Abstract

Cancer stem cells (CSCs) are key drivers of tumor progression and disease recurrence in multiple myeloma (MM). However, little is known about the regulation of MM stem cells. Here, we show that a population of MM cells, known as the side population (SP), exhibits stem-like properties. Cells that constitute the SP in primary MM isolates are negative or seldom expressed for CD138 and CD20 markers. Moreover, the SP population contains stem cells that belong to the same lineage as the mature neoplastic plasma cells (MPC). Importantly, our data indicate that the side (SP) and non-side (NSP) population percentages in heterogeneous MM cells are balanced, and that this balance can be achieved through a prolonged in vitro culture. Furthermore, we show that SP cells, with confirmed molecular characteristics of MM stem cells, can be regenerated from purified NSP cell populations. We also show that the percentage of SP cells can be enhanced by the hypoxic stress, which is frequently observed within MM tumors. Finally, hypoxic stress enhanced the expression of transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1) and blocking the TGF-β1 signaling pathway inhibited the NSP de-differentiation. Taken together, these findings indicate that the balance between MM SP and NSP is regulated by environmental factors and TGF-β1 pathway is involved in hypoxia-induced increase of SP population. Understanding the mechanisms that facilitate SP maintenance will accelerate the design of novel therapeutics aimed at controlling these cells in MM.

Keywords: multiple myeloma, cancer stem cells, side population, environmental factors

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is the second most common hematologic cancer in the United States, comprising 10–15% of all hematopoietic malignancies and causing 20% of all deaths from these diseases.1 Although new therapeutic approaches have improved clinical outcomes and increased median patient survival rates, most MM patients eventually relapse and their disease becomes incurable.2, 3 Recent studies revealed that MM cancer stem cells (CSCs) play a critical role in disease resistance to both radiation and chemotherapy because CSCs are significantly less sensitive to these therapies than are the non-stem cells.4–6 Therefore, it was hypothesized that current therapeutic approaches only target the non-stem compartment, but have little or no effect on the CSCs, which then replenish the bulk of the tumor, leading to disease relapse.5, 7, 8 Despite these important CSC functions, most of their biological properties related to MM pathogenesis remain unknown.

While various CSCs markers have been identified and confirmed in other cancer types (e.g., CD34+/CD38− for leukemic stem cells and CD133+ for colon cancer stem cells),9, 10 studies aimed at the identification of MM CSC markers produced controversial results.7, 11–13 For example, some studies suggested that the MM stem population is only present in the CD138+ sub-population, while yet others showed the opposite result.4, 11, 14, 15 However, several of these studies11, 16, 17 identified CSCs in the MM side population (SP) cells, which are characterized based on their ability to export Hoechst 33342 dye via an ATP-binding cassette (ABC) membrane transporter. These studies have shown that SP cells exhibit key characteristics of cancer stem cells, including differentiation, repopulation, clonogenicity, and self-renewal abilities.11, 16, 17 Since SP cells exhibit a clonogenic and tumorigenic potential and are found in the majority of MM samples, they can be used as a surrogate approach to identify fractions of MM CSCs.4, 7, 18, 19

In this study, we show that SP cells isolated from MM cell lines express CD138, as previously reported.7, 19 In contrast, SP cells present in primary MM samples were CD138 negative or exhibited low CD138 expression. An immunoglobulin heavy chain (IGH) rearrangement study revealed that the SP cells and the mature neoplastic plasma cells (MPC) isolated from myeloma patients share an identical IGH rearrangement pattern, which is suggestive of their common differentiation lineage. A study by Jakubikova et al.7 has reported that cells from the non-side population (NSP) can de-differentiated into the SP cells, although the longest time point in their experiments was 5 days and the resultant percentage of regenerated SP cells was significantly lower than that observed in the parental cell lines. In our study, we also show that NSP cells can produce SP cells, albeit following an extended culture period. Moreover, our results indicate that the SP and NSP percentages are balanced in MM cells and this balance can be modulated by tumor hypoxia. Subsequent to hypoxia, expression of TGF-β1 was up-regulated, and blocking the TGF-β1 signaling pathway inhibited NSP de-differentiation. Therefore, our study provides new insights to understanding MM CSC biology and indicates that TGF-β1 signaling could provide novel therapeutic targets for treatment of MM.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell cultures and reagents

MM cell lines RPMI8226, U266, and NCI-H929 were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA). The cell lines were initially expanded in culture and then cryopreserved within 1 month of receipt. Cells were used for 3 months, and at that time a fresh vial of cryopreserved cells was cultured. RPMI8226 GL cells, expressing the green fluorescent protein (GFP) and luciferase, were generated according to the manufacturer’s protocol by transfection with a pLenti6/V5 plasmid (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA) that contained a green fluorescent protein-luciferase fusion gene. All MM cell lines were grown in RPMI 1640 (Life Technologies) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Atlanta Biologicals, Atlanta, GA, USA), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 µg/mL streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Houston, TX, USA), as previously reported.20 A hypoxia incubator (Sanyo North America, San Diego, CA, USA) was used to maintain cultures under hypoxic conditions. Single colonies from purified RPMI8226 GL NSP were isolated utilizing a limiting dilution technique in 96-well plates, and then sub-cultured into larger vessels.

Primary tumor cells were purified from freshly isolated bone marrow samples collected from MM patients at the time of diagnosis by Ficoll (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH, USA) density sedimentation.21 Cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 containing 10% FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 µg/mL streptomycin, and 2 mmol/L-glutamine, and maintained at 37°C in 5% CO2. Approval for these studies was obtained from the Houston Methodist Research Institutional (HMRI) Review Board. Informed consent was obtained from all patients in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki protocol.

All chemicals, unless otherwise stated, were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA).

