An enhanced understanding of the biology of breast cancer metastases is needed to individualize patient management. Here, we show that tumor characteristics of breast cancer metastases significantly influence post-relapse survival, emphasizing that molecular investigation at relapse offers clinically relevant information, with the potential to improve patient management and survival.

Keywords: breast cancer metastases, metastasis characteristics, TEX randomized trial, gene expression, gene modules, biopsy at relapse

Abstract

Background

We and others have recently shown that tumor characteristics are altered throughout tumor progression. These findings emphasize the need for re-examination of tumor characteristics at relapse and have led to recommendations from ESMO and the Swedish Breast Cancer group. Here, we aim to determine whether tumor characteristics and molecular subtypes in breast cancer metastases confer clinically relevant prognostic information for patients.

Patients and methods

The translational aspect of the Swedish multicenter randomized trial called TEX included 111 patients with at least one biopsy from a morphologically confirmed locoregional or distant breast cancer metastasis diagnosed from December 2002 until June 2007. All patients had detailed clinical information, complete follow-up, and metastasis gene expression information (Affymetrix array GPL10379). We assessed the previously published gene expression modules describing biological processes [proliferation, apoptosis, human epidermal receptor 2 (HER2) and estrogen (ER) signaling, tumor invasion, immune response, and angiogenesis] and pathways (Ras, MAPK, PTEN, AKT-MTOR, PI3KCA, IGF1, Src, Myc, E2F3, and β-catenin) and the intrinsic subtypes (PAM50). Furthermore, by contrasting genes expressed in the metastases in relation to survival, we derived a poor metastasis survival signature.

Results

A significant reduction in post-relapse breast cancer-specific survival was associated with low-ER receptor signaling and apoptosis gene module scores, and high AKT-MTOR, Ras, and β-catenin module scores. Similarly, intrinsic subtyping of the metastases provided statistically significant post-relapse survival information with the worst survival outcome in the basal-like [hazard ratio (HR) 3.7; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.3–10.9] and HER2-enriched (HR 4.4; 95% CI 1.5–12.8) subtypes compared with the luminal A subtype. Overall, 25% of the metastases were basal-like, 32% HER2-enriched, 10% luminal A, 28% luminal B, and 5% normal-like.

Conclusions

We show that tumor characteristics and molecular subtypes of breast cancer metastases significantly influence post-relapse patient survival, emphasizing that molecular investigations at relapse provide prognostic and clinically relevant information.

ClinicalTrials.gov

This is the translational part of the Swedish multicenter and randomized trial TEX, clinicaltrials.gov identifier nct01433614 (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/nct01433614).

introduction

Breast cancer is widely recognized as a heterogeneous disease in the sense of both primary tumor metastatic capacity and time to metastatic spread of disease. Treatment with endocrine therapy is a major cornerstone in the management of breast cancer and has considerably improved patient survival. However, despite considerable progress, one of five women with early-stage breast cancer will later develop distant metastatic disease [1].

We and others have recently shown that tumor characteristics are altered throughout tumor progression [2–4], which significantly influences patient survival [2, 5]. These findings emphasize the need for re-examination of tumor characteristics at relapse to improve patient management and have led to recommendations from the ABC1, ASCO, ESMO, and Swedish Breast Cancer group (SweBCG), among others, regarding the re-evaluation of metastatic lesions for expression of estrogen (ER), progesterone (PR), and human epidermal receptor 2 (HER2) [6–8].

Here, we aimed to enhance our understanding of the biology of breast cancer metastases in relation to post-relapse survival and to assess tumor characteristics with previously demonstrated prognostic significance in the primary tumor setting to understand their importance in metastatic disease. Our goal in doing so is to provide biologically relevant information that will help to guide individualized patient management. We analyzed tumor characteristics from one or more metastases of 111 breast cancer patients enrolled in the Swedish multicenter prospective and randomized TEX [Taxol® (paclitaxel): Bristol-Myers Squibb AB, Sweden; Farmorubicin® (epirubicin): Pfizer AB, Sweden; Xeloda® (capecitabine): Roche AB, Sweden] trial.

patients and methods

The Swedish multicenter and randomized trial TEX [9], ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01433614 (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01433614), enrolled 287 patients with a morphologically confirmed locoregional or distant breast cancer relapse from December 2002 until June 2007. Previous endocrine treatment of advanced disease in patients with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer was allowed. In addition, previous treatment with an anthracycline, a taxane, or 5-FU was allowed if the last course of chemotherapy was given at least 1 year before TEX study entry. Patients were randomly assigned to first-line chemotherapy with a combination of epirubicin and paclitaxel alone or in combination with capecitabine. Detailed clinical information and complete follow-up were available for all included patients.

