Abstract

Objectives To assess the risk of on-screen death of important characters in children’s animated films versus dramatic films for adults.

Design Kaplan-Meier survival analysis with Cox regression comparing time to first on-screen death.

Setting Authors’ television screens, with and without popcorn.

Participants Important characters in 45 top grossing children’s animated films and a comparison group of 90 top grossing dramatic films for adults.

Main outcome measures Time to first on-screen death.

Results Important characters in children’s animated films were at an increased risk of death compared with characters in dramatic films for adults (hazard ratio 2.52, 95% confidence interval 1.30 to 4.90). Risk of on-screen murder of important characters was higher in children’s animated films than in comparison films (2.78, 1.02 to 7.58).

Conclusions Rather than being the innocuous form of entertainment they are assumed to be, children’s animated films are rife with on-screen death and murder.

Introduction

Recent research suggests that as visual media has become more pervasive in modern society, children’s enculturation is increasingly likely to come from television and movies,1 2 including their understanding of death.3 By the age of 10, most children have developed a complete understanding of death as irreversible, permanent, and inevitable.4 Before this age, however, many children may have only a partial understanding of death as they lack the cognitive maturity to comprehend this concept.4

Exposure to on-screen death and violence can be frightening to young children and can have intense and longlasting effects.5 This might be particularly problematic when children have not been prepared, through candid discussion with parents or caring adults, to face these themes.6 These caregivers are crucial contributors to the development of children’s understanding of death. As child mortality rates have decreased over recent centuries, however, death has become an increasingly taboo subject for discussion with children.3 7 Adults might instead seek to protect children from the subject of death by using metaphorical language—such as speaking of a loved one who has died as “passed away” or “gone.” This might prohibit children from developing a mature understanding of death,8 potentially leaving them unprepared to face the subject on screen.

On-screen deaths can be particularly traumatic for children as they directly expose them to loss of life.6 Death, often gruesome and sensationalized, is featured prominently in North American films.9 Most parents take care to protect their children from the endemic gore and carnage present in movies aimed at adult audiences. Indeed, the current system of movie ratings to classify the age appropriateness of films devised by the Motion Picture Association of America was intended to allow parents to protect their children from content deemed inappropriate for young viewers.9 Films rated “G-general audience” are judged to contain no content “that could be offensive to children of any age.”10 Consequently, it would be expected that these films would provide children a viewing experience devoid of the rampant horrors often present in popular films with stricter ratings.

We used survival analysis techniques to examine time to on-screen death of important characters in animated children’s films versus those in films targeted at adult audiences. We hypothesized that, in contrast to containing no offensive content, children’s animated films are in fact rife with death and destruction.

Methods

Animated films

The primary exposure group for this study consisted of the 45 children’s animated films with the highest all-time box office gross revenue, indexed for inflation.11 Films were included if they received a genre tag of “animation” by the Internet Movie Database12 and received a film rating of “G-general audience” or “PG-parental guidance suggested.”13 We excluded films in which the main characters were neither humans nor animals (for example, cars, robots, toys), as the concept of mortality among inanimate yet anthropomorphized characters is unclear. Sequels were also excluded because important characters might have already died in a previous film. Film release dates ranged from 1937 (Snow White) to 2013 (Frozen).

Comparison films

The comparison films consisted of the two highest box office grossing films in the same year of release as each animated film, excluding sequels, that received a genre tag of “drama” by the Internet Movie Database.12 We reasoned that these films were more likely to be viewed solely by adult audiences. In cases in which more than one animated film for a given release year was included, we also selected the next two top grossing dramatic films of that year (for instance, third and fourth) for comparison. We excluded films that were additionally tagged with “action” or “adventure” because they are often also marketed to, and viewed by, young children. The comparison group nevertheless included a range of subgenres, including horror (for example, The Exorcism of Emily Rose, What Lies Beneath) and thriller (for example, Pulp Fiction, The Departed, Black Swan). A complete list of animated films and their comparisons is in the appendix.

