Abstract

Radiation-induced bystander effects are defined as biological effects expressed after irradiation by cells whose nuclei have not been directly irradiated. These effects include DNA damage, chromosomal instability, mutation, and apoptosis. There is considerable evidence that ionizing radiation affects cells located near the site of irradiation, which respond individually and collectively as part of a large interconnected web. These bystander signals can alter the dynamic equilibrium between proliferation, apoptosis, quiescence or differentiation. The aim of this review is to examine the most important biological effects of this phenomenon with regard to areas of major interest in radiotherapy. Such aspects include radiation-induced bystander effects during the cell cycle under hypoxic conditions when administering fractionated modalities or combined radio-chemotherapy. Other relevant aspects include individual variation and genetics in toxicity of bystander factors and normal tissue collateral damage. In advanced radiotherapy techniques, such as intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT), the high degree of dose conformity to the target volume reduces the dose and, therefore, the risk of complications, to normal tissues. However, significant doses can accumulate out-of-field due to photon scattering and this may impact cellular response in these regions. Protons may offer a solution to reduce out-of-field doses. The bystander effect has numerous associated phenomena, including adaptive response, genomic instability, and abscopal effects. Also, the bystander effect can influence radiation protection and oxidative stress. It is essential that we understand the mechanisms underlying the bystander effect in order to more accurately assess radiation risk and to evaluate protocols for cancer radiotherapy.

Keywords: Bystander effect, Radiotherapy, Fractionated radiotherapy, IMRT, Adaptive response

1. Introduction

Ionizing radiation affects not only the cells that are directly irradiated but also their non-irradiated neighbours. When non-irradiated cells respond to radiation, the response is known as the bystander effect. In general, the bystander effect mimics the direct effects of radiation including an increased frequency of apoptosis, micronucleation, DNA strand breaks and mutations, altered levels or activity of regulatory proteins and enzymes, reduced clonogenic efficiency, and oncogenic transformation. These responses have been attributed to signals transmitted directly through gap junctions and by factors released into the growth medium.

Results suggest that the genetic damage in cells exposed to scattered radiation is caused by factors released by irradiated cells into the medium rather than by DNA damage induced directly by X-rays. It seems that bystander effects may have important clinical implications for health risk after low-level radiation exposure of cells lying outside the radiation field during clinical treatment.1

In the present review, we highlight the issues and problems associated with radiation-induced bystander effects from a clinical perspective.

2. Types of radiation injuries

Radiation injuries are typically classified as either “early” or “late” injuries, depending on the time interval between exposure and clinical expression, and this simple system has served us well. This classification is based on two mechanistic models of injury, the “target cell” and “vascular injury” models. These two models support quantitative biomathematical modelling, using the very simple parameters of the linear quadratic model.

Incorporating bystander effects into the science underpinning clinical radiotherapy will involve moving beyond simple mechanistic models and towards a more system-based approach. The increasing knowledge of molecular mechanisms of radiation injury has provided us with opportunities to understand their genesis at a more basic level. The new formalism holds that lesions producing radiation injury fall into one of three categories: cytocidal effects, indirect effects, and functional effects (Table 1).

Table 1.

Lesions producing radiation injury.

| • Cytocidal effects |

| • Indirect effects |

| • Functional effects |

Cytocidal effects relate to the phenomena characterized by the “target cell” model. The time interval between irradiation and manifestation of injury depends on target cell characteristics (radiation sensitivity, repair capacity, proliferation rate, etc.) and tissue organization. Indirect effects refer to reactive phenomena that occur in response to radiation-induced injury in other cells or tissues (i.e., parenchymal cell depletion secondary to vascular damage). Indirect effects also include such phenomena as the bystander effect. Functional effects result from nonlethal effects on different intra- and extra-cellular molecules and changes in gene expression in irradiated cells. In most tissues, injury occurs through interactions that involve all three types of effects.

Assessment of radiation-induced bystander effects has not been limited exclusively to tissue culture analyses. In vivo experiments, performed as early as 1974, have also demonstrated the existence of such effects. Brooks et al.2 showed that when α-particle emitters are concentrated in the liver of Chinese hamsters, all cells in the liver are at the same risk for induction of chromosome damage, even though only a small fraction of the total liver cell population was actually exposed to α-particles. In addition, investigation of genetic effects in partial organ irradiation experiments has demonstrated out-of-field effects.

When irradiated and non-irradiated male mouse bone marrow cells (distinguishable by specific cytogenetic markers) were transplanted into female recipients, chromosomal instability was observed in the descendants of the non-irradiated cells. With relevance to radiotherapy, a cytotoxic bystander effect produced by tumour cells labelled with 5-125iodo-2′-deoxyuridine (125IudR) was recently demonstrated.3

3. Bystander effects in areas of major interest in radiotherapy

Tissue responses may not relate directly to the cytotoxic effects of radiation. For example, although local control in tumours requires elimination of tumour clonogens, in some circumstances the vascular damage could be extensive, especially when irradiation is combined with biologics or chemotherapeutic drugs. Also, irradiation modifies the tumour–host relationship, including interactions with infiltrating cells, such as macrophages and lymphocytes, which have been shown to be able to both promote and inhibit tumour growth. Such bystander effects may influence the biological basis of radiation on tumours and normal tissue.

