Abstract

This paper attempts to briefly describe the International Society of Paediatric Oncology (SIOP) policy of treatment of nephroblastoma since first study (SIOP 1) launched in 1971 until today. It focuses on the advantages of the preoperative chemotherapy and the stratification of patients induced this way. Marked efficacy of the pretreatment opened the way for less aggressive surgical management also in case of the “so-called” regular unilateral cases: Nephron-sparing surgery and minimal invasive techniques will probably find its place in this field of pediatric surgical oncology; however, very careful selection of cases must be the priority.

KEY WORDS: Nephrectomy, nephroblastoma, preoperative chemotherapy

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

The treatment for Wilms’ tumor has a long tradition of the multicenter studies. First, the National Wilms’ Tumor Study (NWTS) launched the Pan-American study on this malignancy in 1969. Shortly later, International Society of Paediatric Oncology (SIOP) in Europe started an international cooperation in this field (1971).[1]

Both groups had similar aims, but tried to reach them in different ways. NWTS since its beginning advocated primary surgery whenever possible and the treatment related and adapted to the pathological postsurgical findings.[1] SIOP noticed that the intraoperative tumor rupture rate at that time was approximately 30% and tried to find a way to downstage the disease preoperatively and make surgery easier and decrease the rate of this main intraoperative complication. The first attempt searching for a method meeting these aims compared in the trial was the preoperative radiotherapy versus primary surgery (SIOP 1, 1971-1974). The intraoperative rupture rate in the preoperatively irradiated patients was 4% and stage I rate 31%, whereas in the primarily operated on was32 and 14%, respectively.[2] It had become clear that the preoperative radiotherapy downstages the disease and prevents the intraoperative tumor rupture. SIOP2 (1974-1976) confirmed this finding also for so-called small tumors. In this category of patients the intraoperative tumor rupture rate after radiotherapy fall dawn to 5% and in the primarily operated on remained high (20%).[1]

At that time it was already known, that radiotherapy shall be avoided the more, the younger is a child. Consequently, the next SIOP study (SIOP5, 1977-1979), also built as a trial, compared preoperative radiotherapy and preoperative chemotherapy and evidenced the equal efficacy of both these methods in preventing the tumor rupture and downstaging the disease. The first objective looked was solved: The preoperative chemotherapy with vincristine and actinomycin D given for 4 weeks markedly prevented Wilms’ tumor rupture and downstaged the disease.[1,3]

Continuing this way, SIOP was wondering whether a longer pretreatment could be even more effective in decreasing the intraoperative tumor rupture rate and improving the stage distribution. The SIOP9Trial and Study (1987-1991) started to compare 4-week vs 8-week schedules both with the same drugs and same schedule of administration (vincristine weekly and actinomycin D biweekly). Surprisingly, no further significant downstaging of the disease or a decrease in the intraoperative tumor rupture rate were observed. Also the survival curves were not different. For SIOP, it was argued to accept this 4-week preoperative chemotherapy as a “gold standard” for all patients aged more than 6 months at diagnosis with localized nephroblastoma.[4,5]

The treatment of patients staged IV (metastatic disease) and V (bilateral nephroblastoma) followed similar policy. The first group constitutes of approximately 12% of all the patients, the second one - 5%. In stage IV it was suggested to administer preoperatively three drugs (vincristine, actinomycin D, and doxorubicine) for 6 weeks. This schedule of the pretreatment appeared very effective. The overall long-term outcome in patients achieving complete remission after chemotherapy (metastasis disappeared) and the primary tumor surgery and in those after successful metastasectomy on regressing lung metastasis reached 83%. Regarding stage V patients, pretreatment was expected to lead to anephron-sparing surgery on at least one side leaving enough functional renal tissue. However, a very long preoperative chemotherapy seemed not to bring continuous effect. Nine to 12 weeks seemed adequate. Only very few cases required bilateral total nephrectomy and in more than 25% of patients bilateral nephron-sparing resections appeared possible with the same outcome as in case of one-sided total nephrectomy and nephron-sparing resection on the opposite side. Of course such comparisons must be made very carefully; the cases were selected according to tumor location within the kidney, response to chemotherapy, and the operating surgeon's opinion. It indicates that the results were both case- and surgeon-dependent. Anyway, currently, an attempt to bilateral partial nephrectomy in stage V patients is strongly suggested. Usually easier side shall be operated on first. After the easier side is operated on and the kidney resumed the function correctly, the child is operated on the more difficult tumor. The interval between the sessions is usually 2-3 weeks. One course of chemotherapy is recommended during this time. This approach helps avoiding perioperative dialysis following one-session bilateral resections when the kidneys may not resume sufficient function immediately.[1,6,7,8,9]