MM SP cells analysis and sorting using Hoechst 33342 staining

The Hoechst 33342 staining was performed using a modified method described by Goodell et al.22 Specifically, to identify the SP in cultured MM cell lines, cells were seeded at 0.5 × 106 cells/ml in T75 flasks for 72 hours in RPMI 1640 media supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 µg/ml streptomycin. Following a 72-hour culture, cells were harvested, washed in pre-warmed wash buffer (RPMI 1640 containing 2% FBS and 10 mmol/L HEPES), counted, and viability was evaluated using trypan blue. Only cells with viability >95% were used for SP staining. Cells were then resuspended in the wash buffer (above) to a final concentration of 1 × 106 cells/mL. Hoechst 33342 was added to a final concentration of 5 µg/mL, and the cells incubated for 90 minutes in a water bath at 37 °C, with shaking every 15 minutes. Following incubation, samples were immediately put on ice to stop dye efflux and washed with ice-cold Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS) containing 2% FBS and 10 mmol/L HEPES. Subsequently, the cells were centrifuged for 5 minutes at 300 g at 4° and resuspended in ice-cold HBSS containing 2% FBS and 10 mmol/L HEPES. All samples were kept on ice prior to flow cytometric analysis. Propidium iodide (PI) solution was added to the cell suspension to a final concentration of 2 µg/mL and used for dead cell exclusion. Resperpine, an ABC transporter inhibitor, was added to one aliquot of cells incubated with Hoechst 33342 at a final concentration of 50 µmol/L and used as a negative control.7

To identify the SP in primary MM samples, cells were harvested and washed in pre-warmed wash buffer, and SP staining performed following the same method as above.

Following the staining procedure, the cells were then filtered through a 70-µm filter to obtain a single cell suspension, which was analyzed using flow cytometry on LSR II (BD Biosciences, San. Jose, CA, USA) or sorted using FACS Aria (BD Biosciences). The Hoechst 33342 dye has the excitation of 357 nm and its fluorescence emission was measured at 450/40 nm (“Hoechst Blue”) and 670/40 nm (“Hoechst Red”). After sorting, SP cell fractions were analyzed using flow cytometry to verify population purity.

Phenotype analysis of SP and NSP in MM cell lines and primary MM samples

Following the Hoechst 33342 staining, MM cell lines were washed and stained with a fluorescent-labeled CD138 antibody (BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA) for 30 minutes at 4 °C in the dark. Similarly, primary MM cells were washed and stained with fluorescent-labeled antibodies (Table 1), purchased from BioLegend, for 30 minutes at 4 °C in the dark immediately after the Hoechst 33342 staining. Flow cytometric data acquisition and analysis were performed with DIVA software (BD Biosciences).

Table 1. Phenotype of SP and NSP in primary patient samples.

Hoechst 33342-based SP staining was performed in eight primary BM samples followed with fluorescent-labeled antibodies staining. The percentages of the positive population of listed CD markers in SP and NSP from each primary sample are shown.

| MM Case | #1 | #2 | #3 | #4 | #5 | #6 | #7 | #8 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SP | NSP | SP | NSP | SP | NSP | SP | NSP | SP | NSP | SP | NSP | SP | NSP | SP | NSP | |

| CD10 | 2 | 17 | 1 | 8 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 14 | 1 | 10 | 0 | 13 |

| CD20 | 0 | 12 | 2 | 15 | 0 | 10 | 5 | 18 | 0 | 9 | 1 | 12 | 3 | 7 | 0 | 20 |

| CD31 | 100 | 39 | 79 | 29 | 83 | 72 | 94 | 91 | 63 | 69 | 10 | 12 | 9 | 18 | 41 | 73 |

| CD34 | 0 | 34 | 38 | 11 | 3 | 5 | 16 | 7 | 4 | 11 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 7 | 5 | 8 |

| CD44 | 73 | 32 | 85 | 7 | 91 | 87 | 90 | 77 | 82 | 7 | 4 | 12 | 4 | 9 | 0 | 21 |

| CD45 | 9 | 81 | 76 | 97 | 88 | 66 | 83 | 55 | 99 | 88 | 97 | 14 | 97 | 85 | 98 | 93 |

| CD50 | 100 | 95 | 98 | 98 | 99 | 93 | 94 | 55 | 100 | 92 | 84 | 89 | 88 | 85 | 96 | 93 |

| CD138 | 0 | 10 | 3 | 25 | 4 | 32 | 7 | 15 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 6 | 3 | 12 | 0 | 15 |

| CD184 | 14 | 3 | 11 | 2 | 15 | 15 | 14 | 32 | 18 | 27 | 7 | 18 | 23 | 68 | 3 | 31 |

Immunoglobulin heavy chain (IGH) gene rearrangement analysis

Primary MM cells were stained with Hoechst 33342 and fluorescent-labeled CD138 antibody and SP and NSP/CD138+ cells were isolated by cell sorting using FACS Aria. DNA isolation was performed using the QIAmp system (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA), the resultant DNA concentration was estimated by NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer, and DNA quality was assessed with Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). PCR primer sequences for IGH variable gene framework region 3 (FR3) analysis was designed as previously reported,23 and PCR was used to assess clonality using the BIOMED-2 system.24 PCR master mixes were purchased from Invivoscribe Technologies (San Diego, CA, USA), and PCR was performed as per the manufacturer’s instructions using HotStart Taq DNA polymerase (Qiagen).25

Soft agar clonogenicity assay

A soft agar colony assay was performed as previously reported.20 Briefly, 1.5 mL base agar of 0.6% agarose was prepared by combining equal volumes of 1.2% low melting temperature agarose (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 2× RPMI 1640 + 20% FBS + 2× antibiotics, and then pipetted into the 35 mm dishes. Then, 5 × 103 of sorted SP or NSP cells were resuspended in 0.75 mL of 2× RPMI 1640 + 20% FBS + 2× antibiotics, mixed with 0.75 mL of 0.6% agar, and immediately plated on top of base agar. The cell/agar suspension was overlaid with complete culture medium, which was replaced twice per week. After 2 weeks, cell colonies were stained with methylene blue, images acquired under a phase contrast microscope, and colony number estimated by direct counts.

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR

Total cellular RNA was extracted and cDNA synthesized as previously described.26 Briefly, real-time PCR was conducted using an ABI 7500 system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) utilizing an AmpliTaq Gold DNA polymerase (Life Technologies). All cDNA samples were analyzed in triplicate, and primers were used at a concentration of 100 nmol/L per reaction. After an initial denaturation step of 95°C for 10 minutes, the cDNA products were amplified with 40 PCR cycles (denaturation: 95°C for 15 seconds; extension: 60°C for 1 minute). For each sample, the Ct value was determined as the cycle number at which the fluorescence intensity reached 0.05; this value was chosen after confirming that all curves were in the exponential phase of amplification in this range. Relative expression was calculated using the delta-Ct method using the following equations: ΔCt (Sample) = Ct (Target) − Ct (Reference); relative quantity = 2−ΔCt. Differentially expressed genes were identified using statistical analyses. For each cDNA sample, the Ct value of each target sequence was normalized to the corresponding 18S rRNA reference gene. Primer sequences are listed in Supplemental Table 1.

