Abstract

Therapy with autologous T cells that have been gene-engineered to express chimeric antigen receptors (CAR) or T cell receptors (TCR) provides a feasible and broadly applicable treatment for cancer patients. In a clinical study in advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC) patients with CAR T cells specific for carbonic anhydrase IX (CAIX), we observed toxicities that (most likely) indicated in vivo function of CAR T cells as well as low T cell persistence and clinical response rates. The latter observations were confirmed by later clinical trials in other solid tumor types and other gene-modified T cells. To improve the efficacy of T cell therapy, we have redefined in vitro conditions to generate T cells with young phenotype, a key correlate with clinical outcome. For their impact on gene-modified T cell phenotype and function, we have tested various anti-CD3/CD28 mAb-based T cell activation and expansion conditions as well as several cytokines prior to and/or after gene transfer using two different receptors: CAIX CAR and MAGE-C2(ALK)/HLA-A2 TCR. In a total set of 16 healthy donors, we observed that T cell activation with soluble anti-CD3/CD28 mAbs in the presence of both IL15 and IL21 prior to TCR gene transfer resulted in enhanced proportions of gene-modified T cells with a preferred in vitro phenotype and better function. T cells generated according to these processing methods demonstrated enhanced binding of pMHC, and an enhanced proportion of CD8+, CD27+, CD62L+, CD45RA+T cells. These new conditions will be translated into a GMP protocol in preparation of a clinical adoptive therapy trial to treat patients with MAGE-C2-positive tumors.

Introduction

The use of receptor gene therapy, in which a patient's own T cells are gene-modified with either a tumor-specific chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) or a T cell receptor (TCR), has broadened the clinical applicability of adoptive therapy with antigen-specific T cells to treat tumors. Initial trials using gene-modified T cells to treat various tumor types did not show antitumor responses in a substantial number of patients (Kershaw et al., 2006; Morgan et al., 2006; Till et al., 2008; Johnson et al., 2009; Lamers et al., 2013a,b). Despite that some recent trials using either a CD19 CAR to treat B cell leukemias (Kalos et al., 2011; Davila et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2014; Maude et al., 2014) or an NY-ESO TCR to treat melanoma and synovial carcinoma (Robbins et al., 2011) showed significant clinical activities, the majority of the studies performed so far fail to demonstrate substantial antitumor effects (Gilham et al., 2012; Kunert et al., 2013). One of the underlying reasons for these disappointing results might be a low persistence of these gene-modified T cells (Robbins et al., 2004; Huang et al., 2005). Persistence of T cells is associated with the immunogenicity of the transgene (Lamers et al., 2011, 2013a), but also with the differentiation state and replicative history of transferred T cells with the longest persistence for those T cells with a more naïve phenotype (Klebanoff et al., 2005; Hinrichs et al., 2009).

Various studies have shown that the T cell phenotype depends on T cell activation and expansion conditions (Duarte et al., 2002; Bondanza et al., 2006; Pouw et al., 2010b). Along this line, retroviral TCR engineering of primary murine T cells has been reported to benefit from T cell activation with a combination of soluble anti-CD3 and CD28 rather than immobilized anti-CD3 and CD28 mAbs in terms of a more favorable T cell differentiation state and better antigen-specific T cell responses (Pouw et al., 2010b). In addition, recent studies demonstrated that common-γ cytokines interleukin-2 (IL2), IL7, IL15, and IL21 play important roles in skewing or slowing down T cell differentiation (Hinrichs et al., 2008; Kaneko et al., 2009; Pouw et al., 2010b; Yang et al., 2013). In fact, short-term exposure of primary murine T cells to both IL15 and IL21 resulted in a significant enrichment of CD62Lhi, CD44lo, CD27int, and CCR7hi T cells (phenotypical definition of naïve T cells), which was paralleled by decreased expression of genes involved in T cell differentiation and increased expression of genes involved in T cell survival (Pouw et al., 2010a). Accordingly, patient studies, in which T cells were costimulated with anti-CD28 antibody or artificial antigen presenting cells and in the presence of IL2 and IL15, have demonstrated a long persistence of adoptively transferred T cells in the peripheral blood (up to 6–12 months) (Butler et al., 2011; Kalos et al., 2011). Notably, inclusion of renewed T cell-processing methods relieved the requirement for patient preconditioning with chemotherapy (Butler et al., 2011) and/or in vivo IL2 administration (Kalos et al., 2011).

To assess the impact of activation, cytokines added, and timing of adding these cytokines on the resulting phenotype and function of gene-modified T cells, we have compared in this study our standard protocol for T cell activation, gene transduction, and expansion (using soluble anti-CD3 mAb and IL2) with various anti-CD3/CD28 mAb-based T cell activation methods and cytokine additions using two different receptors: carbonic anhydrase IX (CAIX) CAR (Lamers et al., 2013a) and MAGE-C2(ALK)/HLA-A2 TCR (Straetemans et al., 2012).

Materials and Methods

Cells, media, and reagents

Peripheral blood buffy coat units were obtained from healthy volunteers after written informed consent through the local blood bank (Sanquin SWN, Rotterdam, The Netherlands). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated as described (Lamers et al., 2002) and cryopreserved in aliquots and stored in liquid nitrogen until use. Target cell lines were CAIXpos renal cell carcinoma (RCC) cell line SKRC-17 MW1-clone 4, CAIXneg RCC cell line SKRC-17 PBJ-clone 1, melanoma cell line EB-81-MEL-2 (MC2pos/A2pos, also known as Daju), and the MC2neg/A2pos B lymphoblast cell line (BLCL) BSM. The Daju cell line is derived from the same patient from who the T cell clone CTL-606C/22.2 (EB81CTL 16) (Lurquin et al., 2005) and its MC2-specific TCR genes have been derived (Schneiders et al., 2012). In some cases, Daju cells were pretreated with 50 pg/ml human recombinant IFNγ (Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ) for 48 hr prior to functional T cell assays to enhance antigen presentation.

PBMC were cultured in a MixMed (Lamers et al., 1992), that is, 80% RPMI-1640 (Lonza, Verviers, Belgium) and 20% AIMV (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 2 mm L-glutamine (Lonza), 50 μg/ml gentamycin (Centrafarm, Etten-Leur, The Netherlands), 2 IU/ml heparin (Leo, Ballerup, Denmark), and 2% pooled AB plasma (complete Mix Med). Cell lines were cultured in DMEM or RPMI-1640 media (both from Lonza) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Greiner Bio-one Alphen a/d Rijn, The Netherlands), 2 mM L-glutamin, 1% nonessential amino acids (Lonza), and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Lonza). The HLA-A2-binding peptides MC2 (ALKVDVEERV) and (as a control) gp100280–288 (YLEPGPVTA) were from Eurogentec (Maastricht, The Netherlands), and the MC2/A2 peptide MHC (pMHC) monomer complexes labeled with biotin were purchased from Sanquin (Amsterdam, The Netherlands) and Streptavidin-PE from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA). Pytohemagglutinin (PHA) was from Remel Ltd. (Lenexa, KS) and phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Retroviral supernatants

In this study we used the validated clinical CAIX CAR vector batch (batch #M4.50086; BioReliance, Sterling, UK) (Lamers et al., 2006a). For production of an MC2 TCR vector batch, we generated a stable Phoenix-Ampho packaging cell line, isolated an optimal producer clone, and produced an MC2 TCR vector batch, and stored a series of ready-to-use aliquots at −80°C according to procedures described elsewhere (Schneiders et al., 2012; Lamers et al., 2013b).

T cell activation, transduction, and expansion conditions

Experimental conditions tested in this article are as follows (for details see Table 1):

1. T cell activation with soluble anti-CD3 mAb at 10 ng/ml (sCD3); soluble anti-CD3 mAb+anti-CD28 mAb each at 30 ng/ml (sCD3+28); or CD3+CD28 mAb-coated cell-sized T cell activation beads, MACSibead CD3+28 (T cell activation/Expansion kit) (MbCD3+28), or Dynabead CD3+28 (Dynabeads Human T-Activator CD3/CD28) (DbCD3+28), according to manufacturing's instruction (n=6–12 PBMC).