Patients with metastatic lesions accessible for either a fine-needle aspiration (FNA) or a core biopsy were asked to give a sample, but sampling was optional. We defined the site of relapse as the site where the metastatic biopsy was taken. The most common biopsy sites were lymph nodes (36.7%), liver (22.5%), skin (18.3%), and breast (15.8%). In total, tumor tissue was available from 149 of 287 patients.

The translational aspect of the trial included 120 relapse biopsies (116 FNA biopsies and 4 core biopsies) from 111 patients yielding sufficient tumor RNA for gene expression profiling. The clinical and pathological patient characteristics of the translational TEX trial were representative of the original TEX trial.

Details of the HRSTA-2.0 custom human Affymetrix array GPL10379 are available at NCBI GEO depository as GPL10379 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GPL10379). Briefly, this whole-genome array contains 52 378 individual probe sets, with each probe set containing 4–20 individual probes. The gene expression microarray data have been deposited into the Gene Expression Omnibus under the accession number of GSE56493.

This study was approved by the Ethics committee at Karolinska Institutet and the other participating centers. All patients have given written informed consent.

statistical methods

preprocessing and normalization

The relapse tumor gene expression analyses were performed in the open-source software R using the aroma.affymetrix package [10]. Each gene expression array was individually background corrected and normalized using robust multichip averaging; no arrays were identified as having poor quality. The quality of the arrays was assessed utilizing Normalized Unscaled Standard Error plots and Relative Log Expression plots.

survival analysis

Patient follow-up started at the date of the TEX study enrollment and ended at the date of death, or at the end of study follow-up, 1 July 2013. We carried out Kaplan–Meier and multivariate proportional hazard (Cox) analyses adjusting for calendar year and age at diagnosis in addition to the TEX clinical study treatment arms. We did not adjust for additional tumor characteristics due to sample size. The proportional hazard assumption for the main exposure variables was assessed including a time-dependent covariate in the survival model. No significant deviation was noted.

Breast cancer-specific survival was used as the end point. Post-relapse patient survival was defined as short-term (up to 1.5 years post-relapse survival) and long-term survival (up to 5 years or more). The short-term survival cutoff (1.5 years post-relapse survival) was defined retrospectively by applying a model of two normal distributions, in order to capture the visually apparent survival distribution, using the mixtools package in R [11]. A full description of this is provided in supplementary Materials and methods, available at Annals of Oncology online.

intrinsic subtype

We assessed the intrinsic subtypes (PAM50) for each relapse using the TEX metastasis gene expression arrays as previously described; full details are provided in supplementary Materials and methods, available at Annals of Oncology online [12].

gene modules

To characterize the tumor biology of the breast cancer relapses, we applied the set of 7 gene expression process modules and 10 pathway modules as previously described [13, 14]. Each module is comprised of genes both positively and negatively associated with the gene of interest (e.g. ESR1) and the module as a whole is representative of a biological process/pathway. We computed the module score for every gene module in the relapses and divided the resulting continuous variables into tertiles as described in the original publications. The tertiles were grouped so that the most clinically aggressive tertile was compared with the remaining two.

Hierarchical clustering was used to indicate relapse sample similarity with respect to post-relapse survival (short- or long-term, see definition above) and relapse site.

single probe association

Differential gene expression according to short- or long-term post-relapse patient survival (as defined above) was analyzed using the open-source R package OCplus 1.22.0 [15]. For additional information, see supplementary Methods, available at Annals of Oncology online.

All data preparation and analysis were done using SAS version 9.3 and R version 2.15.2.

results

The clinico-pathological characteristics of the 111 patients included in the translational TEX trial are summarized in Table 1. The majority of patients were diagnosed with primary breast cancer from 1995 onwards and as expected from a clinically aggressive cohort, there were high numbers of ER negative (37.5%), PR negative (51.5%), grade 3 (52.4%), and stage IV (14.8%) tumors at primary tumor diagnosis. Metastatic sites were distributed as follows: breast (15.8%), liver (22.5%), lung/pleura (1.7%), lymph node (36.7%), skeleton (4.2%), skin (18.3%), and other 0.8%.

