits and their modulation. Indeed, recent work has demonstrated that during different behavioral states interneuron activity changes in a subtype specific manner in both neocortex and hippocampus. Furthermore, in neocortex, modulation of specific interneuron microcircuits results in pyramidal cell disinhibition with important consequences for synaptic plasticity and animal behavior. Thus, neurmodulators tune the output of different interneuron subtypes to provide neural circuits with great flexibility.

Introduction

Inhibitory interneurons are key participants in the generation of normal neural activity in the cerebral cortex and hippocampus, acting to gate the flow of information and coordinate local networks [1,2]. They are highly diverse and the many different subtypes undoubtedly play specific roles in circuit function. With the development of transgenic mouse lines to manipulate distinct interneuron cohorts, a sophisticated understanding of how distinct modes of inhibition shape neural activity is beginning to emerge [3]. Importantly, all neurons are under the influence of a diverse set of neuromodulatory systems, which are activated during different behavioral states [4,5]. These modulators adjust intrinsic membrane properties and synaptic connections in a cell type specific manner to alter how neural circuits respond to and process information. Thus, neural circuits are flexible and how they function depends on behavioral context. Here, we review recent progress towards understanding how distinct cortical interneuron subtypes are modulated during different behavioral states. Furthermore, we review the likely circuit and neuromodulatory mechanisms responsible.

Inhibitory interneurons are diverse but a subset have shared neuromodulatory response properties

Interneurons can be classified according to many features including electrophysiological characteristics, morphology, and molecular expression profile (for recent reviews see [6,7]). Different subtypes display distinct axonal branching patterns and innervate specific membrane compartments to control synaptic integration along the somato-dentritic axis [2]. Importantly, different interneuron cohorts can be identified by the differential expression of calcium-binding proteins such as parvalbumin (PV) or neuropeptides such as somatostatin (SOM) or vasointestinal peptide (VIP) [6,8,9]. Multiple transgenic mouse lines take advantage of this to selectively label or optogenetically manipulate different interneuron groups [10]. PV+ interneurons include those with a fast spiking (FS) phenotype that provide perisomatic inhibition; SOM+ interneurons are non-FS and include those that target apical dendrites; and VIP+ interneurons are all non-FS but diverse morphologically. Although useful for distinguishing broad categories, multiple subtypes are represented among the PV, SOM, and VIP expressing groups. For example, FS/PV+ interneurons include not only perisomatic basket cells but also axon targeting chandelier cells [11] and dendrite targeting bistratified cells [12], and VIP+ interneurons represent multiple subtypes [9,13-15].

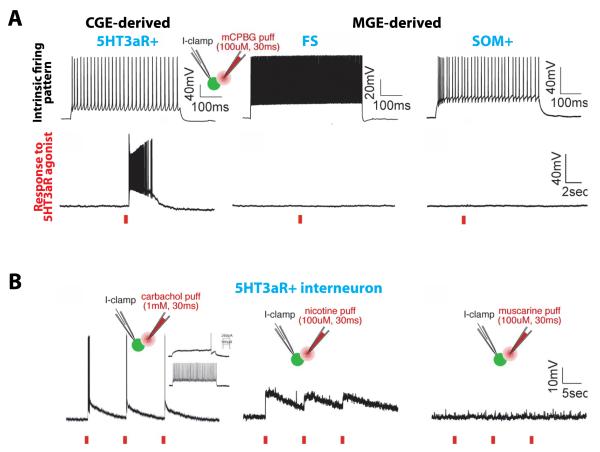

Not surprisingly, these diverse subtypes exhibit a wide range of responses to different neuromodulatory inputs, presenting a very difficult combinatorial problem. For example, basket cells can be distinguished by differential expression of PV or cholecystokinin (CCK) and these two types respond very differently to modulators such as acetylcholine, serotonin, or cannabinoids [16-19]. However, recent work on the developmental lineage of interneurons has provided a useful organizational framework for understanding their diversity and some aspects of their modulation. During embryogenesis the majority of neocortical and hippocampal interneurons are derived from the medial and caudal ganglionic eminences (MGE and CGE) [13,15,20]. In the cortex, the MGE produces PV+ and SOM+ interneurons, while the rest (including CCK+ and VIP+ interneurons and neurogliaform cells) are generated by the CGE. This is similar in the hippocampus, however the MGE also generates a large set of PV-/SOM-interneurons that includes ivy cells and a subset of neurogliaform cells [15,21]. Importantly, it was recently discovered that interneuron subtypes produced by the CGE, but not the MGE, all functionally express the ionotropic serotonin receptor 5HT3a (5HT3aR) [14**,22] (Figure 1A). Interestingly, hippocampal interneuron subtypes that appear anatomically similar, such as neurogliaform cells and oriens-lacunosum moleculare projecting interneurons, can be generated from both the CGE and MGE [21,23], and differentially express 5HT3aRs depending on their origin [23]. Furthermore, in the cortex, 5HT3aR+ interneurons might also be selectively excited by activation of ionotropic nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) [14**] (Figure 1B), in agreement with previous work demonstrating nicotinic excitation of VIP+ and CCK+ interneurons (CGE-derived) but not those that are PV+ or SOM+ or are fast spiking (MGE-derived) [24,25]. Thus, in spite of an incredible diversity of CGE-derived interneuron subtypes [13,15], they share a set of common neuromodulatory response properties. However, it should be noted that in the hippocampus both 5HT3aR+ and 5HT3aR-/SOM+ interneurons are excited by nAChR agonists [23]. The functional significance of multiple subtypes all expressing 5HT3aRs or nAChRs is currently unknown.

