Abstract

Background: The majority of young people in need of palliative care live in low- and middle-income countries, where curative treatment is less available.

Objective: We systematically reviewed published data describing palliative care services available to young people with life-limiting conditions in low- and middle-income countries and assessed core elements with respect to availability, gaps, and under-reported aspects.

Methods: PubMed, CINAHL, EMBASE (1980–2013), and secondary bibliographies were searched for publications that included patients younger than 25 years with life-limiting conditions and described palliative care programs in low- and middle-income countries. A data extraction checklist considered 15 items across seven domains: access, education/capacity building, health system support, pain management, symptom management, end-of-life care, and bereavement. Data were aggregated by program and country.

Results: Of 1572 records, 238 met criteria for full-text review; 34 qualified for inclusion, representing 30 programs in 21 countries. The median checklist score was 7 (range, 1–14) of 10 reported (range, 3–14). The most pervasive gaps were in national health system support (unavailable in 7 of 17 countries with programs reporting), specialized education (unavailable in 7 of 19 countries with programs reporting), and comprehensive opioid access (unavailable in 14 of 21 countries with programs reporting). Underreported elements included specified practices for pain management and end-of-life support.

Conclusion: Comprehensive pediatric palliative care provision is possible even in markedly impoverished settings. Improved national health system support, specialized training and opioid access are key targets for research and advocacy. Application of a checklist methodology can promote awareness of gaps to guide program evaluation, reporting, and strengthening.

Introduction

Palliative care for children and young adults, defined as the “active, total care” of a young person's body, mind, spirit, and family, from life-limiting diagnosis until death, is an internationally recognized priority.1,2 It is estimated that annually 7 million families could benefit from pediatric palliative care, but those in low- and middle-income countries seldom have such access.2,3 We assess the published data on services and gaps in pediatric palliative care in low- and middle-income countries, home to nearly 90% of the world's young people.4

Children, adolescents, and young adults in low- and middle-income countries are disproportionately impacted by life-limiting conditions (LLC), including infectious diseases, cancer, congenital defects, and malnutrition.4–8 Approximately 400,000 children are diagnosed with HIV each year; 3.4 million children are living with HIV/AIDS.5 More than 90% live in low- and middle-income countries, where 75% lack access to antiretroviral therapy and have shortened life expectancies.5 Approximately 160,000 children younger than 15 years in low- and middle-income countries develop cancer each year.7,8 They are often diagnosed later in low- and middle-income countries, when the disease is more advanced and difficult to cure even if treatment is available. Only an estimated 20% of children in low- and middle-income countries will be cured, compared with 80% of children in high-income countries, so the need for palliative care is acute.7–11 Complex conditions such as congenital heart defects, neural tube defects, hemoglobinopathies, constitutional chromosomal anomalies, and sequelae of prenatal infections and malnutrition in low- and middle-income countries also often lead to chronic symptoms for which palliative care is critical.12,13 The first global atlas of palliative care estimates that each year, nearly 1.2 million children below age 15 are in need of palliative care at the end of life, with 98% of these children in low- and middle-income countries.14 For many young people with LLC, attainment of cure or normal life expectancy is elusive. However, hope for comfort, meaning, and the highest quality of life and death possible—the goals of palliative care—is within reach. The principles of palliative care can be applied successfully and cost effectively, even in resource-limited settings.11,15–18

What is known

In a systematic review, Knapp and colleagues19 adapted a four-part system devised by the Observatory on End of Life Care20 (OELC), an internationally recognized center for palliative care research, to categorize provision around the world. Two-thirds of countries reportedly offered no pediatric palliative services; 19% were classified at Level 2 (capacity building) and 10% at Level 3 (localized provision). Even countries achieving mainstream provision (Level 4), such as South Africa and many high-income countries, vary regionally in service quality and accessibility,11 but detailed examinations comparing provision across settings, particularly in low- and middle-income countries, have not been published. Other researchers have mapped services using targeted surveys and described services based on responses grouped across multiple countries globally.21 To complement these methods, which are vital to support advocacy efforts, analysis of published program descriptions, as recently detailed for sub-Saharan Africa,22 lend a unique perspective on reporting and evidence gaps.

What this review contributes

In this first review focusing on low- and middle-income countries globally, we evaluate the published data on pediatric palliative care services, assess the availability of core elements of pediatric palliative care reported by these publications, and examine the regional context in which these services are reported. We identify gaps in provision and reporting that will be useful for providers, researchers, and advocates for pediatric palliative care. Finally, we demonstrate the effective use of a checklist that could be adapted as a standardized programmatic or regional “scorecard” to facilitate reporting and guide program development.

Methods

Search strategy

PubMed, CINAHL, and EMBASE databases were searched from January 1, 1980 through January 23, 2013, as were the authors' personal databases and secondary bibliographies including hand searches of references from included articles. Search strategies are presented in Table 1 and Appendix A. Publications were eligible for inclusion if three criteria were met: (1) the setting was a low-, lower-middle-, or upper-middle–income country per World Bank definitions23; (2) the population served included people younger than 25 years24 and diagnosed with conventionally defined LLC25; and (3) the primary objective was to describe existing palliative care program(s).

Table 1.

Search strategy for PubMed. Similar strategies were used for each database (See Appendix A)

| 1. (child OR children OR adolescent OR adolescence OR infant OR baby OR youth OR “young adult”) |

| AND |

| 2. (palliation OR palliative care[MeSH Terms] OR terminal care[MeSH Terms] OR bereavement[MeSH Terms] OR advance care planning[MeSH Terms] OR hospice care[MeSH Terms] OR hospices[MeSH Terms] OR end of life care[MeSH Terms] OR grief[MeSH Terms]) |

| AND |

| 3. (developing countries[MeSH Terms] OR low income population[MeSH Terms] OR Africa or “Southeast Asia” or “South Asia” or Caribbean or “Latin America” or “South America” or “Central America” or Afghanistan or Bangladesh or Benin or “Burkina Faso” or Burundi or Cambodia or “Central African Republic” or Chad or Comoros or Congo or Eritrea or Ethiopia or Gambia or Guinea or Guinea-Bissau or Haiti or Kenya or Korea or Kyrgyzstan or Liberia or Madagascar or Malawi or Mali or Mozambique or Myanmar or Nepal or Niger or Rwanda or Sierra Leone or Somalia or Tajikistan or Tanzania or Togo or Uganda or Zimbabwe or Angola or Armenia or Belize or Bhutan or Bolivia or Cameroon or “Cape Verde” or Congo or Cote d'Ivoire or “Ivory Coast” or Djibouti or Egypt or “El Salvador” or Fiji or Georgia or Ghana or Guatemala or Guyana or Honduras or Indonesia or India or Iraq or Kiribati or Kosovo or Laos or Lesotho or “Marshall Islands” or Mauritania or Micronesia or Moldova or Mongolia or Morocco or Nicaragua or Nigeria or Pakistan or “Papua New Guinea” or Paraguay or Samoa or “Sao Tome” or Senegal or Solomon Islands or “Sri Lanka” or Sudan or Swaziland or Syria or Timor-Leste or Tonga or Turkmenistan or Tuvalu or Ukraine or Uzbekistan or Vanuatu or Vietnam or Palestine or Yemen or “West Bank” or Gaza or Zambia or Albania or Algeria or “American Samoa” or Antigua or Barbados or Argentina or Azerbaijan or Belarus or Bosnia or Botswana or Brazil or Bulgaria or Chile or China or Colombia or “Costa Rica” or Cuba or Dominica or “Dominican Republic” or Ecuador or Gabon or Grenada or Iran or Jamaica or Jordan or Kazakhstan or Latvia or Lebanon or Libya or Lithuania or Macedonia or Maldives or Mauritius or Mayotte or Mexico or Montenegro or Namibia or Palau or Panama or Peru or Romania or Russia or Serbia or Seychelles or “South Africa” or “St Kitts” or Nevis or “St Lucia” or “St Vincent” or Grenadines or Suriname or Thailand or Tunisia or Turkey or Uruguay or Venezuela) |

