Quality rating and improvement systems (QRIS) have become a popular policy strategy for improving the quality of child care settings in an effort to bolster children’s school readiness skills and to help close the achievement gap between lower- and higher-income children. QRIS have been designed to serve as a state’s overall ECE accountability system and are largely hinged on a multidimensional assessment of child care program quality (Schaack, Tarrant, Boller, & Tout, 2012). Drawing on decades of research, states have constructed QRIS to measure and improve aspects of child care settings commonly associated with children’s positive cognitive and social development (Zellman& Perlman, 2008).

Although the specific criteria for rating child care centers vary across states, QRIS indicators include structural quality indicators such as classroom ratios, staff education and specialized training, and their years of experience (Malone, Kirby, Caronongan, Tout, & Boller, 2011). Structural quality features are easily monitored and can be regulated by state child care licensing or other policy levers, but are believed to be only distally related to children’s outcomes (NICHD Early Child Care Research Network (ECCRN), 2002). Structural quality is assumed to provide the conditions that facilitate the implementation of developmentally appropriate teaching and care giving practices (e.g., process quality) that are associated with more favorable child outcomes.

In contrast, process quality variables are more directly related to children’s outcomes and measure children’s actual experiences within the early care and education settings (NICHD ECCRN, 2002).However, process quality indicators are more costly to measure because they require direct observations, and cannot be controlled by policy as easily. Due to costs, QRIS are primarily composed of structural quality indicators, but almost all include an assessment of the classroom environment that captures aspects of process quality in a global way (Malone et al., 2011). Currently, the most common measure of preschool-aged classrooms’ global process quality used in states’ QRIS is the Early Childhood Environment Rating Scale-Revised (ECERS-R; Harms, Clifford, & Cryer, 2005), with all but one state including the measure in their rating rubric (Malone et al., 2011). The ECERS-R assesses aspects of classrooms that include: their space and furnishings, the personal care routines children experience, how teachers’ promote children’s language and reasoning skills, the materials and activities in which children engage, the interactions between teachers and children, the overall daily schedule and routines, and how teachers communicate with parents and the center policies that support staff.

Within QRIS measurement approaches, state policymakers set thresholds on structural and process quality indicators used in their QRIS, which are then used to derive an overall quality or star rating for a program. Quality assessments and the thresholds set on them are designed to serve a number of functions that are expected to improve the overall quality of child care available in a state. QRIS-related coaches use quality ratings to guide on-site support activities with teachers and to target the content of professional development for teachers and administrators toward areas that assist in meeting higher quality levels (Smith, Schneider, & Kreader, 2010). In addition, many states place high stakes on quality ratings as a strategy for incentivizing improvement. For example, quality ratings are frequently used to allow or restrict a program access to additional services and funding streams, to award programs with different levels of reimbursement for children receiving child care subsidies, and to award bonuses to teaching staff (Schaack et al., 2012).

The thresholds set on quality measures play a central role in organizing QRIS and the services and benefits provided to child care programs, but the current literature has provided policymakers with very little empirical guidance about the existence of thresholds. Instead, QRIS evaluations to date have primarily focused on whether programs participating in the QRIS have made gains in quality as measured by the rating system or on QRIS implementation processes (Tout, Zaslow, Halle, & Forry, 2009; Zellman & Fiene, 2012).

The paucity of research on thresholds appears to stem from the field’s heavy reliance on linear methods, which has largely produced a body of evidence suggesting that the better the quality, the better the child outcomes (Loeb, Fuller, Kagan, & Carrol, 2004; Vandell, 2004). While it is reasonable to expect that higher process quality is related to better child outcomes, and that higher structural quality is related to better process quality, it is also reasonable to expect that there may be a minimum level of quality that needs to be reached before better outcomes are manifested. Correspondingly, there may also be a point at which higher quality is only marginally related to improvements in outcomes. Identification of these baseline and ceiling thresholds, respectively, can help policymakers and funders make decisions about how to invest their limited dollars. For example, policymakers may elect to initially invest funding toward helping programs meet at least a minimum threshold in which better outcomes are realized, or elect to limit the funding toward programs that have reached ceiling thresholds on the measures used in the QRIS where minimal returns on investment would be expected.

The purpose of this study is to examine whether there are baseline and ceiling thresholds on the multiple quality measures included within one state’s QRIS. Namely, we examine whether there are thresholds within (a) the ECERS-R in relation to children’s cognitive and social outcomes; and (b)teachers’ credentials and classroom ratios in relation to the ECERS-R.

Previous Research on Thresholds in Childcare Quality Indicators

Recently, a small body of research has begun to explore whether there are non-linear relationships between process quality measures and children’s developmental outcomes that could inform the existence of potentially meaningful thresholds(Zaslow, Anderson, Redd, Wessel, Tarullo, & Burchinal, 2010). In a study of public pre-kindergarten programs, Burchinal, Kainz, and Cai (2011) used both linear and quadratic terms and found evidence of a significant curvilinear relationship between the Classroom Scoring Assessment System (CLASS; Pianta, La Paro, & Hamre, 2004), and children’s social and academic achievement. Improvements to children’s outcomes were observed only once quality reached a certain threshold, with the associations between literacy skills and quality strongest within the upper ranges of the quality scores.

Burchinal, Vandergrift, Pianta, and Mashburn (2010) used piecewise regression to identify specific thresholds on the CLASS related to children’s academic, language, and social skills. They found evidence of threshold effects on both instructional quality and emotional climate subscales, such that instructional quality was more strongly related to expressive language, reading, and math skills in moderate-to-high quality classrooms than in low-quality classrooms. Emotional climate was also more positively predictive of social competence and more negatively predictive of behavioral problems in high-quality classrooms than in low-to-moderate quality classrooms.

Using data from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study-Birth Cohort, Setodji, Le, and Schaack (2013) identified thresholds on the 7-point Infant Toddler Environment Rating Scale (ITERS) relative to toddlers’ cognitive development. Departing from piecewise regression techniques in which the analyst determines a priori the thresholds to test, Setodji et al. (2013) used generalized additive modeling (GAM) to identify thresholds that were informed by the empirical relationship between the ITERS and the Bayley’s Scale of Mental Development. They found that the relationship between ITERS and cognitive development was significantly positive within the ITERS score range of 3.8 and 4.6, but null outside of this range.

Hypothesized Thresholds in Quality Indicators

Expected thresholds on the ECERS-R

Based on the construction of the ECERS-R and its underlying theories of development and learning, we hypothesize that there may be different thresholds for children’s cognitive outcomes than for children’s socio-emotional outcomes. With respect to cognitive outcomes, our hypotheses regarding thresholds are informed by various theories about children’s development. Constructivist theories of learning contend that children develop conceptual knowledge through their active exploration and manipulation of their environments. Through this exploration, children are provided with opportunities to differentiate elements of their environment and build categorical knowledge (Piaget, 1952). Social constructivist theories of development also argue that social interaction is at the heart of the learning process (Vygotsky, 1979). Within the context of child care, teachers of young children serve as important social learning partners and work within individual children’s zones of proximal development to scaffold their experiences and help children attend to the environment, differentiate elements, problem solve, and hear and practice using language. Attachment theory posits that in order for children to actively explore their worlds and engage with adults in learning, they must have trust and security in their teachers, which occurs as a result of responsive and positive care giving (Howes & Spieker, 2008).

The ECERS-R was designed to reflect these prominent developmental theories. While there are some items that focus on promoting positive child-teacher interactions that promote secure teacher attachments and interactions that facilitate more academic-oriented learning at the lower end of the ECERS-R scale, the majority of items clustered at the low- and mid-range of the ECERS-R focus on ensuring that the daily schedule and physical environment is structured in a manner that allows children adequate time and access to a variety of learning materials for exploration (Moore, 1994). In contrast, items clustered at the higher end of the ECERS-R tend to focus more on teacher behaviors and processes, and assess teachers’ active engagement with individual children to promote learning, security-enhancing teacher-child interactions, and the facilitation of positive peer relationships and social skills (Moore, 1994).