SIOP also explored the question of postoperative treatment; however, this aspect seems less important for surgery. The studies SIOP1, 2, and 5 were dealing with the duration of postoperative chemotherapy and the value of anthracyclines and postoperative radiotherapy in stage II and III patients (SIOP 6, 1980-1987). The use of anthracyclines improved the outcome for stage II (lymph nodes invaded = N+) in stage III cases, but rather not in stages II (with the lymph nodes free of tumor = N-). Although the results were importantat the time of those trials, several factors have changed and cannot serve as a definite indication for treatment at present. Anyway, all brought a lot of new understanding and explored the way to go.[10]

Recent protocols (SIOP 9301, 1993-2001) tried to adopt the aggressiveness of treatment to the real risk of the therapy failure. In this view, the preoperative chemotherapy offers an important selection value in terms of both the anatomical extension of the disease (change in the tumor volume) and, if applicable, also in the number and size of metastasis and its histological appearance. The tumors responding well to chemotherapy with high rate of necrosis had very good prognosis. In case of completely necrotic nephroblastoma, the overall survival reached 100% in case of stage I even if the postoperative treatment was omitted. On the other hand, high proportion of blastema surviving the preoperative chemotherapy implied prognosis almost as poor as anaplasia.[11,12,13,14]

Next study (SIOP 2001) changed the histopathological risk-grouping, taking into account these observations and asked again the question of the value of anthracyclines in the intermediate risk stage II and III patients on one hand, and decreasing the postoperative therapy in low riskgroup on the other.

Current study

Currently, SIOP Renal Tumor Study Group (RTSG) leads the SIOP 2001 study. It is based on the experience gained in the previous trials, proposes however new classification of histological risk groups and modified staging. Like in the previous studies, both factors are assessed after the preoperative chemotherapy. This pretreatment plays important role in stratifying patients to low risk (good responders; e.g., 100% necrotic), high risk (poorly responding; e.g., blastemal predominant or anaplastic), or intermediate risk (most common). This study asks randomized questions on whether the anthracyclines are necessary in the treatment of stage II and III intermediate risk histology Wilms tumor patients. The preliminary answer seems to suggest that the anthracyclines can be avoided in this group of children.[1,15]

Outlook of the study

All patients with renal tumors aged less than 18 years could be included in this multicenter international study. The diagnosis of the primary tumor is based on the ultrasound imaging; however, majority of patients also had CT and, more recently, also MRI. The lung metastasis was considered clinically important only if seen on the classical chest X-ray. In case of doubt on diagnosis, a fine-needle aspiration or Tru-Cut biopsy are allowed and do not imply any upstaging. Once the diagnosis is established, children follow one of the three ways:

Unilateral localized cases received 4-week pretreatment with vincristine (weekly) andactinomycin D (biweekly)

Metastatic patients — 6 weeks of vincristine-actinomycin D (like above) and doxorubicine on weeks 1 and 5

Bilateral tumors-vincristine-actinomycin D for no longer than 9-12 weeks in some cases reinforced with doxorubicine.

Children aged less than 6 months with localized disease was submitted to primary surgery if only their tumors were considered resectable.

