Abstract

Aim

To evaluate the effect of lymphadenectomy and/or radiotherapy on recurrence and survival patterns in endometrial carcinoma (EC) in a radiotherapy reference centre population.

Material and Methods

A retrospective population-based review was conducted on 261 patients with stages I–III EC. Univariate and multivariate analyses were carried out. Both recurrence and survival were analysed according to patient age, FIGO stage, tumour size, myometrial invasion, tumour grade, lymphadenectomy, external beam irradiation (EBI), and brachytherapy (BT).

Results

Median age: 64.8 years. Median follow-up: 151 months. The following treatments were administered: surgery, 97.32%; lymph-node dissection, 54.4%; radiotherapy, 162 patients (62%) (EBI and BT: 64.1%, BT alone: 30.2%, EBI alone: 5.6%).

Twenty-six patients (9.96%) suffered loco-regional recurrence, whilst 27 (10.34%) suffered distant failure. The 5-year overall survival (OS) for all stages was 80.1%. The 5-year disease free survival (DFS) was 92.1% for all patients. The 10-year DFS was 89.9%.

The independent significant prognostic factors for a good outcome identified through the multivariate analysis were: age <75 years (p = 0.001); tumour size ≤2 cm (p = 0.003); myometrial invasion ≤50% (p = 0.011); lymphadenectomy (p = 0.02); EBI (p = 0.001); and BT (p = 0.031).

Toxicity occurred in 114 of the 162 patients who received radiotherapy (70.5%). The toxicity was mainly acute, and late in only 28.3% (n = 45) of cases. The majority experienced G1-2 toxicity, and only 3% of patients experienced G3 late toxicity (5/162).

Conclusions

Our results suggest that age <75 years, tumour size ≤2 cm, myometrial invasion ≤50%, lymphadenectomy, EBI, and BT, are predictors of a good outcome in EC.

Keywords: Endometrial carcinoma, Prognostic factors, Radiotherapy, Lymphadenectomy

1. Background

Endometrial carcinoma (EC) is the third most common cancer diagnosed in women and the most common female genital tract malignancy. The incidence of EC in Catalonia (Spain) is 730 new cases per year. EC represents 6.1% of newly diagnosed cancers in women.1,2

Treatment of EC is mainly surgical and consists of a total abdominal hysterectomy and a bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (TAH & BSO), with or without pelvic lymph node dissection, followed by postoperative radiotherapy (RT) in most cases. Surgical staging requires the expertise of a gynaecological oncologist in a tertiary care centre. The need for lymphadenectomy remains a point of controversy. Some studies have confirmed that lymphadenectomy can be both diagnostic and therapeutic, and that it allows for more adaptable postoperative RT; others have concluded that there is no evidence of any benefit in terms of overall survival (OS).3–7 However, many studies have confirmed advantages to lymphadenectomy such as: reduced complexity8; increased accuracy of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in pre-operative staging9; and better prognostics.10,11

Prospective randomised studies have shown that RT reduces the risk of pelvic relapse but does not improve OS in patients with early EC.12–14 The Postoperative Radiotherapy Endometrial Cancer (PORTEC-2) study demonstrated that patients with intermediate-risk EC can be safely treated with brachytherapy (BT) alone.15

The decision to offer adjuvant pelvic radiation depends on the type of surgery undertaken, as well as the primary tumour risk factors. In intermediate-risk groups, pelvic radiation may be offered if the patient exhibits adverse prognostic factors. The risk of metastatic pelvic nodes increases in high-risk groups, and therefore, pelvic RT is often offered.16–21

Despite the fact that postoperative external beam pelvic RT is offered to minimise the risk of recurrence in case of poor prognostic factors, severe late complications have been reported, occurring mainly in the small bowel, in 3–8% of cases treated with external beam pelvic RT.14–22

The Radiation Department at the Hospital Universitari de Sant Joan de Reus is the only referral RT centre in Tarragona Province and receives patients from 7 hospitals performing gynaecological cancer surgery.

2. Aim

The aim of this retrospective study was to determine the prognostic factors that contribute to patient outcomes, and to evaluate the roles and impact on survival of lymphadenectomy and/or RT in EC in this RT reference centre population.

3. Materials and methods

A retrospective population-based review was conducted on 261 patients with stages I–III EC (excluding sarcoma cases) that were treated in one Radiation Oncology Institution after referral from seven different gynaecology departments during the period 1997 to 2006.