Figure 1.

CGE-derived interneurons are modulated by ionotropic serotonin and nicotinic acetylcholine receptors

A) Puffing m-chlorophenyl-biguanide (mCPBG) on the soma of 5HT3aR expressing interneurons but not SOM+ or FS interneurons results in depolarization and action potential firing. Top, intrinsic firing properties of the three interneuron types are different. Bottom, responses to a single 30 ms puff of 100 μM mCPBG.

B) 5HT3aR-expressing interneurons also respond to cholinergic input via nicotinic but not muscarinic acetylcholine receptors. Modified with permission from [14**].

Interneuron activity is modulated by behavioral state in a subtype specific manner

Changes in behavioral state are correlated with dramatic alterations in the dynamics of neural activity [5]. Different brain states can be most easily segregated into the “activated” state observed during waking and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep and the “synchronized” state characterized by the slow oscillation during slow wave sleep and, at least in rodents, periods of quiet wakefulness [26-28, 29**,30**,31**]. These different states are dependent on the coordinated activity of several brainstem neuromodulatory nuclei that project diffusely throughout the brain and generally exhibit increased activity during waking compared to slow wave sleep [4,32,33]. Neuromodulators alter network activity and function by adjusting the intrinsic membrane properties [34,35] and synaptic weights of neurons in a subtype dependent manner [36-38].

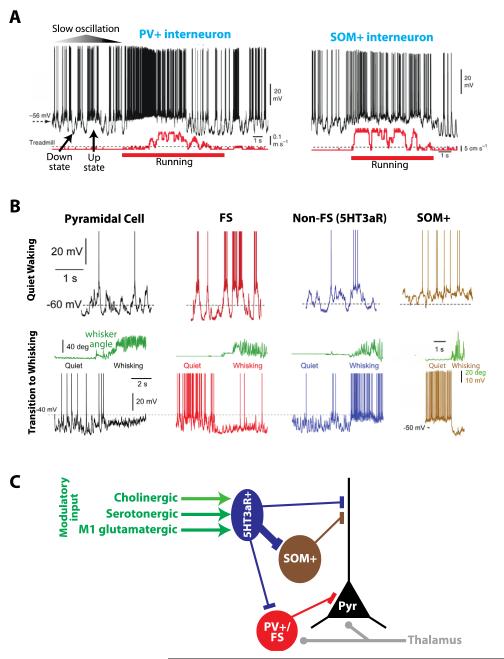

In both neocortex and hippocampus, interneuron membrane potential and firing rate are modulated during different behavioral states, as demonstrated by recent experiments in mice in vivo. In primary visual cortex, Polack and colleagues performed targeted whole-cell patch recordings of PV+ and SOM+ neurons in transgenic mice that were head-fixed but free to run on a treadmill [31**]. During quiet waking when the mouse was stationary, the membrane potential (Vm) of both subtypes exhibited rhythmic up and down states characteristic of the slow oscillation (Figure 2A). However, during locomotion their resting Vm depolarized and firing rate increased and the slow oscillation was abolished (Figure 2A). Furthermore, firing rates in response to visual stimuli were greater during movement compared to quiet waking in both subtypes [31**]. Thus, during waking some behavioral states may result in dramatically increased inhibitory input. Indeed, in awake (although stationary) mice, the total inhibitory conductance estimated at the soma of pyramidal cells was found to dominate the excitatory conductance during the entire response to visual stimuli [39].

Figure 2.

Distinct interneuron subtypes are differently modulated by behavioral state.

A) Membrane potential and firing dynamics of PV+ and SOM+ interneurons in primary visual cortex during quiet waking versus running on a treadmill. During quiet waking, both interneuron types exhibit the slow oscillation, characterized by rhythmic up and down states. In contrast, during locomotion, both subtypes become depolarized and fire tonically. Modified with permission from [31**].

