Abstract

This study tested a dual-process model of self-control where the combination of high impulsivity (negative urgency – NU), weak reflective / control processes (low executive working memory capacity - E-WMC), and a cognitive load is associated with increased failures to inhibit pre-potent responses on a cued go/no-go task. Using a within-subjects design, a cognitive load with and without negative emotional load was implemented to consider situational factors. Results suggested that: (1) high NU was associated with low E-WMC; (2) low E-WMC significantly predicted more inhibitory control failures across tasks; and (3) there was a significant interaction of E-WMC and NU, revealing those with low E-WMC and high NU had the highest rates of inhibitory control failures on all conditions of the task. In conclusion, results suggest that while E-WMC is a strong independent predictor of inhibitory control, NU provides additional information for vulnerability to problems associated with self-regulation.

Keywords: Negative urgency, working memory, inhibitory control, self-regulation

1. INTRODUCTION

Those with high levels of trait impulsivity do not always show behavioral evidence of poor self-control (Wiers, Ames, Hofman, Krank, & Stacey, 2010). Dual-process models of self-regulation explain this phenomenon by positing that self-controlled behavior is the result of the interaction between impulsive and reflective processes (Smith & DeCoster, 2000). While trait impulsivity reflects general approach tendencies, reflective processes reflect those executive cognitive processes, such as executive working memory, that serve to check and modulate the approach tendencies. For instance, some evidence suggests that high working memory capacity may reduce the likelihood that someone with strong alcohol-related impulsive tendencies will actually drink excessively and develop alcohol problems (Thrush et al., 2008). Relevant for the current study of negative urgency (NU), these models also posit a role for situational factors, such as mood, that may weaken or enhance either process (Hofmann, Friese, & Strack, 2009). Using a dual-process model perspective, we investigated the association between NU (impulsive processes associated with negative mood), executive working memory capacity (E-WMC), negative mood, and a specific behavioral measure of inhibitory control, pre-potent response inhibition Friedman & Miyake, 2004). We hypothesize that NU will be associated with poor pre-potent response inhibition only for those with low E-WMC and that a negative mood induction will enhance this association.

Negative urgency (NU) is a facet of impulsivity that reflects a tendency to act rashly when experiencing negative affect (NA) (Whiteside & Lynam, 2001). In other words, negative mood is thought to enhance impulsive processes for those with high NU. There is some evidence that trait impulsivity is associated with low E-WMC (Gunn & Finn, 2013; Khurana et al., 2012), but this is not well studied and there are no reports of the association between NU and E-WMC. Likewise, there are not very many studies of self-report trait impulsivity and inhibitory motor control and the studies that do exist present mixed results. In some studies, NU is associated with poor pre-potent response inhibition on go/no go measures (Cyders & Coskunpinar, 2011; Gay et al., 2008), but not in others (Cyders & Coskunpinar, 2012). Another study reported an association between trait impulsivity and poor oculomotor inhibition and to some degree poor behavioral inhibition on a Stop Task for those with ADHD (Roberts, Fillmore & Milich, 2011). Enticott, Ogloff and Bradshaw (2006) report that measures of trait impulsivity are consistently associated with increased interference on the Stroop task, but less consistently associated with measures of poor inhibitory control on other behavioral measures. None of these studies examined the possible interaction between trait impulsivity and reflective / cognitive control processes, or in the case of NU, the interaction between NU, negative mood, and reflective processes. We hypothesize a more consistent and stronger association between NU and poor pre-potent response inhibition for those with lower E-WMC, especially after a negative mood induction.

We are particularly interested in E-WMC, as a reflective process, because it is consistently associated with decision making (Bechara & Martin, 2004; Endres, Donkin, & Finn, 2014; Finn, Gunn & Gerst, 2014; Shamosh et al., 2008) and it is considered a key reflective - control process critical for adaptive self-regulation and decision-making (Barkley, 2001, Barrett, Tugade, & Engle, 2004). Reduced E-WMC also has been associated with poor inhibitory control on a range of tasks (Kane, Bleckley, Conway, & Engle, 2001; Kane & Engle, 2003; Redick & Engle, 2006), including incentive learning go /no-go tasks (Endres, Donkin, & Finn, 2014; Redick, Cavlo, Gay, & Engle, 2011), but not the cued go/no-go task specifically.

