Abstract

This randomized controlled experiment compared the efficacy of two Response to Intervention (RTI) models – Typical RTI and Dynamic RTI - and included 34 first-grade classrooms (n = 522 students) across 10 socio-economically and culturally diverse schools. Typical RTI was designed to follow the two-stage RTI decision rules that wait to assess response to Tier 1 in many districts, whereas Dynamic RTI provided Tier 2 or Tier 3 interventions immediately according to students’ initial screening results. Interventions were identical across conditions except for when intervention began. Reading assessments included letter-sound, word, and passage reading, and teacher-reported severity of reading difficulties. An intent-to-treat analysis using multi-level modeling indicated an overall effect favoring the Dynamic RTI condition (d = .36); growth curve analyses demonstrated that students in Dynamic RTI showed an immediate score advantage, and effects accumulated across the year. Analyses of standard score outcomes confirmed that students in the Dynamic condition who received Tier 2 and Tier 3 ended the study with significantly higher reading performance than students in the Typical condition. Implications for RTI implementation practice and for future research are discussed.

Keywords: Response to intervention, multi-tiered systems of support, reading intervention, struggling reader, first grade, randomized control trial

In 2004, the reauthorization of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA, 2004) allowed states and local education agencies to use models of Response to Intervention (RTI) as a means of providing early intervention and identifying students as having a learning disability only after they have had effective instruction and intensive intervention. Briefly, within many RTI models, there are three tiers, with Tier 1 representing high quality general education, Tier 2 providing small group and more targeted intervention, and Tier 3 as the most intensive intervention and, in some models, special education services. Students are placed in tiers based on how well they are doing in less intensive tiers relative to grade level expectations and benchmarks using screening or progress monitoring assessments (Al Otaiba, Connor, Foorman, Greulich, & Folsom, 2009; Gersten et al. 2009).

Despite general support for multi-tier models, researchers and practitioners have expressed serious concern about the lack of research guidance for implementation. For example, despite the relatively robust evidence for Tier 2 interventions (e.g., Gersten et al., 2009; Wanzek & Vaughn, 2007), to date a fairly limited number of studies have reported effects of multi-tier intervention at the elementary level that includes what may be termed a Tier 3 intervention (Denton, Fletcher, Anthony & Francis 2006; Gilbert et al., 2013; O’Connor, Harty, & Fulmer, 2005; Vaughn, Wanzek, Linan-Thompson & Murray, 2007; Vaughn, Wanzek, Murray, Scammacca, Linan-Thompson, & Woodruff, 2009; Vellutino, Scanlon, Zhang & Schatschneider, 2008; Wanzek & Vaughn, 2010). From this set of studies, only O’Connor et al. and Gilbert et al. allowed students to move up or down tiers within a study year, whereas the remaining provided Tier 3 only after tracking response to Tier 2 for a year or more. Further, differences in how students were identified for intervention and how response was defined complicate direct comparisons across studies.

There is also a lack of guidance from a legal and policy perspective as documented in a review by Zirkel and Thomas (2010), who found marked variability in state laws and guidelines informing local education agencies about how to implement RTI. This variability about RTI procedures, particularly for Tier 3 was further validated by a survey of 40 elementary schools conducted by Mellard, McKnight, and Jordan (2010). The lack of consistency led Vaughn, Denton, and Fletcher (2010) to propose that “schools should consider placing students with the lowest overall initial scores in the most intensive interventions” (p. 442). Given that some students might be in a Tier 2 intervention that does not meet their intensive needs for too long, they argued against allowing RTI to become another type of wait to fail model, referring to historical criticisms of the IQ-achievement discrepancy model. Vaughn and her colleagues argued that immediate, intensive interventions may be the most appropriate for some students because it is increasingly possible to predict poor response by students’ pre-intervention scores (e.g., Al Otaiba & Fuchs, 2002; Nelson, Benner & Gonzalez, 2003) and because it will be very difficult for schools to achieve catch-up growth for children who are persistently weak responders (Al Otaiba & Fuchs, 2006; Denton et al., 2006; Wanzek & Vaughn, 2008).

However, there is a case to be made for waiting, so as to reduce the cost of false positives (providing intervention to students who would have responded to Tier 1). Evidence is accumulating that differentiated or individualized general education reduces the incidence of reading difficulties (Connor et al., in press). Further, Compton and colleagues have conducted an important series of studies to improve classification of which students will need Tier 3. They propose a two-stage screening within Tier 1 that might prevent (a) false positives- students receiving Tier 2 who do not really need it, (b) false negatives- students being missed for Tier 2 who really need it, and, perhaps most importantly, (c) waiting-to-fail students who are not likely to respond to Tier 2 and who immediately need the most intensive and extensive interventions (Compton et al., 2010; Compton et al., 2012; Fuchs, Fuchs, & Compton, 2012; Fuchs & Vaughn, 2012). In a study conducted at first grade (Fuchs et al., 2012), the model that best predicted who would need special education utilized six weeks of progress monitoring in Tier I using word identification fluency (WIF; L. S Fuchs, Fuchs & Compton, 2004); response to Tier 2 intervention did not add uniquely.

Finally, a recent study experimentally examined the impact of providing to first graders who made inadequate progress to Tier 2 either (a) an additional 7 weeks of Tier 2 or (b) 7 weeks of Tier 3 intervention (identical to Tier 2 intervention, but provided in one to one tutorials) (Gilbert et al., 2013). Gilbert and colleagues found no significant differences in reading outcomes between these two groups, but 7 weeks is a relatively brief intervention window and the quality of Tier 1 was not addressed. It was concerning that after following students to the end of third grade, students standard scores dropped and only 40% of the students who received the extended Tier 2 intervention and 53% of the students who received the Tier 3 intervention achieved grade level reading scores (above the 30th percentile). These findings led the authors to call for additional research that ensured good quality Tier 1 was implemented and that experimentally tested the impact of fast tracking students with the highest risk to Tier 3.

Purpose of the Study

These concerns about RTI implementation guided our large-scale National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Learning Disabilities Center project comparing the efficacy of two RTI models. The first model, which we termed Dynamic RTI, provided students entering first grade with the weakest skills the most intensive early literacy resources; essentially we fast-tracked students immediately to Tier 2 or Tier 3 intervention depending on their reading skill profile. The second model, which we called Typical RTI, was consistent with district policy that required students to begin in Tier 1 and progress through subsequent tiers based on continued weak skills and slow growth. Our Typical condition could be considered most similar to Compton and colleagues’ two-stage approach. Although we did not monitor progress weekly in Tier 1, we used slope (difference scores) and performance on screeners at the end of each 8-week period to make decisions about intervention sessions. While many models of RTI are currently in use, and some of these models may be similar to our Dynamic condition, to our knowledge, no similar experiments have been conducted and research is needed to compare the efficacy of different models. Therefore, we conducted a randomized control experiment with matched pairs of students (see Methods for details on matching variables) within classrooms assigned to either Dynamic or Typical RTI to compare the efficacy of the two approaches to answer the following research questions:

What are the effects of Dynamic RTI and Typical RTI on student reading outcomes by the end of first grade?

Does assignment to specific tiers predict gains on standardized assessments and does this differ when comparing Dynamic and Typical RTI groups?