B) Membrane potential dynamics and firing during quiet waking versus active whisking for four different neuronal classes in primary somatosensory cortex: excitatory pyramidal cell, FS interneuron, non-FS putative 5HT3aR expressing interneuron, and SOM+ interneuron. Only non-FS (5HT3aR) interneurons are strongly excited during whisking, while the other cell types are largely inhibited. SOM+ interneurons do not participate in the slow oscillation during quiet waking, and are strongly hyperpolarized during whisking. Modified with permission from [29**,30**].

C) Recently described inhibitory circuits in superficial cortical layers and their modulatory inputs largely explain the membrane potential dynamics observed in part B above. During active behaviors, such as whisking, cholinergic and glutamatergic (from M1) inputs excite 5HT3aR-expressing interneurons, which in turn inhibit both PV+/FS and SOM+ interneurons. Pyramidal cells are both directly inhibited and indirectly disinhibited by 5HT3aR interneurons and receive strong thalamic input during whisking. Thus, during whisking, pyramidal cells become depolarized yet their firing rate is reduced. 5HTaR expressing interneurons very likely also receive strong serotonergic input during active behaviors.

Such data could lead to the assumption that all interneurons are commonly excited or suppressed during active waking or drowsiness, respectively. However, there is much evidence for subtype dependent modulation. In primary visual cortex, Niell and Stryker observed that while many neurons with a narrow action potential waveform (putative inhibitory) increased their firing rate during locomotion, a subset were greatly suppressed [40]. Using calcium imaging in vivo, Fu et al. observed in visual cortex that during running VIP+ interneurons increased their activity while SOM+ interneurons were inhibited [41**] (the reason for the discrepancy with the findings of Polack et al. is unclear). In hippocampus, PV+ basket and bistratified cells increase their firing rate during active waking compared to quiet waking and sleep, while ivy cells, which are dendrite targeting, maintain a constant low firing rate independent of behavioral state [42*,43]. Finally, Gentet and colleagues systematically studied how behavior modulates the membrane potential and firing rate of the three broad classes of interneuron subtypes (PV+/FS, SOM+, 5HT3aR+) in primary somatosensory “barrel” cortex [29**,30**]. During quiet behaviors in which the animal was not whisking, they observed the slow oscillation in excitatory pyramidal cells, FS interneurons, and non-FS (putative 5HT3aR expressing) interneurons (Figure 2B, top). Amazingly, SOM+ interneurons did not participate in this rhythm and were persistently depolarized (Figure 2B, top). When the mouse began to actively move its whiskers, these four neuron types were each differently modulated (Figure 2B, bottom). Excitatory neurons were depolarized but their firing rate decreased; in FS interneurons the slow oscillation disappeared and their firing rate decreased; non-FS (putative 5HT3aR+) interneurons were depolarized and their firing rate increased; and SOM+ interneurons were hyperpolarized and action potentials ceased. Thus, Gentet et al. found that during an active behavior such as whisking, the 5HT3aR/CGE-derived interneuron cohort is excited but FS and SOM+ interneurons and excitatory pyramidal cells are inhibited (Figure 2B, bottom). Recent work, described in the next section, has revealed possible circuit and neuromodulatory mechanisms responsible for these shifts in membrane potential and firing dynamics (Figure 2C). Finally, although these data seem at odds with those of Polack et al. [31**], it is important to note that the cortical regions under investigation are different (visual versus somatosensory cortex), as well as the behaviors (running versus whisking while stationary).

Neuromodulation of distinct interneuron subtypes has different consequences for cortical circuit function and animal behavior

Recent work on inhibitory circuitry has focused on superficial cortical layers 1 and 2/3 due to the ability to use 2-photon microscopy to target different interneuron subtypes in transgenic mice in vivo. As described below, in these layers CGE-derived/5HT3aR expressing interneurons target neighboring PV+/FS and SOM+ interneurons as well as pyramidal cells. Cholinergic and long-range glutamatergic inputs powerfully modulate the activity of 5HT3aR+ interneurons with important consequences for circuit activity, animal behavior, and synaptic integration on pyramidal cell dendrites.