2. Addition of IL2 at 360 IU/ml interleukin 2 (IL2); IL7+IL15 at 10+10 ng/ml (IL7+15), or IL15+IL21 at 10+10 ng/ml (IL15+21). PBMC were activated using sCD3+28, transduced, and expanded from day 4 in the presence of mentioned cytokines (n=6–12 PBMC).

3. Timing of cytokine addition (see point 2) at culture day 4 (i.e., after transduction) or start of culture (i.e., at day 0). PBMC were activated with sCD3+28 (n=6 PBMC).

Table 1.

T Cell Activation and Expansion Reagents

| Activation agents | mAb (clone) | Concentration | Provider |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soluble CD3 | Anti-CD3 (OKT3; IgG2a) | 10 ng/ml | Cilag (Beerse, Belgium) |

| Soluble CD3/CD28 | Anti-CD3 (OKT3; IgG2a) Anti-CD28 (15E8; IgG1) |

30 ng/ml e.a. | Miltenyi (Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) |

| MACSiBead CD3/CD28a | Not specified | MACSiBead:cell ratio, 1:2 | Miltenyi |

| Dynabead CD3/CD28b | Not specified | Dynabead:cell ratio, 1:1 | Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA) |

| Cytokines | Specific activity | Concentration | Provider |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interleukin-2 (IL-2) | 1.6×107 IU/mg | 360 IU/ml | Chiron (Amsterdam, The Netherlands) |

| IL-7 | ≥5×107 U/mg | 10 or 50 ng/ml | Miltenyi |

| IL-15 | ≥2×106 U/mg | 10 or 50 ng/ml | Miltenyi |

| IL-21 | ≥1×104 U/mg | 10 or 50 ng/ml | Miltenyi |

MACSiBeads (T Cell Activation/Expansion Kit; Cat. No. 130-091-441) were loaded according to manufacturer's instructions at 1×108 beads+10 μg of each mAb in 1 ml for at least 2 hr at 2–8°C and washed just prior to use.

Dynabeads Human T-Activator CD3/CD28 (Cat. No. 111.31D).

Our standard protocol (Lamers et al., 2002, 2006c) includes T cell activation in complete MixMed using sCD3 and addition of IL2 during T cell transduction (i.e., days 2 and 3) at 100 IU/ml and during the expansion phase (i.e., from day 4 onward) at 360 IU/ml IL2. At days 2 and 3, T cells were transduced in non-tissue culture-treated 24-well plates (Falcon, Franklin Lakes, NJ) coated with 3 μg/cm2 recombinant fibronectin fragment CH-296 (retronectin; Takara Shuzo, Otsu, Japan) as described (Lamers et al., 2006c). From day 4 onward, T cells were expanded and initially seeded at 0.2×106 cells/ml in complete MixMed supplemented with cytokines in tissue culture flasks. Lymphocytes were counted every 2–3 days and adjusted to 0.5×106 cells/ml by adding fresh culture medium until day 15. T cell growth is expressed as fold increase, that is, cell number at a particular day divided by the cell number at day 2.

Flow cytometry

Transduced T cells were analyzed at days 7, 11, and 14 for surface expression of the introduced CAR or TCR. The expression of the CAIX CAR receptor was assessed by indirect immunofluorescence using the G250 anti-idiotype mAb NUH82 (IgG1) (Uemura et al., 1994), kindly provided by Dr. E. Oosterwijk (Nijmegen, The Netherlands), followed by GAM IgG1/PE as described (Lamers et al., 2002); the MC2 TCR expression was determined by using the anti-TCR-Vβ3-specific mAb and PE-labeled MC2 pMHC multimer (10 nM). T cell cultures were analyzed for major lymphocyte subsets, that is, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, NK cells (CD3−CD56+), Tregs (CD4+, CD25+, CD127−), and T cell differentiation subsets based on differential expression of surface markers CD27, CD28, CD45RA, CD45RA, CD62L, and CCR7. Information on antibodies and staining combinations used in multicolor flow cytometry (FCM) is specified in Supplementary Table S1 (Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/hgtb).

Cytotoxicity assay

Specific and nonspecific cytolysis was analyzed at day 15 in a standard 4–6 hr 51Cr-release assay as described (Lamers et al., 2002): CAIX CAR-specific cytolysis was tested in co-cultivation with CAIX+ and CAIX− RCC cell lines; the antigen specificity was verified by blocking the antigen on the target cells by the CAIX mAb G250 (Lamers et al., 2002). MC2/A2 TCR-specific cytolysis was assessed using the cell line Daju and BSM loaded with either MC2 or (as a control) the gp100 peptide. Peptide loading of target cells (final conc. at 10 μM) was performed for 15 min at 37°C and 5% CO2 prior to cocultivation with effector cells. Nonspecific cytolysis was assessed using the activated kill (AK)-sensitive Burkitt's lymphoma cell line Daudi. The percentage of specific cytolysis was expressed as weighted mean of specific lysis (WMSL) at effector cell-to-target cell ratio of 20:1, as described (Lamers et al., 2006c).

IFNγ production

To quantify the production of IFNγ, 6×106 T cells were cultured in the presence of 2×106 target cells for 18 hr at 37°C and 5% CO2. As a positive control, T cell transductants were stimulated with PHA and PMA. Supernatants were harvested and levels of IFN-γ were determined by standard ELISA (Sanquin, Amsterdam, The Netherlands).

Statistical analysis

We performed side-by-side comparisons resulting in paired data sets. The matched Student's t-test was used to compare data from two experimental conditions. All tests were two-sided, and p-values smaller than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

T cell activation: most optimal with sCD3+CD28 mAbs

In the first series of experiments, T cell activation conditions tested included soluble anti-CD3 mAb (sCD3); soluble CD3+soluble anti-CD28 mAb (sCD3+28); and MACSiBeads coated with anti-CD3+anti-CD28 mAbs (bCD3+28). PBMC from healthy donors were activated for 2 days and then transduced with either the CAIX CAR or MC2/A2 TCR. Subsequently, T cells were cultured for 2 weeks in MixMed supplemented with IL2, and monitored for (1) T cell proliferation, (2) transduction efficiency, (3) T cell cytotoxicity and IFN-γ production, and (4) T cell subset distribution and T cell differentiation.

