Abstract

Background: Many people with dementia die in long-term care settings. These patients may benefit from a palliative care goal, focused on comfort. Admission may be a good time to revisit or develop care plans.

Objective: To describe care goals in nursing home patients with dementia and factors associated with establishing a comfort care goal.

Design: We used generalized estimating equation regression analyses for baseline analyses and multinomial logistic regression analyses for longitudinal analyses.

Setting: Prospective data collection in 28 Dutch facilities, mostly nursing homes (2007–2010; Dutch End of Life in Dementia study, DEOLD).

Results: Eight weeks after admission (baseline), 56.7% of 326 patients had a comfort care goal. At death, 89.5% had a comfort care goal. Adjusted for illness severity, patients with a baseline comfort care goal were more likely to have a religious affiliation, to be less competent to make decisions, and to have a short survival prediction. Their families were less likely to prefer life-prolongation and more likely to be satisfied with family–physician communication. Compared with patients with a comfort care goal established later during their stay, patients with a baseline comfort care goal also more frequently had a more highly educated family member.

Conclusions: Initially, over half of the patients had a care goal focused on comfort, increasing to the large majority of the patients at death. Optimizing patient–family–physician communication upon admission may support the early establishing of a comfort care goal. Patient condition and family views play a role, and physicians should be aware that religious affiliation and education may also affect the (timing of) setting a comfort care goal.

Introduction

Dementia is a life-limiting disease and palliative care (or comfort care or hospice care),1 with its focus on quality of life and comfort may therefore apply.2–4 In practice, however, many patients with dementia, including patients who spend the last period of life in a long-term care facility, receive burdensome treatments that do not necessarily improve comfort.3,5

Determining what is most important when making treatment decisions through advance care planning (ACP) discussions may help avoid future burdensome treatment.2,6–8 ACP is a process of ongoing communication between patient, family, and professional caregivers that may include determining patient preferences, establishing the main care goals, and then developing plans.9 ACP should begin as early as possible, to give patients the opportunity to participate in the decision-making process and express their values and wishes.2 Admission of patients with dementia to a nursing home may be a good time to revisit or develop care plans.2

Studies including patients with dementia have demonstrated that several factors may relate to applying ACP in general or to having a palliative care goal. A decline in the patient's health may facilitate starting ACP discussions.10–12 However, starting the decision-making process is only facilitated when professionals involved in care planning with family are continuously available.11–16 Several authors have shown that professionals taking the time and building a relationship with the patient and family related positively to initiating ACP and to care directed toward comfort.11,13,14,17,18

We investigated care goals and when they were established in nursing home patients with dementia throughout their stay in the nursing home, and also factors associated with establishing a comfort care goal shortly after admission and later during their stay.

Methods

In the Dutch End of Life in Dementia (DEOLD) study, patients' families and physicians provided data about treatment, care, and outcome from the time of nursing home admission until death or end of data collection. The study was nationwide and representative of The Netherlands with regard to family ratings of quality of care and other characteristics.19 The study protocol was approved by the Medical Ethics Review Committee of the VU University Medical Center.19

Study design and setting

Seventeen nursing home organizations covering 28 facilities prospectively recruited 372 newly admitted patients with dementia between January 2007 and July 2009, with a follow-up between 1 and 3½ years (2007–2010). Physicians and families (the contact persons for professionals) completed baseline assessments 8 weeks after admission, which included the period of 6 weeks after admission during which a plan of care must be established according to the Dutch legal standard.20 This dynamic plan includes the main goals to be achieved with the care and treatment.21

Dutch nursing homes employ physicians specialized as elderly care physicians through a 3-year vocational training, distinct from geriatricians whose profession is hospital based.22 Community-dwelling older people receive care from a general practitioner and after admission to a nursing home the care is taken over by an elderly care physician.

Data collection

Both patients' families (contact persons for professionals) and elderly care physicians reported on patients and families, completing written questionnaires at baseline, every 6 months afterwards (semi-annually), and after death (within 2 weeks for physicians and after 2 months for families). In addition, physicians continuously registered intercurrent health problems on patient monitoring forms.

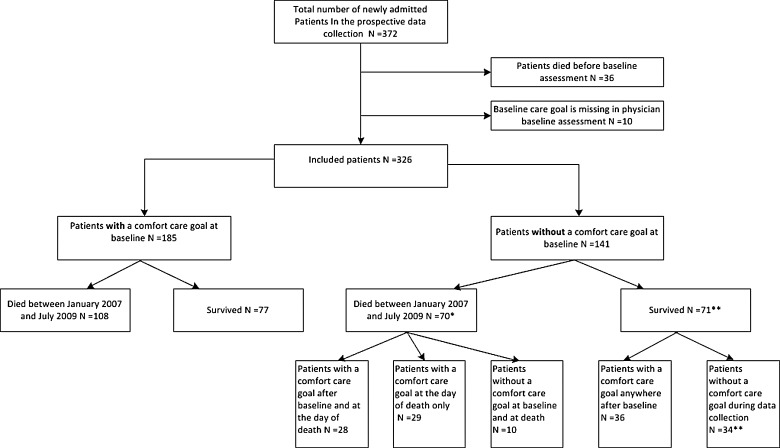

Thirty-six patients died before the baseline assessment and were excluded, as no baseline assessment was available. Data on care goals were incomplete for 10 patients and we included 326 patients (88%; Fig. 1). During the data collection period 54% (178/326) of the selected patients died.

FIG. 1.

Timing of assessing a comfort care goal of patients who died and did not die during data collection. *For three patients, the care goal at death was missing. **For one patient, the care goal after the baseline assessment was missing.

