Abstract

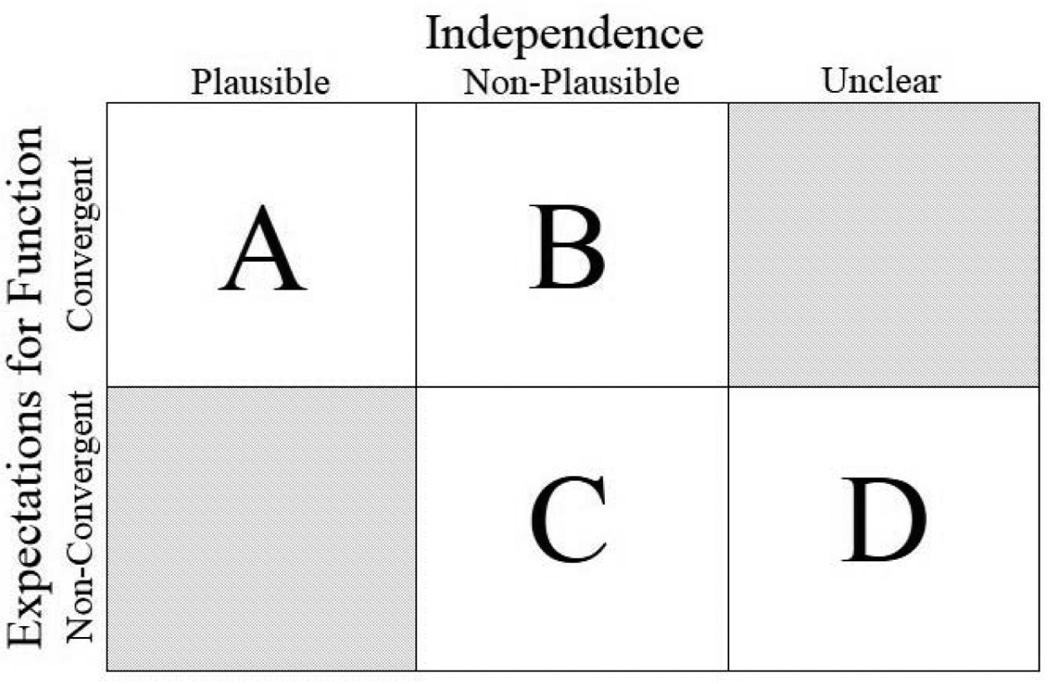

Survivors of childhood brain tumors face many obstacles to living independently as adults. Causes for lack of independence are multifactorial and generally are investigated in terms of physical, cognitive, and psychosocial treatment–related sequelae. Little is known, however, about the role of expectation for survivors’ function. From a mixed–methods study including qualitative interviews and quantitative measures from 40 caregiver–survivor dyads, we compared the data within and across dyads, identifying four distinct narrative profiles: (A) convergent expectations about an optimistic future, (B) convergent expectations about a less optimistic future, (C) non–convergent expectations about a less optimistic future, and (D) non–convergent expectations about an unclear future. Dyads both do well and/or struggle in systematically different manners in each profile. These profiles may inform the design of interventions to be tested in future research and help clinicians to assist families in defining, (re–)negotiating, and reaching their expectations of function and independence.

Keywords: United States, narrative profiles, childhood brain tumor, family research, mixed methods

Introduction

Due to improved treatment, the overall, relative 5-year survival of children diagnosed with brain tumors is about 75% (Howlader et al., 2013). Childhood brain tumor survivors who reach adulthood, however, are far less likely than survivors of other childhood cancers to live independently as adults (Kunin-Batson et al., 2011). The consequences for survivors who do not attain independent living are immense. Moreover, caring for children well beyond what normative expectations encompass raises significant concerns related to the roles of family members and their obligations to care for their (adult) children. Within most North American communities, the primary caregiver for (adult) children needing care is typically a parent and generally the mother. Thus, the survivorship experience of young adult survivors of childhood brain tumors must take into account not only the survivor but also the caregiver and family contexts, as well as their interactions with clinicians and others in the community (e.g. hospital, school).

While little is known about parents of children with brain tumors and their interactions with clinicians, more is known about parents of children in early acute care for traumatic brain injury. These parents perceive discussions with clinicians as framed specifically around the children’s medical needs and the needs of the healthcare community, without being supportive of parents and families (Roscigno, Savage, Grant, & Philipsen, 2013). Medico–scientific communication, including prognostication, requires a nuanced approach. Clinicians are trained to communicate with this approach, but families are not always able to hear their nuanced message. In addition, some families of children with chronic conditions need more condition–focused information while others need information about the condition that is contextualized and addresses how management of the condition can be integrated into family life (Knafl et al., 2011). Families, even if able to understand medico–scientific communication, may not be able to hear the nuance at times of life threat (e.g., at the time of diagnosis or during treatment) or even during follow–up visits in survivorship, as many survivors of childhood brain tumors and their parents experience post–traumatic stress symptoms (Bruce, Gumley, Isham, Fearon, & Phipps, 2011). From this complex of interactions, expectations about present and future life evolve.

We know little about the expectations, defined here as including presumed beliefs and attitudes about present and future functionality (physical, cognitive, and psychosocial components) and independence (primary focus on ability to live independently), of mothers of childhood brain tumor survivors who may not be able to live independently as adults. In addition, we do not know how these expectations may influence caregiving decisions. Mothers usually make countless decisions for their children, generally until the decision making at some point shifts to the (now older) healthy child. Mothers of children in cancer treatment or survivorship similarly make countless decisions, although shifting decision making may not follow prognostic recovery patterns for those with sufficient neurologic injury, and these decisions have been shown to be influenced by expectations for function, independence, and the future in general (Lucas, 2014). Indeed, recent work has focused on the powerful stories of parents’ experiences after the diagnosis of a childhood brain tumor, including struggles in survivorship related to treatment-related sequelae (Anonymous Three, 2014; Carlson, 2014; Rocker, 2014; Scheumann, 2014). To better understand the expectations of families for the function and independence of the survivor of a childhood brain tumor, we focus here on the interplay between the caregiver and survivor dyads.

This focus on dyads was guided by a socio-ecological model adapted from Kazak (1989) and colleagues (1995). Socioecological models include multidimensional interactions that are nonlinear and/or reciprocal and can include complex characteristics such as the importance of dyads and transition (Eckenwiler, 2007; Kazak, 1992) across all spheres of the life. In our socioecological model, we shift the central focus from the “child” to the dyad of mother–caregiver and adolescent/young adult (AYA)–survivor. While this is not a typical socioecological representation and is not meant to exclude other family members, the focus is purposeful in producing richer relational narratives that expand the bioethical and clinical sensitivity regarding issues of caregiving, childhood chronic conditions, transition, and intellectual/competency challenges.