Publications describing services for adults without specification of services for young people were excluded. This was important, given that programs in low- and middle-income countries may be based on a mixed care models, in which systems for adults may accommodate a small, but variable, number of children. Case reports were excluded; there were no restrictions for study type or language. After duplicate elimination, all titles and abstracts were screened. Results are reported in accordance with the PRISMA statement.26

Data extraction and analysis

Because no existing tools were suitable for our objectives, we developed a 15-item, 7-domain checklist (Appendix B) to assess provision of core elements of pediatric palliative care in published reports. The 7 domains are divided into 2 groups: delivery (access, education and capacity building; health system support) and service (pain and symptom management; end-of-life and bereavement support). A literature review of palliative care quality measures and practices in diverse settings, adapted for low- and middle-income countries and including data used by the OELC to determine provision levels, informed the checklist (Appendix C).10,11,19,20,27–33 The checklist was piloted on 50 publications assessed at the full-text level, with refinement of domains and scoring; all included publications were rescored with the final checklist. Coauthors independently reviewed the checklist for face and content validity. Pertinent evaluation criteria aiming to assess study quality, risk of bias, and strength of evidence were integrated into the checklist and narrative syntheses; these included elements such as population studied, funding, and consistency of findings between multiple studies from a single program or country.34,35

Each publication was scored twice and received a total checklist score (numerator) and a total available data score (denominator). Discrepancies were resolved by discussion and consensus. The total checklist score represented the items reported to be available. The total available data score represented the number of items discussed, including items reported as unavailable, up to a maximum of 15 (6 delivery domains and 9 service domains). Publications were neither required nor expected to address all items, however, 25 publications that were insufficiently detailed to score at least 1 item as present or absent were excluded. Items not discussed were noted as absent, such that the denominator could be less than 15. Scores were compiled by country and, when possible, by program, using the highest score per item. Median scores were calculated for all countries combined, and also separately for low-income and lower-middle–income countries and upper-middle–income countries).

Results

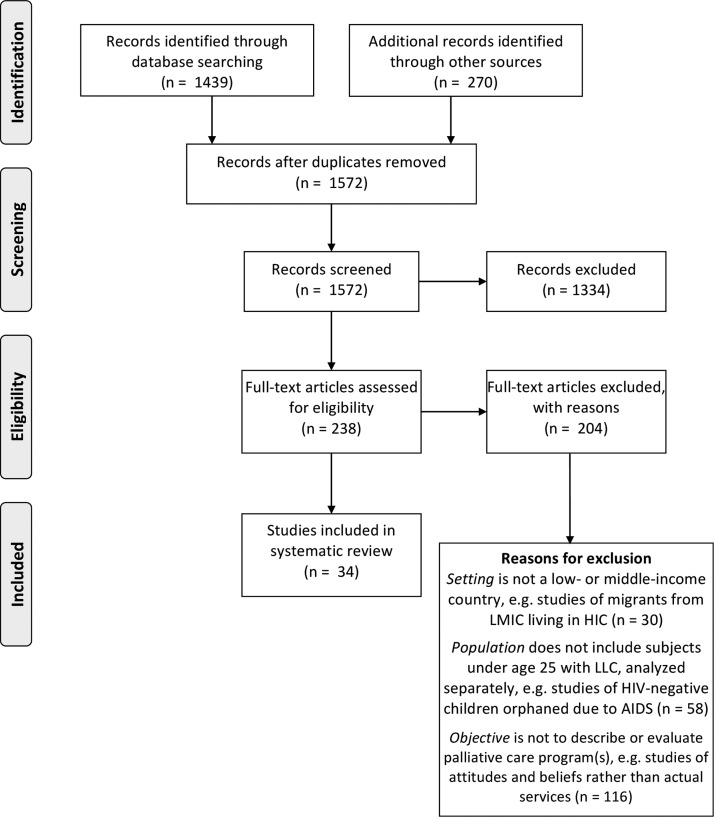

The search identified 1572 studies; 238 were eligible after initial screening (Fig. 1). Full text was reviewed for 236 articles (2 out-of-print articles could not be obtained) and 34 were included (Appendix D). Seventy-six studies published in 7 languages other than English were assessed at the title-abstract level and 8 studies in Spanish, Portuguese, and Chinese were assessed at the full-text level. All studies meeting inclusion criteria were in English. Included studies were published between 2002 and 2012, and represented services from 21 countries, 28 cities, and 30 distinct programs (Table 2).

FIG. 1.

PRISMA flow chart showing study selection process.26 LIC, low-income country; LMIC, lower-middle–income country; NA, not available; PPP, purchasing power parity; UMIC, upper-middle–income country; USD, U.S. dollar.

Table 2.

Distribution of Sources of Data by Country, City, Program and Study versus World Bank Income Group and Region23

| Countries | Citiesa | Programsa | Studiesb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 21 | 28 | 30 | 34 |

| Low-income | 2 | 2 | 4 | 5 |

| Lower-middle–income | 9 | 12 | 12 | 17 |

| Upper-middle–income | 10 | 14 | 14 | 29 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 3 | 5 | 7 | 8 |

| South Asia | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| Europe and Central Asia | 8 | 9 | 9 | 12 |

| Latin America and the Caribbean | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| Middle East and North Africa | 7 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

Minimums; some articles stated only that multiple cities and/or sites were involved.

Publication totals do not equal 34 as some referenced multiple countries.

The median number of studies per country was 2 (range, 1–5). Thirty-one publications (representing 20 of 21 countries) included national or regional level descriptions as part of their objectives, featuring a single site or region in publications from 16 of these countries, while 4 countries described multiple programs and reported service availability at a national level. Only the 3 publications from South Africa reported an exclusively local scope, with each describing services at a single site.

Patients served by the palliative care programs included those with multiple LLC (15/34; 44%), with cancer only (16/34; 47%) or with HIV only (3/34; 9%). Only 12 of 236 full-text publications reviewed reported efforts to target adolescents and young adults; none focused exclusively on this population.

Core elements

The median total checklist score for all countries was 7 (range, 1–14) of 10 (median total available data score; range, 3–14). For upper-middle–income countries, the median score was 11 of 12 (range, 1–14/3–14); for low-income countries/lower-middle–income countries, the median score was 4.5 of 8 (range, 1–11/5–11). Table 3 lists key national health and economic indicators for each represented country.

Table 3.