Method

We contacted the school district in a mid-size city in the southeast in their first year of RTI implementation, which nominated seven schools; all principals and all 34 first grade general education teachers agreed to participate and allowed us to randomly assign children to condition within classrooms. One school was a high-performing Blue Ribbon school serving a fairly high socioeconomic neighborhood (15.8% of students at the school received Free and reduced lunch or FARL), six schools served an economically diverse range of students (FARL participation ranged from 42.8% to 89.9%). Few students were Limited English Proficient (0.4% to 2.8%). Prior to conducting the research, we received Institutional Review Board approval as well as approval from the school district’s Research Review Board.

Participants

Classroom teachers and students

A majority of the teachers (22 teachers, 64.7%) were Caucasian, nine (26.5%) were African American, one (3%) was Hispanic, one (3%) was Asian, and one (3%) was multiracial. Nine teachers held graduate degrees (26.5%) and the rest held bachelor’s degrees (77.3%). On average, teachers had taught for about 15 years (M = 14.54; SD = 9.74); 7 were relatively new to the profession (had taught 5 or fewer years); 15 were veterans (had taught over 15 years). None of the classrooms employed co-teaching and none of the special education teachers in the schools participated because special education occurred after Tier 3.

Teachers assisted us in recruiting all their students; subsequently, we received consent from 562 parents, (85% of parents agreed). During the study, 35 students (from different schools and classrooms and evenly distributed across conditions) moved to schools not participating in the study. One student exited the study by teacher request (she felt the child had improved and wanted her to receive to Tier 1 only); 5 students (all attended the school with the highest SES) exited after consultation with the school principal because of timing conflicts with special education services that began during the study. No students who could be tested were excluded from the study and hence, some children received special education services. Table 1 shows demographics, IQ scores, and descriptive statistics on screeners by their initial Tier eligibility and by condition.

Table 1.

Demographics by initial eligibility to Tier and by condition

| Tier 1 |

Tier 2 |

Tier 3 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Typical (n = 178) |

Dynamic (n = 180) |

Typical (n = 54) |

Dynamic (n = 58) |

Typical (n = 29) |

Dynamic (n = 23) |

||

| Age in years | M (SD) | 6.16 (.33) | 6.17 (.34) | 6.33 (.47) | 6.21 (.40) | 6.3 (.49) | 6.36 (.46) |

| % Male | 46.1% | 52.5% | 20.4% | 60.3% | 20.7% | 52.2% | |

| % receiving FARL | 50.0% | 48.0% | 70.4% | 67.2% | 69.0% | 91.3% | |

| Race | |||||||

| Black | % | 40.4% | 44.1% | 61.1% | 53.4% | 51.7% | 69.6% |

| White | % | 47.2% | 43.0% | 33.3% | 36.2% | 27.6% | 21.7% |

| Other | % | 12.4% | 12.8% | 5.6% | 10.3% | 20.7% | 8.7% |

| # of Students in Special Education | |||||||

| Speech Impairment | 6 | 5 | 7 | 9 | 3 | 4 | |

| Language Impairment | 3 | 2 | 3 | 7 | 4 | 4 | |

| Deaf or Hard of Hearing | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Mild ID/DD | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| Learning Disability | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 0 | |

| Emotional Handicapped | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Visual Impairment | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 0 | |

| ASD | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Verbal IQ | M (SD) | N/A | N/A | 90.78 (11.99) | 93.19 (13.44) | 89.04 (13.85) | 87.35 (11.44) |

| Nonverbal IQ | M (SD) | N/A | N/A | 90 (12.16) | 90.31 (11.58) | 85.86 (10.49) | 84.61 (10.02) |

| Initial Screen (Sept) | |||||||

| TRRP | M (SD) | 0.36 (1.13) | 0.38 (1.18) | 2.43 (1.81) | 2.40 (1.8) | 4.55 (0.51) | 4.61 (0.5) |

| LSF | M (SD) | 43.94 (12.41) | 43.93 (12.8) | 33.24 (10.70) | 34.21 (10.3) | 19.41 (9.97) | 17.43 (9.3) |

| WIF | M (SD) | 35.43 (23.68) | 39.4 (23.76) | 9.98 (6.24) | 8.41 (5.79) | 4.17 (4.15) | 4.17 (4.38) |

| SWE T | M (SD) | 94.96 (13.29) | 97.20 (13.44) | 77.74 (7.54) | 78.49 (7.01) | 72.03 (8.09) | 69.17 (7.42) |

| PDE T | M (SD) | 95.41 (12.09) | 95.56 (13.56) | 80.54 (7.99) | 83.48 (7.41) | 75.93 (5.35) | 75.35 (4.53) |

| Second Screen (Dec) | |||||||

| LSF | M (SD) | 52.52 (13.28) | 51.2 (12.52) | 45.91 (13.00) | 49.45 (13.91) | 36.76 (12.83) | 42.57 (15.15) |

| WIF | M (SD) | 54.10 (27.47) | 56.53 (25.23) | 23.96 (18.3) | 22.09 (16.13) | 10.31 (9.21) | 8.00 (6.94) |

| SWE T | M (SD) | 104.29 (14.27) | 105.84 (14.64) | 87.93 (12.99) | 89.81 (14.35) | 76.28 (9.80) | 78.23 (11.09) |

| PDE T | M (SD) | 100.37 (12.59) | 100.37 (13.26) | 86.83 (9.72) | 87.43 (9.25) | 81.69 (8.94) | 81.40 (8.25) |

| Third Screen (Mar) | |||||||

| TRRP | M | 0.25 | 0.14 | 1.37 | 1.43 | 3.655 | 3.3 |

| LSF | M (SD) | 58.3 (13.16) | 56.29 (13.68) | 51.35 (13.22) | 61.07 (14.39) | 46.17 (12.01) | 54.91 (11.97) |

| WIF | M (SD) | 66.48 (25.05) | 70.4 (23.00) | 41.78 (21.55) | 39.26 (26.03) | 18.55 (14.92) | 16.13 (13.93) |

| SWE T | M (SD) | 104.29 (14.27) | 105.84 (14.64) | 87.93 (12.997) | 89.81 (14.35) | 76.28 (8.96) | 78.22 (11.09) |

| PDE T | M (SD) | 103.01(12.82) | 104.87 (13.45) | 90.24 (11.51) | 92.83 (10.73) | 83.00 (8.98) | 88.04 (9.51) |

| Growth Z-score | |||||||

| Fall to Winter | M (SD) | 0.03 (0.62) | −0.04 (0.57) | −0.05 (0.61) | −0.00 (0.67) | −0.28 (0.53) | −0.06 (0.49) |

| Winter to Spring | M (SD) | −0.00 (0.64) | 0.07 (0.67) | 0.12 (0.54) | 0.45 (0.66) | −0.09 (0.50) | 0.19 (0.72) |

Note: FARL = Free and/or Reduced Price Lunch; ID/DD = Intellectual Disability or Developmental Disability; N/A = Not Assessed; TRRP = Teacher Rating of Reading Problems (Speece, Schatschneider, Silverman, Case, Cooper & Jacobs, 2011); LSF = AIMSWeb Letter Sound Fluency (Shinn & Shinn, 2004); WIF = Word Identification Fluency (Fuchs, Fuchs, & Compton, 2004); SWE = Sight Word Efficiency; PDE = Phonemic Decoding Efficiency; T = Standard scores on theTest of Word Reading Efficiency (Torgesen, Wagner, & Rashotte, 1999). Note that, by design, no students in Traditional RTI received Tier 2 or 3 interventions during session 1 even if they were eligible. Similarly, no students in Traditional RTI received Tier 3 until session 3.

