Abstract

Several mouse pluripotent stem cell types have been established either from mouse blastocysts and epiblasts. Among these, embryonic stem cells (ESCs) are considered to represent a “naïve”, epiblast stem cells (EpiSCs) a “primed” pluripotent state. Although EpiSCs form derivatives of all three germ layers during in vitro differentiation, they rarely incorporate into the inner cell mass of blastocysts and rarely contribute to chimera formation following blastocyst injection. Here we successfully established homogeneous population of EpiSC lines with efficient chimera-forming capability using a medium containing fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-4. The expression levels of Rex1 and Nanog was very low although Oct4 level is comparable to ESCs. EpiSCs also expressed higher levels of epiblast markers, such as Cer1, Eomes, Fgf5, Sox17, and T, and further showed complete DNA methylation of Stella and Dppa5 promoters. However, the EpiSCs were clustered separately from E3 and T9 EpiSC lines and showed a completely different global gene expression pattern to ESCs. Furthermore, the EpiSCs were able to differentiate into all three germ layers in vitro and efficiently formed teratomas and chimeric embryos (21.4%) without germ-line contribution.

During the early developmental stages, pluripotent cells can be derived from the inner cell mass (ICM) and post-implantation epiblast cells. The pluripotent embryonic stem cells (ESCs) are derived from the ICM of blastocyst-stage embryos in vitro, whereas the pluripotent cells derived from post-implantation stage epiblasts, termed epiblast stem cells (EpiSCs) represent a more differentiated state than pluripotent ESCs. Therefore, EpiSCs have been referred to as “primed” pluripotent cells in order to distinguish them from the more potent “naïve” pluripotent ESCs1. However, EpiSCs do not efficiently contribute to the embryonic tissue after blastocyst injection, the efficiency being approximately 0.5% (2/385)1,2. Further, EpiSCs and naïve pluripotent stem cells differ in colony morphology1, global gene expression patterns, including micro RNAs3, X chromosome inactivation pattern4, and signaling pathways required for self-renewal5. Although mouse and human ESCs are both derived from the preimplantation embryos, human ESCs1,6 are distinct from mouse ESCs and share more common characteristics with EpiSCs with respect to their critical dependence on basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) and Activin/Nodal signaling for pluripotency and self-renewal2,7.

Self-renewal and maintenance of pluripotency in EpiSCs depends upon the extrinsic stimulation of Activin/Nodal pathway along with a parallel induction of bFGF signaling2. However, Activin/Nodal and bFGF do not support the generation of a pure population of EpiSCs; mixed populations were found to co-exist in a single culture dish1,8. In the mixed cell population, only Oct4-green fluorescence protein (GFP)-positive EpiSCs readily contributed to chimeras while GFP-negative EpiSCs did not, as they represented the late epiblast cells3,8. Taken together, these findings suggest that the Activin/Nodal signaling pathway might support the existence of two distinct cell populations. Therefore, we speculated that a homogenous population of EpiSCs could be maintained in presence of a factor supporting only the Oct4-GFP-positive cell population. So we attempt to characterize growth factors important for self-renewal in homogenous population of EpiSCs.

In the present study, we cultured EpiSCs in FGF4-supplemented medium in the absence of Activin and bFGF. FGF4 was proposed as an autocrine self-renewal promoting factor in human ESCs9. Feldman et al. also suggested that Fgf4 gene was important for supporting proliferation of ICM of mouse blastocyst and postimplantation embryos10. Oct4 and Sox2 regulate the expression of their target gene, FGF44,11, which is restrictedly expressed in the developing embryos and is believed to play a key role in embryonic survival and patterning2,5,12.

The results of the present study demonstrated that EpiSCs could self-renew in the presence of FGF4 without the exogenous stimulation of the Activin/Nodal signal. Therefore, our study suggests that FGF4 is an important factor for self-renewal and maintenance of homogenous EpiSC populations that express epiblast markers and efficiently form chimeras.

Results

Generation of a homogenous population of EpiSCs from embryonic day 5.5 (E5.5) and 6.5 (E6.5) epiblasts

Conventional EpiSC medium results in a heterologous population of EpiSCs8. In the present study, we used a transgene where GFP expression was controlled by Oct4 regulatory elements. The transgene represents a 10 kbp genomic fragment (genomic Oct4 fragment 18 kbp: GOF18) and contains crucial regulatory elements including a promoter and two upstream enhancers, called the distal enhancer (DE) and proximal enhancer (PE)13. Mouse EpiSCs containing the GOF18 GFP transgene express GFP because of the PE, whereas ESCs express GFP because of the DE. The conventional EpiSC medium containing Activin and bFGF does not result in a homogenous Oct4-positive EpiSC population8. To test if we could obtain a homogenous Oct4-positive EpiSC population, we employed a culture medium containing FGF4, which was replaced for Activin and bFGF. FGF4 was proposed as a factor capable of enhancing the self-renewal of human ESCs9. Fgf4, a target gene of Oct4 and Sox2, support the proliferation of ICM of mouse blastocyst and postimplantation embryos (E5.5 and 6.5)10. Fgf4-/- embryos degenerated shortly after uterine implantation, and Fgf4-/- blastocysts showed severely impaired proliferation of the ICM, which was completely rescued by adding recombinant FGF4 protein in the medium10. FGF4, together with LIF and steel factor, promotes the maintenance of pluripotency of embryonic germ cells (EGCs)14.

