Abstract

Background

Mipomersen is an antisense oligonucleotide that inhibits apolipoprotein (apo) B synthesis and lowers plasma low density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol even in the absence of LDL receptor function, presumably due to the inhibition of hepatic production of triglyceride-rich very low density lipoprotein (VLDL) particles. By virtue of this mechanism, mipomersen therapy commonly results in the development of hepatic steatosis. Because this is frequently accompanied by alanine aminotransferase (ALT) elevations, concern has arisen that mipomersen could promote the development of steatohepatitis, which could in turn lead to fibrosis and cirrhosis over time.

Objective

The objective of this study was to assess the liver biopsy findings in patients treated with mipomersen.

Methods

We describe 7 patients who underwent liver biopsy during the mipomersen clinical development programs. Liver biopsies were reviewed by a single, blinded pathologist.

Results

The histopathological features were characterized by simple steatosis, without significant inflammation or fibrosis.

Conclusion

These findings suggest that hepatic steatosis due to mipomersen is distinct from non-alcoholic steatohepatitis.

Keywords: Liver, VLDL, LDL, apolipoprotein B, cholesterol, triglycerides, fibrosis, inflammation, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, steatohepatitis, antisense oligonucleotide

Introduction

Mipomersen is an antisense oligonucleotide that inhibits apolipoprotein B (apoB) synthesis by complexing with the apoB mRNA and leading to cleavage by ribonuclease H.1 The reduction of apoB mRNA synthesis appears to decrease the rate of triglyceride-rich VLDL production. This leads to reductions in plasma total cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, non-HDL cholesterol, apoB and lipoprotein(a).2 Importantly, mipomersen lowers plasma LDL-cholesterol concentrations in hypercholesterolemic patients who are being treated with maximally-tolerated lipid-lowering therapy, including those with homozygous and heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia (FH).3–8

Because the secretion of VLDL particles is integral to maintaining triglyceride balance within the liver, hepatic steatosis represents a potential mechanism-based consequence of mipomersen therapy.4 In keeping with this possibility, mipomersen-associated increases in hepatic triglycerides have been quantified using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or spectroscopy (MRS), with liver fat contents that are inversely correlated with reductions in plasma apoB-100 concentrations.3,4 When observed in association with increased transaminase levels, this raised the concern that mipomersen therapy may lead to liver changes similar to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), which carries a significant risk of progression to cirrhosis. Here we report the clinical and histological features of patients undergoing mipomersen therapy.

Methods

In the phase 2 and 3 clinical development and open-label extension programs for mipomersen, 7 patients underwent liver biopsy as a component of their clinical care and at the discretion of the physician. In order to standardize the histopathologic findings, all biopsy slides were reviewed by a single experienced hepatopathologist (R.D.O.), who was not affiliated with any of the study centers. We note that the biopsies for cases 1 and 2 were previously reported4, but these were re-evaluated with the 5 additional biopsies that were performed in our current mipomersen-treated patients. To complement case histories, Table 1 summarizes the responses of plasma LDL and apoB concentrations, ALT values, intrahepatic triglyceride (IHTG) contents and timing of liver biopsy in patients treated with mipomersen. Table 2 summarizes the histologic findings for each biopsy.

Table 1.

Biochemical responses and timing of liver biopsy in mipomersen-treated patients*

| Case | Rx (weeks) |

Max ALT, (week) |

Biopsy week |

Baseline LDL-c (mg/dL) |

Final LDL-c (mg/dL |

Baseline apoB (mg/dL) |

Final apoB (mg/dL) |

Initial IHTG % (week) |

IHTG on treatment % (week) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1† | 25 | 126 (36) | 22 | 209 | 85 | 146 | 77 | 17.8 (4) | 34.7 (18) |

| 2† | 26 | 160 (28) | 21 | 167 | 56 | 126 | 40 | 23.7 (11) | 47.3 (30) 27.0 (50) |

| 3 | 35 | 103 (28) | 34 | 94 | 23 | 90 | 28 (28) 31 (36) |

2.5 (1) | 33.9 (28) 36.1 (36) |

| 4 | 52 | 126 (52) | 47 | 121 | 52 | 113 | 46 | 2 (1) | 23.6 (44) |

| 5 | 100 | 94 (43) | 73 | 264 | 124 | 171 | 92 | 36.7 (52) | 35.8 (100) |

| 6 | 159 | 79 (129†) | 159‡ | 562 | 376 | 349 | 221 | <1 (39) | <1 (156) |

| 7 | 60 | 200 (26) | 56 | 195 | na§ | 126 | na§ | 5.6 | na§ |

Abbreviations: LDL-c, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; apoB, apolipoprotein B; IHTG, intrahepatic triglyceride