3.1. Cell cycle effects

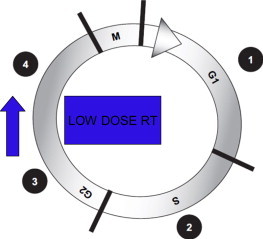

The importance of the cell cycle in radiosensitivity is well known. The advantage of radiotherapy is that cycling cells in the tumour are more radiosensitive than normal cells.4 Cells in the G2 and M phases are more sensitive to radiation. Some radiosensitizers act by blocking cells in the sensitive phases of the cell cycle, thus optimizing cell killing. The cell cycle phase can affect the ability of cells to produce or respond to bystander factors. Results reported in related fields suggest that it is likely that the G2 phase may be a candidate for involvement in bystander factor production or response (Fig. 1). Low-dose hypersensitivity is known to involve G2 cells. In contrast, P53, which acts in the G1 checkpoint, is not involved in bystander factor production, although it may be involved in apoptotic responses to the receipt of bystander signals. On the basis of the existing published data, it is tempting to suggest that bystander signal production is maximal in G2 phase.5

Fig. 1.

Radiation-sensitive checkpoints in the cell cycle. Low dose hypersensitivity is known to involve G2 cells. Bystander signal production may be maximal in G2.

3.2. Hypoxic conditions

There are reasons to suspect that hypoxic cells or those with compromised oxidative metabolism will have either reduced or absent cytotoxic bystander effects. A persistent state of oxidative stress is known to be induced in recipients of bystander medium and it has also been linked to the induction of genomic instability in both directly irradiated and bystander cells.

Many tumour cells lines that respire anaerobically do not display cytotoxic bystander effects. Many experiments using cell lines with a mitochondrial malfunction (glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency) do not demonstrate a cytotoxic bystander effect.

The key point to be considered for radiotherapy is that it is likely that normal well-oxygenated tissues will experience more cell death owing to bystander-related mechanisms than hypoxic, anaerobically respiring tumour cells. Considering this, it is not unreasonable to expect that new therapeutic approaches will improve the therapeutic ratio.

3.3. Fractionated radiotherapy

Most radiotherapy modalities include dose fractionation. The reasons for fractionation are well-known: if a single dose is delivered in multiple fractions, the total lethality to the normal tissue around the tumour will be lower. This can be demonstrated from split-dose recovery.

Fractionation dosing also allows multiple fields to be used, with the aim of sparing normal tissue. However, bystander effects may complicate this aim, as the multiple-field approach could increase the systemic burden of bystander factors.

Mothersill et al.6,7 showed that, although direct radiation, if fractionated, is less toxic in terms of total cell death attributable to the total dose, the medium harvested from each fraction is equally toxic. In those studies, the cumulative effect of exposure to medium from cells exposed to 2.5 Gy fractions was not less than the effect of medium from a 1.5 Gy dose, but was greater than the effect of medium from a single dose. These findings suggest that the direct effect of fractionated radiotherapy would be to spare the tissues receiving the direct dose, whereas the unirradiated cells that receive signals from nearby irradiated tissue would respond to each fraction as a unique dose. As a result, over a very large dose range, fractionating the dose does not result in any sparing effect for adjacent cells that receive bystander signals rather than direct doses. Again, this effect would be likely to negatively affect the therapeutic ratio. For this reason, it is essential to evaluate the effect of fractionating doses in an in vivo model.

Motherstill and colleagues have emphasized the importance of bystander effects to fractionated radiotherapy.5 In their study, growth medium harvested from cultured cells receiving fractionated irradiation resulted in greater cytotoxicity when added to bystander cells than growth medium harvested from cultures that received only a single dose of irradiation. This cell-killing effect of conditioned medium from irradiated cultures is contrasted with the split dose recovery observed in cultures directly exposed to fractionated irradiation. If bystander factors were produced in vivo, they may reduce the sparing effect observed in dose fractionation regimens. However, as those authors noted, the existence of such factors is likely to be patient, tissue, and lifestyle specific.

Once, approaches to clinical radiotherapy were based on basic radiobiology, which suggested that the therapeutic ratio could be improved by varying fractionation patterns. However, with the advent of molecular biology, the focus of radiobiology research shifted towards the characterization of cell cycle kinetics, DNA damage and repair processes, and mechanisms of cell death. This revolution led to new therapeutic strategies that targeted distinct biologic pathways or molecular events. Molecular biology also provided experimental tools that revitalized the field of low-dose radiobiology. As a result, the past few years have seen the characterization of several radiobiologic phenomena after low-dose irradiation. Important molecular discoveries have been made in genomic instability, adaptive response, bystander effects, and low-dose cell survival characterized by low-dose hyper-radiosensitivity.

The mechanistic characterization of delayed radiation effects will serve as a stimulus to develop better predictive biomathematical models of injury. It has long been recognized that the introduction of “time correction” algorithms is necessary to predict the severity of early radiation injuries using the linear quadratic formula. The increasing recognition that the rate and severity of early injuries may also affect delayed injury will stimulate a renewed effort—within the framework of cytocidal, functional and indirect effects—to incorporate the rate of biological dose accumulation as a distinct factor (from fraction size) in the construction of new biomathematical models.

3.4. Combined radio-chemotherapy

Radiation bystander effects induce genomic instability, although the mechanism driving this instability is still unknown. Gormana et al.8 assessed telomere length, bridge formations, mitochondrial membrane potential and levels of reactive oxygen species in bystander cells exposed to medium from irradiated and chemotherapy-treated explant tissues (using a human colon cancer explant model).