Measures

Main care goal as the outcome

Physicians reported the main care goal, the single goal that took priority, in all the assessments (questionnaires). The six response options were: (1) palliative care goal, aimed at well-being and quality of life, irrespective of shortening or prolonging of life; (2) symptomatic care goal, aimed at well-being and quality of life, additional prolonging of life undesirable; (3) maintaining or improving function; (4) life prolongation; (5) other; and (6) global care goal has not been established yet. Reasons for absence of a care goal were inventoried.

Timing of ACP discussions

Family was asked whether ACP had been discussed with professionals (e.g., about “no hospitalization,” use of antibiotics or intravenous fluids, etc.). If so, the family was also asked which professionals had been involved, how much time was spent on the discussions, and how they felt about the timing in relation to the patient's health. Response options for timing were “Too early,” “At just the right time,” “Too late,” “I feel that discussions about future care are not necessary or undesirable,” and “Don't know.” In addition, physicians were asked whether directives and care goals assessed within 8 weeks after admission had been discussed with the family. Response options were “Yes,” “No, because there have been no family discussions at all,” and “No, because (other reasons).”

Characteristics potentially associated with establishing a comfort care goal

We examined demographics and clinical characteristics potentially associated with establishing a comfort care goal. These characteristics were candidate factors in the analyses. We identified these factors from our review as (1) associated with the initiation of ACP in dementia,11 (2) described in the literature as related to specific care provided in nursing home patients with dementia, and (3) be related to the timing of initiating ACP in dementia or to palliative or life-prolonging treatments.18,23–29 For example, the review indicated that prior familiarity of the physician with the patient and family trust in professional caregivers relates to initiating ACP.11 This suggests that these factors also promote the establishment of a comfort care goal. Table 1 lists and justifies characteristics potentially associated with establishing such a goal and Appendix A provides additional information about the variables used.

Table 1.

Overview and Justification of Selection of the Factors Potentially Associated with Establishing a Comfort Care Goal: Candidate Factors

| Characteristics | Reference for justification of selection of variables | Respondent |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline characteristics, and used in baseline and longitudinal regression analyses | ||

| Patient with dementia | ||

| Higher age | 11 | Physician |

| Gender, female | 11 | Physician |

| Higher illness severity | 11 | Physician |

| Higher dementia severity | 11 | Physician |

| More severe dementia | 11 | Physician |

| Lack of a religious affiliation | 23 | Family |

| Lack of importance of faith or spirituality | 23 | Family |

| Previous expressed wishes about medical treatments | 11 | Family |

| Availability of a living will according to family | 11,24,25 | Family |

| Availability of living will according to physician | 11,24,25 | Physician |

| Competent to make decisions | 11 | Family |

| Place of residence before admission, hospital | 26,27 | Physician |

| Family | ||

| Close relation to patient | 28 | Family |

| Lack of a religious affiliation | 23 | Family |

| Lack of importance of faith or spirituality | 23 | Family |

| Higher educational level | 11 | Family |

| Shorter family prediction of patient survival (1 year or less) | 29 | Family |

| Preference goal of treatment: • Not preserve his/her life as long as possible • As comfortable as possible • Symptoms should be treated even if that results in the shortening of life |

19 | Family |

| (Very) much trust in physician | 11 | Family |

| Higher satisfaction with family–physician communication | 11 | Family |

| Professionals | ||

| Shorter physician prediction of patient survival (1 year or less) | 18, 29 | Physician |

| Knew patient before admission to nursing home | 11 | Physician |

| Professional asked about wishes | 11 | Family |

| (Very) much family trust in physician | 11 | Physician |

| Higher satisfaction with family–physician communication | 11 | Physician |

| Characteristics assessed at a later point in time and only used in longitudinal regression analysis | ||

| Patient with dementia | ||

| Higher illness severity in last assessmenta | 11 | Physician |

| Higher dementia severity in last assessment | 11 | Physician |

| More severe dementia in last assessment | 11 | Physician |

| Longer length of stay | Physician | |

| Expected death in last assessment | 18, 29 | Physician |

| Intercurrent disease in the first week after admission | 11 | Physician |

| More periods with intercurrent disease | 11 | Physician |

| Family | ||

| Shorter family prediction of patient survival (1 year or less) in last assessment | 18, 29 | Family |

| Preference goal of treatment in last assessment: • Not preserve his/her life as long as possible |

18 | Family |

| (Very) much trust in physician in last assessment | 11 | Family |

| Higher satisfaction with family–physician communication in last assessment | 11 | Family |

| Professionals | ||

| Shorter physician prediction of patient survival (1 year or less) in last assessment | 18, 29 | Physician |

| (Very) much family trust in physician in last assessment | 11 | Physician |

| Higher satisfaction with family–physician communication in last assessment | 11 | Physician |

Last assessment before death refers to the baseline or a semi-annual assessment.

Analyses

We examined the main care goal at baseline and semi-annually afterwards. Families' opinions on timing were analyzed at baseline and at the first assessment after an ACP discussion in the nursing home (baseline or later during the stay). For regression analyses, we dichotomized palliative and symptomatic care goals as a comfort care goal versus all other response options. We determined which candidate factors were associated with establishing a comfort care goal cross sectionally with baseline assessments, and also longitudinally including the semi-annual and after-death assessments. All analyses were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics 20 (2011; IBM, Armonk, NY).