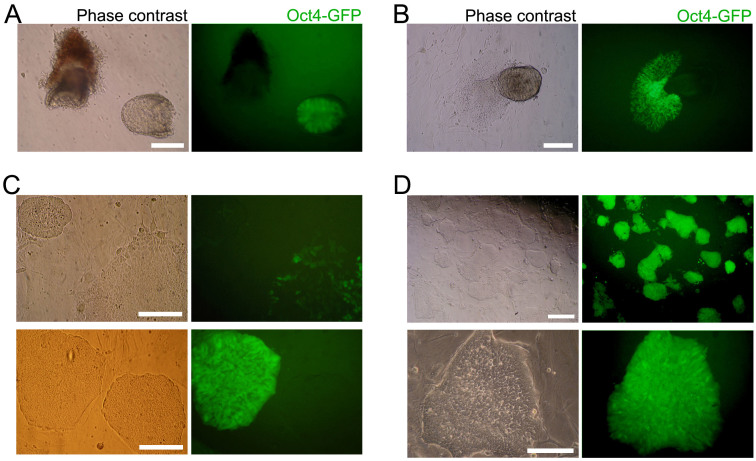

E5.5 and 6.5 embryos were recovered from GOF18 transgenic mice. GFP-positive epiblasts were dissected to separate the embryo/epiblast from the extraembryonic ectoderm (Fig. 1A and Supplementary material Fig. S1A). GFP-positive epiblasts were cultured in FGF4-supplemented medium (F4 medium). GFP-positive outgrowths spreading out from epiblasts were disaggregated and plated onto gelatin-coated dish containing F4 medium (Fig. 1B). GFP-positive EpiSCs were established after subsequent selection and culture. Until the third passage, most of the cells in the culture were GFP-negative and only a few cells and colonies were GFP-positive (Fig. 1C). However, a pure population of EpiSCs expressing GFP could be established only by repeated (triplicate) fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) purification at each passage (Fig. 1D and Supplementary material Fig. S1B). These EpiSCs, designated as F4-EpiSCs, were found to maintain homogenous GFP-positive colonies maintaining normal karyotype even after a long-term propagation (over 100 passages for about 6 months) (Supplementary material Fig. S1C). When the F4-EpiSCs were transferred into conventional EpiSC medium containing Activin and bFGF, GFP-negative cells appeared again and became heterogeneous (data not shown). These results indicate that F4 medium is supportive for the maintenance of homogenous Oct4-GFP-positive populations of EpiSCs. Of the two F4-EpiSC lines derived from E5.5 and E6.5 epiblasts, F4-EpiSCs from E6.5 epiblast were further analyzed.

Figure 1. Generation of EpiSCs from E6.5 epiblast.

(A) E6.5 embryos were recovered from GOF18 transgenic mice. GFP-positive epiblasts were used for generating EpiSCs. (B) GFP-positive outgrowths spreading out from the epiblasts. (C) Until the third passage, only a few cells and colonies in the culture were GFP-positive. (D) Pure populations of GFP-positive cells were established after three rounds of FACS. Scale bars are 100 μm.

F4-EpiSCs represent a primed pluripotent state

The GFP-positive F4-EpiSCs were positive for Oct4, but barely expressed Nanog as determined by immunofluorescence staining (Fig. 2A). When compared to ESCs, F4-EpiSCs were very weakly positive for alkaline phosphatase activity (Fig. 2B). We generated 3 lines of single-cell clones from F4-EpiSCs, which were subjected to real-time RT-PCR analysis. Real-time RT-PCR analysis revealed that the expression levels of mouse ESC-specific markers, Nanog and Rex1, were much lower in F4-EpiSCs when compared to those in ESCs (about 900- and 100-fold, respectively) (Fig. 2C). Our findings demonstrate that F4-EpiSCs are distinct from ESCs and are consistent with previous studies that demonstrated Oct4 expression both in naïve as well as primed pluripotent stem cells, whereas Nanog expression levels were significantly lower in EpiSCs (Fig. 2C)3,15,16.

Figure 2. Primed pluripotency—a unique feature of F4-EpiSCs.

(A) The GFP-positive F4-EpiSCs were stained positive for Oct4, but were weakly stained by anti-Nanog antibody. (B) F4-EpiSCs showed a very weak alkaline phosphatase activity, thus demonstrating their primed pluripotent state. (C) Representative real-time RT-PCR analysis data of F4-EpiSCs (from 3 lines of single-cell clones) and control ESCs using mouse ESC-specific and EpiSC markers. (D) DNA methylation patterns of the promoter regions of Stella and Dppa5. (E) Analysis of the Oct4 enhancer activity in ESCs and F4-EpiSCs. Relative luciferase activity was normalized to the activity of the empty vector. Scale bars are 100 μm.