Typical and Dynamic RTI Conditions

We carefully designed the two RTI conditions to be identical in the following three ways: (1) well-trained project staff provided the Tier 2 and 3 interventions, which supplemented classroom teacher-provided Tier 1 reading and language arts instruction; (2) students could move up to a more intensive tier if needed and could move down to a less intensive tier when they were successful for two screening periods; and (3) the standard protocols for intervention at Tier 2 and 3 (described later) were identical across conditions. Thus, the only difference between conditions was when students were provided supplemental intervention sessions.

The first RTI condition, Typical RTI, was designed to mimic two-stage school RTI decision rules recommended by Compton and colleagues and to be consistent with district implementation. In this condition, all children, regardless of their initial screening scores, began the first session in Tier 1. Then, students who demonstrated insufficient response to the Tier I instruction at the next screening (8 weeks later) were provided Tier 2 intervention during the second session (see decision-making criteria below). Subsequently, students who demonstrated insufficient response to Tier 2 intervention were provided a more intensive Tier 3 intervention during the third session. By contrast, in Dynamic RTI, students were provided Tier 2 or Tier 3 according to their initial screening or to criteria at subsequent screenings.

Procedures

Initial screening for tier eligibility and subsequent decision rules for tier sessions

In fall of first grade, well-trained graduate students administered screening and pretest measures; screening measures were used to determine initial eligibility for Tiers 1–3 and all are described later within the Measures section. A teacher rating of the severity of students’ reading difficulties relative to classmates (Speece et al., 2011) and four screeners of letter sound fluency, word reading fluency, and word attack fluency were used to determine initial eligibility (mean scores are shown in Table 1). Because schools had such variable socioeconomic status levels and reading scores, we used school/local norms or cut points to determine eligibility, but we also imposed a norm-referenced exclusion criteria (students with word identification and passage comprehension scores above a 95 were excluded because they had average reading scores).

Specifically, at the initial screening in September, students whose teachers reported they had severe reading difficulties and who scored below the 40th percentile at the school level for all four screeners were considered as initially eligible for Tier 3. The initial criterion for Tier 2 eligibility was teacher reports of severe reading difficulties or scoring below the 40th percentile at the school level for three out of four screeners. Local norms were used because we had one school with high SES; the 40th percentile was used as a cut point for low average performance. After the first 8-week session, all children (in Tiers 1–3) were again screened to re-determine local norms (this time frame corresponded to the report card period and appeared reasonable to schools for movement across tiers to occur). Students who remained below the 40th percentile on three out of four measures and who also demonstrated slopes of growth less than the mean for the entire sample moved to a more intensive tier in the next eight week session (e.g., from Tier 2 to Tier 3 in Dynamic or from Tier 1 to Tier 2 for Typical). When students were successful (i.e., they scored above the 40th percentile and demonstrated slopes of growth at or above the mean) in a tier for two consecutive eight week periods, they were exited to a less intensive tier.

Random assignment to condition

To assign students to condition, we calculated z-scores on the screeners, averaged them, rank ordered students within tier eligibility status within classroom, identified adjacent pairs in the ranking, and then randomly assigned one member of the pair to Dynamic or Typical. Table 1 provides task means and SDs based upon initial eligibility and condition. Then, after initial assignment, to determine that there were no significant differences across conditions, we conducted chi square analyses on categorical variables and ANOVAs for continuous variables that revealed no significant differences by condition on gender, ethnicity, free and reduced lunch, special education status; except for visual disabilities (p = .06), and SLD (p = .20), p-values exceeded .50.

Tier 1 Instruction: Classroom teacher training and observations of instruction

In all schools, there was a strong focus on first grade reading and language arts instruction which was provided for a minimum of 90 min and the instruction. All teachers utilized Open Court as the core reading program (Bereiter et al., 2002). To support teachers’ understanding of their role in the project and help them learn about RTI, we provided a one day professional development workshop. We used Gough’s Simple View of Reading (Gough & Tunmer, 1986) as a theoretical framework supporting the need for both code and meaning focused instruction, described the research behind three-tier RTI models, explained the importance of individualizing Tier 1, and provided a rationale for our experiment and our interventions.

In order to directly assess the quality of Tier 1 classroom instruction, staff used two digital video cameras with wide-angle lenses to videotaped the language arts 90 minute block in fall and winter (scheduled with teachers’ prior knowledge). Then, to address the overall effectiveness of implementation of literacy instruction captured on the videotapes, we used a low-inference observational instrument used in prior research (Al Otaiba, Connor et al., 2011; Al Otaiba, Folsom et al. 2011; adapted from Haager, Gersten, Baker, and Graves, 2003). Our scale ranged from 0, indicating content was not observed and, 1, 2, 3 respectively, for not effective, effective, and highly effective.

Specifically, coders used this scale to rate each component (phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension) of teachers’ reading instruction, their warmth and classroom management, and the degree to which teachers individualized instruction. During the coding meetings, any disagreements were resolved by the master coder. Inter-rater reliability was then established on 10% of the tapes and the mean Cohen’s kappa for reliability were high (.975 and .972 for fall and winter respectively). Averaged across both time points, teachers’ overall reading instruction was rated as effective (M = 1.88, SD = .36); range (1 – 2.69); classroom management ratings approached very effective (M = 2.53, SD = .46); range (1.50 – 3) as did their warmth ratings (M = 2.51, SD = .43); range (1.50 – 3). Finally, although we trained teachers to individualize instruction by forming small groups and differentiating tasks, their ratings were lower for individualization (M = 1.40, SD = 1.04); range (0 – 3).

Code and Meaning Components of Tier 2 and Tier 3 Interventions

Interventions supplemented Tier 1 instruction from October until the beginning of June, with movement across tiers each 8 weeks guided by screening data and condition. Trained research staff served as tutors for the project who conducted intervention as a pull-out in quiet classrooms or areas in the media center. We consulted with the district reading specialist to select evidence-based Tier 2 and Tier 3 that aligned with the existing Tier 1 core reading program. A standard protocol was used for content and sequencing of the lessons, but tutors were allowed to provide flexible pacing across groups to ensure mastery and were trained to use positive behavior supports.

For Tier 2, students received intervention twice a week for 30 min in groups of 4–7. We selected code-focused activities for Tier 2 from the first grade Open Court Imagine It! (Berieter et al., 2002) series and the Florida Center for Reading Research K-3 Center Activities (www.fcrr.org). For the first eight weeks, tutors spent 10 min explicitly teaching phonological awareness and letter sound skills and 10 min on decoding and sight word instruction. In the second eight week session as students mastered letter sounds and phonological awareness, relatively more time (15 min) focused on decoding, sight words, and fluency training. In the final eight week session virtually all instruction related to decoding, sight words, and fluency. Tutors provided meaning-focused instruction for about 10 min per day. In the first eight weeks, interventionists read aloud high interest trade books using dialogic reading techniques (e.g., Lonigan & Whitehurst, 1998). For the second eight weeks, as students were able to read decodable books, they read Open Court decodable books to practice fluency and answered sentence-level comprehension questions. For the final eight weeks, students read decodable books that we wrote to emphasize the text structure sequencing (i.e., first, next, and last). Tutors used graphic organizers to model and guide students in retelling stories and in writing a brief retell of the story.