Table 1.

Patient and tumor characteristics of the patients included in the translational TEX trial

| Patients |

||

|---|---|---|

| Number | Percent | |

| Age at primary tumor diagnosis, years | ||

| <45 | 27 | 24.3 |

| 45–55 | 45 | 40.5 |

| >55 | 39 | 35.2 |

| Calendar period of primary tumor diagnosis | ||

| 1985–1989 | 4 | 3.6 |

| 1990–1994 | 6 | 5.4 |

| 1995–1999 | 26 | 23.4 |

| 2000–2007 | 75 | 67.6 |

| Primary tumor characteristics | ||

| Estrogen receptor status | ||

| Positive | 65 | 62.5 |

| Negative | 39 | 37.5 |

| Unknown | 7 | – |

| Progesterone receptor status | ||

| Positive | 47 | 48.5 |

| Negative | 50 | 51.5 |

| Unknown | 14 | – |

| Elston–Ellis tumor grade | ||

| 1 | 4 | 4.9 |

| 2 | 35 | 42.7 |

| 3 | 43 | 52.4 |

| Unknown | 29 | – |

| T stage at diagnosis | ||

| T1 | 36 | 33.3 |

| T2 | 43 | 39.8 |

| T3 | 13 | 12.1 |

| T4 | 16 | 14.8 |

| Unknown | 3 | – |

| N stage at diagnosis | ||

| N0 | 32 | 30.2 |

| N1 | 65 | 61.3 |

| N2 | 8 | 7.5 |

| N3 | 1 | 1.0 |

| Unknown | 5 | – |

| M stage at diagnosis | ||

| M0 | 85 | 76.6 |

| M1 | 26 | 23.4 |

| Adjuvant therapy | ||

| Endocrine therapy | ||

| Yes | 47 | 42.3 |

| No | 64 | 57.7 |

| Radiotherapy | ||

| Yes | 64 | 57.7 |

| No | 47 | 42.3 |

| Chemotherapy | ||

| Yes | 48 | 43.2 |

| No | 63 | 56.8 |

gene expression modules of biological processes reflect the aggressive nature of breast cancer metastases

