Abstract

A dicarboxylated ethynylarene was shown to behave as a fluorescent chemosensor for millimolar concentrations of polyamines when mixed with Cd(II), Pb(II) or Zn(II) ions at micromolar concentrations. A bathochromic shift and intensification of fluorescence emission was observed with increasing amounts of metal ion in the presence of aqueous polyamines buffered at pH = 7.6. Such perturbations manifested as ‘turn-on’ signals from a ratiometric comparison of emission intensities at 390 nm versus 340 nm. Using Pb(II) as the metal mediator, spermine was selectively detected as a 40-fold signal enhancement relative to spermidine, putrescine, cadaverine and several other non-biogenic diamines. Evaluation of additional triamine and tetraamine analytes showed the influence that amine group quantity and spacing had on signal generation. By increasing the ratio of Pb(II) relative to ethynylarene, the detection limit for spermine was successfully lowered to a 25 micromolar level. Noncovalent association between ethynylarene, metal ion and polyamine are believed to promote the observed spectroscopic changes. This study exploits the subtle impact that polyamine structural identity has on transition metal chelation to define a new approach towards polyamine chemosensor development.

Keywords: Sensor, Fluorescent, Ratiometric, Spermine Detection, Ethynylarene

1. Introduction

Spermine, an aliphatic tetraamine, is among the naturally occurring polyamines found in essentially all eukaryotic cells. [1] Existing as a polycation under biological conditions, it is structurally similar to the other biogenic polyamines spermidine, putrescine and cadaverine. Because it plays an important role in cell growth and differentiation, an elevated spermine level has been proposed to serve as a cancer biomarker. [2–5] Hence, analytical methods enabling the detection of spermine are of interest for developing new health diagnostic tools.

Long established methods for the detection of polyamines include chromatographic analysis [6–9] and electrophoresis. [10, 11] Such techniques are relatively time consuming with expensive instrumentation requirements. Developing new methods for the detection of polyamines is therefore an active area of research. In recent years there has been a significant increase in the number of reports describing the development of optical methods for the detection of biogenic polyamines. Because such polyamines lack useful UV-Visible spectroscopic signatures themselves, systems capable of displaying spectroscopic changes in response to the presence of such analytes are necessary. Several examples of colorimetric and/or turn-on fluorescence sensors have been established, driven by the interactions of small molecule chromophores, [12–15] organic polymers, [16, 17] coordination compounds [18] and nanoparticles [19–21] with polyamine analytes of interest. Unfortunately, the majority of these methods have shown a limited ability to discriminate among spermine, spermidine, putrescine and cadaverine analytes.

The utilization of small molecule chromophores displaying environmentally-sensitive fluorescence emission is a long established approach to developing new chemosensing tools. [22–25] Such molecules can be tailored towards binding specific analytes of interest using the established tools of synthetic organic chemistry. Numerous reports have described the use of conformationally flexible arene-based chromophores for the development of chemosensing systems, targeting a diverse range of analytes such as metal cations, [26–32] anions [33–37] and neutral organic molecules. [34, 38–40]

