Abstract

Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs) that secrete primarily pancreatic polypeptide (PP) are rare and usually nonfunctional. There are approximately two-dozen reports of PP-secreting PNETs, and three that have been associated with diabetes mellitus (DM). None suggest a mechanism for the association between PP-secreting PNETs and DM. We describe five patients with PP-producing tumors who were diagnosed with DM at the same time as their PNETs, review the literature on PP, and consider its role in the pathophysiology of diabetes mellitus. The cases discussed were extracted from our surgical neuroendocrine tumor database. We examined all patients with PP-predominant PNETs—both with DM (n=5) and without (n=8). The five patients with DM at the time of PNET diagnosis demonstrated improvement or resolution of their DM post-operatively. In the patients with PP-secreting PNETs but no diagnosis of DM pre-operatively, one became hypoglycemic post-operatively, and two others developed post-operative DM. The five cases discussed in detail raise the question of whether the hypersecretion of PP in PNETs might be an important event leading to the development of diabetes mellitus. Although the literature does not provide a mechanism for this association, it may be related to the role of PP in hepatic glucose regulation.

Keywords: Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors, Pancreatic Polypeptide, Diabetes Mellitus

Introduction

Pancreatic polypeptide (PP) is a 36 amino acid hormone that, in humans, is secreted from PP cells located primarily in the head and uncinate process of the pancreas. It was initially isolated from chickens in 1968, from humans in 1972, and found to be associated with some pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors in 1978.1 Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs) that secrete only PP are rare and generally considered nonfunctional, as their presence is not usually associated with clinical syndromes.2 The most consistent presenting symptom associated with these tumors is abdominal pain, which can be ascribed to the tumor’s size and location, rather than the secretion of PP itself.2 There are a few reports of PPomas being associated with watery diarrhea syndrome, diabetes mellitus, or gastric ulcers, but these findings are inconsistent and the specific role that PP plays in the etiology of each has not been elucidated.

There have been approximately two dozen reports of PPomas in the literature, three of which have been associated with diabetes mellitus. In two cases, the PPomas were associated with other hormonal abnormalities, and in the third case, the search for the tumor was initiated by the new onset of diabetes.3–5 This patient had metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis, underwent treatment with streptozocin and had her diabetes brought under control with oral hypoglycemic medications.5 None of these reports suggest a mechanism for the association between PPoma and diabetes.

We describe five patients with elevated PP and PNETs who were diagnosed with diabetes at approximately the same time as their PNETs. Two had complete surgical resection and near or total cure of their diabetes mellitus, and three underwent debulking with improved control of their diabetes in two cases. We also review the literature on PP and consider its role in the pathophysiology of diabetes mellitus.

Case 1

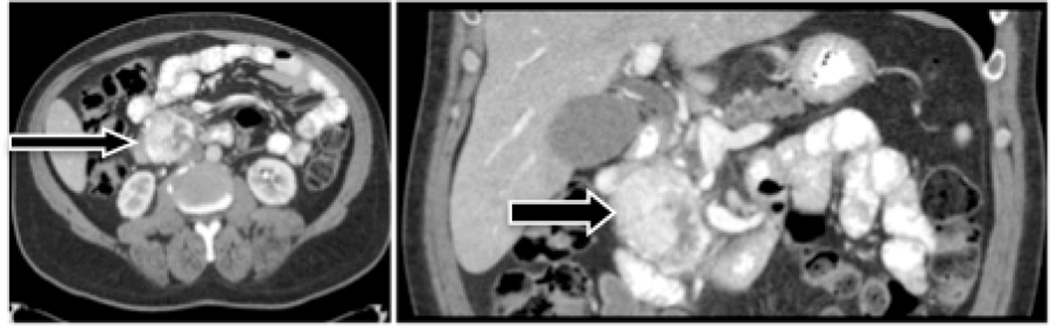

Patient 1 was referred to our clinic for surgical management of a 7 cm pancreatic mass that was found incidentally on CT during work up for ureteral calculi and bilateral nephrolithiasis. At his initial clinic visit, he reported a 70 lb. weight loss and a new diagnosis of diabetes mellitus—both within the last six months. His pertinent demographic and tumor related information is summarized in Table 1. No metastases were identified on the CT scan (Figure 1), and endoscopic ultrasound-guided biopsy of the mass was suspicious for a neuroendocrine tumor. His pre-operative PP was 31,100 pg/ml (Table 1). He underwent pancreatoduodenectomy, which revealed negative margins and 0 of 7 positive lymph nodes. Surgical pathology demonstrated a 7.4 cm, well-differentiated pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor.