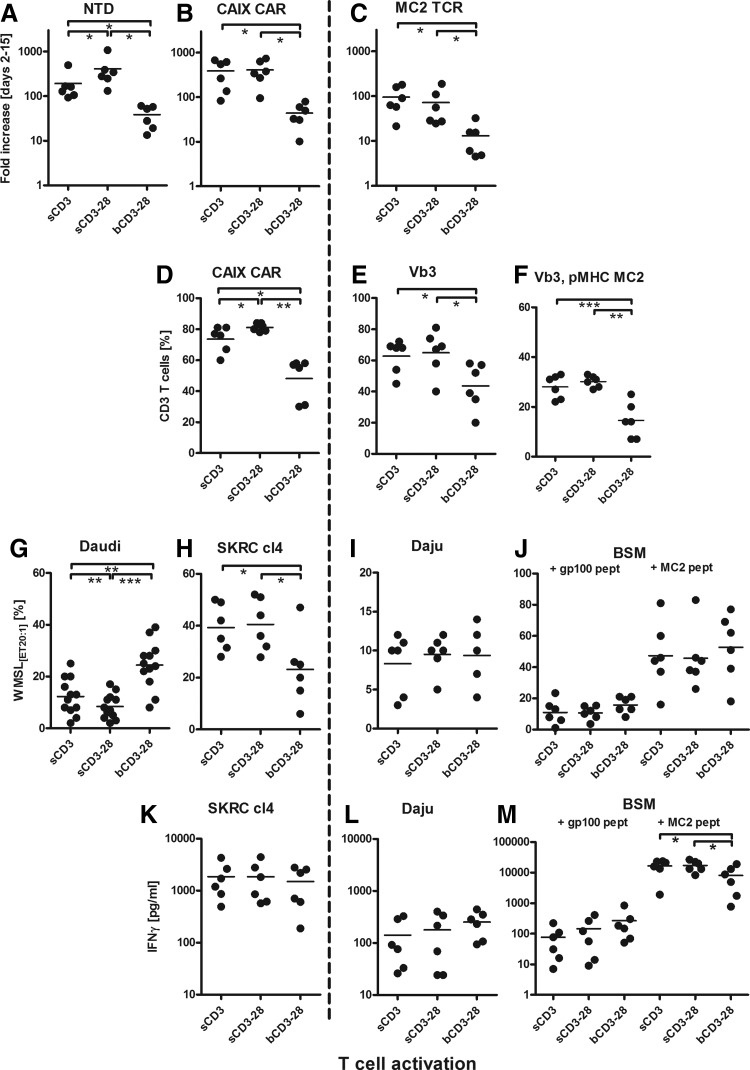

Data presented in Figs. 1 and 2 show that T cell activation by sCD3 and sCD3+28 induced a similar level of T cell proliferation (Fig. 1A–C). It is noteworthy that we observed significantly lower proliferative ability for MC2 TCR (median, 60-fold increase; range 17–237) versus CAIX CAR (median, 350; range 95–734)-transduced T cells (Fig. 1B and C; p=0.001). The transduction efficiency of CAIX CAR was highest following activation with sCD3+28 (CAIX CAR+ T cells: mean 81%, range 78–84%), whereas the transduction efficiency of MC2 TCR was equally high following activation with sCD3 (Vb3+pMHC MC2+ T cells: mean 29%, range 22–33) or sCD3+28 (mean 31%, range 27–33); Fig. 1D–F). Functional tests showed lowest nonspecific cytolysis by transduced T cells following sCD3+28 activation (Fig. 1G). In addition, the highest CAIX CAR-specific cytolysis was measured following sCD3 and sCD3+28 activation (Fig. 1H). No significant differences were seen for CAIX CAR-specific IFN-γ production between the three activation conditions (Fig. 1K).

FIG. 1.

Effects of T cell activation conditions on T cell proliferation, transduction, and function. Healthy donor T cells (n=6) were activated at day 0 with (1) sCD3, (2) sCD3+28, or (3) bCD3+CD28 (see Table 1 for details on T cell activation reagents), all without addition of exogenous cytokines. At days 2–3 T cells were transduced with the CAIX CAR, a MAGEC2/A2 (MC2) TCR, or mock (not transduced, NTD) on retronectin-coated plates in the presence of 100 IU/ml IL2 (Chiron). From days 4–15, T cells were expanded in medium supplemented with 360 IU/ml IL2. T cells were monitored for proliferation, expressed as fold increase in cell number from start of transduction, that is, between days 2 and 15 (A–C); transduction efficiency expressed as % CAIX CAR+ T cells (D), % TCRVb3+ T cells (E), or % TCRVb3+, MC2-pMHC+ T cells (F), in which each data point represents average values for single donors measured at days 7, 11, and 15. T cells were also monitored for cytolytic activities, expressed as % weighted mean of specific cytolysis at effector-to-target cell ratio of 20:1 using T cell cultures from day 15 and using SKRC-cl4 (H), Daju (I), BSM loaded with irrelevant gp100 or relevant MC2 peptide (J), or Daudi (G; combined results of both CAR transduced and NTD T cells). Lastly, T cells were monitored for IFNγ production expressed as pg/ml using T cell cultures from day 15 and using SKRC-cl4 (K), Daju (L), and peptide-loaded BSM stimulator cells (M). Cell recovery following activation (day 0–2) was for soluble CD3 mAb 60% (median, range 32–78%, n=6), for soluble CD3+CD28 mAbs 63% (median, range 54–86%, n=6), and for Miltenyi CD3/28 beads 74% (median, range 32–85%, n=6). Graphs represent individual and median values (bars). *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001 using two-sided paired t-tests.

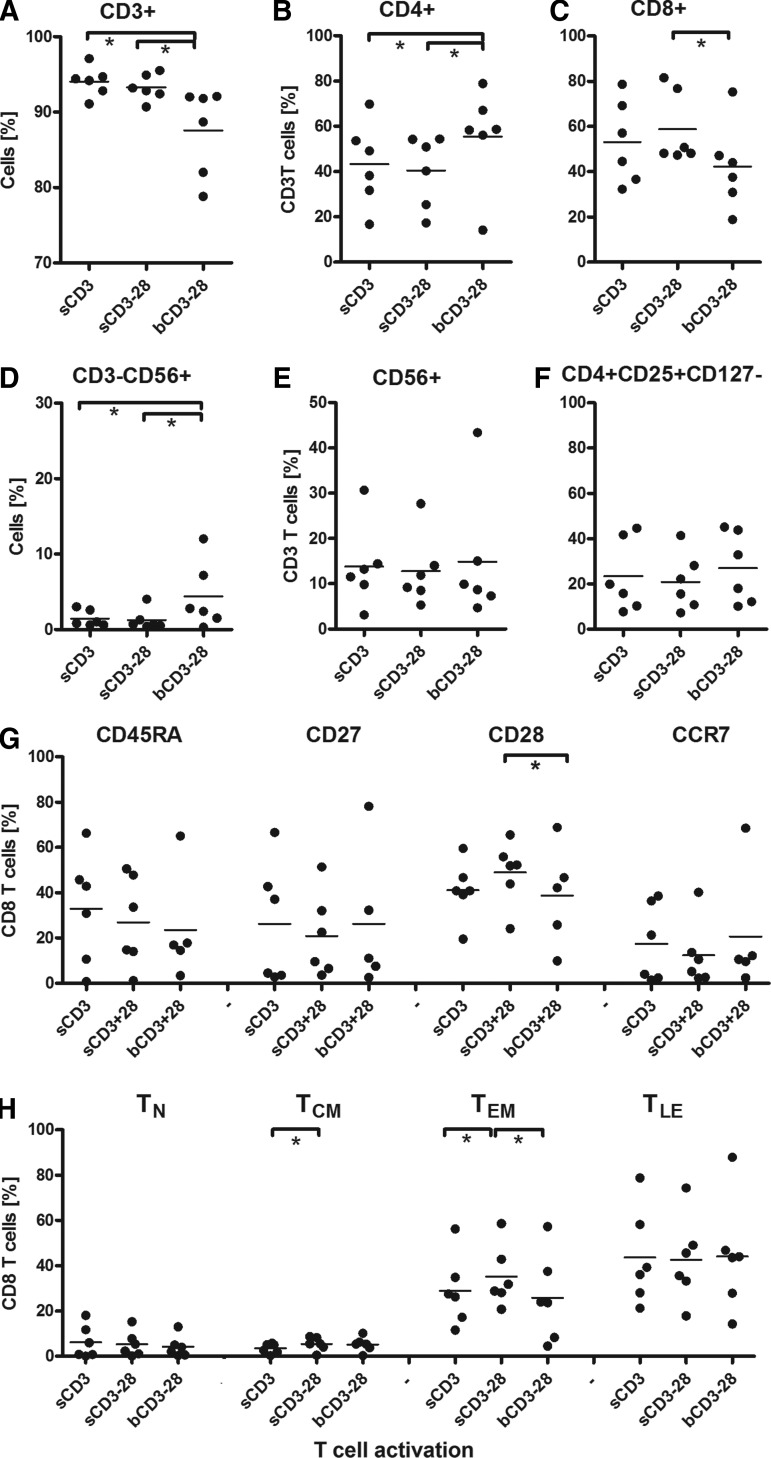

FIG. 2.

Effects of T cell activation conditions on lymphocyte subsets and T cell differentiation. T cell cultures (n=6), activated and transduced with the MC2/A2 TCR, as described in legend to Fig. 1, were monitored at culture day 15 for the following lymphocyte subsets CD3+ (A); CD4+ (B); CD8+ (C); CD3−, CD56+ (D); CD3+,CD56+ (E); CD4+, CD25+, CD127− (F); the markers CD45RA, CD27, CD28, and CCR7 (G); and T cell differentiation stages: T-Naïve (TN=CD45RA+27+28+CCR7+), T-central memory (TCM=CD45RA-27+28+CCR7−/+), T-effector memory (TEM=CD45RA−27–28+CCR7−), and T-late effector (TLE=CD45RA−/+27–28-CCR7−) (H). Graphs represent individual and median values. Statistics: see legend to Fig. 1.