Caregiving is now understood as an emerging public health issue (Talley & Crews, 2007). Our purpose is to identify and describe narrative profiles of expectations and understandings of function and potential independence for the survivor among dyads of mother–caregivers and AYA–survivors of a childhood brain tumor. Researchers can use these profiles to identify and tailor interventions based on the particular profile features. Such interventions can be used by clinicians to better assist families in defining, (re–)negotiating, and reaching their expectations of function and independence. To identify these narratives, we take an innovative approach that combines multiple variables with qualitative themes that arose during interviews with two family members (survivor and mother/female caretaker). This combination approach may provide more comprehensive narratives of the dyads (Knafl et al., 2013).

Methods

The findings presented here are from participants from Phase Two of a two–phase investigation of mother–caregiver competence and demand and AYA–survivor quality–of–life. We obtained ethical approval for this secondary analysis from the University of Pennsylvania. In the original study, all participants provided written informed consent or assent. The primary study team de–identified transcripts and other data.

Participants

Participants were recruited from a large mid–Atlantic children’s hospital from 2008–2011 for a two–phase (quantitative followed by qualitative) study. Of the 186 mother–caregivers and 135 AYA–survivors that participated in Phase One, a purposive, criterion–based sample yielding maximum variability (Patton, 2002) was identified for participation in Phase Two, resulting in 40 matched English–speaking caregiver–survivor dyads. For inclusion, survivors had to be at least 5 years post–diagnosis, 2 years post–treatment cessation, currently aged 14 to 40 years, and residing in the same household as the primary caregiver. We excluded from participation in the study dyads that included caregivers younger than age 21; survivors married or living in a partnered relationship; or survivors diagnosed with a genetically–based cause of brain tumor (such as neurofibromatosis), intellectual disability, or developmental delay, prior to brain tumor diagnosis. In this analysis we include data (qualitative and quantitative) from only those 40 dyads participating in the second phase.

Data Collection and Preparation

Qualitative interviews

Caregivers and survivors participated in in–depth, semi–structured, face–to–face interviews in the family’s home, conducted simultaneously but separately in different rooms. JAD (PI of original study) performed caregiver interviews, and MSL performed survivor interviews. Digital recordings were professionally transcribed, de–identified, and checked for transcription errors before being loaded into the ATLAS.ti (Version 7) data software package.

Quantitative surveys and chart review

Up to one year before completion of the qualitative interviews, quantitative data were gathered from the caregivers (telephone interview) and clinicians (chart review) only. Data included in this analysis are demographics (caregiver and survivor age; survivor sex; time since diagnosis; tumor type and location; household income; survivor’s school/work status; and caregiver education and employment; see Table 1), two subscales from the Family Management Measure (FaMM) (Knafl et al., 2011), and clinician ratings of Treatment Intensity (TI) and Medical Sequelae (MS).

Table 1.

Caregiver and Survivor Characteristics (N = 40)

| Characteristic | M (SD) or Frequency | Range or Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Caregiver age | 52.18 (5.68) | 41–67 |

| Survivor age (in years) | 23.38 (4.90) | 15–37 |

| Time since diagnosis (in years) | 15.26 (5.80) | 7–27 |

| Survivor sex (M) | 25 | 62.5 |

| Caregiver partnered | 33 | 82.5 |

| Caregiver employed full-time | 23 | 57.5 |

| Caregiver education | ||

| High school graduate | 12 | 30.0 |

| Some college | 9 | 22.5 |

| College graduate or higher | 19 | 47.5 |

| Tumor type | ||

| Low grade glioma | 17 | 42.5 |

| Primitive neuroectodermal tumor | 13 | 32.5 |

| High grade glioma | 3 | 7.5 |

| Craniopharyngioma | 3 | 7.5 |

| Other | 4 | 10.0 |

| Tumor location | ||

| Posterior fossa | 20 | 50.0 |

| Cortex | 7 | 17.5 |

| Sellar | 6 | 15.0 |

| Pineal | 4 | 10.0 |

| Other | 3 | 7.5 |

| Survivor education/work | ||

| Currently not in school or working | 11 | 27.5 |

| In school | 12 | 30.0 |

| Working | 17 | 42.5 |

The FaMM is a validated, self–report measure of family process and disease management, answered on a 5–point Likert–type scale, with six subscales. Two relevant subscales are used: View of Condition Impact (VCI, α = .76) measures caregiver perception of the seriousness of conditions and implications for child and family, and Child’s Daily Life (CDL, α = .88) measures parental perception of the child having a more normal life (or not) despite the condition. Both subscales have adequate internal consistency and test–retest reliability and supported construct validity in other samples (Knafl et al., 2011).

The TI and MS scores are clinician–rated ordinal scores of treatment intensity regimen (Kazak et al., 2012; Werba et al., 2007) and medical late effects of cancer and treatment (Hobbie et al., 2000), respectively. These rating systems were adapted for this population and have excellent inter–rater reliability (Deatrick et al., 2013). Two clinicians extracted data from the survivor’s medical chart and independently provided the scores. TI ratings include: (1) minimal: resection only; (2) average: focal radiation and/or nonintensive chemotherapy; (3) moderate: moderate chemotherapy (with/without focal radiation but no craniospinal radiation); (4) intensive: craniospinal radiation (with/without moderate, nonintensive chemotherapy) or high dose chemotherapy with stem cell rescue; and (5) most intensive: craniospinal radiation and intensive chemotherapy with stem cell rescue. MS ratings include: (1) no limitations: no limitations of activity or special medical attention required; (2) mild restrictions: mild conditions that require some medical attention; (3) moderate restrictions: significant medical attention required on regular basis; and (4) severe restrictions: life threatening condition, unable to live independently.

Data Analysis

Our analysis centers on creation of narrative profiles for each case (caregiver–survivor dyad) using both qualitative and quantitative data, a strategy considered to reduce interpreter bias through the potential richness of the resulting data (Elliott, 2005; Tashakkori & Teddlie, 1998). We identify these comparative narrative profiles within family dyads (caregiver and survivor) as well as across all dyads in order to compare individual dyad and group perspectives.

Qualitative analysis

Using directed content analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005), MSL coded qualitative interviews, followed by a second close reading and coding by JAD. We developed guiding code lists, which were revised during data analysis to reflect the data and evolving analytic insights. After adding, editing, or eliminating coding categories, previously–coded interviews received a second read to adjust coding. Coded interviews were analyzed, and a case summary for each dyad was created.

Quantitative analysis

Descriptive statistics were compared for the demographics and subscales of the 40 dyads and did not differ from those in phase one of the original study. To facilitate the dyadic descriptive analysis, we then qualitized the quantitative data (Teddlie & Tashakkori, 2009). As the FaMM (VCI, CDL) is not normed, we divided the subscales into quartiles and descriptively assessed differences in CDL and VCI quartiles along with MS and TI ratings among the profiles (see Table 2) using SPSS (Version 21) and added quantitative data to the case summaries.