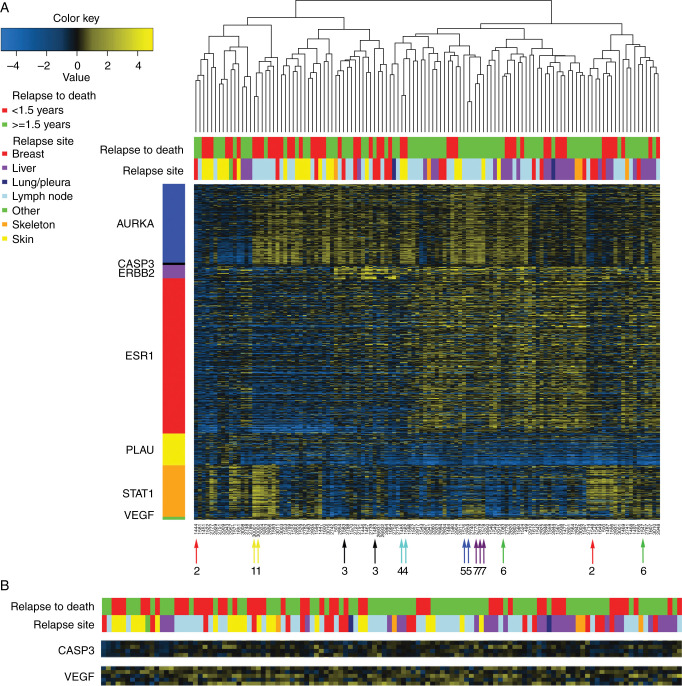

To characterize the tumor biology of breast cancer metastases, we assessed a set of seven biologically relevant gene expression modules in our 120 metastatic samples [13]. For visualization purposes, we selected those genes positively correlated with each module from our samples and carried out hierarchical clustering (Figure 1A and B). All gene modules (AURKA—proliferation, CASP3—apoptosis, ERBB2—HER2 signaling, ESR1—ER signaling, PLAU—tumor invasion/metastasis, STAT1—immune response, and VEGF—angiogenesis) show a varying range of expression values emphasizing the biological diversity between metastases. The aggressive nature of these tumors is also readily apparent with the majority displaying high expression of genes related to proliferation (AURKA module) and approximately half exhibiting low ESR1-related expression (ESR1 module). The seven patients in our cohort with multiple gene expression arrays (either several biopsies on the same metastatic site or different sites) are indicted with colored arrows and numbers (Figure 1A, bottom of the heatmap). The paired metastases from four of seven patients cluster immediately beside one another (numbers 1, 4, 5, and 7). Conversely, three metastatic biopsy pairs from the same patient and relapse cluster separately (numbers 2, 3, and 6), indicating gene expression pattern differences between these intrarelapse tumor biopsies.

Figure 1.

Hierarchical clustering of gene expression profiles of breast cancer metastases based on module genes reflecting seven biological processes (A) Positively correlated module genes were selected for visual representation of 120 breast cancer metastatic samples. Arrows indicate patients with multiple metastases. AURKA, proliferation; CASP3, apoptosis; ERBB2, HER2 signaling; ESR1, estrogen signaling; PLAU, tumor invasion/metastasis; STAT1, immune response; VEGF, angiogenesis. (B) Zoom-in of CASP3 and VEGF modules.

low ESR1 and CASP3 gene module scores are associated with poor post-relapse survival

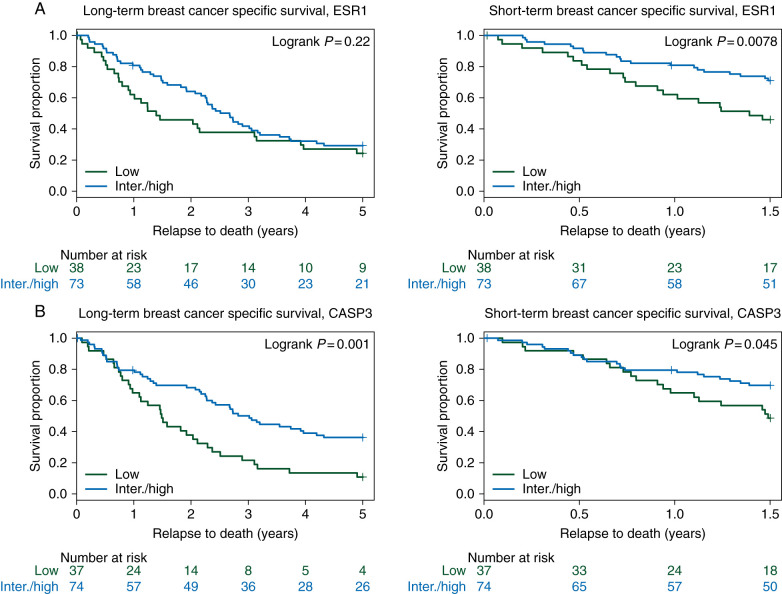

Long- and short-term Kaplan–Meier survival curves for the ESR1 and CASP3 gene modules are shown in Figure 2 A and B, (left panels, and for the remaining modules in supplementary Figures S1 and S2, available at Annals of Oncology online. Patients with a low CASP3 module score demonstrated poor long-term survival relative to those with an intermediate/high score (Figure 2B, left panel, P = 0.0010). In addition, low ESR1 and CASP3 module scores were associated with poor short-term breast cancer-specific survival (Figure 2A and B, right panels, P = 0.0078 and P = 0.045, respectively). Furthermore, using a multivariate proportional hazard (Cox) model adjusting for age at diagnosis, diagnosis date, and TEX clinical study treatment received, a more than twofold increased risk for death from breast cancer (short-term survival) was found in patients whose tumors had low CASP3 and ESR1 module scores [hazard ratio (HR) 2.2; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.1–4.1 and 2.2; 95% CI 1.2–4.2, respectively], see Table 2 (significant risk estimates in bold) and supplementary Figures S1 and S2, available at Annals of Oncology online.

Figure 2.

Long- and short-term breast cancer-specific post-relapse survival in relation to gene module groups (A) ESR1 module tertiles long-term (5 years) and short-term (1.5 years) breast cancer-specific survival, respectively. (B) CASP3 module tertiles long- and short-term post-relapse survival, respectively. A P value is based on the log-ranked test, and numbers at risk are shown underneath each graph.