MC2-specific T cell functions (Fig. 1I, J, L, and M) were similar for all three activation conditions, with a trend for higher IFN-γ production following MC2 peptide stimulation upon activation with sCD3 or sCD3+28. T cell activation by bCD3+28 resulted not only in the lowest T cell proliferation (Fig. 1A–C) and T cell transduction efficiency (Fig. 1D–F), but also in lowest proportions of CD3+ and CD3+CD8+ T cells (Fig. 2A–C), and the highest proportions of NK cells (Fig. 2D) and potentially as a result the highest level of nonspecific cytolysis (Fig. 1G). No effects of T cell activation were seen on the relative numbers of CD3+CD56+ T cells and CD4+CD25+CD127− T cells (Fig. 2E and F). Activation by sCD3 and sCD3+28 resulted in similar proportions of T lymphocyte subsets, with slightly higher proportions of CD28+ and central memory (Tcm) and effector memory (TEM) T cells after sCD3+28 activation (Fig. 2G and H).

In an additional experiment, we compared T cell activation by sCD3+CD28 mAb, MACSibead CD3/28 (MbCD3+28), and Dynabead CD3/28 (DbCD3+28) and showed that DbCD3+28 activation induced enhanced T cell proliferation, lowered expression of TCR transgene, lowered T cell functions, higher proportion of CD4+CD25+CD127− T cells, and a lowered proportion of differentiated effector T cells, as detailed in Supplementary Data and Supplementary Figs. S1–S3.

Altogether, findings are summarized in Table 2A and point out that retroviral receptor engineering of primary human T cells benefits most from activation with sCD3+28.

Table 2.

Summary of Effect of T Cell Activation, Cytokines, and Timing of Cytokine Addition on T Cell Parameters

| T cell activation | Cytokine | T cell expansion,aCAIX/MC2 | Receptor expression,bCAIX/MC2 | Nonspecific responsec | T cell CTX response,dCAIX/MC2 | T cell IFN-γ response,eCAIX/MC2 | T cells, CD3+8+f | NK cellsg | Tnh |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A)T cell activation | |||||||||

| Soluble CD3 | IL-2 | +++/++ | +++/++ | + | ++/− | +++/+ | +++ | + | ++ |

| Soluble CD3/CD28 | IL-2 | +++/++ | +++/++ | − | +++/+ | +++/+ | +++ | + | ++ |

| MACSibead CD3/CD28 | IL-2 | +/+ | ++/+ | ++ | ++/− | +++/++ | ++ | ++ | + |

| Dynabead CD3/CD28 | IL-2 | nd/+++ | nd/++ | − | nd/+ | nd/+ | ++ | + | + |

| (B)Cytokine addition | |||||||||

| Soluble CD3/CD28 | IL-2 | +++/++ | +++/++ | + | ++/+ | ++/++ | +++ | + | ++ |

| Soluble CD3/CD28 | IL-7+IL-15 | +++/++ | +++/++ | + | ++/++ | +++/++ | +++ | + | + |

| Soluble CD3/CD28 | IL-15+IL-21 | +++/+++ | +++/++ | + | +++/+++ | +++/++ | ++++ | + | ++ |

| (C)Timing of cytokine addition (MC2 TCR—result day 0/day 4)i | |||||||||

| Soluble CD3/CD28 | IL-2 | ++/++ | +++/+++ | +/+ | +/++ | ++/++ | +++/+++ | +/++ | ++/++ |

| Soluble CD3/CD28 | IL-7+IL-15 | ++/++ | +++/+++ | +/+ | ++/++ | ++/++ | +++/+++ | +/++ | ++/++ |

| Soluble CD3/CD28 | IL-15+IL-21 | ++/++ | +++/+++ | +/+ | ++/++ | ++/++ | ++++/+++ | +/++ | +++/++ |

nd, no data.

T cell expansion (fold increase from day 2 to day 15) of CAIX CAR/MC2 TCR transduced T cells: −, <10;+, 10–50;++, 51–200;+++, >200-fold.

Expression of transgene; average of three measurements at days 7, 11 and 15: −, <5%;+, 5–20%;++, 21–50%;+++, 51–80%;++++, >80%+ve.

Nonspecific kill of Daudi target cells; pooled data of CAIX CAR and MC2 TCR transduced T cells (day 15): −, <5%;+, 6–20%;++, 21–40%;+++, >40% specific 51Cr release.

Cytolysis (day 15) by CAIX CAR T cells (target cell SKRC-cl4) and MC2 TCR T cells (target cell Daju)–values are corrected for medium (background) values: −, <5%;+, 6–20%;++, 21–40%;+++, >40% specific 51Cr release+.

IFN-γ production (day 15) by CAIX CAR T cells (target cell SKRC-cl4) and MC2 TCR T cells (target cell Daju); values are corrected for medium (background) values: −, <100;+, 100–200;++, 200–1000;+++, >1000;++++, >10,000 pg/ml IFNg.

Proportion CD8+ of CD3+ T cells (pooled data CAIX CAR/MC2 TCR transduced T cells at culture day 15): −, <5%;+, 5–20%;++, 21–50%;+++, 51–80%;++++, >80%+ve.

Proportion CD56+ NK cells of CD3 cells (pooled data CAIX CAR/MC2 TCR transduced T cells at culture day 15): −, <1%;+, 1–5%;++, 6–15%;+++, >15%.

Proportion of naïve T cells of CD8+ T cells (TN=CD45RA+27+28+CCR7+; of MC2 TCR transduced T cells at culture day 15): −, <1%;+, 1–5%;++, 6–10%;+++, >10%+ve. See legend to Fig. 2 for details.

MC2 TCR-transduced T cell cultures only, with addition of cytokines from day 0 and from day 4 (day 0/day 4).

Cytokine additions: most optimal with IL15+21

In a second series of experiments, T cells were activated with sCD3+28, transduced with the CAIX CAR or MC2 TCR, and expanded using IL2, IL7+15, or IL15+21. Dose–response studies with IL7, IL15, and IL21 (50 vs. 10 ng/ml) revealed no effect on T cell proliferation, transduction efficiency, function, and phenotype (see Supplementary Fig. S4).