Several studies have shown that chemotherapy treatment also induces bystander effects that include apoptosis, an increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS), and cell differentiation.9 Although the mechanisms driving radiation and chemotherapy bystander effects are unclear, soluble signalling factors and cellular communication (via gap junctions and release of molecular messengers into the extracellular environment) may play a pivotal role.

Most studies of the bystander effect have been carried out with cell lines but few in vivo studies have been performed. Moreover, most research on the bystander effect has focused on ionizing radiation while only a few studies have evaluated alkylating agents. Asur et al.10 described chemically induced bystander effects in normal fully differentiated human cells and demonstrated the ability of genotoxic chemicals such as mitomycin C and phleomycin to induce a bystander effect in the context of ionizing radiation. Two previous studies have investigated a chemical-induced bystander effect. One study used primary cultures of mouse tumour cells11 and, in part due to the findings in that study, it is now widely accepted that tumour cells exhibit genomic instability. The other study used mouse embryonic stem cells that exhibit genomic instability following exposure to mitomycin C.12 The authors showed that those mouse stem cells exposed to mitomycin C were able to induce a homologous recombination in unexposed cells several generations after the initial exposure and, moreover, that these bystander cells in turn were able to propagate the damage to unexposed neighbouring cells. Demiden et al.13 demonstrated, both in vivo and in vitro, the ability of chloroethylnitrosurea to induce solid tumours to secrete soluble bystander factors. These soluble factors may either protect the bystander cells from death or help them to resist subsequent exposures to the agent. Alternatively, the factors might exhibit a cytotoxic effect resulting in cell death.

Awareness of radiation-induced bystander effects has led to a paradigm shift in radiobiology. While the ability of ionizing radiation to induce the secretion of media soluble factors has been documented,14,15 there is very little literature on the ability of other DNA damaging agents to do the same. However, as we have shown in this review, chemicals are also capable of inducing bystander effects through media-secreted factors. Until relatively recently, this phenomenon was previously thought to be limited to ionizing radiation. Evaluation of other stress-inducing agents might provide further insights into the mechanisms of these indirect effects.

3.5. Individual variation and genetics in toxicity of bystander factors

Genetic factors are clearly involved in the production and expression of bystander effects, and individual variation in factor toxicity has been shown.16 Mice that have different radiation responses and different radiogenic cancer susceptibility have been shown to have differences in bystander radiobiology. The link between genomic instability susceptibility and bystander cytotoxicity has been shown. Inflammatory-type responses after the exposure to ionizing radiation in vivo could be a mechanism for bystander induced instability.17

All this suggests a strong genetic component in the process, with bystander death-prone phenotypes appearing to be less prone to radiation-induced cancer. This is an important area, because it could help identify patients in whom induction of second cancers might be more likely.4 It might also help to identify patients most likely to benefit from radiotherapy and lead to the development of biomarkers of therapeutic effectiveness.

Genetic and phenotypic characterizations are potentially fruitful means of avoiding injury. In this respect, the proposed new formalism for categorization of radiation injury will boost our efforts to determine the genetic basis of radiosensitivity. To date, efforts have focused mainly on the genetics of cytocidal injury. However, although important DNA repair gene aberrations have been identified as causes for increased cellular sensitivity, their contribution to the overall burden of radiation injury is limited.18 The emphasis on functional injuries and (indirect) tissue responses as contributors to delayed tissue injury will certainly add momentum to the search for the genetic characterization and control of these mechanisms. Characterization of the functional and indirect mechanisms of injury, both at a cellular and subcellular level, is fundamental to this process. The nature of these radiation effects and the mechanisms by which they produce injury, will determine both the optimal approach and timing of therapeutic and prophylactic interventions.

3.6. Normal tissue

When radiation oncologists consider normal tissue effects, they take into consideration that one or more dose-limiting tissues will be in the path of the irradiation beam. However, the existence of radiation-induced bystander effects increases the likelihood of normal tissue effects. Thus, effects outside the treatment field have to be considered.

The concept of a biologic penumbra, which may be the whole person, cannot be excluded.

Fatigue after radiotherapy has become recognized as a real physical systemic effect of a radiation exposure. However, if all out-of-field side effects of radiotherapy and all systemic symptoms in irradiated cancer patients are included as bystander effects, this would dilute the scientific stringency of the concept, lead to confusion, and impede interpretation of research into the pathogenesis of normal tissue effects with regard to the volume effects and the role of intercellular signalling.

Advances in epithelial cell radiobiology, such as the recognition of the importance of bystander factors, indicate that these cells function as integrated units that communicate by highly sophisticated signalling mechanisms. Production of a signal by irradiated cells can lead to a response in unirradiated cells that is characteristic of apoptosis. The signal transmitted from irradiated to bystander cells may be mediated by intracellular and intercellular signal molecules (Table 2).

Table 2.