Baseline assessment analyses

Analyses included χ2 and t tests to compare patients with and without a baseline comfort care goal and to compare families' perceptions of the timing of ACP discussions. We performed generalized estimating equations (GEE) regression in three steps (Table 2) to analyze associations with establishing a comfort care goal adjusted for patients' clustering with the 80 physicians. The independent variables were the characteristics potentially associated with establishing a baseline comfort care goal (Table 1; baseline characteristics). β and confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated. A higher β reflects a stronger association.

Table 2.

Steps Taken in Regression Analyses

| Baseline assessment GEE regression analyses | Longitudinal multinomial logistic regression analyses | |

|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | All candidate factors were analyzed separately (not shown). | All candidate factors (baseline and last assessment characteristics) were analyzed separately. |

| Step 2 | All the variables significant (p<0.05) in step 1 were adjusted for illness severity at baseline.a | All the variables significant in the first step were adjusted for length of stay. |

| Step 3 | All the variables which were significant in the second step were examined in manual stepwise backward regression (deleting the variable that had the highest p value of≥0.05 and repeating this process until all variables had p<0.05) to assess the strongest independent factors, forcing illness severity into the model.b | Analyses were performed with adjustment for length of stay and illness severity.a |

| Step 4 | — | Stepwise backward regression was performed with all the significant factors of step 3, forcing length of stay and illness severity into the model.b |

Missing data on the illness severity variable (0.6% in baseline assessment analyses and 1.1% in longitudinal analyses) were imputed with overall means.

Missing data on the variables entered into the stepwise backward regression model were imputed with means for continuous variables and modes for nominal variables. For baseline assessment analyses missing data on the satisfaction with family–physician communication according to the physician baseline variable were 12.6% and the patient's prognosis one year or less according to the physician baseline variable 12.3%. Missing data on the patient's prognosis 1 year or less according to the physician baseline variable were 11.2% for longitudinal analyses. Missing data on other variables in baseline and longitudinal analyses were <10%.

GEE, generalized estimating equations.

Longitudinal analyses

To determine whether other characteristics were associated with establishing a comfort care goal later during the stay, multinomial logistic regression analyses were performed in four steps (Table 2). The dependent variable was a trinomial variable representing establishing a comfort care goal “At baseline” versus “Later during their stay” versus “Only at death or not at all.” Independent variables were variables assessed at baseline, and, in longitudinal analyses, additional variables referring to change over time (Table 1).

Results

Shortly after admission (baseline) the patients had a mean age of 83.7 years and were mildly ill (mean 2.9); 22.2% had severe dementia, and 69.5% were considered incompetent to make decisions (Table 3).

Table 3.

Baseline Demographics and Characteristics of the Sample of Nursing Home Patients with Dementia by a Baseline Comfort Care Goal (n=326)

| Characteristic | Total of patients (n=326) | Patients with comfort care goal at baseline (n=185) | Patients without comfort care goal at baseline (n=141) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient with dementia | ||||

| Age, mean (SD) | 83.7 (6.9) | 83.9 (6.9) | 82.9 (6.8) | 0.237 |

| Gender, Female (%) | 70.9 | 74.6 | 66 | 0.089 |

| Illness severity, mean (SD)a | 2.9 (2.0) | 3.2 (2.1) | 2.4 (1.8) | <0.001 |

| Dementia severity (BANS-S), mean (SD)b | 13.0 (4.1) | 13.3 (4.2) | 12.5 (4.0) | 0.075 |

| Severe dementia (%)b | 22.2 | 23.9 | 19.9 | 0.383 |

| With a religious affiliation (%)c | 77.3 | 82.1 | 71.3 | 0.025 |

| Importance of faith or spirituality (%) | ||||

| • Very important | 32.1 | 31.7 | 32.3 | 0.037 |

| • Somewhat important | 30.9 | 20.6 | 37.4 | |

| • Not important | 37.0 | 47.6 | 30.3 | |

| Previous expressed wishes about medical treatments (%) | 38.4 | 43.9 | 31.4 | 0.024 |

| Living will according to family %) | 13.6 | 14.5 | 12.4 | 0.588 |

| Living will according to physician (%) | 7.1 | 7.6 | 6.4 | 0.692 |

| Competent to make decisions (%) | ||||

| • Yes | 2.6 | 1.1 | 4.4 | 0.139 |

| • Sometimes or in part | 28.0 | 24.9 | 29.9 | |

| • No | 69.5 | 72.4 | 65.7 | |

| Residence before admission (%) | ||||

| • Private home | 33.1 | 31.9 | 34.8 | 0.587 |

| • Other | 66.9 | 68.1 | 65.2 | |

| Family | ||||

| Relation to patient (%) | ||||

| • Spouse | 20.3 | 19.5 | 21.2 | 0.933 |

| • Child | 57.9 | 58.6 | 56.9 | |

| • Other | 21.9 | 21.8 | 21.9 | |

| With a religious affiliation (%)c | 67.0 | 65.9 | 68.4 | 0.645 |

| Importance of faith or spirituality (%) | ||||

| • Very important | 20.9 | 20.0 | 21.4 | 0.953 |

| • Somewhat important | 40.5 | 40.0 | 40.8 | |

| • Not important | 38.7 | 40.0 | 37.8 | |

| Educational level (%) | 0.298 | |||

| • None or primary/elementary school | 6.2 | 5.2 | 7.4 | |

| • (High school preparing for) technical or trade school | 48.5 | 44.8 | 53.3 | |

| • High school preparing for bachelor's or master's degree: | 9.8 | 11 | 8.1 | |

| • Bachelor's or master's degree | 35.5 | 39 | 31.1 | |

| Family prediction of patient survival of 1 year or less (%) | 8.1 | 10.5 | 5.2 | 0.093 |