Animal study

In vivo experiments were done in accordance with the HMRI institutional guidelines for the use of laboratory animals. To determine tumorigenicity of regenerated SP cells, 8- to 10-week-old NOD/SCID IL2rg−/− mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) (six mice per group) were injected subcutaneously with 0.1 × 106 SP or NSP cell populations isolated from the RPMI8226 GL cell line and suspended in Matrigel (BD Biosciences). Tumor engraftment was monitored weekly by whole-body bioluminescence imaging. Luciferin substrate (Gold Bio Technology, St. Louis, MO, USA) was injected intraperitoneally (IP) and whole-body imaging performed on the Xenogen IVIS system (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA), as previously reported.20 Mice were euthanized on day 35 in accordance with institutional guidelines. Bioluminescence signal intensity representative of tumor sizes was quantified by Living Image 3.1 (PerkinElmer).

To determine the ability of SP and NSP cells to infiltrate the mouse bone marrow (BM), mice (same as above) were injected via the lateral tail vein with 0.2 × 106 sorted SP or NSP cells. Tumor engraftment was monitored using bioluminescence for 3 weeks. Mice were then euthanized and bone marrow cells were flushed with PBS from femora and tibiae using a 25-gauge needle. The percentage of GFP-positive cells was determined by flow cytometry.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted with the SPSS 10 statistical software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) using t-tests or 1-way ANOVA.

Results

Characterization of SP cells in MM cell lines and primary myeloma samples

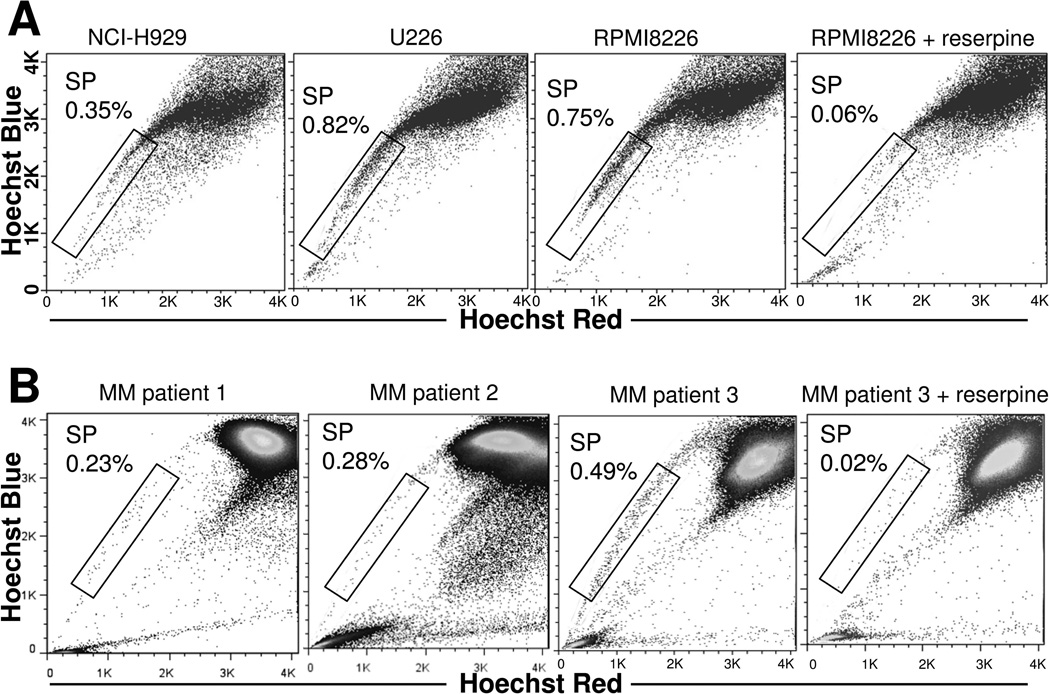

Gating on the SP fraction using flow cytometry revealed the presence of approximately 0.3–0.8% SP cells in all examined MM cell lines (Figure 1A) and 0.2–0.5% SP cells in all examined MM patient BM samples (Figure 1B). Since these numbers were very similar among all samples, the results implied that the percentage of SP cells present in MM is tightly regulated. Importantly, reserpine, an ABC transporter inhibitor, completely abolished the detection of SP population in MM cell lines and primary samples, confirmed appropriate gating (Figure 1A and Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Identification of SP cells in MM cell lines and patient BM samples.

(A) Hoechst 33342-based SP analysis of MM cell lines. (B) Hoechst 33342-based SP analysis of MM patient BM samples. Three representative images are shown from 8 MM patients. Reserpine treatment was used as a negative control to confirm appropriate gating. (C) Hoechst 33342-based SP staining was performed in RPMI8226 and U266 cells, followed by CD138-APC staining. Representative results from RPMI8226 are shown. (D) Hoechst 33342-based SP staining was performed in 8 MM patient BM samples, followed by CD138-APC staining. Results shown are for a single representative sample. (E) IGH rearrangement study was performed in SP and MPC (NSP/CD138+) cells isolated from primary MM samples. All experiments were repeated three times, and representative results are shown.

To determine the expression of CD138 in SP and NSP populations of MM cell lines and primary samples, cells were incubated with fluorescent-labeled anti-CD138 antibody immediately following the Hoechst 33342 staining. As shown in Figure 1C, SP cells in tested MM cell lines expressed CD138, as reported previously.7, 19 In contrast, SP cells isolated from 4 of 8 primary MM samples were CD138 negative, while the remaining 4 samples exhibited weak CD138 expression (Figure 1D and Table 1). We also studied the expression of CD10, CD20, CD31, CD34, CD44, CD45, CD50, and CD184 in SP and NSP populations of primary MM samples. CD20 and CD138 were absent or seldom expressed in SP populations of all primary samples, compared with much higher percentages found in NSP cells (Table 1). Interestingly, we did not identify any additional phenotypic differences between SP and NSP population isolated from 8 MM patients. Finally, the IGH rearrangement study revealed that the SP and CD138+ NSP (mature plasma cells, MPC) populations exhibit an identical IGH rearrangement pattern (Figure 1E), suggestive of the same cell lineage.

