Summary

The use of Guglielmi Detachable Coil (GDC) for the endovascular treatment of intracerebral aneurysms is increasing, particularly in those aneurysms for which there is a high surgical morbidity and mortality. However; the long-term efficacy of GDC is not known. Until the natural history of GDC treatment is established long-term follow-up in this cohort of patients is required, of necessity involving repeated intraarterial angiography (IA DSA) with its known attendant risks and exposure to ionising radiation.

Three dimensional time-of-flight magnetic resonance angiography (3D TO F MR A) is now readily accepted as a non-invasive screening tool for familial aneurysmal disease and has been used as an alternative to IA DSA in the surgical management of aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage. MRA in patients treated with GDC is safe, imparts no radiation dose and provides acceptable image quality.

The aim of this study was to assess 3D TOP MRA source data, maximum intensity projection (MIP) and 3D isosurface reconstruction in comparison to IA DSA in the follow-up of 25 patients treated with GDC. Images were assessed for parent and branch artery flow, the presence of neck recurrence and aneurysm regrowth.

There was good correlation for all these features when 3D isosurface MRA and source data were compared with IA DSA. The correlation between MIP MRA and IA DSA was less robust. Additional confidence can be obtained by performing plain films of the skull to demonstrate change in coil ball configuration. MRA has the potential to replace IA DSA in the follow-up of GDC treated cerebral aneurysms.

Introduction

The role of endovascular treatment in the management of patients with intra-cranial aneurysms is increasing, particularly with the introduction of GDC1. The technique is increasingly accepted for those aneurysms for which there is potentially a high surgical morbidity and mortality, e.g. in the vertebrobasilar or carotido-ophthalmic territories. However, the durability of GDC is not known, particularly its effectiveness at preventing re-haemorrhage in the long-term1. For this reason meticulous surveillance of those patients treated with GDC is required, to monitor aneurysm recurrence and to re-treat with coil or surgical clip if appropriate. IA DSA has been considered the gold standard investigation for intra-cerebral aneurysmdisease but it is invasive and incurs exposure to ionising radiation for both patient and operator.

Three-dimensional TOF MRA is now readily accepted as a non-invasive screening tool for familial aneurysmal disease2 and has been used as an alternative to IA DSA in the surgical management of aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage3. MRA in those patients treated with GDC is safe, imparts no radiation dose and provides acceptable image quality4. For MRA to provide an acceptable alternative to IA DSA in the follow-up of these patients it must be able to consistently demonstrate parent and branch vessel patency, the presence of an aneurysm neck or remnant and residual flow within the interstices of a coil ball mesh. There must also be good correlation with conventional angiography for diagnostic credibility.

To investigate the hypothesis that MRA can replace IA DSA in the follow-up of this patient group we have produced comparative data by examining patients treated with GDC using both modalities.

Material and Methods

We performed MRA and IA DSA on 25 patients with 28 aneurysms treated by GDC as part of our routine follow-up protocol (see table 1). All patients presented with aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH) and were treated acutely. Both the follow-up MR examination and the IA DSA were performed on the same day.

Table 1.

GDC and aneurysm details

| Patient | Age / Sex | Aneurysm Location |

GDC (nos.) |

Interval between GDC and MRA (months) |

Residual neck | Residual flow in coils |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 46 / F | AComm | T18 (1) | 1 | Yes | No |