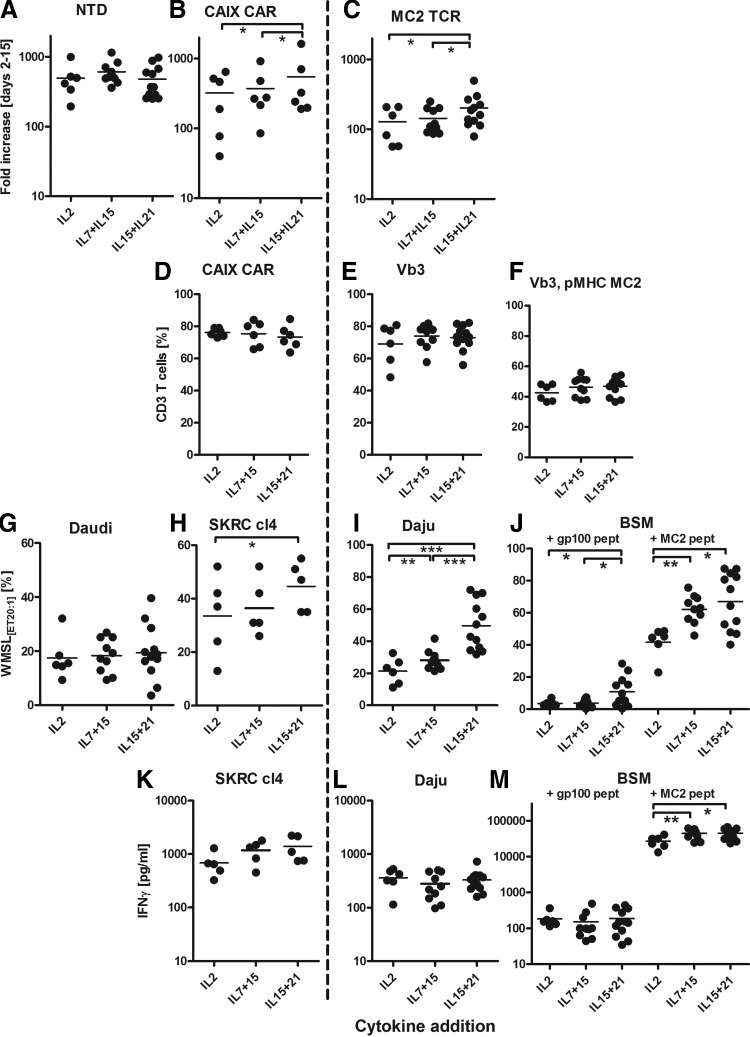

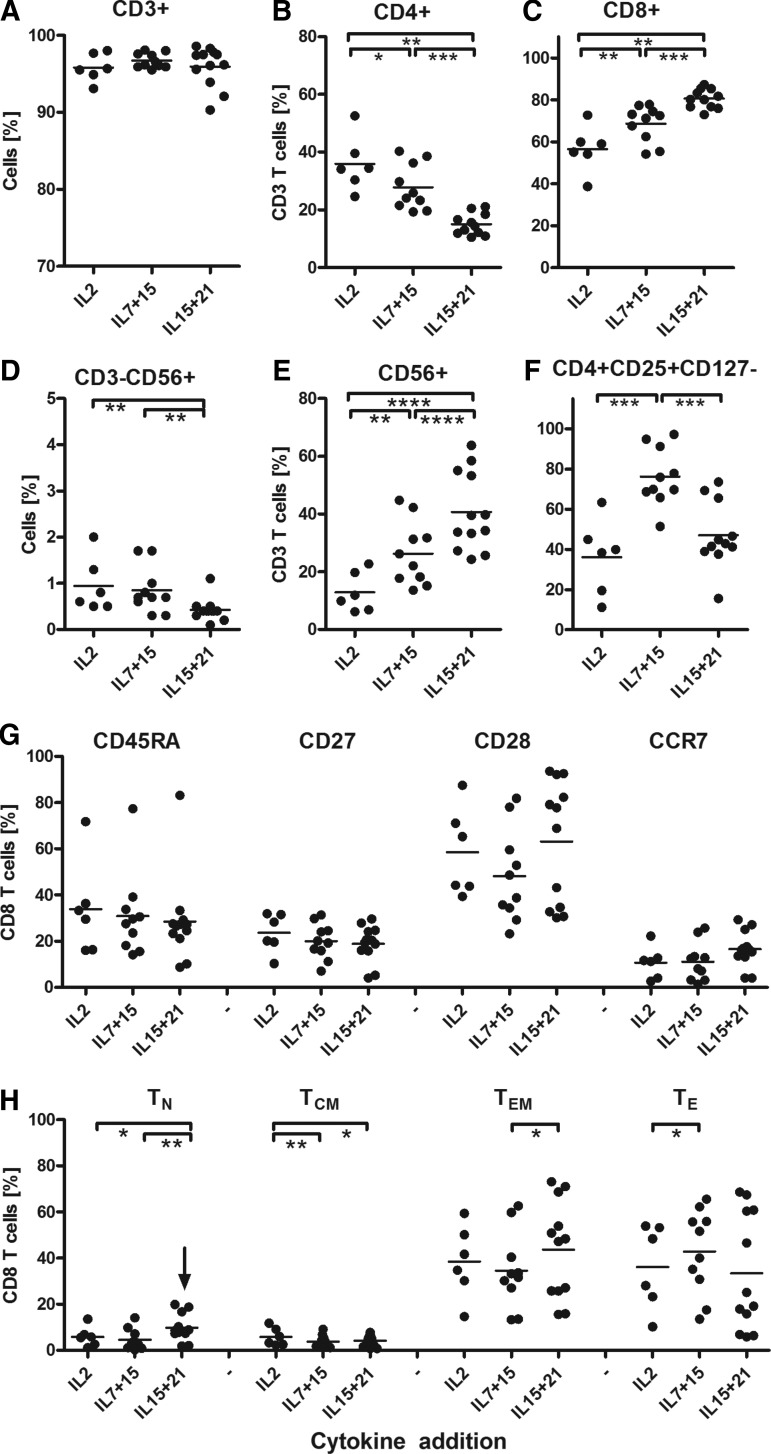

Data presented in Figs. 3 and 4 show that T cells proliferated best in IL15+21 (CAR T cells: median fold increase 283 [range 190–1624]; MC2 TCR T cells, 173 [range 79–495]) and proliferated least in IL2-supplemented medium (Fig. 3A–C). The three different sets of cytokines had no significant effect on the expression level of the transgenes (% CAR T cells (combined) median 75 [range 64–85];% MC2 TCR T cells (combined), median 47 [range 37–56]; Fig. 3D–F). Nevertheless, IL15+21 induced the highest CAIX CAR and MC2 TCR-mediated T cell functions. In fact, cytolysis of both cognate antigen-expressing tumor cells and peptide-loaded target cells (Fig. 3H–J), as well as IFNγ production in response to peptide-loaded target cells were increased upon culture with IL15+21 (Fig. 3K–M). When compared to IL2-supplemented medium, addition of IL7+15 promoted stronger outgrowth of CD8+ T cells (% CD8+ was 62 [range 45–75) for IL2 and 74 [range 56–81] for IL7+15), which was even further increased when using IL15+21 (% CD8+ was 85 [range 69–89]; Fig. 4A–C). Furthermore, the combination of the cytokines IL15+21 resulted in the lowest proportions of CD3−CD56+ NK cells and highest proportions of CD3+,CD56+ T cells (Fig. 4D and E), yet the activated kill-activity (Fig. 3G) was similar for all three sets of cytokine additions.

FIG. 3.

Effects of cytokine additions on T cell proliferation, transduction, and function. Healthy donor T cells (n=6–12) were activated at day 0 with sCD3+28 and transduced with the CAIX CAR or MC2/A2 TCR as described in legend to Fig. 1. From days 4–15, T cells were expanded in medium supplemented with (1) IL2, (2) IL7+15, or (3) IL15+21 (see Table 1 for details on cytokine additions). Observations from T cell cultures using different cytokine concentrations were pooled since titrated amounts of cytokines did not differently affect T cell parameters (Supplementary Fig. S1). T cell cultures were monitored and tested as described in legend to Fig. 1.

FIG. 4.

Effects of cytokine additions on lymphocyte subsets and T cell differentiation. T cell cultures (n=6–12) activated and transduced with the MC2 TCR as described in legend to Fig. 3 were monitored for the lymphocyte subsets as described in legend to Fig. 2.

The presence of IL7 in the culture medium down-modulated the IL7 receptor (CD127) on T cells, resulting in a higher proportion of CD4+, CD25++, CD127− cells when T cells were cultured in the presence of IL7+15 (Fig. 4F). Yet this in vitro-generated “Treg phenotype” is not associated with signs of decreased T cell reactivity. Although the expression of differentiation markers showed no significant differences between the cultures, the IL15+21-supplemented medium resulted in the highest frequency of naive T cells (TN, median 8%, range 2–19%) and relatively more effector memory cells (TEM, median 48%, range 16–73%) versus late effector cells (TLE, median 22%, range 6–67%) in comparison to IL2 or IL7+15-supplemented medium. For these latter cultures the proportions of Tem were 38% (median, range 15–59%) and 32% (median, range 13–63%) and proportions of Tle were 38% (median, range 10–54%) and 46% (median, range 14–66%), respectively (Fig. 4H). Findings are summarized in Table 2B and point out that retroviral receptor engineering of primary human T cells benefits most from addition of IL15+21 to the culture medium.

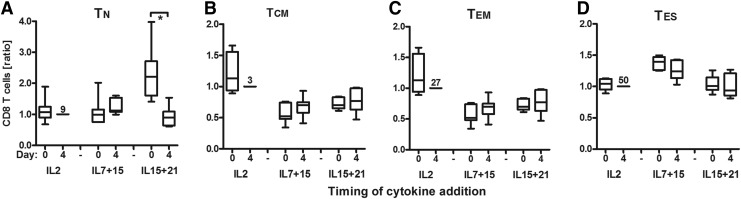

Timing of cytokine additions: most optimal at start of T cell activation

In a third set of experiments, we assessed the effects of IL15+21 on T cell differentiation, in particular the impact of timing of cytokine addition. To this end, T cells were activated with sCD3+28, transduced with the MC2 TCR, and expanded with IL2, IL7+15, or IL15+21 cytokines, either from culture day 4 onward (start of T cell expansion phase, as above) or from day 0 onward (i.e., start of T cell activation according to Kaneko et al., 2009).