Outcomes measured

Our primary outcome was the elapsed time of the film at which the first on-screen death of an important character occurred. An important character was defined as a main character, a friend or family member of a main character, or the main villain or nemesis in the film. As secondary outcomes, observers also noted two contextual factors as these could be particularly traumatic for children: instances in which the first on-screen death was a murder (excluding death in wartime combat); and, instances when the first on-screen death was of a parent of a main character. In four cases (two animated and two comparison films), a non-permanent death was noted (that is, the character was later revived). We included these as outcome events as witnessing such deaths on screen might be traumatic to young children, irrespective of whether or not they are later reversed. Nevertheless, removal of these cases as death did not change the pattern of results nor their significance. Trained research assistants collected data collection using a standardized coding protocol. A panel of experienced (amateur) film critics (IC, MK, MW) resolved ambiguous or unclear events by consensus.

Statistical analysis

We used Cox regression to examine the effect of type of film (animated versus comparison) on time elapsed at first on-screen death. To account for the fact that children’s films are often shorter than films for adults, we included total runtime as a covariate. Survival curves presented are based on these Cox regressions, adjusted for total runtime. The proportional hazards assumption was tested with the procedure developed by Therneau and Grambsch (test of non-zero slope of Schoenfeld residuals),14 and the assumption held (χ2=0.71, P=0.40). Finally, we included years since release and the interaction between film type and years since release as covariates to investigate whether films are becoming more or less deadly over time.

Data analysis was carried out with SPSS 21.0.15

Results

Two thirds of children’s animated films contained an on-screen death of an important character compared with half of comparison films (table 1). Common causes of death in children’s animated films included animal attacks and falls (intentional or not), while in comparison films common causes of death were gunshots, motor vehicle crashes, and illnesses. Notable early on-screen deaths included Nemo’s mother being eaten by a barracuda 4 minutes and 3 seconds into Finding Nemo, Tarzan’s parents being killed by a leopard 4 minutes and 8 seconds into Tarzan, and Cecil Gaines’ father being shot in front of him 6 minutes into The Butler.

Table 1.

Characteristics of animated and comparison films and details of deaths of important characters

| Children’s animated films (n=45) | Comparison films (n=90) | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean runtime | 1:29:29 | 2:05:08 |

| Median survival time (95% CI) | 1:19:15 (1:13:08 to 1:25:22) | 2:04:05 (1:44:39 to 2:23:31) |

| No of films with death by cause: | ||

| Gunshot | 3 (6.7) | 13 (14.4) |

| Drowning | 3 (6.7) | 1 (1.1) |

| Animal attack | 5 (11.1) | 0 |

| Killed in combat | 0 | 3 (3.3) |

| Motor vehicle crash (includes aircraft) | 1 (2.2) | 8 (8.9) |

| Mystical causes | 3 (6.7) | 0 |

| Defenestration or other fall | 5 (11.1) | 3 (33) |

| Stabbing/impalement | 2 (4.4) | 2 (2.2) |

| Illness/medical complications | 2 (4.4) | 8 (8.9) |

| Suicide | 0 | 1 (1.1) |

| Other injury | 2 (4.4) | 2 (2.2) |

| Other murder | 4 (8.9) | 4 (4.4) |

| No on screen death | 15 (33.3) | 45 (50) |

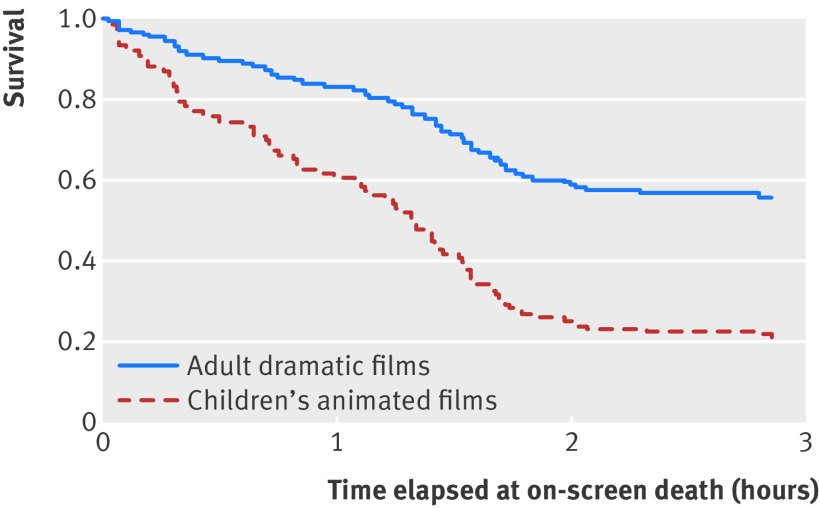

Figure 1 shows survival curves for important characters in animated and comparison films. After adjustment for total runtime and years since release, the risk of on-screen death of important characters was higher in children’s animated films than in comparison films (hazard ratio 2.52, 95% confidence interval 1.30 to 4.90). The interaction between film type and years since release was not a significant predictor of mortality (P=0.16).