| 2 | 56 / F | RT PICA | T10 (1) | 6 | No | No |

| 3 | 49 / F | BT | T10 (4) | 5 | No | No |

| 4 | 51 / F | RT SCA | T10 (2) | 6 | No | No |

| 5 | 38 / F | BT | T18 (3) | 27 | No | No |

| 6 | 39 / F | AComm | T10 (2) | 6 | No | No |

| 7 | 50 / F | RT PICA | T10 (2) | 6 | Yes | No |

| 8 | 49 / F | AComm | T10 (4) | 6 | Yes | Yes |

| 9 | 41 / F | AComm BT |

T10 (1) T10 (2) |

15 15 |

Yes No |

Yes No |

| 10 | 33 / F | BT | T10 (3) | 6 | Yes | No |

| 11 | 59 / F | BT | T10 (5) | 6 | Yes | No |

| 12 | 41 / M | LTICA | T18 (5) | 10 | No | No |

| 13 | 74 / F | AComm | T10 (2) | 6 | Yes | Yes |

| 14 | 43 / F | BT RT ICA |

T10 (3) T10(4) |

6 6 |

Yes Yes |

No No |

| 15 | 34 / F | LT ICA | T18 (4) | 9 | Yes | Yes |

| 16 | 54 / F | RT ICA | T10 (4) | 8 | Yes | No |

| 17 | 61 / M | LT PICA | T10 (1) | 3 | Yes | Yes |

| 18 | 49 / F | BT | T10 (2) | 6 | Yes | Yes |

| 19 | 52 / F | LT ICA AComm |

T10 (3) T10 (2) |

6 6 |

No Yes |

No No |

| 20 | 40 / F | BT | T18 (4) | 17 | No | No |

| 21 | 40 / F | RT MCA | T18 (4) | 17 | Yes | No |

| 22 | 44 / F | RT ICA | T10 (5) | 7 | Yes | No |

| 23 | 32 / M | LT MCA | T10 (7) | 6 | Yes | Yes |

| 24 | 19 / M | RT ICA | T10 (2) | 6 | Yes | No |

| 25 | 49 / F | LT ICA | T18 (9) | 4 | Yes | Yes |

|

AComm = Anterior communicating artery; PICA = Poterior inferior cerebellar artery; BT = Basilar termination; SCA = Superior cere- bellar artery; MCA = Middle cerebral artery; ICA = Internal carotid artery; RT = Right:=; LT = Left. | ||||||

Image acquisition

All IA DSA studies were performed on a Philips Integris V3000 fluoroscopy unit with a 1024 × 1024 matrix. Angiography was performed using a standard projection format (anteroposterior, lateral, per-orbital and reverse oblique). Additional views were obtained to correspond with the embolisation working projection to clearly define the aneurysm neck.

MR examinations were performed on a 1.5 T Philips Gyroscan ACS NT using a quadrature head coil. After a localiser scan (TR/ TE /NEX 100/20/1) a single slice 2D phase contrast sagittal angiogram (FOV 13 cm, matrix 256 × 256, TR 14 ms,TE 7 ms, Flip angle 20°, peak velocity encoding rate 30 cm/s) was performed to identify the circle of Willis. An axial GrASE sequence (FOV 23 cm, matrix 256 × 179, TR 4689, TE 110, echo train length 5, EPI factor 5, NEX 4) through the brain and a 3D time-of-flight (TOF) MRA acquisition (TR 45; TE 7; flip angle 20°; FOV 21 cm; matrix 512 × 512; slice thickness 0.7 mm with 100 over contiguous slices; with the addition of an off resonance magnetisation transfer gradient to maximise background tissue suppression and a superior saturation band to minimise venous structures in the volume) was then performed through the circle of Willis.

Viewing and Post-processing

The formal angiogram was carefully analysed and used as the reference standard. MRA source data (SD) was transferred to a Philips Easy Vision Release 2.12 workstation for viewing of multi-planner reformatted images (MPR) and generation of maximum intensity projection (MIP) and 3D isosurface rendered images. Images were retrospectively reviewed in real time by consensus of two Neuroradiologists (WMA, RDL). The axial source data (SD) and multi-planar reformatted images (MPR) were viewed first, followed by the MIP and 3D isosurface rendered MR angiograms. Review of MRAs on the workstation allowed images to be viewed at variable window settings reducing errors due to inappropriate windowing. Generation of MIP images was completed in about 5 minutes. Surface extraction and 3Drendering took about 10 minutes to perform. Each individual modality was then scored on a 5 point scale of confidence (l. non-diagnostic; 2. poor; 3. acceptable; 4. good, 5. excellent) against the IA DSA appearance. This was performed for interpretation of parent artery flow, branch artery flow, residual neck definition and the detection of residual flow in coils. A similar 5 point score was then used to determine the overall MRA correlation with the IA DSA.