| Preference goal of treatment (totally/somewhat agree) (%): | 10.2 | 7.1 | 14.1 | 0.044 |

| • Preserve his/her life as long as possible | 91.5 | 93.0 | 89.6 | 0.296 |

| • As comfortable as possible | 91.2 | 93.6 | 88.1 | 0.097 |

| • Symptoms should be treated even when it shortens life | ||||

| (Very) much trust in physician (%) | 84.1 | 89.3 | 77.4 | 0.005 |

| Satisfied with family–physician communication (%) | 57.8 | 67.3 | 45.9 | <0.001 |

| Professionals | ||||

| Physician prediction of patient survival of 1 year or less (%) | 17.5 | 22.7 | 10.6 | 0.004 |

| Knew patient before admission to nursing home (%) | 11.3 | 12.1 | 10.8 | 0.725 |

| Professional asked about wishes (%) | 41.8 | 48.3 | 33.6 | 0.009 |

| (Very) much family trust in physician (%) | 71.0 | 78.9 | 58.6 | <0.001 |

| Satisfied with family–physician communication (%) | 81.8 | 88.6 | 70.9 | <0.001 |

“How sick is the patient now?; 1=“not ill”, 2–3=“mildly”, 4–5=“moderately”, 6–7=“severely”, and 8–9=“moribund.”23,24

Scores range from 7 (“no impairment”) to 28 (“complete impairment”). A score of 17 or higher refers to “severe dementia.”25–27

Protestant, Catholic, Humanist, and other versus without a religious affiliation.

SD, standard deviation; BANS-S, Bedford Alzheimer Nursing Severity-Scale.

Approximately three-quarters had a religious affiliation and for 89% of these patients (not in table), faith or spirituality was very or somewhat important; most were Protestant. Families' educational levels varied between no education or primary/elementary school (6.2%) and at least a bachelor's degree level (36%).

Care goals

At baseline, 56.7% of all patients had comfort as the main care goal (Table 4; Fig. 1). Of the patients who died, 60.7% had a comfort care goal at baseline and 89.5% had a comfort care goal on the day of death (Table 4).

Table 4.

Main Care Goal at Baseline and Over Time of Patients Who Died During Data Collection (%)

| All patients n=326 | Deceased patients n=178 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Baseline | Last assessment before deatha | Day of death | |||||

| Care goal | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| Comfort care goal, total | 185 | 56.7 | 108 | 60.7 | 132 | 74.2 | 154 | 89.5 |

| • Palliative care goal | 136 | 41.7 | 79 | 44.4 | 87 | 48.9 | 77 | 44.8 |

| • Symptomatic care goal | 49 | 15.0 | 29 | 16.3 | 45 | 25.3 | 77 | 44.8 |

| Maintaining or improving function | 67 | 20.6 | 30 | 16.9 | 25 | 14.0 | 7 | 4.1 |

| Life prolongation | 3 | 0.9 | 2 | 1.1 | 4 | 2.2 | 3 | 1.7 |

| Other | 9 | 2.8 | 6 | 3.4 | 5 | 2.8 | 1 | 0.6 |

| Global care goals had not been assessed yet | 62 | 19.0 | 32 | 18.0 | 12 | 6.7 | 7 | 4.1 |

Last=last assessment before death (which could be the baseline or a semi-annual assessment).

For almost one-fifth (19.0%) of the patients, no care goal had been determined shortly after admission. For three-quarter of these patients, directives and care goals were not discussed with the family according to the physician. Reasons for this included that a family meeting had not taken place yet although it was planned, emotions related to admission, family lack of time, the physician being off duty or sick, and a favorable patient condition. The patients without a baseline care goal were less severely ill than patients with a care goal (mean 3.1, standard deviation [SD] 2.1 versus 1.9, SD 1.4; p<0.001; not in table). At death, 4.1% had no care goal.

Timing of ACP discussions

Sixty-five percent of the families (212/326) indicated that a professional discussed ACP with them (at some point) during the patient's stay. Most families reported that the first ACP discussion had been within 8 weeks after admission (86.3%; 183/212). Most of these discussions were with a physician (90.9%; 161/177) and in 34.2% of the cases a nurse also attended the discussions (55/161).

Of the families who had had ACP discussions, 69.8% (148/212) thought the first time it was discussed was just right in relation to the patient's health. However, 8% thought the timing was too early and 4.7% thought it was too late. ACP discussions within 8 weeks after admission were judged by 9.1% of families to be too early and by 3.4% to be too late. One family member (0.5%) thought an ACP discussion was not necessary or undesirable.

Of the families who thought the timing—within 8 weeks after admission—was not right (9.1% too early and 3.4% too late), 68.2% were not satisfied with family–physician communication, compared to only 12.9% of families who found the timing just right (p<0.001). There were no differences in gender, having a religious affiliation, educational level, and the time family spent with the patient between families who thought the timing within 8 weeks after admission was just right and those who thought timing was not right (p=0.715 or higher).

Associations with a baseline comfort care goal

Table 3 shows differences at baseline between patients with and without a baseline comfort care goal. Patients who had a comfort care goal were more severely ill (Table 3, and in multivariable GEE analyses, 0.19 points higher on the illness severity scale). Table 5 presents the factors associated with having a baseline comfort care goal after adjustment for illness severity. The strongest associations were families' not preferring to preserve the patient's life as long as possible, physicians' satisfaction with the family-physician communication, and a high level of family trust in the physician according to the physician.

Table 5.