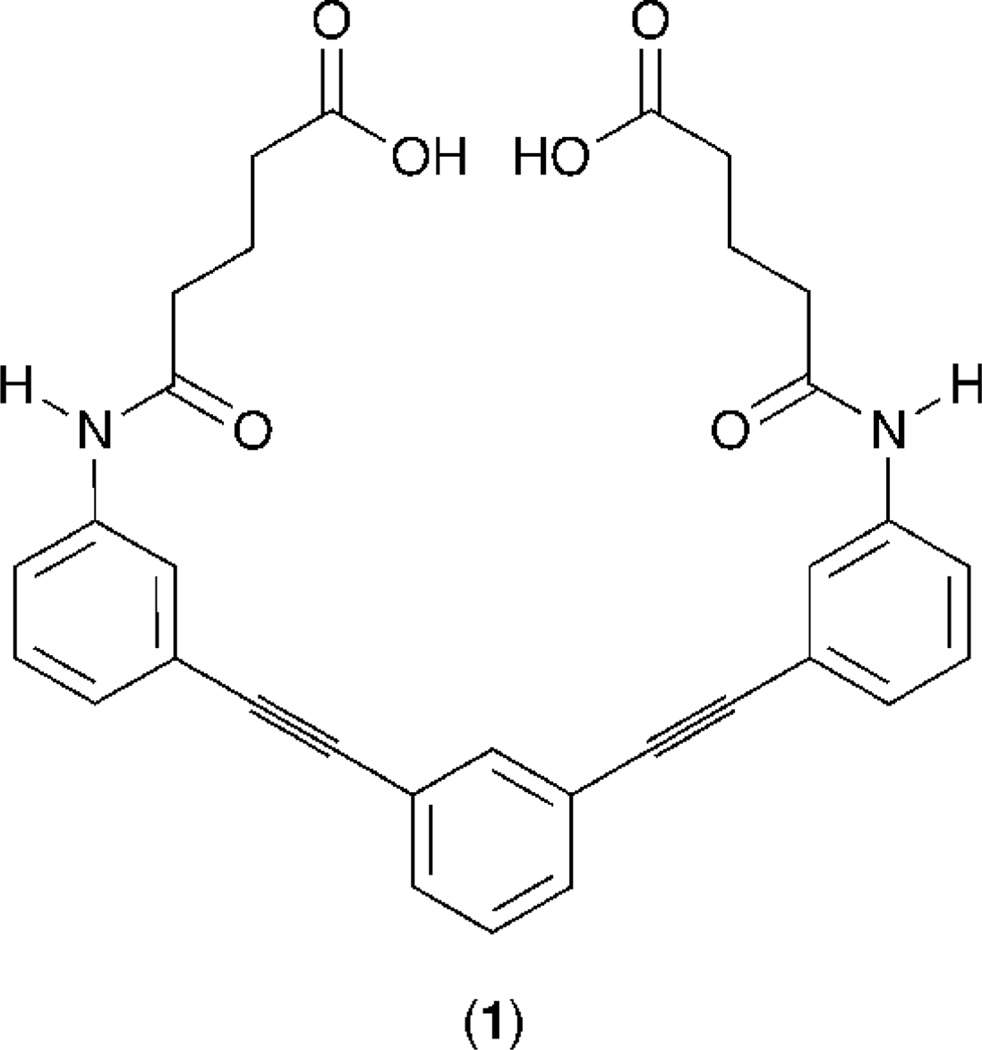

It was recently reported that ethynylarene 1 (Figure 1) was capable of serving as a fluorescent chemosensor for Cd(II), Pb(II) and Zn(II) analytes in a buffer-dependent manner. [41] Notably, the bathochromic shifts in fluorescence emission displayed by this system in pH = 7.6 aqueous conditions were only observed for buffer molecules possessing one amine unit and at least one additional heteroatom, such as in TRIS, MOPS and HEPES. [41] It was demonstrated that the ‘turn-on’ fluorescence signal generated by this sensor was promoted by a three-component association, which was proposed to include a coordinate interaction between buffer and transition metal as well as an electrostatic interaction between the carboxylate unit of the sensor and the ammonium unit of the buffer. [41]

Figure 1.

Identity of ethynylarene sensor 1.

The realization that the turn-on fluorescence signaling for transition metal ion detection by 1 derived from a three-component interaction inspired the investigation described herein. Because it was established that 1 and an amine-containing buffer could be used as a system to detect metal ion analytes, it seemed plausible that 1 and metal ions could be used as a system to detect an amine-containing analyte. Because it was previously observed that minor changes in buffer molecular identity significantly impacted signal generation, it seemed plausible that such sensitivity to amine identity might be exploited to discriminate between polyamine analytes with similar molecular composition. Herein we report the details of such an investigation, whereby ethynylarene-based sensing systems capable of selectively detecting spermine have been identified by high throughput assays, and a comparative analysis of how polyamine analyte identity impacts signal generation has been completed.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Chemicals

Compound 1 was prepared as previously described. [41] Polyamine analytes spermine (2), spermidine (3), ethylenediamine (4), 1,3-diaminopropane (5), putrescine (6), cadaverine (7), 1,6-diaminohexane (8), 1,7-diaminoheptane (9), 1,8-diaminooctane (10), diethylenetriamine (11), N-(2-aminoethyl)-1,3-propanediamine (12), bis(3-aminopropyl)amine (13), triethylenetetramine (14), N-(2-aminoethyl)-N-3-aminopropylethylene diamine (15), N,N′-bis(2-aminoethyl)-1,3-propanediamine (16), 1,2-bis(3-aminopropylamino)ethane (17), N,N′-bis(3-aminopropyl)-1,3-propanediamine (18) and tris(2-aminoethyl)amine (19) were used as purchased from Aldrich. CdCl2, PbCl2 and ZnCl2 were used as purchased from Strem.