Signalling molecules involved in producing bystander effects.

| Intracellular signalling molecules |

| • (p53) Tumour protein 53 |

| • (CDKN1A, p21) Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A |

| • (MAPK) Mitogen-activated protein kinases |

| • (ATR) Ataxia telangiectasis and Rad3 related |

| • (DNA-PK) DNA-dependent protein kinase |

| • (PKC) Protein kinase C |

| • (ATM) Ataxia telangiectasia mutated protein |

| Intercellular signalling molecules |

| • (ROS) Reactive oxygen species |

| • (NO) Nitric oxide |

| • (5-HT serotonin) 5-hydroxytryptamine |

| • l-DOPA |

| • Glycine |

| • Nicotine |

| • Interleukin 8 |

| • (RNS) Reactive nitrogen species |

| • (TGFβ1) Cytokines |

| • TNFα |

Cellular function is controlled by spatial factors and requires factors secreted by other cell types such as stroma and endothelium. Given this complexity, we need radiobiology models that include and preserve these characteristics. Three-dimensional tissue culture models provide evidence for a pronounced bystander effect caused by a non-uniform distribution of radioactivity.

A major challenge and fertile area for present and future research is to determine the relative contribution of cytocidal, functional, and indirect radiation effects in a given setting. This will facilitate development of new tools to predict and monitor normal tissue radiation response and to provide a foundation for biologically based interventional strategies in the future.

The dose dependency of many of the processes will ensure that efforts to optimize the target volume, thereby limiting a normal tissue exposure, will continue to have a major role in minimizing injury.1

3.7. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT)

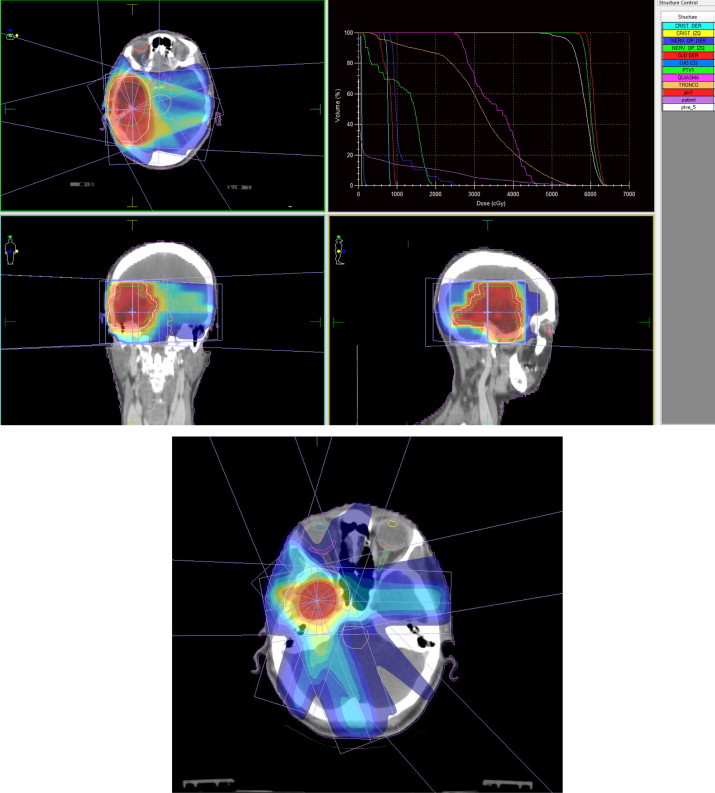

IMRT delivers highly conformal doses to the target volume using multiple fields, with the aim of reducing the dose and risk of complication to normal tissue. However, bystander effects may complicate this aim, as the multiple-field approach could increase the systemic burden of bystander factors. In IMRT, large areas adjacent to the high-dose target are commonly exposed to low-dose radiation (Fig. 2), and, consequently, non-targeted radiation effects appear to have a potentially important impact on radiotherapy outcomes.

Fig. 2.

IMRT: a large volume of the cells adjacent to a target treated with high dose IMRT are exposed to low-dose irradiation. The effects of this non-targeted radiation may have a potentially important impact on radiotherapy outcomes.

Published data19 show that out-of-field effects are important determinants of cell survival following exposure to modulated irradiation fields, with cellular communication between differentially irradiated cell population playing an important role. However, validation of these observations in additional cell models may facilitate the refinement of existing radiobiological models.20 These phenomena could be better understood if tests are developed to measure the possibility of producing bystander signals and response to these signals; similarly, such tests would better support planning and modulation of radiotherapy.21,22

Further studies to understand the fine equilibrium between pro- and anti-survival signalling pathways activated in response to irradiation and mutations or genetic polymorphisms that can influence this equilibrium are crucial and should be conducted in parallel with the development of radiotherapeutic techniques.

3.8. Protons

In recent years, the interest in the use of high-energy protons, as well as heavier particles, such as carbon ions, for cancer therapy has grown considerably due to the appealing physical properties of these particles.

As charged particles travel through tissue, they gradually decelerate and transfer energy to the tissue, resulting in molecular excitation and ionization. A sharp rise in energy transfer, termed the Bragg peak, take place near the end of the finite range of the particle. For protons, the radiation dose drops sharply to zero, resulting in no radiation beyond this point (exit dose).23 In contrast, dose deposition differs dramatically from X-ray irradiation, in which the peak dose is relatively superficial in tissue followed by a gradual fall-off in dose. As a result, the exit dose through normal tissue with X-ray irradiation can be substantial.

Proton treatments can often maintain target conformality while using a more limited number of fields, with a cumulative dose to normal tissue that is significantly lower than with X-rays. Active beam scanning technology and the application of intensity modulation methods can be used to increase the conformality of particle radiation therapy.16

The potentially lower dose to non-target structures and the consequent reduction in acute and late toxicity is the primary appeal of a charged particle therapy. This reduced toxicity may improve the tolerability of therapy, including regimens that incorporate chemotherapy. In younger patients, a low integral dose to normal tissue (protons reduce the total radiation dose to normal tissue by approximately 60%) may decrease the likelihood of growth retardation and second malignancies.24 The reduced toxicity may also allow for escalation of the total radiation dose. Bystander effects outside the primary treatment field are reduced with proton therapy.