Biopsy previously reported, but reanalyzed as part of this study.4

This patient was treated with mipomersen for 104 weeks, followed by a 28 week hiatus, and then treated for 55 more weeks.

na – Values are not available because the patients remains enrolled in a blinded study.

Table 2.

Summary of Histologic Findings

| Case | Portal* Inflammation |

Lobular Inflammation |

Sinusoidal Lymphocytosis |

Hepatocyte Necrosis |

Steatosis | Fibrosis | Kupffer Cell Hyperplasia |

Regenerative Changes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0 | Present | Present |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0 | Present | Present |

| 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | Present | Present |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | Present | Present |

| 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | Present | Present |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Absent | Present |

| 7 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Present | Present |

Histologic features were graded on a semi-quantitative integer scale of 0 (none present) to 4 (maximally present).

Results

Case 1

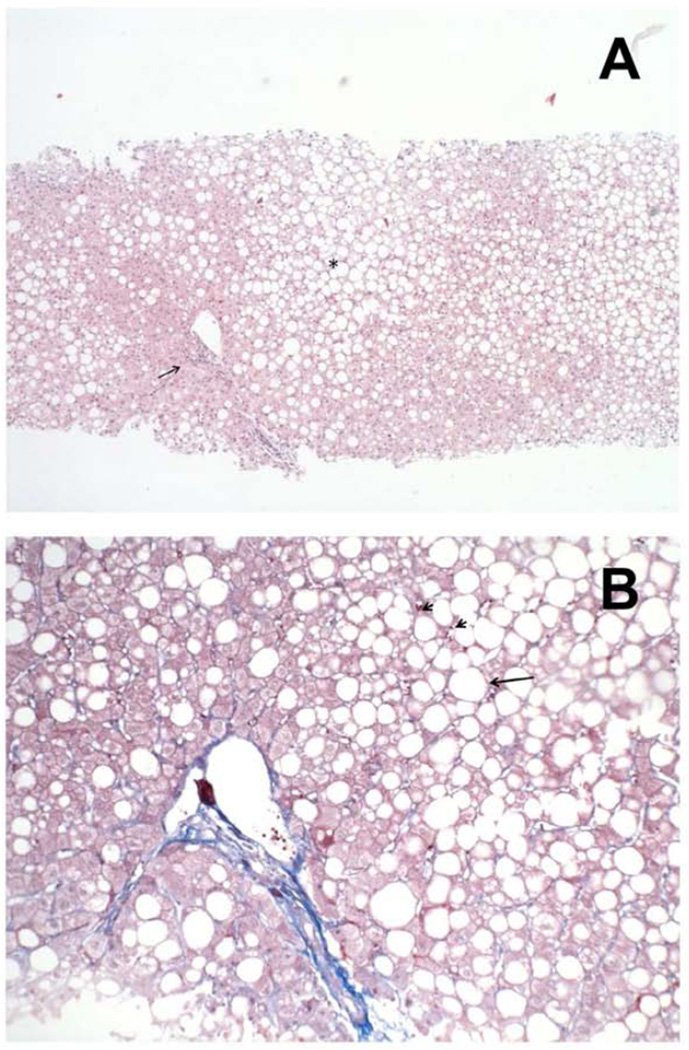

A 59 year-old white male with coronary artery disease, as evidenced by a myocardial infarction requiring percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), and hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, as well as impaired fasting glucose was randomized to receive 200 mg mipomersen weekly as part of a 26-week double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 study.4 He was intolerant of statins due to myalgias and was not receiving other lipid-lowering medications. The patient had a long history of alcohol abuse and consumed the maximum allowable intake of 12 drinks per week throughout the study. His ALT was 37 U/L at baseline. In response to an increase in IHTG content from 17.8% in week 4 to 34.7% as determined by MRS during week 184, liver biopsy was performed at treatment week 22. As shown in Figure 1, this revealed severe macrosteatosis without lobular inflammation or fibrosis. At week 25, treatment was permanently discontinued due to moderate flu-like symptoms, which were attributed to the study drug. The IHTG contents at weeks 26 and 52 were 42.0% and 28.4%, respectively. At the time mipomersen was discontinued, the ALT was 80 U/L, peaked at 126 U/L at week 36, and fell to 57 U/L (<1.5 ULN) at week 58.