Notably, F4-EpiSCs expressed higher levels of epiblast markers, such as Cer1, Eomes, Fgf5, Sox17, and T, when compared to ESCs (Fig. 2C). Both Stella and Dppa5 (markers for germ cells and naïve pluripotent stem cells) were unmethylated in ESCs, but hypermethylated in EpiSCs (Fig. 2D). As expected, the promoter regions of Stella and Dppa5, which were unmethylated in mouse ESCs, were hypermethylated in F4-EpiSCs. In addition, luciferase assay showed that F4-EpiSCs utilized epiblast-specific PE of Oct4 (Fig. 2E). Collectively, these data show that F4-EpiSCs are distinct from ESCs and represent a primed pluripotent state, which can be maintained in the presence of FGF4 without an exogenous stimulation of the Activin/Nodal pathway.

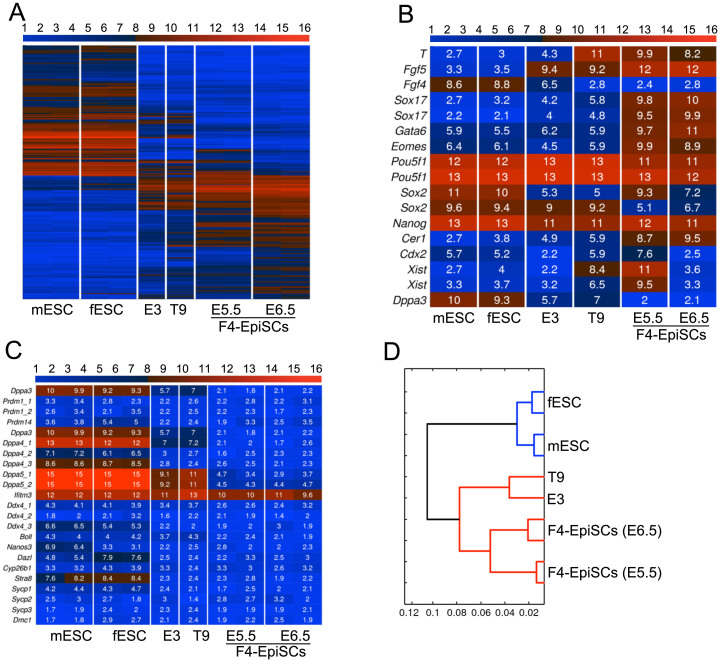

F4-EpiSCs can be distinguished from other EpiSC lines

We next investigated whether F4-EpiSCs (derived from E5.5 and E6.5) showed similar characteristics to other well-described EpiSC lines, such as the T9 and E3 cell lines5,12. F4-EpiSCs were found to be distinct from other EpiSCs lines (Fig. 3A) and expressed more EpiSC markers when compared to E3 and T9 lines (Fig. 3B). Similar to a previous observation in other EpiSC lines, F4-EpiSCs did not express germ cell and meiosis markers, except lfitm3 (Fragilis)17 (Fig. 3C). Therefore, F4-EpiSCs are most similar to the epiblast in their characteristics, and may represent epiblast cells in vivo, excluding germ cell precursors. Strikingly, F4-EpiSCs showed gene expression patterns that were distinctive compared to other EpiSC lines (Fig. 3D and Supplementary material Fig. S2). Therefore, our study suggests that F4-EpiSCs may be a novel cell type and could be easily distinguished from other EpiSC lines reported previously.

Figure 3. Gene expression profiles of F4-EpiSCs, ESCs, and other EpiSC lines.

(A) Heat map of the global gene expression profiles of ESCs, E3, T9 EpiSC lineS, and F4-EpiSCs. mESC and fESC denote, male ESC and female ESC, respectively. (B) Heat map of pluripotency- and EpiSC-related genes. (C) Heat map of germ cell and meiosis markers. (D) Hierarchical clustering shows that two F4-EpiSC lines clustered close together, but distinct from other EpiSC lines (E3 and T9).

