Abstract

Background:

There is abundant evidence of the affordable, life-saving interventions effective at the local primary health care level in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). However, the understanding of how to deliver those interventions in diverse settings is limited. Primary healthcare services implementation research is needed to elucidate the contextual factors that can influence the outcomes of interventions, especially at the local level. US universities commonly collaborate with LMIC universities, communities, and health system partners for health services research but common barriers exist. Current challenges include the capacity to establish an ongoing presence in local settings in order to facilitate close collaboration and communication. The Peace Corps is an established development organization currently aligned with local health services in many LMICs and is well-positioned to facilitate research partnerships. This article explores the potential of a community–Peace Corps–academic partnership approach to conduct local primary healthcare services implementation research.

Discussion:

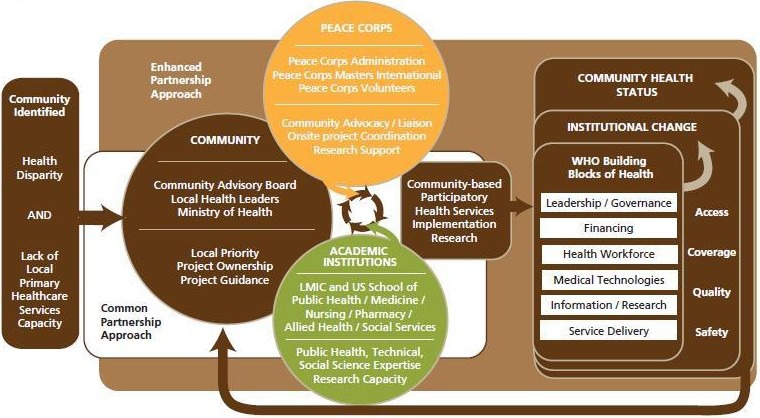

The Peace Corps is well positioned to offer insights into local contextual factors because volunteers work closely with local leaders, have extensive trust within local communities, and have an ongoing, constant, well-integrated presence. However, the Peace Corps does not routinely conduct primary healthcare services implementation research. Universities, within the United States and locally, could benefit from the established resources and trust of the Peace Corps to conduct health services implementation research to advance access to local health services and further the knowledge of real world application of local health services in a diversity of settings. The proposed partnership would consist of (1) a local community advisory board and local health system leaders, (2) Peace Corps volunteers, and (3) a US-LMIC academic institutional collaboration. Within the proposed partnership approach, the contributions of each partner are as follows: the local community and health system leadership guides the work in consideration of local priorities and context; the Peace Corps provides logistical support, community expertise, and local trust; and the academic institutions offer professional technical and public health educational and training resources and research support.

Conclusion:

The Peace Corps offers the opportunity to enhance a community-academic partnership in LMICs through community-level guidance, logistical assistance, and research support for community based participatory primary health-care services implementation research that addresses local primary healthcare priorities.

Key Words: Peace Corps, health services implementation research, global health

摘要

背景:大量证据表明,在低中收入 国家(Low and middle income countries, LMIC),费用合理的救生设施能够在地方性初级保健水平 发挥有效作用。然而,对于如何在 不同场合下提供这些设施的理解仍 有限。因此,需要初级保健服务实 施研究,尤其是在地方水平进行研 究,以阐明能够影响这些设施效果 的背景因素。美国大学通常与低中 收入国家的大学、社区和卫生系统 伙伴合作,进行医疗服务研究,但 普遍存在着障碍。目前的挑战包 括,建立为促进密切合作和沟通为 目的可持续存在的本地设置的能 力。和平队(Peace Corps)是个 已确立的发展组织,目前与许多 低中收入国家的地方性保健服务 密切合作,其所处位置非常有利 于建立研究伙伴关系。 本文探讨 了社区、和平队和学术界合作方 式对于开展地方性初级保健服务 实施研究的潜力。

讨论:和平队有可以深入了解地方 的背景因素的良好位置,因为和平 队志愿者与当地领导人密切合作, 取得当地社区的广泛信任,并且以 持续、稳定以及综合形式存在。 然而,和平队不会定期进行初级保 健服务实施研究。 在美国和其他 地方区域的大学可能受益于和平队 所建立的资源和信任,进行卫生服 务实施研究,以推进在多种多样的 设置中,利用地方性卫生服务,以 及增进地方性医疗卫生服务实际应 用的理解。本文拟议的伙伴关系将 包括(1)地方性社区咨询委员会 和地方卫生系统领导、(2)和平 队志愿者以及(3)美国低中收入 国家的学术机构合作。在拟议的伙 伴关系方式中,每一位合作伙伴的 贡献应为如下内容:地方性社区和 卫生系统的领导根据当地重点和具 体情况指导工作;和平队提供后勤 支援和社区专业知识以及建立当地 的信任;学术机构提供专业技术性 的、公共卫生教育和培训方面的资 源以及研究支持。