Given the way that the ECERS-R was constructed, we hypothesize there will be two thresholds on the ECERS-R with respect to cognitive outcomes. We hypothesize a baseline threshold located in the mid-range of the ECERS-R, where children are believed to have adequate access to ample learning materials and to positive teacher interactions, which may allow children to use their teachers as a secure base for exploration and learning (Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, 1979). We also hypothesize a second threshold located at the upper end of the ECERS-R scale, where teachers are more purposefully facilitating children’s learning and providing children with opportunities to hear and practice language through their engagement with children. However, because the ECERS-R was designed as a measure of global quality and not specifically as a measure of instructional quality, we believe there also may be a leveling-off effect, where beyond a certain threshold, higher scores on the ECERS-R will no longer be related to better cognitive and language development.

With respect to children’s socio-emotional outcomes, our hypotheses about thresholds are informed by prior research that has repeatedly found that consistently supportive teacher-child interactions are positively associated with children’s social and emotional development (Mashburnet al., 2008). Children who have experienced positive and responsive care are thought to be able to use their teachers as co-regulators of their emotions, allowing children to learn how to manage their arousal, control their impulses, thus promoting feelings of competency and independence (Birch & Ladd, 1997; Howes, Matheson, & Hamilton, 1994). Such consistently sensitive and responsive teachers also serve as a model for empathetic and prosocial interactions, enabling children to have more harmonious relationships with others (Howes & Spieker, 2008). These types of care giving practices are assessed by items clustered at the higher end of the ECERS-R. Consequently, we hypothesize that in relation to children’s social and emotional development, there will be one threshold, located at the higher end of the ECERS-R scale.

Expected thresholds on the structural quality indicators

Structural indicators of quality are believed to be indirectly linked to child outcomes through process indicators of quality. This mediation framework has been empirically confirmed by NICHD ECCRN’s analysis (2002), which found a pathway from teachers’ training and classroom ratios through process quality to children’s social and cognitive competence. For this reason, we focus on identifying thresholds within structural quality indicators relative to the ECERS-R.

To date, no study has identified thresholds in structural quality indicators relative to the ECERS-R or other process quality measures. However, studies conducted at the early elementary grades suggest that thresholds exist on structural quality indicators, although these studies identified thresholds relative to achievement measures as opposed to process quality measures. At the elementary grades, many studies have found a ceiling threshold between teachers’ years of experience and student achievement, such that years of experience is most strongly related to achievement within the first five years of teaching, and levels off after these initial years (Clotfelter, Ladd, & Vigdor, 2005; Kane, Rockoff, & Staiger, 2008; Miller, Murnane, & Willet, 2008). Assuming that the thresholds found on the achievement measures will be similar to the thresholds found on the process quality measures, we hypothesize that there will be a positive relationship between teaching experience and the ECERS-R, but this positive relationship will be limited to the initial years of experience.

Research at the elementary grades also suggest that there are thresholds within classroom ratios relative to achievement. A number of studies have suggested the thresholds at which gains in student achievement are realized lie between the range of 15 to 20 students per teacher for the early elementary grades (Glass & Smith, 1979; Slavin, 1989). For example, Molnar, Smith, Zahorik, Halbach, Ehrle, and Hoffman (2001) reported that after classrooms reached 15 students per teacher, there were declines in English and mathematics test scores for each additional student added to the classroom. Because our study examined preschool-aged children, who may require more individualized assistance from their teachers in comparison to elementary school children, we predict that the relationship between classroom ratios and ECERS-R will be null until a threshold located in the lower- to mid-range of the ratio distribution is reached. After that ratio threshold is surpassed, we expect to observe negative relationships between classroom ratios and ECERS-R scores, as teachers’ abilities to individualize children’s learning needs may be comprised by larger ratios.

Less clear are the expected relationships between teacher formal education in early childhood education (ECE) or child development and the ECERS-R. Theoretically, teachers who have more knowledge about children’s development and pedagogy gained through formal college coursework are expected to demonstrate higher levels of process quality (de Kruif, McWilliam, Ridley,& Wakely, 2000; NICHD ECCRN, 2002). However, these expected relationships are not always observed in the research literature (Early et al., 2007). The inconsistent linear relationships may indicate that a substantial amount of early childhood education specific coursework may be needed before positive relationships can be observed. Thus, with respect to number of ECE college credits taken, we hypothesize a baseline threshold located within the upper end of the ECE credits distribution.

Method

Study Site

Colorado’s QRIS system, called the Qualistar Early Learning Quality Rating and Improvement System (hereafter referred to as Qualistar QRIS) was selected for this study because the state had available child outcome data gathered through a validation study of the state’s QRIS (Zellman, Perlman, Le, & Setodji, 2008). The Qualistar QRIS was intended to improve the availability of high-quality child care throughout the state by assessing centers on quality measures that could provide sufficiently detailed feedback that would inform quality improvement plans, coaching, and levels of financial support to centers that would enable them to improve (Zellman et al., 2008). Under the Qualistar QRIS, preschool classroom quality was conceptualized as a multidimensional construct, represented by five components: (a) classroom learning environment (e.g., the ECERS-R); (b) classroom ratios; (c) teacher and director training and education; (d) family partnerships; and (e) accreditation. Centers were rated on each of the components, and assigned points based on the thresholds reached. The component points were then added together, and the total points were used to assign a holistic star rating to each center. Star ratings ranged from 0 to 4, where higher ratings were intended to represent better child care quality. Table 1 provides a description of the thresholds adopted for each component (Tout et al., 2010).

Table 1.

Thresholds on Qualistar’s QRIS Components

| Quality Component | Threshold Descriptions | Points Possible |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classroom learning environment (ECERS-R) | 2 points: 3.50–3.99 | 10 | |||

| 4 points: 4.00–4.69 | |||||

| 6 points: 4.70–5.49 | |||||

| 8 points: 5.50–5.99 | |||||

| 10 points: 6.00–7.00 | |||||

| Child-staff ratios | 36–47 months | 48–71 months | 30–71 months | 8 | |

| 4 points | 10:1 | 12:1 | 10:1 | ||

| 6 points | 9:1 | 10:1 | 9:1 | ||

| 8 points | 8:1 | 8:1 | 8:1 | ||

| Staff and director training and education | Director credentials: years of administrative experience, whether the director had a Director Qualifications certificate, whether the director had at least a bachelor’s degree Teacher credentials: years of experience in child care, number of early childhood education credits taken, whether the teacher had at least a bachelor’s degree | 10 | |||

| Threshold for directors’ years of administrative experience: 2000 and 4000 hours | |||||

| Thresholds for teachers’ years of teaching experience: 2000 and 4000 hours | |||||

| Thresholds for early childhood education credits: 3, 6, 15, and 24 credits | |||||

| Note. A complex scoring matrix was used to assign the number of points earned based on various combinations of teachers’ and directors’ experience, early childhood credits, and education. This meant that the same qualification could be associated with different amounts of rating points, depending on the staff’s attainment on the other factors. | |||||

| Family partnership | 2 points: 28–35 total survey points | 8 | |||

| 4 points: 36–43 total survey points | |||||

| 6 points: 44–51 total survey points | |||||

| 8 points: 52 or more total survey points | |||||

| Note. The family partnership survey scale ranged from 0 to 58 points. | |||||

| Accreditation | 0 points: No accreditation | 2 | |||

| 2 points: Whether center received accreditation from a national accrediting agency | |||||

Study Sample

Participating centers

Community-based child care centers that were licensed were eligible to participate in this study if they (a) consented to be part of a longitudinal evaluation of Colorado’s QRIS; (b) enrolled at least 20 three- and four-year old children; (c) were located near a low-performing elementary school; and (d) served a high-needs population in which at least 50 percent of the children enrolled received child care subsidies to attend the center. To expand socioeconomic representation, six university-based child care programs that served no more than 30 percent of children eligible to receive child care subsidies were also eligible for the study.

Based on these eligibility criteria, directors of 78 centers were invited to attend an informational meeting on the QRIS and the evaluation. Representatives from 68 of the centers attended, and 49 center directors agreed to participate. Of the programs that declined to participate, 10 were located in large public school systems where principals felt that obtaining approval for study participation was too cumbersome. Therefore, inferences drawn from this study should be restricted to community-based programs.