Efficient chimera formation ability of F4-EpiSCs

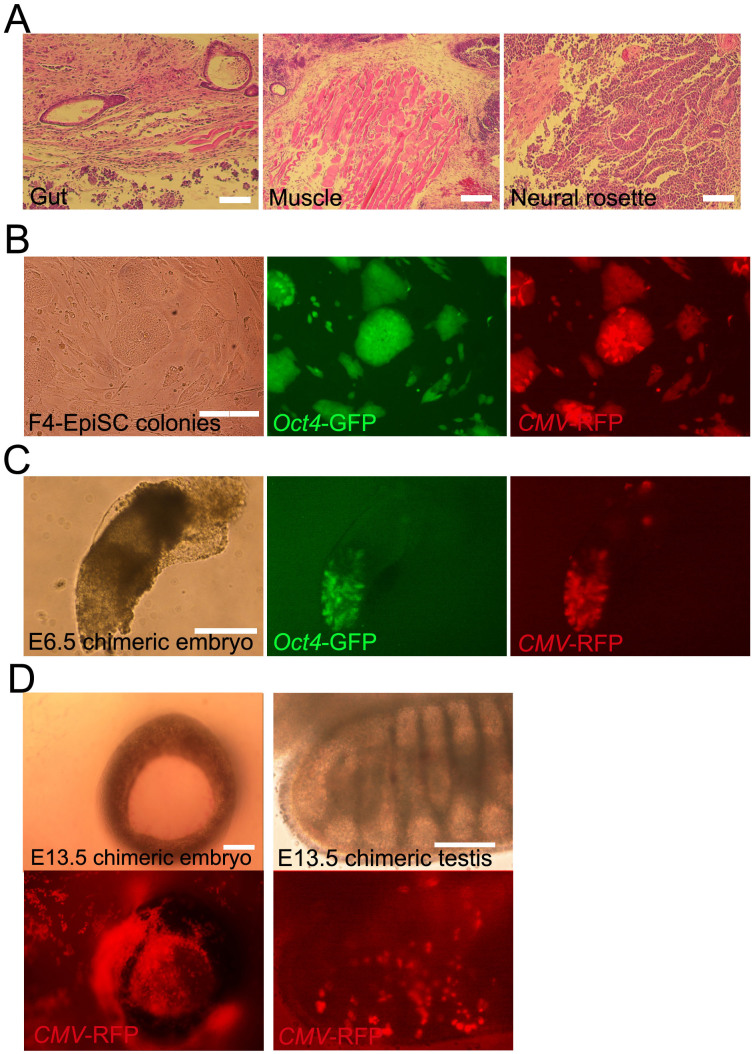

The observation that F4-EpiSCs resembled epiblast cells, which could differentiate to form all three germ layers during gastrulation, led us to investigate whether F4-EpiSCs showed a better differentiation potential than other EpiSC lines (which could hardly form chimeras). We therefore tested the multi-lineage differentiation potential of F4-EpiSCs (derived from E6.5) in vivo. First, F4-EpiSCs were transplanted subcutaneously into the dorsal flanks of immunodeficient (SCID) mice to assess their teratoma forming ability. It was observed that after 3 months of injection, teratomas containing gut, muscle, and neural tissues were formed (Fig. 4A). Next, we assessed the ability of F4-EpiSCs to form chimeras by injecting these cells into mouse blastocysts. Previous reports have suggested that EpiSCs, which represent primed pluripotent state, rarely if at all form chimera12,18. Chimera forming ability is, therefore, regarded as one of the hallmarks of “naïve” pluripotency19. However, we speculated that F4-EpiSCs might have a higher potential when compared to E3 and T9 EpiSC lines, since homogenous populations of F4-EpiSCs maintain Oct4-GFP over continuous subcultures and display more epiblast-like characteristics. To monitor the presence of F4-EpiSCs in chimeric embryos, we infected F4-EpiSCs with a lentivirus constitutively expressing the red fluorescence protein (RFP). The F4-EpiSCs, which harbored Oct4-GFP and CMV-RFP, expressed GFP and showed a ubiquitous expression of RFP in the presence of an active Oct4 (Fig. 4B). Initially, we observed chimerism in an early developmental stage, E6.5 embryo. Chimeric E6.5 embryos showed a high contribution of F4-EpiSCs in epiblast (both GFP- and RFP-positive) and a low contribution in extraembryonic tissues (only RFP-positive) (Fig. 4C). Chimerism could also be observed in E13.5 embryos (Fig. 4D). Notably, F4-EpiSCs contributed to somatic germ layers, including tissues of the testis, but not to the germ cell lineage, as Oct4-GFP was not active in RFP-positive cells. The efficiency of somatic chimerism, which showed RFP-positive cells in embryos, was approximately 21.4% (6/28). Thus, F4-EpiSCs exhibited a higher differentiation potential when compared to other previously reported EpiSC lines that could hardly contribute to chimerism2. These data indicate that F4-EpiSCs contribute to all three germ layers efficiently, except germ cells. This difference could be attributed to the low expression levels of Nanog in F4-EpiSCs. Nanog-deficient ESCs could self-renew and contribute to all three germ layer tissues in chimeras, but fail to contribute to germ cells. Therefore, Nanog is specifically required for germ cell formation20. Exclusive contribution to somatic lineage of F4-EpiSCs is the distinctive feature from other EpiSCs lines, including GFP-positive E3 cell line8.

Figure 4. Differentiation potential of F4-EpiSCs in vivo.