Table 2.

Caregiver and Clinician Variable and Quantile Scores

| Variable M (SD)* |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Profile | n | CDL | VCI | MS | TI |

| All | 40 | 2.65 (1.19) | 2.18 (0.76) | 2.50 (0.85) | 2.53 (1.32) |

| A | 15 | 1.80 (0.86) | 1.87 (0.74) | 2.13 (0.83) | 2.27 (1.28) |

| B | 8 | 3.38 (1.06) | 2.38 (0.74) | 2.50 (0.93) | 3.00 (1.41) |

| C | 9 | 3.56 (0.73) | 2.67 (0.50) | 3.00 (0.50) | 2.56 (1.42) |

| D | 8 | 2.50 (1.20) | 2.00 (0.82) | 2.63 (0.92) | 2.50 (1.31) |

Abbreviations: CDL = Family Management Measure (FaMM) Child’s Daily Life (1–4); VCI = FaMM View of Condition Impact (1–4); MS = Medical Sequelae Score (1–4); TI =Treatment Intensity Score (1–5).

Lower scores (MS, TI) indicate fewer medical sequelae and less intensive treatment. CDL and VCI quartile assignments are adjusted so that lower numbers indicate a more normal life despite the condition (CDL) and a view of a less serious condition and implications for family (VCI).

Combined analysis

We assembled qualitative and quantitative data from both caregiver and survivor case summaries into one spreadsheet matrix. Table 3 summarizes data from one case in order to illustrate the process of joining caregiver and survivor data (all participant names identified here are pseudonyms). Profiles were identified containing subthemes from each of the major themes (Creswell & Piano Clark, 2011; Elliott, 2005): expectations, function, independence, clinical information, and challenges. After adding demographic data to complete the within–case analyses, we then made comparisons across dyads to identify potential narrative profiles. Comparisons across dyads contributing to the construction of four narrative profiles include: (a) the interplay between caregiver and survivor regarding expectations and function; (b) the plausibility of the survivor’s independence in the future, as identified by caregiver (qualitative interview), survivor (qualitative interview), and clinician (MS); and (c) how the caregiver (CDL, VCI) and clinician (MS) ratings converged.

Table 3.

Sample Abbreviated Case (Barbara & Brittany, Profile A) Matrix

| Qualitative |

Quantitative |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expectations & Function |

Independence | Challenges | CDL | VCI | MS | |

| Barbara (C) | Satisfied S can do what S loves. Hopes BT never returns. Unsure of fertility. Few friends. | S finished master’s degree and has a job. | Concern for tumor recurrence. Insurance difficult. | 3 | 2 | |

| Brittany (S) | No concern for future health. Wants to be married with family. Sees own physical issues. Has boyfriend. | Graduated from master’s program. Has full-time job. Some financial support from C. | Her father died, but was with her during treatment. | 2 | ||

Abbreviations: CDL = Family Management Measure (FaMM) Child’s Daily Life (1–4); VCI = FaMM View of Condition Impact (1–4); MS = Medical Sequelae Score (1–4); S = Survivor; C = Caregiver; BT = brain tumor.

Rigor

While the clinician–rated MS scores guided the identification of survivor function, we relied on caregiver and survivor voices to validate or update documentation from the survivor’s medical chart. Our data sources included multiple perspectives: caregiver, survivor, and clinician, and we returned to the qualitative interviews throughout the analytic process. This ensured that our summaries of the dyads were consistent with the voices of the caregivers and survivors, which were our analytic guides.

Results

The dyads in this study are divided into four narrative profiles (see Figure 1) based on convergent or divergent understandings between caregiver and survivor and plausible, non–plausible, or unclear potential for the survivor to live independently. Convergence or divergence was determined through qualitative coding of the dyadic interviews. Level of projected independence was determined through an analysis of the interviews and CDL, VCI, MS, and whether or not the survivor is in school or working. Table 2 shows the cross–data validation of the profile formation. The four profiles are: (A) convergent expectations about an optimistic future, (B) convergent expectations about a less optimistic future, (C) non–convergent expectations about a less optimistic future, and (D) non–convergent expectations about an uncertain future. Below we present each profile in turn, highlighting representative stories through the lenses of expectations and function, independence, and challenges.

Figure 1.

Narrative Profiles of Expectation for Function and Independence

Narrative Profiles

Convergent expectations about an optimistic future (Profile A)

Fifteen of 40 dyads fall within Profile A, having convergent expectations and understandings of the survivor’s function or potential function, a plausible future independence for the survivor, and generally convergent quantitative results (meaning that the caregiver and clinician ratings align). These survivors and caregivers agree with each other and with clinicians about the future potential for the survivor to live independently. That is, the caregivers here consider these survivors to have a more normal life despite their condition and have less concern about the survivor’s condition than do those in the other profiles. Clinicians rated these survivors as having had less intensive treatment and less disruptive treatment–related medical sequelae than others. The survivors in these dyads have a slightly shorter time since diagnosis than those in other profiles, and, like Profile D, are slightly younger than those in Profiles B and C. All of the survivors with this profile are either in school (33%) or working (67%).

The stories

The survivors in these dyads have the greatest chances of being able to live independently. In some cases, the survivors have already demonstrated some ability to live independently. Barbara and her 25-year-old daughter, Brittany, represent one of the more successful dyads that participated in this study. At the age of 12 years, Brittany was diagnosed with a suprasellar low grade glioma (LGG) and treated with surgery and radiation. We met soon after she graduated from a combined undergraduate/graduate degree program and had just started an entry–level position working with children. Brittany told us that she does not think others treat her differently because of the brain tumor, but rather she treats others differently, in that “I do think it allows me to connect with the kids I’m working with.”

Robert, nearly 23 years old when we met, was 10 years old when he was diagnosed with a posterior fossa LGG and was also treated with surgery and radiation. Robert’s mother, Robin, has struggled with depression during her adult life. Robert stated that “when she’s up, she’s the greatest mom in the world, but, you know.” He works nights as a security supervisor and spends much of his free time with his infant son (the child and the child’s mother do not live with the survivor).

Expectations and function

Barbara and Brittany are both satisfied that Brittany is able to do what she loves, though Barbara expected Brittany to have more friends from school. While Brittany does talk about interacting with a few different groups of friends and mentions meeting her boyfriend at a New Year’s Eve party, she says of her mother that “we talk through everything together so we’re really, almost like, she’s my friend. My mom’s my friend.” This description of the caregiver–survivor relationship is common; while not all 40 relationships are described positively, they are all profoundly close.