Table 1. Demographic information and neuroendocrine tumor marker levels for patients with PNETs (PPoma) and diabetes mellitus.

Post-op tumor marker levels are the first values measured after the surgery — measured one to three months post-operatively. Immunohistochemical staining for pancreatic polypeptide was completed for four of the primary PNETs. The percentage reflects the approximate percentage of D cells comprising the tumor.

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | Case 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis | 52 | 68 | 42 | 53 | 58 |

| Sex | M | M | F | M | F |

| Pre-op DM | Dx near the time of NET Dx | Dx near the time of NET Dx | Dx at the time of MENI Dx | Dx near the time of NET Dx | Dx near the time of NET Dx |

| Post-op DM | Improvement | Cure | Improvement | No change | Improvement |

| Tumor size (cm) | 7.4 | 2.6 | 0.8 (head), 0.8 (body) | 6.3 | 3.3 |

| Location in pancreas | Head | Tail | Head, body | Tail | Tail |

| Metastases (location) | No | No | Yes (liver) | Yes (liver) | Yes (liver, LN) |

| Operation | R0 | R0 | R2 | R2 | R2 |

| Pre-op PP (0 – 435 pg/ml) | 31,100 | 527 | 1,070 | 25,675 | 59,700 |

| Post-op PP | 53 | 424 | 217 | 3,200 | |

| Pre-op serotonin (50 – 200 ng/ml) | 361 | 17 | 179 | 58 | 202 |

| Post-op serotonin | 448 | 37 | 116 | 254 | |

| Pre-op chromogranin A (0 – 95 ng/ml) | 97 | 52 | < 200 | 202 | |

| Post-op chromogranin A | 68 | < 5 | < 200 | 213 | |

| Pre-op pancreastatin (0 – 135 pg/ml) | 172 | 22 | 33 | 3,380 | 457 |

| Post-op pancreastatin | 117 | 36 | 43 | 144 | |

| Pre-op gastrin (0 – 100 pg/ml) | 34 | 18 | 69 | 153 | |

| Post-op gastrin | 93 | ||||

| Pre-op insulin (2.6 – 24.9 uU/ml) | 2.9 | 7.5 | 9.3 | 29.3 | |

| IHC PP staining | < 75% | 1% | 1 – 5% | 0% | Not analyzed by staining |

Figure 1. Pre-operative CT scan of Patient #1.

Transaxial (left) and coronal (right) views show an enhancing, 7.4 cm tumor in the head of the pancreas. Final pathology classified the tumor as grade II, well differentiated.

Prior to surgery, he had required more than 50 units of exogenous insulin per day for glucose control. In the immediate post-operative week, he required a total of 8 units of exogenous insulin. He was discharged on the seventh post-operative day without any insulin or oral hypoglycemic medications. At his two-week follow-up visit, he produced a record of daily blood glucose levels in the 130 to 145 mg/dL range without any insulin supplementation. One month post-operatively, he was using approximately 8 units of insulin per week and at two months, 20 units per week. In this span of time, he had unintentionally lost approximately 12 kg, or 10% of his body weight. His BMI went from 29 kg/m2 to 28 kg/m2. His PP decreased to 53 pg/ml four weeks post-operatively, and was <30 pg/ml one year post-operatively. His HbA1c went from 7.2% 6 months post-operatively to 6.4% one year after surgery.