Figure 1. Severe steatosis without inflammation or fibrosis in a patient treated with mipomersen for 22 weeks (Case 1).

Low (A) and high power (B) image of a patient treated with Mipomersen. At low power (A), the liver shows marked, predominantly macrovesicular, steatosis in zone 3 and zone 2 of the liver lobules (asterisk), and a mild patchy mononuclear infiltrate in the portal tract (arrow). At high power (B), the liver parenchyma shows macrovesicular steatosis (arrow) and a few scattered mononuclear cells in the liver sinusoids (arrowhead), but an absence of liver cell necrosis or steatohepatitis.

Case 2

A 58 year-old white male with hypercholesterolemia and coronary artery disease, as evidenced by a myocardial infarction requiring PCI, was randomized to receive 200 mg mipomersen weekly as part of a 26-week double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 study.4 He was intolerant of statins due to myalgias and was instead receiving colesevelam 625 mg daily. This patient had been consuming 10 alcoholic drinks per week during the study. His ALT was normal at baseline and increased progressively during treatment, peaking at 160 U/L at week 28. In response to ALT increase to >2 ULN at week 11, an MRI was performed and showed an IHTG content of 23.7 %. A liver biopsy was performed at treatment week 21 and revealed severe macrosteatosis with mild focal lobular inflammation and no fibrosis4. The patient completed all 26 weeks of mipomersen. The IHTG content peaked at 47.3% at week 30 and decreased to 27.0% at week 50. The ALT was 125 U/L at week 24, 160 U/L at week 28, and 54 U/L (<1.5 ULN) at week 50.

Case 3

A 62 year-old white female with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, and type 2 diabetes was randomized to receive mipomersen 200 mg weekly as part of a 13-week double-blind, placebo-controlled study, followed by weekly open-label mipomersen.3 She received atorvastatin 10 mg daily concurrently and was consuming one alcoholic drink per week during the study. Her ALT was 10 U/L at the time of enrollment. Liver biopsy was performed at treatment week 34 in order to evaluate an increase in IHTG content by MRS from 2.5% at baseline to 33.9% at week 28, and an elevated ALT, which peaked at 103 U/L at week 28. The biopsy revealed severe macrosteatosis without lobular inflammation or fibrosis. Mipomersen treatment was nevertheless discontinued at week 35 due to concerns of possible drug-related liver injury. During the post-treatment follow-up period, both IHTG content and ALT progressively declined, reaching 18.4% and 24 U/L, respectively, at post-treatment week 20. The IHTG content further declined to 6.0% at post-treatment week 50.

Case 4

A 64 year-old white female with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia and type 2 diabetes mellitus was randomized to receive mipomersen 200 mg weekly as part of a 13-week double-blind, placebo-controlled study, followed by weekly open-label mipomersen to evaluate the safety and efficacy of extended dosing.3 She received simvastatin 20 mg daily concurrently and was consuming 3 drinks per week during the study. Due to increasing IHTG content by MRS (2.0% at baseline to 15.6% and 13.6% at weeks 28 and 44, respectively) and to a rise in ALT (from 23 IU/L at screening to 99 U/L at week 44), liver biopsy was performed at treatment week 47. This revealed severe macrosteatosis, but without evidence of lobular inflammation or fibrosis. The patient completed the treatment period (52 weeks). During the post-treatment follow-up period, both IHTG content and ALT improved, reaching 15.7% and 53 U/L, respectively, at post-treatment week 12. ALT fell to 28 IU/L at post-treatment week 19.