结论:和平队通过社区层面的指 导、后勤服务和研究支持,为了以 当地初级保健为重点的社区参与的 初级保健服务实施研究,提供提高 中低收入国家的社区-学术伙伴关 系的机会。

SINOPSIS

Antecedentes:

Existen muchas pruebas sobre intervenciones económicas que salvan vidas y su eficacia a nivel local en la atención primaria de países con ingresos bajos y medios (low- and middle-income countries, LMIC). Sin embargo, existe una limitación a la hora de entender cómo materializar esas intervenciones en diferentes entornos. Para esclarecer los factores contextuales que pueden influenciar en los resultados de las intervenciones, es necesario poner en marcha la investigación operativa en los servicios de atención sanitaria, sobre todo a nivel local. Con frecuencia, las universidades norteamericanas colaboran con las universidades de los países LMIC y con los asociados del sistema de salud respecto a la investigación en los servicios de salud, pero a todos ellos se les presentan obstáculos afines. Dentro de los desafíos actuales se encuentra la capacidad de crear un punto de referencia permanente en los entornos locales, con el objetivo de facilitar una colaboración y comunicación estrechas. El Cuerpo de Paz es una organización para el desarrollo consolidada, que en la actualidad colabora con los servicios locales de salud de muchos países LMIC y está bien posicionada para facilitar asociaciones de investigación. En este artículo se analiza el potencial desde el enfoque de una asociación comunitaria académica-Cuerpo de Paz a la hora de gestionar la investigación operativa en los servicios de atención sanitaria local.

Discusión:

El Cuerpo de Paz se encuentra muy bien posicionado para proporcionar información sobre los factores contextuales locales, puesto que los voluntarios trabajan en estrecha colaboración con los líderes locales, cuentan con una gran confianza dentro de las comunidades locales y su presencia es constante, continuada y está bien integrada. Sin embargo, el Cuerpo de Paz no gestiona la investigación operativa en los servicios de atención sanitaria de manera sistemática. Las universidades, tanto las norteamericanas como las locales, se podrían ver beneficiadas por la implementación de estos recursos y de la confianza del Cuerpo de Paz, para gestionar la investigación operativa de los servicios de atención sanitaria y, de esa forma, mejorar el acceso a los servicios sanitarios locales en distintos entornos. La asociación propuesta consiste en (1) una junta de asesores local comunitaria y unos líderes del sistema sanitario local, (2) voluntarios del Cuerpo de Paz y (3) una colaboración institucional y académica entre los Estados Unidos y los LMIC. Dentro del planteamiento de la asociación propuesta, las contribuciones de cada asociado consisten en: la comunidad local y el líder del sistema sanitario guiarán el trabajo teniendo en cuenta las prioridades y el contexto locales; el Cuerpo de Paz proporcionará apoyo logístico, su experiencia en la comunidad y la confianza local; por otra parte, las instituciones académicas ofrecerán recursos educativos y de formación en la salud pública, formación profesional técnica y apoyo a la investigación.

Conclusión:

El Cuerpo de Paz brinda la oportunidad de mejorar la asociación comunitario-académica en los LMIC a través de la orientación a nivel comunitario, la asistencia logística y el apoyo a la investigación dentro de un marco participativo de la investigación operativa de los servicios de atención sanitaria, que aborda las prioridades de la atención primaria de salud a nivel local.

INTRODUCTION

Health status in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) continues to significantly lag behind that of high income countries. This is reflected in the status reports of the Millennium Development Goals. Access to primary healthcare services that are responsive to the local context has been shown to significantly improve health status.1-9 Despite abundant evidence of the efficacy of affordable, life-saving interventions, LMIC adoption of evidence-based solutions to strengthen local primary healthcare services remains deficient.10-14 A significant barrier is that there is little understanding of how to deliver these interventions in diverse settings.15 Primary healthcare implementation research is needed to elucidate the contextual factors that can influence the outcomes of interventions, especially at the local level.7-9,15,16

The capacity of local health systems in LMICs is often not adequate to support basic primary healthcare services,17-24 much less to innovate, conduct critical quality improvement25-30 or disseminate research. To address this lack of capacity, health leaders often form partnerships with external agencies, governments, or universities. Global health partnerships can benefit health services development, improve retention and attrition rates, and impact service sustainability through health services implementation research.8,15,31-34

US universities commonly collaborate with LMIC universities for health services research. However, these partnerships often entail challenges. As an example, programmatic development through partnerships occurring at a centralized level may not reflect realities on the ground experienced by front-line workers. Because understanding the local context is central to implementing and improving primary healthcare services at the local level, implementation researchers that have significant field experience are more likely to foster successful collaborations and conduct meaningful research. Immersion in the local environment improves perspective, dialogue, negotiation, and collaborative problem-solving. However, the challenges for research personnel to establish a continuous presence in decentralized, local settings adversely impacts their ability to monitor process and develop a comprehensive understanding of context and systems.15

Figure 1.