Fig 1 Survival curves for important characters in animated versus comparison films

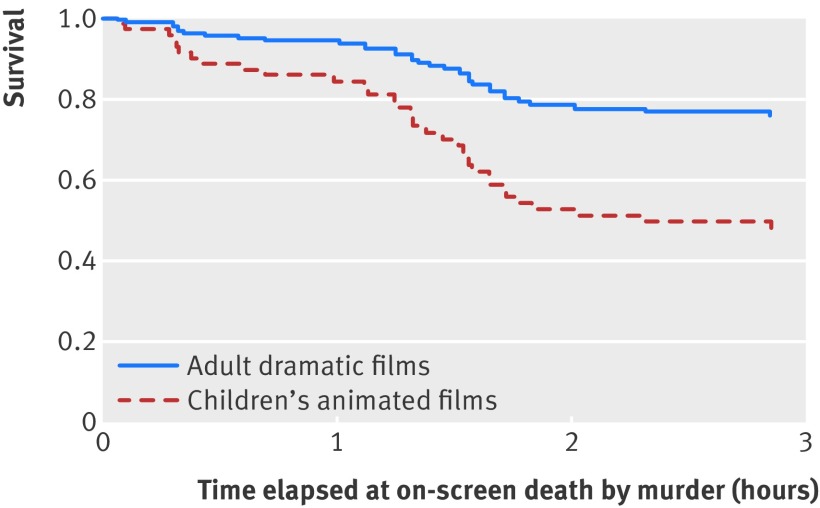

The risk of on-screen murder of important characters was higher in children’s animated films than in comparison films. After adjustment for total runtime and years since release the hazard ratio was 2.78 (95% confidence interval 1.02 to 7.58; fig 2). The interaction between film type and years since release was not a significant predictor of murder (P=0.18).

Fig 2 Survival curves for important characters in animated versus comparison films for death by murder

Table 2 presents details of casualties in children’s animated films versus comparison films, listed according to relationship to main protagonist. Our data suggested that parents, nemeses, and children were more often victims of the first on-screen death in children’s animated films, whereas the first casualty in adult dramatic films was more often the main protagonist themselves.

Table 2.

Numbers (percentage) of casualties in sample films by relationship to protagonist

| Casualties | Children’s animated films (n=45) | Comparison films (n=90) |

|---|---|---|

| Main protagonist* | 1 (2.2) | 14 (15.6) |

| Parent of protagonist* | 8 (17.8) | 6 (6.7) |

| Mother | 4 (8.9) | 3 (3.3) |

| Father | 1 (2.2) | 3 (3.3) |

| Both | 3 (6.7) | 0 |

| Spouse/romantic interest | 3 (6.7) | 6 (6.7) |

| Child* | 2 (4.4) | 0 |

| Other family | 1 (2.2) | 3 (3.3) |

| Close friend | 2 (4.4) | 9 (10) |

| Antagonist/nemesis* | 13 (28.9) | 7 (7.8) |

| No on-screen death | 15 (33.3) | 45 (50) |

*Starred categories indicate significant difference between animated and comparison films (Z test of column proportions; P<0.05).