Data presented in Fig. 5 show that T cells that were exposed to IL15+21 at day 0 compared to day 4 contained significantly more CD8+ T cells with a naïve phenotype (i.e., TN, median 16%, [range 2–25%] vs. 5% [range 1–19%]). This analysis was performed using a four-marker definition (including CD45RA, CD45RO, CD27, and CD62L) based on Gattinoni et al. (2006) to define T cell differentiation stages (see legend to Fig. 5 for details). When using a three-marker definition for these stages (Kaneko et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2011), the observed effect of IL15+21 added at day 0 did not differ from the four-marker analysis (Supplementary Fig. S5). With respect to other T cell parameters, we noted that addition of cytokines at day 0 promoted T cell proliferation for IL15+21 and IL7+15 cultures (Supplementary Fig. S6A). Transduction efficiency was enhanced when IL7+15 were added at day 0 (Supplementary Fig. S6B and C). No significant differences were seen for functional T cell parameters (see Supplementary Fig. S6E–I). Furthermore, addition of cytokines at day 0 increased numbers of CD8+ T cells for IL15+21 and IL7+15 but not of NK (CD3−CD56+) cells and CD56+ T cells and decreased proportions of CD4+CD25+CD127− T cells for IL15+21 (Supplementary Fig. S7A–F). In addition, IL15+21 added at day 0 increased the proportion of CD8+CD27+ T cells and decreased the proportion of CD8+CD45RO+ T cells, whereas IL7+15 decreased the proportion of CD8+CD27+ T cells (Supplementary Fig. S7G). No significant differences were seen for CD45RA and CD62L.

FIG. 5.

Effect of timing of cytokine addition on T cell differentiation. Healthy donor T cells (n=6) were activated with sCD3+28 and transduced with the MC2 TCR. Cultures were supplemented with IL2, IL7+15, or IL15+21 directly following T cell transduction (day 4) or directly following T cell activation (day 0). T cell cultures were monitored as described in the legends to Figs. 1 and 2; see Supplementary Figs. S3 and S4. T cells were monitored for T cell differentiation stages: T-naïve (TN=CD45RA+27+45RO−62L+) (A); T-central memory (TCM=CD45RA-27+45RO+62L+) (B), T-effector memory (TEM=CD45RA-27−45RO+62L+) (C), T-late effector (TLE=CD45RA−/+27−45RO+62L−) (D). Data are expressed relative to the IL2, day 4 condition (our current standard) and presented in box-and-whisker plots (horizontal line, median; box, interquartile range; whiskers, min–max range). The mean percentage of the condition “IL2 added from day 4 onward” is shown. Significant differences between addition of cytokines at day 0 versus day 4 are shown; see legend to Fig. 1.

Findings are summarized in Table 2C and point out that retroviral receptor engineering of primary human T cells benefits most from addition of IL15+21 from the start of T cell activation onward.

Discussion

In the current study, we have explored several methods for T cell activation, gene transduction, and expansion to generate gene-modified T cells with preferred in vitro phenotype and function. Our findings suggest that use of sCD3+CD28 mAbs and addition of IL15+21 from the start of T cell activation induces T cells with enhanced receptor expression, an enhanced proportion of CD8+ T cells with a naïve phenotype, a lower proportion of CD4+CD25+CD127− T cells, and enhanced receptor-mediated specific function.

T cell activation including CD28 co-signaling positively affects fitness and functional properties of T cells as evident from recent clinical trials (Gilham et al., 2012). T cell activation using mAbs requires cross-linking, for example, through Fc-binding on monocytes or coating to plates, beads, or human artificial APC (aAPCs) (Butler et al., 2011). Here we show that T cell activation of nonfractionated PBMC using sCD3+CD28 resulted in improved T cell proliferation, transduction efficiency, T cell responses, and numbers of CD8+ T cells when compared to MACSiBeads coated with anti-CD3+anti-CD28 mAbs. In addition, activation by Dynabeads CD3/CD28 versus sCD3+CD28 mAbs resulted in a stronger proliferation, but lower functional MC2 TCR transduction and diminished T cell differentiation. We conclude that retroviral receptor engineering of primary human T cells benefits most from T cell activation with sCD3+CD28. When sCD3+CD28 activation was combined with IL15+21 instead of IL2, enhanced functional MC2 TCR transduction and enhanced frequencies of “less differentiated” T cells were seen.

These observations are in line with our previous findings showing that retroviral TCR transduction of primary murine T cells benefited from activation by sCD3+CD28 rather than bCD3+CD28 with respect to minimal T cell differentiation and antigen specificity of T cell responses (Pouw et al., 2010b). However, our Dynabead CD3/CD28 results contrast with these previous murine data and current MACSibead CD3/CD28 findings with respect to T cell differentiation properties, but are in agreement with reports that state that Dynabead CD3/CD28 polyclonal activation of (non)fractionated PBMC is favorable to minimize T cell differentiation (Bondanza et al., 2006; Hollyman et al., 2009; Kaneko et al., 2009).

Currently, many groups exploring the application of adoptive engineered T cells tend to the use of CD3 stimulation and CD28 costimulation using antibodies immobilized to cell-sized beads for clinical application. It is anticipated that such activation mimics T cell activation with sCD3/CD28 in the presence of monocytes. Although our method is limited to nonfractionated PBMC products, it has proven practical, has economic advantages, and does not need a bead elimination step for clinical T cell products prior to infusion.

T cell expansion was performed in the presence of common-γ cytokines other than IL2, as recent studies suggest that cytokines such as IL7, IL15, and IL21 play important roles in T cell differentiation (Klebanoff et al., 2004; Gattinoni et al., 2005, 2009; Hinrichs et al., 2008, 2011; Kaneko et al., 2009) and in vivo T cell function. In mouse models, the engraftment of less differentiated human TCM cells (CD45RO+CD62L+) appeared dependent on IL15 and resulted in superior magnitude and duration of engraftment compared to the more differentiated TEM cells (CD45RO+CD62L−) (Wang et al., 2011). Compared to IL2, the addition of IL15+21 versus IL2 or IL7+15 resulted in improved T cell proliferation, T cell responses, and proportions of CD8+ T cells. Despite the fact that individual T cell differentiation markers did not show significant shifts, the differentiation stages defined by these markers did.

The relative numbers of T cells with Tn and Tcm phenotype were significantly increased in IL15+21-supplemented cultures. These data suggest that IL15+21 prevents conversion from Tn to Tcm cells and from Tem to Tle cells or drive selective proliferation resulting in an overall less differentiated phenotype. These data are in agreement with previously reported data for murine CD8+ T cells (Pouw et al., 2010a). Nevertheless, although these culture conditions significantly impact the frequency of less differentiated cells, this is clearly in the presence of an absolute number of cells that are predominantly of a more differentiated phenotype. Moreover, in vitro phenotype and function of less differentiated T cells may mask the full in vivo potential of these cells (Kaneko et al., 2009). Therefore, analysis of the in vivo properties of IL15+21 cultured T cells is warranted and part of the translation of these data toward a future clinical trial. These in vivo studies have been initiated but are not part of the current article.

Our results on the effect of IL15+21 on gene-modified T cell phenotype and function are supported by previous observations by Huarte et al. (2009), who generated antigen-specific T cells by in vitro stimulation with class I and class II melanoma peptide pulsed dendritic cells. When T cells were generated in the presence of IL-15+21 but not IL2, they observed skewing toward a less differentiated T cell phenotype, a lower proportion of regulatory cells, higher number of CD8+, and a higher yield of cells with a greater cytolytic activity and IFN-γ production against melanoma cell lines. In addition, observations by (Markley and Sadelain (2010), who studied in a xenogeneic adoptive transfer model the effectivity of CD19-specific human primary T cells, also support our findings. They showed that IL-7- and IL-21-transduced T cells persisted the longest and were the most efficacious in vivo, although their ex vivo effector functions were not as enhanced as IL-2- and IL-15-transduced T cells.