Case 2

Patient 2 presented to his local emergency room for chest pain, where his workup included a CT scan, which incidentally found an isolated tumor in the tail of the pancreas. No metastases were identified in the chest or abdomen. Biopsy of the mass demonstrated a well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumor of the pancreas. Neuroendocrine tumor markers are summarized in Table 1. Distal pancreatectomy, splenectomy and cholecystectomy were performed and surgical pathology revealed a 2.6 cm well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumor with negative margins and 0 of 5 positive lymph nodes. The patient recovered well, and eight months post-operatively his PP had decreased from mild elevation pre-operatively to normal levels (424 pg/ml). At one year follow-up, he had no evidence of recurrence or metastasis by CT scan.

Pre-operatively, he carried a diagnosis of “borderline” diabetes type II and had been taking metformin for glucose control. It is unknown when he was first diagnosed with diabetes, but clinic notes from one and three years prior to the diagnosis of the neuroendocrine tumor do not mention oral hypoglycemics or diabetes, nor did they document use of metformin. Three years prior to surgery, his HbA1c was 6.2%. It therefore appears that the diagnosis was made less than one year before the discovery of the neuroendocrine tumor. At his three month follow-up, he continued to use metformin at the same dose as he had pre-operatively, but by six months he no longer required the drug and had normal blood glucose measurements, despite not having made any significant lifestyle changes or weight loss (his weight had decreased 1 kg, which was 2% of his body weight). At his last clinic appointment 20 months post-operatively, his blood glucose levels remained normal without medication and his PP level was 450pg/ml. His HbA1c at this time was 6.6%, down from 7.5% about one year after surgery. He had unintentionally lost 7.5 kg, or 7.6% of his body weight since surgery. He maintained a BMI of 29 kg/m2.

Case 3

Patient 3 is a member of a MEN1 family, and was found to have hyperparathyroidism in 1994. In that same year, she was diagnosed with diabetes mellitus. She admitted at the time of diagnosis that she did not follow a structured diet or exercise plan. She had a neck exploration and subtotal parathyroidectomy performed for parathyroid hyperplasia. Shortly thereafter, she had elevated prolactin levels and a pituitary microadenoma was discovered on imaging; she was started on bromocriptine at this time. In 2002, a pancreatic mass was discovered, as well as hepatic metastases. This mass was reported to have been associated with elevated PP, although the exact value is unknown since these records could not be obtained from the outside hospital. Treatment at that time was enucleation of the pancreatic mass. She was referred to our clinic after recurrence of her pancreatic tumor was discovered between 2002 and 2007 (the exact date of diagnosis is unknown), when we performed our operation. Her presenting symptoms had been epigastric pain, nausea and vomiting, and her diabetes continued to be poorly controlled. Her PP at that time (2007) was 1070 (normal range < 435 pg/ml), and other neuroendocrine tumor markers are summarized in Table 1.

We performed a wedge excision of a liver lesion, radiofrequency ablation (RFA) of multiple large liver lesions, cholecystectomy, and enucleation of pancreatic head and body tumors. Several pancreatic lesions less than 0.5 cm were left in place. Final pathology of the pancreatic lesions demonstrated two 0.8 cm well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumors. PP four months post-operatively was 517 pg/ml and at six months was 217 pg/ml. Prior to surgery, she was using glipizide, lantus, metformin and sliding scale insulin to manage her blood glucose. Her blood glucose levels averaged in the 270s and HbA1c one year prior to surgery was 10.3%. Ten months post-operatively her hemoglobin A1c was 10%. Interestingly, her PP achieved its nadir approximately 3.5 years after our surgery (198 pg/ml) and her HbA1c also reached its lowest recorded value at 7.5%. Her DM regimen at this time included lantus, metformin and insulin with meals, but she was no longer taking glipizide. Her BMI at time of surgery was 33 kg/m2, and in 2012 was 39 kg/m2.