2.2 Assays comparing polyamine analytes

A 1 mM stock solution of 1 was prepared in 0.1 M NaOH (aq). (This is because 1 dissolves slowly directly in neutral water, but will dissolve quickly in basic water and stay in solution at this concentration upon neutralization.) A series of 100, 200, 300, 400 and 500 µM aqueous solutions of metal chloride salts were prepared by dissolving in Millipore water. Polyamine stock solutions were prepared at 50 mM and 5 mM in Millipore water. The pH of these stocks were then adjusted to pH = 7.6 using either 1 M HCl (aq) or 1 M NaOH (aq) as necessary. Assays were performed in 96 well black plates. To each well was added 10 µL of 1 stock solution, 90 µL of buffered polyamine solution and 100 µL of metal stock solution, resulting in assay mixtures containing 50 µM sensor and either 2.5 mM or 25 mM polyamine along with 50, 100, 150, 200, or 250 µM metal cations. Three control wells were used for each metal/sensor/amine combination: metal only, amine only, and amine and sensor only, replacing the missing component with a matching volume of Millipore water. (Three control wells and five metal concentrations filled one column of the 96 well plate.)

2.3 Dilution assays for Pb(II) and spermine

For the spermine dilution assays, the 2.5 mM buffered spermine solution was diluted 1:1 using Millipore water down eight rows of the plate (giving concentrations ranging from 2.5 mM to 20 uM). Stock solutions of 1 and metal cation were added as described in Section 2.2. For the 25 µM spermine assay, an analogous mixing procedure as described in Section 2.2 was used but with the following stock solutions: 1 at 50 µM, buffered spermine at 50 µM and Pb(II) ranging from 50 µM to 5 mM. This allowed the evaluation of 25 µM 1 and 25 µM spermine with Pb(II) concentrations ranging from 25 µM to 2.5 mM.

2.4 Spectroscopic Measurements

Fluorescence spectra were obtained using a Tecan Infinite M200 plate reader. Each well was excited at 280 nm and the emission measured at 5 nm increments between 320 nm and 520 nm. Five scans per datapoint were taken and averaged for each well. Measurements were obtained at room temperature. Fluorescence quantum yield (ϕF) determination for 1 was measured via the comparative method [42] using 2-aminopyridine as the standard. [43]

2.5 Ratiometric Analysis

The turn-on signals were generated by comparing the ratio of fluorescence emission at 390 nm with that at 340 nm (Response = Em(390)/Em(340)) for a given well in the assay. While easily discernable bathochromic shifts occurred for all sensor-metal-buffer combinations classified as generating a turn-on signal, this ratiometric approach enabled a clearly interpretable bar graph representation of analyte recognition to be defined, which was useful for comparing large sets of data as well as discriminating signals of similar bathochromic shift but disparate emission intensity. A value of 1.0 was selected as the minimum threshold for defining a signal as turn-on (such as in defining dilution limits), which was approximately 2-fold greater intensity than baseline in these studies.

3. Results and discussion

3.1 Comparison of biogenic amines and diamines

Metal ions Cd(II), Pb(II) and Zn(II) were each utilized as metal mediators in these assays due to their proven compatibility with 1 in generating turn-on signals. [41] The initial group of polyamines evaluated were spermine (2), spermidine (3), ethylenediamine (4), 1,3-diaminopropane (5), putresceine (6), cadaverine (7), 1,6-diaminohexane (8), 1,7-diaminoheptane (9) and 1,8-diaminooctane (10) (Figure 2). In addition to the four major biogenic polyamines (2, 3, 6, 7), this group includes diamines with shorter (4, 5) and longer (8–10) carbon chain spacing in order to gain insight into the ability of this system to discriminate between similar aliphatic polyamines. The initial concentrations of polyamines evaluated were 25 mM and 2.5 mM. While these concentrations are significantly higher than the µM concentrations in which biogenic amines are typically measured when testing biological fluids, [2] these concentrations were selected initially in order to approximate the buffer concentration of the previously reported assays.

Figure 2.

Identities of polyamine analytes examined in this study.