Information regarding patients, disease, and treatment characteristics were retrospectively collected from the patient records. After surgery, the patients were staged according to the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (FIGO-1992). The surgical procedure, pathologic characteristics of the tumour, RT, chemotherapy, and distance travelled by patients from their home to our centre were recorded.

The lymphadenectomy policies varied among the different centres, but in general it was offered to high risk of recurrence patients. Our institution's protocol during the treatment period (1997–2006) indicated an adjuvant postoperative external beam RT to the pelvis without lymphadenectomy for women with disease stage IB grade 2, stage IB grade 3, all grades of stage IC, and all higher stages. Postoperative adjuvant RT consisted of external beam pelvic radiation, vaginal BT, or both. The time between surgery and RT treatment did not exceed 4 weeks.

Clinical, surgical and pathological data were considered when planning 3D conformal radiotherapy planning treatment. The majority of patients were treated with 6 or 18 MV from a Linac ray (66% of patients), or a 60-cobalt machine (33% of patients) using the pelvic four-field technique. The total planned dose was 46–50 Gy at 180–200 cGy per fraction, 5 fractions/week. BT was administered using the Fletcher colpostats technique for low-dose rate (LDR) 137Cs sources from a Selectron, or using a vaginal cylinder applicator in one or three treatments with a high-dose rate (HDR). After external beam irradiation (EBI), the usual BT plan involved 20 Gy for LDR treatments and 3 fractions of 4 Gy for HDR treatments. When only BT was performed, the dose was 60 Gy for LDR treatments and 3 fractions of 7 Gy for HDR treatments. All BT doses were prescribed for 5 mm inside the vaginal surface.

After the completion of the RT, a radiation oncologist routinely monitored women every 3–4 months for 2 years, and every 6 months thereafter.

3.1. Statistical analysis

We evaluated OS, disease-free survival (DFS), and loco-regional free-survival (LRFS). The results were analysed using SPSS, and statistical comparisons (OS, DFS and LFRS rates) were carried out using the log-rank test. Univariate and multivariate analyses of the corresponding variables were undertaken for the OS, DFS and LFRS endpoints, including analyses of lymphadenectomy, RT, and prognostic factors for survival such as age, tumour size, and myometrial invasion. Univariate analysis was undertaken using the chi-square test. Multivariate analyses were undertaken using the Cox proportional hazards model. A ρ value <0.05 was considered to be significant.

4. Results

The mean patient age was 64.8 years (range 38–88). The mean follow-up time was 151 months. 85% percent of the patients lived within 70 km of the oncology centre, whilst 15% lived over 70 km away.

The stage and pathologic characteristics of the samples are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Stage and pathologic characteristics of all patients.

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| FIGO stage | |

| I | 175 (67%) |

| II | 47 (18%) |

| III | 39 (15%) |

| Histological type | |

| Endometrioid adenocarcinoma | 195 (74.7%) |

| Papillary – serous | 19 (7.3%) |

| Clear-cell | 10 (3.8%) |

| Other | 37 (14.2%) |

| Pathological grade | |

| I | 104 (39.8%) |

| II | 108 (41.4%) |

| III | 49 (18.8%) |

| Tumour size (cm) | |

| ≤2 cm | 224 (85%) |

| >2 cm | 37 (14.2%) |

| Myometrial invasion | |

| No invasion | 21 (8%) |

| >50% | 112 (43%) |

| <50% | 128 (49%) |

The treatments that were performed are described in Table 2. The mean dose for external beam RT was 48.6 ± 6 Gy, prescribed at the isocentre. The mean number of pelvic lymph nodes removed was 14 (2–47), and a mean of 7 (1–14) paraortic lymph nodes were removed.

Table 2.

Treatment performed on all patients.

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Surgery | 256 (98%) |

| Abdominal HT&DA | 229 (87.7%) |

| Vaginal HT&DA | 32 (12.3%) |

| Lymph node dissection | 142 (54.4%) |

| Pelvic | 85 (32.6%) |

| Pelvic + paraortic | 53 (20.3%) |

| Paraortic alone | 4 (1.5%) |

| Mean number pelvic lymph nodes | 14 (2–47) |

| Mean number paraortic lymph nodes | 7 (1–14) |

| Radiation treatment | 162 (62%) |

| EBI and BT | 104 (64.1%) |

| BT alone | 49 (30.2%) |

| EBI alone | 9 (5.6%) |

| Chemotherapy | 11.51% |

| Hormonal therapy | 6.3% |

HT&DA: hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy; EBI: external beam irradiation; BT: brachytherapy.