Case 4

Patient 4 was diagnosed with a pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor (from a liver biopsy) after multiple liver masses were seen on a CT scan that was obtained during an emergency room workup for malaise, nausea, and vomiting. He was evaluated in our clinic five months after his diagnosis, and at that time was noted to have multiple metastases to the spine and liver. He reported he was diagnosed with diabetes at the same time he was diagnosed with a PPoma. Throughout his battle with cancer, he maintained his blood glucose with metformin, glyburide and sliding scale insulin. There were no changes in this regimen for the time span that we knew him. His PP, measured two months prior to his initial clinic visit, was 25,675 pg/ml. His other NET markers are summarized in Table 1. Two years after his initial presentation to our clinic, we performed distal pancreatectomy, splenectomy, cholecystectomy and RFA of liver lesions in an attempt to decrease his tumor burden and improve his symptoms. The pancreatic lesion was found to be a 6.3 cm neuroendocrine carcinoma, moderately-differentiated with free margins, but positive for vascular invasion. Metastatic carcinoma was also found in 3 of 18 lymph nodes. There was no change in his diabetes post-operatively. He had lost 8.6 kg, or 11.6% of his body weight at two months post-operatively, and succumbed to his disease thereafter, although the exact date is unknown as he never returned to our clinic for follow up. His BMI was 25 kg/m2 at the time of his surgery.

Case 5

Patient 5 was diagnosed with metastatic low-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma by CT-guided liver biopsy in 2007. At the time of diagnosis, the CT scan failed to show an obvious primary, but did demonstrate a large tumor burden in the liver. For many years, she was treated with Sandostatin and her disease remained clinically stable. In 2012, she developed palpable hepatomegaly and an ultrasound demonstrated significant change in size of the hepatic index lesion. She was referred to our clinic for consideration of tumor debulking. An MRI was done, which demonstrated abnormal appearing lobular tissue within the pancreatic tail. Tissue was obtained via EUS-guided biopsy and the pathology revealed a well-differentiated neuroendocrine neoplasm. A distal pancreatectomy, splenectomy, cholecystectomy, left lateral segmentectomy, multiple wedge resections and RFA of multiple liver lesions were performed for debulking purposes. We estimate that approximately 80% of her tumor burden was debulked at surgery. Her pre-operative PP was 59,700 pg/ml, and BMI was 45.2. The remainder of her measured NET markers are summarized in Table 1.

She reported that around the same time that she was found to have neuroendocrine cancer, she was also diagnosed with type II diabetes mellitus. She was started on oral hypoglycemics for blood glucose control. Pre-operatively, her fasting blood glucose was 275 mg/dL and she was taking high doses of glimepiride and metformin. Her weight around that time was 128 kg. Post-operatively, her blood glucose levels averaged 150 mg/dL and she had stopped taking metformin. Her weight at her most recent clinic visit was 136 kg, BMI 44.7, and PP decreased to 3,200 pg/ml.

Discussion

Pancreatic polypeptide release is functionally associated with increased satiety, delayed gastric emptying, inhibition of gallbladder motility, and regulation of energy expenditure.6 High basal levels of PP are seen with prolonged fasting, increased age, uncontrolled DM, and exercise,7 though its precise role in these pathways is unknown. PP is released postprandially in a biphasic manner. The first elevation is thought to be driven by protein ingestion and subsequent cholinergic stimulation of the pancreas. The second elevation occurs via humoral stimulation and vagal activity.1 PP has been considered a surrogate marker for parasympathetic activity in humans, as elevated levels are seen with electrical stimulation of the vagus and with administration of parasympathomimetics like pyridostigmine. PP secretion can be attenuated by truncal vagotomy or injection of atropine.8,9

PP deficiency is seen in the context of pancreatic resection and chronic pancreatitis.10 In both of these situations PP cell mass is decreased and abnormally high hepatic glucose production is noted, even in the context of physiologic endogenous insulin responses.11 In a rat model using a monoclonal antibody to inhibit PP action, the basal rate of hepatic glucose production became significantly elevated compared to controls.12

Diabetes mellitus does not drastically alter the body’s response to PP. The major difference in PP secretion seen in diabetic versus nondiabetic patients is that the former have higher basal level secretion of PP. Diffuse PP cell hyperplasia has been suggested as, and refuted as, the cause of increased PP secretion in experiments1,13 but studies detailing differences in PP cell mass in the islets of Langerhans in nondiabetic versus diabetic patients are lacking. Diabetic patients demonstrate similar biphasic PP responses to meals as nondiabetic patients do, suggesting that their pancreatic capacity for PP secretion is not significantly altered by the disease.14 Parasympathetic blockade by atropine in diabetics decreases PP secretion in a dose dependent manner, as it does in nondiabetic controls.9 Diabetic patients also demonstrate abnormally high hepatic glucose production in the face of PP deficiency, just as nondiabetic patients do.10