National Health and Economic Status Indicators for Twenty-One Countries with Palliative Care Programs Represented in the Systematic Review23,36,37

| Income group, 201223 | Country | Total population, 201223 | GNI in PPP terms, 201123 | Multidimensional poverty index, 201136 | Government health care expenditure per capita in USD, 201023 | Opioid consumption37 | Under-5 mortality per 1000 live births, 201123 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LIC | Malawi | 15,906,483 | 753 | 0.381 | 15 | 0.8069 | 83 |

| Uganda | 36,345,860 | 1124 | 0.367 | 10 | 0.1476 | 90 | |

| LMIC | Pakistan | 179,160,111 | 2550 | 0.264 | 8 | 0.0939 | 72 |

| Palestine | 4,046,901 | 2656 | 0.005 | NA | NA | 22 | |

| Moldova | 3,559,541 | 3058 | 0.007 | 87 | 4.357 | 16 | |

| Iraq | 32,578,209 | 3177 | 0.059 | 162 | 0.1783 | 38 | |

| Morocco | 32,521,143 | 4196 | 0.048 | 58 | 0.7613 | 33 | |

| Egypt | 80,721,874 | 5269 | 0.024 | 43 | 0.8764 | 21 | |

| Jordan | 6,318,000 | 5300 | 0.008 | 253 | 3.9269 | 21 | |

| Ukraine | 45,593,300 | 6175 | 0.008 | 132 | 10.7508 | 10 | |

| Albania | 3,162,083 | 7803 | 0.005 | 94 | 2.7319 | 14 | |

| UMIC | South Africa | 51,189,307 | 9469 | 0.057 | 286 | 12.4702 | 47 |

| Iran | 76,424,443 | 10164 | NA | 115 | 101.2274 | 25 | |

| Costa Rica | 4,805,295 | 10497 | NA | 454 | 8.7354 | 10 | |

| Romania | 21,326,905 | 11046 | NA | 341 | 10.4317 | 13 | |

| Bulgaria | 7,304,632 | 11412 | NA | 252 | 55.6853 | 12 | |

| Turkey | 73,997,128 | 12246 | 0.028 | 510 | 12.7448 | 15 | |

| Lebanon | 4,424,888 | 13076 | NA | 242 | 4.3421 | 9 | |

| Belarus | 9,464,000 | 13439 | 0 | 249 | 7.3693 | 6 | |

| Latvia | 2,025,473 | 14293 | 0.006 | 439 | 21.5603 | 8 | |

| Argentina | 41,086,927 | 14527 | 0.011 | 405 | 10.0192 | 14 |

GNI, gross national income; LIC, low-income country; LMIC, lower-middle–income country; NA, not available; PPP, purchasing power parity; UMIC, upper-middle-income country; USD, US dollar.

The elements most widely reported to be available were access and non-pain symptom management. Programs in 19 countries reported items of access: 12 of 14 (86%) reporting countries had interdisciplinary teams, 17 of 19 (89%) had hospital- or hospice-based inpatient services, and 14 of 19 (79%) had some support for home-based care (such as 24-hour telephone support or nursing visits). All programs were primarily based in urban areas, although 2 countries (Costa Rica and Belarus) reported nationwide home-based services. Programs in 12 countries reported management of symptoms other than pain, with those in 11 countries reporting efforts to address both physical and psychosocial concerns. No program specified an absence of non-pain symptom management, although programs in 9 countries did not publish data regarding such a service.

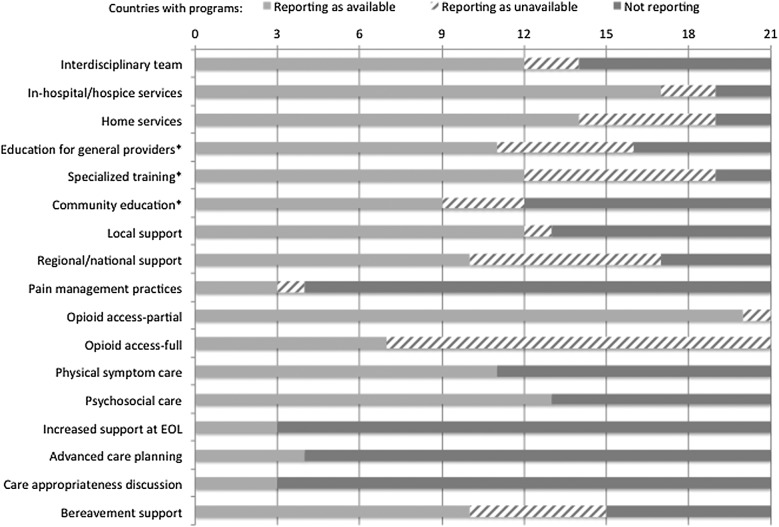

The most frequently reported gaps included specialized training in palliative care, policies supporting high-quality palliative care at regional or national levels, bereavement support, and pain management (Figs. 2, 3A, and 3B). Twelve of 19 (63%) countries with programs reporting had access to specialized training; 10 of 17 (59%) described regional or national support; 10 of 15 (67%) reported bereavement services. Although almost all (20/21) reported some degree of opioid access, only 7 reported full access to essential analgesic medications.38

FIG. 2.

Availability of core elements of pediatric palliative services, by country, in order of ascending gross national income (GNI) per capita in U.S. dollars. [1] Multiple distinct programs in the same city. [2] Previously reported to have no palliative care activity. [3] Multiple programs in different cities; data presented at a national level and not program-specific. [4] Program(s) not specified; data also presented at a national level. [5] Program based in the capital but services reported to be available throughout the entire country. [6] Multiple service sites in different cities.

FIG. 3A.

Reported availability of pediatric palliative care services by checklist item from 30 distinct programs in 21 low- and middle-income countries. Domains were reported as available if any checklist item was reported to be available.

FIG. 3B.

Reported availability of pediatric palliative care services by checklist item from 30 distinct programs in 21 low- and middle-income countries. *The education domain was valued at 1 point if any or all 3 items were reported to be available (see Appendix B for details of scoring).

All countries had programs that reported items of both delivery and service. Most individual studies (94%) reported items from both. All domains were reported for a majority of publications and countries, with exceptions in end-of-life support as a domain (not specifically discussed in publications from programs in 16 [76%] countries), and standardized pain management practices as a single item (not specified in publications from 17 [81%] countries).

Consideration of bias

Variation between publications from the same countries was common; however, most instances involved items reported in some articles and not others. In select cases, these correlated with time elapsed between publications; studies from Lebanon and Jordan (2008–2012) described the initiation of programs (in 2002 and 2003, respectively) and gradual expansion, with increasing home-based services and attempts to extend services outside capital cities (Appendix D).

Twelve studies noted external funding sources, while the remainder provided no funding information. None reported relevant conflicts of interest. Funded and unfunded studies did not appear to differ in study population or nature of reported data. Only five studies had a first author from high-income countries, and all publications from low-income countries had first and senior authors with local affiliations. As only two programs precisely defined catchment areas, and data on incidence and prevalence of LLC was inconsistently available, it was not possible to assess scores relative to total populations. The publications' descriptive nature precluded the application of conventional risk of bias and quality assessment tools.

Discussion

In this review of pediatric palliative care in low- and middle-income countries, we identified opportunities for improvement at the level of national policies to support palliative care, provider training, pain management practices, end-of-life and bereavement support, and reporting of outcomes for the core elements of comprehensive palliative care. Previous studies assessing palliative services globally that included children did not report provision of specific elements described in the published literature, or focused on broad categorization at the regional or income group level.19,21,39 Many of the needs discussed here have been recognized but not previously characterized in detail nor systematically assessed across programs and regions. Two countries represented by publications in our review (Jordan and Turkey) were previously reported to have capacity-building activity only (no actual services) and two (Lebanon and Pakistan) were reported to have no activity; three of these documented availability of services at or above the median across all countries included in the review (Fig. 2).19

Availability

Our review highlights the reported availability of pediatric palliative care in low- and middle-income countries settings characterized by diverse socioeconomic and health indicators. Several programs described impressive provision of care despite profound challenges. This appears in part due to the impact of the AIDS epidemic, as in Africa, where some of the poorest countries in our review have developed striking programs in response to the burden wrought by HIV.40–43 Several features of palliative care programs, including interdisciplinary teams, symptom management, and institutional support, may require a shift in how health care is conceived and provided. Our findings suggest that even in resource-limited communities, which may lack advanced technology and infrastructure necessary to cure many LLC, comprehensive palliative care can be achieved even in the absence of broader systemic support.