Participating children

All three- to five-year-old children who attended centers for at least 10 hours per week were eligible to participate in the study. To obtain a random sample of children, we used the birth-month method (Forsman, 1993), where directors ordered the children by month and day of birth, then approached children with the most recent birth month, relative to the study start date, which varied across centers. Because birth month and day are random and not expected to predict children’s outcomes, this method led to a random sample. Overall, 94 percent of the parents who were approached agreed to allow their children to participate in the study.

To take into account children’s prior year scores, we focused on children who did not “age out” of the study and could be assessed at least twice. This sample consisted of 380 children, representing 71 percent of the eligible child population. The remaining 29 percent did not return to the center and therefore did not get assessed for a second time.

Qualistar’s QRIS Measures

Classroom learning environment

A modified version of the ECERS-R was used to assess the classroom learning environment. The Parents and Staff subscale of the ECERS-R was not administered because the QRIS developers felt that the subscale, which largely relied on self-report, would be subject to potential respondent bias (Achenbach, McConaughy, & Howell, 1987), especially when used within high-stakes contexts such as the state’s QRIS. This reduced the scale to 36 items, each scored on a 7-point scale with items averaged to achieve an overall score. Qualistar data collectors collected ECERS-R data from 133 classrooms, which represented all classrooms serving preschool-aged children in the centers. The alpha reliability coefficient for the total ECERS-R score across data collection waves was 0.86–0.89.

Staff and director training and education

A survey was administered to all staff who worked at least 30 percent of the time that the center was open. For teaching staff, the survey asked about their highest level of formal education, years of paid teaching experience with children from birth to age five, and number of college credits taken in ECE or child development. An analogous survey was administered to directors, except the survey included an item about years of administrative experience. QRIS data collectors used transcripts to verify staff self-reported information relating to education level and number of ECE credits completed. Information on staff qualifications was collected from 49 directors and 298 teachers. The staff responses represented 100 percent of the center directors, and 99 percent of eligible teachers.

Classroom ratios

QRIS data collectors recorded the number of paid teaching staff and children in classrooms over two days during eight different time period counts that ranged from early morning care to late afternoon care. Classroom ratios were derived by averaging the number of adults and children in the classroom across time counts. Classroom ratios were collected from all 133 preschool-aged classrooms in the centers.

Family partnership

The family partnership component consisted of separate surveys administered to families and center directors, and assessed the frequency and nature of parent education opportunities and communications between centers and families(Zellman et al., 2008). Qualistar combined the parents’ and directors’ responses together to score the centers, and scores could range from 0 to 58 points. The alpha reliability coefficient of the family partnership survey was high, ranging from 0.77 and 0.80 across waves. We collected family partnership data from 100 percent of the centers.

Accreditation

Qualistar awarded points to a center based on whether a center had achieved national accreditation. Although Qualistar accepted accreditation from a number of organizations, all centers in this study that had achieved national accreditation were accredited by the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC). Programs received 2 points if they had attained NAEYC accreditation and 0 points if they were not accredited. We obtained accreditation status from 100 percent of the centers in the study.

Child-Level Measures

Woodcock-Johnson Tests of Achievement

Selected subtests from the Woodcock-Johnson Tests of Achievement, Third Edition (Woodcock, McGrew, & Mather, 2001) were used to assess several dimensions of children’s cognitive development. These subtests included: (1) the letter–word identification subtest (WJ-LWI), the passage comprehension subtest (WJ-PC), and the applied problems (WJ-AP) subtest. The WJ-LWI examines children’s symbolic learning skills and reading identification skills. The WJ-PC examines children’s reading comprehension by asking children to supply a missing word removed from a sentence based on the context of the passage. The WJ-AP requires children to perform simple math operations to solve the problem. Children’s participation rate on the WJ was 96 percent and the alpha reliability coefficients for the WJ-LWI, WJ-PC, and WJ-AP ranged from 0.82 to 0.86 across waves.

Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test

The Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test, Third Edition(PPVT; Dunn & Dunn, 1997)was used to assess children’s receptive language skills. Children were presented with four black-and-white pictures and asked to select the picture that best matched the spoken word. PPVT were collected from 98 percent of the participating children in our analytic sample, and the alpha reliability coefficients across waves were 0.85 to 0.86.

Student-Teacher Relationship Scale

The Student-Teacher Relationship Scale(STRS;Pianta, 1991) was administered to each study child’s head teacher to assess the overall quality of the teacher’s relationship with the child. The STRS was composed of 28 items that assessed conflict, closeness, and dependence in the teacher-child relationship. Items within the subscales were summed to create an overall composite score, where higher scores denoted a better student-teacher relationship. The STRS was collected on 99 percent of the analytic sample, and the alpha reliability coefficients for the STRS scale ranged from 0.82 to 0.84 across data collection waves.

Child Behavior Inventory

Study children’s head teachers also completed the 60-item, 5-point Likert-scaled Child Behavior Inventory (CBI; Schaefer, Edgerton,& Aaronson, 1978). The CBI measured different aspects of children’s social and emotional characteristics, including considerateness, hostility, introversion, extroversion, independence, dependence, task orientation, creativity/curiosity, apathy, distractibility, and verbal intelligence. Scale scores were created for each of the 10 CBI components, and had reliability coefficients ranging from 0.77 to 0.87. CBI surveys were collected for 99 percent of the children in our analytic sample.

Family background survey

Families of children participating in the study were administered a survey asking about key background characteristics related to children’s school readiness. The survey asked families about their child’s race/ethnicity, gender, age, length of time that the child had been enrolled in the center, number of hours that their child received care from the center per week, and whether the child had a learning disability. It also asked families about their income, highest level of education attained by each parent, and primary language spoken at home. Family surveys were collected from 79 percent of the parents in our sample.

Procedures

Each center participating in this study was assigned a six-week data collection window. During the first month, center directors received the parental version of the family partnership survey to distribute to families, the director version of the family partnership survey, and training and education surveys to be completed by all teaching and administrative staff. In addition, trained data collectors were dispatched to each participating center. All data collectors had at least a bachelor’s degree in early childhood education or a related field and experience working in early childhood settings. Data collectors had also participated in a one-week training course on data collection procedures, which included a two-day session on the ECERS-R conducted by an expert scorer, referred to as a state anchor, who had been trained and deemed a reliable rater by the developers of the ECERS-R. Each data collector was required, during three consecutive administrations of the ECERS-R, to score 85 percent of the items on the ECERS-R within one scale point of the state anchor. The reliability of the data collectors was re-checked after every tenth ECERS-R administration, and all data collectors passed the re-reliability checks.

The ECERS-R observations were unannounced, although center staff were aware of their one-month data collection window. All observations were conducted between approximately 8:30 a.m. and 1:30 p.m. During the ECERS-R administration, data collectors recorded classroom ratios during six time points. The data collector returned to the center in the afternoon during the last week of the one-month data collection window to collect completed training and education surveys, to record classroom ratios during two additional afternoon time points in each classroom, and to pick up the completed family partnerships surveys.

Immediately after the center’s one-month QRIS data collection window ended, another set of data collectors, unrelated to Qualistar and blind to the center’s QRIS rating and classroom’s ECERS-R scores, were dispatched to each participating center to collect child assessments on each child in the study. Child assessments occurred within 2-weeks of the quality rating. Each of the data collectors had at least a bachelor’s degree in a social sciences field and had attended a two-week training on data collection procedures. Data collectors worked with center directors to arrange a quiet place in the center where the child assessments were administered. In addition, data collectors distributed family questionnaires in children’s cubbies with a self-addressed stamped envelope to be returned to researchers. Post-tests on classroom quality and children’s outcomes were administered approximately one year after pre-tests.