4. Phenomena associated with radiation-induced bystander effects

There are several biological phenomena associated with radiation that can specifically explain bystander effects.

4.1. Adaptive response

When cells are pre-exposed to very low doses of ionizing radiation and subsequently exposed to a high dose, less genetic damage is found in the pre-exposed cells than in cells that were not pre-exposed. This effect is termed the adaptive response which is attributed to the induction of repair mechanisms by the low dose exposure.18,25 Direct exposure of cells to a low dose of ionizing radiation can induce a condition of enhanced radioresistance known as “radioadaptive response”. A radioadaptive bystander effect has been shown in unirradiated cells, in which transmissible factors are present in the supernatants of cells exposed to a low dose of α particle or low dose γ-rays. Such an effect was accompanied by an increase in the protein levels of AP-endonuclease in the bystander cells, but not in directly irradiated cells. This radioadaptive bystander effect was preceded by early decreases in cellular levels of TP53 protein and increase in intracellular ROS. An adaptive low dose of radiation, delivered several hours beforehand, cancelled out about half of the bystander effect. Other studies have shown that nitric oxide is one of the factors that mediates the bystander effect and induces radioresistance.26,27

4.2. Genomic instability

Radiation-induced genomic instability in somatic cells is a genome-wide process. It is characterized by an increased rate of cytogenetic abnormalities, mutations, gene amplifications, transformation, and cell death in the progeny of irradiated cells many generations after the initial insult. The characteristics of the instability depend on the test system being studied.14,28,29

4.3. Abscopal effects

Local anticancer radiotherapy may have not only delayed effects but also distant ones.18 It is sometimes asserted dogmatically that a local treatment cannot have systemic effects. However, treatment directed at a tumour at one site can in fact profoundly affect tumours at other locations in the body through an effect which R.J. Mole described more than 60 years ago30 as the abscopal effect. Thus, the abscopal effect can explain the clearance of non-irradiated tumours after localized radiation therapy, and the mechanism of action for this effect may be the activation of an antitumor immune response.

While the bystander effect affects unirradiated cells located near irradiated cells (i.e. neighbouring cells), the abscopal effect can take place in cells located much further away from the radiation field.31 Another difference is that the bystander effect is better understood as the radiobiological events arising from the radiation effect while the abscopal effect refers to clinical changes related to radiation effect.

These clinically observed effects appear within a patient's body, sometimes at significant distances from the irradiated tumour, and may be mediated by factors released by irradiated tumour cells and also by cells of the immune system.32

Cytotoxic effects observed in solid tumours located at distant sites from those targeted by radiation have also been reported in humans. Such abscopal effects can lead to the regression of a variety of tumours, and because of this, it was suggested that irradiation induces the release of cytokines into the circulation, which in turn mediate a systemic antitumor effect that may involve upregulation of immune activity.21

Postow et al. report a case of the abscopal effect in a patient with melanoma treated with ipilimumab and radiotherapy. Ipilimumab is a monoclonal antibody that inhibits an immunologic checkpoint on T cells, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4). Temporal associations were noted: tumour shrinkage with antibody responses to the cancer-testis antigen NY-ESO-1, changes in peripheral-blood immune cells, and increases in antibody responses to other antigens after radiotherapy.33

Okuma et al. report a case of a patient who showed an abscopal effect on lung metastases of hepatocellular carcinoma.34

In 2007, Takaya et al. described an abscopal effect in a case of toruliform para-aortic lymph node metastasis in a patient with advanced uterine cervical carcinoma. This patient was treated with external whole-pelvis and intra-cavitary irradiation to the primary pelvic lesion, successfully resulting in the disappearance of the lesion. Moreover, para-aortic lymph node metastases outside the irradiated field also spontaneously disappeared.35

Recent in vivo mouse experiments have shown that the p53 protein is a mediator of radiation-induced abscopal effect. The p53 protein was previously shown to have a role in the secretion of stress-induced growth inhibitors. The secretion of factors capable of inhibit abscopal/bystander effects when p53 wild-type tumours are irradiated would potentiate the effect of radiation in eradicating tumours.36,37

In this line, it would be interesting to mention the relationship between the systemic effects of radiation and the immune response, as has been pointed out by different authors. Demaria et al. demonstrate that the abscopal effect is in part immune mediated and that T cells are required to mediate distant tumour inhibition induced by radiation.38

It has become more and more obvious that X-irradiation causes distinct immunological effects ranging from anti-inflammatory activities if applied at low (<1 Gy) doses to harmful inflammatory side effects, radiation-induced immune modulation or induction of anti-tumour immune responses at higher doses. Moreover, experimental and clinical evidences indicate that these effects not only originate from direct nuclear damage but also include non-(DNA) targeted mechanisms including bystander, out of field distant bystander (abscopal) effects and genomic instability. The preclinical studies indicate that there is still an unsolved challenge to identify which single radiation dose and fractionation scheme is the most beneficial in the induction of systemic anti-tumour immunity alone or especially when combined with certain immune therapies. Rödel et al.39 report that normo- and hypofractionated irradiation of human colorectal tumour cells, but not a single high dose irradiation, creates tumour cell supernatans that activate dendritic cells (DCs).