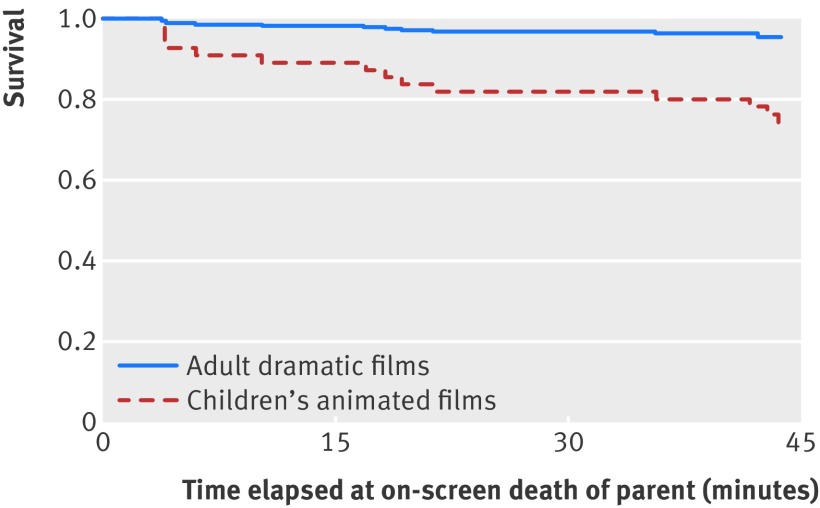

Figure 3 shows survival curves representing on-screen deaths of parents. There was some evidence to suggest that risk of parental death was higher in children’s animated films than in comparison films (hazard ratio 5.76, 95% confidence interval 0.98 to 33.9; P=0.053). The interaction between film type and years since release was not a significant predictor of parental mortality (P=0.46).

Fig 3 Survival curves for parents of protagonists in animated versus comparison films

Discussion

In our study of 135 top grossing North American films the risk of death of important characters was higher in children’s animated films than dramatic films from the same year. Notably, the risk of murder was higher in children’s animated films than in dramatic films for adults. There was no evidence to suggest these results had changed over time since 1937, when Snow White’s stepmother, the evil queen, was struck by lightning, forced off a cliff, and crushed by a boulder while being chased by seven vengeful dwarves.

The bad

Children between the ages of 2 and 5 consume an estimated 32 hours a week of visual media, including movies.16 As many parents will attest, children tend to watch the same film multiple times17 and are thus likely to be repeatedly exposed to on-screen deaths. Exposure to on-screen death and murder could have deleterious and long lasting effects on children, especially young children.5 6 18 Recent evidence suggests that media exposure to real life traumas (such as terrorist attacks) can trigger symptoms of post-traumatic stress among children.19 Although older children are more likely to be frightened by witnessing media coverage of real events,20 children under 7 are just as likely to be frightened by unrealistic and even impossible events on screen5 20 and could therefore experience similarly deleterious consequences after watching such events in animated movies. In one experimental study, children exposed to fictional on-screen depictions of death reported increased worry about the occurrence of similar events and increased avoidance of situations relevant to those events.21 For example, children who watched a movie about drowning were less willing to try canoeing than other children.22 Effects of exposure to animated depictions of death have not been studied. Research indicates, however, that viewing violent cartoons can influence children’s behavior,23 suggesting that exposure to on-screen death in animated films could have similar consequences. Common causes of death in our sample of animated films included animal attack and defenestration, which could lead children to develop potentially debilitating fears of animals, heights, or both. Murder occurred at nearly three times the rate in animated children’s films as in dramatic films for adults. These deaths might be particularly traumatic to young viewers because of their inherently violent intent.

Our results suggest that parents of main characters are a primary target of on-screen death in children’s animated films. In the present sample, risk of parental death was five times higher in children’s animated films compared with dramatic films for adults.1 Given the central role children play as characters in animated films aimed at children in comparison with adult oriented movies, it follows that parents, or reference to them, might be more likely to appear in such films in the first place, biasing our comparison. Nonetheless, death of a parent can be a particularly difficult theme for children to face. Separation from a parent is a common source of worry among children, and separation anxiety disorder is the most commonly diagnosed childhood anxiety disorder.24 Repeatedly facing this fear on screen could be particularly traumatic for children, especially if they are unprepared.

In the present sample, antagonists or nemeses were also more likely to be victims of the first on-screen death in animated films than in comparison films. This has complicated moral implications. Some authors have noted that the deaths of antagonists in children’s films are often depicted as justified, perhaps sending the dubious moral message that “bad guys” deserve to die.6

The good

We have so far discussed the possible adverse consequences that exposure to death in animated films could have on young children. It is also possible that such exposure could have a positive impact on children’s adjustment and understanding of death, if treated appropriately.2 Films that model appropriate grief responses could help children to gain a deeper understanding of the meaning of death. Nonetheless, death and/or the grieving process often go unacknowledged in children’s animated films.2 25 A notable exception is The Lion King, which portrays the protagonist experiencing a complex grieving process and eventually arriving at a healthy acceptance of his father’s death, even forgiving his father’s murderer.2 Films depicting death in this more nuanced way could provide a valuable resource for initiating discussions about death between children and adults.6 Indeed, cinematherapy is sometimes used to facilitate counseling with grieving adolescents,26 a therapeutic practice that might be extended to younger children.