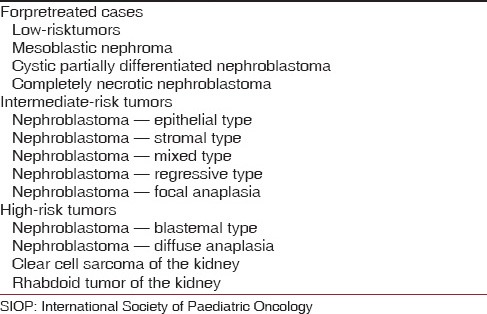

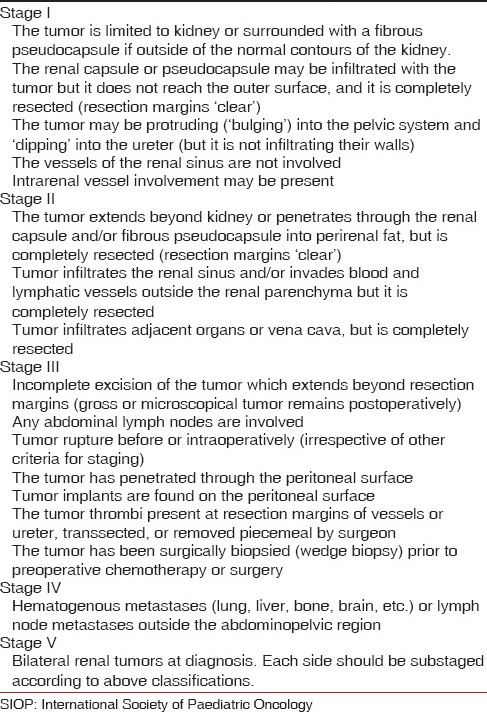

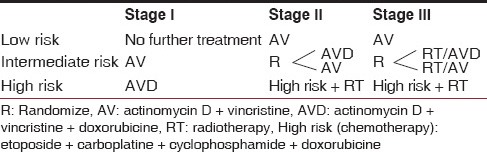

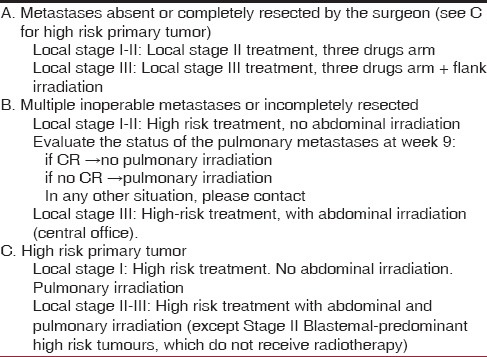

The detailed staging and the risk-grouping were performed at the time of surgery based on the pathology examination of the specimen. Further treatment was adapted to the clinical stage (at surgery) and histological risk group. The SIOP 2001 staging system and the histology risk grouping are cited in Tables 1 and 2. The treatment flowchart for localized cases is presented in Table 3. Stage IV patients followed more complicated rules, depending on both primary tumor and metastasis response and resectability [Table 4].[1,12]

Table 1.

Table 2.

The SIOP 2001 clinical staging system[1]

Table 3.

The post-operative treatment for stages 1-3 [1]

Table 4.

Stage IV, post-operative treatment[1]

Patients with bilateral disease had individualized treatment; however, in the postoperative part it relied on the general recommendations for a specific local stages/risk groups.[1]

Surgical remarks

Number of SIOP trials and studies were related to the surgical issues. Studies 1, 2, 5, and 9; as it was mentioned above; looked in the randomized manner for a way to prevent the intraoperative tumor rupture. The retrospective analysis revealed that not only the intraoperative tumor rupture became rare after the pretreatment, but also other surgery-related complications. The rate of these complications did not exceed 8% in the pretreated patients registered in the SIOP9 (including the intraoperative tumor ruptures), whereas NWTS-3 reported 19.8% of the surgery-related complications among primarily nephrectomized patients ignoring the intraoperative tumor ruptures.[16,17,18]

Although SIOP strongly recommends classical open tumor-nephrectomy according to Ladd and Gross suggestions, several new questions arise. Other surgical questionswere related to nephron-sparing nephrectomies in unilateral patients and the role of the minimal invasive nephrectomy. Both, however not recommended, were occasionally performed in the SIOP patients. Nephron-sparing resection was performed only in 3% of patients with unilateral Wilms tumor. The outcome was excellent and the overall survival reached 100%. Basic problem even in patients well selected for nephron-sparing resection relates to the regional lymph node status. The lymph nodes positive for tumor imply radiotherapy which conflicts the benefits of leaving the part of the kidney which will have to be covered by the field of radiotherapy and most probably will turn fibrotic. On the other hand, the lymph nodes are positive in 5.5% of patients, but particularly rarely in tumors with the initial volume smaller than 300 ml.[1,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27]