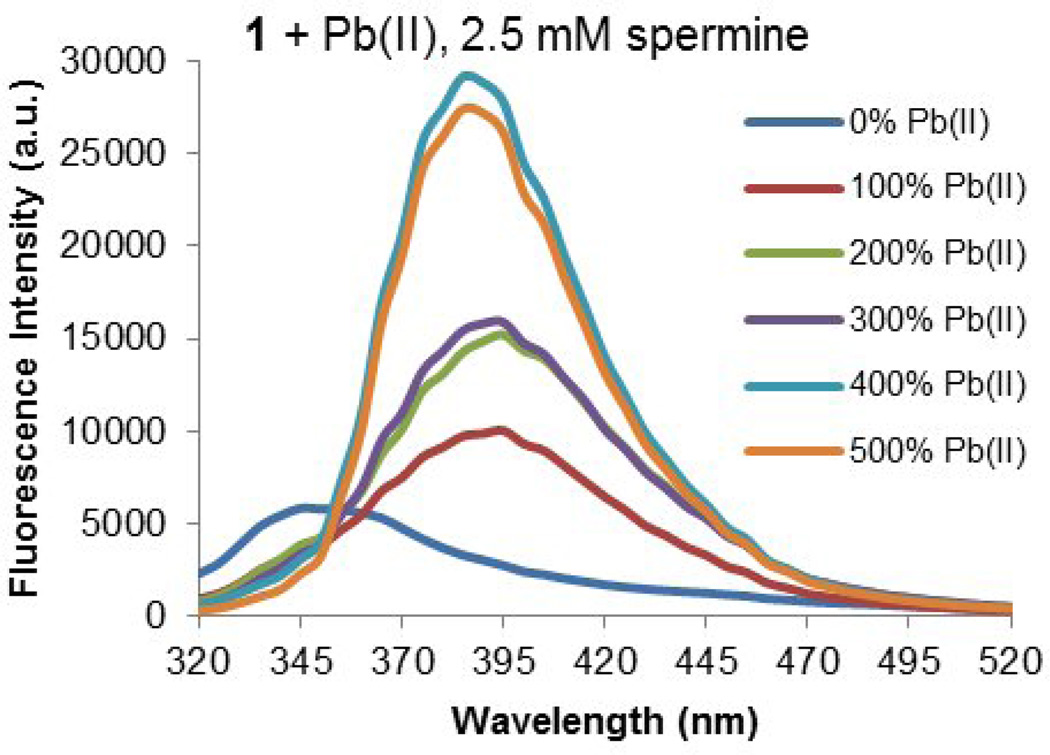

The Cd(II), Pb(II) and Zn(II) promoted ratiometric responses of 50 µM aqueous solutions of 1 when mixed with buffered aqueous polyamines 2–10 are summarized in Figures 3, 4 and 5. These turn-on responses were generated by comparing the emission intensity at 390 nm versus 340 nm as the metal cation amount increased from 0–5 equivalents relative to 1 with a consistent concentration of polyamine. A representative example of the overall spectroscopic changes in response to increasing amounts of metal mediator is shown in Figure 6, where a 50 nm bathochromic shift and intensification of emission intensity are observed. This response is nearly identical to that previously observed for TRIS buffered systems. [41] While the intensity of the turn-on response varies significantly as metal cation and analyte components are varied, the bathochromic shift itself is largely independent of metal cation or polyamine identity, changing by no more than 5 nm among the conditions studied. In the absence of metal cation or polyamine, 1 displays a fluorescence quantum yield of 0.41% (ϕF = 0.0041) under aqueous conditions for its 345 nm emission band.

Figure 3.

Ratiometric analysis for assays of 1 (50 µM) with 0–5 equiv of Cd(II) in the presence of 2.5 mM and 25 mM polyamine analytes 2–10 in pH = 7.6 aqueous solution.

Figure 6.

Emission of 1 (50 µM) in response to increasing amounts of Pb(II) in the presence of 2.5 mM spermine analyte in pH = 7.6 aqueous solution.

At the higher 25 mM concentration surveyed, many of the polyamines generated turn-on signals. That similar patterns of signal generation among Cd(II), Pb(II) and Zn(II) were observed is not surprising as these metals are known to share similar binding profiles with polyamine chelators in aqueous solution. [44–46] Some variation in the patterns of responses was nonetheless observed among these three metal cations, with Cd(II) generating the most turn-on signals and Zn(II) generating the least. Selectivity among biogenic polyamines was also impacted by metal selection. Whereas spermidine was detected by both Cd(II) and Zn(II), it was not by Pb(II). Among the four major biogenic polyamines, Pb(II) detected only spermine at the 25 mM concentration, while Cd(II) detected all four.

At the lower 2.5 mM concentration surveyed, there were significantly fewer turn-on signals for each of the three metal cations. The overall trend of selectivity resembled that of the higher concentration assays, with 1+Cd(II) showing turn-on signals for the majority of polyamine analytes. More selective was 1+Zn(II), showing a strong signal for spermine and a weaker signal for spermidine. Most selective was 1+Pb(II), which generated a turn-on signal only for spermine (along with a signal strength approximately 40-fold over baseline).

These subtle metal-dependent differences in signal generation are similar to those previously observed for 1 in buffered systems. [41] At the pH level of the assays, 1 should exist in an anionic form and the polyamine analytes in a cationic form. Hence, it is noteworthy that in the absence of metal cation no significant turn-on signaling was observed for any of the polyamines studied. This establishes that simple electrostatic interactions between the carboxylate groups of 1 and the ammonium groups of the polyamine are not the driving force for association and signaling at the concentrations evaluated. Only with the addition of metal cation is the turn-on signal generated. An analogous interaction to the previously studied buffered systems may therefore be occurring, where metal-amine chelation plays a critical role in signal generation by 1.