Community–Peace Corps–Academic partnership as an enhanced approach.

The Peace Corps is a wide-reaching development organization that is positioned at the local level and aligned with health services in many LMICs. The Peace Corps understands the local context, being routinely engaged in community empowerment through participatory methods. However, the US Peace Corps, as an agency, currently lacks extensive research expertise. A partnership between a local LMIC community, the Peace Corps, and US-LMIC academic institutions using a participatory approach could enhance current models of community-academic collaborations with an ongoing local presence and increase capacity to advance implementation science.

THE US PEACE CORPS

The US Peace Corps is a well-established governmental organization that is aligned with local health services and knows the local context. The Peace Corps is active in 65 countries, and has more than 7000 volunteers in the field, 22% of whom are dedicated to health work. Peace Corps Volunteers (PCVs) in the health sector are not routinely engaged in health services strengthening, but, instead, focus on water, sanitation, or community health education including low-technical, though impactful, interventions such as condom use to prevent HIV/sexually transmitted infection (STI) transmission or bednet distribution to prevent malaria.

The Peace Corps was founded in 1961 by President John F. Kennedy. The program's purpose is “To promote world peace and friendship … which shall make available to interested countries and areas men and women of the United States qualified for service abroad and willing to serve, under conditions of hardship if necessary, to help the peoples of such countries and areas in meeting their needs for trained manpower.” The second and third goals of the Peace Corps, focusing on cultural exchange, have been, historically, the most recognized. However, the first goal, “To help the people of interested countries in meeting their need for trained men and women,” remains an area of significant opportunity for global health intervention.

The newly implemented Peace Corps Global Health Service Partnership program aims to build human resources capacity by placing US health professionals as faculty in teaching institutions for pre-service training.35-37 Volunteers, in their traditional roles or through this mechanism, however, do not routinely engage with local level primary healthcare services for implementation research and quality improvement. Traditional PCVs placed in decentralized areas do not have the technical medical expertise necessary to appropriately conduct quality improvement of clinical services and associated primary health care services implementation research without outside consultation. However, many PCVs do enter their service with advanced public health training. The Peace Corps Masters International (PCMI) Program (151 programs nationwide of which 23 are focused on public health or health policy) provides an opportunity for PCVs to gain field experience toward their public health degree. These PCVs can be well-positioned as field workers and research assistants to impact local health services if provided with proper technical support, research training, and a clearly defined role.

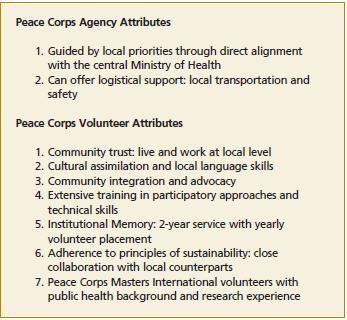

During their 2 years of service, PCVs earn significant trust in the communities where they live and work because they develop ongoing, longitudinal working relationships at the local level and retain significant institutional memory. PCVs are very well-trained in cultural assimilation and community integration and are fierce advocates for their communities. They develop excellent linguistic skills and master a mandatory level of training in participatory approaches and technical skills specific to their post and assignment. PCVs are trained extensively in the philosophy of sustainability and always work very closely with local counterparts. They know the local context in exhaustive detail including local community leadership. These attributes position PCVs as highly qualified field workers and research assistants. In addition, the Peace Corps as an agency could offer valuable support to global health partnerships focused on health services implementation research. At the country level, the Peace Corps is directly aligned with the central Ministry of Health. As such, Peace Corps work is guided by national and local priorities, and the agency regularly reports to the national level on its activities. The Peace Corps is also well-positioned to offer logistical support, including local transportation and safety support to partnering research teams.