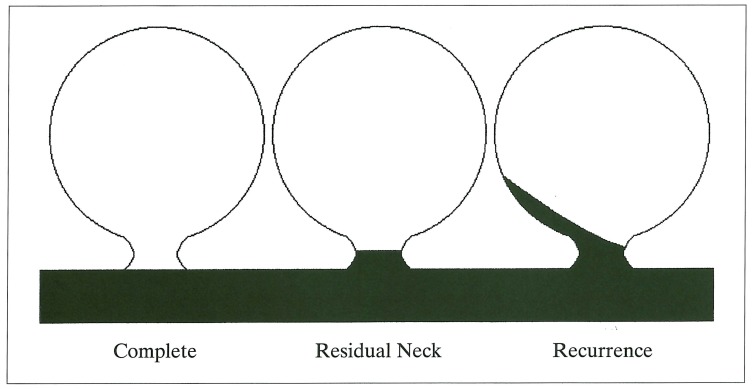

The anatomic result at follow-up was classified using a simplified modification of the schema adopted by Roy et Al5 (figure 1). This classified aneurysms into: 1. Complete occlusion; 2. Residual neck; and 3. Aneurysm recurrence.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of aneurysm recurrence. Simplified modification of the scheme adopted by Roy et Al 5.

Results

The data are summarised in tables 1,2 and 3. Twenty five patients (21 female; 4 male; average age 44; range 19 years to 74 years) with 28 intracerebral aneurysms treated by GDC underwent MR examination. All patients presented with subarachnoid haemorrhage. Mean follow-up angiography was at 252 days (range 43-815 days) post GDC embolisation. All aneurysms were small (< 10 mm) apart from two terminal internal carotid artery aneurysm which measured 12 mm (patient 15) and 14 mm (patient 25). Eight patients had basilar termination aneurysms, six patients had anterior communicating artery aneurysms, eight patients had internal carotid artery aneurysms, four patients had posterior inferior or superior cerebellar artery aneurysms and two patients had a middle cerebral artery aneurysm.

Table 2.

Overall mean scores for each imaging modality (figures in parentheses represent standard deviation)

| Source data |

MIP | 3D Isosurface |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Parent artery flow | 4.32 (± 0.47) |

3.64 (± 0.86) |

4.36 (± 0.75) |

| Branch artery flow | 4.16 (± 0.68) |

3.12 (± 0.86) |

3.72 (± 1.20) |

| Residual neck | 3.96 (± 0.67) |

2.76 (± 0.86) |

3.92 (± 0.90) |

| Residual flow in coil |

4.12 (± 0.83) |

3.2 (± 0.86) |

4.04 (± 0.93) |

Table 3.

Overall MRA Correlation with IA DSA

| Aneurysm Location |

Parent artery flow |

Branch artery flow |

Residual neck |

Aneurysm recurrence |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | AComm | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| 2 | RT PICA | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 3 | BT | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 4 | RT SCA | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 |

| 5 | BT | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| 6 | AComm | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| 7 | RT PICA | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 |

| 8 | AComm | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 9 | AComm | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 10 | BT | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 |

| 11 | BT | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 12 | BT | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 |

| 13 | LT ICA | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 14 | AComm | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 15 | BT | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 16 | RT ICA | 3 | 3 | 5 | 5 |

| 17 | LT ICA | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 |

| 18 | RT ICA | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 19 | LT PICA | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 20 | BT | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 21 | LT ICA | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 22 | AComm | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 |

| 23 | BT | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 24 | RT MCA | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 25 | RT ICA | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 26 | LT MCA | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| 27 | RT ICA | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 |

| 28 | LT ICA | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| Average | 4.8 | 4.5 | 4.7 | 4.6 | |

Clinical outcome was good in all cases with no adverse neurological sequelae. In 11 out of 28 aneurysms (39%) there was IA DSA evidence of residual neck, and in 8 out of 28 aneurysms (29%) evidence of recurrence. Overall MRA correlation was excellent in depicting residual neck or recurrence in 21 out of 28 aneurysms (75%); good in 4 out of 28 aneurysms (14%); and acceptable in 3 (11%).