Case 5

A 60 year-old white male with severe heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia leading to premature coronary artery disease and PCI was randomized to receive mipomersen 200 mg weekly for 26 weeks, and then enrolled into an open-label treatment extension study of weekly mipomersen to evaluate the safety and efficacy of extended dosing.7,8 He was concurrently receiving rosuvastatin 20 mg daily, ezetimibe 10 mg daily, fenofibrate 160 mg daily and fish oil. This patient did not consume any alcohol during the study. Liver biopsy was performed at treatment week 74 for evaluation of abdominal pain and ultrasound finding of hepatic steatosis. The biopsy showed severe macrosteatosis without lobular inflammation or fibrosis. His ALT had peaked at 94 IU/L at treatment week 43 but was normal at the time of the biopsy. He continued to receive mipomersen for nearly two years.

Case 6

A 48 year-old white female with homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia was randomized to receive mipomersen at a reduced dose of 160 mg weekly due to weight < 50 kg during a 26-week double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial of mipomersen, and then enrolled into an open-label treatment extension study of weekly mipomersen at 200 mg per week.5,8 She did not consume any alcohol during the study. She was concurrently receiving atorvastatin 80 mg daily and ezetimibe 10 mg daily. The IHTG content by MRI was normal at baseline and throughout the study, and ALT remained < 2 × ULN. Liver biopsy was performed due to prolonged (159 weeks) exposure to mipomersen and revealed mild steatosis without lobular inflammation or fibrosis.