Reconstruction of SP in SP-depleted cell clones

One previous study reported that a small number of SP cells arise from purified NSP populations following 5 days of culture,7 but the percentage of these regenerated SP cells was significantly lower than that of parental cells. In order to determine whether the number of SP cells could be increased over time in a long-term culture, SP and NSP cells were sorted from parental RPM8226 and U266 cells using Hoechst 33342 staining and passaged in vitro. Changes in the percentage of SP cells present in purified SP, NSP, and parental cells were continuously monitored. As shown in Figure 2A, prolonged cell passaging resulted in the reduction of SP population in purified SP cells collected from RPMI8226 to 4.2% in 1 month and 0.72% in 2 months. Conversely, the SP population increased in the purified NSP fraction collected from parental RPMI8226 to 0.11% after 3 months and 0.39% after 4 months. After 5 months of continuous culture, there was no significant difference between the parental, purified SP, and purified NSP cells. Similar results were observed in U266 cells (Figure 2B). Our mechanistic model is summarized in Figure 2C. We believe that the SP population must be maintained at a certain level in order to maintain tumorigenicity. Our data also suggest that both NSP and SP cells can reconstitute the SP cell population following a long-term in vitro culture.

Figure 2. Purified SP or NSP cells can individually restore the fraction of SP cells.

Purified MM SP and NSP cells from RPMI8226 (A) and U266 (B), as well as control parental cells, were cultured for 5 months and the SP fractions were monitored. Data shown are mean ± s.d. of triplicate experiments (**P<0.01). (C) Schematic summary. The MM SP fraction can be restored by the purified NSP or SP cells alone.

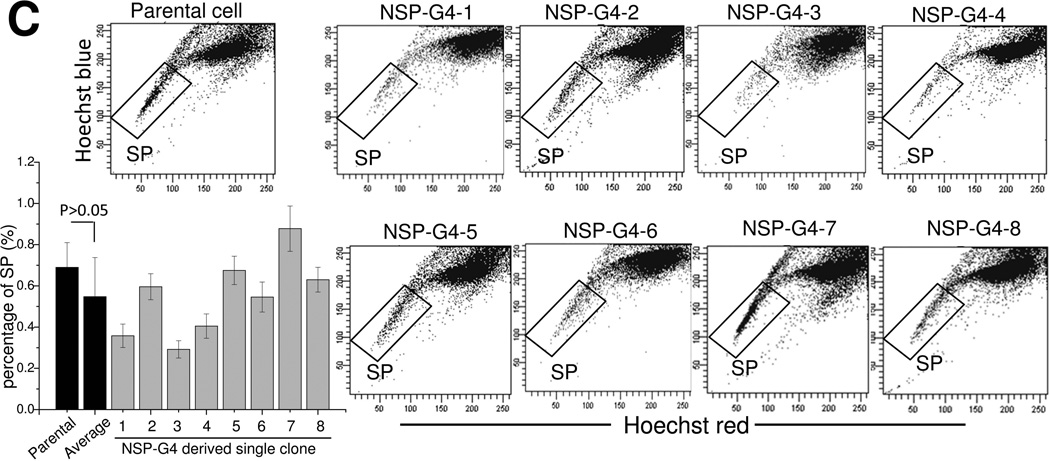

Since another possibility explaining our data is that the purified NSP population was contaminated with SP cells during cell sorting, NSP cells were purified from RPMI8226 GL cells by depleting the SP cells with Hoechst 33342 staining. The resulting culture was named NSP-G1. After 2 weeks, NSP-G2 was sorted out from NSP-G1 as above, followed by another cell sorting 2 weeks later to establish NSP-G3 and yet another one to establish NSP-G4. Our flow cytometry analyses revealed that the NSP-G4 population was largely devoid of SP cells (Figure 3A). These NSP-G4 cells were then used for single-cell clonogenicity studies and eight single-cell colonies were established for subsequent studies (the new cell lines were named NSP-G4-1 – NSP-G4-8) (Figure 3A). Given the extremely low number of cells in the SP population of NSP-G4 cells, the probability that all 8 single-cell colonies were formed by the contaminating SP cells is negligible. We measured the SP population in these 8 single-cell colonies over time after 3 (Figure 3B) and 5 months (Figure 3C). As shown in Figure 3B, the SP population arose in all 8 colonies after 3 months of culture, although the average SP population fraction was much lower than that of parental cells (0.11% versus 0.66%, p<0.01). Following 5 months, this number increased further and there was no longer a significant difference between the average SP fraction measured in all 8 colonies and the parental cells (0.55% versus 0.68%, p<0.01).

Figure 3. NSP-G4-derived single clones are capable of reconstituting the SP fraction.

(A) Repetitive NSP purification and establishment of 8 single clones from NSP-G4. Hoechst 33342-based SP analysis of NSP-G4-derived single clones following culture for 3 months (B) or 5 months (C). Representative flow cytometry dot plot images from triplicate experiments, with data presented as mean ± s.d. of triplicate experiments (**P<0.01).

Characterization of stem-like properties in SP cells derived from NSP populations