For Tier 3, students received intervention four days a week for 45 min in groups of 1–3. The 30-min code-focused portion of Tier 3 consisted of Early Interventions in Reading (EIR; Mathes, Torgesen, Wahl, Menchetti, & Grek, 1999; Mathes et al., 2005). Each EIR lesson is thoroughly scripted and details exactly how to deliver explicit and systematic intervention that includes: phonemic awareness, alphabetics and phonics, and fluency. Finally, tutors provided 15 min of meaning-focused activities which were identical to Tier 2, and ensured that the decodable books were appropriate to the instructional level of Tier 3 group members.

Tutors, Training, and Treatment Fidelity

Intervention tutors included certified teachers and graduate students in special education who were research assistants. During the project, we took several steps to support implementation fidelity. The first author and three senior project staff trained tutors initially across two 8-hr days to orient them to the project, to provide training on interventions and on positive behavioral supports. We provided coaching and modeling at school sites as needed and conducted weekly meetings with tutors to examine lesson plans and discuss student progress. Tutors were observed by senior staff and they videotaped their own intervention every 8 weeks; tutors observed their videotapes and debriefed with one of two senior staff who coded the tapes for fidelity of implementation. At the end of each eight week period, prior to each time students were moving up or down tiers, meetings focused on orienting tutors to new activities and, if students were changing tiers or intervention group, allowing tutors to share information about their students (including praise and behavioral strategies that worked or favorite types of books).

Fidelity of Tier 2 and Tier 3 implementation

The videotapes of Tiers 2 and 3 were scored by a master coder and a senior staff member using a fidelity checklist (with a likert scale rating of 1 = poor, 2 = good and 3 = excellent). Inter-rater reliability of 98.1% was established. In addition to recording whether the lesson/script for each activity was followed accurately and for the appropriate time, the checklist asked the following: Was the timing accurate? Was the pacing appropriate? Did students master the lesson? Were errors corrected? Were students attentive? Fidelity ratings for the tutors ranged from .77 to .98 (M = .89).

Data Collection and Measures

All students were individually assessed by trained research staff in quiet areas near their classrooms. Prior to testing, we required staff to reach 98% accuracy on a checklist evaluating their accuracy at following administration and scoring procedures. Staff checked protocols to ensure accurate scoring and for relevant subtests, derived standard and W scores (Rasch ability scores that provide equal-interval measurement characteristics centered at 500). Due to the size and complexity of the project, all staff members were aware of assignment to condition. Under more ideal circumstances, assessors would be blind to condition, therefore, we took steps throughout the project to remind staff that the purpose of the study was to learn which condition was more effective and to caution them that experimenter bias could undermine an otherwise very carefully planned study (e.g., Rosenthal & Rosnow, 1984).

Screening and progress monitoring measures

Five assessments were used to screen students’ skills and to monitor their progress, which included the Teacher Rating of Reading Problems (Speece & Case, 2001; Speece et al., 2011) and four screening assessments that were individually administered in less than five minutes per student prior to each 8 week intervention session and at post-test. In September, teachers ranked the overall reading ability of students using a 5 point Likert scale on the Teacher Rating of Reading Problems (Speece & Case, 2001; Speece et al., 2011). Concurrent validity with standardized timed and untimed measures of reading ranged from .61 to .69. The Likert scale ranged from 5 = well above grade level, 4 = above grade level, 3 = on grade level no additional support needed, 2 = below grade level additional support needed, to 1 = well below grade level intensive support needed.

Students’ letter sound fluency (LSF) was assessed using the 1 min AIMSWEB Letter Sound Fluency (Shinn & Shinn, 2004). In this task, children are presented an array of 10 rows of 10 lower case letters per line and are asked to name as many of the sounds the letters make as quickly as they can. Testing is discontinued if no correct sounds occur in the first row. Raw scores are reported and alternate form reliability is .90. Next, we used a 1min criterion-referenced curriculum based measure, the Word Identification Fluency (WIF) task (Fuchs, Fuchs, & Compton, 2004). In this task, students read from an array of 50 first grade sight words (randomly selected from the Dolch word list of 100 frequent words). Raw scores are reported and alternate form reliability was reported to be .97 (Fuchs et al., 2004). Then, students’ word reading fluency was assessed using the two 45-second subtests of the standardized Test of Word Reading Efficiency (TOWRE; Torgesen, Wagner, & Rashotte, 1999). The Sight Word Efficiency and Phoneme Decoding Efficiency subtests require students to read sight words and nonsense words, respectively, on a list of increasing difficulty. Test-retest reliability is .90.

Additional reading assessments

We selected three norm-referenced subtests of the Woodcock Johnson-III (WJ-III;) (Woodcock et al., 2001) to assess word reading, decoding and comprehension; the test manual reports reliability of .91, .94 and .83 respectively. The Letter Word Identification subtest requires students to identify letters in large type, and then to read increasingly difficult words. The Word Attack subtest initially requires students to identify the sounds of a few single letters and progress to decoding items of increasingly complex letter combinations that follow regular patterns in English orthography, but that are nonwords. Reading comprehension was assessed using the norm-referenced Passage Comprehension subtest, a cloze task that requires students to identify a missing key word that is consistent with the context of a written passage. Initially, examiners read the sentence and items have pictures, but later students must read the sentence or passage and identify the missing key word.

Finally, we assessed oral reading fluency as an outcome posttest using the Dynamic Indicators of Basic Early Literacy Skills (DIBELS; Good & Kaminski, 2002) Oral Reading Fluency measure. Students read a grade-level previously unseen passage and the score is the number of correct words per min. Test-retest reliability for elementary students is .92.

Results

Research Question 1: What are the effects of Dynamic RTI and Typical RTI on student reading outcomes?

The first research question compared the effects of the two RTI conditions on student reading outcomes. We first examined the multiple outcome measures using principal component analysis in order to avoid multiple analyses. Results revealed that the assessments loaded on one factor and so factor scores were created; one for the fall assessments (see Table 2, top) and one for the spring assessments (see Table 2, bottom). These variables were used in subsequent analyses (Fall Reading and Spring Reading, respectively). There were no significant differences in Fall Reading factor scores for students in the Dynamic RTI compared to the Typical RTI groups [t (553) = .981, p = .327, CI = −.083–.249]. Next, we examined the overall intent-to-treat effect using hierarchical linear modeling (HLM), because children were nested in classrooms and HLM accommodates such data (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002). The unconditional model with the Spring Reading factor score revealed an intraclass correlation (ICC) of .250 (i.e, proportion of between classroom variance). Results of the analyses (see Table 3) revealed that students in the Dynamic RTI group had statistically significantly higher Spring Reading scores than did students in Typical RTI, with an effect size (Hedges g1) of .314, which is a moderate effect (Hill, Bloome, Black, & Lipsey, 2008), with practical importance (What Works Clearinghouse; http://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/).

Table 2.