The ugly

Of note, our analysis included only on-screen deaths. Although on-screen death might be particularly traumatic to young viewers,6 deaths that occur off screen, or even before the beginning of a film, could also expose children to themes of death. As has been recently noted in the media, parental absence, because of death or other factors, is a common theme in children’s animated films.27 28 Of course, such absence often serves a dramatic purpose, providing child protagonists with adversity to overcome and allowing the adventure story to unfold unhindered. Indeed, parental death has long been a common theme in children’s literature.29 For example, the collected works of the brothers Grimm (on which many children’s animated movies are based) are rife with gruesome deaths, parental and otherwise.30 It is unclear how the inclusion of off-screen death could have influenced our study; given the high incidence of “orphanhood” in animated films, however, we might have underestimated the prevalence of death in animated films and its implications on viewers.

We considered only the first on-screen death in animated and comparison films. While results therefore indicate that characters in animated films die off more quickly, the total number of deaths could be higher in dramatic films targeted at adults.

In addition, we considered only the presence or absence of on-screen death and did not rate the realism or violence of those deaths. More gruesome on-screen deaths might be more traumatic for children. Nevertheless, our sample of animated films included three gunshot deaths (Bambi, Peter Pan, Pocahontas), two stabbings (Sleeping Beauty, The Little Mermaid), and five animal attacks (A Bug’s Life, The Croods, How to Train Your Dragon, Finding Nemo, Tarzan), suggesting grisly deaths are common in films for children.

Another potential limitation was our inability to blind outcome assessors to the conditions and hypotheses of the study. We used a standardized coding sheet, however, and any ambiguous events (n=6) were noted and resolved by consensus. In a sensitivity analysis we coded these ambiguous events in the most conservative way (that is, as “no death” for children’s animated films and “death” for comparison films) and found no differences in the pattern or significance of the results (data available from the authors on request).

Conclusions

This is the first study to use survival analysis techniques to examine death in animated films. We conclude that children’s animated films, rather than being innocuous alternatives to the gore and carnage typical of American films, are in fact hotbeds of murder and mayhem. Parents might consider watching such movies alongside their children, in the event that the children need emotional support after witnessing the inevitable horrors that will unfold. That’s all, folks!

What is already known on this topic

Young children lack a full understanding of the concept of death

Death is a common theme in North American films

Children watch many films

What this study adds

Important characters in children’s animated films die more quickly than important characters in dramatic films aimed at adults

Children who watch animated films are often exposed to scenes of murder

Children who watch animated films are not spared gruesome causes of death such as gunshots, stabbings, and animal attacks

The first author thanks Catherine M Pound, who inadvertently inspired this study by saying “You’re watching Finding Nemo with your children this evening? Take my advice: skip over the first 5 minutes.” The authors also thank the peer reviewer who helpfully acknowledged that the first five minutes of Finding Nemo were comparable with the shower scene in Psycho; and the many film studios that produced the source material for this study. Despite all the carnage, data collection was most enjoyable.

Contributors: The study was conceived by IC and JBK. All authors participated in the design of the study, participated in data collection, commented on the implications of the results, and critically reviewed the final manuscript. IC, MK, MW, and JBK designed the analytical plan. MK performed the data analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. IC is guarantor.

Funding: This research was supported, in part, by funding from the Canada Research Chairs program for IC. JBK is supported by a Sir Henry Dale Fellowship jointly funded by the Wellcome Trust and the Royal Society (Grant No 101272/Z/13/Z).

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: Not required. No fictitious characters, whether dying during follow-up or surviving, could provide informed consent to participate in this research. Any resemblance of fictitious characters to the authorship team is purely coincidental.

Data sharing: The statistical code and dataset are available from the corresponding author.