The US Peace Corps is advantageously placed to support implementation research. A strategic goal of the Peace Corps is to “enhance the capacity of host country individuals, organizations, and communities to meet their skill needs.”38 Two performance goals are to (1) increase the effectiveness of skills transfer to host country individuals, organizations, and communities and (2) ensure the effectiveness of in-country programs.39 Peace Corps engagement in an enhanced global health partnership approach benefits communities and universities and is in line with the strategic direction of the Peace Corps. Over the course of the last few years, the Peace Corps has conducted a comprehensive agency assessment and reform effort, leading the development and implementation of initiatives to improve efficacy and efficiency across the organization including clearer strategic planning and metrics-based program evaluation—the first such endeavor since its founding in 1961. This has included instituting the new Office of Global Health and HIV. In addition, the Peace Corps is actively leveraging a new generation's passion and this era's technology while retaining the core competitive advantage of Peace Corps in international development: volunteers' deep understanding and connection with their host community. The resources and support that the Peace Corps could bring to an enhanced global health partnership approach benefits communities and universities and is in line with the strategic direction of the Peace Corps.

Health Services Implementation Research

Health services implementation research is the scientific study of the processes used for initiating, sustaining, and improving health services. With this approach, we can explore local, contextual factors affecting implementation as well as its outcomes. Through implementation research, one can learn about how to bring promising strategies to scale, how to support and promote the successful application of evidence-based interventions, and how to sustain these strategies over the long term. Implementation research is best conducted by those closest to the realities on the ground. The implication of real-world practitioners and the communities served by them is critical to its success, producing insights from the application of policy as it is affected by culture, environment, and other social determinants of health. Thus, factors that influence the practical application of theory are brought to life, and lessons learned can be applied to other programs in that setting or may give insights into the consideration of program development in other settings. Given the number of policy initiatives that are “shovel ready” yet continue to remain unapplied in many of the settings where they are most needed, advancing the science of health service implementation is needed.15

Figure 2.

Peace Corps attributes.

Based on evidence, the World Health Organization (WHO) and partnering organizations have developed many guides of recommended essential services in low-resource settings. These guides contain policy recommendations for the development of basic services within specific priority areas. Furthermore, many are accompanied by training manuals and service management reference guides to facilitate service assessment, implementation, and evaluation of programs. Notable among these are (1) Essential Interventions, Commodities, and Guidelines for Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, and Child Health,40 (2) The Package of Essential Noncommunicable Disease Interventions for Primary Health Care in Low-resource Settings,41 and (3) The WHO Mental Health policy and service guidance package,42 among others. There is abundant evidence of the efficacy of these and other affordable, life-saving interventions at the local primary healthcare level. However, despite extensive resources available in various languages, the uptake of this information, especially at the local level, remains low. This implies significant barriers in these settings and, likely, contextual factors at individual health districts, zones, or posts that are impacting the implementation of the suggested essential health services. Therefore, primary healthcare services at many decentralized levels in LMICs remain inadequate to provide the primary healthcare services access needed to significantly advance the Millennium Development Goals.

Partnerships Emphasizing Participation

Many US academic institutions are engaged in partnerships with LMIC communities, local health structures, or academic centers. The scope of the aims of projects implemented through these collaborative arrangements is broad, the methodologies diverse, and the reported successes of these existing relationships varied. Considering methodology, the use of community-based participatory research (CBPR)43,44 is frequently used and has been shown to improve delivery of primary healthcare services at the local level.45-48 It is well accepted that the use of a systematic participatory process strengthens global health partnerships.49 CBPR improves the delivery of primary healthcare services at the local level and can be used to carry out implementation research by engaging communities in the process of both service implementation and quality improvement.43-48 The outcome of CBPR depends on the quality of the partnership,50 and well-positioned partners improve synergy through leveraging combined influence. The “Partnership Synergy Framework” is an evaluation methodology developed for organizational partnerships addressing individual-level clinical services with broader, population-based strategies.51-53 In consideration of the aforementioned barriers to implementation research in LMICs through traditional university-community partnerships, the inclusion of the Peace Corps in a global health partnership could improve synergy by facilitating a community-centered approach that results in sustainable impact.

THE PROPOSED PARTNERSHIP APPROACH

The proposed community–Peace Corps–academic partnership, the Global Community Health Partnership (GCHP) approach utilizes CBPR methodology and operates with the premise that in order to sustainably address global health and adequately reduce disparity, solutions should originate and be developed, primarily, with community guidance, through (or with the strengthening of) existing health systems, and with the use of appropriate technology. The inclusion of the Peace Corps as a liaison partner in a global health partnership could facilitate a community-centered approach that emphasizes local priorities leading to a more equitable partnership. The Peace Corps is well-positioned to make priority setting more transparent and community responsiveness more comprehensive. The potential role of global health partnerships in addressing the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) is considerable, and through the creative leveraging of existing resources, the proposed community–Peace Corps–academic partnership approach could ultimately be impactful to the MDGs. The support that the Peace Corps could provide may be invaluable to academic institutions, both US and LMIC, interested in health services implementation research at decentralized, local levels.