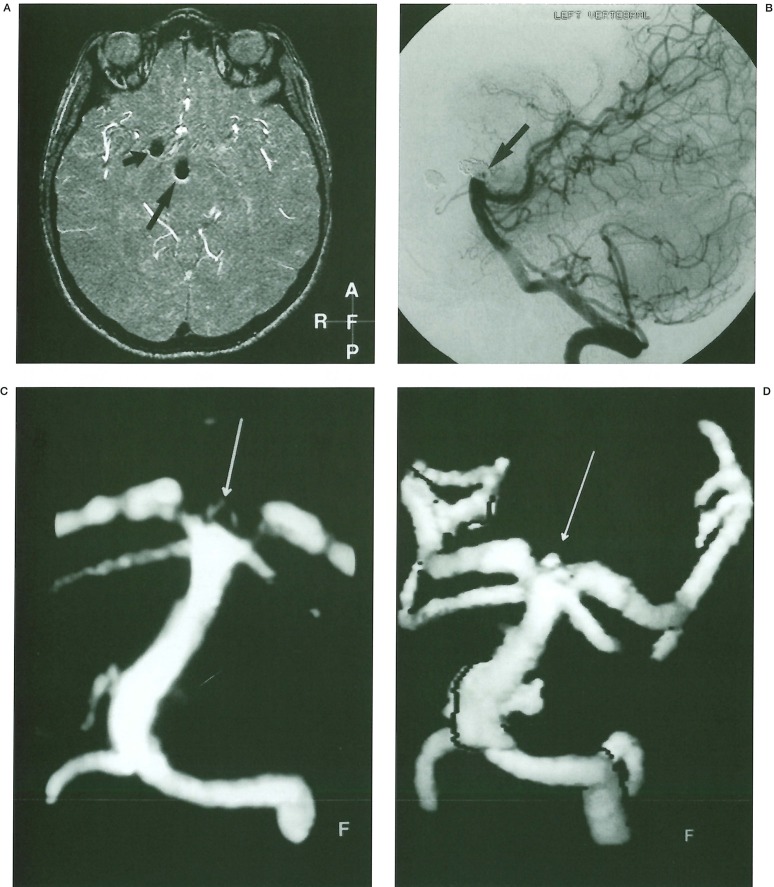

Source data/MPR was the preferred modality for detecting residual flow within the coil ball. High signal from flowing blood was readily distinguished from the signal void produced by the coil ball mesh (figure 2C). Minimal artefact due to the presence of the coil ball mesh was seen in most MRA studies. This thin, crescentic high-signal artefact, which was consistently seen around the coil ball signal void on the source data images (figure 3A), could easily be separated from flowing blood. It was never included inappropriately in either the MIP or 3D isosurface reconstructions.

Figure 2.

A 49 year old lady presented with subarachnoid haemorrhage due to rupture of an anterior communicating artery aneurysm. A) IA DSA left internal carotid artery injection per-orbital projection. Pre-treatment angiogram shows a saccular aneurysm arising from the anterior communicating artery with a superiorly projected nipple. B) IA DSA left internal carotid artery injection per-orbital projection angiogram performed 7 months after treatment. There has been considerable compaction of the coil ball mesh into the distal portion of aneurysm with evidence of recurrence. C) TOF MPR MRA source data parasagittal projection: The signal void due to the presence of the coil ball mesh is easily seen. There is a central, high signal focus (arrow) representing flow within the base of the aneurysm.

Figure 3.

A 43 year old lady underwent GDC embolisation of a basilar tip aneurysm, having presented acutely with a subarachnoid haemorrhage. An unruptured right terminal internal carotid artery aneurysm was also coiled. Check IA DSA and MR angiography was performed after 6 months. A) TOF MR A. Axial source image. Signal void due to the presence of coil ball mesh is seen in the treated basilar (long arrow) and right terminal carotid artery (short arrow) aneurysms. There is minimal high signal rim artefact associated with both aneurysms particularly around the posterior aspects of the coil ball. B) IA DSA left vertebral artery injection lateral projection: There has been minor compaction at the base of the coil ball mesh (arrow). C) TOF MIP MR A. Townes view of the basilar artery demonstrating a halo of high signal at the basilar tip (arrow) but no obvious neck remnant. D) TOF 3D isosurface MRA. Similar projection to the MIP reconstruction. A bleb of high signal (arrow) is seen at the tip of the basilar artery in keeping with a small remnant.

Minor degrees of coil ball compaction at the neck of an aneurysm were often difficult to assess on SD/MPR. Selecting the correct orthogonal plane to detect a small bulge in the parent vessel was often not possible. This was also difficult to assess on IA DSA because of the presence of a coil ball mesh. Surface-rendered 3D reconstruction showed this to best effect, because of its ability to detect a step in the lumen of the vessel (figure 3). High signal when seen was assumed to represent flow rather than thrombus because of the prolonged time interval between treatment and follow-up. This was confirmed on IA DSA. Misinterpretation of thrombus as flow did not happen in any of our cases.

