Abstract

♦ Background:Although relatively rare, encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis (EPS) is nonetheless a major concern within the renal community. Risk of developing EPS is associated with long-term peritoneal dialysis (PD). High mortality was previously reported, although surgery has since improved outcomes. Research into EPS focuses on imaging and early detection methods, genetics, biomarkers and preventive strategies. No previous studies have examined patients’ experiences of EPS.

♦ Aims: The aim of the present study was to explore the experience of patients who have undergone surgery for EPS in one center in the North of England.

♦ Methods: A qualitative phenomenological approach, involving in-depth interviews, was adopted. Nine participants were recruited out of a total of 18 eligible. Most participants were interviewed twice over a 12-month period (October 2009 to October 2010).

♦ Analysis: Interpretive data analysis was conducted, following the philosophical tradition of hermeneutics, to draw out themes from the data. Data collection and analysis took place concurrently and participants were sent a summary of their first interview to allow a period of reflection prior to the subsequent interview.

♦ Results: EPS presented the most serious challenge participants had faced since developing chronic kidney disease (CKD). Three major themes were identified, each with subcategories. The key issues for patients were related to identification of early symptoms and lack of understanding. The patients’ sense of ‘not being heard’ by health care professionals led to a loss of trust and enhanced their feelings of uncertainty. The enormity of the surgery, the suffering, and what they had to endure had an enormous impact, but an overriding aspect of this experience was also the loss they felt for their independence and for the PD therapy over which they had control.

♦ Conclusions: The findings of this study highlight a number of important issues relevant to clinical practice, including lack of information and understanding of EPS, particularly its early symptoms At the time patients transfer from peritoneal to hemodialysis, the provision of adequate information about the risks and potential early signs of EPS may not only improve their experiences, but may also assist in early detection.

Keywords: EPS, qualitative, patient experience

Encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis (EPS) is a devastating complication of peritoneal dialysis (PD) and one that can be fatal (1). The condition is caused by severe sclerosis of the peritoneum, with the bowel becoming encapsulated in a fibrous cocoon. This results in severe and prolonged gastrointestinal symptoms, culminating in bowel obstruction. The surgery itself is long, and patients postoperatively usually spend time in intensive care and require a high level of medical and nursing care. If complications occur, the wound is left open and patients may have repeated surgical interventions and a temporary stoma. A crucial aspect of care is nutritional support, allowing sufficient time for patients to resume normal eating routines. A number of teams including dieticians, wound care specialists, pain teams and stoma care nurses are involved in the care of these patients (1). Currently there are only two centers in the UK offering the surgical service.

When managing patients on PD it is important to understand the risks of developing EPS. In current PD practice the most significant risk factor is the duration of PD (2-6). This and other factors are well reported in the literature (2,3,6,7). As it is rare, symptoms are often not recognized until patients are very ill. In our experience (unpublished data) most patients have lost > 10% of their body weight in the six months prior to surgery, militating against a good surgical outcome. Recommendations for clinical management have focused on nutritional support, surgical intervention and practical pre- and postoperative care in hospital (1). The social and psychological impact of this disease has not previously been investigated.

Understanding the lived experience of long-term conditions, using qualitative methodology, offers insights into how individuals cope and manage their condition (8). EPS is a major issue, and its implication for patients deserves further investigation. Studies on the patients’ experiences of living with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and dialysis have mostly focused on hemodialysis (HD) (9-11). No previous studies have examined the lived experience of EPS. This study sought to address that gap in knowledge.

The aims of the study were:

To explore patients’ understanding of EPS in the context of their lived experience on dialysis.

To examine the meaning and impact of the condition, as constructed by individual patients.

Design

A qualitative approach was used to obtain a deeper understanding of the ‘lived experience’ from the patient perspective. The particular approach chosen was phenomenology, often defined as the study of experiences or consciousness (12). Within the broad field of phenomenology, there are differing philosophical stances and, for this study, the epistemology is derived from constructivism-interpretivism and hermeneutics (13). Hermeneutics aligned to the interpretive philosophy is recognized as an approach to health research which focuses on meaning and understanding (14). Hermeneutics and the work of Heidegger and Gadamer were applied to this study (13). The use of unstructured interviews was chosen as the method of data collection, to obtain rich and meaningful responses, allowing participants to talk freely about their experiences.