The proposed partnership approach links (1) LMIC community members and local healthcare providers to (2) US and LMIC university faculty through the assistance of (3) the Peace Corps. The approach incorporates CBPR, empowering the community to set priorities and guide the implementation of the research. The Peace Corps facilitates the partnership by liaising between the community and the academic partners and offering community expertise, cultural guidance, onsite project coordination, and community advocacy. The universities offer professional technical and public health training resources and evaluation support. Partnership project planning meetings occur longitudinally through distance communication and document sharing. Community Advisory Board (CAB) meetings, focus groups, data collection, policy discussions, and technical trainings occur primarily during biannual university site visits. The participatory partnership and CAB meetings guide the health service adaptation, implementation, quality improvement, and the evaluation. The outcome of a partnership is a sustainable health service, trained healthcare providers, service guidelines directed at a locally prioritized health issue, and health service implementation research using mixed methods to evaluate the process and impact of the health service. The expansion of a community–Peace Corps–academic approach would foster the development of global health partnerships that (1) consistently use participatory approaches to address the need of sustainable community health systems in low-resource communities and (2) focus on primary healthcare services implementation research.

PRELIMINARY SUCCESS

This proposed partnership approach has been piloted with the Kedougou, Senegal regional Ministry of Health office, Peace Corps Senegal, and the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) since 2010.54-57 The Health Region of Kedougou is located in the southeastern part of Senegal with a population of 143 000 inhabitants and comprises 26 health posts, two health centers, and the regional hospital. WHO estimates that more than 250 000 cervical cancer deaths occur yearly, and more than 80% of cases occur in LMICs.58,59 In Senegal, access to cervical cancer preventive services (a locally identified priority) is limited in rural areas, though it is the most frequent cancer among Senegalese women.60 This partnership, through 2014, while working with six generations of PCVs (18 total) has implemented regional-level cervical cancer prevention clinical guidelines outlining a service accessible to an estimated 10,000 women in the target population (women aged 30-50 years); introduced the EngenderHealth-developed Client Oriented Provider Efficient (COPE) cervical cancer quality improvement process61,62 (which uses a clients' rights and providers' needs framework63); trained 60 health workers in the evidence-based and cost-effective screen and treat technique of visual inspection of the cervix with acetic acid (VIA)64,65 through the training of trainers approach; established access to cryotherapy equipment; trained one physician to conduct cryotherapy66-68 for the treatment of precancers; and conducted a region-wide prevalence study of cervical dysplasia using VIA.

The partnership approach has also been piloted with the Jimma and Bonga communities, Ethiopia, Jimma University School of Medicine, Peace Corps Ethiopia, and Northwestern University since 201169 and is in the early phases of development in Gaymate, Dominican Republic, in collaboration with Peace Corps Dominican Republic. The Ethiopia project addressed obstetrical emergencies by implementing the Advanced Life Support for Obstetrics (ALSO) course in this rural health region. This partnership approach has shown significant preliminary success and promise for expansion to a generalizable model that can be implemented across multiple Peace Corps posts through formalized relationships with individual US-LMIC University collaborations.

DISCUSSION

This partnership model addresses a specific and identified gap that lies between the abundant existence of evidence-based solutions to strengthen health services and the paucity of application of these service policies into the local context in many LMIC community health systems. The recommended partnership approach, drawing on the strengths of existing institutions, would maximize impact relative to cost while providing the strategic resources and valuable varying perspectives critical to implementation science. Through our experiences piloting this approach, and anticipated in future applications, we have encountered many of the inherent obstacles and challenges of research through a global health partnership. As discussed, this innovative partnership approach addresses some of these challenges. However, continued experience through iterative application will be required to identify and address other questions. While we have demonstrated limited success, we cannot be certain that these outcomes and the participation of the individuals within these partnerships are representative of other communities, Peace Corps posts, or academic centers. The approach does rely heavily on the support of the Peace Corps Country Director who, through a decentralized institution, is provided with significant autonomy to best manage post operations in a way that is most appropriate for the local priorities and context. With this consideration, it is likely that in the short-term this partnership approach may not be a natural fit for some posts. However, Peace Corps Senegal is well structured to support this type of relationship, and other posts are moving in that direction.