Both Robin and Robert believe Robert’s tumor will recur, but they do not talk with each other about it. Robin does not want to cry in front of Robert, and Robert does not want to upset his mother. Robin recalls what clinicians told her about the effects of the tumor and treatment, that Robert “would never get nothing one hundred percent, and I was okay with that.” Robert’s understanding is similar: “One thing I probably think about a lot is how it was, where I came from. Even though I’m not there where I want to be, […] I’m a couple steps away from where I came from.”

Independence

Many of the survivors have completed undergraduate studies (n = 13), though often with substantial educational support. Of those completing undergraduate education, most have not been able to obtain jobs in their field, and a few were not working at all (see Table 4 for a summary of survivor education and work status). Brittany completed a master’s degree, however, and recently found a job with a rehabilitation organization providing care to children. While Brittany does receive some financial support from Barbara, both expect her to live on her own in the future.

Table 4.

Survivor Age and Education/Work Status

| Education/Work (%) |

Educational Status n (%) |

Undergraduate Completed n (%) |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Profile | n | Age M (SD) |

Time Since Dx M (SD) |

Neither | In School |

Working | In HS | No Univ. | Some Univ. |

Univ. Grad |

Beyond Univ. |

Job in Field |

Not Working |

| All | 40 |

23.4 (4.9) |

15.3 (5.8) |

27.5 | 30.0 | 42.5 | 7 (17.5) |

12 (30.0) |

8 (20.0) |

11 (27.5) |

2 (5.0) |

6 (38.5) |

2 (15.4) |

| A | 15 | 22.8 (3.3) |

13.6 (5.5) |

0 | 33.3 | 66.7 | 2 (13.3) |

1 (6.7) |

5 (33.3) |

5 (33.3) |

2 (13.3) |

4 (42.9) |

0 |

| B | 8 | 25.4 (6.2) |

15.2 (5.9) |

62.5 | 12.5 | 25.0 | 1 (12.5) |

3 (37.5) |

1 (12.5) |

3 (37.5) |

0 | 0 | 2 (66.7) |

| C | 9 | 23.2 (6.5) |

16.8 (5.3) |

55.6 | 33.3 | 11.1 | 2 (22.2) |

5 (55.6) |

1 (11.1) |

1 (11.1) |

0 | 0 | 0 |

| D | 8 | 22.8 (4.4) |

16.7 (7.0) |

12.5 | 37.5 | 50.0 | 2 (25.0) |

3 (37.5) |

1 (12.5) |

2 (25.0) |

0 | 2 (100) |

0 |

Abbreviations: Dx = Diagnosis; HS = High School; Univ. = University.

Robert works full-time as a supervisor of security and is considering returning to school to become a child advocate. He wants to be able to provide for his son, and both Robert and Robin see that as possible.

Challenges

Even with Profile A’s convergence of expectations, understanding of survivor function, and plausible independence, these dyads still face challenges. Brittany’s educational debt and low, entry–level salary make it difficult for her to move out on her own. She also struggles with weight, difficulties in peer relationships, and visual deficits, common treatment–related sequelae for suprasellar tumors. Although Brittany wants to try to have children someday, Barbara also brought up her potential infertility.

Both Robin and Robert have great fears of tumor recurrence, and they struggle daily with this as well as Robert’s difficulty with interpersonal relationships. Unlike in many of the other dyads, here the survivor is able to verbalize insights into his psychosocial challenges to a greater extent than the caregiver. Says Robert:

Mentally [and] emotionally it changed me. I have less tolerance now towards a lot of things. A lot of people just have anger issues because of it, temper problems. I’m not really much of a people person. I hate big crowds, you know? […] I was getting along with a lot of people. After that, it just stopped. […] If something happened [such as a disagreement], like, I’ll try to just get away. I don’t know how far. I just, I don’t care if he’s up the street, I just try to get away. My anger and my temper, it’s just really bad, honest. I can say the only reason why I don’t have a criminal record from it, because of it or anything, is because I’m able to control it, but it’s really, really bad. I get angry easily.

Robert started practicing martial arts to improve his difficulty with balance, a common treatment–related sequela of posterior fossa tumors, and this has also helped him to control his anger; he now practices daily.

Convergent expectations about a less optimistic future (Profile B)

Eight of 40 dyads fall into Profile B. Like those in Profile A, these dyads have convergent views on the expectations and understandings of the survivor’s function or potential future function. Unlike Profile A, however, in Profile B dyads the survivors’ future independence is implausible due to numerous threats. Caregivers here consider these survivors to have a less normal life because of their condition and have more concerns about the survivors’ condition than did those in Profiles A and D. Clinicians rated these survivors as having had the overall most intensive treatment and having more treatment–related sequelae than those in other profiles.

Profile B dyads agree that the future probably will not include independence for the survivor, and the caregivers here have greater concern about managing the survivors’ conditions. The majority of survivors (63%) are neither in school nor working; all have given up—at least for the foreseeable future—in looking for work or entering school. The survivors are the oldest, but not the furthest from diagnosis, within the sample (see Table 4); notably, the profiles do not differ greatly in terms of survivor mean age or time since diagnosis. The mean of 15.3 years since diagnosis for survivors in Profile B does indicate that these survivors have greater risk of potential sequelae from earlier treatment protocols that included higher radiation doses (Bouffet, Tabori, Huang, & Bartels, 2010).

The stories

Kimberly, almost 24 years old, was diagnosed with a primitive neuroectodermal tumor (PNET) in the posterior fossa at age 15 years; she was treated with surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation. Her mother, Karen, stopped working as a teacher to stay home with Kimberly when she lost her ability to perform activities of daily living (ADLs) after surgery. Karen and Kimberly have worked methodically every day, improving Kimberly’s ability to ambulate from wheelchair to walker to forearm crutches.

Patrick was on his way to an elite boarding school when he was diagnosed with a suprasellar craniopharyngioma at the age of 16 years. While he did finish high school, completed undergraduate degrees in neuroscience and music, and worked in a cancer research laboratory until it lost funding, he now has such profound stamina issues that he must nap several times per day and cannot work, although he does volunteer at church. Patricia, Patrick’s mother, was most concerned when:

Right before surgery they give you all the negatives: he could die, he could be blind, he could, you know. One of the worst things that we had was […] it could totally change his personality. And that was like devastating to me. And then when he came out and he was cracking jokes and doing everything I thought alright, that’s fine.

Patrick wants to give back to his mother but knows that will never be possible.

Expectations and function

Karen pushes Kimberly to work harder, because she thinks that Kimberly can do more. Kimberly has proven that through daily hard work she can improve her ambulation, bathe herself, and steady her voice with vocal/singing training. Karen recalls that “she tells me I’m her best friend and, but, you know, I’m her mother and a different generation. She needs somebody who’s young and, you know, more her age,” and Kimberly agrees; she wants more friends or to at least be able to be more social with the few friends she does have:

Sometimes like I think I just feel like real low […when] you go on [social media] and you see like all these pictures of your friends all like having, in college and places with a lot of their friends and there’s lots of pictures. And sometimes you feel sad, and I feel sad in a way about that and though, my mom, she just talks to me and then she says, she reminds me like just not to like dwell in the past. “You’re a different person now. And you know, just be happy with life. Like people need you, and don’t think about what others are doing.”