Sample and Sample Size

The study was conducted at a specialist center in the North of England, which is one of only two in the UK currently funded for surgery specific to EPS, hence accepts patients from across the UK. Patients were eligible for inclusion if they had a confirmed diagnosis of EPS and had undergone surgery. Data collection took place over one year. The anticipated sample size was 10 - 20 participants.

Access and Recruitment

Patients were identified for the study once diagnosis of EPS was confirmed and surgical intervention was required.

Data Collection

Ethical approval was obtained to carry out the study and all participants provided written consent to interview. One researcher conducted all interviews. All interviews were audio-recorded and fully transcribed with patient consent. Interviews commenced with a simple open question: “Tell me about your experience of EPS.” This opening question was followed by a series of prompts when necessary. On completion of initial interviews, study participants were provided with a written summary of initial findings. These were individualized to each participant. The rationale for this was to ensure that the initial interpretations were representative, but also to allow the participants to add any new information. It was also an opportunity to ensure that a shared understanding had been achieved, as recommended when enabling the hermeneutic circle (15,16). The interpretations were used to help prompt the participants; no one disagreed but some did add further views and comments. A second interview was then arranged, where possible, with each participant.

Data Analysis

Data analysis followed the four steps identified by Fleming et al. (15) and recommended in phenomenological studies. The text as a whole is examined in order to understand the subject matter. Every sentence or section is then related to the whole, described as a movement between the parts and the whole. The process will then identify where a shared understanding has been achieved between researcher and participant.

This process was repeated several times, which is recommended as part of the hermeneutic process, to guide subsequent interviews (15,17). Alongside this process and during data collection, a reflexive journal was written; the process of reflexivity is continuous and is recommended in hermeneutic phenomenology (13,18,19). Issues of quality and trustworthiness were addressed throughout the study, following principles applied to qualitative research with evidence of a clear audit trail, use of a reflexive journal, evidence of credible methods and use of written interpretations (18). The reflexive journal was used alongside the interview transcripts to demonstrate the process of interpretation and the reactions of the researcher and participants.

Results

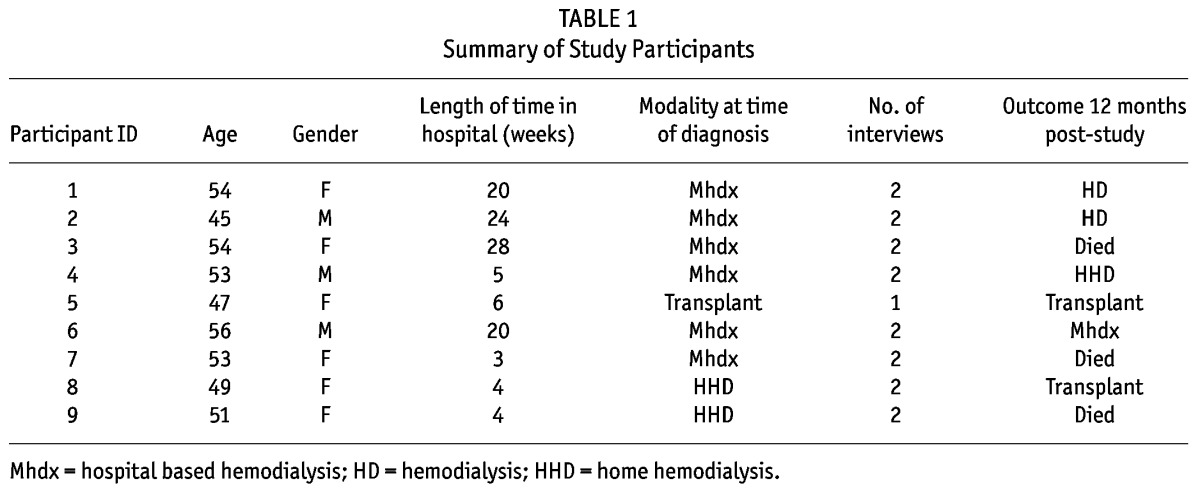

Participants were recruited from a single surgical referral center over a one-year period, 2009 - 2010. Only 18 patients were eligible during the study period. Two of these 18 patients declined, one became too unwell and six lived outside of the UK. Interviews were carried out with nine individuals; eight individuals were interviewed on more than one occasion. Hence, a total of 17 interviews were conducted. Characteristics of the study sample are presented in Table 1. The age range of the participants was narrow, a result of the small sample size but also a reflection of their CKD illness and history and are representative of patients likely to have EPS (20,21). The small sample size did not allow for a meaningful analysis of the influence of participant characteristics on the study findings. All were diagnosed with EPS while on HD apart from one participant who developed EPS post-transplant. All had experienced PD for more than four years. Three major themes and associated subthemes were identified from the data, encompassing the experience of the participants. Illustrative quotations for each of the main themes are presented throughout.