Baseline Characteristics Associated with having a Comfort Care Goal Shortly after Admission (n=326)

| Adjusted for illness severity onlya | Final modelb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | β (95% CI) | p | β (95% CI) | p |

| Patient with dementia | ||||

| Illness severity (0–10) | — | 0.15 (0.02; 0.28) | 0.021 | |

| Dementia severity (BANS-S; 7–28) | 0.05 (−0.01; 0.10) | 0.097 | — | |

| Any specific religious background | 0.71 (0.20; 1.21) | 0.006 | 0.67 (0.15; 1.19) | 0.012 |

| Competent to make decisions (continuous variable) | −0.56 (−1.77; −0.95) | 0.004 | −0.48 (−0.88; −0.08) | 0.019 |

| Previous expressed wishes about medical treatments | 0.52 (0.00; 1.03) | 0.050 | — | |

| Family | ||||

| Preference care goal: Preserve his/her life as long as possible | −1.16 (−1.95; −0.38) | 0.004 | −1.24 (−2.04; −0.45) | 0.002 |

| Satisfied with family–physician communication | 0.86 (0.34; 1.38) | 0.001 | 0.84 (0.31; 1.38) | 0.002 |

| (Very) much trust in physician | 0.77 (0.17; 1.36) | 0.012 | — | |

| Professionals | ||||

| Physician prediction of patient survival of 1 year or less | 0.78 (0.15; 1.41) | 0.016 | 0.74 (0.10; 1.39) | 0.024 |

| Satisfied with family–physician communication | 1.14 (0.49; 1.80) | 0.001 | — | |

| (Very) much family trust in physician | 1.01 (0.45; 1.56) | <0.001 | — | |

| Professional asked about wishes | 0.57 (0.04; 1.11) | 0.036 | — | |

Using multivariable Generalized Estimated Equations (GEE) adjusted for clustering of patients with the 80 physicians who completed the baseline assessments.

Using stepwise backward Generalized Estimated Equations (GEE) adjusted for clustering of patients with the 80 physicians who completed the baseline assessments.

CI, confidence interval; BANS-S, Bedford Alzheimer Nursing Severity-Scale.

Table 5 (right column) also lists the factors that were independently associated with a baseline comfort care goal. Patients with a comfort care goal were more likely to be more severely ill at admission, to have a religious affiliation, and were less likely to be competent to make decisions. Furthermore, at baseline, their families were more likely not to prefer life prolongation and to be satisfied with physician communication. In addition, patients more frequently had a physician's survival prediction of 1 year or less.

Longitudinal associations with establishing a comfort care goal

Exploring the association of candidate factors with a comfort care goal shortly after admission, at a later moment during the patient's stay or only at death/not at all, we found a higher educational level of family to be additionally associated with a comfort care goal (data not shown). This association remained significant after adjustment for length of stay and illness severity.

Discussion

This study found that shortly after admission just over half (56.7%) of the nursing home patients with dementia had a main care goal focused on comfort and almost one-fifth (19%) had no care goal. At death, the large majority had a care goal focused on comfort (89.5%) and 4.1% died without a care goal. Establishing a comfort care goal shortly or later after admission was associated with the patient's condition, religion, and competency to make decisions on medical treatments, family views on care goals and family educational level, physicians' prediction of patient survival and family–physician communication as perceived by the family.

A Flemish death certificate survey including long-term care home patients also found that the large majority of patients had a comfort care goal in the last week of life.30 It is worth noting that some patients did not have any care goal at baseline, or even on the day of death, whereas establishing a goal is important for guaranteeing continuity of care, and to guide current and future care. 2,6–8

Communication is a key element in ACP discussions.31 In this study we found that family satisfaction about family–physician communication was independently associated with establishing a baseline comfort care goal. Other studies found that physician's absence, or lack of time is a barrier to ACP decision-making11 In addition, physician skills and confidence could affect family-physician communications.

It was striking that patients with a comfort care goal shortly after admission were more religious (formally and informally and mostly Protestant). One U.S. study found that orthodox Protestants valued freedom from shortness of breath more highly than older adults with other religious affiliations.32 Yet other U.S. research found that patients who obtained spiritual support from religious communities (mostly Catholic and Baptist) were less likely to receive hospice care.33 Perhaps in the secularized country of The Netherlands, where traditional religious membership and beliefs have declined significantly,34 people with a religious affiliation (often not orthodox), more readily accept the situation and put their life in God's hands, which in turn facilitates care focused on comfort. As expected, families were less likely to prefer life-prolongation at baseline when the patient had a comfort care goal. This means that the family views affected the establishing of a patients' care goal focused on comfort. Particularly in the case of dementia, the family is an important partner in establishing a care goal. Mitchell et al.35 reported that patients with family who understood the prognosis and clinical course of the disease were less likely to receive aggressive end-of-life care. This was not found in previous analyses in our study population36 possibly because Dutch physicians provide more guidance and Dutch families have less influence on the decision-making process than U.S. families.37 Nevertheless, our findings indicate that family preferences do influence decision making, also in The Netherlands. Additionally, the longitudinal analyses showed that patients who had a comfort care goal shortly after admission more frequently had a family member with a higher level of education than patients whose comfort care goal was established at a later moment during their stay. Educational level may play a role in the knowledge about, and understanding of dementia and care options, and in the communication with the physician.

Strengths and limitations and future research

The prospective design is a strength of the DEOLD study. To our knowledge, this is the only fully prospective, nationwide end-of-life study that followed nursing home patients with varying stages of dementia from admission to the nursing home throughout their stay. This enabled us to follow the change of care goals over time. To evaluate whether higher numbers of patients with a comfort care goal shortly after admission are feasible or even preferable, experimental research is needed on the benefits of establishing a comfort care goal shortly after admission and the effects of a comfort care goal, for example on quality of care and dying.