Cholinergic modulation of 5HT3aR+ cortical interneurons results in inhibition of FS/PV+ interneurons and disinhibition of pyramidal cells

In vitro, optogenetic activation of cholinergic axons or application of nicotinic agonists strongly depolarizes CGE-derived/5HT3aR interneurons in superficial cortical layers via activation of fast α7 and slow non-α7 nAChRs [44*,45]. In turn, they provide disynaptic inhibition to neighboring FS interneurons and pyramidal cells [44*,45] (Figure 2B,C). Using 2-photon calcium imaging in vivo, Alitto and Dan observed that electrical stimulation of the basal forebrain, a major source of acetylcholine, resulted in increased calcium signal amplitude in the majority of VIP+ (5HT3aR) interneurons but decreased amplitude in a subset of PV+ interneurons and excitatory cells [46**]. Furthermore, block of nAChRs, but not muscarinic AChRs (mAChRs), significantly reduced the signal amplitude in VIP+ interneurons while increasing it in PV+ and excitatory neurons [46**]. In agreement, Fu et al. found that the increased calcium signal in VIP+ interneurons they observed during running in primary visual cortex is largely due to cholinergic input acting on nAChRs [41**].

The nicotinic activation of 5HT3aR+ interneurons and their subsequent inhibition of local PV+ interneurons may be crucial for some learned behaviors. In auditory cortex, Letzkus et al. found that an aversive stimulus such as foot shock resulted in nAChR dependent spiking of layer 1 interneurons [47**] (which are 5HT3aR+ [14**]). These interneurons inhibited layer 2/3 PV+ interneurons, which in turn disinhibited layer 2/3 pyramidal neurons. Amazingly, this nAChR dependent disinhibition was required for the learned association of the foot shock with an auditory tone [47**]. It is possible that modulators such as acetylcholine and serotonin both engage disinhibitory circuits important for learned behaviors. In the cortex, both excite CGE-derived/5HT3aR+ interneurons via ionotropic receptors [14**] while causing metabotropic receptor mediated presynaptic depression of PV+ interneurons [38]. Furthermore, although cortical neurogliaform cells (which are 5HT3aR+) strongly inhibit layer 2/3 pyramidal cells [48], they are selectively hyperpolarized by activation of mAChRs, which may further enhance pyramidal cell disinhibition [49]. However, this is of course only one, of many, possible circuit configurations which likely vary depending on brain region. Recently, it was shown in hippocampus in vivo that cholinergic input excites SOM+ interneurons via mAChRs, which in turn inhibit CA1 pyramidal cell dendrites [50**]. The authors show that this direct inhibitory circuit is also necessary for learning to associate an auditory tone with an aversive stimulus [50**].

Modulation of VIP+ (5HT3aR+) interneurons results in inhibition of SOM+ interneurons and disinhibition of pyramidal cell dendrites

VIP+ interneurons also target SOM+ interneurons to disinhibit excitatory pyramidal cells [41**,51-54] (Figure 2C). In a comprehensive study, Lee and colleagues investigated input from primary motor cortex (M1) to PV+, SOM+, 5HT3aR (VIP+), and 5HT3aR (non-VIP+) interneurons and pyramidal cells in superficial layers of primary somatosensory cortex [52**]. In vitro, optogenetic activation of M1 afferents most strongly excited VIP+ interneurons, which in turn most strongly inhibited SOM+ interneurons relative to the other subtypes. Interestingly, non-VIP+ interneurons received only weak input, indicating specificity within the 5HT3aR group. During active whisking, the firing rates of VIP+ interneurons increased while those of SOM+ interneurons decreased, and this relationship was dependent on activity in M1 [52**]. This circuit can explain the Vm and firing dynamics of SOM+ and putative 5HT3aR interneurons observed by Gentet et al. during quiet waking versus whisking [29**,30**] (Figure 2B,C). Furthermore, the findings of Fu et al. indicate a similar circuit exists in primary visual cortex, in which cholinergic input to VIP+ interneurons results in inhibition of SOM+ interneurons [41**]. Interestingly, in auditory and medial prefrontal cortices, VIP+ interneurons were also found to preferentially inhibit SOM+ interneurons to disinhibit pyramidal cells [53]. Furthermore, aversive stimuli such as foot shock strongly excited VIP+ cells in auditory cortex [53]. Although the sources of modulatory input were not identified, a mechanism involving acetylcholine and serotonin would not be surprising. Thus, modulation of VIP+ interneurons may be a general circuit mechanism to control the activity of SOM+ interneurons, which target the apical dendrites of pyramidal cells to importantly regulate synaptic integration and plasticity [55,56].