The five cases we describe were extracted from our surgical neuroendocrine tumor database, which consists of 72 patients diagnosed with PNETs that had operations to resect or debulk their disease. Of these 72 patients with PNETs, 40 were tested pre-operatively for PP. Fourteen of 40 had elevated PP, and eight of these fourteen had PP greater than two times normal. Five patients had documented diabetes at the time of diagnosis and are the cases described above. An R0 resection was achieved in two of the five cases. One of these patients had drastic improvement of their DM immediately after surgery and is now maintained with only a few units of insulin per week, and the other saw a dramatic improvement in their blood glucose control once the NET was excised, though this happened over a span of months. The three cases in which an R0 resection was not possible consisted of tumor debulking or enucleation to alleviate symptoms. These patients continued to have diabetes post-operatively. Two of the three saw initial improvement of their DM. They remained on oral hypoglycemics as well as insulin. Interestingly, multiple follow up notes mention that their blood glucose control became more difficult to manage as their tumor burden increased. The other (Patient 4) did not show dramatic improvement, but analysis is hampered by a lack of follow-up data. This patient only returned for his first post-operative appointment.

Eight patients with PNETs, elevated PP, but without DM are summarized in Table 2. The common feature between these patients is that all had metastatic disease, thus none achieved R0 resections. Patient A had the highest pre-operative PP level and, interestingly, as PP levels declined he developed issues with recurrent hypoglycemia. This suggests that for patients with alterations of blood glucose control, changes in the relative levels of PP may have effects on glucose control as do high absolute levels, as seen in Patient 2.

Table 2. Demographic information and neuroendocrine tumor marker levels for patients with PNETs and elevated PP, but without a diagnosis of DM.

Post-operative tumor marker levels are the first values measured after the surgery — generally measured three months post-operatively.

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis | 55 | 39 | 41 | 47 | 72 | 76 | 52 | 64 |

| Sex | M | F | M | F | F | F | F | F |

| Pre-op DM | NONE | NONE | NONE | NONE | NONE | NONE | NONE | NONE |

| Post-op DM | Progressively hypoglycemic | NONE | New DM | NONE | NONE | NONE | NONE | NONE |

| Tumor size (cm) | 4.5 cm | 2.5 cm | 5.9 cm | 7.2 cm | 2.3 cm | 5.6 cm | 5.5 cm | |

| Location in pancreas | Tail | Multiple (MENI) | Multiple (MENI) | Tail | Tail | Tail | Tail | Body |

| Metastases (location) | Yes (Liver) | Yes (LN) | Yes | Yes (Widely: carcinomatosis) | Yes (Liver, Stomach, Spleen) | Yes (LN) | Yes (LN, Liver) | Yes (LN) |

| Operation | R2 | R0 | Likely R1 | R2 | R1 | R1 | R2 | R2 |

| Pre-op PP (0 – 435 pg/ml) | 58,700 | 3,680 | 6,800 | 800 | 884 | 480 | 481 | 5,400 |

| Post-op PP | 2,430 | 1,140 | 181 | |||||

| Pre-op serotonin (50 – 200 ng/ml) | 154 | 21 | 45 | 162 | 91 | 102 | ||

| Post-op serotonin | 202 | 11 | 251 | |||||

| Pre-op chromogranin A (0 – 95 ng/ml) | 125 | 67 | 17 | 63 | 93 | |||

| Post-op chromogranin A | 27 | <5 | ||||||

| Pre-op pancreastatin (0 – 135 pg/ml) | 225 | 59 | 146 | 77 | 18,800 | 28 | 1175 | 152 |