In the study, questionnaires were completed by physicians and families, which provided different perspectives on care goals. Earlier studies have identified factors that may relate to ACP or to establishing a comfort care goal.11 However, most of these studies only examined one factor, or different factors from only one perspective. In addition, we performed multivariable analyses to examine whether factors were independently associated with a baseline comfort care goal. We found several factors associated with establishing a comfort care goal shortly after admission; however, the causality of the associations should be interpreted with caution. For example, a comfort care goal may have been the result of a good communication process between family and the physician. Alternatively, families may have been satisfied with the communication because it resulted in a comfort care goal. For the longitudinal regression analyses we adopted a different analytic approach, as we could not adjust for clustering of physicians in the regression analyses with three hierarchical outcomes.

We acknowledge that the question how family felt about the timing of ACP discussions in relation to the patient's health included reference to patient's health unnecessarily. The proportion of families who thought the ACP discussions were conducted too late may therefore have been underestimated. In future research families should be allowed to use their own frame of reference, which may or may not include the patient's condition. In addition, we did not ask families who did not discuss ACP with a professional whether they would have wanted such discussions.

Our study was conducted in a country with a high presence of specialized physicians in nursing homes as compared to, for example, the United States.37 Factors associated with a comfort goal may differ if, for example, social workers take the lead in planning. We recommend further research in countries with other models of care.

Implications and conclusion

Shortly after admission, care goals are established for four-fifths of nursing home patients with dementia in The Netherlands. Half of them had a goal focused on comfort, the proportion increasing to the large majority when they died.

Efforts to promote establishing a comfort care goal require adequate and early patient–family–physician communication about survival prediction, patient and family wishes and preferences regarding care goals and treatments at the end of life. In these discussions physicians should be aware that religious affiliation and educational level play a role in the timing of establishing a comfort goal of care. Overall, planning of end-of-life care needs an individual approach with ongoing communication between multiple parties, taking into account individual characteristics and care preferences.

Appendix A.

Overview of the Variables Used

| Domains and variables | Item and source |

|---|---|

| Patient with dementia | |

| Age and gender | |

| Illness severity | With Charlson's “illness severity rating,” rating from 1 (not ill) to 9 (moribund).a,b |

| Dementia severity | With the BANS-S.c,d,e Rating from 7–28; higher score means more severely demented. |

| Severe dementia | BANS-S score of 17 or higher refers to “severe dementia.” |

| Any religious affiliation | What is your family/loved one's religious background? Original response options: “Protestant, Catholic, Muslim, Humanist, Jewish, other or no religious background.” For analyses, options were dichotomized into: “a religious background” versus “ no religious background.” |

| Importance of faith or spirituality | How important was faith or spirituality to your family/loved one? Response options: “very important, somewhat important or not important.” |

| Previous expressed wishes about medical treatments | Did your family/loved one ever talk to you or someone else about which medical treatments he/she would want if he/she became too sick to make medical decisions for him or herself (medical treatments such as CPR, respirators, or feeding tubes)? For analyses, options were dichotomized into: “yes” versus “no and don't know.” |

| Living will according to family | Did your family/loved one state his or her wishes about medical treatments in a living will? Response options: “yes or no.” |

| Living will according to physician | Does the patient have a living will? Response options: “yes or no.” |

| Competent to make decisions | Is your family/loved one capable of making decisions on medical treatments by him or herself? Response options: “yes,” sometimes or in part” or “no.” |

| Residence before admission | For analyses, a pre-structured listing of 11 response options was combined into “private home or other.” |

| Length of stay | Day of death minus day of admission. |

| Expectation of death | For analyses, response options were dichotomized into “death was expected” and “death was expected, yet sooner than anticipated” versus “death was neither expected nor unexpected and death was unexpected.” |

| Intercurrent disease at baseline | At least one intercurrent disease (sentinel events) before the baseline assessment: pneumonia, (other) febrile episode, new eating or drinking problem or other new major medical illness or event (e.g., hip fracture, stroke, gastrointestinal bleed, cancer). |

| Periods with intercurrent disease | Number of periods in which the patient had at least one intercurrent disease (sentinel events). |

| Family | |

| Relation to patient | For analyses, a prestructured list of 7 response options was combined into: “spouse, child, other.” |

| Any religious affiliation | What is your religious background? Original response options: “Protestant, Catholic, Muslim, Humanist, Jewish, other or no religious background.” For analyses, options were dichotomized into: “a religious background” or “no religious background.” |

| Importance of faith or spirituality | How important is faith or spirituality to you? Response options: “very important, somewhat important or not important.” |

| Educational level | For analyses, a prestructured listing of 9 response options was combined into “None or primary/elementary school, (high school preparing for) technical or trade school, high school preparing for bachelor's or master's degree, bachelor's or master's degree.” |

| Family prediction of patient survival of 1 year or less | Although this may be a difficult question for you, please do your best to respond. In your opinion, how close do you feel your family/loved one is to the end of her/his life? Response options: “shorter than 1 month,” “1 through 6 months,” “7 through 12 months,” “more than 1 year” and “don't know.” For the analyses, we dichotomized, combining “shorter than 1 month,” “1 through 6 months” and “7 through 12 months” into 1 year or less, versus more than 1 year,” and “don't know.” |

| Preference goal of treatment: | To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statements? |

| • Preserve his/her life as long as possible | • The most important goal of your family/loved one's health care at this time is to preserve his/her life as long as possible, even if that requires treatments that may cause pain or discomfort. |