Conclusions

Great progress is being made towards understanding the functional roles of different interneuron subtypes and how neuromodulators shape their activity. In particular, it is now clear that FS/PV+, SOM+, and 5HT3aR+ interneurons form a specific local circuit that may be found throughout the cortex as a general motif. Ionotropic excitation of 5HT3aR+ interneurons via nicotinic and serotonergic receptors likely serves to rapidly modulate the activity of these circuits during different behavioral contexts. However, much is still unknown, even regarding the circuits described in this review. As mentioned above, these broad interneuron classes represent many different subtypes that differently contribute to circuit function. The 5HT3aR+ group is particularly diverse and represents several anatomically, electrophysiologically, and molecularly distinct types (in cortex, there are at least four different types of VIP+ interneuron alone) [9,13-15]. Although recent progress has been made in cortex, very little is known regarding the mechanisms of modulation of distinct interneuron subtypes in the hippocampus in vivo (although see [50**]). Finally, the functional roles of most neuromodulatory systems in shaping interneuron activity are poorly understood. Interneurons respond to a variety of neuromodulators in vitro, such as norepinephrine, dopamine, and oxytocin, which still require investigation in vivo [38,57-60]. Strikingly, although a distinct subset of interneurons expresses 5HT3aRs, the behavioral contexts during which 5HT3aRs are activated and their functional roles are unknown. Fortunately, as outlined in this review, many tools are available to explore these questions, and future work will undoubtedly continue to fill in the many gaps in our knowledge.

Highlights.

Interneuron subtypes are differentially modulated depending on behavioral context

A distinct interneuron group expresses ionotropic serotonin and nicotinic receptors

Cholinergic input excites specific interneurons to activate a disinhibitory circuit

Long-range glutatmatergic input activates a disinhibitory circuit during behavior

Acknowledgements

We thank the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development for funding support. We also thank Ken Pelkey for helpful comments on this manuscript, as well as Carl Petersen, Bernardo Rudy, and Peyman Golshani for their kind permission to modify the figures presented here.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.McBain CJ, Fisahn A. Interneurons unbound. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:11–23. doi: 10.1038/35049047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klausberger T, Somogyi P. Neuronal diversity and temporal dynamics: the unity of hippocampal circuit operations. Science. 2008;321:53–57. doi: 10.1126/science.1149381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kepecs A, Fishell G. Interneuron cell types are fit to function. Nature. 2014;505:318–326. doi: 10.1038/nature12983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones BE. Arousal systems. Front Biosci. 2003;8:s438–451. doi: 10.2741/1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harris KD, Thiele A. Cortical state and attention. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12:509–523. doi: 10.1038/nrn3084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ascoli GA, Alonso-Nanclares L, Anderson SA, Barrionuevo G, Benavides-Piccione R, Burkhalter A, Buzsaki G, Cauli B, Defelipe J, Fairen A, et al. Petilla terminology: nomenclature of features of GABAergic interneurons of the cerebral cortex. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:557–568. doi: 10.1038/nrn2402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeFelipe J, Lopez-Cruz PL, Benavides-Piccione R, Bielza C, Larranaga P, Anderson S, Burkhalter A, Cauli B, Fairen A, Feldmeyer D, et al. New insights into the classification and nomenclature of cortical GABAergic interneurons. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14:202–216. doi: 10.1038/nrn3444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu X, Roby KD, Callaway EM. Immunochemical characterization of inhibitory mouse cortical neurons: three chemically distinct classes of inhibitory cells. J Comp Neurol. 2010;518:389–404. doi: 10.1002/cne.22229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rudy B, Fishell G, Lee S, Hjerling-Leffler J. Three groups of interneurons account for nearly 100% of neocortical GABAergic neurons. Dev Neurobiol. 2011;71:45–61. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taniguchi H, He M, Wu P, Kim S, Paik R, Sugino K, Kvitsani D, Fu Y, Lu J, Lin Y, et al. A resource of cre driver lines for genetic targeting of GABAergic neurons in cerebral cortex. Neuron. 2011;71:995–1013. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kawaguchi Y, Kubota Y. GABAergic cell subtypes and their synaptic connections in rat frontal cortex. Cereb Cortex. 1997;7:476–486. doi: 10.1093/cercor/7.6.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pawelzik H, Hughes DI, Thomson AM. Physiological and morphological diversity of immunocytochemically defined parvalbumin- and cholecystokinin-positive interneurones in CA1 of the adult rat hippocampus. J Comp Neurol. 2002;443:346–367. doi: 10.1002/cne.10118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miyoshi G, Hjerling-Leffler J, Karayannis T, Sousa VH, Butt SJ, Battiste J, Johnson JE, Machold RP, Fishell G. Genetic fate mapping reveals that the caudal ganglionic eminence produces a large and diverse population of superficial cortical interneurons. J Neurosci. 2010;30:1582–1594. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4515-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **14.Lee S, Hjerling-Leffler J, Zagha E, Fishell G, Rudy B. The largest group of superficial neocortical GABAergic interneurons expresses ionotropic serotonin receptors. J Neurosci. 2010;30:16796–16808. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1869-10.2010. In this study the authors show that functional 5HT3aRs are only found in CGE-derived interneurons and, in cortex, are non-overlapping with PV+ and SOM+ interneuron groups. Furthermore, these cells also express nAChRs.