Analytic Approach

GAM

To identify thresholds, we followed the same approach as Setodji et al. (2013), and adopted a GAM model of the form:

, where for childi, Outcomei represents the outcome, Qualityi denotes the vector of child care quality, characteristics, Xpi (k = 1,2,…,p) indicates the child-level covariates, and εi is a random error, commonly assumed to be normally distributed with mean 0 and constant variance. In the above equation, f1,…,fp and g represent unknown, non-linear functions that are estimated non-parametrically. GAM is an ideal approach for identifying thresholds because it forgoes the assumption that the relationship between quality and outcomes is necessarily constant, and instead allows for the strength of relationships to vary across the range of the quality distribution (i.e., it allows for non-linear relationships without having to specify the parametric form). For model outcomes measured at the classroom level, a similar model was used with classroom-level observations.

We plotted the raw scores from each quality measure against its non-linear smoothed values derived from g(Qualityi). In the plots, the x-axis provides the levels of the quality variables and the y-axis provides the non-linear smoothed contribution g(Qualityi) of Qualityi to the outcome and can be viewed as a standardized regression coefficient, or scaled effect size, of the relationship between quality and outcomes. Increasing trends (i.e., positive slopes) indicate that higher quality is associated with better covariate-adjusted outcomes, whereas decreasing trends (i.e., negative slopes) indicate that higher quality is associated with poorer covariate-adjusted outcomes. We identified thresholds by looking for regions on the graph where there were systematic changes in trends. A change from non-increasing to increasing trends would be indicative of a baseline threshold, and a change from positive slopes to flat or negative slopes would be indicative of a ceiling threshold.

Piecewise regression

Although GAM can provide visual guidance as to the score ranges where thresholds are likely to exist, it does not necessarily identify the exact cut-points to be adopted. Instead, GAM requires analysts to make judgments as to where the thresholds should be established. Because the GAM plots can conceivably support a number of different but equally viable cut-points within a range, analysts using GAM may need to confirm the validity of their chosen thresholds. Following the procedures proposed by Setodjiet al.(2013), we validated the GAM-derived thresholds through piecewise regression, which tests whether the slopes between a particular quality measure and outcomes vary across the different regions defined by the thresholds.

Principal components

A key analytic challenge is the possibility that thresholds may vary across the different outcome measures. Thresholds may appear on one outcome measure, and not another, but policy decisions are more effective if a single set of thresholds is estimated across multiple outcomes, especially the ones measuring the same construct. To synthesize the thresholds across the four cognitive and ten social measures, we subjected the outcome measures to a principal components analysis. Two components emerged, with the cognitive measures loading on the first component, and the social measures loading on the second component. We then re-ran the principal component analysis using only the outcome measures in the particular component constructed, and then used the component loadings as scoring coefficients. This resulted in two component scores corresponding to the cognitive factor (hereafter referred to as the Cognitive Composite) and the social factor (hereafter referred to as the Social Composite). We identified thresholds on each of these composites, and examined whether the same thresholds appeared on the individual outcome measures comprising the composite.

Model details

For the child-level analysis, we excluded children who had a learning disability or whose primary language spoken at home was not English (as indicated by parents on the family background survey), because these children represented less than 2 percent of the sample. Our independent variables included race/ethnicity, age at assessment, gender, whether the child’s family met the state median income, whether either of the child’s parents had at least a bachelor’s degree, the number of hours of child care the child attended per week, the length of time the child had been enrolled in the center, the number of months that had elapsed between assessments, and the child’s prior cognitive or social measure scores collected from an earlier wave. In addition, we reverse scored the apathy, dependence, distractibility, and hostility scales so that higher scores on these scales represented more favorable outcomes (e.g., higher scores on the apathy scale represented lower levels of apathy).

For the classroom-level analysis, we aggregated the teacher-level variables to the classroom level. The independent variables in our classroom-level model included non-profit status, Head Start status, NAEYC accreditation status, family partnership points, classroom ratios, average years of teaching experience in the classroom, directors’ years of administrative experience, average number of ECE credits taken by teachers and by the director, and variables denoting whether teachers and directors had at least a bachelor’s degree.

For both analyses, we standardized the outcomes variables, and adjusted the standard errors using a modification of the Huber-White standard error to account for the clustering of children within the same classrooms, or for the clustering of teachers within the same centers. The modified Huber-White standard error not only accounts for the intra-class correlations, but also adjusts the denominator degrees of freedom to account for the number of clusters (Freedman, 2006).

Results

Sample Characteristics

Table 2 provides the descriptive statistics for the variables used in our study. The sample was equally split between boys and girls, and 56 percent were African-American, 12 percent were white, 23 percent were Hispanic, and 9 percent were another race/ethnicity. Half of the children’s families had income that were below the median income of the state, and 42 percent of children had at least one parent who had a bachelor’s degree or higher.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics for Child- and Classroom-Level Characteristics

| Variable | N | Mean | StdDev | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child-level characteristics | ||||

| At baseline | ||||

| PPVT | 300 | 93.27 | 14.95 | 47.00–147.00 |

| WJ-AP | 300 | 99.46 | 15.14 | 49.00–139.00 |

| WJ-PC | 300 | 122.01 | 12.76 | 88.00–163.00 |

| WJ-LWI | 300 | 102.07 | 22.09 | 69.00–180.00 |

| Apathy (reverse scored) | 300 | 3.73 | 0.79 | 1.00–5.00 |

| Considerate | 300 | 3.49 | 0.99 | 1.00–5.00 |

| Creativity | 300 | 3.72 | 0.90 | 1.00–5.00 |

| Dependence (reverse scored) | 300 | 3.40 | 0.88 | 1.00–5.00 |

| Distractibility (reverse scored) | 300 | 3.25 | 0.99 | 1.00–5.00 |

| Hostility (reverse scored) | 300 | 3.40 | 1.21 | 1.00–5.00 |

| Independence | 300 | 3.69 | 0.77 | 2.00–5.00 |

| Intelligence | 300 | 3.45 | 0.99 | 1.00–5.00 |

| Task orientation | 300 | 3.38 | 0.98 | 1.00–5.00 |

| STRS | 300 | 99.06 | 12.18 | 63.00–134.00 |

| At follow-up | ||||

| PPVT | 299 | 96.97 | 14.21 | 43.00–131.00 |

| WJ-AP | 293 | 98.73 | 13.13 | 55.00–133.00 |

| WJ-PC | 293 | 109.90 | 13.32 | 59.00–153.00 |

| WJ-LWI | 293 | 103.77 | 15.81 | 67.00–185.00 |

| Apathy (reverse scored) | 300 | 3.97 | 0.76 | 2.00–5.00 |

| Considerate | 300 | 3.66 | 0.88 | 1.00–5.00 |

| Dependence (reverse scored) | 300 | 3.69 | 0.81 | 1.00–5.00 |

| Distractibility (reverse scored) | 300 | 3.56 | 0.91 | 1.00–5.00 |

| Hostility (reverse scored) | 300 | 3.49 | 1.13 | 1.00–5.00 |

| Independence | 300 | 4.08 | 0.66 | 2.00–5.00 |

| Intelligence | 300 | 3.93 | 0.83 | 1.00–5.00 |

| Task orientation | 300 | 3.74 | 0.88 | 1.00–5.00 |

| STRS | 300 | 116.74 | 13.44 | 68.00–140.00 |

| Demographics | ||||

| Age at initial assessment (months) | 300 | 41.69 | 4.17 | 28.00–50.00 |

| Age at follow-up assessment (months) | 300 | 55.46 | 3.9 | 40.00–60.00 |

| Hours per week of care | 300 | 30.26 | 11.79 | 10.00–55.00 |

| Length of time in program (months) | 300 | 30.29 | 4.13 | 15.00–96.00 |

| Time between assessments (months) | 300 | 14.92 | 2.48 | 10.00–30.00 |

| Classroom-level characteristics | ||||

| ECERS-R | 133 | 5.43 | 0.79 | 2.33–6.60 |

| Classroom ratios | 133 | 5.49 | 1.58 | 2.00–9.63 |

| Teachers’ ECE credits | 133 | 10.71 | 10.99 | 0.00–45.00 |

| Teachers’ teaching experience | 133 | 5.47 | 3.77 | 0.00–30.00 |

Note. The characteristics of the 298 teachers were aggregated to the classroom level.