Our review documents core elements in need of ongoing advocacy efforts at a broader policy level, with the most widely reported gaps concerning specialized provider training, national health system support, and consistent opioid access. Studies from Uganda and Malawi (Appendix D) illustrate how comprehensive provision is possible, and demonstrate how some commonly reported gaps can be addressed. Publications from Uganda described three pediatric programs in Kampala that offer hospital-, hospice-, and home-based care, as well as provider education, formal efforts to improve opioid access, and support for families' basic needs. Studies from Malawi reported services in Blantyre, where an interdisciplinary team has been providing care, including palliative chemotherapy and psychosocial/spiritual support, for over a decade. These cases demonstrate that improving palliative care provision is not contingent on macro-economic gains that may be required for other public health gains; during the past decade, Uganda and Malawi saw negligible changes in gross national income per capita, which remained at less than 1% that of leading high-income countries.23,44,45

Underreporting

Our study highlights areas that warrant ongoing monitoring and reporting. Although we reviewed full-text publications from East Asia and the Pacific, including discussions of pain management and life-support limitation, none specifically described programs providing palliative care to children or adolescents and young adults. This does not suggest that the region is without pediatric palliative care, instead, it may indicate variability in models of care delivery influencing data reporting. In many locations, pediatric palliative care is not recognized as a distinct field, although various providers may offer related services. Pediatric services may exist under the umbrella of adult care and not be specifically captured in program publications that prioritize the larger adult population. This highlights an opportunity to promote pediatric-specific reporting in these regions.

End-of-life support—the most recognized palliative care domain, which we broadly defined to include any adaptation in level of care at the end of life—was underreported. Decisions to define and limit life-sustaining measures are particularly important in settings in which resources to provide aggressive biomedical or complementary therapy are scarce. We note that some articles reviewed reported exclusively on end-of-life care outside the context of a clearly described palliative program and thus did not meet inclusion criteria. Such reporting gaps may represent opportunities for improvement as well as reflect authors' priorities and local conceptualization of palliative care; future efforts should assess how sociocultural factors impact resource allocation and reporting. Our use of a checklist with a numerator and denominator calls attention to these gaps and could benefit programs seeking to assess their provision and reporting.

As programs tend to be concentrated in urban centers, particularly capital cities, countries with publications describing multiple programs still may not reach children in rural areas, and best practice models may not reflect care elsewhere in the region.46 Legislation allowing nurses and palliative care workers to prescribe morphine can facilitate pain relief for children in remote areas, but such laws have not been widely implemented.11 Even in countries with programs that provide services to a wide geographic area (i.e., Costa Rica and Belarus), service availability does not equate with care uptake by every child in need. While our assessment of health system support highlights the challenges affecting service feasibility in a given area, identifying gaps between need for services, referral, availability and uptake is an area for further investigation.

Both pain and non-pain symptom management are priorities of the World Health Organization and warrant further study1,38,47 and our efforts complement population analyses of opioid access that recognize multidimensional barriers that merit attention globally.48 Given how nonpharmacologic symptom management can be achieved with limited resources, we encourage consistent description of practices across low- and middle-income countries settings. Explicit reporting of funding sources for palliative services on programmatic and regional levels would help to further understand these dynamics.

Limitations

We are aware that some countries have programs that have not been published; we recognize the difficulties of publication in the face of scarce resources, such that publications reflect in part sites above a threshold of financial and academic support. Our methods did allow a comprehensive appraisal of existing publications across low- and middle-income countries, utilizing multidisciplinary databases with international and multilingual coverage, and a standard data extraction checklist developed on sources across diverse settings. Of programs that have published their experiences, only some clearly report what services are not offered. Although consistent with the recognized publication bias toward positive findings, it limited thorough depiction of provision gaps. Finally, our study was not designed to evaluate the quality of services provided, nor was this information readily available. As with related systematic reviews, we were unable to systematically critique included publications in terms of quality and bias, due to the descriptive nature of most reports.19,22

Applicability

Awareness of gaps both in reporting and availability can strengthen advocacy for pediatric palliative care in low- and middle-income countries and promote public health strategies to reach more patients in previously underserved regions. In this review, we demonstrated the ongoing need for advocacy in pediatric palliative care policies, education, and resources, including those relevant for opioid access, and underreporting of pediatric-specific practices. A checklist-based methodology, as demonstrated, has potential applications to prospective program evaluation and self-auditing.

Conclusions

Although provision of pediatric palliative care can be challenging in low- and middle-income countries, it is crucial precisely because resources are limited and curative therapy is less available. Comprehensive pediatric palliative care can be successfully provided in low- and middle-income countries despite unfavorable economic conditions and limited infrastructure. With recent global attention spotlighting needs in pediatric palliative care,2,14 our systematic review presents timely complementary evidence of the current status in the literature and gaps to be addressed. The development of standardized programmatic and regional scorecards incorporating qualitative and quantitative measures, similar to our checklist, could facilitate reporting and program development.

Appendix A.

Search Strategies for Other Databases

| CINAHL |

|---|

| 1. (MW palliation OR ‘palliative care’ OR ‘terminal care’ OR bereavement OR ‘advance care planning’ OR ‘hospice care’ OR hospices OR ‘end of life care’) |

| AND |

| 2. (TX child OR children OR adolescent OR adolescence OR infant OR baby OR youth OR ‘young adult’) |

| AND |

| 3. (TX africa OR ‘southeast asia’ OR ‘south asia’ OR caribbean OR ‘latin america’ OR ‘south america’ OR ‘central america’ OR afghanistan OR bangladesh OR benin OR ‘burkina faso’ OR burundi OR cambodia OR ‘central african republic’ OR chad OR comoros OR eritrea OR ethiopia OR gambia OR guinea OR ‘guinea bissau’ OR haiti OR kenya OR korea OR kyrgyzstan OR liberia OR madagascar OR malawi OR mali OR mozambique OR myanmar OR nepal OR niger OR rwanda OR ‘sierra leone’ OR somalia OR tajikistan OR tanzania OR togo OR uganda OR zimbabwe OR angola OR armenia OR belize OR bhutan OR bolivia OR cameroon OR ‘cape verde’ OR congo OR ‘ivory coast’ OR djibouti OR egypt OR ‘el salvador’ OR fiji OR georgia OR ghana OR guatemala OR guyana OR honduras OR indonesia OR india OR iraq OR kiribati OR kosovo OR laos OR lesotho OR ‘marshall islands’ OR mauritania OR micronesia OR moldova OR mongolia OR morocco OR nicaragua OR nigeria OR pakistan OR papua AND new AND guinea OR paraguay OR samoa OR ‘sao tome’ OR senegal OR ‘solomon islands’ OR sri AND lanka OR sudan OR swaziland OR syria OR ‘timor leste’ OR tonga OR turkmenistan OR tuvalu OR ukraine OR uzbekistan OR vanuatu OR vietnam OR palestine OR yemen OR ‘west bank’ OR gaza OR zambia OR albania OR algeria OR ‘american samoa’ OR antigua OR barbados OR argentina OR azerbaijan OR belarus OR bosnia OR botswana OR brazil OR bulgaria OR chile OR china OR colombia OR ‘costa rica’ OR cuba OR dominica OR ‘dominican republic’ OR ecuador OR gabon OR grenada OR iran OR jamaica OR jordan OR kazakhstan OR latvia OR lebanon OR libya OR lithuania OR macedonia OR maldives OR mauritius OR mayotte OR mexico OR montenegro OR namibia OR palau OR panama OR peru OR romania OR russia OR serbia OR seychelles OR south AND africa OR ‘st kitts’ OR nevis OR ‘st lucia’ OR ‘st vincent’ OR grenadines OR suriname OR thailand OR tunisia OR turkey OR uruguay OR venezuela) |