The current study brings together these related concepts by testing the association between NU, E-WMC, and pre-potent response inhibition on the cued go/no-go task (Fillmore, Marczinski, & Bowman, 2005). Pre-potent response inhibition reflects the ability to suppress an automatic, primed response and is a specific domain of inhibitory control that is separable from the broader, more general construct of inhibitory control (Friedman & Miyake, 2004). In addition, we are interested in investigating the role of NU in these associations because it has not been studied with E-WMC and because it measures an impulsive disposition related to NA specifically.

To fully apply the dual-process model, we also consider situational factors that may enhance NU via a negative mood induction or compromise control processes via a cognitive load. Although NU posits poor self-control when experiencing negative affect, to our knowledge there have been no studies of the association between NU and measures of self-control after a mood induction. We also use a cognitive load because studies indicate that cognitive loads increase impulsive, disinhibited decision making on a range of tasks such as delay discounting tasks (Finn et al., 2014; Hinson, Jameson, & Whitney, 2003), incentivized go / no-go learning tasks (Endres et al., 2014), and the Iowa Gambling Task (Fridberg, Gerst, & Finn, 2013; Hinson, Jameson, & Whitney, 2002).

1.1. Specific Hypotheses

The primary hypothesis tested in this study is that NU will be associated with poor pre-potent response inhibition only for those with low E-WMC. We also hypothesized that the association between NU and response inhibition for those with low E-WMC will be enhanced by the cognitive load and negative mood induction.

2.0. METHOD

2.1. Participants

2.1.1. Sample Characteristics

The sample consisted of 86 young adults (M age = 21.5, SD = 4.3; 50 females). The sample was 72.1% European American, 12.8% African American, 3.5% Hispanic or Latino, and 11.6% Asian, Indian, or Middle Eastern. Eighty-five percent (n = 73) of the total sample were current undergraduate students at a large Midwestern university.

2.1.2. Recruitment

The sample was recruited from a larger study, where participants gave consent to be contacted for future studies conducted in the same laboratory. Participants were contacted by phone to determine study inclusion criteria including being between the ages of 18 and 30, able to read and speak English, having at least a 6th grade education, not currently taking any medications that seriously affect behavior (e.g. tranquilizers or epilepsy drugs), and no history of psychosis or head trauma.

2.2. Materials

2.2.1. Negative Urgency (NU)

Self-reported NU was assessed with the UPPS Impulsive Behavior Scale (UPPS-P; Lynam, Smith, Cyders, Fischer, & Whiteside, 2007). The UPPS-P is a 59-item self-report inventory that measures five impulsive personality traits, including NU. Items are assessed on a Likert scale from 1 (agree strongly) to 5 (disagree strongly). Higher scores denote higher levels of NU. This measure has revealed clear discriminant and convergent reliability. In addition, a multitrait, multimethod matrix analysis revealed good interrater reliability among the constructs (see Smith et al., 2007).

2.2.2. Executive working memory capacity (E-WMC)

Individual E-WMC was measured at the time of initial participation in the laboratory (before the being recruited for the present study) using the Operation Word Span test (OWS; Conway & Engle, 1994), a complex span task which has been found reliable in numerous studies (Conway et al., 2005). Although E-WMC was measured at a separate time point, measures of E-WMC have been shown to be stable over time (Conway et al., 2005; Klein & Fiss, 1999; Friedman & Miyake, 2004). This task requires the simultaneous use of attentional and maintenance resources. It requires confirming the accuracy of a mathematical operation while remembering a word (5+4 −1 =9 CAT). After a sequence of these operation word pairs (3 sets of each 2, 3, 4, & 5 word spans paired with mathematical operations) the participant is asked to recall, in order, the words as they were presented. Performance on this task is measured by the number of words recalled correctly.

2.2.3. Mood Ratings

The SAM MANIKIN valence scale (Bradley & Lang, 1994) was used to rate mood on a single dimensional Likert-scale. This scale uses a five-point measure to indicate current mood ranging from images of a smiling and happy face to a sad and frowning face (higher ratings indicating more negative mood) and displays good internal reliability in adults (Backs, da Silva, & Han, 2005; Lang, Bradley, & Cuthbert, 1999). Additionally, the negative scale (16 items) of the PANAS-State self-report measure was used to measure current NA, which has been found to have high internal reliability and to be stable across time (Crawford & Henry, 2004; Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988). Participants rate “the extent to which you are currently feeling this way” (very slightly or not at all to extremely) on a five-point Likert scale in response to a range of negative emotion words. An average score is calculated, higher scores indicating greater negative affect.