TABLE 1.

Summary of Study Participants

Understanding EPS

In trying to understand EPS, participants talked about how the symptoms of EPS presented, the perceived lack of understanding of EPS by healthcare practitioners (HCPs) and the journey to the point of diagnosis.

Interpretation of Symptoms: All the participants referred to early symptoms and how they had interpreted them.

I mean sometimes I was being sick every day, but it’d be like, Oh, it’s because of what I’ve eaten; I shouldn’t eat that cheese any more or I shouldn’t eat such and such a thing. ID 9

Participants were unaware that the symptoms they had experienced were due to EPS. Since symptoms tended to be gastrointestinal, participants often related the symptoms to problems with digestion, their dialysis therapy or some other medical condition they were familiar with.

I didn’t realize what was going on... My appetite wasn’t very good. Sometimes I had constipation, sometimes I had the runs. I just felt weak, no energy,... and then it just come on gradually. Then sometimes I would think, “Oh, it’s gone away now, I’m all right”... I ended up saying, “Oh, it’s the dialysis that’s doing it”... Yeah. I used to think they’re dehydrating me... And making me feel sick, because it does. ID 8

These early symptoms had often started very gradually and were initially perceived as having little significance.

Not Being Heard: Once patients realized that their symptoms were worsening, and could not be attributed to anything familiar, they began to seek help. Participants commented that they were “not being heard,” and used statements such as “I can’t keep on suffering.” Participants felt ‘let down,’ ‘ignored,’ or ‘frustrated’ as they struggled with worsening symptoms, but without proper answers or explanations being provided by the HCPs responsible for their care. Some had endured many months of pain and suffering. Not being heard led to a loss of trust in HCPs and thus evoked feelings of being neglected.

It felt like everybody was, like, saying, “Well, it’s not my responsibility, it’s his responsibility or it’s her responsibility,” you know? And nobody was bothering. ID 1

Cos I really feel like from the... the sort of Christmas time, right through to March, I was on my own, with no suggestion of what it could be, and I was just plodding on and sort of struggling to keep my fluids up, and erm... try and keep healthy. ID 8

The participants often reached the point of desperation.

Oh God, yeah because I had been saying to the doctor for a year, surely there’s something somebody can do, I says, because I can’t keep suffering like this, it was horrendous. The pain I was getting... I was just so ill. ID 3

Knowledge and Information Gaps: Participants reported that they had no information or knowledge of EPS, and this created uncertainty. Some of the uncertainty associated with the experience of EPS arose from not knowing or understanding its symptoms, uncertainty about the outcome of surgery and uncertainty about mortality.

Participants perceived that HCPs did not know enough about EPS and so were unable to provide the information needed.

I don’t think they know enough about it. They’re not confident in saying anything, because their field is hemodialysis, so really they probably don’t know much about the peritoneal dialysis. So it’s like... it’s not their field. ID 2

Some participants suspected that other professionals knew the cause of their symptoms but had not disclosed this information.

I didn’t know that it was related to the peritoneal dialysis, because nobody told me really. It was only when I asked more about it that I found out that it was. ID 6

Participants perceived that HCPs’ lack of understanding created a reluctance to be open and honest, as HCPs were disempowered by the lack of effective diagnostic testing.

Diagnosis, Shock, and Confronting the Possibility of Death: The eventual diagnosis of EPS was a highly significant event for participants. There was immediate faith in the abilities of the surgeon, not only to save them from inevitable death, but more immediately to relieve their suffering.