A comprehensive body of literature describes the chelating interactions between aliphatic amines and transition metal ions. [47–49] Due to the multitude of factors impacting the binding energies between polyamine chelators and transition metals, it is often difficult to predict optimal metal-chelator pairings. [50] Most pertinent to the study presented herein, it is known that varying the spacing between amine groups from ethylene to propylene units can significantly impact metal binding due to changes in chelator flexibility, metallocycle ring size of the bound complex, and differences in nitrogen basicity. [47, 48] Due to the complexity of this issue in identifying ideal metal-polyamine pairings, it could be argued that using a high-throughput approach to screen many metal-polyamine pairings, rather than design and prepare individual pairings, is an attractive option for efficiently identifying combinations that display desirable properties. [51]

3.2 Comparison of triamines and tetraamines

In order to better understand which molecular properties of spermine might be responsible for its strong signaling in the 1+Pb(II) system, a second round of assays was performed using an additional set of commercially available polyamine analytes, 11–19 (Figure 2). As spermine was the only tetraamine studied in the initial assays, it was suspected that its strong binding might simply be due to its larger quantity of amine groups. Hence, a selection of tri- and tetraamines are represented among 11–19. Also noted in the initial round of assays were the significant differences in signal generation by polyamines differing by only one carbon unit. With 2, 3 and 5 showing the strongest signals in general, and each containing at least one propylene spacer between amine units, a systematic examination of ethylene versus propylene spacing between amine units was also enabled by the selection of analytes 11–19.

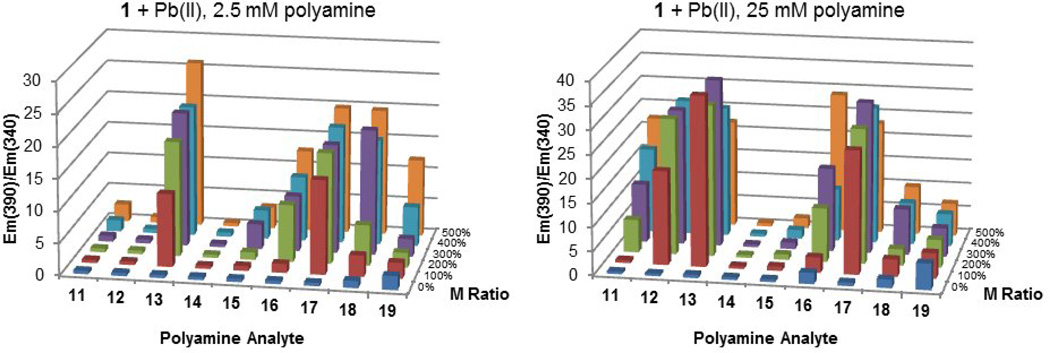

The summary of ratiometric responses for 1+Pb(II) against analytes 11–19 at both 25 and 2.5 mM concentrations is summarized in Figure 7. Because not all of the tetraamines generated significant turn-on signals (such as 14 and 15), this clearly establishes that spermine’s selectivity is not due simply to its tetraamine composition. Among 11–19, a general preference for propylene spacing between amine units over ethylene spacing seems apparent, with 13, 17 and 18 showing the strongest signals at low concentrations. (Unfortunately for the sake of this study, analogous tri- and tetraamines with four-carbon spacing between amine units were not commercially available.) Acute differences in signaling were observed for analytes with minor differences in overall chain length (such as 13 versus 14), and even between analytes with identical chain length (such as 15 versus 16). Such observations reinforce the hypothesis that signal generation does not derive from simple electrostatic interactions between anionic 1 and cationic analyte, but rather a more complicated binding event that includes chelating interactions between metal cation mediator and polyamine analyte. A chelating interaction is further supported by comparing 19 with 14. Each is a tetraamine regioisomer with ethylene spacing, but the branched nature of 19 increases its metal chelating ability relative to 14, which may help to promote a turn-on signal.

Figure 7.

Ratiometric analysis for assays of 1 (50 µM) with 0–5 equiv of Pb(II) in the presence of 2.5 mM and 25 mM polyamine analytes 11–19 in pH = 7.6 aqueous solution.