Strong efforts should be made to identify the optimal combination of radiotherapy (including different fractionation concepts), chemotherapy, and immune therapy as well as their chronology for the induction of specific and systemic immune-mediated anti-tumour responses in preclinical animal model systems.

Immune response modifiers (IRM) have been defined as immunotherapy agents that mimic, augment, or require participation of the host immune system for optimal effectiveness. Although host T cells contribution to the optimal tumour response to radiation was demonstrated over three decades ago, it is only in the last decade that the underlying mechanisms has begun to be understood. Increasing number of publications testing new combinations of radiation and immunotherapy testify to the growing interest towards a new role of radiation as an immunological adjuvant. More exciting is the emerging evidence that radiation may indeed function as an IRM in patients, suggesting that it may be time to consider a paradigm shift in the use of radiotherapy.40

5. The bystander effect and radiation protection

The occurrence of a bystander effect in cell populations exposed to low fluences of high LET radiation such as α-particles, could have an impact on the estimation of risks of such exposure. This suggests that cell populations or tissues respond as a whole to radiation exposure and the response is not restricted to that of the individual traversed cells but involves the nontraversed cells also. This would imply that the modelling of dose–response relationships at low mean doses, based on the number of cells hit or even on the type of DNA damage they receive, may not be a valid approach.

Bystander effect studies indicate that nontraversed bystander cells exhibit similar genetic alterations and, hence, could contribute to the risk of such exposure. Significantly, the progeny of non-irradiated bystander cells have been shown to harbour a persistent genomic instability, which must result from initial interactions between the irradiated and non-irradiated bystander cells.

Non-targeted studies, including elucidation of the relationship between the bystander effect and propagation of genomic instability, along with epidemiological and other approaches, should contribute to the establishment of adequate environmental and occupational radiation protection standards.21,41

In terms of the significance of the bystander effect for radiation protection, the question arises as to whether this effect alters the nature of the dose response curve at low total doses and dose rates. The answer appears to be affirmative for acute exposure to very low fluences of high LET alpha particles when a significantly greater number of cells are at risk of inducing genetic changes (mutations, chromosomal aberrations) than those actually hit by an alpha particle. The dose response curve becomes concave upward at such low alpha particle fluences, indicating that the effect at low doses is greater than predicted by a simple linear extrapolation of the high dose curve. Interestingly, a much larger number of bystander cells are at risk of induction of mutations and chromosomal aberrations in cells deficient in DNA repair by the non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway. This finding, along with the evidence for an enhanced bystander effect in cells with other DNA repair defects, suggests the possibility that people with a reduced capacity to repair their DNA might show genetic susceptibility to the induction of cancer by very low fluences of alpha particles such as those arising from residential radon exposure.42–45

Unfortunately, we have very little data at present for the existence of the bystander response for low doses of low LET radiation such as gamma and X-rays, particularly at exposures below several mGy where fewer than 100% of the cells will be traversed by a photon. However, such information will soon be available with the development of low LET microbeam sources. Based on the experience with alpha radiation, this would be the region of the dose response curve where a non-linear dose response might occur due to the bystander effect.

6. Oxidative stress, DNA repair deficiency and bystander effect

A number of investigators have presented evidence for the upregulation of oxidative metabolism in bystander cells, suggesting that the biological effects in these cells may be a consequence of oxidative stress. Mutations induced in normal bystander cells are almost entirely point mutations, consistent with oxidative base damage, while those arising in irradiated cells are primary partial and total deletions. Cells deficient in the NHEJ repair pathway show a greatly increased bystander effect for mutations and chromosomal aberrations. The mutations induced in NHEJ-deficient bystander cells are primarily deletions, consistent with the unrepaired and misrepaired DNA lesions produced in these cells.46 Oxidative stress has also been associated with radiation-induced genomic instability in several studies.47,48

7. Microarray-based gene expression analysis and bystander effects

Microarray technology could provide a tool to identify the signalling pathways involved in the bystander effect. When the cells are exposed to ionizing radiation a significant proportion of cell nuclei are not traversed by ionizing radiation tracks. There is a potential significance of untraversed cells, as biological effects are seen in these bystander cells. Dependent cell survival involves a cell-cell interaction during or after irradiation that allows some cells to influence the survival of other cells.49–51

The pathways leading to the biological effects in bystander cells are different from those in directly irradiated cells. A comparison of the overall gene expression profile using DNA microarrays in irradiated versus bystander cells may provide information to understand the molecular mechanism underlying the bystander effect.22

8. Conclusion

Several studies have focused on the role of DNA damage and repair in the bystander response. At the molecular and cellular level, cell killing has been attributed to deposition of energy from the radiation in the DNA within the nucleus, with production of DNA double-strand breaks playing a central part. However, this DNA-centric model has been questioned. New insights into the mechanisms of these responses, coupled with technological advances in targeting of cells in experimental systems with microbeams, have led to a reassessment of the current model of how cells are killed by ionizing radiation. Overall, the evidence to date suggest that DNA damage is not the response trigger, but rather that DNA damage and repair proficiency play an important role in the downstream consequences in the bystander cells.52–54

Many unanswered questions about this phenomenon remain, including the following: the signal transmitted from irradiated to bystander cells (Table 2); the relationship between the bystander response and other non-targeted effects of radiation; the biological significance of the bystander effect; the beneficial effects associated with the bystander response; and the significance of the bystander effect for radiation protection.18,32,55

It is important that we understand the mechanisms underlying the bystander effect in order to more accurately assess radiation risk and to evaluate protocols for cancer radiotherapy.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Financial disclosure

None declared.