Parent or branch vessels could usually be demonstrated by combining all MR modalities. If a parent vessel could not be seen with one modality, it could usually be seen with a different modality. When there was discontinuity of a vessel, but flow was seen distal to the point of discontinuity, patency was assumed. In one case of superior cerebellar artery aneurysm, the posterior communicating arteries were not displayed on 3D or MIP, but were demonstrated on MPR. In one case of basilar artery aneurysm the posterior communicating arteries were only seen on IA DSA. In one case of anterior communicating artery aneurysm, the MIP and 3D did not reliably demonstrate patency of the anterior communicating artery, but this was seen on MPR.

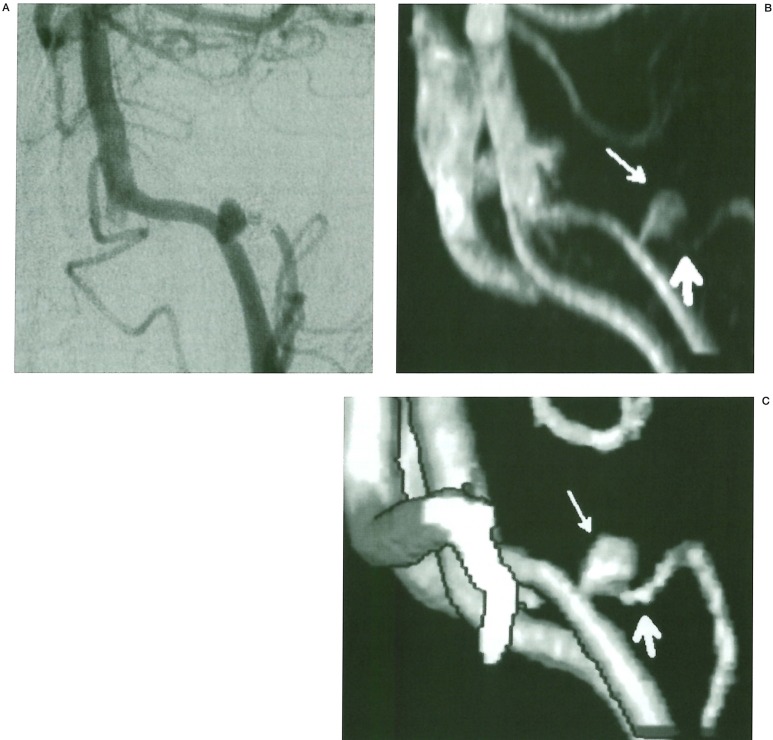

MIP MRA scored poorly in all categories when compared to the modalities of source data/MPR and 3D isosurface rendering, but particularly in defining the presence or absence of residual neck. In several cases a halo of high signal was seen at the neck around a recurrent area of aneurysm filling. Despite variations in window setting (figures 3C, 4B) this halo persisted and correlated poorly with IA DSA. Subjectively, aneurysmal remnants were undersized on MIP MRA, presumably due to under-representation of slow flow. This was consistent throughout a range of window settings.

Figure 4.

A 19 year old man presented with subarachnoid haemorrhage from a right terminal carotid artery aneurysm. Control IA DSA and MRA were performed at 6 months. A) IA DSA right carotid injection oblique frontal projection: There is aneurysm regrowth at the neck with a significant recurrence (arrow). B) TOF MIP MRA demonstrating a halo of high signal related to the carotid bifurcation at the site of the coiled aneurysm (arrow). No identifiable neck can be seen. C) TOF 3D isosurface MRA demonstrating a significant broad based neck remnant (arrow) with good IA DSA correlation.

This problem was not seen with surface ren-dered 3D images. In two patients the presence of a small residual neck was demonstrated on SD/MPR and 3D but not clearly seen on MIP MRA (figure 3). Other problems with MIP images are due to lack of depth and poor spatial perception. Excessive background noise also degrades images at lower window settings.