Patient's characteristics according to the lymphadenectomy or RT treatment are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Patient's characteristics according to the lymphadenectomy or radiotherapy treatment.

|

N (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lymphadenectomy |

Radiotherapy |

|||

| No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Median age (years) | 66.4 | 61.4 | 63.9 | 64 |

| FIGO stage | ||||

| I | 79 (66.4%) | 96 (67.6%) | 85 (85.9%) | 90 (55.6%) |

| II | 25 (21%) | 22 (15.5%) | 8 (8%) | 39 (24%) |

| III | 15 (12.5%) | 24 (16.9%) | 6 (5%) | 33 (20.4%) |

| Histological type | ||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 78 (65.6%) | 117 (82.4%) | 70 (70.7%) | 125 (77.2%) |

| Papillary – serous | 10 (8.4%) | 9 (6.3%) | 9 (9%) | 10 (6.2%) |

| Clear-cell | 4 (3.4%) | 6 (4.2%) | 10 (10.1%) | 17 (10.5%) |

| Other | 27 (22.7%) | 10 (7%) | 10 (10.1%) | 10 (6.2%) |

| Pathological grade | ||||

| I | 49 (41.2%) | 55 (38.7%) | 44 (44.4%) | 60 (37%) |

| II | 55 (46.2%) | 53 (37.3%) | 45 (45.6%) | 63 (38.9%) |

| III | 15 (12.6%) | 34 (23.9%) | 10 (10%) | 39 (24%) |

| Myometrial invasion | ||||

| No invasion | 11 (9.2%) | 10 (7%) | 9 (9%) | 12 (7.4%) |

| >50% | 62 (52.1%) | 50 (35.2%) | 60 (60.6%) | 52 (32%) |

| <50% | 46 (38.7%) | 82 (57.7%) | 30 (30.3%) | 98 (60.5%) |

Relapses: 26 of the 261 patients (9.96%) suffered loco-regional recurrence. The recurrence rates for stages I, II and III were 9.26%, 4.65% and 13.89% respectively. 27 of the 261 patients (10.34%) suffered distant failure, with pulmonary metastases occurring most frequently. Recurrences were treated with surgery ± RT ± chemotherapy ± hormonal treatment.

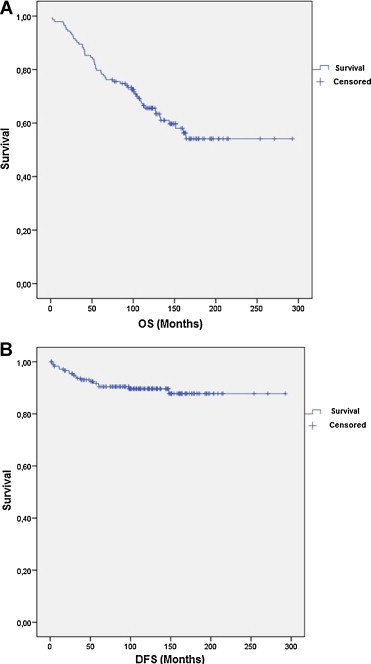

5 and 10-year survival (Fig. 1): The 5 and 10-year OS for all stages was 80.1% and 65.6% respectively (Fig. 1A). The 5 and 10-year OS for stage I was 84% and 68.2% respectively; 90.3% and 78.4% respectively for stage II; and 64.5% and 52.4% respectively for stage III. There was a statistically significant difference in OS between stages I/II versus III (84% vs. 64.5%; p = 0.0016). The 5 and 10-year DFS was 92.1% and 89.9% for all patients respectively (Fig. 1B). The 5 and 10-year DFS for stages I was 93.5% and 89.1% respectively; 97.5% and 93.9% respectively for stage II; and 79.8% and 89.4% respectively for stage III. No differences were found in DFS between stages I/II versus III.

Fig. 1.

Overall survival (OS) (A) and disease-free survival (DFS) (B) in all patients.