(A) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of teratomas derived from F4-EpiSCs. (B) F4-EpiSCS infected with lentivirus constitutively expressing the red fluorescence protein (RFP) transgene, expressed both RFP and GFP. (C) E6.5 chimeric embryos showing GFP and RFP dual-positive epiblasts and the low contribution to extraembryonic tissues (only RFP-positive). (D) Representative images of the chimeric embryos. E13.5 chimeric embryos, in which RFP-positive cells were detected in the face around an eye (left panel) and testis (right panel). Oct4-GFP was not detected in gonadal tissue in any of the six chimeric embryos. Scale bars are 100 μm.

Discussion

In the present study, we demonstrated that primed pluripotent EpiSCs have a higher differentiation potential than previously thought; when a homogenous population is propagated under suitable culture conditions. Further, we showed that homogenous populations of EpiSCs, which contribute significantly to chimeric embryos, could be maintained in FGF4-supplemented culture medium. In addition, F4-EpiSCs displayed distinctive gene expression patterns compared to other EpiSC lines (E3 and T9 lines). Notably, the F4-EpiSCs population seems to be somatic epiblast lineage that has the ability to differentiate into derivatives of all three somatic lineages, but not the germline, as they lacked both the expression of the germ cell markers and the contribution to germ cell lineage in chimera.

We derived F4-EpiSCs from E5.5 and 6.5 GOF18 transgenic embryos. E5.5 F4-EpiSCs were derived from developmentally earlier stage than E6.5 F4-EpiSCs, but the global gene expression pattern was very similar to E6.5 F4-EpiSCs. Striking differences were the levels of Cdx2 and Xist expression (Fig. 3B). E5.5 F4-EpiSCs express more trophoblast marker, Cdx2, than E6.5 F4-EpiSCs, although the expression level of other trophoblast marker Eomes was not different. Most of all, E5.5 EpiSCs were female cell line and E6.5 EpiSCs were male cell line. Thus there is no X chromosome inactivation in E6.5 F4-EpiSCs. On the other hand, Xist expression level of E5.5 F4-EpiSCs was very high (Fig 4B), indicating that inactive X chromosome is present as in somatic cells. Therefore, F4-EpiSCs should have the same X chromosome state as somatic cells; one of the two X chromosomes is inactive and the other X chromosome is active, otherwise two X chromosomes are all active if they are in a naïve pluripotent state. As the E6.5 F4-EpiSCs were male cells (XY), X chromosome in E6.5 F4-EpiSCs is always active. However, active X chromosome (Xa) of naïve pluripotent stem cells can be distinguishable from that of somatic cells. Xist gene region 1 (-381 to +74) is partially methylated in Xa of naïve pluripotent cells, but completely methylated in Xa of somatic cells21. Bisulfite DNA sequencing analysis showed that Xist gene region 1 of E6.5 F4-EpiSCs was completely methylated as in EpiSCs cultured in conventional EpiSC medium, indicating that Xa of F4-EpiSCs is not in naïve, but in primed pluripotent state (Supplementary material Fig. S3). Epiblasts around E6.5 comprise two different types of epiblast cells: primordial germ cell (PGC) precursors and somatic cell precursors that contribute to all the three germ layers. Various studies have reported that EpiSCs express germ cell markers. Germ cell marker expression is a characteristic of ESCs, and thus raises the possibility that the origin of ESCs could be germ cells22. However, our findings revealed that F4-EpiSCs did not express the germ cell markers, thus significantly differing from ESCs and other EpiSC lines. Taken together, these data indicate that the established F4-EpiSC line does not harbor the PGC precursor population, and thus represents a pure population of EpiSCs. Our results are further strengthened by previous observations that germ cell marker expressing EpiSCs represent a heterogeneous cell population, therefore could be mixed with naïve ESC-like cells. Hence, it is likely that the mixed ESC-like cells contribute to chimera after blastocyst injection. Considering this, a pure population of EpiSCs should not express germ cell markers and exclusively represent somatic epiblast cell population. Therefore, our study established that the population of EpiSCs comprises pure homogenous somatic stem cells.

Chimera forming ability has been regarded as a marker of “naïve” pluripotency19. However, the results of our study proved that primed pluripotent F4-EpiSCs were capable of generating chimera efficiently (without germline contribution) after blastocyst injection. Therefore, it is the germline contribution, and not the chimera forming ability, that represents the unique property of naïve pluripotent cells. Although Hayashi et al. advocated the germline contributing ability of a few cells in an EpiSCs culture, the cells retaining germline contribution could be naïve pluripotent cells in a heterogeneous cell population under a given culture condition23. Indeed, ESCs easily lose the ability to contribute to the germline in chimeras during culture22. Therefore, primed pluripotent cells reflect a less diverse differentiation potential (lack the germline competency) compared to naïve pluripotent cells.