Table 2.

Multivariate analysis of gene modules and subtypes in relation to patient post-relapse survival

| Long-term breast cancer-specific survival |

Short-term breast cancer-specific survivalb |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P value | HR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Modulea (n = 111) | ||||||

| ESR1 lowc | 1.3 | 0.8–2.1 | 0.27 | 2.2 | 1.2–4.2 | 0.01 |

| ERBB2 highd | 0.8 | 0.5–1.4 | 0.46 | 0.8 | 0.4–1.5 | 0.47 |

| AURKA highd | 1.2 | 0.8–2.0 | 0.38 | 1.1 | 0.5–2.1 | 0.89 |

| PLAU highd | 1.2 | 0.7–1.9 | 0.52 | 1.4 | 0.8–2.7 | 0.25 |

| VEGF lowc | 1.0 | 0.6–1.6 | 0.95 | 1.5 | 0.8–2.8 | 0.21 |

| STAT1 lowc | 1.0 | 0.6–1.6 | 0.99 | 0.8 | 0.4–1.6 | 0.58 |

| CASP3 lowc | 2.7 | 1.7–4.5 | <0.001 | 2.2 | 1.1–4.1 | 0.02 |

| PAM50a (n = 105) | ||||||

| Luminal A (Ref.) | 1.0 | – | – | 1.0 | – | – |

| Luminal B | 2.3 | 0.8–6.9 | 0.12 | 2.4 | 0.3–19.5 | 0.42 |

| HER2-enriched | 4.4 | 1.5–12.8 | 0.01 | 7.6 | 1.0–58.2 | 0.05 |

| Basal-like | 3.7 | 1.3–10.9 | 0.02 | 7.2 | 1.0–54.6 | 0.06 |

aAdjusted for age at diagnosis, diagnosis date, and treatment received.

b1.5-year survival.

cIntermediate/high as reference group.

dLow/intermediate as reference group.

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

gene module scores representative of the AKT-MTOR, RAS, and BETA-C signaling pathways are associated with poor post-relapse survival

To further characterize the biology of our metastatic samples, we extended our gene module analysis to include a set of 10 previously described biologically relevant signaling pathways (Ras, MAPK, PTEN, AKT-MTOR, PI3KCA, IGF1, Src, Myc, E2F3, and β-catenin) [14]. In summary, high AKT-MTOR (P log rank = 0.03, HR 1.7; 95% CI 1.1–2.7), RAS (P log rank = 0.03, HR 1.8, 95% CI 1.1–2.9), and BETA-C (P log rank = 0.03, HR 1.7, 95% CI 1.1–2.7) module scores were significantly associated with long-term poor post-relapse survival (supplementary Figures S3–S6, available at Annals of Oncology online).