| Post-op pancreastatin | 80 | 75 | 160 | 41 | ||||

| Pre-op gastrin (0 – 100 pg/ml) | 42 | 96 | 74 | 26 | 29 | |||

| Post-op gastrin | 30 | 16 |

Patient C developed post-operative hyperglycemia after his PNETs were excised. He had a known malignant insulinoma and elevated PP levels. The manifestation of DM after insulinoma excision is rare, but has been described previously. The most recent published case describes a patient nearly identical to our own, who had no history of pre-operative DM, had a malignant insulinoma excised and developed DM type II post-operatively, which was eventually controlled with oral hypoglycemic agents. The suggested mechanism for this phenomenon is the development of insulin resistance due to abnormally high caloric intake, stimulated by hypoglycemia. The insulin resistance is masked by the functioning tumor, but is overtly manifest after its excision.15 Our patient had a BMI of 40 pre-operatively, and so could potentially fit this hypothesis.

The five patients discussed in detail in this paper raise an interesting question as to whether the hypersecretion of PP caused by neuroendocrine tumors can be an upstream event leading to the development of diabetes mellitus. Four of five cases discussed lend support to this hypothesis because after these tumors were excised, PP levels decreased and the diabetes improved. We found it interesting that neither the initial levels, nor the absolute decrease in PP after surgery correlated with the severity of the DM or its subsequent improvement. The PP literature seems to support this observation, as elevated plasma PP levels may arise not only from PP cells found within certain functioning endocrine tumors, but also from hyperplastic PP cells in extra-tumoral pancreatic tissue behaving in a “reactionary” manner to either the major peptide secreted by a functioning pancreatic tumor (e.g. VIP-oma, Gastrinoma), or as a non-specific reaction of pancreatic tissue to injury.16 To examine this phenomenon for ourselves, four of the tumors excised at our institution were analyzed by immunohistochemical staining. The staining results are listed in Table 1 and it can be seen that the relative amount of PP cell staining in each tumor fails to correlate with the magnitude of the elevation of PP pre-operatively. This finding is supported in the literature as Larsson et al. suggest that there does not appear to be a relationship between the number of PP cells and their function, since islet tumors containing subnormal, normal, or supranormal concentrations of PP (when compared to normal pancreas) may be associated with normal or high levels of circulating PP.17

Another consideration for altered blood glucose metabolism in these patients relates to their surgical procedures. It is well described in the bariatric literature that Roux-en-Y gastric bypass has a positive impact on glucose metabolism, and can frequently lead to cure of non-insulin dependent diabetes. This could be related to both caloric restriction and changes in incretin hormones.18,19 Patient 1 underwent pancreatoduodenectomy without pylorus preservation for his PNET and demonstrated immediate cure of his DM followed by long term overall improvement compared to his pre-operative blood glucose control. A number of studies demonstrate that in the context of pancreatic adenocarcinoma, tumor resection (pancreatoduodenectomy) in diabetic patients can improve their blood glucose control. It has been speculated that a tumor-associated diabetogenic factor could be responsible for the diabetes that often accompanies pancreatic adenocarcinoma, but a specific factor has not been described to date.20 Improvement in blood glucose after pancreatoduodenectomy could also be due to changes in incretin levels from loss of the duodenum, mimicking the situation in Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Whether this contributed to the improvement of diabetes in Patient 1 is unclear, but it certainly would not have played a role in Patient 3 (enucleation) or Patients 2, 4, and 5, who all had distal pancreatectomies.