2.2.4. Mood Induction and Cognitive Load

At the beginning of the combined load condition, an autobiographical recall of a negative life event was elicited. In this procedure, participants were asked to “…recall a negative event in your life and reflect on it…”. They were instructed to write down as many details as possible and to “…really try to place yourself in the context of the event…” for 10 minutes. This method has been shown to effectively induce negative mood in individual procedures (Bless, Schwarz, & Wieland, 1996; Krauth-Gruber & Ric, 2000) as well as in comparison procedures and meta-analyses (Jallais & Gilet, 2010; Westermann, Spies, Stahl, & Hesse, 1996).

After completing the autobiographical recall, participants completed a condition of the cued go/ no-go task. In order to increase the salience of the mood induction procedure, negative valence words (i.e. suicide, torture, betray) were utilized in the combined condition for the cognitive load manipulation of the cued go/ no-go task. These words were selected from the Affective Norms for English Words (ANEW) catalog based on the valence ratings they received in a validation study (Bradley & Lang, 1999). Neutral valence words (i.e. wagon, square, bird) were used in the neutral version of the task (cognitive load only). A description of how these words were integrated into the task is in section 2.2.6.

2.2.5. Pre-potent Response inhibition

Modified versions of the cued go/ no-go task were administered to measure pre-potent response inhibition using E-Prime 2.0 (Psychology Software Tools, Pittsburgh, PA). The original version of the task creates a prepotency for behavioral responses based on recurrent specific cue and stimulus pairings (see Marczinski & Fillmore, 2003 for detailed description). The task presents a stimulus cue (stimulus orientation; vertical or horizontal rectangle) immediately followed by a response target that requires the participant to respond (go) or suppress (no-go). In the original version of this task, response targets are blue and green rectangles. Individual pre-potent response inhibition failures were measured by the total number of responses to no-go targets, also referred to as false alarm (FA) rate.

The present tasks were modified to increase cognitive load, first by adding a level of difficulty to the target response/ suppression distinction. Cue stimuli were maintained (vertical [go] and horizontal [no-go] rectangles), but cues were replaced with rectangle fills in which subjects were instructed to respond when the rectangle filled more than 50% and suppress when the rectangle was filled less than 50%. They were instructed to respond only based on this criteria, not on the orientation of the cue (which presented on the screen before the rectangle filled). The cues (vertical or horizontal rectangle) was presented for one of five equally presented stimulus onset asynchronies of 100, 200, 300, 400, and 500 ms. Each target was presented for 1000 ms, or was terminated after a response. As in the original version of the task, cue-stimulus pairings were manipulated to create a prepotency to respond to certain cues. Specifically, 80% of vertical cues were presented with go targets and 80% of the horizontal cues were presented with no-go targets. The no load version included 180 trials, and took about ten minutes to complete. Participants were reinforced for a correct response to a go cue with a screen displaying the reaction time in milliseconds in green font. Participants were informed of a FA with a screen displaying the word “Incorrect” in red font for 700 ms.

2.2.6. Cognitive Load Manipulation

The load versions of the task included the same reaction time trials as the no load task, but with a working memory load in the cognitive and combined load conditions, as well as a negative emotional load in the combined condition. The cognitive and combined versions of the task were administered in nine sets of 20 go/ no-go trials (a task total of 180), interrupted with nine memory word sets (cognitive load) ranging from three to five words, and took about 15 minutes to complete. Words were emotionally laden in the combined load (negative emotional load) and neutral for the cognitive load only. Words were presented individually in the center of the screen, for 1000ms, in large black font. Participants saw “???” in the center of the screen, prompting recall of the words at the end of a set. In these tasks, participants were asked to keep the memory word sets in mind while performing one set of go/ no-go task trials, and then recall them verbally in the correct order to a research assistant.

2.3. PROCEDURE

On the day of testing, all participants were consented and ensured to meet specific criteria: (a) no self-reported use of alcohol or drugs within the past 12 hours, (b) having at least 6 hours of sleep the night before, (c) having a breath alcohol level of 0.0%, (tested with a AlcoSensor IV (Intoximeters Inc., St. Louis, MO) and (d) not experiencing withdrawal symptoms or feeling ill.

Each participant completed all three versions of the cued go/ no-go task in counterbalanced order (no order effects were detected, ps >.05). Participants were administered mood ratings at the beginning of the study and between conditions. Condition included the autobiographical recall (combined load only), the appropriate version of cued go/ no-go task, and a mood rating (PANAS and SAM). Participants took 10-15 minute breaks between each condition. After all three versions of the task were completed, participants were asked to complete the UPPS-P (Lynam et al., 2007). Participants were paid $10/hour of testing, an on-time bonus of $10, and a performance bonus of $5 (this reward was meant to serve as performance motivation on the task).