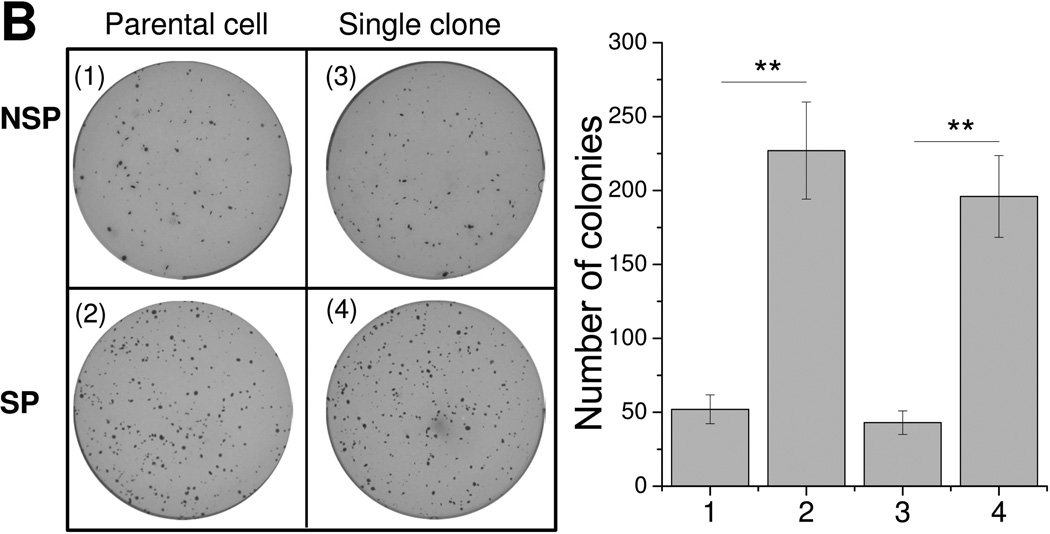

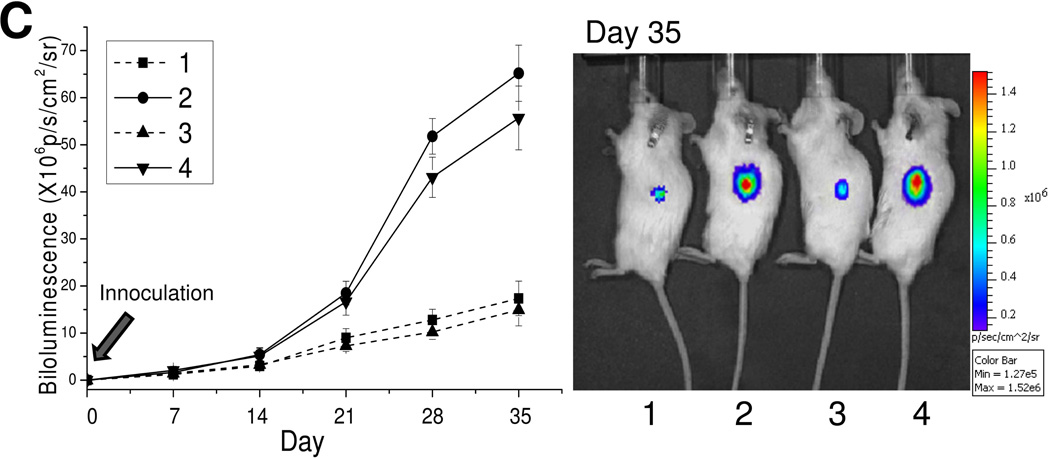

To determine whether the cells present in SPs derived from single-cell NSP clones still possess stem-like properties, we examined the mRNA expression of several pluripotency-associated genes (Sox2, Oct4, Nanog, Klf-4, c-Myc, and β-catenin).18, 27 NSP cells from 8 single-cell colonies were mixed evenly and studied together. The same was done for the SP cells. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis revealed that Oct4, Nanog, Sox2, c-Myc, Klf4, and β-catenin genes were expressed at a higher level in the SP populations isolated from the single-cell NSP colonies, as compared to their NSP counterparts from the same source, and were in line with the results obtained in the parental cells (Figure 4A). Next, we examined the in vitro colony formation potential of SP and NSP cells. As shown in Figure 4B, SP cells regenerated from colonies formed by sorted NSP cells formed 3-fold more colonies than their corresponding NSP cells. Similar results were observed in the parental cells (Figure 4B). Finally, to evaluate tumorigenicity, SP or NSP cells isolated from the 8 single-cell colonies or parental cells were inoculated subcutaneously into the flank of NOD/SCID IL2rg−/− mice. Similar to the results obtained with the parental cells, SP cells isolated from the 8 colonies exhibited a significantly higher tumorigenicity potential as compared to their corresponding NSP cells (Figure 4C). These results suggest that SP cells regenerated from purified NSP single-cell colonies still maintain the characteristics of cancer stem cells.

Figure 4. SP cells reconstituted from purified NSP cells maintain their CSC characteristics.

SP and NSP cell populations were purified from parental cells and NSP-G4-derived single-cell colonies (1, NSP from parental cells; 2, SP from parental cells; 3, NSP from 8 NSP-G4-derived single-cell clones; 4, SP from 8 NSP-G4-derived single-cell clones). (A) Quantitative real-time RT-PCR was performed for c-Myc, β-catenin, Klf4, Nanog, Sox2, and Oct4 and data are presented as mean ± s.d. of triplicate experiments (**P<0.01). (B) Colony formation assay. 5 × 103 sorted SP or NSP cells were resuspended in agar, seeded in a 6-well plate, and overlaid with complete culture medium. Representative images are shown from independent experiments (left panel), and data are presented as mean ± s.d. of triplicate experiments (**P<0.01) (right panel). (C) NOD/SCID IL2rg−/− mice (six mice per group) were injected subcutaneously with 0.1 × 106 SP or NSP cell fractions isolated from RPMI8226 GL cells. Cells were pre-mixed with Matrigel prior to injections and tumor engraftment was monitored weekly by whole-body bioluminescence imaging. Tumor signal intensity is shown (left panel) as mean of 6 mice ± s.d. Representative images from day 35 are shown in the right panel. The color intensity scale ranges from purple (low signal; low tumor burden) to red (high signal; high tumor burden).

Hypoxia regulates the balance between SP and NSP cells in MM cell culture

Taken together, these findings suggested that SP cells are maintained at a relatively constant level and that this stem-like fraction can be maintained by either SP or NSP cells (Figure 2C). These findings were somewhat puzzling to us, since prior reports established that cancer stem cells can be replenished through the de-differentiation of mature, non-stem, tumor cells only upon the introduction of exogenous genes or proteins.27 Since we had not employed these approaches in this study, our next question was whether the balance between the SP and NSP cells is instead regulated by their microenvironment. Clinical evaluation of the BM microenvironment in MM patients revealed hypoxic conditions,28, 29 so to mimic it, RPMI8226 and U266 cells were cultured in a hypoxic atmosphere (5% oxygen, 5% carbon dioxide, 90% nitrogen) for 5 days. As shown in Figure 5A, in RPMI8226 cells, exposure to hypoxia induced a greater than 5-fold increase of SP cell numbers, from 0.62% baseline to 3.27%. A similar result was obtained in U266 cells, 0.86% pre- to 4.19% post-hypoxia (Figure 5B). To validate their stem-like properties, SP cells from the hypoxia treatment groups were sorted and the expression profile of stem cell-associated genes was performed as described in Figure 4A. Additionally, we treated cultures MM cells with CoCl2 (final concentration 200 µmol/L) to artificially exert hypoxic conditions within cells. Following a 5-day treatment, change in the percentage of CSCs in culture was detected by flow cytometric analysis. As expected, hypoxic conditions induced by CoCl2 increased the SP population by nearly 4-fold over the baseline in both, RPMI8226 and U266 MM cells (Figure 5A and 5B). Based on these data, we further hypothesized that SP cells will have a higher potential of infiltrating a hypoxic BM environment. To test this, SP or NSP cells isolated form the RPMI8226 GL cell line, were inoculated into mice via the lateral tail vein and the number of GFP positive cells detected in the bone marrow after 3 weeks. As shown in Figure 5C, mice injected with SP cells exhibited a higher tumor burden than those that were injected with NSP cells, as well as revealed a significantly higher number of GFP positive cells in present in the bone marrow (23.9% versus 3.4%, p<0.01).