Results of Principal Component Analyses for Pre- and Posttreatment (Fall/Spring) Reading Outcomes

| Variable | Component 1 |

|---|---|

| Fall Component Matrix | |

| Letter Word Identification W | 0.963 |

| Word Attack W | 0.849 |

| Passage Comprehension W | 0.896 |

| Word Identification Fluency F | 0.95 |

| Letter Sound Fluency A | 0.63 |

| Phonemic Decoding Efficiency T | 0.913 |

| Oral Reading Fluency D | 0.93 |

| Spring Component Matrix | |

| Letter Word Identification W | 0.816 |

| Word Attack W | 0.826 |

| Passage Comprehension W | 0.864 |

| Word Identification Fluency F | 0.882 |

| Letter Sound Fluency A | 0.302 |

| Phonemic Decoding Efficiency T | 0.887 |

| Sight Word Efficiency T | 0.94 |

| Oral Reading Fluency D | 0.922 |

| TRRP | −0.688 |

Note. For both Primary Component Analsyes, only one component was extracted. W = Woodcock-Johnson III Test of Achievement (Woodcock, McGrew, & Mather, 2001); F = Word Identification Fluency (Fuchs, Fuchs, & Compton, 2004); A = AIMSWeb (Shinn & Shinn, 2004); T = Test of Word Reading Efficiency (Torgesen, Wagner, & Rashotte, 1999); D = Dynamic Indicators of Basic Early Literacy Skills (Good & Kaminski, 2002); TRRP = Teacher Rating of Reading Problems (Speece, Schatschneider, Silverman, Case, Cooper & Jacobs, 2011)

Table 3.

HLM Results of Intent-to-Treat Analysis

| Fixed Effect | Coefficient | SE | T-ratio | Df | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −0.10 | 0.10 | −1.07 | 33 | .294 |

| Dynamic RTI | 0.17 | 0.05 | 3.19 | 527 | .002 |

| Random Effect | Sd | Var. | Df | χ2 | P |

| Intercept | 0.50 | 0.25 | 33 | 201.73 | <.001 |

| Level 1 | 0.86 | .74 | |||

Note. Deviance = 1342.56

Research Question 2: Does assignment to specific tiers predict gains on standardized assessments and does this differ when comparing Dynamic and Typical RTI groups?

The second research question explored whether assignment to tiers was related to reading growth on a standardized assessment. We used the spring WJ-III Brief Reading W score as the outcome so we could examine growth in scores over the school year, which was not possible with the reading factor scores. There were no significant between group differences in fall Brief Reading W scores [t(554) = 1.387, p = .166, CI = −1.391–8.081]. We then examined spring Brief Reading W scores as a function of the tier students were initially eligible for utilizing latent growth curve HLM (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002). We entered the variable tier (1, 2 or 3) as a time-varying covariate at level 1 where time was in months and centered at the end of the year. We did this because students moved from tier to tier across the three sessions during first grade (see Table 4 and Figure 2). Condition was entered at level 2, the student level. Results revealed that there were no significant differences by condition in growth over time for students who were eligible for Tier 1 only instruction (blue solid and dotted lines). This finding is expected given that children were randomly assigned to condition within classrooms; thus students in both conditions who were eligible for Tier 1 only received only instruction by their classroom teacher. Students who received Tier 2 interventions had lower scores than did students who were eligible for only Tier 1 instruction. Tier 2 students in the Dynamic RTI condition had significantly higher reading outcomes scores compared to students initially eligible for Tier 2 in Typical RTI, who by design only received Tier 2 if they did not respond to Tier 1 over the first or second session. Not surprisingly, students initially eligible for Tier 3 had the weakest scores over the school year, but students initially eligible for Tier 3 who received the Tier 3 intervention immediately because they were in Dynamic RTI achieved higher Brief Reading scores compared to Tier 3 students in Typical RTI who had to wait until the beginning of Session 3.

Table 4.

Latent Growth Curve Analysis of Brief Reading Scores Across 1st Grade as a Function of Tier and Status

| Fixed Effect | Coefficient | SE | T-ratio | Df | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 489.22 | 2.49 | 196.18 | 33 | <0.001 |

| Dynamic | −2.43 | 2.58 | −0.94 | 518 | 0.347 |

| Tier | −15.48 | 1.15 | −13.42 | 470 | <0.001 |

| Tier × Dynamic | 3.81 | 1.52 | 2.51 | 470 | 0.012 |

| Slope | 4.66 | 0.12 | 37.36 | 518 | <0.001 |

| Dynamic | −0.03 | 0.18 | −0.16 | 518 | 0.872 |

| Random Effect | Sd | Var. | Df | χ2 | P |

| Level 2 | |||||

| Intercept | 11.47 | 131.57 | 503 | 1193.84 | <0.001 |

| Slope | 0.75 | 0.57 | 536 | 620.37 | 0.007 |

| Level 1 | 10.83 | 117.32 | |||

| Level 3 | |||||

| Intercept | 9.32 | 86.791 | 33 | 253.07 | <0.001 |

Note. Deviance = 13378.06. Latent growth curve analysis of Brief Reading Scores across the school year as a function of Tier (1, 2 or 3) as a time-varying covariate and Dynamic versus Traditional RTI. Time is in months centered at the end of the year.

Figure 2.

Latent Growth Curve Model of Brief Reading

Note. Latent growth of Brief Reading over the school year as a function of condition and initial tier eligibility.

DISCUSSION

In order to understand the effects of fast tracking students with the weakest initial skills to the most intensive treatment, we conducted a randomized control experiment with matched pairs of students within classrooms assigned to either Dynamic or Typical RTI, which required students to begin in Tier 1 and waited for their response. By design, both conditions were identical in that teachers used the same core reading program, which was implemented effectively and interventionists provided the same Tier 2 and 3 interventions, which were implemented with fidelity; the only difference across conditions was when the supplemental Tier 2 and 3 interventions began. The study was conducted for a full school year and was unique relative to prior RTI investigations in both allowing movement across tiers every 8 weeks in tandem with report card periods and in allowing fast tracking to Tier 3 for the most needy students. As some districts may use versions of RTI that are similar to both conditions, our study may inform the controversy in the field of special education about ensuring RTI not become another wait to fail model (e.g., Denton et al., 2006, Fuchs et al., 2010, Vaughn et al., 2010).

When addressing the first research question, regarding the effects of Dynamic RTI and Typical RTI on student reading outcomes by the end of first grade, we used an intent-to-treat analysis that accounted for nesting by using HLM. Findings revealed the Dynamic condition was more effective than the Typical RTI. The effect size was moderate (ES = .36), which exceeds the .25 recommended by the What Works Clearing House (http://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/) for a substantively important finding that meets study standards for evidence-based practices. We cannot directly compare this effect size with prior studies including Tier 3 interventions because of differences in initial criteria, definitions of responsiveness, and limited study of movement within a study year. However, this finding extends prior the research (Compton et al., 2012; Gilbert et al., 2013; Vaughn & Fletcher, 2012; Vaughn et al., 2009) that multi-tier models have potential to improve reading growth and that not all students need to go through Tier 1 or Tier 2.