| • As comfortable as possible | • The most important goal of your family/loved one's health care at this time is to keep him or her as comfortable as possible, even if that means avoiding potentially life-prolonging medical interventions that may cause pain or discomfort. |

| • Symptoms should be treated even if that results in the shortening of life | • Symptoms such as pain should be treated even if that results in the shortening of life. For analyses, the response options were dichotomized, combining “strongly agree” with “agree to some extent” versus “neither agree nor disagree,” “disagree to some extent,” “strongly disagree,” and “don't know.” |

| (Very) much trust in physician | How much trust do you put in the physicians who are involved in the care of your family/loved one trying hard to make the best of it for your family/loved one?)? Response options: “a very large amount of trust,” “a great deal (large amount) of trust,” “somewhat trust,” “little trust,” “very little trust.” For analyses, we dichotomized, combining “a very large amount of trust” and “a great deal (large amount) of trust” as (very) much trust versus the other categories. |

| Satisfaction with family–physician communication | Are you satisfied with how the communication on directives, goals of treatment, and care with the family is going? Response options: “satisfied in every respect,” “satisfied about the main elements,” “neutral,” “not satisfied,” “did not talk with physician(s) yet, while I would have wanted to” or “did not talk to physician(s) yet and I do not think that is needed yet.” For analyses, we dichotomized the categories, combining “satisfied in every respect” and “satisfied about the main elements” as satisfied versus the other categories. |

| Professionals | |

| Physician prediction of patient survival of 1 year or less | Although this may be a difficult question, we ask you to please do your best to respond. In your opinion, how close do you feel the patient is to the end of her/his life? Response options: “shorter than 1 month,” “1 through 6 months,” “7 through 12 months,” “more than 1 year” and “don't know.” For the analyses, we dichotomized, combining “shorter than 1 month,” “1 through 6 months” and “7 through 12 months” into 1 year or less, versus more than 1 year.” and “don't know.” |

| Knew patient before admission to nursing home | Have you (the treating physician) known this patient already before admission to the nursing home? For analyses, response options were dichotomized into “yes” or “no.” |

| Professional asked about wishes | Did a nursing home physician or nurse/nurse's aid ever ask your family/loved one him or herself about the wishes of your family/loved one for current or future medical treatments? |

| (Very) much family trust in physician | How much trust do you believe the family puts in you (the degree to which there is a relationship of trust)? Response options: “a very large amount of trust,” “a great deal (large amount) of trust,” “somewhat trust,” “little trust,” “very little trust” or “don't know.” For analyses, we dichotomized, combining “a very large amount of trust” and “a great deal (large amount) of trust” as (very) much trust versus the other categories. |

| Satisfaction with family–physician communication | Are you satisfied with how the communication on directives, goals of treatment, and care with the family is going? Response options: “satisfied in every respect,” “satisfied about the main elements,” “neutral,” “not satisfied,” “did not talk with family yet, in spite of an attempt to do so” or “did not talk with family yet, not yet invited for a meeting.” For analyses, we dichotomized the categories, combining “satisfied in every respect” and “satisfied about the main elements” as satisfied versus the other categories. |

Charlson ME, Sax FL, MacKenzie CR, et al: Assessing illness severity: Does clinical judgment work? J Chronic Dis 1986;39:439–452;

Charlson ME, Hollenberg JP, Hou J, et al: Realizing the potential of clinical judgment: A real-time strategy for predicting outcomes and cost for medical inpatients. Am J Med 2000;109:189–195.

Volicer L, Hurley AC, Lathi DC, Kowall NW: Measurement of severity in advanced Alzheimer's disease. J Gerontol 1994;49:M223–226;

Bellelli G, Frisoni GB, Bianchetti A, Trabucchi M: The Bedford Alzheimer Nursing Severity Scale for the severely demented: Validation study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 1997;11:71–77;

Van der Steen JT, Volicer L, Gerritsen DL, et al: Defining severe dementia with the Minimum Data Set. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2006;21:1099–1106.

BANS-S, Bedford Alzheimer Nursing Severity-Scale; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation;

Acknowledgments

This study is supported by a career award to J.T.S. that was provided by The Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO, The Hague; Veni 916.66.073), and by a grant from ZonMw The Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (Palliative Care in the Terminal Phase program, grant number 1151.0001), and by the Department of General Practice & Elderly Care Medicine, and the Department of Public and Occupational Health of the EMGO Institute for Health and Care Research, VU University Medical Center, Amsterdam. We also thank Giselka Gutschow, MA, for the support provided in data collection.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.van der Steen JT: Dying with dementia: What we know after more than a decade of research. J Alzheimers Dis 2010;22:37–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van der Steen JT, Radbruch L, Hertogh CM, et al. : White paper defining optimal palliative care in older people with dementia: A Delphi study and recommendations from the European Association for Palliative Care. Palliat Med 2013;28:197–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van der Steen JT, Deliens L: End of life care for patients with Alzheimer's disease. In: Bährer Kohler S. (ed): Self Management of Chronic Disease: Alzheimer's Disease. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer Medizin Verlag, 2009, pp. 113–123 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sepúlveda C, Marlin A, Yoshida T, Ullrich A: Palliative care: The World Health Organization's global perspective. J Pain Symptom Manage 2002;24:91–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Birch D, Draper J: A critical literature review exploring the challenges of delivering effective palliative care to older people with dementia. J Clin Nurs 2008;17:1144–1163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gillick M, Berkman S, Cullen L: A patient-centered approach to advance medical planning in the nursing home. J Am Geriatr Soc 1999;47:227–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fried TR, O'Leary JR: Using the experiences of bereaved caregivers to inform patient- and caregiver-centered advance care planning. J Gen Intern Med 2008;23:1602–1607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Soest-Poortvliet MC: Barriers and facilitators of (timely) planning of palliative care in patients with dementia: A study in Dutch nursing homes. Part of Symposium 07 Palliative ways and means: Improving end of life care for people with dementia. International psychogeriatrics/IPA September2011. www.ipa2011thehague.com/?pid=505&page=Home (Last accessed August24, 2014)