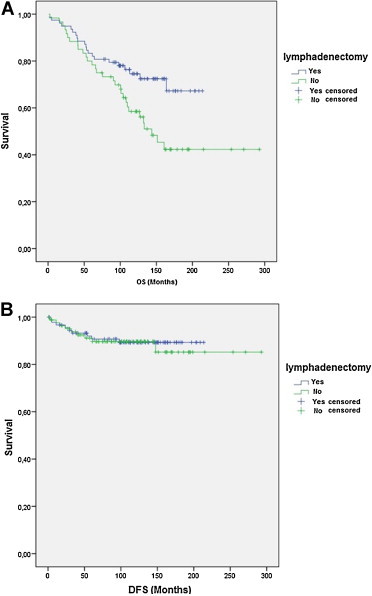

The observed 5 and 10-year OS rates in patients that received lymphadenectomy were 86% and 77.7% respectively, and were 78.4% and 54.2% respectively for those who did not receive a lymphadenectomy (HR 2.821, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.566–5.080; p = 0.020) (Fig. 2A). There was a significant difference in the survival curves for these two groups (p = 0.000, log-rank test). The 5 and 10-year DFS was 93.5% and 91.5% for lymphadenectomy vs. no lymphadenectomy being performed (p = 0.462, log-rank test) (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Overall survival (OS) (A) and disease-free survival (DFS) (B) in patients that did and did not receive lymphadenectomy.

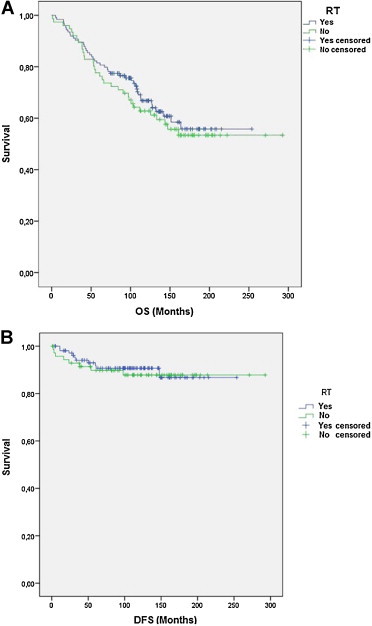

No differences were observed in 5 and 10-year OS with respect to RT administration (p = 0.527, log-rank test) (Fig. 3A), and the 5 and 10-year DFS was the same (92.1%) in both cases (RT and non-RT groups) (p = 0.795, log-rank test) (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Overall survival (OS) (A) and disease-free survival (DFS) (B) in patients with respect to administered radiotherapy treatment.

4.1. Prognostic factors

Univariate analyses revealed the following significant prognostic factors of a good outcome: age <75 years (p = 0.000); FIGO stage (I–II vs. IIII, p = 0.026); tumour size ≤2 cm (p = 0.003); grade of differentiation (grade I and II vs. III, p = 0.007); myometrial invasion <50% (p = 0.000); and BT (p = 0.000).

The independent significant prognostic factors of a good outcome from multivariate analysis were: age <75 years (p = 0.001); tumour size ≤2 cm (p = 0.003); myometrial invasion ≤50% (p = 0.011); lymphadenectomy (p = 0.02); RT (p = 0.001); and BT (p = 0.031).

4.2. Differences according to gynaecological practice (Table 4)

Table 4.

Treatment characteristics in the different surgical hospitals.

| Hospital | Number of patients | Stages | Lymphadenectomy | Radiotherapy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||

| A | 80 | I: 50 (62.5%) | 43 (53.7%) | 49 (61.3%) |

| II: 20 (25%) | ||||

| III: 10 (12.5%) | ||||

| B | 45 | I: 35 (77.8%) | 27 (60%) | 19 (42.2%) |

| II: 4 (8.9%) | ||||

| III: 6 (13.3%) | ||||

| C | 36 | I: 24 (66.7%) | 31 (86.1%) | 21 (58.3%) |

| II: 7 (19.4%) | ||||

| III: 5 (13.9%) | ||||

| D | 36 | I: 21 (58.3%) | 17 (47.2%) | 32 (88.9%) |

| II: 6 (16.7%) | ||||

| III: 9 (25%) | ||||

| E | 14 | I: 12 (85.7%) | 6 (42.9%) | 11 (78.6%) |

| II: 0% | ||||

| III: 2 (14.3%) | ||||

| F | 16 | I: 9 (56.3%) | 8 (50%) | 10 (62.5%) |

| II: 4 (25%) | ||||

| III: 3 (18.8%) | ||||

| G | 33 | I: 25 (75.8%) | 8 (24.2%) | 19 (57.6%) |

| II: 4 (12.1%) | ||||

| III: 4 (12.1%) | ||||

There was a large variation in treatment practicesacross Tarragona province, mainly in the lymphadenectomy percentages among the referring gynaecology units (chi-square test, p = 0.000, range 24–85.71%). This data did not translate into 5-year OS or DFS differences in the multivariate analysis (HR 1.000, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.880–1.138; p = 0.994). When we performed the analysis based on treatments, no significant improvement in OS and DFS was observed when RT was administered to the patients without a lymphadenectomy (p = 0.099 and p = 0.612 for OS and DFS respectively).