In three patients obscuration or narrowing of the parent and branch vessels created difficulties in interpretation. In the first patient with a treated posterior communicating artery aneurysm, narrowing of the parent vessels was noted. This was thought to be due to artefact from coil, but on review of the IA DSA was found to be genuine. In the second patient with a 12 mm left supraclinoid ICA aneurysm treat-ed with 18 system coils, there was significant artefactual loss of the supraclinoid ICA parent vessel. It was not clear whether the degree of signal loss was due to use of the 18 system or due to the size of the aneurysm, or both. At 12 mm, this was one of only two large aneurysm in the series. In a third patient who presented with SAH due to rupture of a basilar tip aneurysm, an incidental right terminal internal carotid artery (ICA) aneurysm was also treated. Significant signal loss of the parent vessel was seen at the base of the terminal ICA aneurysm, but not the basilar tip aneurysm.

Discussion

Since the introduction of GDC embolisation of intracranial aneurysms in 1990 over 16000 patients have been treated world-wide1. Whilst there is no doubt about its efficacy in preventing rehaemorrhage in acutely ruptured aneurysms in the short- and mid-term 1, the long-term durability of GDC has yet to be proven.

The anatomic results of treatment with GDC appear less satisfactory than with surgery5, but the significance of a small neck remnant in an aneurysm with complete sac occlusion is unknown. For this reason dedicated long-term clinical and angiographic surveillance of these patients is required. IA DSA has been regarded as the method of choice in evaluating aneurysm recurrence but this procedure is not without risk even in experienced hands 6, and incurs radiation exposure to both operator and patient. Because of the requirement for long-term review some morbidity and mortality is to be anticipated in this large cohort of patients. A non-invasive method of follow-up is therefore desirable.

Many authors have demonstrated the diagnostic accuracy of MR A in the prospective detection of intracranial aneurysms7,8,9, and in aneurysm detection after SAH10,11. There have been fewer studies documenting the utility of MRA in post GDC follow-up12,13. Safety should be of primary concern with a potential risk of heat generation due to current flow induced in a metallic object by alternating magnetic fields that may produce thermal damage to surrounding tissue. In vitro studies on the Guglielmi platinum coil4 have, however, documented no temperature rise when placed in a 1.5-T field using both fast spin echo (FSE) and gradient echo (GE) sequences. Similarly, no evidence of magnetic deflection or rotation was detected.

Other workers have confirmed the safety and image quality of the device in vivo12. We concur with this view and have seen no adverse effects in our patient cohort.

Image quality is vital and requires a homogenous magnetic field. Metallic objects may produce significant susceptibility artefact, distorting the local magnetic field and degrading the image. This effect is minimal with platinum which produces only a small circumferential high signal rim around the coil ball mass. The degree of artefact is comparable on conventional spin echo, FSE and GE sequences. This high signal rim could easily be differentiated from signal due to flow in our patient group, and did not impair the reconstruction process using either MIP or 3D-isosurface rendering.

All post-processing algorithms inevitably incur some degree of data reduction14 and can be viewed in isolation from the source data. We have demonstrated that review of source data increases confidence in interpretation of MRA images presented in a reconstructed format. We would strongly recommend, therefore, that whatever post-processing algorithm is used itshould not be interpreted in isolation without reference to source data. This is particularly important when viewing 3D isosurface rendered images which uses an operator defined threshold. Inappropriate thresholding may result in the inclusion of background noise in the processed image7 or exclusion of important residual flow within the aneurysm. Source image review is also not a necessary pre-requisite for MIP MRA generation and viewing, but this reconstruction technique does have recognised limitations 15. A single MIP image lacks depth and this can lead to problems of orientation. Because the MIP grey scale is derived from the composite value of all the pixels along an imaging plane, smaller structures may be assigned inappropriately low signal intensity. The signal intensity of flow must exceed the maximum signal from the background plus noise or it cannot be recognised as flow16.

For this reason small neck remnants or branch vessels may go undetected (figure 5). We have demonstrated two neck remnants that were not seen on MIP MRA, but were evident on SD/MPR and 3D isosurface MRA. In addition we have commonly seen aneurysm recurrence and neck remnants represented as a halo of high signal on MIP images which did not give a true reflection of aneurysm apperance (figure 4B). This was not a problem with surface rendered 3D images which consistently demonstrated greater correlation with the IA DSA (figure 4C). Background noise on MIP images can also become a problem on lower window settings.

Figure 5.