In Senegal, the post has developed a system of localized management, dividing the country into 25 work zones, in which volunteers develop strategic plans, including partner collaboration, for their zones. This approach enables longer-term relations with partners that are supported by entire work zones over multiple years, rather than just individual volunteers. This approach has been documented and shared with Peace Corps posts around the world and is being adopted in several countries. Additionally, there are currently 23 US academic programs training PCMI public health students, and these students are being posted in Peace Corps posts globally. These crème de la crème PCVs and their hosting Peace Corps posts are the face of “The New Peace Corps.”70 They are evidence that this timeless organization is adapting to advancing technologies, a profound worldview of its volunteers, and a renewed focus on impact through community development. The Peace Corps is well-positioned to make this transformation, and given its history and experience integrating volunteers into communities, it offers significant value to academic centers and international organizations that reciprocate guidance on technological solutions and research methodologies for continuous quality improvement. This local positioning and trust may also help partnered outside institutions to work efficiently within the local milieu, from identification of the best community partners to guidance on ethical, practical, and honest approaches in the accounting considerations of international projects—an often sticky point. This partnership approach is being discussed both at the agency-wide and Africa regional levels. Our limited success to date is encouraging for reshaping and ameliorating the presence and role of the Peace Corps in global health partnerships and health services implementation research.

NEXT STEPS

A rigorous evaluation of this partnership approach is needed to illustrate its impact and study the partnership process in multiple contexts. Due to the considerable existing capacity of the Peace Corps and current presence in many countries, there is significant opportunity for generalizing this partnership approach and applying it to multiple settings. It is anticipated that with repeated application of the partnership approach in various settings, barriers and challenges will be encountered and lessons in its application will be learned. As the partnership approach is applied in new locations, it will be important to initiate a consensus process to formalize the partnership model, clarify the specific roles of each partner, and document a universal process to achieve the stated objectives of the partnership approach. As the approach is applied in more settings there could be considerable value realized in the field of health services implementation science. Through parallel applications in multiple sites, we will be able to easily and consistently compare and contrast the process and impact of primary healthcare services implementation and quality improvement in multiple locations and various contexts. This will dramatically assist with advancing the knowledge of how to implement primary healthcare services at the local level in LMICs.

CONCLUSIONS

The proposed global health partnership approach involving local communities, the US Peace Corps, and academic centers generates community-based strategies through participatory approaches to increase access to primary healthcare services and improve the quality of health services in LMICs. By conducting health services implementation research through this innovative partnership, the science underlying the implementation and support of primary healthcare services in low-resource settings could be significantly impacted given the strategic positioning and existing resources of the Peace Corps. Showing promise for generalizability, this approach may improve a notable gap in community access to a broad range of primary healthcare services in LMICs and has broad applicability in theme to the approximately 3500 local LMIC communities where the Peace Corps is working globally.

Disclosures The authors completed the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Conflicts of Interest and had no conflicts to disclose.

Contributor Information

Andrew Dykens, University of Illinois at Chicago (Dr Dykens), United States.

Chris Hedrick, Peace Corps, Senegal (Mr Hendrick), Senegal.

Youssoupha Ndiaye, Sedhiou Region Health District, Senegal (Dr Ndiaye), Senegal.

Annē Linn, Peace Corps, Senegal (Dr Linn), Senegal.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kruk ME, Porignon D, Rockers PC, Van Lerberghe W.The contribution of primary care to health and health systems in low- and middle-income countries: a critical review of major primary care initiatives. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70(6):904–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Starfield B.Toward international primary care reform. CMAJ. 2009;180(11):1091–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J.Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83(3):457–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Starfield B.Primary care and health. A cross-national comparison. JAMA. 1991;266(16):2268–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beasley JW, Starfield B, van Weel C, Rosser WW, Haq CL.Global health and primary care research. J Am Board Fam Med. 2007;20(6):518–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Starfield B.Global health, equity, and primary care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2007;20(6):511–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wallerstein N.Empowerment to reduce health disparities. Scand J Public Health Suppl. 2002;59:72–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dieleman M, Shaw DM, Zwanikken P.Improving the implementation of health workforce policies through governance: a review of case studies. Hum Resour Health. 2011;9:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gonzalez-Block MA.Health policy and systems research agendas in developing countries. Health Res Policy Syst. 2004;2:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Lerberghe W, Evans T, Rasanathan K, Mechbal A, Organization WH, Lerberghe WV.The world health report 2008: primary health care: now more than ever. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Starfield B.Primary care: balancing health needs, services, and technology. New York: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Merson M, Black RE, Mills A.Global health. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Publishers; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ackerly DC, Udayakumar K, Taber R, Merson MH, Dzau VJ.Perspective: global medicine: opportunities and challenges for academic health science systems. Acad Med. 2011;86(9):1093–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koplan JP, Bond TC, Merson MHet al. Towards a common definition of global health. Lancet. 2009;373(9679):1993–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peters D, Tran N, Adam T.Implementation research in health. A practical guide http://who.int/alliance-hpsr/alliancehpsr_irpguide.pdf AccessedJuly24, 2014.