Unfortunately, a thorough examination of the literature does not provide an adequate explanation of how elevated PP levels in those with PNETs might cause DM. It seems reasonable that it could be related to PP’s role in hepatic glucose regulation, as three of five of the patients discussed here demonstrated normal insulin secretion, and none in the study of Quin et al. had abnormal insulin secretion. One patient did have slightly elevated insulin levels (Patient 4), but did not have symptoms suggestive of an insulinoma, and thus his elevated PP level may have been incidental. Clearly, to better understand the pathophysiological mechanism, further studies will be required to determine the role of PP in glucose tolerance.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest or funding.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lonovics J, Devitt P, Watson LC, et al. Pancreatic polypeptide. Arch Surg. 1981;116:1256–1264. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1981.01380220010002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuo S, Gananadha S, Scarlett C, et al. Sporadic pancreatic polypeptide secreting tumors (PPomas) of the pancreas. World J Surg. 2008;32:1815–1822. doi: 10.1007/s00268-008-9499-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manche A, Wood SM, Adrian IE, et al. Pancreatic polypeptide and calcitonin secretion from a pancreatic tumour—clinical improvement after hepatic artery embolization. Postgrad Med J. 1983;59:313–314. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.59.691.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kakanome C, Koizumi M, Fujiyah H, et al. Somatostatin syndrome accompanied by overproduction of pancreatic polypeptide. J Exp Med. 1984;142:201–210. doi: 10.1620/tjem.142.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Quin JD, Marshall DA, Fisher BM, et al. Metastatic pancreatic polypeptide producing tumour presenting with diabetes mellitus. Scot Med J. 1991;36:143. doi: 10.1177/003693309103600506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tseng P, Wu M, Kao J. Recent advances in clinical application of gut hormones. J Formos Med Assoc. 2010;109:859–861. doi: 10.1016/S0929-6646(10)60132-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vinik AI, Strodel WE, Eckhauser FE, et al. Somatostatinomas, PPomas, neurotensinomas. Seminars in Oncology. 1987;14.3:263–281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwartz TW, Holst JJ, Fahrenkrug J, et al. Vagal, cholinergic regulation of pancreatic polypeptide secretion. J Clin Invest. 1978;61:781–789. doi: 10.1172/JCI108992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vozarova de Courten B, Weyer C, Stefan C, et al. Parasympathetic blockade attenuates augmented pancreatic polypeptide but not insulin secretion in Pima indians. Diabetes. 2004;53:663–671. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.3.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sun YS, Brunicardi FC, Druck P, et al. Reversal of abnormal glucose metabolism in chronic pancreatitis by administration of pancreatic polypeptide. Am J Srg. 1986;151:130–140. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(86)90023-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seymour NE, Brunicardi FC, Chaiken RL, et al. Reversal of abnormal glucose production after pancreatic resection by pancreatic polypeptide administration in man. Surgery. 1988;104:119–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wong HC, Andersen DK, Sternini C, et al. Production of rat pancreatic polypeptide-specific monoclonal antibody and its influence on glucose homeostasis by in vivo immunoneutralization. Hybridoma. 1995;14:369–376. doi: 10.1089/hyb.1995.14.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Floyd JC, Jr, Fajans SS, Pek S, et al. A newly recognized pancreatic polypeptide; plasma levels in health and disease. Recent Prog Horm Res. 1977;33:519–570. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-571133-3.50019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Layer P, Go VLW, DiMagno EP. Carbohydrate digestion and release of pancreatic polypeptide in health and diabetes mellitus. Gut. 1989;30:1279–1284. doi: 10.1136/gut.30.9.1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ademoglu E, Unluturk U, Agbaht K, et al. Type 2 diabetes mellitus in a patient with malignant insulinoma manifesting after surgery. Diabet Med. 2012;29:133–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2012.03603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwartz TW. Pancreatic polypeptide (PP) and endocrine of the pancreas. Scand J Gastro. 1979;53:93–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Larsson L-I, Sundler F, Hakenson R. Pancreatic polypeptide: A postulated new hormone: Identification of its cellular storage site by light and electron microscopic immunocytochemistry. Diabetologia. 1976;12:211–226. doi: 10.1007/BF00422088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pories WJ, Swanson MS, MacDonald KG, et al. Who would have thought it? An operation proves to be the most effective therapy for adult-onset diabetes mellitus. Ann Surg. 1995;222:339–350. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199509000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Naslund E, Hellstrom PM. Elucidating the mechanisms behind the restoration of euglycemia after gastric bypass surgery. Diabetes. 2013;62:1012–1013. doi: 10.2337/db12-1690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sato N, Yamaguchi K, Yokohata K, et al. Changes in pancreatic function after pancreatoduodenectomy. Am J Surg. 1998;176:59–61. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(98)00105-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]