A 61 year old man presented with subarachnoid haemorrhage due to rupture of a left posterior inferior cerebellar artery (PICA) aneurysm. Because of a significant remnant control angiography was performed at three months. A, B) IA DSA left vertebral artery injection oblique projection: There is a large aneurysm remnant at the origin of the left PICA. C) TOF 3D isosurface MRA oblique projection: The left PICA (thick white arrow)is better demonstrated than on the MIP MRA. The aneurysm neck appears wide (thin white arrow).

By combining the MRA modalities of SD/MPR, MIP and 3D isosurface reconstruction we found excellent correlation with the IA DSA. In every case residual neck and aneurysm recurrence were correctly identified on MRA alone. In those cases where there was minimal compaction of the coil ball mesh with only a minor degree of filling at the aneurysm base, 3D isosurface MRA more accurately depicted the extent of the remnant. In three cases there was significant artefactual loss of the parent vessel, but in all these patients aneurysm occlusion had been complete. It is therefore difficult to say whether the presence of the coil ball mesh would have obscured signal due to flow within an aneurysm remnant. In aneurysms with evidence of recurrence, the ability to interrogate data by reformatting in multiple planes provided more information on the extent of recurrence than a conventional angiogram. High signal due to flow within an aneurysm recurrence was never obscured by the signal void due to the presence of coil.

3D TOF images use a T1 effect, with the flow of unsaturated spins into the saturated static image volume producing an increased signal. This signal is maximised when imaging is performed perpendicular to the flow direction axis. Slow flow around the base of an aneurysm may therefore become saturated and underrepresented in the source data. In addition tissue in the imaging volume with a short Tl, such as methaemoglobin, may not suppress. This can produce difficulties in separation of these tissues from residual flow in an aneurysm. Phase contrast MRA (PCA) has the potential to overcome some of these problems but also has limitations. PCA relies on a velocity dependent dephasing of spins for image formation and is more sensitive to slow flow. It does, however, require a preset velocity encoding (VENC) to maximise signal from the vessels of interest. It also will not include static short Tl tissues in the image.

It has, however, been shown to be inferior to 3D TOF MRA in the diagnosis of intracranial aneurysms17. This is in part due to a lower spatial resolution when compared to 3D TOF MRA and also due to the fact that flow velocity within an aneurysm is often much slower than in the parent vessel. Setting an appropriate VENC to maximise signal from both aneurysm and parent vessel may, therefore, be difficult. Problems with residual haemoglobin degradation products producing high background signal were not seen in our patient group. This is due to the fact that imaging is being performed some time after the ictus and also because of the relatively rapid removal of these products from the subarachnoid space.

A potential solution to the problem of slow flow and spin dephasing in the TOF technique is the use of contrast agents to shorten the Tl of flowing blood18,19. The use of ultrashort repetition times to reduce total acquisition times to less than a minute can further overcome saturation effects20. Black blood MRA, a T2 sequence that highlights the vessel lumen by making flowing blood appear black in contrast to surrounding static tissue may have advantages over both 3D TOF and PCA techniques particularly in regions of complex flow. In black blood MRA spin dephasing is advantageous contributing to the desired signal loss 21. Signal void from bone around the skull base and the inability to differentiate thrombus from true lumen may limit its use22.

MRA is unable to provide any information about the morphology of the coil ball mesh within a treated aneurysm, because of its representation as signal void. The presence or absence of coil compaction is an important predictor of aneurysm recurrence. In follow-up IA DSA studies a similar projection to the post embolisation angiogram is routinely used to allow a comparative study of the coil morphology. Plain films of the coil ball in a projection similar to the post-embolisation angiogram to assess the degree of compaction may allow greater confidence in interpreting the MRA data.

In conclusion, 3D TOF MRA appears to have a useful role in the long-term surveillance of patients treated with GDC for intracerebral aneurysm disease.

The technique has the potential to provide a non-invasive alternative to IA DSA and can reliably identify aneurysm recurrence in most cases. We have shown the importance of reviewing the source data and multi-planar reformats of this data and strongly recommend that MIP images are not looked at in isolation. Plain films of the skull may demonstrate changes in coil ball shape and provide complementary information to MRA.