Naïve pluripotency could be re-established in EpiSCs either by exposure to leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF), or by overexpressing pluripotency-related genes such as Klf4, Nr5a2, Nanog, or c-Myc15,18,24,25,26. In addition, induced EpiSCs (iEpiSCs) could be generated by using the same factors that were employed for iPSC generation, by just changing the culture medium that supports the differentiation of EpiSCs8. Therefore, stem cells retain some degree of plasticity, thus maintaining their identity, which in turn depends upon the signaling factors required for self-renewal, but not the origin of cells. On the other hand, a recent study by Di Stefano et al. reported FGF-dependent iPSCs, which display naïve ESC-like properties under EpiSC culture conditions27. They suggested that the naïve pluripotent state of iPSCs could be induced regardless of the growth factors present in culture. Collectively, these findings indicate that both culture condition as well as cell origin are important for establishing cellular identity.

In conclusion, in the present study, we successfully maintained pure homogenous populations of EpiSCs in FGF4-based culture medium. The F4-EpiSCs population exclusively comprises cells that possess the ability to differentiate into derivatives of all three somatic lineages, but not the germline. Therefore, the novel EpiSC culture system established in the present study may goal in a better understanding of the innate properties related to primed pluripotent stem cells.

Methods

The methods were carried out in accordance with the approved guidelines and all experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Max-Planck Institute for Molecular Biomedicine and Konkuk University.

Mice and Cell Culture

All mouse strains were either bred and housed at the mouse facility of the Max Planck Institute (MPI), Germany, or bought from Harlan or Jackson laboratories, CA, USA. Animal handling was in accordance with the MPI animal protection guidelines and the German animal protection laws. The derivation and characterization of GOF18 EpiSCs is described elsewhere5. In brief, E6.5 embryos (129/Sv female X C57BL6 and DBA/2 background GOF18+/+ male) were collected and transferred into mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) medium. For dissection, deciduas were removed with needle, and the extraembryonic ectoderm was separated from the epiblast by using hand-pulled glass pipettes. After washing with PBS, the epiblast was cultured on inactivated MEFs in FGF4-based medium28 with some modification : DMEM (GIBCO BRL Grand Island, NY, USA) containing 20% FBS, 2 mM glutamine, nonessential amino acids, and 25 ng/ml FGF4. EpiSC medium2: DMEM/F12 (GIBCO BRL) containing 20% knockout serum replacement (GIBCO BRL), 2 mM glutamine, nonessential amino acids, Activin A and 5 ng/ml bFGF. After initial culture on MEFs for three to five passages, EpiSC colonies were spilt and transferred onto dishes that had been pre-coated with gelatin for 30 min. For conditioning medium, irradiated MEFs were seeded at a density of 5 × 104 cells/cm2 and incubated in MEF medium for 96 h. The conditioned medium was filtered with a 0.45 µm filter, and FGF4 (25 ng/ml) or bFGF (5 ng/ml) was added. Cell clumps were replated on gelatin-coated dishes, and the medium was changed every 48 h. Animals were maintained and used for experimentation under the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Max-Planck Institute for Molecular Biomedicine and Konkuk University.

Blastocyst Injection

Blastocysts were collected from B6C3F1 mice. F4-EpiSCs were recovered by treatment with 0.25% trypsin EDTA, and placed in a drop of PBS under mineral oil. The blastocysts were placed in an adjacent drop of PBS containing 10% fetal bovine serum (v/v). Both GFP and RFP positive cells (n = 10–15) were loaded into an injection pipette and injected into B6C3F1 blastocysts by Piezo Micromanipulator (Prime-tech Ltd, Tsuchiura, Ibaragi, Japan). Each of the 8–15 injected blastocysts were transferred into the uteri of pseudopregnant ICR mice.

DNA Methylation Analysis

Genomic DNA was isolated from ESCs and EpiSCs. Subsequently, the DNA samples were subjected to bisulfite treatments using an EpiTect Bisulfite Kit (QIAGEN) following the manufacturer's protocol. PCR amplification of the promoter regions of Stella and Dppa5 was performed by employ the following primer sets and annealing temperatures:

Stella 1st sense 5′-TTTTTTTATTTTGTGATTAGGGTTG-3′;

Stella 1st antisense 5′-CTTCACCTAAACTACACCTTTAAAC-3′ (161 bp, 45°C);

Stella 2nd sense 5′-TTTGTTTTAGTTTTTTTGGAATTGG-3′;

Stella 2nd antisense 5′-CTTCACCTAAACTACACCTTTAAAC-3′ (116 bp, 55°C);

Dppa5 1st sense 5′-GGTTTGTTTTAGTTTTTTTAGGGGTATA-3′;

Dppa5 1st antisense 5′-CCACAACTCCAAATTCAAAAAAT-3′ (140 bp, 45°C);

Dppa5 2nd sense 5′-TTTAGTTTTTTTAGGGGTATAGTTTG-3′;

Dppa5 2nd antisense 5′-CTTCACCTAAACTACACCTTTAAAC-3′ (132 bp, 55°C).

The PCR products were then subcloned into the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega, Madison, WI), and were sequenced. The BiQ Analyzer software (Max Planck Society, Germany) was employed for the visualization and quantification of the bisulfite sequence data.