- 16.Simonds VW, Wallerstein N, Duran B, Villegas M.Community-based participatory research: its role in future cancer research and public health practice. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10:E78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Howze E, Auld M, Woodhouse L, Gershick J, Livingood W.Building health promotion capacity in developing countries: strategies from 60 years of experience in the United States. Health Educ Behav. 2009;36(3):464–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen L, Evans D, Evans Tet al. The world health report 2006: working together for health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization. Increasing access to health workers in remote and rural areas through improved retention. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moszynski P.One billion people are affected by global shortage of health-care workers. BMJ. 2011;342:d696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akl EA, Maroun N, Major Set al. Why are you draining your brain? Factors underlying decisions of graduating Lebanese medical students to migrate. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64(6):1278–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Black R, Crush J, Peberdy Set al. Migration and development in Africa. Institute for Democracy in; South Africa; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen L, Evans T, Anand Set al. Human resources for health: overcoming the crisis. Lancet. 2004;364(9449):1984–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Diallo K.Data on the migration of health-care workers: sources, uses, and challenges. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82(8):601–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ruelas E, Gómez-Dantés O, Leatherman S, Fortune T, Gay-Molina J.Strengthening the quality agenda in health care in low- and middle-income countries: questions to consider. Int J Qual Health Care. 2012;24(6):553–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bradley E, Yuan C.Quality of care in low- and middle-income settings: what next? Int J Qual Health Care. 2012;24(6):547–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Massoud M, Mensah-Abrampah N, Sax Set al. Charting the way forward to better quality health care: how do we get there and what are the next steps? Recommendations from the Salzburg Global Seminar on making health care better in low- and middle-income economies. Int J Qual Health Care. 2012;24(6):558–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leatherman S, Ferris T, Berwick D, Omaswa F, Crisp N.The role of quality improvement in strengthening health systems in developing countries. Int J Qual Health Care. 2010;22(4):237–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heiby J.The use of modern quality improvement approaches to strengthen African health systems: a 5-year agenda. Int J Qual Health Care. 2014;26(2):117–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leatherman S, Ferris TG, Berwick D, Omaswa F, Crisp N.The role of quality improvement in strengthening health systems in developing countries. Int J Qual Health Care. 2010;22(4):237–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gilson L, Mills A.Health sector reforms in sub-Saharan Africa: lessons of the last 10 years. Health Policy. 1995;32(1-3):215–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jeppsson A, Okuonzi SA.Vertical or holistic decentralization of the health sector? Experiences from Zambia and Uganda. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2000;15(4):273–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mills A.Health systems decentralization: concepts, issues, and country experience. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith B.The decentralization of health care in developing countries: organizational options. Public Admin Dev. 1997;17(4):399–412. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mullan F, Kerry VB.The Global Health Service Partnership: teaching for the world. Acad Med. 2014May13[Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kerry VB, Mullan F.Global Health Service Partnership: building health professional leadership. Lancet. 2014;383(9929):1688–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Global Health Service Partnership. Peace Corps. http://www.peacecorps.gov/volunteer/globalhealth/ AccessedJuly22, 2014.

- 38.The Peace Corps Strategic Plan fiscal years 2009–2014. http://www.peacecorps.gov/about/open/documents/.

- 39.The Peace Corps Performance Plan Fiscal Years 2012–2014. http://www.peacecorps.gov/about/open/documents/.

- 40.PMNCH. Essential interventions, commodities and guidelines for reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health. http://www.who.int/pmnch/knowledge/publications/201112_essential_interventions/en/ AccessedJuly24, 2014.

- 41.World Health Organization. Package of essential NCD interventions for primary health care: cancer, diabetes, heart disease and stroke, chronic respiratory disease. http://www.who.int/cardiovascular_diseases/publications/pen2010/en/ AccessedJuly24, 2014.

- 42.World Health Organization. The WHO mental health policy and service guidance package. http://www.who.int/mental_health/policy/essentialpackage1/en/ AccessedJuly24, 2014.