References

- 1.Malisch TW, Guglielmi G, et al. Intracranial aneurysms treated with the Guglielmi detachable coil: midterm clinical results in a consecutive series of 100 patients. JNeurosurg. 1997;87:176–183. doi: 10.3171/jns.1997.87.2.0176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schievink WI. Genetics of intracranial aneurysms. Neurosurgery. 1997;40:651–663. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199704000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sankhla SK, Gunawardena WJ, et al. Magnetic resonance angiography in the management of aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage: a study of 51 cases. Neuroradiology. 1996;38:724–729. doi: 10.1007/s002340050336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hartman J, Nguyen T, et al. MR artifacts, heat production, and ferromagnetism of Guglielmi detachable coils. Am J Neuroradiol. 1997;18:497–501. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roy D, Raymond J, et al. Endovascular treatment of ophthalmic segment aneurysms with Guglielmi detachable coils. Am J Neuroradiol. 1997;18:1207–1215. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hankey GJ, Warlow CP, Sellar RJ. Cerebral angiographic risk in mild cerebrovascular disease. Stroke. 1990;21:209–222. doi: 10.1161/01.str.21.2.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bontozoglou NP, Spanos H, et al. Intracranial aneurysms: endovascular evaluation with three-dimensional-display MR angiography. Radiology. 1995;197:876–879. doi: 10.1148/radiology.197.3.7480772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ross JS, Masaryk TJ, et al. Intracranial aneurysms: evaluation by MR angiography. Am J Neuroradiol. 1989;11:449–456. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horikoshi T, Fukamachi A, et al. Detection of intracranial aneurysms by three-dimensional time-of-flight magnetic resonance angiography. Neuroradiology. 1994;36:203–207. doi: 10.1007/BF00588131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilcock D, Jaspan T, et al. Comparison of magnetic resonance angiography with conventional angiography in the detection of intracranial aneurysms in patients presenting with subarachnoid haemorrhage. Clin Rad. 1996;51:330–334. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(96)80109-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ida M, Kurisu Y, Yamashita M. MR angiography of ruptured aneurysms in acute subarachnoid haemorrhage. Am J Neuroradiol. 1997;18:1025–1032. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Derdeyn CP, Graves VB, et al. MR angiography of saccular aneurysms after treatment with Guglielmi detachable coils: Preliminary experience. Am J Neuroradiol. 1997;18:279–286. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cotroneo E, Dazzi M, et al. Magnetic resonance angiography for evaluation of intracranial aneurysms treated with Guglielmi detachable coils. Rivista di Neuroradiologica. 1998;11:19–25. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schreiner S, Paschal CB, Galloway RL. Comparison of projection algorithms used for the construction of maximum intensity projection images. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1996;20:56–67. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199601000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Atlas SW, Sheppard L, et al. Intracranial aneurysms: detection and characterisation with MR angiography with use of an advanced postprocessing technique in a blinded-reader study. Radiology. 1997;203:807–814. doi: 10.1148/radiology.203.3.9169709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Atlas SW, Listerud J, et al. Intracranial aneurysms: depiction on MR angiograms with a multifeature-extraction, ray-tracing postprocessing algorithm. Radiology. 1994;192:129–139. doi: 10.1148/radiology.192.1.8208924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ikawa F, Sumida M, et al. Comparison of three-dimensional phasecontrast magnetic resonance angiography with three-dimensional time of flight magnetic resonance angiography in cerebral aneurysms. Surg Neurol. 1994;42:287–292. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(94)90394-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bosmans H, Marchal G. Contrast enhanced MR angiography. Radiologe. 1996;36:115–123. doi: 10.1007/s001170050048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kouwenhoven M. Contrast enhanced MR angiography. Methods, limitations and possibilities. Acta Radiol Suppl. 1997;412:57–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Talagala SL, Jungreis CA, et al. Fast three-dimensional time of flight MR angiography of the intracranial vasculature. Mag Reson Imaging. 1995;5(3):317–323. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1880050316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Edelman RR, Mattle HP, et al. Extracranial carotid arteries: evaluation with “black blood” MR angiography. Radiology. 1990;177:45–50. doi: 10.1148/radiology.177.1.2399337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rubenstein D, Sandberg EJ, et al. T2 weighted three-dimensional turbo spin echo MR of intracranial aneurysms. Am J Neuroradiol. 1997;18(10):1939–1943. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]