I had every confidence. Yes. And I did... and I didn’t even worry that he wouldn’t manage it, for some reason, and that he would do his best, and that’s all that I really wanted from him, and that’s what he gave me, he delivered it well. He was my hero. ID 8

This is it, this is why when I saw the surgeon and he diagnosed it. And this is why I felt there might be a chance now. I might still live... ID1

The realization of what EPS meant and the desperation they felt paved the way for the battle ahead. Participants perceived there was no choice or decision to be made and fully accepted the proposed treatment plan. The diagnosis enabled them to piece the jigsaw together, giving them a chance to reflect and, in a sense, to gain meaning.

This was like it’s a straight fight and I’ll either win it, or I don’t and that’s it. And not really expecting to win it, but knowing that, you know, I’m going to give it my best. ID 6

I don’t think I would have survived six months, another six months, if I hadn’t had it done. So really I hadn’t got a choice, I’d got to have it done. There were no ifs or buts, it had got to be done. ID 3

An Embodied Experience

The second theme relates to aspects of the surgery itself, and the effects on the body, not just physically, but how it was perceived by participants and others.

Enduring: Some participants had to endure what seemed like a never-ending procession of operations, pain, wound washouts and infections—’tubes, and more tubes.’ Participants reported on the lack of preparation for major surgery, with no written information provided. The only information received was verbal information during consultations with a surgeon when the opportunity arose. However, two of the participants had been urgent admissions to hospital and did not have the benefit of an outpatient consultation.

The suffering endured by participants during treatment was all-encompassing and some reached a point of desperation; they felt they could endure no more.

Yeah, I had lost the will to live. I thought, I just want to go to sleep and not wake up again. ID 3

Because I know that after the operation I had the most horrendous pain. And it was the worst pain that I ever went through, I think in my life. It was severe. I couldn’t take it any more. ID 5

It was difficult for participants to describe how they managed to get through the experience. The language used in these descriptions of suffering was a reflection of the intensity of the emotions provoked. For example, for some participants their pain was constant, and at times became unbearable.

Because of the sclerosis being so bad, they couldn’t pull the stoma in too far and it kept retracting. So all the feces wouldn’t go in the bag, it was burning all my side. So I was red raw. Literally it was just like I was being burnt alive, and it was just horrendous. ID 3

Bodily Awareness from Others and Within: Being aware of the changes to their bodies relates to how surgery caused the body to be objectified from the self. Noticing changes to their bodies and coping with a stoma is one example as described here.

The stoma nurse, oh she was fantastic. Initially she did everything, and I wanted her to do it, I didn’t want to touch it. I just didn’t want anything to do with it. I looked at it, but I felt it was quite alien. ID 5

This emphasizes how participants and those around them noticed changes to their bodies, making their own body an object of scrutiny.

Struggles with Eating: One of the significant aspects of bodily changes described by participants was their view of eating and their relationship to food, especially for those who had spent longer in hospital and had been given nutrition via intravenous routes. Surgery to the bowel meant that eating was not normally possible for several weeks.

I couldn’t even look at food. And I’d be vomiting because of the smell of the food..., I just threw up. I never thought I would eat ever again. ID 3

I found after I had the operation, I had a different stomach... The stomach I’d had for fifty years no longer functioned in the same way. ID 6

Adjustments and Transitions

Participants adjusted and evaluated the effects of EPS but this was often not separate from their experience of CKD and dialysis. Participants had already undergone life changes when they developed CKD. Additional adjustments now had to be made as a consequence of EPS.

Losses: The experience of loss was related to the difference in functional ability before and after surgery. Loss of control over illness had been experienced in HD, which involved handing over responsibility to others, and also loss of control while participants were in hospital. The loss they felt for PD included both of these aspects, but by moving to HD they had lost the freedom and independence that PD had offered them.

I feel less in control now. I feel as if I’ve handed my life over to other people now and I really liked, you know, the independence that I had before. I would really like home dialysis. ID 7

During the second interviews it was clear that all participants felt they were showing signs of recovery, although they remained shocked at how long it was taking. They often referred to earlier occasions when ‘acute’ events had taken place and they had recovered very quickly. This time the resilience they had previously felt was missing, and they had to develop a sense of coherence and rebuild themselves, not just physically, but also psychologically and socially. For some of the participants, the loss of control related not only to EPS, but to their experience of HD compared with PD. They wanted a life that gave them more control and which recreated the level of independence and freedom that PD had offered.