- 43.Minkler M, Wallerstein N.Introduction to community-based participatory research: new issues and emphases. : Minkler M, Wallerstein N.editors Community-based participatory research for health: from process to outcomes. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2008:544. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baum F, MacDougall C, Smith D.Participatory action research. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60(10):854–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Israel B, Schulz A, Parker E, Becker A.Community-based participatory research: policy recommendations for promoting a partnership approach in health research. Educ Health (Abingdon). 2001;14(2):182–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.O'Brien M, Whitaker R.The role of community-based participatory research to inform local health policy: a case study. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(12):1498–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mosavel M, Simon C, van Stade D, Buchbinder M.Community-based participatory research (CBPR) in South Africa: engaging multiple constituents to shape the research question. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(12):2577–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Slaymaker T, Christiansen K, Hemming I.Community-based approaches and service delivery: issues and options in difficult environments and partnerships. London Overseas Development Institute. http://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/3822.pdf AccessedJuly24, 2014.

- 49.Nuyens Y.Setting priorities for health research: lessons from low- and middle-income countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2007;85(4):319–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Andrews JO, Newman SD, Meadows O, Cox MJ, Bunting S.Partnership readiness for community-based participatory research. Health Educ Res. 2012;27(4):555–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lasker RD, Weiss ES.Creating partnership synergy: the critical role of community stakeholders. J Health Hum Serv Adm. 2003;26(1):119–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weiss ES, Anderson RM, Lasker RD.Making the most of collaboration: exploring the relationship between partnership synergy and partnership functioning. Health Educ Behav. 2002;29(6):683–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lasker RD, Weiss ES, Miller R.Partnership synergy: a practical framework for studying and strengthening the collaborative advantage. Milbank Q. 2001;79(2):179–205, III. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dykens J, NDiaye Y, Peters Ket al. Piloting a LMIC community, Peace Corps, university partnership model: a case study of cervical cancer preventive services implementation in Kedougou, Senegal through a Global Community Health Collaborative. Consortium of Universities for Global Health Conference; Washington, DC: March14-16, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ndiaye Y, Hedrick C, Brown C, Linn A, Dykens J.Peace Corps and the Saraya Health District: a local and global approach to public health in rural Senegal. Consortium of Universities for Global Health Conference; Washington, DC: March14-16, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Peters K, Dykens J.International health workforce development enhancement in Senegal: the peace care partnership model. 140th American Public Health Association Conference; San Francisco: October27-31, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Irwin T, Dykens J, Peters K, N'diaye Y, Grey P, Mumford M.Cervical cancer screening in Senegal: a novel collaboration with Peace Corps, university faculty and trainees. Academic Physicians in Gynecology and Obstetrics Annual Meeting; Orlando, Florida: March2-10, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Forman D, de Martel C, Lacey CJet al. Global burden of human papilloma-virus and related diseases. Vaccine. 2012;30Suppl 5:F12–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Comprehensive cervical cancer prevention and control: a healthier future for girls and women. http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/cancers/9789241505147/en/ AccessedJuly24, 2014.

- 60.Human papilloma virus and related cancers in Senegal. Summary report 2010. http://www.who.int/hpvcentre/statistics/dynamic/ico/country_pdf/SEN.pdf AccessedJuly24, 2014.

- 61.EngenderHealth. COPE handbook: a process for improving quality in health services. New York, NY: EngenderHealth; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 62.COPE for cervical cancer prevention services. http://www.engenderhealth.org/pubs/quality/cope.php

- 63.Huezo C, Diaz S.Quality of care in family planning: clients' rights and providers' needs. Adv Contracept. 1993;9(2):129–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sankaranarayanan R, Basu P, Wesley RSet al. Accuracy of visual screening for cervical neoplasia: results from an IARC multicentre study in India and Africa. Int J Cancer. 2004;110(6):907–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sankaranarayanan M, Chua LP, Ghista DN, Tan YS.Computational model of blood flow in the aorto-coronary bypass graft. Biomed Eng Online. 2005;4:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bradley J, Barone M, Mahé C, Lewis R, Luciani S.Delivering cervical cancer prevention services in low-resource settings. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2005;89Suppl 2:S21–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Blumenthal PD, Lauterbach M, Sellors JW, Sankaranarayanan R.Training for cervical cancer prevention programs in low-resource settings: focus on visual inspection with acetic acid and cryotherapy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2005;89Suppl 2:S30–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.World Health Organization. Comprehensive cervical cancer prevention and control—a healthier future for girls and women. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Panzer J, Dykens J, Wright Ket al. Implementing the Advanced Life Savings in Obstetrics (ALSO) course in Ethiopia in partnership with a local community utilizing the Peace Care model. Consortium of Universities for Global Health Conference; Washington, DC: March14-16, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hedrick C.The new Peace Corps. Yale Journal of International Affairs. http://yalejournal.org/2013/02/26/the-new-peace-corps/ AccessedJuly23, 2014.