- 15.Tricoire L, Pelkey KA, Erkkila BE, Jeffries BW, Yuan X, McBain CJ. A blueprint for the spatiotemporal origins of mouse hippocampal interneuron diversity. J Neurosci. 2011;31:10948–10970. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0323-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cea-del Rio CA, Lawrence JJ, Tricoire L, Erdelyi F, Szabo G, McBain CJ. M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor expression confers differential cholinergic modulation to neurochemically distinct hippocampal basket cell subtypes. J Neurosci. 2010;30:6011–6024. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5040-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foldy C, Lee SY, Szabadics J, Neu A, Soltesz I. Cell type-specific gating of perisomatic inhibition by cholecystokinin. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1128–1130. doi: 10.1038/nn1952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferezou I, Cauli B, Hill EL, Rossier J, Hamel E, Lambolez B. 5-HT3 receptors mediate serotonergic fast synaptic excitation of neocortical vasoactive intestinal peptide/cholecystokinin interneurons. J Neurosci. 2002;22:7389–7397. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-17-07389.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Armstrong C, Soltesz I. Basket cell dichotomy in microcircuit function. J Physiol. 2012;590:683–694. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.223669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Butt SJ, Fuccillo M, Nery S, Noctor S, Kriegstein A, Corbin JG, Fishell G. The temporal and spatial origins of cortical interneurons predict their physiological subtype. Neuron. 2005;48:591–604. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tricoire L, Pelkey KA, Daw MI, Sousa VH, Miyoshi G, Jeffries B, Cauli B, Fishell G, McBain CJ. Common origins of hippocampal Ivy and nitric oxide synthase expressing neurogliaform cells. J Neurosci. 2010;30:2165–2176. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5123-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vucurovic K, Gallopin T, Ferezou I, Rancillac A, Chameau P, van Hooft JA, Geoffroy H, Monyer H, Rossier J, Vitalis T. Serotonin 3A receptor subtype as an early and protracted marker of cortical interneuron subpopulations. Cereb Cortex. 2010;20:2333–2347. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chittajallu R, Craig MT, McFarland A, Yuan X, Gerfen S, Tricoire L, Erkkila B, Barron SC, Lopez CM, Liang BJ, et al. Dual origins of functionally distinct O-LM interneurons revealed by differential 5-HT3AR expression. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:1598–1607. doi: 10.1038/nn.3538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Porter JT, Cauli B, Tsuzuki K, Lambolez B, Rossier J, Audinat E. Selective excitation of subtypes of neocortical interneurons by nicotinic receptors. J Neurosci. 1999;19:5228–5235. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-13-05228.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xiang Z, Huguenard JR, Prince DA. Cholinergic switching within neocortical inhibitory networks. Science. 1998;281:985–988. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5379.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vanderwolf CH. Neocortical and hippocampal activation relation to behavior: effects of atropine, eserine, phenothiazines, and amphetamine. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1975;88:300–323. doi: 10.1037/h0076211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crochet S, Petersen CC. Correlating whisker behavior with membrane potential in barrel cortex of awake mice. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:608–610. doi: 10.1038/nn1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steriade M, Timofeev I, Grenier F. Natural waking and sleep states: a view from inside neocortical neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2001;85:1969–1985. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.5.1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **29.Gentet LJ, Kremer Y, Taniguchi H, Huang ZJ, Staiger JF, Petersen CC. Unique functional properties of somatostatin-expressing GABAergic neurons in mouse barrel cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15:607–612. doi: 10.1038/nn.3051. In a follow up to reference 30**, interneurons are further parsed into FS, non-FS (SOM+), and non-FS (SOM-) groups in recordings from awake bahaving mice. Amazingly, these three groups each exhibit different membrane potential and firing dynamics during quiet waking versus active whisking.

- **30.Gentet LJ, Avermann M, Matyas F, Staiger JF, Petersen CC. Membrane potential dynamics of GABAergic neurons in the barrel cortex of behaving mice. Neuron. 2010;65:422–435. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.01.006. The authors show for the first time that in primary somatosensory “barrel” cortex, excitatory cells, FS interneurons, and non-FS interneurons each exhibit different membrane potential and firing dynamics during different behavioral states.