In extension to the two above-mentioned studies, we have used a large set of healthy human donors and demonstrated that T cell activation with soluble anti-CD3/CD28 mAbs and T cell exposure to IL15+21 provides enhanced binding of pMHC and an enhanced proportion of less-differentiated T cells. Importantly, we have tested these T cell processing conditions using T cells that were gene transferred with either CAR or TCR genes, making our findings relevant to future trials with gene-modified T cells.

With respect to added cytokines, our studies showed the importance of timing relative to T cell activation. Adding cytokines directly from the start of T cell activation generally improved T cell proliferation. IL7+15 increased the proportion of CD8+ T cells but decreased the proportions of CD8+CD27+ T cells and naïve CD8+ T cells. In contrast, addition of IL15+21 from the start of T cell activation increased the proportions of CD8+ T cells, CD8+CD27+ T cells, and decreased the proportion of CD8+CD45RO+ T cells, and as a result increased the proportion of naïve CD8+ T cells. Thus, it seems that activation-driven T cell differentiation is best counteracted from an early moment onward.

It is hypothesized that long-living memory stem T cells (Gattinoni et al., 2011; Gattinoni and Restifo, 2013) with the ability to self-renew and the plasticity to differentiate into potent effectors could be valuable in adoptive T cell therapy. This T cell subset can be generated at clinical compliant conditions from naïve precursors using CD3/CD28 engagement and culture with IL7 and IL15 (Cieri et al., 2013). Yet previous studies also reported improved in vivo properties (persistence and specific function) of T cells cultured in IL7+15 versus IL2 (Liu et al., 2006; Kaneko et al., 2009), whereas the in vitro properties (phenotype and function) were similar. Thus in vitro properties of cultured human T cells may mask their in vivo potential. Here, we report an additional in vitro benefit for T cells generated in IL7+15 versus IL2 with respect to antigen-specific function and proportions of CD8+ and CD3+56+ T cells. On the contrary, IL7+15 generated the highest proportion of T cells with a Treg phenotype and a fully mature CD8 T cell effector phenotype. Therefore, we advocate the use of IL15+21 cytokines for the generation of engineered T cells for future evaluation.

In adoptive T cell clinical trials, an array of phenotypes have been applied with varying clinical successes (Brentjens et al., 2011; Kalos et al., 2011; Rosenberg et al., 2011; Kochenderfer et al., 2012). An association of phenotype and clinical successes has been suggested (Huang et al., 2005). In addition, data from preclinical animal models favor young TCR/CAR T cells (Tn, Tscm, and Tcm) as most efficacious subset(s) for adoptive transfer (Klebanoff et al., 2005; Hinrichs et al., 2009). These data warrant clinical evaluation of “conventional” versus “young” T cell phenotypes.

Besides T cell phenotype, also other aspects may hamper T cell persistence, such as the immunogenicity of the transgene construct. CAIX CAR T cells, activated by soluble anti-CD3 mAb and expanded with IL2, showed an effector T cell phenotype and only persisted for about 1 month after T cell infusion (Lamers et al., 2006b, 2013a; Lamers, article in preparation). Yet, this observation could not be attributed to T cell differentiation only, as the non-pre-conditioned patients developed a vigorous immune response to the CAIX CAR that coincided with the disappearance of the transferred cells from the circulation (Lamers et al., 2011).

The defined T cell processing conditions coincide with the generation of T cells with enhanced receptor-mediated function, such as cytokine (IFNγ) production. Importantly, one might question the desirability of augmented cytokine production given the reported cytokine release syndromes in recent adoptive CD19 CAR T cell therapy trials (Kalos et al., 2011; Kochenderfer et al., 2012; Brentjens et al., 2013; Grupp et al., 2013). However, a cytokine storm generally occurred several days to weeks after infusion of the T cells as a consequence of on-target T cell activation in patients with relatively bulky disease and can potentially be considered as a hallmark of therapy effectivity Yet, clinical surveillance is critical to control such a side effect. We have previously designed and validated a Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP)–compliant protocol for retroviral gene transduction and expansion of human T cells for a clinical study to treat patients with metastatic RCC using a CAR directed to CAIX (Lamers et al., 2002, 2006a, 2013a). Currently, conditions for T cell activation and expansion, revisited in the current article, are being translated in to a revised clinical applicable protocol to generate TCR-engineered T lymphocytes in preparation of a clinical-adoptive therapy trial to treat patients with MAGE-C2-positive tumors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Dutch Cancer Foundation (Grant EMCR 2011–5159), the Vereniging Trustfonds Erasmus University Rotterdam, and the European Union 6th framework grant (018914) entitled “Adoptive Engineered T Cell Targeting to Activate Cancer Killing (ATTACK).”