Support Structures: Families played a crucial role, helping participants to get through EPS, and were a constant source of support. Although the focus was on EPS, on many occasions the participants referred to their families and the broader impact that CKD had had on them. This created guilt, and participants described how they had tried to protect their families from the consequences of their illness.

But my kids just, they were always positive. They was always like, you know, they were like on the phone to me saying, you know, “Come on, Mum, you’ve got to get through, you know, you’ve got a lot to live for.” ID 3

Locating Self: Participants described their belief structures and gave a sense of the strategies used in their experience of EPS. For many, their experience of EPS was inextricably linked with their long-term condition. There were many times during the interviews where comparisons were made, usually associated with life changing events, following their diagnosis of CKD and then later EPS. They described how their own abilities and characteristics had equipped them to adjust and cope. Participants described their determination to cope and their need to remain independent and in control. How they viewed life now took on a different meaning than previously, and ‘feeling lucky to be alive’ became existential in its new meaning.

So, you know, we’ve... there’s a lot of financial worries, but I think when you’ve been through something that might mean that you’re not there, just actually... you know, being there. ID 6

Just get on with life now. It weren’t my time. I must have got nine lives, like a cat. Because I’ve used six of them up with things. But what they tell me... I think I am very lucky. Very lucky. ID 2

Discussion

Participants in the study provided powerful, often moving, accounts, which provide valuable insights and lessons for practice. A major finding of the present study, and an important issue for clinical practice, was participants’ perception that HCPs lacked knowledge and understanding of EPS symptoms. For most of the participants, the symptoms of EPS arose after they had transferred from PD to HD, or following a transplant.

The study highlighted a lack of communication, knowledge and expertise from both patients and HCPs. It is, however, acknowledged that the early signs of EPS can be difficult to interpret, making diagnosis challenging (1,22). Some of the symptoms described by participants have been highlighted retrospectively by dieticians in the center where EPS surgery is performed (23). Hence, the symptoms are recognized and documented (2,22,24).

The issue of ‘not being heard’ and needing to legitimize symptoms with a meaningful label or diagnosis is not necessarily specific to EPS (25-30). There was an enormous sense of relief once diagnosis was determined and surgical referral was initiated; symptoms were thus legitimized. In the case of EPS, uncertainties around diagnostics and risks remains a dominant problem for the medical profession (1).

This study highlights a need for new strategies to increase patients’ and HCPs’ awareness of EPS. Nutritional measurements and monitoring of gastro intestinal symptoms could be evaluated (23) to highlight early symptoms.

The present study raises questions of what, when and how much risk information should be given, and highlights important issues concerning preparation for, and transition to, HD for long term PD patients. Shared decision making and communication of risk information is now regarded as an important component of the relationship between HCPs and patients and should be part of routine care and management (31).

Educating the wider clinical team is one way to ensure that HCPs, particularly in HD units, gain confidence in diagnosing EPS at an early stage. This will have the effect of avoiding acute admissions and ensuring early referral to a specialist center for surgery.

This study emphasized the importance of families in supporting the participants and the financial, social, and psychological impact on families. As EPS surgery is currently offered only in two centers in the UK, the implications of being far from home can be a financial and social burden.

The transition between PD and HD in this study was linked to a great sense of loss. In the context of long-term conditions, loss equates to powerlessness (32) and is linked to the various theoretical concepts of suffering, control, identity, and security (33,34). For clinical practice, this emphasizes the need to support patients through transitions. Since long-term PD is a risk factor for EPS, this is an important aspect of patient management and care. It is essential that patients be given adequate information and preparation ahead of the transfer to HD. The transitions between dialysis therapies is well documented in the literature in terms of the integrated care concept (35), and recognizes the probability that patients with CKD will at some stage go through a range of dialysis modalities (36,37). These issues have rarely been studied from the patient’s perspective (38), and the present study is able to offer some insight into the difficulties and challenges that are likely to face clinicians in preparing patients for the transfer. Being offered home HD for PD patients is a way forward to maintain independence.