Figure 5. SP fraction in MM cells is regulated by hypoxia.

RPMI 8226 (A) and U266 (B) cells were treated with hypoxia (5% oxygen) or CoCl2 (200 µmol/L) for 5 days, followed by the Hoechst 33342-based CSC analysis. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments and are presented as mean ± s.d. of triplicate experiments (**P<0.01). (C) NOD/SCID IL2rg−/− mice (six mice per group) were injected via the lateral tail vein with 0.2 × 106 SP or NSP cells isolated from RPMI8226 GL cell line. After 3 weeks, tumor engraftment was confirmed by bioluminescence. At necropsy, bone marrow aspirates were collected and percentages of GFP-positive cells were determined by flow cytometry. Representative results are shown.

TGF-β1 is crucial for the hypoxia-induced de-differentiation of MM cells

Prior studies convincingly showed that TGF-β1 is involved in hypoxia-induced cellular behaviors.30 Therefore, we then explored whether TGF-β1 also plays a role in the hypoxia-induced increase of the SP population in myeloma cells. Quantitative PCR analysis revealed that TGF-β1 expression level was significantly up-regulated following a hypoxia treatment (Figure 6A). Moreover, pre-treatment of cells with SB431542, a potent and specific inhibitor of TGF-β1 kinase receptors largely reduced the hypoxia-induced increase in SP percentages (Figure 6B).

Figure 6. TGF-β1 is involved in the hypoxia-induced increase in the SP population.

RPMI 8226 cells were cultured under hypoxia (5% oxygen) or normoxia (20% oxygen) for 5 days. Quantitative real-time RT-PCR was performed for Tgf-β1 gene and data are shown as mean ± s.d. of triplicate experiments (**P<0.01). (B) RPMI8226 cells were pretreated with 0.01% DMSO or 0.5 µM SB431542 for 30 minutes prior to the 5-day hypoxia (5% oxygen) culture. After5 days, the Hoechst 33342-based CSC analysis was performed and data are presented as mean ± s.d. of triplicate experiments (**P<0.01). (C) A proposed model of SP fraction maintenance in heterogeneous MM cells. This balance is maintained by the alternating conversions between SP and NSP cells and can be affected by various factors.

Discussion

CSCs are a subpopulation of cancer cells that share the self-renewal and pluripotency characteristics with non-cancer stem cells.31 Presence of CSCs in a tumor is associated with radioresistance, chemoresistance, local invasion, and poor prognosis.4, 5, 32 Therefore, therapies targeting CSCs seem to be the next logical step in eradicating cancer.33–38 Divergent from the currently accepted unidirectional hierarchical model of cancer stem cells, several recent studies instead favor a bidirectional model.27, 30, 39 For example, melanoma cells can be de-differentiated to CSC-like cells by the transfection of the Oct4 gene or transmembrane delivery of the Oct4 protein.27 Moreover, Chaffer et al.39 has shown that mature breast cancer cells give rise to the CSC-like cells spontaneously and without genetic manipulation. These observations indicate that some cells present in the bulk of the tumor have the potential to switch to CSC-like cells.

In this study, we report that clonogenic MM SP cells arise from NSP cells without any additional stimuli other than the conventional cell culture, and that the percentage of SP cells can return to baseline after long-term culture. Importantly, these SP cells de-differentiated from the NSP population still possess the characteristics of MM stem cells. Expectantly, purified SP cells can generate NSP cells and restore the original SP fraction even faster. Collectively, our findings reveal that under certain conditions, SP and NSP cells are maintained in a balance in heterogeneous MM, and that this balance is maintained, at least partially, by the bi-directional conversion of SP and NSP cells. Hence, this cell population is dynamic and can be affected by extrinsic factors that have the ability to increase or decrease the percentage of SP cells (Figure 6C).

In vivo, MM cells closely interact with their neighboring cells, such as bone marrow stromal cells, fibroblasts, adipocytes, bone marrow endothelial cells, inflammatory cells, osteoblasts, and osteoclasts.40 We thus hypothesized that the SP balance may be directly affected by the interaction of MM and bone marrow cells, various cytokines and chemokines present in the BM microenvironment, or other physiologic microenvironmental factors, such as pH, oxygen saturation, or tissue stiffness. For the studies described herein, we chose to concentrate on hypoxia as one of the potential regulators of stemness. Hypoxia is an imbalance between the oxygen supply and consumption rates that deprives cells or tissues of sufficient oxygen.41 Previous studies have shown that a hypoxic microenvironment may promote preferential maintenance of cancer stem cells,42–44 and a number of recent studies provided valuable insights into the functional roles of hypoxia in MM disease progression.28, 29 Our current results indicate that hypoxia alters the dynamic balance of MM SP and increases the fraction of SP cells, which provides a better understanding into the hypoxic MM microenvironment. Mechanistically, there are many sequelae to a hypoxic stress, with one of them being modulation of the TGF-β signaling cascade. TGF-β is an essential regulator of numerous cellular processes, including proliferation, differentiation, migration, and cell survival.45 During hematopoiesis, the TGF-β signaling pathway is a potent suppressor of normal B-cell proliferation and immunoglobulin production.46 In multiple myeloma, TGF-β is secreted at high levels from both myeloma and bone marrow stromal cells.46 What’s more, recent studies have suggested that TGF-β1 may be involved in the hypoxia-promoted dissemination of MM cells via the epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT).28 In light of this, our results provide a novel role of TGF-β in the MM bone marrow microenvironment and show that TGF-β1 is crucial for hypoxia-induced increase of the SP cell fraction.

Our observations are in agreement with those by Piyush et al. that showed that in breast cancer, subpopulations of cells purified based on a given phenotypic condition over time returned to equilibrium.47 We also believe that the Markov model proposed in their study may be applicable in MM. Hence, further research is needed to understand the molecular mechanisms underlying the MM CSC maintenance. This is especially important in the context of therapeutic responses: as clearly outlined by Visavader et al.,48 a molecular switch from a mature, fully differentiated cancer cell to a more undifferentiated CSC may dampen therapeutic responses. Therefore, understanding molecular switches that regulate the CSC compartment will assist with designing better strategies aimed to eradicate cancer, and our results provide the first piece of the puzzle.