2.4. Data Analysis

SPSS version 19.0 (SPSS, Inc., 2010) was used to analyze the data. Data analysis was organized into two segments, a manipulation check and hypothesis testing.

The manipulation check analyses assessed: (i) the effectiveness of the mood induction procedure to increase NA, and (ii) whether the modified cued go/no-go task resulted in the similar effects as previously validated versions (Fillmore, et al., 2005; Marczinski & Fillmore, 2003; Miller, Schaffer, & Hackley, 1991). Specifically, these analyses were conducted to confirm that go cues paired with no-go targets would result in the highest rates of FAs.

The hypothesis testing analyses assessed: (i) whether the combined condition (cognitive and emotional load) would lead to the highest FA rates; (ii) the associations between NU and E-WMC, as well as NU and E-WMC with FA rates; and (iii) the interaction of high NU by low E-WMC to predict higher FA rates. A multiple regression model with the full data set (all three conditions) to assess for the main effects of condition, E-WMC, NU, and the NU by E-WMC interaction, all entered at step one. The interaction terms was created after centering both the NU and E-WMC continuous variables. When conducted for each condition separately, E-WMC, NU were entered in the first step of the regression analysis and the interaction term was entered in the second step. Post hoc simple slopes analyses were conducted to further reveal interaction effects. Continuous variable (NU, WM, and NU X WM) were standardized for these analyses.

3.0. RESULTS

3.1. Manipulation Checks

3.1.1. Mood induction

Table 1 presents means and standard deviations for both mood ratings. Paired sample t-tests revealed that negative mood ratings were significantly higher in the combined compared with baseline condition on both the SAM MANIKIN t(85) = −4.98, p < .001, d= .61 and PANAS measures, t(85) = −4.02, p < .001, d= .41. Negative mood ratings were also higher in the combined load compared to the cognitive load condition, for the SAM: t(83)= −4.13, p < .001, d= .43; and PANAS: t(83)= −4.49, p < .001, d= .41. Furthermore, no significant differences in negative mood ratings were seen between the baseline and cognitive load conditions, for the SAM: t(83)= − 1.35, p = .18; nor the PANAS: t (83)= 0.07, p =.94.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Mood Ratings in each Condition

| Baseline | Cognitive Load | Combined Load | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

|

|

|||

| PANAS | 19.53 (3.7) | 19.50(3.8) | 21.49(5.7) |

| SAM | 2.00 (.55) | 2.10(.65) | 2.41(.77) |

Note. PANAS-negative scale (Watson, et al., 1988) and SAM (Bradley & Lang, 1994) means and standard deviations are presented for administration at baseline and after both the cognitive load and combined load conditions were completed.

3.1.2. Modified cued go/no-go task

Paired samples t-tests revealed total FAs across tasks were significantly higher for no-go trials paired with go cues (M = 22.99) than with no-go cues (M = 5.10), t(85)= 11.35, p <.001. These results were consistent when each task was examined separately as well (all ps < .001), confirming go cues were an effective primer for FAs.

3.2. Hypothesis Testing

3.2.1. NU, E-WMC, and FA rate

Table 2 presents the correlations between NU, E-WMC, and total FA rates in each condition of the cued go/no-go task. E-WMC was negatively associated with and NU (r = −.258, p < .05) and FA rate in the Combined condition (r = −.365, p < .01), the No load condition (r = −.336, p < .01) and the Cognitive load condition (r = −.328, p < .01). However, NU was not associated with FA rate in any condition.

Table 2.

Bivariate Correlations among NU, E-WMC, and FA Rate

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | M(SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. NU | - | −.258* | .167 | .195 | .193 | 2.37(.66) |

| 2. E-WMC | - | −.365** | −.336** | −.328** | 40.27(10.70) | |

| 3. FA Combined | - | .891** | .821** | 9.73(7.63) | ||

| 4. FA No load | - | .867** | 9.0 (7.16) | |||

| 5. FA Cognitive | - | 9.36(8.32) | ||||

Note. NU = Negative urgency; UPPS Impulsive Behavior Scale (UPPS-P; Lynam, et al., 2001); E-WMC = Executive working memory capacity; Operation Word Span test (OWS; Conway & Engle, 1994); FA combined = false alarm under combined load (cognitive and emotional load); FA no load = false alarm rate under no load; FA cognitive = false alarm rate under cognitive load only; FA rates are summed for each condition;

p <.05;

p <.01.