- **31.Polack PO, Friedman J, Golshani P. Cellular mechanisms of brain state-dependent gain modulation in visual cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:1331–1339. doi: 10.1038/nn.3464. This study demonstrates that in primary visual cortex in vivo, PV+ and SOM+ interneurons transition from the slow oscillation during quiet waking to sustained depolarization and action potential firing during locomotion. The authors further dissect the contributions of different neurmodulatory systems to the membrane potential dynamics of excitatory cells.

- 32.Steriade M. Acetylcholine systems and rhythmic activities during the waking--sleep cycle. Prog Brain Res. 2004;145:179–196. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(03)45013-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee MG, Hassani OK, Alonso A, Jones BE. Cholinergic basal forebrain neurons burst with theta during waking and paradoxical sleep. J Neurosci. 2005;25:4365–4369. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0178-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McCormick DA, Wang Z, Huguenard J. Neurotransmitter control of neocortical neuronal activity and excitability. Cereb Cortex. 1993;3:387–398. doi: 10.1093/cercor/3.5.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cea-del Rio CA, Lawrence JJ, Erdelyi F, Szabo G, McBain CJ. Cholinergic modulation amplifies the intrinsic oscillatory properties of CA1 hippocampal cholecystokinin-positive interneurons. J Physiol. 2011;589:609–627. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.199422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gil Z, Connors BW, Amitai Y. Differential regulation of neocortical synapses by neuromodulators and activity. Neuron. 1997;19:679–686. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80380-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hasselmo ME, Bower JM. Cholinergic suppression specific to intrinsic not afferent fiber synapses in rat piriform (olfactory) cortex. J Neurophysiol. 1992;67:1222–1229. doi: 10.1152/jn.1992.67.5.1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kruglikov I, Rudy B. Perisomatic GABA release and thalamocortical integration onto neocortical excitatory cells are regulated by neuromodulators. Neuron. 2008;58:911–924. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haider B, Hausser M, Carandini M. Inhibition dominates sensory responses in the awake cortex. Nature. 2013;493:97–100. doi: 10.1038/nature11665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Niell CM, Stryker MP. Modulation of visual responses by behavioral state in mouse visual cortex. Neuron. 2010;65:472–479. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.01.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **41.Fu Y, Tucciarone JM, Espinosa JS, Sheng N, Darcy DP, Nicoll RA, Huang ZJ, Stryker MP. A cortical circuit for gain control by behavioral state. Cell. 2014;156:1139–1152. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.01.050. Using calcium imaging in awake behaving mice, the authors show that VIP+ interneurons in primary somatosensory, auditory, and visual cortices are excited during running. They show that in visual cortex this is due to cholinergic input from the basal forebrain, and propose that this circuit mediates the observation of enhanced responsiveness of excitatory neurons to visual stimulation during locomotion.

- *42.Lapray D, Lasztoczi B, Lagler M, Viney TJ, Katona L, Valenti O, Hartwich K, Borhegyi Z, Somogyi P, Klausberger T. Behavior-dependent specialization of identified hippocampal interneurons. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15:1265–1271. doi: 10.1038/nn.3176. In awake behaving rats, interneurons were juxtacellularly labled during recording for post-hoc morphological analysis. Along with reference 43, this is one of the few studies in hippocampus that relates behavioral state to activity in identified interneuron subtypes.

- 43.Katona L, Lapray D, Viney TJ, Oulhaj A, Borhegyi Z, Micklem BR, Klausberger T, Somogyi P. Sleep and movement differentiates actions of two types of somatostatin-expressing GABAergic interneuron in rat hippocampus. Neuron. 2014;82:872–886. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *44.Arroyo S, Bennett C, Aziz D, Brown SP, Hestrin S. Prolonged disynaptic inhibition in the cortex mediated by slow, non-alpha7 nicotinic excitation of a specific subset of cortical interneurons. J Neurosci. 2012;32:3859–3864. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0115-12.2012. This study found that optogenetic activation of cholinergic axons excited multiple interneuron subtypes identified by firing properties and basic morphology via activation of slow non-α7 nAChRs, which in turn inhibited FS interneurons and excitatory pyramidal cells. These subtypes belong to the CGE-derived/5HT3aR-expressing group identified in reference 14.

- 45.Christophe E, Roebuck A, Staiger JF, Lavery DJ, Charpak S, Audinat E. Two types of nicotinic receptors mediate an excitation of neocortical layer I interneurons. J Neurophysiol. 2002;88:1318–1327. doi: 10.1152/jn.2002.88.3.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **46.Alitto HJ, Dan Y. Cell-type-specific modulation of neocortical activity by basal forebrain input. Front Syst Neurosci. 2012;6:79. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2012.00079. In vivo 2-photon calcium imaging in cortex of responses of PV+ and VIP+ interneurons and excitatory cells to electrical stimulation of the basal forebrain. The authors dissect the contributions of nAChRs, mAChRs, glutamatergic receptors to the calcium signal amplitude using antagonists of each.