Karen concludes that “…this tumor left a horrible disability.”

Patrick also faces “a horrible disability” in his lack of stamina, which Patricia attributes as the primary cause of his decreased quality of life. Patrick recognizes each aspect of how his body has failed what he expected of it, and he has given up on any future potential intimacy because of it. He stated, “There’s no way I would be able to keep up with the demands and needs of another person when I can barely keep up with myself sometimes.” While Patrick does not have the energy for frequent social engagements, he is still sociable in many ways and enjoys using his education and work experience for “decoding medicalese” for members of a brain tumor email group.

Independence

Karen and Kimberly both know that Kimberly will probably not ever be able to have a job. Karen is unsure of any possible independence. While Kimberly wants to live on her own, she knows this is not yet possible as she relies so heavily on her mother for physical help with ADLs. She improves, but slowly. Karen did not grow up in the United States and wonders whether she is appropriately guiding Kimberly, because “the American culture is big on independence; […] are you making her independent enough to be able to live by herself? I can’t fathom that.”

Patricia is unsure what will happen when she is gone, but Patrick does not think he will—nor does he wish to—outlive his mother. Without the tumor he would be working now, but with the associated stamina difficulty he cannot hold a job. As such, Patrick thinks that not outliving his mother avoids the complications associated with needing to support himself when his primary caregiver no longer can.

Challenges

Karen does not see herself as old (she is 55 years), but thinks that it is most important to figure out how to make Kimberly financially secure. Even though they have said they are willing, Karen would not want her other daughters to have to give up their own freedom to care for Kimberly, who struggles with needing to be so dependent upon another person. “What if something happens to my husband and myself, you know. Those are young girls, her sisters, they have their own families, you know.” Kimberly also discusses her cognitive challenges. For example, she often cannot follow movies because the dialogue passes too quickly for her to process. Such challenges would make having a job difficult.

Lack of stamina impacts every aspect of Patrick’s life. He did have a job at a cancer research lab that accommodated for his resting requirements, but the lab lost funding and it is difficult to find a similar position. Patrick told us, “I look normal. There is not a massive sign that says, ‘This person had a brain tumor, this person is different,’ floating over my head. Sometimes that would be useful. It would save some explanation.” While Patricia is concerned about what will happen when she is gone, Patrick does not see himself living into his 50s. With his current quality of life he thinks that it is better this way; he does not see himself as depressed, but with a realistic outlook that is “depressing for a normal person.”

Non-convergent expectations about a less optimistic future (Profile C)

Dyads in Profile C (n = 9) appear to face the most extreme challenges. Views about expectations for function between caregiver and survivor are divergent, and independence is not plausible, or is at the least at risk from numerous threats. Like those in Profile B, these survivors face many threats to or have little plausibility for future independence. Different than Profile B, the caregivers and survivors identify different points of importance regarding expectations and/or disagree about what is important regarding function and independence. While not the oldest, these survivors are the furthest from diagnosis and have the most treatment–related sequelae, and more than half (56%) are not in school or work. The caregivers think the survivors, related to their conditions, have much less normal lives than do others (CDL), and the impact on family life (VCI) is similar to those in Profile B.

The stories

Irene worked for many years in special education and now consults to help 14 to 21–year–olds with disabilities transition into the adult world. However, she does not think it will be possible to transition her daughter, Isabella, who is now almost 24 years old. Isabella was diagnosed with a posterior fossa LGG at age 4 years and treated with surgery and chemotherapy; she had a second LGG infiltrating both posterior fossa and spinal cord at age 12 years and was treated with chemotherapy only. About her family she says, “They made me have as normal as possible life. They just treat me like anyone else. They don’t look at what I can’t do. They look at what I can do.”

At 11 years Scott was diagnosed with a posterior fossa PNET and treated with surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation. He is now 19 years old and out of high school. Susan, Scott’s mother, has familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP), as do all of Susan’s children, including Scott. FAP results in numerous polyp formations in the colon and a potential increased risk for brain tumors (Attard, Giglio, Koppula, Snyder, & Lynch, 2007), although the family and their clinicians were not aware of the predisposition until after the PNET diagnosis. In this family’s case, FAP ultimately requires total colectomy to avoid colon cancer. While the consequences of FAP are normative and manageable for this family, Scott’s PNET treatment–related sequelae are not. Susan has fear that she should not “…ever relax. Don’t be comfortable, […] because if you’re stressed already then you don’t have too far to go ‘cause you’re already at that level. If you get too comfortable that’s when things will happen.”

Expectations and function

Isabella and Scott are poignant examples of how most of these survivors in this profile struggle with their psychosocial function. While both Irene and Isabella see Isabella as very intelligent, Irene describes her as:

this person trapped inside a body. She wants that normalcy. Each time her brother goes to do something, he drives. She becomes angry. He went to college. She can go, but she knows that it will be so stressful. […] We finally figured out what causes her to have those meltdowns. We know what triggers it off. We have to remain very calm.

Isabella focuses her attention on her physical difficulties and understands that her “balance will never change.” She is frustrated with how this limits what she can do. She does volunteer at a hospital and enjoys interacting with patients and staff. Irene knows that this volunteer position helps to maintain Isabella’s social skills, and:

When she starts to feel sorry for herself, when she starts to get sad, that she wishes she could date, she wishes she could drive, she wishes her life was different, she wishes she could go out and do things like a “normal” person does, I sit her down and we reflect […], and she always knows there’s somebody who has it worse than we do.

When Scott has a hospital or surgical stay, he comes back “a little bit different every time. So we readjust to Scott.” Susan continues, “The strokes, they really, really hit [Scott] hard” both physically (he has left–sided hemiparesis) and psychologically. While he knows that he might fail, Scott generally wants to try new things before receiving help. He is not concerned about his future health, except that he specifically does not want to lose hearing or sight. He will talk openly with anyone, but he avoids in–person social interaction when possible. It’s not that he does not want to see friends, but the “…computer screen is easier for me and not as awkward.”

Independence

Irene has made Isabella “as independent as can be.” In her professional capacity, Irene would tell other parents, “‘At this age she should be living on her own and be independent.’ And Isabella would not do very well if she was in an apartment by herself.” Isabella is conflicted. She takes public transportation and she volunteers (under supervision) 24 hours per week. She would love to “just, you know, [be] living on my own and getting married, having a husband, a job, having no worries basically. But I do worry a lot because I know like it’s out of my control.”