| EMBASE |

|---|

| 1. (‘palliation’/exp/mj OR ‘palliative care’/exp/mj OR ‘end of life care’/exp/mj OR ‘terminal care’/exp/mj OR ‘bereavement’/exp/mj OR ‘advance care planning’/exp/mj OR ‘hospice care’/exp/mj OR ‘hospices’/exp/mj AND [embase]/lim) |

| AND |

| 2. (‘child’/de OR ‘children’/de OR ‘adolescent’/de OR ‘adolescence’/de OR ‘infant’/de OR ‘baby’/de OR ‘youth’/de AND [embase]/lim) |

| AND |

| 3. (africa OR ‘southeast asia’ OR ‘south asia’ OR caribbean OR ‘latin america’ OR ‘south america’ OR ‘central america’ OR afghanistan OR bangladesh OR benin OR ‘burkina faso’ OR burundi OR cambodia OR ‘central african republic’ OR chad OR comoros OR eritrea OR ethiopia OR gambia OR guinea OR ‘guinea bissau’ OR haiti OR kenya OR korea OR kyrgyzstan OR liberia OR madagascar OR malawi OR mali OR mozambique OR myanmar OR nepal OR niger OR rwanda OR ‘sierra leone’ OR somalia OR tajikistan OR tanzania OR togo OR uganda OR zimbabwe OR angola OR armenia OR belize OR bhutan OR bolivia OR cameroon OR ‘cape verde’ OR congo OR ‘ivory coast’ OR djibouti OR egypt OR ‘el salvador’ OR fiji OR georgia OR ghana OR guatemala OR guyana OR honduras OR indonesia OR india OR iraq OR kiribati OR kosovo OR laos OR lesotho OR ‘marshall islands’ OR mauritania OR micronesia OR moldova OR mongolia OR morocco OR nicaragua OR nigeria OR pakistan OR papua AND new AND guinea OR paraguay OR samoa OR ‘sao tome’ OR senegal OR ‘solomon islands’ OR sri AND lanka OR sudan OR swaziland OR syria OR ‘timor leste’ OR tonga OR turkmenistan OR tuvalu OR ukraine OR uzbekistan OR vanuatu OR vietnam OR palestine OR yemen OR ‘west bank’ OR gaza OR zambia OR albania OR algeria OR ‘american samoa’ OR antigua OR barbados OR argentina OR azerbaijan OR belarus OR bosnia OR botswana OR brazil OR bulgaria OR chile OR china OR colombia OR ‘costa rica’ OR cuba OR dominica OR ‘dominican republic’ OR ecuador OR gabon OR grenada OR iran OR jamaica OR jordan OR kazakhstan OR latvia OR lebanon OR libya OR lithuania OR macedonia OR maldives OR mauritius OR mayotte OR mexico OR montenegro OR namibia OR palau OR panama OR peru OR romania OR russia OR serbia OR seychelles OR south AND africa OR ‘st kitts’ OR nevis OR ‘st lucia’ OR ‘st vincent’ OR grenadines OR suriname OR thailand OR tunisia OR turkey OR uruguay OR venezuela AND [embase]/lim) |

Appendix B.

Standardized Data Extraction Checklist

| Delivery domains (subtotal 6) |

|---|

| Access (subtotal 3) |

| Interdisciplinary providers (1) |

| Designated in-hospital or in-hospice services (1) |

| Support for home setting (e.g., home visits, phone support, supplies) (1) |

| Education and capacity building (subtotal 1 for any/all of the 3 elements) |

| Continuing education for general health providers |

| Specific training/certification for those seeking specialization in palliative services |

| Supportive education for community members and families |

| Health system support (subtotal 2) |

| Policies/Infrastructure to support high quality and ethicallya sound palliative care in immediate health system (on institutional/center level) (1) |

| Policies/Infrastructure to support high quality and ethicallya sound palliative care in broader health system (on community/regional/national level, as reflected in government health policies or well-established, sustained nongovernmental infrastructural support, etc.) (1) |

Locally derived definition of “ethically sound” practices as primary basis (i.e., per publications/depictions from local context)

| Service domains (subtotal 9) |

|---|

| Pain Management (subtotal 3) |

| Standardized appropriate assessment tools or management practices available/used (1) |

| Consistent opioid and adjunctive meds access (0 none, 1 partial, 2 consistent) |

| General symptom management (subtotal 2) |

| Assessment and management of physical concerns other than pain (1) |

| Assessment and management of psychosocial and spiritual concerns, ideally with appropriate ethical/cultural contextual considerations (1) |

| End-of-life support (subtotal 3) |

| Increased palliative service support (of any form) at end of life (include decision-making support, addressing physical, psychosocial, or spiritual needs) (1) |

| Advanced care planning (1) |

| Consideration of care appropriateness and ethics (e.g., discussions among team and/or with family regarding options to limit care, considerations of quality of life, family's values and beliefs, etc.) (1) |

| Bereavement services (subtotal 1) |

| Any element of bereavement support for families (including anticipatory complicated grief management) and/or for providers (1) |

Appendix C. References Utilized in the Development and Application of the Data Extraction Checklist

1. National Quality Forum: A national framework and preferred practices for palliative and hospice care quality: A consensus report. 2006. www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2006/12/A_National_Framework_and_Preferred_Practices_for_Palliative_and_Hospice_Care_Quality.aspx (Last accessed September 27, 2012).

2. Amery J: Mapping children's palliative care around the world: An online survey of children's palliative care services and professionals' educational needs. J Palliat Med 2012;15:646–652.

3. Amery JM, Rose CJ, Holmes J, et al: The beginnings of children's palliative care in Africa: Evaluation of a children's palliative care service in Africa. J Palliat Med 2009;12:1015–1021.

4. Carroll JM, Santucci G, Kang TI, Feudtner C: Partners in pediatric palliative care: A program to enhance collaboration between hospital and community palliative care services. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2007;24:191–195.

5. Collins K, Harding R: Improving HIV management in sub-Saharan Africa: How much palliative care is needed? AIDS Care 2007;19:1304–1306.

6. Coombes R: Palliative care toolkit is developed for staff in countries ‘swamped by volume of suffering.’ Br J Haematol 2008;336:913.

7. Crane K: Palliative care gains ground in developing countries. J Natl Cancer Inst 2010;102:1613–1615.

8. Ddungu H: Palliative care: What approaches are suitable in developing countries. Br J Haematol 2011;154:728–735.

9. Delgado E, Barfield RC, Baker JN, et al: Availability of palliative care services for children with cancer in economically diverse regions of the world. Eur J Cancer 2010;46:2260–2266.