3.3 Dilution assays for Pb(II) system with spermine

Whereas the three-component nature of these systems complicates discernment of the exact binding mechanism, as well as exponentially increases the number of potential assay iterations, it does impart one significant advantage over two-component chemosensors. In those systems where a binary sensor-analyte interaction leads to signal generation, once the chromophore/analyte pairing is diluted below its binding constant there is little that can be done to increase the sensitivity of the system. In contrast, a three-component system affords an additional parameter that might be beneficial for engineering improved sensor responses.

In order to determine the lower detection limit for the 1+Pb(II) system, 1 was held constant at 50 µM with 0–5 equivalents of Pb(II) mediator, while the spermine concentration was varied between 2.5 mM and 2 µM. Between the 620 µM and 310 µM dilution levels of spermine, a loss of discernable turn-on signal occurred. Because it was observed for 1 that signal strength generally increases with increasing metal concentration, it was posited that the spermine detection limit of 1+Pb(II) could be lowered by increasing the relative amount of metal mediator. With the goal of identifying a sensor able to operate at concentrations approaching biological relevance (low micromolar), it was of interest to identify whether 1+Pb(II) was able to generate turn-on signals for spermine at a 25 µM concentration. To address this, the experimental setup of the assay was changed so that both 1 and spermine were kept constant at 25 µM and the concentration of Pb(II) was varied from 25–2500 µM (1–100 equivalents relative to 1). It was observed that once the Pb(II) concentration reached 500 µM (a 20-fold excess relative to 1), a turn-on signal was generated. Hence, this three-component system was successfully shown to allow lower detection limits of analyte to be engineered by introducing higher concentrations of metal cofactor.

4. Conclusion

A new fluorescence chemosensing system for the detection of polyamine analytes in neutral aqueous solvent has been identified through high-throughput screening assays. Using a dicarboxylated ethynylarene molecule as the fluorophore, mixtures of Cd(II), Pb(II) and Zn(II) cations were shown to display varying patterns of ‘turn-on’ responses for biogenic and non-biogenic polyamines. General polyamine features impacting signal generation are an increasing number of amine groups and the presence of propylene over ethylene units separating amine groups. It is believed that the selectivity of these systems is imparted by subtle differences in chelating interactions between metal cation and polyamine. The three-component nature of these sensors complicates discernment of the exact binding mechanism leading to signal generation, but affords the ability to engineer lowered detection limits by increasing the ratio of metal mediator relative to ethynylarene fluorophore. Future studies will continue to probe the details of molecular events leading to signal generation in this system and will evaluate the application of this sensing platform towards additional small molecule analytes of interest.

Figure 4.

Ratiometric analysis for assays of 1 (50 µM) with 0–5 equiv of Pb(II) in the presence of 2.5 mM and 25 mM polyamine analytes 2–10 in pH = 7.6 aqueous solution.

Figure 5.

Ratiometric analysis for assays of 1 (50 µM) with 0–5 equiv of Zn(II) in the presence of 2.5 mM and 25 mM polyamine analytes 2–10 in pH = 7.6 aqueous solution.

Highlights.

Dicarboxylated ethynylarene solutions with Cd(II), Pb(II) or Zn(II) were studied

High throughput screening measured polyamine-induced fluorescence perturbation

Bathochromic shifts and intensification of fluorescence defined a ‘turn-on’ signal

Signaling was generated from ethynylarene, metal cation and polyamine association

Pb(II) system discriminates spermine from spermidine, cadaverine and putrescine

Acknowledgements

This publication was made possible by grants from the National Center for Research Resources (5P20RR016469) and the National Institute for General Medical Science (NIGMS) (8P20GM103427), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and its contents are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NIGMS or NIH.

Biographies

James T. Fletcher received his B.S. from the University of Nebraska, Lincoln in 1996 and his Ph.D. from the University of Pennsylvania in 2001. After completing a postdoctoral fellowship at The Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, CA, he started an independent research career in 2004 at Creighton University in Omaha, NE where he is currently an Associate Professor in the Department of Chemistry. His research interests include the development of new small molecule chemosensors and metal chelators, as well as studying tandem click chemistry reactions.