Susan saw Scott as self–sufficient before his strokes. After he recently graduated from high school, she asked him, “‘Okay. Do you wanna get a job or do you wanna go to college?’ He’s like, ‘I wanna sit home and play on my computer.’” Susan is looking for a job for Scott, but he is not an active participant in this search. She tries in other ways to promote his ability to function independently:

I asked him the other day, “Do you know what medicines you’re taking?” “Well, whatever you tell me to take.” “No. You need to learn what…” And I tell him what type and how many times a day and all that, […] and a lot of times he’ll say, “That’s why I have you.”

Scott’s memory impairment prevented him from pursuing a goal of becoming a chef. While he has difficulty with independence in the life with his family, he told us:

I like playing on the computer ‘cause it’s— I’m not in the real world. I can do whatever I want kind of thing and there’s no consequences or anything. Well there is some but not as drastic as in real life. […] Like if you lose or something, you can just like resurrect yourself back to life and do it again. Usually I do things like if I die, I’ll do it again, the same thing, but I’ll find maybe this way will be easier. So it’s better. It’s not like so bad kind of thing. This is like I got unlimited lives. I can keep on trying kind of thing. So it’s good.

After the interview Scott mentioned that he prefers to play online games called “massively multiplayer online role playing games” (MMORPGs) because they allow him to interact with others, but through the computer. MMORPG group play usually consists of a “tank” (player who absorbs damage and prevents others from being attacked), three melee or ranged damage dealers, and one healer (player who heals those in the group that receive damage). In group play, he intentionally chooses not to be a healer because of the high repercussions that if he does not heal fast enough, all of the team members will die, and he will have let them down. While he has not yet, possibly, figured out independence in life, he does excel in the game.

Challenges

The challenges for Profile C families are embedded in the dyads’ different expectations and understandings of function and independence. These differences between survivor and caregiver are intensified because the survivors are likely not able to find employment and due to their occasional “meltdowns.” According to Irene, Isabella can be a challenge because she “does not fit the mold” and that “people are typically not able to see outside the box.” She wonders if it matters how much she prepares Isabella, because something could always happen. Furthermore:

[Isabella] doesn’t want to grow up. “I wish I was a little girl again.” That really, really bothers her. She’ll see a doll and she’ll say, “Oh Mom! I wish I could have this doll,” knowing she knows she can’t because it’s not appropriate.

Isabella identifies her challenges as they relate to her functional ability. She wanted to be a nurse, but school exhausted her too much; she wanted to be a personal care assistant, but she cannot handle the lifting that would be required.

Susan identifies two primary challenges. The first is expressed well in her above quote about not being able to ever relax, because “that’s when things will happen.” She also struggles with Scott’s psychological changes, especially when “he is angry and curses and is just a nasty person.” Scott struggles as well; he feels comfortable as an inpatient at the children’s hospital because, he says, “I feel normal here.” He is profoundly self–conscious and does not feel comfortable in the presence of other people. Susan wants him to try to find a job, which may assist him with some form of independent living; Scott is satisfied being supported by his mother and experiencing the independence available to him in online gaming worlds.

Non-convergent expectations about an uncertain future (Profile D)

The final profile contains dyads (n = 8) who either disagree or have competing understandings about the expectations and understandings of the survivor’s function or potential function; an unclear plausibility for future independence; and results on the CDL, VCI, and MS that span a range of possibilities. These caregivers and survivors do not agree on what is important, and at times they disagree with their clinicians. Generally these caregivers and survivors discuss different topics, and even when similar topics are indicated as important, they disagree about specifics. The survivors in these dyads may be able to live independently in the future, but are now struggling with the skills and tasks necessary to do so. These dyads have fewer distinguishing characteristics than do those in the other three profiles.

The stories

Emily, now almost 16 years old, was diagnosed with a temporal lobe LGG at 8 years and treated with surgery only. Her mother, Elaine, manages nearly every move Emily makes as a precaution against seizures, but this goes unacknowledged by Emily. Notably, Emily avoided or redirected many questions about her day–to–day life, especially when they referred to management of her health by adults.

At age 3 years, Ryan was diagnosed with a posterior fossa PNET and treated with surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation. Rebecca does not think that her son, now 28 years old, has the decision making ability or the cognitive control to live independently, though that is still their goal. Ryan works two part–time jobs, drives, often makes dinner, and is learning to manage his own money.

Expectations and function

At 16 years old, Emily is not yet taking her own medications, but Elaine plans to start working on this skill after the school year ends. She expects Emily to go to college and already has a plan to send medication reminders to Emily using SMS text messaging. Emily is unhappy with how seizures will disrupt her social relationships and force her to miss school. She finds school challenging enough without having to miss several days at a time because of an episode of seizures.

Rebecca finds it difficult that Ryan has working memory challenges, which causes disputes over household chores. Regarding his social function, Rebecca is not happy that:

Every girl he has of course he’s spending the money on, so as we said he’d never afford it if he gets married. It’s just the way it seems to be. So if we’re concerned, that’s probably one of our concerns, is we don’t want him to get married.

On his day off work Ryan meets up with his girlfriend of nine years, whom he met at the Special Olympics. They often go to Atlantic City, where Ryan plays slots but apparently does not win. Ryan has few local friends, Rebecca does not allow these friends into their home.

Independence

Emily does not discuss possible future independence, perhaps because she is still in high school. Elaine does think that Emily will be able to live on her own and will be able to emotionally engage with someone beyond herself. Elaine is unsure if the latter is a treatment–related sequela or a component of Emily’s development in adolescence, but does see this as a necessary progression toward being able to function on her own. Elaine expects that Emily will go to college, but the 16–year–old still has constant adult supervision because of her sequela–related seizure disorder.

Ryan does not make enough money to support himself and, prior to the Affordable Care Act, relied upon Rebecca for health insurance. She thinks there is a possibility that “he could survive with a little guidance from his brother for [Ryan’s] meds.” She stated that they work on his ability to be self–sufficient every day. On allowing him to use online banking and bill payment, she is “just not comfortable yet. It’s my hang–up, not his. He’d probably do just fine.” Ryan appears content where he is and does not have a strong desire to move out. He thinks he does very well: working hard, making dinners, and driving, though he has been in two car accidents.

Challenges

According to Emily, school, namely mathematics and social studies, is her only challenge, but Elaine has a long list. In addition to acting as caregiver for Emily, Elaine is also primary caregiver for her parents, who have dementia. Emily still sleeps in Elaine’s bed, and each seizure takes Emily out of school for a few days. Elaine’s husband takes all of his vacation time during Emily’s hospital stays, yet Emily still expects a family vacation. Emily wants to go out alone, but Elaine is not satisfied that Emily is safe without observation. Elaine feels a substantial responsibility, such that “when I do forget something, it’s like the end of the world for me.”