Case 7

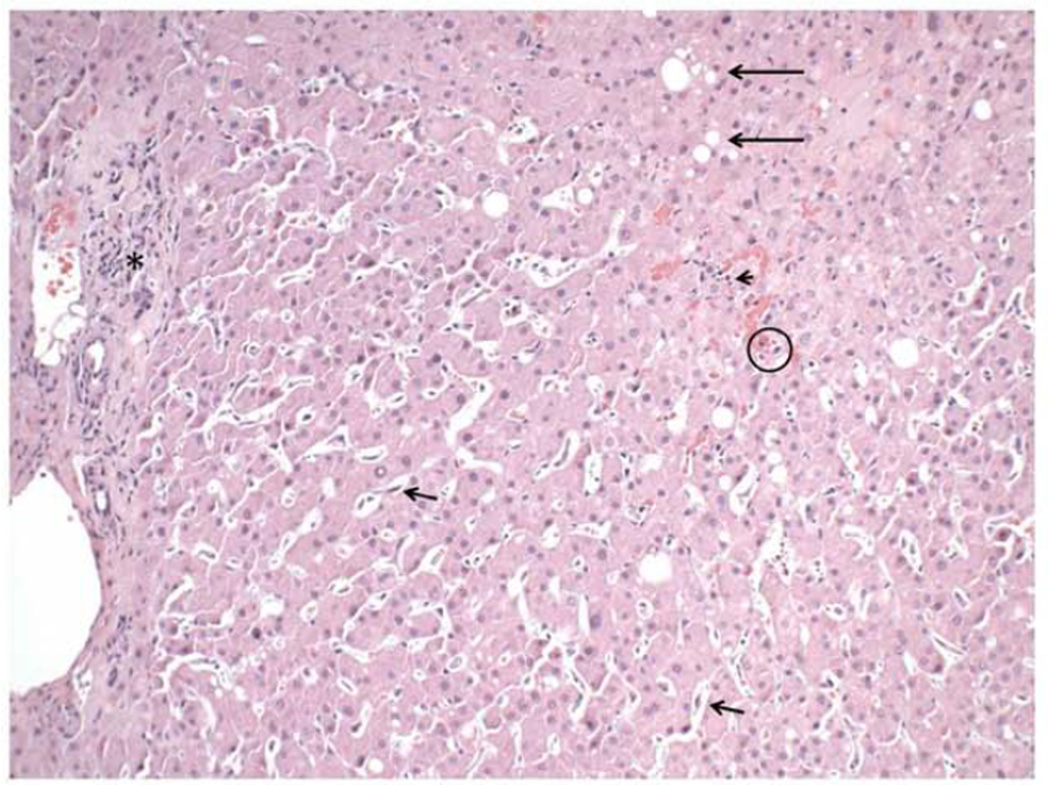

A 45 year-old white male with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia was randomized to receive mipomersen during a phase 3, double-blind, placebo-controlled study followed by an open-label continuation period to assess the safety and efficacy of two different regimens of mipomersen (clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01475825). He was receiving simvastatin 40 mg daily and niacin 1000 mg daily at study initiation. This patient consumed one alcoholic drink daily throughout the study. Liver biopsy was performed at treatment week 56 for evaluation of persistently elevated ALT (≥ 3× ULN) for more than 3 months and ultrasound showing fatty liver. As shown in Figure 2, this revealed mild macrovesicular and focal microvesicular steatosis with focal lobular inflammation and no fibrosis. Of note, the patient had opted not to take mipomersen during weeks 41–47, and had taken it every other week during weeks 51–59, without informing the investigators. Treatment was stopped at the study conclusion (week 60). His ALT peaked at 200 IU/L at treatment week 26 but decreased to 68 U/L at the time of biopsy. The results of all lipid studies and MRIs remain blinded as part of this ongoing study.

Figure 2. Mild macrovesicular and focal microvesicular steatosis with focal mild portal and lobular inflammation and no fibrosis in a patient treated with mipomersen for 56 weeks (Case 7).

Liver biopsy in one patient in this study treated with mipomersen showed only a mild degree of macrovesicular steatosis (long arrows). Instead, the findings were prominent sinusoidal mononuclear inflammation (arrowhead), spotty hepatocyte necrosis (O), regenerative changes (binucleated cells, prominent nucleoili, anisonucleosis), and Kupffer cell hyperplasia (short arrows). Also note the mild focal degree of mononuclear inflammation in the portal tract (asterisk).

Discussion

Since increasing plasma clearance of LDL by statin therapy is not feasible in homozygote FH patients who lack functional LDL receptors and is often incomplete in heterozygotes, therapies with the potential to reduce the rate of VLDL secretion represent an attractive alternative for reducing plasma concentrations of pro-atherogenic lipoproteins. This is because LDL particles are formed in the plasma primarily by the intravascular catabolism of apolipoprotein B-100-containing VLDL particles, which are secreted by the liver and transport triglyceride molecules to muscle and adipose tissue. VLDL is assembled within hepatocytes when apoB-100 is co-translationally lipidated with triglycerides by the action of microsomal triglyceride transfer protein (MTP). Following secretion into plasma by the liver, triglyceride-rich VLDL is remodeled into LDL principally by the activity of lipoprotein lipase in the capillary endothelia of muscle and adipose tissue, as well as hepatic lipase on the surface of hepatocytes.

The secretion of VLDL particles appears to be effectively inhibited by two different pharmacologic approaches, each of which has led to FDA-approved therapies for homozygous FH.9 Whereas mipomersen is an antisense oligonucleotide that reduces apoB-100 production, lomitapide is a small molecule inhibitor of MTP. Both medications reduce LDL substantially, but both also lead to an increase in IHTG contents in many patients who receive these therapeutic agents, presumably by reducing the export of triglycerides from the liver via VLDL. Elevations in transaminase values have been observed with both mipomersen2,5–7 and lomitapide10,11 and assessments of hepatic steatosis have been made based on MRS and MRI. Since these non-invasive techniques only assess the presence and quantity of fat, it remains unclear whether the mechanism-based accumulation of hepatic triglycerides associated with therapies that reduce VLDL secretion leads to simple steatosis or steatohepatitis (i.e. steatosis associated with inflammation and fibrosis).

In order to address this issue, we evaluated liver histopathology in 7 patients treated with mipomersen (for 23 to 159 weeks) who underwent liver biopsy. In 6 individuals (cases 1–5 and 7), biopsies were performed due to concerns about elevations in transaminases and liver triglyceride concentrations. In one instance (case 6), a liver biopsy was performed because the patient had been treated for an extended period of time. In all but 2 patients (cases 2 and 7), the histopathologic findings were characterized by steatosis, without inflammation or fibrosis. In case 6, where the biopsy was performed after 159 weeks of therapy, mild steatosis without inflammation or fibrosis was observed. The average maximal ALT (mean ± SEM) was 3.0 ± 0.4 UNL. The average increase in IHTG content was 15.8 ± 5.6. Flu-like symptoms and injection site reactions each occurred in 4 cases.