Author Disclosure Statement

Authors indicate no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Bondanza A., Valtolina V., Magnani Z., et al. (2006). Suicide gene therapy of graft-versus-host disease induced by central memory human T lymphocytes. Blood 107, 1828–1836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brentjens R.J., Davila M.L., Riviere I., et al. (2013). CD19-targeted T cells rapidly induce molecular remissions in adults with chemotherapy-refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Sci. Transl. Med. 5, 177ra38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brentjens R.J., Riviere I., Park J.H., et al. (2011). Safety and persistence of adoptively transferred autologous CD19-targeted T cells in patients with relapsed or chemotherapy refractory B-cell leukemias. Blood 118, 4817–4828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler M.O., Friedlander P., Milstein M.I., et al. (2011). Establishment of antitumor memory in humans using in vitro-educated CD8+ T cells. Sci. Transl. Med. 3, 80ra34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cieri N., Camisa B., Cocchiarella F., et al. (2013). IL-7 and IL-15 instruct the generation of human memory stem T cells from naive precursors. Blood 121, 573–584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davila M.L., Riviere I., Wang X., et al. (2014). Efficacy and toxicity management of 19-28z CAR T cell therapy in B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Sci. Transl. Med. 6, 224ra25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duarte R.F., Chen F.E., Lowdell M.W., et al. (2002). Functional impairment of human T-lymphocytes following PHA-induced expansion and retroviral transduction: implications for gene therapy. Gene Ther. 9, 1359–1368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gattinoni L., and Restifo N.P. (2013). Moving T memory stem cells to the clinic. Blood 121, 567–568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gattinoni L., Klebanoff C.A., Palmer D.C., et al. (2005). Acquisition of full effector function in vitro paradoxically impairs the in vivo antitumor efficacy of adoptively transferred CD8+ T cells. J. Clin. Invest. 115, 1616–1626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gattinoni L., Powell D.J., Jr., Rosenberg S.A., and Restifo N.P. (2006). Adoptive immunotherapy for cancer: building on success. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 6, 383–393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gattinoni L., Zhong X.S., Palmer D.C., et al. (2009). Wnt signaling arrests effector T cell differentiation and generates CD8+ memory stem cells. Nat. Med. 15, 808–813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gattinoni L., Lugli E., Ji Y., et al. (2011). A human memory T cell subset with stem cell-like properties. Nat. Med. 17, 1290–1297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilham D.E., Debets R., Pule M., et al. (2012). CAR-T cells and solid tumors: tuning T cells to challenge an inveterate foe. Trends Mol. Med. 18, 377–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grupp S.A., Kalos M., Barrett D., et al. (2013). Chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells for acute lymphoid leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 368, 1509–1518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinrichs C.S., Spolski R., Paulos C.M., et al. (2008). IL-2 and IL-21 confer opposing differentiation programs to CD8+ T cells for adoptive immunotherapy. Blood 111, 5326–5333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinrichs C.S., Borman Z.A., Cassard L., et al. (2009). Adoptively transferred effector cells derived from naive rather than central memory CD8+ T cells mediate superior antitumor immunity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 17469–17474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinrichs C.S., Borman Z.A., Gattinoni L., et al. (2011). Human effector CD8+ T cells derived from naive rather than memory subsets possess superior traits for adoptive immunotherapy. Blood 117, 808–814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollyman D., Stefanski J., Przybylowski M., et al. (2009). Manufacturing validation of biologically functional T cells targeted to CD19 antigen for autologous adoptive cell therapy. J. Immunother. 32, 169–180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J., Khong H.T., Dudley M.E., et al. (2005). Survival, persistence, and progressive differentiation of adoptively transferred tumor-reactive T cells associated with tumor regression. J. Immunother. 28, 258–267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huarte E., Fisher J., Turk M.J., et al. (2009). Ex vivo expansion of tumor specific lymphocytes with IL-15 and IL-21 for adoptive immunotherapy in melanoma. Cancer Lett. 285, 80–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson L.A., Morgan R.A., Dudley M.E., et al. (2009). Gene therapy with human and mouse T-cell receptors mediates cancer regression and targets normal tissues expressing cognate antigen. Blood 114, 535–546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalos M., Levine B.L., Porter D.L., et al. (2011). T cells with chimeric antigen receptors have potent antitumor effects and can establish memory in patients with advanced Leukemia. Sci Transl Med 3, 95ra73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko S., Mastaglio S., Bondanza A., et al. (2009). IL-7 and IL-15 allow the generation of suicide gene-modified alloreactive self-renewing central memory human T lymphocytes. Blood 113, 1006–1015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kershaw M.H., Westwood J.A., Parker L.L., et al. (2006). A phase I study on adoptive immunotherapy using gene-modified T cells for ovarian cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 12, 6106–6115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klebanoff C.A., Finkelstein S.E., Surman D.R., et al. (2004). IL-15 enhances the in vivo antitumor activity of tumor-reactive CD8+ T cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 1969–1974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klebanoff C.A., Gattinoni L., Torabi-Parizi P., et al. (2005). Central memory self/tumor-reactive CD8+ T cells confer superior antitumor immunity compared with effector memory T cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 9571–9576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochenderfer J.N., Dudley M.E., Feldman S.A., et al. (2012). B-cell depletion and remissions of malignancy along with cytokine-associated toxicity in a clinical trial of anti-CD19 chimeric-antigen-receptor-transduced T cells. Blood 119, 2709–2720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunert A., Straetemans T., Govers C., et al. (2013). TCR-engineered T cells meet new challenges to treat solid tumors: choice of antigen, T cell fitness, and sensitization of tumor milieu. Front Immunol 4, 363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamers C.H., Van De Griend R.J., Braakman E., et al. (1992). Optimization of culture conditions for activation and large-scale expansion of human T lymphocytes for bispecific antibody-directed cellular immunotherapy. Int. J. Cancer 51, 973–979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamers C.H., Willemsen R.A., Luider B.A., et al. (2002). Protocol for gene transduction and expansion of human T lymphocytes for clinical immunogene therapy of cancer. Cancer Gene Ther. 9, 613–623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamers C., Van Elzakker P., Langeveld S., et al. (2006a). Process validation and clinical evaluation of a protocol to generate gene-modified T lymphocytes for imunogene therapy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma: GMP-controlled transduction and expansion of patient's T lymphocytes using a carboxy anhydrase IX-specific scFv transgene. Cytotherapy 8, 542–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamers C.H., Sleijfer S., Vulto A.G., et al. (2006b). Treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma with autologous T-lymphocytes genetically retargeted against carbonic anhydrase IX: first clinical experience. J. Clin. Oncol. 24, e20–e22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamers C.H., Willemsen R.A., Van Elzakker P., et al. (2006c). Phoenix-ampho outperforms PG13 as retroviral packaging cells to transduce human T cells with tumor-specific receptors: implications for clinical immunogene therapy of cancer. Cancer Gene Ther. 13, 503–509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamers C.H., Willemsen R., Van Elzakker P., et al. (2011). Immune responses to transgene and retroviral vector in patients treated with ex vivo-engineered T cells. Blood 117, 72–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamers C.H., Sleijfer S., Van Steenbergen S., et al. (2013a). Treatment of Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma With CAIX CAR-engineered T cells: Clinical Evaluation and Management of On-target Toxicity. Mol. Ther. 21, 904–912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamers C.H., Van Elzakker P., Van Steenbergen S.C., et al. (2013b). Long-term stability of T-cell activation and transduction components critical to the processing of clinical batches of gene-engineered T cells. Cytotherapy 15, 620–626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D.W., Kochenderfer J.N., Stetler-Stevenson M., et al. (2014). T cells expressing CD19 chimeric antigen receptors for acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in children and young adults: a phase 1 dose-escalation trial. Lancet. Early Online Publication. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61403-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S., Riley J., Rosenberg S., and Parkhurst M. (2006). Comparison of common gamma-chain cytokines, interleukin-2, interleukin-7, and interleukin-15 for the in vitro generation of human tumor-reactive T lymphocytes for adoptive cell transfer therapy. J. Immunother. 29, 284–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lurquin C., Lethe B., De Plaen E., et al. (2005). Contrasting frequencies of antitumor and anti-vaccine T cells in metastases of a melanoma patient vaccinated with a MAGE tumor antigen. J. Exp. Med. 201, 249–257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markley J.C., and Sadelain M. (2010). IL-7 and IL-21 are superior to IL-2 and IL-15 in promoting human T cell-mediated rejection of systemic lymphoma in immunodeficient mice. Blood 115, 3508–3519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maude S.L., Frey N., Shaw P.A., et al. (2014). Chimeric antigen receptor T cells for sustained remissions in leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 371, 1507–1517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan R.A., Dudley M.E., Wunderlich J.R., et al. (2006). Cancer regression in patients after transfer of genetically engineered lymphocytes. Science 314, 126–129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pouw N., Treffers-Westerlaken E., Kraan J., et al. (2010a). Combination of IL-21 and IL-15 enhances tumour-specific cytotoxicity and cytokine production of TCR-transduced primary T cells. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 59, 921–931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pouw N., Treffers-Westerlaken E., Mondino A., et al. (2010b). TCR gene-engineered T cell: Limited T cell activation and combined use of IL-15 and IL-21 ensure minimal differentiation and maximal antigen-specificity. Mol. Immunol. 47, 1411–1420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins P.F., Dudley M.E., Wunderlich J., et al. (2004). Cutting edge: Persistence of transferred lymphocyte clonotypes correlates with cancer regression in patients receiving cell transfer therapy. J. Immunol. 173, 7125–7130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins P.F., Morgan R.A., Feldman S.A., et al. (2011). Tumor regression in patients with metastatic synovial cell sarcoma and melanoma using genetically engineered lymphocytes reactive with NY-ESO-1. J. Clin. Oncol. 29, 917–924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg S.A., Yang J.C., Sherry R.M., et al. (2011). Durable complete responses in heavily pretreated patients with metastatic melanoma using T cell transfer immunotherapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 17, 4550–4557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneiders F.L., De Bruin R.C., Van Den Eertwegh A.J., et al. (2012). Circulating invariant natural killer T-cell numbers predict outcome in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: updated analysis with 10-year follow-up. J. Clin. Oncol. 30, 567–570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straetemans T., Van Brakel M., Van Steenbergen S., et al. (2012). TCR gene transfer: MAGE-C2/HLA-A2 and MAGE-A3/HLA-DP4 epitopes as melanoma-specific immune targets. Clin. Dev. Immunol. 2012, 586314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Till B.G., Jensen M.C., Wang J., et al. (2008). Adoptive immunotherapy for indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma and mantle cell lymphoma using genetically modified autologous CD20-specific T cells. Blood 112, 2261–2271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uemura H., Okajima E., Debruyne F.M.J., and Oosterwijk E. (1994). Internal image antiidiotype antibodies related to renal-cell carcinoma-associated antigen G250. Int. J. Cancer 56, 609–614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Berger C., Wong C.W., et al. (2011). Engraftment of human central memory-derived effector CD8+ T cells in immunodeficient mice. Blood 117, 1888–1898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S., Ji Y., Gattinoni L., et al. (2013). Modulating the differentiation status of ex vivo-cultured anti-tumor T cells using cytokine cocktails. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 62, 727–736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.