Given that students’ performance on standardized reading scores is a hallmark of their reading skill, our second research question examined whether there were interactions between assignment to tiers and condition that were related to performance on these measures. As expected, given screening for tiers, at the onset, students eligible for Tier 3 performed significantly lower than students eligible for Tier 2. It was possible to identify students who needed the most intensive intervention using brief screeners (approximately 3–5 min of assessment) and a Teacher Rating of Reading Severity (Speece & Case, 2001). Also as expected, due to random assignment of students within classrooms to condition, there were no significant differences in outcomes for students within Tier 1 across the two conditions. Further, we carefully documented that Tier 1 was effective, which has not routinely been established in prior research (Hill, King, Lemons & Partanen, 2012).

There was a significant interaction between Tier 2 and Tier 3 and condition, indicating students in the Dynamic condition achieved higher Brief Reading skills than students in the Typical condition. Given that students were equal at pretest due to random assignment, that they received the same Tier 1, and that they received the same interventions in both conditions, all add confidence that fast-tracking through the Dynamic condition led to significantly higher reading outcomes. Encouragingly, only a small percentage of students ended first grade with standard scores below 91 (the 25th percentile) for word reading (4.30% on word attack and 7.20% on letter word identification); however, in terms of their comprehension, 19.40% had standard scores below 91 on passage comprehension). Such variability across measures is consistent with prior research (e.g., Gilbert et al., 2013; O’Connor et al., 2005; Vaughn et al., 2009; Vellutino et al., 2006).

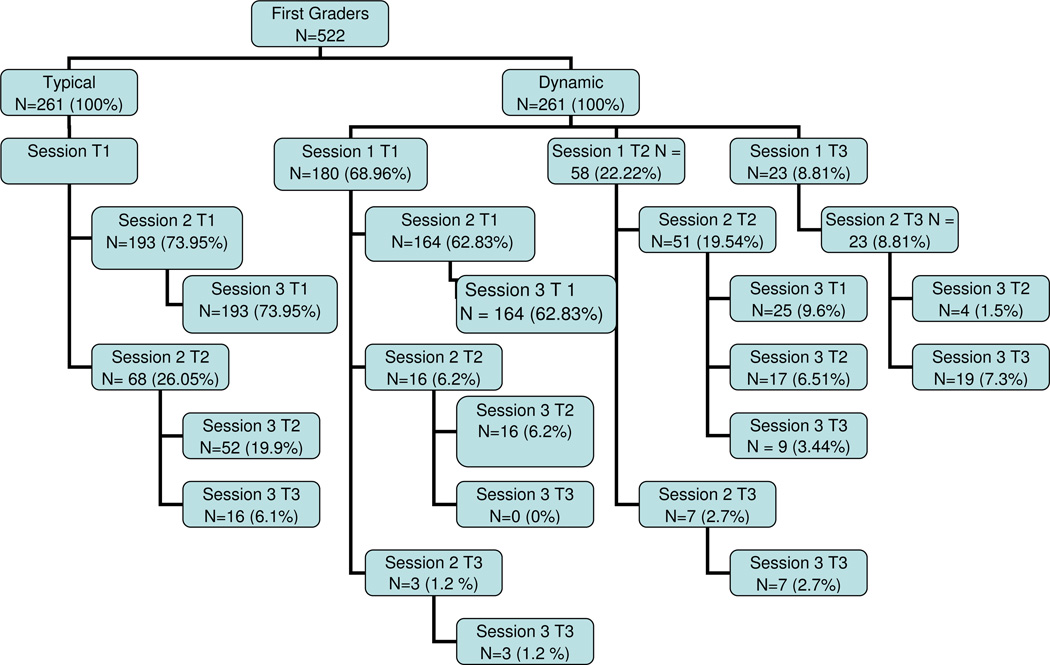

Although the purpose of this paper was not to specifically analyze our classification accuracy, or to statistically analyze sensitivity and specificity, several indicators suggest that across the year, children who needed intervention received it and that the impact of unnecessary Tier 2 and 3 appeared to be negligible. First, had there been false positives, it would be likely that Tiers might not be significantly different, but they were clearly distinguishable on all measures. Further Table 1 shows that students initially eligible for Tier 3 had standard scores about 1.5 standard deviations lower than peers in Tier 1; students in Tier 2 had mean standard scores between a half to a whole SD lower than students in Tier 1. In addition, if false positives were an issue in the Dynamic condition, then they would not have screened eligible by the second session, but Figure 1 shows that of 23 students were fasted tracked to Tier 3, only 4 responded well enough to be eligible to return to Tier 2 (only by the third intervention session). Of the 58 students fast tracked to Tier 2 in the Dynamic condition, 51 remained eligible for Tier 2 at the second session screening and the remaining 7 were eligible for Tier 3 (through the end of the study); by the third screening session, it was encouraging that 25 of the original 58 students in Tier 2 responded well enough to return to Tier 1. Thus, taken together, it seems unlikely that the students were false positives, and that intervention was warranted.

Figure 1.

This is the figure that shows the movement from Tier to Tier over the school year

Second, with regard to false negatives, or students being missed for Tier 2 or Tier 3 who really need it, as shown in Figure 1, in the Dynamic condition, 180 students initially screened as eligible for Tier 1 and of these, only 19 of them scored as needing Tier 2 in the second session and only three scored as needing Tier 3 in the third session. By contrast, In the Typical condition whereby all students began in Tier 1, by the second intervention session, 68 (26%) screened eligible for Tier 2, and by the third intervention session, 16 screened eligible for Tier 3. Arguably, these 16 children may have waited too long for intervention. Thus, with regard to students waiting too long in Tier 2 in the Dynamic condition, of the 58 students who began in Tier 2, 51 again screened eligible for Tier 2 in the second session (and 7 screened eligible for Tier 3); and by the third session, an additional 9 screened eligible for Tier 3. Thus our findings extend work by O’ Connor et al., 2005 supporting the merit of movement within RTI systems, 8 week periods were feasible to track progress, and furthermore fast-tracking is also promising, rather than forcing students to wait for more intense intervention. We contend that fast tracking may also be more in line with the very concept of a free and appropriate public education (FAPE) under IDEA 2004. However, even fast tracking was not able to consistently close the reading gap; that cautionary note is consistent with all other RTI investigations to date that have included Tier 3 (Denton et al., 2006; Gilbert et al., 2013; O’Connor et al., 2005; Vaughn et al., 2009; Vellutino et al., 2008; Wanzek & Vaughn, 2010).

Implications for Practice and Challenges that Arose

We hope that lessons we learned, including the challenges we faced, can guide future RTI research and practice. Based on our findings and prior research, there appears converging evidence that it is possible to identify, at the start of first grade, which children will need the most intensive intervention. Further, the present study used an experimental design to show that when students with the weakest initial skills received the most intensive intervention (through the Dynamic condition), their reading performance was significantly stronger at the end of the year than students in the Typical condition where students waited for 8 weeks before moving into Tier 2 or 3. The 8 week sessions were feasible for change and related to report card periods. In retrospect, we feel it was a good decision to add the meaning-focused modules to both Tier 2 and 3, beginning with dialogic reading, reading decodable texts and reading and responding to decodable texts we wrote to target the sequencing text structure. Similarly, our decision to use local norms, along with the Teacher Rating of Reading Severity (Speece & Case, 2001; Speece et al., 2011), rather than a standard score to assign children to tiers led to good buy-in from schools and teachers. Indeed, our data were used by schools in their initial RTI meetings, which was helpful to principals in their first implementation year of RTI in the district.