- 9.Teno JM: Advance care planning for frail, older persons. In: Morrison RS, Meier DE, Capello C. (eds): Geriatric Palliative Care. New York: Oxford University Press, 2003. pp. 307–313 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirschman KB, Kapo JM, Karlawish JH: Identifying the factors that facilitate or hinder advance planning by persons with dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2008;22:293–298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van der Steen JT, van Soest-Poortvliet MC, Hallie-Heierman M, et al. : Factors associated with initiation of advance care planning in dementia: A systematic review. J Alzheimers Dis 2014;40:743–757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hurley AC, Volicer L, Rempusheski VF, Fry ST: Reaching consensus: The process of recommending treatment decisions for Alzheimer's patients. Adv Nurs Sci 1995;18:33–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.The AM, Pasman R, Onwuteaka-Philipsen B, Ribbe M, et al. : Withholding the artificial administration of fluids and food from elderly patients with dementia: ethnographic study. BMJ 2002;325:1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karlawish JHT, Quill T, Meier DE, Snyder L: A consensus-based approach to providing palliative care to patients who lack decision-making capacity. Ann Intern Med 1999;130:835–840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pasman HRW, The BAM, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, et al. : Participants in the decision making on artificial nutrition and hydration to demented nursing home patients: A qualitative study. J Aging Stud 2004;18:321–335 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forbes S, Bern-Klug M, Gessert C: End-of-life decision making for nursing home residents with dementia. J Nurs Scholarsh 2000;32:251–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gessert CE, Forbes S, Bern-Klug M: Planning end-of-life care for patients with dementia: Roles of families and health professionals. Omega (Westport) 2000;42:273–291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Travis SS, Bernard M, Dixon S, et al. : Obstacles to palliation and end-of-life care in a long-term care facility. Gerontologist 2002;42:342–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van der Steen JT, Ribbe MW, Deliens L, et al. : Retrospective and Prospective Data Collection Compared in the Dutch End of Life in Dementia (DEOLD) Study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2013;28:88–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Staatsblad 2009:. [Exceptional Medical Expenses Act, AWBZ]. no 131, 2012. https://zoek.officielebekendmakingen.nl/stb-2009-131.html (Last accessed August24, 2014)

- 21.Nederlandse Vereniging van Verpleeghuisartsen (NVVA), Sting, Verpleegkundigen & Verzorgenden Nederland (V&VN): [Concepts and accuracy demands as regards to decision making at the end of life]. Utrecht, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoek JF, Ribbe MW, Hertogh CMPM, van der Vleuten CPM: The role of the specialist physician in nursing homes: The Netherlands' experience. Int J Geriatr Psych 2003;18:244–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schickedanz AD, Schillinger D, Landefeld CS, et al. : A clinical framework for improving the advance care planning process: start with patients' self-identified barriers. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009;57:31–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Black BS, Fogarty LA, Phillips H, et al. : Surrogate decision makers' understanding of dementia patients' prior wishes for end-of-life care. J Aging Health 2009;21:627–650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Molloy DW, Guyatt GH, Russo R, et al. : Systematic implementation of an advance directive program in nursing homes: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2000;283:1437–1444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hirschman KB, Kapo JM, Karlawish JH: Identifying the factors that facilitate or hinder advance planning by persons with dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2008;22:293–298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Powers BA, Watson NM: Meaning and practice of palliative care for nursing home residents with dementia at end of life. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 2008;23:319–325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sampson EL, Jones L, Thuné-Boyle IC, et al. : Palliative assessment and advance care planning in severe dementia: An exploratory randomized controlled trial of a complex intervention. Palliat Med 2011;25:197–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van der Steen JT, Heymans MW, Steyerberg EW, et al. : The difficulty of predicting mortality in nursing home residents. Eur Geriatr Med 2011;2:79–81 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smets T, Verhofstede R, Cohen J, et al. : Factors associated with the goal of treatment in the last week of life in old compared to very old patients: A population-based death certificate survey. BMC Geriatr 2014;14:61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mullick MA, Martin J, Sallnow L: An introduction to advance care planning in practice. BMJ 2013;21:347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garrido MM, Idler EL, Leventhal H, Carr D: Pathways from religion to advance care planning: Beliefs about control over length of life and end-of-life values. Gerontologist 2013;53:801–816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Balboni TA, Balboni M, Enzinger AC, et al. : Provision of spiritual support to patients with advanced cancer by religious communities and associations with medical care at the end of life. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:1109–1117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Statistics Netherlands: [Religion at the turn of the 21th century]. Statistics Netherlands, Den Haag, 2009 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Kiely DK, et al. : The clinical course of advanced dementia. N Engl J Med 2009;361:1529–1538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van der Steen JT, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, Knol DL, et al. : Caregivers' understanding of dementia predicts patients' comfort at death: A prospective observational study. BMC Med 2013;11:105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Helton MR, van der Steen JT, Daaleman TP, et al. : A cross-cultural study of physician treatment decisions for demented nursing home patients who develop pneumonia. Ann Fam Med 2006;4:221–227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]