Supplementary Material

Novelty and impact.

The MM clonogenic side population (SP) cell percentages are balanced in heterogeneous cell populations. This balance is not fixed, but is instead regulated by environmental factors. We identified the transforming growth factor β1 as one of these factors that is involved in the hypoxia-induced stimulation of the balance. These data suggest that gaining a better understanding of the mechanisms that regulate SP reconstruction could facilitate design of novel therapeutic approaches that will control MM clonogenicity.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Zheng-Zheng Shi in HMRI Translational Imaging–Pre-Clinical Imaging Core and Dr. David Haviland in HMRI Flow Cytometry Core for technical support.

This study was supported by NIH grants R01CA151955, R33CA173382, and 5P50CA126752 to Y.Z.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors on this manuscript wish to disclose no conflict of interest.

Supplementary information is available at the International Journal of Cancer website.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Murray T, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2007. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57:43–66. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.57.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cruz RD, Tricot G, Zangari M, Zhan F. Progress in myeloma stem cells. Am J Blood Res. 2011;1:135–145. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pozzi S, Marcheselli L, Bari A, Liardo EV, Marcheselli R, Luminari S, Quaresima M, Cirilli C, Ferri P, Federico M, Sacchi S. Survival of multiple myeloma patients in the era of novel therapies confirms the improvement in patients younger than 75 years: a population-based analysis. Br J Haematol. 2013;163:40–46. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matsui W, Wang Q, Barber JP, Brennan S, Smith BD, Borrello I, McNiece I, Lin L, Ambinder RF, Peacock C, Watkins DN, Huff CA, et al. Clonogenic multiple myeloma progenitors, stem cell properties, and drug resistance. Cancer Res. 2008;68:190–197. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-3096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang Y, Shi J, Tolomelli G, Xu H, Xia J, Wang H, Zhou W, Zhou Y, Das S, Gu Z, Levasseur D, Zhan F, et al. RARalpha2 expression confers myeloma stem cell features. Blood. 2013;122:1437–1447. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-02-482919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arima Y, Hayashi N, Hayashi H, Sasaki M, Kai K, Sugihara E, Abe E, Yoshida A, Mikami S, Nakamura S, Saya H. Loss of p16 expression is associated with the stem cell characteristics of surface markers and therapeutic resistance in estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2012;130:2568–2579. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jakubikova J, Adamia S, Kost-Alimova M, Klippel S, Cervi D, Daley JF, Cholujova D, Kong SY, Leiba M, Blotta S, Ooi M, Delmore J, et al. Lenalidomide targets clonogenic side population in multiple myeloma: pathophysiologic and clinical implications. Blood. 2011;117:4409–4419. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-02-267344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kotoucek PP, Orfao A. Myeloma stem cell concepts, heterogeneity and plasticity of multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol. 2014 doi: 10.1111/bjh.12873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bonnet D, Dick JE. Human acute myeloid leukemia is organized as a hierarchy that originates from a primitive hematopoietic cell. Nat Med. 1997;3:730–737. doi: 10.1038/nm0797-730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Brien CA, Pollett A, Gallinger S, Dick JE. A human colon cancer cell capable of initiating tumour growth in immunodeficient mice. Nature. 2007;445:106–110. doi: 10.1038/nature05372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chiron D, Surget S, Maiga S, Bataille R, Moreau P, Le Gouill S, Amiot M, Pellat-Deceunynck C. The peripheral CD138+ population but not the CD138− population contains myeloma clonogenic cells in plasma cell leukaemia patients. Br J Haematol. 2012;156:679–683. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trepel M, Martens V, Doll C, Rahlff J, Gosch B, Loges S, Binder M. Phenotypic detection of clonotypic B cells in multiple myeloma by specific immunoglobulin ligands reveals their rarity in multiple myeloma. PLoS One. 2012;7:e31998. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hajek R, Okubote SA, Svachova H. Myeloma stem cell concepts, heterogeneity and plasticity of multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol. 2013;163:551–564. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matsui W, Huff CA, Wang Q, Malehorn MT, Barber J, Tanhehco Y, Smith BD, Civin CI, Jones RJ. Characterization of clonogenic multiple myeloma cells. Blood. 2004;103:2332–2336. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim D, Park CY, Medeiros BC, Weissman IL. CD19-CD45 low/− CD38 high/CD138+ plasma cells enrich for human tumorigenic myeloma cells. Leukemia. 2012;26:2530–2537. doi: 10.1038/leu.2012.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ho MM, Ng AV, Lam S, Hung JY. Side population in human lung cancer cell lines and tumors is enriched with stem-like cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:4827–4833. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Szotek PP, Pieretti-Vanmarcke R, Masiakos PT, Dinulescu DM, Connolly D, Foster R, Dombkowski D, Preffer F, Maclaughlin DT, Donahoe PK. Ovarian cancer side population defines cells with stem cell-like characteristics and Mullerian Inhibiting Substance responsiveness. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:11154–11159. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603672103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ikegame A, Ozaki S, Tsuji D, Harada T, Fujii S, Nakamura S, Miki H, Nakano A, Kagawa K, Takeuchi K, Abe M, Watanabe K, et al. Small molecule antibody targeting HLA class I inhibits myeloma cancer stem cells by repressing pluripotency-associated transcription factors. Leukemia. 2012;26:2124–2134. doi: 10.1038/leu.2012.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nara M, Teshima K, Watanabe A, Ito M, Iwamoto K, Kitabayashi A, Kume M, Hatano Y, Takahashi N, Iida S, Sawada K, Tagawa H. Bortezomib reduces the tumorigenicity of multiple myeloma via downregulation of upregulated targets in clonogenic side population cells. PLoS One. 2013;8:e56954. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wen J, Feng Y, Bjorklund CC, Wang M, Orlowski RZ, Shi ZZ, Liao B, O'Hare J, Zu Y, Schally AV, Chang CC. Luteinizing Hormone-Releasing Hormone (LHRH)-I antagonist cetrorelix inhibits myeloma cell growth in vitro and in vivo. Mol Cancer Ther. 2011;10:148–158. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wen J, Feng Y, Huang W, Chen H, Liao B, Rice L, Preti HA, Kamble RT, Zu Y, Ballon DJ, Chang CC. Enhanced antimyeloma cytotoxicity by the combination of arsenic trioxide and bortezomib is further potentiated by p38 MAPK inhibition. Leuk Res. 2010;34:85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2009.