We did face several challenges that schools would likely face as well in conducting this study. Most importantly, students in Tier 3 did not catch up to students in Tier 1. This finding is consistent with the research including Tier 3 reading interventions, thus it is likely they will need continued help that may include special education (Denton et al., 2006; Gilbert et al., 2013; O’Connor et al., 2005; Vaughn et al., 2009; Vellutino et al., 2008). O’Connor et al (2006) reported 60% of students who received intervention (K-third grade) and qualified for Tier 3 could not read on grade level at the end of third grade. In addition, a sobering finding from longitudinal research is that when interventions have stopped at the end of first grade, students’ standard scores slid, so by the end of third grade, Vellutino et at al found nearly a third of students read below the 30th percentile and Gilbert found even higher proportions reading below this benchmark (60% and 46%, respectively of students who received Tier 2 and Tier 3).

Second, we believe schools will need to be prepared to be flexible in RTI implementation. Although we initially conceptualized the interventions as standard protocols so that we could determine that interventions were completed with fidelity, across the year, it was necessary to individualize pacing, to regroup some students due to behavioral or personality issues, to regroup to minimize heterogeneity of skills and to tailor readability of text to the group need. Further, when it was time to move students down from Tier 3 to Tier 2, we wished we had a Tier 2.5; that is because by then the Tier 2 groups were so much further ahead in terms of the amount of text they could independently read as well as the phonic rules and sight words they had mastered. An important implication is that researchers and schools will likely grapple with using data to ensure that interventions are at the appropriate instructional level, or “sweet spot,” for individual students. Another research group has also used data-based regrouping, but for Tier 2 in kindergarten. Coyne and colleagues (Coyne et al., 2012; Lentini & Coyne, in press) used curriculum mastery data to keep groups more homogenous, to adjust the pace of instruction, to release strong responders to Tier 1, and to enroll weaker students into Tier 2 and found students in the regrouping condition outperformed peers in the standard intervention group.

Finally, although we had initially thought Tier 2 would be easier for interventionists than Tier 3, given the larger sizes of the group in Tier 2, with subsequently more heterogeneity of skills, and given that the code-focused aspect of Tier 2 intervention was less scripted than Tier 3, it took more careful planning. Finally, although we worked closely with school leaders during the project, it was very challenging to schedule intervention, particularly moving across sessions.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

As with most school-based research, there are some potential limitations to our study findings; some lead to directions for future research. First, as mentioned previously, assessors were not blind to students’ condition due to the size and complexity of the project. Although we took care to train staff that this was a true experiment to learn which condition was most efficacious, future research should use stronger design and engage a separate team of assessors. Second, we did not test for specificity of or sensitivity of classification and additional research is needed using methods such as receiver-operator curves. Relatedly, future research is needed to analyze profiles of these inadequate responders, to track their reading trajectories and special education classification longitudinally, and learn more about school-delivered interventions.

Third, our findings might differ had we selected students using national rather than local norms or if the movement rules across tiers differed. Clearly there is a need for future research to establish criteria for responsiveness and movement, even though our criteria appeared feasible and efficient. Fourth, our participants included only beginning first graders and so findings may not generalize to older students. Additional research for persistently poor readers beyond primary grades is needed. Fifth, our findings may not generalize to schools with weaker or different Tier 1 instruction. All of our teachers used the same systematic core, which we observed to be effectively implemented through observations and also as indicated by standard scores for students who only participated in Tier 1. Thus, research is warranted with different populations and instructional core reading programs.

Sixth, although we considered it a strength of our study that we chose to use a standard treatment protocol and selected Tier 2 and Tier 3 intervention that aligned with the core and supported by the local school district, future research is needed to examine other interventions and to compare conditions like our Dynamic condition to problem solving protocols, particularly in Tier 3. For example, there has been some promising work using Brief Experimental Analysis (e.g., Burns & Wagner, 2008) to identify optimal interventions for individual children.

Summary

In summary, the results of this randomized control trial revealed that immediately providing Tier 2 and 3 interventions to students who qualify, rather than Typical RTI (which waited for students to respond to Tier 1 for 8 weeks before providing intervention, thus resulting in the most intensive interventions being delayed), led to generally stronger reading outcomes by the end of first grade. RTI protocols have shown promise in preventing reading difficulties related to inadequate instruction. Nevertheless, there is marked variation in how and when students receive supplemental intervention. Dynamic RTI protocols, such as the one used in this study, suggest that there is no reason to delay intervention, that any effect of false negatives is negligible, and that, broadly implemented, Dynamic RTI, including a foundation of effective Tier 1 instruction, can improve reading outcomes for all children.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by (a) a Multidisciplinary Learning Disabilities Center Grant P50HD052120 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

References

- Al Otaiba S, Connor CM, Folsom JS, Greulich L, Meadows J, Li Z. Assessment data-informed guidance to individualize kindergarten reading instruction: Findings from a cluster-randomized control field trial. The Elementary School Journal. 2011;111(4):535–560. doi: 10.1086/659031. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/659031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al Otaiba S, Connor CM, Foorman BR, Greulich L, Folsom JS. Implementing response to intervention: The synergy of beginning reading instruction and early intervening services. In: Scruggs TE, Mastropieri MA, editors. Advances in Learning and Behavioral Difficulties, Volume 22, Policy and Practice. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Al Otaiba S, Folsom JS, Schatschneider C, Wanzek J, Greulich L, Meadows J, Connor CM. Predicting first-grade reading performance from kindergarten response to tier 1 instruction. Exceptional Children. 2011;77(4):453–470. doi: 10.1177/001440291107700405. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/881461162?accountid=4840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al Otaiba S, Fuchs D. Characteristics of children who are unresponsive to early literacy intervention. A review of the literature. Remedial and Special Education. 2002;23(5):300–316. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/07419325020230050501. [Google Scholar]

- Al Otaiba S, Fuchs D. Who are the young children for whom best practices in reading are ineffective? an experimental and longitudinal study. Journal of Learning Disabilities. 2006;39(5):414–431. doi: 10.1177/00222194060390050401. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/62016981?accountid=4840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bereiter C, Brown A, Campione J, Carruthers I, Case R, Hirshberg J, Adams MJ, McKeough A, Pressley M, Roit M, Scardamalia M, Treadway GH., Jr . Open Court Reading. (Grades K-6 reading and writing program) Columbus, Ohio: SRA/McGraw-Hill; 2000/2002. [Google Scholar]

- Compton DL, Fuchs D, Fuchs LS, Bouton B, Gilbert JK, Barquero LA, Crouch RC. Selecting at-risk first-grade readers for early intervention: Eliminating false positives and exploring the promise of a two-stage gated screening process. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2010;102(2):327–340. doi: 10.1037/a0018448. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0018448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton DL, Gilbert JK, Jenkins JR, Fuchs D, Fuchs LS, Cho E, Bouton B. Accelerating chronically unresponsive children to tier 3 instruction: What level of data is necessary to ensure selection accuracy? Journal of Learning Disabilities. 2012;45(3):204–216. doi: 10.1177/0022219412442151. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0022219412442151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor CM, Morrison FJ, Fishman B, Crowe EC, Al Otaiba S, Schatschneider C. A Longitudinal Cluster-Randomized Control Study on the Accumulating Effects of Individualized Literacy Instruction on Students’ Reading from 1st through 3rd Grade. Psychological Science. in press doi: 10.1177/0956797612472204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne MD, Simmons DC, Simmons LE, Hagan-Burke S, Kwok O, Kim M, Fogarty M, Oslund E, Taylor A, Capozzoli-Oldham A, Ware S, Little ME, Rawlinson DM. Adjusting beginning reading intervention based on student performance: An experimental evaluation. Exceptional Children. in press [Google Scholar]