4.3. RT toxicity

We evaluated acute and late toxicity based on both the RTOG and LENT-SOMA scoring systems. All patients tolerated irradiation without interruption of their treatment. Toxicity occurred in 114 patients of the 162 patients that received RT (70.5%), and the remaining 48 patients (29.5%) did not suffer any toxicity. It was mainly acute toxicity, with late toxicity occurring in only 28.3% (n = 45) of cases. The majority of them experienced G1-2 toxicity (70%). Acute G3-4 toxicity appeared in 4.3% (7/162) (5 patients experienced G3 gastrointestinal toxicity, 1 patient experienced G3 bladder toxicity, and 1 patient experienced G4 gastrointestinal toxicity) and G3-4 late toxicity appeared in 3% (5/162) of patients (3 cases in the colon and small intestine, 1 case with rectal toxicity, and 1 with bladder toxicity). A Co-60 treatment was administered in 11 of 12 cases with grade 3 and 4 toxicity (acute and late toxicity).

5. Discussion

This study was performed to retrospectively evaluate population-based results in 261 cases of EC in Tarragona, Spain. Different parameters were analysed in this study in order to determine their influence on recurrence and survival.

We found that classical prognostic factors such as advanced age, stage, tumour size, deep myometrial invasion, and high grades, predict lower OS and DFS rates, supporting similar reports in the literature.14,23–25 We analysed the impact of lymphadenectomy and RT on OS and DFS.

Different studies have demonstrated that patients with stage I EC have 5-year OS rates of 80–90%, and 5-year cancer-specific survival rates of 90–95%.13,26–29 In our study, the OS and the DFS for stage I was 84% and 93.5% respectively. Other authors have reported that patient cohorts with high-grade tumours and deep myometrial invasion (>50%) have a significantly higher risk of both locoregional and distant relapse.25 The Gynaecologic Oncology Group (GOG) study24 revealed that microscopic pelvic nodal metastases were present in 18% of patients with clinical stage I tumours and deep myometrial invasion (defined as invasion of the outer third of the myometrial wall), compared to their presence in under 10% of the remaining population.

RT toxicity in our study was similar to RT toxicity reported in other studies. Grade 3 and 4 late complications were seen in 3% of cases treated with EBI, and there was only one case of Grade 4. The majority of patients with grade 3 and 4 complications were treated with Co-60 machine. These results were similar to those reported in other studies.13 Reduction of rectal volume has been associated with lower rectal dose-volume parameters that could be a step in the reduction of toxicity.30

Lymphadenectomy is one of the controversial aspects of the surgical treatment of EC. More than half of our patients (54.4%) had lymphadenectomy, and a significant improvement in 5 and 10-year OS was observed in this group of patients in univariate analysis, but significance was lost in multivariate analysis. It appears to be useful in high-risk patients, and could be avoided in low-risk patients. More studies are therefore needed to answer these questions in more depth.31

The impact of RT was the remaining aspect of our study. The role of radiation therapy in EC has been investigated using randomised and retrospective series, and remains controversial in some stages.12–14,32,33 The randomised trial results reported by Aalders et al. revealed that the addition of EBI after TAH & BSO and vaginal BT led to reduced vaginal and pelvic recurrence rates, even though no statistically significant survival benefit was observed (5-year survival rate, 89% vs. 91%).12 This study also suggested a survival benefit for the patient subgroup with grade 3 tumours and deep (stage IC) myometrial invasion. The PORTEC-1 trial demonstrated a significant locoregional benefit with RT, and postoperative pelvic RT was indicated for patients over the age of 60, those with grade 3 EC, or those with grade 1–2 EC with >50% myometrial invasion.13,23 A phase III trial published by GOG demonstrated that postoperative pelvic RT significantly reduced the risk of recurrence in intermediate-risk patients, and that pelvic RT was recommended for patients in the high intermediate-risk category (grade 2–3 tumours with lymphovascular invasion and outer third myometrial invasion), patients over 50 years old with any of the 2 previously mentioned risk factors, and patients over 70 years old with any of the previously listed risk factors.14

The PORTEC-2 trial revealed that BT should be the adjuvant treatment of choice for patients with EC in the high intermediate-risk category.15

The PORTEC-3 study will clarify whether high-risk patients need external beam RT in addition to chemotherapy.