The average ECERS-R score was 5.43, which was considerably higher than the average ECERS-R score of 4.27 found in a nationally representative sample (Cannon, Jacknowitz, & Karoly, 2012). The higher ECERS-R score found in this study may reflect the fact that many of the centers were receiving coaching, technical assistance, and other supports to improve their quality. With respect to the program characteristics, 25 percent received Head Start funding, 65 percent were non-profit centers, and 23 percent had achieved NAEYC national accreditation.

The initial sample of 380 children decreased to 300 children due to missing responses, mostly on the family background survey. When comparing the sample of children without missing background information against those with missing background information, we found no differences between the two groups on the QRIS quality variables, social outcomes, or cognitive outcomes. This suggests that there is little chance of bias due to missing data.

Examining Thresholds on Qualistar’s QRIS Measures

ECERS-R

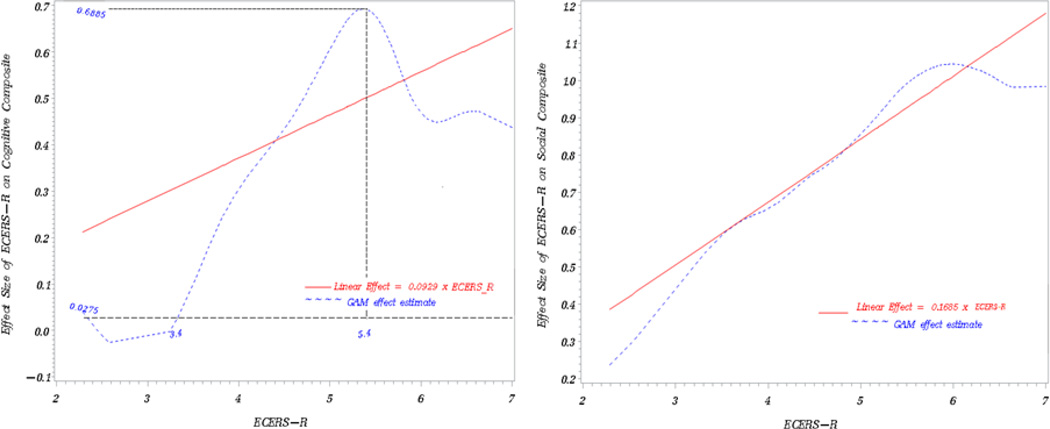

Figure 1 provides a graphical representation of the relationship between ECERS-R and the Cognitive Composite. In the plot on the left, the dashed line denotes the relationship between the ECERS-R and the Cognitive Composite under GAM, and the solid line denotes the relationship between the ECERS-R and the Cognitive Composite under a linear regression model. The plot suggested a baseline and ceiling threshold existed at an ECERS-R score of 3.4 and 5.4, respectively. We then used piecewise regression to examine whether there were significant relationships between the ECERS-R and children’s outcomes defined by the ECERS-R regions (a) between 1.0 and 3.4; (b) between 3.4 and 5.4; and (c) between 5.4 and 7.0 (see Table 3). Five percent of classrooms fell within the lowest ECERS-R region, 39 percent fell within the middle ECERS-R region, and 51 percent fell within the highest ECERS-R region.

Figure 1.

Plots of Predicted Effect Sizes of the ECERS-R in Relation to the Cognitive and Social Composites Under the Linear Regression and GAM Models

Table 3.

Linear and Piecewise Regression Coefficients and Standard Errors (in Parenthesis) for the ECERS-R in Relation to Child Outcomes

| Outcome | Child N | Linear

Regression Slopes |

Piecewise Regression

Slopes |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 ≤ ECERS-R ≤ 3.4 | 3.4 <ECERS-R ≤ 5.4 | 5.4<ECERS-R< 7.0 | |||

| Cognitive Composite | 292 | 0.093 (0.047) | 0.022 (0.0259) | 0.330 (0.099) ** | −0.204 (0.111) |

| PPVT | 299 | 0.149 (0.051) ** | 0.042 (0.288) | 0.281 (0.133) * | −0.023 (0.118) |

| WJ-AP | 293 | 0.051 (0.059) | 0.012 (0.285) | 0.272 (0.136) * | −0.292 (0.152) |

| WJ-PC | 293 | 0.058 (0.029) | 0.158 (0.192) | 0.071 (0.087) | 0.002 (0.093) |

| WJ-LWI | 293 | 0.088 (0.047) | −0.105 (0.352) | 0.234 (0.115) * | −0.084 (0.101) |

| Linear Regression Slopes | No Thresholds | ||||

| Social Composite | 300 | 0.169 (0.057) ** | |||

indicates significance at 0.05 level.

indicates significance at 0.01 level.

Although linear regression indicated a lack of relationship between the ECERS-R and the Cognitive Composite, the piecewise regression indicated that there were significant relationships within the regions defined by the thresholds of 3.4 and 5.4. The thresholds of 3.4 and 5.4 found on the Cognitive Composite were also observed on the PPVT, WJ-AP, and WJ-LWI. In the case of the latter two measures, linear regression failed to detect significant relationships between the ECERS-R and outcomes.

Figure 1 also shows the plot for the relationship between the ECERS-R and the Social Composite (see right plot). The GAM plot was similar to the linear regression plot, suggesting that no thresholds existed on the ECERS-R in relation to the Social Composite. Furthermore, similar trends were generally observed on the individual measures comprising the Social Composite, where the relationship between the ECERS-R and the various social outcomes tended to be linear.

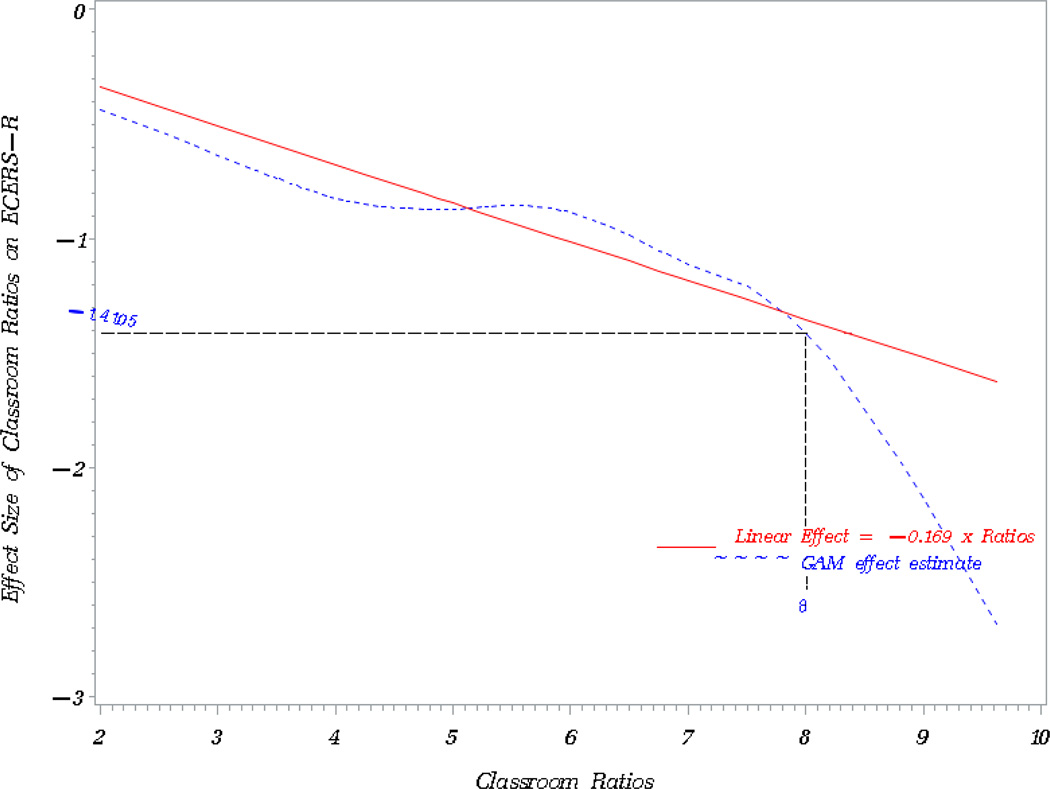

Classroom ratios

The plot depicting the relationship between classroom ratios and the ECERS-R under GAM and under linear regression is provided as Figure 2. While linear regression suggested a significant negative relationship between classroom ratios and the ECERS-R, the GAM plot suggested a more nuanced picture, with the negative relationship becoming particularly pronounced at a classroom ratio of 8:1 and beyond. The piecewise regression confirmed that a threshold existed at a classroom ratio of 8 children per staff, as there was no relationship between the ECERS-R and classroom ratios until classroom ratios reached 8:1 (see Table 4). Thereafter, the relationship became significantly negative. Ninety percent of classrooms had ratios below the 8:1 threshold.