Regarding minimal invasive nephrectomy, it seems to bring very limited benefit to the patients with nephroblastoma when compared with the classical open surgery. Laparotomy to extract the mass is always necessary, surgical technique is more difficult, and lymph nodes sampling uneasy. A series of patients operated this way were analyzed by within SIOP studies. Despite good outcome, these children had enough number of lymph nodes sampled only in minority. Minimal invasive nephrectomy and nephron-sparing nephrectomy shall not compete—definitely more benefit is associated with partial nephrectomy performed the classical way. Any of those new techniques should not be undertaken in case of risk of decreasing the chance for complete resection compared to the classical way.[28,29,30,31,32]

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.De Kraker J, Graf N, Pritchard-Jones K, Pein F. Nephroblastoma clinical trial and study SIOP 2001, Protocol. SIOP RTSG. 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lemerle J, Voute PA, Tournade MF, Delemarre JF, Jereb B, Ahstrom L, et al. Preoperative versus postoperative radiotherapy, single versus multiple courses of Actinomycin D in the treatment of Wilms’ tumor. Preliminary results of a controlled clinical trial conducted by the International Society of Paediatric Oncology (SIOP) Cancer. 1976;38:647–54. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197608)38:2<647::aid-cncr2820380204>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lemerle J, Voûte PA, Tournade MF, Rodary C, Delemarre JF, Sarrazin D, et al. Effectiveness of preoperative chemotherapy in Wilms’ tumor: Results of an International Society of Paediatric Oncology (SIOP) clinical trial. J Clin Oncol. 1983;1:604–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1983.1.10.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tournade MF, Com-Nougue C, De Kraker J, Ludwig R, Rey A, Burgers JM, et al. Optimal duration of pre-operative therapy in unilateral and non-metastatic Wilms tumour in children older than 6 months: Results of the ninth International Society of Paediatric Oncology Wilms tumour trial and study. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:488–500. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.2.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Godzinski J, Tournade MF, De Kraker J, Ludwig R, Weirich A, Voute PA, et al. The role of preoperative chemotherapy in the treatment of nephroblastoma-the SIOP experience. Societe Internationale d’Oncologie Pediatrique. Semin Urol Oncol. 1999;17:28–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Kraker J, Lemerle J, Voute PA, Zucker JM, Tournade MF, Carli M. Wilms’ tumour with pulmonary metastases at diagnosis: The significance of primary chemotherapy. International Society of Pediatric Oncology Nephroblastoma Trial and Study Committee. J Clin Oncol. 1990;8:1187–90. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1990.8.7.1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ritchey ML, Coppes MJ. The management of synchronous bilateral Wilms’ tumor. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 1995;9:1303–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herrera JM, Gauthier F, Tournade M, Zucker JM, Gruner M, Révillon Y, et al. Bilateral synchronous Wilms’ tumour (WT): Is it a good model of conservative surgery for unilateral WT? Med Pediatr Oncol. 1996;27:219. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Godzinski J, Tournade MF, Weirich A, De Kraker J, Ludwig R, Gauthier RF, et al. Prognosis for the bilateral Wilms’ tumour patients after non-radical surgery: The SIOP-9 experience. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1998;31:241. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tournade MF, Com-Nougué C, Voûte PA, Lemerle J, de Kraker J, Delemarre JF, et al. Results of the Sixth International Society of Pediatric Oncology Wilms’ Tumor Trial and Study: A risk-adapted therapeutic approach in Wilms’ tumor. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:1014–23. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.6.1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vujanic GM, Harms D, Sandstedt B, Weirich A, de Kraker J, Delemarre JF. New definitions of focal and diffuse anaplasia in Wilms’ tumour: The International Society of Paediatric Oncology (SIOP) experience. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1999;5:317–23. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-911x(199905)32:5<317::aid-mpo1>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vujanic GM, Delemarre JF, Sandstedt B, Harms D, Boccon-Gibod L. The New SIOP (Stockholm) Working Classification of Renal Tumours of Childhood. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1996;26:145–6. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-911X(199602)26:2<145::AID-MPO15>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boccon-Gibod L, Rey A, Sandstedt B, Delemarre J, Harms D, Vujanic G, et al. Complete necrosis induced by preoperative chemotherapy in Wilms tumor as an indicator of low risk: Report of the International Society of Pediatric Oncology (SIOP) Nephroblastoma Trial and Study 9. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2000;34:183–90. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-911x(200003)34:3<183::aid-mpo4>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Graf N, van Tinteren H, Bergeron C, Pein F, van den Heuvel-Elbrink MM, Sandstedt B, et al. Characteristics and outcome of stage II and III non-anaplastic Wilms’ tumour treated according to the SIOP trial and study 93-01. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:3240–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.43rd Congress of the International Society of Paediatric Oncology (SIOP) 2011. SIOP Abstracts. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2011. Vol. 57. Auckland, New Zealand: 2011. Oct 28th-30th, pp. 705–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Godzinski J, Tournade MF, de Kraker J, Lemerle J, Voute PA, Weirich A, et al. Rarity of surgical complications after post chemotherapy nephrectomy for nephroblastoma. Experience of the International Society of Paediatric Oncology — Trial and Study “SIOP-9”. International Society of Paediatric Oncology Nephroblastoma Trial and Study Committee. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 1998;8:83–6. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1071127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schamberger RC, Guthrie KA, Ritchey ML, Haase GM, Takashima J, Beckwith JB, et al. Surgery-related factors and local recurrence of Wilms tumor in National Wilms Tumor Study 4. Ann Surg. 1999;229:292–7. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199902000-00019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ritchey ML, Kelalis PP, Breslow N, Etzioni R, Evans I, Haase GM, et al. Surgical complications after nephrectomy for Wilms’ tumor. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1992;175:507–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gross RE. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Co; 1953. The surgery of infancy and childhood. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jereb B, Tournade MF, Lemerle J, Voûte PA, Delemarre JF, Ahstrom L, et al. Lymph node invasion and prognosis in nephroblastoma. Cancer. 1980;45:1632–6. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19800401)45:7<1632::aid-cncr2820450719>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martins GA, Espana M. Partial nephrectomy for nephroblastoma — A plea for less radical surgery. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1989;17:320. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moorman-Voestermans CG, Staalman CR, Delamarre JF. Partial nephrectomy in unilateral Wilms’ tumour is feasible without local recurrence. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1994;23:218. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moorman-Voestermans CG, Aronson DC, Staalman CR, Delemarre JF, de Kraker J. Is partial nephrectomy appropriate treatment for unilateral Wilms’ tumor? J Pediatr Surg. 1998;33:165–70. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(98)90425-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cozzi DA, Schiavetti A, Morini F, Castello MA, Cozzi F. Nephron-sparing surgery for unilateral primary renal tumor in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2001;36:362–5. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2001.20717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoellwarth ME, Urban C, Linni K, Lackner H. Brussels: 3rd International Congress of Paediatric Surgery; 1999. Partial nephrectomy in patients with unilateral Wilms tumor; p. 36. Abstract book. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Godzinski J, van Tinteren H, de Kraker J, Graf N, Bergeron C, Heij H, et al. SIOP Nephroblastoma Trial & Study Committee. Nephroblastoma: Does the decrease in tumor volume under preoperative chemotherapy predict the lymph nodes status at surgery? Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;57:1266–9. doi: 10.1002/pbc.23147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wilde J, Aronson DC, Sznajder B, Tinteren HV, Powis M, Okoye B, et al. 44th Congress of the International Society of Paediatric Oncology (SIOP) 2012. Vol. 59. London: Pediatr Blood Cancer; 2012. The first experience with nephron sparing surgery (nss) for unilateral wilms tumor (uwt) within wt siop 2001; pp. 965–1152. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Godzinski J, Warmann SW, van Tinteren H, Graf N, Fuchs J. Berlin: World Congress of Pediatric Surgery; 2013. Minimally Invasive Surgery for Nephroblastoma — Data from SIOP 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Duarte RJ, Dénes FT, Cristofani LM, Srougi M. Laparoscopic nephrectomy for Wilms’ tumor. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2009;9:753–61. doi: 10.1586/era.09.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Varlet F, Stephan JL, Guye E, Allary R, Berger C, Lopez M. Laparoscopic radical nephrectomy for unilateral renal cancer in children. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2009;19:148–52. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e31819f204d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fuchs J, Schafbuch L, Ebinger M, Schäfer JF, Seitz G, Warmann SW. Minimally invasive surgery for pediatric tumors — Current state of the art. Front Pediatr. 2014;2:48. doi: 10.3389/fped.2014.00048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Godzinski J, deKraker J, Graf N, Pritchard-Jones K, Bergeron C, Heij H, et al. Is the number of lymph nodes sampled at Wilms’ Tumour nephrectomy predictive for detection of the regional extention of the disease? Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2004;43:303–503. [Google Scholar]