10. Duncan J, Spengler E, Wolfe J: Providing pediatric palliative care: PACT in action. Am J Maternal/Child Nurs 2007;32:279–287.

11. Economist Intelligence Unit: The quality of death: Ranking end-of-life care across the world. 2010. http://graphics.eiu.com/upload/QOD_main_final_edition_Jul12_toprint.pdf (Last accessed February 6, 2013).

12. Edlynn ES, Derrington S, Morgan H, et al: Developing a pediatric palliative care service in a large urban hospital: Challenges, lessons, and successes. J Palliat Med 2013;16:342–348.

13. Ferrell B, Paice J, Koczywas M: New standards and implications for improving the quality of supportive oncology practice. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:3824–3831.

14. Feudtner C, Kang TI, Hexem KR, et al: Pediatric palliative care patients: A prospective multicenter cohort study. Pediatrics 2011;127:1094–1101.

15. Gomes B, Harding R, Foley KM, Higginson IJ: Optimal approaches to the health economics of palliative care: Report of an international think tank. J Pain Symptom Manage 2009;38:4–10.

16. Harding R, Higginson IJ: Palliative care in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet 2005;365:1971–1977.

17. Himelstein BP, Hilden JM, Boldt AM, Weissman D: Pediatric palliative care. N Engl J Med 2004;350:1752–1762.

18. Human Rights Watch: Global state of pain treatment: Access to palliative care as a human right. 2011. www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/reports/hhr0511W.pdf (Last accessed June 19, 2013).

19. International Association for Hospice and Palliative Care (IAHPC): List of essential practices in palliative care. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother 2012;26:118–122.

20. International Observatory on End of Life Care. Lancaster University. 2008–2012. www.lancs.ac.uk/shm/research/ioelc/ (Last accessed October 25, 2012).

21. Johnston DL, Nagel K, Friedman DL, et al: Availability and use of palliative care and end-of-life services for pediatric oncology patients. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:4646–4650.

22. Kassam A, Skiadaresis J, Habib S, et al: Moving toward quality palliative cancer care: parent and clinician perspectives on gaps between what matters and what is accessible. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:910–915.

23. Knapp C, Woodworth L, Wright M, et al: Pediatric palliative care provision around the world: A systematic review. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2011;57:361–368.

24. Lamas D, Rosenbaum L: Painful inequities—Palliative care in developing countries. N Engl J Med 2012;366:199–201.

25. Liben S, Papadatou D, Wolfe J: Paediatric palliative care: Challenges and emerging ideas. Lancet 2008;371:852–864.

26. National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care: Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care, Second Edition. www.nationalconsensusproject.org/guideline.pdf (Last accessed February 9, 2013).

27. National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization's Standards for Pediatric Palliative and Hospice Care. www.nhpcoorg/quality/nhpco's-standards-pediatric-palliative-.and-hospice-care (Last accessed February 6, 2013).

28. Payne S, Chan N, Davies A, et al: Supportive, palliative, and end-of-life care for patients with cancer in Asia: Resource-stratified guidelines from the Asian Oncology Summit 2012. Lancet Oncol 2012;13:e492–500.

29. Payne S, Leget C, Peruselli C, Radbruch L: Quality indicators for palliative care: Debates and dilemmas. Palliat Med 2012;26:679.

30. Sepúlveda C, Marlin A, Yoshida T, Ullrich A: Palliative care: The World Health Organization's global perspective. J Pain Symptom Manage 2002;24:91–96.

31. Steering Committee of the EAPC Task Force on Palliative Care for Children and Adolescents: IMPaCCT: Standards for Paediatric Palliative Care in Europe. Eur J Pall Care 2007;14:109–114.

32. Tang ST, Hung T, Liu T, et al: Pediatric end-of-life care for Taiwanese children who died as a result of cancer from 2001 through 2006. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:890–894.

33. Tubbs-Cooley HL, Santucci G, Kang TI, et al: Pediatric nurses' individual and group assessments of palliative, end-of-life, and bereavement care. J Palliat Med 2011;14:631–637.

34. Vickers J, Thompson A, Collins GS, et al: Place and provision of palliative care for children with progressive cancer: a study by the Paediatric Oncology Nurses' Forum/United Kingdom Children's Cancer Study Group Palliative Care Working Group. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:4472–4476.

35. Vollenbroich R, Duroux A, Grasser M, et al: Effectiveness of a pediatric palliative home care team as experienced by parents and health care professionals. J Palliat Med 2012;15:294–300.

36. Weissman DE, Meier DE, Spragens LH: Center to Advance Palliative Care palliative care consultation service metrics: Consensus recommendations. J Palliat Med 2008;11:1294–1298.

37. Weissman DE, Meier DE: Center to advance palliative care inpatient unit operational metrics: Consensus recommendations. J Palliat Med 2009;12:21–25.

38. Wolfe J, Hammel JF, Edwards KE, et al: Easing of suffering in children with cancer at the end of life: Is care changing? J Clin Oncol 2008;26:1717–1723.

39. Wolff J, Robert R, Sommerer A, Volz-Fleckenstein M: Impact of a pediatric palliative care program. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2010;54:279–283.

40. World Health Organization: National cancer control programmes core capacity self-assessment tool, 2011. www.who.int/cancer/publications/nccp_tool2011/en/index.html (Last accessed October 2, 2013).

41. Wright M, Wood J, Lynch T, Clark D: Mapping levels of palliative care development: A global view. J Pain Symptom Manage 2008;35:469–485.

Appendix D.

Publications in the Systematic Review

| Sub-Saharan Africa | |

|---|---|

| Malawi | Israels T, Banda K, Molyneux EM: Paediatric oncology in the Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Blantyre. Malawi Med J 2008;20:115–117. |

| Lavy V: Presenting symptoms and signs in children referred for palliative care in Malawi. Palliat Med 2007;21:333–339. | |

| South Africa | Clifton CE: Sparrow Ministries—A South African hospice. Posit Aware 2003;14:26. |

| Henley LD: End of life care in HIV-infected children who died in hospital. Dev World Bioeth 2002;2:38–54. | |

| Knapp C, Madden V, Marston J, et al: Innovative pediatric palliative care programs in four countries. J Palliat Care 2009;25:132–136. | |

| Uganda | Amery JM, Rose CJ, Holmes J, et al: The beginnings of children's palliative care in Africa: Evaluation of a children's palliative care service in Africa. J Palliat Med 2009;12:1015–1021. |

| De Baets AJ, Bulterys M, Abrams EJ, et al: Care and treatment of HIV-infected children in Africa: Issues and challenges at the district hospital level. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2007;26:163–173. | |

| Downing J, Birtar D, Chambers L, et al: Children's palliative care: A global concern. Int J Palliat Nurs 2012;18:109–114. | |

| South Asia | |

|---|---|

| Pakistan | Ashraf MS: Pediatric oncology in Pakistan. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2012;34:S23–25. |

| Shad A, Ashraf MS, Hafeez H: Development of palliative-care services in a developing country: Pakistan. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2011;33:S62–63. | |

| Silbermann M, Al-Hadad S, Ashraf S, et al: MECC Regional Initiative in Pediatric Palliative Care: Middle Eastern course on pain management. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2012;34:S1–11. | |