Multiple regression was used to test the main effects of task condition, NU, E-WMC, and their interaction on total FA rate across tasks. The analysis revealed a significant main effect of E-WMC, (β = −.21, p <.001), but not NU (β = .04, p =.495), and a significant NU by E-WMC interaction (β = −.42, p < .001). There was no main effect of condition on FA rate (β = .04, p =.47). In addition, analyses of each separate task condition revealed the same significant main effects of E-WMC (No load: β = −.21, p < .05; Cognitive load: β = −.15, p < .05; Combined load: β = −.24, p < .05) and NU by E-WMC interactions (No load: β = −.34, p < .001; Cognitive load: β = −.48, p < .001; Combined load: β = −.43, p < .001).

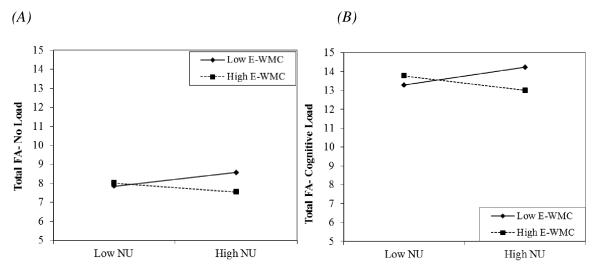

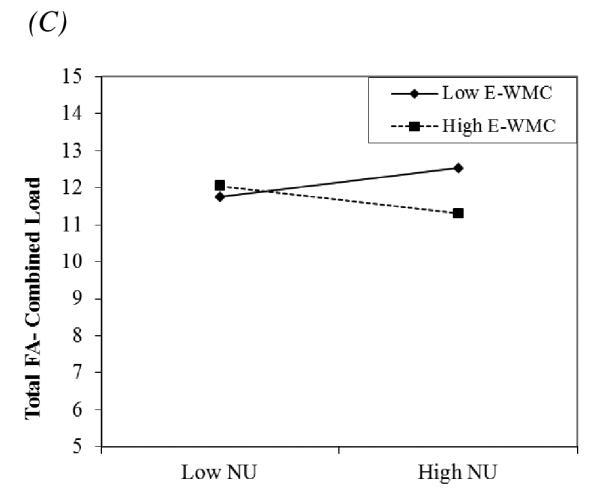

Tests of simple main effects in the E-WMC by NU interaction revealed a significant main effect of NU on FA rate for those low in E-WMC. Simple slopes for the association between NU and FA rate in each condition were tested for low (−1SD below the mean), moderate (mean), and high (+1 SD above the mean) levels of E-WMC. Each of these analyses (each condition) revealed a significant negative association between NU and E-WMC, revealing higher NU was associated with more FAs for those with low E-WMC (No load: β = .36, p < .01; Cognitive Load: β = .47, p < .001; Combined load: β = .40, p < .01) compared to moderate (No load: β = −.21, p < .05; Cognitive Load: β = −.18, p = .06; Combined load: β = −.24, p < .05) or higher (No load: β = −.24, p = .108; Cognitive Load: β = −.38, p < .01; Combined load: β = −.37, p = .01) levels of E-WMC. Figure 1 displays the simple slopes of this interaction in the no load (PANEL A), cognitive load (PANEL B), and combined load (PANEL C).

Figure 1.

Interaction of Negative Urgency and Executive Working Memory Capacity on False Alarm Rate

Note. The interaction effects (NUxE-WMC) for mean FA rate are displayed for each condition of the task: (A) No load; (B) Cognitive Load; (C) Combined Load.

3.2.2. Effect of Cognitive Load and Mood Induction on FA rate

Repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) revealed no significant differences in FA rate between task conditions F (1, 85) = 2.34, p = .130. In addition, tests of differences in correlations between task conditions, revealed that neither NU nor E-WMC differed in their association with FA rate between task conditions (ps > .24); thus there was no support for the hypothesis that either a cognitive load or the combination of cognitive load and emotion induction moderated the association between NU and inhibitory control.

4.0. DISCUSSION

The overarching goal of this study was to investigate the dual-process model hypothesis that NU would be more strongly associated with poor pre-potent response inhibition for those with low E-WMC and that a negative mood induction and a cognitive load would enhance this association for those with low E-WMC. The results conformed our primary hypothesis. NU was significantly associated with higher FA rates (i.e., poor pre-potent response inhibition) only for those with low E-WMC. However, the negative mood induction and the cognitive load did not affect the association between NU and pre-potent response inhibition. The results indicated that NU also was associated with lower E-WMC, which is consistent with studies of the association between global self-report measures of impulsivity and E-WMC (Gunn & Finn, 2013; Khurana et al., 2012).