Figure 2.

Plots of Predicted Effect Sizes of Child-Staff Ratios in Relation to the ECERS-R Under the Linear Regression and GAM Models

Table 4.

Linear and Piecewise Regression Coefficients and Standard Errors (in Parenthesis) for the Classroom-Level Quality Variables in Relation to the ECERS-R (N=133 classrooms)

| Variable | Linear Regression Slopes | Piecewise Regression

Slopes |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 ≤ Variable < T | Variable ≥ T | T | ||

| Classroom ratios | −0.169(0.060) ** | −0.102 (0.057) | −1.001 (0.441) * | 8 |

| Teachers’ ECE credits | 0.015 (0.008) | 0.048 (0.022) * | 0.007 (0.007) | 12 |

| Teaching experience | 0.013 (0.013) | −0.007 (0.020) | 0.073 (0.024) ** | 15 |

Note. T represents the identified threshold for a given variable.

indicates significance at 0.05 level.

indicates significance at 0.01 level.

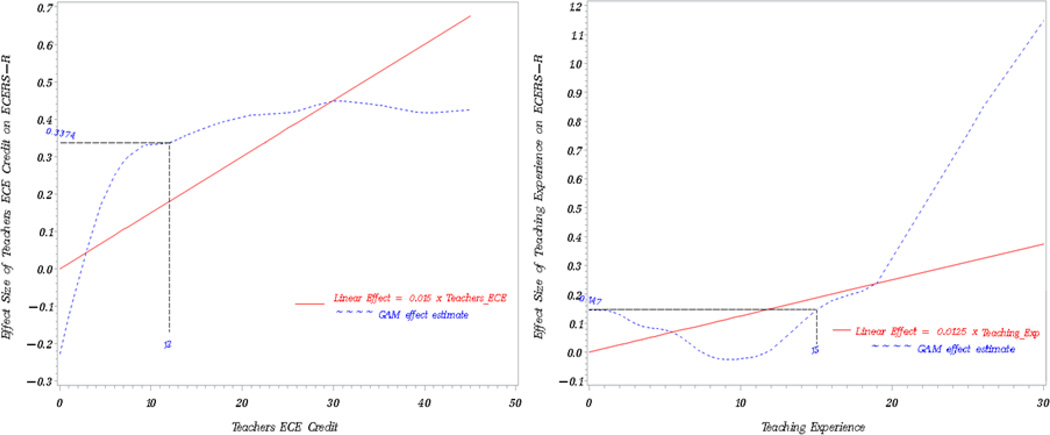

Teachers’ ECE credits

Figure 3 shows the association between number of ECE credits taken by teachers and the ECERS-R (see left plot). The linear regression analysis indicated there was a significant relationship between teachers’ ECE credits and the classroom’s ECERS-R score throughout the range of the ECE distribution, but the GAM plot indicated that this relationship was significant only up until 12 ECE credits was reached. The results of the piecewise regression validated the selection of a threshold at 12 ECE credits, as the positive association between ECE credits and ECERS-R ceased to be significant once the classroom average surpassed 12 ECE credits (see Table 4). Approximately 45 percent of classrooms had teachers who averaged 12 or fewer ECE credits.

Figure 3.

Plots of Predicted Effect Sizes of Teachers’ ECE Credits and Teaching Experience in Relation to the ECERS-R Under the Linear Regression and GAM Models

Teachers’ years of experience

As shown in Figure 3, the linear regression and GAM plots gave different interpretations about the relationship between teaching experience and the ECERS-R (see right plot). While the linear regression analysis indicated there was no relationship, the GAM plot indicated that a baseline threshold of 15 years needed to be reached before a significant association could be observed. The piecewise regression results confirmed a threshold at 15 years, as the relationship between teaching experience and the ECERS-R was null between the range of 0 and 15 years, and significant thereafter (see Table 4). In our sample, eight percent of classrooms had teachers who averaged at least 15 years of experience.

Discussion

To date, thresholds on classroom quality measures within states’ QRIS have largely been informed by expert opinions and theoretical expectations (Zellman & Perlman, 2008). As the thresholds established within QRIS can play a key role in determining the levels of resources and incentives awarded to programs, it becomes increasingly important to identify the baseline, ceiling, and any intermediate thresholds that can guide those decisions. This study suggests that GAM may be a useful tool for informing these efforts by identifying cut-points on quality measures that define regions on the quality distribution that are most strongly associated with children’s developmental outcomes or with other measures of process and structural quality.

Evaluating Our Hypotheses about Thresholds in Quality Indicators

In our study, we examined thresholds on four quality indicators typically found within states’ QRIS system: ECERS-R, classroom ratios, number of ECE credits completed by teachers, and years of teachers’ teaching experience. Contrary to our hypothesis, we did not find any evidence of thresholds on the ECERS-R with respect to the Social Composite. Instead, we found a linear relationship, which suggests that that virtually any cut-score can be supported relative to this outcome, as higher ECERS-R scores was associated with better social development throughout the range of the ECERS-R score distribution. Therefore, there is validity evidence to support the Qualistar QRIS practice of awarding points at multiple ECERS-R score levels relative to social outcomes.

With respect to the Cognitive Composite, we observed two thresholds located at 3.4 and 5.4 on the ECERS-R. These thresholds are consistent with our initial hypothesis that thresholds would be located within the lower-and upper-range of the ECERS-R. An ECERS-R score of 3.4 suggests that classrooms have some learning materials available to children and have constructed a daily schedule that enable children to have significant time during the day to interact with these materials. The Qualistar QRIS currently awards the first level of points for this indicator at an ECERS-R score of 3.5, which is similar to our findings, and suggests that this may be the score point at which relationships to children’s cognitive development start to emerge.

Currently, the Qualistar QRIS awards four points to centers that receive an ECERS-R score between 4.00 and 4.69, and six points to centers that receive an ECERS-R score between 4.70 and 5.49. Our results provide validity evidence for awarding points at these thresholds, as the ECERS-R and cognitive development is positively related within this score range. The Qualistar QRIS also awards eight points to centers that receive an ECERS-R score at 5.5 and above, but our results indicate that beyond an ECERS-R score of 5.5, the ECERS-R and cognitive development ceases to be significant. Nonetheless, given that social development demonstrates a linear relationship with ECERS-R scores, the practice of awarding points to centers that exceed an ECERS-R score of 5.5 is warranted.

We observed a ceiling threshold at an ECERS-R score of 5.4, but this finding may have arisen from the fact that the ECERS-R is largely an environmental measure and may not focus enough on constructs such as instructional support and academic stimulation that are more likely to promote higher levels of children’s cognitive functioning. Thus, it may be that the ECERS-R has limited utility in measuring aspects of teaching that promote more significant cognitive development, and state policymakers who have an interest in promoting this aspect of development may elect to choose quality measures that are more sensitive to capturing domain-specific instructional practices. Therefore, when looking at trends across state quality data, states may choose to add more robust measures of the teacher instructional practices once scores of 5.4 have been surpassed on the ECERS-R, as opposed to de-investing in quality support for these centers and assuming that better child outcomes cannot be realized after an ECERS-R score of 5.4 has been reached. In other words, the measurements used in a state’s QRIS may be an important consideration when examining the possibility of additional thresholds in relation to thresholds associated with greater levels of children’s cognitive outcomes.