While Ryan is concerned primarily about not having local friends, Rebecca finds caregiving for a survivor of a childhood brain tumor to be “very, very challenging, because they [the family] really were never introduced to this kind of disability. It isn’t autism. It isn’t total deafness.” She struggled trying to identify what are the “normal” developmental issues versus Ryan’s treatment–related psychosocial sequelae and does not think there is any way to learn how to do this from a book.

Discussion

These four narrative profiles describe dyads containing survivors of a childhood brain tumor who have not begun to live independently of their female caregivers and offer a perspective of future life course from both perspectives. In only one profile (A) do both individuals agree that the survivor will be able to live independently. Shared expectations enables families, with the help of clinicians, to plan for the future. The consequences of non–shared expectations offer extensive challenges to clinicians and these particular families. These profiles offer opportunities for clinicians to directly tailor their communication with families to assist them with their decision–making. Some of the dyads share expectations; this is the often the case of dyads with survivors who are doing well and can reasonably be expected to live independently without substantial assistance. Others have identified contrasting views (Engelhardt, 2010) or management styles (Knafl et al., 2013) of families. Similar differences are evident here.

When survivors are within normative age ranges to live at home, both families and clinicians may fail to identify where there will be future challenges with independence. The survivors’ ages averaged around the age when children usually launch from the family home, which may also mask struggles for independence versus treatment–related sequelae. Profile A survivors are slightly younger; perhaps those who fit this profile and are older are more likely to be independent (and thus not qualify for inclusion in this study). Brittany’s educational debt and entry–level salary, however, is not unique to survivors of childhood brain tumors, as many young adults over the last several decades have progressively taken longer to transition to independent living (Settersten & Ray, 2010).

In Profile B dyads, while there is not much hope for independence, caregivers and survivors do agree that the survivor will need lifelong caregiving. These families need help in supporting their shared expectations and finding appropriate resources that will support the survivor while still under the care of the family, the survivor when the family can no longer provide care, and the family while they do provide care. The health of caregivers plays a major role in family life, including the status of family management and the survivor’s health (Deatrick et al., 2013).

Dyads in Profiles C and D present other challenges to both their families and healthcare providers. The survivors here either are unlikely to become independent of their caregivers or face numerous threats to their potential independence, and the dyads do not agree on expectations for the survivor about function and independence. While dyads in Profiles A and B were concordant about the meaning of “independence,” dyads in Profile C had apparent differences in what “independence” as a goal meant to either caregiver or survivor. For example, Susan wishes Scott would find a job, which might provide skills that could lead to independence; Scott, however, is content living under the care of his mother while exploring independence through online gaming. Both Profiles C and D need more study to identify the reasons for divergent or discrepant views and how to move past disagreement to help the survivor, caregiver, and family to access appropriate resources.

Communication between clinicians and families may contribute to within–dyad non–convergent views, as knowledge of the factors that contribute to the dyadic profiles—concordance of expectations and future independence—can guide how clinicians communicate with patients and families. Furthermore, how clinicians convey information in the clinic is important because that conveyance contributes to how families make decisions during survivorship. In this population, these decisions range from the seemingly simple (for example, one caregiver described having to decide whether to let her child cut up his own food at dinner because it takes the survivor too long) to the rather complex (one dyad discussing whether an implanted neural prosthesis would improve balance and tremor). Both simple and complex decisions have implications for outcomes, including potential survivor independence.

Profile A and B dyads do not disagree about what the future might hold for the family; as such, clinicians do not need to spend time helping these survivors and caregivers to each identify and reconcile differences in the others’ expectations. Clinicians may be able to most help those in Profiles A and B by applying problem–solving approaches after listening to the family’s goals. Clinician knowledge and resources can support survivors and parents to meet their goals for improved function and independence, as identified in the following examples. Brittany (Profile A) can be guided to seek fertility consultation, as appropriate. Kimberly’s (Profile B) family can be encouraged to pursue life planning, including future care planning for Kimberly. Patrick (Profile B), depending on his diminishing stamina, may be able to continue performing his own ADLs for years to come. Greater challenges are apparent with Profile C survivors, and family counseling to address intrafamilial communication and communication breakdown may be an appropriate first step. Irene and Isabella must be able to agree on expectations for the future—inclusive of what Isabella’s functional capacity is—in order to address what will happen when Irene can no longer provide care. More information is needed from Profile D dyads in order to identify their needs. The survivors’ potential is unclear, both from the understanding of the survivors and the caregivers.

Families live in uncontrolled environments. A family’s naturalistic setting constrains the range of accessible options and influences decisions made during survivorship. The use of a socioecological model to guide the narrative profile formation incorporates the context surrounding the participants’ stories and lives. Clinicians’ responsibility for communicating information to families extends to situating that information into the family’s social ecology. While pediatric clinicians may have more experience with the latter, many adult sub–specialty clinicians may not (Oeffinger, Nathan, & Kremer, 2008; Schwartz, Tuchman, Hobbie, & Ginsberg, 2011). As survivors of childhood brain tumors become young adults, their challenges in terms of transition readiness may exceed those of other survivor of childhood cancers.

Concerns surrounding transition readiness for these children and their families raise significant bioethical questions regarding not only the timing of the transition to adult health systems but also access to specialized supportive healthcare services for survivors of childhood brain tumors and their families. The consequences of delayed transition include challenges faced by families when the needs of the now chronologically–adult patient are not able to be well–addressed by pediatric specialists, clinicians (pediatric specialists addressing an adult body), and institutions (survivors aging out per either hospital guidelines or medical insurance restrictions).

Just as the caregivers and survivors in this study sometimes have divergent or discrepant understandings and expectations of the family’s situation, families and clinicians can have divergent and discrepant communication, understandings, and expectations. As the holders of specialized knowledge, clinicians are responsible for investigating potentially divergent or discrepant understandings and expectations between themselves and their patients and within patients’ families. The choices a caregiver makes for the survivor, family, and self are based upon her expectations and impact outcomes for survivor, family, and self. In this study, caregivers and survivors discussed challenges for survivor decision making, including navigating a possible future after the caregiver can no longer provide the decision making support and caregiving that she presently provides. Clinicians can play helpful roles for caregiver, survivor, and family decision making by initially addressing communication concerns.

Children who experience brain injury face significant challenges in making healthcare decisions. Prior to the age of legal majority, they are unable to make their own healthcare decisions. Once they reach the age of majority, their current and future cognitive abilities may be diminished. Respecting the voices of AYAs who survive brain injury, their differing levels of decisional capacity, and their efforts to participate in healthcare decision making requires more dialogue among pediatric bioethicists, clinicians, and the families of these children who seek recognition from the healthcare and greater community about changes they have experienced.