In our study, postoperative radiotherapy was administered to 62% (EBI and BT: 64.1%, BT alone: 30.2%, EBI alone: 5.6%) of patients, neither of which had an impact on 5 and 10-year OS and DFS (p = 0.527 and p = 0.795, respectively, log-rank test). In our study, the surgical centres that performed fewer lymphadenectomies referred patients for postoperative treatments more frequently; this may be a reason why the survival rates are similar and no significant differences in OS among the different surgical units were observed.

Despite clinical guides the usual practice shows large difference on lymphadenectomy numbers among centres and this has no impact on OS. Then we could hypothesise that RT could improve and homogenise outcomes of surgically treated EC.

Future analyses are necessary to clarify the role of systematic lymphadenectomy in EC, and to determine whether postoperative RT could be avoided in early stage EC.

6. Conclusion

Our results suggest that the predictors of a good outcome were: an older age, tumour size ≤2 cm, myometrial invasion ≤50%, as well as lymphadenectomy, EBI, and BT, in our population series with EC.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Financial disclosure

None declared.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Pilar Hernández and Alberto Ameijide for their support with the statistical analysis.

References

- 1.Marcos-Gragera R., Cardó X., Galceran J., Ribes J., Izquierdo A., Borràs J. Cancer incidence in Catalonia, 1998–2002. Med Clin (Barc) 2008;131(October (Suppl. 1)):4–10. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7753(08)76427-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cancer Registry in the province of Tarragona. Cancer in Tarragona from 1980 to 2001. Incidence, mortality, survival, prevalence. League Foundation for Cancer Research and Prevention.