The finding that NU is associated with higher FA rates only for those with low E-WMC is similar to other studies reporting that drug specific impulsive processes are associated increased substance use only for those with low working memory capacity (Grenard et al., 2008; Thrush et al., 2007, 2008). Although Grenard et al and Thrush et al used refined measures of impulsive tendencies specific to substance use, while we employed a trait measure of a specific dimension of impulsivity, these studies demonstrate the key role that E-WMC plays in behavioral regulation and modulating impulsive tendencies. The finding that low E-WMC exacerbates impulsive tendencies suggests that interventions that target deficits in working memory capacity, such as working memory training, may be useful in treating those high in NU or impulsive tendencies in general. In addition, the finding that NU is negatively associated with E-WMC adds to the growing literature of the association between impulsive personality traits and reduced executive function (Gunn & Finn, 2013; Khurana et al., 2012; Nigg, 2000) and suggests that a key process in impulsive behavior is a difficulty controlling attention during the deliberative process in decision-making.

The analyses revealed no significant effects of either the cognitive load or the combination of cognitive and emotional load. Although previous studies report that a working memory load increases impulsive, disinhibited decision making on a number of different decision tasks (Endres et al., 2014; Finn et al., 2014; Fridberg et al., 2013; Hinson et al., 2002; 2003), one possible reason for the lack of effect of these manipulations is that the cognitive load used here was not as demanding as those used in previous studies. Although we expected negative emotional load to be more taxing, a more demanding cognitive load might have been more effective in taxing working memory capacity. In addition, although our analyses show that the mood induction did significantly increase negative affect, the degree to which it represented a significant load, or a realistic, motivationally significant experience of negative affect is difficult to know. The context is artificial and the level of negative affect may have not been extreme enough to adequately activate the impulsive – affective processes central to NU. Therefore, we cannot fully explain these results and provide several recommendations for future studies.

This study was not without limitations. First, our sample consisted of mostly white young adult undergraduate students, which limits the generalizability of the results. Also, it is unclear whether the emotion induction procedure increased negative affect enough to represent a significant load. Further work should apply more rigorous situational variations to test whether similar manipulations of emotional and cognitive capacity result in more drastic self-regulation failure. More specifically, future studies may employ a between-subjects design, which could more thoroughly induce negative mood with audio or visual stimuli. Using a between subjects design would allow each condition more time to induce mood and remove the possibility of trickle over effects to other conditions (i.e. cognitive load only). As noted above, the cognitive load may not have taxed available working memory capacity enough to compromise E-WMC. Similarly, the negative mood induction may not have resulted in a motivationally significant, or realistic, increase in negative affect, and, thus, may not have been sufficient to engender impulsive responding in those high in NU. Future studies should use more taxing working memory loads and explore approaches to induce negative affect that is relevant or motivationally significant.

In summary, we applied a dual-process model of self-regulation to assess whether E-WMC, as well as situational factors, such as a cognitive load and negative emotion, moderated the association between NU and inhibitory motor control. The results provide convincing evidence that NU is associated with poor response inhibition only for those with low levels of E-WMC. Similarly, E-WMC was more strongly associated with poor pre-potent response inhibition for those high in NU. This work suggests that E-WMC has a central role in self-regulation and moderates impulsive tendencies. Given our results provide further evidence for the robust role that low E-WMC plays in poor self-regulation, research on the management and improvement of E-WMC can potentially shed some light on how one might target deficits in E-WMC in the treatment of disorders characterized by impulsive behavior.

High NU was significantly associated with lower eWMC.

Low eWMC predicted more false alarms on the cued go/ no-go task.

A significant interaction between high NU and low eWMC predicted more false alarms.

Combined cognitive and emotional load did not significantly increase false alarms.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by National Institutes of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism grant R01 AA13650 to Peter. R. Finn and training grant fellowships to Rachel Gunn from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism training grant fellowship, T32 AA07642.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