Flow Cytometry

For FACS sorting, hybrid cells were dissociated with 0.25% trypsin EDTA, neutralized with DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS, washed with PBS, and then filtered through a 40-mm nylon mesh to remove large cell clusters. The cells were resuspended in appropriate culture medium and aliquots of 5 × 106 cells/ml were transferred into polystyrene tubes. Subsequently, they were analyzed using FACSAria™ III cell sorter (BD Biosciences). Highly intense GFP-positive cells were isolated by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) using FACSDiVa™ software (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA).

Immunocytochemistry

For immunocytochemistry, F4-EpiSCs were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min at room temperature. After washing with PBS, cells were treated with PBS containing 10% normal goat serum and 0.03% Triton X-100 for 45 min at room temperature. Following incubation with primary antibodies: anti-Nanog (Cosmo Bio, REC-RCAB0002PF, 1:500) and anti-Oct4 (Abcam, ab19857, 1:500) overnight at 4°C, the cells were washed with PBS and then visualized after a 3-h incubation with appropriate fluorophore-labeled secondary antibodies (Alexa Fluor 488 or 568; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Specimens were analyzed using an Olympus Fluorescence microscope and images were acquired with a Zeiss Axiocam camera.

Luciferase Assay

For quantifying the relative Oct4 enhancer activity of F4-EpiSCs, an Oct4 upstream sequence ~2 kb (Oct4-2 kb) containing distal enhancer (DE) and proximal enhancer (PE), and either ΔDE, or ΔPE was cloned into pGL3 basic vector (Promega, USA). The Oct4 upstream sequence (~2 kb) containing DE and PE was derived from pOct4-GFP plasmid, which was digested and ligated to the KpnI/BglII sites of the pGL3 basic vector.

The pGL3-Oct4/ΔDE or pGL3-Oct4/ΔPE reporter constructs were prepared in two steps. First, a fragment of DE 5′or PE 5′ was PCR-amplified from pOct4-GFP plasmid using specific primer pairs, digested with KpnI and MluI restriction enzymes and cloned into pGL3 basic vector to obtain pGL3-DE 5′ or pGL3-PE 5′ plasmids, respectively. Subsequently, a fragment of DE 3′ or PE 3′ was PCR amplified from pOct4-GFP plasmid using primer pairs carrying MluI and BglII restriction sites, respectively. The amplified fragment was digested and ligated to MluI/BglII sites of either pGL3-DE 5′or pGL3-PE 5′ plasmids. The primers used were as follows: Oct4-up-5-KpnI ATATATGGTACCCTAGTTCTAAGAAGACTTGGGACTTCAGAC, Oct4-ATG-3′-BglII- ATATATAGATCTGGGGAAGGTGGGCACCCCGAGCCGGGGGCCT, DE del-3-MluI- ATATATACGCGTCCTGTCTGTATTCAATACCAACCT, DE del-5-MluI- ATATATACGCGTTCCTAGCCCTTCCTTAATCTGCTA, PE del-3-MluI- ATATATACGCGTCCCATTACTGGCCTGGTGCTTAGT, PE del-5-MluI- ATATATACGCGTCAGATATTTCTTCTCTCTACCCAC.

Luciferase assays were performed in MEF, ESCs, and F4-EpiSCs using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega, USA). For the reporter assay of Oct4 enhancer activity, pGL3-Oct4/ΔDE, or pGL3-Oct4/ΔPE vectors (for firefly luciferase activity) and pRL-TK vector (for Renilla luciferase activity) were transfected individually into MEF, ESCs, and F4-EpiSCs. After 48 h of transfection, growth medium was removed and cells were rinsed in 1× PBS. Subsequently, the cells were lysed using 1× passive lysis buffer (PLB) and incubated for 10 min at room temperature with shaking. The cell lysate was then transferred to 1.5 ml new tube and centrifuged at 10, 000 rpm for 5 min at 4°C. Ten microliters of the supernatant was transferred to a 96-well plate and then analyzed for luciferase expression by luminometry. Each experiment was performed in triplicate and the values obtained were recorded as relative light units (RLU).

Microarray Analysis

DNA-free RNA samples to be analyzed by microarrays were prepared using Qiagen RNeasy columns with on-column DNA digestion. Three hundred nanograms of total RNA per sample were used as input for the linear amplification protocol (Ambion, Austin, TX, http://www.ambion.com), which involved synthesis of T7-linked double-stranded cDNA and 12 h of in vitro transcription, incorporating biotin-labeled nucleotides. Purified and labeled cRNA was then hybridized for 18 h onto MouseRef-8 v2 gene expression BeadChips (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, http://www.illumina.com) following the manufacturer's instructions. After washing, the chips were stained with streptavidin-Cy3 (GE Healthcare, Chalfont St. Giles, UK, http://www.gehealthcare.com) and scanned using the iScan reader (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, USA) and accompanying software. Samples were exclusively hybridized as biological replicates.