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goodell MA, Brose K, Paradis G, Conner AS, Mulligan RC. Isolation and functional properties of murine hematopoietic stem cells that are replicating in vivo. J Exp Med. 1996;183:1797–1806. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.4.1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kummalue T, Chuphrom A, Sukpanichanant S, Pongpruttipan T. Detection of monoclonal immunoglobulin heavy chain gene rearrangement (FR3) in Thai malignant lymphoma by High Resolution Melting curve analysis. Diagn Pathol. 2010;5:31. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-5-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Krieken JH, Langerak AW, Macintyre EA, Kneba M, Hodges E, Sanz RG, Morgan GJ, Parreira A, Molina TJ, Cabecadas J, Gaulard P, Jasani B, et al. Improved reliability of lymphoma diagnostics via PCR-based clonality testing: report of the BIOMED-2 Concerted Action BHM4-CT98-3936. Leukemia. 2007;21:201–206. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burack WR, Laughlin TS, Friedberg JW, Spence JM, Rothberg PG. PCR assays detect B-lymphocyte clonality in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded specimens of classical hodgkin lymphoma without microdissection. Am J Clin Pathol. 2010;134:104–111. doi: 10.1309/AJCPK6SBE0XOODHB. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wen J, Cheng HY, Feng Y, Rice L, Liu S, Mo A, Huang J, Zu Y, Ballon DJ, Chang CC. P38 MAPK inhibition enhancing ATO-induced cytotoxicity against multiple myeloma cells. Br J Haematol. 2008;140:169–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06895.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kumar SM, Liu S, Lu H, Zhang H, Zhang PJ, Gimotty PA, Guerra M, Guo W, Xu X. Acquired cancer stem cell phenotypes through Oct4-mediated dedifferentiation. Oncogene. 2012;31:4898–4911. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Azab AK, Hu J, Quang P, Azab F, Pitsillides C, Awwad R, Thompson B, Maiso P, Sun JD, Hart CP, Roccaro AM, Sacco A, et al. Hypoxia promotes dissemination of multiple myeloma through acquisition of epithelial to mesenchymal transition-like features. Blood. 2012;119:5782–5794. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-09-380410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martin SK, Diamond P, Gronthos S, Peet DJ, Zannettino AC. The emerging role of hypoxia, HIF-1 and HIF-2 in multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2011;25:1533–1542. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang H, Wu H, Zheng J, Yu P, Xu L, Jiang P, Gao J, Wang H, Zhang Y. Transforming growth factor beta1 signal is crucial for dedifferentiation of cancer cells to cancer stem cells in osteosarcoma. Stem Cells. 2013;31:433–446. doi: 10.1002/stem.1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clarke MF, Dick JE, Dirks PB, Eaves CJ, Jamieson CH, Jones DL, Visvader J, Weissman IL, Wahl GM. Cancer stem cells--perspectives on current status and future directions: AACR Workshop on cancer stem cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:9339–9344. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sun S, Wang Z. Head neck squamous cell carcinoma c-Met(+) cells display cancer stem cell properties and are responsible for cisplatin-resistance and metastasis. Int J Cancer. 2011;129:2337–2348. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lou H, Dean M. Targeted therapy for cancer stem cells: the patched pathway and ABC transporters. Oncogene. 2007;26:1357–1360. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tang C, Ang BT, Pervaiz S. Cancer stem cell: target for anti-cancer therapy. FASEB J. 2007;21:3777–3785. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-8560rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Frank NY, Schatton T, Frank MH. The therapeutic promise of the cancer stem cell concept. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:41–50. doi: 10.1172/JCI41004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Singh AK, Arya RK, Maheshwari S, Singh A, Meena S, Pandey P, Dormond O, Datta D. Tumor heterogeneity and cancer stem cell paradigm: Updates in concept, controversies and clinical relevance. Int J Cancer. 2014 doi: 10.1002/ijc.28804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ottinger S, Kloppel A, Rausch V, Liu L, Kallifatidis G, Gross W, Gebhard MM, Brummer F, Herr I. Targeting of pancreatic and prostate cancer stem cell characteristics by Crambe crambe marine sponge extract. Int J Cancer. 2012;130:1671–1681. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wen J, Li H, Tao W, Savoldo B, Foglesong JA, King LC, Zu Y, Chang CC. High throughput quantitative reverse transcription PCR assays revealing over-expression of cancer testis antigen genes in multiple myeloma stem cell-like side population cells. Br J Haematol. 2014 doi: 10.1111/bjh.12951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chaffer CL, Brueckmann I, Scheel C, Kaestli AJ, Wiggins PA, Rodrigues LO, Brooks M, Reinhardt F, Su Y, Polyak K, Arendt LM, Kuperwasser C, et al. Normal and neoplastic nonstem cells can spontaneously convert to a stem-like state. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:7950–7955. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102454108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Anderson KC, Carrasco RD. Pathogenesis of myeloma. Annu Rev Pathol. 2011;6:249–274. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu D, Lin P, Hu Y, Zhou Y, Tang G, Powers L, Medeiros LJ, Jorgensen JL, Wang SA. Immunophenotypic heterogeneity of normal plasma cells: comparison with minimal residual plasma cell myeloma. J Clin Pathol. 2012;65:823–829. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2012-200881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heddleston JM, Li Z, Lathia JD, Bao S, Hjelmeland AB, Rich JN. Hypoxia inducible factors in cancer stem cells. Br J Cancer. 2010;102:789–795. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Keith B, Simon MC. Hypoxia-inducible factors, stem cells, and cancer. Cell. 2007;129:465–472. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mazumdar J, Dondeti V, Simon MC. Hypoxia-inducible factors in stem cells and cancer. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13:4319–4328. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00963.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jakowlew SB. Transforming growth factor-beta in cancer and metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2006;25:435–457. doi: 10.1007/s10555-006-9006-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dong M, Blobe GC. Role of transforming growth factor-beta in hematologic malignancies. Blood. 2006;107:4589–4596. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-10-4169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gupta PB, Fillmore CM, Jiang G, Shapira SD, Tao K, Kuperwasser C, Lander ES. Stochastic state transitions give rise to phenotypic equilibrium in populations of cancer cells. Cell. 2011;146:633–644. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Visvader JE, Lindeman GJ. Cancer stem cells: current status and evolving complexities. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:717–728. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.