Several limitations warrant discussion. First, this secondary analysis only includes mother–caregivers, leaving out the voices of fathers, grandparents, other family members partaking in caregiving roles, as well as siblings. At the time of data collection, some survivors were still in school; including only those survivors who have left potentially protective school environments may better identify populations to target in the future. All caregivers have at least a high school education; future work should continue investigations into education and understanding of health literacy. Second, study design limitations do pose challenges when attempting to capture the broad socioecological contexts of families, and future work should seek methods that can capture these broad data. Even with these limitations, the profiles of expectations for function and independence identified here offer a foundation for future research with survivors of childhood brain tumors and their families.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by United States National Institutes of Health via the National Institute of Nursing Research (F31NR013091 [MSL], R01NR009651 [JAD]), the American Cancer Society (122552–DSCN–10-089 [MSL]), and the Oncology Nursing Society Foundation (Neuro–Oncology Nursing Grant [JAD]). The authors wish to thank the anonymous reviewers and editors for their thoughtful comments.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- Anonymous Three. Down the medical rabbit hole. Narrative Inquiry in Bioethics. 2014;4(1):18–21. doi: 10.1353/nib.2014.0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attard TM, Giglio P, Koppula S, Snyder C, Lynch HT. Brain tumors in individuals with familial adenomatous polyposis: a cancer registry experience and pooled case report analysis. Cancer. 2007;109(4):761–766. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouffet E, Tabori U, Huang A, Bartels U. Possibilities of new therapeutic strategies in brain tumors. Cancer Treatment Reviews. 2010;36(4):335–341. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2010.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce M, Gumley D, Isham L, Fearon P, Phipps K. Post–traumatic stress symptoms in childhood brain tumour survivors and their parents. Child: Care, Health and Development. 2011;37(2):244–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2010.01164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson J. The road to understanding and acceptance of the late effects of pediatric brain tumors and treatment. Narrative Inquiry in Bioethics. 2014;4(1):21–23. doi: 10.1353/nib.2014.0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW, Piano Clark VL. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. 2nd ed. Los Angeles: Sage; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Deatrick JA, Hobbie W, Ogle S, Fisher MJ, Barakat L, Hardie T, Ginsberg JP. Competence in caregivers of adolescent and young adult childhood brain tumor survivors. Health Psychology. 2013;33(10):1103–1112. doi: 10.1037/a0033756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckenwiler LA. An ecological framework for caregiving. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97(11):1930–1931. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.117390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott J. Using narrative in social research: Qualitative and quantitative approaches. London: Sage; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Engelhardt HT., Jr Beyond the best interests of children: four views of the family and of foundational disagreements regarding pediatric decision making. Journal of Medicine and Philosophy. 2010;35(5):499–517. doi: 10.1093/jmp/jhq042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobbie WL, Stuber M, Meeske K, Wissler K, Rourke MT, Ruccione K, Kazak AE. Symptoms of posttraumatic stress in young adult survivors of childhood cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2000;18(24):4060–4066. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.24.4060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Garshell J, Neyman N, Altekruse SE, Cronin KA. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2010, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh HE, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazak AE. Families of chronically ill children: A systems and socio–ecological model of adaptation and challenge. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1989;57(1):25–30. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.57.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazak AE. Family systems, social ecology, and chronic pediatric illness: Conceputal, methodological, and intervention issues. In: Akamatsu TJ, Parris MA, Stephens Hobfoll SE, Crowther JH, editors. Family health psychology. Washington, DC: Hemisphere Publishing Corporation; 1992. pp. 93–110. [Google Scholar]

- Kazak AE, Hocking MC, Ittenbach RF, Meadows AT, Hobbie W, DeRosa BW, Reilly A. A revision of the intensity of treatment rating scale: classifying the intensity of pediatric cancer treatment. Pediatric Blood & Cancer. 2012;59(1):96–99. doi: 10.1002/pbc.23320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazak AE, Segal-Andrews AM, Johnson K. Pediatric psychology research and practice: A family/systems approach. In: Roberts MC, editor. Handbook of pediatric psychology. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 1995. pp. 84–104. [Google Scholar]

- Knafl KA, Deatrick JA, Gallo A, Dixon J, Grey M, Knafl G, O'Malley J. Assessment of the psychometric properties of the Family Management Measure. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2011;36(5):494–505. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knafl KA, Deatrick JA, Knafl GJ, Gallo AM, Grey M, Dixon J. Patterns of family management of childhood chronic conditions and their relationship to child and family functioning. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2013;28(6):523–535. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2013.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunin–Batson A, Kadan–Lottick N, Zhu L, Cox C, Bordes–Edgar V, Srivastava DK, Krull KR. Predictors of independent living status in adult survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Pediatric Blood & Cancer. 2011;57(7):1197–1203. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas MS. Caregiver functional expectations for survivors of childhood brain tumors. (Doctoral dissertation) University of Pennsylvania; 2014. Retrieved from http://repository.upenn.edu/dissertations/AAI3622097(3622097) [Google Scholar]

- Oeffinger KC, Nathan PC, Kremer LC. Challenges after curative treatment for childhood cancer and long–term follow up of survivors. Pediatric Clinics of North America. 2008;55(1):251–273. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2007.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ. Qualitative research and evaluation methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rocker K. Over the years. Narrative Inquiry in Bioethics. 2014;4(1):25–27. doi: 10.1353/nib.2014.0021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roscigno CI, Savage TA, Grant G, Philipsen G. How healthcare provider talk with parents of children following severe traumatic brain injury is perceived in early acute care. Social Science & Medicine. 2013;90:32–39. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheumann L. Family, Friends, and Cancer: The Overwhelming Effects of Brain Cancer on a Child’s Life. Narrative Inquiry in Bioethics. 2014;4(1):23–25. doi: 10.1353/nib.2014.0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz LA, Tuchman LK, Hobbie WL, Ginsberg JP. A social–ecological model of readiness for transition to adult–oriented care for adolescents and young adults with chronic health conditions. Child: Care, Health & Development. 2011;37(6):883–895. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2011.01282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Settersten RA, Jr, Ray B. What’s going on with young people today? The long and twisting path to adulthood. The Future of Children. 2010;20(1):19–41. doi: 10.1353/foc.0.0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talley RC, Crews JE. Framing the public health of caregiving. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97(2):224–228. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.059337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tashakkori A, Teddlie C. Mixed methodology: Combining qualitative and quantitative approaches. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Teddlie C, Tashakkori A. Foundations of mixed methods research: Integrating quantitative and qualitative approaches in the social and behavioral sciences. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Werba BE, Hobbie W, Kazak AE, Ittenbach RE, Reilly AE, Meadows AT. Classifying the intensity of pediatric cancer treatment protocols: the intensity of treatment rating scale 2.0 (ITR–2) Pediatric Blood & Cancer. 2007;48(7):673–677. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]