- 3.Kilgore L.C., Partridge E.E., Alvarez R.D. Adenocarcinoma of the endometrium: survival comparisons of patients with and without pelvic node sampling. Gynecol Oncol. 1995;56:29–33. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1995.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Todo Y., Kato H., Kaneuchi M., Watari H., Takeda M., Sakuragi N. Survival effect of para-aortic lymphadenectomy in endometrial cancer (SEPAL study): a retrospective cohort analysis. Lancet. 2010;3(375):816–823. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)62002-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kitchener H., Swart A.M., Qian Q., Amos C., Parmar M.K. Efficacy of systematic pelvic lymphadenectomy in endometrial cancer (MRCA ASTEC trial): a randomised study. Lancet. 2009;373:125–136. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61766-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benedetti Panici P., Basile S., Maneschi F. Systematic pelvic lymphadenectomy vs no lymphadenectomy in early-stage endometrial: randomised clinical trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:1707–1716. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan J.K., Cheung M.K., Huh W.K. Therapeutic role of lymph node resection in endometrioid corpus cancer: a study of 12,333 patients. Cancer. 2006;107:1823–1830. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Werner H.M., Trovik J., Marcickiewicz J. Revision of FIGO surgical staging in 2009 for endometrial cancer validates to improve risk stratification. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;125:103–108. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ballester M., Koskas M., Coutant C. Does the use of the 2009 FIGO classification of endometrial cancer impact on indications of the sentinel node biopsy? BMC Cancer. 2010;10:465. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim H.S., Kim H.Y., Park C.Y. Lymphadenectomy increases the prognostic value of the revised 2009 FIGO staging system for endometrial cancer: a multi-center study. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2012;38:230–237. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2011.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cooke E.W., Pappas L., Gaffney D.K. Does the revised International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics staging system for endometrial cancer lead to increased discrimination in patient outcomes? Cancer. 2011;117:4231–4237. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aalders J., Abeler V., Kolstad P., Onsrud M. Postoperative external irradiation and prognostic parameters in stage I endometrial carcinoma: clinical and histopathologic study of 540 patients. Obstet Gynecol. 1980;56:419–427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Creutzberg C.L., van Putten W.L., Koper P.C. Surgery and postoperative radiotherapy versus surgery alone for patients with stage-1 endometrial carcinoma: multicentre randomised trial: PORTEC Study Group: Post Operative Radiation Therapy in Endometrial Carcinoma. Lancet. 2000;355:1404–1411. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02139-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keys H.M., Roberts J.A., Brunetto V.L. A phase III trial of surgery with or without adjunctive external pelvic radiation therapy in intermediate risk endometrial adenocarcinoma: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;92(3):744–751. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2003.11.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nout R.A., Smit V.T., Putter H. Vaginal brachytherapy versus pelvic external beam radiotherapy for patients with endometrial cancer of high-intermediate risk (PORTEC-2): an open-label, non-inferiority, randomized trial. Lancet. 2010;6(375):816–823. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)62163-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mariani A., Webb M.J., Keeney G.L., Lesnick T.G., Podratz K.C. Surgical stage I endometrial cancer: predictors of distant failure and death. Gynecol Oncol. 2002;87(3):274–280. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2002.6836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rose P.G. Endometrial carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:640–649. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199608293350907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pitson G., Colgan T., Levin W. Stage II endometrial carcinoma: prognostic factors and risk classification in 170 patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;53(4):862–867. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)02813-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mangili G., De Marzi P., Viganò R. Identification of high risk patients with endometrial carcinoma. Prognostic assessment of endometrial cancer. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2002;23(3):216–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yalman D., Ozsaran Z., Anacak Y. Postoperative radiotherapy in endometrial carcinoma: analysis of prognostic factors in 440 cases. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2000;21(3):311–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carey M.S., O’Connell G.J., Johanson C.R. Good outcome associated with a standardized treatment protocol using selective postoperative radiation in patients with clinical stage I adenocarcinoma of the endometrium. Gynecol Oncol. 1995;57(2):138–144. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1995.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Creutzberg C.L., van Putten W.L., Koper P.C. The morbidity of treatment for patients with Stage I endometrial cancer: results from a randomized trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;51(5):1246–1255. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(01)01765-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morrow C.P., Bundy B.N., Kurman R.J. Relationship between surgical-pathological risk factors and outcome in clinical stage I and II carcinoma of the endometrium: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol. 1991;40(1):55–65. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(91)90086-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Creasman W.T., Morrow C.P., Bundy B.N. Surgical pathologic spread patterns of endometrial cancer: a Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. Cancer. 1987;60:2035–2041. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19901015)60:8+<2035::aid-cncr2820601515>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Creutzberg C.L., van Putten W.L., Wárlám-Rodenhuis C.C. Outcome of high risk stage IC, grade 3, compared with stage I endometrial carcinoma patients: the Postoperative Radiation Therapy in Endometrial Carcinoma Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(7):1234–1241. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Creutzberg C.L., van Putten W.L., Koper P.C. Survival after relapse in patients with endometrial cancer: results from a randomized trial. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;89:201–209. doi: 10.1016/s0090-8258(03)00126-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Greven K.M., Corn B.W., Case D., Purser P., Lanciano R.M. Which prognostic factors influence the outcome of patients with surgically staged endometrial cancer treated with adjuvant radiation? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;39:413–418. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(97)00323-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Irwin C., Levin W., Fyles A., Pintilie M., Manchul L., Kirkbridge P. The role of adjuvant radiotherapy in carcinoma of the endometrium: results in 550 patients with pathologic stage I disease. Gynecol Oncol. 1998;70:247–254. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1998.5064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kucera H., Vavra N., Weghaupt K. Benefit of external irradiation in pathologic stage I endometrial carcinoma: a prospective clinical trial of 605 patients who received postoperative vaginal irradiation and additional pelvic irradiation in the presence of unfavorable prognostic factors. Gynecol Oncol. 1990;38:99–104. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(90)90018-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sabater S., Sevillano M., Andres I. Reduction of rectal doses by removal of gas in the rectum during vaginal cuff brachytherapy. Strahlenther Onkol. 2013;189(11):951–956. doi: 10.1007/s00066-013-0427-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dietl J. Is lymphadenectomy justified in endometrial cancer? Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2011;21(3):507–510. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0b013e31820d3e06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scholten A.N., van Putten W.L., Beerman H. Postoperative radiotherapy for Stage I endometrial carcinoma: long-term outcome of the randomized PORTEC trial with central pathology review. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;63:834–838. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scotti V., Borghesi S., Meattini I. Postoperative radiotherapy in Stage I/II endometrial cancer: retrospective analysis of 833 patients treated at the University of Florence. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2010;20(9):1540–1548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]