| Europe and Central Asia | |

|---|---|

| Albania | Birtar D: National viewpoint. An update on paediatric palliative care in Romania. Eur J Palliat Care 2007;14:256–259. |

| Dangel T: Pediatric palliative care in Europe. J Pain Symptom Manage 2002;24:2160–2165. | |

| Belarus | Becker R: The legacy of Chernobyl: Palliative services making a difference in Belarus. Int J Palliat Nurs 2006;12:318–319. |

| Costello J, Gorchakova A: Palliative care for children in the Republic of Belarus. Int J Palliat Nurs 2004;10:197–200 | |

| Dangel T: Pediatric palliative care in Europe. J Pain Symptom Manage 2002;24:2160–2165. | |

| Bulgaria | Dangel T: Pediatric palliative care in Europe. J Pain Symptom Manage 2002;24:2160–2165. |

| Latvia | Dangel T: Pediatric palliative care in Europe. J Pain Symptom Manage 2002;24:2160–2165. |

| Fedullo E, Jansone A, Ignatenko E: Innovative home care and hospice: Cross-partnerships in Russia and Latvia. Caring 2004;23:22–25. | |

| Hare A, Gorchakova A: The growth of palliative care for children in Latvia. Eur J Palliat Care 2004;11:116–118. | |

| Moldova | Birtar D: National viewpoint. An update on paediatric palliative care in Romania. Eur J Palliat Care 2007;14:256–259. |

| Dangel T: Pediatric palliative care in Europe. J Pain Symptom Manage 2002;24:2160–2165. | |

| Romania | Birtar D: National viewpoint. An update on paediatric palliative care in Romania. Eur J Palliat Care 2007;14:256–259. |

| Cowling K, Fowler-Kerry S: Developing a paediatric hospice programme in Romania. Eur J Palliat Care 2004;11:73–74. | |

| Dangel T: Pediatric palliative care in Europe. J Pain Symptom Manage 2002;24:2160–2165. | |

| Downing J, Birtar D, Chambers L, et al: Children's palliative care: A global concern. Int J Palliat Nurs 2012;18:109–114. | |

| Humphries J: Hospice care in Romania. Paediatr Nurs 2005;17:20–22. | |

| Turkey | Bingley A, Clark D: A comparative review of palliative care development in six countries represented by the Middle East Cancer Consortium (MECC). J Pain Symptom Manage 2009;37:287–296. |

| Kebudi R, Turkish Pediatric Oncology Group: Pediatric oncology in Turkey. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2012;34:S12–14. | |

| Silbermann M, Al-Hadad S, Ashraf S, et al: MECC Regional Initiative in Pediatric Palliative Care: Middle Eastern course on pain management. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2012;34:S1–11. | |

| Ukraine | Dangel T: Pediatric palliative care in Europe. J Pain Symptom Manage 2002;24:2160–2165. |

| Latin America and the Caribbean | |

|---|---|

| Argentina | Downing J, Birtar D, Chambers L, et al: Children's palliative care: A global concern. Int J Palliat Nurs 2012;18:109–114. |

| Kiman R. Varela MC, Requena ML: Establishing a paediatric palliative care team in an Argentinian hospital. Eur J Palliat Care 2011;18:40–45. | |

| Costa Rica | Irola Moya JC, Garro Morales M: Pediatric palliative care, Costa Rica's experience. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2010;27:456–464. |

| Middle East and North Africa | |

|---|---|

| Egypt | El Shami M: Palliative care: Concepts, needs, and challenges: Perspectives on the experience at the Children's Cancer Hospital in Egypt. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2011;33:S54–55. |

| Bingley A, Clark D: A comparative review of palliative care development in six countries represented by the Middle East Cancer Consortium (MECC). J Pain Symptom Manage 2009;37:287–296. | |

| Silbermann M, Al-Hadad S, Ashraf S, et al: MECC Regional Initiative in Pediatric Palliative Care: Middle Eastern course on pain management. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2012;34:S1–11. | |

| Iran | Silbermann M, Al-Hadad S, Ashraf S, et al: MECC Regional Initiative in Pediatric Palliative Care: Middle Eastern course on pain management. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2012;34:S1–11. |

| Iraq | Al-Hadad SA, Al-Jadiry MF, Al-Darraji AF, et al: Reality of pediatric cancer in Iraq. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2011;33(Suppl 2):S154–156. |

| Silbermann M, Al-Hadad S, Ashraf S, et al: MECC Regional Initiative in Pediatric Palliative Care: Middle Eastern course on pain management. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2012;34:S1–11. | |

| Jordan | Al-Rimawi HS: Pediatric oncology situation analysis (Jordan). J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2012;34:S15–18. |

| Bingley A, Clark D: A comparative review of palliative care development in six countries represented by the Middle East Cancer Consortium (MECC). J Pain Symptom Manage 2009;37:287–296. | |

| Finley GA, Forgeron P, Arnaout M: Action research: Developing a pediatric cancer pain program in Jordan. J Pain Symptom Manage 2008;35:447–454. | |

| Silbermann M, Al-Hadad S, Ashraf S, et al: MECC Regional Initiative in Pediatric Palliative Care: Middle Eastern course on pain management. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2012;34:S1–11. | |

| Lebanon | Abu-Saad Huijer H: Pediatric palliative care. State of the art. J Med Liban 2008;56:86–92. |

| Noun P, Djambas-Khayat C: Current status of pediatric hematology/oncology and palliative care in Lebanon: A physician's perspective. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2012;34:S26–27. | |

| Saad R, Huijer HA, Noureddine S, et al: Bereaved parental evaluation of the quality of a palliative care program in Lebanon. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2011;57:310–316. | |

| Silbermann M, Al-Hadad S, Ashraf S, et al: MECC Regional Initiative in Pediatric Palliative Care: Middle Eastern course on pain management. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2012;34:S1–11. | |

| Morocco | Hessissen L, Madani A: Pediatric oncology in Morocco: Achievements and challenges. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2012;34:S21–22. |

| Silbermann M, Al-Hadad S, Ashraf S, et al: MECC Regional Initiative in Pediatric Palliative Care: Middle Eastern course on pain management. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2012;34:S1–11. | |

| Palestine | Bingley A, Clark D: A comparative review of palliative care development in six countries represented by the Middle East Cancer Consortium (MECC). J Pain Symptom Manage 2009;37:287–296. |

| Silbermann M, Al-Hadad S, Ashraf S, et al: MECC Regional Initiative in Pediatric Palliative Care: Middle Eastern course on pain management. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2012;34:S1–11. | |

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by institutional training grant T32 CA080208-06 from the National Institutes of Health (A.C.B.) and the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (S.C.H., J.N.B., R.C.R., C.G.L.). Sources of funding were not involved in any aspect of the review.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.World Health Organization: WHO definition of palliative care 2012. www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/ (Last accessed October21, 2013)

- 2.World Health Organization: Strengthening palliative care as a component of integrated treatment within the continuum of care 2014. http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/EB134/B134_R7-en.pdf (Last accessed February1, 2014)

- 3.Children's Hospice International: About children's hospice, palliative and end-of-life care 2012. www.chionline.org/resources/about.php (Last accessed January29, 2014)

- 4.Sullivan R, Kowalczyk JR, Agarwal B, et al. : New policies to address the global burden of childhood cancers. Lancet Oncol 2013;14:e125–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization: Pediatric HIV data and statistics 2011. www.who.int/hiv/topics/paediatric/data/en/index1.html (Last accessed February8, 2014)