5.0. REFERENCES

- Backs RW, da Silva SP, Han K. A comparison of younger and older adults’ self-assessment manikin ratings of affective pictures. Experimental aging research. 2005;31:421–440. doi: 10.1080/03610730500206808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA. The executive functions and self-regulation: An evolutionary neuropsychological perspective. Neuropsychology Review. 2001;11:1–29. doi: 10.1023/a:1009085417776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett LF, Tugade MM, Engle RW. Individual differences in working memory capacity and dual-process theories of the mind. Psychological bulletin. 2004;130:553–573. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.4.553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechara A, Martin EM. Impaired decision making related to working memory deficits in individuals with substance addictions. Neuropsychology. 2004;18:152–162. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.18.1.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bless H, Schwarz N, Wieland R. Mood and the impact of category membership and individuating information. European Journal of Social Psychology. 1996;26:935–959. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley MM, Lang PJ. Measuring emotion: the self-assessment manikin and the semantic differential. Journal of behavior therapy and experimental psychiatry. 1994;25:49–59. doi: 10.1016/0005-7916(94)90063-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley MM, Lang PJ. The Center for Research in Psychophysiology. University of Florida; 1999. Affective norms for English words (ANEW): Instruction manual and affective ratings. Technical Report C-1. [Google Scholar]

- Castellanos-Ryan N, Rubia K, Conrod PJ. Response inhibition and reward response bias mediate the predictive relationships between impulsivity and sensation seeking and common and unique variance in conduct disorder and substance misuse. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2011;35:140–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloninger CR. A systematic method for clinical description and classification of personality variants: a proposal. Archives of general psychiatry. 1987;44:573–588. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800180093014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway AR, Engle RW. Working memory and retrieval: A resource-dependent inhibition model. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 1994;123:354–373. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.123.4.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway AR, Kane MJ, Bunting MF, Hambrick DZ, Wilhelm O, Engle RW. Working memory span tasks: A methodological review and user’s guide. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2005;12:769–786. doi: 10.3758/bf03196772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford JR, Henry JD. The Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS): Construct validity, measurement properties and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2004;43:245–265. doi: 10.1348/0144665031752934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Coskunpinar A. Measurement of constructs using self-report and behavioral lab tasks: Is there overlap in nomothetic span and construct representation for impulsivity? Clinical Psychology Review. 2011;31:965–982. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Coskunpinar A. The relationship between self-report and lab task conceptualizations of impulsivity. Journal of Research in Personality. 2012;46:121–124. [Google Scholar]

- Dick DM, Smith G, Olausson P, Mitchell SH, Leeman RF, O’Malley SS, Sher K. Review: understanding the construct of impulsivity and its relationship to alcohol use disorders. Addiction biology. 2010;15:217–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2009.00190.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endres M, Donkin C, Finn PR. An information processing / associative learning account of behavioral disinhibition in externalizing psychopathology. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2014;22:122–132. doi: 10.1037/a0035166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enticott PG, Ogloff JR, Bradshaw JL. Associations between laboratory measures of executive inhibitory control and self-reported impulsivity. Personality and Individual Differences. 2006;41:285–294. [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck HJ, Eysenck SBG. Manual of the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire. Hodder & Stoughton; London: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Fillmore MT, Marczinski CA, Bowman AM. Acute tolerance to alcohol effects on inhibitory and activational mechanisms of behavioral control. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:663–672. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn PR. Motivation, working memory, and decision making: A cognitive-motivational theory of personality vulnerability to alcoholism. Behavioral and Cognitive Neuroscience Reviews. 2002;1:183–205. doi: 10.1177/1534582302001003001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn PR, Gunn RL, Gerst KR. The Effects of a Working Memory Load on Delay Discounting in Those with Externalizing Psychopathology. Clinical Psychological Science. 2014 doi: 10.1177/2167702614542279. doi:10.1177/2167702614542279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fridberg DJ, Gerst KR, Finn PR. Effects of working memory load, a history of conduct disorder, and sex on decision making in substance dependent individuals. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2013;133:654–660. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman NP, Miyake A. The relations among inhibition and interference control functions: a latent-variable analysis. Journal of experimental psychology: General. 2004;133:101–135. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.133.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gay P, Rochat L, Billieux J, d’Acremont M, Van der Linden M. Heterogeneous inhibition processes involved in different facets of self-reported impulsivity: Evidence from a community sample. Acta Psychologica. 2008;129:332–339. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray JA. Explorations in temperament. Springer; US: 1991. The neuropsychology of temperament; pp. 105–128. [Google Scholar]