Chronic kidney disease as an illness involves technical aspects of care, self-management and the transition between dialysis modalities, but, with EPS, fundamental issues of life and death take center stage. The processes determining the patient’s ability to survive on dialysis have been examined in other studies (39). They discuss the transformation of patients and how they have accomplished this, not necessarily passively but often actively, in their endeavor to reconstruct the “self” to embody self-identity, self-worth and self-efficacy. In particular, there is interest in the process of setbacks described as “risk of death” and “repeated setbacks” (39). These views seem relevant to the current study, as the participants experienced adjustment to CKD and dialysis, achieving a balance of normality until EPS again brought the illness into the foreground, accompanied by an unexpected degree of suffering and trauma. This is also closely related to a model developed from a meta-synthesis of studies on long-term conditions described by Paterson et al. (40). The model starts with illness in the foreground and views suffering during sickness as destructive both to the self and to other people. The authors describe a shift in perspective when the illness is no longer in the foreground to one of “wellness in the foreground.” The individual then makes the self the identity, not the disease. This shift in perspective is not linear and can change when there are threats to self or during times of acute events (40). This theory sits well with how participants in this study described the impact of EPS, renegotiating and redefining their roles, losses and how everyday living was part of the process. The empowerment participants strove for was related to their own belief in their ability to manage their long-term condition.

Although 17 interviews were conducted, data were obtained from only nine participants in total. The small sample size can be considered a limitation. However, a small sample size is consistent with qualitative research that aims to explore patient views in depth and detail (41). At a national level, few patients develop EPS and, therefore, this study can be considered to have captured a detailed and meaningful view of the experiences of EPS patients more generally. Those patients who do develop EPS have many complex medical problems which may limit their ability to participate in qualitative research studies.

Recommendations for practice can be summarized as:

Understand and recognize patients at risk of EPS.

For those at risk, provide monitoring for early gastrointestinal symptoms either with regular specific assessments and/or written information.

Transitions to HD should be timely, involving patients in discussions, in particular about how to continue with self care.

If any suspicions of EPS are indicated, refer early to a specialist center.

Conclusions

This is the first study to explore the lived experience of patients with EPS and it offers an in-depth insight into the effects it can have on patients and their families. The recommendations for practice identify some key points to enhance the management of these patients in clinical practice. The key message, however, is enhancing communication with patients, following the principles of shared decision making by informing them of risks and prognostic information. The experience of EPS was truly “a journey of survival.”

Disclosures

The study was funded by Kidneys For Life (Charity at Manchester Royal Infirmary, UK) and the Kenyon Gilson Fund (Charity in UK for EPS-related research).