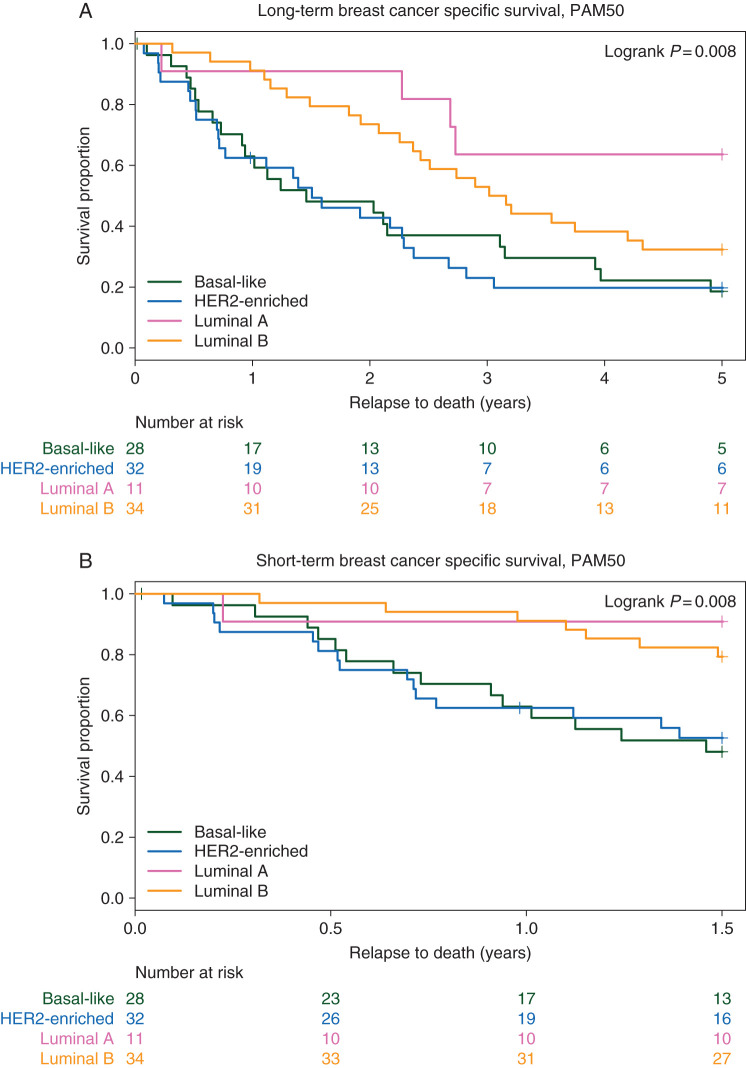

breast cancer molecular subtypes of metastases provide information of post-relapse survival

Overall, 25% of the metastases were basal-like (n = 30), 32% HER2-enriched (n = 38), 10% luminal A (n = 12), 28% luminal B (n = 34), and 5% normal-like. These subtypes were significantly associated with survival in the Kaplan–Meier analysis (P = 0.008, Figure 3A) with the shortest survival seen in the basal-like and HER2-enriched subgroups. Furthermore, using a multivariate proportional hazard (Cox) model adjusting for age at diagnosis, diagnosis date, and TEX clinical study treatment received, a more than threefold increased risk for death from breast cancer was found in patients whose tumors were basal-like and HER2-enriched (HR 3.7; 95% CI 1.3–10.9 and 4.4; 95% CI 1.5–12.8, respectively), see Table 2.

Figure 3.

The PAM50 intrinsic subtypes in relation to long- and short-term post-relapse breast cancer-specific survival. (A) The PAM50 intrinsic subtypes in relation to long-term (5 years) breast cancer-specific survival. (B) The PAM50 intrinsic subtypes in relation to short-term (1.5 years) breast cancer-specific survival. A P value is based on log-ranked test, and numbers at risk are shown underneath each graph.

basal-like, cell cycle, and mesenchymal-related genes are upregulated in patients with short-term post-relapse survival

Finally, in an effort to understand genetic differences between tumors of patients with short-term versus long-term survival, we carried out differential gene expression analysis to identify a poor metastasis survival signature. The poor metastasis survival signature included 136 unique genes differentially expressed between patients with short-term compared with long-term post-relapse survival. The expression of the included genes is presented in supplementary Figure S7, available at Annals of Oncology online and the full gene list is also provided in supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online. Strikingly, patients with short-term survival (supplementary Figure S7, available at Annals of Oncology online, red in the horizontal sidebar) displayed increased expression of the epithelial to mesenchymal marker SNAI1, the cell cycle markers CCNE1, CDC25B, and the basal/triple-negative-associated gene CAV2. Moreover, the same patients showed reduced expression of the ESR1, GATA3, and FOXA1 genes, all of which are linked to a luminal breast phenotype and ER receptor expression. A gene ontology analysis of these 136 genes is also provided in supplementary Table S2, available at Annals of Oncology online. These results are in line with our earlier findings, showing a worse survival outcome in patients with a low ESR1 module score and basal-like subtype.

discussion

It is now accepted that standard breast cancer markers alter their expression throughout tumor progression [2–5], which significantly influences patient survival [2, 5]. As such, investigation of tumor characteristics at relapse has the potential to improve patient management and survival. However, in order to be able to further individualize patient management in the metastatic setting, we need a better understanding of the association between metastatic tumor characteristics and patient survival. If tumor aggressiveness as assessed by the prognostic markers in the primary setting can be translated to the metastatic setting, this information would be clinically relevant.