These results suggest that steatosis induced by mipomersen therapy is not associated with liver cell injury. The same features are observed for the majority of patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) in whom the liver histopathology is characterized by simple steatosis (non-alcoholic fatty liver, NAFL), and the clinical course is benign. Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) develops in a minority of NAFLD patients, and is characterized by lobular inflammation, fibrosis and ballooning degeneration of hepatocytes, as well as progressive disease that may culminate in cirrhosis. In this study, only mild lobular inflammation was present in 2 patients (cases 2 and 7). NASH is more commonly associated with certain metabolic risk factors, including obesity and type 2 diabetes.12 NAFLD is characterized by increased rates of VLDL secretion, but these are insufficient to compensate for increases in IHTG concentrations, which are attributable to increased hepatic lipogenesis and uptake of plasma free fatty acids.13 By contrast, the pathogenesis of hepatic steatosis in familial hypobetalipoproteinemia (FHBL) is more closely related to what occurs with mipomersen therapy: FHBL is caused primarily by truncation mutations of the apoB gene, which lead to decreased VLDL production, leading to impaired export of triglycerides and hepatic steatosis.14 Despite the presence of severe hepatic steatosis in FHBL, fibrosis and cirrhosis have only rarely been reported. Moreover, in a study that compared the liver findings in patients with NAFLD and hepatitis C infection, hepatic steatosis in FHBL was associated with a lower grade of inflammation and a lower stage of fibrosis, and insulin resistance was absent.15 These findings support the concept that hepatic fat accumulation associated with apoB inhibition may reflect a distinct metabolic condition compared to NAFLD.15,16 Suggestive of hepatic adaptation to reduced triglyceride secretion, liver enzymes and IHTG contents measured by MRI have tended to decrease and stabilize after 1 year of mipomersen therapy.2,8

Our study has important limitations. Liver biopsies were performed at the discretion of the treating physicians at each study center, and only in a small minority of patients who had increased liver fat on imaging or elevated serum transaminases. Baseline liver biopsies were not performed prior to treatment and most biopsies were performed after a relatively short duration of exposure (< 2 years). It is possible that patients who had early discontinuation of mipomersen due to significant ALT elevations but without liver biopsy, also had more severe liver injury. Although steatohepatitis did not develop in the 2 patients who received mipomersen for at least 2 years, the effect of long duration therapy on the liver was not determined in our small sample. It is possible that steatohepatitis due to inhibition of VLDL secretion could require substantially more time to develop.17

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that in the majority of cases steatosis without inflammation results from apoB inhibition, similar to what is generally observed in patients with FHBL.

Highlights.

Mipomersen therapy reduces LDL cholesterol in the absence of LDL receptors.

Mipomersen therapy commonly leads to hepatic steatosis.

Liver biopsies on mipomersen-patients primarily revealed simple hepatic steatosis.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: The work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants R37 DK48873 and R01 DK56626 to D.E.C.

Abbreviations

- ApoB

apolipoprotein B

- FH

familial hypercholesterolemia

- FHBL

familial hypobetalipoproteinemia

- IHTG

intrahepatic triglyceride

- MRS

magnetic resonance spectroscopy

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- MTP

microsomal triglyceride transfer protein

- NAFLD

non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

- NAFL

non-alcoholic fatty liver

- NASH

non-alcoholic steatohepatitis

- PCI

percutaneous coronary intervention

- ULN

upper limit of normal

- LDL

low-density lipoprotein

- VLDL

very low-density lipoprotein

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest: R.D.S has received consulting fees and/or honoraria for speaking from Astra Zeneca, Aegerion, Amgen, Biolab, Bristol Myers Squibb, Genzyme, Sanofi/Regeneron, Boehringer Ingelheim, Unilever, Merck, Pfizer and Novartis. D.E.C. has received consulting fees from Aegerion, Dignity Sciences, Genzyme, Intercept, Merck, and Novartis, and has additionally received honoraria from Merck.