- **47.Letzkus JJ, Wolff SB, Meyer EM, Tovote P, Courtin J, Herry C, Luthi A. A disinhibitory microcircuit for associative fear learning in the auditory cortex. Nature. 2011;480:331–335. doi: 10.1038/nature10674. In mouse auditory cortex, the authors systematically determine the circuit and modulatory mechanisms underlying the learned association of an auditory tone with a foot shock. They show that foot shock (but not the tone) excites layer 1 interneurons via nicotinic but not glutatmateric input. They then show that layer 1 interneurons inhibit L2/3 FS cells to disinhibit L2/3 pyramidal cells, in a circuit necessary for fear learning.

- 48.Wozny C, Williams SR. Specificity of synaptic connectivity between layer 1 inhibitory interneurons and layer 2/3 pyramidal neurons in the rat neocortex. Cereb Cortex. 2011;21:1818–1826. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhq257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brombas A, Fletcher LN, Williams SR. Activity-dependent modulation of layer 1 inhibitory neocortical circuits by acetylcholine. J Neurosci. 2014;34:1932–1941. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4470-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **50.Lovett-Barron M, Kaifosh P, Kheirbek MA, Danielson N, Zaremba JD, Reardon TR, Turi GF, Hen R, Zemelman BV, Losonczy A. Dendritic inhibition in the hippocampus supports fear learning. Science. 2014;343:857–863. doi: 10.1126/science.1247485. In this comprehensive and techically sophisticated study, the authors investigate the circuit and modulatory mechanisms of associative fear learning in the hippocampus. They use 2-phone calcium imaging and targeted silencing of SOM+ and PV+ interneuron populations to determine their activity and behavioral contributions to fear learning. Furthermore, via local application of receptor antagonists they determine that SOM+ interneurons are excited via mAChRs.

- 51.Dalezios Y, Lujan R, Shigemoto R, Roberts JD, Somogyi P. Enrichment of mGluR7a in the presynaptic active zones of GABAergic and non-GABAergic terminals on interneurons in the rat somatosensory cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2002;12:961–974. doi: 10.1093/cercor/12.9.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **52.Lee S, Kruglikov I, Huang ZJ, Fishell G, Rudy B. A disinhibitory circuit mediates motor integration in the somatosensory cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:1662–1670. doi: 10.1038/nn.3544. A comprehensive study both in vitro and in vivo that revealed a disinhibitory microcircuit among VIP+, SOM+, and pyramidal cells of rodent primary somatosensory cortex. During whisking, primary motor cortex excited VIP+ interneurons which in turn inhibited SOM+ interneurons. This circuit can explain the results in refs 29 and 30.

- 53.Pi HJ, Hangya B, Kvitsiani D, Sanders JI, Huang ZJ, Kepecs A. Cortical interneurons that specialize in disinhibitory control. Nature. 2013 doi: 10.1038/nature12676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pfeffer CK, Xue M, He M, Huang ZJ, Scanziani M. Inhibition of inhibition in visual cortex: the logic of connections between molecularly distinct interneurons. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:1068–1076. doi: 10.1038/nn.3446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Larkum ME, Nevian T, Sandler M, Polsky A, Schiller J. Synaptic integration in tuft dendrites of layer 5 pyramidal neurons: a new unifying principle. Science. 2009;325:756–760. doi: 10.1126/science.1171958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Murayama M, Perez-Garci E, Nevian T, Bock T, Senn W, Larkum ME. Dendritic encoding of sensory stimuli controlled by deep cortical interneurons. Nature. 2009;457:1137–1141. doi: 10.1038/nature07663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Paspalas CD, Papadopoulos GC. Noradrenergic innervation of peptidergic interneurons in the rat visual cortex. Cereb Cortex. 1999;9:844–853. doi: 10.1093/cercor/9.8.844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bergles DE, Doze VA, Madison DV, Smith SJ. Excitatory actions of norepinephrine on multiple classes of hippocampal CA1 interneurons. J Neurosci. 1996;16:572–585. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-02-00572.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gorelova N, Seamans JK, Yang CR. Mechanisms of dopamine activation of fast-spiking interneurons that exert inhibition in rat prefrontal cortex. J Neurophysiol. 2002;88:3150–3166. doi: 10.1152/jn.00335.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Owen SF, Tuncdemir SN, Bader PL, Tirko NN, Fishell G, Tsien RW. Oxytocin enhances hippocampal spike transmission by modulating fast-spiking interneurons. Nature. 2013;500:458–462. doi: 10.1038/nature12330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]