References

- 1. Augustine T, Brown P, Davies S, Summers A, Wilkie M. Encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis: Clinical significance and implications. Nephron Clin Pract 2009; 111:149–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brown E, Van Biesen W, Finkelstein FO, Hurst H, Johnson D, Kawanishi H, et al. Length of time on peritoneal dialysis and encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis. Perit Dial Int 2009; 29:595–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brown M, Simpson J, Kerssens J, Mactier R. Encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis in the new millennium: a national cohort study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2009; 4(7):1222–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kawanishi H. Surgical and medical treatments of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis. Contrib Nephrol 2012; 177:38–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kawanishi H, Moriishi M. Epidemiology of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis in Japan. Perit Dial Int 2005; 25(Suppl 4):S14–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Summers A, Abrahams A, Alscher D, Betjes M, Boeschoten E, Braun N, et al. A collaborative approach to understanding EPS: the European perspective. Perit Dial Int 2011; 31:245–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Allen D. Hermeneutics: philosophical traditions and nursing research practice. Nurs Sci Q 1994; 8(4):174–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Thorne S, Paterson B, Acorn S, Canam C, Joachim G, Jillings C. Chronic illness experience: insights from a meta-study. Qual Health Res 2002; 12(4):437–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lindqvist R, Carlsson M, Sjoden P. Perceived consequences of being a renal failure patient. Nephrol Nurs J 2000; 27(3):291–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Moran A, Scott P, Derbyshire P. Existential boredom: the experience of living on haemodialysis therapy. Med Humanit 2009; 35:70–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Polaschek N. The experience of living on dialysis: a literature review. Nephrol Nurs J 2003; 30(3):303–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Moran D. Introduction to phenomenology. Routledge: London and New York, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Koch T. An interpretive research process: revisiting phenomenological and hermeneutical approaches. Nurse Res 1999; 6(3):20–34. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Charalambous A, Papadopoulas R, Beadsmoore A. Ricoeur’s hermeneutic phenomenology: an implication for nursing research. Scand J Caring Sci 2008; 22:637–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fleming V, Gaidys U, Robb Y. Hermeneutic research in nursing: developing a Gadamerian-based research method. Nurs Inq 2003; 10(2):113–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sorrell J, Redmond G. Interviews in qualitative nursing research: differing approaches for ethnographic and phenomenological studies. J Adv Nurs 1995; 21:1117–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Johnson M. Heidegger and meaning: implications for phenomenological research. Nurs Phil 2000; 1:134–46. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Koch T. Implementation of a hermeneutic inquiry in nursing: philosophy, rigour and representation. J Adv Nurs 1996; 24:174–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Smith B. Ethical and methodological benefits of using a reflexive journal in hermeneutic-phenomenological research. Image: J Nurs Schol 1999; 31(4):359–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Habib A, Preston E, Davenport A. Risk factors for developing encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis in the icodextrin era of peritoneal dialysis prescription. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2010; 25:1633–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Johnson D, Cho Y, Livingston B, Hawley C, McDonald P, Brown F, et al. Encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis: incidence, predictors and outcomes. Kidney Int 2010; 77:904–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kawaguchi Y, Saito A, Kawanishi H, Nakayama M, Miyazaki M, Nakamoto H, et al. Recommendations on the management of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis in Japan 2005: Diagnosis, predictive markers, treatment, and preventative measures. Perit Dial Int 2005; 25(Suppl 4):S83–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jordan A, De Freitas D, Hurst H, Alderdice J, Brenchley PEC, Hutchison AJ, et al. Malnutrition and refeeding syndrome associated with EPS. Perit Dial Int 2007; 27(1):100–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. De Freitas D, Jordan A, Williams R, Alderdice J, Curwell J, Hurst H, et al. Nutritional management of patients undergoing surgery following diagnosis with EPS. Perit Dial Int 2008; 28:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Brown P. Naming and framing: The social construction of diagnosis and illness. J Health Soc Behav 1995; 35:34–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kralik D, Brown M, Koch T. Women’s experiences of ‘being diagnosed’ with a long-term illness. J Adv Nurs 2001; 33(5):594–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Madden S, Sim J. Creating meaning in fibromyalgia syndrome. Soc Sci Med 2006; 63:2962–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nettleton S. ‘I just want permission to be Ill’; Towards a sociology of medically unexplained symptoms. Soc Sci Med 2006; 62:1167–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Stockl A. Complex syndromes, ambivalent diagnosis, and existential uncertainty: The case of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE). Soc Sci Med 2007; 65:1549–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Weiner J. ACare: A Communication training program for shared decision making along a life-limiting illness. Palliat Support Care 2004; 2:231–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Coulter A, Collins A. Making shared decision making a reality: No decision about me, without me. London, UK: The Kings Fund; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hummel FI. Powerlessness. In: Larsen P, Lubkin I, eds. Chronic Illness Impact and Intervention. California: Jones and Bartlett Publishers; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Strandmark MK. Ill Health is powerlessness; a phenomenological study about worthlessness, limitations and suffering. Scand J Caring Sci 2005; 18:135–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Aujoulat I, Luminet O, Deccache A. The perspective of patients on their experience of powerlessness. Qual Health Res 2007; 17(6):773–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Davies S, Van Biesen W, Nicholas J, Lameire N. Integrated Care. Perit Dial Int 2001; 21(Suppl 3):S269–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fluck R. Transitions in care: What is the role of peritoneal dialysis. Perit Dial Int 2008; 28:591–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Murtagh FEM, Murphy E, Sheerin N. Illness trajectories: an important concept in the management of kidney failure. Nephrol Dial Transpl 2008; 23:3746–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hutchinson TA. Transitions in the lives of patients with end stage renal disease: a cause of suffering and an opportunity for healing. Palliat Med 2005; 19(4):270–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Curtin RB, Mapes D, Petillo M, Oberley E. Long-term dialysis survivors: A transformational experience. Qual Health Res 2002; 12(5):609–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Paterson B, Thorne S, Acorn S, Jillings C, Joachim G, Dewis M. The shifting perspectives model of chronic illness. J Nurs Schol 2001; 33(1):21–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Holloway I, Wheeler S. Qualitative Research for Nurses. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Science ltd; 1996. [Google Scholar]