Our hypothesis regarding thresholds on classroom ratios was also confirmed, as the negative relationship between classroom ratios and the ECERS-R was not manifested until a ratio of 8:1 was reached. Thereafter, adding an additional child to the classroom was associated with significant declines in ECERS-R scores. This finding is consistent with the studies within the early elementary grades where negative associations between class size and achievement were not observed until a threshold within the mid-range of the class size distribution was reached (Glass & Smith, 1979; Slavin, 1989). The finding of a threshold at a ratio of 8:1 also has implications for the Qualistar QRIS, which awards points at ratios of 8:1, 9:1, 10:1 and 12:1. Although our results provide validity evidence for awarding points to centers at a ratio of 8:1, the results also suggest that the decision to award points at ratios of 9:1 and larger may need to be reconsidered, as ratios within this range were not associated with developmentally supportive or stimulating classroom environments.

Our hypothesis that a substantial amount of ECE coursework was needed before a positive relationship with the ECERS-R could be demonstrated was not confirmed. Instead, even when very few ECE credits had been attained, we observed a positive relationship between ECE credits and the ECERS-R. This relationship was significant until a ceiling threshold of 12 credits was reached, then diminished thereafter. The diminishing relationship may be a function of the ECERS-R measure, where a majority of its items are constructed around the physical environment. Thus, the ECERS-R maybe able to capture activities that help teachers construct better physical environments, but is less sensitive to the specialized child development training that is included in more advanced ECE classes. It is also possible that higher levels of ECE credits were not related to higher ECERS-R scores because the content and quality of the coursework was not considered, which can influence teachers’ abilities to implement developmentally and academically stimulating curricula. Finally, it is also possible that with classroom coaching, teachers implemented more developmentally appropriate practices, which served to attenuate the relationships between ECE credits and the ECERS-R.

The threshold results for ECE credits provide mixed validity evidence for the manner in which the Qualistar QRIS awards points on the teacher training and education component. Although the results support the Qualistar QRIS practice of awarding points once teachers have surpassed three or six ECE credits, the findings did not support the practice of awarding points once 12 ECE credits had been surpassed. Again, it is important to note the limitations of the ECERS-R as a measure of instructional quality, and more research is needed to determine whether a leveling-off effect of ECE credits would be observed on other measures of process quality that are more focused on instructional practices and in classrooms that have not yet received coaching.

With respect to teaching experience, we did not find any support for our hypothesis that teaching experience would be positively related with quality in the initial years, then dissipate thereafter. Instead, we observed a baseline threshold, such that the relationship between teaching experience and the ECERS-R did not manifest itself until approximately 15 years of teaching experience was reached. This finding is consistent with the notion that new teachers struggle during their first several years in their positions (Katz, 1972), but as the years pass, they gain greater competency with respect to understanding teaching and learning and may become more committed to the field, thus improving their practices. This finding may also reflect the possibility that teachers who are less suited to the work, or who do not receive sufficient mentoring, are more likely to drop out of the ECE sector (Holochwost, DeMott, Buell, Yannetta, & Amsden, 2009). Taken together, the result underscores the need for better compensation and other teacher supports that reduce staff turnover and enable staff to remain in the field and gain the experience needed to promote better quality (Whitebook & Sakai, 2004).

The finding also has implications for the thresholds adopted by the Qualistar QRIS for experience. Currently, Qualistar QRIS awards points to teachers for only up to two years of teaching experience, but our analysis suggests that thresholds that go beyond this minimal level of experience are warranted. Thus, Qualistar QRIS may want to restructure its training and education component to award points to teachers who have more than two years of experience.

Study Limitations and Next Steps for Research

There are several limitations to our study. First, it is important to note that we did not have a randomized design that can support causal inferences about the relationships between quality and outcomes. Children may be assigned to teachers or classrooms based on teacher characteristics. For example, children who need additional assistance may be assigned to teachers who are perceived to be particularly effective. Alternatively, particularly effective teachers may be assigned to academically- or socially-advanced children. Under these conditions where children are not randomly assigned to teachers, the observed relationships may reflect preexisting differences between children in the classroom (Rothstein, 2009). While we have attempted to minimize the self-selection bias by including measures of prior cognitive and social achievement in our models, the results may nonetheless reflect non-random sorting of children into classroom and other unobserved biases.

It is also important to caveat that more research is needed to explore the generalizability of the identified thresholds to other contexts. For example, our study drew primarily from centers serving high-needs children. Different thresholds may have emerged if our study had greater representation from all economic strata. However, most states have prioritized the application of QRIS in centers that serve high-needs children in an effort to help close the achievement gap (Schaack et al., 2012) and therefore, these findings may be of particular interest to policymakers and QRIS developers. In addition, we did not examine outcomes relating to children’s health and physical development, which may have resulted in different cut-points. For example, scores at the lower end of the ECERS-R focus on health and safety issues, which may have resulted in our observing lower thresholds had these outcomes been examined.

In some instances, our analysis was conducted on a small number of observed cases within the regions defined by the threshold, and it is possible that the small sample sizes affected the identification of thresholds. For example, with respect to the thresholds found on the ECERS-R relative to the Cognitive Composite, only five percent of the observations fell below the ECERS-R baseline threshold score of 3.4. Notably, the baseline threshold of 3.4 found on the ECERS-R in this study is similar to the baseline threshold of 3.8 found on a nationally-representative study that included the ITERS (Setodji et al., 2013), which is a parallel measure to the ECERS-R, but used to measure quality within toddler-aged classrooms. The fact that the two similarly constructed measures yielded comparable baseline thresholds provides some suggestive evidence for the replicability of the thresholds identified in this study, but ultimately, research that identifies thresholds with larger samples is needed.

Research also needs to be conducted on how to synthesize thresholds that vary across different domains of children’s outcomes. In our study, the relationships between QRIS quality measures and children’s outcomes were not always consistent across the Cognitive Composite and the Social Composite, nor were the same thresholds found across the individual cognitive and social measures. Although not examined in this study, it is also likely that thresholds will vary across age groups. It should not be expected that developmentally supportive ratios would be the same for infants as for preschool-aged children, and states have already taken into account the need to vary particular structural indicators according to age groups.

One possibility for adopting thresholds that can cut across different age groups and outcomes is to adopt the lowest threshold observed. For example, in this study, we observed a threshold on the ECERS-R at 3.4, which was the minimum level of ECERS-R quality that children needed to be exposed to before significant relationships with cognitive development could be observed. To ensure that children receive a minimum level of quality that promotes the development of cognitive functioning, QRIS developers may want to implement decision rules that preclude programs from obtaining certain ratings unless all observed classrooms exceed a specified baseline threshold. Currently, many QRIS have implemented a “no score below” rule in assigning centers their QRIS ratings (Karoly, Zellman, & Perlman, 2013), but the selection of the thresholds have not been determined in an empirical manner. This study demonstrates the utility of GAM for identifying potential thresholds that can be used for basal levels of scoring.

Relatedly, our study suggests linear regression analysis may not accurately depict the relationship between quality measures and child outcomes. In many instances, linear regressions suggested a lack of relationship between quality variables and child outcomes, when in fact, there were specific regions of significant, positive relationships. In other instances, linear regression analysis suggested positive associations between quality measures and child outcomes throughout the quality score distribution, when in fact, such positive relationships were limited to specific score ranges. GAM is able to detect these types of relationships, and may be useful for finding statistically significant links between child care quality and child outcomes that are missed by linear regression analysis. We observed such instances of missed relationships with respect to the ECERS-R in relation to the Cognitive Composite, and teaching experience in relation to the ECERS-R. We propose that future validation efforts of QRIS measurement approaches use non-parametric methods as a means of finding potentially significant associations between quality and outcomes that may be obscured by linear modeling.

Highlights.

We use generalized additive models (GAM) to empirically identify thresholds on the quality components within Colorado’s quality improvement and rating system.

We identified baseline thresholds on the ECERS-R in relation to cognitive outcomes and teachers’ experience in relation to the ECERS-R.

We identified ceiling thresholds on the ECERS-R in relation to cognitive outcomes, and on teachers’ coursework in relation to the ECERS-R.