Transparency declaration: The lead author (the manuscript’s guarantor) affirms that this manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Cite this as: BMJ 2014;349:g7184

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Appendix: List of animated films and matched comparisons

References

- 1.McDonald P. ‘We just make the pictures…?’ How work is portrayed in children’s feature length films. In: Rhodes C, Lilley S, eds. Organizations and popular culture: information, representation and transformation. Routledge, 2013.

- 2.Sedney MA. Maintaining connections in children’s grief narratives in popular film. Am J Orthopsychiatry 2002;72:279-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vianello R, Marin ML. Children’s understanding of death. Early Child Develop Care 1989;46:97-104. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brent SB, Speece MW, Lin C, Dong Q, Yang C. The development of the concept of death among Chinese and US children age 3-17 years of age: from binary to “fuzzy” concepts? Omega J Death Dying 1996;33:67-83. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cantor J. The media and children’s fears, anxieties, and perceptions of danger. In: Singer DH, Singer JL, eds. Handbook of children and the media. Sage, 2001.

- 6.Cox M, Garrett E, Graham JA. Death in Disney films: implications for children’s understanding of death. Omega J Death Dying 2005;50:267-80. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stearns DC. Grief, death, funerals. Encyclopedia of children and childhood in history and society, 2004. www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1G2-3402800196.html.

- 8.Willis CA. The grieving process in children: strategies for understanding, educating, and reconciling children’s perceptions of death. Early Child Educ J 2002;29:221-6. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shultz NW, Huet LM. Sensational! Violent! Popular! Death in American movies. Omega J Death Dying 2001;42:137-49. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Motion Picture Association of America. Film Ratings. www.mpaa.org/film-ratings/.

- 11.Box Office Mojo. Domestic grosses adjusted for ticket price inflation. www.boxofficemojo.com.

- 12.Internet Movie Database. www.imdb.com.

- 13.Classification and rating administration. www.filmratings.com.

- 14.Grambsch PM, Therneau TM. Proportional hazards test and diagnostics based on weighted residuals. Biometrika 1994;81:515-26. [Google Scholar]

- 15.SPSS Statistics for Windows [program]. 21 version. IBM, 2012.

- 16.McDonough P. TV viewing among kids at an eight-year high. Nielsen Newswire 2009.

- 17.Dobrow JR. The rerun ritual: using VCRs to re-view. In: Dobrow JR, ed. Social and Cultural Aspects of VCR use: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1990:181-93.

- 18.Cantor J. Media violence. J Adolescent Health 2000;27:30-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoekstra SJ, Harris RJ, Helmick AL. Autobiographical memories about the experience of seeing frightening movies in childhood. Media Psychology 1999;1:117-40. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Busso DS, McLaughlin KA, Sheridan MA. Media exposure and sympathetic nervous system reactivity predict PTSD symptoms after the Boston marathon bombings. Depress Anxiety 2014;31:551-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cantor J, Nathanson AI. Children’s fright reactions to television news. J Commun 1996;46:139-52. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cantor J, Omdahl BL. Children’s acceptance of safety guidelines after exposure to televised dramas depicting accidents. West J Comm 1999;63:57-71. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hapkiewicz WG. Childrens reactions to cartoon violence. J Clin Child Psychol 1979;8:30-4. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ehrenreich JT, Santucci LC, Weiner CL. Separation anxiety disorder in youth: phenomenology, assessment, and treatment. Psicol Conductual 2008;16:389-412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haas L. “Eighty-six the mother”: murder, matricide, and good mothers. In: Bell E, Haas L, Sells L, eds. From mouse to mermaid: the politics of film, gender, and culture. Indiana University Press, 1995:193-211.

- 26.Slyter M. Creative counseling interventions for grieving adolescents. J Creativity Mental Health 2012;7:17-34. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Poulton S. Why does Disney hate parents? Ever noticed your favourite films always kill off mum and dad. Daily Mail Online 2010. www.dailymail.co.uk/femail/article-1308584/Why-does-Disney-hate-parents-Ever-noticed-favourite-films-kill-Mum-Dad-.html.

- 28.Boxer S. Why are all the cartoon mothers dead? The Atlantic 2014. www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2014/07/why-are-all-the-cartoon-mothers-dead/372270/.

- 29.Moss JP. Death in children’s literature. Elementary English 1972;49:530-2. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tatar M. The hard facts of the Grimms’ fairy tales. Princeton University Press, 1987.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix: List of animated films and matched comparisons