M.P.M. is an employee of Genzyme, a Sanofi Company, Cambridge, MA

References

- 1.Akdim F, Visser ME, Tribble DL, Baker BF, Stroes ES, Yu R, Flaim JD, Su J, Stein EA, Kastelein JJ. Effect of mipomersen, an apolipoprotein B synthesis inhibitor, on low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in patients with familial hypercholesterolemia. Am J Cardiol. 2010;105:1413–1419. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomas GS, Cromwell WC, Ali S, Chin W, Flaim JD, Davidson M. Mipomersen, an apolipoprotein B synthesis inhibitor, reduces atherogenic lipoproteins in patients with severe hypercholesterolemia at high cardiovascular risk: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:2178–2184. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.07.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Visser ME, Akdim F, Tribble DL, Nederveen AJ, Kwoh TJ, Kastelein JJ, Trip MD, Stroes ES. Effect of apolipoprotein-B synthesis inhibition on liver triglyceride content in patients with familial hypercholesterolemia. J Lipid Res. 2010;51:1057–1062. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M002915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Visser ME, Wagener G, Baker BF, Geary RS, Donovan JM, Beuers UH, Nederveen AJ, Verheij J, Trip MD, Basart DC, Kastelein JJ, Stroes ES. Mipomersen, an apolipoprotein B synthesis inhibitor, lowers low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in high-risk statin-intolerant patients: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:1142–1149. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raal FJ, Santos RD, Blom DJ, Marais AD, Charng MJ, Cromwell WC, Lachmann RH, Gaudet D, Tan JL, Chasan-Taber S, Tribble DL, Flaim JD, Crooke ST. Mipomersen, an apolipoprotein B synthesis inhibitor, for lowering of LDL cholesterol concentrations in patients with homozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;375:998–1006. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60284-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stein EA, Dufour R, Gagne C, Gaudet D, East C, Donovan JM, Chin W, Tribble DL, McGowan M. Apolipoprotein B synthesis inhibition with mipomersen in heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to assess efficacy and safety as add-on therapy in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2012;126:2283–2292. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.104125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGowan MP, Tardif JC, Ceska R, Burgess LJ, Soran H, Gouni-Berthold I, Wagener G, Chasan-Taber S. Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of mipomersen in patients with severe hypercholesterolemia receiving maximally tolerated lipid-lowering therapy. PLoS One. 2012;7:e49006. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Santos RD, Duell PB, East C, Guyton JR, Moriarty PM, Chin W, Mittleman RS. Long-term efficacy and safety of mipomersen in patients with familial hypercholesterolaemia: 2-year interim results of an open-label extension. Eur Heart J. 2013 doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht549. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rader DJ, Kastelein JJ. Lomitapide and mipomersen: two first-in-class drugs for reducing low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in patients with homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia. Circulation. 2014;129:1022–1032. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.001292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cuchel M, Bloedon LT, Szapary PO, Kolansky DM, Wolfe ML, Sarkis A, Millar JS, Ikewaki K, Siegelman ES, Gregg RE, Rader DJ. Inhibition of microsomal triglyceride transfer protein in familial hypercholesterolemia. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:148–156. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cuchel M, Meagher EA, du Toit Theron H, Blom DJ, Marais AD, Hegele RA, Averna MR, Sirtori CR, Shah PK, Gaudet D, Stefanutti C, Vigna GB, Du Plessis AM, Propert KJ, Sasiela WJ, Bloedon LT, Rader DJ. Efficacy and safety of a microsomal triglyceride transfer protein inhibitor in patients with homozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia: a single-arm, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2013;381:40–46. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61731-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paredes AH, Torres DM, Harrison SA. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Liver Dis. 2012;16:397–419. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2012.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen DE, Fisher EA. Lipoprotein metabolism, dyslipidemia, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Semin Liver Dis. 2013;33:380–388. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1358519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tanoli T, Yue P, Yablonskiy D, Schonfeld G. Fatty liver in familial hypobetalipoproteinemia: roles of the APOB defects, intra-abdominal adipose tissue, and insulin sensitivity. J Lipid Res. 2004;45:941–947. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M300508-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lonardo A, Lombardini S, Scaglioni F, Carulli L, Ricchi M, Ganazzi D, Adinolfi LE, Ruggiero G, Carulli N, Loria P. Hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance: does etiology make a difference? J Hepatol. 2006;44:190–196. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Visser ME, Lammers NM, Nederveen AJ, van der Graaf M, Heerschap A, Ackermans MT, Sauerwein HP, Stroes ES, Serlie MJ. Hepatic steatosis does not cause insulin resistance in people with familial hypobetalipoproteinaemia. Diabetologia. 2011;54:2113–2121. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2157-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sacks FM, Stanesa M, Hegele RA. Severe hypertriglyceridemia with pancreatitis: thirteen years' treatment with lomitapide. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:443–447. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.13309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]