GAM is able to detect statistically significant relationships obscured by linear modeling.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Grant R03 HD055295, the Colorado Trust, the Temple Hoyne Buell Foundation, and the Annie E. Casey Foundation. The content or opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of the funders. We thank Qualistar Early Learning for their support for this study as well as three anonymous reviewers for their feedback. Any errors remain our own.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Vi-Nhuan Le, NORC at the University of Chicago.

Diana D. Schaack, San Diego State University

Claude Messan Setodji, RAND.

References

- Achenbach TM, McConaughy SH, Howell CT. Child/adolescent behavioral and emotional problems: Implications of cross-informant correlations for situational specificity. Psychological Bulletin. 1987;101(2):213–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth MS, Blehar MC, Waters E, Wall S. Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the Strange Situation. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Birch S, Ladd G. The teacher-child relationship and children’s early school adjustment. Journal of School Psychology. 1997;35(1):61–79. [Google Scholar]

- Burchinal MR, Kainz K, Cai Y. How well are our measures of quality predicting to child outcomes: A meta-analysis and coordinated analyses of data from large scale studies of early childhood settings. In: Zaslow M, Martinez-Beck I, Tout K, Halle T, editors. Measuring quality in early childhood settings. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes; 2011. pp. 11–31. [Google Scholar]

- Burchinal M, Vandergrift N, Pianta R, Mashburn A. Threshold analysis of association between child care quality and child outcomes for low-income children in pre-kindergarten programs. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2010;25(2):166–176. [Google Scholar]

- Cannon J, Jacknowitz A, Karoly L. Preschool and school readiness: Experiences of children with non-English-speaking parents. San Francisco, CA: Public Policy Institute of California; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Clotfelter CT, Ladd HF, Vigdor JL. Who teaches whom? Race and the distribution of novice teachers. Economics of Education Review. 2005;24(4):377–92. [Google Scholar]

- deKruif REL, McWilliam RA, Ridley SM, Wakely MB. Classification of teachers’ interaction behaviors in early childhood classrooms. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2000;15(2):247–268. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn LM, Dunn LM. Peabody Picture Vocabulary. Test—3rd edition. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Services; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Early D, Maxwell KL, Burchinal MR, Alva S, Bender RH, Bryant D, Zill N. Teachers’ education, classroom quality, and young children’s academic skills: Results from seven studies of preschool programs. Child Development. 2007;78(2):558–580. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsman G. Sampling individuals within households in telephone surveys. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Statistical Association: San Francisco, CA; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Freedman DA. On the so-called Huber sandwich estimator and robust standard errors. The American Statistician. 2006;60(4):299–302. [Google Scholar]

- Glass GV, Smith ML. Meta-analysis of research on class size and achievement. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis. 1979;1(1):2–16. [Google Scholar]

- Harms T, Clifford R, Cryer D. The Early Childhood Rating Scale - Revised. New York, NY: Teachers College Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Holochwost SJ, DeMott K, Buell M, Yannetta K, Amsden D. Retention of staff in the early childhood education workforce. Child & Youth Care Forum. 2009;38(5):227–237. [Google Scholar]

- Howes C, Matheson C, Hamilton L. Children’s relationships with peers: Differential associations with aspects of the teacher-child relationship. Child Development. 1994;65(1):253–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00748.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howes C, Spieker SJ. Attachment relationships in the context of multiple caregivers. In: Cassidy J, Shaver PR, editors. Handbook of Attachment. 2nd Ed. New York, NY: Guilford; 2008. pp. 317–332. [Google Scholar]

- Kane TJ, Rockoff JE, Staiger DO. What does certification tell us about teacher effectiveness? Evidence from New York City. Economics of Education Review. 2008;27(6):615–631. [Google Scholar]

- Karoly LA, Zellman GL, Perlman M. Understanding variation in classroom quality within early childhood centers: Evidence from Colorado’s quality rating and improvement system. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2013;28(4):645–657. [Google Scholar]

- Katz L. Development stages of preschool teachers. Elementary School Journal. 1972;73(1):50–54. [Google Scholar]

- Loeb S, Fuller B, Kagan SL, Carrol B. Child care in poor communities: Early learning effects of type, quality, and stability. Child Development. 2004;75(1):47–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malone L, Kirby G, Caronongan P, Tout K, Boller K. Measuring quality across three child care quality rating and improvement systems: Findings from secondary analyses. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mashburn AJ, Pianta RC, Hamre BK, Downer JT, Barbarin O, Bryant D, Howes C. Measures of classroom quality in prekindergarten and children’s development of academic, language, and social skills. Child Development. 2008;79(3):732–749. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller RT, Murnane RJ, Willet JB. Do teacher absences impact student achievement? Longitudinal evidence from one urban school district. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis. 2008;30(2):181–200. [Google Scholar]

- Molnar A, Smith P, Zahorik J, Halbach A, Ehrle K, Hoffman LM. 2000-2001 Evaluation results of the Student Achievement Guarantee in Education (SAGE)program. Milwaukee, WI: Center for Education Research, Analysis and Innovation, University of Wisconsin; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Moore GT. Milwaukee, WI: School of Architecture and Urban Planning at the University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee; 1994. The evaluation of child care centers and the Infant/Toddler Environment Rating Scale: An environmental critique. [Google Scholar]

- NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. Child care structure→process→outcome: Direct and indirect effects of child care quality on young children’s development. Psychological Science. 2002;13:199–206. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piaget J. The origins of intelligence in children. New York, NY: International Universities Press; 1952. [Google Scholar]

- Pianta RC. The Student Teacher Relationship Scale. Unpublished manuscript, School of Education; University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Pianta RC, La Paro KM, Hamre BK. Classroom Assessment Scoring System [CLASS] Manual: Pre-K. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein J. Student sorting and bias in value-added estimation: Selection on observables and un observables. Education Finance and Policy. 2009;4(4):537–571. [Google Scholar]

- Schaack D, Tarrant K, Boller K. Quality rating and improvement systems: Frameworks for early care and education systems change. In: Kagan SL, Kaurez K, editors. Early Childhood Systems: Looking Backward-Looking Forward. New York, NY: Teachers College Press; 2012. pp. 71–86. [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer ES, Edgerton M, Aaronson M. The Child Behavior Inventory. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Setodji CM, Le V, Schaack D. Using generalized additive modeling to empirically identify thresholds within the ITERS in relation to toddlers’ cognitive development. Developmental Psychology. 2013;49(4):632–645. doi: 10.1037/a0028738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slavin RE. Class size and student achievement: Small effects of small classes. Educational Psychologist. 1989;24(1):99–110. [Google Scholar]

- Smith S, Schneider W, Kreader J. Features of professional development and on-site assistance in child care quality rating and improvement systems A survey of state-wide systems. New York, NY: National Center for Children in Poverty, Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tout K, Starr R, Soli M, Moodie S, Kirby G, Boller K. Compendium of quality rating systems and evaluations. Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tout K, Zaslow M, Halle T, Forry N. Issues for the next decade of quality rating and improvement systems. Washington, DC: Child Trends and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Vandell D. Early child care: The known and the unknown. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2004;50(3):387–414. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky LS. Mind and society: The development of higher mental processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Whitebook M, Sakai L. By a thread: How child care centers hold on to teachers, how teachers build lasting careers. Kalamazoo, MI: Upjohn Institute for Employment Research; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock RW, McGrew KS, Mather N. Woodcock-Johnson III Tests of Achievement. Itasca, IL: Riverside; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Zaslow M, Anderson R, Redd Z, Wessel J, Tarullo L, Burchinal M. Quality dosage, thresholds, and features in early childhood settings: A review of the literature. Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zellman GL, Fiene R. Validation of quality rating and improvement systems for early care and education and school-age care. Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zellman GL, Perlman M. Child care quality rating and improvement systems in five pioneer states: Implementation issues and lessons learned. Santa Monica, CA: RAND; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Zellman GL, Perlman M, Le V, Setdoji C. Assessing the validity of the Qualistar Early Learning Quality Rating and Improvement System as a tool for improving child-care quality. Santa Monica, CA: RAND; 2008. [Google Scholar]