To enhance our current understanding of tumor biology in breast cancer metastases, we analyzed the TEX randomized trial that included 111 patients with available gene expression information from one or more metastatic lesions. Specifically, we assessed gene modules representative of tumor biological processes and pathways, as well as, the intrinsic subtypes [12], in all metastatic samples and related our findings to patient survival. Interestingly, a significant reduction in post-relapse breast cancer-specific survival was demonstrated for patients with the lowest levels of ER receptor signaling (ESR1 module) and apoptosis (CASP3). Furthermore, high AKT-MTOR, RAS, as well as BETA-C (β-catenin) signaling were significantly associated with poor post-relapse survival. Similarly, the intrinsic subtypes in the metastases provided statistically significant post-relapse survival information, with the worst survival outcome in the basal-like and HER2-enriched subtypes. Additionally, patients with poor post-relapse survival showed high metastasis expression levels of basal-like, cell cycle, and mesenchymal-related genes with concomitant low expression of luminal genes.

While little is known about the biology of breast cancer metastases themselves, the steps governing the progression from primary breast tumor to seeding of distant metastatic lesions has been a focal point of intense investigation (for review see refs. [16, 17]). These steps comprise what is typically termed ‘the metastatic cascade’ and consist of invasion/proliferation into the tissue surrounding the primary tumor, intravasation to blood or lymph vessels, extravasation to distal organs, and finally colonization of the distant tumor microenvironment. With regard to colonization, one of the main processes that have been hypothesized as essential to the successful development of metastatic breast tumors is cell proliferation [17]. Through application of the AURKA gene module, we demonstrate that the vast majority of our samples are highly proliferative; this finding is also supported by the intrinsic subtypes where the majority of tumors are luminal B, HER2-enriched, and basal-like subtypes—all of which are associated with high levels of proliferation. Of note, the luminal A subtype of tumors that are known to display lower levels of proliferation have the best post-relapse survival in our dataset [18]. These results may emphasize the importance of proliferation in relation to survival in metastatic tumors, at least in tumors of luminal subtype, and indicate that a routinely employed proliferative marker, such as Ki-67, could also prove informative in a clinical setting.

In conclusion, an enhanced understanding of the biology of breast cancer metastases is needed to improve both patient survival in the metastatic setting and prediction of which patients are at high risk to later develop metastatic breast cancer disease. We show that the tumor characteristics of metastases significantly influence post-relapse patient survival emphasizing that molecular investigation at relapse offers clinically relevant information, with the potential to improve patient management and survival in the relapse setting.

funding

This work was supported by the Swedish Research Council (grant no: 524-2011-6857 and 521-2014-2057 to LSL), the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working life and Welfare, FORTE (grant no: 2014-1962 to LSL), the Swedish Cancer Society, the Cancer Society in Stockholm, the King Gustaf V Jubilee Foundation, the Swedish Breast Cancer Association (BRO), and the Swedish Research Council to JB and unrestricted grants from Bristol-Myers Squibb Sweden AB, Pfizer Sweden AB, and Roche Sweden AB. The gene expression profiling was carried out by Merck at the former Rosetta facility. CMP and JCH were supported by funds from the NCI Breast SPORE program (P50-CA58223-09A1), and the Breast Cancer Research Foundation (CMP).

disclosure

JB receives research funding from Merck, Amgen, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis and Bayer, paid to Karolinska University Hospital. CMP is an equity stock holder, and Board of Director Member, of BioClassifier LLC and University Genomics. CMP is also listed as an inventor on a patent application on the PAM50 molecular assay. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

acknowledgements

The TEX Trialists Group: Coordinating Investigator: Thomas Hatschek; Translational research: Mårten Fernö, Linda Sofie Lindström, and Ingrid Hedenfalk; HRQoL: Yvonne Brandberg; Statistics: John Carstensen; Laboratory: Suzanne Egyhazy, Marianne Frostvik Stolt, and Lambert Skoog; Clinical Trial Office: Mats Hellström, Maarit Maliniemi, and Helene Svensson; Radiology: Gunnar Åström; Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm: Jonas Bergh, Judith Bjöhle, Elisabet Lidbrink, Sam Rotstein, and Birgitta Wallberg; Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Gothenburg: Zakaria Einbeigi, Per Carlsson, and Barbro Linderholm; Linköping University Hospital: Thomas Walz; Skåne University Hospital Lund/Malmö: Niklas Loman, Per Malmström, and Martin Söderberg; Helsingborg General Hospital: Martin Malmberg; Sundsvall General Hospital: Lena Carlsson; Umeå University Hospital: Birgitta Lindh; Kalmar General Hospital: Marie Sundqvist; Karlstad General Hospital: Lena Malmberg