- 6.Patton GC, Coffey C, Sawyer SM, et al. ,: Global patterns of mortality in young people: A systematic analysis of population health data. Lancet 2009;374:881–892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ribeiro RC, Steliarova-Foucher E, Magrath I, et al. : Baseline status of pediatric oncology care in ten low-income or mid-income countries receiving My Child Matters support: A descriptive study. Lancet Oncol 2008;9:721–729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Howard SC, Metzger ML, Wilimas JA, et al. ,: Childhood cancer epidemiology in low-income countries. Cancer 2008;112:461–472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Israels T, Ribeiro RC, Molyneux EM: Strategies to improve care for children with cancer in Sub-Saharan Africa. Eur J Cancer 2010;46:1960–1966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ddungu H: Palliative care: What approaches are suitable in developing countries. Br J Haematol 2011;154:728–735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harding R, Higginson IJ: Palliative care in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet 2005;365:1971–1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Christianson A, Howson CP, Modell B: March of Dimes global report on birth defects: The hidden toll of dying and disabled children. March of Dimes Birth Defects Foundation, 2006. www.marchofdimes.com/downloads/Birth_Defects_Report-PF.pdf (Last accessed January28, 2014)

- 13.Aygun B, Odame I: A global perspective on sickle cell disease. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2012;59:386–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Connor SR, Bermedo MCS. (eds): Global Atlas of Palliative Care at the End of Life. Worldwide Palliative Care Alliance and the World Health Organization, 2014. www.who.int/nmh/Global_Atlas_of_Palliative_Care.pdf (Last accessed March4, 2014)

- 15.Liben S, Papadatou D, Wolfe J: Paediatric palliative care: Challenges and emerging ideas. Lancet 2008;371:852–864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gomes B, Harding R, Foley KM, Higginson IJ: Optimal approaches to the health economics of palliative care: Report of an international think tank. J Pain Symptom Manage 2009;38:4–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coombes R: Palliative care toolkit is developed for staff in countries ‘swamped by volume of suffering.’ Br J Haematol 2008;336:913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crane K: Palliative care gains ground in developing countries. J Natl Cancer Inst 2010;102:1613–1615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knapp C, Woodworth L, Wright M, et al. : Pediatric palliative care provision around the world: A systematic review. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2011;57:361–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.International Observatory on End of Life Care. Lancaster University; 2008–2012. www.lancs.ac.uk/shm/research/ioelc/ (Last accessed February8, 2013) [Google Scholar]

- 21.Delgado E, Barfield RC, Baker JN, et al. ,: Availability of palliative care services for children with cancer in economically diverse regions of the world. Eur J Cancer 2010;46:2260–2266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harding R, Albertyn R, Sherr L, Gwyther L: Pediatric palliative care in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review of the evidence for care models, interventions and outcomes. J Pain Symptom Manage 2014;47:642–651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.The World Bank Group: Open Data Catalog 2013. http://data.worldbank.org/ (Last accessed January23, 2014)

- 24.World Health Organization: Young people: Health risks and solutions 2011. www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs345/en/ (Last accessed Janaury 10, 2014)

- 25.Fraser LK, Miller M, Hain R, et al. : Rising national prevalence of life-limiting conditions in children in England. Pediatrics 2012;4:e923–929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. : The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare intervention: Explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009;339:b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Payne S, Leget C, Peruselli C, Radbruch L: Quality indicators for palliative care: Debates and dilemmas. Palliat Med 2012; 26: 679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Economist Intelligence Unit: The quality of death: Ranking end-of-life care across the world 2010. http://graphics.eiu.com/upload/QOD_main_final_edition_Jul12_toprint.pdf (Last accessed February8, 2014)

- 29.National Quality Forum: A national framework and preferred practices for palliative and hospice care quality: A consensus report 2006. www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2006/12/A_National_Framework_and_Preferred_Practices_for_Palliative_and_Hospice_Care_Quality.aspx (Last accessed February8, 2014)

- 30.Wolfe J, Hammel JF, Edwards KE, et al. ,: Easing of suffering in children with cancer at the end of life: Is care changing? J Clin Oncol 2008;26:1717–1723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Payne S, Chan N, Davies A, et al. : Supportive, palliative, and end-of-life care for patients with cancer in Asia: Resource-stratified guidelines from the Asian Oncology Summit 2012. Lancet Oncol 2012;13:e492–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.De Lima L, Bennett MI, Murray SA: International Association for Hospice and Palliative Care (IAHPC) List of Essential Practices in Palliative Care. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother 2012;26:118–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wright M, Wood J, Lynch T, Clark D: Mapping levels of palliative care development: A global view. J Pain Symptom Manage 2008;35:469–485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Systems to rate the strength of scientific evidence. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment: number 47. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Critical Appraisal Skills Programme: Appraising the evidence: CASP appraisal checklists 2010. www.casp-uk.net/find-appraise-act/appraising-the-evidence/ (Last accessed June18, 2013)

- 36.Human Development Reports: United Nations Development Programme: Multidimensional poverty index 2011. http://hdr.undp.org/en/statistics/mpi/ (Last accessed February8, 2014)

- 37.Pain and Policy Studies Group: Opioid consumption data: Country profiles. University of Wisconsin-Madison; 2010–2012. www.painpolicy.wisc.edu/countryprofiles (Last accessed February8, 2014) [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aindow A, Brook L: Essential medicines list for children (EMLc); palliative care. World Health Organization, 2008. www.who.int/selection_medicines/committees/subcommittee/2/palliative.pdf (Last accessed January30, 2014)

- 39.Amery J: Mapping children's palliative care around the world: An online survey of children's palliative care services and professionals' educational needs. J Palliat Med 2012;15:646–652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Collins K, Harding R: Improving HIV management in sub-Saharan Africa: How much palliative care is needed? AIDS Care 2007;19:1304–1306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Amery JM, Rose CJ, Holmes J, et al. : The beginnings of children's palliative care in Africa: Evaluation of a children's palliative care service in Africa. J Palliat Med 2009;12:1015–1021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.De Baets AJ, Bulterys M, Abrams EJ, et al. ,: Care and treatment of HIV-infected children in Africa: Issues and challenges at the district hospital level. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2007;26:163–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zimba EW, McInerney PA: The knowledge and practices of primary care givers regarding home-based care of HIV/AIDS children in Blantyre (Malawi). Curationis 2001;24:83–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Biggs B, King L, Basu S, Stuckler D: Is wealthier always healthier? The impact of national income level, inequality, and poverty on public health in Latin America. Soc Sci Med 2010;71:266–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Muldoon KA, Galway LP, Nakajima M, et al. : Health system determinants of infant, child and maternal mortality: A cross-sectional study of UN member countries. Global Health 2011;7:42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sureshkumar K, Rajagopal MR: Palliative care in Kerala. Problems at presentation in 440 patients with advanced cancer in a south Indian state. Palliat Med 1996;10:293–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.World Health Organization: Palliative care: Symptom management and end-of-life care 2004. www.who.int/hiv/pub/imai/genericpalliativecare082004.pdf (Last accessed February8, 2013)

- 48.Cherny NI, Cleary J, Scholten W, et al. : Opioid availability and accessibility for the relief of cancer pain in Africa, Asia, India, the Middle East, Latin America and the Caribbean: Final Report of the International Collaborative Project. Ann Oncol 2013;24(Suppl 11):xi7–xi13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]