Brent S. Bruck received his B.S. from Creighton University in 2013. He is currently attending medical school at Washington University in St. Louis, MO.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Cohen SS. A Guide to Polyamines. USA: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Russell DH. Increased polyamine concentrations in uring of human cancer patients. Nat. New Biol. 1971;233:144–145. doi: 10.1038/newbio233144a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Russell DH, Durie BGM. Polyamines as Biochemical Markers of Normal and Malignant Growth. New York: Raven Press; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bachrach U. Polyamines and cancer: Minireview article. Amino Acids. 2004;26:307–309. doi: 10.1007/s00726-004-0076-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Teti D, Visalli M, McNair H. Analysis of polyamines as markers of (patho)physiological conditions. J. Chromatog. B. 2002;781:107–149. doi: 10.1016/s1570-0232(02)00669-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morgan DML. Polyamine Protocols. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kawakita M, Hiramatsu K. Diacetylated derivatives of spermine and spermidine as novel promising tumor markers. J. Biochem. 2006;139:315–322. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvj068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ozdestan O, Uren A. A method for benzoyl chloride derivatization of biogenic amines for high performance liquid chromatography. Talanta. 2009;78:1321–1326. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paik MJ, Kuon D, Cho J, Kim KR. Altered urinary polyamine patterns of cancer patients under acupuncture therapy. Amino Acids. 2009;37:407–413. doi: 10.1007/s00726-008-0169-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fujita K, Nagatsu T, Shinpo K, Maruta K, Teradaira R, Nakamura M. Improved analysis for urinary polyamines by use of high-voltage electrophoresis on paper. Clin. Chem. 1980;26:1577–1582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steiner MS, Meier RJ, Spangler C, Duerkop A, Wolfbeis OS. Determination of biogenic amines by capillary electrophoresis using a chameleon type of fluorescent stain. Microchim. Acta. 2009;167:259–266. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tanima D, Imamura Y, Kawabata T, Tsubaki K. Development of highly sensitive and selective molecules for detection of spermidine and spermine. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2009;7:4689–4694. doi: 10.1039/b909682e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee B, Scopelliti R, Severin K. A molecular probe for the optical detection of biogenic amines. Chem. Commun. 2011;47:9639–9641. doi: 10.1039/c1cc13604f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ikeda M, Yoshii T, Matsui T, Tanida T, Komatsu H, Hamachi I. Montmorillonite-supramolecular hydrogel hybrid for fluorocolorimetric sensing of polyamines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:1670–1673. doi: 10.1021/ja109692z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakamura M, Sanji T, Tanaka M. Fluorometric sensing of biogenic amines with aggregation-induced emission-active tetraphenylethenes. Chem.-Eur. J. 2011;17:5344–5349. doi: 10.1002/chem.201003285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Satrijo A, Swager TM. Anthryl-doped conjugated polyelectrolytes as aggregation-based sensors for nonquenching multicationic analytes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:16020–16028. doi: 10.1021/ja075573r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maynor MS, Nelson TL, O'Sullivan C, Lavigne JJ. A food freshness sensor using the multistate response from analyte-induced aggregation of a cross-reactive poly(thiophene) Org. Lett. 2007;9:3217–3220. doi: 10.1021/ol071065a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chow CF, Lam MHW, Wong WY. Design and synthesis of heterobimetallic Ru(II)-Ln(III) complexes as chemodosimetric ensembles for the detection of biogenic amine odorants. Anal. Chem. 2013;85:8246–8253. doi: 10.1021/ac401513j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim TI, Park J, Kim Y. A gold nanoparticle-based fluorescence turn-on probe for highly sensitive detection of polyamines. Chem.-Eur. J. 2011;17:11978–11982. doi: 10.1002/chem.201102060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jornet-Martinez N, Gonzalez-Bejar M, Moliner-Martinez Y, Campins-Falco P, Perez-Prieto J. Sensitive and selective plasmonic assay for spermine as biomarker in human urine. Anal. Chem. 2014;86:1347–1351. doi: 10.1021/ac404165j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kostereli Z, Severin K. Fluorescence sensing of spermine with a frustrated amphiphile. Chem. Commun. 2012;48:5841–5843. doi: 10.1039/c2cc32228e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Domaille DW, Que EL, Chang CJ. Synthetic fluorescent sensors for studying the cell biology of metals. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2008;4:168–175. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schaferling M. The art of fluorescence imaging with chemical sensors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:3532–3554. doi: 10.1002/anie.201105459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vendrell M, Zhai D, Er JC, Chang YT. Combinatorial strategies in fluorescent probe development. Chem. Rev. 2012;112:4391–4420. doi: 10.1021/cr200355j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu J, Liu W, Ge J, Zhang H, Wang P. New sensing mechanisms for design of fluorescent chemosensors emerging in recent years. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011;40:3483–3495. doi: 10.1039/c0cs00224k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fang AG, Mello JV, Finney NS. Exploiting the versatile assembly of arylpyridine fluorophores for wavelength tuning and SAR. Org. Lett. 2003;5:967–970. doi: 10.1021/ol0272287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fang AG, Mello JV, Finney NS. Structural studies of biarylpyridines fluorophores lead to the identification of promising long wavelength emitters for use in fluorescent chemosensors. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:11075–11087. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malashikhin SA, Baldridge KK, Finney NS. Efficient discovery of fluorescent chemosensors based on a biarylpyridine scaffold. Org. Lett. 2010;12:940–943. doi: 10.1021/ol902902m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McFarland SA, Finney NS. Fluorescent chemosensors based on conformational restriction of a biaryl fluorophore. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:1260–1261. doi: 10.1021/ja005701a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mello JV, Finney NS. Dual-signaling fluorescent chemosensors based on conformational restriction and induced charge transfer. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2001;40:1536–1538. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20010417)40:8<1536::AID-ANIE1536>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McFarland SA, Finney NS. Fluorescent signaling based on control of excited state dynamics. Biarylacetylene fluorescent chemosensors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:1178–1179. doi: 10.1021/ja017309i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Christensen JT, Fletcher JT. 2-(1,2,3-Triazol-4-yl)pyridine-containing ethynylarenes as selective 'turn-on' flourescent chemosensors for Ni(II) Tetrahedron Lett. 2014;55:4612–4615. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2014.06.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carroll CN, Berryman OB, Johnson CA, Zakharov LN, Haley MM, Johnson DW. Protonation activates anion binding and alters binding selectivity in new inherently fluorescent 2,6-bis(2-anilinoethynyl)pyridine bisureas. Chem. Commun. 2009:2520–2522. doi: 10.1039/b901643k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carroll CN, Naleway JJ, Haley MM, Johnson DW. Arylethynyl receptors for neutral molecules and anions: emerging applications in cellular imaging. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010;39:3875–3888. doi: 10.1039/b926231h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gunnlaugsson T, Glynn M, Tocci GM, Kruger PE, Pfeffer FM. Anion recognition and sensing in organic and aqueous media using luminescent and colorimetric sensors. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2006;250:3094–3117. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martinez-Manez R, Sancenon F. Fluorogenic and chromogenic chemosensors and reagents for anions. Chem. Rev. 2003;103:4419–4476. doi: 10.1021/cr010421e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carroll CN, Coombs BA, McClintock SP, Johnson CA, Berryman OB, Johnson DW, et al. Anion-dependent fluorescence in bis(anilinoethynyl)pyridine derivatives: switchable ONOFF and OFF-ON responses. Chem. Commun. 2011;47:5539–5541. doi: 10.1039/c1cc10947b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sandanayake K, Nakashima K, Shinkai S. Specific Recognition of disaccharides by trans- 3,3'-stilbenediboronic acid - rigidification and fluorescence enhancement of the stilbene skeleton upon formation of a sugar-stilbene macrocycle. Chem. J. Soc.-Chem. Commun. 1994:1621–1622. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Takeuchi M, Mizuno T, Shinmori H, Nakashima M, Shinkai S. Fluorescence and CD spectroscopic sugar sensing by a cyanine-appended diboronic acid probe. Tetrahedron. 1996;52:1195–1204. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takeuchi M, Yoda S, Imada T, Shinkai S. Chiral sugar recognition by a diboronic-acid-appended binaphthyl derivative through rigidification effect. Tetrahedron. 1997;53:8335–8348. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fletcher JT, Bruck BS, Deever DE. Dicarboxylated ethynylarenes as buffer-dependent chemosensors for Cd(II), Pb(II), and Zn(II) Tetrahedron Lett. 2013;54:5366–5369. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2013.07.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Williams ATR, Winfield SA, Miller JN. Relative fluorescence quantum yields using a computer-controlled luminescence spectrometer. Analyst. 1983;108:1067–1071. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rusakowicz R, Testa AC. 2-Aminopyridine as a standard for low-wavelength spectrofluorimetry. Phys. J. Chem. 1968;72:2680–2681. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lindoy LF. The Chemistry of Macrocyclic Ligand Complexes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lindoy LF. Tailoring macrocycles for metal ion binding. Pure Appl. Chem. 1997;69:2179–2186. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bradshaw JS. Aza-crown Macrocycles. New York: Wiley; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hancock RD, Martell AE. Ligand design for selective complexation of metal-ions in aqueous-solution. Chem. Rev. 1989;89:1875–1914. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bencini A, Bianchi A, Garcia-Espana E, Micheloni M, Ramirez JA. Proton coordination by polyamine compounds in aqueous solution. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1999;188:97–156. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bazzicalupi C, Bencini A, Biagini S, Bianchi A, Faggi E, Giorgi C et al. Polyamine receptors containing dipyridine or phenanthroline units: clues for the design of fluorescent chemosensors for metal ions. Chem.-Eur. J. 2009;15:8049–8063. doi: 10.1002/chem.200900283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Finney NS. Combinatorial discovery of fluorophores and fluorescent probes. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2006;10:238–245. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]