- Denton CA, Fletcher JM, Anthony JL, Francis DJ. An evaluation of intensive intervention for students with persistent reading difficulties. Journal of Learning Disabilities. 2006;39(5):447–466. doi: 10.1177/00222194060390050601. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/00222194060390050601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs D, Fuchs LS, Compton DL. Identifying reading disabilities by responsiveness-to-instruction: Specifying measures and criteria. Learning Disability Quarterly. 2004;27(4):216–227. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1593674. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs D, Fuchs LS, Compton DL. Smart RTI: A next-generation approach to multilevel prevention. Exceptional Children. 2012;78(3):263–279. doi: 10.1177/001440291207800301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs LS, Vaughn S. Responsiveness-to-intervention: A decade later. Journal of Learning Disabilities. 2012;45(3):195–203. doi: 10.1177/0022219412442150. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0022219412442150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gersten R, Compton D, Connor CM, Dimino J, Santoro L, Linan-Thompson S, Tilly WD. Assisting Students Struggling with Reading: Response to Intervention (RtI) and Multi-Tier Intervention in the Primary Grades. 2009 Retreived from http://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/PracticeGuide.aspx?sid=3.

- Gilbert JK, Compton DL, Fuchs D, Fuchs LS, Bouton B, Barquero LA, Choo E. Efficacy of a First-Grade Responsiveness-to-Intervention Prevention Model for Struggling Readers. Reading Research Quarterly. 2013;48(2):135–154. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/rrq.45. [Google Scholar]

- Good RH, Kaminski RA, editors. Dynamic Indicators of Basic Early Literacy Skills. 6th ed. Eugene, OR: Institute for Development of Educational Achievement; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gough PB, Tunmer WE. Decoding, reading, and reading disability. Remedial and Special Education (RASE) 1986;7(1):6–10. [Google Scholar]

- Haager D, Gersten R, Baker S, Graves A. The English language learner observation instrument for beginning readers. In: SV, Briggs KL, editors. Reading in the classroom: Systems for the observation of teaching and learning. Baltimore, MD: Brookes; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hill CJ, Bloom HS, Black AR, Lipsey MW. Empirical benchmarks for interpreting effect sizes in research. Child Development Perspectives. 2008;2(3):172–177. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-8606.2008.00061.x. [Google Scholar]

- Hill DR, King SA, Lemons CJ, Partanen JN. Fidelity of Implementation and Instructional Alignment in Response to Intervention Research. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice (Blackwell Publishing Limited) 2012;27(3):116–124. [Google Scholar]

- Lentini AR, Coyne MD. Addressing False Positives in Early Reading Assessment Using Intervention Response Data. manuscript submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- Lonigan CJ, Whitehurst GJ. Relative efficacy of parent and teacher involvement in a shared-reading intervention for preschool children from low-income backgrounds. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 1998;13(2):263–290. [Google Scholar]

- Mathes PG, Denton CA, Fletcher JM, Anthony JL, Francis DJ, Schatschneider C. The effects of theoretically different instruction and student characteristics on the skills of struggling readers. Reading Research Quarterly. 2005;40(2):148–182. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1598/RRQ.40.2.2. [Google Scholar]

- Mathes PG, Torgesen JK, Wahl M, Menchetti JC, Grek ML. Proactive beginning reading: Intensive small group instruction for struggling readers. Dallas TX: Southern Methodist University; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Mellard D, McKnight M, Jordan J. RtI tier structures and instructional intensity. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice. 2010;25:217–225. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson JR, Benner GJ, Gonzalez J. Learner characteristics that influence the treatment effectiveness of early literacy interventions: A meta-analytic review. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice. 2003;18(4):255–267. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1540-5826.00080. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor RE, Harty KR, Fulmer D. Tiers of intervention in kindergarten through third grade. [RtI] Journal of Learning Disabilities. 2005;38(6):532–538. doi: 10.1177/00222194050380060901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush Stephen W, Bryk Anthony S. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. second ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal R, Rosnow RL. Applying hamlet’s question to the ethical conduct of research: A conceptual addendum. American Psychologist. 1984;39(5):561–563. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.39.5.561. [Google Scholar]

- Shinn MM, Shinn MR. AIMSweb. Eden Prairie, MN: Edformation; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Speece DL, Case LP. Classification in context: An alternative approach to identifying early reading disability. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2001;93(4):735–749. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.93.4.735. [Google Scholar]

- Speece DL, Schatschneider C, Silverman R, Case LP, Cooper DH, Jacobs DM. Identification of reading problems in first grade within a response-to-intervention framework. Elementary School Journal. 2011;111(4):585–607. doi: 10.1086/659032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torgesen JK, Wagner R, Rashotte CA. Test of word reading efficiency. Austin, TX: PRO-ED; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn S, Denton CA, Fletcher JM. Why intensive interventions are necessary for students with severe reading difficulties. Psychology in the Schools. 2010;47(5):432–444. doi: 10.1002/pits.20481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn S, Linan-Thompson S, Hickman P. Response to instruction as a means of identifying students with Reading/Learning disabilities. Exceptional Children. 2003;69(4):391–409. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn S, Wanzek J, Linan-Thompson S, Murray CS. Monitoring response to supplemental services for students at risk for reading difficulties: High and low responders. In: Jimerson SR, Burns MK, VanDerHeyden AM, editors. Handbook of response to intervention: The science and practice of assessment and intervention. NY, NY: Springer; 2007. pp. 234–243. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn S, Wanzek J, Murray CS, Scammacca N, Linan-Thompson S, Woodruff AL. Response to early reading intervention examining higher and lower responders. Exceptional Children. 2009;75(2):165–183. [Google Scholar]

- Vellutino FR, Scanlon DM, Zhang H, Schatschneider C. Using response to Kindergarten and first grade intervention to identify children at-risk for long term reading disability. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal. 2008;21(4):437–480. [Google Scholar]

- Wanzek J, Vaughn S. Research-based implications from extensive early reading interventions. School Psychology Review. 2007;36(4):541–561. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/622074095?accountid=4840. [Google Scholar]

- Wanzek J, Vaughn S. Response to varying amounts of time in reading intervention for students with low response to intervention. Journal of Learning Disabilities. 2008;41(2):126–142. doi: 10.1177/0022219407313426. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/61961802?accountid=4840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanzek J, Vaughn S. Tier 3 interventions for students with significant reading problems. Theory into Practice. 2010;49(4):305–314. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/815959503?accountid=4840. [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock RW, McGrew KS, Mather N. Woodcock-Johnson III Tests of Cognitive Ability. Itasca, IL: Riverside; 2001. Examiner’s manual. [Google Scholar]

- Zirkel PA, Thomas LB. State laws for RTI: An updated snapshot. Teaching Exceptional Children. 2010;42(3):56–63. [Google Scholar]