- Grenard JL, Ames SL, Wiers RW, Thrush C, Sussman S, Stacy AW. Working memory capacity moderates the predictive effects of drug-related associations on substance use. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22:426–432. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.3.426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunn RL, Finn PR. Impulsivity partially mediates the association between reduced working memory capacity and alcohol problems. Alcohol. 2013;47:3–8. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinson J, Jameson T, Whitney P. Somatic markers, working memory, and decision making. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience. 2002;2:341–353. doi: 10.3758/cabn.2.4.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinson JM, Jameson TL, Whitney P. Impulsive decision making and working memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2003;29:298–306. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.29.2.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann W, Friese M, Strack F. Impulse and self-control from a dual-systems perspective. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2009;4:162–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2009.01116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows. Version 19.0 IBM Corp.; Armonk, NY: Released 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Jallais C, Gilet AL. Inducing changes in arousal and valence: Comparison of two mood induction procedures. Behavior research methods. 2010;42:318–325. doi: 10.3758/BRM.42.1.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane MJ, Engle RW. Working-memory capacity and the control of attention: the contributions of goal neglect, response competition, and task set to Stroop interference. Journal of experimental psychology: General. 2003;132:47–70. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.132.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane MJ, Bleckley MK, Conway AR, Engle RW. A controlled-attention view of working-memory capacity. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2001;130:169–183. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.130.2.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khurana A, Romer D, Betancourt LM, Brodsky NL, Giannetta JM, Hurt H. Working memory ability predicts trajectories of early alcohol use in adolescents: the mediational role of impulsivity. Addiction. 2012;108.3:506–515. doi: 10.1111/add.12001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein K, Fiss WH. The reliability and stability of the Turner and Engle working memory task. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers. 1999;31:429–432. doi: 10.3758/bf03200722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krauth-Gruber S, Ric F. Affect and Stereotypic Thinking: A Test of the Mood and General Knowledge Model. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2000;26:1587–1597. [Google Scholar]

- Lang PJ, Bradley MM, Cuthbert BN. International affective picture system (IAPS): Technical manual and affective ratings. 1999.

- Lynam D, Smith GT, Cyders MA, Fischer S, Whiteside SA. The UPPSP: A multidimensional measure of risk for impulsive behavior. Unpublished technical report. 2007.

- Marczinski CA, Fillmore MT. Preresponse cues reduce the impairing effects of alcohol on the execution and suppression of responses. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2003;11:110–117. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.11.1.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller J, Schäffer R, Hackley SA. Effects of preliminary information in a go versus no-go task. Acta psychologica. 1991;76:241–292. doi: 10.1016/0001-6918(91)90022-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigg JT. On inhibition/disinhibition in developmental psychopathology: views from cognitive and personality psychology and a working inhibition taxonomy. Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126:220. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.2.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redick TS, Calvo A, Gay CE, Engle RW. Working memory capacity and go/no-go task performance: Selective effects of updating, maintenance, and inhibition. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2011;37:308–324. doi: 10.1037/a0022216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redick TS, Engle RW. Working memory capacity and attention network test performance. Applied Cognitive Psychology. 2006;20:713–721. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts W, Fillmore MT, Milich R. Linking impulsivity and inhibitory control using manual and oculomotor response inhibition tasks. Acta psychologica. 2011;138:419–428. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamosh NA, DeYoung CG, Green AE, Reis DL, Johnson MR, Conway ARA, Engle RW, Braver TS, Gray JR. Individual Differences in Delay Discounting: Relation to Intelligence, Working Memory, and Anterior Prefrontal Cortex. Psychological Science. 2008;19(9):904–911. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith ER, DeCoster J. Dual-process models in social and cognitive psychology: Conceptual integration and links to underlying memory systems. Personality and social psychology review. 2000;4:108–131. [Google Scholar]

- Smith GT, Fischer S, Cyders MA, Annus AM, Spillane NS, McCarthy DM. On the validity and utility of discriminating among impulsivity-like traits. Assessment. 2007;14:155–170. doi: 10.1177/1073191106295527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thrush C, Wiers RW, Ames SL, Grenard J, Sussman S, Stacy AW. Apples and oranges? Comparing indirect measures of alcohol-related cognition predicting alcohol use in at-risk adolescents. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2007;21:587–591. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.4.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thrush C, Wiers RW, Ames SL, Grenard J, Sussman S, Stacy AW. Interactions between implicit and explicit cognition and working memory capacity in the prediction of alcohol use in at-risk adolescents. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;94:116–124. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54:1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiers RW, Ames SL, Hofman W, Krank M, Stacey AW. Impulsivity, Impulsive and reflective processes and the development of alcohol use and misuse in adolescents and young adults. Frontiers in Psychology. 2010;1:1–12. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2010.00144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westermann R, Spies K, Stahl G, Hesse FW. Relative effectiveness and validity of mood induction procedures: A meta-analysis. European Journal of Social Psychology. 1996;26:557–580. [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside SP, Lynam DR. The Five Factor Model and impulsivity: using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;30:669–689. [Google Scholar]