Contributor Information

Collaborators: Thomas Hatschek, Mårten Fernö, Linda Sofie Lindström, Ingrid Hedenfalk, Yvonne Brandberg, John Carstensen, Suzanne Egyhazy, Marianne Frostvik Stolt, Lambert Skoog, Mats Hellström, Maarit Maliniemi, Helene Svensson, Gunnar Åström, Jonas Bergh, Judith Bjöhle, Elisabet Lidbrink, Sam Rotstein, Birgitta Wallberg, Zakaria Einbeigi, Per Carlsson, Barbro Linderholm, Thomas Walz, Niklas Loman, Per Malmström, Martin Söderberg, Martin Malmberg, Lena Carlsson, Umeå, Birgitta Lindh, Marie Sundqvist, and Lena Malmberg

references

- 1.Davies C, Godwin J, et al. Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group (EBCTCG) Relevance of breast cancer hormone receptors and other factors to the efficacy of adjuvant tamoxifen: patient-level meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2011;378(9793):771–784. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60993-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lindstrom LS, Karlsson E, Wilking UM, et al. Clinically used breast cancer markers such as estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 are unstable throughout tumor progression. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(21):2601–2608. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.2482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Niikura N, Liu J, Hayashi N, et al. Loss of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) expression in metastatic sites of HER2-overexpressing primary breast tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2011;30(6):593–599. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.8889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amir E, Miller N, Geddie W, et al. Prospective study evaluating the impact of tissue confirmation of metastatic disease in patients with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;30(6):587–592. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.5232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thompson AM, Jordan LB, Quinlan P, et al. Prospective comparison of switches in biomarker status between primary and recurrent breast cancer: the Breast Recurrence In Tissues Study (BRITS) Breast Cancer Res. 2010;12(6):R92. doi: 10.1186/bcr2771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cardoso F, Fallowfield L, Costa A, et al. Locally recurrent or metastatic breast cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2011;22(Suppl 6):vi25–vi30. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolff AC, Hammond MEH, Hicks DG, et al. Recommendations for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing in breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists Clinical Practice Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(31):3997–4013. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.50.9984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cardoso F, Costa A, Norton L, et al. 1st International consensus guidelines for advanced breast cancer (ABC 1) Breast. 2012;21(3):242–252. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hatschek T, Carlsson L, Einbeigi Z, et al. Individually tailored treatment with epirubicin and paclitaxel with or without capecitabine as first-line chemotherapy in metastatic breast cancer: a randomized multicenter trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;131(3):939–947. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1880-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bengtsson H, Simpson K, Bullard J, Hansen K. Aroma. Affymetrix: A Generic Framework in R for Analyzing Small to Very Large Affymetrix Data Sets in Bounded Memory. Berkeley: Department of Statistics, University Of California, Berkeley; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benaglia T, Chauveau D, Hunter DR, Young DS. Mixtools: an R package for analyzing finite mixture models. J Stat Softw. 2009;32(6):1–29. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parker JS, Mullins M, Cheang MCU, et al. Supervised risk predictor of breast cancer based on intrinsic subtypes. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(8):1160–1167. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Desmedt C, Haibe-Kains B, Wirapati P, et al. Biological processes associated with breast cancer clinical outcome depend on the molecular subtypes. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(16):5158–5165. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ignatiadis M, Singhal SK, Desmedt C, et al. Gene modules and response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer subtypes: a pooled analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(16):1996–2004. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.5624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pawitan Y, Ploner A. OCplus: Operating Characteristics Plus Sample Size and Local fdr for Microarray Experiments. R package version 1.40.0. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shibue T, Weinberg RA. Metastatic colonization: settlement, adaptation and propagation of tumor cells in a foreign tissue environment. Semin Cancer Biol. 2011;21(2):99–106. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Valastyan S, Weinberg RA. Tumor metastasis: molecular insights and evolving paradigms. Cell. 2011;147(2):275–292. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheang MCU, Chia SK, Voduc D, et al. Ki67 index, HER2 status, and prognosis of patients with luminal B breast cancer. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101(10):736–750. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.