References

- 1.Konopacka M., Rogoliński J., Ślosarek K. Bystander effects induced by direct and scattered radiation generated during penetration of medium inside a water phantom. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother. 2011;16:256–261. doi: 10.1016/j.rpor.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brooks A.L., Retherford J.C., McClellan R.O. Effect of 239PuO2 particle number and size on the frequency and distribution of chromosome aberration in the liver of the Chinese hamster. Radiat Res. 1974;59:693–709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Watson G.E., Lorimore S.A., Macdonald D.A., Wright E.G. Chromosomal instability in unirradiated cells induced in vivo by a bystander effect of radiation. Cancer Res. 2000;60:5608–5611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Short S.C., Woodcock M., Marples B. Effects of cell cycle phase on low-dose hyper-radiosensitivity. Int J Radiat Biol. 2003;79:99–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marples B., Collis S.J. Low-dose hyper-radiosensitivity: past, present, and future. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;70:1310–1318. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.11.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mothersill C.E., Moriarty M.J., Seymour C.B. Radiotherapy and the potential exploitation of bystander effects. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;58:575–579. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2003.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mothersill C., Seymour C.B. Bystander and delayed effects after fractionated radiation exposure. Radiat Res. 2002;158:626–633. doi: 10.1667/0033-7587(2002)158[0626:badeaf]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gormana S., Tosettoa M., Lyngb F. Radiation and chemotherapy bystander effects induce early genomic instability events: telomere shortening and bridge formation coupled with mitochondrial dysfunction. Mutat Res. 2009;669:131–138. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alexandre J., Hu Y., Lu W., Pelicano H., Huang P. Novel action of paclitaxel against cancer cells: bystander effect mediated by reactive oxygen species. Cancer Res. 2007;67:3512–3517. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Asur R.S., Thomas R.A., Tucker J.D. Chemical induction of the bystander effect in normal human lymphoblastoid cells. Mutat Res. 2009;676:11–16. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2009.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang L., Snyder A.R., Morgan W.F. Radiation-induced genomic instability and its implications for radiation carcinogenesis. Oncogene. 2003;22:5848–5854. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rugo R.E., Almeida K.H., Hendricks C.A., Jonnalagadda V.S., Engelward B.P. Asingle acute exposure to a chemotherapeutic agent induces hyper-recombination in distantly descendant cells and in their neighbors. Oncogene. 2005;24:5016–5025. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Demidem A., Morvan D., Madelmont J.C. Bystander effects are induced by CENU treatment and associated with altered protein secretory activity of treated tumor cells: a relay for chemotherapy? Int J Cancer. 2006;119:992–1004. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grifalconi M., Celotti L., Mognato M. Bystander response inhumanlymphoblastoid TK6 cells. Mutat Res. 2007;625:102–111. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mitra A.K., Krishna M. Radiation-induced bystander effect: activation of signaling molecules in K562 erythroleukemia cells. J Cell Biochem. 2007;100:991–997. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mothersill C., Wright E.G., Rea D. Individual variation in the production of a bystander effect by radiation in normal human urothelium. Carcinogenesis. 2001;22:1465–1471. doi: 10.1093/carcin/22.9.1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lorimore S.A., Coates P.J., Scobie G.E. Inflammatory-type responses after exposure to ionising radiation in vivo: a mechanism for radiation-induced bystander effects? Oncogene. 2001;20:7085–7095. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mothersill C., Seymour C.B. Radiation-induced bystander effects and the DNA paradigm: an “out of field” perspective. Mutat Res. 2006;597:5–10. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2005.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karl T., Butterworth D., Conor K. Out-of field cell survival following exposure to intensity-modulated radiation fields. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;79:1516–1522. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.11.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hall E.J., Phil D. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy, protons and the risk of second cancers. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;65:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Butterworth K.T., McGarry C.K., Trainor C. Out-of-field cell survival following exposure to intensity-modulated radiation fields. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;79:1516–1522. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.11.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rzeszowska-Wolny J., Przybyszewski W.M., Widel M. Ionizing radiation-induced bystander effects, potential targets for modulation of radiotherapy. Eur J Pharmacol. 2009;625:156–164. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kramer M., Weyrather W.K., Scholz M. The increased biological effectiveness of heavy charged particles: from radiobiology to treatment planning. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2003;2:427. doi: 10.1177/153303460300200507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miralbell R., Lomax A., Cella L., Schneider U. Potential reduction of the incidence of radiation-induced second cancers by using proton beams in the treatment of pediatric tumors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;54:824. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)02982-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Azzam E.I., Little J.B. The radiation-induced bystander effect: evidence and significance. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2004;23:61–65. doi: 10.1191/0960327104ht418oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chaudhry M.A. Bystander effect: biological endpoints and microarray analysis. Mutat Res. 2006;597:98–112. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2005.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iyer R., Lehnert B.E. Alpha-particle-induced increases in the radioresistance of normal human bystander cells. Radiat Res. 2002;157:3–7. doi: 10.1667/0033-7587(2002)157[0003:apiiit]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wright E.G. Manifestations and mechanisms of non-targeted effects of ionizing radiation. Mutat Res. 2010;687:28–33. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2010.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mothersill C., Kadhim M.A., O’Reilly S. Dose- and time-response relationships for lethal mutations and chromosomal instability induced by ionizing radiation in an immortalized human keratinocyte cell line. Int J Radiat Biol. 2000;76:799–806. doi: 10.1080/09553000050028959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mole R.J. Whole body irradiation-radiobiology or medicine? Br J Radiol. 1953;26:234–241. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-26-305-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stamell E.F., Wolchok J.D., Gnjatic S., Lee N.Y., Brownell I. The abscopal effect associated with a systemic anti-melanoma immune response. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;85:293–295. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaminski J.M., Shinohara E., Summers J.B., Niermann K.J., Morimoto A., Brousal J. The controversial abscopal effect. Cancer Treat Rev. 2005;31:159–172. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Postow M.A., Callahan M.K., Barker C.A. Immunologic correlates of the abscopal effect in a patient with melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:925–931. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1112824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Okuma K., Yamashita H., Niibe Y., Hayakawa K., Nakagawa K. Abscopal effect of radiation on lung metastases of hepatocellular carcinoma: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2011;5:111. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-5-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takaya M., Niibe Y., Tsunoda S. Abscopal effect of radiation on toruliform para-aortic lymph node metastases of advanced uterine cervical carcinoma—a case report. Anticancer Res. 2007;27(January–February (1B)):499–503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Camphausen K., Moses M.A., Menard C. Radiation abscopal antitumor effect is mediated through p53. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1990–1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Komarova E.A., Diatchenko L., Rokhlin O.W. Stress-induced secretion of growth inhibitors: a novel tumor suppressor function of p53. Oncogene. 1998;17:1089–1096. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Demaria S., Ng B., Devitt M.-L. Ionizing radiation inhibition of distant untreated tumors (abscopal effect) is immune mediated. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;58:862–870. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2003.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rödel F., Frey B., Multhoff G., Gaipl U. Contribution of the immune system to bystander and non-targeted effects of ionizing radiation. Cancer Lett. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.09.015. PMID: 24139966, pii: S0304-3835(13)00669-1 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Demaria S., Formenti S.C. Role of T lymphocytes in tumor response to radiotherapy. Front Oncol. 2012;2:95. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2012.00095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kadhim M.A., Macdonald D.A., Goodhead D.T. Transmission of chromosomal instability after plutonium alpha-particle irradiation. Nature. 1992;355:738–740. doi: 10.1038/355738a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nagasawa H., Huo L., Little J.B. Increased bystander mutagenic effect in DNA double-strand break repair-deficient mammalian cells. Int J Radiat Biol. 2003;79:35–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Little J.B. Cellular radiation effects and the bystander response. Mutat Res. 2006;597:113–118. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Little J.B., Nagasawa H., Li G.C., Chen D.J. Involvement of the nonhomologous end joining DNA repair pathway in the bystander effect for chromosomal aberrations. Radiat Res. 2003;159:262–267. doi: 10.1667/0033-7587(2003)159[0262:iotnej]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mothersill C., Seymour R.J., Seymour C.B. Bystander effects in repair-deficient cell lines. Radiat Res. 2004;161:256–263. doi: 10.1667/rr3136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ermakov A.V., Konkova M.S., Kostyuk S.V., Egolina N.A., Efremova L.V., Veiko N.N. Oxidative stress as a significant factor for development of an adaptive response in irradiated and nonirradiated human lymphocytes after inducing the bystander effect by low-dose X-radiation. Mutat Res. 2009;669:155–161. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Azzam E.I., deToledo S.M., Little J.B. Oxidative metabolism, gap junctions and the ionizing radiation-induced bystander effect. Oncogene. 2003;22:7050–7057. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Limoli C.L., Giedzinski E., Morgan W.F., Swarts S.G., Jones G.D., Hyun W. Persistent oxidative stress in chromosomally unstable cells. Cancer Res. 2003;63:3107–3111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cucinotta F.A., Dicello J.F., Nikjoo H., Cherubini R. Computational model of the modulation of gene expression following DNA damage. Radiat Protect Dosimetry. 2002;99:85–90. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.rpd.a006846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Amundson S.A., Bittner M., Chen Y., Trent J., Meltzer P., Fornace A.J., Jr. Fluorescent cDNA microarray hybridization reveals complexity and heterogeneity of cellular genotoxic stress responses. Oncogene. 1999;18:3666–3672. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fornace A.J., Jr., Amundson S.A., Do K.T., Meltzer P., Trent J., Bittner M. Stress-gene induction by low-dose gamma irradiation. Mil Med. 2002;167:13–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Prise K.M., Schettino G., Folkard M., Held K.D. New insights on cell death from radiation exposure. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6:520–528. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70246-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Burdak-Rothkamm S., Prise K.M. New molecular targets in radiotherapy: DNA damage signalling and repair in targeted and non-targeted cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 2009;625:151–155. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.09.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Prise K.M., Folkard M., Kuosaite V., Tartier L., Zyuzikov N., Shao C.H. What role for DNA damage and repair in the bystander response? Mutat Res. 2006;597:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2005.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Morgan W.F., Sowa M.B. Non-targeted bystander effects induced by ionizing radiation. Mutat Res. 2007;616:159–164. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2006.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]