The intensities for each bead were mapped to gene information using BeadStudio 3.2 (Illumina). Background correction was performed using the Affymetrix Robust Multi-array Analysis (RMA) background correction model, variance stabilization was performed using the log2 scaling, and gene expression normalization was calculated with the quantile method implemented in the lumi package of R-Bioconductor. Data post-processing and graphics were performed with in-house developed functions in Matlab.

Author Contributions

J.Y.J., J.T.D. and H.R.S. wrote the main manuscript text and design the concept of the experiment. J.Y.J., H.W.C., M.J.K., H.Z., N.T. and M.S. performed experiment and assembled data. K.S.J. performed data analysis. All authors reviewed the manuscript

Supplementary Material

Dataset 1

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Next Generation Bio-Green 21 Program funded by the Rural Development Administration (grant no. PJ00956202).

References

- Stadtfeld M. & Hochedlinger K. Induced pluripotency: history, mechanisms, and applications. Genes & Development 24, 2239–2263 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brons I. G. M. et al. Derivation of pluripotent epiblast stem cells from mammalian embryos. Nature 448, 191–195 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jouneau A. et al. Naive and primed murine pluripotent stem cells have distinct miRNA expression profiles. RNA 18, 253–264 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner R. L., Lyon M. F., Evans E. P. & Burtenshaw M. D. Clonal analysis of X-chromosome inactivation and the origin of the germ line in the mouse embryo. J Embryol Exp Morphol 88, 349–363 (1985). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greber B. et al. Conserved and Divergent Roles of FGF Signaling in Mouse Epiblast Stem Cells and Human Embryonic Stem Cells. Cell Stem Cell 6, 215–226 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson J. A. Embryonic Stem Cell Lines Derived from Human Blastocysts. Science 282, 1145–1147 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallier L. et al. Activin/Nodal signalling maintains pluripotency by controlling Nanog expression. Development 136, 1339–1349 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han D. W. et al. Epiblast stem cell subpopulations represent mouse embryos of distinct pregastrulation stages. Cell 143, 617–627 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayshar Y. et al. Fibroblast Growth Factor 4 and Its Novel Splice Isoform Have Opposing Effects on the Maintenance of Human Embryonic Stem Cell Self-Renewal. STEM CELLS 26, 767–774 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman B., Poueymirou W. & Papaioannou V. E. Requirement of FGF-4 for postimplantation mouse development. Science 267, 246–249 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodda D. J. Transcriptional Regulation of Nanog by OCT4 and SOX2. Journal of Biological Chemistry 280, 24731–24737 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- New cell lines from mouse epiblast share defining features with human embryonic stem cells. Nature 448, 196–199 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeom Y. I., Fuhrmann G., Ovitt C. E., Brehm A. & Ohbo K. Germline regulatory element of Oct-4 specific for the totipotent cycle of embryonal cells. Development 122, 881–894 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui Y., Zsebo K. & Hogan B. L. Derivation of pluripotential embryonic stem cells from murine primordial germ cells in culture. Cell 70, 841–847 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo G. et al. Klf4 reverts developmentally programmed restriction of ground state pluripotency. Development 136, 1063–1069 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillich A. et al. Epiblast Stem Cell-Based System Reveals Reprogramming Synergy of Germline Factors. Cell Stem Cell 10, 425–439 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka S. S., Yamaguchi Y. L., Tsoi B., Lickert H. & Tam P. P. L. IFITM/Mil/Fragilis Family Proteins IFITM1 and IFITM3 Play Distinct Roles in Mouse Primordial Germ Cell Homing and Repulsion. Developmental Cell 9, 745–756 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao S. et al. Epigenetic reversion of post-implantation epiblast to pluripotent embryonic stem cells. Nature 461, 1292–1295 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols J. & Smith A. Naive and Primed Pluripotent States. Cell Stem Cell 4, 487–492 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers I. et al. Nanog safeguards pluripotency and mediates germline development. Nature 450, 1230–1234 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do J. T. et al. Enhanced reprogramming of Xist by induced upregulation of Tsix and Dnmt3a. Stem Cells 26, 2821–2831 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwaka T. P. A germ cell origin of embryonic stem cells? Development 132, 227–233 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi Y. et al. BMP4 induction of trophoblast from mouse embryonic stem cells in defined culture conditions on laminin. In Vitro Cell.Dev.Biol.-Animal 46, 416–430 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J. et al. Stat3 Activation Is Limiting for Reprogramming to Ground State Pluripotency. Cell Stem Cell 7, 319–328 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo G. & SMITH A. A genome-wide screen in EpiSCs identifies Nr5a nuclear receptors as potent inducers of ground state pluripotency. Development 137, 3185–3192 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna J. et al. Direct cell reprogramming is a stochastic process amenable to acceleration. Nature 462, 595–601 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Stefano B. et al. An ES-Like Pluripotent State in FGF-Dependent Murine iPS cells. PLoS ONE 5, e16092 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka S. Promotion of Trophoblast Stem Cell Proliferation by FGF4. Science 282, 2072–2075 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Dataset 1